Abstract

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is a gasotransmitter that plays a crucial role in regulating pathological processes following injury to the central and peripheral nervous systems. This review systematizes current data on various classes of H2S donors and inhibitors of its biosynthesis in neurotrauma and related experimental models. Inorganic donors (e.g., NaHS, Na2S, and STS) rapidly suppress oxidative stress and inflammation, supporting the recovery of synaptic plasticity and cognitive function. Organic donors (e.g., GYY4137, ACS67, ACS84, SPRC, ADT-OH and its derivatives, S-memantine, and MTC) provide sustained H2S release, stabilize the blood–brain barrier, and exhibit antiapoptotic activity. Natural donors (e.g., DADS, DATS, and SAMe) demonstrate high biocompatibility, inhibit pyroptosis, and enhance antioxidant defense mechanisms. Hybrid systems—including nanoparticles and hydrogels—enable targeted delivery and prolonged action, thereby stimulating regeneration and angiogenesis. Thiol-activated donors (e.g., COS/H2S and AlaCOS) allow controlled H2S release, offering broad opportunities for precise modulation of its concentration within target tissues. Inhibitors (e.g., AOAA, PAG, oxamic hydrazide 1, L-aspartic acid, benserazide, and NSC4056) of H2S biosynthesis underscore the physiological importance of this gasotransmitter, as their administration enhances neuroinflammation and diminishes neuroprotection. The analysis reveals a general pattern: all classes of H2S donors effectively modulate key pathological mechanisms, differing in their rate, duration, and specificity of action. These findings highlight the therapeutic promise of H2S-based pharmacological agents in clinical neurotraumatology, while emphasizing the need for further research to optimize delivery systems, enhance efficacy, and minimize adverse effects.

Keywords:

hydrogen sulfide; hydrogen sulfide donors; traumatic brain injury; spinal cord injury; peripheral nervous system injury; neuron; glial cells; neuroprotection; H2S-releasing hybrids; blood–brain barrier; oxidative stress; neuroinflammation; cerebral ischemia; axonal regeneration; microglia polarization; brain edema; mitochondria-targeted donors; slow-release donors; neuropathic pain 1. Introduction

Neurotrauma, including traumatic brain injury (TBI) and spinal cord injury (SCI), represents one of the leading causes of disability and mortality worldwide, posing a significant threat to global healthcare systems [1,2]. In addition, injuries to the peripheral nervous system can also lead to severe and long-term health complications [3]. These conditions are characterized by the activation of a complex signaling network that induces oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, reactive gliosis, disruption of the structural and functional integrity of the blood–brain barrier (BBB), and degenerative alterations in neurons and surrounding glial cells, ultimately resulting in cell death [4].

Despite considerable progress in neurotraumatology, including the development of applied treatment strategies and advances in understanding molecular mechanisms, current therapeutic approaches remain limited. They are largely focused on symptomatic management and rehabilitation, while effective interventions aimed at suppressing secondary injury and stimulating neural tissue regeneration are lacking. This gap arises from the absence of a unified molecular–cellular concept of neurotrauma pathogenesis and the scarcity of clinically effective neuroprotective agents [5].

In this context, the study of endogenous gaseous signaling molecules such as hydrogen sulfide (H2S) has become particularly relevant. Extensive preclinical evidence demonstrates the fundamental role of H2S in modulating key signaling mechanisms that mediate neuroprotection through activation of antioxidant systems, stabilization of the BBB, attenuation of neuroinflammation, and suppression of cell death [6,7,8]. As a potent reducing agent, H2S directly scavenges reactive oxygen species (ROS) and inhibits free-radical reactions, thereby stabilizing cell membranes and maintaining neuronal energy homeostasis. H2S reaches its highest concentrations in the brain due to the activity of key enzymes—cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) and cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE)—which catalyze its synthesis. The enzyme 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (3-MST) also contributes to H2S production, although its role in maintaining H2S levels in nervous tissue is less pronounced [9]. Intracellular H2S homeostasis constitutes a dynamic regulatory system that responds sensitively to internal and external stimuli. Its biological actions are dose-dependent and predominantly neuroprotective, supporting neuronal survival and stabilizing cellular processes. However, excessive H2S production can have deleterious consequences, contributing to mechanisms of secondary injury [10,11,12].

Thus, H2S-associated agents hold significant potential for integration into modern therapeutic strategies for neurotrauma, offering prospects for effective stabilization and regeneration of damaged neurons and glial cells. Nevertheless, despite an extensive “scientific library” of experimental data, translation into clinical practice remains challenging. The absence of a unified concept of H2S-dependent neuroprotection—caused by the heterogeneity of experimental models, research protocols, doses, and modulators—has led to a fragmented understanding of this gasotransmitter’s role under conditions of neuronal stress [13]. To date, most studies have focused on isolated effects of individual H2S donors or inhibitors, without comprehensive analysis of their structural–functional features or interactions within the intricate network of signaling pathways activated during neurotrauma. Moreover, unresolved questions regarding biocompatibility, targeted delivery, and minimization of adverse effects continue to fuel scientific debate over the most effective and safe H2S-based neuroprotective agent, thereby delaying the clinical translation of preclinical findings [14,15,16].

In our previous review studies, we systematically analyzed the role of gasotransmitters, including H2S, in the pathogenesis of various neurological disorders such as neurodegenerative diseases, as well as injuries to the central and peripheral nervous systems [10,17,18]. Furthermore, we have accumulated substantial experimental experience investigating the effects of several H2S donors on the regulation of cell death mechanisms following TBI [19,20,21,22]. These data provided the foundation for the present review, which is based on a comprehensive analysis and conceptual synthesis of existing information on H2S donors and inhibitors.

The novelty of this review lies in the systematic qualitative analysis of various classes of H2S modulators—ranging from inorganic and organic donors to hybrid nanosystems and biosynthesis inhibitors—with a particular emphasis on identifying common patterns in their mechanisms of action, including protein persulfidation, activation of antioxidant systems, receptor interactions, modulation of neuroinflammation, and regenerative processes. This work aims to compile and systematize the biological effects of H2S-associated compounds in diverse experimental models of nervous tissue injury, including TBI, SCI, peripheral nerve damage, stroke, ischemia/reperfusion (I/R), and neurodegenerative diseases. Such an integrative approach enables the identification of shared molecular and cellular mechanisms of H2S action depending on the type of donor and supports the development of a unified conceptual model of H2S-dependent signaling in neurotrauma, thereby facilitating the selection of optimal delivery strategies.

The objective of this review is to conduct a comprehensive analysis of key patterns in the biological effects of H2S modulators under neurotraumatic conditions, with a focus on their structural characteristics, mechanisms of action, and therapeutic potential. We will examine inorganic, organic, natural, and hybrid H2S donors, as well as inhibitors of its biosynthesis, emphasizing differences in release kinetics, duration of action, cellular and molecular effects, biocompatibility, and targeted activity toward injured neural tissue.

2. Methods

This systematic review was conducted in strict accordance with the PRISMA-ScR guidelines [23], ensuring a structured and transparent analytical approach. A comprehensive literature search was performed using major international databases, including PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. The scoping review includes 192 scientific sources, ≈70% of which were published between 2022 and 2025. Notably, approximately ≈70% of the studies cited in the “Results” section were published during this same period, highlighting both the high relevance and rapid expansion of research on the role of H2S in neuroprotection following traumatic injuries to the central and peripheral nervous systems. This further underscores the need for systematic conceptualization of these data, which was first accomplished in the present work.

Although the literature search prioritized recent publications (2022–2025), studies published from 2011 onward were also included to ensure comprehensive coverage and adequate contextual depth. This approach enabled the integration of key early investigations with the latest findings, providing a balanced representation of the evolution of scientific knowledge regarding H2S-dependent neuroprotective mechanisms. Such a strategy is essential for developing a unified molecular–cellular framework that explains the roles of various H2S donors and inhibitors of its biosynthetic enzymes in the pathogenesis of neurotrauma.

2.1. Search Strategy and Selection of Publications

The literature search employed keywords directly related to the topic of this review: “hydrogen sulfide”, “hydrogen sulfide donors”, “neurotrauma”, “traumatic brain injury”, “spinal cord injury”, “peripheral nerve injury”, “neuroprotection”, and “H2S-associated compounds”. These terms were combined using Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT) to construct targeted queries that maximized relevance to the research objectives. Typical search strings included combinations such as “hydrogen sulfide AND neurotrauma” and “H2S donors AND spinal cord injury” (Supplementary Materials Table S1), enabling the identification of studies addressing both the fundamental and applied aspects of H2S in neurotraumatology.

The selection process was conducted in several stages. Initially, titles and abstracts were screened for relevance, followed by full-text analysis of eligible studies. Each publication was evaluated for methodological rigor, scientific validity, relevance, and consistency of results with the objectives of this review.

Inclusion criteria:

- Studies reporting the biological effects of H2S donors in neurotrauma models or related experimental paradigms.

- Publications providing mechanistic or interdisciplinary insights linking H2S to molecular pathways of neuroprotection.

- Original research articles or review papers aligned with the thematic scope of this study.

Exclusion criteria:

- Publications with significant methodological limitations (e.g., absence of control groups, inadequate statistical analysis, or poor reproducibility).

- Non-peer-reviewed materials.

- Insufficient informativeness or weak relevance to the subject of the review.

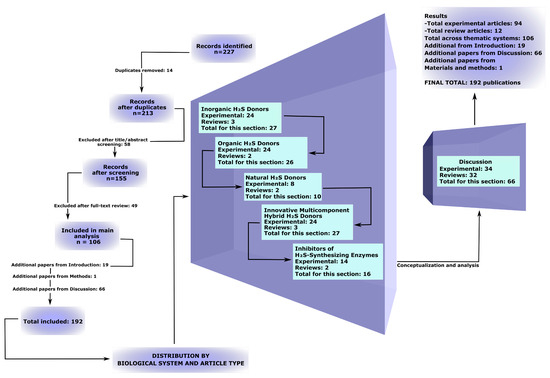

The database search across PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus initially identified 227 publications. After removing 14 duplicates, 213 records remained. During the title and abstract screening, 58 studies were excluded, followed by an additional 49 exclusions after full-text assessment. Ultimately, 106 scientific articles were included in the main qualitative analysis. In addition, 19 studies were included in the Introduction but were not used in the subsequent main results sections, and 1 source was included in the Materials and Methods (PRISMA-ScR guideline). Furthermore, 66 additional publications were incorporated into the Discussion to support interpretation of the qualitative analysis (Supplementary Materials Table S2). The detailed selection process is presented in the extended PRISMA-ScR flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Expanded PRISMA-ScR flowchart illustrating the process of study identification, screening, eligibility assessment, and inclusion in the review, with details by publication type in the relevant sections.

2.2. Quality Assessment and Decision-Making

Decisions on inclusion of studies were made by the authors independently based on a comprehensive assessment of their quality, relevance, and information content. Standardized quality assessment criteria were applied, including evaluation of methodological rigor, clarity of objectives and conclusions, and the reliability of presented data. This approach ensured consistency, transparency, and scientific validity throughout the analytical process.

3. Results

3.1. Inorganic H2S Donors

Inorganic H2S salts are the simplest and most widely used sources of exogenous H2S in experimental models of nervous system injury. They allow rapid simulation of H2S pharmacodynamics to study its biological effectors and molecular mechanisms of interaction with various extracellular and intracellular targets. The rapid release of H2S provides pronounced neuroprotection in ischemic stroke, TBI, and SCI by limiting the wave of secondary damage mediated through oxidative stress, apoptosis, and inflammation. However, the short-lived concentration peak that determines their transient action imposes serious limitations on their translation into clinical practice and stimulates the development of novel donors with controlled H2S release [24,25].

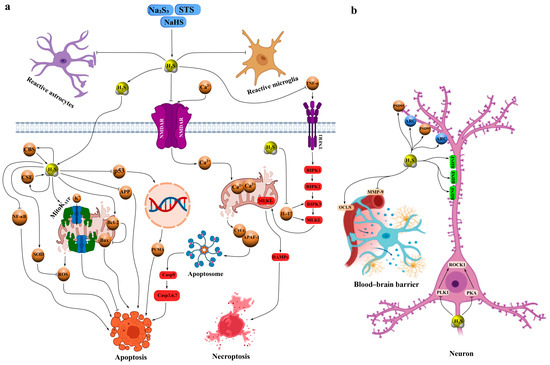

Sodium hydrosulfide (NaHS) is a classical fast-releasing donor of H2S that exhibits a broad spectrum of neuroprotective effects in various models of neurotrauma. For example, in TBI, administration of NaHS increased brain H2S levels, inhibited oxidative stress, and reduced the expression of injury biomarkers. These effects were accompanied by elevated levels of synaptic proteins, enhanced dendritic branching and spine density, and significant improvements in cognitive and motor performance, including reduced deficits in the Barnes maze and novel object recognition tests. The underlying mechanisms are believed to involve H2S-dependent modulation of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor activity, glutamate and Ca2+ homeostasis, and regulation of microtubule-associated proteins and calcium/calmodulin-stimulated protein kinase II (CaMKII) (Figure 2a, Table 1) [26].

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the neuroprotective mechanisms of action of H2S donors based on fast-releasing donors NaHS, Na2S, and STS in models of neurotrauma, such as TBI, I/R, and peripheral nerve injuries. (a) Antiapoptotic, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant H2S-dependent neuroprotective effects. The donors Na2S, STS, and NaHS rapidly release H2S, which inhibits NMDAR, reducing Ca2+ influx into neurons and suppressing the activation of reactive astrocytes and microglia. H2S activates H2S-synthesizing enzymes—CBS and CSE—enhancing endogenous H2S production. Additionally, H2S inhibits the transcription factors NF-κB and p53, the latter of which activates proapoptotic genes such as PUMA, suppresses the expression of APP, increases levels of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2, and activates MitoKATP, contributing to antioxidant defense. H2S also inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-17 and TNF-α; TNF-α activates TNFR1, triggering a necroptosis cascade via RIPK1, RIPK2, RIPK3, and MLKL, leading to the release of DAMPs. Excessive Ca2+ induces the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria, its binding to APAF-1, and activation of the apoptosome, enhancing apoptosis. (b) H2S-dependent effects on synaptic plasticity and BBB stabilization. H2S upregulates the expression of synaptic proteins PSD-95, ARC, and BDNF, promoting improved dendritic branching, spine density, and restoration of cognitive functions. It inhibits the phosphorylation and activation of ROCK2 by suppressing PLK1 and PKA, reducing the expression of LDH, NSE, and intracellular Ca2+. Additionally, H2S stabilizes the BBB by inhibiting MMP-9 and enhancing the stability of OCLN, reducing brain edema, barrier permeability, and lesion volume in TBI and I/R models. Arrows with pointed ends indicate activation, while blunt ends indicate inhibition.

Similarly, NaHS injections increased endogenous H2S levels, suppressing neuroinflammation and oxidative stress induced by TBI while upregulating brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein (ARC), and postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD-95)—proteins essential for synaptic plasticity and cognitive recovery (Figure 2b) [27]. In a controlled cortical impact model, NaHS demonstrated pronounced neuroprotective effects by reducing brain edema, BBB permeability, and lesion volume through activation of mitochondrial ATP-sensitive K+ channels (mitoK_ATP), enhancement of antioxidant defense, and inhibition of free radical generation (Figure 2a, Table 1) [28].

Intrathecal administration of NaHS prevented dopaminergic neuronal loss in the midbrain following chronic constriction injury of the sciatic nerve, likely via inhibition of IL-17-induced necroptosis and suppression of mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein (MLKL) expression, tyrosine hydroxylase activity, and neuronal firing frequency [29]. In peripheral nerve injury models, NaHS reduced glutamate levels in the spinal cord and cortical neuronal firing frequency by modulating astrocytic function and excitatory amino acid transporter 2 (EAAT2) expression [30]. Moreover, NaHS attenuated degeneration of dorsal root ganglion neurons and sciatic nerve axons in diabetic neuropathy by activating antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) and downregulating aldose reductase expression (Figure 2a, Table 1) [31].

In cerebral I/R models, NaHS inhibited rho-associated protein kinase 2 (ROCK2) expression and activation through phosphorylation at Thr436 and Ser575. For instance, in bilateral carotid artery occlusion, NaHS markedly reduced lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), neuron-specific enolase (NSE), ROCK2, and bcl-2-associated x protein (Bax) expression, while increasing b-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) levels and suppressing oxidative stress, leading to improved cognitive outcomes. Notably, these effects were abolished by mutations at Thr436 or Ser575 [32]. In cultured hippocampal neurons, NaHS inhibited phosphorylation of ROCK2, polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1), and protein kinase A (PKA), decreased ROCK2, LDH, NSE, and intracellular Ca2+ levels, and enhanced cell viability under hypoxia/reoxygenation conditions via similar phosphorylation sites [33]. Furthermore, NaHS exhibited neuroprotective properties in cardiac arrest models by reducing brain edema and BBB disruption through inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) expression and stabilization of occludin (Figure 2b, Table 1) [34].

In lateral percussion models of TBI, subchronic NaHS administration prevented hypertension, vascular dysfunction, and oxidative stress in the aorta while restoring expression of H2S-synthesizing enzymes and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) phosphorylation. These effects were abolished by co-administration of L-NAME, confirming the NO-dependence of the mechanism [35]. In a related study, NaHS prevented tachycardia, hypertension, and sympathetic hyperactivity, and reduced vasopressor responses to norepinephrine [36]. Additionally, after severe TBI, NaHS restored the expression of key H2S-synthesizing enzymes, such as CBS and CSE, in neural tissue, correlating with posttraumatic stage and brain region [37]. Microinjections of NaHS into the hypothalamus were also shown to lower arterial pressure and sympathetic activity by restoring n-methyl-d-aspartate receptor subunit 1 (NMDAR1) disulfide bonds in ischemic stroke models [38]. Moreover, NaHS reduced demyelination, apoptosis, and expression of platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRα), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), nuclear factor kappa b (NF-κB), and interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), while improving locomotor and cognitive functions (Figure 2a, Table 1) [39].

Another fast-releasing H2S donor, sodium sulfide (Na2S), has also demonstrated promising neuroprotective potential. In models of intracerebral hemorrhage, Na2S inhibited neurotoxic processes such as neuronal death, axonal degradation, impaired axonal transport, and inflammation mediated by CXC motif ligand 2. Interestingly, another sulfide donor, Na2S3, did not prevent neuronal death or inflammatory activation but otherwise produced effects similar to Na2S [40]. In global cerebral I/R, Na2S inhibited caspase-3 activity through persulfidation of Cys163, reducing mortality and mitigating neurological deficits. This neuroprotective effect appeared to be mediated by sodium thiosulfate (STS), as Na2S administration significantly increased plasma and brain thiosulfate levels, transported across membranes by the sodium sulfate cotransporter SLC13A4 (NaS-2) (Table 1) [41].

Our previous studies also demonstrated that Na2S reduced the number of TUNEL-positive neurons and glial cells after TBI and axotomy, likely through H2S-dependent downregulation of the proapoptotic protein p53. Conversely, inhibition of CBS with aminooxyacetic acid (AOAA) enhanced apoptosis, confirming CBS as a key mediator of H2S-induced neuroprotection [19]. In subsequent work, we found that p53 colocalized with damaged neurons and glial cells exhibiting nuclear fragmentation after severe TBI [21]. Moreover, Na2S decreased the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and amyloid precursor protein (APP) in injured neural tissue at 24 h and 7 days post-TBI, whereas AOAA increased their expression. Computational modeling further revealed specific binding sites for H2S and its derivatives on iNOS and APP, supporting molecular mechanisms underlying H2S-mediated neuroprotection (Figure 2a, Table 1) [20].

Sodium thiosulfate (STS) is also considered a promising inorganic H2S donor. In glial cells, STS increased H2S and glutathione (GSH) levels while decreasing tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and activation of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38 MAPK) and nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) pathways, thus exerting time- and dose-dependent neuroprotective effects [42]. However, other studies reported no significant effects of STS on brain tissue damage in hemorrhagic shock models, likely due to an intact BBB preventing its penetration [43]. STS has also been shown to stimulate vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-dependent angiogenesis in hindlimb ischemia by inhibiting mitochondrial respiration and promoting glycolysis in endothelial cells (Table 1) [44].

In our experiments, STS reduced neuronal and astrocytic apoptosis after severe TBI through inhibition of p53-dependent cell death pathways. Conversely, inhibition of H2S synthesis enhanced p53 expression and apoptosis, confirming the modulatory role of H2S. Molecular dynamics simulations indicated that H2S does not form stable complexes with p53 but induces wave-like fluctuations in its conformational dynamics, particularly through weak van der Waals interactions with residues such as Arg248. This may reduce p53’s DNA-binding affinity and modulate its proapoptotic activity, thereby conferring neuroprotection under ischemic conditions associated with low pH, typical of the TBI microenvironment. Such pH-dependent effects of H2S, manifested as increased neutral H2S species during acidosis, may act as a metabolic sensor, indirectly regulating p53 transcriptional activity and promoting neuronal survival after injury (Table 1) [21].

Recent interest has also focused on thiol-activated carbonyl sulfide/hydrogen sulfide (COS/H2S) donors with fluorescent properties, enabling real-time tracking of H2S generation in vivo [45]. These COS/H2S donors can additionally serve as molecular platforms for the targeted delivery of fluorophores or therapeutic agents [46]. Among these, alanyl-carbonyl sulfide (AlaCOS) represents a particularly promising donor capable of tissue-specific H2S release upon activation by aminopeptidase N (APN). Incorporation of a coumarin fluorophore into AlaCOS permits visualization of H2S generation, offering a valuable tool for both mechanistic and translational neurotrauma research (Table 1) [47].

Table 1.

Neuroprotective effects of inorganic H2S donors in experimental models of nervous system injury. Arrows ↑ and ↓ denote increase and decrease, respectively. Abbreviations. Main active substance: H2S—hydrogen sulfide. Inorganic H2S donors: NaHS—sodium hydrosulfide; Na2S—sodium sulfide; Na2S3—sodium trisulfide; STS—sodium thiosulfate; COS/H2S—thiol-activated H2S donor based on carbonyl sulfide; AlaCOS—alanine-containing thiol-activated H2S donor. Main injury models: TBI—traumatic brain injury; BBB—blood–brain barrier; ICH—intracerebral hemorrhage; I/R—ischemia/reperfusion; CPR—cardiopulmonary resuscitation; OGD/R—oxygen-glucose deprivation/reoxygenation; CCI—chronic constriction injury of the sciatic nerve; CPZ—cuprizone (demyelination model); HLI—hindlimb ischemia; MCAO—middle cerebral artery occlusion. Key molecular targets and signaling pathways: K_ATP channels—ATP-sensitive potassium channels of mitochondria; ROCK2—Rho-associated kinase 2; PLK1—polo-like kinase 1; PKA—protein kinase A; p53—tumor suppressor p53; p-eNOS—phosphorylated endothelial NO synthase; NR1/NMDAR1—subunit 1 of NMDA receptor; CaMKII—calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II; NF-κB—nuclear factor kappa B; p38 MAPK—p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Enzymes of H2S synthesis and inhibitors: CBS—cystathionine-β-synthase; CSE—cystathionine-γ-lyase; AOAA—aminooxyacetic acid; L-NAME—Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester. Protein markers of damage and inflammation: Bax—proapoptotic Bcl-2 family protein; Bcl-2—antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family protein; LDH—lactate dehydrogenase; NSE—neuron-specific enolase; iNOS—inducible NO synthase; APP—amyloid precursor protein; GFAP—glial fibrillary acidic protein; PDGFRα—platelet-derived growth factor receptor α; MLKL—mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein. Cytokines and inflammatory mediators: IL-1β—interleukin-1β; IL-6—interleukin-6; IL-17—interleukin-17; TNFα—tumor necrosis factor α. Neurotrophic and synaptic proteins: BDNF—brain-derived neurotrophic factor; ARC—activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein; PSD-95—postsynaptic density protein 95. Transporters and barrier proteins: EAAT2—excitatory amino acid transporter 2; occludin—tight junction protein; MMP-9—matrix metalloproteinase-9; SLC13A4/NaS-2—thiosulfate transporter. Antioxidant systems: GSH—reduced glutathione; SOD/SOD2—superoxide dismutase 1 and 2. Apoptosis markers: TUNEL—terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling. Cell lines and experimental systems: SH-SY5Y—human neuroblastoma cell line; THP-1—human monocyte cell line; U373—human astrocyte cell line; HUVEC—human umbilical vein endothelial cells; HeLa—human cervical carcinoma cell line; RAW264.7—mouse macrophage cell line. Other: PVN—paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus; PSH—post-stroke sympathetic hyperactivity; BP—blood pressure; LPS—lipopolysaccharide; IFNγ—interferon gamma; VEGF—vascular endothelial growth factor; VEGFR2—VEGF receptor 2; PFKFB3—6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 3; eNOS—endothelial NO synthase; EdU—5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (proliferation marker), ERG—endothelial regulatory gene; 3PO—PFKFB3 inhibitor; 2-DG—2-deoxyglucose; APN—aminopeptidase N; CA—carbonic anhydrase; CAM—chick embryo chorioallantoic membrane; NIR—near-infrared; MTT—3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide.

Table 1.

Neuroprotective effects of inorganic H2S donors in experimental models of nervous system injury. Arrows ↑ and ↓ denote increase and decrease, respectively. Abbreviations. Main active substance: H2S—hydrogen sulfide. Inorganic H2S donors: NaHS—sodium hydrosulfide; Na2S—sodium sulfide; Na2S3—sodium trisulfide; STS—sodium thiosulfate; COS/H2S—thiol-activated H2S donor based on carbonyl sulfide; AlaCOS—alanine-containing thiol-activated H2S donor. Main injury models: TBI—traumatic brain injury; BBB—blood–brain barrier; ICH—intracerebral hemorrhage; I/R—ischemia/reperfusion; CPR—cardiopulmonary resuscitation; OGD/R—oxygen-glucose deprivation/reoxygenation; CCI—chronic constriction injury of the sciatic nerve; CPZ—cuprizone (demyelination model); HLI—hindlimb ischemia; MCAO—middle cerebral artery occlusion. Key molecular targets and signaling pathways: K_ATP channels—ATP-sensitive potassium channels of mitochondria; ROCK2—Rho-associated kinase 2; PLK1—polo-like kinase 1; PKA—protein kinase A; p53—tumor suppressor p53; p-eNOS—phosphorylated endothelial NO synthase; NR1/NMDAR1—subunit 1 of NMDA receptor; CaMKII—calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II; NF-κB—nuclear factor kappa B; p38 MAPK—p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Enzymes of H2S synthesis and inhibitors: CBS—cystathionine-β-synthase; CSE—cystathionine-γ-lyase; AOAA—aminooxyacetic acid; L-NAME—Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester. Protein markers of damage and inflammation: Bax—proapoptotic Bcl-2 family protein; Bcl-2—antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family protein; LDH—lactate dehydrogenase; NSE—neuron-specific enolase; iNOS—inducible NO synthase; APP—amyloid precursor protein; GFAP—glial fibrillary acidic protein; PDGFRα—platelet-derived growth factor receptor α; MLKL—mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein. Cytokines and inflammatory mediators: IL-1β—interleukin-1β; IL-6—interleukin-6; IL-17—interleukin-17; TNFα—tumor necrosis factor α. Neurotrophic and synaptic proteins: BDNF—brain-derived neurotrophic factor; ARC—activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein; PSD-95—postsynaptic density protein 95. Transporters and barrier proteins: EAAT2—excitatory amino acid transporter 2; occludin—tight junction protein; MMP-9—matrix metalloproteinase-9; SLC13A4/NaS-2—thiosulfate transporter. Antioxidant systems: GSH—reduced glutathione; SOD/SOD2—superoxide dismutase 1 and 2. Apoptosis markers: TUNEL—terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling. Cell lines and experimental systems: SH-SY5Y—human neuroblastoma cell line; THP-1—human monocyte cell line; U373—human astrocyte cell line; HUVEC—human umbilical vein endothelial cells; HeLa—human cervical carcinoma cell line; RAW264.7—mouse macrophage cell line. Other: PVN—paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus; PSH—post-stroke sympathetic hyperactivity; BP—blood pressure; LPS—lipopolysaccharide; IFNγ—interferon gamma; VEGF—vascular endothelial growth factor; VEGFR2—VEGF receptor 2; PFKFB3—6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 3; eNOS—endothelial NO synthase; EdU—5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (proliferation marker), ERG—endothelial regulatory gene; 3PO—PFKFB3 inhibitor; 2-DG—2-deoxyglucose; APN—aminopeptidase N; CA—carbonic anhydrase; CAM—chick embryo chorioallantoic membrane; NIR—near-infrared; MTT—3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide.

| Donor | Model, Animals, Concentration/Dose | Main Effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| NaHS | TBI, mice, 3.1 mg·kg−1 for seven days | ↑ H2S in brain, ↓ oxidative stress, ↑ synaptic proteins, improvement of dendrites and spines, restoration of cognitive and motor functions (Barnes maze, object recognition), modulation of NMDA, glutamate, Ca2+, CaMKII. | [26] |

| NaHS | TBI, mice, 50 µmol/kg body weight for 7 days | ↓ neuroinflammation and oxidative stress, ↑ BDNF, ARC, PSD-95, restoration of cognitive functions. | [27] |

| NaHS | Controlled cortical impact, rats and mice, 3 mg/kg 5 min post-injury | ↓ brain edema, BBB permeability, lesion volume; activation of mitochondrial K_ATP channels, antioxidant protection. | [28] |

| NaHS | Chronic constriction injury of sciatic nerve (CCI), 4.43 nmol/mouse, intrathecal | Prevention of dopaminergic neuron death via ↓ IL-17 → necroptosis, ↓ MLKL, tyrosine hydroxylase. | [29] |

| NaHS | Peripheral nerve injury, mice, 10 µmol/mL, i.p. daily for 14 days | ↓ glutamate in spinal cord, ↓ impulsation in somatosensory cortex, astrocyte modulation, ↑ EAAT2. | [30] |

| NaHS | Diabetic neuropathy, rats, 50 µmol/kg/day i.p. for 2 weeks | ↓ degeneration of ganglia and sciatic nerve axons, ↑ SOD/SOD2, ↓ aldose reductase. | [31] |

| NaHS | Cerebral I/R (bilateral carotid artery occlusion) in rats transfected with wild-type and mutant ROCK2 eukaryotic plasmids in hippocampus, 4.8 mg/kg | Inhibition of ROCK2 (phosphorylation Thr436/Ser575), ↓ LDH, NSE, Bax, ROCK2; ↑ Bcl-2, ↓ oxidative stress, improved cognitive functions. | [32] |

| NaHS | Hypoxia/reoxygenation (hippocampal neuron culture), 50, 100 and 200 µmol/L | ↓ ROCK2 via PLK1 and PKA, ↓ Ca2+, LDH, NSE; ↑ cell viability. | [33] |

| NaHS | Cardiac arrest, rats, 0.5 mg/kg i.v. at start of CPR, then maintenance infusion (1.5 mg·kg−1·h−1) for 6 h after ROSC | ↓ brain edema, BBB degradation, ↓ MMP-9, stabilization of occludin. | [34] |

| NaHS | Lateral fluid percussion TBI (subchronic), rats, 3.1 mg/kg i.p. daily for six days | Prevention of post-traumatic hypertension, vascular dysfunction, aortic oxidative stress; restoration of H2S-synthesizing enzymes and p-eNOS (blocked by L-NAME). | [35] |

| NaHS | Lateral fluid percussion TBI, rats, 3.1 and 5.6 mg/kg i.p. for seven days | ↓ tachycardia, hypertension, sympathetic hyperactivity, restoration of vasopressor responses to noradrenaline. | [36] |

| NaHS | TBI, lateral fluid percussion, rats, 3.1 mg/kg i.p. for seven days | Restoration of CBS and CSE levels in nervous tissue. | [37] |

| NaHS | Patients with ischemic stroke (MCI vs. NMCI)—no NaHS administered (only endogenous H2S and noradrenaline measured in plasma); rats: focal ischemic stroke (MCAO 90–120 min), bilateral microinjections of NaHS µM/100 nl into PVN | Patients: malignant infarction and PSH → ↓ endogenous H2S, ↑ plasma noradrenaline, positive correlation with damage markers, ↓ one-year survival. Rats: NaHS completely abolished PSH, ↓ BP and renal sympathetic activity, eliminated AOAA effect, restored disulfide bonds of NR1 NMDA receptor. | [38] |

| NaHS | Experimental multiple sclerosis model in rats induced by cuprizone (CPZ), rats, 50 and 100 µmol/kg, 14 days | ↓ demyelination, apoptosis, PDGFRα, GFAP, NF-κB, IL-1β; improved locomotion and cognitive functions, but at 100 µmol/kg, the effect of NaHS decreased. | [39] |

| Na2S, Na2S3 | Intracerebral hemorrhage (intrastriatal collagenase injection), mice, 25 µmol/kg i.p. 30 min before ICH induction | Na2S: significant improvement of sensorimotor functions, ↓ striatal neuron death, protection of axons and axonal transport, ↓ inflammatory mediators. Na2S3: protection of axons and axonal transport (comparable to Na2S), but no protection of neurons or suppression of inflammation; no improvement of sensorimotor functions. | [40] |

| Na2S, STS | 1. In vitro: OGD/R in SH-SY5Y and primary mouse cortical neurons, Na2S 0.5 mmol/L (500 µM) added 5 h after OGD, STS 0.25 mmol/L (250 µM); 2. In vivo: global cerebral ischemia–reperfusion, mice, STS 10 mg/kg i.v. 1 min after reperfusion start + 10 mg/kg/day for 7 days | Na2S: almost no protection by itself; entire neuroprotective effect fully mediated by rapid oxidative metabolite—thiosulfate (increased thiosulfate, not H2S, in plasma and brain). STS: fully reproduces and substitutes all protective effects of Na2S; significantly ↑ cell and animal survival, improved neurological functions; antiapoptotic action via persulfidation of Cys163 of caspase-3; cellular uptake via NaS-2 (SLC13A4). | [41] |

| Na2S | 1. TBI (controlled cortical impact), mice, 0.1 mg/kg daily i.p. for 7 days; 2. Axotomy (complete axon transection) in mechanoreceptor neuron, freshwater crayfish Astacus leptodactylus, 250 µM | ↓ expression and nuclear translocation of p53 in neurons and glial cells at 24 h and 7 days post-TBI; ↓ apoptosis (TUNEL+), ↓ Bax, protection of neurons and glial cells; in axotomy model—↓ nuclear p53 in cytoplasm, axon and dendrites of motoneurons, ↓ apoptosis of satellite glia. Opposite effect with AOAA. | [19] |

| Na2S | 1. TBI (controlled cortical impact), mice, 0.1 mg/kg daily i.p. for 7 days; 2. Axotomy, freshwater crayfish Astacus leptodactylus, 250 µM post-axotomy, assessed at 8 h | Significant ↓ iNOS and APP expression in neurons and astrocytes, ↓ apoptosis; in axotomy— ↓ iNOS and APP in motoneurons and axons. Opposite effect with AOAA. | [20] |

| Na2S/STS | TBI (controlled cortical impact), mice, 1000 mg/kg post-injury, in silico | ↓ apoptosis of neurons and astrocytes via p53 modulation (van der Waals interactions with Arg248), pH-dependent H2S effect as metabolic sensor. | [21] |

| NaHS, STS | In vitro: LPS/IFNγ-activated microglia and human THP-1 monocytes; IFNγ-activated astrocytes and U373 cells Concentration: 1–500 µM (optimal 100 µM, 8–12 h) | ↑ H2S and GSH in glial cells, ↓ TNFα and IL-6 release, ↓ p38 MAPK and NF-κB activation, significant neuroprotection of differentiated SH-SY5Y (MTT and LDH). | [42] |

| STS | Hemorrhagic shock (30% blood volume withdrawal + 3 h hypotension) followed by resuscitation, pigs with atherosclerosis Dose: 0.1 g·kg−1·h−1 i.v. for first 24 h of resuscitation | No effect (intact BBB prevents penetration), no differences in CSE, CBS, oxytocin/receptor, GFAP, nitrotyrosine in PVN; only minimal perivascular edema. | [43] |

| STS | Hindlimb ischemia (HLI) in C57BL/6 and hypercholesterolemic LDLR−/− mice, oral 2–4 g/L in drinking water (≈0.5–1 g/kg/day); in ovo angiogenesis model—chick embryo CAM, 500 µM; in vitro (HUVEC) | In vivo: stimulation of VEGF-dependent angiogenesis via inhibition of mitochondrial respiration and stimulation of glycolysis, ↑ capillary density and endothelial proliferation (EdU+/ERG+), ↓ muscle injury area. Optimal dose 2 g/L (4 g/L less effective → narrow therapeutic window). Effect only in peripheral tissues. In vitro: ↑ proliferation and migration, ↑ H2S and protein persulfidation, ↓ mitochondrial respiration → ↑ glycolysis and ATP, ↑ PFKFB3, eNOS, VEGFR2. Effect completely abolished by 3PO and 2-DG. | [44] |

| COS/H2S | In vitro (buffer + CA), live HeLa cells, in vivo in rats (subcutaneous alginate gel) | Thiol-dependent H2S release (>60%) + fluorescence turn-on. Palette: blue, yellow, orange, red and NIR. Direct correlation of fluorescence and H2S (electrode). Visualization of H2S in live cells and subcutaneously in rats. | [45] |

| AlaCOS | In vitro, LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages in full-thickness skin wound model in mice | Tissue-specific H2S delivery, activation by aminopeptidase N (APN), built-in coumarin fluorophore for imaging. | [47] |

3.2. Organic Synthetic H2S Donors

Organic synthetic H2S donors have been developed to provide slow, controlled, and more physiologically relevant H2S release, enabling them to mimic endogenous mechanisms of this gasotransmitter production. Owing to their modifiable chemical structures and diverse release mechanisms, these donors offer highly tunable pharmacokinetics with respect to onset, duration of action, and tissue specificity. In models of TBI, SCI, cerebral ischemia–reperfusion, neuropathic pain, and neurodegenerative diseases, they exhibit sustained and prolonged neuroprotection with comprehensive effects on cytotoxic processes. In addition, their high blood–brain barrier permeability and significantly lower toxicity compared to inorganic salts make this class of compounds the most promising candidates for further preclinical and clinical studies aimed at developing effective neuroprotective drugs [24,25,48,49].

GYY4137 is a slow-releasing H2S donor that has demonstrated neuroprotective effects in numerous pathological models of both the central and peripheral nervous systems, including neurotrauma. For example, in a spinal cord I/R model, administration of GYY4137 reduced neuronal loss through inhibition of cell death signaling mechanisms involving Bax, bcl-2-associated death promoter (Bad), caspase-mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein (caspase-MLKL), phosphorylated receptor-interacting protein 1/3 (p-RIP1/3), nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3), and pro-inflammatory factors. It also prevented Nissl body degradation, stabilized BBB permeability, and attenuated neuroinflammation [50]. The GYY4137-mediated protection of the BBB is thought to be related to H2S-dependent inhibition of autophagic degradation of occludin [51]. In the same I/R model, GYY4137 blocked apoptosis through suppression of p38 MAPK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2), and c-jun n-terminal kinase (JNK) phosphorylation (Table 2) [52].

Table 2.

Neuroprotective effects of organic synthetic H2S donors in experimental models of central and peripheral nervous system injury. Arrows ↑ and ↓ denote increase and decrease, respectively. Abbreviations. Main active substance: H2S—hydrogen sulfide. Synthetic and hybrid H2S donors: GYY4137—morpholinium phosphorodithioate derivative; SPRC/ZYZ-802—S-propargyl-L-cysteine; ACS67—latanoprost-H2S hybrid; ACS84—L-DOPA-H2S hybrid; ATB-346—naproxen-H2S hybrid; S-memantine—memantine-H2S hybrid; ADT-OH/ADT—5-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-3H-1,2-dithiole-3-thione; MTC—S-allyl-L-cysteine-gallic acid conjugate; NAC—N-acetyl-L-cysteine. Main injury models: TBI—traumatic brain injury; BBB—blood–brain barrier; I/R—ischemia/reperfusion; CPR—cardiopulmonary resuscitation; CA/CPR—cardiac arrest/cardiopulmonary resuscitation; MCAO—middle cerebral artery occlusion; BCAO—bilateral carotid artery occlusion; SCI—spinal cord injury; MPTP—1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine; 6-OHDA—6-hydroxydopamine; NMDA—N-methyl-D-aspartate; OGD—oxygen-glucose deprivation; Aβ—beta-amyloid; APP/PS1—transgenic Alzheimer’s disease mouse model; IOP—intraocular pressure. Key molecular targets and signaling pathways: K_ATP channels—ATP-sensitive potassium channels; MAPK—mitogen-activated protein kinases (p38 MAPK; ERK1/2; JNK); NF-κB—nuclear factor kappa B; PI3K/Akt—phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/Akt; MEK-ERK—mitogen-activated/extracellular signal-regulated kinase; AMPK—AMP-activated protein kinase; CaMKKβ—calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase β; LKB1—liver kinase B1; Nrf2—nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; HO-1—heme oxygenase-1; GCLC/GCLM—glutamate-cysteine ligase subunits. Enzymes of H2S synthesis and inhibitors: CBS—cystathionine-β-synthase; AOAA—aminooxyacetic acid. Apoptosis and necroptosis protein markers: Bax—Bcl-2-associated X protein; Bad—Bcl-2-associated death promoter; Bcl-2—B-cell lymphoma 2; p-RIP1/3—phosphorylated RIP1/RIP3; MLKL—mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein; NLRP3—NLRP3 inflammasome; PARP—poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase; TUNEL—terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling. Inflammatory and oxidative stress markers: TNF-α—tumor necrosis factor alpha; IL-1β—interleukin-1β; IL-6—interleukin-6; IL-10—interleukin-10; COX-2—cyclooxygenase-2; iNOS—inducible NO synthase; nNOS—neuronal NO synthase; NO—nitric oxide; NOX4—NADPH oxidase 4; ROS—reactive oxygen species; 8-OHdG—8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine; MDA—malondialdehyde. Antioxidant systems: SOD—superoxide dismutase; CAT—catalase; GPx—glutathione peroxidase; GSH—reduced glutathione. Neurotrophic and synaptic proteins: BDNF—brain-derived neurotrophic factor; TH—tyrosine hydroxylase; NF-L—neurofilament light chain; Thy-1—thymocyte antigen-1; synaptophysin—synaptic protein. BBB and tight junction proteins: occludin—tight junction protein; MMP-9—matrix metalloproteinase-9; VEGF—vascular endothelial growth factor. Other proteins and markers: GFAP—glial fibrillary acidic protein; Arg1—arginase-1; YM1—chitinase-3-like protein 3; CD24—cluster of differentiation 24; Src/Fak/Pyk2—microglia migration signaling pathway; β-catenin—beta-catenin; TCF7L2—transcription factor 7-like 2; c-Myc—oncogene c-Myc; Ngn1/2—neurogenin 1/2; α-synuclein—alpha-synuclein; APP—amyloid precursor protein; tPA—tissue plasminogen activator. Cell lines: SH-SY5Y—human neuroblastoma cell line; PC12—rat pheochromocytoma cell line; RGC-5—retinal ganglion cell line; BV2—mouse microglial cell line. Tests and assessment methods: MWM—Morris water maze; NOR—novel object recognition; ERG—electroretinography; LDH—lactate dehydrogenase; MTT—3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide cell viability assay.

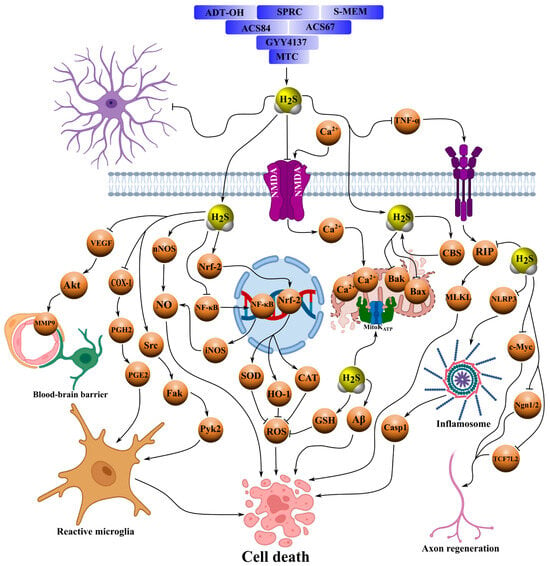

In isolated bovine ciliary body preparations, GYY4137 inhibited sympathetic neurotransmission by suppressing [3H]-norepinephrine release, partially through H2S generation, prostanoid production, and activation of K_ATP channels [53]. Moreover, GYY4137 reduced the number of TUNEL-positive retinal ganglion cells by inhibiting Ca2+-excitotoxicity induced by intravitreal NMDA injection [54]. It has also been reported that GYY4137 inhibits neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS), thereby reducing nitrosative stress and neuronal death in Parkinson’s disease models (Figure 3, Table 2) [55].

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the neuroprotective mechanisms of action of organic H2S donors, such as GYY4137, ACS67, ACS84, SPRC, ADT-OH and its derivatives, including ADT and ATB-346, S-memantine, and MTC, in various models of central and peripheral nervous system pathologies, including I/R, neurotrauma, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, stroke, and TBI. These compounds serve as therapeutic agents for neuroprotection in various neurological disorders. They provide slow release of H2S, suppressing apoptosis by inhibiting signaling pathways involving Bax, Bad, caspases, MLKL, and p-RIP1/3, as well as phosphorylation of p38 MAPK, ERK1/2, and JNK, thereby reducing Ca2+-excitotoxicity. They mitigate oxidative stress by blocking nitrosative stress, lipid peroxidation, and MDA levels, and attenuate neuroinflammation by inhibiting NLRP3, pro-inflammatory factors (TNF-α, IL-1β, COX-2, NO, iNOS, and NOX4) and signaling pathways NF-κB, p38-, and JNK-MAPK. In parallel, H2S donors activate antioxidant systems, increasing levels of GSH, SOD, CAT, and GPx, and stimulating nuclear translocation of Nrf2. They modulate microglia, shifting them toward an anti-inflammatory phenotype through activation of AMPK, and maintain BBB integrity by stabilizing permeability, preventing degradation of occludin and tight junctions, and reducing edema and extravasation. Additionally, these compounds promote regeneration by enhancing axonal growth, neuronal and oligodendrocyte differentiation, vascular remodeling, and microglial migration through the Src/Fak/Pyk2 pathway. They inhibit sympathetic neurotransmission by suppressing [3H]-norepinephrine release via activation of K_ATP and prostanoid production and modulate endogenous H2S synthesis through activation of CBS. H2S donors improve cognitive functions by reducing astrogliosis, lipofuscin deposition, the Aβ1–42/Aβ1–40 ratio, and ultrastructural neuronal damage. Arrows with pointed ends indicate activation, while blunt ends indicate inhibition.

Another notable H2S donor is ACS67, a latanoprost derivative with an H2S-releasing moiety. In a retinal ischemia model, intravitreal injection of ACS67 prevented pathological electroretinogram changes and attenuated the downregulation of retinal antigens and axonal proteins of the optic nerve, while enhancing the major antioxidant defense component—GSH [56]. Similarly, ACS67 inhibited electrically evoked [3H]-norepinephrine release in ocular tissues, an effect enhanced in the presence of the cyclooxygenase inhibitor flurbiprofen. This inhibitory effect was blocked by H2S synthesis inhibitors or K_ATP channel blockers (Figure 3, Table 2) [53].

A related H2S donor, ACS84—an L-DOPA derivative bearing an H2S-releasing group—also exhibits neuroprotective properties. For instance, ACS84 prevented neuronal death in the substantia nigra and inhibited lipid peroxidation, oxidative stress, and monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) activity, thereby improving motor performance and surpassing the effects of NaHS and L-DOPA in Parkinson’s disease models [57]. ACS84 additionally promoted nuclear translocation of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), upregulated antioxidant defense enzymes, increased GSH levels, and reduced malondialdehyde (MDA) concentration [58]. In microglial cultures, ACS84 inhibited amyloid beta 1–40 (Aβ1–40)-induced cytotoxicity through H2S-dependent suppression of nitric oxide (NO), TNF-α, and p38- and JNK-MAPK signaling, thereby preventing mitochondrial dysfunction (Figure 3, Table 2) [59].

The sulfur-containing amino acid SPRC (ZYZ-802) modulates endogenous H2S synthesis via CBS activation. In Alzheimer’s disease models, SPRC reduced astrogliosis, lipofuscin accumulation, and the amyloid beta 1–42/amyloid beta 1–40 (Aβ1–42/Aβ1–40) ratio through H2S-associated inhibition of NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling, while increasing CBS activity and H2S concentration. SPRC also suppressed Aβ-induced astrocyte activation, reducing TNF-α and nitrite production; these effects were blocked by CBS small interfering RNA (siRNA) or AOAA, protecting neurons from Aβ cytotoxicity [60]. It has been reported that SPRC mitigated cognitive impairment and ultrastructural neuronal damage by inhibiting TNF-α, cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), ERK1/2, and NF-κB following Aβ25–35 injection [61]. In ischemic stroke models, SPRC upregulated cluster of differentiation 24 (CD24) expression via the CBS/H2S signaling pathway, suppressing NF-κB and enhancing src/focal adhesion kinase/proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 (Src/Fak/Pyk2)-dependent microglial migration [62]. Furthermore, SPRC prevented hippocampal H2S depletion by inhibiting TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (TNFR1), Aβ, and NF-κB during neuroinflammation, thereby improving cognitive performance (Figure 3, Table 2) [63].

ADT-OH and its derivative anethole trithione (ADT) are slow H2S-releasing compounds involved in regeneration and anti-inflammatory processes. Studies on cultured neural progenitor cells (NPCs) have shown that ADT-OH modulates differentiation into neurons and oligodendrocytes, suppresses astrogliogenesis and apoptosis, and promotes axonal growth via upregulation of beta-catenin (β-catenin), transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCF7L2), cellular myc (c-Myc), and neurogenin 1/2 (Ngn1/2) [64]. In spinal cord injury models, ADT enhanced regeneration by reducing glial scarring, neuronal loss, and microglial activation, while promoting vascular remodeling in the lesion site [65]. ADT-OH induced a shift in microglia toward an anti-inflammatory phenotype through adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activation, suppressing M1 markers and enhancing M2 gene expression during neuroinflammation [66]. In a middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) model, both ADT-OH and NaHS maintained BBB integrity, reduced infarct volume, edema, and Evans blue extravasation, and prevented tight junction degradation by inhibiting iNOS, IL-1β, MMP9, and nadph oxidase 4 (NOX4) via NF-κB-dependent mechanisms [67]. In a similar stroke model, ADT-OH reduced tissue plasminogen activator (tPA)-enhanced hemorrhage by inhibiting the protein kinase b/vascular endothelial growth factor/matrix metalloproteinase 9 (Akt/VEGF/MMP9) pathway (Table 2) [68].

ATB-346, an H2S-releasing naproxen derivative, attenuated brain edema, neuronal death, and inflammation while restoring neurotrophic factors in a controlled cortical impact model of TBI in mice, although direct inhibition of H2S synthesis was not evaluated (Figure 3, Table 2) [69].

S-memantine, a novel H2S donor derived from memantine with an ACS48 moiety, reduced cell death in neuroblastoma and cortical neurons under ischemic conditions by attenuating Ca2+ excitotoxicity and GSH depletion [70]. Another donor, MTC (a conjugate of S-allyl-L-cysteine and gallic acid), protected neurons from I/R injury by activating several antioxidant enzymes, including SOD, catalase (CAT), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx), and by reducing LDH levels. It activated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase b (PI3K/AKT) and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (MEK/ERK) signaling, inhibited proapoptotic proteins, endoplasmic reticulum stress (ER) stress, two-pore domain potassium channel trek-1 (TREK-1), and inflammatory mediators, thereby promoting axonal regeneration and reducing neuronal damage (Figure 3, Table 2) [71].

Another promising H2S donor is N-acetylcysteine (NAC). In preclinical studies, NAC has repeatedly shown pronounced neuroprotective effects when administered within the first few hours after experimental TBI. For example, in a mouse model of severe TBI followed by secondary hypoxic insult, NAC started 2 h post-injury significantly reduced acute axonal damage and attenuated both early and delayed hippocampal neuron loss. However, NAC treatment did not affect the final cortical lesion volume and was not accompanied by improvement in long-term cognitive or behavioral outcomes compared with placebo-treated animals [72]. In addition, a Phase I randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in children aged 2–18 years with Glasgow Coma Scale ≤8 evaluated the safety and pharmacokinetics of the combination of N-acetylcysteine and probenecid administered enterally during the first days after injury. No serious adverse events related to the study treatment were recorded. Stable concentrations of both drugs were detected in cerebrospinal fluid for 72 h after treatment initiation. Nevertheless, no differences were found between the active-treatment and placebo groups in intracranial pressure, intensity of therapy, brain-injury biomarkers, or functional outcome at 3 months (Table 2) [73].

3.3. Natural H2S Donors

In addition to synthetic compounds, increasing attention is being paid to natural H2S donors, which provide gentle, thiol-dependent H2S release closely linked to endogenous pathways. Particular interest is focused on organosulfur metabolites from plants of the Allium (garlic, onion) and Brassicaceae (broccoli, cabbage) families, which serve as physiological reservoirs of H2S, which is slowly liberated under cellular conditions [74,75].

Thanks to their natural structural diversity and good bioavailability, these compounds exert pleiotropic effects on nervous tissue and demonstrate neuroprotective activity across a wide range of pathological conditions. Prolonged H2S release at physiological concentrations, excellent metabolic safety, and the ability to enhance the body’s own defense systems make natural organosulfur compounds not only promising nutraceutical agents but also an important tool for the prevention of neuropathologies and the maintenance of neuronal homeostasis.

DADS (diallyl disulfide), a garlic-derived allicin metabolite, reduced cerebral infarct volume by inhibiting astrocyte activation and pyroptosis mediated by the NLRP3/Caspase-1/IL-1β cascade, as well as by decreasing lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) expression and pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and interleukin-18 (IL-18), thereby promoting regenerative processes [76]. In sciatic nerve injury models, DADS enhanced the anti-allodynic and anti-hyperalgesic effects of μ- and δ-opioid receptor agonists through upregulation of their expression in dorsal root ganglia (DRG). Additionally, it inhibited oxidative stress and apoptosis in the medial septum and DRG via H2S-dependent signaling pathways [77]. In oxidative stress-induced cataract models, DATS (diallyl trisulfide) restored GSH content and SOD activity while reducing LDH-mediated cytotoxicity (Table 3) [78].

Table 3.

Neuroprotective effects of natural H2S donors in experimental models of nervous system injury. Arrows ↑ and ↓ denote increase and decrease, respectively. Abbreviations. Main active substance: H2S—hydrogen sulfide. Natural H2S donors: DADS—diallyl disulfide; DATS—diallyl trisulfide; SFN—sulforaphane; SAMe—S-adenosyl-L-methionine; GYY4137—morpholinium phosphorodithioate derivative. Main injury models: TBI—traumatic brain injury; BBB—blood–brain barrier; CCI—chronic constriction injury of the sciatic nerve; MCAo/MCAO—middle cerebral artery occlusion; cuprizone—demyelination and multiple sclerosis model. Key molecular targets and signaling pathways: Nrf2—nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; HO-1—heme oxygenase-1; AMPK—AMP-activated protein kinase; SIRT1—sirtuin 1; ULK1—UNC-51-like kinase 1; beclin1—autophagy protein Beclin-1. Inflammatory and pyroptotic pathways: NLRP3—NLRP3 inflammasome; GSDMD—gasdermin D; IL-1β—interleukin-1β; IL-17—interleukin-17; NF-κB—nuclear factor kappa B. Antioxidant systems and redox status: GSH—reduced glutathione; SOD—superoxide dismutase; TAC—total antioxidant capacity. BBB; brain edema and endothelial proteins: AQP4—aquaporin-4; vWF—von Willebrand factor; RECA-1—rat endothelial cell antigen-1. Markers of glial activation and demyelination: GFAP—glial fibrillary acidic protein. Other: DRG—dorsal root ganglia; LDH—lactate dehydrogenase.

Another natural H2S donor of interest is S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe), which exhibited even stronger neuroprotective effects than DADS in cuprizone-induced demyelination, effectively suppressing demyelinating pathology. Both H2S modulators reduced neuroinflammation, enhanced oligodendrocyte activity and autophagy via the AMPK/sirtuin 1/unc-51-like autophagy activating kinase 1/beclin 1 (AMPK/SIRT1/ULK1/beclin1) pathway, increased antioxidant levels (GSH and total antioxidant capacity (TAC)), and inhibited fibronectin aggregation as well as NF-κB and IL-17 expression (Table 3) [79].

Particular interest is focused on the natural isothiocyanate sulforaphane (SFN) from broccoli sprouts, which acts as a slow H2S donor. In a rat model of transient middle cerebral artery occlusion, pre-treatment with SFN markedly increased Nrf2 and HO-1 expression in cerebral microvessels and perivascular astrocytes, significantly reducing BBB disruption, infarct volume, and neurological deficit [80]. SFN also protected the brain in TBI models by decreasing edema and BBB permeability through Nrf2 pathway activation. When administered as early as 1 h post-TBI, SFN significantly improved spatial memory and working memory; however, the beneficial effect was completely lost if treatment was delayed to 6 h [81]. SFN prevented TBI-induced downregulation of AQP4 at the injury site, increased aquaporin-4 (AQP4) expression in the penumbra, and markedly reduced brain edema by enhancing water clearance through aquaporin channels [82]. A clinical trial (NCT04252261) is planned in which 90 patients with frontal lobe injuries will receive SFN or placebo for 12 weeks to assess its effects on cognitive functions. It is expected that SFN will reduce cognitive deficit and improve memory and learning (Table 3) [83].

3.4. Innovative Multicomponent Hybrid H2S Donors

Significant progress in the therapeutic application of H2S is demonstrated by innovative delivery systems that incorporate it into nanostructures, biomaterials, and adaptive polymer matrices. These platforms are forging a new direction in regenerative medicine, as they not only transport H2S to the target site but also ensure its local, prolonged, and physiologically relevant release synchronized with the microenvironment of damaged nervous tissue. Their architecture—ranging from nanoparticles and liposomes to functional hydrogels and metal–organic frameworks—enables precise control over release kinetics, bioavailability, tissue selectivity, and interaction with diverse cellular targets. A key advantage of such systems is their ability to combine transport, protective, and therapeutic functions in a single platform: nanoparticles can deliver H2S deep into the lesion while protecting it from premature degradation, and hydrogels create a stable biocompatible niche that supports regenerative processes [84]. It is precisely for this reason that innovative carriers have become the main tool for realizing the potential of H2S in the treatment of injuries to both the central and peripheral nervous systems. The use of these materials overcomes the limitations of traditional H2S donors—instability, systemic toxicity, and a narrow therapeutic window—providing targeted and long-term neuroprotective effects [85,86].

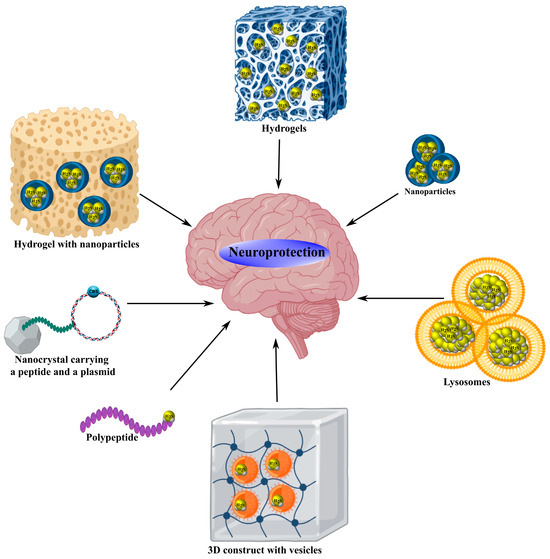

In a spinal cord injury model, G16 MPG-ADT nanoparticles (186.5 nm) carrying a specialized H2S-associated neuroprotective agent effectively released H2S, which promoted regeneration of damaged neurons via upregulation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) expression, resulting in improved motor recovery [87]. Similarly, zinc sulfide nanoparticles (ZnS NPs) in ischemic stroke models reduced infarct volume by continuously generating H2S, protecting neurons from apoptosis, stimulating neurovascularization through phosphorylated adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (p-AMPK) modulation, and alleviating inflammatory responses [88]. Polyethylene glycol (PEG)- and lactoferrin (LF)-modified mesoporous iron oxide nanoparticles (MIONs) conjugated with diallyl trisulfide (DATS@MION-PEG-LF) provided sustained H2S release in the brain during ischemic injury. These nanoparticles exhibited excellent biocompatibility without eliciting cytotoxic or antigenic responses, while demonstrating antiapoptotic, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant effects (Figure 4, Table 4) [89].

Figure 4.

Neuroprotective mechanisms of hybrid H2S donors. Innovative hybrid H2S donors, including G16 MPG-ADT nanoparticles, ZnS NP, DATS@MION-PEG-LF, AP39@Lip liposomes, CdSe/ZnS nanocrystals with angiotensin-1 peptide and CSE plasmid, GelMA@LAMC, H2S@SF, SF-G@Mn, mPEG-PA-PP, MnS@AC hydrogels, PF-127@OMSN-JK hydrogel with nanoparticles, Zn-CA MOF, DATS-MSN, 3D/GelMA/EVs construct with vesicles, and SHI polypeptide, provide controlled H2S release, effectively suppressing apoptosis by inhibiting signaling pathways involving Bax, Bad, caspases, MLKL, and MAPK, reducing oxidative stress by decreasing MDA, NO, and iNOS, and attenuating neuroinflammation by blocking NLRP3, TNF-α, IL-1β, and NF-κB. These structures activate antioxidant systems, increasing levels of GSH, SOD, CAT, GPx, and Nrf2, modulate microglia via AMPK and PINK1/Parkin, stabilize BBB permeability, stimulate neuronal regeneration, angiogenesis, and cell migration through mTOR, STAT3, and Src/Fak/Pyk2, improving motor and cognitive functions in models of ischemia/reperfusion, neurotrauma, stroke, TBI, and Parkinson’s disease.

Table 4.

Neuroprotective effects of modern nano- and macro-carriers, hydrogels, and targeted H2S donors in experimental models of neurotrauma and ischemia. Arrows ↑ and ↓ denote increase and decrease, respectively. Abbreviations. Main active substance: H2S—hydrogen sulfide. Targeted and mitochondria-directed donors: AP39—mitochondria-targeted slow-releasing H2S donor; HSD-R—ROS-responsive self-degrading mitochondria-targeted H2S donor. Natural and hybrid donors in nanosystems: DADS—diallyl disulfide; DATS—diallyl trisulfide; SFN—sulforaphane; ADT/ADT-OH—5-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-3H-1,2-dithiole-3-thione; SHI—sulfur-containing insulin-like polypeptide. Nano- and microcarriers: MPG-ADT—peptide-targeted polymeric nanoparticles with ADT; ZnS NP—zinc sulfide nanoparticles; MION—mesoporous iron oxide nanoparticles; PEG—polyethylene glycol; LF—lactoferrin; MSN—mesoporous silica nanoparticles; MOF—metal–organic framework (Zn-CA); RBC—red blood cell membrane; GelMA—gelatin methacryloyl; PF-127—Pluronic F-127; Fe3S4—magnetic iron sulfide clusters; SF—silk fibroin; MnS@AC—manganese sulfide in activated carbon. Main injury models: TBI—traumatic brain injury; SCI—spinal cord injury; ICH—intracerebral hemorrhage; HI—hypoxic–ischemic brain injury; CPR—cardiopulmonary resuscitation; MCAO—middle cerebral artery occlusion; CCI—controlled cortical impact. Key signaling pathways and targets: mTOR—mammalian target of rapamycin; STAT3—signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; p-AMPK—phosphorylated AMP-activated protein kinase; PINK1/Parkin—mitophagy pathway; CHOP/GRP78/eIF2α—endoplasmic reticulum stress markers; ERK1/2—extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2; NF-κB—nuclear factor kappa B; miR-7a-5p—microRNA-7a-5p; GLT-1—glutamate transporter-1; VGLUT1—vesicular glutamate transporter 1; TrkA/TrkB—neurotrophin receptors; proNGF-p75NTR—pro-neurotrophin and its receptor; BDNF—brain-derived neurotrophic factor; bFGF—basic fibroblast growth factor. Markers of inflammation and oxidative stress: IL-6—interleukin-6; TNF-α—tumor necrosis factor alpha; MPO—myeloperoxidase; MDA—malondialdehyde; ROS—reactive oxygen species; SOD—superoxide dismutase; CAT—catalase. Markers of apoptosis and cell death: Bax—proapoptotic protein; Bcl-2—antiapoptotic protein; caspase-3—caspase-3; Bid/Apaf-1/p53—proapoptotic mediators. Cell lines and cell types: HUVEC—human umbilical vein endothelial cells; SH-SY5Y—human neuroblastoma cell line; BV2—mouse microglia; RAW264.7—mouse macrophages; RSC96—rat Schwann cells; HT22—mouse hippocampal neurons; DPSC—dental pulp stem cells; NSC—neural stem cells; H9c2—rat cardiomyocytes. Functional outcomes: MMP—mitochondrial membrane potential; CMAP—compound muscle action potential; SFI—sciatic functional index. Other: BBB—blood–brain barrier; MSC—mesenchymal stem cells; EVs—exosomes; cGAS-STING—innate immunity pathway; COX-2—cyclooxygenase-2; NSAIDs—non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Liposomes encapsulating AP39 also exhibited remarkable H2S-dependent neuroprotective properties, including preservation of BBB integrity, reduction in oxidative stress, and mitigation of mitochondrial dysfunction [90]. Notably, cadmium selenide/zinc sulfide (CdSe/ZnS) nanocrystals conjugated with angiotensin-1 peptides were used to deliver CSE plasmids for localized H2S production in injured myocardial cells, leading to reduced infarct size, oxidative stress, and mitophagy via inhibition of the c/ebp homologous protein/glucose-regulated protein 78/eukaryotic initiation factor 2 alpha (CHOP/GRP78/eIF2α) signaling pathway (Figure 4, Table 4) [91].

Hydrogels capable of H2S release have also shown substantial therapeutic potential for neurotrauma treatment. For example, the composite hydrogel GelMA@LAMC, incorporating an H2S donor activated by ROS and integrated into a zinc–citrate metal–organic framework, inhibited oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and mitochondrial dysfunction, while protecting neurons and stimulating angiogenesis after SCI [92]. A thermosensitive hydrogel pluronic f-127 (PF-127) containing ordered mesoporous silica nanoparticles (OMSN) loaded with JK (OMSN@JK), combined with stem cells was utilized for SCI therapy (Table 4). This hydrogel demonstrated excellent biocompatibility and neuroprotective efficacy by promoting neuronal differentiation and regeneration while suppressing neuroinflammatory processes [93].

A ferrofluid-based hydrogel containing Fe3S4 (FFH) reduced inflammatory factor expression through NF-κB pathway inhibition and participated in axonal remodeling, improving functional recovery after spinal cord injury [94]. Moreover, an H2S-associated silk fibroin hydrogel (H2S@SF) used in intracerebral hemorrhage models enabled sustained H2S release, which stabilized cerebral water homeostasis, reduced lesion area, and limited neuronal death in the striatum, cortex, and hippocampus [95]. H2S@SF also proved effective in TBI models by suppressing pyroptosis and necroptosis, alleviating edema, neuroinflammation, and neurodegenerative changes, and improving cognitive performance (Table 4) [96].

A related adaptive hydrogel based on a silk fibroin matrix, SF-G@Mn, provided gradual release of H2S, Mn2+, and bFGF, thereby modulating both acute and chronic posttraumatic stages of spinal cord injury. SF-G@Mn inhibited oxidative stress and neuroinflammation while promoting regenerative processes associated with axonal growth and myelin production (Figure 4, Table 4) [97].

In a recent study, a unique 3D-printed scaffold (3D/GelMA/EVs) based on gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA) hydrogel integrated with extracellular vesicles from H2S-preconditioned mesenchymal stromal cells was developed. This construct, tested in a spinal cord injury model, enhanced miR-7a-5p expression and improved motor function recovery [98]. In peripheral nerve transection models, a polymeric hydrogel mPEG-PA-PP containing an H2S donor localized within a ROS-sensitive polymer suppressed oxidative stress, inflammation, and mitochondrial dysfunction, thereby stimulating neuroregenerative processes (Table 4) [99].

A pH-sensitive polysaccharide hydrogel MnS@AC containing α-phase manganese sulfide nanoparticles (MnS NPs) inhibited inflammation while promoting proliferation and angiogenesis, with MnS NPs not affecting the pro-inflammatory cyclic gmp-amp synthase-stimulator of interferon genes (cGAS–STING) pathway (Figure 4, Table 4) [100].

A novel photoresponsive H2S donor for nerve regeneration has been proposed—an implantable Zn–CA metal–organic framework (MOF) matrix enabling controlled release of H2S and Zn2+. The combination of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, together with angiogenesis stimulation and guided cellular migration, contributed to efficient neural and motor recovery [101]. In an I/R injury model, a thermosensitive polymer poly(n-isopropylacrylamide-co-n-tert-butylacrylamide) (PNNTBA) coating mesoporous silica nanoparticles conjugated with diallyl trisulfide (DATS-MSN) provided prolonged H2S release through its soluble polymeric shell, exerting cytoprotective effects [102]. Another hybrid H2S donor, consisting of MIONs loaded with DATS and enclosed within an erythrocyte membrane shell (RBC-DATS-MION), ensured effective and sustained H2S release associated with antiapoptotic activity (Table 4) [103].

Development of H2S-associated polypeptides represents another promising therapeutic direction for diverse pathological conditions, including neurotrauma. For instance, the designed insulin-derived polypeptide insulin-derived polypeptide (SHI), capable of donating H2S, reduced α-synuclein levels, increased dopamine transporter (DAT) expression, and improved behavioral outcomes in Drosophila and C. elegans Parkinson’s disease models (Figure 4, Table 4) [104].

The mitochondrial donor AP39 reduced infarct size, reactive microglial activation, and pro-inflammatory markers such as ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1 (Iba1), IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, as well as the proneurotrophin growth factor-p75 neurotrophin receptor/sortilin/caspase-3 (proNGF–p75NTR–sortilin/caspase-3) axis, while inducing neuroprotective BDNF–tropomyosin receptor kinase b (BDNF–TrkB) and nerve growth factor-tropomyosin receptor kinase a (NGF–TrkA) signaling during cerebral ischemia [105]. In similar models, AP39 alleviated excitotoxicity by reducing glutamate and vesicular glutamate transporter 1 (VGLUT1) levels and upregulating glutamate transporter-1 (GLT-1) expression [106]. In a photothrombotic stroke model, AP39 decreased infarct volume and promoted mitophagy via activation of the PINK1/Parkin pathway, showing sex-dependent effects (Table 4) [107].

An improved formulation, AP39@Lip (liposome-integrated AP39), administered intranasally, provided targeted mitochondrial delivery in neurons during acute brain injury. AP39@Lip exhibited strong neuroprotective properties by mitigating mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and apoptosis, with its antiapoptotic effects attributed to inhibition of ERK1/2 and caspase-1 activation (Figure 4) [108]. Another novel ROS-responsive H2S donor, HSD-R, demonstrated selective mitochondrial targeting, where it reduced apoptosis via inhibition of bh3-interacting domain death agonist/apoptotic protease activating factor-1/proapoptotic protein p53 (Bid/Apaf-1/p53) signaling, attenuated inflammation, and promoted angiogenesis (Table 4) [109].

Hybrid molecules based on SFN also attract interest: these are covalently linked constructs in which the isothiocyanate fragment of SFN is directly attached to the carboxylic group of classical NSAIDs, allowing the resulting compound to simultaneously potently and selectively inhibit COX-2, retain the anti-inflammatory activity of the original NSAID, and release protective H2S in tissues (Table 4) [110].

3.5. Inhibitors of H2S-Synthesizing Enzymes

Significant progress in modulating endogenous H2S in neurotrauma is associated with the use of inhibitors of its key biosynthetic enzymes: CBS, CSE, and 3-MST. However, in the majority of preclinical neurotrauma models, pharmacological suppression of H2S production predominantly exerts negative effects, exacerbating secondary injury, brain edema, cognitive deficits, and other damage [111]. Nevertheless, in conditions characterized by cytotoxic H2S concentrations, the use of these inhibitors opens new therapeutic prospects for treating various pathological states, including those associated with traumatic injury to the nervous system [112].

AOAA, an effective inhibitor of both the malate–aspartate shuttle (MAS) and CBS, reduced lipopolysaccharide-induced neuroinflammatory responses by suppressing reactive microglial activation and downregulating iNOS, COX-2, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α expression both in vivo and in vitro. This effect was associated with a decrease in the cytosolic NAD+/NADH ratio and reduced STAT3 phosphorylation [113]. In a model of hypoxic–ischemic brain injury, AOAA inhibited L-cysteine-dependent neuroprotection by partially decreasing miR-9-5p and CBS expression and increasing pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and CXCL11 [114]. Likewise, in a cerebral ischemia/reperfusion model, AOAA blocked the neuroprotective effects of total rhododendron flavones (TFR), which act by inhibiting reactive astrogliosis and the rhoa/rho-associated protein kinase (RhoA/ROCK) signaling pathway [115]. Under conditions of retinal oxidative stress, AOAA did not affect the neuroprotective action of cannabinoids, whereas the 3-MST inhibitor α-ketobutyric acid abolished this effect [116]. It has been reported that AOAA completely suppressed brain H2S oscillations induced by spreading depolarization (SD) [117]. AOAA also reduced H2S production in the hypothalamus, thereby increasing arterial pressure and sympathetic activity of the urinary system in paroxysmal sympathetic hyperactivity [38]. In our own studies, AOAA administration exacerbated neuronal and glial cell death following TBI and upregulated proapoptotic proteins such as p53 [21], iNOS, and APP (Figure 5, Table 5) [20].

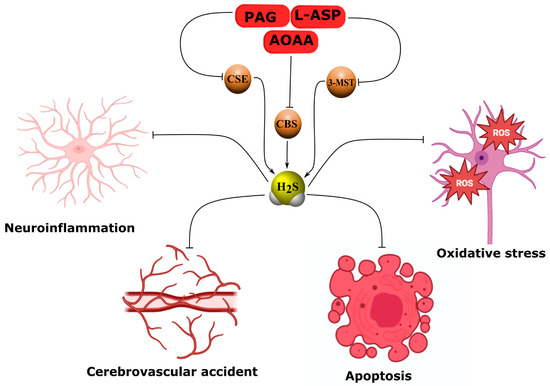

Figure 5.

Neuropathological effects of H2S synthesis inhibitors. Inhibitors of H2S synthesis, including AOAA, PAG, oxamic hydrazide 1, L-aspartic acid, benserazide, and aurintricarboxylic acid, induce neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis, and cerebrovascular spasm by blocking H2S production. AOAA, inhibiting CBS and MAS, reduces NAD+/NADH, STAT3, miR-9-5p, enhances expression of iNOS, COX2, TNF-α, IL-1β, CXCL11, p53, APP, reactive astrogliosis, and sympathetic activity, worsening neuroprotection in TBI, I/R, and hypoxia. PAG, blocking CSE, abolishes the effects of octreotide and remote preconditioning, reducing Nrf2, GSH, the KATP/BK channels, and vasodilation, while increasing oxidative stress and TNF-α. L-aspartic acid and oxamic hydrazide 1 suppress 3-MST and CSE, impairing vasodilation via RhoA-ROCK. Benserazide and aurintricarboxylic acid inhibit CBS and CSE, exacerbating pathological processes. Arrows with pointed ends indicate activation, while blunt ends indicate inhibition.

Table 5.

Effects of inhibitors of endogenous H2S-synthesizing enzymes on the course of experimental neurotrauma and nervous system ischemia. Arrows ↑ and ↓ denote increase and decrease, respectively. Abbreviations. Main active substance: H2S—hydrogen sulfide. Inhibitors of H2S-synthesizing enzymes: AOAA—aminooxyacetic acid; PAG—propargylglycine; L-ASP—L-asparagine; benserazide—selective CBS inhibitor; NSC4056—aurintricarboxylic acid; oximic hydrazide 1—first highly selective membrane-permeable CSE inhibitor. H2S-synthesizing enzymes: CBS—cystathionine-β-synthase; CSE—cystathionine-γ-lyase; 3-MST—3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase. Other enzymes and cofactors: PLP—pyridoxal-5′-phosphate; MGL—methionine-γ-lyase; ALT—alanine aminotransferase; SIRT1—sirtuin 1. Injury models and conditions: TBI—traumatic brain injury; HI—hypoxic–ischemic brain injury; I/R—ischemia/reperfusion; MCAO—middle cerebral artery occlusion; OGD/R—oxygen-glucose deprivation/reoxygenation; SD—spreading depolarization; GBM—glioblastoma; IDHwt—wild-type isocitrate dehydrogenase; IDH1mut—mutant isocitrate dehydrogenase 1. Key signaling pathways and molecules: Nrf2—nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; p-STAT3—phosphorylated STAT3; NAD+/NADH—oxidized/reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; RhoA/ROCK—RhoA-associated kinase; eNOS—endothelial NO synthase; NO—nitric oxide; sGC—soluble guanylate cyclase; HIF-1α—hypoxia-inducible factor 1α; VEGF—vascular endothelial growth factor. Inflammatory markers: iNOS—inducible nitric oxide synthase; COX-2—cyclooxygenase-2; TNF-α—tumor necrosis factor alpha; IL-1β—interleukin-1β; IL-6—interleukin-6; CXCL11—C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 11. Antioxidant defense and oxidative stress: GSH—reduced glutathione; ROS—reactive oxygen species. Damage marker proteins: p53—tumor suppressor p53; APP—amyloid precursor protein. Cell lines: BV2—mouse microglial cell line; HEK293T—human embryonic kidney cells; COS-7—African green monkey kidney cells; RAW264.7—mouse macrophages; KYSE450—human esophageal cancer; A549—human lung adenocarcinoma; HCT8—human colorectal cancer; NCH644; NCH421k; NCH1681; NCH551b; NCH612—patient-derived glioma lines. Other: LPS—lipopolysaccharide; miR-9-5p—microRNA-9-5p; MAP—mean arterial pressure; K_ATP channels—ATP-sensitive potassium channels; BK channels—large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels.

Similarly, propargylglycine (PAG), a selective inhibitor of CSE, abolished the neuroprotective effects of octreotide by inhibiting H2S generation and Nrf2 expression while increasing TNF-α levels in TBI [118]. In a vascular dementia model, both PAG and AOAA markedly suppressed the effects of remote preconditioning by reducing H2S, CBS, CSE, and Nrf2 expression and enhancing oxidative damage in nervous tissue [119]. PAG decreased H2S generation in cerebral vascular endothelium and reduced arteriole vasodilation, disrupting H2S-dependent activation of ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) and large-conductance calcium-activated potassium (BK) channels [120]. Moreover, PAG rendered astrocytes carrying IDH1 mutations more vulnerable to cysteine deficiency, increasing oxidative stress and depleting GSH [121]. In cerebral arterioles, PAG significantly inhibited potassium-induced vasoconstriction through signaling pathways involving both H2S and eNOS/soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) (Figure 5, Table 5) [122].