Abstract

Assessing cytotoxicity towards human cells is a critical step in preclinical drug development. In preclinical toxicology, human cell lines allow for the analysis of both general and organ-specific toxicity, thus, helping reduce development time and costs. Predicting cytotoxic IC50 and GI50 values facilitates the early evaluation of new pharmaceutical agents by assessing the possible therapeutic window. Ten non-tumor and 10 tumor cell lines commonly used in toxicology were selected to develop QSAR models using GUSAR software and ChEMBL data. GUSAR employs atom-centric electrotopological QNA and substructural MNA descriptors to encode molecular structure and utilizes the RBF–SCR algorithm to train QSAR models. The best-performing models (R2 > 0.5, RMSE < 0.8; mean R2 = 0.691, mean RMSE = 0.584) were selected using 5-fold cross-validation. These models were implemented in the freely available web application CLC-Pred 2.0 (Cell Line Cytotoxicity Predictor), initially developed for qualitative prediction of cytotoxicity in human cell lines.

1. Introduction

Preclinical toxicology studies are an important step in drug development that provides an early safety assessment prior to clinical trials. One of the key aspects in such studies is the assessment of cytotoxicity in cell lines, which allows the identification of the adverse effects of compounds on cell viability and the estimation of possible general, organ-specific, or tissue toxicity. Cell lines are populations of cells capable of long-term cultivation under artificial conditions. Human cell lines are diverse tools covering dozens of tissue types and hundreds of pathologies, making them indispensable in research. They are widely used to study disease mechanisms, evaluate drug-like compounds, and assess their toxicity. In preclinical toxicology studies, cell lines are used for the analysis of both general and organ-specific toxicity of substances. For example, HepG2 cells are used to assess hepatotoxicity [1], BEAS-2B cells are needed to describe the effects of substances on the respiratory tract [2], and HUVEC cells are employed to analyze vascular toxicity [3]. Due to their high reproducibility, standardization, and availability, cell lines are widely used in preclinical toxicology studies to assess the effects of chemical compounds on cell viability and function [4].

Modern cell lines are divided into tumor and non-tumor, as well as into transformed and normal cell lines. They are widely used to study the processes of cell division, apoptosis, genetic changes, and metabolic pathways, not to mention their role in the assessment of antitumor activity and toxicity of substances [5]. Currently, more than 6000 human cell lines have been registered in international databases, such as Cellosaurus (https://www.cellosaurus.org, accessed on 12 December 2025), covering a variety of tissues and organs, from skin and lungs to liver, kidneys, and the vascular system [6]. These include both tumor lines (e.g., HepG2, Caki-1) and normal (non-tumor) lines (e.g., NHDF, MRC-5, HUVEC). Such diversity allows the modeling of both systemic and organ-specific effects, including inflammation, metabolism, cellular senescence, and toxicity. The diversity of cell lines makes the selection of an experimental model more flexible and increases the reliability of results in preclinical studies. ATCC (American Type Culture Collection) includes over 500 human cell lines that may be used in toxicological studies (https://www.atcc.org/, accessed on 12 December 2025).

Today, there has been accumulated a large volume of experimental data on the cytotoxicity of compounds in relation to various cell lines. This enables the creation of predictive models, Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship (QSAR) models among them. The development of QSAR models can significantly reduce both the time and cost of studies, providing toxicity predictions based on theoretical calculations when only the structural formula of a compound is known. The ChEMBL database [7] contains a significant body of information on experimental studies, including IC50 and GI50 values, making it an important and convenient resource for developing QSAR models [8]. PubChem also provides data on experimental studies of cytotoxicity for substances on different cell lines [9].

While traditional non-clinical testing relies predominantly on animal studies, regulatory agencies increasingly recognize computational approaches as complementary tools within integrated testing strategies. The International Council for Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH M7(R2)) guideline represents a landmark achievement establishing the first internationally harmonized framework for the regulatory acceptance of QSAR predictions as an alternative to experimental testing in assessing bacterial mutagenicity of pharmaceutical impurities [10]. However, for organ-specific toxicity endpoints relevant to cell line-based assessments, no equivalent regulatory frameworks have been developed so far to formally endorse QSAR models as a replacement for in vivo studies. The OECD Guidance Document on QSAR Validation previously established five essential principles for model validation: defined endpoint, unambiguous algorithm, defined applicability domain, appropriate validation metrics, and mechanistic interpretation [11]. The recent OECD (Q)SAR Assessment Framework extends these principles with a systematic methodology for the regulatory assessment within defined contexts of use [12]. Major regulatory initiatives explicitly support New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) development. The FDA’s Predictive Toxicology Roadmap (2017) emphasizes the “context of use” as the foundation for qualification and regulatory acceptance [13]. The FDA/CDER 2020 commentary [14] acknowledges that improvements increasing clinical outcome predictivity are encouraged and needed, explicitly recognizing QSAR as NAMs. The EMA NAMs Horizon Scanning Report [15] confirms that while no NAMs are currently qualified for regulatory use, such methodologies are “advancing to technology readiness levels sufficient for initial engagement with regulators.” The trajectory established by ICH M7(R2) for mutagenicity prediction provides a precedent suggesting that as experience accumulates with organ-specific toxicity QSAR models and validation datasets expand, similar regulatory frameworks may emerge for cell-based cytotoxicity predictions. The models presented in our study align with the 3Rs principles (Replacement, Reduction, Refinement) and OECD validation principles, providing hazard identification, compound prioritization, and mechanistic investigation in drug development.

Recently, Feitosa with co-authors developed the Cyto-Safe web application with SAR models for predicting cytotoxicity of substances on two cell lines, 3T3 and HEK 293 [16]. Earlier, we developed freely available web applications CLC-Pred [17] and CLC-Pred 2.0 [18] with SAR models that made qualitative predictions of compound toxicity against hundreds of tumor and non-tumor human cell lines based on ChEMBL and PubChem data. Such web applications provide a general idea of cytotoxic potential against cell lines but do not offer quantitative assessments that are important when comparing the activity level. The estimation of IC50 and GI50 values is crucial for the calculation of therapeutic interval and dosage of substances in preclinical and clinical studies and can serve as a characteristic used to select the most promising drug candidates.

Verma and Hansch performed one of the earliest QSAR models of podophyllotoxin derivatives for four cancer cell lines using physicochemical descriptors. The resulting models demonstrated a high degree of agreement with the experimental data (R2 from 0.960 to 0.836) and a good predictive ability (Q2 from 0.911 to 0.705) [19]. Q2 is the cross-validated R2, determined by a leave-one-out procedure on the training set. Earlier, we also demonstrated the development and implementation in BC CLC Pred web-application of QSAR models to predict IC50 and GI50 values for compounds tested on nine human breast cancer cell lines with a reasonable accuracy of prediction (mean R2 and RMSE values calculated by 5-fold cross-validation were 0.599 and 0.679, respectively) [8].

As most scientists lack the opportunity to test substance cytotoxicity on panels of human cell-lines [8], the development of a freely available in silico tool to predict quantitative values of cytotoxicity against different non-tumor and tumor human cell lines is in high demand. In this study we created high quality QSAR models by GUSAR software (version 2014) [8,20,21] for dozens of human cell lines, which have been implemented in the CLC-Pred 2.0 web application (https://way2drug.com/clc-pred/, accessed on 12 December 2025) [18].

2. Results

2.1. Data Analysis

Starting with ATCC data on human cell lines designated for toxicological studies, we analyzed the ChEMBL database to identify cell lines with sufficient amount of experimental data (number of unique compounds > 100) with definitive quantitative IC50 or GI50 values. As a result, 17 non-tumor and 15 tumor human cell lines were selected. The experimental data and structures of compounds were extracted from ChEMBL (v.33). IC50 and GI50 values were converted to pIC50 and pGI50 values, respectively. For duplicate chemical structures, the corresponding data were consolidated by calculating the median value. Records with inappropriate structures, such as mixtures, charged structures, inorganic compounds, or compounds with a molecular mass greater than 1250 Daltons, were removed. As a result, training sets were created for each selected human cell line. The characteristics of training sets for non-tumor and tumor cell lines are given in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively. Table 1 shows that non-tumor cell lines covering a wide range of tissues were selected: skin (BJ, HaCaT, HFF, NHDF), gastrointestinal tract (CCD-18Co, GES1), kidney (HEK-293, HEK-293T), lung (BEAS-2B, HFL1, MRC-5, WI-38), blood vessels (HUVEC, HMEC-1), breast (MCF-10A), blood (PBMC), and retinal pigment epithelial cells (TERT-RPE1).

Table 1.

General characteristics of non-tumor cell lines and corresponding datasets.

Table 2.

General characteristics of tumor cell lines and corresponding datasets.

Seven cell lines (BJ, CCD-18Co, HFF, HFL1, MRC-5, NHDF, and WI-38) are fibroblasts, seven (BEAS-2B, GES1, HEK-293T, HEK293, HUVEC, MCF-10A, TERT-RPE1) are epithelial cells, two (HMEC-1, HUVEC) represent endothelial cells, and one (HaCaT) keratinocytes. Most of the datasets contained IC50 values, whereas datasets with GI50 values were created only for HUVEC and MRC-5 cell lines. For most cell lines, the mean pIC50 and pGI50 values are around 5 (excluding PBMC and HUVEC that had values close to 6), which is the generally accepted threshold between active and inactive compounds (pIC50 and pGI50 values of 5 correspond to a concentration of 10 µM). This indicates that the datasets contain sufficient numbers of both active and inactive compounds, and QSAR models created using these data will enable an effective discrimination between active and inactive compounds. QSAR models typically tend to bias their predictions toward the mean [22], so it is important that this value lies near the generally accepted boundary between active and inactive compounds. At the same time, a wide range of values is observed across the datasets. It is always above 3 logarithmic units, which is also one of the indicators of the potential to create good QSAR models. Thus, the formal parameters of the data in the training sets indicate that there were no obstacles in creating accurate QSAR models using these data.

Table 2 shows that the selected tumor cell lines cover a wide range of tissues, including skin (A-375), lung (A-549, Calu-3), colon (Caco-2, COLO 205, HCT-8, SW-620), liver (HepG2), kidney (Caki-1), blood (THP-1), as well as nervous (SH-SY5Y) and lymphoid (U-937) tissues, allowing for the modeling of organ-specific toxic effects. Nine tumor cell lines from Table 2 belong to carcinoma (A-431, Caki-1, SCC-25) and adenocarcinoma (A-549, Caco-2, Calu-3, COLO 205, HCT-8, SW-620). The list of tumor cell lines includes also melanoma (A-375), neuroblastoma (SH-SY5Y), acute monocytic leukemia (THP-1), and lymphoma (U-937).

Table 2 shows the average values of the studied compounds’ activity against tumor cell lines, along with their ranges in pIC50 and pGI50 values. These data, as for non-tumor cells, show that for most cell lines, the average values of pIC50 and pGI50 are around 5 (excluding HCT-8, COLO 205, and THP-1 for pIC50 together with Caki-1, COLO 205, and SW-620 approaching 6). Moreover, the range of values in the datasets is even greater than that for non-tumor cells, exceeding 5 logarithmic units everywhere. Thus, the formal parameters of the data in the training sets for tumor cell lines indicate that there were also no obstacles in creating accurate QSAR models using these data.

2.2. QSAR Modeling

QSAR models were made by GUSAR software based on the created training sets that are described in Table 1 and Table 2 (see Section 4). The threshold Q2 > 0.5 was used to estimate the quality of the created QSAR models for further 5-fold cross-validation (5-fold CV). The predictive performance, Q2, was calculated using the leave-one-out cross-validation of the training data during the creation of QSAR models (the scatter plots of predicted vs. known experimental data given during this validation are represented in the Supplement (Figures S1–S35)). All QSAR models used to predict pIC50 values for 17 non-tumor cell lines met the threshold (Table 3). The accuracy of the QSAR model for the prediction of pGI50 values for HUVEC was also high enough (Table 3) excluding the one for MRC-5. The results of the 5-fold cross-validation of QSAR models for non-tumor cell lines (when 20% of compounds from the initial datasets were used as the validation set and 80% became the training set in each iteration) are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Accuracy characteristics for QSAR models for non-tumor cell lines. The thresholds for selection of reasonable QSAR models are R25-fold CV > 0.5 and RMSE5-fold CV < 1.

Table 3 shows that despite the reasonable accuracy of prediction given in full training sets, stricter 5-fold CV revealed seven weak QSAR models predicting pIC50 values (with R25-fold CV value less 0.5) for BEAS-2B, BJ, CCD-18Co, HFF, HFL1, HMEC-1, and NHDF cell lines. As a result, 10 QSAR models predicted pIC50 values and one QSAR model predicted a pGI50 value (with R25-fold CV value over 0.5 and RMSE5-fold CV less than 1) which may be considered acceptable to be employed in toxicological assessment of new compounds. The most accurate QSAR models were obtained for predicting pIC50 values in HaCaT, HEK-293T, and MCF-10A cell lines with R25-fold CV more than 0.8 and RMSE5-fold CV less than 0.5. The average R25-fold CV and RMSE5-fold CV of these models achieved the 0.695 and 0.569 values, respectively. The negative R25-fold CV values for HFL1 and NHDF cell lines could be obtained because a significant number of the highly active compounds in the test set had been predicted to be less active.

QSAR modeling based on the training sets related to tumor cell lines (mentioned in Table 2) displays different patterns (Table 4). The reasonable QSAR models predicted pIC50 values were created only for 12 tumor cell lines (shown in Table 4) of 15 (Q2 > 0.5). At that time, QSAR models predicted pGI50 values for six of eight tumor cell lines revealing Q2 exceeding 0.5.

Table 4.

Accuracy characteristics for QSAR models for tumor cell lines. The thresholds for selection of reasonable QSAR models are R25-fold CV > 0.5 and RMSE5-fold CV < 1.

Table 4 shows that the 5-fold CV procedure (when 20% of compounds from the initial datasets were used as the validation set and 80% became the training set in each iteration) revealed that only eight QSAR models predicted pIC50 values (A-431, Caco-2, COLO 205, HCT-8, HepG2, SW-620, THP-1 and U-937) and predicted pGI50 values (A-431, THP-1 and U-937) with a reasonable accuracy of prediction (R25-fold CV value > 0.5 and RMSE5-fold CV < 1). They may also be considered acceptable to be used in cytotoxic assessment of new compounds. The most accurate QSAR models were for the prediction of pGI50 values in THP-1 and U-937 cell lines with R25-fold CV over 0.8 and RMSE5-fold CV less 0.5. The average R25-fold CV and RMSE5-fold CV of these models have approximately the same values as for non-tumor cell lines: 0.686 and 0.599, respectively. The biological description of the cell lines from Table 3 and Table 4 is given in Table 5.

Table 5.

Description of human non-tumor and tumor cell lines related with the selected QSAR models.

Table 5 shows the variety of cell lines used in various toxicology studies to assess both general and organ-specific toxicity. By using these cell lines, one can evaluate such types of toxicity as hepatotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, immunotoxicity, dermatotoxicity, gastrointestinal toxicity, and lung toxicity. Unfortunately, cell lines associated with important types of toxicity such as cardiotoxicity, bone marrow, and neurotoxicity are not included in the list of cell lines for which it was possible to create acceptable QSAR models.

2.3. Web Application

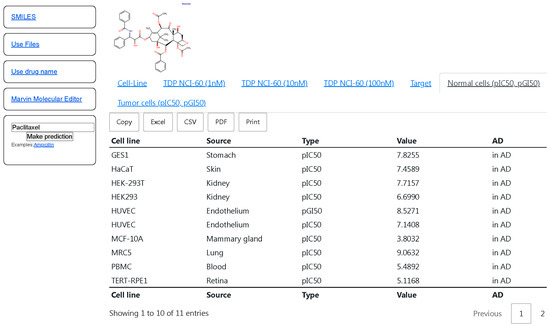

The selected QSAR models (with R25-fold CV value more than 0.5 and RMSE5-fold CV less than 1) based on the results of the 5-fold CV procedure were implemented in CLC-Pred 2.0 (https://way2drug.com/clc-pred/, accessed on 12 December 2025) [18]. This web-application provides users with a possibility to submit the drug name, SMILES strings [62], upload a file in the ‘MOL’ format [63], and draw or insert the structural formula in Marvin JS applet as input data for the prediction. The prediction is output in the form of tables with pIC50 and pGI50 values and the estimation of applicability domain or each cell line is represented in two tabs—‘Normal cells (pIC50, pGI50)’ and ‘Tumor cells (pIC50, pGI50)’ for non-tumor and tumor cell lines, respectively (Figure 1). By clicking on the title of the column, users can sort the prediction results based on the data from the column. The prediction results may be copied to the clipboard or exported to CSV, Excel, or PDF files, and also printed.

Figure 1.

The interface of CLC-Pred with the prediction results of pIC50, pGI50 values on non-tumor cell lines for paclitaxel. The titles of the columns mean the following: “Cell line”—name of cell lines; “Type”—pIC50 or pGI50; “Value”—predicted pIC50, pGI50 values; “AD”—Applicability Domain (“In AD”—in the Applicability Domain, “out of AD”—out of Applicability Domain.

Figure 1 displays the high predicted pIC50 values (more 6) of cytotoxicity for the most non-tumor cell lines for anti-tumor agent paclitaxel. Although paclitaxel is widely used in the treatment of different types of solid tumors, such as breast, colon, prostate, non-small-cell lung, and ovarian cancers, it is also known for its multiorgan toxicity [64]. Therefore, the presented predicted results for paclitaxel reflect its potential to cause toxic effects observed in the clinic.

3. Discussion

The ability to quantitatively predict IC50 and GI50 values for sets of non-tumor and tumor cell lines provides an opportunity to select the most promising drug candidates at the early stages of drug development. This can be best demonstrated using anticancer drugs comparing paclitaxel (Taxol), that has a broad spectrum of cytotoxic effect on both non-tumor and tumor cells, with the targeted anticancer drugs trametinib and dabrafenib. Trametinib, which is an MEK inhibitor, and dabrafenib, which is a BRAF inhibitor, are used to treat solid tumors, lymphomas, or multiple myeloma with BRAF V600E driver mutation [65]. The prediction results of pIC50 and pGI50 values made by the created QSAR models are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Prediction results for paclitaxel, trametinib, and dabrafenib.

Table 6 shows that the prediction results for paclitaxel include high values of pIC50 and pGI50 (more 7) for many non-tumor and tumor cell lines. It correlates with the knowledge on general toxicity [66] and organ-specific toxicity of paclitaxel: gastrointestinal toxicity (esophagus, stomach, small intestine) [67], hepatotoxicity [68], endothelium toxicity [69], lung toxicity [70], skin toxicity [71], and immunotoxicity [72,73] associated with its mechanism of action—polymerized microtubule accumulation and mitotic arrest. At the same time, the high values of pIC50 and pGI50 for some tumor cell lines reflect several main fields of therapeutic applications of paclitaxel: melanoma, lung, and esophageal cancer [74]. Despite the high predicted cytotoxicity values for non-tumor cell lines averaging 6.889, the average predicted cytotoxicity value for tumor cells is approximately four times higher at 7.502 (7.502 − 6.889 = 0.613 in logarithmic scale). The log-transformed value of 0.613 corresponds to a decimal value of 4.1. It means that paclitaxel is, on average, more cytotoxic against tumor cells than non-tumor ones. This reflects the existence of a reasonable therapeutic window (TI—Therapeutic Index = 4.1) for its clinical use. Hertz with co-authors also claimed that paclitaxel is similar to many anticancer agents in having a relatively narrow therapeutic window [75].

The prediction results for trametinib and dabrafenib indicate that they may be less toxic than paclitaxel. Their mean predicted cytotoxicity values for non-tumor cell lines were 5.604 and 5.328, respectively. Trametinib and dabrafenib are targeted therapy drugs, and they are considered less toxic than chemotherapy drugs such paclitaxel [76,77]. The low predicted values of cytotoxicity for trametinib and dabrafenib on non-tumor cell lines correlate with the absence of dangerous organ-specific toxic effects of these drugs which may be related to cytotoxicity in these cell lines [78]. Nevertheless, the prediction results with cytotoxic values higher than average ones in non-tumor cell lines may be associated with some types of adverse drug reactions of these drugs. Skin-related toxic effects, hypertension, and diarrhea caused by trametinib [79] may be associated with the prediction of high cytotoxic action on skin A-431, endothelial HUVEC [80], and colon (COLO205, HCT-8, SW-620) cell lines, respectively. Dabrafenib also reveals cutaneous adverse reactions and diarrhea [81] that may be associated with the prediction results for skin A-431 and colon (COLO205, HCT-8) cell lines, respectively. Moreover, Table 6 includes high predicted values of cytotoxicity for blood cells. While less frequent and severe than other side effects like pyrexia and skin toxicity, hematologic adverse reactions such as anemia, leukopenia, and neutropenia for dabrafenib [82] and anemia for trametinib [83] have also been reported. The mean predicted cytotoxicity values of trametinib and dabrafenib for tumor cell lines were 6.241 and 6.119, respectively. These values indicate that the cytotoxicity of trametinib and dabrafenib on tumor cell lines is higher than on non-tumor cell lines. The difference between the average predicted cytotoxic values of these drugs for non-tumor and tumor cell lines also displays the existence of a therapeutic interval. It is higher for dabrafenib (6.119 − 5.328 = 0.791 in logarithmic scale) than for trametinib (6.241 − 5.604 = 0.637 in logarithmic scale). The log-transformed values of 0.791 and 0.637 correspond to decimal values of 6.2 and 4.3, respectively, reflecting the estimation of therapeutic indexes of dabrafenib and trametinib. This correlates with the data on the narrow therapeutic window for these drugs [84,85]. There are no strict criteria for TI. TI ≥ 10 is considered preferable for selecting universal drugs and TI > 5 is a criterion for considering a drug candidate for further preclinical study [86]. Nevertheless, a low TI (<2), known as a narrow therapeutic index drug, is also used for some severe diseases [87].

This illustration along with the comparison of prediction results of pIC50 and pGI50 values for paclitaxel, trametinib, and dabrafenib show the usefulness of the created QSAR models for the estimation of possible toxicity of drug-candidates and their potential in terms of the presence of a therapeutic window. In the future, when data on new drugs become available, it would be advisable to conduct similar studies on a larger external set to more accurately assess the possibility of using the created QSAR models to determine the therapeutic interval and toxicity of novel pharmaceutical agents.

Regarding the QSAR models themselves, the resulting model analysis revealed that the quality of QSAR predictions depends significantly on the cell line type. In particular, for some lines, models with high R25-fold CV (>0.6) and RMSE5-fold CV (<0.8) values were obtained, indicating high accuracy and reproducibility of the predictions. This is typical, for example, of the HaCaT, GES-1, and HUVEC cell lines that have proven to be successful in cytotoxicology studies, and which exhibit a stable phenotype in vitro.

Organ-specific characteristics also influence the cytotoxic response. For example, cell lines mimicking barrier tissues (skin-HaCaT, intestine-Caco-2, respiratory tract-Calu-3) demonstrated specific sensitivities to certain classes of compounds, which is important to consider when interpreting the results. Endothelial cells (HUVEC) also demonstrated highly reproducible cytotoxic effects, making them useful for assessing angiotoxicity. Liver cell lines (HepG2) have metabolic activity allowing for the impact of compound biotransformation to be considered; however, their predictive accuracy may vary depending on the specific compounds tested.

The comparison of non-tumor and tumor cell lines revealed some trends: in general, models built on non-tumor cells are characterized by higher stability; however, they are sometimes inferior in accuracy to models based on tumor lines, especially if the latter have a pronounced mitotic potential (e.g., Caki-1, A549). This is because tumor lines often have a simplified response to chemical exposure due to impaired regulation of apoptosis and the cell cycle, which facilitates the detection of cytotoxic effects. Non-tumor cell lines, in contrast, are closer to physiological norms, making their results more relevant for assessing potential toxicity in the body, but this requires a more precise modeling approach. Due to the narrow therapeutic index of certain drugs, it is crucial to have highly accurate QSAR models. However, not all QSAR models achieve high predictive performance. To address this limitation and enhance the reliability of the therapeutic index estimates, the following strategies can be employed:

- Prioritizing high-accuracy QSAR models: Selecting prediction results from models with the highest accuracy, such as models for predicting IC50 values in non-tumor cell lines (HaCaT, HEK-293T, MCF-10A) as well as in tumor cell lines (COLO 205, HCT-8), and GI50 values in tumor cell lines (THP-1, U-937)

- Leveraging models with medium accuracy but large training sets: Consider QSAR models with moderate predictive performance if they are built on extensive training datasets, e.g., for non-tumor cell lines (HEK-293, MRC-5) and tumor cell lines (A-431, THP-1, U-937). Such models typically cover a broader chemical space and exhibit greater robustness due to the diversity of the training data

- Excluding predictions beyond the applicability domain (AD): Avoid using predictions marked as “out of AD” that can be identified in the following cases.

- the query structure exhibits less than 70 % similarity to any compound in the training set

- the predicted value deviates from the values of the three most similar compounds in the training set by more than the RMSE values of a model.

In summary, although the accuracy of individual QSAR models may vary, their combined use can help to overcome the limitations of any one model and provide a more reliable estimation of the therapeutic index.

The results show that the quality of QSAR models depends on both the amount of experimental data and the cell line type. Immune system cell lines (THP-1, U-937) demonstrated better predictive power, possibly due to a more robust biological response and lower heterogeneity. However, for the lines with high biological heterogeneity (e.g., COLO 205 (pGI50) and A549), the models were less accurate.

Therefore, when developing and using QSAR models for cytotoxicity prediction, it is important to consider both the biological nature of the cell line and the specifics of its application. Combining tumor and non-tumor models provides a more comprehensive understanding of a compound’s toxicity profile and increases the reliability of in silico assessments.

Increasing the number of experimental IC50 and GI50 values for both active and inactive compounds will lead to the creation of new efficient and reliable QSAR models for a wide range of cell lines and will help to efficiently discover new promising drugs at an early stage of their development. The current implementation of GUSAR is based on atomic neighborhood descriptors QNA and MNA, as well as several physico-chemical descriptors. It also uses the original SCR (Self-Consistent Regression) and RBF–SCR (Radial Basis Function network using SCR) algorithms. The use of additional molecular descriptors and machine learning algorithms to improve the accuracy and predictivity of QSAR models for cytotoxicity prediction may be the subject of discussion. However, as the widespread use of QSAR has demonstrated, the current accuracy of the obtained models is primarily limited by the quantity and accuracy of the experimental data used for training and testing [20,88,89].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data

ATCC (available in October 2025) was used for selection of human cell lines related to toxicology studies. The query ‘Toxicology’ and filters ‘Human cells’ in ‘Product category’ and ‘Toxicology’ in ‘Product application’ of query sections were used, and more than 500 human cell lines were selected. The records were analyzed by the number of ‘Product Citations’, and human cell lines with the highest number of citations (>1000) were selected. The information on human non-tumor cell lines with a significant number of cytotoxic compounds from our previous study [18] was also used for the creation of a list of human cell lines for further investigation. As a result, a list of 33 human non-tumor cell lines and 24 tumor cell lines was created.

The ChEMBL database (v. 33) was used as a source of data on structures of compounds and experimental IC50 and GI50 values. IC50 (the inhibitor concentration that causes a 50% reduction in target activity) is one of the most common parameters for assessing cytotoxicity (in this case, the target is a cell line). GI50 (the concentration that results in 50% inhibition of cell growth) is used in antiproliferative activity studies. These parameters characterize the interaction of a compound with a biological target and allow for comparison of their toxicity and efficacy. A search of compounds with exact IC50 or GI50 values in nM was performed for each selected cell line. IC50 or GI50 values were converted to logarithmic views of pIC50 (−log10(IC50/106) and pGI50 (−log10(GI50/106). Duplicate records with the same structures were consolidated by median pIC50 or pGI50 calculation.

4.2. GUSAR Software

QSAR models were made by GUSAR software [8,20,21], which uses Quantitative Neighborhoods of Atoms (QNA) [20] and Multilevel Neighborhoods of Atoms (MNA) descriptors [88] to describe structural formulae of compounds and the SCR–RBF algorithm [89] to build quantitative structure–activity relationships. Whole-molecule descriptors including topological length, topological volume, lipophilicity, number of positive charges, number of negative charges, number of hydrogen bond acceptors, the number of hydrogen bond donors, the number of aromatic atoms, molecular weight, and the number of halogen atoms were also used in GUSAR [21]. The applicability domain estimation is also implemented in GUSAR. It is calculated during the prediction of query compounds. An estimation of the applicability domain (AD) is based on its simultaneous calculation by three methods (similarity, leverage, and accuracy assessment). These methods of AD calculation were used by default [21]. It is enough for one of the methods to signal that the structure is outside the AD for this inscription to appear in the prediction results. In this case, the prediction results should be treated more critically.

For each training set, 320 QSAR models were created by GUSAR with a modified calculation of descriptors and regression coefficients. Based on the internal leave-many-out cross-validation (LMO CV, when 20% from the training set were used as an internal test, repeated 5 times), single QSAR models with the reasonable values (R2 > 0.5, Q2 > 0.5 for the training set and R2 of internal LMO CV > 0.5) were selected for the creation of the final consensus QSAR models for each training set.

R2, coefficient of determination and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) were calculated as follows:

where yexp—experimental value, ypred—predicted value, ymean—average value of experimental values in a training set, and n is the number of objects. The R2 values represent the relationship between the predicted and the observed values of the measured biological activity [21] and R2 values closer to 1 indicate successful predictions. R2 of the internal LMO CV was calculated as R2 (Equation (1)). Q2 is a cross-validated R2 calculated during the leave-one-out cross-validation procedure using the data from a training set.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms262412063/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.L.; methodology, A.A.L., D.A.F., and V.V.P.; software, A.V.R. and D.A.F.; investigation, E.Y.L. and A.A.L.; data curation, E.Y.L., E.S.M., and A.A.L., validation, E.Y.L. and A.A.L.; formal analysis, S.M.I.; original draft preparation, E.Y.L., A.V.D., and A.A.L.; review and editing, A.A.L., D.A.F., and V.V.P.; supervision, A.A.L., D.A.F., and V.V.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grant No. 25-15-00300 (Preclinical toxicology in silico) from the Russian Science Foundation (https://rscf.ru/project/25-15-00300/, accessed on 12 December 2025).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

A web interface implementing the selected QSAR model is available at https://way2drug.com/clc-pred/ (accessed on 12 December 2025) for prediction using chemical structures, entering a SMILES string or searching by a common compound name.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ATCC | American Type Culture Collection |

| CLC-Pred | Cell Line Cytotoxicity Predictor (web application) |

| HUVEC | Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells |

| MNA | Multilevel Neighborhoods of Atoms |

| OECD | Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development |

| PBMC | Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells |

| RBF–SCR | Radial Basis Function–Self Consistent Regression |

| QNA | Quantitative Neighborhoods of Atoms |

| QSAR | Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship |

| TI | Therapeutic Index |

References

- Arzumanian, V.A.; Kiseleva, O.I.; Poverennaya, E.V. The Curious Case of the HepG2 Cell Line: 40 Years of Expertise. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnula, V.L.; Yankaskas, J.R.; Chang, L.; Virtanen, I.; Linnala, A.; Kang, B.H.; Crapo, J.D. Primary and immortalized (BEAS 2B) human bronchial epithelial cells have significant antioxidative capacity in vitro. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1994, 11, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocherova, I.; Bryja, A.; Mozdziak, P.; Angelova Volponi, A.; Dyszkiewicz-Konwińska, M.; Piotrowska-Kempisty, H.; Antosik, P.; Bukowska, D.; Bruska, M.; Iżycki, D.; et al. Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs) Co-Culture with Osteogenic Cells: From Molecular Communication to Engineering Prevascularised Bone Grafts. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, J.P.; Rees, S.; Kalindjian, S.B.; Philpott, K.L. Principles of early drug discovery. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 162, 1239–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geraghty, R.J.; Capes-Davis, A.; Davis, J.M.; Downward, J.; Freshney, R.I.; Knezevic, I.; Lovell-Badge, R.; Masters, J.R.; Meredith, J.; Stacey, G.N.; et al. Guidelines for the use of cell lines in biomedical research. Br. J. Cancer 2014, 111, 1021–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bairoch, A. The Cellosaurus, a Cell-Line Knowledge Resource. J. Biomol. Tech. 2018, 29, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zdrazil, B.; Felix, E.; Hunter, F.; Manners, E.J.; Blackshaw, J.; Corbett, S.; de Veij, M.; Ioannidis, H.; Lopez, D.M.; Mosquera, J.F.; et al. The ChEMBL Database in 2023: A drug discovery platform spanning multiple bioactivity data types and time periods. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D1180–D1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagunin, A.A.; Sezganova, A.S.; Muraviova, E.S.; Rudik, A.V.; Filimonov, D.A. BC CLC-Pred: A freely available web-application for quantitative and qualitative predictions of substance cytotoxicity in relation to human breast cancer cell lines. SAR QSAR Environ. Res. 2024, 35, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Chen, J.; Cheng, T.; Gindulyte, A.; He, J.; He, S.; Li, Q.; Shoemaker, B.A.; Thiessen, P.A.; Yu, B.; et al. PubChem 2025 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D1516–D1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ICH M7(R2). Available online: https://database.ich.org/sites/default/files/ICH_M7(R2)_Guideline_Step4_2023_0216_0.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- OECD QSAR Validation Principles. 2007. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/chemicalsafety/risk-assessment/37849783.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- OECD (Q)SAR Assessment Framework. 2023. Available online: https://one.oecd.org/document/ENV/CBC/MONO(2023)32/en/pdf (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- FDA Predictive Toxicology Roadmap. 2017. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/science-research/about-science-research-fda/fdas-predictive-toxicology-roadmap (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Avila, A.M.; Bebenek, I.; Bonzo, J.A.; Bourcier, T.; Davis Bruno, K.L.; Carlson, D.B.; Dubinion, J.; Elayan, I.; Harrouk, W.; Lee, S.L.; et al. An FDA/CDER perspective on nonclinical testing strategies: Classical toxicology approaches and new approach methodologies (NAMs). Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2020, 114, 104662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMA NAMs Horizon Scanning Report. 2025. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/report/new-approach-methodologies-eu-horizon-scanning-report_en.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Feitosa, F.L.; F Cabral, V.; Sanches, I.H.; Silva-Mendonca, S.; Borba, J.V.V.B.; Braga, R.C.; Andrade, C.H. Cyto-Safe: A Machine Learning Tool for Early Identification of Cytotoxic Compounds in Drug Discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64, 9056–9062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagunin, A.A.; Dubovskaja, V.I.; Rudik, A.V.; Pogodin, P.V.; Druzhilovskiy, D.S.; Gloriozova, T.A.; Filimonov, D.A.; Sastry, N.G.; Poroikov, V.V. CLC-Pred: A freely available web-service for in silico prediction of human cell line cytotoxicity for drug-like compounds. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagunin, A.A.; Rudik, A.V.; Pogodin, P.V.; Savosina, P.I.; Tarasova, O.A.; Dmitriev, A.V.; Ivanov, S.M.; Biziukova, N.Y.; Druzhilovskiy, D.S.; Filimonov, D.A.; et al. CLC-Pred 2.0: A Freely Available Web Application for In Silico Prediction of Human Cell Line Cytotoxicity and Molecular Mechanisms of Action for Druglike Compounds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, R.P.; Hansch, C. A QSAR study on the cytotoxicity of podophyllotoxin analogues against various cancer cell lines. Med. Chem. 2010, 6, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonov, D.A.; Zakharov, A.V.; Lagunin, A.A.; Poroikov, V.V. QNA-based ‘Star Track’ QSAR approach. SAR QSAR Environ. Res. 2009, 20, 679–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagunin, A.A.; Geronikaki, A.; Eleftheriou, P.; Pogodin, P.V.; Zakharov, A.V. Rational use of heterogeneous data in quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling of cyclooxygenase/lipoxygenase inhibitors. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2019, 59, 713–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, K.; Ambure, P.; Kar, S. How Precise Are Our Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship Derived Predictions for New Query Chemicals? ACS Omega 2018, 3, 11392–11406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Gao, Y.; Zhu, L.; Song, H.; Zhao, L.; Liu, A.; Zhang, G.; Shi, G. Establishment and characterization of a GES-1 human gastric epithelial cell line stably expressing miR-23a. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 16, 977–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Liu, S.; Yin, Z.; Liang, P.; Wang, C.; Zhu, H.; Liu, Y.; Ou, S.; Li, G. Rutin alleviated acrolein-induced cytotoxicity in Caco-2 and GES-1 cells by forming a cyclic hemiacetal product. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 976400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukamp, P.; Petrussevska, R.T.; Breitkreutz, D.; Hornung, J.; Markham, A.; Fusenig, N.E. Normal keratinization in a spontaneously immortalized aneuploid human keratinocyte cell line. J. Cell Biol. 1988, 106, 761–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forouz, F.; Mohammed, Y.; Shobeiri Nejad, H.S.A.; Roberts, M.S.; Grice, J.E. In vitro screening of topical formulation excipients for epithelial toxicity in cancerous and non-cancerous cell lines. EXCLI J. 2023, 22, 1173–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, G.; Morse, S.; Ararat, M.; Graham, F.L. Preferential transformation of human neuronal cells by human adenoviruses and the origin of HEK 293 cells. FASEB J. 2002, 16, 869–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, E.; Chin, C.S.H.; Lim, Z.F.S.; Ng, S.K. HEK293 Cell Line as a Platform to Produce Recombinant Proteins and Viral Vectors. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 796991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pehlivan, V.F.; Pehlivan, B.; Duran, E.; Koyuncu, İ. Comparing the Effects of Propofol and Thiopental on Human Renal HEK-293 Cells with a Focus on Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Production, Cytotoxicity, and Apoptosis: Insights Into Dose-Dependent Toxicity. Cureus 2024, 16, e74120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, R.; Hou, P.; Bi, K.; Chen, X. Nephrotoxicity evaluation of a new cembrane diterpene from Euphorbiae pekinensis Radix with HEK 293T cells and the toxicokinetics study in rats using a sensitive and reliable UFLC-MS/MS. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2016, 119, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y. Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs) in Pharmacology and Toxicology: A Review. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2025, 45, 2512–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, S.M.; Dane, M.A.; Smith, R.L.; Devlin, K.L.; McLean, I.C.; Derrick, D.S.; Mills, C.E.; Subramanian, K.; London, A.B.; Torre, D.; et al. A multi-omic analysis of MCF10A cells provides a resource for integrative assessment of ligand-mediated molecular and phenotypic responses. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, N.; Silva, S.; Duarte, D.; Crista, D.M.A.; Pinto da Silva, L.; Esteves da Silva, J.C.G. Normal breast epithelial MCF-10A cells to evaluate the safety of carbon dots. RSC Med. Chem. 2020, 12, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uemura, K.; Sasaki, M.; Sanaki, T.; Toba, S.; Takahashi, Y.; Orba, Y.; Hall, W.W.; Maenaka, K.; Sawa, H.; Sato, A. MRC5 cells engineered to express ACE2 serve as a model system for the discovery of antivirals targeting SARS-CoV-2. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlasceanu, A.-M.; Baconi, D.L.; Galateanu, B.; Stan, M.; Balalau, C. Comparative Cytotoxicity Study of Nicotine and Cotinine on MRC-5 Cell Line. J. Mind Med. Sci. 2018, 5, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, P.; Kemppainen, E.; Orešič, M. Perspectives on Systems Modeling of Human Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2018, 4, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourahmad, J.; Salimi, A. Isolated Human Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell (PBMC), a Cost Effective Tool for Predicting Immunosuppressive Effects of Drugs and Xenobiotics. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2015, 14, 979. [Google Scholar]

- Hindul, N.L.; Jhita, A.; Oprea, D.G.; Hussain, T.A.; Gonchar, O.; Campillo, M.A.M.; O’Regan, L.; Kanemaki, M.T.; Fry, A.M.; Hirota, K.; et al. Construction of a human hTERT RPE-1 cell line with inducible Cre for editing of endogenous genes. Biol. Open 2022, 11, bio059056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, P.; Serviss, J.T.; Lundbäck, T.; Bancaro, N.; Mazurkiewicz, M.; Kolosenko, I.; Yu, D.; Haraldsson, M.; D’Arcy, P.; Linder, S.; et al. A drug screening assay on cancer cells chronically adapted to acidosis. Cancer Cell Int. 2018, 18, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharti, K.; den Hollander, A.I.; Lakkaraju, A.; Sinha, D.; Williams, D.S.; Finnemann, S.C.; Bowes-Rickman, C.; Malek, G.; D’Amore, P.A. Cell culture models to study retinal pigment epithelium-related pathogenesis in age-related macular degeneration. Exp. Eye Res. 2022, 222, 109170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurent, A.; Abdel-Sayed, P.; Hirt-Burri, N.; Scaletta, C.; Michetti, M.; de Buys Roessingh, A.; Raffoul, W.; Applegate, L.A. Evolution of Diploid Progenitor Lung Cell Applications: From Optimized Biotechnological Substrates to Potential Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients in Respiratory Tract Regenerative Medicine. Cells 2021, 10, 2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrahman, F.G.; Sabour, R.; El-Gilil, S.M.A.; Mehany, A.B.M.; Taha, E.A. Design, synthesis, biological evaluation and molecular docking study of new pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidines as PIM kinase inhibitors and apoptosis inducers. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1295, 136811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defize, L.H.; Arndt-Jovin, D.J.; Jovin, T.M.; Boonstra, J.; Meisenhelder, J.; Hunter, T.; de Hey, H.T.; de Laat, S.W. A431 cell variants lacking the blood group A antigen display increased high affinity epidermal growth factor-receptor number, protein-tyrosine kinase activity, and receptor turnover. J. Cell Biol. 1988, 107, 939–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Favero, G.; Woelflingseder, L.; Janker, L.; Neuditschko, B.; Seriani, S.; Gallina, P.; Sbaizero, O.; Gerner, C.; Marko, D. Deoxynivalenol induces structural alterations in epidermoid carcinoma cells A431 and impairs the response to biomechanical stimulation. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, I.J.; Raub, T.J.; Borchardt, R.T. Characterization of the human colon carcinoma cell line (Caco-2) as a model system for intestinal epithelial permeability. Gastroenterology 1989, 96, 736–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, A. Cytotoxicity and intestinal permeability of phycotoxins assessed by the human Caco-2 cell model. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 249, 114447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semple, T.U.; Quinn, L.A.; Woods, L.K.; Moore, G.E. Tumor and lymphoid cell lines from a patient with carcinoma of the colon for a cytotoxicity model. Cancer Res. 1978, 38, 1345–1355. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kuo, C.T.; Chang, C.; Lee, W.S. Folic acid inhibits COLO-205 colon cancer cell proliferation through activating the FRα/c-SRC/ERK1/2/NFκB/TP53 pathway: In vitro and in vivo studies. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, B.; Szemerédi, N.; Kúsz, N.; Kiss, T.; Csupor-Löffler, B.; Tsai, Y.C.; Rácz, B.; Spengler, G.; Csupor, D. Antiproliferative and cytotoxic effects of sesquiterpene lactones isolated from Ambrosia artemisiifolia on human adenocarcinoma and normal cell lines. Pharm. Biol. 2022, 60, 1511–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.E.; Kang, J.S.; Lee, W.J. Vitamin C Induces Apoptosis in Human Colon Cancer Cell Line, HCT-8 Via the Modulation of Calcium Influx in Endoplasmic Reticulum and the Dissociation of Bad from 14-3-3β. Immune Netw. 2012, 12, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouzel, I.U.; Pohlentz, G.; Schmitz, J.S.; Steil, D.; Humpf, H.-U.; Karch, H.; Müthing, J. Shiga Toxin Glycosphingolipid Receptors in Human Caco-2 and HCT-8 Colon Epithelial Cell Lines. Toxins 2017, 9, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Hof, W.F.; Coonen, M.L.; van Herwijnen, M.; Brauers, K.; Wodzig, W.K.; van Delft, J.H.; Kleinjans, J.C. Classification of hepatotoxicants using HepG2 cells: A proof of principle study. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2014, 27, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stragand, J.J.; Barlogie, B.; White, R.A.; Drewinko, B. Biological properties of the human colonic adenocarcinoma cell line SW 620 grown as a xenograft in the athymic mouse. Cancer Res. 1981, 41 Pt 1, 3364–3369. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bošković, J.; Dobričić, V.; Keta, O.; Korićanac, L.; Žakula, J.; Dinić, J.; Jovanović Stojanov, S.; Pavić, A.; Čudina, O. Unveiling Anticancer Potential of COX-2 and 5-LOX Inhibitors: Cytotoxicity, Radiosensitization Potential and Antimigratory Activity against Colorectal and Pancreatic Carcinoma. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, S.; Yamabe, M.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Kobayashi, Y.; Konno, T.; Tada, K. Establishment and characterization of a human acute monocytic leukemia cell line (THP-1). Int. J. Cancer 1980, 26, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, I.; Pouzet, C.; Brulas, M.; Bauza, E.; Botto, J.M.; Domloge, N. Evaluation of THP-1 cell line as an in vitro model for long-term safety assessment of new molecules. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2013, 35, 568–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nukada, Y.; Ashikaga, T.; Sakaguchi, H.; Sono, S.; Mugita, N.; Hirota, M.; Miyazawa, M.; Ito, Y.; Sasa, H.; Nishiyama, N. Predictive performance for human skin sensitizing potential of the human cell line activation test (h-CLAT). Contact Dermat. 2011, 65, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malkova, A.; Svadlakova, T.; Singh, A.; Kolackova, M.; Vankova, R.; Borsky, P.; Holmannova, D.; Karas, A.; Borska, L.; Fiala, Z. In Vitro Assessment of the Genotoxic Potential of Pristine Graphene Platelets. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundström, C.; Nilsson, K. Establishment and characterization of a human histiocytic lymphoma cell line (U-937). Int. J. Cancer 1976, 17, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piroird, C.; Ovigne, J.M.; Rousset, F.; Martinozzi-Teissier, S.; Gomes, C.; Cotovio, J.; Alépée, N. The Myeloid U937 Skin Sensitization Test (U-SENS) addresses the activation of dendritic cell event in the adverse outcome pathway for skin sensitization. Toxicol. Vitr. 2015, 29, 901–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.K.; Takenaka, M.; Kobori, M.; Nakahara, K.; Isobe, S.; Tsushida, T. Apoptosis, necrosis and cell proliferation-inhibition by cyclosporine A in U937 cells (a human monocytic cell line). Pharmacol. Res. 2006, 53, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weininger, D. SMILES, a chemical language and information system. 1. Introduction to methodology and encoding rules. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 1988, 28, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalby, A.; Nourse, J.G.; Hounshell, W.D.; Gushurst, A.K.I.; Grier, D.L.; Leland, B.A.; Laufer, J. Description of several chemical structure file formats used by computer programs developed at Molecular Design Limited. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 1992, 32, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, A.G.; Fawzi, S.F.; Elmorsi, R.M.; George, M.Y. Paclitaxel-induced adverse effects: Insights into multi-organ toxicities and molecular mechanisms. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2025. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, A.K.S.; Li, S.; Macrae, E.R.; Park, J.I.; Mitchell, E.P.; Zwiebel, J.A.; Chen, H.X.; Gray, R.J.; McShane, L.M.; Rubinstein, L.V.; et al. Dabrafenib and Trametinib in Patients with Tumors with BRAFV600E Mutations: Results of the NCI-MATCH Trial Subprotocol H. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 3895–3904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markman, M. Management of toxicities associated with the administration of taxanes. Expert Opin.T Drug Saf. 2003, 2, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hruban, R.H.; Yardley, J.H.; Donehower, R.C.; Boitnott, J.K. Epithelial necrosis in the gastrointestinal tract associated with polymerized microtubule accumulation and mitotic arrest. Cancer 1989, 63, 1944–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Vernooij, R.; van Nuland, M.; Smeijsters, E.; Devriese, L.; Mohammad, N.H.; Hermens, T.; Stammers, J.; Swart, C.; Egberts, T.; et al. Impaired liver function: Effect on paclitaxel toxicity, dose modifications and overall survival. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morbidelli, L.; Donnini, S.; Ziche, M. Targeting endothelial cell metabolism for cardio-protection from the toxicity of antitumor agents. Cardiooncology 2016, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velimirovic, M.; Brignola, M.; Chheng, E.; Smith, M.; Hassan, K.A. Management of Pulmonary Toxicities Associated with Systemic Therapy in Non Small Cell Lung Cancer. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2024, 25, 1297–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibaud, V.; Lebœuf, N.R.; Roche, H.; Belum, V.R.; Gladieff, L.; Deslandres, M.; Montastruc, M.; Eche, A.; Vigarios, E.; Dalenc, F.; et al. Dermatological adverse events with taxane chemotherapy. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2016, 26, 427–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symons, R.; Heath, F.; Duggan, J.; Bui, K.T.; Byun, L.; Friedlander, M.; Lee, Y.C. Rates of paclitaxel hypersensitivity reactions using a modified Markman’s infusion protocol as primary prophylaxis. Support. Care Cancer 2024, 32, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onetto, N.; Canetta, R.; Winograd, B.; Catane, R.; Dougan, M.; Grechko, J.; Burroughs, J.; Rozencweig, M. Overview of Taxol safety. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 1993, 15, 131–139. [Google Scholar]

- Awosika, A.O.; Farrar, M.C.; Jacobs, T.F. Paclitaxel. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536917/ (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Hertz, D.L.; Joerger, M.; Bang, Y.J.; Mathijssen, R.H.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, L.; Gandara, D.; Stahl, M.; Monk, B.J.; Jaehde, U.; et al. Paclitaxel therapeutic drug monitoring—International association of therapeutic drug monitoring and clinical toxicology recommendations. Eur. J. Cancer 2024, 202, 114024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schadendorf, D.; Amonkar, M.M.; Milhem, M.; Grotzinger, K.; Demidov, L.V.; Rutkowski, P.; Garbe, C.; Dummer, R.; Hassel, J.C.; Wolter, P.; et al. Functional and symptom impact of trametinib versus chemotherapy in BRAF V600E advanced or metastatic melanoma: Quality-of-life analyses of the METRIC study. Ann. Oncol. 2014, 25, 700–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cebollero, A.; Puértolas, T.; Pajares, I.; Calera, L.; Antón, A. Comparative safety of BRAF and MEK inhibitors (vemurafenib, dabrafenib and trametinib) in first-line therapy for BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 5, 458–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, S.J.; Corrie, P.G. Management of BRAF and MEK inhibitor toxicities in patients with metastatic melanoma. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2015, 7, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thota, R.; Johnson, D.B.; Sosman, J.A. Trametinib in the treatment of melanoma. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2015, 15, 735–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmashankar, K.; Widlansky, M.E. Vascular endothelial function and hypertension: Insights and directions. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2010, 12, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowyer, S.; Lee, R.; Fusi, A.; Lorigan, P. Dabrafenib and its use in the treatment of metastatic melanoma. Melanoma Manag. 2015, 2, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabanillas, M.E.; Patel, A.; Danysh, B.P.; Dadu, R.; Kopetz, S.; Falchook, G. BRAF inhibitors: Experience in thyroid cancer and general review of toxicity. Horm. Cancer 2015, 6, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garutti, M.; Bergnach, M.; Polesel, J.; Palmero, L.; Pizzichetta, M.A.; Puglisi, F. BRAF and MEK Inhibitors and Their Toxicities: A Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2022, 15, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravix, A.; Bandiera, C.; Cardoso, E.; Lata-Pedreira, A.; Chtioui, H.; Decosterd, L.A.; Wagner, A.D.; Schneider, M.P.; Csajka, C.; Guidi, M. Population Pharmacokinetics of Trametinib and Impact of Nonadherence on Drug Exposure in Oncology Patients as Part of the Optimizing Oral Targeted Anticancer Therapies Study. Cancers 2024, 16, 2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakirouchenane, D.; Guégan, S.; Csajka, C.; Jouinot, A.; Heidelberger, V.; Puszkiel, A.; Zehou, O.; Khoudour, N.; Courlet, P.; Kramkimel, N.; et al. Population Pharmacokinetics/Pharmacodynamics of Dabrafenib Plus Trametinib in Patients with BRAF-Mutated Metastatic Melanoma. Cancers 2020, 12, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Jin, E.; Day, P.J. Use of Drug Sensitisers to Improve Therapeutic Index in Cancer. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyson, R.J.; Park, C.C.; Powell, J.R.; Patterson, J.H.; Weiner, D.; Watkins, P.B.; Gonzalez, D. Precision Dosing Priority Criteria: Drug, Disease, and Patient Population Variables. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagunin, A.; Zakharov, A.; Filimonov, D.; Poroikov, V. QSAR Modelling of Rat Acute Toxicity on the Basis of PASS Prediction. Mol. Inform. 2011, 30, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakharov, A.V.; Peach, M.L.; Sitzmann, M.; Nicklaus, M.C. A new approach to radial basis function approximation and its application to QSAR. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2014, 54, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).