Abstract

Collection and interpretation of “touch DNA” from crime scenes represent crucial steps during criminal investigations, with clear consequences in courtrooms. Although the main aspects of this type of evidence have been extensively studied, some controversial issues remain. For instance, there is no conclusive evidence indicating which sampling method results in the highest rate of biological material recovery. Thus, this study aimed to describe the actual considerations on touch DNA and to compare three different sampling procedures, which were “single-swab”, “double-swab”, and “other methods” (i.e., cutting out, adhesive tape, FTA® paper scraping), based on the experimental results published in the recent literature. The data analysis performed shows the higher efficiency of the single-swab method in DNA recovery in a wide variety of experimental settings. On the contrary, the double-swab technique and other methods do not seem to improve recovery rates. Despite the apparent discrepancy with previous research, these results underline certain limitations inherent to the sampling procedures investigated. The application of this information to forensic investigations and laboratories could improve operative standard procedures and enhance this almost fundamental investigative tool’s probative value.

1. Introduction

When approaching a crime scene, given the limited availability of biological evidence, it is essential to choose the best forensic approach to collect DNA evidence in order to achieve as much information as possible. Among many possibilities, recovering DNA from different biological materials left behind by criminals and matching them to suspects has become increasingly relevant, giving an effective tool to investigators and courts. Moreover, in recent years, scientific improvements in recovery, extraction, amplification, and analysis led to obtaining informative profiles even from extremely limited traces [1,2,3,4,5,6]. In this scenario, the capacity to interpret DNA deposited through handling items (“touch DNA”) becomes a necessary tool in most forensic genetic laboratories, even if some challenges remain.

“Touch DNA” can be defined as DNA transferred from a person to an object via contact with the object itself. In the literature, this form of evidence has also been called “contact DNA”, “trace DNA”, or “transfer DNA”. The nature of this type of genetic material is still the subject of ongoing scientific debate, which expresses the lack of knowledge in the present forensic field. While many studies support DNA deposited by touch came from shed keratinocytes [7,8], several papers offer a wider perspective, identifying multiple sources as complete or partial skin cells, nucleated epithelial cells from other fluids or body parts in contact with one’s hands (i.e., saliva, sebum, sweat), or cell-free DNA, either endogenous or transferred onto the contact region from the abovementioned fluids [9,10]. In particular, cell-free DNA has been proven to be a reliable source of genetic material, often generating higher yields than its cellular counterpart [11] although considerable doubt remains about its origin; it is still unclear whether cell-free DNA is derived directly from body fluids or whether it is released after cellular degradation following touch deposition. Reports of fragmented DNA traces deposited from freshly washed hands suggest that DNA alteration begins within the organism [12].

However, touch DNA samples are generally known to contain low levels of DNA [13] and the presence of degraded genetic material, regardless of its origin, makes genotype detection challenging [14,15,16,17,18,19,20].

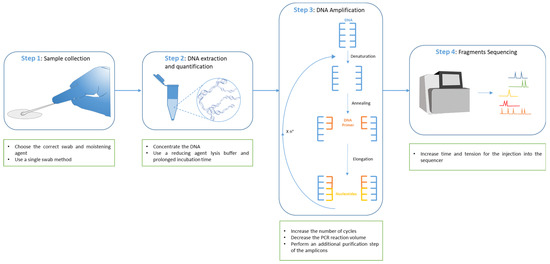

Degraded DNA is not the only component of touch deposits that can compromise forensic profiling. The presence of small amounts of genetic material available, sometimes even below the minimum thresholds of modern highly sensitive commercial STR kits, is another phenomenon commonly found in contact samples. In this contingency, PCR amplification can miss the detection of short DNA fragments even when the procedure is implemented with additional cycles to maximize the results. These evident limitations suggest the occurrence of stochastic effects related to sampling techniques rather than mere analytical defects [21,22] and precisely describe the so-called Low Template DNA (LT-DNA) or Low Copy Number DNA (LCN-DNA). In Figure 1 we describe methods used to enhance LT-DNA extraction, amplification, and sequencing.

Figure 1.

DNA analysis workflow and improvement for low template DNA. In sample collection, the correct swab should be chosen, and, in particular, collection through a single swab should be performed on non-porous surfaces; the use of tape lifting is a preferred option for porous surfaces. Moreover, in this step, the moistening agent is also of fundamental importance to improve the final results (Step 1). Other possible solutions to improve the DNA analysis of low template DNA consist of the concentration of the DNA after its extraction or in the use of reducing agent lysis buffer with a prolonged time of incubation to increase, in both cases, the concentration of the final extracted DNA in the reaction volume (Step 2). The following step of DNA amplification may be modified in different ways to improve the DNA analysis in the case of low-template DNA. It is possible to increase the number of PCR cycles, decrease the PCR reaction volume to further concentrate the amount of DNA, or perform an additional purification step of the amplicons (Step 3). Eventually, it is possible to also intervene in the last step of fragments sequencing by increasing the time and the tension for the injection of the DNA fragments into the sequencer (Step 4).

Many factors can affect the quantity and the success of recovering the genetic material, schematically grouped into three categories of variables influencing sample generation, deposition, and analysis.

The concept of good or bad shedder status, primarily introduced in 1999 [23], is a person’s propensity to deposit a high or low amount of DNA on a touched object, respectively. According to the current notions, this ability varies greatly between individuals or in the same person under distinct conditions [24]. Although biological and genetic factors affecting this status are largely unknown, age, sex, and certain activities (i.e., touching DNA-free objects, wearing gloves, rubbing fingers on body parts) seem to influence the deposited traces. Generally, men shed more DNA than women, especially younger males compared to older ones (the trend was not investigated in females) and washing hands can reduce the available quantity [25,26]. In contrast, physical activities involving sweating leads to an increase in DNA transfer [27]. Closely related to this subject, body location impact results too, for example, sebaceous skin areas (vs. non-sebaceous), the dominant hand (vs. non-dominant), and fingertips (vs. palms) potentially facilitate DNA deposits [28].

Biological evidence can be virtually left behind everywhere during criminal activities, i.e., from wooden murder weapons to metallic handle doors. Considering this, in daily forensic practice, different material compositions had to be investigated, with variable results. Several authors have reported increased sloughed epithelial cells on rough and porous substrates, while non-porous substrates adhere to genetic material less readily [9,29]. Thus, fabrics and cotton appear to be better DNA collectors than plastic or glass surfaces and it has been proven more difficult to consistently recover touch DNA from metal surfaces [30]. The manner and duration of contact also influence the amount of genetic material transferred. It has been demonstrated that DNA deposits increase when pressure or friction are involved [28], directly proportional to the intensity applied [31]. Instead, the influence of time in the resulting amount of DNA on handling/wearing items remains controversial. While recent studies propose a linear correlation between variables [32], previous papers excluded any linkage, suggesting the origin of traces in a single transfer step upon initial contact [33]. Additionally, the possible interactions between other investigative methods, such as dactyloscopic enhancement methods, bloodstain enhancement methods, and DNA typing techniques, cannot be excluded [34,35,36].

Since each operative step expresses great availability in devices and techniques as well as in the manner of recovering, processing, and analysing samples, results from DNA analysis may be influenced by the combination between the singular forensic approach to the crime scene and following laboratory procedures [37,38]. Considered from a methodological perspective, the collection of touch DNA traces may involve the use of various sampling devices, such as swabs, adhesive tapes, or directly examining the evidence, in whole or in part. Considering their cost-effectiveness and minimal training requirements, the use of swabs is one of the most versatile and widely used methods. They can be applied dry or moistened with several agents and in varied materials. For example, standard cotton swabs are traditionally preferred for the collection of biological fluids and, notwithstanding further research, showed a tendency for the organic residue to get entrapped within cotton fibres, reducing sample availability [39,40]. When trace DNA is expected to be recovered, the double-swab technique [38,41] can be implemented. It consists of a wet swab and a second dry one sequentially applied onto the surface of interest, aimed at maximising recovery. Although the efficiency of this method has not been fully discussed, it is usually exploited to improve the collection of cellular material [42]. When other procedures are employed, effective alternatives are represented by “cutting out” the sampling area of soft tissues or the adhesive tape lifting the solid surface. The last sampling method is quick and straightforward, and tapes with better adhesion have been reported to produce a higher yield of trace DNA than swabbing, although the stickiness, rigidity, and size of the tape make the interpretation of the results more difficult [43,44,45,46].

Laboratory methods employed also affect the success of touch DNA analysis. Once recovered, standard workflows for processing touch DNA evidence first of all involves DNA extraction, for which a multitude of approaches exists, and then DNA quantification is conducted [47], which is critical to determine the quantity and quality of DNA extracted. This process is fundamental to decide the downstream genotyping methods to use and the proportion of the initial amount of evidence to submit to possible destructive analysis, thus, achieving a more informed interpretation of further analytical results [48]. However, the DNA extraction and quantification processes both result in the loss of a portion of the original sample and increase the probability of introducing exogenous DNA [49]. The amplification phase frequently implies the use of one of the commercially available kits most commonly used for criminal cases [50,51].

As can be inferred from the above, numerous factors influence touch DNA’s effectiveness as a forensic tool. Thus, we present here a brief review regarding the current state of knowledge on touch DNA analysis, with a particular focus on the impact the sampling techniques have on the results. The present paper evaluates several experimental settings in which different sampling methods have been used to provide valuable guidance in selecting the most appropriate collecting technique in relation to operative conditions. We believe it is necessary to enhance each analytical phase of the investigation in order to maximise the chance of finding useful profiles at crime scenes.

2. Materials and Methods

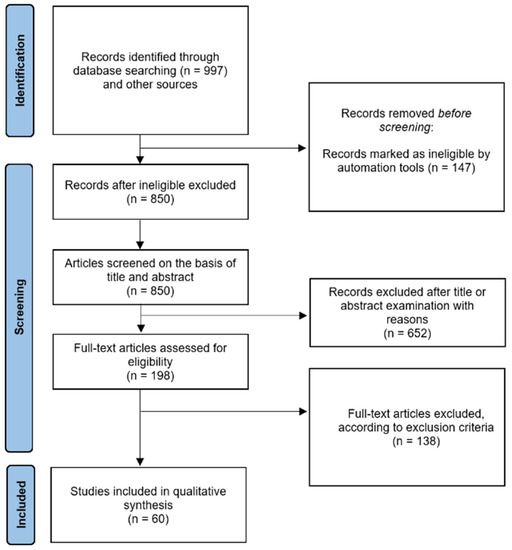

This review was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systemic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Guidelines [52].

In December 2021, a systematic literature review was performed by selecting papers from the Pubmed Database, according to the query “touch DNA”. The search terms were intentionally kept generic to include the highest number of potentially interesting works. A total of 997 articles were identified. Different inclusion criteria were then applied using specific PubMed filters to start the screening process: (1) English or Italian language; (2) availability of abstract and full text. Duplicates were manually removed. The screening process was conducted by the selection of titles and abstracts, and, when necessary, the evaluation of the full text. In cases of doubt, the consensus opinions of the research supervisors were solicited.

After title and abstract evaluation, a total of 136 manuscripts were considered. In the last phase, articles were selected when results were expressed in the form of STR alleles number (Group 1), informative profiles (Group 2), and percentage or DNA quantities (Group 3) to allow the comparison even between different experimental settings. Eventually, a total of 60 studies were carefully chosen.

The PRISMA flow chart in Figure 2 summarises the study screening and selection process as described above.

Figure 2.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systemic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 flow diagram. A total of 60 studies were included in our systematic review.

3. Results

3.1. STR Alleles and Informative Profiles

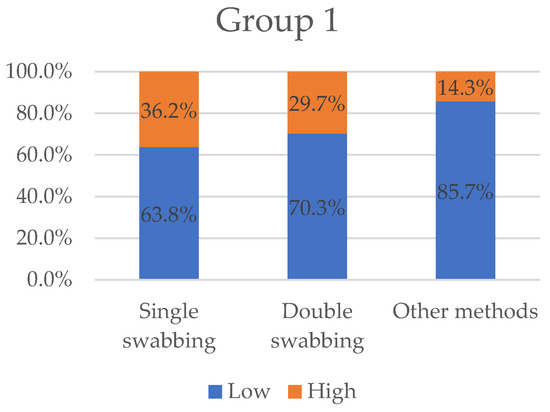

Based on the assumption that each article is composed of several separate tests, the experimental settings were highlighted (i.e., the number of samples collected, the recovery method, the extraction process, and the amplification procedure) to help distinguish the individual trials. Then, each trial’s results, represented by the mean number of STR alleles obtained, was converted into a percentage, compared to the specific amplification kit used, and classified as “low” or “high” if it was less than or greater than 66%, respectively. Similarly, the mean percentage of informative profiles was categorized as “low” or “high” with the same distinctive values.

We eventually individuated 9 articles (15% of the total) in which the results were expressed as STR alleles obtained (papers shown in Table 1). Figure 3 displays the variables “low” and “high” grouped by three types of sampling methods (single-swabbing, double-swabbing, and other methods).

Table 1.

Papers categorized in Group 1. Features displayed are authors and publication year, number (n°) of samples collected, sampling methods implemented, important findings, and remarks highlighted.

Figure 3.

Variables “low” and “high” grouped by sampling methods for Group 1. With 36.2%, single-swabbing obtains the greatest “high” value, followed by double-swabbing (29.7%), and other methods (14.3%).

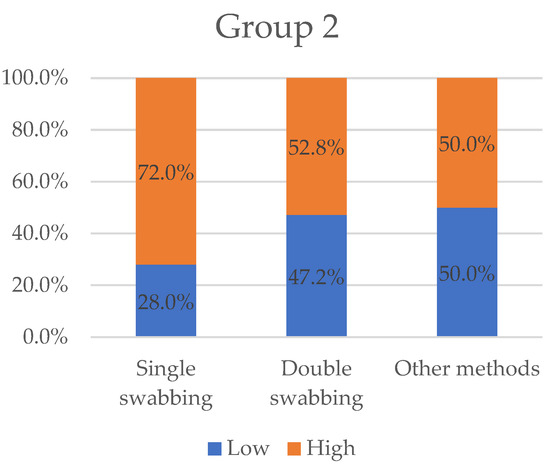

Likewise, 14 papers (23.4%) selected stated their results in the form of informative profiles (articles in Table 2). In Figure 4, we categorised the variables “low” and “high”, in percentage by the same previous sampling method type (single-swabbing, double-swabbing, and others).

Table 2.

Papers categorized in Group 2. Features displayed are authors and publication year, number (n°) of samples collected, sampling methods implemented, important findings, and remarks highlighted.

Figure 4.

Variables “low” and “high” grouped by sampling methods for Group 2. Other methods collected the worst “high” value with 50%. Double-swabbing and single swabbing obtained 52.8% and 72%, respectively.

3.2. DNA Quantitation

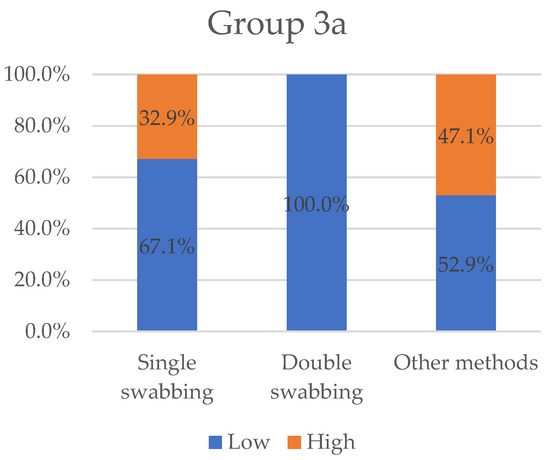

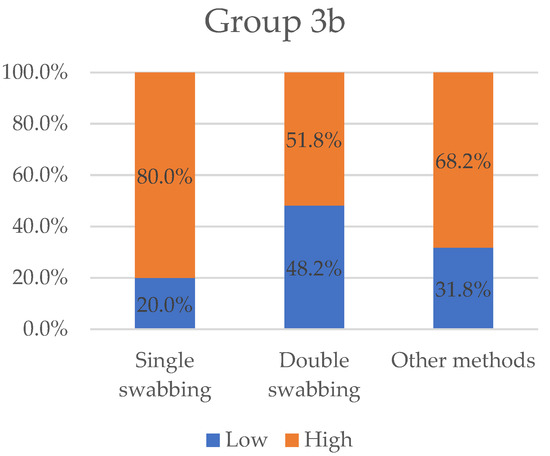

The last group of papers consisted of 43 articles where the authors published their results as DNA quantities, which represents 66.7% of the total. To be able to compare different findings, we identified two sub-groups: experiments where DNA concentration (Group 3a, with 17 articles) was declared, and trials where DNA quantity was indicated in absolute value (Group 3b, with 26 articles). Table 3 and Table 4 report the selection of the respective papers.

Table 3.

Papers categorized in Group 3a. Features displayed are authors and publication year, number (n°) of samples collected, sampling methods implemented, important findings, and remarks highlighted. N.A. not assigned.

Table 4.

Papers categorized in Group 3b. Features displayed are authors and publication year, number (n°) of samples collected, sampling methods implemented, important findings, and remarks highlighted. N.A. not assigned.

As for previous result types, we set cut-offs to classify the efficacy of different sampling methods. When the mean DNA concentration reported was under or above 0.1 ng/uL, a “low” or “high” value was assigned, respectively; the same variables were attributed when mean DNA quantity resulted in less than or greater than 1 ng. Figure 5 and Figure 6 show the values, in percentage, grouped by sampling methods (single-swabbing, double-swabbing, and other methods).

Figure 5.

Variables “low” and “high” grouped by sampling methods for Group 3a. “Low” value represents the totality of results collected for double-swabbing. Single-swabbing and other methods obtained 67.1% and 52.9%, respectively.

Figure 6.

Variables “low” and “high” grouped by sampling methods for Group 3b. Single-swabbing appears to be the most efficient technique, with a “high” value equal to 80%. Other methods and double-swabbing collected 68.2% and 51.8%, respectively.

4. Discussion

The collection and analysis of touch DNA, especially when low amounts of genetic material are expected, can be challenging yet extremely precious for investigations. Touch DNA testing is limited by the difficulty of obtaining not only sufficient quality DNA to generate a complete profile, but also sufficient material to allow re-testing. Hence, optimising the procedures is fundamental even to improving the STR typing success rate. Moreover, studies investigating touch DNA often implement wide variability among experimental settings, with few papers examining the topic transversally. This analysis was designed to operate a literature review on touch DNA, with a focus on the comparison between the efficacy of different sampling methods. Since there is significant variability in the way results are presented and on what kind of data the comparison of touch DNA scenarios is based, we evaluate the performance of three collecting technique categories (single-swabbing vs. double-swabbing vs. other methods) by analysing the mean number of STR alleles, the percentages of informative profiles, and the quantity of touch DNA obtained. This variability in results can partially be explained by the fact that there is currently no consensus regarding which aspects of analysis are most suitable for comparing DNA traces [28]. DNA quantities seem ineffective, from an investigative standpoint, as they do not correlate with profile quality and do not contain any information about the presence of more than one contributor. However, they can provide an insight into the efficacy of procedures, the aim of the present study, and assist in the interpretation of research findings [102]. On the other hand, some experimental studies evaluate outcomes by analysing profile compositions. This sub-group was also considered to provide a broader perspective on the topic.

4.1. Single-Swabbing

In general, swabbing appears to be the most common procedure used, with other methods being applied depending on the setting. A large majority of the trials (72.6%) were conducted using a swabbing technique, as compared to only 27.4% of experiments that applied alternative approaches. From the examination of the results, single-swabbing emerges as an effective sampling technique, with the greatest percentage of “high” efficiency in Group 1 (36.2%), Group 2 (72%), and Group 3b (80%). In Group 3a (32.9%), however, its effectiveness appears as the second-best value. A possible explanation for the current considerations could be its extreme versatility. Swabs vary in several ways, such as the material from which they are made, their thickness and length, how tightly they are wound and/or articulated with the swab shaft, the shape and design of the storage/transport tubes, and the inclusion of or not of features that help to preserve the DNA, such as vents for improved air-drying, desiccants, or antimicrobial chemicals [103]. To maximise the chance of obtaining an informative DNA profile, swabs can be moistened with fluids such as sterile water and laboratory or commercial detergents [104]. Thus, crime scene officers have the possibility to adapt the most efficient combination, both regarding the substrate from which the sample is being collected and the type of biological material.

4.2. Double-Swabbing

Scrubbing an area with multiple swabs (and the co-extraction of these tools) has been promoted to enhance the overall recovery of trace DNA. It has now become a common practice, since some evidence stated a single moist cotton swab picks up less than half of the available sample [105]. In the present work, we found a controversial performance of the technique, as it did not achieve the best result in any of the groups considered. All the experiments in Group 3a produced a low value of DNA traces. Given the limitations of the present statistical analysis, it seems to be in direct contradiction to previous works showing that this procedure is recommended and improves the quality of the resulting DNA profiles [38,41,103]. Actually, De Bruin et al. [106], in comparing the double-swab method versus stubbing (an adapted tape-lifting technique) for collecting offender epithelial material, underline its slightly better performance despite not being as easy a procedure. Moreover, Vickar et al. [107] found that M-Vac® (Microbial Vacuum), an industrial device initially developed to sample food for potential pathogens, was better performing than double-swabbing for touch DNA collection on brick surfaces, even if it collected less DNA on non-porous tiles. As it is evident, the double-swab method does have limitations, particularly when used on certain substrates that can be found at crime scenes. According to this, the present considerations cannot exclude the possible influence of the adequacy with which the sampling procedure has been implemented in each trial. Under non-optimal experimental conditions, the double-swab technique not only yields less DNA than alternative methods, but it also damages the surface of items [44]. The success rate of obtaining a DNA profile from contact traces is largely dependent upon the selection of the appropriate recovery method for biological material and how it is applied.

4.3. Other Methods

In this last group, several procedures have been proposed in the literature. Overall, this category results in the most effective tests in Group 3a (47.1%) and the second-best in Group 2 (50%) and Group 3b (68.2%). In Group 1, this category collects the worst rate, with “low” efficacy (85.7%). The most frequently used sampling method examined in the present group is the so-called tapelifting, which consists in repeatedly pressing the adhesive part of a strip against the material surface of interest. Many other studies have already investigated its efficiency. Barash et al. [108] found that the tape collection of biological material simplifies sampling, is non-destructive, and is also highly effective in genotyping DNA from many previously untested items left at crime scenes. Another work evaluates nine collection methods in sampling touch DNA from human skin following skin-to-skin contact in mock assault scenarios [53]. The results express that the different tools did not have a distinct impact on the STR recovery even if adhesive tape seemed to be the least adequate for this purpose as it achieved the lowest DNA collection. Surprisingly, FTA paper scraping was employed in several experiments, while just a few papers exist in the forensic literature. It employs a novel approach based on Whatman FTA cards® that was used to collect touch DNA from the steering wheel surface in one case study [109]. Based on Kirgiz et al.’s work [56], FTA paper scraping seemed to yield significantly more DNA when compared to double-swabbing and tapelifting. The authors also provide some possible explanations for these concerns. In particular, FTA paper chemical composition allows greater preservation and release of DNA, a larger sampling area than swabs and a slower drying process. The “cutting out” technique is another procedure engaged in the considered articles. Despite some critical constraints, such as the material on which it is implemented (not every surface can be cut out) and its irreversibility, it has been reported to achieve the best results in DNA recovery in comparison with adhesive tape and dry swabbing [42]. Despite the limitations of a global consideration, these alternative collection procedures seem to be available in limited experimental groups, as evidenced by the low number of trials. These restrictions may also account for the unsatisfactory outcomes of the present paper regarding the efficacy of the treatment. It is likely that challenging scenarios requiring unconventional approaches may produce low-quality DNA samples because of the intrinsic complexity rather than the ineffectiveness of the recovery methods.

From our perspective, single-swabbing appears as an effective first-level technique, due to its versatility, cost-effectiveness, and ease of use. Virtually, this tool can be applied to every type of solid surface, with different biological matrices and high efficiency, as our study suggests. In the case of a limited number of evident traces, this collecting method may be preceded by visualisation techniques or by moistening the device to enhance the recovery success. When operative settings are particularly challenging, i.e., insufficient availability of samples or dryness of specimen, double-swabbing may be implemented as a second-level technique. However, the surface material needs to be carefully chosen, as the procedure has shown low efficacy when applied to porous patterns. Lastly, alternative methods represent dynamic forensic tools that may be used as third-level procedures in certain circumstances. In particular, the use of tapelifting is limited by a subsequently more complex extraction process and low performance on the human skin surface. FTA paper scraper seems to be a promising collecting method, which undoubtedly requires further investigations into its recovery rate on different materials. When touch DNA samples need to be recovered from soft tissue with great availability of evidence, direct cutting appears as a valid solution, even compared to traditional swabbing.

In conclusion, evident limitations underline our review, which are intrinsically related to the difficulty of the subject matter. Firstly, as a complete and systematic review requires, we consider an extensive temporal range to collect a significant number of experiments. Nonetheless, the number of articles taken into consideration may still be insufficient. Unfortunately, results from older studies must be treated with caution when compared to more recent publications. This is because the sensitivity of detecting traces of DNA has increased appreciably in recent years, potentially adulterating the final reflections. Secondly, besides sample collection, DNA profiling success is dependent on extraction technique, quantification method, and amplification procedures. These considerations are certainly complicated by inter-laboratory and inter-individual differences regarding profile assessment and internal standard practices. Since it is not feasible to consider every contribution, we assume each trial has been conducted according to the most appropriate, yet internationally validated, available procedures. There is no doubt that further analysis of touch DNA variables influencing outcomes will contribute to shedding light on a still-controversial topic.

5. Conclusions

The collection of useful touch DNA evidence cannot prescind the selection of an appropriate sampling method. While the current scientific opinion on the topic remains questioned, this review contributes to the debate by offering an updated perspective on the actual state of the art. While single-swabbing appears more efficient than alternative methods, double-swabbing does not improve touch DNA collections in advance. Less common sampling procedures such as FTA paper scraping, cutting out or adhesive tape-lifting require pre-operative considerations to maximise their unquestioned efficacy. The present paper also highlights some intrinsic limitations, such as the inevitable impact of numerous variables on outcomes. Among these, the site on which biological material sampling is conducted and the type of traces recovered result as the most significant. Different settings require different devices to obtain the highest profiles from touch DNA samples. This information, along with future considerations, will contribute to enhancing the forensic ability to produce interpretable DNA profiles during investigations, even when minimal biological traces are available, with potential benefits to the criminal justice process.

According to the studies examined in this review, it is nowadays possible to obtain satisfactory results from the analysis of LCN-DNA, depending on the recovery technique used. However, almost all articles revealed that further research is needed on the impact of using different methodologies to collect samples to determine the most effective collection method. More comprehensive knowledge of detecting a profile based on the type of object and its history, identifying the most appropriate area(s) to target for DNA sampling, and the impact of additional factors, such as duration, frequency, and manner of contact, is required. Additionally, further research regarding the mechanisms of DNA shedding status, including the differences between sexes, the effects of activities performed before deposition, as well as other factors that may affect the amount of DNA deposited, is highly desirable for the forensic discipline. Being able to know, harmonise, and improve these aspects would definitely strengthen the value of DNA evidence in courtrooms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.C.; methodology, P.T. and E.M.; investigation, E.M.; data curation, E.M.; writing—original draft, E.M.; writing—review and editing, P.T., B.M., L.C. and A.D.; resources, B.M.; formal Analysis, A.D. and E.M.; supervision, L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript. All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organisation or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bonsu, D.O.M.; Higgins, D.; Austin, J.J. Forensic Touch DNA Recovery from Metal Surfaces—A Review. Sci. Justice 2020, 60, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Travers, A.; Muskhelishvili, G. DNA Structure and Function. FEBS J. 2015, 282, 2279–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, A.; Civitello, A.; Hammond, H.A.; Caskey, C.T. DNA Typing and Genetic Mapping with Trimeric and Tetrameric Tandem Repeats. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1991, 49, 746–756. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gill, P.; Brinkmann, B.; d’Aloja, E.; Andersen, J.; Bar, W.; Carracedo, A.; Dupuy, B.; Eriksen, B.; Jangblad, M.; Johnsson, V.; et al. Considerations from the European DNA Profiling Group (EDNAP) Concerning STR Nomenclature. Forensic Sci. Int. 1997, 87, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimpton, C.P.; Gill, P.; Walton, A.; Urquhart, A.; Millican, E.S.; Adams, M. Automated DNA Profiling Employing Multiplex Amplification of Short Tandem Repeat Loci. Genome Res. 1993, 3, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäger, R. New Perspectives for Whole Genome Amplification in Forensic STR Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegand, P.; Kleiber, M. DNA Typing of Epithelial Cells after Strangulation. Int. J. Leg. Med. 1997, 110, 181–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comte, J.; Baechler, S.; Gervaix, J.; Lock, E.; Milon, M.-P.; Delémont, O.; Castella, V. Touch DNA Collection—Performance of Four Different Swabs. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2019, 43, 102113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrill, J.; Daniel, B.; Frascione, N. A Review of Trace “Touch DNA” Deposits: Variability Factors and an Exploration of Cellular Composition. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2019, 39, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinones, I.; Daniel, B. Cell Free DNA as a Component of Forensic Evidence Recovered from Touched Surfaces. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2012, 6, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.; Philpott, M.K.; Olsen, A.; Tootham, M.; Yadavalli, V.K.; Ehrhardt, C.J. Technical Note: Survey of Extracellular and Cell-Pellet-Associated DNA from ‘Touch’/Trace Samples. Forensic Sci. Int. 2021, 318, 110557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oleiwi, A.A.; Morris, M.R.; Schmerer, W.M.; Sutton, R. The Relative DNA-Shedding Propensity of the Palm and Finger Surfaces. Sci. Justice 2015, 55, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickenheiser, R.A. Trace DNA: A Review, Discussion of Theory, and Application of the Transfer of Trace Quantities of DNA through Skin Contact. J. Forensic Sci. 2002, 47, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrill, J.; Daniel, B.; Frascione, N. Technical Note: Lysis and Purification Methods for Increased Recovery of Degraded DNA from Touch Deposit Swabs. Forensic Sci. Int. 2022, 330, 111102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gettings, K.B.; Kiesler, K.M.; Vallone, P.M. Performance of a next Generation Sequencing SNP Assay on Degraded DNA. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2015, 19, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nimbkar, P.H.; Bhatt, V.D. A Review on Touch DNA Collection, Extraction, Amplification, Analysis and Determination of Phenotype. Forensic Sci. Int. 2022, 336, 111352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diegoli, T.M.; Farr, M.; Cromartie, C.; Coble, M.D.; Bille, T.W. An Optimized Protocol for Forensic Application of the PreCRTM Repair Mix to Multiplex STR Amplification of UV-Damaged DNA. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2012, 6, 498–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsman-Hall, K.M.; Orihuela, Y.; Karczynski, S.L.; Davis, A.L.; Ban, J.D.; Greenspoon, S.A. Development of STR Profiles from Firearms and Fired Cartridge Cases. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2009, 3, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.M.; Power, D.; Kanokwongnuwut, P.; Linacre, A. Ancestry and Phenotype Predictions from Touch DNA Using Massively Parallel Sequencing. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2021, 135, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, N.; Carlberg, K.; Sensabaugh, G.; Erlich, H.; Calloway, C. Target Capture Enrichment of Nuclear SNP Markers for Massively Parallel Sequencing of Degraded and Mixed Samples. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2018, 34, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timken, M.D.; Klein, S.B.; Buoncristiani, M.R. Stochastic Sampling Effects in STR Typing: Implications for Analysis and Interpretation. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2014, 11, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, P.; Buckleton, J. A Universal Strategy to Interpret DNA Profiles That Does Not Require a Definition of Low-Copy-Number. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2010, 4, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladd, C.; Adamowicz, M.S.; Bourke, M.T.; Scherczinger, C.A.; Lee, H.C. A Systematic Analysis of Secondary DNA Transfer. J. Forensic Sci. 1999, 44, 1270–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansson, L.; Swensson, M.; Gifvars, E.; Hedell, R.; Forsberg, C.; Ansell, R.; Hedman, J. Individual Shedder Status and the Origin of Touch DNA. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2022, 56, 102626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanokwongnuwut, P.; Martin, B.; Kirkbride, K.P.; Linacre, A. Shedding Light on Shedders. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2018, 36, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, L.Y.C.; Aw, Z.Q.; Chew, M.H.; Ishak, N.I.B.; Lee, Y.S.; Mugni, M.A.; Syn, C.K.C. Shedder Status: Does It Really Exist? Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. Suppl. Ser. 2019, 7, 360–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berge, M.; Ozcanhan, G.; Zijlstra, S.; Lindenbergh, A.; Sijen, T. Prevalence of Human Cell Material: DNA and RNA Profiling of Public and Private Objects and after Activity Scenarios. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2016, 21, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosch, A.; Courts, C. On DNA Transfer: The Lack and Difficulty of Systematic Research and How to Do It Better. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2019, 40, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, D.J.; Murphy, C.; McDermott, S.D. The Transfer of Touch DNA from Hands to Glass, Fabric and Wood. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2012, 6, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, I.; Park, S.; Tooke, J.; Smith, O.; Morgan, R.M.; Meakin, G.E. Efficiencies of Recovery and Extraction of Trace DNA from Non-Porous Surfaces. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. Suppl. Ser. 2017, 6, e153–e155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobias, S.H.A.; Jacques, G.S.; Morgan, R.M.; Meakin, G.E. The Effect of Pressure on DNA Deposition by Touch. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. Suppl. Ser. 2017, 6, e12–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldoni, F.; Castella, V.; Hall, D. Shedding Light on the Relative DNA Contribution of Two Persons Handling the Same Object. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2016, 24, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balogh, M.K.; Burger, J.; Bender, K.; Schneider, P.M.; Alt, K.W. STR Genotyping and MtDNA Sequencing of Latent Fingerprint on Paper. Forensic Sci. Int. 2003, 137, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tozzo, P.; Giuliodori, A.; Rodriguez, D.; Caenazzo, L. Effect of Dactyloscopic Powders on DNA Profiling from Enhanced Fingerprints: Results from an Experimental Study. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2014, 35, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Hoofstat, D.E.; Deforce, D.L.; Hubert De Pauw, I.P.; Van den Eeckhout, E.G. DNA Typing of Fingerprints Using Capillary Electrophoresis: Effect of Dactyloscopic Powders. Electrophoresis 1999, 20, 2870–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Manna, A.; Montpetit, S. A Novel Approach to Obtaining Reliable PCR Results from Luminol Treated Bloodstains. J. Forensic Sci. 2000, 45, 886–890. [Google Scholar]

- Goray, M.; Kokshoorn, B.; Steensma, K.; Szkuta, B.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. DNA Detection of a Temporary and Original User of an Office Space. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2020, 44, 102203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, B.C.M.; Cheung, B.K.K. Double Swab Technique for Collecting Touched Evidence. Leg. Med. Tokyo Jpn. 2007, 9, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benschop, C.C.G.; Wiebosch, D.C.; Kloosterman, A.D.; Sijen, T. Post-Coital Vaginal Sampling with Nylon Flocked Swabs Improves DNA Typing. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2010, 4, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colussi, A.; Viegas, M.; Beltramo, J.; Lojo, M. Efficiency of DNA IQ System® in Recovering Semen DNA from Cotton Swabs. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. Suppl. Ser. 2009, 2, 87–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, D.; Lorente, M.; Lorente, J.A.; Valenzuela, A.; Villanueva, E. An Improved Method to Recover Saliva from Human Skin: The Double Swab Technique. J. Forensic Sci. 1997, 42, 320–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sessa, F.; Salerno, M.; Bertozzi, G.; Messina, G.; Ricci, P.; Ledda, C.; Rapisarda, V.; Cantatore, S.; Turillazzi, E.; Pomara, C. Touch DNA: Impact of Handling Time on Touch Deposit and Evaluation of Different Recovery Techniques: An Experimental Study. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsberg, C.; Jansson, L.; Ansell, R.; Hedman, J. High-Throughput DNA Extraction of Forensic Adhesive Tapes. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2016, 24, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plaza, D.T.; Mealy, J.L.; Lane, J.N.; Parsons, M.N.; Bathrick, A.S.; Slack, D.P. Nondestructive Biological Evidence Collection with Alternative Swabs and Adhesive Lifters. J. Forensic Sci. 2016, 61, 485–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdon, T.J.; Mitchell, R.J.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. Evaluation of Tapelifting as a Collection Method for Touch DNA. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2014, 8, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, O.; Finnebraaten, M.; Heitmann, I.K.; Ramse, M.; Bouzga, M. Trace DNA Collection—Performance of Minitape and Three Different Swabs. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. Suppl. Ser. 2009, 2, 189–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, A.D.; Hytinen, M.E.; McClain, A.M.; Miller, M.T.; Dawson Cruz, T. An Optimized DNA Analysis Workflow for the Sampling, Extraction, and Concentration of DNA Obtained from Archived Latent Fingerprints. J. Forensic Sci. 2018, 63, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.B.; McCord, B.; Buel, E. Advances in Forensic DNA Quantification: A Review. Electrophoresis 2014, 35, 3044–3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanaugh, S.E.; Bathrick, A.S. Direct PCR Amplification of Forensic Touch and Other Challenging DNA Samples: A Review. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2018, 32, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J.M. The Future of Forensic DNA Analysis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2015, 370, 20140252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwawuba Stanley, U.; Mohammed Khadija, A.; Bukola, A.T.; Omusi Precious, I.; Ayevbuomwan Davidson, E. Forensic DNA Profiling: Autosomal Short Tandem Repeat as a Prominent Marker in Crime Investigation. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 27, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kallupurackal, V.; Kummer, S.; Voegeli, P.; Kratzer, A.; Dørum, G.; Haas, C.; Hess, S. Sampling Touch DNA from Human Skin Following Skin-to-Skin Contact in Mock Assault Scenarios-A Comparison of Nine Collection Methods. J. Forensic Sci. 2021, 66, 1889–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meixner, E.; Kallupurackal, V.; Kratzer, A.; Voegeli, P.; Thali, M.J.; Bolliger, S.A. Persistence and Detection of Touch DNA and Blood Stain DNA on Pig Skin Exposed to Water. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2020, 16, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hefetz, I.; Einot, N.; Faerman, M.; Horowitz, M.; Almog, J. Touch DNA: The Effect of the Deposition Pressure on the Quality of Latent Fingermarks and STR Profiles. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2019, 38, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirgiz, I.A.; Calloway, C. Increased Recovery of Touch DNA Evidence Using FTA Paper Compared to Conventional Collection Methods. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2017, 47, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonkrongjun, P.; Phetpeng, S.; Asawutmangkul, W.; Sotthibandhu, S.; Kitpipit, T.; Thanakiatkrai, P. Improved STR Profiles from Improvised Explosive Device (IED): Fluorescence Latent DNA Detection and Direct PCR. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2019, 41, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanakiatkrai, P.; Rerkamnuaychoke, B. Direct STR Typing from Fired and Unfired Bullet Casings. Forensic Sci. Int. 2019, 301, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baechler, S. Study of Criteria Influencing the Success Rate of DNA Swabs in Operational Conditions: A Contribution to an Evidence-Based Approach to Crime Scene Investigation and Triage. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2016, 20, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwender, M.; Bamberg, M.; Dierig, L.; Kunz, S.N.; Wiegand, P. The Diversity of Shedder Tests and a Novel Factor That Affects DNA Transfer. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2021, 135, 1267–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanokwongnuwut, P.; Martin, B.; Taylor, D.; Kirkbride, K.P.; Linacre, A. How Many Cells Are Required for Successful DNA Profiling? Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2021, 51, 102453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Snan, N.R. The Recovery of Touch DNA from RDX-C4 Evidences. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2021, 135, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Francisco, D.O.; Lopez, L.F.; de Gonçalves, F.T.; Fridman, C. Casework Direct Kit as an Alternative Extraction Method to Enhance Touch DNA Samples Analysis. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2020, 47, 102307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, B.; Blackie, R.; Taylor, D.; Linacre, A. DNA Profiles Generated from a Range of Touched Sample Types. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2018, 36, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanokwongnuwut, P.; Kirkbride, K.P.; Kobus, H.; Linacre, A. Enhancement of Fingermarks and Visualizing DNA. Forensic Sci. Int. 2019, 300, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falkena, K.; Hoveling, R.J.M.; van Weert, A.; Lambrechts, S.A.G.; van Leeuwen, T.G.; Aalders, M.C.G.; van Dam, A. Prediction of DNA Concentration in Fingermarks Using Autofluorescence Properties. Forensic Sci. Int. 2019, 295, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sołtyszewski, I.; Szeremeta, M.; Skawrońska, M.; Niemcunowicz-Janica, A.; Pepiński, W. Typeability of DNA in Touch Traces Deposited on Paper and Optical Data Discs. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 24, 437–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templeton, J.E.L.; Linacre, A. DNA Profiles from Fingermarks. BioTechniques 2014, 57, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, C.G.; Mangiaracina, R.; Donato, L.; D’Angelo, R.; Scimone, C.; Sidoti, A. Aged Fingerprints for DNA Profile: First Report of Successful Typing. Forensic Sci. Int. 2019, 302, 109905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ip, S.C.Y.; Lin, S.-W.; Lai, K.-M. An Evaluation of the Performance of Five Extraction Methods: Chelex® 100, QIAamp® DNA Blood Mini Kit, QIAamp® DNA Investigator Kit, QIAsymphony® DNA Investigator® Kit and DNA IQTM. Sci. Justice J. Forensic Sci. Soc. 2015, 55, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subhani, Z.; Daniel, B.; Frascione, N. DNA Profiles from Fingerprint Lifts-Enhancing the Evidential Value of Fingermarks Through Successful DNA Typing. J. Forensic Sci. 2019, 64, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phipps, M.; Petricevic, S. The Tendency of Individuals to Transfer DNA to Handled Items. Forensic Sci. Int. 2007, 168, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Templeton, J.E.L.; Taylor, D.; Handt, O.; Linacre, A. Typing DNA Profiles from Previously Enhanced Fingerprints Using Direct PCR. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2017, 29, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, L.; Forsberg, C.; Akel, Y.; Dufva, C.; Ansell, C.; Ansell, R.; Hedman, J. Factors Affecting DNA Recovery from Cartridge Cases. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2020, 48, 102343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasker, E.; LaRue, B.; Beherec, C.; Gangitano, D.; Hughes-Stamm, S. Analysis of DNA from Post-Blast Pipe Bomb Fragments for Identification and Determination of Ancestry. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2017, 28, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsons, L.; Sharfe, G.; Vintiner, S. DNA Analysis and Document Examination: The Impact of Each Technique on Respective Analyses. J. Forensic Sci. 2016, 61, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobe, S.S.; Govan, J.; Welch, L.A. Recovery of Human DNA Profiles from Poached Deer Remains: A Feasibility Study. Sci. Justice J. Forensic Sci. Soc. 2011, 51, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewell, J.; Quinones, I.; Ames, C.; Multaney, B.; Curtis, S.; Seeboruth, H.; Moore, S.; Daniel, B. Recovery of DNA and Fingerprints from Touched Documents. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2008, 2, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostojic, L.; Klempner, S.A.; Patel, R.A.; Mitchell, A.A.; Axler-DiPerte, G.L.; Wurmbach, E. Qualitative and Quantitative Assessment of Single Fingerprints in Forensic DNA Analysis. Electrophoresis 2014, 35, 3165–3172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldoni, F.; Castella, V.; Hall, D. Application of DIP-STRs to Sexual/Physical Assault Investigations: Eight Case Reports. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2017, 30, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yudianto, A.; Nuraini, M.I.; Furqoni, A.H.; Nzilibili, S.M.M.; Harjanto, P. The Use of Touch DNA Analysis in Forensic Identification Focusing on Short Tandem Repeat- Combined DNA Index System Loci THO1, CSF1PO and TPOX. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2020, 12, 8716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovanelli, A.; Grazinoli Garrido, R.; Rocha, A.; Hessab, T. Touch DNA Recovery from Vehicle Surfaces Using Different Swabs. J. Forensic Sci. 2022, 67, 707–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, D.; Beaumont, D.; Brown, M.; Clayton, T.; Coleman, K.; Subhani, Z.; Thomson, J. An Investigation of Two Methods of DNA Recovery from Fired and Unfired 9 Mm Ammunition. Sci. Justice J. Forensic Sci. Soc. 2021, 61, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoop, B.; Defaux, P.M.; Utz, S.; Zieger, M. Touch DNA Sampling with SceneSafe FastTM Minitapes. Leg. Med. Tokyo Jpn. 2017, 29, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.; Subhani, Z.; Daniel, B.; Frascione, N. Touch DNA—The Prospect of DNA Profiles from Cables. Sci. Justice 2016, 56, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, T.; Ge, J.-Y.; Dong, Y.-Q.; Sun, Q.-F.; Liu, C.; Li, C.-X. Comparison of Preprocessing Methods and Storage Times for Touch DNA Samples. Croat. Med. J. 2017, 58, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyko, T.; Szkuta, B.; Mitchell, R.J.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. Prevalence of DNA from the Driver, Passengers and Others within a Car of an Exclusive Driver. Forensic Sci. Int. 2020, 307, 110139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, T.; Barash, M.; Gunn, P.; Bruce, D. Investigation of DNA Transfer onto Clothing during Regular Daily Activities. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2018, 132, 1035–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- al Oleiwi, A.; Hussain, I.; McWhorter, A.; Sutton, R.; King, R.S.P. DNA Recovery from Latent Fingermarks Treated with an Infrared Fluorescent Fingerprint Powder. Forensic Sci. Int. 2017, 277, e39–e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacerenza, D.; Aneli, S.; Omedei, M.; Gino, S.; Pasino, S.; Berchialla, P.; Robino, C. A Molecular Exploration of Human DNA/RNA Co-Extracted from the Palmar Surface of the Hands and Fingers. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2016, 22, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, Z.E.; Mosse, K.S.A.; Sungaila, A.M.; van Oorschot, R.A.H.; Hartman, D. Detection of Offender DNA Following Skin-to-Skin Contact with a Victim. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2018, 37, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonsu, D.O.M.; Rodie, M.; Higgins, D.; Henry, J.; Austin, J.J. Comparison of IsohelixTM and Rayon Swabbing Systems for Touch DNA Recovery from Metal Surfaces. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2021, 17, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterling, S.-A.; Mason, K.E.; Anex, D.S.; Parker, G.J.; Hart, B.; Prinz, M. Combined DNA Typing and Protein Identification from Unfired Brass Cartridges. J. Forensic Sci. 2019, 64, 1475–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butcher, E.V.; van Oorschot, R.A.H.; Morgan, R.M.; Meakin, G.E. Opportunistic Crimes: Evaluation of DNA from Regularly-Used Knives after a Brief Use by a Different Person. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2019, 42, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dierig, L.; Schmidt, M.; Wiegand, P. Looking for the Pinpoint: Optimizing Identification, Recovery and DNA Extraction of Micro Traces in Forensic Casework. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2020, 44, 102191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bathrick, A.S.; Norsworthy, S.; Plaza, D.T.; McCormick, M.N.; Slack, D.; Ramotowski, R.S. DNA Recovery after Sequential Processing of Latent Fingerprints on Copy Paper. J. Forensic Sci. 2022, 67, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goray, M.; Fowler, S.; Szkuta, B.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. Shedder Status-An Analysis of Self and Non-Self DNA in Multiple Handprints Deposited by the Same Individuals over Time. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2016, 23, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breathnach, M.; Williams, L.; McKenna, L.; Moore, E. Probability of Detection of DNA Deposited by Habitual Wearer and/or the Second Individual Who Touched the Garment. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2016, 20, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kita, T.; Yamaguchi, H.; Yokoyama, M.; Tanaka, T.; Tanaka, N. Morphological Study of Fragmented DNA on Touched Objects. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2008, 3, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oorschot, R.A.H.; Glavich, G.; Mitchell, R.J. Persistence of DNA Deposited by the Original User on Objects after Subsequent Use by a Second Person. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2014, 8, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, J.J.; van Oorschot, R.A.H.; Gunn, P.R.; Walsh, S.J.; Roux, C. Trace DNA Success Rates Relating to Volume Crime Offences. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. Suppl. Ser. 2009, 2, 136–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magee, A.M.; Breathnach, M.; Doak, S.; Thornton, F.; Noone, C.; McKenna, L.G. Wearer and Non-Wearer DNA on the Collars and Cuffs of Upper Garments of Worn Clothing. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2018, 34, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdon, T.J.; Mitchell, R.J.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. Swabs as DNA Collection Devices for Sampling Different Biological Materials from Different Substrates. J. Forensic Sci. 2014, 59, 1080–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomasma, S.M.; Foran, D.R. The Influence of Swabbing Solutions on DNA Recovery from Touch Samples. J. Forensic Sci. 2013, 58, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oorschot, R.A.; Ballantyne, K.N.; Mitchell, R.J. Forensic Trace DNA: A Review. Investig. Genet. 2010, 1, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bruin, K.G.; Verheij, S.M.; Veenhoven, M.; Sijen, T. Comparison of Stubbing and the Double Swab Method for Collecting Offender Epithelial Material from a Victim’s Skin. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2012, 6, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickar, T.; Bache, K.; Daniel, B.; Frascione, N. The Use of the M-Vac® Wet-Vacuum System as a Method for DNA Recovery. Sci. Justice J. Forensic Sci. Soc. 2018, 58, 282–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barash, M.; Reshef, A.; Brauner, P. The Use of Adhesive Tape for Recovery of DNA from Crime Scene Items. J. Forensic Sci. 2010, 55, 1058–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzamiglio, M.; Mameli, A.; My, D.; Garofano, L. Forensic Identification of a Murderer by LCN DNA Collected from the inside of the Victim’s Car. Int. Congr. Ser. 2004, 1261, 437–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).