Neurovascular Dysfunction and Glymphatic Impairment: An Unexplored Therapeutic Frontier in Neurodegeneration

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology of Literature Search

3. Pathophysiology of Neurovascular Unit Dysfunction

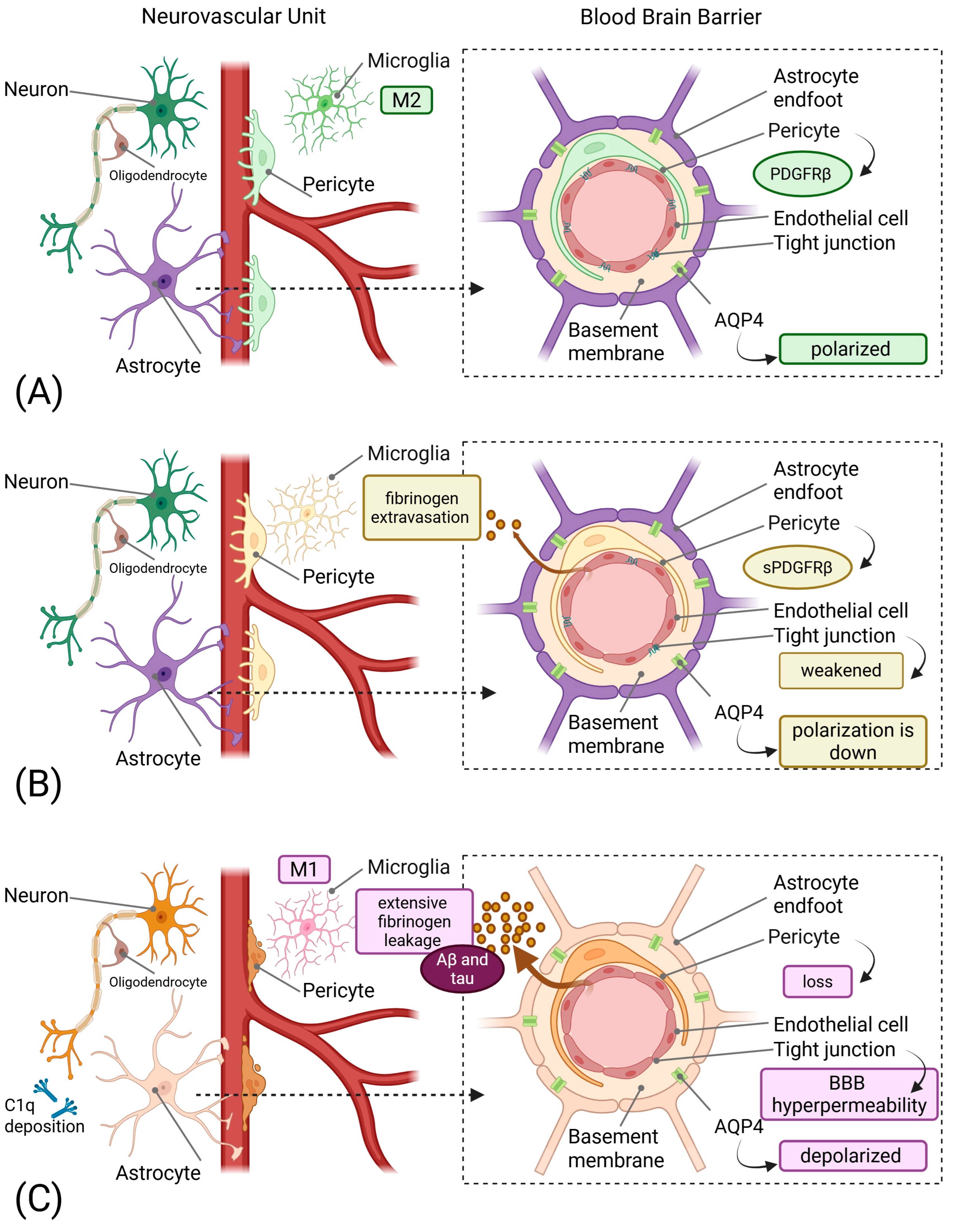

3.1. From Components to Pericyte-Driven Pathology

3.2. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor as a Dual-Acting Therapeutic Target

3.3. The Glymphatic-Lymphatic Interface

3.4. Aquaporin-4 Polarity Loss: A Therapeutic Target

3.5. Meningeal Lymphatic Vessels: A Novel Drainage Target

4. Neuroinflammation and the Tripartite Synapse

4.1. Microglial Dysfunction and Synaptic Clearance

4.2. Complement-Mediated Synaptic Pruning

4.3. MicroRNA-Mediated Inflammation Control

5. Discussion

5.1. Inadequacy of Protein-Centric Approaches

5.2. Blood–Brain Barrier Permeability as an Overlooked Target

5.3. Inflammation-Mediated Neurovascular Damage

5.4. Precision Medicine Approaches to Neurovascular Dysfunction

| Therapeutic Target | Mechanism of Action | Preclinical Evidence | Proposed Therapeutic Approach | Potential Benefits | Challenges/Considerations | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDGF-BB/PDGFRβ Signaling | Maintains pericyte survival and BBB integrity via ERK and PI3K pathways | PDGFRβ ± mice show accelerated BBB breakdown and neurodegeneration; restoration protects against vascular damage | PDGF-BB supplementation; prevention of PDGFRβ shedding; APOE4-targeted interventions | Preserves pericyte coverage; maintains BBB integrity; prevents early vascular damage | Timing critical; systemic effects; optimal dosing unclear | [35,78] |

| VEGF-C/VEGFR-3 Signaling | Enhances meningeal lymphatic vessel function and promotes lymphangiogenesis for brain waste clearance | VEGF-C administration in AD mice increases mLV diameter, reduces CSF and brain Aβ, restores cognition | Recombinant VEGF-C (intrathecal or systemic); VEGFR-3 agonists; transcranial radiofrequency stimulation | Enhances protein clearance; reduces tau and Aβ accumulation; improves cognitive function | Delivery route optimization; potential angiogenic effects; dose-finding needed | [30,31] |

| AQP4 Polarization Restoration | Restores proper localization of AQP4 at perivascular astrocytic endfeet to enhance glymphatic flow | Exercise and calmodulin inhibition restore AQP4 polarization and improve Aβ clearance in AD models | High-intensity interval training; aerobic exercise; calmodulin inhibitors (trifluoperazine); pharmacological AQP4 modulators | Enhances glymphatic clearance; reduces protein accumulation; improves waste removal | Exercise compliance; pharmacological specificity; avoiding edema | [79,80,81] |

| Complement C1q Inhibition | Blocks initiation of classical complement cascade; prevents C1q tagging of synapses for elimination | C1q deletion or neutralizing antibodies protect synapses and improve cognition in AD mouse models | Anti-C1q monoclonal antibodies; C1q inhibitor peptides; selective C1q blockers | Prevents excessive synaptic pruning; preserves cognitive function; reduces neuroinflammation | Balancing physiological vs. pathological complement; immune surveillance concerns | [19,82,83] |

| Complement C3 Modulation | Prevents C3 cleavage and iC3b-mediated synaptic tagging; blocks complement amplification | C3 deficiency prevents age-related synapse loss and improves LTP in aged mice; protects against AD pathology | C3 inhibitors (compstatin analogs); C3 convertase inhibitors | Reduces synaptic loss; improves cognitive outcomes; maintains neuronal networks | Timing of intervention; systemic complement functions; infection risk | [18,84,85] |

| CR3 (CD11b/CD18) Blockade | Prevents microglial engulfment of iC3b-tagged synapses | CR3 knockout mice protected from Aβ-induced synapse loss; reduced microglial phagocytosis | CR3 antagonists; CD11b-blocking antibodies; small molecule inhibitors | Preserves synapses; reduces microglial-mediated damage; maintains circuit function | Microglial function preservation; specificity for pathological pruning | [19,20] |

| C5aR1 (C5a Receptor) Antagonism | Blocks C5a-mediated microglial activation; reduces excessive synaptic pruning | C5aR1 deletion or PMX205 treatment reduces synapse loss and improves cognition in multiple AD models | PMX205 or PMX53 (C5aR1 antagonists); small molecule C5aR1 inhibitors | Reduces synaptic loss; improves behavior; modulates neuroinflammation without blocking upstream complement | Better therapeutic window than C1q/C3 inhibition; preserves beneficial complement functions | [86,87,88] |

| miR-124 Replacement Therapy | Restores anti-inflammatory signaling; promotes M2 microglial polarization; inhibits inflammatory mediators | miR-124 overexpression reduces neuroinflammation and promotes neuroprotection in injury models | Lipid nanoparticle-encapsulated miR-124; viral vector delivery; synthetic miR-124 mimics | Shifts microglia to anti-inflammatory phenotype; reduces TNF-α; increases IL-10 | Delivery to CNS; off-target effects; stability of miRNA therapeutics | [27] |

| miR-155 Inhibition | Reduces pro-inflammatory signaling; decreases NF-κB activation; attenuates M1 microglial responses | miR-155 deletion improves outcomes in spinal cord injury and reduces neuroinflammation in MS models | AntagomiR-155; locked nucleic acid (LNA) anti-miR-155; GapmeR inhibitors | Reduces neuroinflammation; improves functional recovery; modulates TLR signaling | Delivery challenges; dosing optimization; potential immune effects | [29,89] |

| Meningeal Lymphatic Enhancement | Physical or pharmacological enhancement of mLV structure and function | Exercise enhances mLV flow; VEGF-C expands mLV diameter and improves clearance in aged mice | Aerobic exercise protocols; VEGF-C administration; minimally invasive mLV stimulation | Enhances brain-to-cervical lymph node drainage; improves clearance of proteins and immune cells | Age-related mLV degeneration; non-invasive enhancement methods needed | [30,90] |

| TREM2 Modulation | Regulates microglial phagocytic capacity and metabolic state; modulates complement-mediated pruning | TREM2 deficiency alters microglial response to plaques; affects synaptic engulfment | TREM2 agonistic antibodies; TREM2 activity enhancers (context-dependent) | Modulates microglial function; may enhance beneficial phagocytosis while reducing excessive pruning | Complex role (protective vs. detrimental); stage-dependent effects | [91,92,93] |

| CD200-CD200R Axis Enhancement | Maintains microglial quiescence; promotes M2 polarization; reduces inflammatory activation | CD200-Fc treatment shifts macrophages/microglia from M1 to M2; reduces pro-inflammatory cytokines | CD200-Fc fusion protein; CD200R agonists | Reduces neuroinflammation; promotes neuroprotective microglial phenotype; decreases oxidative stress | Systemic delivery; CNS penetration; long-term safety | [94] |

5.5. Molecular Pathway-Based Therapeutic Targets

5.6. Comparative Therapeutic Efficacy and Intervention Windows

6. Future Directions and Research Priorities

6.1. Current and Planned Clinical Trials

6.2. Neurovascular Unit-Targeted Drug Delivery

6.3. Combination Therapy Approaches

6.4. Translational Challenges and Biomarker Development

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Aβ | Amyloid-β |

| Akt | Protein Kinase B |

| APOE4 | Apolipoprotein Epsilon 4 |

| AQP4 | Aquaporin-4 |

| ARG-1 | Arginase 1 |

| BBB | Blood–Brain Barrier |

| C/EBPα | CCAAT/Enhancer-Binding Protein alpha |

| C1q | Complement component 1q |

| C3 | Complement component 3 |

| C5aR1 | C5a Receptor 1 |

| CD200-CD200R | CD200-CD200 Receptor |

| CR3 | Complement Receptor 3 |

| CREB1 | cAMP Response Element Binding Protein 1 |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal Fluid |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-Regulated Kinase |

| GFAP | Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein |

| IL-10 | Interleukin 10 |

| IL-1β | Interleukin 1 beta |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| miR-124 | microRNA 124 |

| miR-155 | microRNA 155 |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor kappa B |

| PDGF-BB | Platelet-Derived Growth Factor-BB |

| PDGFRβ | Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptor-β |

| PI3K | Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase |

| PU.1 | PU.1 (also known as SPI1) |

| Qalb | CSF/Plasma Albumin Ratio |

| Ser276 | Serine at position 276 |

| sPDGFRβ | soluble Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptor-β |

| TLR | Toll-Like Receptor |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-α |

| TREM2 | Triggering Receptor Expressed on Myeloid cells 2 |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

References

- Espay, A.J. Models of Precision Medicine for Neurodegeneration. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2023, 192, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-R.; Guo, Y.; Du, J.; Ren, P.; Wu, B.-S.; Feng, J.-F.; Cheng, W.; Yu, J.-T. Glymphatic System Dysfunction Predicts Amyloid Deposition, Neurodegeneration, and Clinical Progression in Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2024, 20, 3251–3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, M.D.; Sagare, A.P.; Zlokovic, B.V. Blood-Brain Barrier Breakdown in Alzheimer Disease and Other Neurodegenerative Disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2018, 14, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Dai, Y.; Hu, C.; Lin, Z.; Wang, S.; Yang, J.; Zeng, L.; Li, S.; Li, W. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of the Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Fluids Barriers CNS 2024, 21, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Ji, C.; Shao, A. Neurovascular Unit Dysfunction and Neurodegenerative Disorders. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kugler, E.C.; Greenwood, J.; MacDonald, R.B. The “Neuro-Glial-Vascular” Unit: The Role of Glia in Neurovascular Unit Formation and Dysfunction. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 732820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wu, H.; Xu, W.; Pan, Y.; Gao, S.; Dong, X.; Zhang, J.H.; Shao, A. Persistent Neurovascular Unit Dysfunction: Pathophysiological Substrate and Trigger for Late-Onset Neurodegeneration After Traumatic Brain Injury. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Vliet, E.A.; Marchi, N. Neurovascular Unit Dysfunction as a Mechanism of Seizures and Epilepsy during Aging. Epilepsia 2022, 63, 1297–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najjar, S.; Pearlman, D.M.; Devinsky, O.; Najjar, A.; Zagzag, D. Neurovascular Unit Dysfunction with Blood-Brain Barrier Hyperpermeability Contributes to Major Depressive Disorder: A Review of Clinical and Experimental Evidence. J. Neuroinflamm. 2013, 10, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najjar, S.; Pahlajani, S.; De Sanctis, V.; Stern, J.N.H.; Najjar, A.; Chong, D. Neurovascular Unit Dysfunction and Blood-Brain Barrier Hyperpermeability Contribute to Schizophrenia Neurobiology: A Theoretical Integration of Clinical and Experimental Evidence. Front. Psychiatry 2017, 8, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Rojas, L.O.; Pacheco-Herrero, M.; Martínez-Gómez, P.A.; Campa-Córdoba, B.B.; Apátiga-Pérez, R.; Villegas-Rojas, M.M.; Harrington, C.R.; de la Cruz, F.; Garcés-Ramírez, L.; Luna-Muñoz, J. The Neurovascular Unit Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miners, J.S.; Kehoe, P.G.; Love, S.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K. CSF Evidence of Pericyte Damage in Alzheimer’s Disease Is Associated with Markers of Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction and Disease Pathology. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2019, 11, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nation, D.A.; Sweeney, M.D.; Montagne, A.; Sagare, A.P.; D’Orazio, L.M.; Pachicano, M.; Sepehrband, F.; Nelson, A.R.; Buennagel, D.P.; Harrington, M.G.; et al. Blood-Brain Barrier Breakdown Is an Early Biomarker of Human Cognitive Dysfunction. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeney, M.D.; Sagare, A.P.; Pachicano, M.; Harrington, M.G.; Joe, E.; Chui, H.C.; Schneider, L.S.; Montagne, A.; Ringman, J.M.; Fagan, A.M.; et al. A Novel Sensitive Assay for Detection of a Biomarker of Pericyte Injury in Cerebrospinal Fluid. Alzheimers Dement. 2020, 16, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrillon, A.; Ashton, N.J.; Bouaziz-Amar, E.; Mouton-Liger, F.; Cognat, E.; Dumurgier, J.; Lilamand, M.; Karikari, T.K.; Prevot, V.; Zetterberg, H.; et al. Dissection of Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction through CSF PDGFRβ and Amyloid, Tau, Neuroinflammation, and Synaptic CSF Biomarkers in Neurodegenerative Disorders. EBioMedicine 2025, 115, 105694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montagne, A.; Barnes, S.R.; Sweeney, M.D.; Halliday, M.R.; Sagare, A.P.; Zhao, Z.; Toga, A.W.; Jacobs, R.E.; Liu, C.Y.; Amezcua, L.; et al. Blood-Brain Barrier Breakdown in the Aging Human Hippocampus. Neuron 2015, 85, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, A.H.; Madison, D.V.; Mateos, J.M.; Fraser, D.A.; Lovelett, E.A.; Coutellier, L.; Kim, L.; Tsai, H.-H.; Huang, E.J.; Rowitch, D.H.; et al. A Dramatic Increase of C1q Protein in the CNS during Normal Aging. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 13460–13474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Colodner, K.J.; Matousek, S.B.; Merry, K.; Hong, S.; Kenison, J.E.; Frost, J.L.; Le, K.X.; Li, S.; Dodart, J.-C.; et al. Complement C3-Deficient Mice Fail to Display Age-Related Hippocampal Decline. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 13029–13042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Beja-Glasser, V.F.; Nfonoyim, B.M.; Frouin, A.; Li, S.; Ramakrishnan, S.; Merry, K.M.; Shi, Q.; Rosenthal, A.; Barres, B.A.; et al. Complement and Microglia Mediate Early Synapse Loss in Alzheimer Mouse Models. Science 2016, 352, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presumey, J.; Bialas, A.R.; Carroll, M.C. Complement System in Neural Synapse Elimination in Development and Disease. Adv. Immunol. 2017, 135, 53–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliff, J.J.; Wang, M.; Liao, Y.; Plogg, B.A.; Peng, W.; Gundersen, G.A.; Benveniste, H.; Vates, G.E.; Deane, R.; Goldman, S.A.; et al. A Paravascular Pathway Facilitates CSF Flow through the Brain Parenchyma and the Clearance of Interstitial Solutes, Including Amyloid β. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 147ra111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.J.; Yao, X.; Dix, J.A.; Jin, B.-J.; Verkman, A.S. Test of the “glymphatic” Hypothesis Demonstrates Diffusive and Aquaporin-4-Independent Solute Transport in Rodent Brain Parenchyma. Elife 2017, 6, e27679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestre, H.; Hablitz, L.M.; Xavier, A.L.; Feng, W.; Zou, W.; Pu, T.; Monai, H.; Murlidharan, G.; Castellanos Rivera, R.M.; Simon, M.J.; et al. Aquaporin-4-Dependent Glymphatic Solute Transport in the Rodent Brain. Elife 2018, 7, e40070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig-Schapiro, R.; Perrin, R.J.; Roe, C.M.; Xiong, C.; Carter, D.; Cairns, N.J.; Mintun, M.A.; Peskind, E.R.; Li, G.; Galasko, D.R.; et al. YKL-40: A Novel Prognostic Fluid Biomarker for Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease. Biol. Psychiatry 2010, 68, 903–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janelidze, S.; Mattsson, N.; Stomrud, E.; Lindberg, O.; Palmqvist, S.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; Hansson, O. CSF Biomarkers of Neuroinflammation and Cerebrovascular Dysfunction in Early Alzheimer Disease. Neurology 2018, 91, e867–e877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedet, A.L.; Milà-Alomà, M.; Vrillon, A.; Ashton, N.J.; Pascoal, T.A.; Lussier, F.; Karikari, T.K.; Hourregue, C.; Cognat, E.; Dumurgier, J.; et al. Differences Between Plasma and Cerebrospinal Fluid Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein Levels Across the Alzheimer Disease Continuum. JAMA Neurol. 2021, 78, 1471–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponomarev, E.D.; Veremeyko, T.; Barteneva, N.; Krichevsky, A.M.; Weiner, H.L. MicroRNA-124 Promotes Microglia Quiescence and Suppresses EAE by Deactivating Macrophages via the C/EBP-α-PU.1 Pathway. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guedes, J.R.; Custódia, C.M.; Silva, R.J.; de Almeida, L.P.; Pedroso de Lima, M.C.; Cardoso, A.L. Early miR-155 Upregulation Contributes to Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s Disease Triple Transgenic Mouse Model. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 6286–6301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butovsky, O.; Jedrychowski, M.P.; Cialic, R.; Krasemann, S.; Murugaiyan, G.; Fanek, Z.; Greco, D.J.; Wu, P.M.; Doykan, C.E.; Kiner, O.; et al. Targeting miR-155 Restores Abnormal Microglia and Attenuates Disease in SOD1 Mice. Ann. Neurol. 2015, 77, 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Mesquita, S.; Louveau, A.; Vaccari, A.; Smirnov, I.; Cornelison, R.C.; Kingsmore, K.M.; Contarino, C.; Onengut-Gumuscu, S.; Farber, E.; Raper, D.; et al. Functional Aspects of Meningeal Lymphatics in Ageing and Alzheimer’s Disease. Nature 2018, 560, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.H.; Cho, H.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, S.H.; Ham, J.-S.; Park, I.; Suh, S.H.; Hong, S.P.; Song, J.-H.; Hong, Y.-K.; et al. Meningeal Lymphatic Vessels at the Skull Base Drain Cerebrospinal Fluid. Nature 2019, 572, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, L.S.; Foster, C.G.; Courtney, J.-M.; King, N.E.; Howells, D.W.; Sutherland, B.A. Pericytes and Neurovascular Function in the Healthy and Diseased Brain. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2019, 13, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Fan, H. Pericyte Loss in Diseases. Cells 2023, 12, 1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preis, L.; Villringer, K.; Brosseron, F.; Düzel, E.; Jessen, F.; Petzold, G.C.; Ramirez, A.; Spottke, A.; Fiebach, J.B.; Peters, O. Assessing Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction and Its Association with Alzheimer’s Pathology, Cognitive Impairment and Neuroinflammation. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2024, 16, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, L.C.D.; Highet, B.; Jansson, D.; Wu, J.; Rustenhoven, J.; Aalderink, M.; Tan, A.; Li, S.; Johnson, R.; Coppieters, N.; et al. Characterisation of PDGF-BB:PDGFRβ Signalling Pathways in Human Brain Pericytes: Evidence of Disruption in Alzheimer’s Disease. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Xu, G.; Zhu, R.; Yuan, J.; Ishii, Y.; Hamashima, T.; Matsushima, T.; Yamamoto, S.; Takatsuru, Y.; Nabekura, J.; et al. PDGFR-β Restores Blood-Brain Barrier Functions in a Mouse Model of Focal Cerebral Ischemia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2019, 39, 1501–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cercy, S.P. Pericytes and the Neurovascular Unit: The Critical Nexus of Alzheimer Disease Pathogenesis? Explor. Res. Hypothesis Med. 2021, 6, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Guo, W.; Gong, M.; Zhu, L.; Cao, T.; Huang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Chen, J.; Yang, C.; Zhang, S.; et al. Pericyte Loss: A Key Factor Inducing Brain Aβ40 Accumulation and Neuronal Degeneration in Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy. Exp. Brain Res. 2025, 243, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Góra-Kupilas, K.; Jośko, J. The Neuroprotective Function of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF). Folia Neuropathol. 2005, 43, 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Arendash, G.W.; Lin, X.; Cao, C. Enhanced Brain Clearance of Tau and Amyloid-β in Alzheimer’s Disease Patients by Transcranial Radiofrequency Wave Treatment: A Central Role of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF). J. Alzheimers Dis. 2024, 100, S223–S241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Xia, R.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, L.; Gao, F. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factors Enhance the Permeability of the Mouse Blood-Brain Barrier. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Rhodes, P.G.; Bhatt, A.J. Neuroprotective Effects of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Following Hypoxic Ischemic Brain Injury in Neonatal Rats. Pediatr. Res. 2008, 64, 370–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.-T.; Zhang, P.; Gao, Y.; Li, C.-L.; Wang, H.-J.; Chen, L.-C.; Feng, Y.; Li, R.-Y.; Li, Y.-L.; Jiang, C.-L. Early VEGF Inhibition Attenuates Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption in Ischemic Rat Brains by Regulating the Expression of MMPs. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 15, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasoff-Conway, J.M.; Carare, R.O.; Osorio, R.S.; Glodzik, L.; Butler, T.; Fieremans, E.; Axel, L.; Rusinek, H.; Nicholson, C.; Zlokovic, B.V.; et al. Clearance Systems in the Brain-Implications for Alzheimer Disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2015, 11, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomolka, R.S.; Hablitz, L.M.; Mestre, H.; Giannetto, M.; Du, T.; Hauglund, N.L.; Xie, L.; Peng, W.; Martinez, P.M.; Nedergaard, M.; et al. Loss of Aquaporin-4 Results in Glymphatic System Dysfunction via Brain-Wide Interstitial Fluid Stagnation. Elife 2023, 12, e82232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ota, M.; Sato, N.; Nakaya, M.; Shigemoto, Y.; Kimura, Y.; Chiba, E.; Yokoi, Y.; Tsukamoto, T.; Matsuda, H. Relationships Between the Deposition of Amyloid-β and Tau Protein and Glymphatic System Activity in Alzheimer’s Disease: Diffusion Tensor Image Study. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2022, 90, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, I.F.; Ismail, O.; Machhada, A.; Colgan, N.; Ohene, Y.; Nahavandi, P.; Ahmed, Z.; Fisher, A.; Meftah, S.; Murray, T.K.; et al. Impaired Glymphatic Function and Clearance of Tau in an Alzheimer’s Disease Model. Brain 2020, 143, 2576–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazzard, I.; Batiste, M.; Luo, T.; Cheung, C.; Lui, F. Impaired Glymphatic Clearance Is an Important Cause of Alzheimer’s Disease. Explor. Neuroprot. Ther. 2024, 4, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdock, M.H.; Yang, C.-Y.; Sun, N.; Pao, P.-C.; Blanco-Duque, C.; Kahn, M.C.; Kim, T.; Lavoie, N.S.; Victor, M.B.; Islam, M.R.; et al. Multisensory Gamma Stimulation Promotes Glymphatic Clearance of Amyloid. Nature 2024, 627, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Liu, H.; Wang, X.; Lin, H.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, L.; Huang, S.; Chen, L. Aerobic Exercise Improves Clearance of Amyloid-β via the Glymphatic System in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Brain Res. Bull. 2025, 222, 111263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qianqian, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, H.; Ye, Y.; Yu, C. Factors Affecting Aquaporin-4 and Its Regulatory Mechanisms in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurol. Asia 2025, 30, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patabendige, A.; Chen, R. Astrocytic Aquaporin 4 Subcellular Translocation as a Therapeutic Target for Cytotoxic Edema in Ischemic Stroke. Neural Regen. Res. 2022, 17, 2666–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Lin, W.; Zheng, M.; Liu, Q.; He, B.; Luo, C.; Lu, X.; Pei, Z.; Su, H.; Yao, X. Alterations in AQP4 Expression and Polarization in the Course of Motor Neuron Degeneration in SOD1G93A Mice. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 16, 1739–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, S.; Wu, C.; Zou, P.; Deng, Q.; Chen, Z.; Li, M.; Zhu, L.; Li, F.; Liu, T.C.-Y.; Duan, R.; et al. High-Intensity Interval Training Ameliorates Alzheimer’s Disease-like Pathology by Regulating Astrocyte Phenotype-Associated AQP4 Polarization. Theranostics 2023, 13, 3434–3450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Cao, Y.; Tang, X.; Huang, J.; Cai, L.; Zhou, L. The Meningeal Lymphatic Vessels and the Glymphatic System: Potential Therapeutic Targets in Neurological Disorders. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2022, 42, 1364–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Niu, Y.; Li, Y.; Xia, C.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Y.; Feng, H. Meningeal Lymphatic Drainage: Novel Insights into Central Nervous System Disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boisserand, L.S.B.; Geraldo, L.H.; Bouchart, J.; El Kamouh, M.-R.; Lee, S.; Sanganahalli, B.G.; Spajer, M.; Zhang, S.; Lee, S.; Parent, M.; et al. VEGF-C Prophylaxis Favors Lymphatic Drainage and Modulates Neuroinflammation in a Stroke Model. J. Exp. Med. 2024, 221, e20221983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wu, C.; Ding, Q.; Liu, X.-Y.; Zhang, N.; Shen, J.-H.; Ou, Z.-T.; Lin, T.; Zhu, H.-X.; Lan, Y.; et al. Age-Related Changes in Meningeal Lymphatic Function Are Closely Associated with Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor-C Expression. Brain Res. 2024, 1833, 148868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lull, M.E.; Block, M.L. Microglial Activation and Chronic Neurodegeneration. Neurotherapeutics 2010, 7, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Wang, H.; Yin, Y. Microglia Polarization From M1 to M2 in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 815347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asl, E.R.; Hosseini, S.E.; Tahmasebi, F.; Bolandi, N.; Barati, S. MiR-124 and MiR-155 as Therapeutic Targets in Microglia-Mediated Inflammation in Multiple Sclerosis. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 2025, 45, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.J.; Suk, K. Pharmacological Modulation of Functional Phenotypes of Microglia in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2017, 9, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Arboledas, A.; Acharya, M.M.; Tenner, A.J. The Role of Complement in Synaptic Pruning and Neurodegeneration. Immunotargets Ther. 2021, 10, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Györffy, B.A.; Kun, J.; Török, G.; Bulyáki, É.; Borhegyi, Z.; Gulyássy, P.; Kis, V.; Szocsics, P.; Micsonai, A.; Matkó, J.; et al. Local Apoptotic-like Mechanisms Underlie Complement-Mediated Synaptic Pruning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 6303–6308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Jiang, M.; Chen, Z.; Li, C.; Yin, X.; Zhang, X.; Wu, M. The Role of the Complement System in Synaptic Pruning after Stroke. Aging Dis. 2024, 16, 1452–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, K. Emerging Roles of Complement Protein C1q in Neurodegeneration. Aging Dis. 2019, 10, 652–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Q.; Wang, M.; Yin, Y.; Tang, Y. The Specific Mechanism of TREM2 Regulation of Synaptic Clearance in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 845897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; He, Z.; Wang, J. MicroRNA-124: A Key Player in Microglia-Mediated Inflammation in Neurological Diseases. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2021, 15, 771898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudet, A.D.; Fonken, L.K.; Watkins, L.R.; Nelson, R.J.; Popovich, P.G. MicroRNAs: Roles in Regulating Neuroinflammation. Neuroscientist 2018, 24, 221–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, Q.; Gui, H.; Xu, D.-P.; Yang, Y.-L.; Su, D.-F.; Liu, X. MicroRNA-124 Mediates the Cholinergic Anti-Inflammatory Action through Inhibiting the Production of pro-Inflammatory Cytokines. Cell Res. 2013, 23, 1270–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, E.E.; Frigy, A.; Szász, J.A.; Horváth, E. Neuroinflammation and Microglia/Macrophage Phenotype Modulate the Molecular Background of Post-Stroke Depression: A Literature Review. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 20, 2510–2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, Y.R.; Chiam, K.-H. Discovery of Plasma Biomarkers Related to Blood-Brain Barrier Dysregulation in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Bioinform. 2024, 4, 1463001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Mu, B.-R.; Ran, Z.; Zhu, T.; Huang, X.; Yang, X.; Wang, D.-M.; Ma, Q.-H.; Lu, M.-H. Pericytes in Alzheimer’s Disease: Key Players and Therapeutic Targets. Exp. Neurol. 2024, 379, 114825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- İş, Ö.; Wang, X.; Reddy, J.S.; Min, Y.; Yilmaz, E.; Bhattarai, P.; Patel, T.; Bergman, J.; Quicksall, Z.; Heckman, M.G.; et al. Gliovascular Transcriptional Perturbations in Alzheimer’s Disease Reveal Molecular Mechanisms of Blood Brain Barrier Dysfunction. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Li, X.-Q.; Deng, J.; Ye, Q.-B.; Li, D.; Ma, Y.; Wu, Y.-Y.; Hu, Y.; He, X.-F.; Wen, J.; et al. Modulating the Polarization Phenotype of Microglia—A Valuable Strategy for Central Nervous System Diseases. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 93, 102160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niotis, K.; Janney, C.; Helfman, S.; Hristov, H.; Clute-Reinig, N.; Angerbauer, D.; Saperia, C.; Murray, S.; Westine, J.; Seifan, A.; et al. A Blood Biomarker-Guided Precision Medicine Approach for Individualized Neurodegenerative Disease Risk Reduction and Treatment: The Future of Preventive Neurology? (P7-3.016). Neurology 2025, 104, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, N.J.; Benedet, A.L.; Di Molfetta, G.; Pola, I.; Anastasi, F.; Fernández-Lebrero, A.; Puig-Pijoan, A.; Keshavan, A.; Schott, J.; Tan, K.; et al. Biomarker Discovery in Alzheimer’s and Neurodegenerative Diseases Using Nucleic Acid-Linked Immuno-Sandwich Assay. medRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armulik, A.; Genové, G.; Mäe, M.; Nisancioglu, M.H.; Wallgard, E.; Niaudet, C.; He, L.; Norlin, J.; Lindblom, P.; Strittmatter, K.; et al. Pericytes Regulate the Blood-Brain Barrier. Nature 2010, 468, 557–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitchen, P.; Day, R.E.; Taylor, L.H.J.; Salman, M.M.; Bill, R.M.; Conner, M.T.; Conner, A.C. Identification and Molecular Mechanisms of the Rapid Tonicity-Induced Relocalization of the Aquaporin 4 Channel. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 16873–16881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Ding, F.; Deng, S.; Guo, X.; Wang, W.; Iliff, J.J.; Nedergaard, M. Focal Solute Trapping and Global Glymphatic Pathway Impairment in a Murine Model of Multiple Microinfarcts. J. Neurosci. 2017, 37, 2870–2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.-B.; Wang, X.-X.; Xia, D.-H.; Liu, H.; Tian, H.-Y.; Fu, Y.; Chen, Y.-K.; Qin, C.; Wang, J.-Q.; Xiang, Z.; et al. Impaired Meningeal Lymphatic Drainage in Patients with Idiopathic Parkinson’s Disease. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, M.I.; Chu, S.-H.; Hernandez, M.X.; Fang, M.J.; Modarresi, L.; Selvan, P.; MacGregor, G.R.; Tenner, A.J. Cell-Specific Deletion of C1qa Identifies Microglia as the Dominant Source of C1q in Mouse Brain. J. Neuroinflamm. 2017, 14, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansita, J.A.; Mease, K.M.; Qiu, H.; Yednock, T.; Sankaranarayanan, S.; Kramer, S. Nonclinical Development of ANX005: A Humanized Anti-C1q Antibody for Treatment of Autoimmune and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Toxicol. 2017, 36, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyss-Coray, T.; Yan, F.; Lin, A.H.-T.; Lambris, J.D.; Alexander, J.J.; Quigg, R.J.; Masliah, E. Prominent Neurodegeneration and Increased Plaque Formation in Complement-Inhibited Alzheimer’s Mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 10837–10842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litvinchuk, A.; Wan, Y.-W.; Swartzlander, D.B.; Chen, F.; Cole, A.; Propson, N.E.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, B.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, H. Complement C3aR Inactivation Attenuates Tau Pathology and Reverses an Immune Network Deregulated in Tauopathy Models and Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuron 2018, 100, 1337–1353.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, M.I.; Ager, R.R.; Chu, S.-H.; Yazan, O.; Sanderson, S.D.; LaFerla, F.M.; Taylor, S.M.; Woodruff, T.M.; Tenner, A.J. Treatment with a C5aR Antagonist Decreases Pathology and Enhances Behavioral Performance in Murine Models of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Immunol. 2009, 183, 1375–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, M.X.; Jiang, S.; Cole, T.A.; Chu, S.-H.; Fonseca, M.I.; Fang, M.J.; Hohsfield, L.A.; Torres, M.D.; Green, K.N.; Wetsel, R.A.; et al. Prevention of C5aR1 Signaling Delays Microglial Inflammatory Polarization, Favors Clearance Pathways and Suppresses Cognitive Loss. Mol. Neurodegener. 2017, 12, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Propson, N.E.; Roy, E.R.; Litvinchuk, A.; Köhl, J.; Zheng, H. Endothelial C3a Receptor Mediates Vascular Inflammation and Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability during Aging. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, 140966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Ramirez, M.A.; Wu, D.; Pryce, G.; Simpson, J.E.; Reijerkerk, A.; King-Robson, J.; Kay, O.; de Vries, H.E.; Hirst, M.C.; Sharrack, B.; et al. MicroRNA-155 Negatively Affects Blood-Brain Barrier Function during Neuroinflammation. FASEB J. 2014, 28, 2551–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.; Rayasam, A.; Kijak, J.A.; Choi, Y.H.; Harding, J.S.; Marcus, S.A.; Karpus, W.J.; Sandor, M.; Fabry, Z. Neuroinflammation-Induced Lymphangiogenesis near the Cribriform Plate Contributes to Drainage of CNS-Derived Antigens and Immune Cells. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cella, M.; Mallinson, K.; Ulrich, J.D.; Young, K.L.; Robinette, M.L.; Gilfillan, S.; Krishnan, G.M.; Sudhakar, S.; Zinselmeyer, B.H.; et al. TREM2 Lipid Sensing Sustains the Microglial Response in an Alzheimer’s Disease Model. Cell 2015, 160, 1061–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bemiller, S.M.; McCray, T.J.; Allan, K.; Formica, S.V.; Xu, G.; Wilson, G.; Kokiko-Cochran, O.N.; Crish, S.D.; Lasagna-Reeves, C.A.; Ransohoff, R.M.; et al. TREM2 Deficiency Exacerbates Tau Pathology through Dysregulated Kinase Signaling in a Mouse Model of Tauopathy. Mol. Neurodegener. 2017, 12, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipello, F.; Morini, R.; Corradini, I.; Zerbi, V.; Canzi, A.; Michalski, B.; Erreni, M.; Markicevic, M.; Starvaggi-Cucuzza, C.; Otero, K.; et al. The Microglial Innate Immune Receptor TREM2 Is Required for Synapse Elimination and Normal Brain Connectivity. Immunity 2018, 48, 979–991.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, D.G.; McGeer, P.L. Complement Gene Expression in Human Brain: Comparison between Normal and Alzheimer Disease Cases. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1992, 14, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, S. Therapeutic Approaches to CNS Diseases via the Meningeal Lymphatic and Glymphatic System: Prospects and Challenges. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1467085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negro-Demontel, L.; Maleki, A.F.; Reich, D.S.; Kemper, C. The Complement System in Neurodegenerative and Inflammatory Diseases of the Central Nervous System. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1396520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, N.; Shaheen, A.; Osama, M.; Nashwan, A.J.; Bharmauria, V.; Flouty, O. MicroRNAs Regulation in Parkinson’s Disease, and Their Potential Role as Diagnostic and Therapeutic Targets. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2024, 10, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, M.; Jorgensen, A.L.; Kolamunnage-Dona, R. Biomarker-Guided Adaptive Trial Designs in Phase II and Phase III: A Methodological Review. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imam, F.; Saloner, R.; Vogel, J.W.; Krish, V.; Abdel-Azim, G.; Ali, M.; An, L.; Anastasi, F.; Bennett, D.; Pichet Binette, A.; et al. The Global Neurodegeneration Proteomics Consortium: Biomarker and Drug Target Discovery for Common Neurodegenerative Diseases and Aging. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 2556–2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Sun, J. The Role of the Neurovascular Unit in Vascular Cognitive Impairment: Current Evidence and Future Perspectives. Neurobiol. Dis. 2025, 204, 106772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thalgott, J.H.; Zucker, N.; Deffieux, T.; Koopman, M.S.; Dizeux, A.; Avramut, C.M.; Koning, R.I.; Mager, H.-J.; Rabelink, T.J.; Tanter, M.; et al. Non-Invasive Characterization of Pericyte Dysfunction in Mouse Brain Using Functional Ultrasound Localization Microscopy. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2025, ahead of print. Erratum in Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2025, ahead of print. https: //doi.org/10.1038/s41551-025-01494-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Wang, F.; Sun, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, K.; Li, J. Recent Advances in Tissue Repair of the Blood-Brain Barrier after Stroke. J. Tissue Eng. 2024, 15, 20417314241226551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Li, Z.; Sun, T.; Liu, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Barreto, G.; Li, Z.; Liu, R. Editorial: Novel Therapeutic Target and Drug Discovery for Neurological Diseases, Volume II. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1566950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, J.S.; Mak, W.Q.; Tan, L.K.S.; Ng, C.X.; Chan, H.H.; Yeow, S.H.; Foo, J.B.; Ong, Y.S.; How, C.W.; Khaw, K.Y. Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis and Its Therapeutic Applications in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carloni, S.; Rescigno, M. The Gut-Brain Vascular Axis in Neuroinflammation. Semin. Immunol. 2023, 69, 101802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasan, K.M.; Iqtadar, S.; Mudogo, C.N.; Chávez-Fumagalli, M.A. Editorial: Novel Pharmacological Targets and Strategies to Treat Neglected Global Diseases (NGDs): An LMIC Perspective. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 15, 7705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Xie, S.; Zheng, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, T.; Zhang, G. Biofluid Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2024, 16, 1380237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keikha, R.; Hashemi-Shahri, S.M.; Jebali, A. The miRNA Neuroinflammatory Biomarkers in COVID-19 Patients with Different Severity of Illness. Neurologia 2023, 38, e41–e51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Kort, A.M.; Kuiperij, H.B.; Kersten, I.; Versleijen, A.A.M.; Schreuder, F.H.B.M.; Van Nostrand, W.E.; Greenberg, S.M.; Klijn, C.J.M.; Claassen, J.A.H.R.; Verbeek, M.M. Normal Cerebrospinal Fluid Concentrations of PDGFRβ in Patients with Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy and Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2022, 18, 1788–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicognola, C.; Mattsson-Carlgren, N.; van Westen, D.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; Palmqvist, S.; Ahmadi, K.; Strandberg, O.; Stomrud, E.; Janelidze, S.; et al. Associations of CSF PDGFRβ With Aging, Blood-Brain Barrier Damage, Neuroinflammation, and Alzheimer Disease Pathologic Changes. Neurology 2023, 101, e30–e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Biomarker | Source/Location | Pathophysiological Role | Clinical Significance | Detection Method | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sPDGFRβ | CSF, released from injured pericytes | Indicates pericyte injury and BBB breakdown; correlates with neuroinflammation | Elevated in early-stage neurodegenerative disorders; correlates with cognitive decline and BBB dysfunction (QAlb) | ELISA, MSD electrochemiluminescence | [12,13,14,15] |

| CSF/Plasma Albumin Ratio (QAlb) | CSF and plasma | Reflects BBB permeability; increased ratio indicates BBB breakdown | Correlates with age, pericyte damage, and neuroinflammation; elevated in MCI and AD | Nephelometry, ELISA | [12,13,16] |

| C1q | Brain tissue, synapses (microglia-derived) | Tags synapses for complement-mediated elimination; initiates classical complement cascade | Increased and localized to synapses before plaque deposition in AD; associated with early synapse loss | Immunohistochemistry, Western blot | [17,18,19] |

| C3/iC3b | Brain tissue, synapses (astrocyte and microglia-derived) | Opsonizes synapses for microglial phagocytosis via CR3 receptor | Elevated in vulnerable brain regions; C3 deficiency protects against age-related synapse loss | Immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry | [18,19,20] |

| AQP4 Polarization Index | Astrocytic perivascular endfeet | Maintains glymphatic fluid flow; loss of polarization impairs waste clearance | Depolarization correlates with disease progression and impaired Aβ clearance | Immunofluorescence microscopy | [21,22,23] |

| CSF YKL-40 | CSF (astrocyte activation marker) | Indicates astrocytic activation and neuroinflammation | Elevated in AD and correlates with BBB dysfunction and PDGFRβ | ELISA | [24,25] |

| CSF GFAP | CSF (astrocyte marker) | Reflects astrocytic reactivity and glial activation | Increased with age and neuroinflammation; associated with BBB dysfunction | ELISA, Simoa | [26] |

| miR-124 | Plasma, CSF, brain tissue | Anti-inflammatory microRNA; maintains microglial quiescence | Downregulated in neurodegeneration; loss promotes M1 microglial polarization | qRT-PCR, sequencing | [27] |

| miR-155 | Plasma, CSF, brain tissue | Pro-inflammatory microRNA; promotes neuroinflammation | Upregulated in MS and AD; correlates with disease severity | qRT-PCR, sequencing | [28,29] |

| VEGF-C | CSF, brain tissue | Regulates meningeal lymphatic vessel function and lymphangiogenesis | Reduced levels associated with impaired brain clearance; therapeutic target | ELISA, Western blot | [30,31] |

| CSF Fibrinogen | CSF (blood-derived) | BBB leakage marker; promotes neuroinflammation | Elevated in AD; correlates with pericyte loss and reduced oxygenation | ELISA, immunohistochemistry | [12] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mansour, G.K.; Bolgova, O.; Hajjar, A.W.; Mavrych, V. Neurovascular Dysfunction and Glymphatic Impairment: An Unexplored Therapeutic Frontier in Neurodegeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11843. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411843

Mansour GK, Bolgova O, Hajjar AW, Mavrych V. Neurovascular Dysfunction and Glymphatic Impairment: An Unexplored Therapeutic Frontier in Neurodegeneration. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11843. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411843

Chicago/Turabian StyleMansour, Ghaith K., Olena Bolgova, Ahmad W. Hajjar, and Volodymyr Mavrych. 2025. "Neurovascular Dysfunction and Glymphatic Impairment: An Unexplored Therapeutic Frontier in Neurodegeneration" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11843. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411843

APA StyleMansour, G. K., Bolgova, O., Hajjar, A. W., & Mavrych, V. (2025). Neurovascular Dysfunction and Glymphatic Impairment: An Unexplored Therapeutic Frontier in Neurodegeneration. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11843. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411843