Abstract

High-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) is the leading etiological factor in cervical cancer, creating a pressing need for less invasive and more objective diagnostic tools. This pilot study pioneers the application of Raman spectroscopy to cell-free cervicovaginal lavage (CVL) for distinguishing between low-grade and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL and HSIL) in HPV-positive patients. Raman spectra were acquired at 532-nm excitation from cell-free CVL samples of 20 patients with histologically confirmed LSIL (n = 9) or HSIL (n = 11). Comparative analysis of Raman bands revealed a significant biochemical shift in HSIL, presumably characterized by reduced glycogen and lactate/lactic acid levels alongside substantially elevated heme proteins. A diagnostic model based on key spectral intensity ratios achieved differentiation between LSIL and HSIL with 80% sensitivity and 86% specificity. These findings demonstrate that Raman spectroscopy of cell-free CVL effectively captures profound metabolic and microvascular alterations characteristic of neoplastic progression, showcasing its strong potential as a rapid, cost-effective, non-invasive, and objective tool for cervical lesion risk stratification.

1. Introduction

Cervical diseases associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) are a major challenge in onco-gynecology [1,2]. In 2022, cervical cancer ranked fourth globally in both incidence and mortality among women, with 662,000 new cases and 349,000 deaths [3]. High-risk HPV is the leading cause, responsible for >95% of cervical cancers, 70% of vulvar/vaginal cancers, 60% of oropharyngeal cancers, and 90% of anal canal cancers [1,4].

The most widely applied and standardized method of cervical cancer screening is cytology followed by histological examination for the final confirmation of the diagnosis. At the same time, this is an invasive, labor-intensive, and time-delayed procedure, which exhibits significant limitations related to lesion visibility and the risk of missing altered areas [5,6]. While colposcopy aids in visual diagnosis and biopsy targeting, its accuracy is operator-dependent and lacks molecular insight [7]. This creates a need for new, sensitive, and accessible techniques. HPV DNA testing is now the primary screening method due to its high sensitivity for precancer [8]. Optical methods like fluorescent and multispectral imaging, optical coherence tomography, and Raman spectroscopy can expand ex vivo and in vivo analysis by providing a biochemical basis for visual assessment [2,9,10]. Analyzing biofluids via liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), or spectroscopy for proteomic/metabolomic markers is a promising non-invasive approach [11,12].

Raman spectroscopy is a rapid, contact-free, and non-destructive universal method for analysis of biomedical samples, such as cells, tissues, and fluids, identifying specific molecular vibrations from various biochemical components, including DNA, RNA, proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates. It shows great potential for noninvasive detection of cervical precancer and cancer in cells and tissues, with studies reporting accuracies up to 98.5% for distinguishing HPV status and 90% sensitivity for identifying high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) [13,14,15,16,17,18]. Beyond cells and tissues, cervicovaginal fluid (CVF), containing epithelial cells of the cervix and vagina, and intercellular and drainage fluids, can provide a broader picture of pathological changes. Initially used forensically [19,20,21], Raman spectroscopy of dried cell-free CVF has also been explored for detecting HPV and dysplasia, though without reported classification rates [1,22]. Cell-free CVF offers more stable Raman signals by eliminating interference from cellular debris, bacteria, and mucus.

This work uses cell-free cervicovaginal lavage (CVL) for its non-invasive, standardized collection, overcoming CVF’s reproducibility issues. We employed Raman spectroscopy to analyze cell-free CVL, identifying biomarkers to distinguish between HPV-associated low- and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL and HSIL) with high classification rates, demonstrating its potential for predicting neoplastic transformation risk.

2. Results

2.1. Cell-Free Cervicovaginal Lavage Composition Revealed by Spectral Analysis

To investigate the biochemical composition of cell-free CVL, we applied multivariate curve resolution (MCR) analysis [23,24,25] to the processed Raman spectra from a set of CVL samples () obtained from patients with histologically confirmed LSIL or HSIL and presence of HPV. This method decomposes the spectral data into non-negative components representing the spectral profiles of constituents and their relative weights (scores), thereby facilitating biochemical interpretation. Although applying this deconvolution to Raman spectra rarely allows unambiguous identification of pure chemical substances, this method is still effective for revealing correlations in intensities of Raman bands further used for differentiation and highlighting their probable assignments.

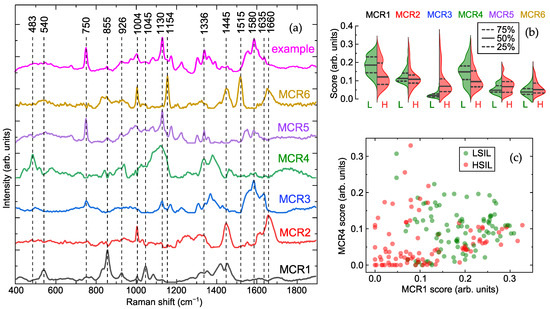

Figure 1a demonstrates six major components resolved from the Raman spectra acquired at 532-nm excitation. Based on comparisons with our database and literature [19,26], the characteristic bands of MCR1 at 540, 830, 855, 926, 1045, 1088, 1420, and 1455 coincide with the main bands in the spectra of lactate/lactic acid. Possible correspondences of Raman bands and functional groups are listed in Table S1, and a comparison of the spectral profiles of the MCR components with Raman spectra from the literature is presented in Figures S1–S4 in Supplementary Materials. Next, the spectral composition of MCR2 and MCR6 is close to the typical Raman spectra of proteins, featuring the aromatic ring breathing mode and Amide bands at 1004, 1445, and 1660 [19,27,28]; however, MCR6 also demonstrates prominent carotenoid bands at 1004, 1154, and 1515 [29,30,31] and may additionally be affected by lipoprotein content [32]. Many vibration bands presented in MCR3 and MCR5 can be associated with heme proteins (e.g., hemoglobin and myoglobin), namely 750, 1130, 1225, 1305, 1336, 1360, 1555, 1585, and 1635 [33,34]. Finally, MCR4 can be tentatively identified as glycogen, showing related bands at 483, 575, 853, 940, 1080, 1128, 1336, 1382, and 1457 [14,35,36].

Figure 1.

Results of multivariate curve resolution (MCR) analysis: (a) example of acquired Raman spectrum and six components obtained by MCR analysis with their major Raman bands, (b) half-violin plots indicating scores of these components for low- (LSIL, L) and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL, H) samples with median (50%) and quartile (25%, 75%) levels, and (c) distribution of scores for first (MCR1) and fourth (MCR4) components.

Analysis of the component scores (Figure 1b) revealed elevated levels of MCR3 and MCR5 (heme proteins) in most HSIL samples, which were low or absent in LSIL. Additionally, MCR1 (lactate/lactic acid) and MCR4 (glycogen) were markedly reduced in the HSIL group compared to LSIL, while MCR2 content remained consistent across the groups. The distribution of MCR1 ( lactate/lactic acid) and MCR4 (glycogen) scores (Figure 1c) showed a clear separation between LSIL and HSIL. Using quadratic discriminant analysis (QDA) on these two components, differentiation between LSIL and HSIL achieved a sensitivity of 60% and specificity of 78% for HSIL detection (for the test set; corresponding values for the training set were 61% and 80%). Incorporating heme-related components (MCR3 and MCR5) increased specificity to 88% while maintaining sensitivity at 62% (93% and 63% for the training set). However, further improving sensitivity without substantial loss of specificity remains challenging. Despite the effective identification of spectral differences between the groups, the hypothetical nature of the proposed biochemical interpretations should be emphasized.

2.2. Optimal Spectral Ratios for Differentiating Cervical Lesions via Raman Spectroscopy

To identify optimal spectral criteria for differentiating between LSIL and HSIL samples, we analyzed all detected Raman bands individually, representing each spectrum as an array I of its peak intensities. Each band was iteratively treated as a reference (see Section 4), and all possible pairs of intensity ratios were examined. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for the QDA classifier were computed for each pair to compare specificity at a target sensitivity. The most robust classification was achieved using as the denominator in all ratios, as this band–associated with aromatic ring breathing of phenylalanine in proteins [27]–served as a stable reference due to consistent protein content across both sample groups.

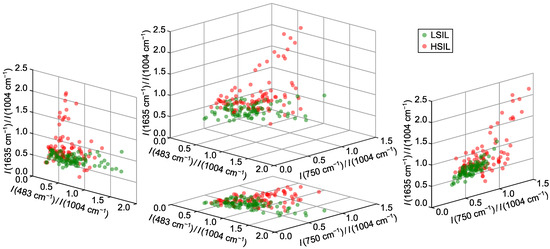

According to the results of the tests, three best spectral ratios were identified as , and . These ratios collectively provided an overall true positive rate (TPR) of 82%, with a specificity of 86% (90% for the training set) and sensitivity of 80% (fixed value). The peak at 483 , present in the glycogen-associated MCR4 component [14,36,37,38], resulted in a higher ratio for LSIL samples, as confirmed by distribution analysis (Figure 2). The band at 750 , linked to the CH–N–C breathing stretch in porphyrin rings, served as a blood marker in HSIL samples [39]. The ratio was primarily influenced by heme proteins (band at 1635 [33]), with minimal contribution from the Amide I protein band [40] due to normalization at 1004 .

Figure 2.

Distributions of normalized intensity values (intensity ratios) for three selected Raman bands at 532 nm excitation wavelength providing differentiation between LSIL and HSIL samples.

Classification was driven mainly by the bands at 750 and 1635 , which showed increased intensity in HSIL samples and alone achieved 75% specificity at 80% sensitivity. Incorporating improved results by distinguishing HSIL samples with low heme content from LSIL via reduced glycogen levels; comparable results were observed for other glycogen or lactate bands. Using more than three ratios did not yield significant improvements, confirming the optimality of the selected criteria.

3. Discussion

This study pioneers the application of Raman spectroscopy to cell-free CVL for distinguishing between LSIL and HSIL in patients with HPV infection. Using MCR analysis and further validation through the analysis of specific Raman bands, we indicated key spectral differences between the groups of samples and associated them with the possible constituents of CVL identified as lactate/lactic acid, general proteins, heme proteins and glycogen. This approach aligns with and significantly expands upon earlier forensic-oriented work by Sikirzhytskaya et al. [19], who used factor analysis to decompose Raman spectra of vaginal fluid into similar constituents, including lactic acid and proteins, yet did not explore its diagnostic potential for cervical precancer.

Our comparative analysis revealed statistically significant biochemical shifts between LSIL and HSIL groups: the characteristic Raman peaks of glycogen and lactate/lactic acid were markedly reduced in HSIL samples, while the spectral features of heme proteins were substantially more intense. These changes reflect profound metabolic and microenvironmental alterations during cervical lesion progression. The observed glycogen depletion is clinically significant, as glycogen in healthy cervical epithelium supports a protective vaginal microbiome by fueling lactobacilli-produced lactic acid [41]. Its reduction in HSIL aligns with metabolic reprogramming, where glycogen is mobilized to fuel biosynthetic pathways [14]. Similar to processes in immune cells during inflammation, glycogen breakdown in precancerous cells supplies the pentose phosphate pathway for NADPH production, supporting proliferation, redox balance, and chemoresistance [42]. This reprogramming is a hallmark of the Warburg effect, with HPV-associated lesions exhibiting heightened glycolysis despite oxygen availability to meet energetic and anabolic demands [14,43,44,45].

Paradoxically, despite enhanced glycolysis, HSIL samples showed decreased lactate/lactic acid levels. This contrasts with typical cancer metabolism, where glycolytic flux increases lactate production and acidifies the microenvironment [45,46,47]. This discrepancy may be explained by the reverse Warburg effect [14,48], wherein cancer-associated stromal fibroblasts undergo aerobic glycolysis and export lactate, which is then imported by epithelial cancer cells via monocarboxylate transporters (e.g., MCT1) to fuel anabolic pathways [49]. Cancer cells can utilize lactate directly in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, demonstrating metabolic flexibility beyond glucose dependence [50,51,52]. Alternatively, reduced lactate may indicate a shift toward glutaminolysis, with glutamine replenishing TCA cycle intermediates under mitochondrial dysfunction [53,54].

The prominent presence of heme proteins in HSIL samples, evidenced by their characteristic bands (e.g., 750 and 1635 ), reflects the vascular nature of neoplastic tissues and associated microhemorrhages [11,18]. This aligns with previous studies detecting hemoglobin derivatives in biofluids as cancer markers [55]. These signals indicate pathological angiogenesis driven by vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and other pro-angiogenic factors [55,56,57]. As dysplasia advances, destruction of the basement membrane and tissue architecture increases fragility and bleeding risk [58]. Thus, heme detection in CVL via Raman spectroscopy serves not merely as an indicator of contamination but as a valuable non-invasive biomarker of active angiogenesis and structural disruption, signaling lesion progression and invasive potential.

We should note that the performed MCR analysis of the acquired Raman spectral data was aimed at detecting spectral differences between the samples and establishing their possible biochemical interpretation, rather than at identifying the exact chemical composition of the samples. The latter task requires validation using other methods of chemometric analysis and preparation of control samples with known concentrations of components for Raman measurements to develop a biochemical model of cell-free CVL and test its photochemical stability, which can be an important step towards the standardization of the proposed technique for integration into clinical practice.

The findings of our analysis were used to create a diagnostic model based on specific Raman peak intensity ratios. Effective differentiation between LSIL and HSIL was achieved using the ratios , , and , which leverage the metabolic and vascular changes described. The successful application of this strategy supports the potential of Raman spectroscopy as a complementary tool in cervical cancer screening, offering a rapid, non-invasive, cost-effective method to assess lesion severity based on underlying biochemical alterations.

These promising results must be interpreted within the study’s limitations, including a small sample size of only 20 patients, which limits statistical power and generalizability, the pilot design with potential selection bias, and the cross-sectional nature that cannot establish causality or predict progression from LSIL to HSIL over time. The performance metrics, while highly encouraging, require further confirmation with a larger set of samples, including double-blind testing for truly unseen data. While sample preparation minimizes cellular debris, confounding factors in the cervicovaginal microenvironment—such as microbiome variations or non-specific inflammation—may influence Raman spectra and require further investigation. To advance these findings, future work should validate the methodology in a larger, multi-center prospective cohort, include control groups of HPV-negative and HPV-positive women with normal cytology to define the full diagnostic range and triage capability, and explore correlations between Raman biomarkers and proteomic or metabolomic profiles to deepen molecular understanding. Technologically, efforts should streamline the protocol and develop automated, portable Raman systems for potential point-of-care use, with the goal of integrating the approach into existing cervical cancer screening algorithms.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sample Collection

The study included 20 women with a mean age of years (median 28 years; range 22–49) who were treated at the scientific and outpatient department of the National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology named after Academician V.I. Kulakov (Moscow, Russia) from January to March 2025. Inclusion criteria comprised reproductive age from 20 to 49 years, a regular menstrual cycle, histologically confirmed LSIL (CIN I) or HSIL (CIN II/III) with the presence of carcinogenic risk HPV, and an ability to comply with protocol requirements. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy, lactation, hormone therapy, acute inflammation, decompensated dysfunction of the kidneys, liver, or lungs, and psychoneurological conditions. The sample collection was preferentially scheduled during the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle. Based on histological examination of biopsy material, two groups were formed: LSIL () and HSIL ().

CVL samples were collected into 15 mL Falcon tubes after irrigating the vagina and cervix with a 5 mg/mL solution of sodium chloride 0.9% prior to routine procedures (biopsy for histological examination, etc.) to minimize blood contamination. Samples were centrifuged at 2000× g for 10 minutes at 4 °C. The resulting supernatant was aliquoted into three cryovials, each containing 1.5 mL of liquid, and frozen at −80 °C. Total processing and storage preparation time was under 30 min, with frozen samples stable for up to 3 years, preserving the biochemical composition for reliable Raman analysis [20,59,60,61,62]. Wide-spectrum HPV genotyping for 21 HPV types was performed using real-time polymerase chain reaction developed by DNK-Technologia (Moscow, Russia).

Extended colposcopy was performed using a Leisegang colposcope (Leisegang, Berlin, Germany) following the International Federation for Cervical Pathology and Colposcopy (IFCPC) Terminology (Rio de Janeiro, 2017) [63]. Histological verification used a two-level classification where mild epithelial dysplasia (CIN I) corresponds to LSIL, and moderate/severe cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN II/III) refers to HSIL.

4.2. Raman Spectroscopy

Before the spectral measurements, the CVL samples were allowed to thaw at room temperature (25 °C). A small aliquot of each sample (5–10 µL) was deposited onto a glass slide coated with aluminum and permitted to dry completely, which is a preferential setup for intense Raman signal with lower background fluorescence [64]. The spectra were acquired with a Confotec MR520 confocal microscope-spectrometer (SOL Instruments, Minsk, Belarus) using 532 nm laser excitation (20 mW power in the sample plane and a maximum accumulation time of 10 s) and a 40× objective lens MPlanFL (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) with a numerical aperture of 0.75. The spectral profiles remained stable for different exposure times (1–10 s), which indicated photochemical stability and repeatability under the given measurement conditions. According to the specifications provided by the manufacturers, the spectral resolution was in the range from 1 to 1.5 . In total, 15–20 spectra were obtained at random points of each sample at room temperature under equal conditions.

4.3. Raman Data Processing and Analysis

The acquired spectra were preprocessed using the MATLAB (R2022b, MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) implementations of the Vancouver Raman Algorithm [31,65,66] to remove fluorescence background with a modified multi-polynomial baseline fitting and the Savitzky–Golay filter to reduce noise. Subsequently, MCR analysis [23,24,25] was performed via a non-negative matrix factorization algorithm with an alternating least squares (ALS) approach (built-in MATLAB functions). In our study, the MCR-ALS analysis was applied to the processed Raman spectra of all CVL samples normalized by their mean value, and the optimal number of interpretable components was identified as six by means of monitoring a decrease in residual error with increasing number of components and checking the results for duplicates. Possible assignments for each MCR component and its major spectral bands were found using comparison with Open Raman spectral library [36], our collected Raman spectra database of biomolecules, and data from various literature sources.

To evaluate the suitability of various spectral features for distinguishing CVL samples as LSIL vs. HSIL, we replaced each spectrum with an array I of its peak intensities (e.g., ) in the main Raman bands, the list of which was formed as a result of the aforementioned analysis. For the calculation of the classification rates, we sequentially tested all possible normalizations by selecting one band as the reference, for example , and dividing the intensities of the other bands by it to form an array of ratios, such as , , and so on [25]. Next, we used the QDA in MATLAB Classification Learner with default settings to compute the ROC curve for each pair of ratios in the array and evaluate the specificity at 80% sensitivity as the criterion for selecting the best pair of ratios. The results presented in the article correspond to the average values for the test set (or the training set, if specified) of 5-fold stratified cross-validation with 10 repetitions to avoid model overfitting [67]. The spectra of each sample (belonging to one patient) were included into only one subset [68]. All data processing algorithms were implemented by the authors as custom MATLAB scripts, unless otherwise stated.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study establishes that Raman spectroscopy of CVL provides a powerful, non-invasive window into the profound biochemical transformations underpinning HPV-associated cervical carcinogenesis. The noticeable spectral differences can be interpreted as markers of pathophysiological changes—including glycogen depletion, altered lactate/lactic acid dynamics and microvascular alterations evidenced by elevated heme proteins—which collectively form a composite signature of neoplastic progression. This approach demonstrates high sensitivity and specificity in distinguishing HSIL from LSIL (80% and 86%, respectively), showcasing its strong potential to overcome the key limitations of conventional diagnostics, namely the subjectivity of cytology and the invasiveness of biopsy. By offering a rapid and objective molecular assessment, Raman spectroscopy of CVL could significantly enhance risk stratification and facilitate personalized clinical management. While these pilot findings are highly promising, their translation into clinical practice necessitates further validation through larger, prospective multi-center studies to confirm efficacy and integrate this innovative methodology into standardized screening algorithms.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms262211064/s1. References [14,19,26,27,29,33,34,35,36,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94] are cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.R., A.G. and N.N.; methodology, E.R., A.G., N.S. and N.N.; software, E.R. and A.G.; validation, E.R., A.G., N.N. and V.P.; formal analysis, E.R., A.G., N.N., A.D. and N.S.; investigation, E.R., A.G., N.N. and A.D.; resources, A.D., N.N., P.A. and A.M.; data curation, E.R., A.G., A.D. and N.N.; writing—original draft preparation, E.R., A.G., N.N., A.D. and N.S.; writing—review and editing, E.R., A.G., N.N., A.D., N.S., P.A. and A.M.; visualization, E.R., A.G. and A.D.; supervision, N.N. and V.P.; project administration, N.N., V.P., S.K. and N.S.; funding acquisition, V.P. and G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the state assignment of the Ministry of Healthcare of the Russian Federation (Registration No. 12503063216-9 “Development of a test system for early and minimally invasive diagnostics of HPV- associated precancerous and oncological diseases of the anogenital area in women of different ages using liquid biopsy”).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, named after Academician V.I. Kulakov (Moscow, Russia, protocol code 1 of 30 January 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the laboratory for the collection and storage of biological material (Biobank) for providing tissue samples. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kim, Y.H.; Chang, B.; Choi, J.H.; Park, H.K.; Choi, S. Biochemical fingerprints of human papillomavirus infection and cervical dysplasia using cervical fluids: Spectral pattern investigation. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2016, 79, 966–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, R.; Daniel, A.; Lyng, F.M. Raman Spectroscopy for Early Detection of Cervical Cancer, a Global Women’s Health Issue—A Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guideline for Screening and Treatment of Cervical Pre-Cancer Lesions for Cervical Cancer Prevention: Use of Dual-Stain Cytology to Triage Women After a Positive Test for Human Papillomavirus (HPV); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- Espinoza, H.; Ha, K.T.; Pham, T.T.; Espinoza, J.L. Genetic Predisposition to Persistent Human Papillomavirus-Infection and Virus-Induced Cancers. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, K.R.; Cantor, S.B.; Cox, D.D.; Follen, M. An Alternative Approach for Estimating the Accuracy of Colposcopy in Detecting Cervical Precancer. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0126573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Shivani, u.; Zutshi, V.; Yadav, A.K. Role of Multiple Cervical Biopsies on Colposcopy for the Detection of Premalignant and Malignant Lesions of the Cervix. J. Colposc. Low. Genit. Tract Pathol. 2024, 2, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariprasad, R.; Mittal, S.; Basu, P. Role of colposcopy in the management of women with abnormal cytology. Cytojournal 2021, 19, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guideline for Screening and Treatment of Cervical Pre-Cancer Lesions for Cervical Cancer Prevention, 2nd ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; pp. xvi, 97.

- Liu, M.; Lu, J.; Zhi, Y.; Ruan, Y.; Cao, G.; Xu, X.; An, X.; Gao, J.; Li, F. Microendoscopy in vivo for the pathological diagnosis of cervical precancerous lesions and early cervical cancer. Infect. Agents Cancer 2023, 18, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Yang, D.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Cui, Z.; Wang, C.; Qiao, Y. Clinical value of optical coherence tomography in the early diagnosis of cervical cancer and precancerous lesions: A cross-sectional study. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1423128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starodubtseva, N.L.; Brzhozovskiy, A.G.; Bugrova, A.E.; Kononikhin, A.S.; Indeykina, M.I.; Gusakov, K.I.; Chagovets, V.V.; Nazarova, N.M.; Frankevich, V.E.; Sukhikh, G.T.; et al. Label-free cervicovaginal fluid proteome profiling reflects the cervix neoplastic transformation. J. Mass Spectrom. 2019, 54, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza Leão, L.Q.; de Andrade, J.C.; Marques, G.M.; Guimarães, C.C.; de Fátima Vieira de Albuquerque, R.; e Silva, A.S.; de Araujo, K.P.; de Oliveira, M.P.; Gonçalves, A.F.; Figueiredo, H.F.; et al. Rapid prediction of cervical cancer and high-grade precursor lesions: An integrated approach using low-field 1H NMR and chemometric analysis. Clin. Chim. Acta 2025, 574, 120346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traynor, D.; Martin, C.M.; White, C.; Reynolds, S.; D’Arcy, T.; O’Leary, J.J.; Lyng, F.M. Raman Spectroscopy of Liquid-Based Cervical Smear Samples as a Triage to Stratify Women Who Are HPV-Positive on Screening. Cancers 2021, 13, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitarz, K.; Czamara, K.; Bialecka, J.; Klimek, M.; Zawilinska, B.; Szostek, S.; Kaczor, A. HPV Infection Significantly Accelerates Glycogen Metabolism in Cervical Cells with Large Nuclei: Raman Microscopic Study with Subcellular Resolution. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargis, E.; Tang, Y.W.; Khabele, D.; Mahadevan-Jansen, A. Near-infrared Raman Microspectroscopy Detects High-risk Human Papillomaviruses. Transl. Oncol. 2012, 5, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duraipandian, S.; Zheng, W.; Ng, J.; Low, J.J.; Ilancheran, A.; Huang, Z. Near-infrared-excited confocal Raman spectroscopy advances in vivo diagnosis of cervical precancer. J. Biomed. Opt. 2013, 18, 067007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barik, A.K.; M, S.P.; N, M.; Pai, M.V.; Upadhya, R.; Pai, A.K.; Lukose, J.; Chidangil, S. A micro-Raman spectroscopy study of inflammatory condition of human cervix: Probing of tissues and blood plasma samples. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2022, 39, 102948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubina, S.; Amita, M.; Kedar K., D.; Bharat, R.; Krishna, C.M. Raman spectroscopic study on classification of cervical cell specimens. Vib. Spectrosc. 2013, 68, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikirzhytskaya, A.; Sikirzhytski, V.; Lednev, I.K. Raman spectroscopic signature of vaginal fluid and its potential application in forensic body fluid identification. Forensic Sci. Int. 2012, 216, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikirzhytskaya, A.; Sikirzhytski, V.; Pérez-Almodóvar, L.; Lednev, I.K. Raman spectroscopy for the identification of body fluid traces: Semen and vaginal fluid mixture. Forensic Chem. 2023, 32, 100468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, N.; Singh, H.; Jotaniya, R.; Pandya, S.R. Raman spectroscopy for the determination of forensically important bio-fluids. Forensic Sci. Int. 2022, 340, 111441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Park, H.K.; Min, G.E.; Kim, Y.H. Biochemical investigations of human papillomavirus-infected cervical fluids. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2015, 78, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matveeva, I.; Bratchenko, I.; Khristoforova, Y.; Bratchenko, L.; Moryatov, A.; Kozlov, S.; Kaganov, O.; Zakharov, V. Multivariate Curve Resolution Alternating Least Squares Analysis of In Vivo Skin Raman Spectra. Sensors 2022, 22, 9588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakimov, B.P.; Venets, A.V.; Schleusener, J.; Fadeev, V.V.; Lademann, J.; Shirshin, E.A.; Darvin, M.E. Blind source separation of molecular components of the human skin in vivo: Non-negative matrix factorization of Raman microspectroscopy data. Analyst 2021, 146, 3185–3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimskaya, E.; Gorevoy, A.; Yakimova, A.; Makarova, N.; Starodubtseva, N.; Kudryashov, S.; Nazarenko, R.; Kalinina, E.; Frankevich, V.; Sukhikh, G. Enhancing male fertility diagnostics with seminal plasma Raman spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta Part Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2025, 340, 126237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angle, K.J.; Nowak, C.M.; Grassian, V.H. Organic acid evaporation kinetics from aqueous aerosols: Implications for aerosol buffering capacity in the atmosphere. Environ. Sci. Atmos. 2023, 3, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rygula, A.; Majzner, K.; Marzec, K.M.; Kaczor, A.; Pilarczyk, M.; Baranska, M. Raman spectroscopy of proteins: a review. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2013, 44, 1061–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krafft, C. Raman Spectroscopy of Proteins and Nucleic Acids: From Amino Acids and Nucleotides to Large Assemblies. In Encyclopedia of Analytical Chemistry, 1st ed.; Meyers, R.A., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvin, M.E.; Sterry, W.; Lademann, J.; Vergou, T. The Role of Carotenoids in Human Skin. Molecules 2011, 16, 10491–10506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.F.; Tavender, S.M.; Dixon, N.M.; Herman, H.; Williams, K.P.J.; Maddams, W.F. Raman Spectrum of beta-Carotene Using Laser Lines from Green (514.5 nm) to Near-Infrared (1064 nm): Implications for the Characterization of Conjugated Polyenes. Appl. Spectrosc. 1999, 53, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimskaya, E.; Gorevoy, A.; Shelygina, S.; Perevedentseva, E.; Timurzieva, A.; Saraeva, I.; Melnik, N.; Kudryashov, S.; Kuchmizhak, A. Multi-Wavelength Raman Differentiation of Malignant Skin Neoplasms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricciardi, A.; Piuri, G.; Porta, M.D.; Mazzucchelli, S.; Bonizzi, A.; Truffi, M.; Sevieri, M.; Allevi, R.; Corsi, F.; Cazzola, R.; et al. Raman spectroscopy characterization of the major classes of plasma lipoproteins. Vib. Spectrosc. 2020, 109, 103073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlawat, S.; Kumar, N.; Uppal, A.; Kumar Gupta, P. Visible Raman excitation laser induced power and exposure dependent effects in red blood cells. J. Biophotonics 2017, 10, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grytsyk, N.; Boubegtiten-Fezoua, Z.; Javahiraly, N.; Omeis, F.; Devaux, E.; Hellwig, P. Surface-enhanced resonance Raman spectroscopy of heme proteins on a gold grid electrode. Spectrochim. Acta Part Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2020, 230, 118081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiercigroch, E.; Szafraniec, E.; Czamara, K.; Pacia, M.Z.; Majzner, K.; Kochan, K.; Kaczor, A.; Baranska, M.; Malek, K. Raman and infrared spectroscopy of carbohydrates: A review. Spectrochim. Acta Part Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2017, 185, 317–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terán, M.; Ruiz, J.J.; Loza-Alvarez, P.; Masip, D.; Merino, D. Open Raman spectral library for biomolecule identification. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2025, 264, 105476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Du, J.; Yu, R.; Su, Y.; Heath, J.R.; Wei, L. Visualizing Subcellular Enrichment of Glycogen in Live Cancer Cells by Stimulated Raman Scattering. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 13182–13191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopec, M.; Imiela, A.; Abramczyk, H. Monitoring glycosylation metabolism in brain and breast cancer by Raman imaging. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.; Bálint, Š.; Cossins, B.; Guallar, V.; Petrov, D. Raman Study of Mechanically Induced Oxygenation State Transition of Red Blood Cells Using Optical Tweezers. Biophys. J. 2009, 96, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talari, A.C.S.; Movasaghi, Z.; Rehman, S.; Rehman, I.U. Raman Spectroscopy of Biological Tissues. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2015, 50, 46–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirmonsef, P.; Hotton, A.L.; Gilbert, D.; Gioia, C.J.; Maric, D.; Hope, T.J.; Landay, A.L.; Spear, G.T. Glycogen Levels in Undiluted Genital Fluid and Their Relationship to Vaginal pH, Estrogen, and Progesterone. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, T.; Sullivan, M.A.; Gunter, J.H.; Kryza, T.; Lyons, N.; He, Y.; Hooper, J.D. Revisiting Glycogen in Cancer: A Conspicuous and Targetable Enabler of Malignant Transformation. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 592455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arizmendi-Izazaga, A.; Navarro-Tito, N.; Jiménez-Wences, H.; Mendoza-Catalán, M.A.; Martínez-Carrillo, D.N.; Zacapala-Gómez, A.E.; Olea-Flores, M.; Dircio-Maldonado, R.; Torres-Rojas, F.I.; Soto-Flores, D.G.; et al. Metabolic Reprogramming in Cancer: Role of HPV 16 Variants. Pathogens 2021, 10, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Wang, F.; Zhou, K.; Huang, K.; Zhu, Q.; Luo, X.; Yu, J.; Shi, Z. Oncogenic role of ABHD5 in endometrial cancer. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 2139–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Yao, Z.; Ma, L.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Li, L.; Liu, C. Glucose metabolism reprogramming in gynecologic malignant tumors. J. Cancer 2024, 15, 2627–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucino, V.; Bombardieri, M.; Pitzalis, C.; Mauro, C. Lactate at the crossroads of metabolism, inflammation, and autoimmunity. Eur. J. Immunol. 2017, 47, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walenta, S.; Wetterling, M.; Lehrke, M.; Schwickert, G.; Sundfør, K.; Rofstad, E.; Mueller-Klieser, W. High lactate levels predict likelihood of metastases, tumor recurrence, and restricted patient survival in human cervical cancers. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 916–921. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlides, S.; Whitaker-Menezes, D.; Castello-Cros, R.; Flomenberg, N.; Witkiewicz, A.; Frank, P.; Casimiro, M.; Wang, C.; Fortina, P.; Addya, S.; et al. The reverse Warburg effect: Aerobic glycolysis in cancer associated fibroblasts and the tumor stroma. Cell Cycle 2009, 8, 3984–4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halestrap, A.P. Monocarboxylic Acid Transport. Compr. Physiol. 2013, 3, 1611–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montal, E.D.; Bhalla, K.; Dewi, R.E.; Ruiz, C.F.; Haley, J.A.; Ropell, A.E.; Gordon, C.; Haley, J.D.; Girnun, G.D. Inhibition of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase blocks lactate utilization and impairs tumor growth in colorectal cancer. Cancer Metab. 2019, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, S.; Ghergurovich, J.M.; Morscher, R.J.; Jang, C.; Teng, X.; Lu, W.; Esparza, L.A.; Reya, T.; Zhan, L.; Yanxiang Guo, J.; et al. Glucose feeds the TCA cycle via circulating lactate. Nature 2017, 551, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajnani, K.; Islam, F.; Smith, R.A.; Gopalan, V.; Lam, A.K.Y. Genetic alterations in Krebs cycle and its impact on cancer pathogenesis. Biochimie 2017, 135, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Copeland, C.; Le, A. Glutamine Metabolism in Cancer. In The Heterogeneity of Cancer Metabolism; Le, A., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, A.R.; Wheaton, W.W.; Jin, E.S.; Chen, P.H.; Sullivan, L.B.; Cheng, T.; Yang, Y.; Linehan, W.M.; Chandel, N.S.; DeBerardinis, R.J. Reductive carboxylation supports growth in tumour cells with defective mitochondria. Nature 2012, 481, 385–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eskander, R.N.; Tewari, K.S. Targeting angiogenesis in advanced cervical cancer. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2014, 6, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minion, L.E.; Tewari, K.S. Cervical cancer – State of the science: From angiogenesis blockade to checkpoint inhibition. Gynecol. Oncol. 2018, 148, 609–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomao, F.; Papa, A.; Rossi, L.; Zaccarelli, E.; Caruso, D.; Zoratto, F.; Panici, P.B.; Tomao, S. Angiogenesis and antiangiogenic agents in cervical cancer. Oncotargets Ther. 2014, 7, 2237–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Wang, S.; Zhang, X.; Han, Y.; Tan, M.; Fan, J.; Du, J.; Fan, Y.; Zhao, X. The biomechanical signature of tumor invasion. Genes Dis. 2025, 13, 101771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betsou, F.; Lehmann, S.; Ashton, G.; Barnes, M.; Benson, E.E.; Coppola, D.; DeSouza, Y.; Eliason, J.; Glazer, B.; Guadagni, F.; et al. Standard Preanalytical Coding for Biospecimens: Defining the Sample PREanalytical Code. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2010, 19, 1004–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandes, V.V.; Barbas, C.; Dudzik, D. A review of blood sample handling and pre-processing for metabolomics studies. Electrophoresis 2017, 38, 2232–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellervik, C.; Vaught, J. Preanalytical Variables Affecting the Integrity of Human Biospecimens in Biobanking. Clin. Chem. 2015, 61, 914–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, G.; Gajer, P.; Nandy, M.; Ma, B.; Yang, H.; Sakamoto, J.; Blanchard, M.; Ravel, J.; Brotman, R. Comparison of Storage Conditions for Human Vaginal Microbiome Studies. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e36934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petry, K.U.; Nieminen, P.J.; Leeson, S.C.; Bergeron, C.O.; Redman, C.W. 2017 update of the European Federation for Colposcopy (EFC) performance standards for the practice of colposcopy. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2018, 224, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borisov, A.V.; Snegerev, M.S.; Colón-Rodríguez, S.; Fikiet, M.A.; Lednev, I.K.; Kistenev, Y.V. Identification of semen traces at a crime scene through Raman spectroscopy and machine learning. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Lui, H.; McLean, D.I.; Zeng, H. Automated autofluorescence background subtraction algorithm for biomedical Raman spectroscopy. Appl. Spectrosc. 2007, 61, 1225–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Lui, H.; McLean, D.I.; Zeng, H. Real-Time Raman Spectroscopy for Noninvasive in vivo Skin Analysis and Diagnosis. In New Developments in Biomedical Engineering; Campolo, D., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2010; Chapter 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratchenko, L.; Bratchenko, I. Avoiding Overestimation and the ‘Black Box’ Problem in Biofluids Multivariate Analysis by Raman Spectroscopy: Interpretation and Transparency With the SP-LIME Algorithm. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2025, 56, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratchenko, L.A.; Khristoforova, Y.A.; Pimenova, I.A.; Tupikova, E.N.; Skuratova, M.A.; Dvoynikov-Sechnoy, G.A.; Wang, S.; Lebedev, P.A.; Bratchenko, I.A. SERS-based technique for accessible and rapid diagnosis of multiple myeloma in blood serum analysis. Light. Adv. Manuf. 2025, 6, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczyk, A.; Tipping, W.; Mazuryk, O.; Graham, D.; Baranska, M.; Majzner, K. Sensitive Detection and Identification Method of Erythrocyte-like Cells upon Doxorubicin Induced Differentiation with Vibrational Techniques. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 16966–16974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyng, F.; Faoláin, E.; Conroy, J.; Meade, A.; Knief, P.; Duffy, B.; Hunter, M.; Byrne, J.; Kelehan, P.; Byrne, H. Vibrational spectroscopy for cervical cancer pathology, from biochemical analysis to diagnostic tool. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2007, 82, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Movasaghi, Z.; Rehman, S.; Rehman, I.U. Raman Spectroscopy of Biological Tissues. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2007, 42, 493–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konorov, S.O.; Schulze, H.G.; Piret, J.M.; Turner, R.F.B.; Blades, M.W. Evidence of marked glycogen variations in the characteristic Raman signatures of human embryonic stem cells. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2011, 42, 1135–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaetxea, I.; Valero, A.; Lopez, E.; Lafuente, H.; Izeta, A.; Jaunarena, I.; Seifert, A. Machine Learning-Assisted Raman Spectroscopy for pH and Lactate Sensing in Body Fluids. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 13888–13895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golparvar, A.; Boukhayma, A.; Loayza, T.; Caizzone, A.; Enz, C.; Carrara, S. Very Selective Detection of Low Physiopathological Glucose Levels by Spontaneous Raman Spectroscopy with Univariate Data Analysis. BioNanoScience 2021, 11, 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gelder, J.; De Gussem, K.; Vandenabeele, P.; Moens, L. Reference database of Raman spectra of biological molecules. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2007, 38, 1133–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golparvar, A.; Kim, J.; Boukhayma, A.; Briand, D.; Carrara, S. Highly accurate multimodal monitoring of lactate and urea in sweat by soft epidermal optofluidics with single-band Raman scattering. Sens. Actuators Chem. 2023, 387, 133814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlasov, A.V.; Maliar, N.L.; Bazhenov, S.V.; Nikelshparg, E.I.; Brazhe, N.A.; Vlasova, A.D.; Osipov, S.D.; Sudarev, V.V.; Ryzhykau, Y.L.; Bogorodskiy, A.O.; et al. Raman Scattering: From Structural Biology to Medical Applications. Crystals 2020, 10, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Zhu, X.; Fan, Q.; Wan, X. Raman spectra of amino acids and their aqueous solutions. Spectrochim. Acta Part Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2011, 78, 1187–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimskaya, E.; Shelygina, S.; Timurzieva, A.; Saraeva, I.; Perevedentseva, E.; Melnik, N.; Kudrin, K.; Reshetov, D.; Kudryashov, S. Multispectral Raman Differentiation of Malignant Skin Neoplasms In Vitro: Search for Specific Biomarkers and Optimal Wavelengths. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synytsya, A.; Judexova, M.; Hoskovec, D.; Miskovicova, M.; Petruzelka, L. Raman spectroscopy at different excitation wavelengths (1064, 785 and 532 nm) as a tool for diagnosis of colon cancer. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2014, 45, 903–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergholt, M.S.; Zheng, W.; Lin, K.; Huang, Z.; Ho, K.Y.; Yeoh, K.G.; Teh, M.; So, J.B.Y. Characterizing variability in in vivo Raman spectra of different anatomical locations in the upper gastrointestinal tract toward cancer detection. J. Biomed. Opt. 2011, 16, 037003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, L.; Tang, J.; Wu, J.; Shang, H.; Huang, X.; Bao, Y.; Xu, Z.; Wang, H.; Yin, J. Polarized Micro-Raman Spectroscopy and 2D Convolutional Neural Network Applied to Structural Analysis and Discrimination of Breast Cancer. Biosensors 2023, 13, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udensi, J.; Loughman, J.; Loskutova, E.; Byrne, H.J. Raman Spectroscopy of Carotenoid Compounds for Clinical Applications—A Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 9017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tfaili, S.; Gobinet, C.; Josse, G.; Angiboust, J.F.; Manfait, M.; Piot, O. Confocal Raman microspectroscopy for skin characterization: a comparative study between human skin and pig skin. Analyst 2012, 137, 3673–3682, Correction in Analyst 2020, 145, 4699–4700. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0AN90060E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, D.; Lin, J.; Wu, Y.; Feng, S.; Li, Y.; Yu, Y.; Xi, G.; Zeng, H.; Chen, R. Investigation on the interactions of lymphoma cells with paclitaxel by Raman spectroscopy. Spectroscopy 2011, 25, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramczyk, H.; Brozek-Pluska, B.; Kopec, M.; Surmacki, J.; Błaszczyk, M.; Radek, M. Redox Imbalance and Biochemical Changes in Cancer by Probing Redox-Sensitive Mitochondrial Cytochromes in Label-Free Visible Resonance Raman Imaging. Cancers 2021, 13, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, S.; Da Costa, R.; Wübbeling, F.; Redmann, K.; Schlatt, S. Raman micro-spectroscopy analysis of different sperm regions: a species comparison. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2017, 24, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; Moy, A.J.; Nguyen, H.T.M.; Zhang, J.; Fox, M.C.; Sebastian, K.R.; Reichenberg, J.S.; Markey, M.K.; Tunnell, J.W. Raman active components of skin cancer. Biomed. Opt. Express 2017, 8, 2835–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czamara, K.; Majzner, K.; Pacia, M.Z.; Kochan, K.; Kaczor, A.; Baranska, M. Raman spectroscopy of lipids: a review. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2015, 46, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, L.; Sathaiah, S.; Zângaro, R.A.; Pacheco, M.T.T.; Chavantes, M.C.; Pasqualucci, C.A.G. Correlation between near-infrared Raman spectroscopy and the histopathological analysis of atherosclerosis in human coronary arteries. Lasers Surg. Med. 2002, 30, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; McWilliams, A.; Lui, H.; McLean, D.I.; Lam, S.; Zeng, H. Near-infrared Raman spectroscopy for optical diagnosis of lung cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2003, 107, 1047–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gniadecka, M.; Wulf, H.C.; Nymark Mortensen, N.; Faurskov Nielsen, O.; Christensen, D.H. Diagnosis of Basal Cell Carcinoma by Raman Spectroscopy. J. Raman Spectrosc. 1997, 28, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadevan-Jansen, A.; Richards-Kortum, R.R. Raman spectroscopy for the detection of cancers and precancers. J. Biomed. Opt. 1996, 1, 31–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ChemicalBook. Sodium Lactate (312-85-6). Available online: https://www.chemicalbook.com/SpectrumEN_312-85-6_Raman.htm (accessed on 6 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).