Abstract

Assisted reproductive technology (ART) is an essential tool to overcome infertility, and is a worldwide disease that affects millions of couples at reproductive age. Sperm selection is a crucial step in ART treatment, as it ensures the use of the highest quality sperm for fertilization, thus increasing the chances of a positive outcome. In recent years, advanced sperm selection strategies for ART have been developed with the aim of mimicking the physiological sperm selection that occurs in the female genital tract. This systematic review sought to evaluate whether advanced sperm selection techniques could improve ART outcomes and sperm quality/functionality parameters compared to traditional sperm selection methods (swim-up or density gradients) in infertile couples. According to preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA guidelines), the inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined in a PICOS (population, intervention, comparator, outcome, study) table. A systematic search of the available literature published in MEDLINE-PubMed until December 2021 was subsequently conducted. Although 4237 articles were recorded after an initial search, only 47 studies were finally included. Most reports (30/47; 63.8%) revealed an improvement in ART outcomes after conducting advanced vs. traditional sperm selection methods. Among those that also assessed sperm quality/functionality parameters (12/47), there was a consensus (10/12; 83.3%) about the beneficial effect of advanced sperm selection methods on these variables. In conclusion, the application of advanced sperm selection methods improves ART outcomes. In spite of this, as no differences in the reproductive efficiency between advanced methods has been reported, none can be pointed out as a gold standard to be conducted routinely. Further research addressing whether the efficiency of each method relies on the etiology of infertility is warranted.

1. Introduction

Alarming data indicate that human fertility is constantly decreasing, which leads to the performance of around 1435 assisted reproductive technology (ART) cycles per million of habitants in Europe every year [1]. Infertility is considered as a disease by the World Health Organization, with an estimated incidence of 8–12% couples at reproductive age worldwide [2]. A male factor is involved in about half of infertility cases, being either the main affectation or a cofactor affecting couple’s fertility. Male factors are related to physiological alterations, such as hypogonadism, erectile dysfunction or retrograde ejaculation, and impaired sperm quality [3,4]. When infertility is due to low sperm quality, ART treatments, such as in vitro fertilization (IVF) or intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), become an alternative to achieve fertilization [4]. While the understanding of ART techniques has increased and great strides to develop novel technologies maximizing their success have been performed, recent data evidence that there are still significant shortcomings to reach satisfactory pregnancy and live birth rates [5].

In the last two decades, research in ART has concentrated on better identifying which factors underlie infertility and, thus, how their handling may increase the chances of successful pregnancy. At present, sperm quality is understood to be one of the key features driving a decrease in both fertilization rates and the proportion of embryos successfully developing to blastocyst stage [6,7]. In addition, mounting evidence suggests that an impairment of sperm DNA integrity causes a reduction of ART outcomes [8]. For this reason, the selection of the most competent sperm cells—i.e., those with the highest fertilizing ability—is crucial to improve both laboratory and clinical outcomes following ART. In this regard, it is worth noticing that sperm selection based on physiological or molecular features has gained much interest from researchers [9,10]. In in vivo fertilization, sperm are subject to natural selection during their journey alongside the female reproductive tract, involving dynamic and morphological features [11]. However, this selection process can be bypassed through ART (mainly ICSI) and, as a result, sperm with alterations may be used to fertilize an oocyte [10]; because of that, sperm selection methods mimicking the female genital tract are the focus of research [12]. Whilst traditional sperm selection techniques, mainly based on sedimentation or migration (swim-up and density gradient centrifugation), are useful to select motile, morphologically normal sperm, there is still room for improvement regarding their efficiency. For this reason, novel selection methods based on other sperm features, such as ultrastructure, surface cell proteins, or DNA integrity, have been developed in the last years [13,14]. These approaches increase the likelihood of selecting structurally intact, viable, and mature sperm with an intact DNA prior to ART, thus enhancing fertilization, embryo development, and pregnancy rates.

Herein, critical literature assessing the effects of conventional and advanced sperm selection methods was systemically reviewed, with the purpose of elucidating whether the latter can be used to improve sperm quality/functionality parameters and/or ART outcomes.

2. Material and Methods

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [15] were followed to conduct the systematic review. The search protocol was registered in the PROSPERO registry (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO (accessed on 10 November 2021)) with the number PROSPERO 2021 ID: CRD42021248949.

2.1. Data Sources and Search Strategy

The MEDLINE-Pubmed database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed (accessed on 13 December 2021)) was utilized to conduct a systematic search of the available literature, which included research studies published until 13 December 2021. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the selected studies were defined prior to the search in a Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome, Study (PICOS) table (Table 1). Based on this table, a list of keywords was set and used for the definition of the search strategy as follows: (infertile OR infertility OR sperm selection OR sperm selection methods OR sperm selection techniques) AND (MSOME OR motile sperm organelle morphology examination OR birefringence OR polarized light microscope OR Raman OR microfluidics OR IMSI OR hyaluronic OR ICSI OR MACS OR magnetic activated cell sorting OR swim-up OR density gradients OR Zeta-potential OR electrophoresis OR Annexin V) AND (Assisted reproduction OR AI OR artificial insemination OR insemination OR IVF OR in vitro fertilization OR ICSI OR intracytoplasmic sperm injection OR intrauterine insemination OR IUI) AND (sperm quality OR sperm function OR motility OR DNA damage OR DNA fragmentation OR oxidative stress OR free radicals OR viability) AND (embryo OR blastocyst OR zygote OR fertility OR pregnancy OR implantation OR live birth OR fertilization). In addition, the filter ‘Species (Humans)’ was applied to comply with the inclusion criteria:

Table 1.

Population, intervention, comparison, outcome, and study (PICOS) design, comprising inclusion and exclusion criteria and the keywords used for the definition of the search strategy and the eligibility of the study.

2.2. Study Eligibility

Articles meeting the inclusion criteria previously defined in the PICOS table (Table 1) were considered in this systematic review. The main criteria were: (i) studies conducted in humans; (ii) articles using an advanced sperm selection technique; (iii) studies comparing advanced vs. traditional sperm selection techniques (e.g., swim-up, density gradients); (iv) studies analyzing sperm quality/functionality parameters before and after applying an advanced sperm selection method; (v) studies assessing the potential influence of advanced sperm selection methods on assisted reproduction outcomes. The main exclusion criteria were: (i) studies conducted in species other than humans; (ii) studies applying an advanced sperm selection method without comparison to traditional sperm selection methods (such as swim-up or density gradients); (iii) studies that did not evaluate sperm quality/functionality parameters and/or fertility outcomes after ART. Research articles, observational studies, cross-sectional studies, comparative studies, and longitudinal studies were eligible, whereas meta-analyses, narrative and systematic reviews, letters, commentary articles, and case reports were declared as non-eligible.

2.3. Study Selection Procedure

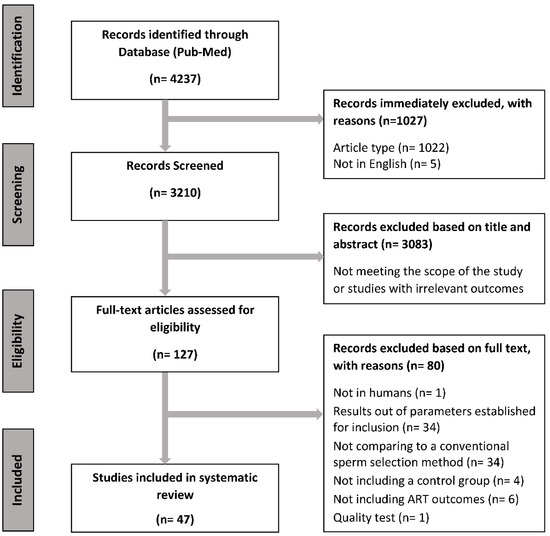

The study selection procedure was performed following the flowchart displayed in Figure 1. After conducting the search at MEDLINE-PubMed, the article list was downloaded as a .txt file using a standardized data extraction (PMID format separated by tabs) with the following information: Pubmed ID, publication date, authors, title, keywords, document type, journal, ISSN, DOI, and abstract. Then, an Excel file including this information was generated. For eligibility, all information included in the Excel file was examined by two researchers (M.S. and J.R.-M.), and any discrepancy was re-evaluated by a third author (I.B.). First, articles declared as non-eligible and/or not written in English were excluded. Second, studies were selected on the basis of their title and abstract, and those that did not meet the eligibility criteria stated in the PICOS table were excluded. Finally, the full text of selected articles was downloaded and read carefully, and the content was analyzed. This led to the final list of articles included in the systematic review.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the literature search and selection procedure.

2.4. Additional Article Quality Screening

An additional step for article quality analysis was performed following NHLBI-NIH guidelines. Specifically, the quality assessment tool for case-control studies http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 20 December 2021), which includes 12 YES/NO questions assessing potential weaknesses that may compromise the quality of a study, was applied. By adding up the answers from the questions, a score value between 0 and 12 was obtained. Studies with a score value < 5 were classified as with “poor quality” and, therefore, excluded from the systematic review.

2.5. Data Extraction for Systematic Review and Statistics

Once articles were selected, they were analyzed to extract the following data: (1) reference, (2) aim of the study, (3) advanced sperm selection technique applied, (4) sample size, (5) female/male inclusion/exclusion factors, (6) fertility/sperm quality and functionality parameters assessed, (7) main results, and (8) conclusions. In addition, an additional row indicating whether the application of the advanced sperm selection method improved at least one fertility/sperm quality or functionality variable was included for each study.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The Chi-square test was run to determine whether advanced sperm selection methods improve sperm quality/functionality parameters and/or ART outcomes. The statistical significance level was set at 95% of the confidence interval (p ≤ 0.05).

3. Results

3.1. Identification and Selection of Studies

Figure 1 shows how articles were selected, referring to inclusion/exclusion reasons. A total of 4237 articles were recorded after the initial search, and after an initial screening for article type and language, and a secondary screening for title and abstract, a total of 127 articles were selected for full-text assessment. Thereafter, 80 articles were excluded based on the criteria established in the PICOS table (Table 1), and one article was excluded based on quality assessment according to the NHLBI-NIH guidelines (Supplementary Table S1). Therefore, a total of 47 studies were declared eligible for qualitative analysis (Figure 1).

3.2. Systematic Review: Qualitative Analysis

The 47 studies included in the systematic review were analyzed to extract the key data as described in the Materials and Methods section and summarized in Table 2 and Table 3. According to the sperm selection technique, 21 articles (21/47; 44.7%) used intra-cytoplasmic morphologically selected sperm injection (IMSI), also named motile sperm organelle morphology examination (MSOME), ten (10/47; 21.3%) performed hyaluronic acid selection (physiological ICSI, PICSI), seven (7/47, 14.9%) conducted magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) for Annexin V, five (5/47, 10.6%) utilized microfluidic devices, two (2/47, 4.3%) used Zeta-potential, one study (1/47; 2.1%) conducted birefringence, and one study (1/47, 2.1%) carried out laser beam selection.

Table 2.

Relevant data of articles included in the systematic review. Abbreviations: ART: assisted reproduction technology; BMI: body mass index; FSH: follicle stimulating hormone; ICSI: intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection; IMSI: intra-cytoplasmic morphologically selected sperm injection; IVF: in vitro fertilization; MII: metaphase II; MACS: magnetic-activated cell sorting; MSOME: motile sperm organelle morphology examination; PICSI: physiological intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection; PVP: polyvinylpyrrolidone.

Table 3.

Summary of all included research articles performing sperm quality analysis before and after the selection method. Abbreviations: IMSI: intra-cytoplasmic morphologically selected sperm injection; MACS: magnetic-activated cell sorting; MSOME: motile sperm organelle morphology examination; PICSI: physiological intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection.

3.3. Influence of Sperm Selection Methods on Sperm Quality and ART Outcomes

Regarding ART outcomes, 30 out of the 47 studies (63.8%) revealed an improvement in fertility results after applying advanced sperm selection methods. Specifically, and sorted by sperm selection method, ART outcomes were found to be improved in 12 of the 21 articles (57.1%) using IMSI or MSOME; in seven of the 10 articles (70%) conducting PICSI; in six of the seven articles (85.7%) performing MACS; in two of the five articles (40%) utilizing a microfluidic device; and in one of the two articles (50%) using Zeta-potential. Studies assessing birefringence and laser beam were also able to boost sperm fertilizing ability. The percentage of studies finding an improvement of ART outcomes, however, did not differ between sperm selection techniques (p = 0.585).

The studies reporting ART outcomes also determined the potential effects on sperm quality/functionality parameters that were extracted so as to address whether an improvement on ART outcomes was associated with an increase in sperm quality/functionality variables. Twelve studies assessed sperm quality/functionality parameters before and after semen samples were subject to sperm selection. Among them, ten articles (83.3%) showed a beneficial effect of advanced sperm selection methods on sperm quality/functionality parameters compared to the control. Nine of these ten studies also found an improvement in ART outcomes (90%), thus showing that such a beneficial effect was concomitant with an increased sperm quality.

4. Discussion

The present study systematically reviewed the available literature to address whether using advanced sperm selection techniques before ART treatment (mainly ICSI) improves ART outcomes. After applying the defined inclusion/exclusion criteria and assessing the quality of studies, 47 articles were chosen. The advanced sperm selection methods in most of these studies were IMSI, PICSI, or MACS; in contrast, laser, birefringence, zeta-potential, and microfluidics were less investigated.

4.1. Using Advanced Sperm Selection Techniques Improves ART Outcomes

Most studies included in this systematic review (30/47) showed an improvement of ART outcomes when semen samples were subject to advanced sperm selection techniques, in comparison to conventional sperm selection methods. However, no advanced sperm selection technique was found to be better than another, as the use of the same method in a similar cohort brought inconsistent outcomes.

IMSI, also known as MSOME, selects sperm without vacuoles in the cytoplasm under a microscope with high magnification (over 6000×) [63]. Using this method, most of the studies compiled herein (57.2%) revealed an improvement in ART outcomes [16,18,20,22,25,26,28,30,33,35,36]. Other articles (42.8%), however, did not find differences between advanced and traditional sperm selection methods regarding ART outcomes [19,21,23,24,29,31,32,34]. Differences in laboratory/clinical procedures or in exclusion/inclusion factors, such as patient selection criteria (age, female factors or male factors), could be behind these inconsistent results. For instance, all studies that limited the female age as an inclusion criterion observed greater fertilization, blastocyst, implantation, pregnancy and live birth rates, and higher embryo quality [16,18,25,26,27,28,30,33,35,36]. Moreover, certain clinical characteristics could also condition the success of IMSI in improving ART outcomes. Indeed, Oliveira et al. [32] and Gatimel et al. [24] did not find statistically significant differences in pregnancy and implantation rates between IMSI and conventional ICSI in patients with recurrent implantation failure. Similarly, the study by Boediono et al. [21] included females with severe endometriosis and observed no improvement in clinical pregnancy rates. Not only do these studies suggest that the success of IMSI relies on the patient, but they also support that further research should include a larger sample size to establish in which clinical conditions IMSI could bring the most benefit.

As far as sperm selection by PICSI is concerned, most of the included studies (70%) reported an improvement on ART outcomes compared to conventional selection methods [38,39,40,43,44,45,46]. Selection through PICSI relies on a specific receptor present in mature sperm, which allows them to bind hyaluronic acid, a component surrounding cumulus cells. This technique thus mimics the natural selection of sperm upon interaction with oocyte vestments [64]. Amongst all studies, those that investigated the male factor of infertility showed a statistically significant improvement on ART outcomes [38,39,40]. The effects of PICSI were more evident when the age of the females was controlled as an inclusion factor. Three studies that limited female age as an inclusion criterion, studying females up to 38–40 years old, proved that PICSI showed higher ART outcomes than conventional ICSI [43,45,46]. Because female age is well known to be a factor that impacts negatively on ART outcomes, mainly due to an increase of oocyte aneuploidies [65], the assessment of younger females could help reduce the bias detected. In fact, all studies that did not find an improvement of ART outcomes after PICSI selection included females of up to 42–43 years old [37,41,42]. Other studies conducted in animal models, such as the pig, found an increase of embryo euploidy after conducting ICSI with hyaluronic acid-selected sperm cells [66]. Hence, while a high proportion of studies supports the use of PICSI to select sperm, this technique is more suitable when the oocyte comes from a young female.

With regard to MACS, this method is based on the conjugation of Annexin V to magnetic microspheres, which are exposed to a magnetic field in an affinity column that allows an effective separation of apoptotic from non-apoptotic sperm [67]. Most research works (85.7%) focused on this technique found an improvement on ART outcomes compared to conventional sperm selection methods. In four studies, female exclusion factors were applied (advanced female age, hormonal levels, number of oocytes after ovarian stimulation, or other physiological alterations) and an improvement in blastocyst quality, implantation, pregnancy rates, and a decrease in miscarriage rates were observed [47,50,52,53]. In two studies, male factors based on sperm quality/functionality parameters were also controlled as inclusion factors, and an improvement of MACS vs. conventional ICSI regarding the quality of blastocysts and a lower rate of miscarriages were reported [50,52].

Advanced sperm selection methods that have hitherto been less studied also met the inclusion criteria defined for the present systematic review: microfluidics sperm sorting, Zeta-potential, birefringence, and laser beam. Microfluidic sperm selection has arisen as a promising method, mimicking the microgeometry of the female reproductive tract and promoting sperm movement that is more similar to movement in a natural environment [68]. Most of the studies (60%) assessing the impact of microfluidics on ART outcomes found no differences compared to traditional sperm selection methods [54,56,57]. Considering only studies with a large sample size, one involving 116 infertile couples found that microfluidics led to greater ART outcomes compared to conventional methods, whereas another, committing 91 patients, observed no differences in clinical pregnancies [54,58]. In the light of the aforementioned information, larger randomized trials are required to evaluate the potential beneficial effect of this promising method. Concerning Zeta-potential, whereas one of the two studies that applied this technology reported a beneficial effect on ART outcomes in a population of 30 couples [60], the other, involving 54 couples, found no differences [59]. It is worth mentioning that while Kheirollahi-Kouhestani et al. [60] used unselected semen specimens, samples with at least one altered seminal parameter were used in the study of Duarte et al. [59], which could explain these different results. With regard to birefringence, this method relies on the use of Nomarski interference contrast to evaluate the refringence associated with the orientation of nucleoprotein filaments. The study of Gianaroli et al. [61] reported an improvement in the proportion of high-quality embryos on day 3 and in their ability to implant and progress beyond 16 weeks of gestation in a population of 231 couples. In the same way, an improvement in fertility and cleavage rates was observed when a laser beam was applied for the detection and selection of viable but immotile sperm in a population of 77 couples with complete asthenozoospermia [62]. This would suggest that this technique could improve ICSI outcomes in asthenozoospermic patients. However, and because only a very low number of studies are available, more research into the aforementioned methods is needed.

4.2. Advanced Sperm Selection Techniques Increase ART Outcomes through an Improvement of Sperm Quality/Functionality Variables

As a secondary outcome, this systematic review aimed to address whether advanced sperm selection techniques improve sperm quality/functionality parameters. Ten out of twelve studies found that advanced selection techniques improved both sperm quality/functionality parameters and ART outcomes. Among the four articles assessing the effect of IMSI on sperm quality and fertility, three reported that IMSI-selected sperm showed less DNA fragmentation [30,36]. Other studies investigating the effects of this method on sperm quality observed that the presence of vacuoles in sperm nuclei were related to impaired sperm quality, chromosomal aneuploidies, chromatin condensation defects and DNA damage [31,69,70].In the case of PICSI, only one of the included studies looking into ART outcomes evaluated the effects on sperm quality, finding a negative relationship between hyaluronan-bound sperm and the incidence of DNA fragmentation [44]. This concurred with other research demonstrating that hyaluronan-bound sperm are more likely to exhibit intact DNA [71]. The effects of MACS on sperm quality were assessed in two of the included studies (Romany et al., 2014; Merino-Ruiz et al., 2019). While no differences on sperm motility were found after MACS in the study with the largest population (263 samples) [49], another report, involving 92 samples, observed an improvement in sperm motility, viability, and morphology. Related to this, other research not included in this review—as it only evaluated the effects of MACS on sperm quality—found that sperm selected through this method exhibited lower DNA fragmentation, and higher mitochondrial membrane potential, sperm motility, and morphology [72,73]. Regarding microfluidics, only two of the included studies assessed sperm quality and found greater sperm motility and morphology and DNA integrity [55,58]. Again, these results agree with other reports showing similar outcomes [74,75]. As far as Zeta-potential is concerned, studies assessing sperm quality observed lower sperm DNA fragmentation after sperm selection, leading to an increase in ART outcomes [59,60]. In another study comparing Zeta-potential to other sperm selection methods, both MACS and Zeta-potential were able to increase the proportion of sperm with normal morphology and an intact DNA [76]. In addition, Zeta-potential was seen to be more efficient than binding to hyaluronic acid in the selection of sperm with an intact DNA [77]. Clinical evidence supports sperm DNA damage as a detrimental factor for reproductive outcomes [78,79]. Furthermore, the presence of sperm undergoing apoptotic-like changes in semen is related to male infertility [80,81]. In eight of the nine included studies, advanced selection methods were demonstrated to be better than the traditional ones to select sperm with an intact DNA [25,30,36,44,55,58,59,60]. Thus, only one study, involving 255 couples, found no differences in this parameter [29].

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

Overall, for the present systematic review, a great variability in the inclusion/exclusion factors was observed among the selected studies, highlighting the difficulty of comparing the results. All these factors underlie a potential risk of bias in systematic reviews, including the current one. For this reason, more studies including larger sample size and considering specific inclusion/exclusion factors are necessary to elucidate the effects on a specific cohort of infertile patients. In addition to that, publication bias might be present, as negative results may not be published to the same extent as positive outcomes do.

5. Conclusions

The comparison of advanced vs. traditional sperm selection methods (swim-up and density gradients) evidenced that the application of the former leads to an improvement in ART outcomes. Because the efficiency of such an improvement was found to be similar between methods, none appear to be better than another when dealing with the entire infertile population. This supports the need to define under which clinical conditions a particular method is more useful. Finally, this systematic review supports that not only do advanced selection methods improve ART outcomes, but also improve semen quality parameters, which leads one to suggest that the increase in the latter has a positive repercussion on the former.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms232213859/s1.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the support from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie agreement No. 801342 (Grant: TECSPR-19-1-0003), the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant: H2020-MSCA-IF-2019-891382), the Regional Government of Catalonia, Spain (Grant: 2017-SGR-1229), La Marató de TV3 Foundation (214/857-202039), and the Catalan Institution for Research and Advanced Studies (ICREA).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data generated during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Dyer, S.; Chambers, G.M.; de Mouzon, J.; Nygren, K.G.; Zegers-Hochschild, F.; Mansour, R.; Ishihara, O.; Banker, M.; Adamson, G.D. International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technologies World Report: Assisted Reproductive Technology 2008, 2009 and 2010. Hum. Reprod. 2016, 31, 1588–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datta, J.; Palmer, M.J.; Tanton, C.; Gibson, L.J.; Jones, K.G.; Macdowall, W.; Glasier, A.; Sonnenberg, P.; Field, N.; Mercer, C.H.; et al. Prevalence of Infertility and Help Seeking among 15 000 Women and Men. Hum. Reprod. 2016, 31, 2108–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, A.; Mulgund, A.; Hamada, A.; Chyatte, M.R. A Unique View on Male Infertility around the Globe. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2015, 13, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, N.; Singh, A.K. Trends of Male Factor Infertility, an Important Cause of Infertility: A Review of Literature. J. Hum. Reprod. Sci. 2015, 8, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyns, C.; De Geyter, C.; Calhaz-Jorge, C.; Kupka, M.; Motrenko, T.; Smeenk, J.; Bergh, C.; Tandler-Schneider, A.; Rugescu, I.; Goossens, V. ART in Europe, 2018: Results Generated from European Registries by ESHRE. Hum. Reprod. Open 2022, 2022, hoac022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakkas, D.; Manicardi, G.C.; Tomlinson, M.; Mandrioli, M.; Bizzaro, D.; Bianchi, P.G.; Bianchi, U. The Use of Two Density Gradient Centrifugation Techniques and the Swim-up Method to Separate Spermatozoa with Chromatin and Nuclear DNA Anomalies. Hum. Reprod. 2000, 15, 1112–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loutradi, K.E.; Tarlatzis, B.C.; Goulis, D.G.; Zepiridis, L.; Pagou, T.; Chatziioannou, E.; Grimbizis, G.F.; Papadimas, I.; Bontis, I. The Effects of Sperm Quality on Embryo Development after Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2006, 23, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribas-Maynou, J.; Yeste, M.; Becerra-Tomás, N.; Aston, K.K.I.; James, E.E.R.; Salas-Huetos, A. Clinical Implications of Sperm DNA Damage in IVF and ICSI: Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biol. Rev. 2021, 96, 1284–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messerlian, C.; Gaskins, A.J. Epidemiologic Approaches for Studying Assisted Reproductive Technologies: Design, Methods, Analysis and Interpretation. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 2017, 4, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.-L.; Agarwal, A. Role of Sperm DNA Fragmentation in Male Factor Infertility: A Systematic Review. Arab. J. Urol. 2018, 16, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldini, D.; Ferri, D.; Baldini, G.M.; Lot, D.; Catino, A.; Vizziello, D.; Vizziello, G. Sperm Selection for ICSI: Do We Have a Winner? Cells 2021, 10, 3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, R.; Coomarasamy, A.; Frew, L.; Hutton, R.; Kirkman-Brown, J.; Lawlor, M.; Lewis, S.; Partanen, R.; Payne-Dwyer, A.; Román-Montañana, C.; et al. Sperm Selection with Hyaluronic Acid Improved Live Birth Outcomes among Older Couples and Was Connected to Sperm DNA Quality, Potentially Affecting All Treatment Outcomes. Hum. Reprod. 2022, 37, 1106–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huszar, G.; Ozkavukcu, S.; Jakab, A.; Celik-Ozenci, C.; Sati, G.L.; Cayli, S. Hyaluronic Acid Binding Ability of Human Sperm Reflects Cellular Maturity and Fertilizing Potential: Selection of Sperm for Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 18, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasanen, E.; Elqusi, K.; ElTanbouly, S.; Hussin, A.E.G.; AlKhadr, H.; Zaki, H.; Henkel, R.; Agarwal, A. PICSI vs. MACS for Abnormal Sperm DNA Fragmentation ICSI Cases: A Prospective Randomized Trial. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2020, 37, 2605–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antinori, M.; Licata, E.; Dani, G.; Cerusico, F.; Versaci, C.; d’Angelo, D.; Antinori, S. Intracytoplasmic Morphologically Selected Sperm Injection: A Prospective Randomized Trial. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2008, 16, 835–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaban, B.; Yakin, K.; Alatas, C.; Oktem, O.; Isiklar, A.; Urman, B. Clinical Outcome of Intracytoplasmic Injection of Spermatozoa Morphologically Selected under High Magnification: A Prospective Randomized Study. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2011, 22, 472–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bartoov, B.; Berkovitz, A.; Eltes, F.; Kogosovsky, A.; Yagoda, A.; Lederman, H.; Artzi, S.; Gross, M.; Barak, Y. Pregnancy Rates Are Higher with Intracytoplasmic Morphologically Selected Sperm Injection than with Conventional Intracytoplasmic Injection. Fertil. Steril. 2003, 80, 1413–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkovitz, A.; Eltes, F.; Ellenbogen, A.; Peer, S.; Feldberg, D.; Bartoov, B. Does the Presence of Nuclear Vacuoles in Human Sperm Selected for ICSI Affect Pregnancy Outcome? Hum. Reprod. 2006, 21, 1787–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkovitz, A.; Eltes, F.; Lederman, H.; Peer, S.; Ellenbogen, A.; Feldberg, B.; Bartoov, B. How to Improve IVF-ICSI Outcome by Sperm Selection. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2006, 12, 634–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boediono, A.; Handayani, N.; Sari, H.N.; Yusup, N.; Indrasari, W.; Polim, A.A.; Sini, I. Morphokinetics of Embryos after IMSI versus ICSI in Couples with Sub-Optimal Sperm Quality: A Time-Lapse Study. Andrologia 2021, 53, e14002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaroche, L.; Yazbeck, C.; Gout, C.; Kahn, V.; Oger, P.; Rougier, N. Intracytoplasmic Morphologically Selected Sperm Injection (IMSI) after Repeated IVF or ICSI Failures: A Prospective Comparative Study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2013, 167, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspard, O.; Vanderzwalmen, P.; Wirleitner, B.; Ravet, S.; Wenders, F.; Eichel, V.; Mocková, A.; Spitzer, D.; Jouan, C.; Gridelet, V.; et al. Impact of High Magnification Sperm Selection on Neonatal Outcomes: A Retrospective Study. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2018, 35, 1113–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatimel, N.; Parinaud, J.; Leandri, R.D. Intracytoplasmic Morphologically Selected Sperm Injection (IMSI) Does Not Improve Outcome in Patients with Two Successive IVF-ICSI Failures. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2016, 33, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazout, A.; Dumont-Hassan, M.; Junca, A.M.; Bacrie, P.C.; Tesarik, J. High-Magnification ICSI Overcomes Paternal Effect Resistant to Conventional ICSI. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2006, 12, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabulut, S.; Aksunger, O.; Korkmaz, O.; Eren Gozel, H.; Keskin, I. Intracytoplasmic Morphologically Selected Sperm Injection, but for Whom? Zygote 2019, 27, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knez, K.; Zorn, B.; Tomazevic, T.; Vrtacnik-Bokal, E.; Virant-Klun, I. The IMSI Procedure Improves Poor Embryo Development in the Same Infertile Couples with Poor Semen Quality: A Comparative Prospective Randomized Study. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2011, 9, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knez, K.; Tomazevic, T.; Zorn, B.; Vrtacnik-Bokal, E.; Virant-Klun, I. Intracytoplasmic Morphologically Selected Sperm Injection Improves Development and Quality of Preimplantation Embryos in Teratozoospermia Patients. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2012, 25, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leandri, R.D.; Gachet, A.; Pfeffer, J.; Celebi, C.; Rives, N.; Carre-Pigeon, F.; Kulski, O.; Mitchell, V.; Parinaud, J. Is Intracytoplasmic Morphologically Selected Sperm Injection (IMSI) Beneficial in the First ART Cycle? A Multicentric Randomized Controlled Trial. Andrology 2013, 1, 692–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangoli, E.; Khalili, M.A.; Talebi, A.R.; Mehdi Kalantar, S.; Montazeri, F.; Agharahimi, A.; Woodward, B.J. Association between Early Embryo Morphokinetics plus Transcript Levels of Sperm Apoptotic Genes and Clinical Outcomes in IMSI and ICSI Cycles of Male Factor Patients. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2020, 37, 2555–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauri, A.L.; Petersen, C.G.; Oliveira, J.B.A.; Massaro, F.C.; Baruffi, R.L.R.; Franco, J.G. Comparison of Day 2 Embryo Quality after Conventional ICSI versus Intracytoplasmic Morphologically Selected Sperm Injection (IMSI) Using Sibling Oocytes. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2010, 150, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.B.A.; Cavagna, M.; Petersen, C.G.; Mauri, A.L.; Massaro, F.C.; Silva, L.F.I.; Baruffi, R.L.R.; Franco, J.G. Pregnancy Outcomes in Women with Repeated Implantation Failures after Intracytoplasmic Morphologically Selected Sperm Injection (IMSI). Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2011, 9, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setti, A.S.; Figueira, R.C.S.; Braga, D.P.A.F.; Aoki, T.; Iaconelli, A.J.; Borges, E.J. Intracytoplasmic Morphologically Selected Sperm Injection Is Beneficial in Cases of Advanced Maternal Age: A Prospective Randomized Study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2013, 171, 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setti, A.S.; Braga, D.P.A.F.; Figueira, R.C.S.; Iaconelli, A.; Borges, E. Poor-Responder Patients Do Not Benefit from Intracytoplasmic Morphologically Selected Sperm Injection. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2015, 32, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shalom-Paz, E.; Anabusi, S.; Michaeli, M.; Karchovsky-Shoshan, E.; Rothfarb, N.; Shavit, T.; Ellenbogen, A. Can Intra Cytoplasmatic Morphologically Selected Sperm Injection (IMSI) Technique Improve Outcome in Patients with Repeated IVF-ICSI Failure? A Comparative Study. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2015, 31, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilding, M.; Coppola, G.; Di Matteo, L.; Palagiano, A.; Fusco, E.; Dale, B. Intracytoplasmic Injection of Morphologically Selected Spermatozoa (IMSI) Improves Outcome after Assisted Reproduction by Deselecting Physiologically Poor Quality Spermatozoa. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2011, 28, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, S.A.; Tae, J.C.; Shin, M.Y.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, C.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Hwang, D.; Kim, K.C.; Suh, C.S.; Jee, B.C. Application of Sperm Selection Using Hyaluronic Acid Binding in Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection Cycles: A Sibling Oocyte Study. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2012, 27, 1569–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erberelli, R.F.; de Salgado, R.M.; Pereira, D.H.M.; Wolff, P. Hyaluronan-Binding System for Sperm Selection Enhances Pregnancy Rates in ICSI Cycles Associated with Male Factor Infertility. J. Bras. Reprod. Assist. 2017, 21, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Kim, H.; Kim, T.H.; Jeong, J.; Lee, W.S.; Lyu, S.W. Effect of Sperm Selection Using Hyaluronan on Fertilization and Quality of Cleavage-Stage Embryos in Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection (ICSI) Cycles of Couples with Severe Teratozoospermia. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2020, 36, 456–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Feenan, K.; Chapple, V.; Roberts, P.; Matson, P. Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection Using Hyaluronic Acid or Polyvinylpyrrolidone: A Time-Lapse Sibling Oocyte Study. Hum. Fertil. 2019, 22, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, G.; Majumdar, A. A Prospective Randomized Study to Evaluate the Effect of Hyaluronic Acid Sperm Selection on the Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection Outcome of Patients with Unexplained Infertility Having Normal Semen Parameters. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2013, 30, 1471–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Pavitt, S.; Sharma, V.; Forbes, G.; Hooper, R.; Bhattacharya, S.; Kirkman-Brown, J.; Coomarasamy, A.; Lewis, S.; Cutting, R.; et al. Physiological, Hyaluronan-Selected Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection for Infertility Treatment (HABSelect): A Parallel, Two-Group, Randomised Trial. Lancet 2019, 393, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokánszki, A.; Tóthné, E.V.; Bodnár, B.; Tándor, Z.; Molnár, Z.; Jakab, A.; Ujfalusi, A.; Oláh, É. Is Sperm Hyaluronic Acid Binding Ability Predictive for Clinical Success of Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection: PICSI vs. ICSI? Syst. Biol. Reprod. Med. 2014, 60, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr-Esfahani, M.H.; Razavi, S.; Vahdati, A.A.; Fathi, F.; Tavalaee, M. Evaluation of Sperm Selection Procedure Based on Hyaluronic Acid Binding Ability on ICSI Outcome. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2008, 25, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmegiani, L.; Cognigni, G.E.; Bernardi, S.; Troilo, E.; Ciampaglia, W.; Filicori, M. “Physiologic ICSI”: Hyaluronic Acid (HA) Favors Selection of Spermatozoa without DNA Fragmentation and with Normal Nucleus, Resulting in Improvement of Embryo Quality. Fertil. Steril. 2010, 93, 598–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worrilow, K.C.; Eid, S.; Woodhouse, D.; Perloe, M.; Smith, S.; Witmyer, J.; Ivani, K.; Khoury, C.; Ball, G.D.; Elliot, T.; et al. Use of Hyaluronan in the Selection of Sperm for Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection (ICSI): Significant Improvement in Clinical Outcomes-Multicenter, Double-Blinded and Randomized Controlled Trial. Hum. Reprod. 2013, 28, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirican, E.K.; Özgün, O.D.; Akarsu, S.; Akin, K.O.; Ercan, Ö.; Uǧurlu, M.; Çamsari, Ç.; Kanyilmaz, O.; Kaya, A.; Ünsal, A. Clinical Outcome of Magnetic Activated Cell Sorting of Non-Apoptotic Spermatozoa before Density Gradient Centrifugation for Assisted Reproduction. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2008, 25, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino-Ruiz, M.; Morales-Martínez, F.A.; Navar-Vizcarra, E.; Valdés-Martínez, O.H.; Sordia-Hernández, L.H.; Saldívar-Rodríguez, D.; Vidal-Gutiérrez, O. The Elimination of Apoptotic Sperm in IVF Procedures and Its Effect on Pregnancy Rate. J. Bras. Reprod. Assist. 2019, 23, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romany, L.; Garrido, N.; Motato, Y.; Aparicio, B.; Remohí, J.; Meseguer, M. Removal of Annexin V-Positive Sperm Cells for Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection in Ovum Donation Cycles Does Not Improve Reproductive Outcome: A Controlled and Randomized Trial in Unselected Males. Fertil. Steril. 2014, 102, 1567–1575.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Martín, P.; Dorado-Silva, M.; Sánchez-Martín, F.; González Martínez, M.; Johnston, S.D.; Gosálvez, J. Magnetic Cell Sorting of Semen Containing Spermatozoa with High DNA Fragmentation in ICSI Cycles Decreases Miscarriage Rate. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2017, 34, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikhi, A.; Jalali, M.; Gholamian, M.; Jafarzadeh, A.; Jannati, S.; Mousavifar, N. Elimination of Apoptotic Spermatozoa by Magnetic-Activated Cell Sorting Improves the Fertilization Rate of Couples Treated with ICSI Procedure. Andrology 2013, 1, 845–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stimpfel, M.; Verdenik, I.; Zorn, B.; Virant-Klun, I. Magnetic-Activated Cell Sorting of Non-Apoptotic Spermatozoa Improves the Quality of Embryos According to Female Age: A Prospective Sibling Oocyte Study. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2018, 35, 1665–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziarati, N.; Tavalaee, M.; Bahadorani, M.; Nasr Esfahani, M.H. Clinical Outcomes of Magnetic Activated Sperm Sorting in Infertile Men Candidate for ICSI. Hum. Fertil. 2019, 22, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcan, P.; Takmaz, T.; Yazici, M.G.K.; Alagoz, O.A.; Yesiladali, M.; Sevket, O.; Ficicioglu, C. Does the Use of Microfluidic Sperm Sorting for the Sperm Selection Improve in Vitro Fertilization Success Rates in Male Factor Infertility? J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2021, 47, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrella, A.; Keating, D.; Cheung, S.; Xie, P.; Stewart, J.D.; Rosenwaks, Z.; Palermo, G.D. A Treatment Approach for Couples with Disrupted Sperm DNA Integrity and Recurrent ART Failure. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2019, 36, 2057–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalcinkaya Kalyan, E.; Can Celik, S.; Okan, O.; Akdeniz, G.; Karabulut, S.; Caliskan, E. Does a Microfluidic Chip for Sperm Sorting Have a Positive Add-on Effect on Laboratory and Clinical Outcomes of Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection Cycles? A Sibling Oocyte Study. Andrologia 2019, 51, e13403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetkinel, S.; Kilicdag, E.B.; Aytac, P.C.; Haydardedeoglu, B.; Simsek, E.; Cok, T. Effects of the Microfluidic Chip Technique in Sperm Selection for Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection for Unexplained Infertility: A Prospective, Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2019, 36, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, K.; Yuksel, S. Use of Microfluidic Sperm Extraction Chips as an Alternative Method in Patients with Recurrent in Vitro Fertilisation Failure. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2019, 36, 1423–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, C.; Núñez, V.; Wong, Y.; Vivar, C.; Benites, E.; Rodriguez, U.; Vergara, C.; Ponce, J. Impact of the Z Potential Technique on Reducing the Sperm DNA Fragmentation Index, Fertilization Rate and Embryo Development. J. Bras. Reprod. Assist. 2017, 21, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheirollahi-Kouhestani, M.; Razavi, S.; Tavalaee, M.; Deemeh, M.R.; Mardani, M.; Moshtaghian, J.; Nasr-Esfahani, M.H. Selection of Sperm Based on Combined Density Gradient and Zeta Method May Improve ICSI Outcome. Hum. Reprod. 2009, 24, 2409–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianaroli, L.; Magli, M.C.; Collodel, G.; Moretti, E.; Ferraretti, A.P.; Baccetti, B. Sperm Head’s Birefringence: A New Criterion for Sperm Selection. Fertil. Steril. 2008, 90, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aktan, T.M.; Montag, M.; Duman, S.; Gorkemli, H.; Rink, K.; Yurdakul, T. Use of a Laser to Detect Viable but Immotile Spermatozoa. Andrologia 2004, 36, 366–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, D.M.; Hadyme Miyague, A.; Barbosa, M.A.; Navarro, P.A.; Raine-Fenning, N.; Nastri, C.O.; Martins, W.P. Regular (ICSI) versus Ultra-High Magnification (IMSI) Sperm Selection for Assisted Reproduction. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 2, CD010167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutnisky, C.; Dalvit, G.C.; Pintos, L.N.; Thompson, J.G.; Beconi, M.T.; Cetica, P.D. Influence of Hyaluronic Acid Synthesis and Cumulus Mucification on Bovine Oocyte in Vitro Maturation, Fertilisation and Embryo Development. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2007, 19, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keefe, D.; Kumar, M.; Kalmbach, K. Oocyte Competency Is the Key to Embryo Potential. Fertil. Steril. 2015, 103, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, Y.P.; Sang, J.U.; Sang, J.S.; Kwang, S.K.; Seung, B.H.; Kil, S.C.; Park, C.; Lee, H.T. Increase of ICSI Efficiency with Hyaluronic Acid Binding Sperm for Low Aneuploidy Frequency in Pig. Theriogenology 2005, 64, 1158–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, M.; Sar-Shalom, V.; Melendez Sivira, Y.; Carreras, R.; Checa, M.A. Sperm Selection Using Magnetic Activated Cell Sorting (MACS) in Assisted Reproduction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2013, 30, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosrati, R.; Graham, P.J.; Zhang, B.; Riordon, J.; Lagunov, A.; Hannam, T.G.; Escobedo, C.; Jarvi, K.; Sinton, D. Microfluidics for Sperm Analysis and Selection. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2017, 14, 707–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, J.G.; Mauri, A.L.; Petersen, C.G.; Massaro, F.C.; Silva, L.F.I.; Felipe, V.; Cavagna, M.; Pontes, A.; Baruffi, R.L.R.; Oliveira, J.B.A.; et al. Large Nuclear Vacuoles Are Indicative of Abnormal Chromatin Packaging in Human Spermatozoa. Int. J. Androl. 2012, 35, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdrix, A.; Travers, A.; Chelli, M.H.; Escalier, D.; Do Rego, J.L.; Milazzo, J.P.; Mousset-Simon, N.; Mac, B.; Rives, N. Assessment of Acrosome and Nuclear Abnormalities in Human Spermatozoa with Large Vacuoles. Hum. Reprod. 2011, 26, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarozzi, N.; Nadalini, M.; Stronati, A.; Bizzaro, D.; Dal Prato, L.; Coticchio, G.; Borini, A. Anomalies in Sperm Chromatin Packaging: Implications for Assisted Reproduction Techniques. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2009, 18, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Liu, C.H.; Shih, Y.T.; Tsao, H.M.; Huang, C.C.; Chen, H.H.; Lee, M.S. Magnetic-Activated Cell Sorting for Sperm Preparation Reduces Spermatozoa with Apoptotic Markers and Improves the Acrosome Reaction in Couples with Unexplained Infertility. Hum. Reprod. 2010, 25, 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deemeh, M.R.; Mesbah-Namin, S.A.; Movahedin, M. Selecting Motile, Non-Apoptotic and Induced Spermatozoa for Capacitation without Centrifuging by MACS-Up Method. Andrologia 2022, 54, e14405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinn, M.M.; Jalalian, L.; Ribeiro, S.; Ona, K.; Demirci, U.; Cedars, M.I.; Rosen, M.P. Microfluidic Sorting Selects Sperm for Clinical Use with Reduced DNA Damage Compared to Density Gradient Centrifugation with Swim-up in Split Semen Samples. Hum. Reprod. 2018, 33, 1388–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göde, F.; Gürbüz, A.S.; Tamer, B.; Pala, I.; Isik, A.Z. The Effects of Microfluidic Sperm Sorting, Density Gradient and Swim-up Methods on Semen Oxidation Reduction Potential. Urol. J. 2020, 17, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahedi, A.; Tavalaee, M.; Deemeh, M.R.; Azadi, L.; Fazilati, M.; Nasr-Esfahani, M.H. Zeta Potential vs Apoptotic Marker: Which Is More Suitable for ICSI Sperm Selection? J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2013, 30, 1181–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, S.H.; Nasr-Esfahani, M.H.; Deemeh, M.R.; Shayesteh, M.; Tavalaee, M. Evaluation of Zeta and HA-Binding Methods for Selection of Spermatozoa with Normal Morphology, Protamine Content and DNA Integrity. Andrologia 2010, 42, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, J.J.A.; Barnhart, K.T.K.; Schlegel, P.P.N. Do Sperm DNA Integrity Tests Predict Pregnancy with in Vitro Fertilization? Fertil. Steril. 2008, 89, 823–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meseguer, M.; Santiso, R.; Garrido, N.; García-Herrero, S.; Remohí, J.; Fernandez, J.L. Effect of Sperm DNA Fragmentation on Pregnancy Outcome Depends on Oocyte Quality. Fertil. Steril. 2011, 95, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido, N.; Remohi, J.; Martínez-Conejero, J.A.; García-Herrero, S.; Pellicer, A.; Meseguer, M. Contribution of Sperm Molecular Features to Embryo Quality and Assisted Reproduction Success. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2008, 17, 855–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, N.; Martínez-Conejero, J.A.; Jauregui, J.; Horcajadas, J.A.; Simón, C.; Remohí, J.; Meseguer, M. Microarray Analysis in Sperm from Fertile and Infertile Men without Basic Sperm Analysis Abnormalities Reveals a Significantly Different Transcriptome. Fertil. Steril. 2009, 91, 1307–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).