Abstract

Spermatogenesis is a highly coordinated process that requires the precise expression of specific subsets of genes in different types of germ cells, controlled both temporally and spatially. Among these genes, those that can exert an indispensable influence in spermatogenesis via participating in alternative splicing make up the overwhelming majority. mRNA alternative-splicing (AS) events can generate various isoforms with distinct functions from a single DNA sequence, based on specific AS codes. In addition to enhancing the finite diversity of the genome, AS can also regulate the transcription and translation of certain genes by directly binding to their cis-elements or by recruiting trans-elements that interact with consensus motifs. The testis, being one of the most complex tissue transcriptomes, undergoes unparalleled transcriptional and translational activity, supporting the dramatic and dynamic transitions that occur during spermatogenesis. Consequently, AS plays a vital role in producing an extensive array of transcripts and coordinating significant changes throughout this process. In this review, we summarize the intricate functional network of alternative splicing in spermatogenesis based on the integration of current research findings.

1. Introduction

Currently, infertility poses a significant public health challenge, affecting one in eight couples, with approximately half of infertility cases attributed to male factors [1,2,3]. The prevalence of infertility among men is reported to be around 12%, often resulting from secondary hypogonadism, obstructive azoospermia, or testicular dysfunction [4]. In this manuscript, we shed light on one of the major factors in testicular dysfunction—genetic anomalies. Numerous genes work collaboratively during spermatogenesis, where specific genetic disturbances lead to distinct molecular and cellular processes, yet similar phenotypes manifest as nonobstructive azoospermia [5].

Spermatogenesis, a meticulously orchestrated process that produces male gametes, generally can be divided into three phases: the maintenance and differentiation of spermatogonia, meiotic division of spermatocytes, and maturation of haploid gametes. Before releasing mature sperm into the epididymis, the cells with testes undergo significant transcriptional and translational dynamics [6]. Alternative splicing (AS) plays a crucial role in male gamete biogenesis, contributing to the sophisticated molecular activities that result in one of the most complex tissue transcriptomes. The long-held notion of “one gene, one polypeptide” has been challenged; AS significantly increases the diversity and complexity of the transcriptome and proteome derived from a finite genome [7,8]. Recent advancements in high-throughput sequencing have identified numerous transcript variants and several modes of alternative splicing. The five major modes of AS include exon skipping, intron retention, mutually exclusive exons, alternative 5′ splice sites, and alternative 3′ splice sites, which collectively explain why the number of proteins exceeds the number of protein-coding genes [9]. In the human genome, 21,144 multiexonic protein-coding genes can generate 215,170 isoforms, averaging 3.4 isoforms per gene [10]. Approximately 95% of multiexon genes undergo splicing in humans, compared to around 63% in mice [10]. Approximately 95% of multiexon genes undergo splicing in humans, compared to around 63% in mice [11,12,13]. Any alteration in the intrinsic alternative splicing of genes—such as aberrant AS events—can impact mRNA stability, translation, and localization [14].

In this review, we synthesize recent research on alternative splicing to elucidate its role in male spermatogenesis (Table 1). We explore the interplay between AS regulators and various testis-specific key factors that contribute to the production of mature haploid gametes, as well as how dysregulation of AS can lead to male infertility and other human diseases.

Table 1.

Gene mutations and its specific roles in spermatogenesis dependent on AS.

2. The Mechanism of Alternative Splicing and Related Functional Pathways

2.1. How Alternative Splicing Works During the Molecular Biological Process

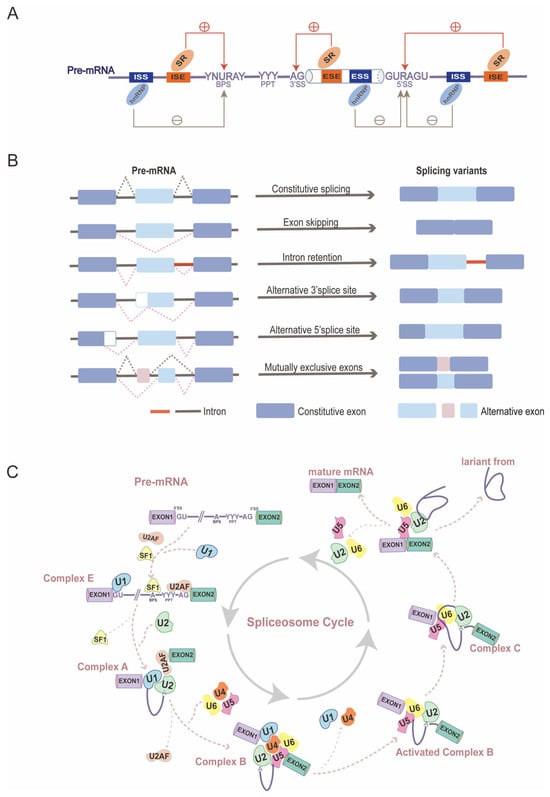

Once RNA polymerase II initiates binding to the DNA template, RNA synthesis begins, resulting in the transcription of genes into precursor messenger RNAs (pre-mRNAs) that contain intron-interrupted coding sequences [48]. For pre-mRNAs to mature into functional mRNAs, introns must be excised, and exons must be joined together, a process catalyzed by specific nucleotide sequences and spliceosomes [49]. The spliceosome, which is central to the mechanism of alternative splicing, is a macromolecular ribonucleoprotein complex composed of five small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (U1, U2, U4, U5, and U6) along with various auxiliary proteins [50]. The complex process of alternative splicing can be visualized as a cycle of spliceosome’ s assembly and disassembly, which occurs repeatedly after each time an intron is excised from a pre-mRNA (Figure 1C). The main steps in the spliceosome cycle can be summarized broadly: in the first step, formation of complex E: U1 snRNP binds to the 5′ splice site, while splicing factor 1 (SF1) and U2 auxiliary factor (U2AF) attach to the branch point site (BPS) and polypyrimidine tract (PPT), respectively; secondly, U2 snRNPs (small nuclear ribonucleoproteins) then replace SF1 via base pairing, proceeding to complex A; thirdly, after the release of U2AF, the U4/U6/U5 tri-snRNP is recruited, forming a pre-catalytic spliceosome, known as complex B; next, U1 and U4 snRNP are released, activating the complex B; consequently, after two rounds of transesterification reactions, introns are folded into a lariat, two adjacent exons are joined, and snRNPs enter next cycle [14,51,52,53,54]. In addition to the splicing process itself, five major modes of alternative splicing deserve detailed mention: exon skipping, intron retention, mutually exclusive exons, alternative 5′ splice sites, and alternative 3′ splice sites (Figure 1B) [54].

Figure 1.

The mechanism of alternative splicing: (A) cis-acting splicing-regulatory elements (SREs) and trans-acting splicing factors. Abbreviation, exonic splicing enhancers (ESEs), silencers (ESSs), intronic splicing enhancers (ISEs), intronic splicing silencers (ISSs), serine/arginine-rich (SR) proteins, and heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs) [55]. (B) Consecutive splicing and five major modes of alternative splicing. (C) Spliceosome cycle [14].

2.2. Splicing Regulators in Alternative Splicing

Alternative splicing is regulated by the interplay between cis-acting splicing-regulatory elements (SREs) and trans-acting splicing factors [56]. cis-acting splicing-regulatory elements are consensus nucleotide sequences found in the exons and introns of pre-mRNA, determining the removal or retention of specific exons. These elements include binding sites for trans-acting factors and guide the assembly of spliceosomal complexes. cis-acting splicing-regulatory elements comprise exonic splicing enhancers (ESEs) and silencers (ESSs), as well as intronic splicing enhancers (ISEs) and silencers (ISSs) [55,57]. Trans-acting splicing factors comprise a vast group of RNA-binding proteins (RBPs), primarily including two families involved in the splicing process: serine/arginine-rich (SR) proteins and heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs). SR proteins are recruited by exonic splicing enhancers (ESEs) and intronic splicing enhancers (ISEs) to promote splicing, while hnRNPs bind to ISEs and intronic splicing silencers (ISSs) to inhibit splicing [58,59]. Typically, SR and hnRNP proteins exert opposing effects on the regulation of cellular RNA splicing (Figure 1A). Notably, many members of these two families have been identified as playing critical roles in spermatogenesis through mechanisms dependent on alternative splicing, which will be discussed in greater detail later [54,56,60,61].

2.3. Crosstalk Between Other RNA Alternative Splicing and Metabolism Regulators in Spermatogenesis

The fidelity of alternative splicing is under stringent scrutiny as it ensures the proper proteins production, which is indispensable for cell growth and biological development [62,63]. However, owing to the transcripts’ complexity and diversity, mis-spliced isoforms are frequently inevitable and obliged to be eliminated from the mRNA pool that is ready to be translated into proteins. Otherwise, the translation of aberrantly spliced transcripts may give rise to toxic truncated proteins, which pose a threat to cellular and molecular homeostasis [16,64]. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) plays a key role in identifying and eliminating faulty transcripts containing premature termination codons (PTCs) or unusually long 3′ untranslated regions (3′UTRs). SRSF1, an essential splicing factor, promotes NMD when located downstream of a premature termination codon [65]. UPF2, a key factor of NMD pathway, is essential for clearing mRNAs with PTCs and long 3′UTRs and is necessary for Sertoli cell development and spermatogenesis in male mice [15,66]. Bao et al. proved that ablation of UPF2 in Sertoli cells causes a Leydig-cell-only phenotype by decreasing nine core trans elements, including Wt1 and Dmrt1, contributing to the differentiation of Sertoli cells [15]. Another key factor in the NMD pathway is a pair of homologs—UPF3A and UPF3B—the latter of which co-localizes with the chromatoid body (CB) in round spermatids. Fanourgakis et al. illustrated that the depletion of TDRD6–CB components disrupts the recruitment of UPF1 to mRNAs carrying long 3′UTR and contributes to higher mRNA stability via decreased degradation in post-meiosis haploid [16]. The correlation between key components of NMD and CB suggests that surveillance of alternative splicing may also be affected by CBs, the germ granules in post-meiosis haploids, loaded with RNA and RNA-binding proteins [67,68]. Furthermore, several clinical cases of infertile men, diagnosed as oligo-astheno-teratozoospermia (OAT), have been reported to carry TDRD6 variants, and their symptoms are consistent with phenotypes in male mice [17,69,70]. In these cases, six men carrying TDRD6 variants, together with their wives, were treated with intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), but all failed due to low fertilization rates and poor quality of the embryos. Binbin Wang’s group mentioned that they would try to use artificial oocyte activation (AOA) to improve fertilization rates in the subsequent ICSI cycles, which deserves our attention [70].

N6-methyladenosine (m6A), the most common modification in mRNA, is involved in all stages of RNA metabolism, including the transcription, maturation, transportation, translation, degradation, and stability of mRNA, in mammals [71,72]. Recent studies have illuminated the interplay between m6A modifications and alternative splicing, particularly in the context of tumorigenesis [73]. The m6A modification can mediate alternative-splicing functional patterns by recruiting various RBPs to their target genes or directly affecting the binding dynamics between RNA and RBPs. In turn, alternative splicing can regulate the m6A’s deposition on specific mRNA by m6A methyltransferases (m6A writer) and recognition by the m6A reader. Key m6A regulators have been shown to significantly impact spermatogenesis through their interaction with alternative splicing. METTL3, the earliest identified m6A methyltransferases, can form a stable heterodimer with another m6A methyltransferases-METTL14, facilitating m6A deposition on specific RNAs in the nucleus [74]. Previous studies have demonstrated that genes with m6A deposition show a high level of alternative exon inclusion [75,76]. The depletion of METTL3 caused decreased exon inclusion level of aberrant AS events of several key genes (Dazl, Sohlh1, Cdk11b, and Nasp) in spermatogenesis, which then contributed to a defected initiation of spermatogonia differentiation [18].

Moreover, METTL16, the known methyltransferase for U6 spliceosome small nuclear RNA (snRNA), can install the N6-methylation to A43 of U6 snRNA, located in a fundamental domain of U6 spliceosome, which base pairs 5′ splice sites in pre-mRNA during splicing process [77]. During mice spermatogenesis, METTL16 interacts with SF3B1 and SF3B1 to modulate alternative splicing of meiosis-related genes such as Stag3, Stra8, and Ddb2, while the absence of METTL16 leads to impaired spermatogonia differentiation and compromised meiosis initiation [19]. ALKBH5, the m6A demethylase (m6A eraser), is necessary to generate longer 3′UTR mRNAs with appropriate m6A modifications in male spermatogenesis. In the post-meiosis phase, the longer the 3′UTR transcripts are modified with m6A, the more easily they will be degraded. Indeed, under physiological conditions, the genome-wide shortening transcripts are required for high translation efficiency when transcription activity is shut down during late spermiogenesis [78]. Inactivation of ALKBH5 fails to remove m6A from long 3′UTR mRNAs, contributing to enhanced splicing (up-regulated ESI and down-regulated ISR) and production of massive mis-spliced shorter 3′UTR mRNAs with m6A, which tend to be degraded soon [20]. This process aligns with the previously discussed NMD pathway, where long 3′UTR mRNAs are targeted for degradation [66]. In summary, the regulation of alternative splicing through mechanisms like NMD and m6A modification is essential for maintaining proper cellular function and development, particularly in spermatogenesis.

3. Alternative Splicing in the Self-Renewal and Differentiation of Spermatogonia

In the gonads of male embryonic mice, primordial germ cells transform into T1-prospermatogonia (ProSG) by E12.5, and then T1-ProSG enters a state of arrest at the G0/G1 phase of the mitotic cell cycle by E15. After birth, T1-ProSG migrates from the center of the lumen towards the peripheral basement membrane, regaining its proliferative capacity to develop into T2-ProSG within three days [79,80]. Some T2-ProSGs differentiate into spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs), while others directly become A2 spermatogonia-differentiating spermatogonia, which subsequently undergo meiosis, initiating the first wave of spermatogenesis [81]. Bypassing SSCs in the development process is the most remarkable characteristic of the first wave of spermatogenesis different from constant waves in male mice. SSCs are a specialized cell type within the male germline, possessing the dual potential for progressive differentiation and continuous self-renewal. This population, defined as the undifferentiated spermatogonia—the most primitive cells in the mammalian testicular germ cell lineage—includes Asingle (As), Aparied (Apr), and Aaligned (Aal) spermatogonia, named based on the number of cells in their clones and interconnected by intercellular cytoplasmic bridges [82]. The maintenance of this population, defined as the stem cell pool, is a prerequisite for sustaining ongoing spermatogenesis and male fertility. SSCs partially proliferate into differentiating spermatogonia (A1-4, Intermediate, and B spermatogonia) while retaining a portion of their population [79]. Further, type B spermatogonia differentiate into spermatocytes, which in turn go through meiosis to generate genetically diverse gametes (Figure 2).

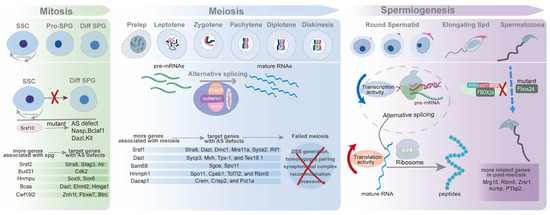

Figure 2.

Alternative splicing in each stage of spermatogenesis. To begin with, germ cells undergo mitosis to give rise to a certain amount of spermatogonia, including undifferentiated and differentiated spermatogonia. Then, differentiated spermatogonia develop into pre-leptotene spermatocytes, entering meiosis, one of most intricate process in biological and molecular activities. After premise and multi-steps of two-round cell divisions, the haploid must go through chromatin condensation, elongation, flagella and acrosome formation, and cytoplasmic elimination. Besides depicting major processes of spermatogenesis, we further delineate one of its representative genes’ schematic diagram in each substage, for example, Srsf10 in mitosis, Hnrnph1 in meiosis, and Fbox24 in spermiogenesis [33,47,81]. Meanwhile, we also list some critical genes and their target genes in its corresponding phase.

SRSF10, a member of the SR protein family, is highly expressed in the brain and testis and participates in many essential cellular and molecular processes via regulating accurate alternative splicing. Liu et al. demonstrated that SRSF10 is vital for maintaining alternative splicing (AS) homeostasis during spermatogenesis [21]. Deletion of SRSF10 impedes the differentiation of progenitor spermatogonia, which are meant to develop into differentiating spermatogonia. This disruption severely affects both transcription and post-transcriptional alternative splicing of RNA in progenitors, ultimately impairing meiosis initiation in male mice. The knockout of SRSF10 caused multiple differentially spliced events (DSEs). Moreover, genes involved in DSEs play crucial roles in RNA metabolism, meiosis, basic biological process, translation regulation, such as Dazl (increased exon inclusion) [83], Sycp1 (increased exon skipping) [84], Kit (A5SS) [85], Exo1 (A5SS) [86], Ret (alternative last exon) [87], and Cdc7 (increased exon inclusion) [88].

Additionally, SRSF1 has been extensively studied in relation to alternative splicing in contexts such as tumorigenesis, heart development, and immune organ development, highlighting its broad significance in various biological processes [22,89,90]. In the testis, SRSF1 plays crucial roles in the homing of precursor spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs) and the survival of spermatogonia by directly binding and regulating the expression levels of TIAR through an alternative splicing pathway [91]. Additionally, SRSF1 interacts with other splicing factors such as SART1, RBM15, and SRSF10, mediating the regulation of genes essential for spermatogonial development. SRSF2, another member of the SR protein family, directly affects the abundance of mRNAs for key genes like Stra8, Stag3, and Atr while increasing the exon skipping ratio of their pre-mRNAs during alternative splicing. SRSF2 knockout mice show arrested spermatogonia differentiation, leading to failed meiosis initiation [23].

BUD31, key component of complex B of mammalian spliceosome, is essential for spliceosome cycle. Deficiency of BUD31 highlights the importance of spliceosomal components in maintaining the SSC reservoir and initiating meiosis in an alternative splicing-dependent manner [24]. Specifically, BUD31 depletion results in the retention of the first intron of Cdk2 pre-mRNA and decreased expression of CDK2 at post-transcriptional level, indicating that precise regulation of this gene is vital for the transition from gonocytes to spermatogonia [25]. Previous study has demonstrated that intron retention leads to the down-regulated gene expression post-transcriptionally [92]. CWF19-like protein 2 (CWF19L2), functioning particularly and necessarily in the final stage of spliceosome cycle to form a complex with intron lariat, is evolutionarily conserved from yeast to mammalians [93,94,95]. Wang et al. illustrated that absence of CWF19L2 resulted in massive apoptosis in differentiating spermatogonia with no meiocytes observed, while undifferentiated spermatogonia remained unaffected. Furthermore, CWF19L2 can regulate alternative splicing by directly binding to genes involved in spermatogenesis (such as Znh1t, Btrc, and Fbxw7) and RNA splicing (including Rbfox1, Celf1, and Rbm10). Notably, approximately 85% of the genes involved in differentially alternative spliced events were not direct targets of CWF19L2, suggesting that CWF19L2 may modulate the alternative splicing of other splicing factors, like RBFOX1, leading to widespread changes in alternative splicing levels [26].

UHRF1, known as ICBP90 in human and NP95 in mice, is a key player in epigenetic mechanism network involved in oocytes maturation, early embryonic development, and spermatogenesis [96,97]. Recent research has revealed a novel role for UHRF1 in RNA metabolism, demonstrating that it can directly bind to U1, U2, and U4 snRNPs and interact with a wide array of ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) to modulate the alternative splicing of genes related to spermatogonial development. The depletion of UHRF1 led to impaired spermatogonia differentiation and SSCs homeostasis, contributing to the development of Sertoli-cell-only syndrome [27]. HnRNPU, the largest member of hnRNP protein family, significantly influences pre-pubertal Sertoli cell proliferation, development, and postnatal maturation, as well as the migration and differentiation of pro-spermatogonia [28,29]. The depletion of hnRNPU in Sertoli cells led to testis atrophy and degradation of seminiferous tubules, resulting in the presence of Sertoli-like cells and germ-cell-like cells. Mechanistically, hnRNPU binds to Sox8 and Sox9’s promoter region, enhancing their expression. For another, hnRNPU interacts with SOX9 and WT1, thereby dominating Sertoli cell’s evolution and male fertility in mice [28]. The same group later confirmed that the absence of hnRNPU in pro-spermatogonia caused an arrest at the transition from T1-ProSG to T2-ProSG, affecting the migration of pro-spermatogonia. Specifically, hnRNPU interacts with RNA-binding proteins and binds to pre-mRNA to mediate its AS events during early spermatogonial development [29]. The loss of PTBP1 in spermatogonia resulted in approximately 20% of the tubules showing disorganization, while NANO3 knockout exhibited impaired pro-spermatogonia differentiation. More importantly, double knockout of PTBP1 and NANO3 resulted in a complete absence of germ cells, including spermatogonia (PLZF+), spermatocytes (SYCP3+), and spermatids. Notably, PTBP1 can bind to the mRNA of Nano3, modulating alternative splicing and the transcriptome in spermatogonia through multiple pathways [30,31].

4. Alternative Splicing in Meiotic Division of Meiocytes

Meiosis is one of the most intricate and ingeniously regulated processes in eukaryotic biological activities, during which genetic material undergoes a single replication followed by two successive cell divisions [98]. The prophase of meiocytes can be divided into five substages based on the molecular behavior and status of chromatin. Initially, chromatin is remodeled and condensed into a linear array of loops emanating from well-coordinated structural chromosome axes. Subsequently, numerous programmed double-strand breaks occur at hotspots within the chromatin loops during leptotene, promoting recombination and homologous synapsis in later prophase [98,99,100]. Following leptotene, zygotene is marked by critical events such as homologous pairing and the formation of chromosome synapsis complexes, driven by complex molecular and genetic forces. With telomeres attached to the inner nuclear envelope and clustered into a bouquet formation, homologous chromosomes are brought into close physical proximity, significantly enhancing their search efficiency and facilitating faster pairing and synapsis [101,102]. Additionally, recombination proteins, such as SPO11, RAD51, and DMC1, play crucial roles in single-strand invasion involved in pairing and synapsis [103,104]. Once homologous chromosomes have achieved a stable structure, known as the synaptonemal complex (SC), the cell formally enters the pachytene stage. During this phase, a characteristic checkpoint eliminates defective spermatocytes that exhibit an incorrect number of double-strand breaks (DSBs), erroneous synapsis, or failed meiotic sex chromosome inactivation (MSCI) (Figure 2) [105,106,107].

Simultaneously, during the single-strand invasion mediated by recombination proteins, single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) pairs with its homologous sequence, forming specialized structures called displacement loops (D-loops). These D-loops primarily resolve into non-crossovers (NCOs), with only a small subset resulting in reciprocal exchanges of flanking chromosome arms, referred to as crossovers (COs). Crossover events, also known as chiasmata, are essential for sexual reproduction, as they induce genetic diversity through chromosomal exchange and ensure the accurate separation of homologous chromosomes by providing a physical connection between maternal and paternal homologs [108,109,110,111]. Following meiotic recombination, the synapsis complex begins to disassemble during the diplotene stage. By metaphase, the entire bivalent—homologous chromosomes linked by chiasmata—aligns along the metaphase plate, ready to be randomly segregated to opposite poles [103,112].

Depletion of SRSF1 in pro-spermatogonia prevents the establishment of a spermatogonial stem cell (SSC) pool. Another study invalidated SRSF1 in undifferentiated and differentiating spermatogonia and revealed its novel role in meiosis, where deletion of SRSF1 resulted in arrest at the pachytene stage. Lei et al. confirmed that SRSF1 directly regulates the alternative splicing of Stra8 and affects Dazl, Dmc1, Mre11a, Syce2, and Rif1 indirectly, all of which are critical for meiosis [36].

Breast-cancer-amplified sequence 2 (BCAS2) is essential for pre-mRNA splicing in spermatogonia and regulates spermatogenesis-related genes, specifically Dazl, Ehmt2, and Hmga1. After the ablation of BCAS2 in pro-spermatogonia, the spermatogonia appear grossly normal, but very few meiocytes can be observed, indicating an arrest in meiosis initiation [37]. The phenotype resulting from BCAS2 knockout in pro-spermatogonia is similar to that observed with Dazl knockout. BCAS2 knockout leads to a distinct shift from full-length Dazl to exon-8-deleted Dazl with exon 7 retention, resulting in the significant decrease in DAZL protein level. DAZL, a member of DAZ (deleted in azoospermia) family, typically targets the 3′UTR of specific transcripts, including Sycp3, Mvh, Tpx-1, and Tex19.1, thereby regulating the initiation of their translation [38,39,40].

SAM68, a ubiquitous protein with stage-specific expression during meiosis and haploid phase, participates in multiple pathways to regulate alternative splicing. The loss of SAM68 leads to reduced spermatocytes of late prophase and continuous apoptotic haploids [32]. Firstly, SAM68 interacts with phosphorylated RNA polymerase II and other splicing factors to form a complex, which is essential for the splicing of Sgce exon 8 [113]. Secondly, SAM68 collaborates with U1snRNP to prevent premature transcript termination by promoting its recruitment to the alternative last exon of target genes [114]. HnRNPH, a hnRNP family member, always suppresses splicing events by competing with other splicing factors, including SAM68. There is an interesting example illustrating how these antagonistic factors coordinate alternative splicing (AS) events in the complex network of transcripts. It is well established that double-strand breaks (DSBs) are catalyzed by SPO11, a topoisomerase-like protein [115]. There are two isoforms of SPO11—SPO11β and SPO11α—determined by the inclusion or skipping of exon 2 [116]. DSBs on autosomes are primarily induced by SPO11β, while those on sex chromosomes depend on SPO11α. The expression of these two isoforms is regulated by the modulation of RNA polymerase II and the recruitment of splicing factors such as SAM68 and hnRNPH [33,35]. In early meiosis, when whole-genome-wide DSBs occur and progressively decrease, the rapid elongation rate of RNA polymerase II promotes the recruitment of SAM68. This, in turn, facilitates the inclusion of exon 2 in pre-mRNA, resulting in the production of SPO11β. In late prophase, as DSBs on autosomes are repaired and only persist on sex chromosomes, the slower elongation speed of RNA polymerase II enhances the recruitment of hnRNPH, competing with SAM68 and advocating exon 2 skipping pre-mRNA and SPO11α splicing. Furthermore, mice that express only SPO11β exhibit deficiencies in sex chromosome pairing, which heightens the risk of aneuploidy—a major contributor to human disorders such as Klinefelter syndrome [117,118]. Disruption of SPO11α leads to defective homologous synapsis in male mice and results in significant spermatocyte death [35].

Later, Feng et al. confirmed that upon deletion of hnRNPH1 (also known as hnRNPH), the exon 2 of SPO11 remained retained in late meiosis, resulting in the related phenotype of sex chromosome asynapsis [33]. Meanwhile, beyond regulating AS of Spo11 in spermatocytes, the group also revealed other critical roles of hnRNPH1 during spermatogenesis. In Sertoli cells, hnRNPH1 interacts with splicing factors PTBP1 to manage the AS of pre-mRNA for target genes functionally associated with cell adhesion. Moreover, it collaborates with the androgen receptor to mediate the transcription levels of various genes linked to cell–cell junctions and the EGFR pathway by binding directly to their promoters in Sertoli cells. In germ cells, hnRNPH1 recruits PTBP2 and SRSF3 to facilitate AS of genes, including Spo11, Cpeb1, Tcf7l2, and Rbm5. Notably, many abnormal AS events triggered by the ablation of hnRNPH1 resemble those observed in PTBP2 knockout models. Consequently, the phenotypes of hnRNPH1-null testes are similar to those in PTBP2-null male mice, characterized by an increased number of apoptotic spermatogenic cells and premature release of these cells into the lumen, along with disrupted F-actin distribution. This indicates impaired cell adhesion and compromised germ–Sertoli-cell interactions, which can be attributed to Sertoli cell polarity [33,46].

RBMXL12, also known as hnRNPGT, is expressed exactly during and immediately after meiosis. In Rbmxl2-null testes, there are almost no post-meiotic cells, indicating a complete meiotic block with only rare instances of completed meiosis, rather than a gradual decline in round spermatids. RBMXL2 controls splicing patterns during meiosis, particularly ensuring the accuracy of splice site selection. Specifically, it inhibits the selection of abnormal splice sites and prevents the inclusion of hidden and premature terminal exons [41].

DAZAP1, also belonging to the hnRNP family, plays a crucial role in regulating the splicing of the transcripts such as Crem, Crisp2, and Pot1a, thereby impacting spermatogenic function. Abnormal splicing can lead to the loss of Pot1a, which affects telomere integrity and partially explains the growth retardation seen in DAZAP1-deficient mice. The absence of DAZAP1 in the testis results in spermatogenesis halting just prior to meiosis, leading to a lack of haploid spermatids [42].

5. Alternative Splicing in Maturation of Haploid Spermatids

After sophisticated meiosis, spermatogenesis comprises spermiogenesis and spermiation, which, respectively, refer to development of post-meiotic male gamete and the release of sperm [119]. During these final stages, haploid cells undergo significant programmed transformations, including chromatin remodeling, elongation of round spermatids, flagella and acrosome formation, and cytoplasmic elimination [119,120]. In the first step of nuclear condensation, the nucleosomal histones in spermatids are gradually replaced by transition nuclear proteins, which are then substituted by protamines, the principal nucleosomal proteins in spermatozoa. This transformation allows for the genetic material to be tightly and orderly compacted, resulting in smaller and more streamlined spermatozoa [121,122].

Before round spermatids differentiate into elongating and elongated spermatids, there are eight distinct sub-phases characterized by changes in acrosome morphology. During the elongation process, organelles undergo reorganization, the sperm tail develops, and mitochondria align along the midpiece of the flagellum to form the sheath. Each of these steps is crucial for the maturation of haploid gametes and male fertility, requiring well-organized gene expression. However, transcription activity ceases around mid-spermiogenesis, with translational control taking precedence in the later stages of spermiogenesis [123,124,125]. As nuclear condensation limits transcription, genes related to spermiogenesis are synthesized in advance and stored as messenger ribonucleoproteins (mRNPs) with suppressed translational activity, ready for activation when needed. Despite significant advancements in our understanding, there remains confusion regarding whether these processes are coordinated at the transcriptome-wide level and how repressed mRNAs are activated for translation [120,122]. Here, combining existing studies, this manuscript offers a tentative glimpse into the landscape of how AS play a role in post-meiosis phase (Figure 2).

MRG15, a MORF-related gene on chromosome 15 that binds to chromatin and regulates pre-mRNA splicing of Tnp2 by recognizing the methylation of H3K36, which promotes the recruitment of splicing factors during spermatogenesis. Specifically, MRG15 facilitates epigenetic modifications that recruit the splicing factors PTBP1 and PTBP2, thereby enhancing alternative splicing. In MRG15-null germ cells, spermatogenesis arrests at the round spermatid stage, despite normal meiosis and histone acetylation [43]. RBM5 serves as a critical splicing regulator in round spermatids, with its RRM2 domain being essential for accurate splicing of target pre-mRNAs during spermiogenesis. RBM5 also interacts with other splicing factors, including SFPQ and hnRNP A2/B1, underscoring its role in the complex splicing network essential for successful spermiogenesis. A missense mutation (R263P) in the RRM2 domain results in a blockage of spermatid differentiation, leading to a significant loss of germ cells and ultimately causing azoospermia [44]. Additionally, the splicing factor U2AF35-like ZRSR1 is involved in recognizing the 3′ splice sites of both U2 and U12 introns. Mutations in ZRSR1 can cause defects in spermatogenesis by altering U12 intron splicing. ZRSR1 may function within both spliceosomes, leading to combined splicing defects, particularly evident in adjacent U2/U12 intron pairs. Deletion of ZRSR1 results in sperm abnormalities, including defects in the neck, midpiece, head, and tail [45].

ACRBP, known as a proacrosin-binding protein, is produced in two forms in mice due to alternative splicing: ACRBP-W and ACRBP-V5. ACRBP-V5 is involved in the formation and configuration of the acrosomal granule during early spermiogenesis, while ACRBP-W maintains the inactive status of proacrosin in the acrosome until acrosomal exocytosis occurs. ACRBP-null spermatids show malformation of acrosome, a defect that can be rescued by the transgenic expression of ACRBP-V5 rather than ACRBP-W [126]. CUG-BP1/CELF1 is a versatile RNA-binding protein that may influence the alternative splicing of unidentified pre-mRNAs in spermatogonia, spermatocytes, or early spermatids, resulting in the production of isoforms necessary for stage 7 of spermiogenesis, which in turn aids in the elongation of round spermatids. Consequently, knockout of CUGBP1 results in arrest at step 7 of round spermatid development and leads to significant apoptosis [127].

PTBP2 is required for the accurate regulation of alternative splicing, contributing to RNA expression modulation during the initial phase of spermatogenesis. Notably, PTBP2-null tubules exhibit round spermatids within the lumen, along with spermatid arrest and the formation of multinucleate cells during initial differentiation [46]. FBXO24 or F-Box Protein 24, associates with splicing factors (SRSF2, SRSF3, and SRSF9) to regulate alternative splicing in round spermatids. Additionally, it interacts with MIWI and SCF subunits to promote MIWI degradation via K48-linked polyubiquitination. FBXO24 in mice results in irregular histone retention, incomplete axoneme structures, enlarged chromatoid bodies, and atypical mitochondrial coiling along the sperm flagella, ultimately leading to male infertility [47]. The human homologous gene TCP11 produces three alternative splicing products known as TCP11a, TCP11b, and TCP11c. TCP11a binds to Outer Dense Fiber 1 (ODF1), a key component of the sperm tail’s outer dense fibers, which are crucial for the unique morphology and functionality of the sperm tail [128].

The absence of TENR leads to defects in sperm head morphology, primarily characterized by blunt acrosomes and tails that are wrapped around the sperm head. These morphological defects contribute to a significant decrease in sperm motility, which in turn affects the sperm’s ability to penetrate the zona pellucida during fertilization [129]. The C-terminus of TENR bears a striking resemblance to the catalytic domain found in adenosine deaminases that act on RNA (ADARs). ADARs carry out RNA editing by transforming adenosine into inosine within double-stranded RNA, further impacting alternative splicing and translation. Considering this structural characteristic, it is speculated that the disruption of TENR may lead to dramatic changes in the AS events involving sperm morphology [129,130]. RANBP9 is highly expressed in the nuclei of spermatocytes and spermatids, where it interacts with key splicing factors like SF3B3 and HNRNPM, as well as poly(A) binding proteins such as PABPC1 and PABPC2 [131,132]. These interactions facilitate the formation of protein complexes that associate with more than 2300 mRNAs, ensuring their proper splicing and expression. The knockout of RANBP9 leads to reduced sperm counts, total motility, and progressive motility, along with various morphological abnormalities in the sperm, including bent, round, or curved heads, and tails that may be coiled or headless. Mechanistically, the mRNA levels of Tnp1, Tnp2, Prm1, and Prm2 decreased significantly owing to the absence of interaction between RANBP9 and those key splicing factors. Moreover, four male germ-cell-specific mRNAs (Ddx25, Catsper1, Catsper4, and Klhl10) were also downregulated [131].

6. Conclusions Remarks

Alternative splicing allows certain genes to generate multiple transcripts, leading to protein isoforms with distinct functions. This process underpins the intricate and well-orchestrated molecular and biological mechanisms in organisms. Spermatogenesis relies on coordinated interactions among various molecules, whose expression is stage-specific and enriched in the testis, reflecting precise temporal and spatial regulation. Our manuscript summarizes the latest studies on genes participating in spermatogenesis via alternative splicing modulation (Table 1). We explore the complex mechanisms by which these splicing factors influence gene expression at both the transcript and translation levels. Additionally, we elucidate the specific mechanisms of alternative splicing, including the spliceosome-catalyzed splicing process, the roles of splicing factors in enhancing or inhibiting splicing at certain regions, and the impact of nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) and post-transcriptional modifications such as m6A, which may affect or be affected by alternative splicing during spermatogenesis. Based on current knowledge regarding germ cell development, we categorize genes related to alternative splicing into three groups: those functioning in spermatogonia, spermatocytes, and spermatids (Figure 2). For each category, we detail the biological and molecular roles of individual genes, their interacting target genes and proteins, and the consequences of their depletion.

If any step in the extensive and complicated network goes wrong, it may lead to non-obstructive azoospermia (NOA)—the most severe male infertility. Currently, there are limited treatments for NOA patients [133]. ICSI is an effective and the most popular strategy for patients who have mature spermatozoa [134]. However, not every NOA patient is amenable to ICSI. For those with testis maturation arrest, stem cell therapy offers a promising future, while a lot of advancement is required in clinically practical applications [135]. The first case of autologous grafting of NOA patient testis tissue has been reported with poor outcome, which also reminds people of this unstable treatment’s high expense financially and timely [136]. Exploring novel and effective therapies is extremely urgent for infertile patients. Moreover, clarifying the AS mechanism in spermatogenesis provides a novel insight into gamete development and potential targets for exploring small molecules and antisense oligonucleotides to correct toxic AS events, caused by common mutations in mammalian genetic defects [137,138,139,140]. In one word, identifying more factors to illuminate the intricate AS landscape holds more promise for the future of infertility patients.

However, there are still some limitations to our review. While we mainly focus on the network of AS in germ cells, it is important to recognize that somatic cells also play a crucial role in the finely tuned mechanisms of spermatogenesis. The interaction between Sertoli cells and germ cells exerts a fundamental influence on cell adhesion [34]. Furthermore, communication among Sertoli cells and between Sertoli and germ cells is essential for forming the blood–testis barrier, which is vital for germ cell development [141]. The Leydig cells produce testosterone, a hormone critical for male fertility; its depletion can lead to one of the most male infertility causes—symptomatic hypogonadism [142,143,144]. In a word, it is necessary to explore AS’s functions in each type of somatic cells and their crosstalk. In summary, our manuscript highlights the latest advancements in understanding alternative splicing in spermatogenesis and provides novel insights into male infertility.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, N.J.; writing—review and editing, Y.L.; visualization, L.Y.; supervision, F.W.; project administration, S.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from Wuhan Natural Science Foundation Exploration Project (Chenguang Project) (To Fengli Wang), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, Huazhong University of Science and Technology (No. 2019kfyXJJS089 to Fengli Wang).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

- Eisenberg, M.L.; Esteves, S.C.; Lamb, D.J.; Hotaling, J.M.; Giwercman, A.; Hwang, K.; Cheng, Y.S. Male infertility. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2023, 9, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotti, F.; Maggi, M. Sexual dysfunction and male infertility. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2018, 15, 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, K.A.; Rambhatla, A.; Schon, S.; Agarwal, A.; Krawetz, S.A.; Dupree, J.M.; Avidor-Reiss, T. Male Infertility is a Women’s Health Issue-Research and Clinical Evaluation of Male Infertility Is Needed. Cells 2020, 9, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Minhas, S.; Dhillo, W.S.; Jayasena, C.N. Male infertility due to testicular disorders. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, e442–e459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krausz, C.; Riera-Escamilla, A. Genetics of male infertility. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2018, 15, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tan, Y.Q.; Yue, Q.; Guo, Y.; Yan, R.; Meng, L.; Zhai, H.; Tong, L.; Yuan, Z.; et al. The landscape of RNA-binding proteins in mammalian spermatogenesis. Science 2024, 386, eadj8172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homma, K.; Kikuno, R.F.; Nagase, T.; Ohara, O.; Nishikawa, K. Alternative splice variants encoding unstable protein domains exist in the human brain. J. Mol. Biol. 2004, 343, 1207–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Lin, C.; Jia, X.; Zhu, H.; Song, J.; Zhang, Y. Noncoding RNAs regulate alternative splicing in Cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 40, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marasco, L.E.; Kornblihtt, A.R. The physiology of alternative splicing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023, 24, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Rio, D.C. Mechanisms and Regulation of Alternative Pre-mRNA Splicing. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2015, 84, 291–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkin, J.; Russell, C.; Chen, P.; Burge, C.B. Evolutionary dynamics of gene and isoform regulation in Mammalian tissues. Science 2012, 338, 1593–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sierra-Rivera, E.; Dasouki, M.; Summar, M.L.; Krishnamani, M.R.; Meredith, M.; Rao, P.N.; Phillips, J.A., 3rd; Freeman, M.L. Assignment of the human gene (GLCLR) that encodes the regulatory subunit of gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase to chromosome 1p21. Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 1996, 72, 252–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, H.; Wang, L.; Chen, D.; Li, F. The Function of Pre-mRNA Alternative Splicing in Mammal Spermatogenesis. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, H.; Yang, X.; Mu, H. Alternative splicing and related RNA binding proteins in human health and disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, J.; Tang, C.; Yuan, S.; Porse, B.T.; Yan, W. UPF2, a nonsense-mediated mRNA decay factor, is required for prepubertal Sertoli cell development and male fertility by ensuring fidelity of the transcriptome. Development 2015, 142, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanourgakis, G.; Lesche, M.; Akpinar, M.; Dahl, A.; Jessberger, R. Chromatoid Body Protein TDRD6 Supports Long 3′ UTR Triggered Nonsense Mediated mRNA Decay. PLoS Genet. 2016, 12, e1005857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Wu, H.; Zhu, X.; Wang, G.; Hu, K.; Li, K.; Geng, H.; Xu, C.; Zu, C.; Gao, Y.; et al. Bi-allelic variants in chromatoid body protein TDRD6 cause spermiogenesis defects and severe oligoasthenoteratozoospermia in humans. J. Med. Genet. 2024, 61, 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Yang, Y.; Feng, G.H.; Sun, B.F.; Chen, J.Q.; Li, Y.F.; Chen, Y.S.; Zhang, X.X.; Wang, C.X.; Jiang, L.Y.; et al. Mettl3-mediated m(6)A regulates spermatogonial differentiation and meiosis initiation. Cell Res. 2017, 27, 1100–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Gui, Y.; Ma, X.; Zhang, B.; Xiong, W.; Yang, S.; Cao, C.; Mo, S.; Shu, G.; Ye, J.; et al. N6-methyladenosine writer METTL16-mediated alternative splicing and translation control are essential for murine spermatogenesis. Genome Biol. 2024, 25, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Klukovich, R.; Peng, H.; Wang, Z.; Yu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, H.; Klungland, A.; Yan, W. ALKBH5-dependent m6A demethylation controls splicing and stability of long 3′-UTR mRNAs in male germ cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E325–E333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Lu, X.; Zhao, Z.H.; Su, R.; Li, Q.L.; Xue, Y.; Gao, Z.; Sun, S.S.; Lei, W.L.; Li, L.; et al. SRSF10 is essential for progenitor spermatogonia expansion by regulating alternative splicing. Elife 2022, 11, e78211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, J.X.; Luo, Y.H.; Zhang, S.J.; Wang, B.; Chen, C.; Zhu, G.Q.; Zhu, P.; Cai, C.Z.; Wan, J.L.; Cai, J.L.; et al. Splicing factor SRSF1 promotes breast cancer progression via oncogenic splice switching of PTPMT1. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 40, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, W.L.; Du, Z.; Meng, T.G.; Su, R.; Li, Y.Y.; Liu, W.; Sun, S.M.; Liu, M.Y.; Hou, Y.; Zhang, C.H.; et al. SRSF2 is required for mRNA splicing during spermatogenesis. BMC Biol. 2023, 21, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, J.; Huang, T.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Dang, Q.; Cui, D.; Wang, X.; Zhai, Y.; Zhao, L.; et al. Bud31-mediated alternative splicing is required for spermatogonial stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Cell Death Differ. 2023, 30, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.; Patel, R.K.; Palmer, N.; Grenier, J.K.; Paduch, D.; Kaldis, P.; Grimson, A.; Schimenti, J.C. CDK2 kinase activity is a regulator of male germ cell fate. Development 2019, 146, dev180273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Cai, Y.; Li, T.; Wang, Y.; Bao, Z.; Wang, R.; Qin, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; et al. CWF19L2 is Essential for Male Fertility and Spermatogenesis by Regulating Alternative Splicing. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2403866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Dong, J.; Xiong, M.; Gan, S.; Wen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Yuan, S.; Gui, Y. UHRF1 interacts with snRNAs and regulates alternative splicing in mouse spermatogonial stem cells. Stem Cell Rep. 2022, 17, 1859–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Ma, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, F.; Dong, J.; Wu, Y.; Lv, C.; Liu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; et al. hnRNPU in Sertoli cells cooperates with WT1 and is essential for testicular development by modulating transcriptional factors Sox8/9. Theranostics 2021, 11, 10030–10046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Zhou, S.; Gui, Y.; Li, Z.; Yin, L.; Xu, W.; Feng, S.; Ma, X.; Gan, S.; Xiong, M.; et al. hnRNPU is required for spermatogonial stem cell pool establishment in mice. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 114113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senoo, M.; Hozoji, H.; Ishikawa-Yamauchi, Y.; Takijiri, T.; Ohta, S.; Ukai, T.; Kabata, M.; Yamamoto, T.; Yamada, Y.; Ikawa, M.; et al. RNA-binding protein Ptbp1 regulates alternative splicing and transcriptome in spermatogonia and maintains spermatogenesis in concert with Nanos3. J. Reprod. Dev. 2020, 66, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Tsuda, M.; Kiso, M.; Saga, Y. Nanos3 maintains the germ cell lineage in the mouse by suppressing both Bax-dependent and -independent apoptotic pathways. Dev. Biol. 2008, 318, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paronetto, M.P.; Messina, V.; Bianchi, E.; Barchi, M.; Vogel, G.; Moretti, C.; Palombi, F.; Stefanini, M.; Geremia, R.; Richard, S.; et al. Sam68 regulates translation of target mRNAs in male germ cells, necessary for mouse spermatogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 2009, 185, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, S.; Li, J.; Wen, H.; Liu, K.; Gui, Y.; Wen, Y.; Wang, X.; Yuan, S. hnRNPH1 recruits PTBP2 and SRSF3 to modulate alternative splicing in germ cells. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, S.; Wen, H.; Liu, K.; Xiong, M.; Li, J.; Gui, Y.; Lv, C.; Zhang, J.; Ma, X.; Wang, X.; et al. hnRNPH1 establishes Sertoli-germ cell crosstalk through cooperation with PTBP1 and AR, and is essential for male fertility in mice. Development 2023, 150, dev201040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesari, E.; Loiarro, M.; Naro, C.; Pieraccioli, M.; Farini, D.; Pellegrini, L.; Pagliarini, V.; Bielli, P.; Sette, C. Combinatorial control of Spo11 alternative splicing by modulation of RNA polymerase II dynamics and splicing factor recruitment during meiosis. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, W.L.; Li, Y.Y.; Du, Z.; Su, R.; Meng, T.G.; Ning, Y.; Hou, G.; Schatten, H.; Wang, Z.B.; Han, Z.; et al. SRSF1-mediated alternative splicing is required for spermatogenesis. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2023, 19, 4883–4897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, F.; Xu, Q.; Shi, J.; Zhang, X.; Lu, X.; Zhao, Z.A.; Gao, Z.; Ma, H.; Duan, E.; et al. BCAS2 is involved in alternative mRNA splicing in spermatogonia and the transition to meiosis. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, N.; Collier, B.; Bingham, V.; Gray, N.K.; Cooke, H.J. Translation of the synaptonemal complex component Sycp3 is enhanced in vivo by the germ cell specific regulator Dazl. RNA 2007, 13, 974–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, N.; Collier, B.; Maratou, K.; Bingham, V.; Speed, R.M.; Taggart, M.; Semple, C.A.; Gray, N.K.; Cooke, H.J. Dazl binds in vivo to specific transcripts and can regulate the pre-meiotic translation of Mvh in germ cells. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005, 14, 3899–3909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.; Lu, Y.; Liao, X.; Li, D.; Sun, H.; Liang, S.; Zhang, S.; Ma, Y.; Yang, Z. DAZL binds to 3′UTR of Tex19.1 mRNAs and regulates Tex19.1 expression. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2009, 36, 2399–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrmann, I.; Crichton, J.H.; Gazzara, M.R.; James, K.; Liu, Y.; Grellscheid, S.N.; Curk, T.; de Rooij, D.; Steyn, J.S.; Cockell, S.; et al. An ancient germ cell-specific RNA-binding protein protects the germline from cryptic splice site poisoning. Elife 2019, 8, e39304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.Y.; Yu, Y.H.; Yen, P.H. DAZAP1 regulates the splicing of Crem, Crisp2 and Pot1a transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, 9858–9869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwamori, N.; Tominaga, K.; Sato, T.; Riehle, K.; Iwamori, T.; Ohkawa, Y.; Coarfa, C.; Ono, E.; Matzuk, M.M. MRG15 is required for pre-mRNA splicing and spermatogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E5408–E5415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Bryan, M.K.; Clark, B.J.; McLaughlin, E.A.; D’Sylva, R.J.; O’Donnell, L.; Wilce, J.A.; Sutherland, J.; O’Connor, A.E.; Whittle, B.; Goodnow, C.C.; et al. RBM5 is a male germ cell splicing factor and is required for spermatid differentiation and male fertility. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horiuchi, K.; Perez-Cerezales, S.; Papasaikas, P.; Ramos-Ibeas, P.; Lopez-Cardona, A.P.; Laguna-Barraza, R.; Fonseca Balvis, N.; Pericuesta, E.; Fernandez-Gonzalez, R.; Planells, B.; et al. Impaired Spermatogenesis, Muscle, and Erythrocyte Function in U12 Intron Splicing-Defective Zrsr1 Mutant Mice. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagore, L.L.; Grabinski, S.E.; Sweet, T.J.; Hannigan, M.M.; Sramkoski, R.M.; Li, Q.; Licatalosi, D.D. RNA Binding Protein Ptbp2 Is Essential for Male Germ Cell Development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2015, 35, 4030–4042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, L.; Yuan, S. FBXO24 modulates mRNA alternative splicing and MIWI degradation and is required for normal sperm formation and male fertility. Elife 2024, 12, RP91666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, P.A. RNA splicing and genes. JAMA 1988, 260, 3035–3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogalska, M.E.; Vivori, C.; Valcarcel, J. Regulation of pre-mRNA splicing: Roles in physiology and disease, and therapeutic prospects. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2023, 24, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, R. Mechanisms of fidelity in pre-mRNA splicing. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2000, 12, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baralle, F.E.; Giudice, J. Alternative splicing as a regulator of development and tissue identity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, H.; Hu, X.; Li, J.; Fu, B.; Wei, M.; Huang, H.; Wu, H. The interplay between non-coding RNAs and alternative splicing: From regulatory mechanism to therapeutic implications in cancer. Theranostics 2023, 13, 2616–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Fang, L.; Wu, C. Alternative Splicing and Isoforms: From Mechanisms to Diseases. Genes 2022, 13, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ule, J.; Blencowe, B.J. Alternative Splicing Regulatory Networks: Functions, Mechanisms, and Evolution. Mol. Cell 2019, 76, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matlin, A.J.; Clark, F.; Smith, C.W. Understanding alternative splicing: Towards a cellular code. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005, 6, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, P.A.; Goebl, A.M.; Smith, C.C.R.; Rosenberger, K.; Kane, N.C. Gene expression and alternative splicing contribute to adaptive divergence of ecotypes. Heredity 2024, 132, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, D.L. Mechanisms of alternative pre-messenger RNA splicing. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2003, 72, 291–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graveley, B.R. Sorting out the complexity of SR protein functions. RNA 2000, 6, 1197–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xiao, X.; Van Nostrand, E.; Burge, C.B. General and specific functions of exonic splicing silencers in splicing control. Mol. Cell 2006, 23, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadra, M.; Howell, P.; Dutta, S.; Heintz, C.; Mair, W.B. Alternative splicing in aging and longevity. Hum. Genet. 2020, 139, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, S.; Merkuri, F.; Chain, F.J.J.; Fish, J.L. Splicing is dynamically regulated during limb development. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weischenfeldt, J.; Waage, J.; Tian, G.; Zhao, J.; Damgaard, I.; Jakobsen, J.S.; Kristiansen, K.; Krogh, A.; Wang, J.; Porse, B.T. Mammalian tissues defective in nonsense-mediated mRNA decay display highly aberrant splicing patterns. Genome Biol. 2012, 13, R35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, B.P.; Green, R.E.; Brenner, S.E. Evidence for the widespread coupling of alternative splicing and nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shum, E.Y.; Jones, S.H.; Shao, A.; Chousal, J.N.; Krause, M.D.; Chan, W.K.; Lou, C.H.; Espinoza, J.L.; Song, H.W.; Phan, M.H.; et al. The Antagonistic Gene Paralogs Upf3a and Upf3b Govern Nonsense-Mediated RNA Decay. Cell 2016, 165, 382–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aznarez, I.; Nomakuchi, T.T.; Tetenbaum-Novatt, J.; Rahman, M.A.; Fregoso, O.; Rees, H.; Krainer, A.R. Mechanism of Nonsense-Mediated mRNA Decay Stimulation by Splicing Factor SRSF1. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 2186–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.; Vitting-Seerup, K.; Waage, J.; Tang, C.; Ge, Y.; Porse, B.T.; Yan, W. UPF2-Dependent Nonsense-Mediated mRNA Decay Pathway Is Essential for Spermatogenesis by Selectively Eliminating Longer 3′UTR Transcripts. PLoS Genet. 2016, 12, e1005863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meikar, O.; Da Ros, M.; Korhonen, H.; Kotaja, N. Chromatoid body and small RNAs in male germ cells. Reproduction 2011, 142, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peruquetti, R.L. Perspectives on mammalian chromatoid body research. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2015, 159, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, Y.W.; Wang, X.; Su, Z.Y.; Wang, C.; Ji, Z.Y.; Mei, L.B.; Zhang, L.; Deng, B.B.; Huang, X.J.; Yan, W.; et al. TDRD6 is associated with oligoasthenoteratozoospermia by sequencing the patient from a consanguineous family. Gene 2018, 659, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, X.; Jin, H.; Wan, F.; Xia, Y.; Guo, H.; Chen, S.; Wang, B. Loss-of-function variant in TDRD6 cause male infertility with severe oligo-astheno-teratozoospermia in human and mice. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2024, 28, e18580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Duan, H. The role of m6A RNA methylation in cancer metabolism. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oerum, S.; Meynier, V.; Catala, M.; Tisne, C. A comprehensive review of m6A/m6Am RNA methyltransferase structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 7239–7255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.M.; Huo, F.C.; Zhang, J.; Shan, H.J.; Pei, D.S. Crosstalk between m6A modification and alternative splicing during cancer progression. Clin. Transl. Med. 2023, 13, e1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Yue, Y.; Han, D.; Wang, X.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Jia, G.; Yu, M.; Lu, Z.; Deng, X.; et al. A METTL3-METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6-adenosine methylation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014, 10, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, W.; Adhikari, S.; Dahal, U.; Chen, Y.S.; Hao, Y.J.; Sun, B.F.; Sun, H.Y.; Li, A.; Ping, X.L.; Lai, W.Y.; et al. Nuclear m(6)A Reader YTHDC1 Regulates mRNA Splicing. Mol. Cell 2016, 61, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yang, Y.; Sun, B.F.; Shi, Y.; Yang, X.; Xiao, W.; Hao, Y.J.; Ping, X.L.; Chen, Y.S.; Wang, W.J.; et al. FTO-dependent demethylation of N6-methyladenosine regulates mRNA splicing and is required for adipogenesis. Cell Res. 2014, 24, 1403–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warda, A.S.; Kretschmer, J.; Hackert, P.; Lenz, C.; Urlaub, H.; Hobartner, C.; Sloan, K.E.; Bohnsack, M.T. Human METTL16 is a N(6)-methyladenosine (m(6)A) methyltransferase that targets pre-mRNAs and various non-coding RNAs. EMBO Rep. 2017, 18, 2004–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tang, C.; Yu, T.; Zhang, R.; Zheng, H.; Yan, W. MicroRNAs control mRNA fate by compartmentalization based on 3′ UTR length in male germ cells. Genome Biol. 2017, 18, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makela, J.A.; Hobbs, R.M. Molecular regulation of spermatogonial stem cell renewal and differentiation. Reproduction 2019, 158, R169–R187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Rooij, D.G. The nature and dynamics of spermatogonial stem cells. Development 2017, 144, 3022–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbani, M.; Zheng, X.; Manske, G.L.; Vargo, A.; Shami, A.N.; Li, J.Z.; Hammoud, S.S. Decoding the Spermatogenesis Program: New Insights from Transcriptomic Analyses. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2022, 56, 339–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Rooij, D.G. Proliferation and differentiation of spermatogonial stem cells. Reproduction 2001, 121, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Liang, Z.; Yang, J.; Wang, D.; Wang, H.; Zhu, M.; Geng, B.; Xu, E.Y. DAZL is a master translational regulator of murine spermatogenesis. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2019, 6, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billmyre, K.K.; Kesler, E.A.; Tsuchiya, D.; Corbin, T.J.; Weaver, K.; Moran, A.; Yu, Z.; Adams, L.; Delventhal, K.; Durnin, M.; et al. SYCP1 head-to-head assembly is required for chromosome synapsis in mouse meiosis. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadi1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerif, F.; Cadoret, V.; Rahal-Perola, V.; Lansac, J.; Bernex, F.; Panthier, J.J.; Hochereau-de Reviers, M.T.; Royere, D. Apoptosis, onset and maintenance of spermatogenesis: Evidence for the involvement of Kit in Kit-haplodeficient mice. Biol. Reprod. 2002, 67, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, M.; Payero, L.; Salim, S.; Fajish, V.G.; Farnaz, A.F.; Pannafino, G.; Chen, J.J.; Ajith, V.P.; Momoh, S.; Scotland, M.; et al. Exo1 protects DNA nicks from ligation to promote crossover formation during meiosis. PLoS Biol. 2023, 21, e3002085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Naughton, C.K.; Yang, M.; Strickland, A.; Vij, K.; Encinas, M.; Golden, J.; Gupta, A.; Heuckeroth, R.; Johnson, E.M., Jr.; et al. Mice expressing a dominant-negative Ret mutation phenocopy human Hirschsprung disease and delineate a direct role of Ret in spermatogenesis. Development 2004, 131, 5503–5513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Challa, K.; Fajish, V.G.; Shinohara, M.; Klein, F.; Gasser, S.M.; Shinohara, A. Meiosis-specific prophase-like pathway controls cleavage-independent release of cohesin by Wapl phosphorylation. PLoS Genet. 2019, 15, e1007851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Wang, F.; Yu, G.; Wang, D.; Yao, Y.; You, M.; Liu, J.; Liu, J.; Sun, Z.; Ji, C.; et al. SRSF1 serves as a critical posttranscriptional regulator at the late stage of thymocyte development. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabf0753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yang, D.; Ding, J.H.; Wang, W.; Chu, P.H.; Dalton, N.D.; Wang, H.Y.; Bermingham, J.R., Jr.; Ye, Z.; Liu, F.; et al. ASF/SF2-regulated CaMKIIdelta alternative splicing temporally reprograms excitation-contraction coupling in cardiac muscle. Cell 2005, 120, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Lv, Z.; Chen, X.; Ye, R.; Tian, S.; Wang, C.; Xie, X.; Yan, L.; Yao, X.; Shao, Y.; et al. Splicing factor SRSF1 is essential for homing of precursor spermatogonial stem cells in mice. Elife 2024, 12, RP89316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz, U.; Pinello, N.; Jia, F.; Alasmari, S.; Ritchie, W.; Keightley, M.C.; Shini, S.; Lieschke, G.J.; Wong, J.J.; Rasko, J.E.J. Intron retention enhances gene regulatory complexity in vertebrates. Genome Biol. 2017, 18, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrey, S.M.; Katolik, A.; Prekeris, M.; Li, X.; York, K.; Bernards, S.; Fields, S.; Zhao, R.; Damha, M.J.; Hesselberth, J.R. A homolog of lariat-debranching enzyme modulates turnover of branched RNA. RNA 2014, 20, 1337–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohi, M.D.; Link, A.J.; Ren, L.; Jennings, J.L.; McDonald, W.H.; Gould, K.L. Proteomics analysis reveals stable multiprotein complexes in both fission and budding yeasts containing Myb-related Cdc5p/Cef1p, novel pre-mRNA splicing factors, and snRNAs. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002, 22, 2011–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhan, X.; Yan, C.; Zhang, W.; Liu, D.; Lei, J.; Shi, Y. Structures of the human spliceosomes before and after release of the ligated exon. Cell Res. 2019, 29, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Li, M.; Liu, F.; Ni, X.; Wang, S.; Zhang, H.; Sui, X.; Huo, R. Deletion of maternal UHRF1 severely reduces mouse oocyte quality and causes developmental defects in preimplantation embryos. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 8294–8305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Wang, X.; Cao, C.; Wen, Y.; Sakashita, A.; Chen, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Luo, M.; et al. UHRF1 suppresses retrotransposons and cooperates with PRMT5 and PIWI proteins in male germ cells. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villeneuve, A.M.; Hillers, K.J. Whence meiosis? Cell 2001, 106, 647–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.; Shinohara, A. Chromosome architecture and homologous recombination in meiosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 1097446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zickler, D.; Kleckner, N. Meiotic chromosomes: Integrating structure and function. Annu. Rev. Genet. 1999, 33, 603–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, L.; Golubovskaya, I.; Cande, W.Z. A bouquet of chromosomes. J. Cell Sci. 2004, 117 Pt 18, 4025–4032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mytlis, A.; Kumar, V.; Qiu, T.; Deis, R.; Hart, N.; Levy, K.; Masek, M.; Shawahny, A.; Ahmad, A.; Eitan, H.; et al. Control of meiotic chromosomal bouquet and germ cell morphogenesis by the zygotene cilium. Science 2022, 376, eabh3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlowski, W.P.; Cande, W.Z. Coordinating the events of the meiotic prophase. Trends Cell Biol. 2005, 15, 674–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, P.; Krejci, L.; Van Komen, S.; Sehorn, M.G. Rad51 recombinase and recombination mediators. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 42729–42732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochwagen, A. Meiosis. Curr. Biol. 2008, 18, R641–R645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royo, H.; Polikiewicz, G.; Mahadevaiah, S.K.; Prosser, H.; Mitchell, M.; Bradley, A.; de Rooij, D.G.; Burgoyne, P.S.; Turner, J.M. Evidence that meiotic sex chromosome inactivation is essential for male fertility. Curr. Biol. 2010, 20, 2117–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murat, F.; Mbengue, N.; Winge, S.B.; Trefzer, T.; Leushkin, E.; Sepp, M.; Cardoso-Moreira, M.; Schmidt, J.; Schneider, C.; Mossinger, K.; et al. The molecular evolution of spermatogenesis across mammals. Nature 2023, 613, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grey, C.; de Massy, B. Coupling crossover and synaptonemal complex in meiosis. Genes Dev. 2022, 36, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollingsworth, N.M. A new role for the synaptonemal complex in the regulation of meiotic recombination. Genes Dev. 2020, 34, 1562–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Shang, Y.; Zhai, B.; Yang, X.; Kleckner, N.; Zhang, L. Crossover Interference, Crossover Maturation, and Human Aneuploidy. Bioessays 2019, 41, e1800221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Shang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhai, B.; Yang, X.; Zhang, L. Crossover patterns under meiotic chromosome program. Asian J. Androl. 2021, 23, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petronczki, M.; Siomos, M.F.; Nasmyth, K. Un menage a quatre: The molecular biology of chromosome segregation in meiosis. Cell 2003, 112, 423–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paronetto, M.P.; Messina, V.; Barchi, M.; Geremia, R.; Richard, S.; Sette, C. Sam68 marks the transcriptionally active stages of spermatogenesis and modulates alternative splicing in male germ cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 4961–4974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naro, C.; Pellegrini, L.; Jolly, A.; Farini, D.; Cesari, E.; Bielli, P.; de la Grange, P.; Sette, C. Functional Interaction between U1snRNP and Sam68 Insures Proper 3′ End Pre-mRNA Processing during Germ Cell Differentiation. Cell Rep. 2019, 26, 2929–2941.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, D.; Crawford, M.; Cooper, T.; Claeys Bouuaert, C.; Keeney, S.; Llorente, B.; Garcia, V.; Neale, M.J. Concerted cutting by Spo11 illuminates meiotic DNA break mechanics. Nature 2021, 594, 572–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeney, S.; Baudat, F.; Angeles, M.; Zhou, Z.H.; Copeland, N.G.; Jenkins, N.A.; Manova, K.; Jasin, M. A mouse homolog of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae meiotic recombination DNA transesterase Spo11p. Genomics 1999, 61, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, N.S.; Hassold, T.J. Aberrant recombination and the origin of Klinefelter syndrome. Hum. Reprod. Update 2003, 9, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauppi, L.; Barchi, M.; Baudat, F.; Romanienko, P.J.; Keeney, S.; Jasin, M. Distinct properties of the XY pseudoautosomal region crucial for male meiosis. Science 2011, 331, 916–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Mruk, D.D.; Cheng, Y.H.; Tang, E.I.; Han, D.; Lee, W.M.; Wong, E.W.; Cheng, C.Y. Actin binding proteins, spermatid transport and spermiation. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2014, 30, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.Y.; Wen, Z.; Pan, D.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhong, A.; Yu, X.; Wu, Y.C.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; et al. LLPS of FXR1 drives spermiogenesis by activating translation of stored mRNAs. Science 2022, 377, eabj6647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, K.; Park, S.; Oura, S.; Noda, T.; Morohoshi, A.; Matzuk, M.M.; Ikawa, M. TSKS localizes to nuage in spermatids and regulates cytoplasmic elimination during spermiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2221762120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, H.; Wang, W.; Zhou, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yang, P.; Guo, R.; Chen, W.; Zhang, J.; Ye, L.; et al. Single-cell RNA-seq uncovers dynamic processes orchestrated by RNA-binding protein DDX43 in chromatin remodeling during spermiogenesis. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleene, K.C. Multiple controls over the efficiency of translation of the mRNAs encoding transition proteins, protamines, and the mitochondrial capsule selenoprotein in late spermatids in mice. Dev. Biol. 1993, 159, 720–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steger, K. Transcriptional and translational regulation of gene expression in haploid spermatids. Anat. Embryol. 1999, 199, 471–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanagiya, A.; Delbes, G.; Svitkin, Y.V.; Robaire, B.; Sonenberg, N. The poly(A)-binding protein partner Paip2a controls translation during late spermiogenesis in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2010, 120, 3389–3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanemori, Y.; Koga, Y.; Sudo, M.; Kang, W.; Kashiwabara, S.; Ikawa, M.; Hasuwa, H.; Nagashima, K.; Ishikawa, Y.; Ogonuki, N.; et al. Biogenesis of sperm acrosome is regulated by pre-mRNA alternative splicing of Acrbp in the mouse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E3696–E3705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kress, C.; Gautier-Courteille, C.; Osborne, H.B.; Babinet, C.; Paillard, L. Inactivation of CUG-BP1/CELF1 causes growth, viability, and spermatogenesis defects in mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007, 27, 1146–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Jiang, M.; Li, C.; Yang, P.; Sun, H.; Tao, D.; Zhang, S.; Ma, Y. Human t-complex protein 11 (TCP11), a testis-specific gene product, is a potential determinant of the sperm morphology. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2011, 224, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Connolly, C.M.; Dearth, A.T.; Braun, R.E. Disruption of murine Tenr results in teratospermia and male infertility. Dev. Biol. 2005, 278, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, J.M.; Lee, K.; Edelhoff, S.; Braun, R.E. Distribution of Tenr, an RNA-binding protein, in a lattice-like network within the spermatid nucleus in the mouse. Biol. Reprod. 1995, 52, 1274–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.; Tang, C.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Bhetwal, B.P.; Zheng, H.; Yan, W. RAN-binding protein 9 is involved in alternative splicing and is critical for male germ cell development and male fertility. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10, e1004825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Lu, Y.; Tao, D.; Liu, Y.; Ma, Y. CLOCK interacts with RANBP9 and is involved in alternative splicing in spermatogenesis. Gene 2018, 642, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vij, S.C.; Sabanegh, E., Jr.; Agarwal, A. Biological therapy for non-obstructive azoospermia. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2018, 18, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wambergue, C.; Zouari, R.; Fourati Ben Mustapha, S.; Martinez, G.; Devillard, F.; Hennebicq, S.; Satre, V.; Brouillet, S.; Halouani, L.; Marrakchi, O.; et al. Patients with multiple morphological abnormalities of the sperm flagella due to DNAH1 mutations have a good prognosis following intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Hum. Reprod. 2016, 31, 1164–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermann, B.P.; Sukhwani, M.; Winkler, F.; Pascarella, J.N.; Peters, K.A.; Sheng, Y.; Valli, H.; Rodriguez, M.; Ezzelarab, M.; Dargo, G.; et al. Spermatogonial stem cell transplantation into rhesus testes regenerates spermatogenesis producing functional sperm. Cell Stem Cell 2012, 11, 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, C.F.S.; Mamsen, L.S.; Wang, D.; Fode, M.; Giwercman, A.; Jorgensen, N.; Ohl, D.A.; Fedder, J.; Hoffmann, E.R.; Yding Andersen, C.; et al. Results from the first autologous grafting of adult human testis tissue: A case report. Hum. Reprod. 2024, 39, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnal, S.; Vigevani, L.; Valcarcel, J. The spliceosome as a target of novel antitumour drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2012, 11, 847–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartegni, L.; Krainer, A.R. Correction of disease-associated exon skipping by synthetic exon-specific activators. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2003, 10, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y.; Vickers, T.A.; Okunola, H.L.; Bennett, C.F.; Krainer, A.R. Antisense masking of an hnRNP A1/A2 intronic splicing silencer corrects SMN2 splicing in transgenic mice. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008, 82, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, T.R.; Joyner, A.S.; Potter, P.M. The development and application of small molecule modulators of SF3b as therapeutic agents for cancer. Drug Discov. Today 2013, 18, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.Y.; Wong, E.W.; Yan, H.H.; Mruk, D.D. Regulation of spermatogenesis in the microenvironment of the seminiferous epithelium: New insights and advances. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2010, 315, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zirkin, B.R.; Papadopoulos, V. Leydig cells: Formation, function, and regulation. Biol. Reprod. 2018, 99, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pencina, K.M.; Travison, T.G.; Cunningham, G.R.; Lincoff, A.M.; Nissen, S.E.; Khera, M.; Miller, M.G.; Flevaris, P.; Li, X.; Wannemuehler, K.; et al. Effect of Testosterone Replacement Therapy on Sexual Function and Hypogonadal Symptoms in Men with Hypogonadism. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 109, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Midzak, A.S.; Chen, H.; Papadopoulos, V.; Zirkin, B.R. Leydig cell aging and the mechanisms of reduced testosterone synthesis. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2009, 299, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).