Abstract

Investigation of the roots of Tripterygium wilfordii Hook. f. resulted in the isolation of nine sesquiterpene pyridine alkaloids (SPAs), including four previously undescribed compounds 1–4. The structures of all compounds were elucidated by extensive spectroscopic analysis, including NMR and HRESIMS. In particular, compound 1 was found to possess an unprecedented cage-like ether moiety, representing the first report of such a structural feature within this class of alkaloids. All isolated compounds were evaluated for their anti-inflammatory activity using a lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced RAW264.7 macrophage model. Compounds 1, 2, and 4 exhibited significant inhibition of nitric oxide (NO) production, with IC50 values of 7.14 ± 1.89, 8.55 ± 0.37, and 14.76 ± 0.39 μM. Furthermore, compounds 1 and 2 suppressed the secretion of key pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, in the same cellular model. These results not only enhanced the structural diversity of SPAs identified from T. wilfordii, but also highlight their potential as promising anti-inflammatory lead compounds.

1. Introduction

Tripterygium wilfordii Hook. f., a plant historically used in traditional Chinese medicine, is widely employed for treating rheumatoid arthritis, nephritis, and other autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Modern pharmacological investigations have established that its bioactivities, including anti-inflammatory, immunosuppressive, and antitumor effects, are primarily attributed to a diverse array of secondary metabolites, such as diterpenoids, triterpenoids, and alkaloids. Among them, diterpenoids exhibit potent activities but are often associated with considerable toxicity, which limited their broader clinical application. In contrast, SPAs have attracted increasing research interest due to their unique structures, well-documented pharmacological profiles, and relatively lower toxicity. SPAs from T. wilfordii are characterized by a dihydro-β-agarofuran skeleton esterified with various nicotinic acid derivatives, leading to structurally diverse and highly substituted natural products. Based on the nature of the acylating groups, they are classified into subtypes such as wilfordate (W), evoninate (E), iso-wilfordate (IW), and iso-evoninate (IE) types [1,2,3,4]. Previous study reported that the alkaloids possess a range of pharmacological activities, including anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, and multidrug resistance-reversing effects, highlighting their potential as promising lead compounds for drug development [5,6,7,8,9]. Although numerous SPAs have been isolated from T. wilfordii, its chemical diversity and pharmacological potential remain incompletely explored.

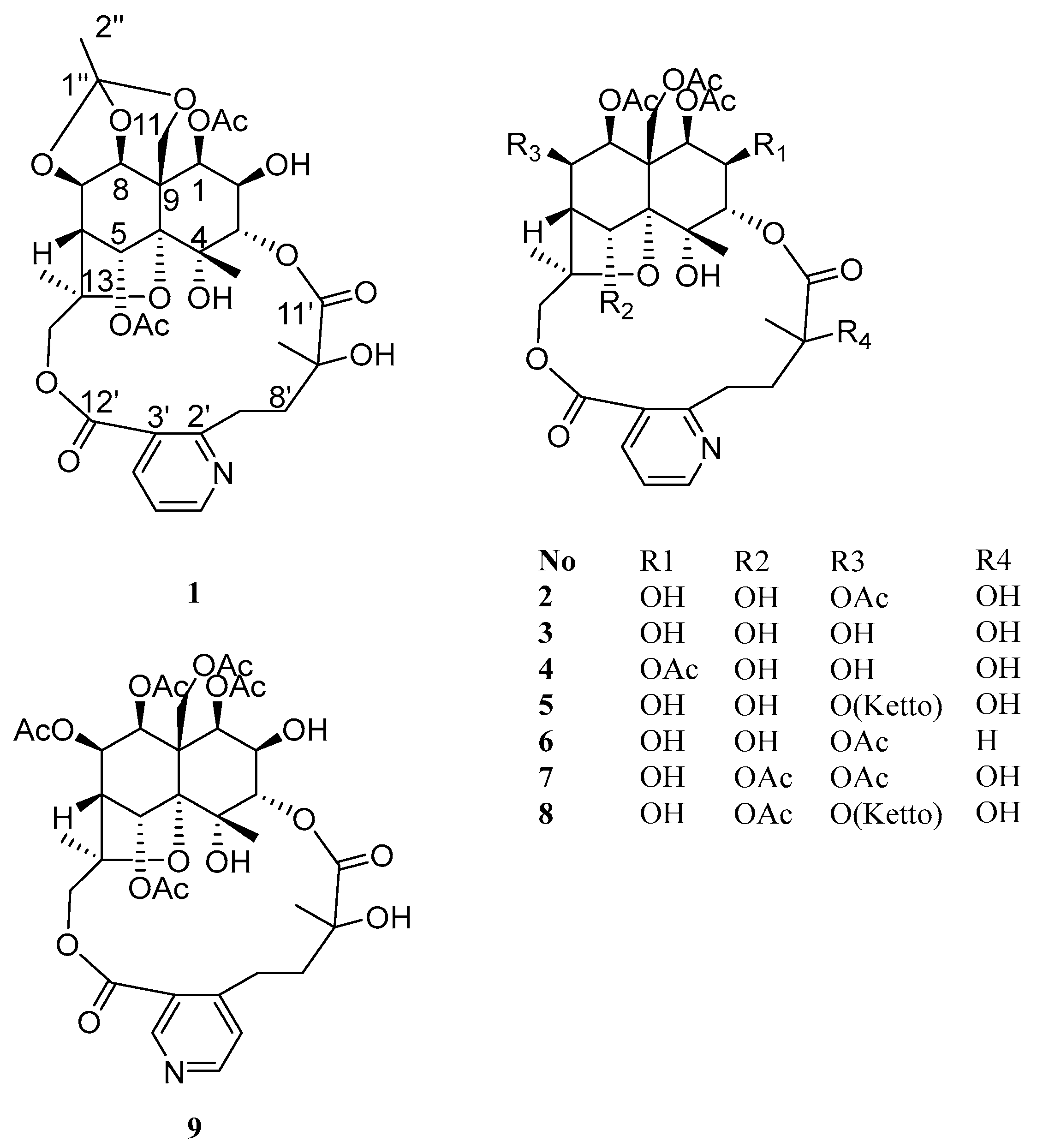

To further investigate structurally novel and biologically active alkaloids, a systematic phytochemical study was conducted on the alkaloid fraction of the roots of T. wilfordii. This study resulted in the isolation of nine SPAs (1–9), including four new compounds—wilforidatine A (1), 2,5-dideacetylalatusinine (2), 2,5,7-trideacetylalatusinine (3), and 5,7-dideacetylalatusinine (4)—along with five known analogues—tripterygiumine T (5), 5-deacetylwilforjine (6), tripfordine A (7), chiapenine ES-IV (8), and wilfordsuine (9) (Figure 1). Notably, compound 1 exhibited an unprecedented cage-like ether moiety formed by the linkage of C-7, C-8, and C-11 with a 1,1,1-trihydroxyethane unit, representing a novel structural archetype within the class of alkaloids [2]. Evaluation of the anti-inflammatory activity of the isolated compounds using a lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced RAW264.7 macrophage model demonstrated that compounds 1, 2, 4, 5 and 9 significantly inhibited nitric oxide (NO) production, with IC50 values of 7.14 ± 1.89, 8.55 ± 0.37, 14.76 ± 0.39, 4.88 ± 0.92 and 2.43 ± 0.18 μM, respectively. Furthermore, compounds 1 and 2 markedly suppressed the secretion of inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, in the same cellular model. These findings not only enhanced the structural diversity of SPAs from T. wilfordii but also highlighted their potential as promising anti-inflammatory lead compounds worthy of further investigation.

Figure 1.

Structures of compounds 1–9.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Structural Elucidation

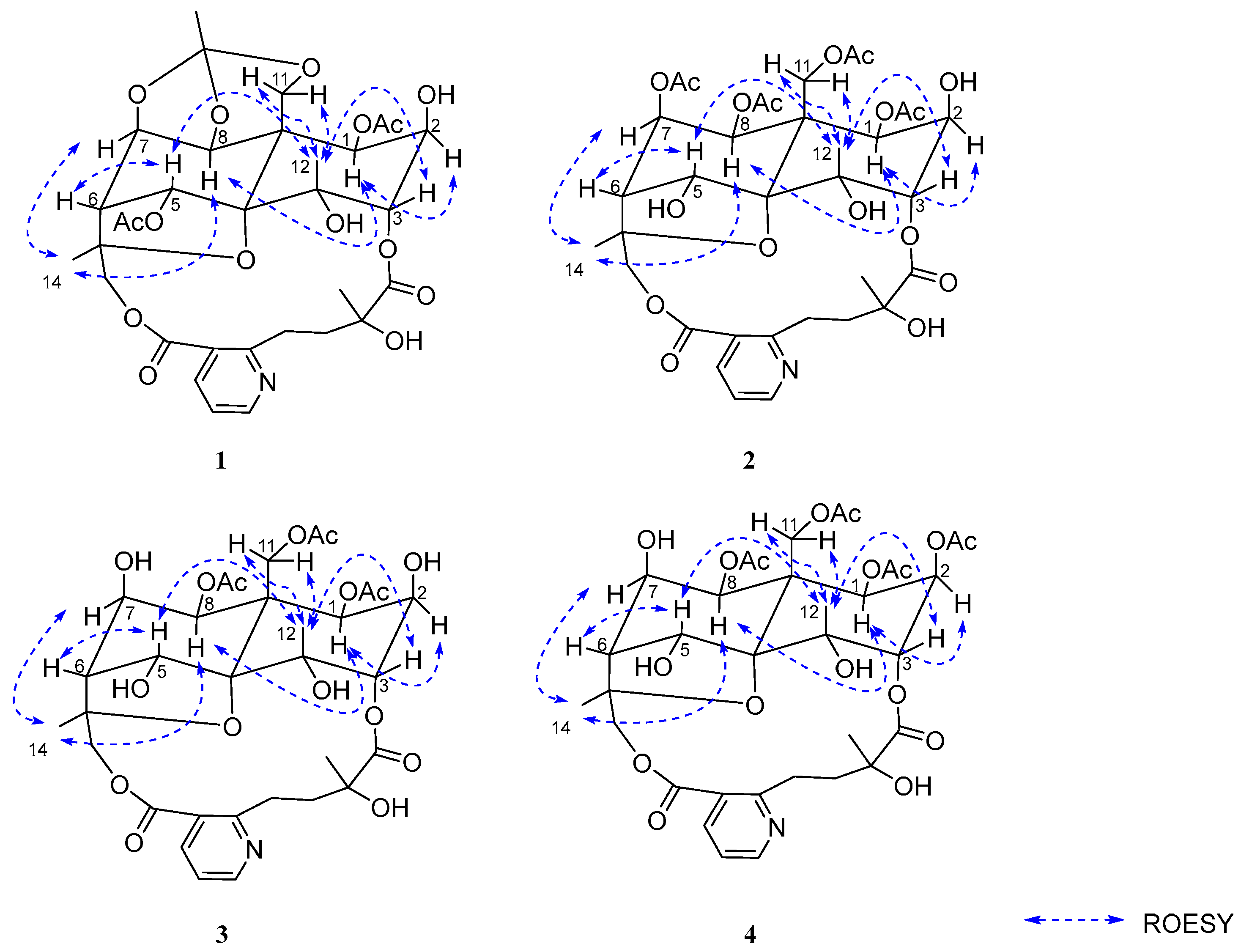

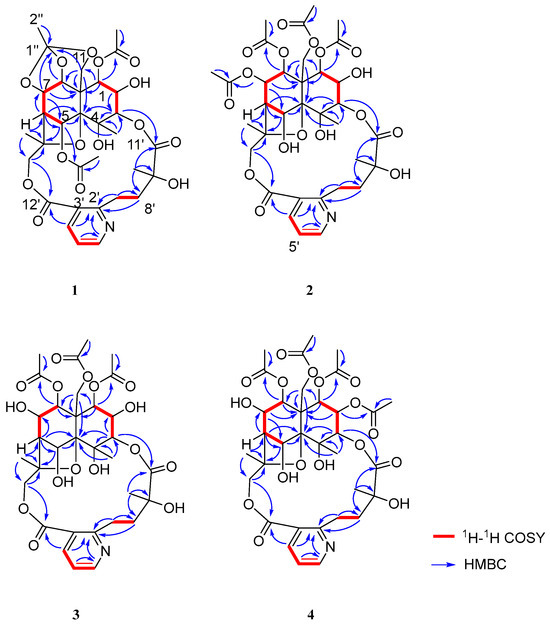

Compound 1 was obtained as a white amorphous powder, soluble in chloroform and methanol. HR-ESI-MS exhibited a pseudo-molecular ion peak at m/z 678.2382 [M + H]+ (calcd C32H39O15N, 678.2393), consistent with 11 degrees of unsaturation. Analysis of its NMR data (Table 1 and Table 2) indicated that 1 was a 9′-hydroxylated W-type SPA, structurally related to 2. Key differences included: (1) the presence of only two acetyl groups in 1, two fewer than in 2; (2) a significant downfield shift in the H-5 methine signal from δH 5.26 to δH 6.60 (1H, brs); (3) the appearance of an additional low-field quaternary carbon signal at δC 119.9 and a methyl group at δH 1.65 (3H, s) in the NMR spectra of 1. In the HMBC spectrum, correlations from H-1 and H-5 to a carbonyl carbon at δC 169.6 (1-OAc) confirmed the presence of two acetyl groups attached to C-1 and C-5, respectively. Furthermore, key HMBC correlations from the methyl protons (δH 1.65) to the quaternary carbon (δC 119.9), and from H-7, H-8, and H-11 to the same carbon, suggested that C-7, C-8, and C-11 were connected via ether bonds to this quaternary carbon (Figure 2), which is itself linked to a methyl group, forming an unprecedented cage-like ether moiety. Literature consultation revealed that this structural feature, while known in compounds from Meliaceae family plants [10], was reported here for the first time in T. wilfordii.

Table 1.

1H-NMR data of compounds 1–4 (CDCl3, 600 MHz).

Table 2.

13C-NMR data of compounds 1–4 (CDCl3, 150 MHz).

Figure 2.

The key 1H-1H COSY and HMBC correlations of 1–4.

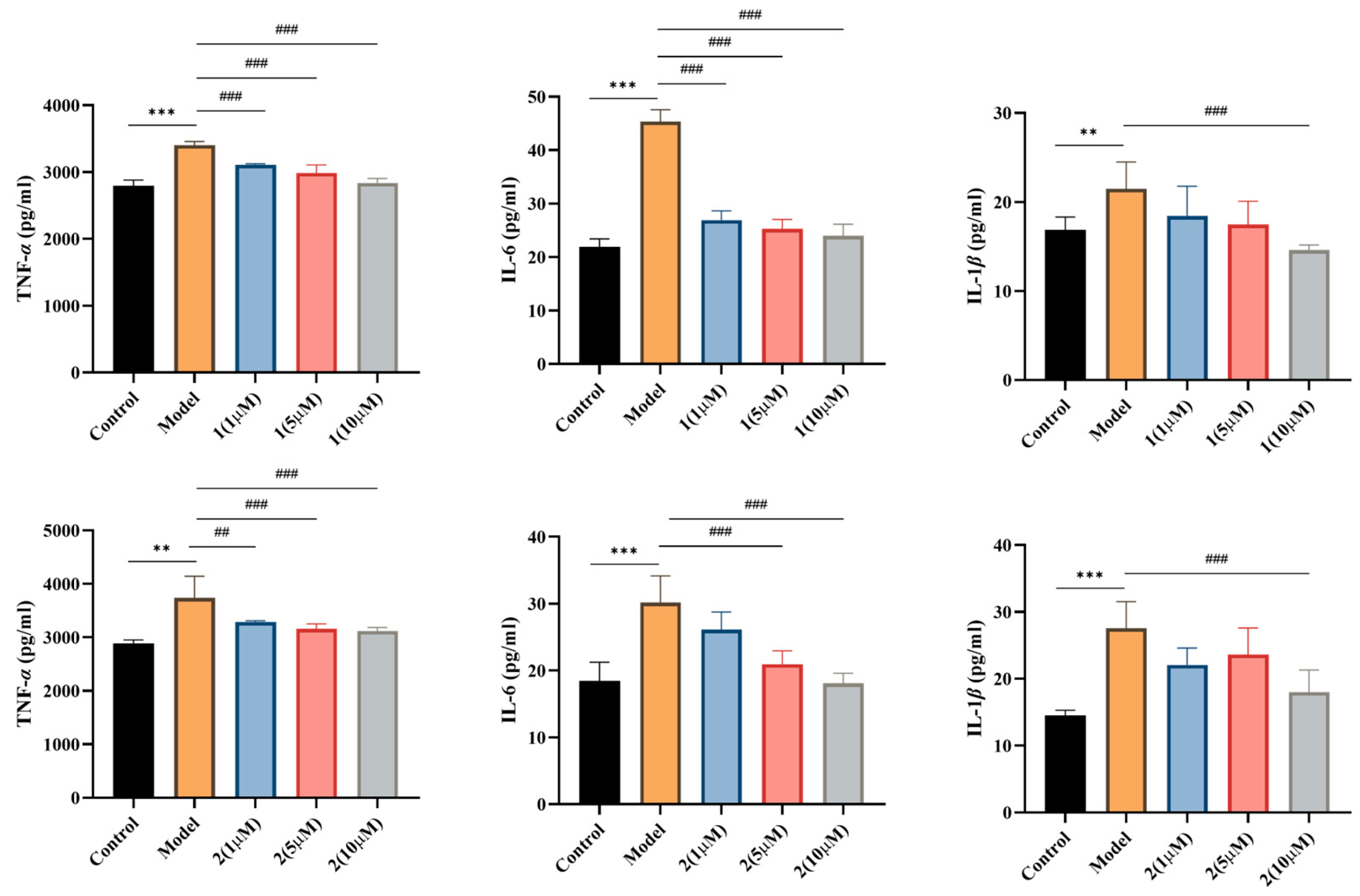

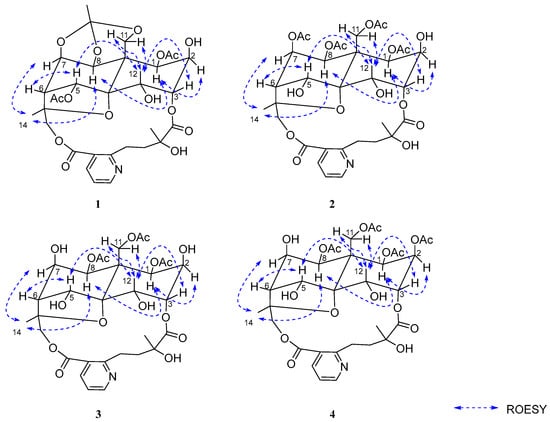

The relative configuration of 1 was determined by analysis of ROESY correlations: H-8/H-1α, H-7, and H-14; H-12/H-3, H-5, and H-11β; and H-1/H-2. These data indicated the stereochemistry of the oxygenated substituents as 1β, 2β, 3α, 4α, 5α, 7β, and 8β, which was consistent with that of 2. The structure of 2, designated wilforidatine A, was established as shown in (Figure 1).

Compound 2, obtained as a white amorphous powder, was soluble in chloroform and methanol. Its molecular formula was established as C34H43O17N by HR-ESI-MS (m/z 738.2603 [M + H]+, calcd 738.2604), indicated nine degrees of unsaturation. The 1H-NMR spectrum displayed signals for three methyl groups [δH 1.93 (3H, d, J = 1.2 Hz, H-12), 1.58 (3H, s, H-14), 1.58 (3H, s, H-10′)], two oxygenated methylene groups [δH 5.39 (1H, d, J = 13.2 Hz, H-11a), 4.61 (1H, d, J = 13.2 Hz, H-11b), 5.91 (1H, d, J = 12.6 Hz, H-15a), 3.68 (1H, d, J = 12.6 Hz, H-15b)], six oxygenated methine protons [δH 5.58 (1H, d, J = 3.0 Hz, H-1), 5.50 (1H, dd, J = 5.4, 4.2 Hz, H-7), 5.31 (1H, d, J = 6.0 Hz, H-8), 5.26 (1H, d, J = 3.0 Hz, H-5), 5.10 (1H, d, J = 3.0 Hz, H-3), 3.96 (1H, t, J = 3.0 Hz, H-2)], two methylene signals [δH 4.02 (1H, m, H-7a), 2.83 (1H, m, H-7b), 2.38 (1H, m, H-8a), 2.13 (1H, m, H-8b)], one methine [δH 2.44 (1H, d, J = 3.6 Hz, H-6)], and a set of aromatic protons indicative of a 2, 3-disubstituted pyridine ring [δH 8.68 (1H, dd, J = 4.8, 1.8 Hz, H-6′), 8.12 (1H, dd, J = 7.8, 1.8 Hz, H-4′), 7.21 (1H, dd, J = 7.8, 4.8 Hz, H-5′)]. Additionally, four acetyl methyl signals were observed [δH 2.18 (3H, s, 7-OAc), 2.17 (3H, s, 11-OAc), 1.96 (3H, s, 8-OAc), 1.95 (3H, s, 1-OAc)]. The 13C-NMR and DEPT spectra confirmed the presence of 34 carbon resonances, including four oxygenated quaternary carbons [δC 71.8 (C-4), 93.6 (C-10), 85.4 (C-13), 77.8 (C-9′)] and six carbonyl carbons [δC 170.1 (1-OAc), 170.2 (7-OAc), 169.2 (8-OAc), 169.4 (11-OAc), 173.2 (C-11′), 168.5 (C-12′)]. The 1H-1H COSY spectrum revealed two distinct spin systems: H-1/H-2/H-3 and H-5/H-6/H-7/H-8. The key HMBC correlations from H-1 to C-9 and C-11; H-3 to C-4 and C-5; H-5 to C-10 and C-13; H-6 to C-5 and C-10; H-7 to C-5, C-6, C-8, and C-9; H-8 to C-1, C-9, and C-11; H-11 to C-8, C-9, and C-10; H-12 to C-3, C-4, and C-10; H-14 to C-6, C-13, and C-15; and H-15 to C-13 and C-14 allowed the construction of a highly oxidized dihydro-β-agarofuran [9] sesquiterpene skeleton. Furthermore, the 1H-1H COSY correlations of H-4′/H-5′/H-6′ and H-7′/H-8′, along with HMBC correlations from H-7′ to C-2′ and C-8′; H-8′ to C-2′; H-4′ to C-12′; and H-10′ to C-8′, C-9′, and C-11′ supported the presence of a 3-carboxy-α-methyl picolinic acid unit. The linkage between the sesquiterpene unit and the picolinic acid moiety was established via ester bonds between C-3-O-C-11′ and C-15-O-C-12′, as evidenced by HMBC correlations from H-3 to C-11′ and from H-15 to C-12′ (Figure 2). Thus, the structure of 2 was determined as a 9′-hydroxy W-type SPA [2]. The planar structure of 2 was unequivocally established by key HMBC correlations from H-1 to the carbonyl carbon at δC 170.1 (1-OAc), H-7 to δC 170.2 (7-OAc), H-8 to δC 169.2 (8-OAc), and H-11 to δC 169.4 (11-OAc). These observations confirmed the presence of four acetoxy groups attached to C-1, C-7, C-8, and C-11, respectively.

The relative configuration of 2 was determined by analysis of the ROESY spectrum. Key ROESY correlations were observed between H-8/H-1α, H-7, and H-14; and between H-12/H-3, H-5, and H-11β. An additional correlation between H-1 and H-2 was also detected. Based on these findings, the relative stereochemistry of the oxygenated substituents was assigned as 1β, 2β, 3α, 4α, 5α, 7β, and 8β (Figure 3). In conclusion, the structure of compound 1 was determined as shown in (Figure 1). Comparison of its NMR data with those reported in the literature revealed that 2 is an analogue of the known compound alatusinine [9], differing by the absence of two acetyl groups at C-2 and C-5. Consequently, it was identified as 2,5-dideacetylalatusinine.

Figure 3.

The key ROESY correlations of 1–4.

Compound 3 was obtained as a white amorphous powder, soluble in chloroform and methanol. HR-ESI-MS displayed a pseudo-molecular ion peak at m/z 696.2477 [M+H]+, corresponding to the molecular formula C31H41O16N (calcd. 696.2498), indicating eight degrees of unsaturation. Comparison of its 1H- and 13C-NMR data with those of compound 2 indicated a close structural similarity, suggesting that 3 also belongs to the class of 9′-hydroxylated W-type SPAs [2]. However, the 1H-NMR spectrum of 3 lacked one set of acetyloxy signals compared to 2, and the H-7 proton resonance experienced a significant upfield shift from δH 5.50 to δH 4.25 (1H, m), indicating the absence of an acetyl group at C-7. Thus, 3 was deduced to be the 7-deacetyl derivative of 2. The positions of the three remaining acetyl groups were established at C-1, C-8, and C-11 based on key HMBC correlations from H-1 to the carbonyl carbon at δC 169.9 (1-OAc), H-8 to δC 169.28 (8-OAc), and H-11 to δC 169.31 (11-OAc) (Figure 2), thereby confirming the planar structure of 3.

The relative configuration was determined through analysis of the ROESY spectrum. Key correlations observed between H-8/H-1α, H-7, and H-14; H-12/H-3, H-5, and H-11β; and H-1/H-2 indicated that the stereochemistry of the oxygenated substituents was consistent with that of 2 (Figure 3), assigned as 1β, 2β, 3α, 4α, 5α, 7β, and 8β. In conclusion, the structure of compound 3 was determined as shown in (Figure 1). It is identified as the 7-deacetyl analogue of 2 and was consequently named 2,5,7-trideacetylalatusinine.

Compound 4 was obtained as a white amorphous powder. Its molecular formula was established as C34H43O17N by HR-ESI-MS (m/z 738.2584 [M + H]+, calcd 738.2604), corresponding to nine degrees of unsaturation. Comparison of its 1D NMR data (Table 1 and Table 2) with those of 3 indicated a high degree of structural similarity, confirming that 4 also belongs to the class of 9′-hydroxylated W-type SPAs. However, the 1H-NMR spectrum of 4 displayed an additional acetyl signal relative to 3, and the H-2 proton resonance experienced a downfield shift from δH 3.96 to δH 5.13 (1H, m), indicating acetylation at the C-2 position. These observations suggested that 4 is the 2-acetyl derivative of 3. The locations of the four acetyl groups were confirmed by key HMBC correlations: from H-1 to δC 169.6 (1-OAc), H-2 to δC 168.52 (2-OAc), H-8 to δC 169.1 (8-OAc), and H-11 to δC 169.3 (11-OAc) (Figure 2), thereby unambiguously establishing the planar structure of 4. The relative configuration was determined through analysis of the ROESY spectrum, which showed correlations between H-8/H-1α, H-7, and H-14; H-12/H-3, H-5, and H-11β; and H-1/H-2 (Figure 3). These data indicated that the stereochemistry of the oxygenated substituents (1β, 2β, 3α, 4α, 5α, 7β, 8β) was consistent with that of 3. In conclusion, the structure of 4 was determined as shown in (Figure 1) and was identified as the 2-acetyl analogue of 3. It was consequently named 5,7-dideacetylalatusinine.

The five known compounds 5–9 were identified as tripterygiumine T (5) [11], 5-deacetylwilforjine (6) [6], tripfordine A (7) [12], chiapenine ES-IV (8) [9], and wilfordsuine (9) [13], by comparison of their spectroscopic data with reported data.

2.2. Biological Assay

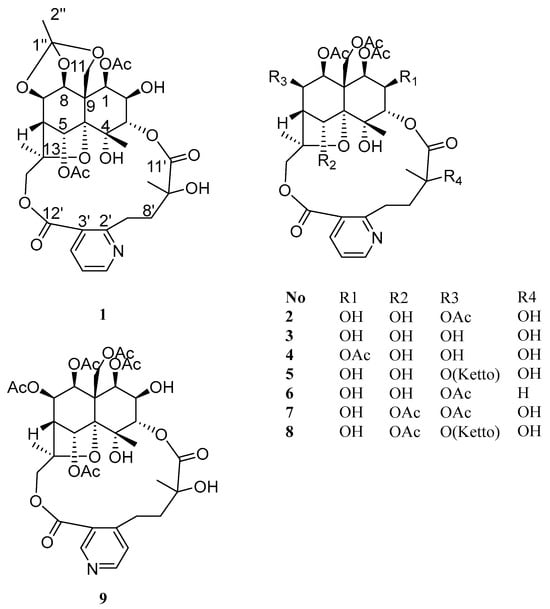

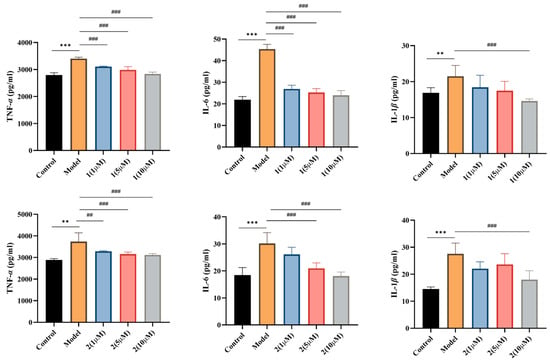

The anti-inflammatory activities of the isolated compounds (1–9) were evaluated using a lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced RAW264.7 macrophage model [2,3]. The inhibitory effects on nitric oxide (NO) production were measured, and the results were presented in (Table 3). Among the evaluated compounds, 1, 2, 4, 5 and 9 exhibited significant concentration-dependent inhibition of NO production, with IC50 values ranging from 2.43 to 14.76 μM. Notably, 9 demonstrated the most potent activity (IC50 = 2.43 ± 0.18 μM). Compounds 1 and 5 also showed strong inhibitory effects, with IC50 values of 7.14 ± 1.89 μM and 4.88 ± 0.92 μM, respectively. Additionally, the effects of the two most active compounds (1, 2) on the secretion of key pro-inflammatory cytokines were examined. As shown in (Figure 4), both compounds significantly suppressed the production of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β in a concentration-dependent manner. These findings indicated that the isolated sesquiterpene pyridine alkaloids (SPAs), compounds 1, 2, 4, 5, and 9, possess significant anti-inflammatory properties, potentially mediated through the suppression of NO and pro-inflammatory cytokine production. It should be noted that the findings of this study, derived from an in vitro model, provide preliminary evidence of anti-inflammatory potential. However, further investigation is required to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of action.

Table 3.

NO inhibitory effects of 1, 2, 4, 5 and 9 in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells.

Figure 4.

Compounds 1 and 2 significantly reduced the release levels of key inflammatory mediators TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β. (** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001) vs. control group; (## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001) vs. model group.

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Biological Assay

The instrumentation and reagents employed in this study were similar to those in our previous reports [2].

3.2. Extraction and Isolation

The dried roots of Tripterygium wilfordii (50 kg) were pulverized and exhaustively extracted three times with 10 volumes of 95% ethanol under reflux. The combined filtrates were concentrated under reduced pressure to afford a crude total extract. This extract was subsequently dispersed in water and partitioned three times with an equal volume of chloroform. The organic phases were combined and evaporated under reduced pressure, yielding a chloroform-soluble extract (200 g). A portion of this extract (200 g) was dissolved in a suitable amount of ethyl acetate and subjected to column chromatography over neutral alumina, using ethyl acetate as the eluent. After solvent removal, 68 g of an enriched fraction was obtained. This fraction (50 g) was further separated by dry loading on an ODS reverse-phase column, with a gradient elution of methanol-water (10:90 → 100:0, v/v), resulting in the collection of 16 fractions (Fr.1-16). Fraction Fr.9 (7.965 g) was first separated by preparative HPLC on a Waters XBridge Prep OBD C18 column (5 µm, 19 × 250 mm), using an isocratic eluent of ACN-H2O (23:77, v/v) at a flow rate of 16 mL/min, to yield seven subfractions (Fr.9-1 to Fr.9-7). Subfraction Fr.9-2 (260 mg) was further purified by semipreparative HPLC on a Waters XSelect HSS T3 OBD Prep C18 column (5 µm, 10 × 250 mm) with CAN-H2O (30:70, v/v; 4 mL/min), affording five fractions (Fr.9-2-1 to Fr.9-2-5). Fr.9-2-1 (139 mg) was subsequently chromatographed on a YMC-Triart Phenyl column (5 µm, 10 × 250 mm) under isocratic conditions [ACN-H2O (30:70, v/v); 4 mL/min] to yield compounds 5 (4.56 mg, tR 20 min) and 1 (2.32 mg, tR 22 min). Subfraction Fr.9-4 (450 mg) was separated on a YMC-Pack Ph column (5 µm, 10 × 250 mm) using CAN-H2O (33:67, v/v; 4 mL/min), giving two pooled fractions (Fr.9-4-1 and Fr.9-4-2). Fr.9-4-1 (290 mg) was then subjected to semipreparative HPLC on a Waters XSelect HSS T3 OBD Prep C18 column with ACN-H2O (28:72, v/v; 4 mL/min), yielding compounds 3 (0.84 mg, tR 17 min) and 4 (9.96 mg, tR 19 min). Purification of Fr.9-4-2 (54 mg) on a YMC-Triart Phenyl column [ACN-H2O (30:70, v/v); 4 mL/min] afforded compound 2 (17.55 mg, tR 20 min). Subfraction Fr.9-5 (150 mg) was fractionated on a Dikam Inspire C18 column (5 µm, 10 × 250 mm) with MeOH-H2O (50:50, v/v; 4 mL/min) to give five fractions (Fr.9-5-1 to Fr.9-5-5). Fr.9-5-1 (59 mg) was re-chromatographed on the same Dikam Inspire C18 column under isocratic conditions [ACN-H2O (30:70, v/v); 4 mL/min], yielding compounds 6 (4 mg, tR 19 min) and 7 (15 mg, tR 24 min). Subfraction Fr.9-6 (312 mg) was separated on a Waters XSelect HSS T3 OBD Prep C18 column using ACN-H2O (28:72, v/v; 4 mL/min), providing four fractions (Fr.9-6-1 to Fr.9-6-4). Final purification of Fr.9-6-4 (75 mg) on a YMC-Triart Phenyl column [ACN-H2O (30:70, v/v); 2 mL/min] yielded compound 8 (37 mg, tR 60 min). Subfraction Fr.9-7 (380 mg) was directly purified by semipreparative HPLC on a YMC-Triart Phenyl column with ACN-H2O (29:71, v/v; 4 mL/min) to afford compound 9 (8.91 mg, tR 35 min).

3.3. Characterization of New Compounds

- 2,5-dideacetylalatusinine (2): White amorphous powder, = 8.6 (c 0.06, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) = 202 (4.28), 214 (4.12), 268 (3.65) nm; IR vmax 3356, 1740, 1372, 1256, 1045, 709 cm−1; 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectral data, see Table 1 and Table 2; HRESIMS: m/z 738.2603 [M + H]+ (calcd for C34H44NO17, 738.2604).

- 2,5,7-trideacetylalatusinine (3): White amorphous powder; = 15.0 (c 0.03, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) = 202 (4.22), 219 (3.92), 268 (3.32) nm; IR vmax 1742, 1370, 1236, 1045, 1033, 953 cm−1; 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectral data, see Table 1 and Table 2; HRESIMS: m/z 696.2477 [M + H]+ (calcd for C31H42O16N, 696.2498).

- 5,7-dideacetylalatusinine (4): White amorphous powder; = −39.0 (c 0.03, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) = 203 (4.44), 215 (4.25), 268 (3.80) nm; IR vmax 3336, 1735, 1373, 1248, 1229, 1079, 954 cm−1; 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectral data, see Table 1 and Table 2; HRESIMS: m/z 738.2584 [M + H]+ (calcd for C34H44O17N, 738.2604).

3.4. Cell Culture

3.5. Anti-Inflammatory Activity Assays

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, a phytochemical investigation of the roots of Tripterygium wilfordii Hook. f. resulted in the isolation and structural characterization of nine sesquiterpene pyridine alkaloids (SPAs). Among these, four were identified as previously undescribed compounds (1–4), while five were known analogues (5–9). The structures of the new alkaloids were unequivocally established through comprehensive analysis of spectroscopic data, including 1D and 2D NMR and HRESMS. Notably, compound 1 possessed a unique cage-like ether moiety. This structural feature represents a novel archetype within the SPA family isolated from this plant source.

Evaluation of the anti-inflammatory potential of the isolated compounds demonstrated that several, particularly 1, 2, 4, 5, and 9, significantly inhibited the production of nitric oxide (NO) and key pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β) in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 macrophages. The structure–activity relationship (SAR) analysis indicated that acetylation of hydroxyl groups at specific positions of the SPA skeleton can markedly enhance anti-inflammatory potency, providing critical insights for future medicinal chemistry optimization. This study enhanced the known chemical diversity of T. wilfordii and underscored the potential of its sesquiterpenoid alkaloids as valuable scaffolds for the development of novel anti-inflammatory agents. Further investigation into the precise molecular mechanisms and in vivo efficacy of these compounds is warranted to fully assess their therapeutic potential.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/molecules31020271/s1. Figures S1–S44: 1D-, 2D-NMR, HRMS, UV, and IR spectra for the new compounds; Figures S45–S59: HRMS, 1H- and 13C-NMR spectra for the known compounds; Page 3 for Cell culture and Anti-inflammatory activity assays.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.-F.W.; methodology, Y.-T.L. and Y.-D.W.; data analysis and structural elucidation, Y.-D.W. and Y.-T.L.; manuscript preparation: Y.-T.L., Y.-D.W., Z.-M.Z., Y.-J.W., B.-R.Z., Y.-L.D., H.-Y.Y.; funding acquisition, Y.-D.W. and X.-F.W. Project administration, X.-F.W.; Design, X.-F.W.; Supervision, X.-F.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the State Key Laboratory of Drug Regulatory Science Project (2025SKLDRS0332), and Training Fund for academic leaders of NIFDC (2025X2).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the article and Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Shuai Kang for the plant identification.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, Y.; Dai, Z.; Yan, J.; Wu, X.; Ma, S. Comprehensive Evaluation of the Quality of Tripterygium Glycosides Tablets Based on Multi-Component Quantification Combined with an In Vitro Biological Assay. Molecules 2022, 27, 5102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Yan, J.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, M.; Wu, X.; Ma, S. Immunosuppressive Sesquiterpene Pyridine Alkaloids from Tripterygium wilfordii Hook. f. Molecules 2022, 27, 7274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, K.L.; Fan, Y.Y.; Gong, Q.; Liu, Q.F.; Cui, M.J.; Fu, K.C.; Zhang, H.Y.; Yue, J.M. Densely Functionalized Macrocyclic Sesquiterpene Pyridine Alkaloids from Maytenus austroyunnanensis. J. Nat. Prod. 2023, 86, 2315–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yan, J.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ma, S.; Wu, X. Quantification of sesquiterpene pyridine alkaloids from genus Tripterygium by band-selective HSQC NMR. Anal. Chim. Acta 2023, 1274, 341568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Li, C.J.; Ma, J.; Yang, J.Z.; Chen, X.G.; Hou, Q.; Zhang, D.M. Bioactive sesquiterpene polyol esters from the leaves of Tripterygium wilfordii. Fitoterapia 2014, 96, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ning, R.; Zhao, J.; Chen, L.; Mu, H.; Chen, Z.; Yang, K.; Xu, X.; Litifu, D.; Zuo, J.; He, S.; et al. Macrolide sesquiterpene pyridine alkaloids from Celastrus monospermus and evaluation of their immunosuppressive and anti-osteoclastogenesis activities. Bioorg. Chem. 2024, 145, 107246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Jia, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Sun, J.; Yu, J.; Chen, H.; Sui, L.; Leng, A.; Guo, P.; Wang, C. Macrolide sesquiterpene pyridine alkaloids from the roots of Tripterygium regelii and their anti-inflammatory activity. Bioorg. Chem. 2025, 158, 108330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Q.; Shen, J.S.; Wu, X.R.; Peng, H.Z.; Fu, Z.H.; Chen, L.Q.; Zhao, Y.L.; Ye, M.; Luo, X.D. Antithrombotic macrocyclic sesquiterpene pyridine alkaloids from Tripterygium hypoglaucum. Phytochemistry 2025, 236, 114516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, M.; Guadaño, A.; Jiménez, I.; Ravelo, A.; González-Coloma, A.; Bazzocchi, I. Insecticidal sesquiterpene pyridine alkaloids from Maytenus chiapensis. J. Nat. Prod. 2004, 67, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riyadi, S.A.; Naini, A.A.; Supratman, U. Sesquiterpenoids from Meliaceae Family and Their Biological Activities. Molecules 2023, 28, 4874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, C.; Huang, X.X.; Bai, M.; Wu, J.; Li, J.Y.; Liu, Q.B.; Li, L.Z.; Song, S.J. Anti-inflammatory sesquiterpene pyridine alkaloids from Tripterygium wilfordii. Fitoterapia 2015, 105, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horiuch, M.; Murakami, C.; Fukamiya, N.; Donglei, Y.; Tzu-Hsuan, C.; Kenneth, F.; Zhang, D.; Yoshihisa, T.; Yasuhiro, I.; Lee, Y. Tripfordines A–C, sesquiterpene pyridine alkaloids from Tripterygium wilfordii, and structure anti-HIV activity relationships of Tripterygium alkaloids. J. Nat. Prod. 2006, 69, 1271–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.; Li, Y.; Ying, J.; Guo, S.; Deng, F. Study of Sesquiterpene Alkaloids from Tripterygium wilfordii (IV). Acta Bot. Sin. 2001, 36, 116. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.