Abstract

The problem of antibiotic resistance is one of the challenges that science and medicine face in the 21st century. Nucleoside analogs have already proven as antiviral and antitumor agents, and, currently, there are more and more reports on their antibacterial and antifungal activity. The substitution of an oxygen atom by a sulfur one leads to the emergence of unique properties. Here, we report the synthesis of eight new 4-thioanalogs of 5-substituted (5-alkyloxymethyl and 5-alkyltriazolylmethyl) derivatives of 2′-deoxyuridine and uridine, which were active against Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Gram-positive bacteria. The novel sulfur-containing nucleosides were synthesized via activation of the pyrimidine C4 position, followed by condensation with thioacetic acid and deblocking. To increase the solubility, oligoglycol carbonate depot forms were obtained via activation of the 3′-hydroxyl group using N,N’-carbonyldiimidazole and condensation with triethylene glycol. The highest inhibitory activity was demonstrated by 3′-triethylene glycol depot forms of 4-thio-5-undecyl- and 5-dodecyloxymethyl-2′-deoxyuridine (4a,b) against two strains of M. smegmatis. The most promising compounds were 5-[4-decyl-(1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)methyl]-4-thio-2′-deoxy- and ribouridine (3c,g) and 5-undecyloxymethyl 4-thiouridine (3e) active toward clinical M. intracellulare isolates. Overall, novel sulfur-containing nucleoside analogs were low toxic, demonstrated better inhibitory activity compared to their C4-oxo ones, and, thus, are promising compounds for the development of new antibacterial agents.

1. Introduction

The discovery of antibiotics in the 20th century was a revolutionary event in human history, which saved millions of human lives [1,2,3]. Today, the overuse of antibiotics has led to the emergence of antibiotic resistance, giving priority to drug-resistant strains [4,5]. Inappropriate prescribing practices, increasing self-medication, and non-compliance to treatment are leading to an accelerating spread of resistant pathogens [6] that cannot be eradicated by standard chemotherapy regimens, thus causing increased mortality from infectious diseases. The World Health Organization (WHO) has declared antimicrobial resistance one of the top 10 health problems affecting humanity [6,7,8,9].

Emerging since the 1990s, the multidrug-resistant strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis pose a particular danger [10,11,12]. According to the WHO 2050 forecast, about a quarter of the 10 million deaths associated with drug resistance will be caused by drug-resistant tuberculosis strains (TB) [10]. Globally, in 2022, TB caused an estimated 1.40 million deaths [13]. In the European Region, the incidence rate decreased from 42 per 100,000 population in 2010 to 24 in 2022 [13]. While the incidence of tuberculosis has declined in developed countries, reporting data on non-tuberculous infections and diseases has shown a steady upward trend [14]. For example, in Australia, the estimated incidence rate increased from 11 per 100,000 in 2001 to 26 per 100,000 population in 2016 [15]. Nontuberculous infections are associated with age and various immunocompromised states [16,17,18]. Mycobacteria are found in patients with bronchiectasis [19,20] and cystic fibrosis [21]. They are the confirmed agents of nosocomial infections after surgery interventions [22] and even less traumatic cosmetic procedures [23]. Mycobacterium is a diverse genus, which includes more than 400 species, and 246 of them are associated with pathological processes in humans [24].

Many strategies have been proposed to combat antibiotic resistance; one of them is introducing into medical practice new antibacterial drugs that are selective for new strains and aimed at new targets [25,26].

Nucleoside derivatives are attractive compounds for the development of drugs based on them. They have already proven to act as antiviral [27] and antitumor agents [28], and, currently, there are more and more reports on the antibacterial (including antituberculosis) and antifungal activities of such compounds [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37].

Modified nucleosides, nucleotides, and oligonucleotides with an oxygen atom replaced by chalcogen atoms (sulfur, selenium, tellurium) are of great interest for scientific research. For example, the 5-substituted 2-sulfur- and selenouridines are natural components of the bacterial tRNA epitranscriptome [38]. The substitution of an oxygen atom in some components of nucleic acids by chalcogen atoms leads to the emergence of unique properties in such biomolecules associated with their altered physical and chemical properties. Sulfur-containing nucleosides occupy a special place among modified nucleosides [39]. Sulfur-containing functional groups are prevailing components found in various pharmacologically active substances and some natural products. They are valuable in the field of medicinal chemistry and are included in a large number of approved drugs and clinical candidates [40,41,42,43,44]. Previous studies have demonstrated that the introduction of a sulfur atom into a nucleoside molecule can lead to a significant increase in their antiviral [45], anticancer [39], and antituberculosis activity [37,46] compared to oxygen-containing analogs.

Previously, we obtained 5-substituted derivatives of 2′-deoxyuridine and uridine [47,48], which showed significant inhibitory activity against Gram-positive bacteria, including drug-resistant strains of M. tuberculosis and S. aureus. At present, the exact mechanism of their action remains unclear. However, our studies have shown that one of the possible targets of action of nucleoside derivatives may have direct or indirect effects on the bacterial cell wall [49,50]. On the other hand, we demonstrated that the mechanism of action of 5-alkyloxymethyl-2′-deoxyuridine 5′-monophosphates may be partially associated with inhibition of the flavin-dependent thymidylate synthase ThyX [51].

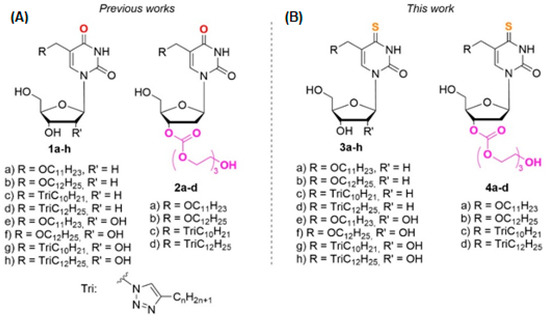

The aim of this work is to synthesize C4-thio derivatives of 2′-deoxyuridine and uridine containing an extended lipophilic fragment at the 5-position (Figure 1) and to study their antibacterial activity.

Figure 1.

Modified derivatives of pyrimidine nucleosides: (A) 1a–h and 2a–d, synthesized earlier, (B) C4-thio analogs 3a–h and 4a–d presented in this work.

Also, based on the fact that an oxygen-sulfur substitution at the C4 position of nitrogenous base should increase the lipophilicity of modified nucleosides 3a–h and decrease the solubility in aqueous media, we obtained their oligoglycol carbonate prodrugs 4a–h. As we have shown earlier, this approach allowed us to increase the solubility of 5-modified 2′-deoxyuridines by at least 2 orders of magnitude, while maintaining their antibacterial activity [52,53,54]. The results of enzymatic hydrolysis and theoretical computations, reported in our previous work [53], make it possible to assume with sufficient certainty that our synthetic carbonyltriethylene glycol derivatives of modified nucleosides are depot forms of the nucleosides possessing antibacterial activity. Moreover, in the same work, it was shown that the enzymatic hydrolysis half-time for the corresponding 4-oxo- and 4-thioderivatives did not differ significantly (τ1/2 (h) = 3 for 2b and τ1/2 (h) = 6 for 4a).

2. Results

2.1. Chemistry

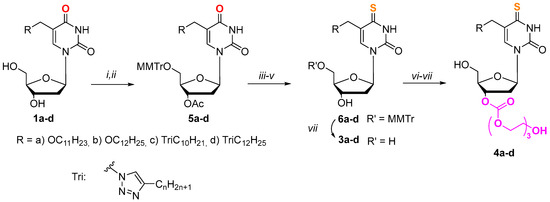

To obtain 4-thio derivatives of 5-alkyloxymethyl-2′-deoxyuridines, we initially intended to use a reaction with Lawesson’s reagent [55], but it did not lead to the formation of the expected compounds. Compounds 3a–d were synthesized according to Scheme 1, starting from 5-alkyloxymethyl-2′-deoxyuridine 1a,b [47] and 5-alkyltriazolylmethyl-2′-deoxyuridine 1c,d [47] on a mmol scale using a combination of different protecting groups. For further obtaining their 3′-triethyleneglycol depot forms, derivatives 5a–d were synthesized (Scheme 1), containing an acid-labile monomethoxytrityl fragment at the 5′-position and an acetyl group at the 3′-position. Thus, a monomethoxytrityl protective group at the 5′-position of the carbohydrate fragment was introduced at the first stage. Further treatment with the acetic anhydride allowed us to obtain 3′,5′-protected derivatives 5a–d.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of derivatives 3a–d and 4a–d. (i) MMTrCl (1.5 eq.), pyridine, 37 °C, 12 h; (ii) Ac2O (1.5 eq.), pyridine, r.t., 12 h; (iii) 1,2,4-triazole (6 eq.), 2-chlorophenyl dichlorophosphate (2.2 eq.), pyridine, r.t., 24 h; (iv) AcSH (1.5 eq.), pyridine, dioxane, r.t., 20 h; (v) NH3/H2O, EtOH, r.t., 12 h; (vi) (1) CDI (4 eq.), DMF, 37 °C, 24 h, (2) triethylene glycol (20 eq.), dioxane, 37 °C, 24 h; (vii) AcOH, H2O, r.t., 12 h.

The replacement of the oxygen atom by a sulfur one in the pyrimidine fragment in the case of 2′-deoxyuridine derivatives (Scheme 1) was carried out through activation of the C4 position according to the method of Divakar and Reese [56] in a later modification [57], followed by condensation with thioacetic acid (AcSH). To obtain derivatives 6a–d, the acetyl protecting group was removed. The 3′-hydroxyl group was activated using N,N’-carbonyldiimidazole (CDI), and condensation with triethylene glycol was carried out according to our previously developed method [52,54]. The target compounds 4a–d were synthesized by treating the condensation products with acetic acid.

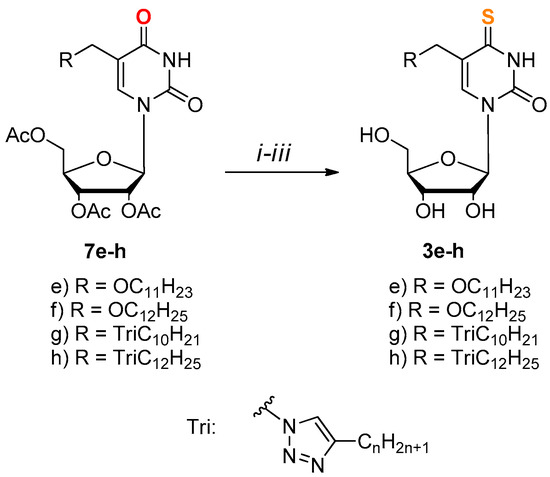

Compounds 3e–h were prepared from protected nucleosides 7e–h by condensation with thioacetic acid via 4-chloro derivatives obtained, according to the Žemlička and Šorm method [58,59] (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of derivatives 3e–h. (i) SOCl2, (1.6 eq.) DMF, DCE, Δ, 6 h; (ii) AcSH, (1.5 eq.), pyridine, dioxane, r.t., 12 h; (iii) NH3/H2O, EtOH, r.t., 12 h.

The purity and structure of the target compounds were confirmed by 1H- and 13C-NMR spectroscopy and high-resolution mass spectrometry (see the Supplementary Materials).

2.2. Water Solubility

As we initially assumed, an oxygen-sulfur substitution at the C4 position of the nitrogenous base of synthesized compounds has led to a decrease in their water solubility by at least 1.5 times compared with corresponding 4-oxoanalogs [52,54]. For example, 0.013 mg/mL for the 4-thioderivative 3a and 0.017 mg/mL for the derivative 1a. Other oxygen-containing derivatives showed solubility in the range of 0.005–0.028 mg/mL for 2′-deoxynucleosides 1a–d, 0.03–0.1 mg/mL for ribonucleosides 1e–h, and 0.78–3.6 mg/mL for oligoglycol carbonate prodrugs 2a–d.

The introduction of the oligoglycol carbonate fragment into the target nucleoside molecules allowed us to increase the solubility of compounds 3a–d by at least an order of magnitude (Table 1).

Table 1.

Water solubility of the synthesized compounds.

2.3. Cytotoxicity

The cytotoxicity of the synthesized compounds (CD50) was estimated by MTT assay [60] in HeLa and A549 cell lines. The compounds demonstrated cytotoxic activity at concentrations of 30–60 μM (3a, 3b, 3e, 3f, 4a, 4b) and 70–100 μM (3c, 3d, 3g, 3h, 4c, 4d) in both cell lines. For most compounds, the toxicity turned out to be approximately the same as for previously synthesized 4-oxo-derivatives. The exact cytotoxicity values for each compound are shown in Table S1 (see the Supplementary Materials).

2.4. In Vitro Study of Antibacterial Activity of the Obtained Compounds

Antibacterial effect of the obtained compounds was studied by their ability to suppress the growth of a number of microorganisms in vitro using two different methods: (1) bacterial strains from the collection of the Gause Institute of New Antibiotics were tested using the same method as in our previous studies [48]; and (2) mycobacterial strains and clinical isolates from the collection of the EIMB were studied using a previously developed method [61]. The details of testing bacteria for susceptibility to the developed compounds are described in the Materials and Methods Section.

The antibacterial activities were tested against the following Gram-positive bacteria: two strains of Staphylococcus aureus (ESKAPE group), including methicillin-resistant strain MRSA (MRSA strains occur widely and cause nosocomial infections that resist the modern antibiotic therapy) and Micrococcus luteus NCTC 8340, and mycobacteria: two strains of Mycobacterium smegmatis (which are used for the preliminary assessment of the activity followed by the analysis of promising compounds against the strains of the causative agent of tuberculosis, i.e., Mycobacterium tuberculosis). Some compounds under investigation showed activity against Gram-positive bacteria as well as mycobacteria (Table 2). The highest inhibitory activity (5 and 21 mg/L, respectively) was demonstrated by 3′-triethylene glycol depot forms of 5-undecyl- and 5-dodecyloxymethyl-2′-deoxyuridine (4a,b, respectively) against two strains of M. smegmatis, in contrast to the corresponding 4-oxo derivatives 2a,b, which were less active against the same strains (24 and 25 mg/L). These same derivatives also exhibited inhibitory action at concentrations of 5 and 21 mg/L, respectively, for strains of S. aureus and Mic. luteus. Unfortunately, compounds 4c,d and ribo derivatives 3e–h were inactive against the above-mentioned microorganisms. Apparently, the low solubility of the studied compounds 1a–d, 3a–d did not allow achieving inhibitory concentrations.

Table 2.

Bacterial growth minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC, mg/L) of obtained compounds.

2.5. In Vitro Study of Antimycobacterial Activity of the Obtained Compounds

The biological activity of the developed compounds toward various clinical isolates of Mycobacterium (both slow- and rapidly growing species) was tested (Table 3) as in [61].

Table 3.

Minimal mycobacterial growth inhibitory concentration (mg/L) of obtained compounds.

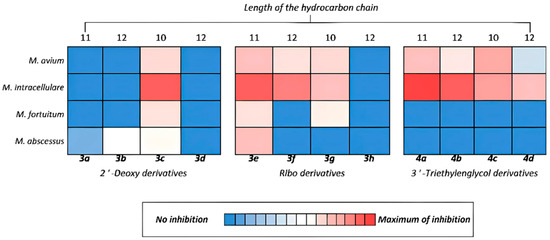

The MIC of compounds 3a, 3b, 3d, and 3h, as well as oxo derivatives 1a–h, was ≥80 mg/L, which was above the maximal tested concentration, and thus, no antimycobacterial activity was found. Compounds 2a–d have not been tested against these mycobacterial strains. 4-Thio derivatives 3c, 3e, 3g, 4a, 4b, and 4c showed noticeable activity toward all tested isolates of slow-growing species, while 3f and 4d showed variable MICs in the range of 10 mg/L to more than 80 mg/L, which corresponded to the maximal tested concentration. All developed oligoglycol carbonate prodrugs 4a–h demonstrated activity against M. avium (20–80 mg/L), with the lowest MIC of 20 mg/L for compound 4c. The lowest MIC of 10 mg/L was recorded for 3f, 3e, and 4a compounds against the slow-growing M. intracellulare isolates. Compound 3e was also active toward less-susceptible fast-growing M. abscessus, M. fortuitum, and slow-growing M. avium, while low MICs of 20 mg/L and ≥80 mg/L were recorded for different isolates. M. fortuitum also had an MIC of 80 mg/L for compound 3g. Other compounds were not active toward fast-growing strains and isolates of mycobacteria (Table 3). The details of testing mycobacteria for susceptibility to the developed compounds are described in the Materials and Methods Section.

3. Discussion

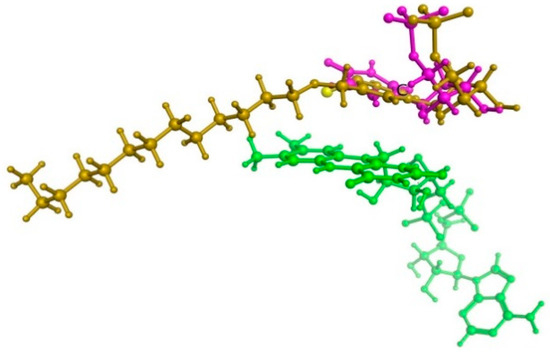

For further research into microbial inhibitors, rational methods for the synthesis of C4-thio derivatives of 2′-deoxyuridine and uridine containing an extended lipophilic fragment at the 5-position were developed. We assumed that replacing the oxygen atom in the C4 position of the nitrogenous base with a sulfur atom could lead to increased antibacterial properties of such derivatives. A hypothetical ThyX enzyme inhibitor, 5-dodecyloxymethyl-4-thio-2′-deoxyuridine 5′-monophosphate, was docked in a binding site of M. tuberculosis ThyX (PDB file 2AF6) [62] using the Molecular Operating Environment program (MOE) [63], as in our previous work [51]. The calculations revealed no significant differences in the binding of 5-alkyloxymethyl-4-thio-2′-deoxyuridine 5′-monophosphate. Figure 2 illustrates that the 4-thio inhibitor of ThyX and substrate (dUMP) have the same binding mode. The structure of 5-dodecyloxymethyl-4-thio-dUMP-ThyX complex (obtained in silico) and amino acid residues in contact with 5-dodecyloxymethyl-4-thio-dUMP are shown in Supplementary Figures S1 and S2.

Figure 2.

The superposition of dUMP substrate (marked purple) and 5-dodecyloxymethyl-4-thio-2′-deoxyuridine 5′-monophosphate (yellow) within ThyX active site. Flavine cofactor fragment (green) is also shown.

To obtain 4-thio derivatives of 5-modified 2′-deoxyuridines, a reaction with Lawesson’s reagent was first carried out [55]. This reagent allows direct one-step thionylation of the starting nucleosides [64,65]. However, in the case of 5-alkyloxymethyl derivatives, the reaction proceeded with the formation of a product of unknown structure. Similar unusual reactions with both Lawesson’s reagent and phosphorus pentasulfide are known in the literature, in each case involving the removal of a group located in the benzylic position in the presence of a carbonyl oxygen atom [66,67]. Expected derivatives were obtained through activation of the C4 position using either the method of Divakar and Reese [56,57] or the method of Žemlička and Šorm [58,59], followed by condensation with thioacetic acid and deprotection. It has been shown that Šorm‘s reaction can be a good alternative to the Divakar and Reese method. Both methods lead to the production of thio derivatives in approximately the same yields, but the first one is easier to perform. To increase the solubility of 5-modified 4-thio-2′-deoxyuridines, we used a previously developed prodrug approach, namely the introduction of triethyleneglycol fragment into the 3′-position of modified nucleosides [52,53,54].

The novel sulfur-containing nucleoside analogs demonstrated better inhibitory activity (MIC 5–80 mg/L) compared to their C4-oxo ones, and were low-toxic. The highest inhibitory activity (5 and 21 mg/L, respectively) was demonstrated by 3′-triethylene glycol depot forms of 4-thio-5-undecyl- and 5-dodecyloxymethyl-2′-deoxyuridine (4a,b, respectively) against two strains of M. smegmatis, in contrast to the corresponding 4-oxo derivatives.

The greatest activity against mycobacteria was shown by both ribo- and 2′-deoxyribonucleosides containing a triazolyl fragment with an alkyl chain length of 10 carbon atoms (derivatives 3c, 3g) and derivative 3e containing an undecyloxymethyl substituent (Figure 3). This can be explained by the fact that derivatives with this size of hydrocarbon substituent exhibit the best solubility in aqueous media (Table 1). Since a dependence was observed, the larger the hydrocarbon substituent (and therefore the lower the solubility), the less activity the compounds exhibited (Figure 3). Furthermore, unlike 5-alkyloxymethyl derivatives (3a, 3e, 4a), triazole derivatives (3c, 3d, 3g, 3h, 4c, 4d) are capable of improving the binding of the resulting compounds to biological targets due to the formation of additional hydrogen bonds and dipole interactions [68,69]. Ribonucleosides (3e–h) (containing an additional hydroxyl group at the 2′-position of the carbohydrate residue) or 2′-deoxyribonucleosides with a triethylene glycol moiety at the 3′-position (4a–d) generally inhibited mycobacterial growth better than the corresponding 2′-deoxy derivative. These results can be explained by the better solubility of the studied compounds compared to ones that did not show activity.

Figure 3.

Inhibitory activity towards mycobacteria of synthesized derivatives 3a–h and 4a–d.

Thus, the substitution of an oxygen atom in the C4 position of 5-modified nucleosides by a sulfur one leads to a significant increase in their antibacterial activity compared to oxygen-containing analogs. This is most clearly demonstrated in the case of inhibition of non-tuberculous mycobacteria: inactive oxo derivatives are converted into effective inhibitors of mycobacterial growth. They can serve as promising lead compounds for the development of new antibacterial (primarily antimycobacterial) agents. Overall, sulfur-containing analogs of modified nucleosides appear to be valuable lead compounds for the development of new therapeutic agents.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemistry

Commercial reagents from Fluka (Buchs, Switzerland), Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), and Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium) were used in this work. Solvents were purified using standard methods. Column chromatography was performed using Kieselgel 60 (40–63 μm) silica gel (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded with a Bruker AM300 at ambient temperature in DMSO-d6 and CDCl3 solutions. Chemical shift values are given in δ scale relative to Me4Si. The J values are given in hertz. UV spectra were recorded on a spectrophotometer SF-102 (Akvilon, Moscow, Russia) in methanol. High-resolution mass spectra were recorded on a micrOTOF-Q II device (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS). Measurements were carried out in two ion modes: positive and negative. The following parameters were used: capillary voltage 4500 V; mass scanning range: for positive ion polarity m/z 50–2500, for negaitive ion polarity m/z 50–3000; external calibration with LC/MS Calibration standard for ESI-TOF (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA); gas pressure 0.4 bar; nitrogen spray gas (4 L/min); interface temperature: 180 °C; and flow rate 200 μL/min. Samples were injected into the mass-spectrometer chamber from an HPLC system Agilent 1260 (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with an Agilent Poroshell 120 EC-C18 column (3.0 × 50 mm; 2.7 μm) (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). The samples were eluted in the acetonitrile gradient in 0.1% formic acid with a flow rate of 200 μL/min. Molecular ions in the spectra were analyzed and matched with the appropriately calculated m/z and isotopic profiles in the Bruker Data Analysis 4.0 program. Dry samples were dissolved in 100% methanol. All reactions were monitored with thin-layer chromatography (TLC) and carried out with Merck (Darmstadt, Germany) precoated plates DCAlufolienKieselgel60 F254.

Study of Water Solubility of Synthesized Compounds

To evaluate the solubility, a mixture of 20 mg of a compound and 3 mL of water was stirred on a magnetic stirrer for 24 h. The pellet was removed by centrifugation (14,000 rpm, 10 min). The compound concentration was inferred from UV absorption of the resulting solution.

4.2. General Method for the Synthesis of 3′-O-Acetyl-5′-O-Monomethoxytrityl-5-Alkyloxymethyl- and 5-[4-Alkyl-(1,2,3-Triazol-1-yl)Methyl]-2′-Deoxyuridines 5a–d

A nucleoside (0.5 mmol) was dissolved in dry pyridine (7 mL), then 4-monomethoxytrityl chloride (0.231 g, 0.75 mmol) was added. The reaction mixture was heated at 37 °C for 12 h. Then, the mixture was evaporated, dissolved in CHCl3, and extracted with 0.5 M sodium bicarbonate; the chloroform layer was washed with water. The organic layer was dried with Na2SO4. Then, the mixture was filtered, evaporated, and dissolved in dry pyridine (5 mL), and then acetic anhydride (0.077 g, 0.07 mL, 0.75 mmol) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred at 25 °C for 12 h, then evaporated, and the product was isolated by column chromatography in the chloroform/ethanol (60:1 v/v) eluting system with 2% DIPEA.

3′-O-Acetyl-5′-O-monomethoxytrityl-5-undecyloxymethyl-2′-deoxyuridine (5a) was prepared according to the general procedure from 1a (0.206 g, 0.5 mmol). Yield: 0.330 g (91%).

1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.46 (s, 1H, 3-NH), 7.64 (s, 1H, 6-H), 7.44–7.20 (m, 12H, MMTr), 6.94–6.85 (m, 2H, MMTr), 6.18 (dd, J = 8.1, 6.2 Hz, 1H, 1′-H), 5.36–5.23 (m, 1H, 3′-H), 4.07 (q, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H, 4′-H), 3.88 (d, J = 11.5 Hz, 1H, 5-CH2), 3.75 (s, 3H, CH3O), 3.65 (d, J = 11.6 Hz, 1H, 5-CH2b), 3.33–3.25 (m, 2H, 5′-CH2), 3.15 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H, α-CH2), 2.48–2.28 (m, 2H, 2-H′), 2.04 (s, 3H, Ac), 1.43–1.19 (m, 18H, (CH2)8, β-CH2), 0.88–0.79 (m, 3H, CH3).

3′-O-Acetyl-5′-O-monomethoxytrityl-5-dodecyloxymethyl-2′-deoxyuridine (5b) was prepared according to the general procedure from 1b (0.213 g, 0.5 mmol). Yield: 0.370 g (89%).

1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.46 (s, 1H, 3-NH), 7.64 (s, 1H, 6-H), 7.46–7.19 (m, 12H, MMTr), 6.95–6.84 (m, 2H, MMTr), 6.18 (dd, J = 8.1, 6.2 Hz, 1H, 1′-H), 5.38–5.24 (m, 1H, 3′-H), 4.07 (q, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H, 4′-H), 3.88 (d, J = 11.5 Hz, 1H, 5-CH2a), 3.75 (s, 3H, CH3O), 3.65 (d, J = 11.6 Hz, 1H, 5-CH2b), 3.31–3.26 (m, 2H, 5′-CH2), 3.15 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H, α-CH2), 2.47–2.27 (m, 2H, 2′-H), 2.05 (s, 3H, Ac), 1.37–1.16 (m, 20H, (CH2)9, β-CH2), 0.91–0.82 (m, 3H, CH3).

3′-O-Acetyl-5′-O-monomethoxytrityl 5-[4-decyl-(1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)methyl]-2′-deoxyuridine (5c) was prepared according to the general procedure from 1c (0.224 g, 0.5 mmol). Yield: 0.343 g (90%).

1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.61 (s, 1H, 3-NH), 7.97 (s, 1H, H-Tri), 7.62 (s, 1H, 6-H), 7.45–7.17 (m, 12H, MMTr), 6.94–6.84 (m, 2H, MMTr), 6.18 (dd, J = 7.7, 6.3 Hz, 1H, 1′-H), 5.31 (dt, J = 6.6, 3.0 Hz, 1H, 3′-H), 4.80 (d, J = 14.3 Hz, 1H, 5-CH2a), 4.72–4.61 (m, 1H, 5-CH2b), 4.07 (q, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H, 4′-H), 3.74 (s, 3H, CH3O), 3.38 (dd, J = 10.4, 4.8 Hz, 1H, α-CH2a), 3.29–3.19 (m, 3H, 5′-CH2, α-CH2b), 2.54 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H, 2′-Ha), 2.38 (ddd, J = 14.2, 6.4, 2.8 Hz, 1H, 2′-Hb), 2.05 (s, 3H, Ac), 1.64–1.43 (m, 2H, β-CH2), 1.38–1.14 (m, 14H, (CH2)7), 0.94–0.79 (m, 3H, CH3).

3′-O-Acetyl-5′-O-monomethoxytrityl-5-[4-dodecyl-(1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)methyl]-2′-deoxyuridine (5d) was prepared according to the general procedure from 1d (0.238 g, 0.5 mmol). Yield: 0.356 g (90%).

1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.61 (s, 1H, 3-NH), 7.97 (s, 1H, H-Tri), 7.63 (s, 1H, 6-H), 7.43–7.17 (m, 12H, MMTr), 6.95–6.84 (m, 2H, MMTr), 6.18 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H, 1′-H), 5.36–5.26 (m, 1H, 3′-H), 4.80 (d, J = 14.3 Hz, 1H, 5-CH2a), 4.67 (d, J = 14.3 Hz, 1H, 5-CH2b), 4.08 (q, J = 3.9 Hz, 1H, 4′-H), 3.73 (s, 3H, CH3O), 3.38 (dd, J = 10.5, 4.8 Hz, 1H, α-CH2a), 3.30–3.15 (m, 1H, 5′-CH2, α-CH2b), 2.54 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H, 2′-Ha), 2.38 (ddd, J = 14.2, 6.3, 2.8 Hz, 1H, 2′-Hb), 2.05 (s, 3H, Ac), 1.61–1.43 (m, 2H, β-CH2), 1.35–1.18 (m, 18H, (CH2)9), 0.97–0.74 (m, 3H, CH3).

4.3. General Method for the Synthesis of 5′-O-Monomethoxytrityl-5-Alkyloxymethyl- and 5-[4-Alkyl-(1,2,3-Triazol-1-yl)Methyl]-4-Thio-2′-Deoxyuridines 6a–d

2-Chlorophenyl dichlorophosphate (0.216 g, 0.143 mL, 0.88 mmol) was added to a solution of protected nucleoside (0.40 mmol) and 1,2,4-triazole (0.165 g, 2.4 mmol) in anhydrous pyridine, cooled to 0 °C. The mixture was stirred for 24 h at room temperature and then evaporated. The residue was partitioned between chloroform and 0.5 M sodium bicarbonate; the chloroform layer was washed with water, dried over Na2SO4, evaporated, and dissolved in anhydrous dioxane (3 mL). Then, thioacetic acid (0.043 mL, 0.6 mmol) and pyridine (1 mL) were added to a solution. The mixture was stirred for 20 h at room temperature and then evaporated, dissolved in ethanol (3 mL), and then 3 mL of conc. aq. ammonia solution was added. The mixture was stirred for 12 h at room temperature and then evaporated. The product was isolated by column chromatography in the chloroform/ethanol (30:1 v/v) eluting system with 2% DIPEA. The target fractions were evaporated in a vacuum to give the expected compound yields as a yellow amorphous mass.

5′-O-Monomethoxytrityl-5-undecyloxymethyl-4-thio-2′-deoxyuridine (6a) was prepared according to the general procedure from 5a (0.290 g, 0.4 mmol). Yield: 0.168 g (60%).

1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.78 (s, 1H, 3-NH), 7.54 (s, 1H, 6-H), 7.45–7.20 (m, 12H, MMTr), 6.98–6.79 (m, 2H, MMTr), 6.12 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 1H, 1′-H), 5.36 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H, 3′-OH), 4.24–4.12 (m, 2H, 5-CH2a, 3′-H), 4.02–3.89 (m, 2H, 5-CH2b, 4′-H), 3.75 (s, 3H, CH3O), 3.25–3.19 (m, 4H, 5′-CH2,α-CH2), 2.33–2.14 (m, 2H, 2′-H), 1.37–1.15 (m, 18H, (CH2)8, β-CH2), 0.90–0.80 (m, 3H, CH3).

5′-O-Monomethoxytrityl-5-dodecyloxymethyl-4-thio-2′-deoxyuridine (6b) was prepared according to the general procedure from 5b (0.296 g, 0.4 mmol). Yield: 0.171 g (56%).

1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.77 (s, 1H, 3-NH), 7.54 (s, 1H, 6-H), 7.46–7.17 (m, 12H, MMTr), 6.94–6.83 (m, 2H, MMTr), 6.12 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 1H, 1′-H), 5.34 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H, 3′-OH), 4.21–4.15 (m, 2H, 5-CH2a, 3′-H), 4.02–3.89 (m, 2H, 5-CH2b, 4′-H), 3.75 (s, 3H, CH3O), 3.24–3.18 (m, 4H, 5′-CH2,α-CH2), 2.32–2.14 (m, 2H, 2′-H), 1.28–1.18 (m, 20H, (CH2)9, β-CH2), 0.92–0.79 (m, 3H, CH3).

5′-O-Monomethoxytrityl-5-[4-decyl-(1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)methyl]-4-thio-2′-deoxyuridine (6c) was prepared according to the general procedure from 5c (0.305 g, 0.4 mmol). Yield: 0.162 g (55%).

1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.93 (s, 1H, 3-NH), 7.91 (s, 1H, H-Tri), 7.66 (s, 1H, 6-H), 7.39 (s, 12H, MMTr), 6.92–6.82 (m, 2H, MMTr), 6.11 (t, J = 6.2 Hz, 1H, 1′-H), 5.36 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H, 3′-OH), 5.09 (d, J = 14.2 Hz, 1H, 5-CH2a), 4.83 (d, J = 14.2 Hz, 1H, 5-CH2b), 4.36–4.19 (m, 1H, 3′-H), 3.93 (td, J = 4.8, 3.2 Hz, 1H, 4′-H), 3.75 (s, 3H, CH3O), 3.36–3.29 (m, 2H, 5′-CH2), 3.29–3.24 (m, 1H, α-CH2a), 3.18 (dd, J = 10.5, 3.2 Hz, 1H, α-CH2b), 2.39–2.21 (m, 2H, 2′-H), 1.60–1.42 (m, 2H, β-CH2), 1.28–1.21 (m, 16H, (CH2)8), 0.92–0.77 (m, 3H, CH3).

5′-O-Monomethoxytrityl-5-[4-dodecyl-(1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)methyl]-4-thio-2′-deoxyuridine (6d) was prepared according to the general procedure from 5d (0.316 g, 0.4 mmol). Yield: 0.177 g (58%).

1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.91 (s, 1H, H-Tri), 7.65 (s, 1H, 6-H), 7.44–7.17 (m, 12H, MMTr), 6.93–6.81 (m, 2H, MMTr), 6.11 (t, J = 6.2 Hz, 1H, 1′-H), 5.36 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H, 3′-OH), 5.08 (d, J = 14.2 Hz, 1H, 5-CH2a), 4.82 (d, J = 14.2 Hz, 1H, 5-CH2b), 4.34–4.22 (m, 1H, 3′-H), 3.95–3.88 (m, 1H, 4′-H), 3.73 (s, 3H, CH3O), 3.30–3.27 (m, 2H, 5′-CH2), 3.27–3.21 (m, 1H, α-CH2a), 3.18 (dd, J = 10.6, 3.2 Hz, 1H, α-CH2b), 2.32–2.23 (m, 2H, 2′-H), 1.57–1.46 (m, 2H, β-CH2), 1.25–1.21 (m, 18H, (CH2)9), 0.94–0.80 (m, 3H, CH3).

4.4. General Method for the Synthesis of 5-Alkyloxymethyl-and 5-[4-Alkyl-(1,2,3-Triazol-1-yl)Methyl]-4-Thio-2′-Deoxyuridines 3a–d

A nucleoside (0.10 mmol) was dissolved in an aqueous (80%) solution of acetic acid (7 mL); then, the mixture was stirred for 12 h at room temperature and then evaporated. The product was isolated by column chromatography in the chloroform/ethanol (9:1 v/v) eluting system.

5-Undecyloxymethyl-4-thio-2′-deoxyuridine (3a) was prepared according to the general procedure from 6a (0.07 g, 0.10 mmol). Yield: 0.041 g (96%). UV: λmax 334 nm. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.72 (s, 1H, 3-NH), 7.83 (t, J = 0.9 Hz, 1H, 6-H), 6.12 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H, 1′-H), 5.26 (d, J = 4.1 Hz, 1H, 3′-OH), 4.95 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H, 5′-OH), 4.28 (d, J = 1.0 Hz, 2H, 5-CH2), 4.23 (dt, J = 6.4, 3.4 Hz, 1H, 3′-H), 3.84 (q, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H, 4′-H), 3.62–3.51 (m, 2H, 5′-CH2), 3.44 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H, α-CH2), 2.27–2.00 (m, 2H, 2′-H), 1.60–1.44 (m, 2H, β-CH2), 1.33–1.21 (m, 16H, (CH2)8), 0.86 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 188.69 (C-4), 147.46 (C-2), 134.23 (C-6), 118.83 (C-5), 87.81 (C-4′), 85.11 (C-1′), 70.35 (C-3′), 70.13 (α-CH2), 67.20 (5-CH2), 61.23 (C-5′), 39.99 (C-2′), 31.26, 29.11, 29.00, 28.83, 28.68, 25.62, 22.05 ((CH2)9), 13.89 (CH3). HRMS (ESI) of C21H36N2O5S m/z: calcd [M − H]− 427.2261, found: 427.2280.

5-Dodecyloxymethyl-4-thio-2′-deoxyuridine (3b) was prepared according to the general procedure from 6b (0.071 g, 0.10 mmol). Yield: 0.042 g (95%). UV: λmax 334 nm. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.72 (s, 1H, 3-NH), 7.83 (t, J = 0.9 Hz, 1H, 6-H), 6.12 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H, 1′-H), 5.26 (d, J = 4.2 Hz, 1H, 3′-OH), 4.96 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H, 5′-OH), 4.28 (d, J = 1.0 Hz, 2H, 5-CH2), 4.23 (dt, J = 6.9, 3.4 Hz, 1H, 3′-H), 3.84 (q, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H, 4′-H), 3.61–3.53 (m, 2H, 5′-CH2), 3.44 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H, α-CH2), 2.26–2.04 (m, 2H, 2′-H), 1.59–1.44 (m, 2H, β-CH2), 1.36–1.20 (m, 18H, (CH2)9), 0.86 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 188.70 (C-4), 147.47 (C-2), 134.25 (C-6), 118.83 (C-5), 87.81 (C-4′), 85.12 (C-1′), 70.35 (C-3′), 70.13 (α-CH2), 67.20 (5-CH2), 61.23 (C-5′), 39.99 (C-2′), 31.26, 29.33–28.42, 25.62, 22.05 ((CH2)10), 13.90 (CH3). HRMS (ESI) of C22H38N2O5S m/z: calcd [M − H]− 441.2418, found: 441.2414.

5-[4-Decyl-(1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)methyl]-4-thio-2′-deoxyuridine (3c) was prepared according to the general procedure from 6c (0.074 g, 0.10 mmol). Yield: 0.044 g (95%). UV: λmax 332 nm. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.88 (s, 1H, 3-NH), 8.05 (s, 1H, H-Tri), 7.79 (t, J = 0.7 Hz, 1H, 6-H), 6.07 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 1H, 1′-H), 5.41–5.31 (m, 2H, 5-CH2), 4.23 (dt, J = 5.9, 3.7 Hz, 1H, 3′-H), 3.83 (q, J = 3.9 Hz, 1H, 4′-H), 3.62–3.48 (m, 2H, 5′-CH2), 2.57 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H, α-CH2), 2.29–2.09 (m, 2H, 2′-H), 1.68–1.45 (m, 2H, β-CH2), 1.34–1.20 (m, 14H, (CH2)7), 0.86 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 189.02 (C-4), 147.37 (C-2), 146.39 (C-C10H21), 137.55 (C-6), 121.98 (CH(Tri)), 115.82 (C-5), 87.91 (C-4′), 85.48 (C-1′), 69.92 (C-3′), 60.93 (C-5′), 48.67 (5-CH2), 40.05 (C-2′), 31.25, 28.94, 28.69, 24.97, 22.05 (Tri(CH2)9), 13.89 (CH3). HRMS (ESI) of C22H35N5O4S m/z: calcd [M − H]− 464.2326, found: 464.2358.

5-[4-Dodecyl-(1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)methyl]-4-thio-2′-deoxyuridine (3d) was prepared according to the general procedure from 6d (0.076 g, 0.10 mmol). Yield: 0.046 g (95%). UV: λmax 332 nm. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.87 (s, 1H, 3-NH), 8.05 (s, 1H, H-Tri), 7.79 (t, J = 0.7 Hz, 1H, 6-H), 6.10–6.04 (m, 1H, 1′-H), 5.42–5.30 (m, J = 2.7 Hz, 2H, 5-CH2), 4.29–4.18 (m, 1H, 3′-H), 3.83 (q, J = 3.9 Hz, 1H, 4′-H) 3.57–3.52 (m, 2H, 5′-CH2), 2.57 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H, α-CH2), 2.29–2.08 (m, 2H, 2′-H), 1.66–1.47 (m, 2H, β-CH2), 1.34–1.14 (m, 18H, (CH2)9), 0.86 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 189.02 (C-4), 147.34 (C-2), 146.39 (C-C12H25), 137.54 (C-6), 121.95 (CH(Tri)), 115.83 (C-5), 87.91 (C-4′), 85.48 (C-1′), 69.92 (C-3′), 60.93 (C-5′), 48.65 (5-CH2), 37.33 (C-2′), 31.24, 28.94, 28.80, 28.48, 24.97, 22.04 (Tri(CH2)11), 13.89 (CH3). HRMS (ESI) of C24H39N5O4S m/z: calcd [M − H]− 492.2639, found: 492.2685.

4.5. General Method for the Synthesis of 3′-O-(8-Hydroxy-3,6-Dioxaoct-1-Yloxy)Carbonyl-5-Alkyloxymethyl- and 5-[4-Alkyl-(1,2,3-Triazol-1-yl)Methyl]-4-Thio-2′-Deoxyuridines 4a–d

A nucleoside (0.2 mmol) was dissolved in dry dimethylformamide (2 mL), and CDI was added (0.129 g, 0.8 mmol). The mixture was heated at 37 °C for 24 h. Then, the anhydrous triethylene glycol (0.6 g, 0.55 mL, 4 mmol) and dioxane (1 mL) were added. The mixture was heated at 37 °C for 24 h and then evaporated to obtain crude oil with constant volume. The product was extracted in the chloroform–water system, the organic layer was evaporated, and then dissolved in an aqueous (80%) solution of acetic acid (5 mL). The mixture was stirred for 12 h at room temperature and then evaporated. The product was isolated by column chromatography in the chloroform/ethyl acetate/ethanol (10:10:1 v/v) eluting system.

3′-O-(8-Hydroxy-3,6-dioxaoct-1-yloxy)carbonyl-5-undecyloxymethyl-4-thio-2′-deoxyuridine (4a) was prepared according to the general procedure from 6a (0.140 g, 0.20 mmol). Yield: 0.075 g (62%). UV: λmax 334 nm. 1H NMR (300 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 7.70 (t, J = 1.4 Hz, 1H, 6-H), 6.19 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H, 1′-H), 5.31 (ddd, J = 4.5, 4.1, 2.0 Hz, 1H, 3′-H), 4.47–4.38 (m, 2H, 5-CH2), 4.38–4.30 (m, 2H, O-C(O)-OCH2(TEG)), 4.25 (q, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H, 4′-H), 3.99–3.85 (m, 2H, 5′-CH2), 3.81–3.60 (m, 10H, 5×CH2 (TEG)), 3.56 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H, α-CH2), 2.61–2.50 (m, 2H, 2′-H), 1.68–1.56 (m, 2H, β-CH2), 1.40–1.23 (m, 16H, (CH2)8), 0.90 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (75 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 187.98 (C-4), 154.40 (O-C(O)-O), 147.57 (C-2), 133.77 (C-6), 120.74 (C-5), 87.77 (C-1′), 85.45 (C-4′), 78.43 (C-3′), 72.48 (TEG), 71.56 (α-CH2), 70.66 (TEG), 70.33 (TEG), 68.80 (TEG), 67.53 (5-CH2), 67.34 (TEG), 62.57 (C-5′), 61.72 (TEG), 37.37 (C-2′), 31.90, 29.76, 29.14, 26.11, 22.67 ((CH2)9), 14.09 (CH3). HRMS (ESI) of C28H48N2O10S m/z: calcd [M − H]− 603.2946, found: 603.2943.

3′-O-(8-Hydroxy-3,6-dioxaoct-1-yloxy)carbonyl-5-dodecyloxymethyl-4-thio-2′-deoxyuridine (4b) was prepared according to the general procedure from 6b (0.142 g, 0.20 mmol). Yield: 0.067 g (54%). UV: λmax 334 nm. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.77 (s, 1H, 3-NH), 7.86 (t, J = 1.0 Hz, 1H, 6-H), 6.13 (dd, J = 8.2, 5.9 Hz, 1H, 1′-H), 5.24–5.17 (m, 1H, 3′-H), 5.17–5.10 (m, 1H, 5′-OH), 4.54 (br. s, 1H, CH2OH), 4.28 (d, J = 1.0 Hz, 2H, 5-CH2), 4.26–4.20 (m, 2H, C(O)-OCH2(TEG)), 4.14 (td, J = 3.5, 1.7 Hz, 1H, 4′-H), 3.71– 3.39 (m, 14H, 5′-CH2, 5×CH2 (TEG), α-CH2), 2.47–2.28 (m, 2H, 2′-H), 1.60–1.46 (m, 2H, β-CH2), 1.35–1.20 (m, 18H, (CH2)9), 0.86 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 188.86 (C-4), 153.79 (O-C(O)-O), 147.43 (C-2), 134.00 (C-6), 119.04 (C-5), 85.05 (C-1′), 84.94 (C-4′), 78.44 (C-3′), 72.32 (TEG), 70.16 (TEG), 69.74, 69.71 (TEG, α-CH2), 68.06 (TEG), 67.17 (5-CH2), 67.08 (TEG), 61.20 (TEG), 60.18 (C-5′), 37.15 (C-2′), 31.25, 29.28, 28.78, 28.67, 25.60, 22.04 ((CH2)10), 13.89 (CH3). HRMS (ESI) of C29H50N2O10S m/z: calcd [M + H]+ 619.3259, found: 619.3264.

3′-O-(8-Hydroxy-3,6-dioxaoct-1-yloxy)carbonyl-5-[4-decyl-(1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)methyl]-4-thio-2′-deoxyuridine (4c) was prepared according to the general procedure from 6c (0.147 g, 0.20 mmol). Yield: 0.064 g (50%). UV: λmax 332 nm. 1H NMR (300 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 8.19 (s, 1H, H-Tri), 7.59 (t, J = 0.7 Hz, 1H, 6-H), 6.23 (dd, J = 7.7, 5.9 Hz, 1H, 1′-H), 5.59–5.37 (m, 2H, 5-CH2), 5.26 (dt, J = 6.2, 1.8 Hz, 1H, 3′-H), 4.35–4.29 (m, 2H, C(O)-OCH2(TEG)), 4.29–4.24 (m, 1H, 4′-H), 3.95–3.81 (m, 2H, 5′-CH2), 3.79–3.59 (m, 10H, 5×CH2 (TEG)), 2.74–2.64 (m, 2H, α-CH2), 2.64–2.54 (m, 1H, 2′-Ha), 2.36 (ddd, J = 14.1, 7.8, 6.1 Hz, 1H, 2′-Hb), 1.73–1.57 (m, 2H, β-CH2), 1.35–1.22 (m, 14H, (CH2)7), 0.90 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (75 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 188.59 (C-4), 154.39 (O-C(O)-O), 148.58, 147.48 (C-2, C-C10H21), 137.00 (C-6), 122.70 (CH(Tri)), 117.45 (C-5), 86.99 (C-1′), 86.19 (C-4′), 78.98 (C-3′), 72.64 (TEG), 70.77 (TEG), 70.44 (TEG), 68.88 (TEG), 67.39 (TEG), 62.16 (C-5′), 61.74 (TEG), 49.00 (5-CH2), 38.85 (C-2′), 32.00, 29.68, 29.53, 29.32, 25.69, 22.77 ((CH2)9), 14.21 (CH3). HRMS (ESI) of C29H47N5O9S m/z: calcd [M + H]+ 642.3167, found: 642.3120.

3′-O-(8-Hydroxy-3,6-dioxaoct-1-yloxy)carbonyl-5-[4-dodecyl-(1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)methyl]-4-thio-2′-deoxyuridine (4d) was prepared according to the general procedure from 6d (0.153 g, 0.20 mmol). Yield: 0.078 g (58%). UV: λmax 332 nm. 1H NMR (300 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 10.45 (s, 1H, 3-NH), 8.18 (s, 1H, H-Tri), 7.58 (t, J = 0.7 Hz, 1H, 6-H), 6.23 (dd, J = 7.7, 5.9 Hz, 1H, 1′-H), 5.59–5.37 (m, 2H, 5-CH2), 5.26 (dt, J = 6.2, 1.8 Hz, 1H, 3′-H), 4.42–4.16 (m, 3H, CH2(TEG)), 4′-H), 3.95–3.81 (m, 2H, 5′-CH2), 3.81–3.56 (m, 10H, 5×CH2 (TEG)), 2.73–2.55 (m, 3H, α-CH2, 2′-Ha), 2.37 (ddd, J = 14.1, 7.8, 6.1 Hz, 1H, 2′-Hb), 1.73–1.55 (m, 2H, β-CH2), 1.38–1.12 (m, 18H, (CH2)9), 0.86 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (75 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 188.39 (C-4), 154.28 (O-C(O)-O), 148.52, 147.32 (C-2, C-C12H25), 136.86 (C-6), 122.58 (CH(Tri)), 117.31 (C-5), 86.95 (C-1′), 86.10 (C-4′), 78.86 (C-3′), 72.53 (TEG), 70.66 (TEG), 70.34 (TEG), 68.77 (TEG), 67.29 (TEG), 62.08 (C-5′), 61.65 (TEG), 48.88 (5-CH2), 38.77 (C-2′), 31.91, 29.89, 29.12, 25.59, 22.67 ((CH2)10), 14.10 (CH3). HRMS (ESI) of C31H51N5O9S m/z: calcd [M + H]+ 670.3480, found: 670.3423.

4.6. General Method for the Synthesis of 5-Alkyloxymethyl-and 5-[4-Alkyl-(1,2,3-Triazol-1-yl)Methyl]-4-Thiouridines 3e–h

A nucleoside (0.5 mmol) prepared as described in [48] was dissolved in dry dichloroethane (20 mL), then dimethylformamide (2 mL), and SOCl2 was added (0.129 g, 0.8 mmol, 0.079 mL). The reaction mixture was refluxed for 6 h. Then, the mixture was evaporated and co-evaporated with toluene two times and dissolved in dry dioxane (5 mL). Then, thioacetic acid (0.054 mL, 0.75 mmol) and pyridine (1 mL) were added to a solution. The mixture was stirred for 20 h at room temperature and then evaporated, dissolved in ethanol (5 mL), and then 5 mL of conc. aq. ammonia solution was added. The mixture was stirred for 12 h at room temperature and then evaporated. The product was isolated by column chromatography in the chloroform/ethanol (20:1 v/v) eluting system. The target fractions were evaporated in a vacuum to give the expected compound yields as a yellow powder.

5-Undecyloxymethyl-4-thiouridine (3e) was prepared according to the general procedure from 7e (0.277 g, 0.50 mmol). Yield: 0.119 g (54%). UV: λmax 330 nm. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.74 (s, 1H, 3-NH), 7.94–7.88 (m, 1H, 6-H), 5.79 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 1H, 1′-H), 5.44 (br. s, 1H, 2′-OH), 5.16–4.96 (m, 2H, 3′-OH, 5′-OH), 4.33–4.21 (m, 2H, 5-CH2), 4.09–4.02 (m, 1H, 2′-H), 4.00–3.94 (m, 1H, 3′-H), 3.93–3.85 (m, 1H, 4′-H), 3.71–3.50 (m, 2H, 5′-CH2), 3.43 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H, α-CH2), 1.58–1.45 (m, 2H, β-CH2), 1.31–1.23 (m, 16H, (CH2)8), 0.86 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 188.95 (C-4), 147.78 (C-2), 134.63 (C-6), 118.90 (C-5), 88.43 (C-1′), 85.07 (C-4′), 73.97 (C-2′), 70.16 (C-3′), 69.86 (α-CH2), 67.21 (5-CH2), 60.77 (C-5′), 31.28, 29.21, 28.77, 28.69, 25.63, 22.46, 22.07, ((CH2)9), 13.92 (CH3). HRMS (ESI) of C21H36N2O6S m/z: calcd [M − H]− 443.2210, found: 443.2215.

5-Dodecyloxymethyl-4-thiouridine (3f) was prepared according to the general procedure from 7f (0.284 g, 0.50 mmol). Yield: 0.114 g (50%). UV: λmax 330 nm.1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.73 (s, 1H, 3-NH), 8.00–7.79 (m, 1H, 6-H), 5.79 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 1H, 1′-H), 5.44 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H, 2′-OH), 5.09 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H, 3′-OH), 5.05 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H, 5′-OH), 4.33–4.22 (m, 2H, 5-CH2), 4.06 (dt, J = 5.1, 5.0 Hz, 1H, 2′-H), 3.97 (td, J = 5.1, 4.4 Hz, 1H, 3′-H), 3.90 (dt, J = 4.4, 3.5 Hz, 1H, 4′-H), 3.61 (qdd, J = 12.0, 4.9, 3.2 Hz, 2H, 5′-CH2), 3.43 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H, α-CH2), 1.59–1.45 (m, 2H, β-CH2), 1.39–1.15 (m, 18H, (CH2)9), 0.86 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 188.94 (C-4), 147.77 (C-2), 134.62 (C-6), 118.89 (C-5), 88.43 (C-1′), 85.07 (C-4′), 73.97 (C-2′), 70.16 (C-3′), 69.86 (α-CH2), 67.21 (5-CH2), 60.77 (C-5′), 31.28, 29.08, 29.02, 28.86, 28.70, 25.63, 22.08 ((CH2)10), 13.92 (CH3). HRMS (ESI) of C22H38N2O6S m/z: calcd [M − H]− 457.2367, found: 457.2363.

5-[4-Decyl-(1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)methyl]-4-thiouridine (3g) was prepared according to the general procedure from 7g (0.295 g, 0.50 mmol). Yield: 0.132 g (55%). UV: λmax 328 nm.1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.89 (s, 1H, 3-NH), 8.21 (s, 1H, H-Tri), 7.79 (s, 1H, 6-H), 5.73 (d, J = 4.1 Hz, 1H, 1′-H), 5.39–5.28 (m, 2H, 5-CH2), 4.07 (dd, J = 5.0, 4.1 Hz, 1H, 2′-H), 3.98 (dd, J = 5.5, 5.0 Hz, 1H, 3′-H), 3.89 (dt, J = 5.5, 3.2 Hz, 1H, 4′-H), 3.69 (dd, J = 12.2, 3.2 Hz, 1H, 5′-CH2a), 3.56 (dd, J = 12.2, 3.4 Hz, 1H, 5′-CH2b), 2.57 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H, α-CH2), 1.62–1.49 (m, 2H, β-CH2), 1.31–1.21 (m, 14H, (CH2)7), 0.86 (t, J = 6.8, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 189.20 (C-4), 147.60 (C-2), 146.38 (C-C10H21), 137.92 (C-6), 121.99 (CH-Tri), 115.84 (C-5), 89.08 (C-1′), 84.84 (C-4′), 73.99 (C-2′), 69.19 (C-3′), 60.33 (C-5′), 48.72 (5-CH2), 31.27, 28.97, 28.81, 28.55, 25.00, 22.07 ((CH2)9), 13.91 (CH3). HRMS (ESI) of C22H35N5O5S m/z: calcd [M + H]+: 482.2432, found: 482.2417.

5-[4-Dodecyl-(1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)methyl]-4-thiouridine (3h) was prepared according to the general procedure from 7h (0.309 g, 0.50 mmol). Yield: 0.142 g (56%). UV: λmax 328 nm. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.89 (s, 1H, 3-NH), 8.21 (s, 1H, H-Tri), 7.79 (s, 1H, 6-H), 5.73 (d, J = 4.5 Hz, 1H, 1′-H), 5.49–5.18 (m, 2H, 5-CH2), 4.07 (t, J = 4.5 Hz, 1H, 2′-H), 3.98 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H, 3′-H), 3.92–3.86 (m, 1H, 4′-H), 3.69 (dd, J = 12.2, 3.2 Hz, 1H, 5′-CH2a), 3.56 (dd, J = 12.3, 3.3 Hz, 1H, 5′-CH2b), 2.58 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H, α-CH2), 1.63–1.46 (m, 2H, β-CH2), 1.28–1.20 (m, 18H, (CH2)9), 0.86 (t, J = 6.8, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 189.17 (C-4), 147.57 (C-2), 146.35 (C-C12H25), 137.91 (C-6), 121.98 (CH-Tri), 115.81 (C-5), 89.06 (C-1′), 84.82 (C-4′), 73.97 (C-2′), 69.17 (C-3′), 60.31 (C-5′), 48.71 (5-CH2), 31.25, 28.98, 28.86, 28.26, 24.98, 22.05 ((CH2)11), 13.90 (CH3). HRMS (ESI) of C24H39N5O5S m/z: calcd [M + H]+: 510.2745, found: 510.2734.

4.7. Bacterial Strains and In Vitro Study of the Antibacterial Effect

The following test strains were used: Gram-positive bacteria Micrococcus luteus NCTC 8340, Staphylococcus aureus FDA 209P and INA 00761 (MRSA); mycobacteria Mycobacterium smegmatis mc2 155, and M. smegmatis VKPM Ac-1339, all from the collection of the Gause Institute of New Antibiotics.

Test strains were incubated in modified Gause’s nutrient medium liquid № 2. The level of infection with test cultures was 106 cells/mL. A compound being tested was dissolved in 30% aq. methanol. Ten volume percent of the tested compound solution was added to the nutrient medium. Samples without the addition of substances, antibiotics in medical use (amikacin, ciprofloxacin, isoniazid, rifampicin, oxacillin, and vancomycin), and samples of medium supplemented with a mixture of solvent served as control of the test culture growth. All strains were incubated at 37°C.

4.8. Mycobacterial Strains and Susceptibility Testing of Mycobacteria

The following strains from the laboratory collection were used: M. smegmatis mc2 155, M. fortuitum ATCC 6841. Clinical isolates of M. abscessuss (N24-001, N24-009, N24-020, N24-021), M. avium (N28-003, N26-008), and M. intracellulare (N24-016, N24-017, N24-003) were obtained from the confirmed infection cases upon the study of nontuberculous mycobacteria diversity in Russia [70]. The MIC values for Mycobacterium species were determined by the broth microdilution method using the 96-well plates following the CLSI guidelines [71]. The cation-adjusted Mueller–Hinton broth (HiMedia Laboratories Pvt. Limited, Maharashtra, India, M391) with 5% OADC (HiMedia Laboratories Pvt. Limited, FD018) addition was used. All compounds were dissolved in DMSO to an 8 mg/L concentration, used as the starting solution for the 2× dilutions. Each well contained 200 μL of the dissolved bacterial cells and 2 μL of the DMSO solution of the compounds. The growth of the strains and isolates in wells were recorded by the addition of resazurin (Sigma-Aldrich, R7017) and visual inspection after 1–2 days for fast-growing species and 2–6 days for slow-growing species [72].

The susceptibility of mycobacterial strains and isolates to clarithromycin, rifampicin, ethambutol, and amikacin (all from Sigma-Aldrich), used for the treatment of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections, was also tested in the same conditions. The only exception was the use of water was used for dissolving amikacin. The MIC values obtained fit perfectly with the previously reported ranges [61].

5. Conclusions

In summary, we have developed a convenient method for the preparation of 4-thioanalogs of 5-substituted (5-alkyloxymethyl and 5-alkyltriazolylmethyl) derivatives of 2′-deoxyuridine and uridine. We have demonstrated that the substitution of an oxygen atom in the C4 position of modified nucleosides by a sulfur one leads to a significant increase in their antibacterial activity compared to oxygen-containing analogs. Obtained compounds showed noticeable in vitro activity against M. smegmatis, S. aureus, and Mic. luteus with the MIC range comparable to some clinically used antibiotics. Of particular interest is the inhibitory effect of newly synthesized compounds toward a set of mycobacteria that are characterized by intrinsic resistance to a wide range of antibacterial drugs. Two compounds (3c, 3e) are active toward both laboratory strains and clinical isolates—the causative agents of mycobacterial diseases, including slow-growing M. avium and M. intracellulare, and rapidly growing M. abscessus and M. fortuitum. The obtained nucleoside derivatives can serve as promising lead compounds for the development of new antibacterial (primarily antimycobacterial) agents.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms262311712/s1. Reference [73] are cited in the supplementary materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: L.A.A. and S.N.K.; methodology, L.A.A., O.V.E. and D.V.Z.; data curation: L.A.A.; funding acquisition: S.N.K.; investigation: D.A.M., M.V.J., S.D.N., I.L.K., E.V.U., V.O.C., O.V.E., B.F.V., D.V.Z. and A.I.U.; validation: L.A.A. and S.N.K.; writing—original draft: D.A.M. and L.A.A.; writing—review and editing: D.A.M., M.V.J., I.L.K., O.V.E., D.V.Z., S.N.K. and L.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Russian Scientific Foundation (Grant number: 23-14-00106).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aminov, R.I. A Brief History of the Antibiotic Era: Lessons Learned and Challenges for the Future. Front. Microbiol. 2010, 1, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, M.S.; Henderson, I.R.; Capon, R.J.; Blaskovich, M.A.T. Antibiotics in the Clinical Pipeline as of December 2022. J. Antibiot. 2023, 76, 431–473, Erratum in J. Antibiot. 2024, 77, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, M.A.; Wright, G.D. The Past, Present, and Future of Antibiotics. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022, 14, eabo7793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventola, C.L. The Antibiotic Resistance Crisis: Part 1: Causes and Threats. Pharm. Ther. 2015, 40, 277–283. [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta, S.; Chattopadhyay, M.K.; Grossart, H.-P. The Multifaceted Roles of Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance in Nature. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Antibiotic Resistance Surveillance Report 2025; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025; ISBN 978-92-4-011633-7. [Google Scholar]

- Ralhan, K.; Iyer, K.A.; Diaz, L.L.; Bird, R.; Maind, A.; Zhou, Q.A. Navigating Antibacterial Frontiers: A Panoramic Exploration of Antibacterial Landscapes, Resistance Mechanisms, and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies. ACS Infect. Dis. 2024, 10, 1483–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santajit, S.; Indrawattana, N. Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Resistance in ESKAPE Pathogens. Biomed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 2475067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner-Lastinger, L.M.; Abner, S.; Edwards, J.R.; Kallen, A.J.; Karlsson, M.; Magill, S.S.; Pollock, D.; See, I.; Soe, M.M.; Walters, M.S.; et al. Antimicrobial-Resistant Pathogens Associated with Adult Healthcare-Associated Infections: Summary of Data Reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network, 2015–2017. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2020, 41, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report. 2022. Available online: www.who.int/health-topics/tuberculosis (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Bahuguna, A.; Rawat, D.S. An Overview of New Antitubercular Drugs, Drug Candidates, and Their Targets. Med. Res. Rev. 2020, 40, 263–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brode, S.K.; Daley, C.L.; Marras, T.K. The Epidemiologic Relationship between Tuberculosis and Non-Tuberculous Mycobacterial Disease: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2014, 18, 1370–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2023; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; ISBN 9789240083851. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, V.N.; Mølhave, M.; Fløe, A.; van Ingen, J.; Schön, T.; Lillebaek, T.; Andersen, A.B.; Wejse, C. Global Trends of Pulmonary Infections with Nontuberculous Mycobacteria: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 125, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, R.M.; Furuya-Kanamori, L.; Coffey, C.; Bell, S.C.; Knibbs, L.D.; Lau, C.L. Influence of Climate Variables on the Rising Incidence of Nontuberculous Mycobacterial (NTM) Infections in Queensland, Australia 2001–2016. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 740, 139796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behra, P.R.K.; Pettersson, B.M.F.; Ramesh, M.; Das, S.; Dasgupta, S.; Kirsebom, L.A. Comparative Genome Analysis of Mycobacteria Focusing on TRNA and Non-Coding RNA. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Ponnuswamy, A.; Capstick, T.G.; Chen, C.; McCabe, D.; Hurst, R.; Morrison, L.; Moore, F.; Gallardo, M.; Keane, J.; et al. Non-Tuberculous Mycobacterial Pulmonary Disease (NTM-PD): Epidemiology, Diagnosis and Multidisciplinary Management. Clin. Med. 2024, 24, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brode, S.K.; Jamieson, F.B.; Ng, R.; Campitelli, M.A.; Kwong, J.C.; Paterson, J.M.; Li, P.; Marchand-Austin, A.; Bombardier, C.; Marras, T.K. Increased Risk of Mycobacterial Infections Associated with Anti-Rheumatic Medications. Thorax 2015, 70, 677–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, U.-I.; Holland, S.M. Host Susceptibility to Non-Tuberculous Mycobacterial Infections. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 968–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, D.; van Ingen, J.; van der Laan, R.; Obradovic, M.; NTM-NET. Non-Tuberculous Mycobacterial Lung Disease in Patients with Bronchiectasis: Perceived Risk, Severity and Guideline Adherence in a European Physician Survey. BMJ open Respir. Res. 2020, 7, e000498, Correction in BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2020, 7, e000498corr1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, M.D.; Alam, M.E.; Franciosi, A.N.; Quon, B.S. Global Burden of Nontuberculous Mycobacteria in the Cystic Fibrosis Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. ERJ open Res. 2023, 9, 00336-2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, C.X.; Zhang, J.B.; Ji, H.L.; Li, X.R.; Luo, J.F.; Fu, A.S.; Ge, Y.L.; Liu, T.J.; Chen, T. Multiple Postoperative Lung Infections after Thymoma Surgery Diagnosed as Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Infection. Clin. Lab. 2024, 70, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Li, X.-Y.; Liu, J.-W. Demographic and Clinical Features of Nontuberculous Mycobacteria Infection Resulting from Cosmetic Procedures: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 149, 107259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimenkov, D.; Ushtanit, A. Comparative Analysis of Evolutionary Distances Using the Genus Mycobacterium. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, P.S. Antibacterial Discovery: 21st Century Challenges. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belay, W.Y.; Getachew, M.; Tegegne, B.A.; Teffera, Z.H.; Dagne, A.; Zeleke, T.K.; Abebe, R.B.; Gedif, A.A.; Fenta, A.; Yirdaw, G.; et al. Mechanism of Antibacterial Resistance, Strategies and next-Generation Antimicrobials to Contain Antimicrobial Resistance: A Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1444781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, E. Human Viral Diseases: What Is next for Antiviral Drug Discovery? Curr. Opin. Virol. 2012, 2, 572–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shelton, J.; Lu, X.; Hollenbaugh, J.A.; Cho, J.H.; Amblard, F.; Schinazi, R.F. Metabolism, Biochemical Actions, and Chemical Synthesis of Anticancer Nucleosides, Nucleotides, and Base Analogs. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 14379–14455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrova, L.A.; Khandazhinskaya, A.L.; Matyugina, E.S.; Makarov, D.A.; Kochetkov, S.N. Analogues of Pyrimidine Nucleosides as Mycobacteria Growth Inhibitors. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yssel, A.E.J.; Vanderleyden, J.; Steenackers, H.P. Repurposing of Nucleoside- and Nucleobase-Derivative Drugs as Antibiotics and Biofilm Inhibitors. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 2156–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordheim, L.P.; Durantel, D.; Zoulim, F.; Dumontet, C. Advances in the Development of Nucleoside and Nucleotide Analogues for Cancer and Viral Diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2013, 12, 447–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osada, H. Discovery and Applications of Nucleoside Antibiotics beyond Polyoxin. J. Antibiot. 2019, 72, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugg, T.D.H.; Kerr, R.V. Mechanism of Action of Nucleoside Antibacterial Natural Product Antibiotics. J. Antibiot. 2019, 72, 865–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serpi, M.; Ferrari, V.; Pertusati, F. Nucleoside Derived Antibiotics to Fight Microbial Drug Resistance: New Utilities for an Established Class of Drugs? J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 10343–10382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, V.; Serpi, M. Nucleoside Analogs and Tuberculosis: New Weapons against an Old Enemy. Future Med. Chem. 2015, 7, 291–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platonova, Y.B.; Volov, A.N.; Tomilova, L.G. The Synthesis and Antituberculosis Activity of 5-Alkynyl Uracil Derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 30, 127351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platonova, Y.B.; Kirillova, V.A.; Volov, A.N.; Savilov, S.V. Synthesis and Antitubercular Activity of New 5-Alkynyl Derivatives of 2-Thiouridine. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 59, 2083–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccaletto, P.; Machnicka, M.A.; Purta, E.; Piątkowski, P.; Bagiński, B.; Wirecki, T.K.; de Crécy-Lagard, V.; Ross, R.; Limbach, P.A.; Kotter, A.; et al. MODOMICS: A Database of RNA Modification Pathways. 2017 Update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D303–D307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wnuk, S.F. Sulfur- and Seleno-Sugar Modified Nucleosides. Synthesis, Chemical Transformations and Biological Properties. Tetrahedron 1993, 49, 9877–9936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, K.A.; Njardarson, J.T. Analysis of US FDA-Approved Drugs Containing Sulfur Atoms; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa, M.; Winum, J.-Y. The Importance of Sulfur-Containing Motifs in Drug Design and Discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2022, 17, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathania, S.; Narang, R.K.; Rawal, R.K. Role of Sulphur-Heterocycles in Medicinal Chemistry: An Update. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 180, 486–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Cierpicki, T.; Grembecka, J. Thioamides in Medicinal Chemistry and as Small Molecule Therapeutic Agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 277, 116732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maji, S.; Debnath, B.; Panda, S.; Manna, T.; Maity, A.; Dayaramani, R.; Nath, R.; Khan, S.A.; Akhtar, M.J. Anticancer Potential of the S -Heterocyclic Ring Containing Drugs and Its Bioactivation to Reactive Metabolites. Chem. Biodivers. 2024, 21, e202400473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brancale, A.; McGuigan, C.; Algain, B.; Savy, P.; Benhida, R.; Fourrey, J.-L.; Andrei, G.; Snoeck, R.; De Clercq, E.; Balzarini, J. Bicyclic Anti-VZV Nucleosides: Thieno Analogues Retain Full Antiviral Activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001, 11, 2507–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakya, N.; Srivastav, N.C.; Bhavanam, S.; Tse, C.; Desroches, N.; Agrawal, B.; Kunimoto, D.Y.; Kumar, R. Discovery of Novel 5-(Ethyl or Hydroxymethyl) Analogs of 2′-‘up’ Fluoro (or Hydroxyl) Pyrimidine Nucleosides as a New Class of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis, Mycobacterium Bovis and Mycobacterium Avium Inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012, 20, 4088–4097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmalenyuk, E.R.; Chernousova, L.N.; Karpenko, I.L.; Kochetkov, S.N.; Smirnova, T.G.; Andreevskaya, S.N.; Chizhov, A.O.; Efremenkova, O.V.; Alexandrova, L.A. Inhibition of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Strains H37Rv and MDR MS-115 by a New Set of C5 Modified Pyrimidine Nucleosides. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 4874–4884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarov, D.A.; Negrya, S.D.; Jasko, M.V.; Karpenko, I.L.; Solyev, P.N.; Chekhov, V.O.; Kaluzhny, D.N.; Efremenkova, O.V.; Vasilyeva, B.F.; Chizhov, A.O.; et al. 5-Substituted Uridines with Activity against Gram-Positive Bacteria. ChemMedChem 2023, 18, e202300366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostroumova, O.S.; Efimova, S.S.; Zlodeeva, P.D.; Alexandrova, L.A.; Makarov, D.A.; Matyugina, E.S.; Sokhraneva, V.A.; Khandazhinskaya, A.L.; Kochetkov, S.N. Derivatives of Pyrimidine Nucleosides Affect Artificial Membranes Enriched with Mycobacterial Lipids. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khandazhinskaya, A.L.; Matyugina, E.S.; Alexandrova, L.A.; Kezin, V.A.; Chernousova, L.N.; Smirnova, T.G.; Andreevskaya, S.N.; Popenko, V.I.; Leonova, O.G.; Kochetkov, S.N. Interaction of 5-Substituted Pyrimidine Nucleoside Analogues and M.tuberculosis: A View through an Electron Microscope. Biochimie 2020, 171–172, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexandrova, L.A.; Chekhov, V.O.; Shmalenyuk, E.R.; Kochetkov, S.N.; El-Asrar, R.A.; Herdewijn, P. Synthesis and Evaluation of C-5 Modified 2′-Deoxyuridine Monophosphates as Inhibitors of M. tuberculosis Thymidylate Synthase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015, 23, 7131–7137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrya, S.D.; Jasko, M.V.; Solyev, P.N.; Karpenko, I.L.; Efremenkova, O.V.; Vasilyeva, B.F.; Sumarukova, I.G.; Kochetkov, S.N.; Alexandrova, L.A. Synthesis of Water-Soluble Prodrugs of 5-Modified 2′-Deoxyuridines and Their Antibacterial Activity. J. Antibiot. 2020, 73, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrya, S.D.; Jasko, M.V.; Makarov, D.A.; Solyev, P.N.; Karpenko, I.L.; Shevchenko, O.V.; Chekhov, O.V.; Glukhova, A.A.; Vasilyeva, B.F.; Efimenko, T.A.; et al. Glycol and Phosphate Depot Forms of 4- and/or 5-Modified Nucleosides Exhibiting Antibacterial Activity. Mol. Biol. 2021, 55, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrya, S.D.; Jasko, M.V.; Makarov, D.A.; Karpenko, I.L.; Solyev, P.N.; Chekhov, V.O.; Efremenkova, O.V.; Vasilieva, B.F.; Efimenko, T.A.; Kochetkov, S.N.; et al. Oligoglycol Carbonate Prodrugs of 5-Modified 2′-Deoxyuridines: Synthesis and Antibacterial Activity. Mendeleev Communictions 2022, 32, 433–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatoon, H.; Abdulmalek, E. A Focused Review of Synthetic Applications of Lawesson’s Reagent in Organic Synthesis. Molecules 2021, 26, 6937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Divakar, K.J.; Reese, C.B. 4-(1,2,4-Triazol-1-yl)- and 4-(3-Nitro-1,2,4-Triazol-1-yl)-1-(β-D-2,3,5-Tri-O-Acetylarabinofuranosyl)Pyrimidin-2(1H)-Ones. Valuable Intermediates in the Synthesis of Derivatives of 1-(β-D-Arabinofuranosyl)Cytosine (Ara-C). J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1 1982, 1, 1171–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.S.; Gao, Y.S.; Mancini, W.R. Synthesis and Biological Activity of Various 3′-Azido and 3′-Amino Analogs of 5-Substituted Pyrimidine Deoxyribonucleosides. J. Med. Chem. 1983, 26, 1691–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žemlička, J.; Šorm, F. Nucleic Acids Components and Their Analogues. LXI. The Reaction of Dimethylchloromethyleneammonium Chloride with the 2′,3′,5′-Tri-O-Acyl Derivatives of Uridine and 6-Azauridine; A New Synthesis of 6-Azacytidine. Collect. Czechoslov. Chem. Commun. 1965, 30, 2052–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, A.; Itoh, H.; Takenuki, K.; Sasaki, T.; Ueda, T. Alkyl Addition Reaction of Pyrimidine 2′-Ketonucleosides: Synthesis of 2′-Branched-Chain Sugar Pyrimidine Nucleosides. Nucleodides and Nucleotides. LXXXI. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1988, 36, 945–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikš, M.; Otto, M. Towards an Optimized MTT Assay. J. Immunol. Methods 1990, 130, 149–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimenkov, D. Variability of Mycobacterium Avium Complex Isolates Drug Susceptibility Testing by Broth Microdilution. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampathkumar, P.; Turley, S.; Ulmer, J.E.; Rhie, H.G.; Sibley, C.H.; Hol, W.G.J. Structure of the Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Flavin Dependent Thymidylate Synthase (MtbThyX) at 2.0Å Resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 2005, 352, 1091–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemical Computing Group Inc. Molecular Operating Environment (MOE); Chemical Computing Group Inc.: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ozturk, T.; Ertas, E.; Mert, O. Use of Lawesson’s Reagent in Organic Syntheses. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 5210–5278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, K.; Katayama, H.; Wakabayashi, T.; Kumonaka, T. Pyrimidine Derivatives; 1. The Highly Regioselective 4-Thionation of Pyrimidine-2,4(1H,3H)-Dione Derivatives with Lawesson Reagent. Synthesis 1988, 1988, 152–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobi, P.A.; Guo, J.; Zheng, W. An Unequivocal Synthesis of the Ring-A,B Dihydropyrromethenone of Phytochrome. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 1197–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kateb, A.A.; Abd El-Rahman, N.M. Synthesis of New Heterocyclic Compounds Using Lawesson Reagent. Phosphorus. Sulfur. Silicon Relat. Elem. 2006, 181, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amblard, F.; Cho, J.H.; Schinazi, R.F. Cu (I)-catalyzed Huisgen azide− alkyne 1, 3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction in nucleoside, nucleotide, and oligonucleotide chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 4207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolb, H.C.; Sharpless, K.B. The growing impact of click chemistry on drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today 2003, 8, 1128–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimenkov, D.; Zhuravlev, V.; Ushtanit, A.; Filippova, M.; Semenova, U.; Solovieva, N.; Sviridenko, M.; Khakhalina, A.; Safonova, S.; Makarova, M.; et al. Biochip-Based Identification of Mycobacterial Species in Russia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI. Susceptibility Testing of Mycobacteria, Nocardia Spp., and Other Aerobic Actinomycetes, 3rd ed.; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2018; ISBN 9781684400263. [Google Scholar]

- Parish, T.; Kumar, A. (Eds.) Methods in Molecular Biology. In Mycobacteria Protocols; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 2314, ISBN 978-1-0716-1459-4. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, A.C.; Laskowski, R.A.; Thornton, J.M. LIGPLOT: A program to generate schematic diagrams of protein-ligand interactions. Protein Eng. 1995, 8, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).