Comparing Proton Transfer Reaction (PTR) and Adduct Ionization Mechanism (AIM) for the Study of Volatile Organic Compounds

Abstract

1. Introduction

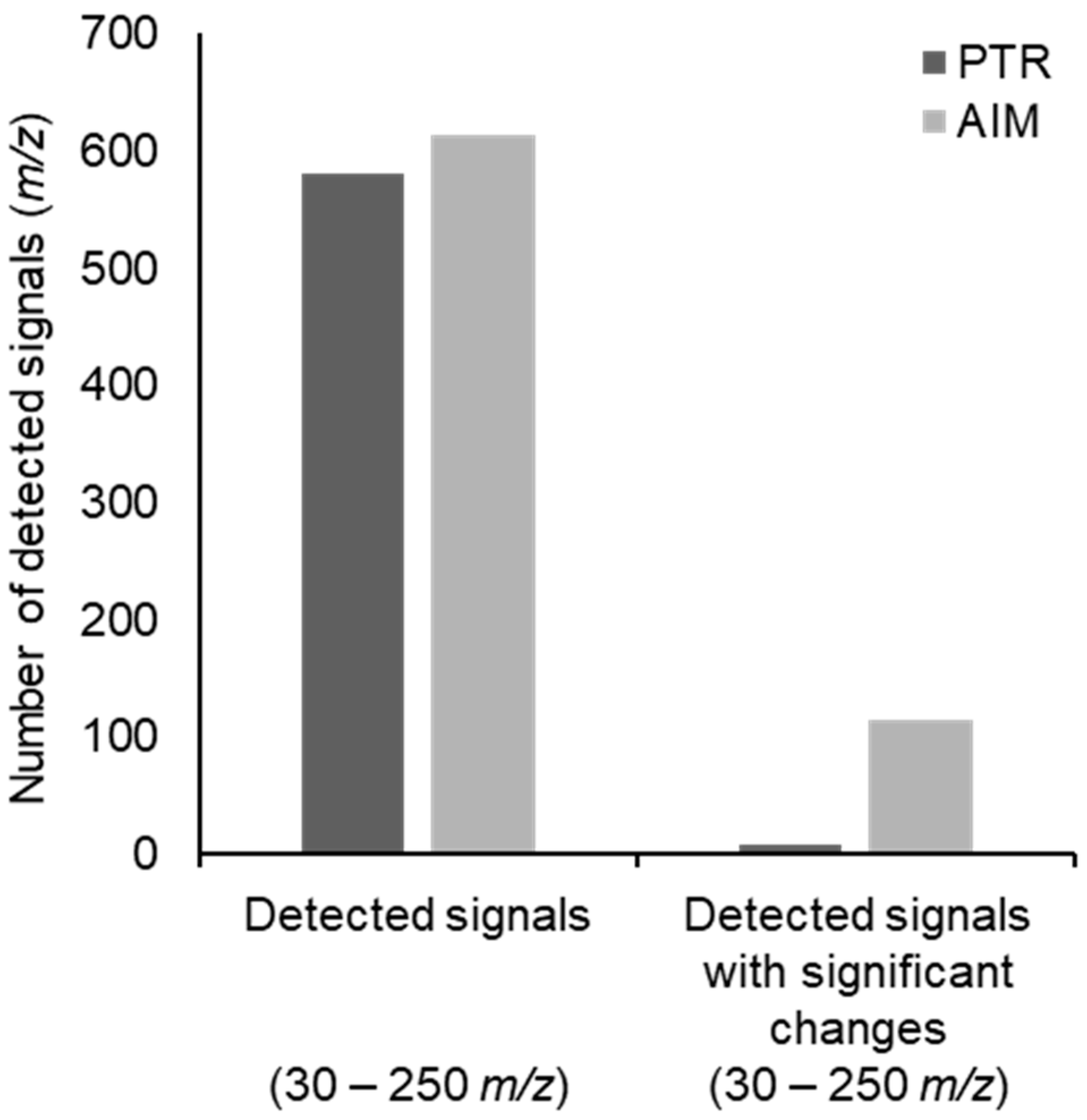

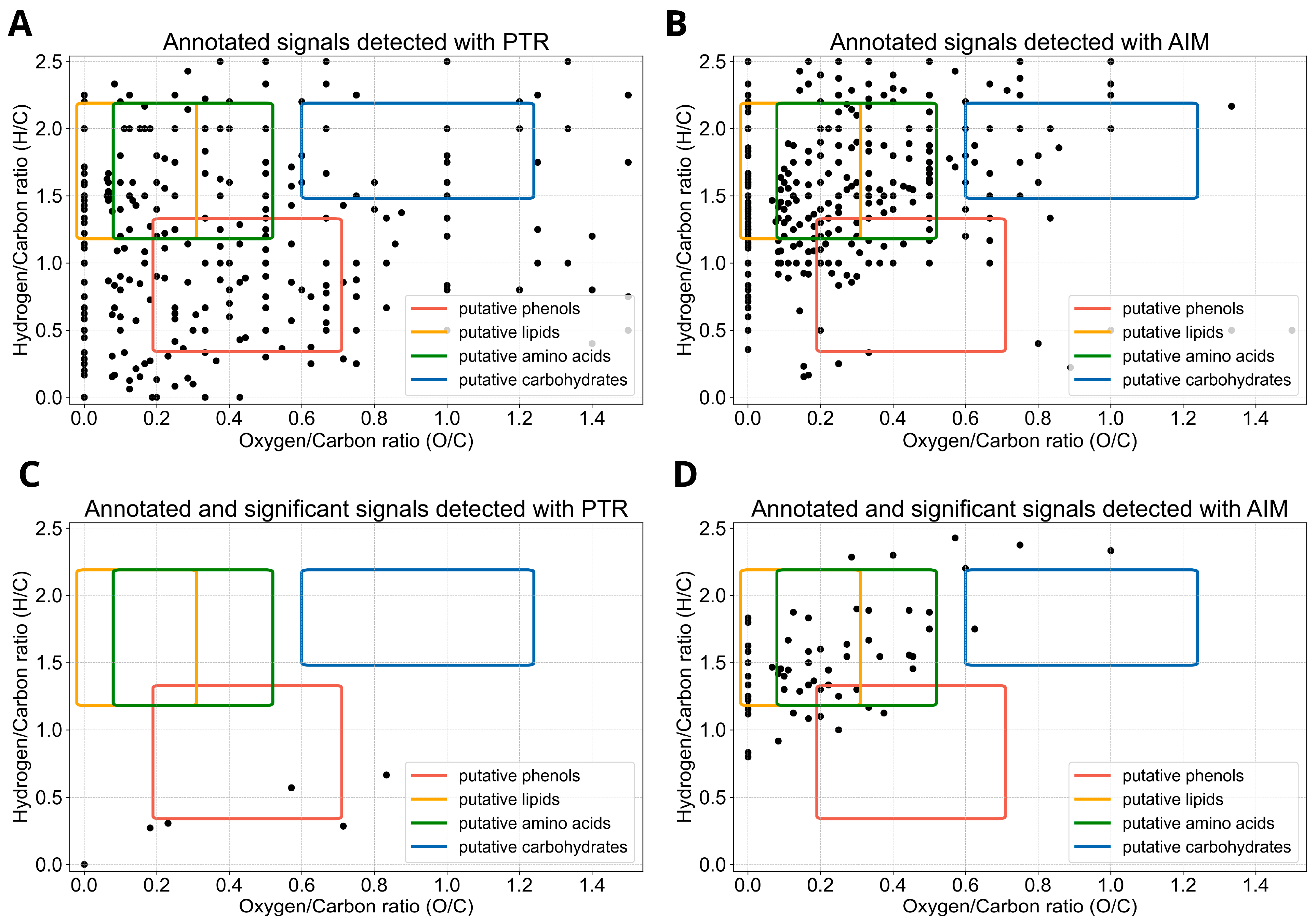

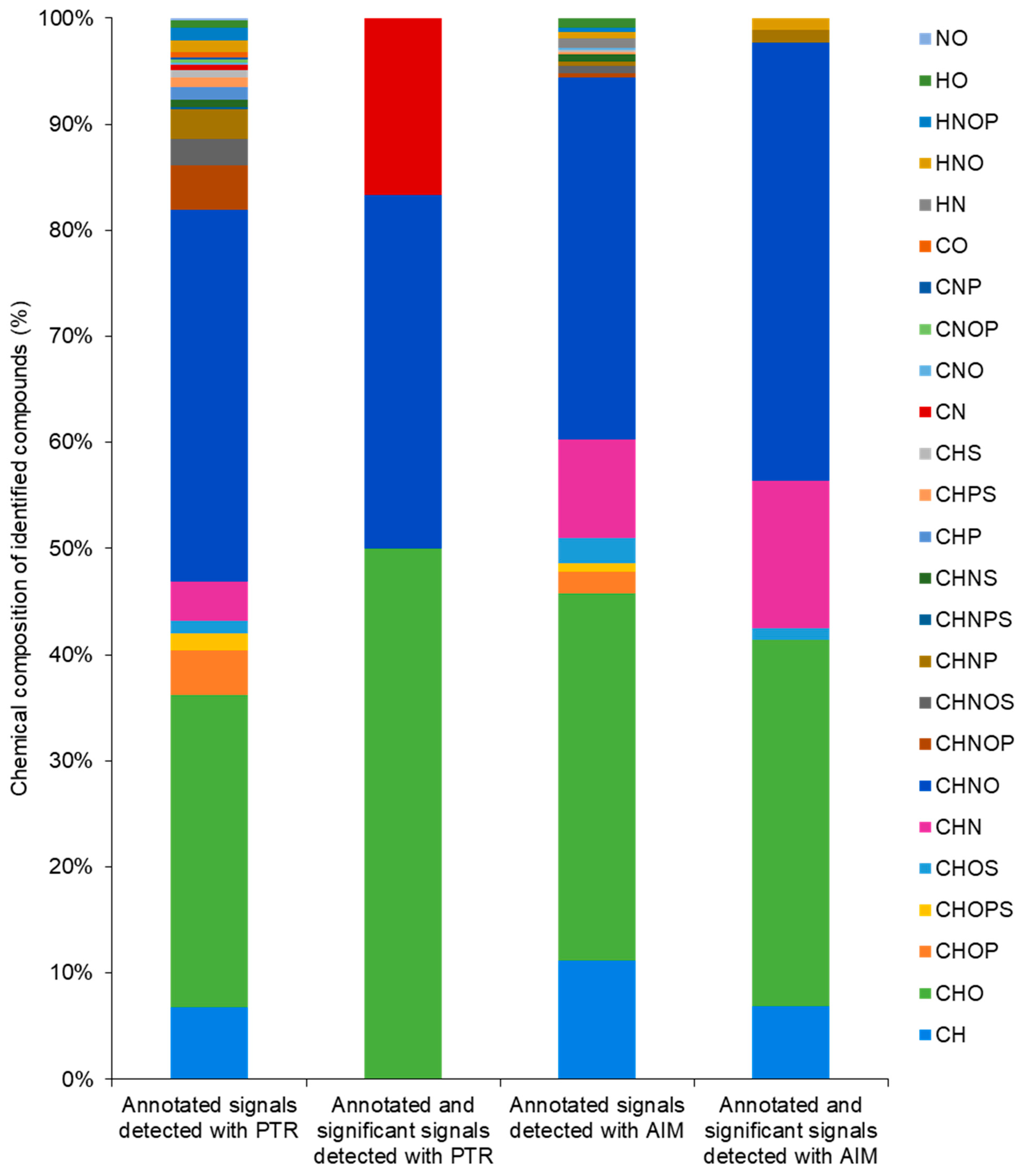

2. Results

3. Discussion

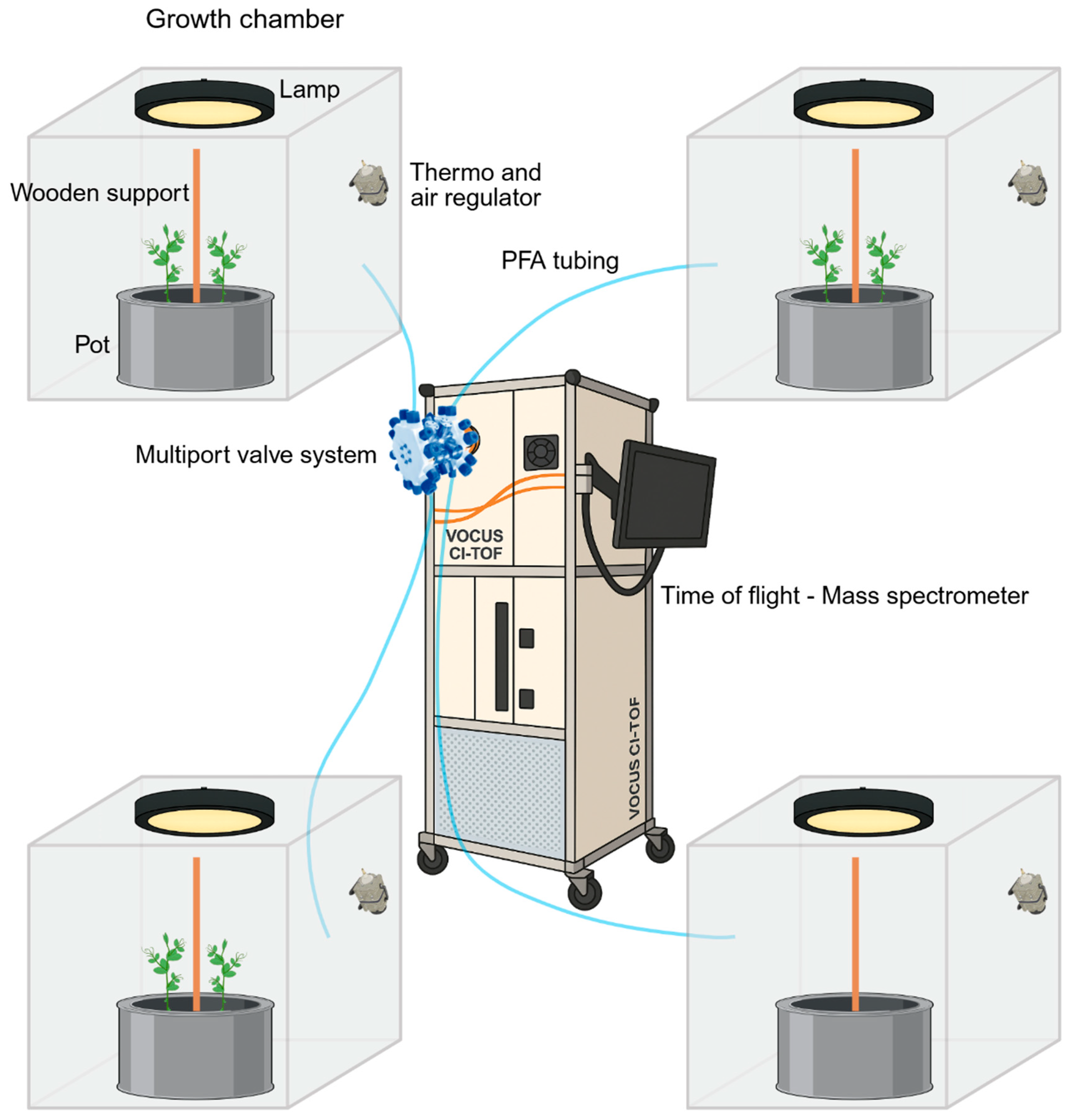

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Biological Materials and Growth Conditions

4.2. Volatile Organic Compounds Sampling and Analysis

4.2.1. Volatile Organic Compounds Analysis with the PTR-TOF-MS

4.2.2. Volatile Organic Compounds Analysis with the AIM-TOF-MS

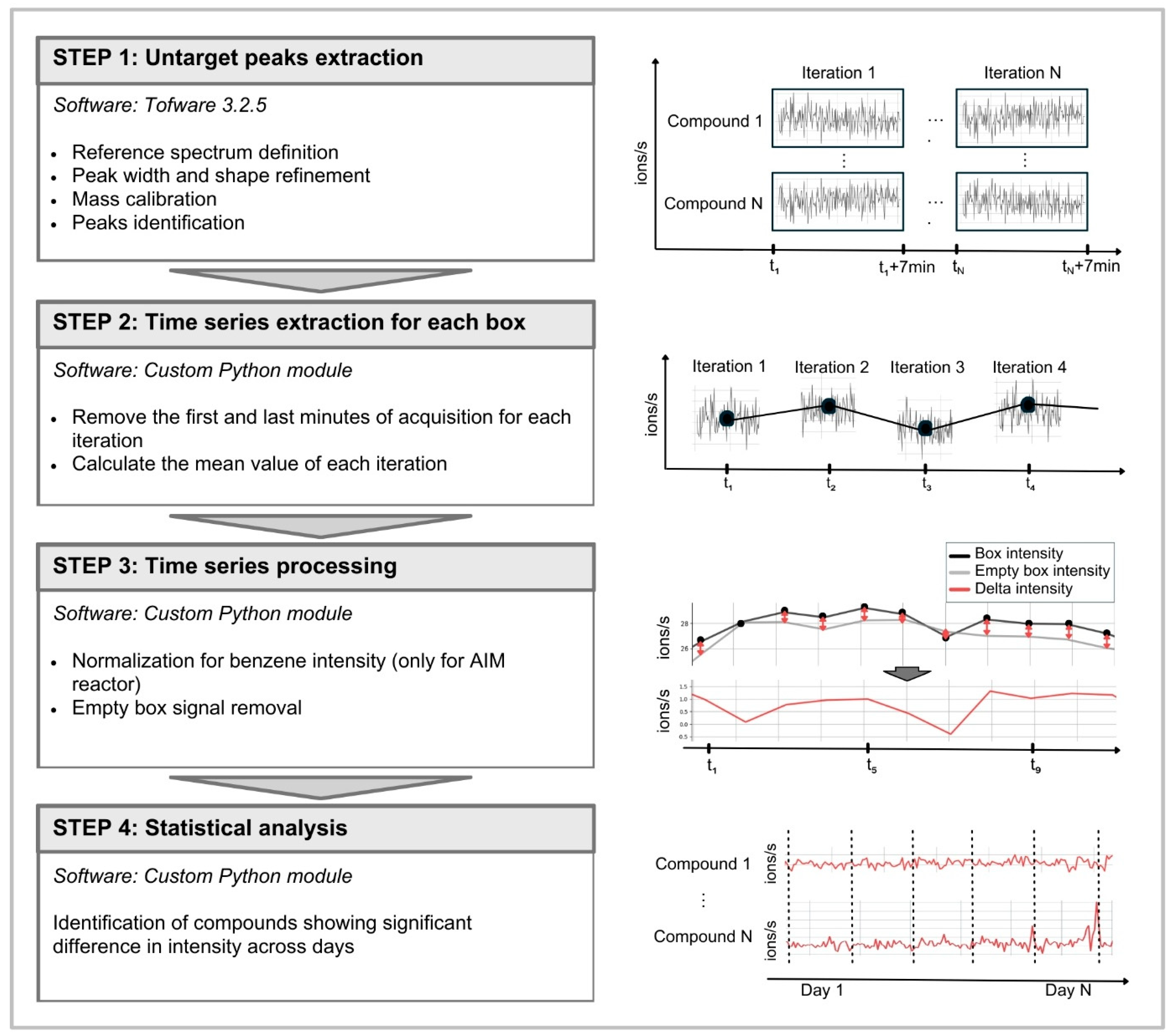

4.3. Data Processing, Statistical Analysis, and Annotation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baldwin, I.T. Plant Volatiles. Curr. Biol. 2010, 20, R392–R397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudareva, N.; Klempien, A.; Muhlemann, J.K.; Kaplan, I. Biosynthesis, Function and Metabolic Engineering of Plant Volatile Organic Compounds. New Phytol. 2013, 198, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierik, R.; Ballaré, C.L.; Dicke, M. Ecology of Plant Volatiles: Taking a Plant Community Perspective. Plant Cell Environ. 2014, 37, 1845–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosset, A.; Blande, J.D. Volatile-Mediated Plant–Plant Interactions: Volatile Organic Compounds as Modulators of Receiver Plant Defence, Growth, and Reproduction. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 511–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, R.; Ryu, C.-M. Social Networking in Crop Plants: Wired and Wireless Cross-Plant Communications. Plant Cell Environ. 2021, 44, 1095–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loreto, F.; D’Auria, S. How Do Plants Sense Volatiles Sent by Other Plants? Trends Plant Sci. 2022, 27, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonato, B.; Peressotti, F.; Guerra, S.; Wang, Q.; Castiello, U. Cracking the Code: A Comparative Approach to Plant Communication. Commun. Integr. Biol. 2021, 14, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudareva, N.; Negre, F.; Nagegowda, D.A.; Orlova, I. Plant Volatiles: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2006, 25, 417–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karban, R.; Wetzel, W.C.; Shiojiri, K.; Ishizaki, S.; Ramirez, S.R.; Blande, J.D. Deciphering the Language of Plant Communication: Volatile Chemotypes of Sagebrush. New Phytol. 2014, 204, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Midzi, J.; Jeffery, D.W.; Baumann, U.; Rogiers, S.; Tyerman, S.D.; Pagay, V. Stress-Induced Volatile Emissions and Signalling in Inter-Plant Communication. Plants 2022, 11, 2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arimura, G.; Uemura, T. Cracking the Plant VOC Sensing Code and Its Practical Applications. Trends Plant Sci. 2025, 30, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coatsworth, P.; Gonzalez-Macia, L.; Collins, A.S.P.; Bozkurt, T.; Güder, F. Continuous Monitoring of Chemical Signals in Plants under Stress. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2022, 7, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Zheng, C.; Wang, J. Challenges and Applications of Volatile Organic Compounds Monitoring Technology in Plant Disease Diagnosis. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2023, 237, 115540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, A.; Mueller, M.B.; Kalske, A.; Chautá, A. Volatile-Mediated Plant–Plant Communication and Higher-Level Ecological Dynamics. Curr. Biol. 2023, 33, R519–R529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, M.; Wu, M.; Li, X.; Liu, H.; Niu, N.; Li, S.; Chen, L. Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) from Plants: From Release to Detection. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 158, 116872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDougall, S.; Bayansal, F.; Ahmadi, A. Emerging Methods of Monitoring Volatile Organic Compounds for Detection of Plant Pests and Disease. Biosensors 2022, 12, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aina, O.; Bakare, O.O.; Fadaka, A.O.; Keyster, M.; Klein, A. Plant Biomarkers as Early Detection Tools in Stress Management in Food Crops: A Review. Planta 2024, 259, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfender, J.-L.; Glauser, G.; Boccard, J.; Rudaz, S. MS-Based Plant Metabolomic Approaches for Biomarker Discovery. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2009, 4, 1934578X0900401019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majchrzak, T.; Wojnowski, W.; Rutkowska, M.; Wasik, A. Real-Time Volatilomics: A Novel Approach for Analyzing Biological Samples. Trends Plant Sci. 2020, 25, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksenov, A.A.; Novillo, A.V.G.; Sankaran, S.; Fung, A.G.; Pasamontes, A.; Martinelli, F.; Cheung, W.H.K.; Ehsani, R.; Dandekar, A.M.; Davis, C.E. Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) for Noninvasive Plant Diagnostics. In Pest Management with Natural Products; Beck, J.J., Coats, J.R., Duke, S.O., Koivunen, M.E., Eds.; ACS Symposium Series; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; Volume 1141, pp. 73–95. ISBN 978-0-8412-2900-6. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, R.M.C.; Wildt, J.; Kappers, I.F.; Bouwmeester, H.J.; Hofstee, J.W.; Henten, E.J.V. Detection of Diseased Plants by Analysis of Volatile Organic Compound Emission. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2011, 49, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, R.M.C.; Hofstee, J.W.; Wildt, J.; Verstappen, F.W.A.; Bouwmeester, H.; Van Henten, E.J. Induced Plant Volatiles Allow Sensitive Monitoring of Plant Health Status in Greenhouses. Plant Signal. Behav. 2009, 4, 824–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tholl, D.; Hossain, O.; Weinhold, A.; Röse, U.S.R.; Wei, Q. Trends and Applications in Plant Volatile Sampling and Analysis. Plant J. 2021, 106, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.; Ramasamy, R. Current and Prospective Methods for Plant Disease Detection. Biosensors 2015, 5, 537–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lytou, A.E.; Panagou, E.Z.; Nychas, G.-J.E. Volatilomics for Food Quality and Authentication. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2019, 28, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagliero, C.; Mastellone, G.; Marengo, A.; Bicchi, C.; Sgorbini, B.; Rubiolo, P. Analytical Strategies for In-Vivo Evaluation of Plant Volatile Emissions—A Review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2021, 1147, 240–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tholl, D.; Boland, W.; Hansel, A.; Loreto, F.; Röse, U.S.R.; Schnitzler, J.-P. Practical Approaches to Plant Volatile Analysis. Plant J. 2006, 45, 540–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, R.S.; Monks, P.S.; Ellis, A.M. Proton-Transfer Reaction Mass Spectrometry. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 861–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappellin, L.; Loreto, F.; Aprea, E.; Romano, A.; Del Pulgar, J.; Gasperi, F.; Biasioli, F. PTR-MS in Italy: A Multipurpose Sensor with Applications in Environmental, Agri-Food and Health Science. Sensors 2013, 13, 11923–11955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krechmer, J.; Lopez-Hilfiker, F.; Koss, A.; Hutterli, M.; Stoermer, C.; Deming, B.; Kimmel, J.; Warneke, C.; Holzinger, R.; Jayne, J.; et al. Evaluation of a New Reagent-Ion Source and Focusing Ion–Molecule Reactor for Use in Proton-Transfer-Reaction Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 12011–12018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansel, A.; Jordan, A.; Holzinger, R.; Prazeller, P.; Vogel, W.; Lindinger, W. Proton Transfer Reaction Mass Spectrometry: On-Line Trace Gas Analysis at the Ppb Level. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. Ion Process. 1995, 149–150, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, M.; Pospisilova, V.; Frege, C.; Perrier, S.; Bansal, P.; Jorga, S.; Sturm, P.; Thornton, J.A.; Rohner, U.; Lopez-Hilfiker, F. Evaluation of a Reduced-Pressure Chemical Ion Reactor Utilizing Adduct Ionization for the Detection of Gaseous Organic and Inorganic Species. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2024, 17, 5887–5901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewnowski, A.; Conrad, Z. Pulse Crops: Nutrient Density, Affordability, and Environmental Impact. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1438369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulgoni, V.L.; Keast, D.R.; Drewnowski, A. Development and Validation of the Nutrient-Rich Foods Index: A Tool to Measure Nutritional Quality of Foods. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 1549–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, W.J.; Foster, L.M.; Tyler, R.T. Review of the Health Benefits of Peas (Pisum sativum L.). Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, S3–S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, T.; Deka, S.C. Potential Health Benefits of Garden Pea Seeds and Pods: A Review. Legume Sci. 2021, 3, e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, R.; Fatima, F.; Altemimi, A.B.; Bashir, N.; Sipra, H.M.; Hassan, S.A.; Mujahid, W.; Shehzad, A.; Abdi, G.; Aadil, R.M. Bridging Sustainability and Industry through Resourceful Utilization of Pea Pods- A Focus on Diverse Industrial Applications. Food Chem. X 2024, 23, 101518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanthakumar, P.; Klepacka, J.; Bains, A.; Chawla, P.; Dhull, S.B.; Najda, A. The Current Situation of Pea Protein and Its Application in the Food Industry. Molecules 2022, 27, 5354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAOSTAT. 2024. Available online: http://faostat.fao.org (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Smýkal, P.; Aubert, G.; Burstin, J.; Coyne, C.J.; Ellis, N.T.H.; Flavell, A.J.; Ford, R.; Hýbl, M.; Macas, J.; Neumann, P. Pea (Pisum sativum L.) in the Genomic Era. Agronomy 2012, 2, 74–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avesani, S.; Castiello, U.; Ravazzolo, L.; Bonato, B. Volatile Organic Compounds in Pea Plants: A Comprehensive Review. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1591829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Riva, M.; Rantala, P.; Heikkinen, L.; Daellenbach, K.; Krechmer, J.E.; Flaud, P.-M.; Worsnop, D.; Kulmala, M.; Villenave, E.; et al. Terpenes and Their Oxidation Products in the French Landes Forest: Insights from Vocus PTR-TOF Measurements. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2020, 20, 1941–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahim, J.R.; Attia, E.Z.; Kamel, M.S. The Phenolic Profile of Pea (Pisum sativum): A Phytochemical and Pharmacological Overview. Phytochem. Rev. 2019, 18, 173–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, T.; Aires, A.; Cosme, F.; Bacelar, E.; Morais, M.C.; Oliveira, I.; Ferreira-Cardoso, J.; Anjos, R.; Vilela, A.; Gonçalves, B. Bioactive (Poly)Phenols, Volatile Compounds from Vegetables, Medicinal and Aromatic Plants. Foods 2021, 10, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeppesen, M.J.; Powers, R. Multiplatform Untargeted Metabolomics. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2023, 61, 628–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliete, B.; Lubbers, S.; Fournier, C.; Jeandroz, S.; Saurel, R. Effect of Biotic Stress on the Presence of Secondary Metabolites in Field Pea Grains. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2022, 102, 4942–4948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Davis, T.S.; Eigenbrode, S.D. Aphid Behavioral Responses to Virus-Infected Plants Are Similar despite Divergent Fitness Effects. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2014, 153, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horril, M.; Maguire, R.; Ingram, J. The Contribution of Pulses to Net Zero in the UK. Environ. Res. Food Syst. 2024, 1, 022001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagnari, F.; Maggio, A.; Galieni, A.; Pisante, M. Multiple Benefits of Legumes for Agriculture Sustainability: An Overview. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2017, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavi, A.; Vermeuel, M.P.; Novak, G.A.; Bertram, T.H. The Sensitivity of Benzene Cluster Cation Chemical Ionization Mass Spectrometry to Select Biogenic Terpenes. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2018, 11, 3251–3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avesani, S.; Lazazzara, V.; Robatscher, P.; Oberhuber, M.; Perazzolli, M. Volatile Linalool Activates Grapevine Resistance against Downy Mildew with Changes in the Leaf Metabolome. Curr. Plant Biol. 2023, 35–36, 100298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockman, S.A.; Roden, E.V.; Hegeman, A.D. Van Krevelen Diagram Visualization of High Resolution-Mass Spectrometry Metabolomics Data with OpenVanKrevelen. Metabolomics 2018, 14, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laszakovits, J.R.; MacKay, A.A. Data-Based Chemical Class Regions for Van Krevelen Diagrams. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2022, 33, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adrian, M.; Lucio, M.; Roullier-Gall, C.; Héloir, M.C.; Trouvelot, S.; Daire, X.; Kanawati, B.; Lemaître-Guillier, C.; Poinssot, B.; Gougeon, R.; et al. Metabolic Fingerprint of Ps3-Induced Resistance of Grapevine Leaves against Plasmopara Viticola Revealed Differences in Elicitor-Triggered Defenses. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Avesani, S.; Bonato, B.; Simonetti, V.; Guerra, S.; Ravazzolo, L.; Gjinaj, G.; Dadda, M.; Castiello, U. Comparing Proton Transfer Reaction (PTR) and Adduct Ionization Mechanism (AIM) for the Study of Volatile Organic Compounds. Molecules 2026, 31, 402. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31030402

Avesani S, Bonato B, Simonetti V, Guerra S, Ravazzolo L, Gjinaj G, Dadda M, Castiello U. Comparing Proton Transfer Reaction (PTR) and Adduct Ionization Mechanism (AIM) for the Study of Volatile Organic Compounds. Molecules. 2026; 31(3):402. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31030402

Chicago/Turabian StyleAvesani, Sara, Bianca Bonato, Valentina Simonetti, Silvia Guerra, Laura Ravazzolo, Gabriela Gjinaj, Marco Dadda, and Umberto Castiello. 2026. "Comparing Proton Transfer Reaction (PTR) and Adduct Ionization Mechanism (AIM) for the Study of Volatile Organic Compounds" Molecules 31, no. 3: 402. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31030402

APA StyleAvesani, S., Bonato, B., Simonetti, V., Guerra, S., Ravazzolo, L., Gjinaj, G., Dadda, M., & Castiello, U. (2026). Comparing Proton Transfer Reaction (PTR) and Adduct Ionization Mechanism (AIM) for the Study of Volatile Organic Compounds. Molecules, 31(3), 402. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31030402