Abstract

Several human diseases are caused by viruses, including cancer, Type I diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, and hepatocellular carcinoma. In the past, people have suffered greatly from viral diseases such as polio, mumps, measles, dengue fever, SARS, MERS, AIDS, chikungunya fever, encephalitis, and influenza. Recently, COVID-19 has become a pandemic in most parts of the world. Although vaccines are available to fight the infection, their safety and clinical trial data are still questionable. Social distancing, isolation, the use of sanitizer, and personal productive strategies have been implemented to prevent the spread of the virus. Moreover, the search for a potential therapeutic molecule is ongoing. Based on experiences with outbreaks of SARS and MERS, many research studies reveal the potential of medicinal herbs/plants or chemical compounds extracted from them to counteract the effects of these viral diseases. COVID-19′s current status includes a decrease in infection rates as a result of large-scale vaccination program implementation by several countries. But it is still very close and needs to boost people’s natural immunity in a cost-effective way through phytomedicines because many underdeveloped countries do not have their own vaccination facilities. In this article, phytomedicines as plant parts or plant-derived metabolites that can affect the entry of a virus or its infectiousness inside hosts are described. Finally, it is concluded that the therapeutic potential of medicinal plants must be analyzed and evaluated entirely in the control of COVID-19 in cases of uncontrollable SARS infection.

1. Introduction

Several human diseases are caused by viruses, including cancer, Type I diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, and hepatocellular carcinoma. In the past, people have greatly suffered from viral diseases such as polio, mumps, measles, dengue fever, SARS, MERS, AIDS, chikungunya fever, encephalitis, and influenza. Human cancer viruses include the hepatitis B virus, the Epstein-Barr virus, the hepatitis C virus, the human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1, high-risk human papilloma viruses, and Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus [1]. Human enterovirus (HEV) has long been thought to act as an environmental trigger for the onset of Type 1 diabetes (T1D) in people [2]. HHV-6A and HHV-7, two human herpesviruses, may be major causes of AD; however, HSV infection with other viral infections has been documented in some of these cases [3]. The disease 2019-nCoV originated in Wuhan, China, at the end of December 2019, and the WHO declared it an international emergency with public health concerns and issued International Health Regulations [4]. The disease is a pandemic and ongoing; therefore, it is critical to search for new preventive and therapeutic methods as soon as possible. The virus causing 2019-nCov was identified as a β-coronavirus, specifically severe acute respiratory syndrome virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), belonging to the coronavirus family. COVID-19 is characterized by a series of complex clinical symptoms, including fever, pneumonia, dry cough, and shortness of breath. As of 27 July 2022, the World Health Organization announced 570,005,017 confirmed cases and 6,384,128 deaths worldwide. Few infected people were treated, and few treatments are currently available [5,6].

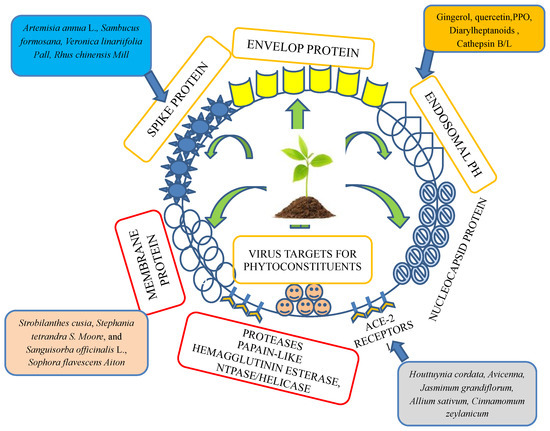

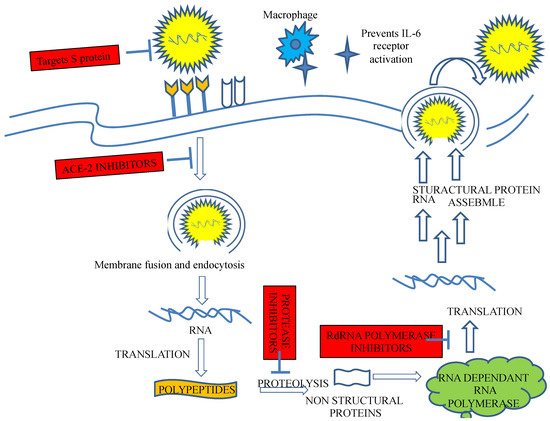

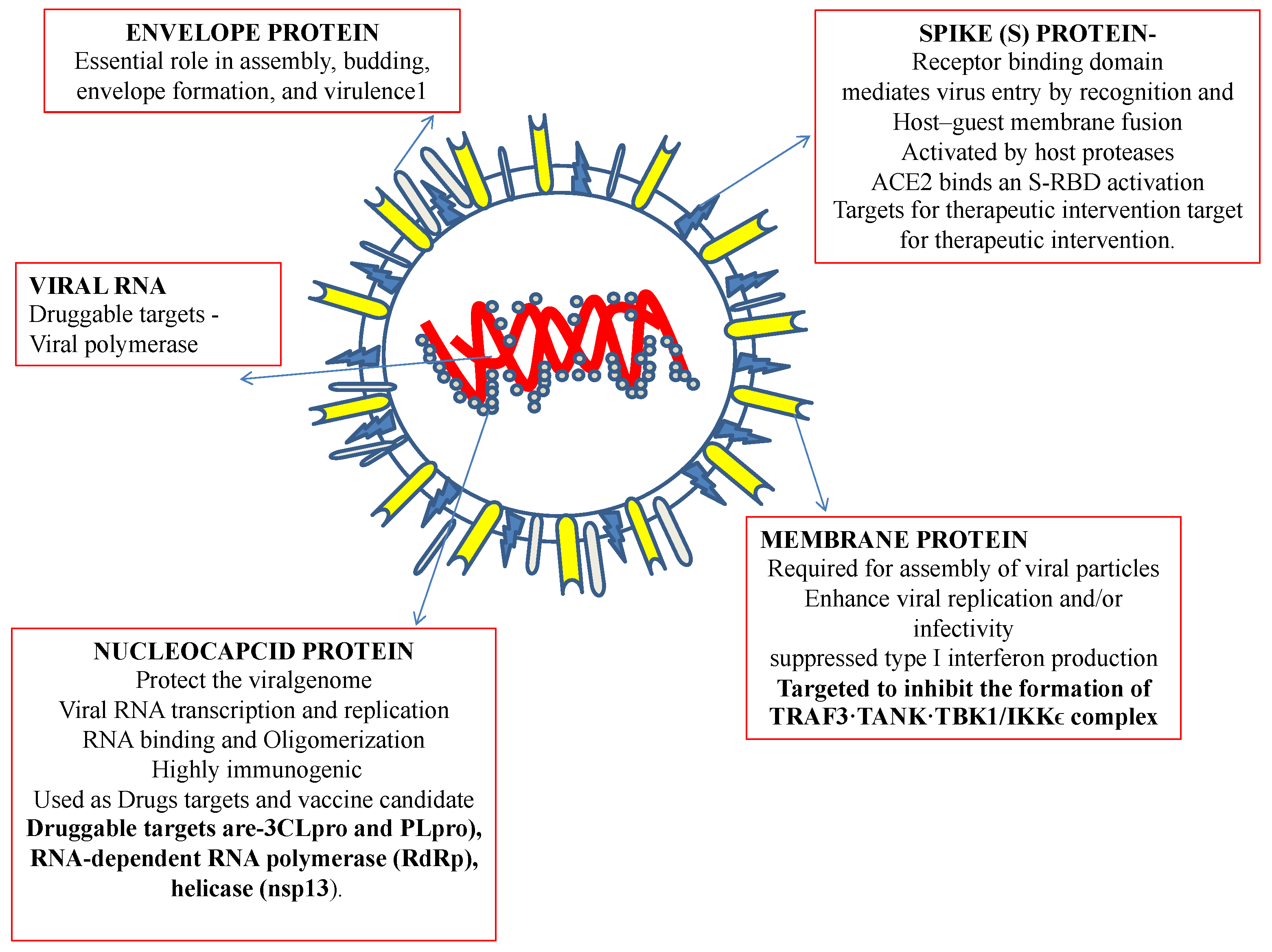

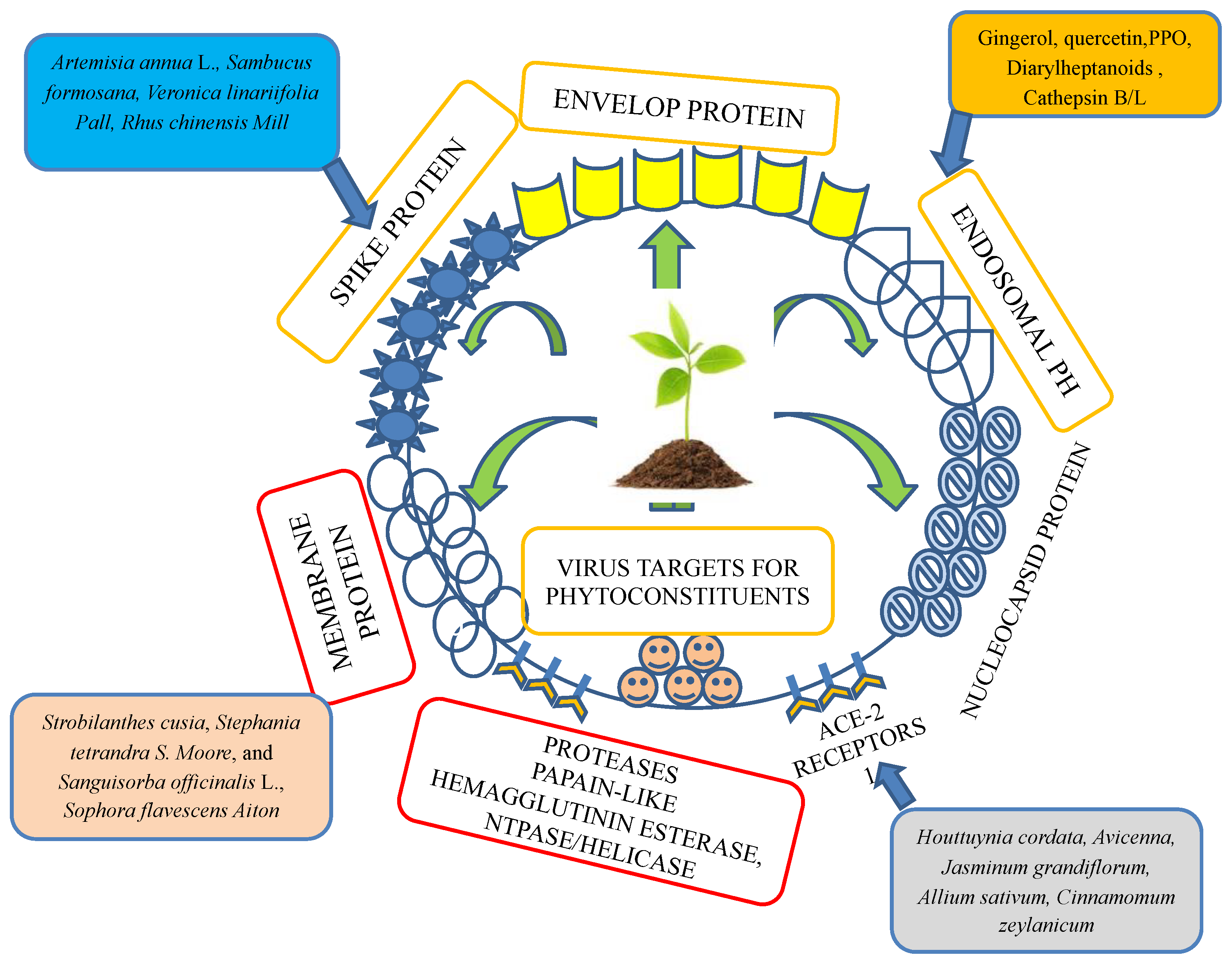

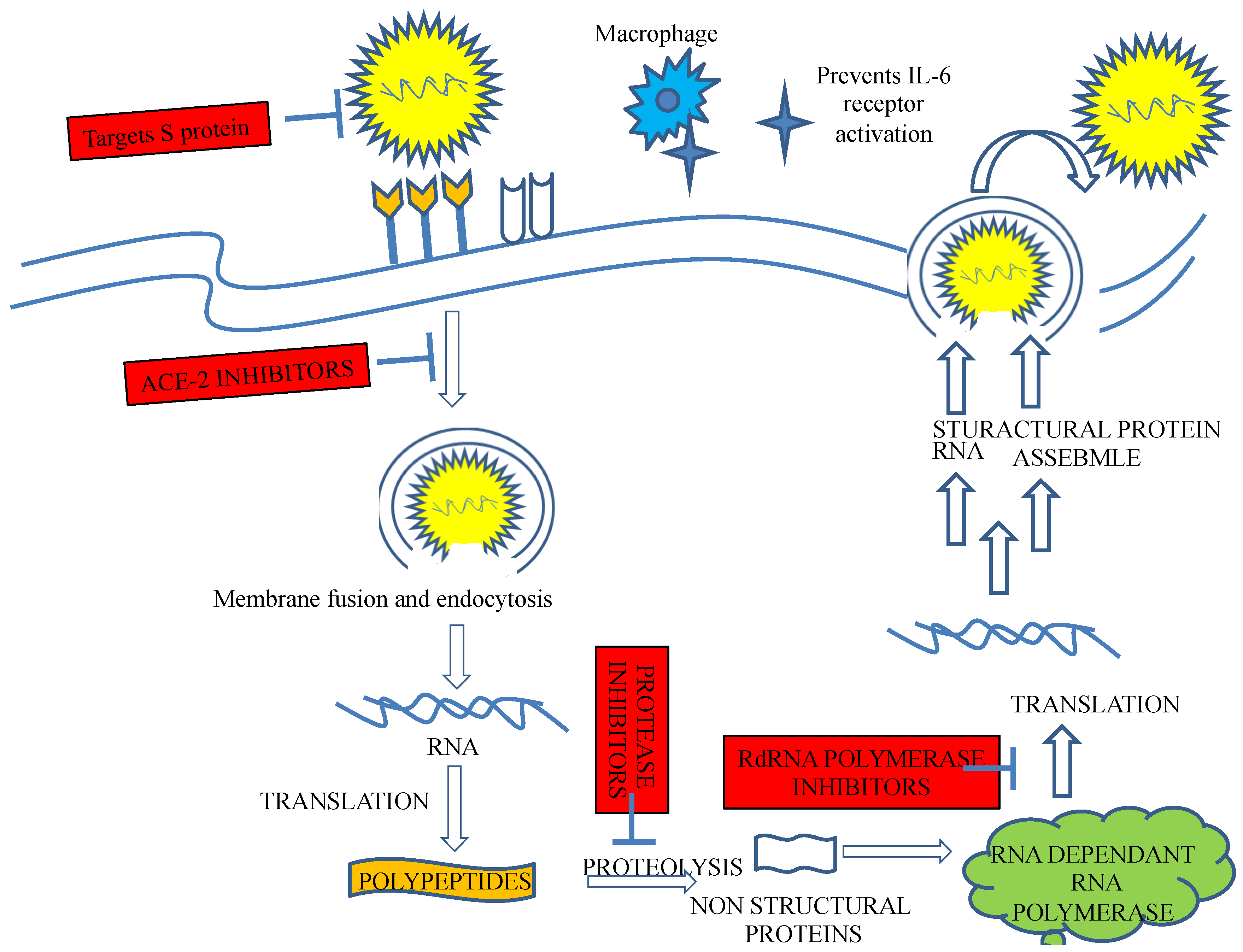

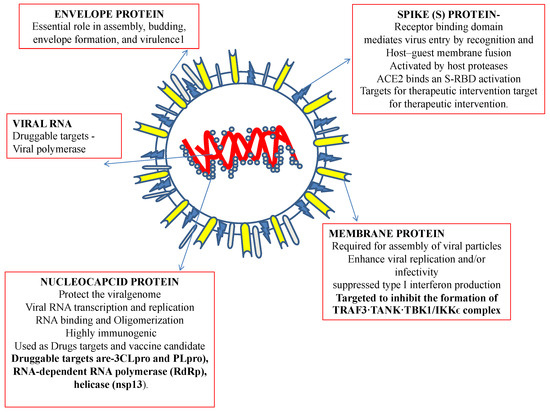

Recently, an immunization program has led to extensive successful outcomes. However, since its emergence, SARS-CoV-2, the virus causing COVID-19, has challenged public health. Recently, an outbreak of COVID-19 has driven the focus toward traditional herbs that are available in different parts of the world. Many therapeutic and diagnostic strategies are available to manage the disease [7,8]. Moreover, studies have reported that SARS-CoV-2 infection can be spread to reptiles, avian species, and mammals [9]. At least 21 families of viruses can cause disease in humans. Of these, five viral families consist of dsDNA, three families comprise nonenveloped viruses (Adenoviridae, Papillomaviridae, and Polyomaviridae), and two families comprise enveloped viruses (Herpesviridae and Poxviridae). One family consists of partially double-stranded (ds) DNA (Hepadnaviridae and enveloped viruses). The members of seven families are single-stranded RNAs, of which three families are characterized as nonenveloped (Astroviridae, Caliciviridae, and Picornaviridae), and the members of four families are enveloped (Retroviridae, Coronaviridae, and Flaviviridae). All nonenveloped families carry icosahedral nucleocapsids and are in negative ssRNA families (Arenaviridae, Bunyavirales, Filoviridae, Orthomyxoviridae, Paramyxoviridae, and Rhabdoviridae) and are enveloped with helical nucleocapsids. One virus, a dsRNA (Reoviridae, which causes hepatitis D), has not been assigned to a family [8,9]. SARS-CoV-2, the virus causing COVID-19 has been identified as an RNA virus with a special spike protein, nucleocapsid protein, membrane protein, envelope protein, and enzymatic proteins, which have been reported to be therapeutic targets that control disease (Figure 1). Secondary metabolites are synthesized by medicinal plants for plant defense. Many therapeutic molecules, such as antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral molecules, have been isolated, purified, characterized, and used in the management of various diseases.

Figure 1.

Structural features of a coronavirus.

To develop medicines against viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, we must focus on these secondary metabolites. Among secondary metabolites, flavonoids have been reported to exhibit antiviral properties [10]. Certain medicinal plants and their respective antiviral potential are described in Table S1. However, thorough guidance for employing several traditional medicines to treat viral infections, including coronaviruses, has not been offered, and the mechanisms of virus action have not yet been fully explained. Notably, more plants or herbs can be considered as therapeutics to increase the supply of medicinal components with activity against viruses. The majority of previous papers and studies have primarily concentrated on specific ethnobotanical drugs, such as traditional Chinese or Indian medicines [11,12,13,14,15], without regard to particular locations or ethnobotanical characteristics. In addition to core wet laboratory experiments, several modern computational methodologies have been adopted for screening and identifying natural compounds that may inhibit viral infection, and the utilization of these approaches to identify fast-acting and more potent vaccines and treatments, including drugs, for COVID-19, increased during the recent pandemic [16,17,18]. Many major scientific databases have been established to help researchers identify possible ethnomedicinal plants or herbs for use as antivirals, including for coronavirus treatments. All previously published reports can be found using the search terms medicinal plants, herb OR herbal, (virus OR viral), and COVID-19/corona in PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science databases, and in Google Scholar, among other online resources. We searched for, found, and thus included studies from these databases in this review. Relevant articles were chosen after being critically assessed for their usefulness; they are described on the basis of the research described, that is, on whether experiments were performed in silico, in vitro, or in vivo [11].

4. Plants as Biological Factories for the Production of Immunotherapeutics: Applications to SARS-CoV

Various immunomodulators, antibodies, interferons, and other therapeutic proteins have been used in the management of various diseases, including virus-induced diseases. Clinical trials for treatments of MERS and SARS-CoV have revealed the role of interferon in reducing the severity of the diseases caused by these coronaviruses.

Plants have been used as biological factories for the production of immunotherapeutics. Various plant-derived vaccines have been assessed in clinical trials, and a few are now marketed as medications and in conjunction with medical devices for the treatment of infectious and chronic diseases. Plant-based vaccines might enable the rapid production of biological products on an industrial scale, which may help meet needs in urgent situations such as the COVID-19 epidemic. Some vaccinations, including those used for cholera, anthrax, Lyme disease, tetanus, rotavirus, canine parvovirus, and plague, were created through direct particle bombardment or biological means [121]. Vaccines for Ebola, tuberculosis, avian flu, and dengue fever are manufactured indirectly or directly via Agrobacterium-mediated gene transfer [121,122].

One study demonstrated that IFN-α inhibited the replication of human- as well as animal-infecting coronaviruses [123]. Another study reported that interferon-α-2a administered with ribavirin increased survival in patients with MERS-CoV [124]. The very first recombinant medicinal protein made from a plant was human interferon, which was created in turnips. Moreover, tobacco plants and potatoes have been used to manufacture human serum albumin for human use. Similarly, tobacco plants were used to generate the first medication (ZMapp) used experimentally to treat Ebola virus infection.

Intravenous gamma globulin (InIg) has also been studied. It was developed in 1970 but gained popularity during the outbreak of SARS in 2003, when it was used extensively in Singapore. However, severe adverse reactions were noticed during its use [125]. Scientists have developed methods for the production of gamma globulin using plant-based molecular farming.

A peptide hormone, thymosin-α-1, has been isolated from thymic tissues, and its immunomodulatory role has been thoroughly explored [126]. Moreover, a synthetic pentapeptide such as thymopentin interacting with the active site in thymopoietin has been found to boost the production of antibodies for hepatitis B vaccines [127]. Plant bioreactors have been successfully applied to the production of thymosin-α-1 [128,129].

Due to the development and expansion of recombinant techniques, plants are now being assessed as potential alternative platforms for the manufacture of recombinant monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). In a study by Sui et al., r-mAb, a recombinant human monoclonal antibody against the S1 domain of the S protein of SARS-CoV was isolated. Moreover, this mAb had been found to efficiently neutralize SARS-CoV [130]. Recent research demonstrated that plant systems for producing mAbs for immunotherapy have been successfully developed [131].

The immunotherapeutics used as the basis for developing SARS-CoV-2 vaccines are thought to be potentially effective and safe. When considering the potential delivery of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in the future, current guidelines for immunizing a host must be used [132].

For the first time, the recombinant production of a fully functional human form of the recently identified cytokine IL-37 in plant cells has been reported, with the cytokine functioning as a fundamental suppressor of innate immunity. Interleukin 37 (IL-37), a recently identified member in the interleukin (IL)-1 class, is essential for controlling innate inflammation and inhibiting acquired immunological responses and, therefore, it shows great potential for treating a variety of autoimmune diseases and inflammatory diseases [133]. Recombinant IL-7 is a potential immune therapeutic that acts to promote the proliferation of naive and memory T cells (CD8+ and CD4+ T cells) and may be effective in managing SARS-CoV-2 viral infection. IL-6 is a key mediator of inflammation in COVID-19, and its receptor antagonist (sarilumab/tocilizumab) and IL-6 inhibitors (clazakizumab/siltuximab/sirukumab) have been described as potential immunotherapeutics to manage SARS-CoV-2 viral infections [134].

The IL-1 inhibitors canakinumab (MoAb anti-IL-1beta) and anakinra (recombinant IL-1 receptor) inhibited IL-1β, a proinflammatory cytokine [135,136]. Other significant immunotherapeutic IL-1 inhibitors, such as canakinumab (MoAb anti-IL-1beta) and anakinra (a recombinant IL-1 receptor), as well as IL-18 inhibitors, have been reported to inhibit IL-1β. Suppression of signaling that triggers the cytokine stimulation of cytokines such as IL-7 and alters Type I IFN levels significantly enhanced the risk of thromboembolism after treatment with JAK/STAT inhibitors such as ruxolitinib, baricitinib, and tofacitinib [137]. Anti-VEGF, complement factor C3, C5, and complement system inhibitors are other classes of immune therapeutics that may be effective against COVID-19. Bamlanivimab antibodies have also been described as being effective against the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2. Tomato plants have been examined for use in the development of SARS vaccines; specifically, their ability to express SARS-CoV nucleocapsid proteins, and their immunogenicity for the development of vaccines have been assessed. A COVID-19 vaccine is now being developed by the Kentucky Bio-Processing Company, a British American Tobacco (BAT) subsidiary, using tobacco plants to express the SARS-CoV-2 protein subunit. The receptor binding protein or the sequence of the S1 protein (full polypeptide) may be the intended vaccine target [72]. Hence, these findings indicate that plants have enormous promise for the low-cost and high production of biologically active viral inhibitors.

4.1. Drugs and Chemicals

In a study conducted by Joffe et al., levamisole, a new synthetic drug given along with ascorbic acid to measles patients, was found to increase the lymphocyte subpopulation. Ascorbic acid was also tested in chick embryo tracheal organ cultures, and after experimentation, resistance to coronavirus was observed [138]. Cyclosporine A is an immunosuppressive drug that significantly enhanced the persistence rates of patients as well as the success of organ transplantation [139]. Cyclosporine A was observed to bind a principle immunophilin, namely, cyclophilin, which binds to the nucleocapsid protein of SARS-CoV. Hence, inhibition of cyclophilin A by cyclosporine A can block the replication of all species of coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV [140]. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine are both antimalarial agents. Experiments have shown that these two treatments can potentially inhibit the replication of several microorganisms, including human coronaviruses. Both drugs render the endosomal pH basic and thus interfere with the glycosylation of the cellular receptor of SARS-CoV, preventing viral infection [141].

Previous studies with SARS-CoV-1 demonstrated that chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine caused a deficit in the glycosylation receptors at the virus surface such that the viruses could not bind to the receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 expressed in the lungs, kidney, heart, and intestine. Since the same mechanism for binding to the cell surface is utilized by SARS-CoV-2, it is believed that chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine can inhibit the attachment of this virus to target cells [142].

Clinical reports suggested that azithromycin given with hydroxychloroquine showed a synergistic effect. Azithromycin has been shown to be active in vitro against Ebola and Zika [143,144]. Promazine is an antipsychotic drug that has shown a potential inhibitory effect on the replication of SARS-CoV. It blocks the interaction of the S protein with the receptor ACE-2 [145]. Recently, surface plasmon resonance (SPR) has been used to identify viral membrane protein ligands and target active ingredients. SPR was performed with senkyunolide, an active constituent of Chuanxiong extract, and the chemokine receptor 4 C-X-C, also known as the CXCR4 receptor protein for the virus. The affinity constant of 2.94 ± 0.36 μM suggested an interaction between senkyunolide I and CXCR4. Further analysis with a Boyden chamber assay revealed that senkyunolide I hindered the movement of cells. Thus, SPR-based screening via a viral membrane protein-targeting active ligand interaction strategy showed that senkyunolide may be effective in managing COVID-19 [145]. In vitro research reported that the ritonavir–lopinavir combination exerted a significant effect against SARS-CoV-2 at the micromolecular IC-50 level. In a different clinical trial study, other combinations, ribavirin, interferon-beta-1b, and lopinavir–ritonavir, were compared to ritonavir–lopinavir treatment alone (control arm), and reported higher safety and potency with decreasing symptoms, shortened duration of viral shielding, and reduced hospital stays in patients with mild-to-moderate hepatitis C. COVID-19 [146]. Umifenovir, a second broad-spectrum antiviral that has been approved in Russia for influenza treatment, was also discovered to have activity against coronaviruses as tested in virus-infected cell culture assays, umifenovir prevented membrane attachment of SARS-CoV-2 to host cells [147]. Umifenovir combined with lopinavir/ritonavir is currently being compared to the combined form of this medicine administered with interferon in a multicentre randomized controlled trial (ChiCTR2000029573) to determine which combination is most effective [148,149].

4.2. Roles of Plant Dietary Supplements

Plants are excellent sources of antioxidants, anti-inflammatory molecules, minerals, vitamins, fats, and proteins that play significant roles in the wellbeing of patients. Because of the potential to lower the risk of infection while simultaneously enhancing the health of COVID-19 patients, special consideration should be given to nutrients that play significant roles in the control of the immune response. Vitamins C, D, and zinc are micronutrients for which the evidence is strongest for their support of the immune system [150].

Nutritional factors that can boost immunity in persons suffering from COVID-19 are listed herein. These elements not only increase immune responses but also act as antioxidants. The roles of water-soluble vitamins such as vitamin B found in legumes (pulses, such as beans), spinach, asparagus, whole grains, potatoes, chili peppers, bananas, and breakfast cereals; vitamin C in citrus fruits involved in collagen synthesis; and antioxidants, have been established. Since these nutrients help to boost immunity, they may be used to combat coronavirus infection. Clinical studies of vitamin C supplementation in pneumonia patients showed that vitamin C clearly reduced the frequency of pneumonia development. Thus, we suggest that vitamin C might reduce the likelihood of respiratory tract infections under certain conditions [151,152].

Vitamin D, which is naturally obtained from mushrooms, is a fat-soluble vitamin that helps to maintain bone integrity and stimulates the growth of different types of cells, including immune cells. Clinical studies have reported that vitamin D deficiency may cause bovine coronavirus infection [153,154].

Fat-soluble vitamin E is found in wheat germ oil, almond, sunflower seeds, pine nuts, avocados, red bell peppers, etc., and plays an important role in oxidative stress. Previously studies with mice reported an increase in the virulence of coxsackievirus B3 due to a deficiency in vitamin E [151,152]. Lipid-soluble vitamin A is an anti-infectivity factor. Many immune diseases have been reported due to a lack of vitamin A; these diseases include measles and HIV. Moreover, the potentiation of bronchitis after coronavirus infection has been reported in a study conducted with chickens fed a diet with a lower vitamin A content and chickens fed a diet with a higher vitamin A content. Long-chain polyunsaturated fatty omega 3 fatty acid has been reported to be important. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids are important facilitators of adaptive immune responses, particularly under inflammatory conditions [151,155,156].

Zinc is an important dietary mineral found in many grains, such as maize, barley, sunflowers, vegetables, and fruit, and it is used for developing and maintaining immune cells for both adaptive immunity and innate immunity. Zinc deficiency results in the malfunctioning of both cell-mediated and humoral immunity and increases vulnerability to infectious diseases. The combination of zinc with pyrithione has been shown to inhibit the replication of COVID-19 [136,157,158]. Studies have shown that dietary deficiency of selenium produces alterations in the viral genome under oxidative stress that result in the potentiation of viral pathogenesis. Therefore, selenium intake may be a good choice for the control of novel infectious coronaviruses [159]. Iron deficiency has been reported to be a risk factor in recurrent acute respiratory tract infections. Nutritional factors that can help boost immunity in persons suffering from COVID-19 are listed herein. These elements not only increase immune responses but also act as antioxidants. Moreover, nutritional components, such as vitamins, can control not only pathological processes but also many physiological processes and directly affect the epigenome [160,161]. The number of reports on botanical medicines and dietary supplements as sources of possible therapeutic agents for SARS-CoV-2 medication development is increasing [162]. Research is required to determine the mechanisms of action and efficacy of phytotherapeutic interventions when used as adjunctive drugs during the onset or recovery of SARS-CoV-2 exposure, with or without a vaccine. Moreover, we have good reason to expressly caution against the promotion of treatments without supporting data and against grossly deceptive or plainly incorrect claims [150].

5. Conclusions

The medicinal plant resources that may be effective in the treatment of COVID-19 are claimed on the basis of the history of using these herbs in the treatment of MERS and SARS. In addition, other medicinal herbs have been identified worldwide that may play a beneficial role in combatting COVID-19. As the virus continues to spread at a very high rate, the main focus is the development of a therapy that can prevent the entry of the virus into the host. These herbs may contribute to this inhibitory effect by increasing the effectiveness of the host immune response. Since some countries have developed vaccines for the disease, the cost of which may be high, we must develop alternate inexpensive sources of drugs to treat COVID-19 patients in developing countries. To this end, medicinal plants can play a significant role. New therapy options for SARS-CoV-2 are required, even though different vaccines are being produced, because plant-derived chemicals show a wide spectrum of therapeutic actions, particularly against SARS-CoV-2, making them advantageous on SARS-CoV-2 targets. Plants such as Glycyrrhiza glabra, Andrographis paniculata, Azadirachta indica, Curcuma longa, Ocimum sanctum, Withania somnifera, Allium sativum, Zingiber officinale, Moringa oleifera, Tinospora cordifolia, and Nigella sativa have been reported to exhibit significant antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2. Moreover, the in vitro activity of many plants or derived molecules including umifenovir, hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine, glycyrrhizin, turmeric (Curcuma longa) rhizomes, mustard (Brassica nigra), and wall rocket (Diplotaxis erucoides subsp. erucoides), were tested effectively against corona viruses. The potential for using the majority of plant-derived bioactive compounds is increased because clinical studies of other infectious diseases have confirmed their effectiveness and safety in the human body. The molecules must be evaluated specifically against SARS-CoV-2, as the majority of the trials chosen for this study did not specifically assess how direct chemical treatment affected the virus. Therefore, when prescribing natural compounds, extreme caution is needed. Thus, future studies must start, and they must intervene in a suitable dosage form.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded from https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms232113564/s1.

Funding

This research was funded by the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education, Saudi Arabia, under project number QU-IF-2-2-2-26338.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The author extends his appreciation to the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education, Saudi Arabia, for funding this research work through project number (QU-IF-2-2-2-26338). The authors also thank Qassim University for its technical support. The researcher would like to thank the Deanship of Scientific Research, Qassim University, for the support of this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Sarid, R.; Gao, S.-J. Viruses and human cancer: From detection to causality. Cancer Lett. 2011, 305, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaacs, S.R.; Foskett, D.B.; Maxwell, A.J.; Ward, E.J.; Faulkner, C.L.; Luo, J.Y.; Rawlinson, W.D.; Craig, M.E.; Kim, K.W. Viruses and type 1 diabetes: From enteroviruses to the virome. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Readhead, B.; Haure-Mirande, J.-V.; Funk, C.C.; Richards, M.A.; Shannon, P.; Haroutunian, V.; Sano, M.; Liang, W.S.; Beckmann, N.D.; Price, N.D.; et al. Multiscale analysis of independent Alzheimer’s cohorts finds disruption of molecular, genetic, and clinical networks by human herpesvirus. Neuron 2018, 99, 64–82.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paraskevis, D.; Kostaki, E.G.; Magiorkinis, G.; Panayiotakopoulos, G.; Sourvinos, G.; Tsiodras, S. Full-genome evolutionary analysis of the novel Corona virus (2019-ncov) rejects the hypothesis of emergence as a result of a recent recombination event. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2020, 79, 104212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, M.; Berhanu, G.; Desalegn, C.; Kandi, V. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2): An Update. Cureus 2020, 12, e7423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 21 September 2022).

- Christou, L. The global burden of bacterial and viral zoonotic infections. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2011, 17, 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R. Viral diseases and antiviral activity of some medicinal plants with special reference to ajmer. J. Antivir. Antiretrovir. 2019, 11, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Guzzi, P.H.; Mercatelli, D.; Ceraolo, C.; Giorgi, F.M. Master regulator analysis of the SARS-CoV-2/human Interactome. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerriero, G.; Berni, R.; Muñoz-Sanchez, J.; Apone, F.; Abdel-Salam, E.; Qahtan, A.; Alatar, A.; Cantini, C.; Cai, G.; Hausman, J.-F.; et al. Production of plant secondary metabolites: Examples, tips and suggestions for Biotechnologists. Genes 2018, 9, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remali, J.; Aizat, W.M. A review on plant bioactive compounds and their modes of action against coronavirus infection. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 11, 589044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudani, T.; Saraogi, A. Use of herbal medicines on coronavirus. Acta Sci. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 4, 61–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, K.; Kohli, S.K.; Kaur, R.; Bhardwaj, A.; Bhardwaj, V.; Ohri, P.; Sharma, A.; Ahmad, A.; Bhardwaj, R.; Ahmad, P. Herbal Immune-boosters: Substantial warriors of pandemic COVID-19 battle. Phytomedicine 2021, 85, 153361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, C.-Q. Traditional Chinese medicine is a resource for drug discovery against 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2). J. Integr. Med. 2020, 18, 87–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vellingiri, B.; Jayaramayya, K.; Iyer, M.; Narayanasamy, A.; Govindasamy, V.; Giridharan, B.; Ganesan, S.; Venugopal, A.; Venkatesan, D.; Ganesan, H.; et al. COVID-19: A promising cure for the global panic. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 725, 138277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, K.; Kumar, V. Artificial intelligence-driven drug repurposing and structural biology for SARS-CoV-2. Curr. Res. Pharmacol. Drug Discov. 2021, 2, 100042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, H.; Shi, L.; Berkenpas, J.W.; Dao, F.-Y.; Zulfiqar, H.; Ding, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, L.; Cao, R. Application of artificial intelligence and machine learning for COVID-19 drug discovery and vaccine design. Brief. Bioinform. 2021, 22, bbab320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkaeed, E.B.; Youssef, F.S.; Eissa, I.H.; Elkady, H.; Alsfouk, A.A.; Ashour, M.L.; El Hassab, M.A.; Abou-Seri, S.M.; Metwaly, A.M. Multi-Step In Silico Discovery of Natural Drugs against COVID-19 Targeting Main Protease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Human Coronavirus Types. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/types.html (accessed on 22 September 2022).

- Chan, J.F.-W.; Kok, K.-H.; Zhu, Z.; Chu, H.; To, K.K.-W.; Yuan, S.; Yuen, K.-Y. Genomic characterization of the 2019 novel human-pathogenic coronavirus isolated from a patient with atypical pneumonia after visiting Wuhan. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Xia, L.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, Q. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science 2020, 367, 1444–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, G.A.; Sacco, O.; Mancino, E.; Cristiani, L.; Midulla, F. Differences and similarities between SARS-COV and SARS-CoV-2: Spike receptor-binding domain recognition and host cell infection with support of cellular serine proteases. Infection 2020, 48, 665–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutard, B.; Valle, C.; de Lamballerie, X.; Canard, B.; Seidah, N.G.; Decroly, E. The spike glycoprotein of the new coronavirus 2019-ncov contains a furin-like cleavage site absent in cov of the same clade. Antivir. Res. 2020, 176, 104742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabaan, A.A.; Al-Ahmed, S.H.; Haque, S.; Sah, R.; Tiwari, R.; Malik, Y.S.; Dhama, K.; Yatoo, M.I.; Bonilla-Aldana, D.K.; Rodriguez-Morales, A.J. SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-COV: A comparative overview. Infez. Med. 2020, 28, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Cao, D.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, J.; Qi, J.; Wang, Q.; Lu, G.; Wu, Y.; Yan, J.; Shi, Y.; et al. Cryo-EM structures of MERS-COV and SARS-COV spike glycoproteins reveal the dynamic receptor binding domains. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, G.; Kerimi, A. Testing of natural products in clinical trials targeting the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) viral spike protein-angiotensin converting enzyme-2 (ACE2) interaction. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020, 178, 114123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maj, M.; Fake, G.M.; Walker, J.H.; Saltzman, R.; Howard, J.A. Oral Administration of Coronavirus Spike Protein Provides Protection to Newborn Pigs When Challenged with PEDV. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeman, D.; Fielding, B.C. Coronavirus envelope protein: Current knowledge. Virol. J. 2019, 16, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Guardeño, J.M.; Nieto-Torres, J.L.; DeDiego, M.L.; Regla-Nava, J.A.; Fernandez-Delgado, R.; Castaño-Rodriguez, C.; Enjuanes, L. The PDZ-binding motif of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus envelope protein is a determinant of viral pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepley-McTaggart, A.; Sagum, C.A.; Oliva, I.; Rybakovsky, E.; DiGuilio, K.; Liang, J.; Bedford, M.T.; Cassel, J.; Sudol, M.; Mullin, J.M.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 envelope (E) protein interacts with PDZ-domain-2 of host tight junction protein zo1. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, A.L.; Larson, B.J.; Hogue, B.G. A conserved domain in the coronavirus membrane protein tail is important for virus assembly. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 11418–11428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wong, G.; Lu, G.; Yan, J.; Gao, G.F. MERS-COV spike protein: Targets for vaccines and therapeutics. Antivir. Res. 2016, 133, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, M.; Benvenuto, D.; Giovanetti, M.; Angeletti, S.; Ciccozzi, M.; Pascarella, S. SARS-CoV-2 envelope and membrane proteins: Structural differences linked to virus characteristics? BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 4389089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.-K.; Hou, M.-H.; Chang, C.-F.; Hsiao, C.-D.; Huang, T.-H. The SARS coronavirus nucleocapsid protein—Forms and functions. Antivir. Res. 2014, 103, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-K.; Jeyachandran, S.; Hu, N.-J.; Liu, C.-L.; Lin, S.-Y.; Wang, Y.-S.; Chang, Y.-M.; Hou, M.-H. Structure-based virtual screening and experimental validation of the discovery of inhibitors targeted towards the human coronavirus nucleocapsid protein. Mol. BioSystems 2016, 12, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindner, H.A.; Fotouhi-Ardakani, N.; Lytvyn, V.; Lachance, P.; Sulea, T.; Ménard, R. The papain-like protease from the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus is a deubiquitinating enzyme. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 15199–15208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barretto, N.; Jukneliene, D.; Ratia, K.; Chen, Z.; Mesecar, A.D.; Baker, S.C. The papain-like protease of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus has deubiquitinating activity. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 15189–15198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadler, K.; Ha, H.R.; Ciminale, V.; Spirli, C.; Saletti, G.; Schiavon, M.; Bruttomesso, D.; Bigler, L.; Follath, F.; Pettenazzo, A.; et al. Amiodarone alters late endosomes and inhibits SARS coronavirus infection at a post-endosomal level. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2008, 39, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, R.B.; Dantas, W.M.; do Nascimento, J.C.F.; da Silva, M.V.; de Oliveira, R.N.; Pena, L.J. In Vitro and In Vivo Models for Studying SARS-CoV-2, the Etiological Agent Responsible for COVID-19 Pandemic. Viruses 2021, 13, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guijarro-Real, C.; Plazas, M.; Rodríguez-Burruezo, A.; Prohens, J.; Fita, A. Potential In Vitro Inhibition of Selected Plant Extracts against SARS-CoV-2 Chymotripsin-Like Protease (3CLPro) Activity. Foods 2021, 10, 1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, D.Y.; Kim, W.; Nam, S.M.; Yoo, M.; Lee, S.; Yoon, Y.S.; Won, M.-H.; Hwang, I.K.; Choi, J.H. Neuroprotective effects of Z-ajoene, an organosulfur compound derived from oil-macerated garlic, in the gerbil hippocampal CA1 region after transient forebrain ischemia. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2014, 72, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankri, S.; Mirelman, D. Antimicrobial properties of allicin from garlic. Microbes Infect. 1999, 1, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Singh, J.; Singh, S.; Singh, B.R. Medicinal values of garlic (Allium sativum L.) in human life: An overview. Greener J. Agric. Sci. 2014, 4, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, C.E.; Liu, R.; Atanasov, A.G.; Schmidtke, M.; Dirsch, V.M.; Rollinger, J.M. Antiviral and anti-proliferative in vitro activities of piperamides from black pepper. Planta Med. 2016, 82, S1–S381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, A.B.; Shoman, S.A.; Dina, N.; Alfarouk, O.R. Antiviral activity and mode of action of Dianthus caryophyllus L. and Lupinus termes L. seed extracts against in vitro herpes simplex and hepatitis A viruses infection. J. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2010, 2, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Mounce, B.C.; Cesaro, T.; Carrau, L.; Vallet, T.; Vignuzzi, M. Curcumin inhibits zika and chikungunya virus infection by inhibiting cell binding. Antivir. Res. 2017, 142, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra Manivannan, A.; Malaisamy, A.; Eswaran, M.; Meyyazhagan, A.; Arumugam, V.A.; Rengasamy, K.R.; Balasubramanian, B.; Liu, W.-C. Evaluation of clove phytochemicals as potential antiviral drug candidates targeting SARS-CoV-2 main protease: Computational Docking, molecular dynamics simulation, and pharmacokinetic profiling. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 918101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wińska, K.; Mączka, W.; Łyczko, J.; Grabarczyk, M.; Czubaszek, A.; Szumny, A. Essential oils as antimicrobial agents—Myth or real alternative? Molecules 2019, 24, 2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan, I.E.; Senol Deniz, F.S. Natural products as potential leads against coronaviruses: Could they be encouraging structural models against SARS-CoV-2? Nat. Prod. Bioprospecting 2020, 10, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loizzo, M.R.; Saab, A.M.; Tundis, R.; Statti, G.A.; Menichini, F.; Lampronti, I.; Gambari, R.; Cinatl, J.; Doerr, H.W. Phytochemical analysis andin vitro antiviral activities of the essential oils of seven Lebanon species. Chem. Biodivers. 2008, 5, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaerunnisa, S.; Kurniawan, H.; Awaluddin, R.; Suhartati, S.; Soetjipto, S. Potential Inhibitor of COVID-19 Main Protease (Mpro) from Several Medicinal Plant Compounds by Molecular Docking Study. Preprints 2020, 2020030226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.; Wu, S.; Chen, J.; Li, C.; Hsiang, C. Emodin blocks the SARS coronavirus spike protein and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 interaction. Antivir. Res. 2007, 74, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, B.B.; Van Kuiken, M.E.; Iyer, L.H.; Harikumar, K.B.; Sung, B. Molecular targets of nutraceuticals derived from dietary spices: Potential role in suppression of inflammation and tumorigenesis. Exp. Biol. Med. 2009, 234, 825–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansouri, S.; Choudhary, G.; Sarzala, P.M.; Ratner, L.; Hudak, K.A. Suppression of human T-cell leukemia virus I gene expression by pokeweed antiviral protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 31453–31462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaladhar, D.; Nandikolla, S.K. Antimicrobial studies, Biochemical and image analysis in Mirabilis lalapa Linn. Int. J. Farm. Tech. 2010, 2, 683–693. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, J. Green tea: A potential alternative anti-infectious agent catechins and viral infections. Adv. Anthropol. 2013, 3, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jin, S. Therapeutic potential of natural catechins in antiviral activity. JSM Biotechnol. Biomed. Eng. 2013, 1, 1002. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.-Y.; Eo, E.-Y.; Park, H.; Kim, Y.-C.; Park, S.; Shin, H.-J.; Kim, K. Medicinal herbal extracts of sophorae radix ACANTHOPANACIS cortex sanguisorbae radix and Torilis fructus inhibit coronavirus replication in vitro. Antivir. Ther. 2010, 15, 697–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-Y.; Shin, H.-S.; Park, H.; Kim, Y.-C.; Yun, Y.G.; Park, S.; Shin, H.-J.; Kim, K. In vitro inhibition of coronavirus replications by the traditionally used medicinal herbal extracts, CIMICIFUGA rhizoma, meliae cortex, coptidis rhizoma, and Phellodendron Cortex. J. Clin. Virol. 2008, 41, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, F.-R.; Yen, C.-T.; EI-Shazly, M.; Lin, W.-H.; Yen, M.-H.; Lin, K.-H.; Wu, Y.-C. Anti-human coronavirus (anti-hcov) triterpenoids from the leaves of Euphorbia neriifolia. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2012, 7, 1415–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-J.; Michaelis, M.; Hsu, H.-K.; Tsai, C.-C.; Yang, K.D.; Wu, Y.-C.; Cinatl, J.; Doerr, H.W. Toona sinensis roem tender leaf extract inhibits SARS coronavirus replication. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 120, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.K.; Curtis-Long, M.J.; Lee, K.H.; Kim, D.W.; Ryu, H.W.; Yuk, H.J.; Park, K.H. Geranylated flavonoids displaying SARS-COV papain-like protease inhibition from the fruits of paulownia tomentosa. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 3051–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, C.; Eisenhut, M.; Krausse, R.; Ragazzi, E.; Pellati, D.; Armanini, D.; Bielenberg, J. Antiviral effects ofglycyrrhiza species. Phytother. Res. 2008, 22, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asl, M.N.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Review of pharmacological effects of Glycyrrhiza sp. and its bioactive compounds. Phytother. Res. 2008, 22, 709–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.K.; Das, V.; Gulati, A.K.; Singh, V.P. Deglycyrrhizinated liquorice in aphthous ulcers. J. Assoc. Phys. India 1989, 37, 647. [Google Scholar]

- Krausse, R. In vitro anti-helicobacter pylori activity of extractum liquiritiae, glycyrrhizin and its metabolites. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2004, 54, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Chan, K.H.; Jiang, Y.; Kao, R.Y.T.; Lu, H.T.; Fan, K.W.; Cheng, V.C.C.; Tsui, W.H.W.; Hung, I.F.N.; Lee, T.S.W. In vitro susceptibility of 10 clinical isolates of SARS coronavirus to selected antiviral compounds. J. Clin. Virol. 2004, 31, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cinatl, J.; Morgenstern, B.; Bauer, G.; Chandra, P.; Rabenau, H.; Doerr, H.W. Glycyrrhizin, an active component of liquorice roots, and replication of SARS-associated coronavirus. Lancet 2003, 361, 2045–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massi, A.; Bortolini, O.; Ragno, D.; Bernardi, T.; Sacchetti, G.; Tacchini, M.; De Risi, C. Research progress in the modification of quercetin leading to anticancer agents. Molecules 2017, 22, 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, J.; Luo, C.; Liu, H.; Xu, W.; Chen, G.; Liew, O.W.; Zhu, W.; Puah, C.M.; Shen, X.; et al. Binding interaction of quercetin-3-β-galactoside and its synthetic derivatives with SARS-CoV 3clpro: Structure–activity relationship studies reveal salient pharmacophore features. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2006, 14, 8295–8306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.-C.; Shyur, L.-F.; Jan, J.-T.; Liang, P.-H.; Kuo, C.-J.; Arulselvan, P.; Wu, J.-B.; Kuo, S.-C.; Yang, N.-S. Traditional Chinese medicine herbal extracts of Cibotium barometz, Gentiana scabra, Dioscorea batatas, Cassia tora, and Taxillus chinensis inhibit SARS-COV replication. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2011, 1, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brendler, T.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Bauer, R.; Gafner, S.; Hardy, M.L.; Heinrich, M.; Hosseinzadeh, H.; Izzo, A.A.; Michaelis, M.; Nassiri-Asl, M.; et al. Botanical Drugs and supplements affecting the immune response in the time of COVID-19: Implications for research and clinical practice. Phytother. Res. 2020, 35, 3013–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.-W.; Ng, L.-T.; Chiang, L.-C.; Lin, C.-C. Antiviral effects of SAIKOSAPONINS on human coronavirus 229E in vitro. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2006, 33, 612–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Dong, X.; Yin, X.; Wang, W.; You, L.; Ni, J. Radix bupleuri: A review of traditional uses, botany, phytochemistry, pharmacology, and toxicology. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 7597596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Saber Batiha, G.; Beshbishy, A.M.; El-Mleeh, A.; Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Devkota, H.P. Traditional uses, bioactive chemical constituents, and pharmacological and toxicological activities of Glycyrrhiza glabra L. (fabaceae). Biomolecules 2020, 10, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Islam, M.S.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, X. Traditional Chinese medicine in the treatment of patients infected with 2019-new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2): A review and perspective. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 1708–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Ye, F.; Sun, Q.; Liang, H.; Li, C.; Li, S.; Lu, R.; Huang, B.; Tan, W.; Lai, L. Scutellaria baicalensis extract and Baicalein inhibit replication of SARS-COV-2 and its 3c-like protease in vitro. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2021, 36, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, K.-M.; Lee, K.-M.; Koon, C.-M.; Cheung, C.S.-F.; Lau, C.-P.; Ho, H.-M.; Lee, M.Y.-H.; Au, S.W.-N.; Cheng, C.H.-K.; Lau, C.B.-S.; et al. Immunomodulatory and anti-SARS activities of Houttuynia Cordata. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 118, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, S.-S.; Jia, X.-L.; Song, P.; Cheng, Y.-A.; Zhang, X.; Sun, M.-Z.; Liu, E.-Q. Inhibitory effect of emodin and astragalus polysaccharideon the replication of HBV. World J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 15, 5669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethu, S.; Shetty, R.; Ghosh, A.; Honavar, S.G.; Khamar, P. Therapeutic opportunities to manage COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2 infection: Present and future. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 68, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-Y.; Jae Jeong, H.; Hoon Kim, J.; Min Kim, Y.; Park, S.-J.; Kim, D.; Hun Park, K.; Song Lee, W.; Bae Ryu, Y. Diarylheptanoids from alnus japonica inhibit papain-like protease of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2012, 35, 2036–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capell, T.; Twyman, R.M.; Armario-Najera, V.; Ma, J.K.-C.; Schillberg, S.; Christou, P. Potential applications of plant biotechnology against SARS-CoV-2. Trends Plant Sci. 2020, 25, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, M.; Appendino, G.; Efferth, T.; Fürst, R.; Izzo, A.A.; Kayser, O.; Pezzuto, J.M.; Viljoen, A. Best practice in research—Overcoming common challenges in phytopharmacological research. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 246, 112230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patten, G.S.; Abeywardena, M.Y.; Bennett, L.E. Inhibition of angiotensin converting enzyme, angiotensin II receptor blocking, and blood pressure lowering bioactivity across plant families. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 56, 181–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, S.; Yoshiya, T.; Yoshizawa-Kumagaye, K.; Sugiyama, T. Nicotianamine is a novel angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 inhibitor in soybean. Biomed. Res. 2015, 36, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddesha, J.M.; D’Souza, C.; Vishwanath, B.S. Inhibition of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) by medicinal plants exhibiting antihypertensive activity. In Recent Progress in Medicinal Plants; Studium Press LLC: New Delhi, India, 2010; Volume 29. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.-C.; Hsu, F.-L.; Tsai, J.-C.; Chan, P.; Liu, J.Y.-H.; Thomas, G.N.; Tomlinson, B.; Lo, M.-Y.; Lin, J.-Y. Antihypertensive effects of tannins isolated from traditional Chinese herbs as non-specific inhibitors of angiontensin converting enzyme. Life Sci. 2003, 73, 1543–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loizzo, M.R.; Saab, A.M.; Tundis, R.; Menichini, F.; Bonesi, M.; Piccolo, V.; Statti, G.A.; de Cindio, B.; Houghton, P.J.; Menichini, F. In vitro inhibitory activities of plants used in Lebanon traditional medicine against angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) and digestive enzymes related to diabetes. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 119, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoonratana, T.; Madaka, F. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitory activity of Senna garrettiana active compounds: Potential markers for standardized herbal medicines. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2018, 14, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Hou, Y.; Shen, J.; Huang, Y.; Martin, W.; Cheng, F. Network-based drug repurposing for Novel Coronavirus 2019-ncov/SARS-CoV-2. Cell Discov. 2020, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, J.-R.; Lin, C.-S.; Lai, H.-C.; Lin, Y.-P.; Wang, C.-Y.; Tsai, Y.-C.; Wu, K.-C.; Huang, S.-H.; Lin, C.-W. Antiviral activity of Sambucus formosananakai ethanol extract and related phenolic acid constituents against human coronavirus NL63. Virus Res. 2019, 273, 197767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, G.; Gosalia, D.N.; Rennekamp, A.J.; Reeves, J.D.; Diamond, S.L.; Bates, P. Inhibitors of cathepsin L prevent severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus entry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 11876–11881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, I.-C.; Bosch, B.J.; Li, F.; Li, W.; Lee, K.H.; Ghiran, S.; Vasilieva, N.; Dermody, T.S.; Harrison, S.C.; Dormitzer, P.R.; et al. SARS coronavirus, but not human coronavirus NL63, utilizes cathepsin L to infect ace2-expressing cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 3198–3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-Q.; Du, Q.-S.; Zhao, K.; Li, A.-X.; Wei, D.-Q.; Chou, K.-C. Virtual screening for finding natural inhibitor against cathepsin-L for SARS therapy. Amino Acids 2007, 33, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouffouk, C.; Mouffouk, S.; Mouffouk, S.; Hambaba, L.; Haba, H. Flavonols as potential antiviral drugs targeting SARS-CoV-2 proteases (3CLpro and PLpro), Spike protein, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (rdrp) and angiotensin-converting enzyme II receptor (ACE2). Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 891, 173759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidu, S.A.; Mustafa, G.; Clemens, R.A.; Naidu, A.S. Plant-derived natural non-nucleoside analog inhibitors (nnais) against RNA-dependent RNA polymerase complex (NSP7/NSP8/NSP12) of SARS-CoV-2. J. Diet. Suppl. 2021, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, X.; Sun, H.; Wu, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Hong, B. Identifying small-molecule inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase by establishing a fluorometric assay. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 844749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, A.; Le, N.T.-T.; Selisko, B.; Eydoux, C.; Alvarez, K.; Guillemot, J.-C.; Decroly, E.; Peersen, O.; Ferron, F.; Canard, B. Remdesivir and SARS-CoV-2: Structural requirements at both NSP12 RDRP and NSP14 exonuclease active-sites. Antivir. Res. 2020, 178, 104793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bibi, S.; Khan, M.S.; El-Kafrawy, S.A.; Alandijany, T.A.; El-Daly, M.M.; Yousafi, Q.; Fatima, D.; Faizo, A.A.; Bajrai, L.H.; Azhar, E.I. Virtual screening and molecular dynamics simulation analysis of Forsythoside A as a plant-derived inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 3clpro. Saudi Pharm. J. 2022, 30, 979–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustaqil, M.; Ollivier, E.; Chiu, H.-P.; Van Tol, S.; Rudolffi-Soto, P.; Stevens, C.; Bhumkar, A.; Hunter, D.J.; Freiberg, A.N.; Jacques, D.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 proteases PLpro and 3CLpro cleave IRF3 and critical modulators of inflammatory pathways (NLRP12 and TAB1): Implications for disease presentation across species. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2021, 10, 178–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, S.-Y.; Siu, K.-L.; Lin, H.; Yeung, M.L.; Jin, D.-Y. SARS-CoV-2 main protease suppresses type I interferon production by preventing nuclear translocation of phosphorylated IRF3. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 17, 1547–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derosa, G.; Maffioli, P.; D’Angelo, A.; Di Pierro, F. A role for quercetin in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Phytother. Res. 2020, 35, 1230–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Ratia, K.; Cooper, L.; Kong, D.; Lee, H.; Kwon, Y.; Li, Y.; Alqarni, S.; Huang, F.; Dubrovskyi, O.; et al. Potent, novel SARS-CoV-2 plpro inhibitors block viral replication in monkey and human cell cultures. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 65, 2940–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Sk, M.F.; Sonawane, A.; Kar, P.; Sadhukhan, S. Plant-derived natural polyphenols as potential antiviral drugs against SARS-CoV-2 via rna-dependent RNA polymerase (rdrp) inhibition: An in-silico analysis. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 39, 6249–6264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swargiary, A.; Mahmud, S.; Saleh, M.A. Screening of phytochemicals as potent inhibitor of 3-chymotrypsin and papain-like proteases of SARS-CoV2: An in silico approach to combat COVID-19. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 40, 2067–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zrieq, R.; Ahmad, I.; Snoussi, M.; Noumi, E.; Iriti, M.; Algahtani, F.D.; Patel, H.; Saeed, M.; Tasleem, M.; Sulaiman, S.; et al. Tomatidine and patchouli alcohol as inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 enzymes (3CLpro, PLpro and NSP15) by molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, Y.; Maciorowski, D.; Zak, S.E.; Jones, K.A.; Kathayat, R.S.; Azizi, S.-A.; Mathur, R.; Pearce, C.M.; Ilc, D.J.; Husein, H.; et al. Bisindolylmaleimide IX: A novel anti-SARS-cov2 agent targeting viral main protease 3CLpro demonstrated by virtual screening pipeline and in-vitro validation assays. Methods 2021, 195, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D.S.; Ho, J.; Wills, S.; Kawall, A.; Sharma, A.; Chavada, K.; Ebert, M.C.; Evoli, S.; Singh, A.; Rayalam, S.; et al. Aloin isoforms (A and B) selectively inhibits proteolytic and deubiquitinating activity of papain like protease (PLpro) of SARS-CoV-2 in vitro. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.-H.; Wu, K.-L.; Zhang, X.; Deng, S.-Q.; Peng, B. In silico screening of Chinese herbal medicines with the potential to directly inhibit 2019 novel coronavirus. J. Integr. Med. 2020, 18, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawan, M.M.; Halder, S.K.; Hasan, M.A. Luteolin and abyssinone II as potential inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2: An in silico molecular modeling approach in battling the COVID-19 outbreak. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2021, 45, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shree, P.; Mishra, P.; Selvaraj, C.; Singh, S.K.; Chaube, R.; Garg, N.; Tripathi, Y.B. Targeting COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) main protease through active phytochemicals of ayurvedic medicinal plants—Withania somnifera (ashwagandha), Tinospora cordifolia (giloy) and Ocimum sanctum (tulsi)—A molecular docking study. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 40, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyebi, G.A.; Ogunyemi, O.M.; Ibrahim, I.M.; Afolabi, S.O.; Adebayo, J.O. Dual targeting of cytokine storm and viral replication in COVID-19 by plant-derived steroidal pregnanes: An in silico perspective. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 134, 104406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balkrishna, A.; Pokhrel, S.; Singh, J.; Varshney, A. Withanone from Withania somnifera may inhibit novel coronavirus (COVID-19) entry by disrupting interactions between viral S-protein receptor binding domain and host ACE2 receptor. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2020, 15, 1111–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, D.; Sanap, G.; Shenoy, S.; Kalyane, D.; Kalia, K.; Tekade, R.K. Artificial Intelligence in drug discovery and development. Drug Discov. Today 2021, 26, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floresta, G.; Zagni, C.; Gentile, D.; Patamia, V.; Rescifina, A. Artificial Intelligence Technologies for COVID-19 de Novo Drug Design. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasighi, M.; Romanova, J.; Nedyalkova, M. A multilevel approach for screening natural compounds as an antiviral agent for COVID-19. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2022, 98, 107694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.-H. Anti–SARS-CoV-2 natural products as potentially therapeutic agents. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 590509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abubaker Bagabir, S.; Ibrahim, N.K.; Abubaker Bagabir, H.; Hashem Ateeq, R. COVID-19 and Artificial Intelligence: Genome sequencing, drug development and Vaccine Discovery. J. Infect. Public Health 2022, 15, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govianda, B.K.C.; Bocci, G.; Verma, S.; Hassan, M.M.; Holmes, J.; Yang, J.J.; Sirimulla, S.; Oprea, T.I. A machine learning platform to estimate anti-SARS-CoV-2 activities. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2021, 3, 527–535. [Google Scholar]

- Keshavarzi Arshadi, A.; Webb, J.; Salem, M.; Cruz, E.; Calad-Thomson, S.; Ghadirian, N.; Collins, J.; Diez-Cecilia, E.; Kelly, B.; Goodarzi, H.; et al. Artificial Intelligence for COVID-19 drug discovery and vaccine development. Front. Artif. Intell. 2020, 3, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhama, K.; Natesan, S.; Iqbal Yatoo, M.; Patel, S.K.; Tiwari, R.; Saxena, S.K.; Harapan, H. Plant-based vaccines and antibodies to combat COVID-19: Current status and prospects. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020, 16, 2913–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurup, V.M.; Thomas, J. Edible vaccines: Promises and challenges. Mol. Biotechnol. 2019, 62, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R.B.; Felton, A.; Kosak, K.; Kelsey, D.K.; Meschievitz, C.K. Prevention of experimental coronavirus colds with intranasal -2b interferon. J. Infect. Dis. 1986, 154, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, S.; Balkhy, H.; Gabere, M.N. Current treatment options and the role of peptides as potential therapeutic components for Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS): A Review. J. Infect. Public Health 2018, 11, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, T.W. Acute respiratory distress syndrome in critically ill patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. JAMA 2003, 290, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costantini, C.; Bellet, M.M.; Pariano, M.; Renga, G.; Stincardini, C.; Goldstein, A.L.; Garaci, E.; Romani, L. A reappraisal of Thymosin Alpha1 in cancer therapy. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Záruba, K.; Rastorfer, M.; Grob, P.J.; Joller-Jemelka, H.; Bolla, K. Thymopentin as adjuvant in non-responders or hyporesponders to hepatitis B vaccination. Lancet 1983, 322, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L. Study on Expression of Thymosin α1 with Plant Bioreactor. J. Sichuan Norm. Univ. 2009, 1, 112–117. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, L.; Chen, Y.; Shen, G.; Zhao, L.; Tang, K. Expression of bioactive thymosin alpha 1 (TA1) in marker-free transgenic lettuce (Lactuca sativa). Plant Mol. Biol. Report. 2010, 29, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, J.; Li, W.; Murakami, A.; Tamin, A.; Matthews, L.J.; Wong, S.K.; Moore, M.J.; Tallarico, A.S.; Olurinde, M.; Choe, H.; et al. Potent neutralization of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus by a human MAB to S1 protein that blocks receptor association. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 2536–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussavou, G.; Ko, K.; Lee, J.-H.; Choo, Y.-K. Production of monoclonal antibodies in plants for cancer immunotherapy. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 306164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boechat, J.L.; Chora, I.; Morais, A.; Delgado, L. The immune response to SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 immunopathology—Current perspectives. Pulmonology 2021, 27, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqazlan, N.; Diao, H.; Jevnikar, A.M.; Ma, S. Production of functional human interleukin 37 using plants. Plant Cell Rep. 2019, 38, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michot, J.-M.; Albiges, L.; Chaput, N.; Saada, V.; Pommeret, F.; Griscelli, F.; Balleyguier, C.; Besse, B.; Marabelle, A.; Netzer, F.; et al. Tocilizumab, an anti-IL-6 receptor antibody, to treat COVID-19-related respiratory failure: A case report. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 961–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wampler Muskardin, T.L. Intravenous anakinra for macrophage activation syndrome may hold lessons for treatment of cytokine storm in the setting of coronavirus disease 2019. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2020, 2, 283–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, C.; Koch, B.; Morikawa, K.; Suda, G.; Sakamoto, N.; Rueschenbaum, S.; Akhras, S.; Dietz, J.; Hildt, E.; Zeuzem, S.; et al. Macrophage-derived extracellular vesicles induce long-lasting immunity against hepatitis C virus which is blunted by polyunsaturated fatty acids. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favalli, E.G.; Ingegnoli, F.; De Lucia, O.; Cincinelli, G.; Cimaz, R.; Caporali, R. COVID-19 infection and rheumatoid arthritis: Faraway, so close! Autoimmun. Rev. 2020, 19, 102523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atherton, J.G.; Kratzing, C.C.; Fisher, A. The effect of ascorbic acid on infection of chick-embryo ciliated tracheal organ cultures by coronavirus. Arch. Virol. 1978, 56, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joffe, M.I.; Sukha, N.R.; Rabson, A.R. Lymphocyte subsets in measles. depressed helper/inducer subpopulation reversed by in vitro treatment with levamisole and ascorbic acid. J. Clin. Investig. 1983, 72, 971–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfefferle, S.; Schöpf, J.; Kögl, M.; Friedel, C.C.; Müller, M.A.; Carbajo-Lozoya, J.; Stellberger, T.; von Dall’Armi, E.; Herzog, P.; Kallies, S.; et al. The sars-coronavirus-host interactome: Identification of cyclophilins as target for Pan-Coronavirus inhibitors. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Cao, R.; Zhang, L.; Yang, X.; Liu, J.; Xu, M.; Shi, Z.; Hu, Z.; Zhong, W.; Xiao, G. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-ncov) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colson, P.; Rolain, J.-M.; Lagier, J.-C.; Brouqui, P.; Raoult, D. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine as available weapons to fight COVID-19. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 55, 105932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrid, P.B.; Panchal, R.G.; Warren, T.K.; Shurtleff, A.C.; Endsley, A.N.; Green, C.E.; Kolokoltsov, A.; Davey, R.; Manger, I.D.; Gilfillan, L.; et al. Evaluation of ebola virus inhibitors for drug repurposing. ACS Infect. Dis. 2015, 1, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosseboeuf, E.; Aubry, M.; Nhan, T.; de Pina, J.J.; Rolain, J.M.; Raoult, D.; Musso, D. Azithromycin inhibits the replication of zika virus. J. Antivir. Antiretrovir. 2018, 10, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Lv, D.; Wang, S.; Wang, D.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Hong, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Cao, Y.; Chai, Y. Surface plasmon resonance-based membrane protein-targeted active ingredients recognition strategy: Construction and implementation in ligand screening from herbal medicines. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 3972–3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, Z.; Wang, G.; Lau, J.Y.-N.; Zhang, K.; Li, W. COVID-19 in early 2021: Current status and looking forward. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leneva, I.; Kartashova, N.; Poromov, A.; Gracheva, A.; Korchevaya, E.; Glubokova, E.; Borisova, O.; Shtro, A.; Loginova, S.; Shchukina, V.; et al. Antiviral Activity of Umifenovir In Vitro against a Broad Spectrum of Coronaviruses, Including the Novel SARS-CoV-2 Virus. Viruses 2021, 13, 1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Qi, C.; Shen, L.; Li, J. Clinical trial analysis of 2019-ncov therapy registered in China. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 540–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ader, F.; Peiffer-Smadja, N.; Poissy, J.; Bouscambert-Duchamp, M.; Belhadi, D.; Diallo, A.; Delmas, C.; Saillard, J.; Dechanet, A.; Mercier, N.; et al. An open-label randomized controlled trial of the effect of lopinavir/ritonavir, lopinavir/ritonavir plus IFN-β-1a and hydroxychloroquine in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 27, 1826–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscatelli, F.; Sessa, F.; Valenzano, A.; Polito, R.; Monda, V.; Cibelli, G.; Villano, I.; Pisanelli, D.; Perrella, M.; Daniele, A.; et al. COVID-19: Role of nutrition and supplementation. Nutrients 2021, 13, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakoor, H.; Feehan, J.; Al Dhaheri, A.S.; Ali, H.I.; Platat, C.; Ismail, L.C.; Apostolopoulos, V.; Stojanovska, L. Immune-boosting role of vitamins D, C, E, zinc, selenium and omega-3 fatty acids: Could they help against COVID-19? Maturitas 2021, 143, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M.M.; Herter-Aeberli, I.; Zimmermann, M.B.; Spieldenner, J.; Eggersdorfer, M. Strengthening the immunity of the Swiss population with micronutrients: A narrative review and call for action. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2021, 43, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N. Role of vitamin D in preventing of COVID-19 infection, progression and severity. J. Infect. Public Health 2020, 13, 1373–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonnecke, B.J.; McGill, J.L.; Ridpath, J.F.; Sacco, R.E.; Lippolis, J.D.; Reinhardt, T.A. Acute phase response elicited by experimental bovine diarrhea virus (BVDV) infection is associated with decreased vitamin D and E status of vitamin-replete preruminant calves. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 5566–5579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, C.E.; Sijtsma, S.R.; Kouwenhoven, B.; Rombout, J.H.W.M.; van der Zijpp, A.J. Epithelia-damaging virus infections affect vitamin A status in chickens. J. Nutr. 1992, 122, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.; Kumar, M.; Bedi, O.; Gupta, M.; Kumar, S.; Jaiswal, G.; Rahi, V.; Yedke, N.G.; Bijalwan, A.; Sharma, S.; et al. Role of vitamins and minerals as immunity boosters in COVID-19. Inflammopharmacology 2021, 29, 1001–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, J.; Tinkov, A.; Strand, T.A.; Alehagen, U.; Skalny, A.; Aaseth, J. Early nutritional interventions with zinc, selenium and vitamin D for raising anti-viral resistance against Progressive COVID-19. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Te Velthuis, A.J.; van den Worm, S.H.; Sims, A.C.; Baric, R.S.; Snijder, E.J.; van Hemert, M.J. Zn2+ inhibits coronavirus and arterivirus RNA polymerase activity in vitro and zinc ionophores block the replication of these viruses in cell culture. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1001176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, M.A.; Shi, Q.; Morris, V.C.; Levander, O.A. Rapid genomic evolution of a non-virulent coxsackievirus B3 in selenium-deficient mice results in selection of identical virulent isolates. Nat. Med. 1995, 1, 433–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur, S.M.; Rath, S.; Ahmad, V.; Ahmad, A.; Ateeq, B.; Khan, M.I. Nutritive vitamins as epidrugs. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 61, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, H.M.; Ibrahim, S.; Zaim, A.; Ibrahim, W.H. The role of iron in the pathogenesis of COVID-19 and possible treatment with lactoferrin and other iron chelators. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 136, 111228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.; Bhuiyan, F.R.; Emon, T.H.; Hasan, M. Prospects of nutritional interventions in the care of COVID-19 patients. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).