Carbonic Anhydrase 3 Overexpression Modulates Signalling Pathways Associated with Cellular Stress Resilience and Proteostasis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. CA3 Overexpression and Transcriptomics Study

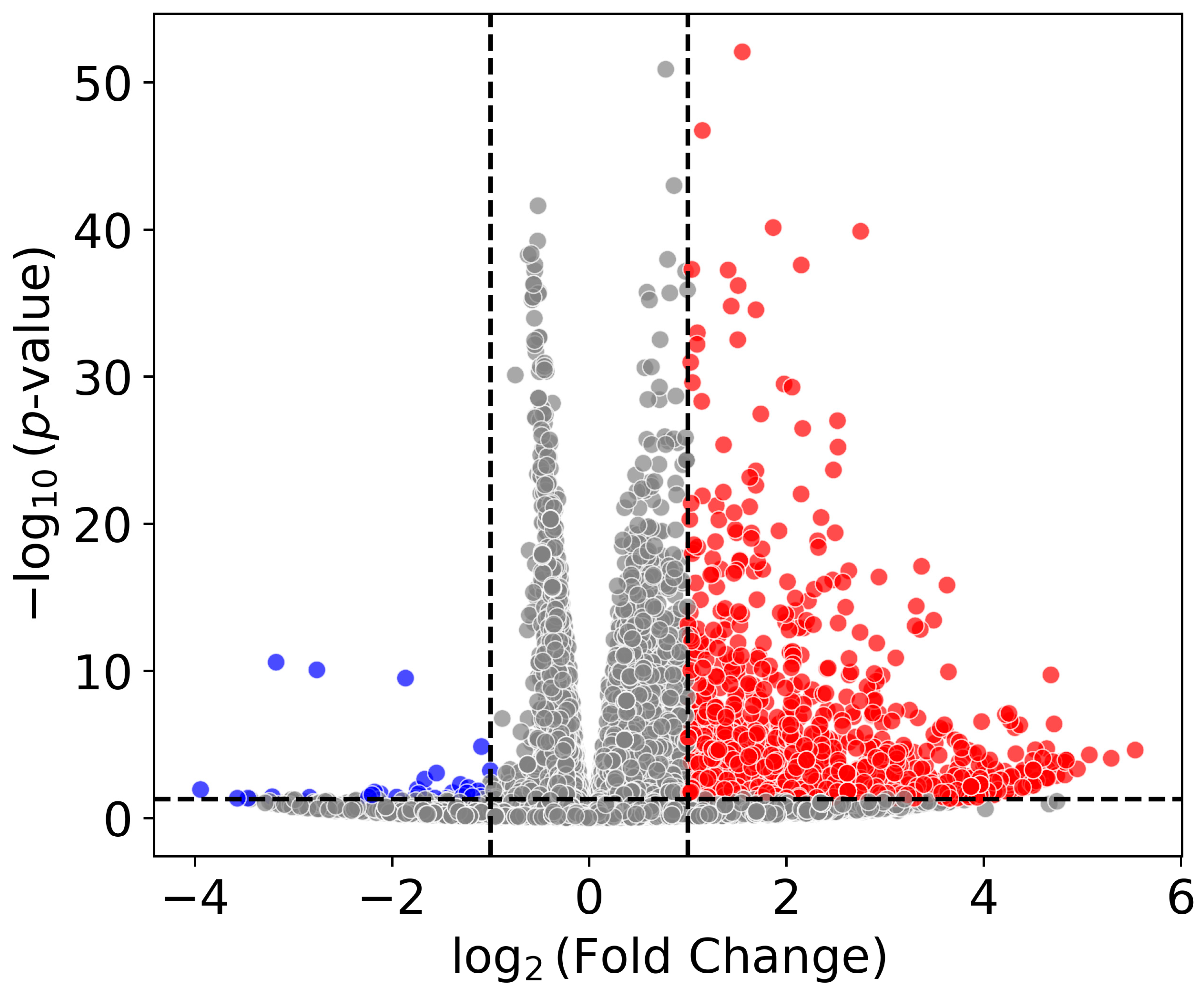

2.1.1. Differential Gene Expression

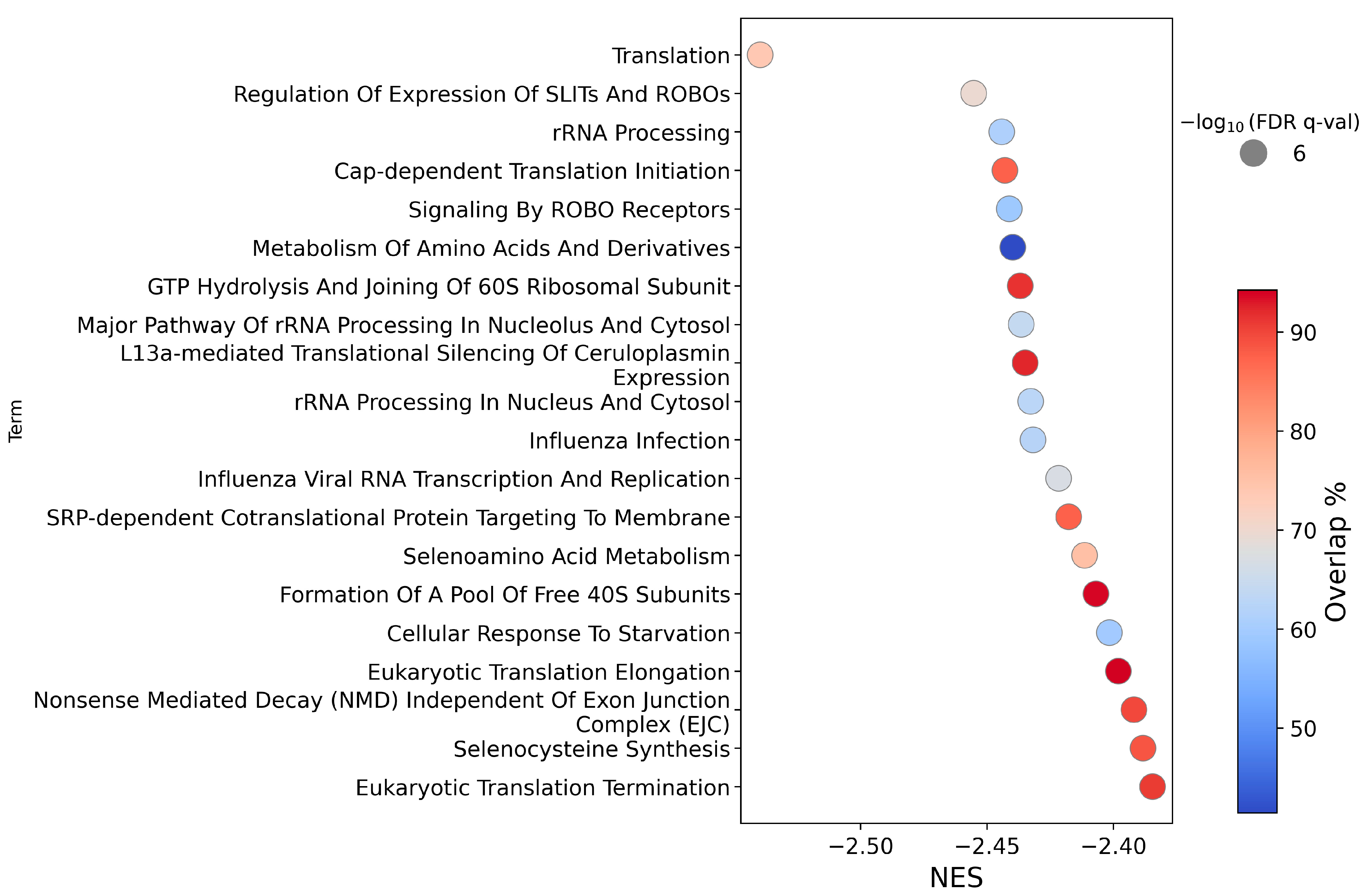

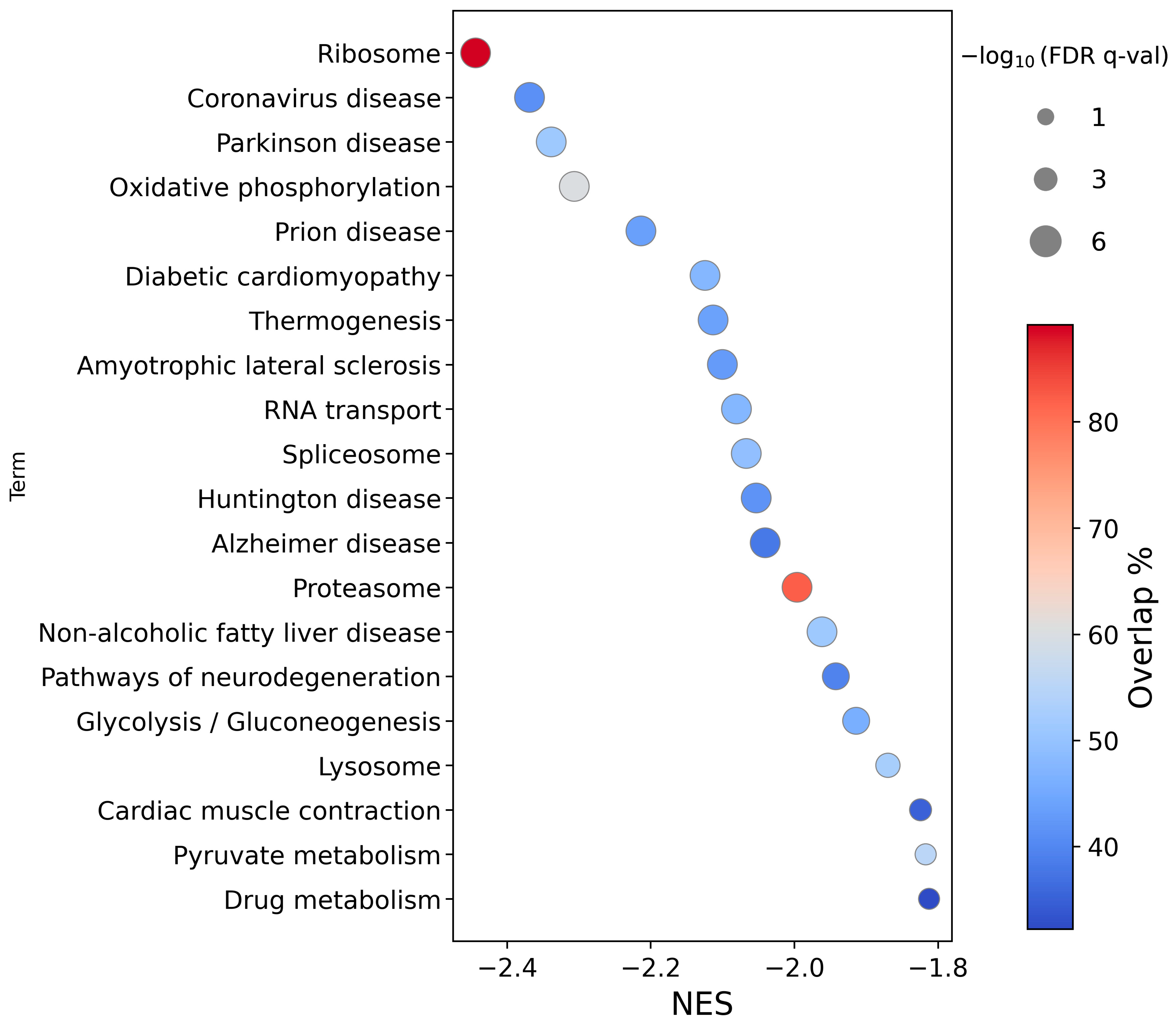

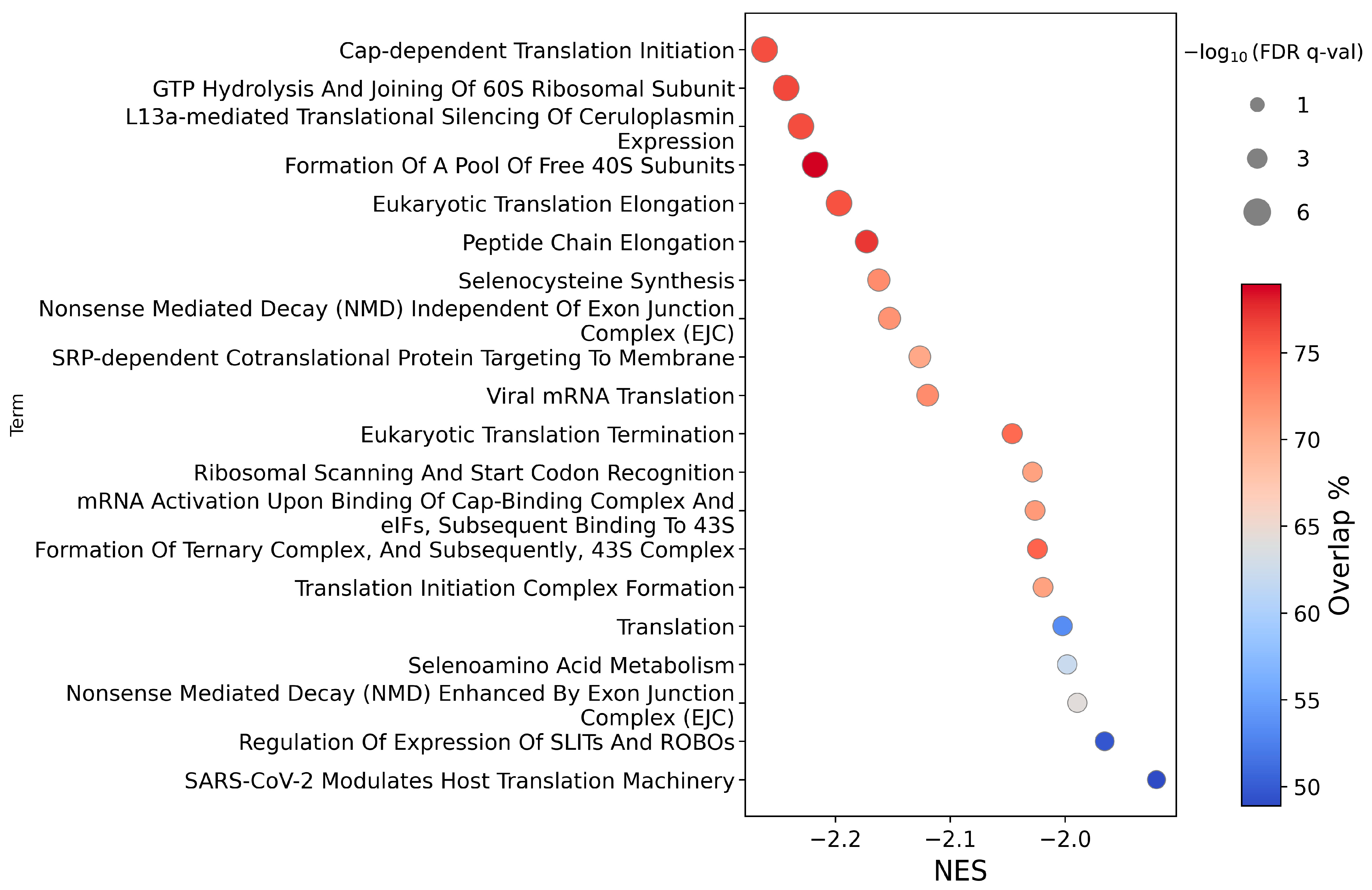

2.1.2. Pathway Analysis

2.2. CA3 HaloTag Experiments

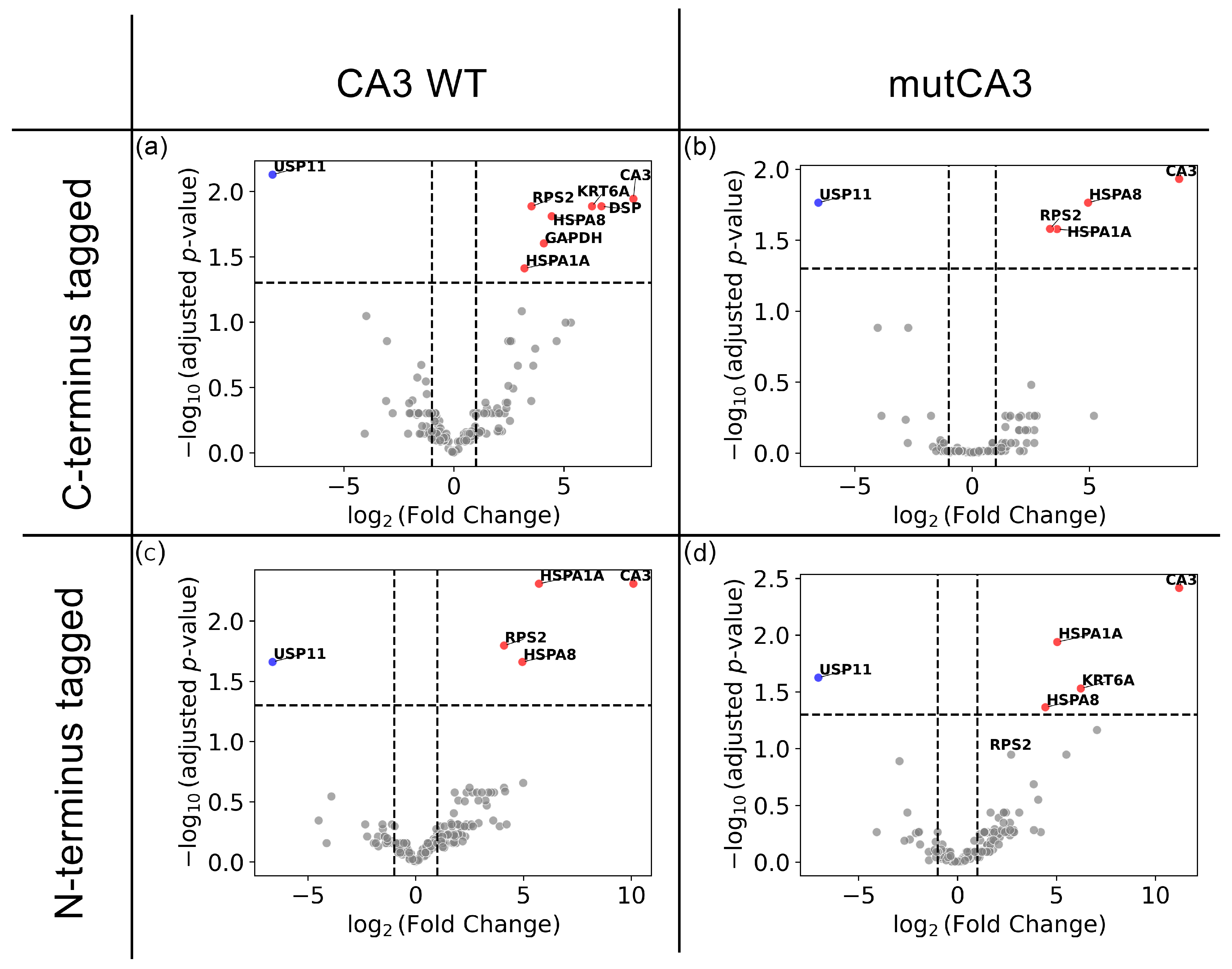

2.2.1. Protein Pull-Down Assays

2.2.2. Proteomic Alterations

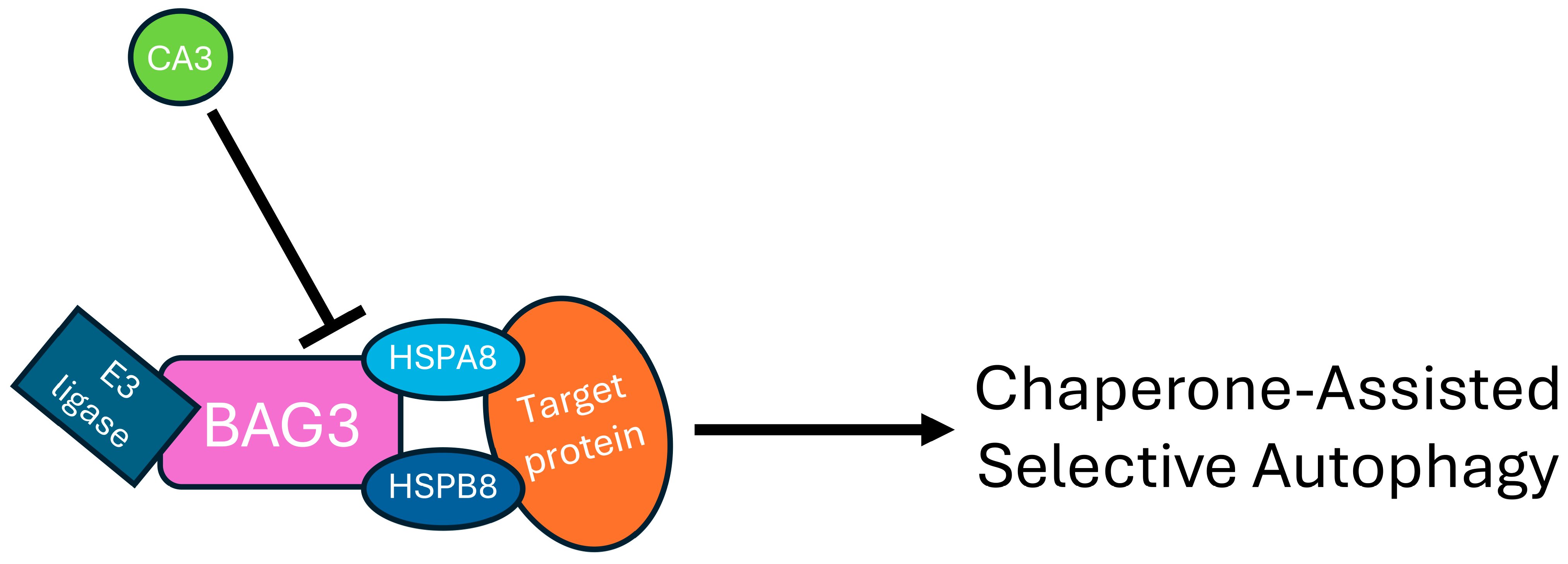

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plasmids Used for Transfection

4.2. Cell Culture and Protein Overexpression

4.3. RNA Sequencing Sample Preparation and Data Normalization

4.4. Differential Gene Expression Analysis

4.5. RNA Sequencing Pathway Analysis

4.6. Cell Transfection and HaloTag Pull-Down Protein Procedure

4.7. Proteomics Sample Preparation and Protein Identification

4.8. Label-Free Quantitative (LFQ) Proteomics Analyses and Data Visualization

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALS | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| APP | Amyloid precursor protein |

| BAG3 | Bcl2-Associated Anthanogene 3 |

| CA | Carbonic Anhydrase |

| CASA | Chaperone-assisted selective autophagy |

| CHRN | Cholinergic Receptor Nicotinic |

| CO2 | carbon dioxide |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| DGE | Differential Gene Expression |

| EMT | Epithelial–mesenchymal transition |

| FA | Formic acid |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| GPX | Glutathione Peroxidase |

| GSEA | Gene Set Enrichment Analysis |

| HSPA1A | Heat shock 70 kDa protein 1A |

| HSPA8 | Heat shock 70 kDa protein 8 |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| KRT6A | Keratin 6A |

| MS | Mass spectrometry |

| mTOR | mechanistic Target Of Rapamycin |

| NCBI | National Center for Biotechnology Information |

| NES | Normalized Enrichment Score |

| NF-kB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NPC | Nuclear Pore Complex |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PRKN | Parkin |

| RANBP2 | RAS-related nuclear protein binding protein 2 |

| ROBO1 | Roundabout guidance receptor 1 |

| RPS2 | Ribosomal protein S2 |

| SQLE | Squalene Epoxidase |

| SUMO | Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier |

| TFA | Trifluoroacetic acid |

| TrxR | Thioredoxin Reductase |

| USP11 | Ubiquitin Specific Protease 11 |

References

- Meldrum, N.U.; Roughton, F.J. Carbonic anhydrase. Its preparation and properties. J. Physiol. 1933, 80, 113–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinkman, R.; Margaria, R.; Roughton, F.J. The kinetics of the carbon dioxide-carbonic acid reaction. Philos. Trans. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 1933, 232, 65–97. [Google Scholar]

- Nishimori, I.; Innocenti, A.; Vullo, D.; Scozzafava, A.; Supuran, C.T. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Inhibition studies of the human secretory isoform VI with anions. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 1037–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimori, I.; Minakuchi, T.; Onishi, S.; Vullo, D.; Cecchi, A.; Scozzafava, A.; Supuran, C.T. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: Cloning, characterization, and inhibition studies of the cytosolic isozyme III with sulfonamides. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007, 15, 7229–7236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda, D.M.; Tu, C.; Fisher, S.Z.; An, H.; Yoshioka, C.; Govindasamy, L.; Laipis, P.J.; Agbandje-McKenna, M.; Silverman, D.N.; McKenna, R. Human carbonic anhydrase III: Structural and kinetic study of catalysis and proton transfer. Biochemistry 2005, 44, 10046–10053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, D.N.; Lindskog, S. The catalytic mechanism of carbonic anhydrase: Implications of a rate-limiting protolysis of water. Acc. Chem. Res. 1988, 21, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, R.S. Mammalian carbonic anhydrase isozymes: Evidence for a third locus. J. Exp. Zool. 1976, 197, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, A.-L.; Du, A.-L.; Ren, H.-M.; Du, A.-L.; Ren, H.-M.; Lu, C.-Z.; Tu, J.-L.; Xu, C.-F.; Sun, Y.-A. Carbonic anhydrase III is insufficient in muscles of myasthenia gravis patients. Autoimmunity 2009, 42, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, A.; Huang, S.; Zhao, X.; Feng, K.; Zhang, S.; Huang, J.; Miao, X.; Baggi, F.; Ostrom, R.S.; Zhang, Y. Suppression of CHRN endocytosis by carbonic anhydrase CAR3 in the pathogenesis of myasthenia gravis. Autophagy 2017, 13, 1981–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, Y.H.; Su, C.W.; Hsieh, Y.S.; Chen, P.N.; Lin, C.W.; Yang, S.F. Carbonic Anhydrase III Promotes Cell Migration and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cells 2020, 9, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Väänänen, H.K.; Takala, T.E.; Tolonen, U.; Vuori, J.; Myllylä, V.V. Muscle-specific carbonic anhydrase III is a more sensitive marker of muscle damage than creatine kinase in neuromuscular disorders. Arch. Neurol. 1988, 45, 1254–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, P.; Gargan, S.; Zweyer, M.; Sabir, H.; Swandulla, D.; Ohlendieck, K. Proteomic profiling of carbonic anhydrase CA3 in skeletal muscle. Expert Rev. Proteom. 2021, 18, 1073–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.-C.; Jung, C.-H.; Lii, C.-K.; Ashraf, S.S.; Hendrich, S.; Wolf, B.; Sies, H.; Thomas, J.A. Identification of an abundant S-thiolated rat liver protein as carbonic anhydrase III; characterization of S-thiolation and dethiolation reactions. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1991, 284, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engberg, P.; Millqvist, E.; Pohl, G.; Lindskog, S. Purification and some properties of carbonic anhydrase from bovine skeletal muscle. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1985, 241, 628–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monti, D.M.; De Simone, G.; Langella, E.; Supuran, C.T.; Di Fiore, A.; Monti, S.M. Insights into the role of reactive sulfhydryl groups of Carbonic Anhydrase III and VII during oxidative damage. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2017, 32, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Räisänen, S.; Lehenkari, P.; Tasanen, M.; Härkönen, P.; Väänänen, K. Carbonic anhydrase III protects cells from hydrogen peroxide induced apoptosis. Pathophysiology 1998, 1001, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silagi, E.S.; Batista, P.; Shapiro, I.M.; Risbud, M.V. Expression of Carbonic Anhydrase III, a Nucleus Pulposus Phenotypic Marker, is Hypoxia-responsive and Confers Protection from Oxidative Stress-induced Cell Death. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Uda, Y.; Dedic, C.; Azab, E.; Sun, N.; Hussein, A.I.; Petty, C.A.; Fulzele, K.; Mitterberger-Vogt, M.C.; Zwerschke, W. Carbonic anhydrase III protects osteocytes from oxidative stress. Faseb J. 2017, 32, 440–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Wong, C.C.; Zhou, Y.; Li, C.; Chen, H.; Ji, F.; Go, M.Y.Y.; Wang, F.; Su, H.; Wei, H.; et al. Squalene Epoxidase Induces Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Via Binding to Carbonic Anhydrase III and is a Therapeutic Target. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 2467–2482, Correction in Gastroenterology 2022, 163, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Poulsen, S.-A.; Di Trapani, G.; Tonissen, K.F. Exploring the Redox and pH Dimension of Carbonic Anhydrases in Cancer: A Focus on Carbonic Anhydrase 3. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2024, 41, 957–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Tang, S.; Hu, J.; Wu, Q.; Wei, Y.; Niu, M. Carbonic Anhydrase III Attenuates Hypoxia-Induced Apoptosis and Activates PI3K/Akt/mTOR Pathway in H9c2 Cardiomyocyte Cell Line. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2021, 21, 914–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, E.W.; Paik, S.; Brünner, N.; Sommers, C.L.; Zugmaier, G.; Clarke, R.; Shima, T.B.; Torri, J.; Donahue, S.; Lippman, M.E.; et al. Association of increased basement membrane invasiveness with absence of estrogen receptor and expression of vimentin in human breast cancer cell lines. J. Cell. Physiol. 1992, 150, 534–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.E. In vitro transformation of human epithelial cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 1986, 823, 161–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; He, D.L.; Ning, L.; Shen, S.L.; Li, L.; Li, X. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha induces the epithelial-mesenchymal transition of human prostatecancer cells. Chin. Med. J. 2006, 119, 713–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G.K.; Shi, W. featureCounts: An efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 2013, 30, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Liu, X.; Peltz, G. GSEApy: A comprehensive package for performing gene set enrichment analysis in Python. Bioinformatics 2022, 39, btac757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milacic, M.; Beavers, D.; Conley, P.; Gong, C.; Gillespie, M.; Griss, J.; Haw, R.; Jassal, B.; Matthews, L.; May, B.; et al. The Reactome Pathway Knowledgebase 2024. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 52, D672–D678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Sternicki, L.M.; Hilko, D.H.; Jarrott, R.J.; Di Trapani, G.; Tonissen, K.F.; Poulsen, S.-A. Investigating Active Site Binding of Ligands to High and Low Activity Carbonic Anhydrase Enzymes Using Native Mass Spectrometry. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 15862–15872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodge, K.; Have, S.T.; Hutton, L.; Lamond, A.I. Cleaning up the masses: Exclusion lists to reduce contamination with HPLC-MS/MS. J. Proteom. 2013, 88, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Matunis, M.J.; Kraemer, D.; Blobel, G.; Coutavas, E. Nup358, a cytoplasmically exposed nucleoporin with peptide repeats, Ran-GTP binding sites, zinc fingers, a cyclophilin A homologous domain, and a leucine-rich region. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 14209–14213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, P.A. Nucleocytoplasmic transport at the crossroads of proteostasis, neurodegeneration and neuroprotection. Febs Lett. 2023, 597, 2567–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steffan, J.S.; Agrawal, N.; Pallos, J.; Rockabrand, E.; Trotman, L.C.; Slepko, N.; Illes, K.; Lukacsovich, T.; Zhu, Y.Z.; Cattaneo, E.; et al. SUMO modification of Huntingtin and Huntington’s disease pathology. Science 2004, 304, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, S.; Quon, D.; Liu, Y.W.; Cordell, B. Positive and negative regulation of APP amyloidogenesis by sumoylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorval, V.; Fraser, P.E. Small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) modification of natively unfolded proteins tau and alpha-synuclein. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 9919–9924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desgraupes, S.; Etienne, L.; Arhel, N.J. RANBP2 evolution and human disease. Febs Lett. 2023, 597, 2519–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asuni, A.A.; Gray, B.; Bailey, J.; Skipp, P.; Perry, V.H.; O’Connor, V. Analysis of the hippocampal proteome in ME7 prion disease reveals a predominant astrocytic signature and highlights the brain-restricted production of clusterin in chronic neurodegeneration. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 4532–4545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.I.; Yoon, D.; Yu, M.; Peachey, N.S.; Ferreira, P.A. Microglial activation in an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-like model caused by Ranbp2 loss and nucleocytoplasmic transport impairment in retinal ganglion neurons. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 3407–3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, J.W.; Min, D.S.; Rhim, H.; Kim, J.; Paik, S.R.; Chung, K.C. Parkin ubiquitinates and promotes the degradation of RanBP2. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 3595–3603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Xiao, M.; Zhu, Y.; Gong, R.; Liu, J.; Zeng, Q.; Xu, C.; Chen, X.; Wang, F.; et al. RANBP2 Activates O-GlcNAcylation through Inducing CEBPα-Dependent OGA Downregulation to Promote Hepatocellular Carcinoma Malignant Phenotypes. Cancers 2021, 13, 3475, Correction in Cancers 2024, 16, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.; Tan, S.H.; Karpova, T.S.; McNally, J.G.; Dasso, M. SUMO-1 targets RanGAP1 to kinetochores and mitotic spindles. J. Cell. Biol. 2002, 156, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashizume, C.; Kobayashi, A.; Wong, R.W. Down-modulation of nucleoporin RanBP2/Nup358 impaired chromosomal alignment and induced mitotic catastrophe. Cell. Death Dis. 2013, 4, e854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, Y.; Shin, S.J.; Kumar, V.; Won, J.; Kim, S.; Moon, M. Dual modulation of amyloid beta and tau aggregation and dissociation in Alzheimer’s disease: A comprehensive review of the characteristics and therapeutic strategies. Transl. Neurodegener. 2025, 14, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karvandi, M.S.; Sheikhzadeh Hesari, F.; Aref, A.R.; Mahdavi, M. The neuroprotective effects of targeting key factors of neuronal cell death in neurodegenerative diseases: The role of ER stress, oxidative stress, and neuroinflammation. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1105247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsi, A.; Bombieri, C.; Valenti, M.T.; Romanelli, M.G. Tau Isoforms: Gaining Insight into MAPT Alternative Splicing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storkebaum, E.; Rosenblum, K.; Sonenberg, N. Messenger RNA Translation Defects in Neurodegenerative Diseases. New Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 1015–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, V.; Dick, N.; Tawo, R.; Dreiseidler, M.; Wenzel, D.; Hesse, M.; Fürst, D.O.; Saftig, P.; Saint, R.; Fleischmann, B.K.; et al. Chaperone-assisted selective autophagy is essential for muscle maintenance. Curr. Biol. 2010, 20, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamerdinger, M.; Kaya, A.M.; Wolfrum, U.; Clement, A.M.; Behl, C. BAG3 mediates chaperone-based aggresome-targeting and selective autophagy of misfolded proteins. Embo Rep. 2011, 12, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedesco, B.; Vendredy, L.; Timmerman, V.; Poletti, A. The chaperone-assisted selective autophagy complex dynamics and dysfunctions. Autophagy 2023, 19, 1619–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selcen, D.; Muntoni, F.; Burton, B.K.; Pegoraro, E.; Sewry, C.; Bite, A.V.; Engel, A.G. Mutation in BAG3 causes severe dominant childhood muscular dystrophy. Ann. Neurol. 2009, 65, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homma, S.; Iwasaki, M.; Shelton, G.D.; Engvall, E.; Reed, J.C.; Takayama, S. BAG3 deficiency results in fulminant myopathy and early lethality. Am. J. Pathol. 2006, 169, 761–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Sun, K.; Zhang, X.; Tang, Y.; Xu, D. Advances in the role and mechanism of BAG3 in dilated cardiomyopathy. Heart Fail. Rev. 2021, 26, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulbricht, A.; Eppler, F.J.; Tapia, V.E.; van der Ven, P.F.; Hampe, N.; Hersch, N.; Vakeel, P.; Stadel, D.; Haas, A.; Saftig, P.; et al. Cellular mechanotransduction relies on tension-induced and chaperone-assisted autophagy. Curr. Biol. 2013, 23, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterman, P.O.; Askmark, H.; Wistrand, P.J. Serum carbonic anhydrase III in neuromuscular disorders and in healthy persons after a long-distance run. J. Neurol. Sci. 1985, 70, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhu, S.; Li, J.; Jiang, T.; Feng, L.; Pei, J.; Wang, G.; Ouyang, L.; Liu, B. Targeting autophagy using small-molecule compounds to improve potential therapy of Parkinson’s disease. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2021, 11, 3015–3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Zhang, X.D. Role of chaperone-mediated autophagy in degrading Huntington’s disease-associated huntingtin protein. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2014, 46, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boland, B.; Yu, W.H.; Corti, O.; Mollereau, B.; Henriques, A.; Bezard, E.; Pastores, G.M.; Rubinsztein, D.C.; Nixon, R.A.; Duchen, M.R.; et al. Promoting the clearance of neurotoxic proteins in neurodegenerative disorders of ageing. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018, 17, 660–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Sun, Y.; Cen, X.; Shan, B.; Zhao, Q.; Xie, T.; Wang, Z.; Hou, T.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, M.; et al. Metformin activates chaperone-mediated autophagy and improves disease pathologies in an Alzheimer disease mouse model. Protein Cell 2021, 12, 769–787, Correction in Protein Cell 2022, 13, 227-229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiSalvo, S.; Derdowski, A.; Pezza, J.A.; Serio, T.R. Dominant prion mutants induce curing through pathways that promote chaperone-mediated disaggregation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2011, 18, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Pei, Q.; Ni, W.; Fu, X.; Zhang, W.; Song, C.; Peng, Y.; Guo, Q.; Dong, J.; Yao, M. HSPA1A Protects Cells from Thermal Stress by Impeding ESCRT-0-Mediated Autophagic Flux in Epidermal Thermoresistance. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2021, 141, 48–58.e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirtori, R.; Riva, C.; Ferrarese, C.; Sala, G. HSPA8 knock-down induces the accumulation of neurodegenerative disorder-associated proteins. Neurosci. Lett. 2020, 736, 135272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Li, T.; Ma, Z.; Zhou, C.; Wang, X.; Li, J. HSPA1A, HSPA2, and HSPA8 Are Potential Molecular Biomarkers for Prognosis among HSP70 Family in Alzheimer’s Disease. Dis. Markers 2022, 2022, 9480398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M.; Fujikawa, R.; Sekiguchi, T.; Hernandez, J.; Johnson, O.T.; Tanaka, D.; Kumafuji, K.; Serikawa, T.; Hoang Trung, H.; Hattori, K.; et al. A missense mutation in the Hspa8 gene encoding heat shock cognate protein 70 causes neuroaxonal dystrophy in rats. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1263724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Leal, A.C.; Salas-Pacheco, S.M.; Hernández-Cosaín, E.I.; Vélez-Vélez, L.M.; Antuna-Salcido, E.I.; Castellanos-Juárez, F.X.; Méndez-Hernández, E.M.; Llave-León, O.; Quiñones-Canales, G.; Arias-Carrión, O.; et al. Differential expression of PSMC4, SKP1, and HSPA8 in Parkinson’s disease: Insights from a Mexican mestizo population. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2023, 16, 1298560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, M.; Owczarek, A.; Suchanek-Raif, R.; Kucia, K.; Kowalski, J. An association study of the HSPA8 gene polymorphisms with schizophrenia in a Polish population. Cell Stress Chaperones 2022, 27, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, T.; Her, Y.R.; Kim, J.K.; Jha, N.N.; Monani, U.R. A variant of the Hspa8 synaptic chaperone modifies disease in a SOD1(G86R) mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Exp. Neurol. 2025, 383, 115024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonda, Y.; Namba, T.; Hanashima, C. Beyond Axon Guidance: Roles of Slit-Robo Signaling in Neocortical Formation. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 607415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhosle, V.K.; Tan, J.M.; Li, T.; Hua, R.; Kwon, H.; Li, Z.; Patel, S.; Tessier-Lavigne, M.; Robinson, L.A.; Kim, P.K.; et al. SLIT2/ROBO1 signaling suppresses mTORC1 for organelle control and bacterial killing. Life Sci. Alliance 2023, 6, e202301964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagare, A.; Balaur, I.; Rougny, A.; Saraiva, C.; Gobin, M.; Monzel, A.S.; Ghosh, S.; Satagopam, V.P.; Schwamborn, J.C. Deciphering shared molecular dysregulation across Parkinson’s disease variants using a multi-modal network-based data integration and analysis. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2025, 11, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, H.; Mutlu, S.A.; Bowser, D.A.; Moore, M.J.; Wang, M.C.; Zheng, H. The Amyloid Precursor Protein Is a Conserved Receptor for Slit to Mediate Axon Guidance. eNeuro 2017, 4, e0185-17.2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anitha, A.; Nakamura, K.; Yamada, K.; Suda, S.; Thanseem, I.; Tsujii, M.; Iwayama, Y.; Hattori, E.; Toyota, T.; Miyachi, T.; et al. Genetic analyses of roundabout (ROBO) axon guidance receptors in autism. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2008, 147b, 1019–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, P.; Wu, T.; Zhu, S.; Deng, L.; Cui, G. Axon guidance pathway genes are associated with schizophrenia risk. Exp. Ther. Med. 2018, 16, 4519–4526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannula-Jouppi, K.; Kaminen-Ahola, N.; Taipale, M.; Eklund, R.; Nopola-Hemmi, J.; Kääriäinen, H.; Kere, J. The axon guidance receptor gene ROBO1 is a candidate gene for developmental dyslexia. PLoS Genet. 2005, 1, e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinero-Pinto, E.; Pérez-Cabezas, V.; Tous-Rivera, C.; Sánchez-González, J.M.; Ruiz-Molinero, C.; Jiménez-Rejano, J.J.; Benítez-Lugo, M.L.; Sánchez-González, M.C. Mutation in ROBO3 Gene in Patients with Horizontal Gaze Palsy with Progressive Scoliosis Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calloni, S.F.; Cohen, J.S.; Meoded, A.; Juusola, J.; Triulzi, F.M.; Huisman, T.; Poretti, A.; Fatemi, A. Compound Heterozygous Variants in ROBO1 Cause a Neurodevelopmental Disorder With Absence of Transverse Pontine Fibers and Thinning of the Anterior Commissure and Corpus Callosum. Pediatr. Neurol. 2017, 70, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engle, E.C. The Genetic Basis of Complex Strabismus. Pediatr. Res. 2006, 59, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viding, E.; Hanscombe, K.B.; Curtis, C.J.; Davis, O.S.; Meaburn, E.L.; Plomin, R. In search of genes associated with risk for psychopathic tendencies in children: A two-stage genome-wide association study of pooled DNA. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2010, 51, 780–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.C.; Ho, S.C.; Chen, Y.Y.; Khoo, K.H.; Hsu, P.H.; Yen, H.C. SELENOPROTEINS. CRL2 aids elimination of truncated selenoproteins produced by failed UGA/Sec decoding. Science 2015, 349, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miar, A.; Arnaiz, E.; Bridges, E.; Beedie, S.; Cribbs, A.P.; Downes, D.J.; Beagrie, R.A.; Rehwinkel, J.; Harris, A.L. Hypoxia Induces Transcriptional and Translational Downregulation of the Type I IFN Pathway in Multiple Cancer Cell Types. Cancer Res. 2020, 80, 5245–5256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraldo, L.H.; Xu, Y.; Mouthon, G.; Furtado, J.; Leser, F.S.; Blazer, L.L.; Adams, J.J.; Zhang, S.; Zheng, L.; Song, E.; et al. Monoclonal antibodies that block Roundabout 1 and 2 signaling target pathological ocular neovascularization through myeloid cells. Sci. Transl. Med. 2024, 16, eadn8388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cailleau, R.; Young, R.; Olivé, M.; Reeves, W.J., Jr. Breast Tumor Cell Lines From Pleural Effusions2. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1974, 53, 661–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobin, A.; Davis, C.A.; Schlesinger, F.; Drenkow, J.; Zaleski, C.; Jha, S.; Batut, P.; Chaisson, M.; Gingeras, T.R. STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, G.X.; Deng, Y.; Yu, F.; Valipour Kahrood, H.; Steele, J.R.; Schittenhelm, R.B.; Nesvizhskii, A.I. Analysis and Visualization of Quantitative Proteomics Data Using FragPipe-Analyst. J. Proteome Res. 2024, 23, 4303–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Riverol, Y.; Bandla, C.; Kundu, D.J.; Kamatchinathan, S.; Bai, J.; Hewapathirana, S.; John, N.S.; Prakash, A.; Walzer, M.; Wang, S.; et al. The PRIDE database at 20 years: 2025 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D543–D553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, Y.; Anugraham, M.; Blick, T.; Kulasinghe, A.; Sternicki, L.M.; Di Trapani, G.; Poulsen, S.-A.; Kolarich, D.; Tonissen, K.F. Carbonic Anhydrase 3 Overexpression Modulates Signalling Pathways Associated with Cellular Stress Resilience and Proteostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12064. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412064

Yu Y, Anugraham M, Blick T, Kulasinghe A, Sternicki LM, Di Trapani G, Poulsen S-A, Kolarich D, Tonissen KF. Carbonic Anhydrase 3 Overexpression Modulates Signalling Pathways Associated with Cellular Stress Resilience and Proteostasis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12064. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412064

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Yezhou, Merrina Anugraham, Tony Blick, Arutha Kulasinghe, Louise M. Sternicki, Giovanna Di Trapani, Sally-Ann Poulsen, Daniel Kolarich, and Kathryn F. Tonissen. 2025. "Carbonic Anhydrase 3 Overexpression Modulates Signalling Pathways Associated with Cellular Stress Resilience and Proteostasis" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12064. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412064

APA StyleYu, Y., Anugraham, M., Blick, T., Kulasinghe, A., Sternicki, L. M., Di Trapani, G., Poulsen, S.-A., Kolarich, D., & Tonissen, K. F. (2025). Carbonic Anhydrase 3 Overexpression Modulates Signalling Pathways Associated with Cellular Stress Resilience and Proteostasis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12064. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412064