Abstract

Mastocytosis is a heterogeneous group of diseases associated with excessive proliferation and accumulation of mast cells in different organs. Recent studies have demonstrated that patients suffering from mastocytosis face an increased risk of melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer. The cause of this has not yet been clearly identified. In the literature, the potential influence of several factors has been suggested, including genetic background, the role of cytokines produced by mast cells, iatrogenic and hormonal factors. The article summarizes the current state of knowledge regarding the epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of skin neoplasia in mastocytosis patients.

1. Introduction

Mastocytosis is a heterogeneous group of diseases associated with excessive proliferation and accumulation of mast cells (MSc) in different organs. The most commonly affected organs are bone marrow, the skin, the liver, the spleen, and the lymph nodes [1]. Recent studies have demonstrated that patients suffering from mastocytosis face an increased risk of melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) [2,3,4]. The cause of this has not yet been clearly identified.

In the literature, the potential influence of several factors has been suggested, including genetic background [5,6,7,8,9], the role of cytokines produced by MCs [10,11,12,13,14,15], iatrogenic [16], and hormonal factors [17,18].

The aim of this study was to summarize the current state of knowledge regarding the pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of melanoma and NMSC in patients with mastocytosis.

2. Mastocytosis—Classification and Epidemiology

Urticaria pigmentosa, (UP) currently termed maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis, was first described in 1869 by Nettleship and Tay [19]. In 1936, Sezary first described the first case of mastocytosis [20,21].

In the decades since, the classification of the disease, diagnostic criteria, and treatment approach have evolved.

According to the current World Health Organization (WHO) classification published in 2016, mastocytosis is divided into cutaneous mastocytosis (CM), systemic mastocytosis (SM), and mast cell sarcoma [22].

Mastocytosis is a rare disorder, and there is no accurate data on the frequency of the disease. The estimated prevalence of mastocytosis (both systemic and cutaneous) is 1:10,000. The prevalence of systemic mastocytosis in Europe is 1 in every 8000 to 10,000 [23]. In a population-based study conducted in the United States, the incidence of systemic mastocytosis in adults was higher among Caucasians compared to African Americans (0.056 vs. 0.018 per 100,000) [24].

Mastocytosis is a disease that can occur at any age. In adults, the systemic form is predominant, whereas in children, it is usually limited to the skin, with a tendency to resolve spontaneously around puberty [25,26].

Most patients with mastocytosis experience only cutaneous involvement, and maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis (urticaria pigmentosa) is the most commonly diagnosed variant of the disease, occurring in about 80% of patients [25,27,28].

3. Epidemiological Link between Mastocytosis and Skin Cancer

Numerous publications discuss comorbidities in patients with mastocytosis, including solid cancers (especially melanoma and NMSC) and cardiovascular diseases (mostly venous thromboembolism [VTE] [2,3,4]).

Until January 2023, nine case reports [3,4,16,29,30,31,32,33,34,35] and two population studies [2,3] analyzing correlations between the incidence of mastocytosis, melanoma, and NMSC have been published in the PubMed database. The summary of these findings is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of case reports describing patients with mastocytosis and malignant melanocytic tumors.

Olsen et al. [2] conducted a population-based cohort study that included 687 Danish patients (older than 14 years) diagnosed with systemic mastocytosis (with or without urticaria pigmentosa) and 68,700 controls from the general population. In this registry-based study, the incidence of solid cancers, VTE, myocardial infarction (MI), and stroke was analyzed during a 15-year period (1997–2012). It was found that the melanoma risk was about 7.5 times higher and the NMSC risk was around 2.5 times higher in mastocytosis patients compared to the general population. Additionally, melanoma was more advanced at the time of diagnosis compared to the controls (stage I-II diagnosis in 64.3% of SM patients vs. 79.3% in controls; stage III–IV in 14.3% vs. 12.0%, respectively; unknown stage in 21.4% vs. 8.8%, respectively). As discussed by the authors, SM patients are frequently managed by dermatologists, which could influence the detection of skin malignancy. It should be emphasized that the study described only the incidence of melanoma and NMSC in patients with mastocytosis without multivariate analysis including other known melanoma risk factors, such as ultraviolet radiation (UV) treatments, and concerned an exclusively Caucasian population. Interestingly, the study did not show an increased risk of breast cancer, lung cancer, or colorectal cancer [2].

In another study, Hagglund et al. [3] examined a group of 81 Swedish patients diagnosed with SM between 2007 and 2011. Melanoma was diagnosed in four patients (three of whom were also diagnosed with UP). The study showed that in patients diagnosed with SM, there was a 5% risk of developing melanoma, compared to 1.2–1.6% in the general Swedish population. The researchers emphasized that none of the patients had been treated with phototherapy in the past.

The remaining data come from case reports/case series and record 14 melanoma cases in 13 patients (4 males and 9 females), with a mean Breslow thickness of 1.13 mm (median 0.55 mm [0.1–5.6 mm]). In this group, most patients were diagnosed with cutaneous mastocytosis and six with SM. Only one of the reported patients received psolaren ultraviolet radiation (PUVA) therapy [3,4,16,29,30,31,32,33,34].

4. Pathogenetic Link between Mastocytosis and Skin Cancer

The precise pathogenetic link explaining the increased risk of skin cancer in mastocytosis patients has not been elucidated. In the literature, the potential contribution of several factors has been suggested, including genetic background, cytokines, neuropeptides, and hormonal and iatrogenic factors.

4.1. Genetic Factors

KIT

MCs and melanocytes originate from hematopoietic stem cells and neural crest cells, respectively. Both cell lines express KIT [36,37,38]. Dysregulation of KIT occurs in multiple diseases. Besides mastocytosis and melanoma, it is also observed in gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) [39], lung cancer, acute myeloid leukemia, and germ cell tumors [40].

KIT encodes the Kit receptor, which is physiologically activated by its ligand—Stem Cell Factor (SCF). SCF is produced in a variety of cells, including fibroblasts and endothelial cells. Interactions between the KIT receptor and SCF are responsible for the recruitment of MC progenitors into tissues, the regulation of proliferation and survival, and the activation of mastocytes [1,41]. Somatic mutations that occur in KIT in the course of mastocytosis cause constitutive KIT activation even in the absence of SCF, which finally leads to the clonal proliferation of MCs in different organs. The most common KIT mutation, present in 80–90% of patients with SM, is an aspartic acid to valine substitution (D816V KIT mutation) [8,9,14].

As shown in the previous studies, mutations of KIT also occur in melanoma, though less frequently. According to the study by Pham et al., 3% of all melanoma cases harbor KIT mutations [42]. Interestingly, they are relatively frequent in melanoma of special anatomical locations—being reported in 30–39% of cases of mucosal melanoma, 20–36% of acral melanoma, and in 20–28% of melanoma cases developing on chronically sun-damaged skin [43,44,45]. In melanoma, KIT mutations show heterogeneous distribution through the gene, and they are detected most frequently in exon 11 (L576P) and exon 13 (K642E) [46].

Notably, the D816V KIT mutation has rarely been reported in melanoma [47]. In the AACR project, it was detected in 4 out of 785 melanoma cases [48].

It has been shown that Imatinib may be effective in patients with melanoma harboring c-KIT alterations [49]. Independently, a recently published study on the animal model showed that tumor-infiltrating MCs are associated with resistance to anti-PD-1 therapy, and combining anti-PD-1 with sunitinib/imatinib results in depletion of mast cells, leading to complete regression of melanoma [50].

Other studies showed that KIT mutations can also be indirectly associated with melanocyte proliferation. A mutated KIT receptor forms a protein complex with microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF) and SRC family kinases, leading to excessive activity [5]. Activated MITF affects the overexpression of genes related to melanocyte proliferation and survival (such as TBX2, BCL2, SOX10, CDK2, HIF1A, P35, and DIAPH1) [51].

Excessive activity of SRC kinases results in abnormal activation of nuclear transcription factors—signal transducer and activator transcription 3 (STAT3) and signal transducer and activator transcription 5 (STAT5)—and ultimately leads to increased proliferation of MCs and melanocytes [11].

4.2. Tumor Microenvironment

It has been suggested that MCs may promote the development of cancer by releasing mediators conducive to tumor development, angiogenesis, tissue remodeling, and affecting the adaptive immune response [10,52,53].

Among mediators produced by MCs, three groups have been distinguished, including pre-formed substances (serotonin, histamine, heparin, tryptase, and chymase), molecules synthesized after mastocyte stimulation (PAF, PDG2, and LTB4 and LTD4), and cytokines (IL-1, IL-3, IL-5, IL-8, IL-10, GM-CSF, TNF-α, TGF-β, and VEGF) [41].

Previous studies showed that MCs are present in the tumor microenvironment, including in basal cell carcinoma (BCC), squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and melanoma [53,54,55]. Patients diagnosed with BCC and melanoma have been found to have a higher density of dermal MCs [15,56,57]. Other studies showed a correlation between oral SCC progression and the increasing number of MCs within the tumor tissue [58].

The interaction between inflammatory and neoplastic cells in melanoma and NMSCs is complex [59,60,61,62]. It is interesting whether the presence of MCs in mastocytosis patients is secondary to the presence of skin malignancy or whether the increased number of MCs in the skin of patients with mastocytosis may lead to a higher risk of oncogenesis.

Interestingly, a study by Hart et al. [63] showed that MCs may contribute to the development of BCC through their immunosuppressive effect on sun-exposed skin. On the other hand, it has been shown that neoplastic cells can produce chemotactic factors for MCs, including IL-8 [15] and RANTES [64], and, as a result, induce recruitment of MCs into the tumor microenvironment. It was also noticed that melanoma cells, through the cytokines secreted into their microenvironment (TGF-β and IL-1) and their influence on upregulating C3 expression, induce a change in the MC phenotypes. This leads to increased secretion of cytokines, which promote tumor progression [15].

The interaction between immune and cancer cells in tumor stroma is complex but has been shown to be a crucial element affecting tumor progression in melanoma and NMSC. MCs present in the tumor microenvironment can exert both pro- and anti-tumor properties [65].

The immunosuppressive activity of MCs is connected with IL-10, TNF-α, and histamine [52]. On the other hand, mastocytes release cytokines with anti-tumor activity (IL-1, IL-4, and IL-6).

There is growing data connecting the expression of PD-1 receptors on MCs with tumor progression. Inhibitors of the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) radically improved survival times in patients with metastatic melanoma. Nevertheless, a significant proportion of patients are resistant to PD-1 inhibition (for anti-PD-1 monotherapy with nivolumab/pembrolizumab it is up to 60–70%, and for combination therapy with anti-CTLA-4 ipilimumab, it is 40–50%). Little is known about the predictive factors of this resistance [66].

Recently, Li et al. [67] showed that MCs in the tumor microenvironment may be a poor prognostic factor connected with resistance to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. According to the study, PD-1 antibodies activate MCs and lead to the release of histamine and tumor-promoting cytokines, which may subsequently reduce the effect of immunotherapy. Additionally, a stabilizer of the MC membrane, cromolyn sodium, was found to inhibit this effect. The authors suggested that inhibiting MC degranulation could be an effective solution to PD-1 immunotherapy resistance.

Other studies have also documented the role of histamine and tryptase in mastocyte-related tumor progression. It has been found that histamine released by MCs can induce tumor cell proliferation through H1 receptors. In contrast, suppression of the immune system is connected with interaction with H2 receptors [68].

This association is interesting in the context of a study by Fritz et al. [69], who found an association between improved survival in melanoma patients and treatment with desloratadine (HR = 0.46; 95% CI 0.29–0.73, p = 0.001) or loratadine (HR = 0.50; 95% CI 0.28–0.88, p = 0.02). Additional observations concerned the reduced risk of secondary cutaneous melanoma in patients receiving one of the aforementioned drugs.

Interestingly, tryptase exhibits pro-angiogenic activity through its ability to degrade the connective tissue matrix by activating matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) [70] and activating PAR-2 receptors located on endothelial cells [71,72].

MCs may also stimulate neoangiogenesis in melanoma and NMSC via the production of VEGF [64] and IL-6 [73]. Moreover, other MC products (heparin, histamine, tryptase, chymase, TGF-β, FGF-2, and IL-8) may stimulate endothelial cell proliferation [11,13].

4.3. Hormones and Neuropeptides as a Potential Link between Mastocytosis and Skin Cancer

4.3.1. Sex Hormones

Mastocytosis may affect both women and men, being slightly more frequent in males among children and more prevalent in females after puberty. Although the role of sex hormones remains unclear in mastocytosis pathogenesis, they are suspected to affect the course of the disease and possibly impact the risk of developing skin cancer. There are many discrepancies between the results of studies evaluating the influence of pregnancy on the symptoms of mastocytosis. Though the majority of papers describe deterioration or stabilization of the clinical course of mastocytosis [74,75,76], there was one study reporting clinical improvement and cessation of symptoms during pregnancy [77].

Evidence from in vitro studies shows activation of MCs by sex hormones. MCs express both estrogen and progesterone receptors on their surfaces. Estradiol leads to increased synthesis and release of MC mediators in vitro [77,78]. A study performed by Kirmaz et al. [79] proved that menstrual cycle-dependent alteration of sex hormone serum concentrations impacts the results of skin prick tests (displaying highest reactivity to allergens mid-cycle), most probably due to estrogen-related augmentation of MCs’ degranulation processes. The role of progesterone is less well documented. Progesterone seems to counteract estrogens, inhibiting MCs’ degranulation [80] and implying that the relative ratio of estrogen to progesterone receptors on MCs’ surfaces may be responsible for an uncertain disease prognosis during pregnancy. Interestingly, despite the expression of androgen receptors in MCs, testosterone treatment does not lead to MC degranulation [81].

Tamoxifen, a selective estrogen receptor modulator, was shown to inhibit MCs’ degradation and proliferation of human NMSC [82]. The effect of tamoxifen on melanoma evaluated in clinical trials is equivocal [83]. In patients with indolent systemic mastocytosis, tamoxifen showed limited efficacy [84].

There is no data regarding the effect of hormonal replacement therapy (HRT) on mastocytosis. However, HRT was shown to significantly increase the risk of melanoma (OR = 1.21) [85], BCC (HR = 1.16) [86], and SCC (IRR = 1.35 with every 5 years of using HRT) [87].

In recent years, the number of reports indicating the relationship between sex hormones and the development of melanoma and NMSC has grown [88]. Data from the nation-wide Norway Cancer Registry show that melanoma is the most common neoplasm during pregnancy and lactation [89]. In one epidemiological study on skin tumors among Dutch patients with mastocytosis, in a cohort of 269 mastocytosis patients in which 8 developed melanoma, males were significantly more frequently affected than females when compared to the non-melanoma group (p = 0.03) [90]. In another study analyzing 81 patients with systemic mastocytosis, 4 cases of melanoma were reported without sex predilection. However, both females diagnosed with melanoma were of premenopausal age (under 45 years old), whereas both males were over 60 years old [3]. This is in accordance with the European Cancer Information System, which estimated a higher incidence of melanoma among females younger than 45 years of age and a nearly two-fold greater melanoma risk in males older than 75 years of age [91]. Hitherto, studies have led to the conclusion that sex hormones may make females prior to menopause more susceptible to melanoma and imply possible involvement of sex hormones in melanoma, NMSC pathogenesis, and the clinical course of mastocytosis. Unfortunately, data regarding the sex of patients with melanoma and NMSC were not provided in one of the largest epidemiological studies on systemic mastocytosis [2]. Conversely, the summary of extracted cases (Table 1) shows a higher incidence of melanoma in females with mastocytosis. Hence, the low number of cases and available demographic data do not allow for unequivocal conclusions on the sex-related risk of melanoma in mastocytosis patients.

4.3.2. Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis

In a study by Antoniewicz et al. [92], significantly elevated serum concentrations of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) were reported in patients with mastocytosis when compared to the control group. These findings support the idea of an altered skin HPA (sHPA) axis in patients with mastocytosis. Moreover, Antoniewicz et al. underlined the potential role of α-Melanocyte Stimulating Hormone (α-MSH), supposedly responsible for skin lesion pigmentation in CM (urticaria pigmentosa). Along with ACTH, α-MSH arises from the proteolytic cleavage of proopiomelanocortin peptide, which is synthesized in the pituitary gland. Furthermore, both ACTH and α-MSH have been identified in MC granules. However, the role of α-MSH in the pathogenesis of melanoma is unclear. It was shown that α-MSH may act as an anti-inflammatory agent. On the other hand, it may concurrently prevent the recognition of melanoma by the immune system [93]. When it comes to NMSC, a study by Slominski et al. [94] showed that keratinocytes may be stimulated by ACTH and MSH and, as a consequence, facilitate the development of BCC.

Together with ACTH and MSH, corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) is another hormone produced by the pituitary gland that has also been localized inside MC secretory granules. Furthermore, high serum CRH concentration and CRH receptor presence were identified on MCs in a specimen obtained from a patient who underwent acute psychological stress with a subsequent exacerbation of CM (urticaria pigmentosa). Additionally, MCs were reported to secrete CRH and express CRH receptors, indicating the role of CRH in stress-related symptoms of mastocytosis [95]. Activation of CRH receptors on MCs may induce angiogenesis, thus facilitating the progression of the disease [96]. CRH receptors have been identified in melanoma cell lines but not in benign melanocytic nevi [97]. In a study performed by Yang et al. [98], CRH was found to be involved in the migration of melanoma cells in an animal model. Moreover, CRH was reported to inhibit human keratinocyte proliferation [99], thus pointing to it possibly not being involved in NMSC development.

4.3.3. Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Thyroid (HPT) Axis

Among an abundance of different molecules, mast cells can also synthesize and store the thyroid hormones triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) [100]. Homeostasis of thyroid hormones (THs) is conditioned in an autocrine fashion by the presence of deiodinases, which have the ability to activate and deactivate thyroid hormones. Deiodinases are dynamically expressed in a tissue-specific manner and are essential in skin development and maturation [101]. The impact of deiodinases on skin cancer has been most extensively studied in an animal model of BCC. For instance, type 3 deiodinase (THs inactivating enzyme) is overexpressed in BCC, thus resulting in local hypothyroidism leading to increased keratinocyte proliferation. Moreover, it was shown that type 3 deiodinase-knocked-down mice display a 5-fold reduction in the growth of BCC xenografts [102]. The effect of histamine on mast cell T3 concentration seems peculiar. Mast cell exposition to an attomolar (10−18) (but not higher) concentration of histamine results in elevated T3 content in mast cells, implying the existence of a hormonal network in the immune system [103]. Furthermore, TSH increases the mast cell concentration of T3 [104]. Despite T3 reducing SCC cell proliferation, it concurrently induces epithelial–mesenchymal transition, enhancing SCC invasiveness [105].

Apparently, the impact of THs also occurs via genomic action through the TSH receptor (TSHR). It has been shown that skin cells, namely keratinocytes, fibroblasts, and epidermal melanocytes, express the TSH receptor (TSHR). Ellerhorst et al. [106] demonstrated that the expression of TSHR is higher in malignant and premalignant melanocytic lesions and displayed that melanoma cells, but not normal melanocytes, are induced to proliferate at a physiologically relevant concentration of TSH. A study by Shah et al. [107] exhibited a higher prevalence of hypothyroidism among melanoma patients compared to the general population. Contrary to this, an animal model of hypothyroid-induced mice with uveal melanoma displayed significantly longer survival times compared to mice receiving thyroxine [108]. The link between mastocytosis, skin cancer, and the HPT axis seems to be even more evident considering that mast cells express and store TSH [100]. However, the complex and often incoherent data allow only the assumption that a reduced concentration of THs is protective, whereas an increased TSH level may promote the proliferation of melanoma cells.

4.3.4. Neuropeptides

Substance P (SP) is a neuroendocrine peptide that binds to the neurokinin 1 receptor (NK1-R). Binding of SP to NK1-R results in the activation of several signaling pathways that promote cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and apoptosis inhibition, which enhance neoplasm growth and metastasis. Skin lesions in patients with mastocytosis have significantly upregulated expression of NK1-R compared to healthy controls [109]. Interestingly, the presence of NK1-R has also been described in melanoma, dysplastic, and Spitz nevi cells, but not in acquired benign melanocytic nevi [110]. The serum concentration of SP is elevated in patients with mastocytosis compared to healthy controls [109]. Consequently, the promotion of malignant transformation of melanocytes and tumor progression may be facilitated in subjects with mastocytosis. It was also shown that the NK1-R antagonist is effective in inducing melanoma cell apoptosis in vitro, and therefore it may be a candidate for the treatment of melanoma [110]. Moreover, SP elicits pruritus, thus implying NK1-R antagonists as a promising therapy for itch in mastocytosis [111].

Another neuropeptide that has the ability to activate and is simultaneously found in MC granules is calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP). Although CGRP is mainly recognized for its potent vasodilatory properties, it also serves as an immunomodulatory agent in the skin and a regulator of keratinocyte growth [112]. CGRP attenuates Langerhans cell antigen presentation in the animal model, which may be the culprit for impaired anti-tumoral immune response [113]. Interestingly, intradermal injection of a CGRP antagonist was proven to avert this immunosuppressive effect of CGRP [114]. Additionally, CGRP was demonstrated to stimulate the proliferation of melanocytes and promote melanin production, which could potentially play a role in the observed basal hyperpigmentation in individuals with CM [115]. The impact of CGRP on melanoma is uncertain; CGRP was shown to inhibit melanogenesis and induce apoptosis in vitro [116]. However, CGRP augments the exhaustion of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, which in turn curtails their ability to eliminate melanoma [117]. CGRP was shown to promote oral SCC and other NMSC development and plays a key role in the augmentation of pain related to neoplasm progression [118]. Moreover, the potential involvement of CGRP in skin cancer in mastocytosis patients is even more apparent considering that its concentration is elevated in the sera of patients with mastocytosis [109].

Additionally, the role of sensory nerve endings has to be noted, as they may bind the relationship between mastocytosis and skin neoplasms. Sensory nerve stimulation (e.g., by injury or UVR) results in the secretion of CGRP and SP, which in turn results in MC activation and degranulation [119]. Moreover, nerve endings may directly enhance the release of histamine from the adjacent MCs. Together with SP, CGRP may act synergistically in releasing histamine, which has been shown to be involved in skin cancer development [120].

It transpires that ultraviolet radiation, an independent risk factor for skin cancer, may not only be responsible for MC activation [121], but may also act as a mediator in the crosstalk between mast cells and dermal cells via β-endorphin, another neuropeptide that may activate and be retrogradely secreted by MCs. In the animal model, UV exposure triggered the release of β-endorphin from keratinocytes, consequently acting as an indirect addictive agent for sun-seeking behaviors [122]. Given that MCs may release β-endorphin and be further activated by keratinocyte-derived β-endorphin after UV exposure, they may contribute to tanning dependence, thus enhancing the self-perpetuating process of UV-related increased risk of developing melanoma and NMSC.

4.4. Mastocytosis Treatment and the Risk of Skin Malignancy

According to one hypothesis, some therapeutic modalities used in the treatment of mastocytosis may influence the risk of malignancy. The main goal of mastocytosis treatment is to control the secretion of mediators or their effects [123]. Second-generation H1 antihistamines are crucial drugs in the anti-mediator therapy of all forms of mastocytosis [124].

It has been reported that drugs such as desloratadine and loratadine have been associated with improved melanoma survival and decreased risk of secondary melanoma in melanoma patients [69].

In contrast, both PUVA (psoralen ultraviolet A radiation) and UVB 311 (phototherapy with 311 nm wavelength ultraviolet B radiation), which can be used in mastocytosis to relieve skin symptoms like itching [34], are known to be risk factors for melanoma and NMSC [125,126,127].

Table 2 summarizes the treatment methods that are used in mastocytosis and their influence on the risk of NMSC and melanoma.

Table 2.

Data on treatment methods used in mastocytosis and the risk of melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer.

5. Screening and Management of Skin Cancer and Melanoma in Mastocytosis Patients

Despite the above-discussed increased risk of melanoma and NMSC in patients with mastocytosis, none of the current guidelines address the need for routine screening in this group of patients [1,25,28].

In daily practice, such screening includes mainly visual inspection and dermoscopic assessment. It has been shown that dermoscopy increases diagnostic sensitivity and specificity in melanoma diagnosis and allows for more precise detection of early melanoma compared to unaided eye examination [141].

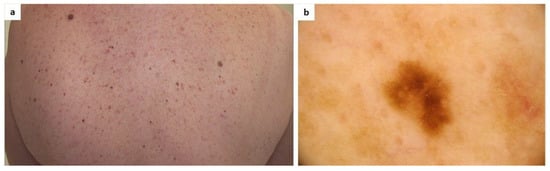

To date, there have been no published studies on the dermoscopic aspect of melanocytic nevi in mastocytosis patients. It is important to underline that maculopapular mastocytosis lesions and melanocytic nevi may both present with brown reticular lines (pigment network) [142] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

(a) A patient diagnosed with maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis (MCM) and multiple melanocytic nevi. Clinically, it may be difficult to differentiate some nevi from mastocytosis skin lesions; (b) Dermoscopy shows a melanocytic nevus surrounded by areas of a light-brown pigmented network typical of MCM (FotoFinder, Medicam 800 HD, ×20).

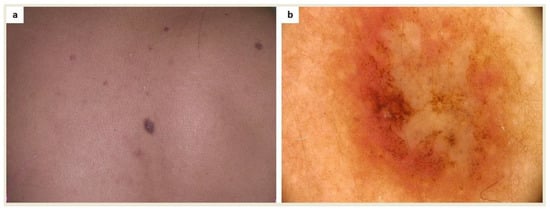

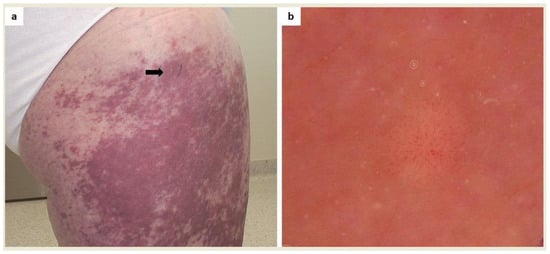

Patients who have a collision of melanocytic/non-melanocytic lesions with cutaneous mastocytosis lesions maybe more difficult to assess dermoscopically (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 2.

(a) A patient diagnosed with maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis (MCM) and multiple melanocytic nevi was referred for surgical excision due to an atypical skin lesion in the interscapular area; (b) Dermoscopy revealed asymmetry of color and structures as well as a polymorphic vascular pattern (FotoFinder, Medicam 800 HD, ×20). Based on histopathological evaluation, a collision of melanocytic compound nevus and mastocytoma was diagnosed.

Figure 3.

(a) A patient diagnosed with systemic mastocytosis with cutaneous involvement who had noticed an amelanotic nodule within coalescing mastocytosis skin lesions on the right thigh (arrow); (b) Dermoscopy showed a polymorphic vascular pattern (a non-specific sign of malignancy) which led to diagnostic excision (FotoFinder, Medicam 800 HD, ×20). Histopathological examination showed a cumulation of mastocytes.

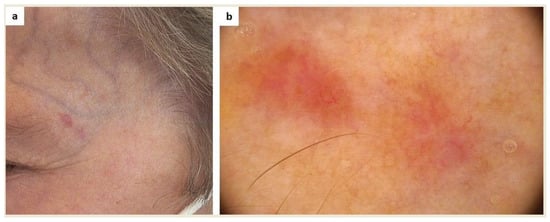

Finally, patients may misinterpret signs of cutaneous malignancy as mastocytosis skin involvement (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

(a) This amelanotic lesion in the left temporal area was noticed in a patient with systemic mastocytosis with cutaneous involvement during a routine dermoscopic examination. The patient considered it a sign of cutaneous mastocytosis. (b) Dermoscopy showed a polymorphic vascular pattern (a non-specific sign of malignancy), erosion, and white-pink and light-brown structureless areas (FotoFinder, Medicam 800 HD, ×20). Based on histopathological examination, a diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma was made.

As the basis of skin cancer treatment and melanoma is surgical excision, clinicians managing patients with mastocytosis should be familiar with perioperative risk in these patients in order to avoid complications, as it is known that patients with mastocytosis have a higher risk of perioperative anaphylaxis [143,144].

6. Discussion

Recent studies demonstrate that patients suffering from mastocytosis face an increased risk of melanoma and NMSC. The cause of this phenomenon has yet to be clearly identified.

The precise pathogenetic link explaining the increased risk of skin cancer in mastocytosis patients has not been elucidated. In the literature, the potential contribution of several factors has been suggested, including genetic background, cytokines, hormones, neuropeptides, and iatrogenic factors.

Though the role of KIT alternations has been established in mastocytosis and melanoma, mutations show heterogeneous distribution through the gene in both diseases. It is possible that KIT mutations can be indirectly associated with melanocyte proliferation (e.g., via MITF and SRC family kinases). Additionally, recent studies have shown an association between tumor-infiltrating MCs and resistance to anti-PD-1 therapy in melanoma.

It has been suggested that MCs may promote the development of cancer by releasing mediators conducive to tumor development, angiogenesis, tissue remodeling, and affecting the adaptive immune response. The interactions between MCs and neoplastic cells in the tumor microenvironment are complex. It has been shown that MCs may contribute to NMSC through their immunosuppressive effect on sun-exposed skin. On the other hand, neoplastic cells may produce cytokines that recruit MCs or induce changes in their phenotype. The immunosuppressive activity of MCs is connected, i.e., with IL-10, TNF-α, and histamine.

Sex hormones may make females prior to menopause more susceptible to melanoma and possibly imply a clinical course of mastocytosis. Unfortunately, large-scale epidemiological data regarding the sex of patients with melanoma and NMSC are unavailable.

Our understanding of the link between the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis and neuropeptides (substance P, calcitonin gene-related peptide, and β-endorphin) in skin cancer and mastocytosis is poor, and the matter requires further study. The roles of the hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid axis, mastocytosis, and skin neoplasms are complex and trilateral.

Among the treatment modalities used in mastocytosis patients are methods that may increase the risk of skin malignancy (i.e., systemic glucocorticosteroids, phototherapy), but which also possibly increase survival in melanoma (i.e., disodium cromoglycate, desloratadine, loratadine, and fexofenadine).

Data from population studies supports the need for active screening for skin neoplasia in patients with mastocytosis. In this context, cooperation between dermatologists, allergologists, and hematologists is crucial—regular medical visits associated with mastocytosis management should create an opportunity for total body skin examination and patient education concerning self-examination and the rules of photoprotection.

7. Conclusions

The existing literature data concerning the pathogenesis, diagnosis, management, and prognosis of melanoma and NMSC in patients with mastocytosis are scarce, and this topic requires further studies.

Data from population studies supports the need for active screening for skin neoplasia in patients with mastocytosis. In this context, cooperation between dermatologists, allergologists, and hematologists seems crucial—regular medical visits associated with mastocytosis management should create an opportunity for total body skin examination and patients’ education concerning self-examination and the rules of photoprotection. Possible treatment with phototherapy should be planned carefully, balancing the potential benefits and risks of this form of treatment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K. and M.S. (Martyna Sławińska); methodology, A.K. and M.S. (Martyna Sławińska) and J.Ż.; formal analysis, A.K. and M.S. (Martyna Sławińska) and J.Ż.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K. and M.S. (Martyna Sławińska) and J.Ż.; writing—review and editing, M.L. and M.S. (Michał Sobjanek) and R.J.N.; visualization, M.S. (Martyna Sławińska); supervision, M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Patients’ signed consent was obtained for publication of the pictures presented in the figures.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Valent, P.; Akin, C.; Sperr, W.R.; Horny, H.P.; Arock, M.; Metcalfe, D.D.; Galli, S.J. New Insights into the Pathogenesis of Mastocytosis: Emerging Concepts in Diagnosis and Therapy. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2023, 18, 361–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broesby-Olsen, S.; Farkas, D.K.; Vestergaard, H.; Hermann, A.P.; Moller, M.B.; Mortz, C.G.; Kristensen, T.K.; Bindslev-Jensen, C.; Sorensen, H.T.; Frederiksen, H. Risk of solid cancer, cardiovascular disease, anaphylaxis, osteoporosis and fractures in patients with systemic mastocytosis: A nationwide population-based study. Am. J. Hematol. 2016, 91, 1069–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagglund, H.; Sander, B.; Gulen, T.; Lindelof, B.; Nilsson, G. Increased risk of malignant melanoma in patients with systemic mastocytosis? Acta Dermatol. Venereol. 2014, 94, 583–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todd, P.; Garioch, J.; Seywright, M.; Rademaker, M.; Thomson, J. Malignant melanoma and systemic Mastocytosis—A possible association? Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 1991, 16, 455–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phung, B.; Kazi, J.U.; Lundby, A.; Bergsteinsdottir, K.; Sun, J.; Goding, C.R.; Jonsson, G.; Olsen, J.V.; Steingrimsson, E.; Ronnstrand, L. KIT(D816V) Induces SRC-Mediated Tyrosine Phosphorylation of MITF and Altered Transcription Program in Melanoma. Mol. Cancer Res. 2017, 15, 1265–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klump, J.; Phillipp, U.; Follo, M.; Eremin, A.; Lehmann, H.; Nestel, S.; von Bubnoff, N.; Nazarenko, I. Extracellular vesicles or free circulating DNA: Where to search for BRAF and cKIT mutations? Nanomedicine 2018, 14, 875–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribatti, D.; Tamma, R.; Annese, T.; Crivellato, E. The role of mast cells in human skin cancers. Clin. Exp. Med. 2021, 21, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedoszytko, B.; Arock, M.; Lyons, J.J.; Bachelot, G.; Schwartz, L.B.; Reiter, A.; Jawhar, M.; Schwaab, J.; Lange, M.; Greiner, G.; et al. Clinical Impact of Inherited and Acquired Genetic Variants in Mastocytosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valent, P.; Akin, C.; Hartmann, K.; Nilsson, G.; Reiter, A.; Hermine, O.; Sotlar, K.; Sperr, W.R.; Escribano, L.; George, T.I.; et al. Mast cells as a unique hematopoietic lineage and cell system: From Paul Ehrlich’s visions to precision medicine concepts. Theranostics 2020, 10, 10743–10768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribatti, D.; Vacca, A.; Ria, R.; Marzullo, A.; Nico, B.; Filotico, R.; Roncali, L.; Dammacco, F. Neovascularisation, expression of fibroblast growth factor-2, and mast cells with tryptase activity increase simultaneously with pathological progression in human malignant melanoma. Eur. J. Cancer 2003, 39, 666–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komi, D.E.A.; Redegeld, F.A. Role of Mast Cells in Shaping the Tumor Microenvironment. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2020, 58, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komulainen, J.; Siiskonen, H.; Harvima, I.T. Association of Elevated Serum Tryptase with Cutaneous Photodamage and Skin Cancers. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2021, 182, 1135–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atiakshin, D.; Kostin, A.; Buchwalow, I.; Samoilova, V.; Tiemann, M. Protease Profile of Tumor-Associated Mast Cells in Melanoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valent, P. KIT D816V and the cytokine storm in mastocytosis: Production and role of interleukin-6. Haematologica 2020, 105, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahri, R.; Kiss, O.; Prise, I.; Garcia-Rodriguez, K.M.; Atmoko, H.; Martinez-Gomez, J.M.; Levesque, M.P.; Dummer, R.; Smith, M.P.; Wellbrock, C.; et al. Human Melanoma-Associated Mast Cells Display a Distinct Transcriptional Signature Characterized by an Upregulation of the Complement Component 3 That Correlates With Poor Prognosis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 861545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallenfang, K.; Stadler, R. Association between UVA1 and PUVA bath therapy and development of malignant melanoma. Hautarzt 2001, 52, 705–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhari, N.; Schwaertz, R.A.; Apalla, Z.; Salerni, G.; Akay, B.N.; Patil, A.; Grabbe, S.; Goldust, M. Effect of estrogen in malignant melanoma. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 1905–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppicelli, S.; Ruzzolini, J.; Lulli, M.; Biagioni, A.; Bianchini, F.; Caldarella, A.; Nediani, C.; Andreucci, E.; Calorini, L. Extracellular Acidosis Differentially Regulates Estrogen Receptor beta-Dependent EMT Reprogramming in Female and Male Melanoma Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nettleship, E.; Tay, W. Rare Forms of Urticaria. Br. Med. J. 1869, 2, 323–324. [Google Scholar]

- Scherber, R.M.; Borate, U. How we diagnose and treat systemic mastocytosis in adults. Br. J. Haematol. 2018, 180, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezary, A.; Levy-Coblentz, G.; Chauvillon, P. Dermographisme et mastocytose. Bull. Soc. Fr. Dermatol. Syphiligr. 1936, 43, 359–361. [Google Scholar]

- Valent, P.; Akin, C.; Hartmann, K.; Alvarez-Twose, I.; Brockow, K.; Hermine, O.; Niedoszytko, M.; Schwaab, J.; Lyons, J.J.; Carter, M.C.; et al. Updated Diagnostic Criteria and Classification of Mast Cell Disorders: A Consensus Proposal. Hemasphere 2021, 5, e646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Systemic Mastocytosis. Orphanet Encyclopedia. Available online: https://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/OC_Exp.php?Lng=GB&Expert=2467 (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- Bista, A.; Uprety, D.; Vallatharasu, Y.; Arjyal, L.; Ghimire, S.; Giri, M.; Rosenstein, L. Systemic Mastocytosis in United States: A Population Based Study. Blood 2018, 132, 1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, K.; Escribano, L.; Grattan, C.; Brockow, K.; Carter, M.C.; Alvarez-Twose, I.; Matito, A.; Broesby-Olsen, S.; Siebenhaar, F.; Lange, M.; et al. Cutaneous manifestations in patients with mastocytosis: Consensus report of the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis; the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology; and the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 137, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, M.; Hartmann, K.; Carter, M.C.; Siebenhaar, F.; Alvarez-Twose, I.; Torrado, I.; Brockow, K.; Renke, J.; Irga-Jaworska, N.; Plata-Nazar, K.; et al. Molecular Background, Clinical Features and Management of Pediatric Mastocytosis: Status 2021. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valent, P.; Akin, C.; Metcalfe, D.D. Mastocytosis: 2016 updated WHO classification and novel emerging treatment concepts. Blood 2017, 129, 1420–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojvodic, A.; Vlaskovic-Jovicevic, T.; Vojvodic, P.; Vojvodic, J.; Goldust, M.; Peric-Hajzler, Z.; Matovic, D.; Sijan, G.; Stepic, N.; Wollina, U.; et al. Melanoma and Mastocytosis. Open. Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 7, 3050–3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donati, P.; Paolino, G.; Donati, M.; Panetta, C. Cutaneous mastocytosis combined with eruptive melanocytic nevi and melanoma. Coincidence or a linkage in the pathogenesis? J. Dermatol. Case Rep. 2014, 8, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruini, C.; Hartmann, D.; Flaig, M.J.; von Braunmuhl, T.; Berking, C. Aggressive malignant melanoma in a patient with urticaria pigmentosa. Hautarzt 2018, 69, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capo, A.; Goteri, G.; Mozzicafreddo, G.; Serresi, S.; Giacchetti, A. Melanoma and mastocytosis: Is really only a coincidence? Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2019, 44, 76–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdogan, N.; Elcin, G.; Gokoz, O. The co-existence of cutaneous melanoma and urticaria pigmentosa in a patient with Becker’s nevus. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2020, 19, 1268–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rydberg, A.; Lehman, J.; Markovic, S.; Anderson, K. Mastocytosis and melanoma: A case series. Int. J. Dermatol. 2022, 61, 603–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalzic, L.; Eickenscheidt, L.; Seidel, C.; Kribus, S.; Ziegler, H.; Komar, M. Telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans, a form of cutaneous mastocytosis, associated with malignant melanoma. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2009, 7, 360–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okun, M.R.; Bhawan, J. Combined melanocytoma-mastocytoma in a case of nodular mastocytosis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1979, 1, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arber, D.A.; Tamayo, R.; Weiss, L.M. Paraffin section detection of the c-kit gene product (CD117) in human tissues: Value in the diagnosis of mast cell disorders. Hum. Pathol. 1998, 29, 498–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennartsson, J.; Ronnstrand, L. Stem cell factor receptor/c-Kit: From basic science to clinical implications. Physiol. Rev. 2012, 92, 1619–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longley, B.J., Jr.; Metcalfe, D.D.; Tharp, M.; Wang, X.; Tyrrell, L.; Lu, S.Z.; Heitjan, D.; Ma, Y. Activating and dominant inactivating c-KIT catalytic domain mutations in distinct clinical forms of human mastocytosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 1609–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corless, C.L.; Fletcher, J.A.; Heinrich, M.C. Biology of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 3813–3825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemmer, K.; Corless, C.L.; Fletcher, J.A.; McGreevey, L.; Haley, A.; Griffith, D.; Cummings, O.W.; Wait, C.; Town, A.; Heinrich, M.C. KIT mutations are common in testicular seminomas. Am. J. Pathol. 2004, 164, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komi, D.E.A.; Rambasek, T.; Wohrl, S. Mastocytosis: From a Molecular Point of View. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2018, 54, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, D.D.M.; Guhan, S.; Tsao, H. KIT and Melanoma: Biological Insights and Clinical Implications. Yonsei Med. J. 2020, 61, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beadling, C.; Jacobson-Dunlop, E.; Hodi, F.S.; Le, C.; Warrick, A.; Patterson, J.; Town, A.; Harlow, A.; Cruz, F., 3rd; Azar, S.; et al. KIT gene mutations and copy number in melanoma subtypes. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 6821–6828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtin, J.A.; Busam, K.; Pinkel, D.; Bastian, B.C. Somatic activation of KIT in distinct subtypes of melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 4340–4346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, J.L.; Fridlyand, J.; Patel, H.; Jain, A.N.; Busam, K.; Kageshita, T.; Ono, T.; Albertson, D.G.; Pinkel, D.; Bastian, B.C. Determinants of BRAF mutations in primary melanomas. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2003, 95, 1878–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slipicevic, A.; Herlyn, M. KIT in melanoma: Many shades of gray. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2015, 135, 337–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Cabala, C.A.; Wang, W.L.; Trent, J.; Yang, D.; Chen, S.; Galbincea, J.; Kim, K.B.; Woodman, S.; Davies, M.; Plaza, J.A.; et al. Correlation between KIT expression and KIT mutation in melanoma: A study of 173 cases with emphasis on the acral-lentiginous/mucosal type. Mod. Pathol. 2009, 22, 1446–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consortium, A.P.G. AACR Project GENIE: Powering Precision Medicine through an International Consortium. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 818–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Armstrong, E.; Wei, A.Z.; Ye, F.; Lee, A.; Carlino, M.S.; Sullivan, R.J.; Carvajal, R.D.; Shoushtari, A.N.; Johnson, D.B. Clinical and genomic correlates of imatinib response in melanomas with KIT alterations. Br. J. Cancer 2022, 127, 1726–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somasundaram, R.; Connelly, T.; Choi, R.; Choi, H.; Samarkina, A.; Li, L.; Gregorio, E.; Chen, Y.; Thakur, R.; Abdel-Mohsen, M.; et al. Tumor-infiltrating mast cells are associated with resistance to anti-PD-1 therapy. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, D.; Tsuji, Y.; Setaluri, V. Selective down-regulation of tyrosinase family gene TYRP1 by inhibition of the activity of melanocyte transcription factor, MITF. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 3096–3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyduch, G.; Kaczmarczyk, K.; Okoń, K. Mast cells and cancer: Enemies or allies? Pol. J. Pathol. 2012, 63, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grimbaldeston, M.A.; Finlay-Jones, J.J.; Hart, P.H. Mast cells in photodamaged skin: What is their role in skin cancer? Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2006, 5, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erkilic, S.; Erbagci, Z. The significance of mast cells associated with basal cell carcinoma. J. Dermatol. 2001, 28, 312–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parizi, A.C.; Barbosa, R.L.; Parizi, J.L.; Nai, G.A. A comparison between the concentration of mast cells in squamous cell carcinomas of the skin and oral cavity. Bras. Dermatol. 2010, 85, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimbaldeston, M.A.; Pearce, A.L.; Robertson, B.O.; Coventry, B.J.; Marshman, G.; Finlay-Jones, J.J.; Hart, P.H. Association between melanoma and dermal mast cell prevalence in sun-unexposed skin. Br. J. Dermatol. 2004, 150, 895–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimbaldeston, M.A.; Skov, L.; Finlay-Jones, J.J.; Hart, P.H. Increased dermal mast cell prevalence and susceptibility to development of basal cell carcinoma in humans. Methods 2002, 28, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gudiseva, S.; Santosh, A.B.R.; Chitturi, R.; Anumula, V.; Poosarla, C.; Baddam, V.R.R. The role of mast cells in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Contemp. Oncol. 2017, 21, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedoszytko, B.; Lange, M.; Sokolowska-Wojdylo, M.; Renke, J.; Trzonkowski, P.; Sobjanek, M.; Szczerkowska-Dobosz, A.; Niedoszytko, M.; Gorska, A.; Romantowski, J.; et al. The role of regulatory T cells and genes involved in their differentiation in pathogenesis of selected inflammatory and neoplastic skin diseases. Part II: The Treg role in skin diseases pathogenesis. Postep. Dermatol. Alergol. 2017, 34, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedoszytko, B.; Lange, M.; Sokolowska-Wojdylo, M.; Renke, J.; Trzonkowski, P.; Sobjanek, M.; Szczerkowska-Dobosz, A.; Niedoszytko, M.; Gorska, A.; Romantowski, J.; et al. The role of regulatory T cells and genes involved in their differentiation in pathogenesis of selected inflammatory and neoplastic skin diseases. Part I: Treg properties and functions. Postep. Dermatol. Alergol. 2017, 34, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedoszytko, B.; Sokolowska-Wojdylo, M.; Renke, J.; Lange, M.; Trzonkowski, P.; Sobjanek, M.; Szczerkowska-Dobosz, A.; Niedoszytko, M.; Gorska, A.; Romantowski, J.; et al. The role of regulatory T cells and genes involved in their differentiation in pathogenesis of selected inflammatory and neoplastic skin diseases. Part III: Polymorphisms of genes involved in Tregs’ activation and function. Postep. Dermatol. Alergol. 2017, 34, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slawinska, M.; Zablotna, M.; Glen, J.; Lakomy, J.; Nowicki, R.J.; Sobjanek, M. STAT3 polymorphisms and IL-6 polymorphism are associated with the risk of basal cell carcinoma in patients from northern Poland. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2019, 311, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, P.H.; Grimbaldeston, M.A.; Finlay-Jones, J.J. Sunlight, immunosuppression and skin cancer: Role of histamine and mast cells. Clin. Exp. Pharm. Physiol. 2001, 28, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoki, M.; Pawankar, R.; Niimi, Y.; Kawana, S. Mast cells in basal cell carcinoma express VEGF, IL-8 and RANTES. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2003, 130, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solimando, A.G.; Desantis, V.; Ribatti, D. Mast Cells and Interleukins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugurel, S.; Schadendorf, D.; Horny, K.; Sucker, A.; Schramm, S.; Utikal, J.; Pfohler, C.; Herbst, R.; Schilling, B.; Blank, C.; et al. Elevated baseline serum PD-1 or PD-L1 predicts poor outcome of PD-1 inhibition therapy in metastatic melanoma. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Peng, G.; Zhu, K.; Jie, X.; Xu, Y.; Rao, X.; Xu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xing, B.; Wu, G.; et al. PD-1(+) mast cell enhanced by PD-1 blocking therapy associated with resistance to immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2023, 72, 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.L.; Cho, J. Pathophysiological Roles of Histamine Receptors in Cancer Progression: Implications and Perspectives as Potential Molecular Targets. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, I.; Wagner, P.; Bottai, M.; Eriksson, H.; Ingvar, C.; Krakowski, I.; Nielsen, K.; Olsson, H. Desloratadine and loratadine use associated with improved melanoma survival. Allergy 2020, 75, 2096–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammendola, M.; Leporini, C.; Marech, I.; Gadaleta, C.D.; Scognamillo, G.; Sacco, R.; Sammarco, G.; De Sarro, G.; Russo, E.; Ranieri, G. Targeting mast cells tryptase in tumor microenvironment: A potential antiangiogenetic strategy. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 154702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, R.J.; Meng, H.; Marchese, M.J.; Ren, S.; Schwartz, L.B.; Tonnesen, M.G.; Gruber, B.L. Human mast cells stimulate vascular tube formation. Tryptase is a novel, potent angiogenic factor. J. Clin. Investig. 1997, 99, 2691–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Conti, P. Mast cells: The Jekyll and Hyde of tumor growth. Trends Immunol. 2004, 25, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gambichler, T.; Skrygan, M.; Hyun, J.; Bechara, F.; Tomi, N.S.; Altmeyer, P.; Kreuter, A. Cytokine mRNA expression in basal cell carcinoma. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2006, 298, 139–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruns, S.B.; Hartmann, K. Clinical outcomes of pregnant women with mastocytosis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2003, 111, S323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciach, K.; Niedoszytko, M.; Abacjew-Chmylko, A.; Pabin, I.; Adamski, P.; Leszczynska, K.; Preis, K.; Olszewska, H.; Wydra, D.G.; Hansdorfer-Korzon, R. Pregnancy and Delivery in Patients with Mastocytosis Treated at the Polish Center of the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis (ECNM). PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worobec, A.S.; Akin, C.; Scott, L.M.; Metcalfe, D.D. Mastocytosis complicating pregnancy. Obs. Gynecol. 2000, 95, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matito, A.; Alvarez-Twose, I.; Morgado, J.M.; Sanchez-Munoz, L.; Orfao, A.; Escribano, L. Clinical impact of pregnancy in mastocytosis: A study of the Spanish Network on Mastocytosis (REMA) in 45 cases. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2011, 156, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitsu, M.; Narita, S.; Lambert, K.C.; Grady, J.J.; Estes, D.M.; Curran, E.M.; Brooks, E.G.; Watson, C.S.; Goldblum, R.M.; Midoro-Horiuti, T. Estradiol activates mast cells via a non-genomic estrogen receptor-alpha and calcium influx. Mol. Immunol. 2007, 44, 1977–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmaz, C.; Yuksel, H.; Mete, N.; Bayrak, P.; Baytur, Y.B. Is the menstrual cycle affecting the skin prick test reactivity? Asian Pac. J. Allergy Immunol. 2004, 22, 197–203. [Google Scholar]

- Vasiadi, M.; Kempuraj, D.; Boucher, W.; Kalogeromitros, D.; Theoharides, T.C. Progesterone inhibits mast cell secretion. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharm. 2006, 19, 787–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zierau, O.; Zenclussen, A.C.; Jensen, F. Role of female sex hormones, estradiol and progesterone, in mast cell behavior. Front. Immunol. 2012, 3, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, G.; Akatsuka, K.; Nakashima, Y.; Yokoe, Y.; Higo, N.; Shimonaka, M. Tamoxifen inhibits the proliferation of non-melanoma skin cancer cells by increasing intracellular calcium concentration. Int. J. Oncol. 2018, 53, 2157–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, M.P.C.; Santos, A.E.; Custodio, J.B.A. Rethinking tamoxifen in the management of melanoma: New answers for an old question. Eur. J. Pharm. 2015, 764, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butterfield, J.H.; Chen, D. Response of patients with indolent systemic mastocytosis to tamoxifen citrate. Leuk. Res. 2016, 40, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hicks, B.M.; Kristensen, K.B.; Pedersen, S.A.; Holmich, L.R.; Pottegard, A. Hormone replacement therapy and the risk of melanoma in post-menopausal women. Hum. Reprod. 2019, 34, 2418–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahoon, E.K.; Kitahara, C.M.; Ntowe, E.; Bowen, E.M.; Doody, M.M.; Alexander, B.H.; Lee, T.; Little, M.P.; Linet, M.S.; Freedman, D.M. Female Estrogen-Related Factors and Incidence of Basal Cell Carcinoma in a Nationwide US Cohort. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 4058–4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch-Johansen, F.; Jensen, A.; Olesen, A.B.; Christensen, J.; Tjonneland, A.; Kjaer, S.K. Does hormone replacement therapy and use of oral contraceptives increase the risk of non-melanoma skin cancer? Cancer Causes Control. 2012, 23, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, M.J. The biological actions of estrogens on skin. Exp. Dermatol. 2002, 11, 487–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stensheim, H.; Cvancarova, M.; Moller, B.; Fossa, S.D. Pregnancy after adolescent and adult cancer: A population-based matched cohort study. Int. J. Cancer 2011, 129, 1225–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermans, M.A.W.; van Daele, P.L.A.; Damman, J.; van Doorn, M.B.A.; Pasmans, S.G.M.A. The prevalence of malignant melanoma in adults with mastocytosis and adnexal skin tumours: A case-control study. Ann. Cancer Epidemiol. 2022, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECIS—European Cancer Information System. Available online: https://ecis.jrc.ec.europa.eu (accessed on 19 March 2023).

- Antoniewicz, J.; Nedoszytko, B.; Lange, M.; Wierzbicka, J.; Gorska-Ponikowska, M.; Niedoszytko, M.; Zablotna, M.; Nowicki, R.J.; Zmijewski, M.A. Modulation of dermal equivalent of hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis in mastocytosis. Postep. Dermatol. Alergol. 2021, 38, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheau, C.; Draghici, C.; Ilie, M.A.; Lupu, M.; Solomon, I.; Tampa, M.; Georgescu, S.R.; Caruntu, A.; Constantin, C.; Neagu, M.; et al. Neuroendocrine Factors in Melanoma Pathogenesis. Cancers 2021, 13, 2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slominski, A.; Heasley, D.; Mazurkiewicz, J.E.; Ermak, G.; Baker, J.; Carlson, J.A. Expression of proopiomelanocortin (POMC)-derived melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH) and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) peptides in skin of basal cell carcinoma patients. Hum. Pathol. 1999, 30, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theoharides, T.C. The impact of psychological stress on mast cells. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020, 125, 388–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, J.; Papadopoulou, N.; Kempuraj, D.; Boucher, W.S.; Sugimoto, K.; Cetrulo, C.L.; Theoharides, T.C. Human mast cells express corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) receptors and CRH leads to selective secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor. J. Immunol. 2005, 174, 7665–7675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funasaka, Y.; Sato, H.; Chakraborty, A.K.; Ohashi, A.; Chrousos, G.P.; Ichihashi, M. Expression of proopiomelanocortin, corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), and CRH receptor in melanoma cells, nevus cells, and normal human melanocytes. J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 1999, 4, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Park, H.; Yang, Y.; Kim, T.S.; Bang, S.I.; Cho, D. Enhancement of cell migration by corticotropin-releasing hormone through ERK1/2 pathway in murine melanoma cell line, B16F10. Exp. Dermatol. 2007, 16, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slominski, A.; Zbytek, B.; Pisarchik, A.; Slominski, R.M.; Zmijewski, M.A.; Wortsman, J. CRH functions as a growth factor/cytokine in the skin. J. Cell. Physiol. 2006, 206, 780–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landucci, E.; Laurino, A.; Cinci, L.; Gencarelli, M.; Raimondi, L. Thyroid Hormone, Thyroid Hormone Metabolites and Mast Cells: A Less Explored Issue. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancino, G.; Sibilio, A.; Luongo, C.; Di Cicco, E.; Miro, C.; Cicatiello, A.G.; Nappi, A.; Sagliocchi, S.; Ambrosio, R.; De Stefano, M.A.; et al. The Thyroid Hormone Inactivator Enzyme, Type 3 Deiodinase, Is Essential for Coordination of Keratinocyte Growth and Differentiation. Thyroid 2020, 30, 1066–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dentice, M.; Luongo, C.; Huang, S.; Ambrosio, R.; Elefante, A.; Mirebeau-Prunier, D.; Zavacki, A.M.; Fenzi, G.; Grachtchouk, M.; Hutchin, M.; et al. Sonic hedgehog-induced type 3 deiodinase blocks thyroid hormone action enhancing proliferation of normal and malignant keratinocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 14466–14471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csaba, G.; Pallinger, E. Is there a possibility of intrasystem regulation by hormones produced by the immune cells? Experiments with extremely low concentrations of histamine. Acta Physiol. Hung. 2009, 96, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csaba, G.; Pallinger, E. Thyrotropic hormone (TSH) regulation of triiodothyronine (T(3)) concentration in immune cells. Inflamm. Res. 2009, 58, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miro, C.; Di Cicco, E.; Ambrosio, R.; Mancino, G.; Di Girolamo, D.; Cicatiello, A.G.; Sagliocchi, S.; Nappi, A.; De Stefano, M.A.; Luongo, C.; et al. Thyroid hormone induces progression and invasiveness of squamous cell carcinomas by promoting a ZEB-1/E-cadherin switch. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellerhorst, J.A.; Sendi-Naderi, A.; Johnson, M.K.; Cooke, C.P.; Dang, S.M.; Diwan, A.H. Human melanoma cells express functional receptors for thyroid-stimulating hormone. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2006, 13, 1269–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, M.; Orengo, I.F.; Rosen, T. High prevalence of hypothyroidism in male patients with cutaneous melanoma. Dermatol. Online J. 2006, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabian, I.D.; Rosner, M.; Fabian, I.; Vishnevskia-Dai, V.; Zloto, O.; Shinderman Maman, E.; Cohen, K.; Ellis, M.; Lin, H.Y.; Hercbergs, A.; et al. Low thyroid hormone levels improve survival in murine model for ocular melanoma. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 11038–11046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maintz, L.; Wardelmann, E.; Walgenbach, K.; Fimmers, R.; Bieber, T.; Raap, U.; Novak, N. Neuropeptide blood levels correlate with mast cell load in patients with mastocytosis. Allergy 2011, 66, 862–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, M.; Rosso, M.; Robles-Frias, M.J.; Salinas-Martin, M.V.; Rosso, R.; Gonzalez-Ortega, A.; Covenas, R. The NK-1 receptor is expressed in human melanoma and is involved in the antitumor action of the NK-1 receptor antagonist aprepitant on melanoma cell lines. Lab. Investig. 2010, 90, 1259–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowska, D.; Reich, A. Role of Mast Cells in the Pathogenesis of Pruritus in Mastocytosis. Acta Dermatol. Venereol. 2021, 101, adv00583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggenkamp, D.; Kopnick, S.; Stab, F.; Wenck, H.; Schmelz, M.; Neufang, G. Epidermal nerve fibers modulate keratinocyte growth via neuropeptide signaling in an innervated skin model. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2013, 133, 1620–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosoi, J.; Murphy, G.F.; Egan, C.L.; Lerner, E.A.; Grabbe, S.; Asahina, A.; Granstein, R.D. Regulation of Langerhans cell function by nerves containing calcitonin gene-related peptide. Nature 1993, 363, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niizeki, H.; Alard, P.; Streilein, J.W. Calcitonin gene-related peptide is necessary for ultraviolet B-impaired induction of contact hypersensitivity. J. Immunol. 1997, 159, 5183–5186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akiyama, M. A clinical and histological study of urticaria pigmentosa: Relationships between mast cell proliferation and the clinical and histological manifestations. J. Dermatol. 1990, 17, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Feng, J.Y.; Wang, Q.; Shang, J. Calcitonin gene-related peptide cooperates with substance P to inhibit melanogenesis and induces apoptosis of B16F10 cells. Cytokine 2015, 74, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balood, M.; Ahmadi, M.; Eichwald, T.; Ahmadi, A.; Majdoubi, A.; Roversi, K.; Roversi, K.; Lucido, C.T.; Restaino, A.C.; Huang, S.; et al. Nociceptor neurons affect cancer immunosurveillance. Nature 2022, 611, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Lin, C.; Wang, X.; Ji, T. Calcitonin gene-related peptide: A promising bridge between cancer development and cancer-associated pain in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol. Lett. 2020, 20, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seiffert, K.; Granstein, R.D. Neuropeptides and neuroendocrine hormones in ultraviolet radiation-induced immunosuppression. Methods 2002, 28, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasola, M.P.; Taquez Delgado, M.A.; Nicoud, M.B.; Medina, V.A. Histamine in cancer immunology and immunotherapy. Current status and new perspectives. Pharm. Res. Perspect. 2021, 9, e00778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C. Neuroendocrinology of mast cells: Challenges and controversies. Exp. Dermatol. 2017, 26, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fell, G.L.; Robinson, K.C.; Mao, J.; Woolf, C.J.; Fisher, D.E. Skin beta-endorphin mediates addiction to UV light. Cell 2014, 157, 1527–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannetti, M.P. Treatment of systemic mastocytosis: Novel and emerging therapies. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021, 127, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siebenhaar, F.; Akin, C.; Bindslev-Jensen, C.; Maurer, M.; Broesby-Olsen, S. Treatment strategies in mastocytosis. Immunol. Allergy Clin. N. Am. 2014, 34, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archier, E.; Devaux, S.; Castela, E.; Gallini, A.; Aubin, F.; Le Maitre, M.; Aractingi, S.; Bachelez, H.; Cribier, B.; Joly, P.; et al. Carcinogenic risks of psoralen UV-A therapy and narrowband UV-B therapy in chronic plaque psoriasis: A systematic literature review. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2012, 26 (Suppl. S3), 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, R.S.; Study, P.F.u. The risk of melanoma in association with long-term exposure to PUVA. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2001, 44, 755–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vella Briffa, D.; Eady, R.A.; James, M.P.; Gatti, S.; Bleehen, S.S. Photochemotherapy (PUVA) in the treatment of urticaria pigmentosa. Br. J. Dermatol. 1983, 109, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimpean, A.M.; Raica, M. The Hidden Side of Disodium Cromolyn: From Mast Cell Stabilizer to an Angiogenic Factor and Antitumor Agent. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. 2016, 64, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homicsko, K.; Richtig, G.; Tuchmann, F.; Tsourti, Z.; Hanahan, D.; Coukos, G.; Wind-Rotolo, M.; Richtig, E.; Zygoura, P.; Holler, C.; et al. Proton pump inhibitors negatively impact survival of PD-1 inhibitor based therapies in metastatic melanoma patients. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, x40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berge, L.A.M.; Andreassen, B.K.; Stenehjem, J.S.; Heir, T.; Karlstad, O.; Juzeniene, A.; Ghiasvand, R.; Larsen, I.K.; Green, A.C.; Veierod, M.B.; et al. Use of Immunomodulating Drugs and Risk of Cutaneous Melanoma: A Nationwide Nested Case-Control Study. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020, 12, 1389–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagas, M.R.; Cushing, G.L., Jr.; Greenberg, E.R.; Mott, L.A.; Spencer, S.K.; Nierenberg, D.W. Non-melanoma skin cancers and glucocorticoid therapy. Br. J. Cancer 2001, 85, 683–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, H.T.; Mellemkjaer, L.; Nielsen, G.L.; Baron, J.A.; Olsen, J.H.; Karagas, M.R. Skin cancers and non-hodgkin lymphoma among users of systemic glucocorticoids: A population-based cohort study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2004, 96, 709–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raone, B.; Patrizi, A.; Gurioli, C.; Gazzola, A.; Ravaioli, G.M. Cutaneous carcinogenic risk evaluation in 375 patients treated with narrowband-UVB phototherapy: A 15-year experience from our Institute. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2018, 34, 302–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, R.S.; Study, P.F.-U. The risk of squamous cell and basal cell cancer associated with psoralen and ultraviolet A therapy: A 30-year prospective study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2012, 66, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebrun-Frenay, C.; Berestjuk, I.; Cohen, M.; Tartare-Deckert, S. Effects on Melanoma Cell Lines Suggest No Significant Risk of Melanoma Under Cladribine Treatment. Neurol. Ther. 2020, 9, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Trolio, R.; Simeone, E.; Di Lorenzo, G.; Buonerba, C.; Ascierto, P.A. The use of interferon in melanoma patients: A systematic review. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev. 2015, 26, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Mao, L.; Chi, Z.; Sheng, X.; Cui, C.; Kong, Y.; Dai, J.; Wang, X.; Li, S.; Tang, B.; et al. Efficacy Evaluation of Imatinib for the Treatment of Melanoma: Evidence From a Retrospective Study. Oncol. Res. 2019, 27, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliano, A.; Dobson, J. Prospective clinical trial of masitinib mesylate treatment for advanced stage III and IV canine malignant melanoma. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2020, 61, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millward, M.J.; House, C.; Bowtell, D.; Webster, L.; Olver, I.N.; Gore, M.; Copeman, M.; Lynch, K.; Yap, A.; Wang, Y.; et al. The multikinase inhibitor midostaurin (PKC412A) lacks activity in metastatic melanoma: A phase IIA clinical and biologic study. Br. J. Cancer 2006, 95, 829–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragnarsson-Olding, B.; Djureen-Martensson, E.; Mansson-Brahme, E.; Hansson, J. Loco-regional control of cutaneous metastases of malignant melanoma by treatment with miltefosine (Miltex). Acta Oncol. 2005, 44, 773–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinnes, J.; Deeks, J.J.; Chuchu, N.; Ferrante di Ruffano, L.; Matin, R.N.; Thomson, D.R.; Wong, K.Y.; Aldridge, R.B.; Abbott, R.; Fawzy, M.; et al. Dermoscopy, with and without visual inspection, for diagnosing melanoma in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 12, CD011902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slawinska, M.; Kaszuba, A.; Lange, M.; Nowicki, R.J.; Sobjanek, M.; Errichetti, E. Dermoscopic Features of Different Forms of Cutaneous Mastocytosis: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocca-Tjeertes, I.F.A.; van de Ven, A.; Koppelman, G.H.; Sprikkelman, A.B.; Oude Elberink, H. Medical algorithm: Peri-operative management of mastocytosis patients. Allergy 2021, 76, 3233–3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kacar, M.; Rijavec, M.; Selb, J.; Korosec, P. Clonal mast cell disorders and hereditary alpha-tryptasemia as risk factors for anaphylaxis. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2023, 53, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).