Abstract

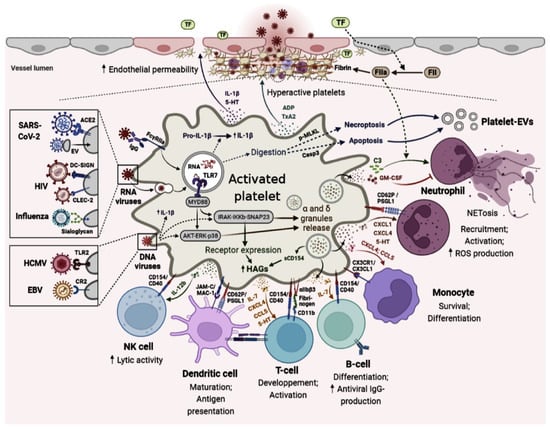

Platelets play a major role in the processes of primary hemostasis and pathological inflammation-induced thrombosis. In the mid-2000s, several studies expanded the role of these particular cells, placing them in the “immune continuum” and thus changing the understanding of their function in both innate and adaptive immune responses. Among the many receptors they express on their surface, platelets express Toll-Like Receptors (TLRs), key receptors in the inflammatory cell–cell reaction and in the interaction between innate and adaptive immunity. In response to an infectious stimulus, platelets will become differentially activated. Platelet activation is variable depending on whether platelets are activated by a hemostatic or pathogen stimulus. This review highlights the role that platelets play in platelet modulation count and adaptative immune response during viral infection.

1. Introduction

Platelets originating from megakaryocytes are anucleate cells that play a key role in vascular repair and maintenance of hemostasis, particularly in primary hemostasis [1]. Located in blood vessels, platelets have a discoid shape, a size of 3 mm by 0.5 mm, a lifespan of 10 days, and a count of 250 million of adult blood molecules per mL [2,3]. Platelets have traditionally been associated with rapid procoagulant responses mediated by G-protein-coupled receptors that promote platelet function including adhesion, activation, aggregation, eicosanoid synthesis, and granule secretion [4]. Platelet membrane integrins can interact with molecules of the injured endothelium, inducing their adhesion, activation, and aggregation in turn. Consequently, the formation of a thrombus takes place, and this clot consists of platelets aggregate bonded together by fibrinogen and ensuring closing the vascular breach [5]. In addition to their role in hemostasis, studies have shown that platelets can aggregate at the bacterial invasion site, accumulate in inflammatory areas, and target susceptible tissues to antigen-mediated inflammatory responses [6]. In fact, this platelet aggregation is a defense mechanism to aid pathogens clearance by the immune system [7]. When platelets cannot, extracellular vesicles derived from platelets can enter lymph, bone marrow, and synovial fluid. Consequently, platelet-derived extracellular vesicles (PEVs) are able to transfer a variety of contents to cells and organs inaccessible to platelets [8].

Because of their rapid presence at the injury site, and due to their speculated role in infectious diseases, platelets became well known as the first immune cells to be in contact with the pathogen during systemic infection. Indeed, infections are often associated with thrombocytopenia, which predicted increased severity, suggesting that these cells might have a great importance in coping with pathogens [9]. To do so, platelets must be able to activate other cells of the innate and adaptive immunity through (1) detecting the pathogen, (2) targeting it (and eliminate when possible), and (3) warning other cells about the presence of a pathogen as well as its type [10]. The interaction between platelets and infectious pathogens involves different receptors and intra-platelet signaling, leading to distinct responses depending on the pathogen [9].

All cellular components responsible for hemostasis and immunity are transferred to platelets by megakaryocytes, including chemokines, immune receptors, RNA molecules, and spliceosomes [11,12]. It has been found that megakaryocytes are susceptible to a variety of viruses [13]. Further, megakaryocytes express pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and cytokine receptors, which affects megakaryocytic maturation and thrombopoietic activity [13,14]. In vitro, megakaryocytes respond to viral infections as well as viral pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) by producing large amounts of IFNs, which in turn reduce platelet production through an autocrine interferon-α/β receptor (IFNAR) pathway [13,15]. The involvement of megakaryocytes in immune response still requires more investigation, even if megakaryocyte infection might alter the phenotype of platelet progeny during infections.

Through the expression of a wide variety of PRRs and hemostatic receptors, platelets are able to capture fragments of pathogens, whether they are bacteria, viruses, parasites, or fungi [9]. Precisely, platelets and their progenitor cells, the megakaryocytes (MK), possess direct antiviral immune activities and have shown the ability to internalize viruses. In fact, these unique cells ensure their immune role since they express a large number of receptors dedicated to viruses’ interaction [6]. In addition, and as a response to this interaction, these cells have the ability to secrete several inflammatory and/or immunomodulating molecules that can interact with other immune cells (or non-immune cells such as endothelial cells) and modulate the cellular responses of both innate and adaptive immunity [16]. Platelets can produce molecules involved in the adaptive response such as FasL, TRAIL, IL-7, and CD40L. The role of FasL and TRAIL in platelets has been poorly studied; however, FasL and TRAIL are known to be potential inducers of apoptosis of carcinogenic or infected cells [17]. These molecules production by activated platelets could therefore be critical for the antitumor and anti-infectious response [18]. The major actor in the interactions between platelets and other immune cells is the CD40L/CD40 pair, which has long been known to induce multiple inflammatory and immune responses [19]. As a result of the CD40L/CD40 interaction, mitogen and stress-activated protein kinase (MAPK/SAPK) cascades are activated, transcription factors are also activated, cytokines are secreted, B cells proliferate and differentiate into Ig-secreting plasma cells, and humoral memory is established [20].

As for IL-7, activated platelets was shown to be one of the major sources of this cytokine [21]. Consequently, considering IL-7 signaling during viral infection, remarkably increased numbers of T cells’ effector were noted, suggesting its role in immune cell expansion [22]. After platelets recognize the pathogen, they become activated, and the activated platelets, via various mechanisms, kill or sequester the pathogen by activating neutrophils and macrophages. As part of the innate immune response, platelet neutrophil interaction leads to neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), which can enhance platelet adhesion, activation, secretion, and aggregation inducing microthrombi formation [23].

In this narrative review, our aim was to highlight the role of platelets in viral infection through depicting their interaction with multiple viruses, its consequence, and its way of affecting the viral-associated physiopathology.

2. Viral Receptors on the Platelets Surface

Platelets have emerged as one of the crucial players in mediating the response to infectious disease and especially to viruses. While platelets do not have nuclei, they possess all the molecular machinery to synthesize proteins from stored mRNA, suggesting they can translate proteins from RNA viruses as well [24,25]. On the surface of these tiny bits of cytoplasm, a variety of expressed receptors allow for their interaction with the virus [6]. Indeed, this interaction involves virus-specific receptors and surface glycoproteins whose original hemostatic function is hijacked by viruses, allowing for their recognition [6].

In both experimental viral infections and naturally infected human patients, platelet participation in immune response to virus has been investigated. Many of the PRRs associated with viral recognition have been found to be present and functional in platelets [26,27]. Platelets express various PRRs such as TLRs, complement, and Fc- γ receptors. As for TLRs, these functional PRRs are able to sense microbes, subsequently triggering platelet effector responses responsible for modulating the innate immune response [28]. Platelets and megakaryocytes express TLRs (TLR 1, TLR 2, TLR 3, TLR 4, TLR 6, TLR 7, TLR 8, and TLR 9) that detect and bind viral components on their surface and viral nucleic acids [29]. Once activated, TLRs recruit adaptor molecules are required for signal propagation to lead to the induction of genes that orchestrate inflammation [29]. TLR 4 on platelets acts as an inflammatory sentinel and surrounds and isolates an infection, as well as modulating proinflammatory cytokine release [30]. The induced response against single-stranded RNA viruses by platelets was noted to be a predominantly TLR 7-mediated process [26,31]. TLR 7 is located in platelets’ endolysosomes and requires internalization of virus particles and the acidic pH of endolysosomes for its own activation and signaling [26]. This TLR was also involved in enhancing platelets’ uptake of viruses, such as influenza, leading to neutrophil NETosis [32]. Furthermore, Koupenova et al. recently demonstrated that influenza virus engulfment through platelets causes the release of complement factor C3 and the subsequent activation of neutrophils and NETosis [31].

Similarly, Cytomegalovirus (CMV) was shown to binds to platelets through TLR2, which triggers platelet activation and secretion and results in enhanced platelet interaction with neutrophils [32,33]. On both platelet surface and in intracellular compartments, TLR3 was found to be responsible for recognizing double-stranded RNA viruses [28]. EMCV has been shown to interact with platelet TLR7, which leads to degranulation of platelets and direct interactions between platelets and neutrophils [26]. In the same manner, activated platelets express TLR9 on their surface and ensure the sequestering of viral DNA [34]. During viral infections, PARs on platelets, endothelial cells, and leukocytes modulate innate immune responses and affect TLR-dependent responses both positively and negatively [35]. The presence of other classes of PRRs involved in the viral recognition, such as retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I), was confirmed at the level of megakaryocytes when responding to type 1 interferons. However, RIG-I expression in platelets is yet to be known [28].

Platelets also express several complement receptors, such as the complement receptor type II (CR2) and Epstein–Barr virus receptor, which act as receptors for viruses that result in multiple antimicrobial defense functions, including lysis, opsonization, and chemotaxis [36]. These receptors allow platelets to capture different types of viruses. For example, GPIIb/IIIa or α2β3 integrin recognizes the RGD sequence of Adenovirus and Hantavirus. The Dendritic Cell-Specific ICAM3-Grabbing Non-Integrin (DC-SIGN) receptor contained in granules is able to bind dengue virus (DENV) when expressed on the platelet surface. Integrin α2β1 and glycoprotein GPVI (major collagen receptor) are capable of binding rotavirus VP4 protein and hepatitis C virus (HCV), respectively [6]. Platelets also express a receptor for Coxsackie viruses, the Coxsackie-Adeno Receptor (CAR) [37]. These overall receptor–virus interactions cited above are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of platelet receptors involved in platelet–virus interactions according to Flaujac et al. [6].

There are two main families of platelet cytosolic sensors: NLRs, including oligomerization domain-containing nucleotide-binding domain 2 (NOD2) and leucine-rich repeat-containing pyrin 3 (NLRP3) [38,39]. A major function of the NLRP3 receptor is to activate caspase-1, which converts pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into active cytokines [40]. The cytokine processing and assembly of the inflammasomes in nucleated cells are triggered by two signals: transcription of cytokines and activation of the inflammasome components [41]. A recent study has shown that platelets are activated during Chikungunya virus infection and that this can lead to the formation of NLRP3 inflammasomes and the release of inflammatory eicosanoids, cytokines, and chemokines [42].

It would also be relevant to point out that inflammation can be induced by PEVs in part due to their influence on cell–cell interactions and their involvement in inducing adhesion molecules in different types of cells and their ability to release cytokines. Additionally, PEVs contain proinflammatory cytokines like interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor [43]. In COVID-19 patients, PEV-associated tissue factor activity was associated with thromboembolic events at a higher level [44,45,46]. In addition, there has also been a significant growth in circulating platelet-derived EVs, which are the major source of CD142 in plasma [47,48]. In studies on HIV and PEVs, it has been demonstrated that vesicles can facilitate viral reproduction, modify receptor expression to make cells more receptive to infection, promote viral replication and stability via host molecules, and activate latent viruses by uninfected cell EVs [49,50,51,52,53].

4. Conclusions

Platelets are essential for vascular repair and maintenance of hemostasis, but they also play an important role in immunity by expressing numerous integrins as well as cytokine/chemokine receptors. Platelets are increasingly recognized as immune cells due to new platelet functions emerging over time. Platelets are now known to interact with all types of pathogens and most importantly viruses. Indeed, the platelet response, thought to be only simple but effective in hemostasis, is for sure extremely complex and targeted in inflammatory and immune responses. In order to gain a clear understanding of antiplatelet therapies’ effects on viral infections, further studies are needed to explain the role of platelets in viral infections. By studying platelets during viral infections, we will be able to predict whether they will be beneficial or detrimental.

Author Contributions

All authors wrote, read, and approved the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This review was supported by Balvi Filantropic Fund (PR-BLV-20220527).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any competing interests.

Abbreviations

| ACE2 | Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 |

| ADP | Adenosine DiPhosphate |

| CAR | Coxsackie-Adenovirus Receptor |

| CCL | Chemokine Ligand |

| CCR | Chemokine receptor |

| CD40L | CD40 Ligand |

| CH | Chemokines |

| CK | Cytokines |

| CLEC-2 | C-type Lectin-like Protein-2 |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 19 |

| CR-2 | Complement Receptor 2 |

| DC-SIGN | Dendritic Cell-Specific Intercellular adhesion molecule-3-Grabbing Non-integrin |

| DENV | Dengue Virus |

| EBV | Epstein–Barr Virus |

| EV | Extracellular Vesicles |

| FasL | Apoptosis Stimulating Fragment Ligand |

| GP | Glycoproteins |

| HBV | Hepatitis B virus |

| HCV | Hepatitis C Virus |

| HCMV | Human Cyto-Megalo Virus |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| ICAM-3 | InterCellular Adhesion Molecule |

| IFITM 3 | IFN-Sensitive Viral Restriction Factor |

| IFNAR | Interferon-α/β receptor |

| IgG | Immunoglobuline G |

| IL | Interleukine |

| LPS | LipoPolySaccharide |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| MIP-1α | Macrophage Inflammatory Protein 1-alpha |

| MK | Megakaryocyte |

| miRNA | Micro Ribonuncleic Acid |

| NETs | Neutrophil Extracellular Traps |

| OCS | Open Canalicular System |

| PAMP | Pathogen-Associated Molecular Pattern |

| PEV | Platelets Extra-Vesicles |

| PMNC | Polymorphonuclear Cells |

| PRR | Pattern-Recognition Receptor |

| PSGL-1 | P-Selectin Glycoprotein Ligand |

| RANTES | Regulated Upon Activation, Normal T cell Expressed, and Secreted |

| RGD | Arginine-Glycine-Aspartic Acid sequence |

| SAPK | Stress-Activated Protein Kinase |

| SARS-CoV | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus |

| TLR | Toll-Like Receptor |

| TRAIL | TNF-Related Apoptosis-Inducing Ligand |

| VCAM | Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule |

| vWF | Von Willebrand Factor |

Appendix A

Platelets can take up infectious agents and stimulate neutrophil activation and production of antimicrobial NETs. Platelets contain numerous pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that are released into the extracellular space upon activation. Platelets contain several types of RNA that can be exported by PMPs and can then be translated into proteins. CD40L expression by platelets allows them to interact with and activate and/or inhibit different cells of the immune system and platelet content can contribute to immune cell function and modify adaptive immunity.

References

- Nieswandt, B.; Watson, S. Platelet-collagen interaction: Is GPVI the central receptor? Blood 2003, 102, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J. Platelets. Lancet 2000, 355, 1531–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kadiry, A.; Merhi, Y. The Role of the Proteasome in Platelet Function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira-de-Abreu, A.; Campbell, R.; Weyrich, A.; Zimmerman, G. Platelets: Versatile effector cells in hemostasis, inflammation, and the immune continuum. Semin. Immunopathol. 2012, 34, 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colvin, B. Physiology of haemostasis. Vox Sang. 2004, 87 (Suppl. S1), 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flaujac, C.; Boukour, S.; Cramer-Borde, E. Platelets and viruses: An ambivalent relationship. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2010, 67, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyrich, A.; Zimmerman, G. Platelets: Signaling cells in the immune continuum. Trends Immunol. 2004, 25, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabrouk, M.; Guessous, F.; Naya, A.; Merhi, Y.; Zaid, Y. The Pathophysiological Role of Platelet-Derived Extracellular Vesicles. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Clemetson, K. Platelets and pathogens. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2010, 67, 495–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeaman, M. Bacterial-platelet interactions: Virulence meets host defense. Future Microbiol. 2010, 5, 471–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zufferey, A.; Speck, E.; Machlus, K.; Aslam, R.; Guo, L.; McVey, M.; Kim, M.; Kapur, R.; Boilard, E.; Italiano, J.E., Jr.; et al. Mature murine megakaryocytes present antigen-MHC class I molecules to T cells and transfer them to platelets. Blood Adv. 2017, 1, 1773–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cecchetti, L.; Tolley, N.; Michetti, N.; Bury, L.; Weyrich, A.; Gresele, P. Megakaryocytes differentially sort mRNAs for matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors into platelets: A mechanism for regulating synthetic events. Blood 2011, 118, 1903–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negrotto, S.; De Giusti, C.J.; Lapponi, M.; Etulain, J.; Rivadeneyra, L.; Pozner, R.; Gomez, R.; Schattner, M. Expression and functionality of type I interferon receptor in the megakaryocytic lineage. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2011, 9, 2477–2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaulieu, L.; Lin, E.; Morin, K.; Tanriverdi, K.; Freedman, J. Regulatory effects of TLR2 on megakaryocytic cell function. Blood 2011, 117, 5963–5974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivadeneyra, L.; Pozner, R.; Meiss, R.; Fondevila, C.; Gomez, R.; Schattner, M. Poly (I:C) downregulates platelet production and function through type I interferon. Thromb. Haemost. 2015, 114, 982–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, S. Elie Metchnikoff: Father of natural immunity. Eur. J. Immunol. 2008, 38, 3257–3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, L.; Zhao, C.; Zhu, X.; Hou, Y.; Jun, P.; Hou, M. Contributions of TRAIL-mediated megakaryocyte apoptosis to impaired megakaryocyte and platelet production in immune thrombocytopenia. Blood 2010, 116, 4307–4316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowa, J.; Crist, S.; Ratliff, T.; Elzey, B. Platelet influence on T- and B-cell responses. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. (Warsz) 2009, 57, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stout, R.; Suttles, J. The many roles of CD40 in cell-mediated inflammatory responses. Immunol. Today 1996, 17, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senhaji, N.; Kojok, K.; Darif, Y.; Fadainia, C.; Zaid, Y. The Contribution of CD40/CD40L Axis in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: An Update. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damas, J.; Waehre, T.; Yndestad, A.; Otterdal, K.; Hognestad, A.; Solum, N.; Gullestad, L.; Froland, S.; Aukrust, P. Interleukin-7-mediated inflammation in unstable angina: Possible role of chemokines and platelets. Circulation 2003, 107, 2670–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Lehar, S.; Bevan, M. Augmented IL-7 signaling during viral infection drives greater expansion of effector T cells but does not enhance memory. J. Immunol. 2006, 177, 4458–4463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, B.; Adrover, J.; Baxter-Stoltzfus, A.; Borczuk, A.; Cools-Lartigue, J.; Crawford, J.; Dassler-Plenker, J.; Guerci, P.; Huynh, C.; Knight, J.; et al. Targeting potential drivers of COVID-19: Neutrophil extracellular traps. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217, e20200652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rondina, M.; Schwertz, H.; Harris, E.; Kraemer, B.; Campbell, R.; Mackman, N.; Grissom, C.; Weyrich, A.; Zimmerman, G. The septic milieu triggers expression of spliced tissue factor mRNA in human platelets. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2011, 9, 748–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weyrich, A.; Denis, M.; Schwertz, H.; Tolley, N.; Foulks, J.; Spencer, E.; Kraiss, L.; Albertine, K.; McIntyre, T.; Zimmerman, G. mTOR-dependent synthesis of Bcl-3 controls the retraction of fibrin clots by activated human platelets. Blood 2007, 109, 1975–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koupenova, M.; Vitseva, O.; MacKay, C.; Beaulieu, L.; Benjamin, E.; Mick, E.; Kurt-Jones, E.; Ravid, K.; Freedman, J. Platelet-TLR7 mediates host survival and platelet count during viral infection in the absence of platelet-dependent thrombosis. Blood 2014, 124, 791–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Atri, L.P.; Etulain, J.; Rivadeneyra, L.; Lapponi, M.; Centurion, M.; Cheng, K.; Yin, H.; Schattner, M. Expression and functionality of Toll-like receptor 3 in the megakaryocytic lineage. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2015, 13, 839–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, I.; Storad, Z.; Filipiak, L.; Huss, C.; Meikle, C.; Worth, R.; Wuescher, L. From Classical to Unconventional: The Immune Receptors Facilitating Platelet Responses to Infection and Inflammation. Biology 2020, 9, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cognasse, F.; Nguyen, K.; Damien, P.; McNicol, A.; Pozzetto, B.; Hamzeh-Cognasse, H.; Garraud, O. The Inflammatory Role of Platelets via Their TLRs and Siglec Receptors. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu, L.; Freedman, J. The role of inflammation in regulating platelet production and function: Toll-like receptors in platelets and megakaryocytes. Thromb. Res. 2010, 125, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koupenova, M.; Corkrey, H.; Vitseva, O.; Manni, G.; Pang, C.; Clancy, L.; Yao, C.; Rade, J.; Levy, D.; Wang, J.; et al. The role of platelets in mediating a response to human influenza infection. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maouia, A.; Rebetz, J.; Kapur, R.; Semple, J. The Immune Nature of Platelets Revisited. Transfus. Med. Rev. 2020, 34, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assinger, A.; Kral, J.; Yaiw, K.; Schrottmaier, W.; Kurzejamska, E.; Wang, Y.; Mohammad, A.; Religa, P.; Rahbar, A.; Schabbauer, G.; et al. Human cytomegalovirus-platelet interaction triggers toll-like receptor 2-dependent proinflammatory and proangiogenic responses. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2014, 34, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thon, J.; Peters, C.; Machlus, K.; Aslam, R.; Rowley, J.; Macleod, H.; Devine, M.; Fuchs, T.; Weyrich, A.; Semple, J.; et al. T granules in human platelets function in TLR9 organization and signaling. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 198, 561–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniak, S.; Mackman, N. Multiple roles of the coagulation protease cascade during virus infection. Blood 2014, 123, 2605–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunez, D.; Charriaut-Marlangue, C.; Barel, M.; Benveniste, J.; Frade, R. Activation of human platelets through gp140, the C3d/EBV receptor (CR2). Eur. J. Immunol. 1987, 17, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrotto, S.; de Giusti, C.J.; Rivadeneyra, L.; Ure, A.; Mena, H.; Schattner, M.; Gomez, R. Platelets interact with Coxsackieviruses B and have a critical role in the pathogenesis of virus-induced myocarditis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2015, 13, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, S.; Hu, L.; Zhai, L.; Xue, R.; Ye, J.; Chen, L.; Cheng, G.; Mruk, J.; Kunapuli, S.; et al. Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 2 receptor is expressed in platelets and enhances platelet activation and thrombosis. Circulation 2015, 131, 1160–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hottz, E.; Bozza, F.; Bozza, P. Platelets in Immune Response to Virus and Immunopathology of Viral Infections. Front. Med. 2018, 5, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, K.; Shi, X.; Wang, Y.; Huang, H.; Zhuang, Y.; Cai, T.; Wang, F.; Shao, F. Cleavage of GSDMD by inflammatory caspases determines pyroptotic cell death. Nature 2015, 526, 660–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hottz, E.; Lopes, J.; Freitas, C.; Valls-de-Souza, R.; Oliveira, M.; Bozza, M.; Da Poian, A.; Weyrich, A.; Zimmerman, G.; Bozza, F.; et al. Platelets mediate increased endothelium permeability in dengue through NLRP3-inflammasome activation. Blood 2013, 122, 3405–3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Azevedo-Quintanilha, I.G.; Campos, M.; Monteiro, A.T.; Nascimento, A.D.; Calheiros, A.; Oliveira, D.; Dias, S.; Soares, V.; Santos, J.; Tavares, I.; et al. Increased platelet activation and platelet-inflammasome engagement during chikungunya infection. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 958820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slomka, A.; Urban, S.; Lukacs-Kornek, V.; Zekanowska, E.; Kornek, M. Large Extracellular Vesicles: Have We Found the Holy Grail of Inflammation? Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guervilly, C.; Bonifay, A.; Burtey, S.; Sabatier, F.; Cauchois, R.; Abdili, E.; Arnaud, L.; Lano, G.; Pietri, L.; Robert, T.; et al. Dissemination of extreme levels of extracellular vesicles: Tissue factor activity in patients with severe COVID-19. Blood Adv. 2021, 5, 628–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, Y.; Puhm, F.; Allaeys, I.; Naya, A.; Oudghiri, M.; Khalki, L.; Limami, Y.; Zaid, N.; Sadki, K.; El Haj, R.B.; et al. Platelets Can Associate with SARS-Cov-2 RNA and Are Hyperactivated in COVID-19. Circ. Res. 2020, 127, 1404–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puhm, F.; Allaeys, I.; Lacasse, E.; Dubuc, I.; Galipeau, Y.; Zaid, Y.; Khalki, L.; Belleannee, C.; Durocher, Y.; Brisson, A.; et al. Platelet activation by SARS-CoV-2 implicates the release of active tissue factor by infected cells. Blood Adv. 2022, 6, 3593–3605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappellano, G.; Raineri, D.; Rolla, R.; Giordano, M.; Puricelli, C.; Vilardo, B.; Manfredi, M.; Cantaluppi, V.; Sainaghi, P.; Castello, L.; et al. Circulating Platelet-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Are a Hallmark of Sars-Cov-2 Infection. Cells 2021, 10, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, I.; Klocke, A.; Alex, M.; Kotzsch, M.; Luther, T.; Morgenstern, E.; Zieseniss, S.; Zahler, S.; Preissner, K.; Engelmann, B. Intravascular tissue factor initiates coagulation via circulating microvesicles and platelets. FASEB J. 2003, 17, 476–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubrovsky, L.; Ward, A.; Choi, S.; Pushkarsky, T.; Brichacek, B.; Vanpouille, C.; Adzhubei, A.; Mukhamedova, N.; Sviridov, D.; Margolis, L.; et al. Inhibition of HIV Replication by Apolipoprotein A-I Binding Protein Targeting the Lipid Rafts. mBio 2020, 11, e02956-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjit, S.; Kodidela, S.; Sinha, N.; Chauhan, S.; Kumar, S. Extracellular Vesicles from Human Papilloma Virus-Infected Cervical Cancer Cells Enhance HIV-1 Replication in Differentiated U1 Cell Line. Viruses 2020, 12, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhamedova, N.; Hoang, A.; Dragoljevic, D.; Dubrovsky, L.; Pushkarsky, T.; Low, H.; Ditiatkovski, M.; Fu, Y.; Ohkawa, R.; Meikle, P.; et al. Exosomes containing HIV protein Nef reorganize lipid rafts potentiating inflammatory response in bystander cells. PLoS Pathog. 2019, 15, e1007907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouattara, L.; Anderson, S.; Doncel, G. Seminal exosomes and HIV-1 transmission. Andrologia 2018, 50, e13220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatua, A.; Taylor, H.; Hildreth, J.; Popik, W. Exosomes packaging APOBEC3G confer human immunodeficiency virus resistance to recipient cells. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danon, D.; Jerushalmy, Z.; De Vries, A. Incorporation of influenza virus in human blood platelets in vitro. Electron microscopical observation. Virology 1959, 9, 719–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koupenova, M.; Clancy, L.; Corkrey, H.; Freedman, J. Circulating Platelets as Mediators of Immunity, Inflammation, and Thrombosis. Circ. Res. 2018, 122, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allaoui, A.; Khawaja, A.; Badad, O.; Naciri, M.; Lordkipanidze, M.; Guessous, F.; Zaid, Y. Platelet Function in Viral Immunity and SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2021, 47, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koupenova, M.; Corkrey, H.; Vitseva, O.; Tanriverdi, K.; Somasundaran, M.; Liu, P.; Soofi, S.; Bhandari, R.; Godwin, M.; Parsi, K.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Initiates Programmed Cell Death in Platelets. Circ. Res. 2021, 129, 631–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Schroeder, S.; Kruger, N.; Herrler, T.; Erichsen, S.; Schiergens, T.; Herrler, G.; Wu, N.; Nitsche, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181, 271–280.e278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.; Wang, X.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.; et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, Y.; Guessous, F. The ongoing enigma of SARS-CoV-2 and platelet interaction. Res. Pract. Thromb. Haemost. 2022, 6, e12642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manne, B.; Denorme, F.; Middleton, E.; Portier, I.; Rowley, J.; Stubben, C.; Petrey, A.; Tolley, N.; Guo, L.; Cody, M.; et al. Platelet gene expression and function in patients with COVID-19. Blood 2020, 136, 1317–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clancy, L.; Beaulieu, L.; Tanriverdi, K.; Freedman, J. The role of RNA uptake in platelet heterogeneity. Thromb. Haemost. 2017, 117, 948–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowley, J.; Oler, A.; Tolley, N.; Hunter, B.; Low, E.; Nix, D.; Yost, C.; Zimmerman, G.; Weyrich, A. Genome-wide RNA-seq analysis of human and mouse platelet transcriptomes. Blood 2011, 118, e101–e111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, S.; Zhang, J.; Fang, Y.; Lu, S.; Wu, J.; Zheng, X.; Deng, F. SARS-CoV-2 interacts with platelets and megakaryocytes via ACE2-independent mechanism. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Yang, L.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, M.; Zhao, X.; Xie, Y.; Yang, Y.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 binds platelet ACE2 to enhance thrombosis in COVID-19. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackman, N.; Antoniak, S.; Wolberg, A.; Kasthuri, R.; Key, N. Coagulation Abnormalities and Thrombosis in Patients Infected With SARS-CoV-2 and Other Pandemic Viruses. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2020, 40, 2033–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, S.; Baindara, P.; Mandal, S. Molecular pathogenesis of secondary bacterial infection associated to viral infections including SARS-CoV-2. J. Infect. Public Health 2020, 13, 1397–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniak, S. The coagulation system in host defense. Res. Pract. Thromb. Haemost. 2018, 2, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VLe, B.; Schneider, J.; Boergeling, Y.; Berri, F.; Ducatez, M.; Guerin, J.; Adrian, I.; Errazuriz-Cerda, E.; Frasquilho, S.; Antunes, L.; et al. Platelet activation and aggregation promote lung inflammation and influenza virus pathogenesis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 191, 804–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucker-Franklin, D.; Seremetis, S.; Zheng, Z. Internalization of human immunodeficiency virus type I and other retroviruses by megakaryocytes and platelets. Blood 1990, 75, 1920–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouri, Y.; Borkowsky, W.; Nardi, M.; Karpatkin, S.; Basch, R. Human megakaryocytes have a CD4 molecule capable of binding human immunodeficiency virus-1. Blood 1993, 81, 2664–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youssefian, T.; Drouin, A.; Masse, J.; Guichard, J.; Cramer, E. Host defense role of platelets: Engulfment of HIV and Staphylococcus aureus occurs in a specific subcellular compartment and is enhanced by platelet activation. Blood 2002, 99, 4021–4029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemetson, K.; Clemetson, J.; Proudfoot, A.; Power, C.; Baggiolini, M.; Wells, T. Functional expression of CCR1, CCR3, CCR4, and CXCR4 chemokine receptors on human platelets. Blood 2000, 96, 4046–4054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, J.G. Platelets are covercytes, not phagocytes: Uptake of bacteria involves channels of the open canalicular system. Platelets 2005, 16, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, R.; Schwertz, H.; Hottz, E.; Rowley, J.; Manne, B.; Washington, A.; Hunter-Mellado, R.; Tolley, N.; Christensen, M.; Eustes, A.; et al. Human megakaryocytes possess intrinsic antiviral immunity through regulated induction of IFITM3. Blood 2019, 133, 2013–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, L.; Outlioua, A.; Anginot, A.; Akarid, K.; Arnoult, D. RNA viruses promote activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome through cytopathogenic effect-induced potassium efflux. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hottz, E.; Medeiros-de-Moraes, I.; Vieira-de-Abreu, A.; de Assis, E.; Vals-de-Souza, R.; Castro-Faria-Neto, H.; Weyrich, A.; Zimmerman, G.; Bozza, F.; Bozza, P. Platelet activation and apoptosis modulate monocyte inflammatory responses in dengue. J. Immunol. 2014, 193, 1864–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzalli, M.; Smith, A.; Jurado, K.; Iwasaki, A.; Garlick, J.; Kagan, J. An Antiviral Branch of the IL-1 Signaling Pathway Restricts Immune-Evasive Virus Replication. Mol. Cell 2018, 71, 825–840.e826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondina, M.; Weyrich, A. Dengue virus pirates human platelets. Blood 2015, 126, 286–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, Y.; Guessous, F.; Puhm, F.; Elhamdani, W.; Chentoufi, L.; Morris, A.; Cheikh, A.; Jalali, F.; Boilard, E.; Flamand, L. Platelet reactivity to thrombin differs between patients with COVID-19 and those with ARDS unrelated to COVID-19. Blood Adv. 2021, 5, 635–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darif, D.; Hammi, I.; Kihel, A.; El Idrissi Saik, I.; Guessous, F.; Akarid, K. The pro-inflammatory cytokines in COVID-19 pathogenesis: What goes wrong? Microb. Pathog. 2021, 153, 104799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archambault, A.; Zaid, Y.; Rakotoarivelo, V.; Turcotte, C.; Dore, E.; Dubuc, I.; Martin, C.; Flamand, O.; Amar, Y.; Cheikh, A.; et al. High levels of eicosanoids and docosanoids in the lungs of intubated COVID-19 patients. FASEB J. 2021, 35, e21666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, Y.; Dore, E.; Dubuc, I.; Archambault, A.; Flamand, O.; Laviolette, M.; Flamand, N.; Boilard, E.; Flamand, L. Chemokines and eicosanoids fuel the hyperinflammation within the lungs of patients with severe COVID-19. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 148, 368–380.e363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boilard, E.; Pare, G.; Rousseau, M.; Cloutier, N.; Dubuc, I.; Levesque, T.; Borgeat, P.; Flamand, L. Influenza virus H1N1 activates platelets through FcgammaRIIA signaling and thrombin generation. Blood 2014, 123, 2854–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holme, P.; Muller, F.; Solum, N.; Brosstad, F.; Froland, S.; Aukrust, P. Enhanced activation of platelets with abnormal release of RANTES in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. FASEB J. 1998, 12, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Othman, M.; Labelle, A.; Mazzetti, I.; Elbatarny, H.; Lillicrap, D. Adenovirus-induced thrombocytopenia: The role of von Willebrand factor and P-selectin in mediating accelerated platelet clearance. Blood 2007, 109, 2832–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsounas, A.; Schlaak, J.; Lempicki, R. CCL5: A double-edged sword in host defense against the hepatitis C virus. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 30, 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannacone, M.; Sitia, G.; Isogawa, M.; Whitmire, J.; Marchese, P.; Chisari, F.; Ruggeri, Z.; Guidotti, L. Platelets prevent IFN-alpha/beta-induced lethal hemorrhage promoting CTL-dependent clearance of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurti, C.; Peat, R.; Cutting, M.; Rothwell, S. Platelet adhesion to dengue-2 virus-infected endothelial cells. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2002, 66, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaid, Y.; Merhi, Y. Implication of Platelets in Immuno-Thrombosis and Thrombo-Inflammation. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 863846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ma, F.; Luo, R.; Xu, X.; Zhou, G.; Wang, J.; Niu, J.; et al. Platelets mediate inflammatory monocyte activation by SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. J. Clin. Invest. 2022, 132, e150101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hottz, E.; Quirino-Teixeira, A.; Valls-de-Souza, R.; Zimmerman, G.; Bozza, F.; Bozza, P. Platelet function in HIV plus dengue coinfection associates with reduced inflammation and milder dengue illness. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torun, S.; Kesim, C.; Suner, A.; Yildirim, B.B.; Ozen, O.; Akcay, S. Influenza viruses and SARS-CoV-2 in adult: ‘Similarities and differences’. Tuberk Toraks 2021, 69, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Carestia, A.; McDonald, B.; Zucoloto, A.; Grosjean, H.; Davis, R.; Turk, M.; Naumenko, V.; Antoniak, S.; Mackman, N.; et al. Platelet-Mediated NET Release Amplifies Coagulopathy and Drives Lung Pathology During Severe Influenza Infection. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 772859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahn, A.; Jennings, N.; Ouwehand, W.; Allain, J. Hepatitis C virus interacts with human platelet glycoprotein VI. J. Gen. Virol. 2006, 87, 2243–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, N.; Jespersen, S.; Gaardbo, J.; Arnbjerg, C.; Clausen, M.; Kjaer, M.; Gerstoft, J.; Ballegaard, V.; Ostrowski, S.; Nielsen, S. Impaired Platelet Aggregation and Rebalanced Hemostasis in Patients with Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjo, A.; Satoi, J.; Ohnishi, A.; Maruno, J.; Fukata, M.; Suzuki, N. Role of elevated platelet-associated immunoglobulin G and hypersplenism in thrombocytopenia of chronic liver diseases. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2003, 18, 638–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagamine, T.; Ohtuka, T.; Takehara, K.; Arai, T.; Takagi, H.; Mori, M. Thrombocytopenia associated with hepatitis C viral infection. J. Hepatol. 1996, 24, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pockros, P.; Duchini, A.; McMillan, R.; Nyberg, L.; McHutchison, J.; Viernes, E. Immune thrombocytopenic purpura in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2002, 97, 2040–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, T.; Ichida, T.; Matsuda, Y.; Sugitani, S.; Sugiyama, M.; Kato, T.; Miyazaki, H.; Asakura, H. Reduced expression of thrombopoietin is involved in thrombocytopenia in human and rat liver cirrhosis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 1998, 13, 907–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, T., III; Somberg, K.; Meng, Y.; Cohen, R.; Heid, C.; de Sauvage, F.; Shuman, M. Thrombopoietin levels in patients with cirrhosis before and after orthotopic liver transplantation. Ann. Intern. Med. 1997, 127, 285–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peck-Radosavljevic, M.; Zacherl, J.; Meng, Y.; Pidlich, J.; Lipinski, E.; Langle, F.; Steininger, R.; Muhlbacher, F.; Gangl, A. Is inadequate thrombopoietin production a major cause of thrombocytopenia in cirrhosis of the liver? J. Hepatol. 1997, 27, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Almeida, A.; Campos-de-Magalhaes, M.; de Melo Marcal, O.; Brandao-Mello, C.; Okawa, M.; de Oliveira, R.; Espirito-Santo, M.; Yoshida, C.; Lampe, E. Hepatitis C virus-associated thrombocytopenia: A controlled prospective, virological study. Ann. Hematol. 2004, 83, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Nardi, M.; Borkowsky, W.; Li, Z.; Karpatkin, S. Role of molecular mimicry of hepatitis C virus protein with platelet GPIIIa in hepatitis C-related immunologic thrombocytopenia. Blood 2009, 113, 4086–4093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamaia, S.; Li, C.; Allain, J. The dynamics of hepatitis C virus binding to platelets and 2 mononuclear cell lines. Blood 2001, 98, 2293–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirino-Teixeira, A.; Rozini, S.; Barbosa-Lima, G.; Coelho, D.; Carneiro, P.; Mohana-Borges, R.; Bozza, P.; Hottz, E. Inflammatory signaling in dengue-infected platelets requires translation and secretion of nonstructural protein 1. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 2018–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trugilho, M.; Hottz, E.; Brunoro, G.; Teixeira-Ferreira, A.; Carvalho, P.; Salazar, G.; Zimmerman, G.; Bozza, F.; Bozza, P.; Perales, J. Platelet proteome reveals novel pathways of platelet activation and platelet-mediated immunoregulation in dengue. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michels, M.; Alisjahbana, B.; De Groot, P.; Indrati, A.; Fijnheer, R.; Puspita, M.; Dewi, I.; van de Wijer, L.; de Boer, E.; Roest, M.; et al. Platelet function alterations in dengue are associated with plasma leakage. Thromb. Haemost. 2014, 112, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, A.; Nandi, D.; Batra, H.; Singhal, R.; Annarapu, G.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Seth, T.; Dar, L.; Medigeshi, G.; Vrati, S.; et al. Platelet activation determines the severity of thrombocytopenia in dengue infection. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).