Abstract

N-Alkyl deoxynojirimycin-derived drugs, belonging to the class of iminosugars, are well-known for their α-glucosidase inhibitory activity. N-Butyl-deoxynojirimycin (N-butyl-DNJ; NB-DNJ; also known as miglustat or UV-1) has been developed for the treatment of type 1 Gaucher disease and Niemann–Pick disease type C as Zavesca®. Furthermore, it behaves as a host-targeted glucomimetic that inhibits endoplasmic reticulum α-glucosidase I and II (GluI and GluII, respectively) enzymes, resulting in improper glycosylation and misfolding of viral glycoproteins; thus, it is a potential antiviral agent. It is studied against a broad range of viruses in vitro and in vivo; however, its utility as antiviral has not been fully explored. Other N-alkylated congeners of DNJ are in preclinical and clinical studies for diverse viral infections. The iminosugar N-9′-methoxynonyl-1-deoxynojirimycin (MON-DNJ or UV-4) is probably the most studied and potent inhibitor of α-Glu I and α-Glu II in clinical trials. It is often studied in the form of its hydrochloride salt (UV-4B) and has broad-spectrum activity against diverse viruses, including dengue and influenza. In clinical trials, it was found to be safe at all doses tested up to 1000 mg. In this paper, an overview on N-alkyl derivatives of DNJ is reported, focusing on their antiviral activity. The literature search was carried out by means of three literature databases, i.e., PubMed/MEDLINE, Google Scholar, and Scopus, screened using different keywords. A brief history of the discovery of their usefulness as antivirals is given, as well as the most recent studies on new compounds belonging to this class. Since different names are often used for the same compound, we tried to dissipate confusion and bring some order to this jumble of names. Specifically, in the tables, all the diverse names used to identify each compound, were reported.

1. Introduction

Deoxynojirimycin (DNJ, moranoline, duvoglustat) is an α-glucosidase (EC 3.2.1.20) inhibitor as well as a pharmacological chaperone of acid α-glucosidase [1]. It is an alkaloid contained in Morus alba L., a plant with high nutritional value [2]. Several biological activities, including antihyperglycemic, lipid-lowering, antitumor, anti-inflammatory, and antiviral, have been reported for this compound. Focusing on the latter, the first evidence of antiviral activity of DNJ emerged in the 1980s from studies on influenza virus [3], followed by vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) [4] and Sindbis virus [3,5]. The study by Datema et al. (1987) [6] evidenced that, in intact cells, DNJ exerts its action on both GluI and GluII, with higher activity on GluII. The latter is a heterodimeric enzyme bearing a catalytic α-subunit of the GH31 family and an accessory β-subunit that is necessary for the full catalytic activity and localisation of the heterodimer in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). An in-depth study on the key molecular differences between GluI and GluII has been recently reported in detail in a review by Oo et al. (2025) [7]. The inhibition of glucosidases for the antiviral activity was further investigated in retroviruses, such as Moloney murine leukemia virus [8], human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [9,10], and other viruses [2,11].

However, most studies regarding DNJ are focused on its derivatives and congeners, rather than on DNJ as it is [12,13]. Several derivatives of DNJ have been studied for their diverse biological activities, and research in this field continues [14]. Miglitol (Glyset®) received FDA approval for type 2 diabetes in 1996, while miglustat (Zavesca®) addresses lysosomal disorders, specifically Gaucher and Niemann–Pick diseases (from 2002 in the EU and from 2003 in the USA) [15]. These drugs are currently under study against other diseases, including melanoma [16], cardiac fibrosis [17], mitochondrial dysfunction [18], cystic fibrosis [19], periodontitis [20], and to ameliorate radioresistance in patients with cancer [21]. Interestingly, several N-alkylated congeners have demonstrated good antiviral properties, but their use in therapy is still under investigation. Some N-alkylated-DNJ congeners are included in the host-directed antivirals (HDA) category, which represents a promising avenue for broad-spectrum treatment, also with reduced risk of resistance development [22]. These compounds inhibit host α-glucosidases, which are pivotal for the glycoprotein folding endoplasmic reticulum quality control (ERQC) [23]. The external α-1,2-linked glucose is cleaved by endoplasmic reticulum (ER) GluI, and the inner α-1,3-linked glucoses are removed by ER GluII during N-linked glycan processing [24]. The impaired glucose cleavage results in misfolded proteins, which are either degraded by ER-associated degradation or secreted with altered properties. Thus, the treatment of virus-infected cells with iminosugars disrupts the proper virion morphogenesis [23]. The antiviral activity exerted by these compounds has been demonstrated against various viruses [25,26], including both enveloped DNA viruses, as HBV and positive-strand RNA viruses, namely flaviviruses, such as bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV), Dengue virus (DENV), and West Nile virus (WNV) [27], human hepatitis C virus (HCV) [28], and coronaviruses [29], namely Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 1 (SARS-CoV-1) [30] and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [31]. In this review, we summarize the N-alkyl derivatives of DNJ studied as antivirals. In the first part, we focused on the most common ones, also reporting the history of this class of compounds, while in the second part, some studies on the latest N-alkyl derivatives of DNJ are highlighted. The search was conducted using PubMed/MEDLINE, Google Scholar, and Scopus. The search criteria considered the occurrence of the association of different keywords: “deoxynojirimycin”, “N-alkyl-deoxynojirimycin” or “N-alkyl-DNJ” “-derivatives”, “N-9′-methoxynonyl-1-deoxynojirimycin”, “miglustat”, “N-nonyl-DNJ”, “N-[N-(4-azido-2-nitrophenyl)-6-aminohexyl]-DNJ” and the acronyms “NN-DNJ”, “MON-DNJ”, “NAP-DNJ”, “ToP-DNJ”, “UV-4”, “UV-4B”, “UV-5” in association with “antivirals”, “preclinical studies”, “clinical trials”, and “clinical studies”. The most relevant studies reporting the antiviral activity published in the English language were selected for preparing the review.

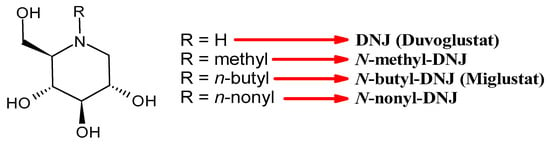

3. An Overview of N-Alkyl Derivatives of DNJ

In this section, the most studied N-alkyl derivatives of DNJ are summarized (Table 1). The first naturally occurring N-alkyl derivative of DNJ, N-methyl-DNJ, was isolated from the leaves and roots of Morus spp. (mulberry trees) [55]. However, this compound, although useful for structure–activity relationships, was overcome by other later-studied derivatives. Thus, N-methyl DNJ will not be detailed below. For the other N-alkyl derivatives of DNJ, the most characterizing antiviral activities have been taken into consideration. Half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) and half maximal effective concentration (EC50) are reported, calculated against diverse viruses, as detailed in the table. Half maximum cell cytotoxicity (CC50) was evaluated against mammalian and human cell lines, including Vero, human lung adenocarcinoma (Calu-3), human hepatocarcinoma (Huh-7), Madin–Darby bovine kidney (MDBK), and human hepatoma (HepG2 2.2.15), as detailed in the table.

Table 1.

Antiviral activities of the most common N-alkyl derivatives of DNJ.

3.1. Most Common N-Alkyl Derivatives of DNJ as Antivirals

In this subsection, we report an overview of the most common N-alkyl derivatives of DNJ (UV-1–UV-5) with their antiviral activities (Table 1).

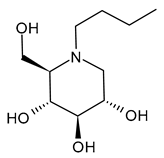

3.1.1. N-Butyldeoxynojirimycin (N-Butyl-DNJ or NB-DNJ or UV-1 or AT2221, Miglustat)

N-Butyldeoxynojirimycin (N-butyl-DNJ or NB-DNJ or UV-1 or AT2221, miglustat) is the four-carbon N-linked side chain DNJ derivative, which was approved in 2003 for Gaucher’s Disease [66] and in the European Union (EU), Canada, and Japan for the treatment of Niemann–Pick disease type C [67,68,69] as Zavesca®. The reversible inhibition of ceramide glucosyltransferase is the basis for its type I Gaucher’s disease approval, while the ability of this compound to cross the blood–brain barrier enables the treatment of lysosomal storage diseases with neurological manifestations, thus justifying its use in the management of neurogenerative Niemann–Pick disease type C. Several recent studies have been carried out on this drug for the treatment of Pompe Disease, by examining the combination with a recombinant human acid alpha-glucosidase (ATB200, cipaglucosidase alfa, Pombiliti™, Princeton, NJ, USA) (NCT02675465) [70,71]. A phase III double-blind randomized clinical trial (NCT03729362) to study the efficacy and safety of intravenous ATB200 co-administered with oral AT2221 (N-butyl-DNJ) in adults with Late Onset Pompe Disease has been recently completed [72]. The clinical trial NCT04327973 is still open and is addressed to patients with Infantile-Onset Pompe Disease. Several studies are related to the antiviral activity of N-butyl-DNJ. The effects on HIV-1 infection of this compound were examined [73], along with the combinations with nucleoside analogs (dideoxyinosine, dideoxycytidine, and azidothymidine) [74,75]. Miller et al. (2012) [56] demonstrated that N-butyl-DNJ can reduce production of infectious DENV in an MDMΦ model using blood from dengue-naïve human donors. Moreover, N-butyl-DNJ was studied against SARS-CoV-2 [76]. Rajasekharan et al. (2021) [58] studied miglustat against SARS-CoV-2 and found it was active, suggesting it as a repositional drug for the treatment of COVID-19. El Khoury et al. (2024) [77] reported that N-butyl-DNJ exerts inhibitory effects on SARS-CoV-2 S1 secretion, ACE2 trafficking, and subsequently reduces S1/ACE2 interaction, thus providing a promising therapeutic potential for COVID-19.

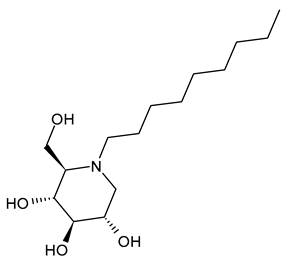

3.1.2. N-Nonyl-DNJ (NN-DNJ or UV-2)

N-Nonyl-DNJ (NN-DNJ or UV-2) bears a nine-carbon linear alkyl side chain and showed a remarkable improvement in potency with respect to N-butyl-DNJ, being 100–200 times more potent in inhibiting hepatitis B virus (HBV) in cell-based assays [39]. N-Nonyl-DNJ also exhibited remarkable inhibitory activity against three influenza A viruses of the H3N2 and H1N1 subtypes in a strain hemagglutinin-dependent manner, indicating its potential to inhibit virus replication and transmission, which was 10-fold more potent than N-butyl-DNJ [61]. It was also studied as an antiviral against filoviruses, EBOV and MARV, in vitro using a yield-plaque assay and in vivo animal models of EBOV and MARV, showing interesting results [44]. N-Nonyl-DNJ can reduce the production of infectious DENV in the MDMΦ model using blood from dengue-naïve human donors, as reported by Miller et al. (2012) [56]. The study by Sayce et al. (2016) [43] confirmed that the class of iminosugars blocks DENV via inhibition of ER α-glucosidases, and not by inhibiting glycolipid processing. N-Nonyl-DNJ was also found to inhibit human papillomavirus (HPV) E5 channel activity in vitro [59]. This compound is also under study for Gaucher disease, acting as a potent N370S β-GCase inhibitor [78], and in vitro in colon cancer cell lines [79].

3.1.3. N-7-Oxadecyl-DNJ (UV-3) (SP116)

N-7-Oxadecyl-DNJ was named as UV-3 and studied against DENV, EBOV, and MARV [14,44,57]. However, it showed generally lower activity than other derivatives. It was less cytotoxic than N-nonyl-DNJ [14].

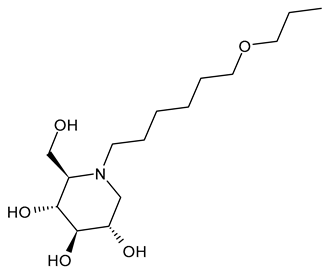

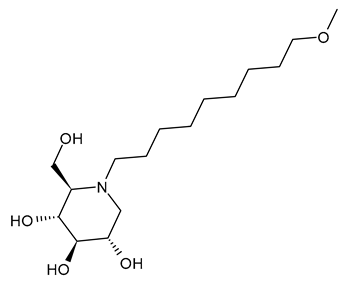

3.1.4. N-9′-Methoxynonyl-1-deoxynojirimycin (MON-DNJ or UV-4)

N-9′-Methoxynonyl-1-deoxynojirimycin (MON-DNJ or UV-4) is probably the most studied and potent inhibitor of α-Glu I and α-Glu II. Perry et al. (2013) [57] studied UV-4 for controlling DENV infection and disease in a mouse model. The antiviral activity of UV-4 was demonstrated against dengue virus serotype 2 (DENV-2) in multiple mouse models. The authors found that administration of UV-4 reduced mortality, as well as viremia and viral RNA in key tissues, and cytokine storm, suggesting its use as a DENV-specific antiviral. In phase I human clinical trials, MON-DNJ was active against EBOV and much more tolerable [44]. Stavale et al. (2015) [80] studied the in vivo therapeutic protection against influenza A (H1N1) oseltamivir-sensitive and resistant viruses exerted by UV-4 in mice, finding that it was highly efficacious via oral gavage against both viruses even if treatment was initiated as late as 48–72 h after infection, with a minimal effective dose of 80–100 mg/kg when administered orally three times daily. Sayce et al. (2021) [81] demonstrated that pathogen-induced inflammation is attenuated by the MON-DNJ via modulation of the unfolded protein response. Clarke et al. (2021) [76] demonstrated that UV-4 prevented SARS-CoV-2-induced cell death and reduced viral replication after 24 h of treatment; however, the antiviral effect was lost after 48 h.

3.1.5. N-9′-Methoxynonyl-1-deoxynojirimycin Hydrochloride (UV-4B)

UV-4B is the hydrochloride salt of UV-4, i.e., N-9′-methoxynonyl-1-deoxynojirimycin hydrochloride [62]. It showed broad-spectrum antiviral activity, and it has recently been tested in humans against DENV infection. In phase I studies, UV-4B has been demonstrated to be well-tolerated in humans with no severe side effects observed after a single dosage of 1000 mg, and pharmacokinetic data indicated a low interindividual variability and good linearity over a wide range of dosages (NCT02061358). In the study by Warfield et al. (2017) [44], UV-4B was tested in a proof-of-concept, nonhuman primate model (rhesus monkeys) of EBOV infection. It failed to yield any survival benefit to macaques infected with EBOV-Makona, despite showing definitive antiviral activity against EBOV in vitro. UV-4B has completed phase I studies in healthy subjects in order to determine the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of this drug (NCT02061358) and the safety and pharmacokinetics of multiple ascending doses to healthy subjects (NCT02696291) [82,83,84]. In these trials, UV-4B proved to be safe at all doses tested up to 1000 mg after administration as an oral solution formulation and showed efficacy against measles and respiratory syncytial virus, suggesting the further development of UV-4B for antiviral activity [63,81,82]. Its activity also extended to another betacoronavirus, HCoV OC43 [17]. Warfield et al. (2020) [85] demonstrated that a single dose of this drug prevented the death of mice infected with lethal doses of influenza or dengue viruses, even when treatment was begun as late as 48 h post-infection. In 2022, Franco et al. [63] showed that UV-4B demonstrated strong anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity in A549-ACE2 cells (EC50 = 4 µM). Franco et al. (2021) [86] also demonstrated the antiviral potential of UV-4B in combination with interferon-alpha against DENV. UV-4B in combination with EIDD-1931, the main circulating metabolite of molnupiravir, has been suggested as a promising therapeutic strategy against SARS-CoV-2, as it inhibits replication of multiple SARS-CoV-2 strains in clinically relevant human cell lines (ACE2-A549 and Caco-2) [87].

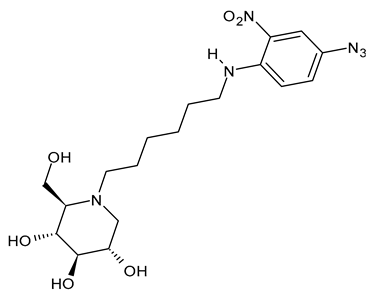

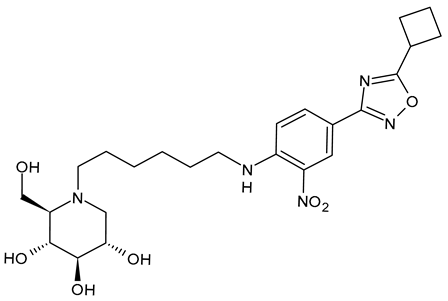

3.1.6. N-[N-(4-Azido-2-nitrophenyl)-6-aminohexyl]-1-deoxynojirimycin (NAP-DNJ or UV-5)

N-[N-(4-Azido-2-nitrophenyl)-6-aminohexyl]-1-deoxynojirimycin (NAP-DNJ or UV-5) is a six-carbon linear side chain containing derivative, which was initially synthesized by Rawlings et al. (2009) [65] as a potential photoaffinity probe for ER GluI and ER GluII. It was then shown to be a highly potent GluI inhibitor (IC50 = 17 nM) in an in vitro assay and proved to be equally effective at inhibiting cellular ER glucosidases in a free oligosaccharide analysis. Caputo et al. (2016) [88] found that it demonstrates high potency in the inhibition of mammalian ER GluII. NAP-DNJ also showed activity against EBOV but was less cytotoxic (CC50 = 350 μM) than NN-DNJ, but more than MON-DNJ. This compound, along with MON-DNJ, was selected to be further studied against EBOV and MARV in vivo, but in vivo efficacy in rodents and nonhuman primates was not demonstrated, as in this case [44]. The synthesis was described by Rawlings et al. [65], with its key step being the reductive alkylation of DNJ, which, in turn, was obtained as described below. Against SARS-CoV-2, N-nonyl-DNJ and NAP-DNJ were more active than MON-DNJ, but also with higher cytotoxicity [14].

3.2. N-Alkyl Derivatives Synthesized in Recent Years

In this section, we summarize the latest N-alkyl derivatives of DNJ studied for their antiviral activities (Table 2).

Table 2.

Antiviral activities of the latest N-alkyl derivatives of DNJ.

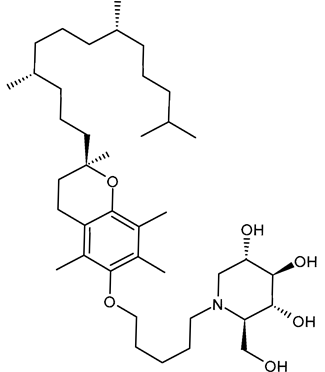

3.2.1. 5′-Tocopheroxypentyl-DNJ (ToP-DNJ, 1)

In 2018, Kiappes et al. [52] reported the synthesis of a new N-alkyl derivative of DNJ exhibiting antiflaviviral activity. The authors selected a form of vitamin E, specifically D-α-tocopherol, to conjugate to DNJ. The resulting compound, 5′-tocopheroxypentyl-DNJ (1, ToP-DNJ), showed a remarkable selectivity for GluII, both for isolated enzymes and in a whole cell system, which has not been reported for any other DNJ derivative. Moreover, it was hypothesized that the non-toxic moiety of vitamin E would be useful for tissue-targeting through accumulation in two body compartments of interest for antiviral therapy. In fact, d-α-tocopherol, after being absorbed in the gut, is stored in the liver, which is the target organ of HCV and a potential reservoir for DENV; it also accumulates in the membranes of immune cells, which are among the target cell types of DENV. Biodistribution studies carried out in Top-DNJ-treated mice demonstrated that, for both oral and intravenous administration routes, the highest amounts were detected in the liver. This liver-targeting property is attributed to its α-tocopherol moiety, too, which naturally directs it to the liver upon absorption. In addition, the IC50 of Top-DNJ for DENV inhibition in MDMΦs was reported to be 12.7 μM. The conjugation with vitamin E also improved plasma and liver half-lives. The synthesis of Top-DNJ was reported by Kiappes et al. [52]. It starts from d-α-tocopherol and makes use of tetra-O-acetyl DNJ, rather than DNJ as it is.

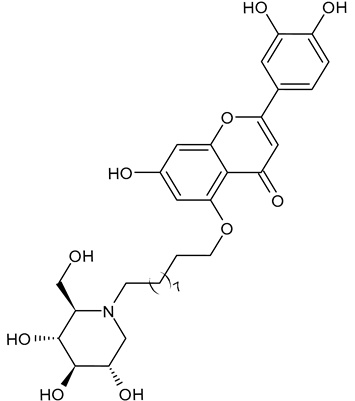

3.2.2. 2-(3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)-7-hydroxy-5-((10-((2R,3R,4R,5S)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-2-(hydroxymethyl)piperidin-1-yl)decyl)oxy)-4H-chromen-4-one (DNJ-20, 2)

In 2025, Liu et al. [94] reported a study on a series of Traditional Chinese Medicine theory-inspired DNJ-flavonoid conjugates as α-glucosidase inhibitors. Interestingly, the flavonoid derivative 2 (DNJ-20) demonstrated high inhibition activity against α-glucosidase (α-Glu I), with an IC50 value of 55.3 μg/mL and also potent and broad-spectrum anti-coronaviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus (PsV), Delta and Omicron BA.5 variants, HCoV-229E and HCoV-OC43, with EC50 values up to 1.49 μM, which is more potent than UV-4. In addition, it had no observable cytotoxicity in HeLa-ACE2, HEK-293T, and Beas-2B cells.

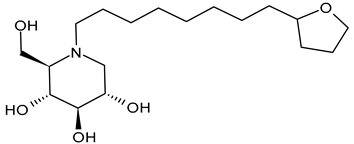

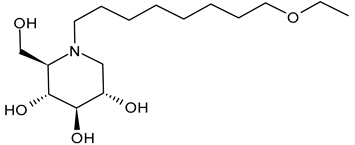

3.2.3. N-8′-(2′′-Tetrahydrofuranyl)octyldeoxynojirimycin (2THO-DNJ or UV-12, 3) and (N-(8′-Ethoxyoctyl)deoxynojirimycin) (EOO-DNJ, 4)

Perera et al. (2022) [60] studied the combination of GluI and GluII inhibition with higher iminosugar in DENV-infected dendritic cells: some DNJ-derivatives (3 or 2THO-DNJ, and 4 or EOO-DNJ, given by Emergent BioSolutions Ltd. and Oxford Glycobiology Institute, respectively) and the previously studied N-nonyl-DNJ. The three compounds inhibited DENV secretion in a dose-dependent manner. ER GluI inhibition, at concentrations of 3.16 μM, was observed for the three compounds, along with a reduction in the specific infectivity of virions that were still secreted, as well as a reduction in DENV-induced tumor necrosis factor alpha secretion. The authors suggested that, beyond the reduction in viral secretion achieved with GluII inhibition, the iminosugar-mediated ER GluI inhibition may give rise to further benefits during DENV infection. The antiviral efficacy of these compounds against HAZV, responsible for Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever virus (CCHFV), is under study by using the surrogate Hazara Virus (HAZV) [95].

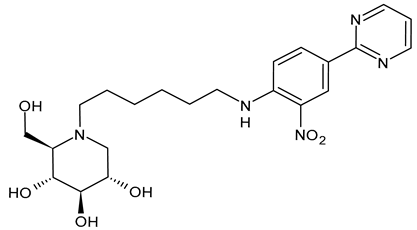

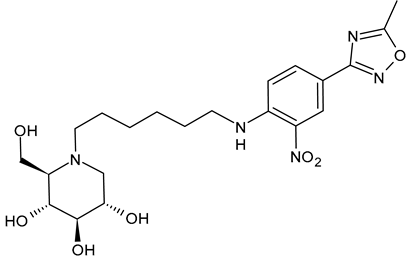

3.2.4. UV-5 like DNJ-Valiolamine Derivatives (EB-0128, 5; EB-0442, 6; EB-0450, 7; and EB-0686, 8)

Karade et al. (2023) [64] reported several DNJ-valiolamine derivatives (UV-4-like and UV-5-like) as ER α-glucosidase I inhibitors for SARS-CoV-2 with EC50 values in the order of the submicromolar (0.42–1.61 μM), indicating that these agents were 2- to 8-fold more potent than UV-4B. The most potent belongs to the series of UV-5-like congeners, and was compound 5 (EB-0128).

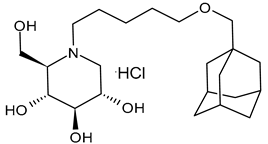

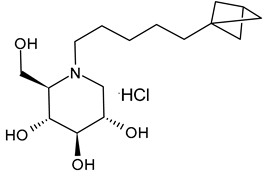

3.2.5. (2R,3R,4R,5S)-1–(5-(Adamantan-1-ylmethoxy)pentyl)-2-(hydroxymethyl)piperidine-3,4,5-triol (9) and (2R,3R,4R,5S)-1–(5-(Bicyclo[1.1.1]pentan-1-yl)pentyl)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-2-(hydroxymethyl)piperidin-1-ium Chloride (10)

Ferjancic et al. (2024) [89] synthesized and studied several derivatives of DNJ and evaluated their activity against SARS-CoV-2. Compounds 9 and 10 were potent anti-SARS-CoV-2 agents. Compound 9, containing the adamantane moiety, had been previously reported [90] as a selective inhibitor of non-lysosomal glucosylceramidases (including β-glucosidase 2) and was regarded as inactive towards ER glucosidases involved in N-glycan trimming [96]. Compound 9 is the most potent iminosugar-based anti-SARS-CoV-2 agent reported thus far [90]. The two compounds act by a host-directed mechanism; thus, they should be more resilient to drug resistance.

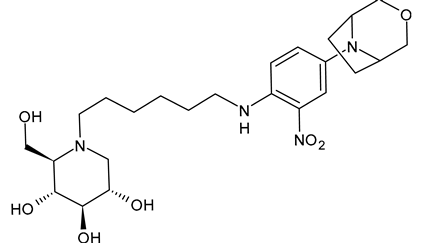

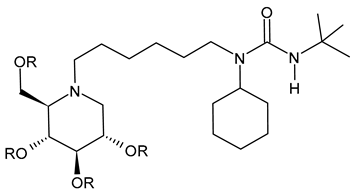

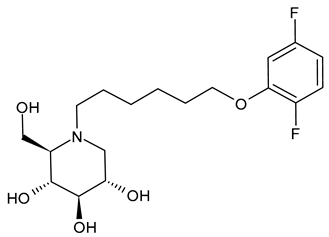

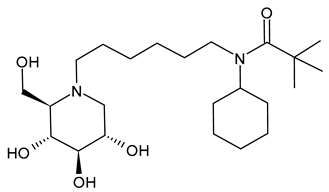

3.2.6. (3-(tert-Butyl)-1-cyclohexyl-1-(6-((2R,3R,4R,5S)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-2-(hydroxymethyl)piperidin-1-yl)hexyl)urea (IHVR-19029 or BSBI-1902, 11); (2R,3R,4R,5S)-1-(6-(2,5-Difluorophenoxy)hexyl)-2-(hydroxymethyl)piperidine-3,4,5-triol, phenylether DNJ (IHVR-11029, 12) and N-Cyclohexyl-N-(6-((2R,3R,4R,5S)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-2-(hydroxymethyl)piperidin-1-yl)hexyl)pivalamide, Pivalamide DNJ (IHVR-17028, 13)

In 2013, Chang et al. [91] reported a study on three small molecules as derivatives of a previously reported compound, CM-10-18 as antiviral agents against representative viruses from viral families causing hemorrhagic fever, specifically EBOV, MARV, BVDV, DENV, and TCRV. The three compounds (IHVR-19029, BSBI-19029, 11; IHVR-11029, 12; and IHVR-17028, 13) showed antiviral activity and significantly reduced the mortality of two of the most pathogenic hemorrhagic fever viruses, EBOV and MARV, in mice when administered via the intraperitoneal injection route. These compounds also showed a favorable adsorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination (ADME) profile in comparison to the parent compound, as they did not significantly inhibit the activity of a panel of representative cytochrome P450 enzymes at 10 μM concentration. However, compounds 11 and 13 have low oral bioavailability, partly due to poor absorption, as shown by a high efflux ratio in the Caco-2 permeability experiment. Compound 11, acting as both GluI and GluII inhibitors, was chosen as a representative compound. In 2017, Ma et al. (2017) [92] reported a study on a prodrug of compound 11, specifically the tetrabutyrate analog. This prodrug demonstrated better in vivo pharmacokinetic properties in mice upon both oral and intravenous administration. Moreover, in vitro evaluation evidenced that the bioconversion of the prodrugs depends on the species: specifically, in mice, the prodrug was converted to 11 in the plasma and liver, while in humans, the conversion occurred mainly in the liver. In a successive paper by the same group, the association of 11 with favipiravir was also studied for Yellow fever and EBOV, with interesting results [97]. More recently, Reyes et al. (2021) [93] reported a study on a compound named ureido-N-hexyl deoxynojirimycin or BSBI-19029, which is likely compound 11, that exhibits high activity against SARS-CoV-2 in A549-ACE2 cells (EC90 = 4 µM). Yesudhas et al. (2021) [98] reported that it has undergone clinical studies for SARS-CoV-2. The activities of compounds 11–13 have been recently summarized and analyzed for their potential in oncology, infectious diseases, and metabolic disorders [7].

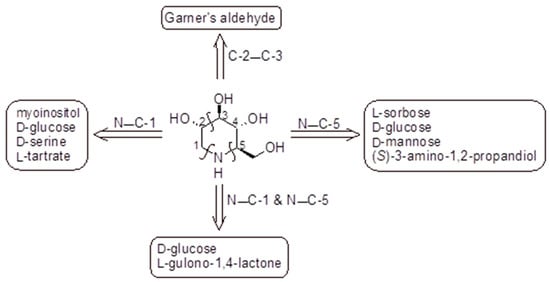

4. Synthesis of Deoxynojirimycin and Its Derivatives

The polyhydroxylated piperidine alkaloid DNJ may be considered as a key intermediate in the synthesis of its N-alkyl derivatives. The active isomer of DNJ is the (+)-DNJ, one out of the possible 16 stereoisomers, and its chemical synthesis is quite challenging due to the needed stereochemical control. The synthetic routes described in the literature and summarized below lead to this isomer (Figure 2). Most of them have been reviewed in several excellent papers [99,100], while more recent works were reviewed by Dahiya et al. (2025) [26]; they mostly rely on the chiral pool approach, including cheap starting materials. In Figure 2 a schematic retrosynthetic analysis is reported to highlight the main disconnections and corresponding starting materials. A relatively low number of elegant asymmetric syntheses were also reported and used either organocatalysis or enzymatic procedures [99,100,101,102]. A couple of preparations involved an optical resolution step [103]. Generally, the preparation of DNJ required numerous steps (from four to more than 10) and orthogonal protecting strategies, with the main involved reactions being reductive amination, intramolecular nucleophilic substitution reactions, ring closing metathesis, Huisgen azide alkene cycloaddition, or transamidification [99]. In most cases, DNJ was obtained in low to moderate overall yields (2–61%) with the most efficient methods starting from chirons and involving some chemoenzymatic steps [99].

Figure 2.

Preparation of DNJ based on the chiral pool approach: retrosynthetic analysis. The key steps closing the piperidine ring are highlighted above the arrows indicating the corresponding chiral starting materials [99,100,104].

A convenient large-scale synthesis of (+)-DNJ hydrochloride from D-glucuronolactone was reported by Best et al. (2010) [105] in an overall yield of up to 72%. Bagal et al. (2010) proposed the synthesis of (+)-DNJ obtained by resolution of (R*S*)-N(1)-benzyl-3-hydroxy-4-benzyloxy-2,3,4,7-tetrahydro-1H-azepine [106]. Iftikhar et al. (2017) [107] reported an improvement in the synthesis of the key step in the synthesis of DNJ, which is the preparation of 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-benzyl-D-glucono-δ-lactam, by using PCC as an oxidant, obtaining DNJ in 85% yield [108]. Alkylation of (+)-DNJ with suitable alkylating reagents gave most of the reported N-alkyl derivatives.

5. Mechanisms of Action Proposed for the GluII Inhibition of Iminosugars

Caputo et al. (2016) [88] examined the crystal structures of GluII in complex with DNJ, evidencing that the endocyclic nitrogen atom of DNJ interacts with D564 and occupies the −1 subsite. This interaction mimics the natural substrate (glucose), effectively inhibiting the enzyme reaction by preventing further catalytic activity. A unique structural feature in ER GluII, the F307 residue in the exclusion loop, confers specificity to these derivatives, reducing off-target effects. The alkyl chain of N-alkyl iminosugars stretches toward the side chains of the conserved residues F307 and F571, suggesting that these compounds act by blocking access to the +1 subsite as well as occupying the −1 subsite with the iminosugar ring. The butyl tail of NB-DNJ displaces the side chain of W525 in the +1 subsite, causing disorder and allowing interactions with residues like F307 and F571. In the case of MON-DNJ, the alkyl chain of the iminosugar is in two main conformations, with the major conformer docking against the exclusion loop F307 and the minor one docking against the hydrophobic side chain of F571, therefore reaching toward the +2 subsite. The longer chain also induces significant conformational changes in the α523–528 loop, making it unstable and enhancing inhibition. The mechanism of antiviral activity of NB-DNJ and NN-DNJ in BVDV and HIV models was investigated by Durantel et al. (2001) [45], who evidenced that the long-alkyl-chain compounds induced a viral envelope glycoprotein homodimer accumulation in the ER. In cells treated with these compounds, the overall quantity of E2 protein increased, which is most noticeable in E2-E2 homodimers. The functionalization of the alkyl chain, as in the DNJ-tocopherol conjugate ToP-DNJ (1), showed selective binding to ER GluII over other glucosidases, including those found in the gut [52]. Its high specificity for ER GluII is attributed to the aromatic tocopherol moiety, which interacts with a hydrophobic exclusion loop near the enzyme’s active site [52].

6. Considerations on Toxicity

Mehta et al. (2002) [41] analyzed the toxicity of fourteen N-alkyl derivatives of DNJ, evidencing that N-7-oxadecyl-DNJ and N-9′-methoxynonyl-1-deoxynojirimycin (MON-DNJ) were less toxic than N-nonyl-DNJ, as evaluated by MTT assay. In the study by Warfield et al. (2017) [44] against EBOV, the toxicity of several N-alkylated derivatives of DNJ was compared. NAP-DNJ was less cytotoxic (CC50 = 350 μM) than NN-DNJ, but more than MON-DNJ. NAP-DNJ, along with MON-DNJ, was selected to be further studied against EBOV and MARV in vivo, but in vivo efficacy in rodents and nonhuman primates was not demonstrated, also in this case. Thus, along with the length of the alkyl chain, lipophilicity must also be considered. The optimal compromise between antiviral efficacy and acceptable cytotoxicity of N-alkyl-DNJ derivatives was a side chain length of 8–9 carbons, and a LogP of approximately 2.8–3.0 [14]. To sum up, in these studies, MON-DNJ (UV-4) was found to be the least cytotoxic, followed by NAP-DNJ (UV-5) and N-oxadecyl-DNJ (UV-3). The compound with the highest toxicity was N-nonyl-DNJ (UV-2). It should be considered that, given the host-targeted mechanism of action of the iminosugars, some cytotoxic effects may occur. Recent compounds have been designed to overcome toxicity, such as the inhibition of the intestinal glucosidases in ToP-DNJ (1), which was designed to minimize the risk of gastrointestinal side effects of the antiviral iminosugar clinical candidates. Moreover, viral escape or adaptive mechanisms can occur, which may influence long-term therapeutic utility. DNJ and N-alkyl DNJ derivatives inhibit ER a-glucosidases, preventing glucose trimming and interaction with calnexin/calreticulin (CNX/CRT), thus representing a therapeutic target in infections by enveloped viruses that require interaction with CNX/CRT for the folding of functional glycoproteins. If folding is incomplete, the glycoprotein is reglucosylated, enabling cyclical interaction with chaperones until the native conformation is achieved, while persistently misfolded proteins enter the ER-associated degradation pathway for proteasomal degradation. However, the detection of triglucosylated viral glycoproteins in the presence of iminosugars, as in the case of studies with some influenza virus strains, demonstrates a pathway whereby partially or misfolded glycoproteins can be produced. In addition, some iminosugars can enhance the secretion of high-mannose glycoproteins, indicating that ER quality control may be bypassed by another enzyme, the Golgi-located endo-a-d-mannosidase, which cleaves the bond between glucose residues and the polymannose chain of the oligosaccharide. Therefore, iminosugar inhibition of oligosaccharide processing by ER Glu could be bypassed by endo-α-d-mannosidase [109].

7. Conclusions

Vaccination alone no longer guarantees global protection against viral threats, such as measles in Canada and North America, and the known COVID-19 pandemic. We can conclude with a sentence taken from Dwek et al. (2026) [110]: “If vaccines falter, broad-spectrum antivirals provide a global shield”. Antivirals offer a crucial complementary approach. However, virus-specific drugs require long times and high costs, often with minimal success, as seen at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Enveloped viruses hijack the protein production machinery of their host to replicate, and their replication/infectivity relies on the correct folding of their surface glycoproteins. This dependence on glycoprotein quality control for the viral replication cycle makes the host ERQC mechanisms an attractive target for the development of host-targeting antiviral agents, which may show broad-spectrum activity and a high genetic barrier to resistance. ER GluI removes the terminal glucose residue of N-linked glycans attached to nascent glycoproteins, enabling them to become substrates of ER Glu II, the main enzyme of the ERQC pathway. The key ERQC protein is GluII, which mediates quality control of the folding of nascent glycoproteins by trimming glucose residues from its substrate glycan Glc1-2Man9GlcNAc2. Broad-spectrum antivirals, such as host-targeting iminosugars, were suggested as a promising alternative [111]. Iminosugars mimic the glucose residue of the native substrate, causing the build-up of misfolded protein in the ER and preventing the secretion of correctly folded glycoproteins. In the case of enveloped virus infection, the inhibition of GluII can inhibit virion secretion or reduce infectivity of secreted virions and has been shown to elicit antiviral effects against a range of enveloped viruses in vitro and in vivo. Among GluII inhibitors, iminosugars derived from DNJ have revealed interesting activity as antivirals. Several compounds belonging to this class have been studied. However, their names generally create a lot of confusion among readers, since different names are used in the literature to refer to a single compound, and we have tried to address this confusion. In summary, the most interesting N-alkyl DNJ derivatives as antivirals in terms of efficacy and low toxicity are represented by MON-DNJ (UV-4) and its hydrochloride salt (UV-4B), which is already in clinical studies, and NAP-DNJ (UV-5). N-nonyl-DNJ (UV-2), although with high antiviral activity, is more toxic than the others. Generally, lengthening the alkyl chain determines an improvement in the antiviral activity. However, the introduction of heteroatoms should be taken into consideration, as it is often in favor of the antiviral activity, despite a shorter alkyl chain. In clinical studies, UV-4B exhibited a good safety profile up to a concentration of 1000 mg after administration as an oral solution formulation and demonstrated efficacy against measles and respiratory syncytial virus, highlighting its potential as a pan-respiratory antiviral targeting viruses most likely to cause pandemics. Generally, efficacy increases with alkyl chain length. Regarding toxicity, the alkyl chain length, along with lipophilicity, must be conceivably considered. The introduction of an oxygen atom generally decreases toxicity, to a greater or lesser extent, depending on its position. LogP values of about 2.8–3.0 seem to be the optimal compromise for obtaining antiviral efficacy and acceptable cytotoxicity. It must be considered that since viruses use cell glycosylation machinery, and therefore cell enzymes, such as ER GluI and GluII, and CNX/CRT chaperons for proper glycoprotein maturation, the interference with cell glycoprotein processing of infected cells remains a critical issue. Trying to limit the effects to the infected cells would be the goal, minimizing side effects, as gastrointestinal. In fact, an important limit of N-alkyl-DNJ derivatives is represented by gastrointestinal toxicity. The ideal antiviral drugs should be selective inhibitors of ER Glu, targeting allosteric sites unique to ER Glu and not substrate analogs targeting the catalytic center that may be similar among different glucosidases (including gut glucosidases). Among the N-alkyl derivatives of DNJ, the DNJ-tocopherol conjugate, ToP-DNJ, in which DNJ is chemically linked to α-tocopherol, a form of vitamin E that is absorbed through the gut and directed to the liver, holds promise as an antiviral agent, given its enzyme and organ selectivity and low gastrointestinal side-effects. Finally, newly studied N-alkyl derivatives of DNJ are analyzed at the end of the paper, highlighting that research in this field still represents a challenge.

8. Future Perspectives

Despite promising in vitro and in vivo data, several critical gaps remain before GluII inhibitors can be convincingly translated into clinical practice. A comprehensive toxicity profile, such as chronic exposure and organ-specific safety, is still missing and will be crucial for long-term use. It could be interesting to further explore whether N-alkyl DNJ iminosugars are preferable to other host-targeted antiviral strategies in terms of efficacy, safety, and resistance potential. Moreover, in vivo quantification of the therapeutic window and pharmacokinetics of the most active analogs has not yet been clearly established. Finally, to define the tissue distribution, precise pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic characterization is needed, as well as metabolic stability and target interaction studies, also in order to distinguish on-target from off-target effects, particularly towards non-ER glucosidases. An approach could be using orally available prodrugs that are hydrolyzed in the circulation and intracellular compartments by ubiquitous esterases, thus potentially avoiding inhibition of gut glucosidases. In addition, the prodrug approach could increase the time of the drug in plasma to achieve an efficacious dose and improve the metabolic stability of the drug to increase the half-life. The prodrug of IHVR-19029 (11) as a tetrabutyrate analog is under study. On the other hand, the improvement in selectivity of DNJ derivatives towards ER Glu, with increased hydrophobicity and ER delivery and distribution, could be another strategy. MON-DNJ was suggested as a new frontier in antiviral pharmacology, offering a paradigm shift that could transform global responses and prevent the catastrophic losses seen during the COVID-19 pandemic. The use of combination therapy of iminosugars with other drugs to enhance antiviral activity could represent a promising strategy for advancing next-generation iminosugars as antivirals. Finally, our consideration on nomenclature issues: a standardized nomenclature should be adopted in future studies, at least when salts of the same compound are concerned. The use of the acronym UV-4B, which refers to the hydrochloride salt of UV-4, is misleading since it might indicate that UV-4B and UV-4 are different compounds, which is not completely true. UV-4B might be given as UV-4 HCl or UV-4 hydrochloride.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C. and G.L.; methodology, D.I. and J.C.; software, M.M.C. and A.M.; validation, P.C. and S.M.; formal analysis, P.C., A.C., and G.L.; investigation, P.L.; resources, J.C.; data curation, M.M.C., A.M., and S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C.; writing—review and editing, P.C. and G.L.; visualization, D.I.; supervision, S.A., P.L., and M.S.S.; project administration, P.C. and S.A.; funding acquisition, M.S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Master “Nutraceutica 4.0 e Nutrizione Clinica” (NutraNu4.0), “Patti Territoriali per l’Alta Formazione per le Imprese”, art. 14-bis, comma 2, D.L. n. 152/2021, CUP:H22C24000120001 (M.S.S.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BVDV | Bovine viral diarrhea virus |

| CC50 | Half maximum cell cytotoxicity |

| CCHFV | Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever virus |

| CNX | Calnexin |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| CRT | Calreticulin |

| DENV | Dengue virus |

| DENV-2 | Dengue virus serotype 2 |

| DNJ | Deoxynojirimycin |

| EC50 | Half maximal effective concentration |

| EBOV | Ebola virus |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| ERQC | Endoplasmic reticulum quality control |

| GluI | α-Glucosidase I |

| GluII | α-Glucosidase II |

| HAZV | Hazara virus |

| HBV | Hepatitis B virus |

| HCV | Hepatitis C virus |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| HPV | Human papillomavirus |

| IC50 | Half maximal inhibitory concentration |

| MARV | Monocyte-derived macrophages |

| PsV | SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus |

| SARS-CoV-1 | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 1 |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| TCRV | Tacaribe virus |

| VSV | Vesicular stomatitis virus |

| WNV | West Nile virus |

References

- Flanagan, J.J.; Rossi, B.; Tang, K.; Wu, X.; Mascioli, K.; Donaudy, F.; Tuzzi, M.R.; Fontana, F.; Cubellis, M.V.; Porto, C.; et al. The Pharmacological Chaperone 1-Deoxynojirimycin Increases the Activity and Lysosomal Trafficking of Multiple Mutant Forms of Acid Alpha-glucosidase. Hum. Mutat. 2009, 30, 1683–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricase, A.F.; Cavalluzzi, M.M.; Catalano, A.; De Bellis, M.; De Palma, A.; Basile, G.; Sinicropi, M.S.S.; Lentini, G. Insights into the Activities and Usefulness of Deoxynojirimycin and Morus alba: A Comprehensive Review. Molecules 2025, 30, 3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datema, R.; Romero, P.A.; Rott, R.; Schwarz, R.T. On the Role of Oligosaccharide Trimming in the Maturation of Sindbis and Influenza Virus. Arch. Virol. 1984, 81, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesinger, S.; Malfer, C.; Schlesinger, M.J. The Formation of Vesicular Stomatitis Virus (San Juan Strain) Becomes Temperature-Sensitive when Glucose Residues are Retained on the Oligosaccharides of the Glycoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 1984, 259, 7597–7601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDowell, W.; Romero, P.A.; Datema, R.; Schwarz, R.T. Glucose Trimming and Mannose Trimming Affect Different Phases of the Maturation of Sindbis Virus in infected BHK Cells. Virology 1984, 161, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datema, R.; Olofsson, S.; Romero, P.A. Inhibitors of Protein Glycosylation and Glycoprotein Processing in Viral Systems. Pharmacol. Ther. 1987, 33, 221–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, T.Z.M.; Wuttiin, Y.; Choocheep, K.; Kumsaiyai, W.; Bunpo, P.; Cressey, R. Exploring Small-Molecule Inhibitors of Glucosidase II: Advances, Challenges, and Therapeutic Potential in Cancer and Viral Infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunkara, P.S.; Bowlin, T.L.; Liu, P.S.; Sjoerdsma, A. Antiretroviral Activity of Castanospermine and Deoxynojirimycin, Specific Inhibitors of Glycoprotein Processing. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1987, 148, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruters, R.A.; Neefjes, J.J.; Tersmette, M.; de Goede, R.E.Y.; Tulp, A.; Huisman, H.G.; Miedema, F.; Ploegh, H.L. Interference with HIV-induced Syncytium Formation and Viral Infectivity by Inhibitors of Trimming Glucosidase. Nature 1987, 330, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papandréou, M.J.; Barbouche, R.; Guieu, R.; Kieny, M.P.; Fenouillet, E. The Alpha-glucosidase Inhibitor 1-Deoxynojirimycin blocks Human Immunodeficiency Virus Envelope Glycoprotein-Mediated Membrane Fusion at the CXCR4 Binding Step. Mol. Pharmacol. 2002, 61, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhushan, G.; Lim, L.; Bird, I.; Chothe, S.K.; Nissly, R.H.; Kuchipudi, S.V. Iminosugars with Endoplasmic Reticulum α-Glucosidase Inhibitor Activity Inhibit ZIKV Replication and Reverse Cytopathogenicity in Vitro. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iftikhar, M.; Lu, Y.; Zhou, M. An Overview of Therapeutic Potential of N-alkylated 1-Deoxynojirimycin Congeners. Carbohydr. Res. 2021, 504, 108317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Shen, Y.; Zhao, L.; Ye, Y. 1-Deoxynojirimycin and Its Derivatives: A Mini Review of the Literature. Curr. Med. Chem. 2021, 28, 628–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Liu, T.; Fan, J.; Xia, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Deng, X. Expanding Horizons of Iminosugars as Broad-Spectrum Anti-Virals: Mechanism, Efficacy and Novel Developments. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2024, 14, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, S.R.; Senwar, K.R.; Sharma, K.N. Alpha-glucosidase in Diabetes Mellitus. In Diabetes Mellitus; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025; Chapter 4; pp. 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.M.; Hyun, C.G. Miglitol, an Oral Antidiabetic Drug, Downregulates Melanogenesis in B16F10 Melanoma Cells through the PKA, MAPK, and GSK3β/β-catenin Signaling Pathways. Molecules 2022, 28, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, W.; Jiao, R.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, T.; Chai, D.; Meng, L.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wu, H.; et al. Miglustat Ameliorates Isoproterenol-Induced Cardiac Fibrosis via Targeting UGCG. Mol. Med. 2025, 31, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, L.; Xu, Y.; He, J.; Huang, G.; Jiang, X.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, R.; Gui, Z. 1-Deoxynojirimycin Derivative Containing Tegafur Induced HCT-116 Cell Apoptosis through Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress Pathway. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2024, 15, 1947–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, A.; Rossi, A.; Stabile, M.; Pinto, G.; De Fino, I.; Melessike, M.; Tamanini, A.; Cabrini, G.; Lippi, G.; Aureli, M.; et al. Assessing the Potential of N-Butyl-l-deoxynojirimycin (L-NBDNJ) in Models of Cystic Fibrosis as a Promising Antibacterial Agent. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2024, 7, 1807–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, S.; Sato, T.; Kako, S.; Tabuchi, M.; Sugita, Y.; Maeda, H.; Hamamura, K.; Miyazawa, K. Miglustat Suppresses Alveolar Bone Resorption in Mouse Models of Periodontitis. J. Hard Tissue Biol. 2025, 34, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Kim, D.; Kim, B.; Joung, D.; Jeon, J.; Kim, T.O.; Youn, H.; Youn, B. UDP-Glucose Ceramide Glucosyltransferase Promotes Radioresistance via Membrane Reorganization to Maintain Redox Balance in Glioblastoma: Molecular Diagnostics. Br. J. Cancer 2025, 133, 1720–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.W.; Chan, K.W.K.; Vasudevan, S.G.; Low, J.G. α-Glucosidase Inhibitors as Broad-Spectrum Antivirals: Current Knowledge and Future Prospects. Antivir. Res. 2025, 238, 106147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonzi, D.S.; Scott, K.A.; Dwek, R.A.; Zitzmann, N. Iminosugar Antivirals: The Therapeutic Sweet Spot. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2017, 45, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.; Block, T.M.; Guo, J.T. Antiviral Therapies Targeting Host ER Alpha-Glucosidases: Current Status and Future Directions. Antivir. Res. 2013, 99, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Li, Z. Medicinal Chemistry Strategies toward Host Targeting Antiviral Agents. Med. Res. Rev. 2020, 40, 1519–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, J.; Kumar, G.; Narula, A.K. The Multifaceted Potential of Azasugars: Synthetic Approaches, Molecular Interactions and Therapeutic Usage. J. Chem. Lett. 2025, 6, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, B.; Mason, P.; Wang, L.; Norton, P.; Bourne, N.; Moriarty, R.; Mehta, A.; Despande, M.; Shah, R.; Block, T. Antiviral Profiles of Novel Iminocyclitol Compounds against Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus, West Nile Virus, Dengue Virus and Hepatitis B Virus. Antiviral Chem. Chemother. 2007, 18, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timokhova, A.V.; Bakinovskii, L.V.; Zinin, A.I.; Popenko, V.I.; Ivanov, A.V.; Rubtsov, P.M.; Kochetkov, S.N.; Belzhelarskaya, S.N. Effect of Deoxynojirimycin Derivatives on Morphogenesis of Hepatitis C Virus. Mol. Biol. 2012, 46, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.J.; Goddard-Borger, E.D. α-Glucosidase Inhibitors as Host-Directed Antiviral Agents with Potential for the Treatment of COVID-19. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2020, 48, 1287–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukushi, M.; Yoshinaka, Y.; Matsuoka, Y.; Hatakeyama, S.; Ishizaka, Y.; Kirikae, T.; Sasazuki, T.; Miyoshi-Akiyama, T. Monitoring of S Protein Maturation in the Endoplasmic Reticulum by Calnexin is Important for the Infectivity of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 11745–11753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brun, J.; Arman, B.Y.; Hill, M.L.; Kiappes, J.L.; Alonzi, D.S.; Makower, L.L.; Witt, K.D.; Gileadi, C.; Rangel, V.; Dwek, R.A.; et al. Assessment of Repurposed Compounds against Coronaviruses Highlights the Antiviral Broad-Spectrum Activity of Host-Targeting Iminosugars and Confirms the Activity of Potent Directly Acting Antivirals. Antivir. Res. 2025, 237, 106123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, S.C.; Robbins, P.W. Synthesis and Processing of Protein-Linked Oligosaccharides In Vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 1979, 254, 4568–4576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, P.A.; Datema, R.; Schwarz, R.T. N-Methyl-1-deoxynojirimycin, a Novel Inhibitor of Glycoprotein Processing, and Its Effect on Fowl Plague Virus Maturation. Virology 1983, 130, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettkamp, H.; Legler, G.; Bause, E. Purification by Affinity Chromatography of Glucosidase I, an Endoplasmic Reticulum Hydrolase Involved in the Processing of Asparagine-linked Oligosaccharides. Eur. J. Biochem. 1984, 142, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.; Van den Broek, L.; Van Boeckel, S.; Ploegh, H.; Bolscher, J. Chemical Modification of the Glucosidase Inhibitor 1-Deoxynojirimycin. Structure-Activity Relationships. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 14504–14510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Block, T.M.; Lu, X.; Platt, F.M.; Foster, G.R.; Gerlich, W.H.; Blumberg, B.S.; Dwek, R.A. Secretion of Human Hepatitis B Virus Is Inhibited by the Imino Sugar N-Butyldeoxynojirimycin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 2235–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, P.; Collin, M.; Karlsson, G.; James, W.; Butters, T.; Davis, S.; Gordon, S.; Dwek, R.; Platt, F. The Glucosidase Inhibitor N-Butyldeoxynojirimycin Inhibits Human Immunodeficiency Virus Entry at the Level of Post-CD4 Binding. J. Virol. 1995, 69, 5791–5797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, T.M.; Lu, X.; Mehta, A.S.; Blumberg, B.S.; Tennant, B.; Ebling, M.; Korba, B.; Lansky, D.M.; Jacob, G.S.; Dwek, R.A. Treatment of Chronic Hepadnavirus Infection in a Woodchuck Animal Model with an Inhibitor of Protein Folding and Trafficking. Nat. Med. 1998, 4, 610–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A.; Zitzmann, N.; Rudd, P.M.; Block, T.M.; Dwek, R.A. α-Glucosidase Inhibitors as Potential Broad Based Anti-Viral Agents. FEBS Lett. 1998, 430, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zitzmann, N.; Mehta, A.S.; Carrouée, S.; Butters, T.D.; Platt, F.M.; McCauley, J.; Blumberg, B.S.; Dwek, R.A.; Block, T.M. Imino Sugars Inhibit the Formation and Secretion of Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus, a Pestivirus Model of Hepatitis C Virus: Implications for the Development of Broad Spectrum Anti-Hepatitis Virus Agents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 11878–11882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, A.; Ouzounov, S.; Jordan, R.; Simsek, E.; Lu, X.; Moriarty, R.M.; Jacob, G.; Dwek, R.A.; Block, T.M. Imino Sugars That Are Less Toxic But More Potent As Antivirals, In Vitro, Compared with N-n-nonyl DNJ. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 2002, 13, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A.; Conyers, B.; Tyrrell, D.L.J.; Walters, K.-A.; Tipples, G.A.; Dwek, R.A.; Block, T.M. Structure-Activity Relationship of a New Class of Anti-Hepatitis B Virus Agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 4004–4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayce, A.C.; Alonzi, D.S.; Killingbeck, S.S.; Tyrrell, B.E.; Hill, M.L.; Caputo, A.T.; Iwaki, R.; Kinami, K.; Ide, D.; Kiappes, J.L.; et al. Iminosugars Inhibit Dengue Virus Production via Inhibition of ER Alpha-Glucosidases—Not Glycolipid Processing Enzymes. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warfield, K.L.; Warren, T.K.; Qiu, X.; Wells, J.; Mire, C.E.; Geisbert, J.B.; Stuthman, K.S.; Garza, N.L.; Van Tongeren, S.A.; Shurtleff, A.C.; et al. Assessment of the Potential for Host-Targeted Iminosugars UV-4 and UV-5 Activity against Filovirus Infections In Vitro and In Vivo. Antivir. Res. 2017, 138, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durantel, D.; Branza-Nichita, N.; Carrouee-Durantel, S.; Butters, T.D.; Dwek, R.A.; Zitzmann, N. Study of the Mechanism of Antiviral Action of Iminosugar Derivatives against Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 8987–8998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.F.; Lee, C.J.; Liao, C.L.; Dwek, R.A.; Zitzmann, N.; Lin, Y.L. Antiviral Effects of an Iminosugar Derivative on Flavivirus Infections. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 3596–3604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howe, J.D.; Smith, N.; Lee, M.J.R.; Ardes-Guisot, N.; Vauzeilles, B.; Désiré, J.; Baron, A.; Blériot, Y.; Sollogoub, M.; Alonzi, D.S.; et al. Novel Imino Sugar α-Glucosidase Inhibitors as Antiviral Compounds. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 4831–4838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, W.; Gill, T.; Wang, L.; Du, Y.; Ye, H.; Qu, X.; Guo, J.T.; Cuconati, A.; Zhao, K.; Block, T.M.; et al. Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of N-alkylated Deoxynojirimycin (DNJ) Derivatives for the Treatment of Dengue Virus Infection. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 6061–6075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.; Pan, X.; Weidner, J.; Yu, W.; Alonzi, D.; Xu, X.; Butters, T.; Block, T.; Guo, J.T.; Chang, J. Inhibitors of Endoplasmic Reticulum Alpha-Glucosidases Potently Suppress Hepatitis C Virus Virion Assembly and Release. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 1036–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans DeWald, L.; Starr, C.; Butters, T.; Treston, A.; Warfield, K.L. Iminosugars: A Host-Targeted Approach to Combat Flaviviridae Infections. Antivir. Res. 2020, 184, 104881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.L.; Tyrrell, B.E.; Zitzmann, N. Mechanisms of Antiviral Activity of Iminosugars against Dengue Virus. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018, 1062, 277–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiappes, J.L.; Hill, M.L.; Alonzi, D.S.; Miller, J.L.; Iwaki, R.; Sayce, A.C.; Caputo, A.T.; Kato, A.; Zitzmann, N. ToP-DNJ, a Selective Inhibitor of Endoplasmic Reticulum α-Glucosidase II Exhibiting Antiflaviviral Activity. ACS Chem. Biol. 2018, 13, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, A.; Iacopetta, D.; Ceramella, J.; Maio, A.C.; Basile, G.; Giuzio, F.; Bonomo, M.G.; Aquaro, S.; Walsh, T.J.; Sinicropi, M.S.; et al. Are Nutraceuticals Effective in COVID-19 and Post-COVID Prevention and Treatment? Foods 2022, 11, 2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, A. COVID-19: Could Irisin Become the Handyman Myokine of the 21st Century? Coronaviruses 2020, 1, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asano, N.; Kato, A.; Watson, A.A. Therapeutic Applications of Sugar-mimicking Glycosidase Inhibitors. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2001, 1, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.L.; Lachica, R.; Sayce, A.C.; Williams, J.P.; Bapat, M.; Dwek, R.; Beatty, P.R.; Harris, E.; Zitzmann, N. Liposome-mediated Delivery of Iminosugars Enhances Efficacy against Dengue Virus In Vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 6379–6386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, S.T.; Buck, M.D.; Plummer, E.M.; Penmasta, R.A.; Batra, H.; Stavale, E.J.; Warfield, K.L.; Dwek, R.A.; Butters, T.D.; Alonzi, D.S.; et al. An Iminosugar with Potent Inhibition of Dengue Virus Infection In Vivo. Antivir. Res. 2013, 98, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasekharan, S.; Bonotto, R.M.; Alves, L.N.; Kazungu, Y.; Poggianella, M.; Martinez-Orellana, P.; Skoko, N.; Polez, S.; Marcello, A. Inhibitors of Protein Glycosylation Are Active against the Coronavirus Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Viruses 2021, 13, 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wetherill, L.F.; Wasson, C.W.; Swinscoe, G.; Kealy, D.; Foster, R.; Griffin, S.; Macdonald, A. Alkyl-imino Sugars Inhibit the Pro-Oncogenic Ion Channel Function of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) E5. Antivir. Res. 2018, 158, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, N.; Brun, J.; Alonzi, D.S.; Tyrrell, B.E.; Miller, J.L.; Zitzmann, N. Antiviral Effects of Deoxynojirimycin (DNJ)-Based Iminosugars in Dengue Virus-Infected Primary Dendritic Cells. Antivir. Res. 2022, 199, 105269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Miller, J.L.; Harvey, D.J.; Gu, Y.; Rosenthal, P.B.; Zitzmann, N.; McCauley, J.W. Strain-specific Antiviral Activity of Iminosugars against Human Influenza A Viruses. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 136–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warfield, K.L.; Plummer, E.M.; Sayce, A.C.; Alonzi, D.S.; Tang, W.; Tyrrell, B.E.; Hill, M.L.; Caputo, A.T.; Killingbeck, S.S.; Beatty, P.R.; et al. Inhibition of Endoplasmic Reticulum Glucosidases is Required for In Vitro and In Vivo Dengue Antiviral Activity by the Iminosugar UV-4. Antivir. Res. 2016, 129, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, E.J.; Warfield, K.L.; Brown, A.N. UV-4B Potently Inhibits Replication of Multiple SARS-CoV-2 Strains in Clinically Relevant Human Cell Lines. Front. Biosci.-Landmark Ed. 2022, 27, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karade, S.S.; Franco, E.J.; Rojas, A.C.; Hanrahan, K.C.; Kolesnikov, A.; Yu, W.; MacKerell, A.D., Jr.; Hill, D.C.; Weber, D.J.; Brown, A.N.; et al. Structure-Based Design of Potent Iminosugar Inhibitors of Endoplasmic Reticulum α-Glucosidase I with Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Activity. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 2744–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawlings, A.J.; Lomas, H.; Pilling, A.W.; Lee, M.J.-R.; Alonzi, D.S.; Rountree, J.S.S.; Jenkinson, S.F.; Fleet, G.W.J.; Dwek, R.A.; Jones, J.H.; et al. Synthesis and Biological Characterisation of Novel N-Alkyl-Deoxynojirimycin α-Glucosidase Inhibitors. ChemBioChem 2009, 10, 1101–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ficicioglu, C. Review of Miglustat for Clinical Management in Gaucher Disease Type 1. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2008, 4, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyseng-Williamson, K.A. Miglustat: A Review of its Use in Niemann-Pick Disease Type C. Drugs 2014, 74, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, M.C.; Vecchio, D.; Prady, H.; Abel, L.; Wraith, J.E. Miglustat for Treatment of Niemann-Pick C Disease: A Randomised Controlled Study. Lancet Neurol. 2007, 6, 765–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, N.; Tiwari, V.K.; Schmidt, R.R. Recent Trends and Challenges on Carbohydrate-Based Molecular Scaffolding: General Consideration toward Impact of Carbohydrates in Drug Discovery and Development. In Carbohydrates in Drug Discovery and Development; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Chapter 1; pp. 1–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishnani, P.; Schoser, B.; Bratkovic, D.; Byrned, B.J.; Clemense, P.R.; Goker-Alpanf, O.; Mingg, X.; Robertsh, M.; Schwenkreisi, P.; Sivakumarj, K.; et al. First-in-human Study of Advanced and Targeted Acid α-glucosidase (AT-GAA) (ATB200/AT2221) in Patients with Pompe Disease: Preliminary Functional Assessment Results from the ATB200-02 Trial. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2019, 126, S86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M.E.; Proskorovsky, I.; Guyot, P.; Shukla, P.; Thibault, N.; Hamed, A.; Pulikottil-Jacob, R.; O’Callaghan, L.; Pollissard, L. An Indirect Treatment Comparison of Avalglucosidase Alfa versus Cipaglucosidase Alfa Plus Miglustat in Patients with Late-Onset Pompe Disease. Adv. Ther. 2025, 42, 5578–5599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoser, B.; Attarian, S.; Graham, R.; Holdbrook, F.; Goldman, M.; Díaz-Manera, J.; ATB200-03 study group. Challenges in Multinational Rare Disease Clinical Studies during COVID-19: Regulatory Assessment of Cipaglucosidase Alfa Plus Miglustat in Adults with Late-Onset Pompe Disease. J. Neurol. 2025, 272, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, G.S.; Bryant, M.L. Iminosugar Glycosylation Inhibitors as Anti-HIV Agents. Perspect. Drug Discov. Design 1993, 1, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratner, L.E.E.; Heyden, N.V. Mechanism of Action of N-Butyl Deoxynojirimycin in Inhibiting HIV-1 Infection and Activity in Combination with Nucleoside Analogs. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 1993, 9, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischl, M.A.; Resnick, L.; Coombs, R.; Kremer, A.B.; Pottage, J.C., Jr.; Fass, R.J.; Fife, K.H.; Powderly, W.G.; Collier, A.C.; Aspinall, R.L.; et al. The Safety and Efficacy of Combination N-Butyl-deoxynojirimycin (SC-48334) and Zidovudine in Patients with HIV-1 Infection and 200–500 CD4 Cells/mm. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 1994, 7, 139–147. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, E.C.; Nofchissey, R.A.; Ye, C.; Bradfute, S.B. The Iminosugars Celgosivir, Castanospermine and UV-4 Inhibit SARS-CoV-2 Replication. Glycobiology 2021, 31, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Khoury, M.; Wanes, D.; Lynch-Miller, M.; Hoter, A.; Naim, H.Y. Glycosylation Modulation Dictates Trafficking and Interaction of SARS-CoV-2 S1 Subunit and ACE2 in Intestinal Epithelial Caco-2 Cells. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borie-Guichot, M.; Tran, M.L.; Garcia, V.; Oukhrib, A.; Rodriguez, F.; Turrin, C.O.; Levade, T.; Génisson, Y.; Bellereau, S.; Dehoux, C. Multivalent Pyrrolidines Acting as Pharmacological Chaperones Against Gaucher Disease. Bioorg. Chem. 2024, 146, 107295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montebugnoli, T.; Grootaert, C.; Bordoni, A.; Rajković, A.; Alderweireldt, E.; Rombaut, J.; De Maeseneire, S.L.; Van Camp, J.; De Mol, M.L. Food Iminosugars and Related Synthetic Derivatives Shift Energy Metabolism and Induce Structural Changes in Colon Cancer Cell Lines. Foods 2025, 14, 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavale, E.J.; Vu, H.; Sampath, A.; Ramstedt, U.; Warfield, K.L. In Vivo Therapeutic Protection against Influenza A (H1N1) Oseltamivir-Sensitive and Resistant Viruses by the Iminosugar UV-4. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayce, A.C.; Martinez, F.O.; Tyrrell, B.E.; Perera, N.; Hill, M.L.; Dwek, R.A.; Miller, J.L.; Zitzmann, N. Pathogen-induced Inflammation Is Attenuated by the Iminosugar MON-DNJ via Modulation of the Unfolded Protein Response. Immunology 2021, 164, 587–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callahan, M.; Treston, A.M.; Lin, G.; Smith, M.; Kaufman, B.; Khaliq, M.; Evans DeWald, L.; Spurgers, K.; Warfield, K.L.; Lowe, P.; et al. Randomized Single Oral Dose Phase 1 Study of Safety, Tolerability, and Pharmacokinetics of Iminosugar UV-4 Hydrochloride (UV-4B) in Healthy Subjects. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwek, R.A.; Bell, J.I.; Feldmann, M.; Zitzmann, N. Host-Targeting Oral Antiviral Drugs to Prevent Pandemics. Lancet 2022, 399, 1381–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.-S.; Zhou, Y.; Takagi, T.; Kameoka, M.; Kawashita, N. Dengue Virus and Its Inhibitors: A Brief Review. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2018, 66, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warfield, K.L.; Alonzi, D.S.; Hill, J.C.; Caputo, A.T.; Roversi, P.; Kiappes, J.L.; Sheets, N.; Duchars, M.; Dwek, R.A.; Biggins, J.; et al. Targeting Endoplasmic Reticulum α-Glucosidase I with a Single-Dose Iminosugar Treatment Protects against Lethal Influenza and Dengue Virus Infections. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 4205–4214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, E.; de Mello, C.P.; Brown, A. Antiviral Evaluation of UV-4B and Interferon-Alpha Combination Regimens against Dengue Virus. Viruses 2021, 13, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco, E.J.; Drusano, G.L.; Hanrahan, K.C.; Warfield, K.L.; Brown, A.N. Combination Therapy with UV-4B and Molnupiravir Enhances SARS-CoV-2 Suppression. Viruses 2023, 15, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caputo, A.T.; Alonzi, D.S.; Marti, L.; Reca, I.B.; Kiappes, J.L.; Struwe, W.B.; Cross, A.; Basu, S.; Lowe, E.D.; Darlot, B.; et al. Structures of Mammalian ER α-Glucosidase II Capture the Binding Modes of Broad-Spectrum Iminosugar Antivirals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E4630–E4638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferjancic, Z.; Bihelovic, F.; Vulovic, B.; Matovic, R.; Trmcic, M.; Jankovic, A.; Pavlovic, M.; Djurkovic, F.; Prodanovic, R.; Djelmas, A.D.; et al. Development of Iminosugar-based Glycosidase Inhibitors as Drug Candidates for SARS-CoV-2 Virus Via Molecular Modelling and In Vitro Studies. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2024, 39, 2289007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennekes, T.; Lang, B.; Leeman, M.; Van Der Marel, G.A.; Smits, E.; Weber, M.; Van Wiltenburg, J.; Wolberg, M.; Aerts, J.M.F.G.; Overkleeft, H.S. Large-scale Synthesis of the Glucosylceramide Synthase Inhibitor N-[5-(adamantan-1-yl-methoxy)-pentyl]-1-Deoxynojirimycin. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2008, 12, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Warren, T.K.; Zhao, X.; Gill, T.; Guo, F.; Wang, L.; Comunale, M.A.; Du, Y.; Alonzi, D.S.; Yu, W.; et al. Small Molecule Inhibitors of ER Alpha-Glucosidases Are Active against Multiple Hemorrhagic Fever Viruses. Antiviral. Res. 2013, 98, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Wu, S.; Zhang, X.; Guo, F.; Yang, K.; Guo, J.; Su, Q.; Lu, H.; Lam, P.; Li, P.; et al. Ester Prodrugs of IHVR-19029 with Enhanced Oral Exposure and Prevention of Gastrointestinal Glucosidase Interaction. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 8, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, H.; Du, Y.; Zhou, T.; Xie, X.; Shi, P.Y.; Weiss, S.; Block, T.M. Glucosidase Inhibitors Suppress SARS-CoV-2 in Tissue Culture and May Potentiate. bioRxiv 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Li, Z.A.; Zhou, Y.Z.; Wang, S.L.; Chen, Z.P.; Liu, S.X.; Zhan, P.; Zhou, Y.J.; Xia, Z.X.; Deng, X. TCM Theory-Inspired Discovery of DNJ-Flavonoid Conjugates as Broad-Spectrum Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Agents by Primarily Targeting ER-Associated Glycoprotein Folding Process. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 290, 117582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrrell, B.E.; Kumar, A.; Gangadharan, B.; Alonzi, D.; Brun, J.; Hill, M.; Bharucha, T.; Bosworth, A.; Graham, V.; Dowall, S.; et al. Exploring the Potential of Iminosugars as Antivirals for Crimean-Congo Haemorrhagic Fever Virus, Using the Surrogate Hazara Virus: Liquid-Chromatography-Based Mapping of Viral N-Glycosylation and in Vitro Antiviral Assays. Pathogens 2023, 12, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overkleeft, H.S.; Renkema, G.H.; Neele, J.; Vianello, P.; Hung, I.O.; Strijland, A.; van der Burg, A.M.; Koomen, G.J.; Pandit, U.K.; Aerts, J.M. Generation of Specific Deoxynojirimycin-Type Inhibitors of the Non-Lysosomal Glucosylceramidase. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 26522–26527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhang, X.; Soloveva, V.; Warren, T.; Guo, F.; Wu, S.; Lu, H.; Guo, J.; Su, Q.; Shen, H.; et al. Enhancing the Antiviral Potency of ER α-Glucosidase Inhibitor IHVR-19029 against Hemorrhagic Fever Viruses In Vitro and In Vivo. Antivir. Res. 2018, 150, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yesudhas, D.; Srivastava, A.; Gromiha, M.M. COVID-19 Outbreak: History, Mechanism, Transmission, Structural Studies and Therapeutics. Infection 2021, 49, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, Y. The Synthesis and Biological Activity of Glycosidase Inhibitors. J. Synth. Org. Chem. 1991, 49, 846–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhara, D.; Dhara, A.; Bennett, J.; Murphy, P.V. Cyclisations and Strategies for Stereoselective Synthesis of Piperidine Iminosugars. Chem. Rec. 2021, 21, 2958–2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.S.; Lee, H.Y.; Jung, Y.H. Stereoselective Synthesis of D-1-deoxynojirimycin and its Stereoisomers. Heterocycles 2007, 71, 1787–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikota, N.; Hirano, J.I.; Gamage, R.; Nakagawa, H.; Hama-Inaba, H. Improved Synthesis of 1-Deoxynojirimycin and Facile Synthesis of its Stereoisomers from (S)-Pyroglutamic Acid Derivative. Heterocycles 1997, 46, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaller, C.; Vogel, P.; Jäger, V. Total Syntheses of (+)-and (−)-1-Deoxynojirimycin (1, 5-dideoxy-1,5-imino D-and L-glucitol) and of (+)-and (−)-1-Deoxyidonojirimycin (1,5-dideoxy-1,5-imino D-and L-iditol) via furoisoxazoline-3-aldehydes. Carbohydr. Res. 1998, 314, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somfai, P.; Marchand, P.; Torsell, S.; Lindström, U.M. Asymmetric Synthesis of (+)-1-Deoxynojirimycin and (+)-Castanospermine. Tetrahedron 2003, 59, 1293–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, D.; Wang, C.; Weymouth-Wilson, A.C.; Clarkson, R.A.; Wilson, F.X.; Nash, R.J.; Miyauchi, S.; Kato, A.; Fleet, G.W. Looking Glass Inhibitors: Scalable Syntheses of DNJ, DMDP, and (3R)-3-Hydroxy-L-Bulgecinine from D-Glucuronolactone and of L -DNJ, L-DMDP, and (3S)-3-Hydroxy-D-bulgecinine from L-Glucuronolactone. DMDP Inhibits β-Glucosidases and β-Galactosidases whereas L-DMDP is a Potent and Specific Inhibitor of α-Glucosidases. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2010, 21, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagal, S.K.; Davies, S.G.; Lee, J.A.; Roberts, P.M.; Scott, P.M.; Thomson, J.E. Syntheses of the Enantiomers of 1-Deoxynojirimycin and 1-Deoxyaltronojirimycin Via Chemo--and Diastereoselective Olefinic Oxidation of Unsaturated Amines. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 8133–8146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iftikhar, M.; Wang, L.; Fang, Z. Synthesis of 1-Deoxynojirimycin: Exploration of Optimised Conditions for Reductive Amidation and Separation of Epimers. J. Chem. Res. 2017, 41, 460–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iftikhar, M.; Zhou, M.; Lu, Y. An Overview of Debenzylation Methods to Obtain 1-Deoxynojirimycin (DNJ). Mini-Rev. Org. Chem. 2021, 18, 1037–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrrell, B.E.; Sayce, A.C.; Warfield, K.L.; Miller, J.L.; Zitzmann, N. Iminosugars: Promising Therapeutics for Influenza Infection. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 43, 521–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwek, R.A.; Feldmann, M.; Fotinou, C.; Zitzmann, N. If Vaccines Falter, Broad-Spectrum Antivirals Provide a Global Shield. Lancet 2026, 407, 25–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beran, R.K.; Vijjapurapu, A.; Nair, V.; Du Pont, V. Host-targeted Antivirals as Broad-spectrum Inhibitors of Respiratory Viruses. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2025, 73, 101492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.