Abstract

This review evaluates the role of α-adrenoceptor antagonists as a potential treatment of prostate cancer (PCa). Cochrane, Google Scholar and Pubmed were accessed to retrieve sixty-two articles for analysis. In vitro studies demonstrate that doxazosin, prazosin and terazosin (quinazoline α-antagonists) induce apoptosis, decrease cell growth, and proliferation in PC-3, LNCaP and DU-145 cell lines. Similarly, the piperazine based naftopidil induced cell cycle arrest and death in LNCaP-E9 cell lines. In contrast, sulphonamide based tamsulosin did not exhibit these effects. In vivo data was consistent with in vitro findings as the quinazoline based α-antagonists prevented angiogenesis and decreased tumour mass in mice models of PCa. Mechanistically the cytotoxic and antitumor effects of the α-antagonists appear largely independent of α 1-blockade. The proposed targets include: VEGF, EGFR, HER2/Neu, caspase 8/3, topoisomerase 1 and other mitochondrial apoptotic inducing factors. These cytotoxic effects could not be evaluated in human studies as prospective trial data is lacking. However, retrospective studies show a decreased incidence of PCa in males exposed to α-antagonists. As human data evaluating the use of α-antagonists as treatments are lacking; well designed, prospective clinical trials are needed to conclusively demonstrate the anticancer properties of quinazoline based α-antagonists in PCa and other cancers.

1. Introduction

Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed male cancer in the world [1]. In Australia, prostate cancer account for approximately 30% of all newly diagnosed cancers and is the second most common cause of cancer-specific death in men [2]. Early stage prostate cancer is highly manageable using definitive radical prostatectomy and/or radiotherapy techniques. However, an estimated one-fifth of men will experience disease recurrence following curative treatment modalities [3,4,5] and resort to first-generation androgen deprivation therapies for long-term management of their disease. Unfortunately, progression after androgen deprivation therapy indicates the transition to castrate-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), which is considered to be both inevitable and incurable. Although there has been significant progress in the CRPC treatment landscape (e.g., enzalutamide, abiraterone, cabazitaxel), there are no currently available therapies which provide a survival benefit greater than twelve months [6,7,8,9,10]. Therefore, there is an urgent need for novel agents to improve the oncological and survival outcomes for these last-resort patients. One such modality may be through the use of α1-adrenoceptor (ADR) antagonists.

Adrenoceptors (also known as adrenergic receptors) are members of the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) superfamily, which can be further broken down into α and β subtypes with several homologous isoforms including α-1 (A, B, and D), -2 (A, B, and C), and β-1, 2, and 3 [11]. While all adrenergic receptors play an important role in regulating human tissue homeostasis, the focus of this review will primarily cover α1-ADRs in the human prostate. α1-ADRs are largely found in the stromal region of the human prostate, with few α1-ADR receptors localised in the prostate epithelium. Although, the α1A-ADR isoform (previously identified as α1C) is known to make up approximately 70% of the prostatic α1-ADRs [12], recent evidence suggests that the distribution of α1-ADR isoforms (A, B and D) change with advancing age and are correlated with the subsequent onset of prostatic hyperplasia [13]. Likewise, receptor localisation and expression appears to be altered in prostate cancer tissues. Unlike normal prostate epithelium which expresses few α1-ADRs, prostate cancer epithelia have been reported to express functional α1A-ADR [14,15], as well as increased mRNA levels of α1B and α1D isoforms [16]. It remains unclear whether α1-ADRs have a role in promoting prostate carcinogenesis remains unclear. However, α1-ADRs have been identified to play a role in cellular proliferation in vitro [14,17,18,19] and therefore may be exploited for treatment of neoplasms.

α1-ADR antagonists (referred to here as “α-antagonists”) are commonly used in clinical practice to treat hypertension, and more recently, the urodynamic symptoms associated with benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH). In BPH, α-antagonists block receptor activation to relax the prostatic smooth muscle thereby improving rate of urine flow and other associated lower-urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) [20,21]. There are regional differences in the commonly prescribed α-antagonists for BPH. In the United States, the non-selective doxazosin and terazosin are the most commonly prescribed α1-blockers due to their relatively long half-life [22,23] and clinically significant improvement in BPH-related LUTS. Furthermore, these drugs have been associated with fewer adverse drug-related cardiovascular side effects, compared to prazosin [24]. However, in Australia, the short acting and non-selective prazosin is clinically favored over other α-antagonists primarily due to the rapid mitigation of LUTS. The highly selective tamulosin, also offer significant reduction in BPH-related LUTS symptoms, however, at a cost of ejaculatory dysfunction making this α1-ADR antagonists undesirable for some men [24].

In the late 1990s, monotherapy with α-antagonists was shown to provide long-term clinical benefits that could not be explained solely by acute prostatic relaxation [25,26,27]. In support of these findings, a more recent study uncovered a large proportion of men (70%) experienced continued improvement of BPH-associated LUTS following discontinuation of α-antagonists [28]. Subsequent studies over the next sixteen years have identified that some of these drugs possess novel cytotoxic actions in diseased prostates, including prostate and other cancers. Despite the plethora of original papers investigating the anticancer effects of these drugs, only few systematic reviews since the early 2000s have been carried out to colligate the more recent published findings [29,30,31,32,33]. Therefore, the aim of this systematic literature review is to analyse the current evidence for the use of α-antagonists as potential treatment options for prostate cancer (PCa). Specifically, this review will colligate the anticancer mechanisms of α-antagonists, evaluate the evidence supporting clinical anticancer efficacy of these drugs in PCa, and evaluate the evidence for use of these drugs in other cancers.

2. Results

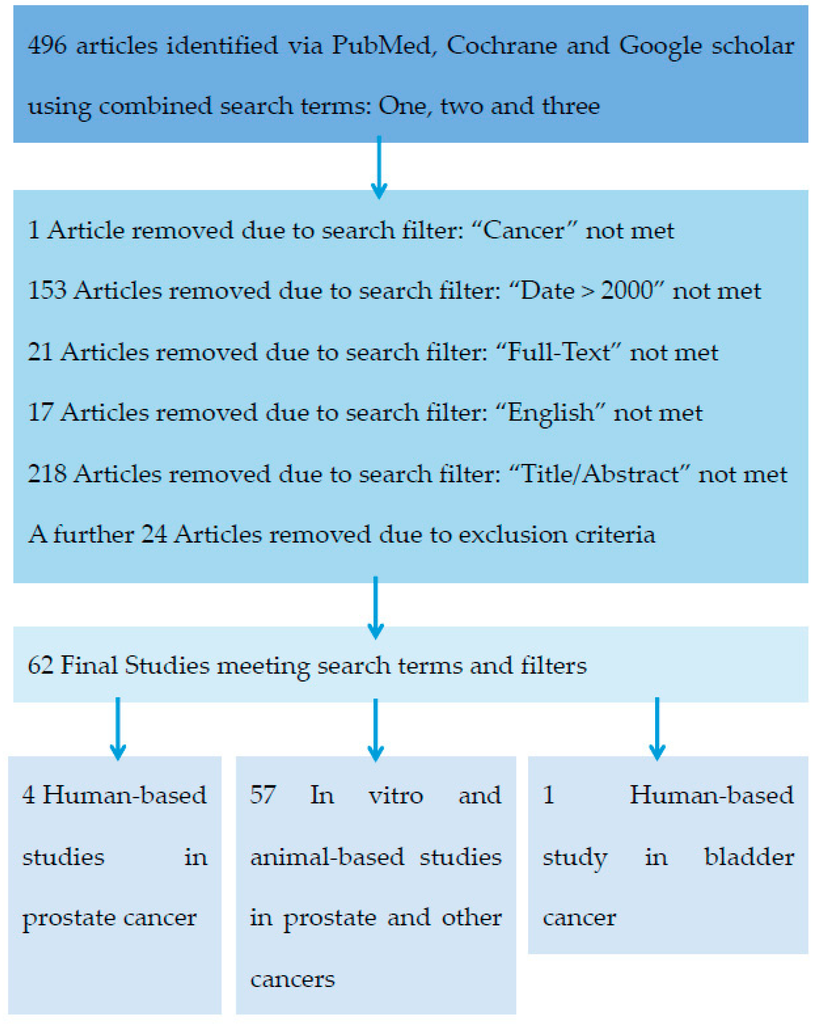

Pubmed, Google Scholar and Cochrane databases were accessed to retrieve articles. The search terms used to find the relevant articles were separated into three categories: terms that describe the α-antagonists, the target tissue and the action of the drugs (Table A1). Four hundred and ninety-six articles were identified using the inclusion criteria by searching three databases: Cochrane, Pubmed and Google Scholar. After exclusion criteria were applied, sixty-two relevant articles were obtained, consisting of fifty-four original manuscripts and eight review articles. (Figure A1). Of the fifty-four research articles identified only four studies examined the role of α-antagonists in PCa development in humans (Table 1). The majority focused on the cytotoxic and anti-tumour activity of α-antagonists in vitro and in animal models (Table 2). These retrospective cohort and observational human studies examined the effects of both quinazoline and non-quinazoline α-antagonists, but show only an overall decreased incidence of PCa. Two additional researchers replicated the search which returned identical results, validating the method used, for robustness.

Table 1.

Clinical-based studies investigating the effect of α1-antagonists on prostate cancer (PCa).

Table 2.

Summary of identified studies investigating the anticancer effect of α-antagonists.

3. Discussion

The overall aim of this literature review was to analyse the current evidence for the clinical use of α-antagonists as a potential treatment modality for PCa. A summary of results from the sixty-two studies identified in this systematic review can be found in Table 2.

3.1. In Vitro Evidence

3.1.1. Quinazoline/Piperazine-Dependence

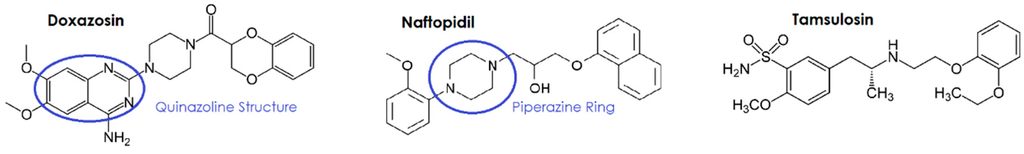

In vitro studies provide substantial evidence that the quinazoline α-antagonists doxazosin, terazosin and prazosin exhibit cytotoxic activity in the prostate cancer cell lines LNCaP (androgen-dependent), DU145 and PC-3 (castrate-resistant) cell lines [38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,84,85,86,87]. The structurally similar piperazine, naftopidil, also produced cytotoxic effects in the androgen-dependent LNCaP and E9 cell lines [88]. However these effects were not seen with the sulphonamide based tamsulosin [88] suggesting that the quinazoline/piperazine ring structure maybe responsible for their cytotoxicity (Figure 1). Furthermore, a number of studies have also investigated the use of doxazosin and naftopidil analogues, which demonstrated similar cytotoxic potential to the parent drug [54,55,89,90].

Figure 1.

Structural comparison of the α-antagonists doxazosin, naftopidil and tamsulosin.

3.1.2. α1-Adrenoceptor-Independence

The mechanisms for cytotoxicity appear to be independent of α1-blockade [39,40,41] as demonstrated by several studies, through the use of phenoxybenzamine (a non-selective, irreversible α-antagonist). Doxazosin and terazosin were observed to reduce cell viability and induce apoptosis in the presence of phenoxybenzamine [32,38,42,43]. This independent action is supported by two studies that proposed involvement of the 5HT receptor [44,89] which resulted in reduced cell viability and apoptosis in PCa.

3.1.3. Cell Death Mechanisms

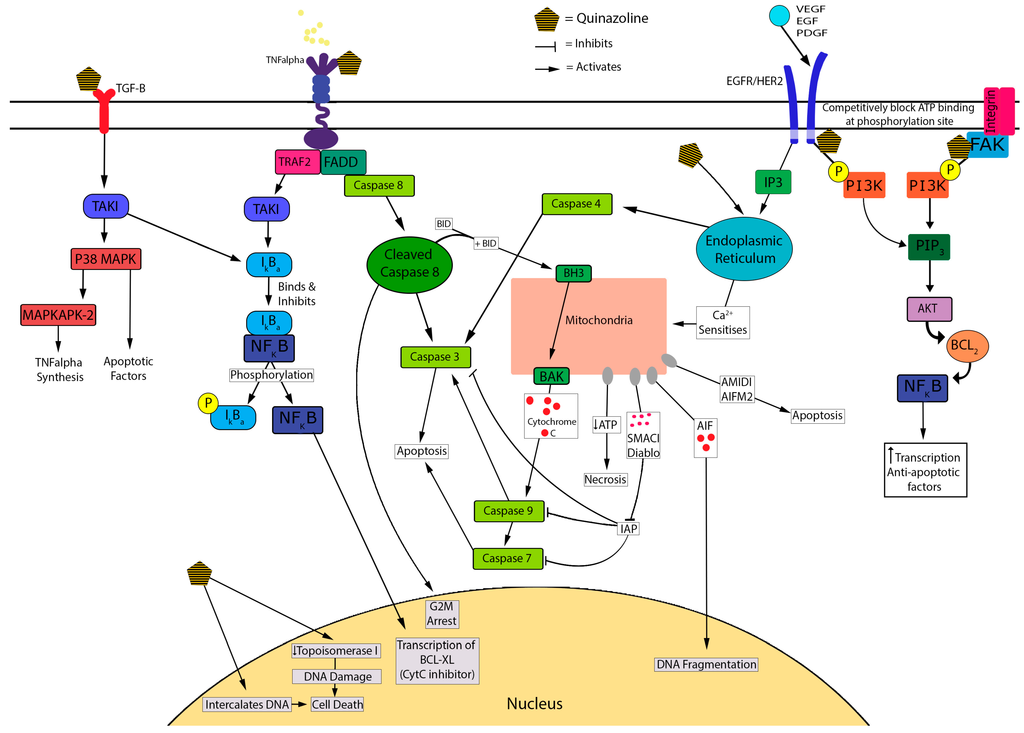

There are several potential mechanisms accounting for the cytotoxic actions of the quinazoline/piperazosine α-antagonists, including apoptosis, decreased cell proliferation and decreased angiogenesis which are crucial mediators of quinazoline-induced cytotoxicity in PCa cell lines [38]. An illustrative summary of the mechanisms contributing to α-antagonist-induced cytotoxicity is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Proposed cytotoxic mechanisms underlying quinazoline-based α-antagonists.

Early work by Kyprianou, N. et al. (2000) [32] showed that doxazosin (15 mM) and terazosin (15 mM) induce apoptosis in a dose dependent manner in PC-3 cell lines using the TUNEL assay [38,42]. As well as inducing apoptosis, doxazosin and terazosin were shown to inhibit cell adhesion to the extracellular matrix by inducing anoikis. Both agents induced apoptosis in prostate epithelial and smooth muscle cells at dose ranges used for the treatment of BPH [38]. Similarly Garrison, J. et al. (2006) [45] proposed that apoptosis was an important mediator of doxazosin-induced cytotoxicity (at 25 mM/L) in both malignant and benign prostate epithelial cells (PC-3 and BPH-1 cell lines). These authors suggested that this occurs through increased caspase 8 activation via formation of the death-inducing signalling complex (DISC) [32,45]. Caspase 8 mediates cell cycle arrest at the G2-M phase [46], and activates both cleaved caspase 3 and tBid at the BAX/Bak receptor [32,56]. This results in the release of mitochondrial stress related pro-apoptotic inducing factors including: cytochrome C, Smac/diablo, AMID and AIF [29,35,47,91]. More recently, Forbes, A. et al. (2016) [47] found that in PCa cells, the activation of caspase 3 was similar for prazosin and doxazosin, and suggested superior activity to terazosin, silodosin and alfuzosin. Prazosin (30 mM) treatment resulted in a six-fold increase in caspase 3 activation in LNCaP versus a two-fold increase in PC-3 cells suggesting androgen-dependent prostate cencer (ADPC) cells have greater sensitivity to these effects [47]. Cleaved caspase 3 is used as a marker for apoptosis [32] and is activated via DISC through FADD recruitment [32,45]. Some studies support Forbes’ finding of a dose-dependent increase in caspase 3 activation and consequent apoptosis when treated with quinazolines [32,47,48]. A decrease in HIF-1 (a mediator of resistance) was also shown in LNCaP cells post quinazoline exposure [47].

Additionally, α-antagonists exhibit cytotoxicity via cell-cycle arrest. Naftopidil induced G1 cell-cycle arrest in PCa cells in vitro, as did silodosin, but to a lesser extent [88]. Similarly, prazosin and doxazosin caused an increase in DNA strand breakage leading to subsequent G2 cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis, possibly through the inactivation of CDK1 [46,57]. Ho, C. et al. (2015) [58] showed that the reversible non-selective α-antagonist, phentolamine (an imidazoline), caused cell-cycle arrest in CRPC cells by inducing microtubule assembly, leading to mitotic arrest of the cell-cycle and mitochondrial damage. This inhibition of mitosis is a similar chemotherapeutic mechanism to taxanes [59]. It was suggested that disruption of the cell-cycle by quinazolines can be explained by competitive inhibition of the ATP attachment of tyrosine kinase and inhibiting phosphorylation of PI3K from the following receptors: HER2/Neu, EGF, and VEGF [32,60]. These receptors are well-identified targets of current chemotherapeutic agents, such as bevacizumab which targets VEGF.

Another proposed mechanism underlying the cytotoxic actions of α-antagonists is disruption of DNA integrity. Desiniotis, A. et al. (2011) [32] suggested that quinazolines derivatives cause DNA intercalation, similar to anthracycline chemotherapeutics. DNA fragmentation was also observed in studies that tested doxazosin (25 mM) [32,49]. Doxazosin is proposed to inhibit topoisomerase 1, inducing DNA damage and resulting in synergistic cytotoxic activity with etoposide and adriamycin [86]. Furthermore, apoptosis and cell-cycle arrest lead to decreased cell growth and proliferation of PCa cells. This leads to decreased cell survival, migration and adhesion resulting in anoikis [50,61,90].

In vitro evidence also suggests that quinazolines have the potential to disrupt key mediators of angiogenesis. Quinazolines downregulate VEGF, resulting in reduced repression of TGF-β receptor [32,51,60]. TGF-β is responsible for the transcription of various apoptosis factors as well as increasing IκBα; the inhibitor of NF-κB [32,60]. Forbes, A. et al. (2016) [51] noted an increase in stress related factors such as p38α and MAPKs in PCa cells treated with α-antagonists [47], which is suggestive of TGF-β activation. The α-antagonist-mediated disruption and down-regulation of VEGF results in decreased angiogenesis by increasing apoptosis and anoikis [32,52,61]. The inhibition of this signalling pathway blocks Bcl-2, an anoikis inhibiting factor that is identified in CRPC and is a mediator for cell immunity via bypass pathway mutations [32,52]. Targeting this factor improves selectivity and may improve treatment outcomes in CRPC. This was observed in prostate cells, where treatment with doxazosin resulted in inhibition of VEGF-induced angiogenesis, reduced cell migration and increased cell death due to anoikis [53,61], possibly via EphA2 agonist activity [62].

3.2. In Vivo Evidence

Consistent with in vitro studies, the ability of quinazoline α-antagonists to reduce tumour growth and potentially decrease angiogenesis is also observed in mice models of PCa. PCa xenografts in mice showed that tumour mass was significantly reduced when treated with quinazoline compounds prazosin and doxazosin compared to untreated controls, possibly through the induction of apoptosis [38,42,46,57,62]. Terazosin treatment in nude mice significantly reduced VEGF induced angiogenesis. This effect was also seen in prostate tumour mice models [39] suggesting that terazosin has very potent anti-angiogenic effects, reducing tumour volume over time. Anti-proliferative effects of doxazosin were also observed in Wistar rats treated with doxazosin and finasteride [63]. Interestingly, doxazosin has recently been identified as a novel EphA2 agonist [47,62], which triggers PCa cytotoxicity via cell rounding and detachment in vitro and this mechanism may translate to animal models [62]. In line with previous in vivo studies, doxaozisn was previously found to reduce tumour metastasis and improve survival of PC-3 xenograft nude mice. These anti-tumour effects were proposed to occur, to some extent, by EphA2-mediated cell detachment, inhibition of tumour cell migration [62], and indirect activation of apoptosis.

3.3. Clinical Evidence

To determine if the cytotoxic and anti-tumour effects observed in vitro and in mice models translate into a potential therapeutic application in human patients, we examined their effects in patients taking them long term (ranging from 3 to 11 months or longer) [34,36]. However, to date there are only four retrospective human studies that have investigated the benefit of quinazoline based α-antagonists in patients after original treatment ended (Table 1). Interestingly, both quinazoline and non-quinazoline α-antagonists appear to decrease the incidence of PCa at doses indicated for the symptomatic relief of LUTs [35,36,37,64]. It is therefore difficult to evaluate their potential for treating PCa.

3.4. Anticancer Effects of α-Antagonists in Other Cancers

Lastly, we examined the potential of cytotoxic and antitumor actions of α-antagonists in other cancers (See Table 2 and Supplementary Material Figure S1 for detailed review). Consistent with in vitro and in vivo animal findings in PCa, classical α-antagonists and their analogues appear to have broad activity, exhibiting cytotoxicity in other cancer cell lines including urogenital [44,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74], gastrointestinal [73,74,75,76,77], lung [74,78], blood [79], brain [80,81] and thyroid [82]. Importantly, the cytotoxic and anti-proliferative effects are supported by several in vivo mice studies [48,66], suggesting ubiquitous anticancer actions of these drugs. In support of in vitro findings a retrospective study in 24 patients with bladder cancer, 15 of which had been treated with terazosin over a 3–6 month period, had a reduction in incidence, tissue MVD and increase in apoptotic index [83]. The only trials with doses that are of clinical relevance are with bladder, pituitary and ovarian cancer, all of which are within the standard dosage ranges of the respective medications [48,50,66]. The proposed cytotoxic mechanisms of α-antagonists in other cancers differ from those identified in PCa, suggesting the magnitude of their anticancer effects may vary between cancer types. It is difficult to draw sound conclusions of the efficacy of α-antagonists in other cancers from this data.

4. Conclusions

PCa is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in Australia with substantial mortality associated with the castrate resistant form. Current treatments are significantly limited by the development of resistance, as well as severe toxicity. Therefore, there is an urgent need to identify alternate or adjunct treatment options. Given their key role in managing the LUTs associated with PCa and its treatments, as well as in vitro cytotoxicity against PCa cell lines, α-antagonists may offer such a treatment option. However, apart from a series of excellent in vitro studies and limited animal studies, the potential of α-antagonists as a treatment option in human patients remains unclear. Therefore, the purpose of this literary review was to analyse the current evidence for the use of α-antagonists in the treatment of prostate and other cancers, and elucidate mechanisms responsible for their cytotoxic effects.

Several elegant in vitro studies demonstrate that quinazoline based α-antagonists (doxazosin, terazosin and prazosin) are cytotoxic to PCa cell lines by inducing apoptosis, inhibiting cell proliferation and angiogenesis. Similarly, these effects were also observed with the piperazine based agent naftopidil. In contrast tamsulosin, a sulphonamide based compound did not exhibit cytotoxic activity, suggesting that structural specificity is important in eliciting cytotoxic action. In vitro studies also suggest that the quinazoline α-antagonists may also target angiogenesis by disrupting VEGF. Furthermore, several studies also suggest that the cytotoxic actions are not limited to PCa cell lines as α-antagonists were also shown to induce cell death in some of the following cell lines: Bladder HT1376, Ovarian SKOV-3, Renal Carcinoma ACHN and Caki-2. However, more robust trials with standardised methodologies are required to strengthen the evidence of α-antagonists as chemotherapeutic agents in cancers other than prostate.

The in vitro findings are reflected in mice models of PCa, with many studies showing that tumour growth and angiogenesis is significantly decreased when animals are treated with quinazoline or piperazine agents. However, evidence for the potential of the quinazoline and piperazine α-antagonists to treat PCa in human patients is lacking. We identified only four studies looking at the risk of developing PCa in human patients using α-antagonists. These retrospective and observational cohort studies did not examine the potential of these agents to treat PCa. Instead, they showed a decreased incidence of PCa in long term users of α-antagonists.

Therefore, while the in vitro and animal studies clearly demonstrate the potential role of quinazoline and piperazine based α-antagonists in the treatment of prostate and other cancers, well designed, prospective clinical trials in humans are required to ultimately evaluate their efficacy as either a primary treatment option or as an adjunct. It is difficult to draw sound conclusions of the efficacy of α-antagonists in other cancers from the data analysed in this review. More robust trials with standardised methodologies are required to strengthen the evidence of α-antagonists as chemotherapeutic agents in cancers other than prostate. We hope the findings from this literature review will stimulate further research to potentially place α-antagonists as possible treatment options for PCa in the future.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials can be found at www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/17/8/1339/s1.

Acknowledgments

All sources of funding of the study should be disclosed. Please clearly indicate grants that you have received in support of your research work. Clearly state if you received funds for covering the costs to publish in open access.

Author Contributions

Shailendra Anoopkumar-Dukie, Catherine M. McDermott and Russ Chess-Williams conceived and designed the study; Mallory Batty, Rachel Pugh, Ilampirai Rathinam, Joshua Simmonds, Edwin Walker and Amanda Forbes carried out the review, analysed the data and prepared the manuscript. Amanda Forbes, Catherine M. McDermott, Shailendra Anoopkumar-Dukie, David Christie and Russ Chess-Williams drafted and edited the manuscript. David Christie and Briohny Spencer provided feedback on the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Inclusion/exclusion search terms/filters included in methodology.

| Search Term 1: Agent | Search Term 2: Target Tissue | Search Term 3: Action |

|---|---|---|

| Alfuzosin α Adrenergic antagonist α Adrenoreceptor blockers α Blocker Doxazosin Naftopidil Phentolamine Prazosin Silodosin Terazosin | Adenocarcinoma Cancer Carcinoma Neoplasm Prostate cancer | Anoikis Anti-angiogenic Anti-proliferative Anticancer Antineoplastic Apoptosis Cytotoxic |

| Filters Applied in PubMed | ||

| Text—Full text Publication Date—2000–2016 Language—English Subjects—Cancer Search Fields—Title/Abstract | ||

| Exclusion terms: In Title/Abstract | ||

| AG1478, α-methyl-DL-tryptophan, α-linolenic, α-methyltryptophan, Biscoumarins, BYL719, Calcium channels, Cardiotoxic, Chitosan, Gambogic acid, Glyceollin, Hepatocarcinogens, HhAntag691, Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor, LSC, Mast cells, PSC833, R482G isoform, Raloxifene, Stapling, Stilbenes, Toremifene, Triphosphate-binding | ||

| Combined Search Terms | ||

| (α adrenergic antagonist OR α adrenoreceptor blocker OR α blocker OR Prazosin OR Doxazosin OR Naftopidil OR Phentolamine OR Alfuzosin OR Terazosin OR Silodosin) AND (Neoplasm OR Cancer OR Prostate cancer OR Carcinoma OR Adenocarcinoma) AND (Anoikis OR Antineoplastic OR Apoptosis OR Anticancer OR Anti-angiogenic OR Anti-proliferative OR Cytotoxic) NOT (Calcium channels OR Cardiotoxic OR LSC OR Biscoumarins OR Glyceollin OR Chitosan OR toremifene OR triphosphate-binding OR α-linolenic OR α-methyl-DL-tryptophan OR HhAntag691 OR α-methyltryptophan OR raloxifene OR AG1478 OR R482G isoform OR PSC833 OR Mast cells OR Gambogic acid OR hepatocarcinogens OR insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor OR stapling OR BYL719 OR stilbenes) | ||

Figure A1.

Stepwise process used to determine the final list of studies.

References

- Bray, F.; Ren, J.S.; Masuyer, E.; Ferlay, J. Global estimates of cancer prevalence for 27 sites in the adult population in 2008. Int. J. Cancer 2013, 132, 1133–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Prostate Cancer in Australia; Cancer Series no. 79. Cat. no. CAN 76; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2013.

- Freedland, S.J.; Humphreys, E.B.; Mangold, L.A.; Eisenberger, M.; Dorey, F.J.; Walsh, P.C.; Partin, A.W. Risk of prostate cancer-specific mortality following biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. JAMA 2005, 294, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zumsteg, Z.S.; Spratt, D.E.; Romesser, P.B.; Pei, X.; Zhang, Z.; Polkinghorn, W.; McBride, S.; Kollmeier, M.; Yamada, Y.; Zelefsky, M.J. The natural history and predictors of outcome following biochemical relapse in the dose escalation era for prostate cancer patients undergoing definitive external beam radiotherapy. Eur. Urol. 2015, 67, 1009–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kupelian, P.A.; Buchsbaum, J.C.; Patel, C.; Elshaikh, M.; Reddy, C.A.; Zippe, C.; Klein, E.C. Impact of biochemical failure on overall survival after radiation therapy for localized prostate cancer in the PSA era. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2002, 52, 704–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombal, B.; Borre, M.; Rathenborg, P.; Werbrouck, P.; van Poppel, H.; Heidenreich, A.; Lversen, P.; Braeckman, J.; Heracek, J.; Baskin-Bey, E.; et al. Enzalutamide monotherapy in hormone-naive prostate cancer: Primary analysis of an open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 592–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.J.; Smith, M.R.; de Bono, J.S.; Molina, A.; Logothetis, C.J.; de Souza, P.; Fizazi, K.; Mainwaring, P.; Piulats, J.M.; Ng, S.; et al. Abiraterone in metastatic prostate cancer without previous chemotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mottet, N.; Bellmunt, J.; Bolla, M.; Joniau, S.; Mason, M.; Matveev, V.; Schmid, H.P.; van der Kwast, T.; Wiegel, T.; Zattoni, F.; et al. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II: Treatment of advanced, relapsing, and castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur. Urol. 2011, 59, 572–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Bono, J.S.; Oudard, S.; Ozguroglu, M.; Hansen, S.; Machiels, J.P.; Kocak, I.; Gravis, G.; Bodrogi, I.; Mackenzie, M.J.; Shen, L.; et al. Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: A randomised open-label trial. Lancet 2010, 376, 1147–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrader, A.J.; Boegemann, M.; Ohlmann, C.H.; Schnoeller, T.J.; Krabbe, L.M.; Hajili, T.; Jentzmik, F.; Stoeckle, M.; Schrader, M.; Herrmann, E.; et al. Enzalutamide in castration-resistant prostate cancer patients progressing after docetaxel and abiraterone. Eur. Urol. 2014, 65, 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Cotecchia, S. The α1-adrenergic receptors: Diversity of signaling networks and regulation. J. Recept. Signal Transduct. Res. 2010, 30, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, D.T.; Schwinn, D.A.; Lomasney, J.W.; Allen, L.F.; Caron, M.G.; Lefkowitz, R.J. Identification, quantification, and localization of mRNA for three distinct α1 adrenergic receptor subtypes in human prostate. J. Urol. 1993, 150 Pt 1, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- White, C.W.; Xie, J.H.; Ventura, S. Age-related changes in the innervation of the prostate gland: Implications for prostate cancer initiation and progression. Organogenesis 2013, 9, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thebault, S.; Roudbaraki, M.; Sydorenko, V.; Shuba, Y.; Lemonnier, L.; Slomianny, C.; Deasilly, E.; Bonnal, J.L.; Mauroy, B.; Skryma, R.; et al. α1-Adrenergic receptors activate Ca2+-permeable cationic channels in prostate cancer epithelial cells. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 111, 1691–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, B.C.; Swigart, P.M.; Simpson, P.C. Ten commercial antibodies for α-1-adrenergic receptor subtypes are nonspecific. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2009, 379, 409–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng-Crank, J.; Kost, T.; Goetz, A.; Hazum, S.; Roberson, K.M.; Haizlip, J.; Godinot, N.; Robertson, C.N.; Saussy, D. The α 1C-adrenoceptor in human prostate: Cloning, functional expression, and localization to specific prostatic cell types. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995, 115, 1475–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thebault, S.; Flourakis, M.; Vanoverberghe, K.; Vandermoere, F.; Roudbaraki, M.; Lehennkyi, V.; Slomianny, C.; Beck, B.; Mariot, P.; Bonnal, J.L.; et al. Differential role of transient receptor potential channels in Ca2+ entry and proliferation of prostate cancer epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 2038–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munaron, L.; Antoniotti, S.; Lovisolo, D. Intracellular calcium signals and control of cell proliferation: How many mechanisms? J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2004, 8, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liou, S.F.; Lin, H.H.; Liang, J.C.; Chen, I.J.; Yeh, J.L. Inhibition of human prostate cancer cells proliferation by a selective α1-adrenoceptor antagonist labedipinedilol-A involves cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Toxicology 2009, 256, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jepsen, J.V.; Bruskewitz, R.C. Comprehensive patient evaluation for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology 1998, 51, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillenwater, J.Y.; Conn, R.L.; Chrysant, S.G.; Roy, J.; Gaffney, M.; Ice, K.; Dias, N. Doxazosin for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia in patients with mild to moderate essential hypertension: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-response multicenter study. J. Urol. 1995, 154, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.; Elliott, H.L.; Meredith, P.A.; Reid, J.I. Doxazosin, an α1-adrenoceptor antagonist: Pharmacokinetics and concentration-effect relationships in man. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1983, 15, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonders, R.C. Pharmacokinetics of terazosin. Am. J. Med. 1986, 80, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepor, H.; Kazzazi, A.; Djavan, B. α-Blockers for benign prostatic hyperplasia: The new era. Curr. Opin. Urol. 2012, 22, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michel, M.C.; Schafers, R.F.; Goepel, M. α-Blockers and lower urinary tract function: More than smooth muscle relaxation? BJU Int. 2000, 86, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McConnell, J.D.; Bruskewitz, R.; Walsh, P.; Andriole, G.; Lieber, M.; Holtgrewe, H.L.; Albertsen, P.; Roehrborn, C.G.; Nickel, J.C.; Wang, D.C.; et al. The effect of finasteride on the risk of acute urinary retention and the need for surgical treatment among men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Finasteride Long-Term Efficacy and Safety Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 338, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukacs, B.; Grange, J.C.; Comet, D.; Mc Carthy, C. Prospective follow-up of 3228 patients suffering from clinical benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) treated for 3 years wi alfuzosin in general practice. BPH Group in General Practice. Prog. Urol. J. Assoc. Fr. D’urol. Soc. Fr. Durol. 1999, 9, 271–280. [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama, T.; Watanabe, T.; Saika, T.; Nasu, Y.; Kumon, H.; Miyaji, Y.; Nagai, A. Natural course of lower urinary tract symptoms following discontinuation of α-1-adrenergic blockers in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Int. J. Urol. 2007, 14, 598–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishizaki, T.; Kanno, T.; Tsuchiya, A.; Kaku, Y.; Shimizu, T.; Tanaka, A. 1-[2-(2-Methoxyphenylamino)ethylamino]-3-(naphthalene-1-yloxy)propan-2-ol may be a promising anticancer drug. Molecules 2014, 19, 21462–21472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyprianou, N.; Vaughan, T.B.; Michel, M.C. Apoptosis induction by doxazosin and other quinazoline α1-adrenoceptor antagonists: A new mechanism for cancer treatment? Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2009, 380, 473–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patane, S. Insights into cardio-oncology: Polypharmacology of quinazoline-based α1-adrenoceptor antagonists. World J. Cardiol. 2015, 7, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desiniotis, A.; Kyprianou, N. Advances in the design and synthesis of prazosin derivatives over the last ten years. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2011, 15, 1405–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahmatzopoulos, A.; Rowland, R.G.; Kyprianou, N. The role of α-blockers in the management of prostate cancer. Expert Opin. Pharm. 2004, 5, 1279–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keledjian, K.; Borkowski, A.; Kim, G.; Isaacs, J.T.; Jacobs, S.C.; Kyprianou, N. Reduction of human prostate tumor vascularity by the α1-adrenoceptor antagonist terazosin. Prostate 2001, 48, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, A.M.; Warner, B.W.; Wilson, J.M.; Becker, A.; Rowland, R.G.; Conner, W.; Lane, M.; Kimbler, K.; Durbin, E.B.; Baron, A.T.; et al. Effect of α1-adrenoceptor antagonist exposure on prostate cancer incidence: An observational cohort study. J. Urol. 2007, 178, 2176–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, D.; Nishimatsu, H.; Kumano, S.; Hirano, Y.; Suzuki, M.; Fujimura, T.; Fukuhara, H.; Enomoto, Y.; Kume, H.; Homma, Y. Reduction of prostate cancer incidence by naftopidil, an α1-adrenoceptor antagonist and transforming growth factor-β signaling inhibitor. Int. J. Urol. 2013, 20, 1220–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilbro, J.; Mart, M.; Kyprianou, N. Therapeutic value of quinazoline-based compounds in prostate cancer. AntiCancer Res. 2013, 33, 4695–4700. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kyprianou, N.; Benning, C.M. Suppression of human prostate cancer cell growth by α1-adrenoceptor antagonists doxazosin and terazosin via induction of apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 4550–4555. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pan, S.L.; Guh, J.H.; Huang, Y.W.; Chern, J.W.; Chou, J.Y.; Teng, C.M. Identification of apoptotic and antiangiogenic activities of terazosin in human prostate cancer and endothelial cells. J. Urol. 2003, 169, 724–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walden, P.D.; Globina, Y.; Nieder, A. Induction of anoikis by doxazosin in prostate cancer cells is associated with activation of caspase-3 and a reduction of focal adhesion kinase. Urol. Res. 2004, 32, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benning, C.M.; Kyprianou, N. Quinazoline-derived α1-adrenoceptor antagonists induce prostate cancer cell apoptosis via an α1-adrenoceptor-independent action. Cancer Res. 2002, 62, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kyprianou, N. Doxazosin and terazosin suppress prostate growth by inducing apoptosis: Clinical significance. J. Urol. 2003, 169, 1520–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arencibia, J.M.; del Rio, M.; Bonnin, A.; Lopes, R.; Lemoine, N.R.; Lopez-Barahona, M. Doxazosin induces apoptosis in LNCaP prostate cancer cell line through DNA binding and DNA-dependent protein kinase down-regulation. Int. J. Oncol. 2005, 27, 1617–1623. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, E.J.; Del Rio, M.; Bonnin, A.; Lopes, R.; Lemoine, N.R.; Lopez-Barahona, M. Growth inhibitory effect of doxazosin on prostate and bladder cancer cells. Is the serotonin receptor pathway involved? Anticancer Res. 2005, 25, 4281–4286. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Garrison, J.B.; Kyprianou, N. Doxazosin induces apoptosis of benign and malignant prostate cells via a death receptor-mediated pathway. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.C.; Chueh, S.C.; Hsiao, C.J.; Li, T.K.; Chen, T.H.; Liao, C.H.; Lyu, P.C.; Guh, J.H. Prazosin displays anticancer activity against human prostate cancers: Targeting DNA and cell cycle. Neoplasia 2007, 9, 830–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forbes, A.; Anoopkumar-Dukie, S.; Chess-Williams, R.; McDermott, C. Relative cytotoxic potencies and cell death mechanisms of α1-adrenoceptor antagonists in prostate cancer cell lines. Prostate 2016, 76, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernando, M.A.; Heaney, A.P. α1-Adrenergic receptor antagonists: Novel therapy for pituitary adenomas. Mol. Endocrinol. 2005, 19, 3085–3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youm, Y.H.; Yang, H.; Yoon, Y.D.; Kim, D.Y.; Lee, C.; Yoo, T.K. Doxazosin-induced clusterin expression and apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. Urol. Oncol. 2007, 25, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahmatzopoulos, A.; Sheng, S.; Kyprianou, N. Maspin sensitizes prostate cancer cells to doxazosin-induced apoptosis. Oncogene 2005, 24, 5375–5383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partin, J.V.; Anglin, I.E.; Kyprianou, N. Quinazoline-based α 1-adrenoceptor antagonists induce prostate cancer cell apoptosis via TGF-β signalling and I κB α induction. Br. J. Cancer 2003, 88, 1615–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keledjian, K.; Kyprianou, N. Anoikis induction by quinazoline based α1-adrenoceptor antagonists in prostate cancer cells: Antagonistic effect of Bcl-2. J. Urol. 2003, 169, 1150–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, C.H.; Guh, J.H.; Chueh, S.C.; Yu, H.J. Anti-angiogenic effects and mechanism of prazosin. Prostate 2011, 71, 976–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, Y.J.; Yang, Y.T.; Garrison, J.B.; Kyprianou, N.; Chen, C.S. Pharmacological exploitation of the α1-adrenoreceptor antagonist doxazosin to develop a novel class of antitumor agents that block intracellular protein kinase B/Akt activation. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 4453–4462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrison, J.B.; Shaw, Y.J.; Chen, C.S.; Kyprianou, N. Novel quinazoline-based compounds impair prostate tumorigenesis by targeting tumor vascularity. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 11344–11352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cell Signalling Technology. Regulation of Apoptosis: Overview. 11. 2012. Available online: http://www.cellsignal.com/contents/science-pathway-research-apoptosis/regulation-of-apoptosis-signaling-pathway/pathways-apoptosis-regulation (accessed on 9 August 2016).

- Liu, C.M.; Lo, Y.C.; Tai, M.H.; Wu, B.N.; Wu, W.J.; Chou, Y.H.; Chai, C.Y.; Huang, C.H.; Chen, I.J. Piperazine-designed α1A/α1D-adrenoceptor blocker KMUP-1 and doxazosin provide down-regulation of androgen receptor and PSA in prostatic LNCaP cells growth and specifically in xenografts. Prostate 2009, 69, 610–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, C.H.; Hsu, J.L.; Liu, S.P.; Hsu, L.C.; Chang, W.L.; Chao, C.C.; Guh, J.H. Repurposing of phentolamine as a potential anticancer agent against human castration-resistant prostate cancer: A central role on microtubule stabilization and mitochondrial apoptosis pathway. Prostate 2015, 75, 1454–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abal, M.; Andreu, J.M.; Barasoain, I. Taxanes: Microtubule and centrosome targets, and cell cycle dependent mechanisms of action. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2003, 3, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anglin, I.E.; Glassman, D.T.; Kyprianou, N. Induction of prostate apoptosis by α1-adrenoceptor antagonists: Mechanistic significance of the quinazoline component. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2002, 5, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keledjian, K.; Garrison, J.B.; Kyprianou, N. Doxazosin inhibits human vascular endothelial cell adhesion, migration, and invasion. J. Cell. Biochem. 2005, 94, 374–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petty, A.; Myshkin, E.; Qin, H.; Guo, H.; Miao, H.; Tochtrop, G.P.; Hsieh, J.T.; Page, P.; Liu, L.L.; Lindner, D.J.; et al. A small molecule agonist of EphA2 receptor tyrosine kinase inhibits tumor cell migration in vitro and prostate cancer metastasis in vivo. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Justulin, L.A., Jr.; Acquaro, C.; Carvalho, R.F.; Silva, M.D.; Felisbino, S.L. Combined effect of the finasteride and doxazosin on rat ventral prostate morphology and physiology. Int. J. Androl. 2010, 33, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahmatzopoulos, A.; Kyprianou, N. Apoptotic impact of α1-blockers on prostate cancer growth: A myth or an inviting reality? Prostate 2004, 59, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, H.; Fernando, M.A.; Heaney, A.P. The α1-adrenergic receptor antagonist doxazosin inhibits EGFR and NF-κB signalling to induce breast cancer cell apoptosis. Eur. J. Cancer 2008, 44, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, M.S.; Kim, B.R.; Kang, S.; Kim, D.Y.; Rho, S.B. The antihypertension drug doxazosin suppresses JAK/STATs phosphorylation and enhances the effects of IFN-α/γ-induced apoptosis. Genes Cancer 2014, 5, 470–479. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kawahara, T.; Aljarah, A.K.; Shareef, H.K.; Inoue, S.; Ide, H.; Patterson, J.D.; Kashiwagi, E.J.; Han, B.; Li, Y.; Zheng, Y.C.; et al. Silodosin inhibits prostate cancer cell growth via ELK1 inactivation and enhances the cytotoxic activity of gemcitabine. Prostate 2016, 76, 744–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawahara, T.; Ide, H.; Kashiwagi, E.; Patterson, J.D.; Inoue, S.; Shareef, H.K.; Aljarah, A.K.; Zheng, Y.C.; Baras, A.S.; Miyamto, H. Silodosin inhibits the growth of bladder cancer cells and enhances the cytotoxic activity of cisplatin via ELK1 inactivation. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2015, 5, 2959–2968. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Iwamoto, Y.; Ishii, K.; Sasaki, T.; Kato, M.; Kanda, H.; Yamada, Y.; Arima, K.; Shiraishi, T.; Sugimura, Y. Oral naftopidil suppresses human renal-cell carcinoma by inducing G1 cell-cycle arrest in tumor and vascular endothelial cells. Cancer Prev. Res. 2013, 6, 1000–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakamoto, S.; Schwarze, S.; Kyprianou, N. Anoikis disruption of focal adhesion-Akt signaling impairs renal cell carcinoma. Eur. Urol. 2011, 59, 734–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takara, K.; Sakaeda, T.; Kakumoto, M.; Tanigawara, Y.; Kobayashi, H.; Okumura, K.; Noriaki, O.; Teruyoshi, Y. Effects of α-adrenoceptor antagonist doxazosin on MDR1-mediated multidrug resistance and transcellular transport. Oncol. Res. 2009, 17, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powe, D.G.; Voss, M.J.; Habashy, H.O.; Zanker, K.S.; Green, A.R.; Ellis, I.O.; Entschladen, F. α- And β-adrenergic receptor (AR) protein expression is associated with poor clinical outcome in breast cancer: An immunohistochemical study. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2011, 130, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Sharkawi, F.Z.; El Shemy, H.A.; Khaled, H.M. Possible anticancer activity of rosuvastatine, doxazosin, repaglinide and oxcarbazepin. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2014, 15, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanno, T.; Tanaka, A.; Shimizu, T.; Nakano, T.; Nishizaki, T. 1-[2-(2-Methoxyphenylamino)ethylamino]-3-(naphthalene-1-yloxy)propan-2-ol as a potential anticancer drug. Pharmacology 2013, 91, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaku, Y.; Tsuchiya, A.; Kanno, T.; Nakao, S.; Shimizu, T.; Tanaka, A.; Nishizaki, T. The newly synthesized anticancer drug HUHS1015 is useful for treatment of human gastric cancer. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2015, 75, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaku, Y.; Tsuchiya, A.; Shimizu, T.; Tanaka, A.; Nishizaki, T. HUHS1015 Suppresses colonic cancer growth by inducing necrosis and apoptosis in association with mitochondrial damage. Anticancer Res. 2016, 36, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shen, S.G.; Zhang, D.; Hu, H.T.; Li, J.H.; Wang, Z.; Ma, Q.Y. Effects of α-adrenoreceptor antagonists on apoptosis and proliferation of pancreatic cancer cells in vitro. World J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 14, 2358–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masachika, E.; Kanno, T.; Nakano, T.; Gotoh, A.; Nishizaki, T. Naftopidil induces apoptosis in malignant mesothelioma cell lines independently of α1-adrenoceptor blocking. Anticancer Res. 2013, 33, 887–894. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fuchs, R.; Stracke, A.; Ebner, N.; Zeller, C.W.; Raninger, A.M.; Schittmayer, M.; Kueznik, T.; Absenger-Novak, M.; Birner-Gruenberger, R. The cytotoxicity of the α1-adrenoceptor antagonist prazosin is linked to an endocytotic mechanism equivalent to transport-P. Toxicology 2015, 338, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albinana, V.; Villar, Gomez de Las Heras, K.; Serrano-Heras, G.; Segura, T.; Perona-Moratalla, A.B.; Mota-Perez, M.; de Campos, J.M.; Botella, L.M. Propranolol reduces viability and induces apoptosis in hemangioblastoma cells from von Hippel-Lindau patients. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2015, 10, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staudacher, I.; Jehle, J.; Staudacher, K.; Pledl, H.W.; Lemke, D.; Schweizer, P.A.; Becker, R.; Katus, H.A.; Thomas, D. HERG K+ channel-dependent apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in human glioblastoma cells. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e88164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchs, R.; Schwach, G.; Stracke, A.; Meier-Allard, N.; Absenger, M.; Ingolic, E.; Haas, H.S.; Pfragner, R.; Sadjak, A. The anti-hypertensive drug prazosin induces apoptosis in the medullary thyroid carcinoma cell line TT. Anticancer Res. 2015, 35, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tahmatzopoulos, A.; Lagrange, C.A.; Zeng, L.; Mitchell, B.L.; Conner, W.T.; Kyprianou, N. Effect of terazosin on tissue vascularity and apoptosis in transitional cell carcinoma of bladder. Urology 2005, 65, 1019–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.S.; Cho, H.J.; Cho, J.M.; Kang, J.Y.; Yang, H.W.; Yoo, T.K. Dual silencing of Hsp27 and c-FLIP enhances doxazosin-induced apoptosis in PC-3 prostate cancer cells. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 174392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.W.; Lee, J.W.; Chung, J.H.; Jo, J.K. Expression of heat shock protein 27 in prostate cancer cell lines according to the extent of malignancy and doxazosin treatment. World J. Men’s Health 2013, 31, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cal, C.; Uslu, R.; Gunaydin, G.; Ozyurt, C.; Omay, S.B. Doxazosin: A new cytotoxic agent for prostate cancer? BJU Int. 2000, 85, 672–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, K.L.; Cheng, H.L.; Huang, L.W.; Hsieh, B.S.; Hu, Y.C.; Chih, T.T.; Shyu, H.W.; Su, S.J. Combined effects of terazosin and genistein on a metastatic, hormone-independent human prostate cancer cell line. Cancer Lett. 2009, 276, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hori, Y.; Ishii, K.; Kanda, H; Iwamoto, Y.; Nishikawa, K.; Soga, N. Naftopidil, a selective α1-adrenoceptor antagonist, suppresses human prostate tumor growth by altering interactions between tumor cells and stroma. Cancer Prev. Res. 2011, 4, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; He, F.; Huang, M.; Liu, X.; Xiong, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Yang, Y.; Xu, X.J.; Yuan, M. Novel naftopidil-related derivatives and their biological effects as α1-adrenoceptors antagonists and antiproliferative agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 96, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hensley, P.J.; Desiniotis, A.; Wang, C.; Stromberg, A.; Chen, C.S.; Kyprianou, N. Novel pharmacologic targeting of tight junctions and focal adhesions in prostate cancer cells. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaku, Y.; Tsuchiya, A.; Kanno, T.; Nishizaki, T. HUHS1015 induces necroptosis and caspase-independent apoptosis of MKN28 human gastric cancer cells in association with AMID accumulation in the nucleus. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2015, 15, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).