Flexible Copper-Based TEM Grid for Microscopic Characterization of Aged Magnetotactic Bacteria MS-1 and Their Magnetosome Crystals in Air-Dried Droplet

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

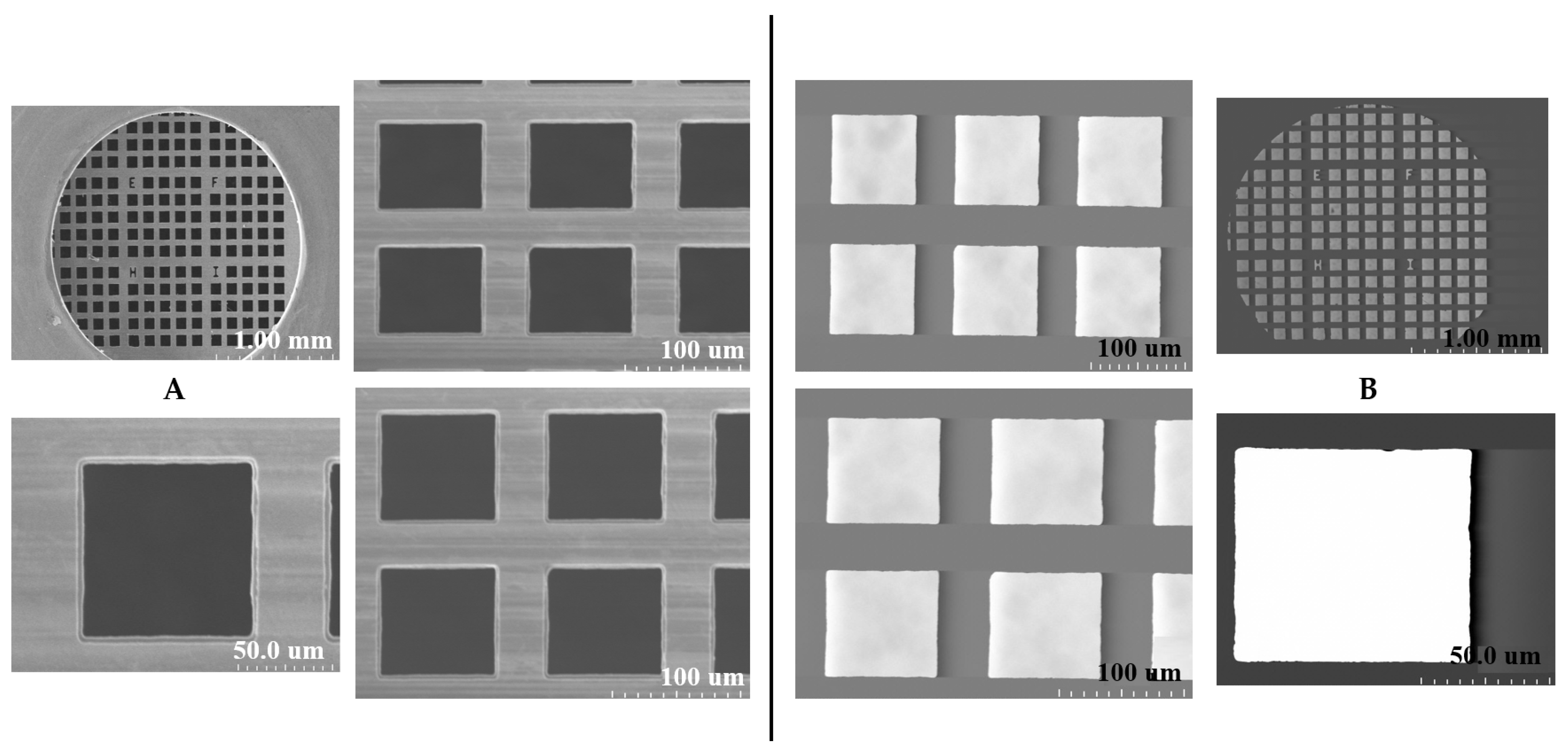

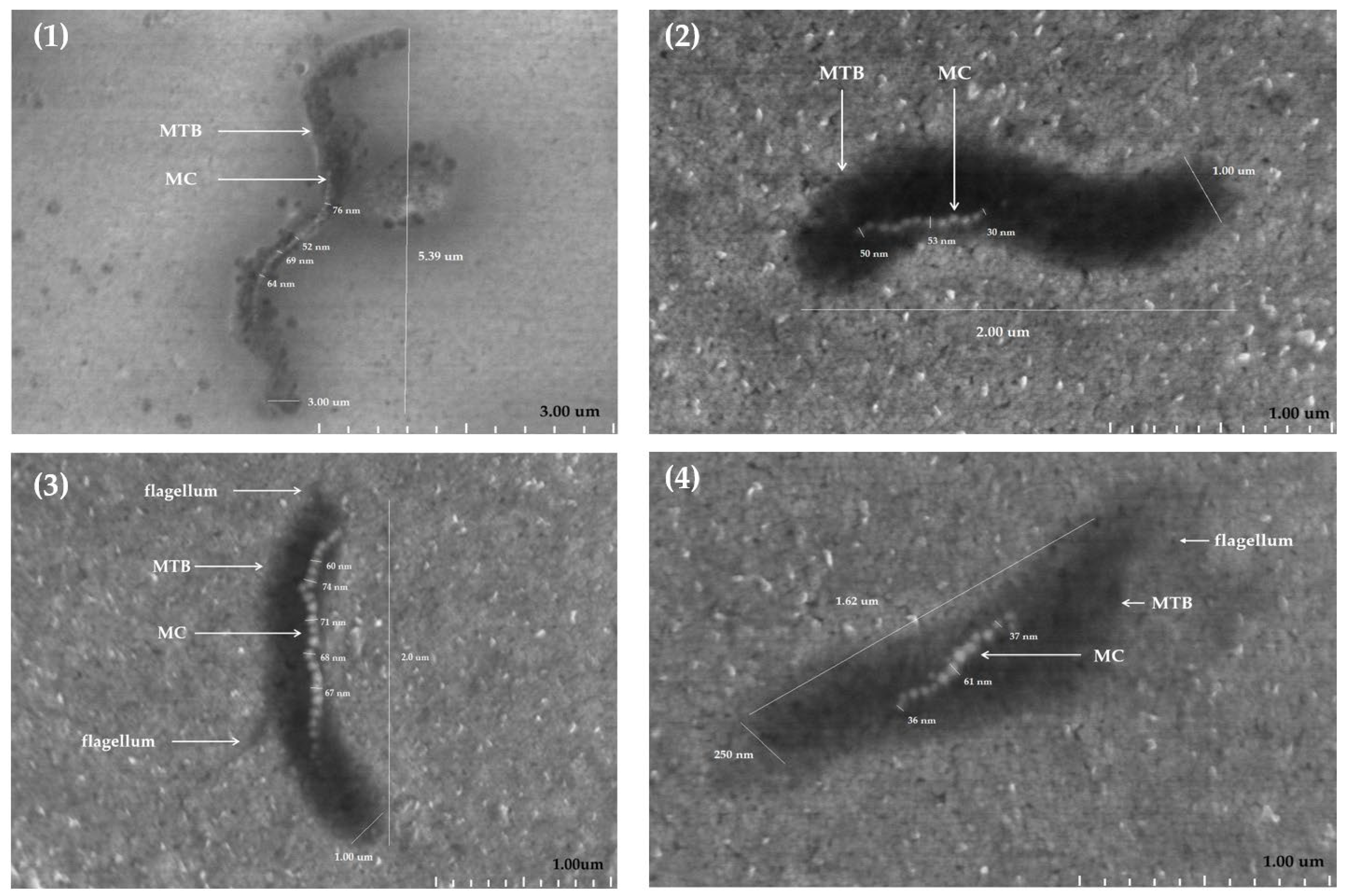

2.1. SEM and STEM Analyses of Copper TEM Grid

2.1.1. Untreated with MS-1 Bacterial Cells

2.1.2. Treated with MS-1 Bacterial Cells

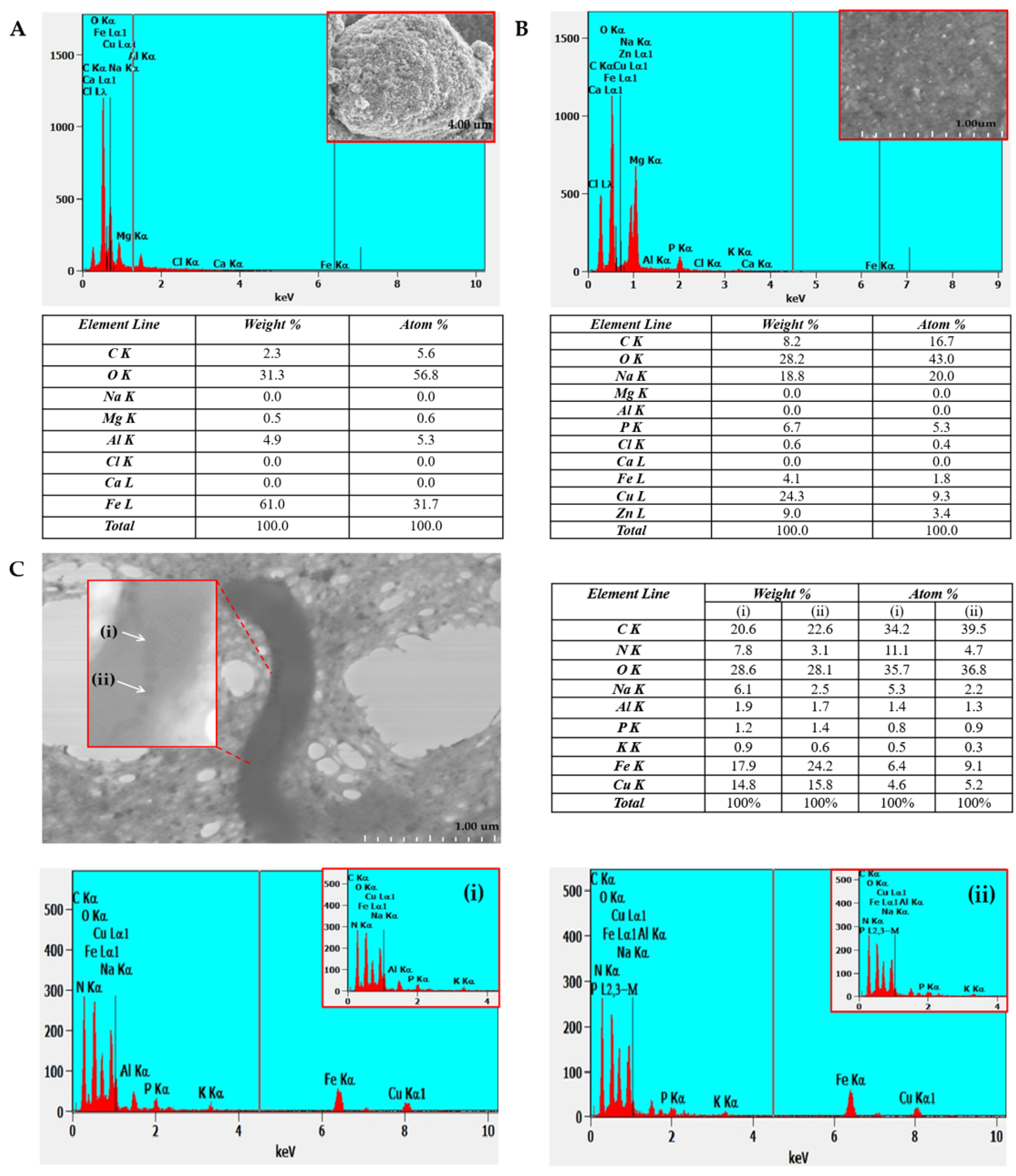

2.2. EDX Analysis of a Copper TEM Grid

2.2.1. Untreated with MS-1 Bacterial Cells

2.2.2. Treated with MS-1 Bacterial Cells

2.3. AFM Analysis of a Copper TEM Grid

2.3.1. Untreated with MS-1 Bacterial Cells

2.3.2. Treated with MS-1 Bacterial Cells

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Culture

4.2. Support and Sample Preparation

4.3. Microscopic Characterization

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bazylinski, D.A.; Frankel, R.B. Magnetosome Formation in Prokaryotes. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004, 2, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazylinski, D.A.; Lefèvre, C.T. Magnetotactic Bacteria from Extreme Environments. Life 2013, 3, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satyanarayana, S.; Padmaprahlada, S.; Chitradurga, R.; Bhattacharya, S. Orientational Dynamics of Magnetotactic Bacteria in Earth’s Magnetic Field—A Simulation Study. J. Biol. Phys. 2021, 47, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blakemore, R. Magnetotactic Bacteria. Science 1975, 190, 377–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, N.L.; Carpa, R.; Ionescu, R.E.; Popa, C.O. The Biomedical Limitations of Magnetic Nanoparticles and a Biocompatible Alternative in the Form of Magnetotactic Bacteria. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faivre, D.; Schüler, D. Magnetotactic Bacteria and Magnetosomes. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 4875–4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazylinski, D.A.; Garratt-Reed, A.J.; Frankel, R.B. Electron Microscopic Studies of Magnetosomes in Magnetotactic Bacteria. Microsc. Res. Tech. 1994, 27, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, N.L.; Popa, C.O.; Ionescu, R.E. Use of Natural Magnetosome Crystals from Magnetotactic Bacteria for Local Therapy Versus Magnetic Nanoparticles of Similar Compositions, Sizes and Shapes. In Proceedings of the Selected Papers from ICIR EUROINVENT—2025; Sandu, A.V., Vizureanu, P., Abdullah, M.M.A.B., Nabialek, M., Zainol, M.R.R.M.A., Sandu, I., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Araujo, A.C.V.; Abreu, F.; Silva, K.T.; Bazylinski, D.A.; Lins, U. Magnetotactic Bacteria as Potential Sources of Bioproducts. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 389–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, N.L.; Popa, C.O.; Ionescu, R.E. Natural Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Produced by Aquatic Magnetotactic Bacteria as Ideal Nanozymes for Nano-Guided Biosensing Platforms—A Systematic Review. Biosensors 2025, 15, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Zhou, X.; Long, R.; Xie, M.; Kankala, R.K.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.S.; Liu, Y. Biomedical Applications of Magnetosomes: State of the Art and Perspectives. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 28, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alphandéry, E. Applications of Magnetosomes Synthesized by Magnetotactic Bacteria in Medicine. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2014, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertani, L.E.; Weko, J.; Phillips, K.V.; Gray, R.F.; Kirschvink, J.L. Physical and Genetic Characterization of the Genome of Magnetospirillum Magnetotacticum, Strain MS-1. Gene 2001, 264, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, I.S.M.; Misra, S. Control Characteristics of Magnetotactic Bacteria: Magnetospirillum Magnetotacticum Strain MS-1 and Magnetospirillum Magneticum Strain AMB-1. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2014, 50, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, S.; Kale, A.A.; Banpurkar, A.G.; Kulkarni, G.R.; Ogale, S.B. On the Change in Bacterial Size and Magnetosome Features for Magnetospirillum Magnetotacticum (MS-1) under High Concentrations of Zinc and Nickel. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 4211–4218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haripriyaa, M.; Suthindhiran, K. Investigation of Pharmacokinetics and Immunogenicity of Magnetosomes. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2024, 52, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, V.K.; Pramanik, S.; Alghamdi, S.; Atwah, B.; Qusty, N.F.; Babalghith, A.O.; Solanki, V.S.; Agarwal, N.; Gupta, N.; Niazi, P.; et al. Therapeutic Innovations in Nanomedicine: Exploring the Potential of Magnetotactic Bacteria and Bacterial Magnetosomes. Int. J. Nanomed. 2025, 20, 403–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, J.; Gandía, D.; Jefremovas, E.M.; Gandarias, L.; Villanueva, D.; Lete, N.; Marcano, L.; García-Prieto, A.; Orue, I.; Barquín, L.F.; et al. Magnetotactic Bacteria: Biorobots for Targeted Therapies and Model Nanomagnetic Systems. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Magnetic Conference—Short Papers (INTERMAG Short Papers), Sendai, Japan, 15–19 May 2023; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Cowley, J.M. Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy. In Handbook of Microscopy for Nanotechnology; Yao, N., Wang, Z.L., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2005; pp. 455–491. ISBN 978-1-4020-8006-7. [Google Scholar]

- Agibayeva, A.; Guney, M.; Karaca, F.; Kumisbek, A.; Kim, J.R.; Avcu, E. Analytical Methods for Physicochemical Characterization and Toxicity Assessment of Atmospheric Particulate Matter: A Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirakovski, D.; Damevska, K.; Simeonovski, V.; Nikolovska, S.; Boev, B.; Petrov, A.; Sijakova Ivanova, T.; Zendelska, A.; Hadzi-Nikolova, M.; Boev, I.; et al. Use of SEM/EDX Methods for the Analysis of Ambient Particulate Matter Adhering to the Skin Surface. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, 1376–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Tardajos, A.P.; Wang, D.; Choukroun, D.; Van Daele, K.; Breugelmans, T.; Bals, S. A Simple Method to Clean Ligand Contamination on TEM Grids. Ultramicroscopy 2021, 221, 113195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizondo-Villarreal, N.; Verástegui-Domínguez, L.; Rodríguez-Batista, R.; Gándara-Martínez, E.; Alcorta-García, A.; Martínez-Delgado, D.; Rodríguez-Castellanos, E.A.; Vázquez-Rodríguez, F.; Gómez-Rodríguez, C. Green Synthesis of Magnetic Nanoparticles of Iron Oxide Using Aqueous Extracts of Lemon Peel Waste and Its Application in Anti-Corrosive Coatings. Materials 2022, 15, 8328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amor, M.; Ceballos, A.; Wan, J.; Simon, C.P.; Aron, A.T.; Chang, C.J.; Hellman, F.; Komeili, A. Magnetotactic Bacteria Accumulate a Large Pool of Iron Distinct from Their Magnetite Crystals. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e01278-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dujardin, A.; Wolf, P.D.; Lafont, F.; Dupres, V. Automated Multi-Sample Acquisition and Analysis Using Atomic Force Microscopy for Biomedical Applications. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gour, S.; Mukherjee, A.; Balani, K.; Dhami, N.K. Atomic Force Microscopic Investigations of Transient Early-Stage Bacterial Adhesion and Antibacterial Activity of Silver and Ceria Modified Bioactive Glass. J. Mater. Res. 2024, 39, 2415–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Wu, H.; Cai, P.; Fein, J.B.; Chen, W. Atomic Force Microscopy Measurements of Bacterial Adhesion and Biofilm Formation onto Clay-Sized Particles. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schillers, H.; Rianna, C.; Schäpe, J.; Luque, T.; Doschke, H.; Wälte, M.; Uriarte, J.J.; Campillo, N.; Michanetzis, G.P.A.; Bobrowska, J.; et al. Standardized Nanomechanical Atomic Force Microscopy Procedure (SNAP) for Measuring Soft and Biological Samples. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadtländer, C.T.K.-H. Scanning Electron Microscopy and Transmission Electron Microscopy of Mollicutes: Challenges and Opportunities. In Modern Research and Educational Topics in Microscopy; Méndez-Vilas, A., Díaz, J., Eds.; FORMATEX: Paris, France, 2007; Volume 1, pp. 122–131. ISBN 978-84-611-9419-3. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmans, L.; Moisiadis, P.; Van Meerbeek, B.; Quirynen, M.; Lambrechts, P. Microscopic Observation of Bacteria: Review Highlighting the Use of Environmental SEM. Int. Endod. J. 2005, 38, 775–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, N.L.; Popa, C.O.; Ionescu, R.E. Updates on the Advantages and Disadvantages of Microscopic and Spectroscopic Characterization of Magnetotactic Bacteria for Biosensor Applications. Biosensors 2025, 15, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datye, A.; DeLaRiva, A. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). In Springer Handbook of Advanced Catalyst Characterization; Wachs, I.E., Bañares, M.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 359–380. ISBN 978-3-031-07125-6. [Google Scholar]

- Kaláb, M.; Chabot, D. Conventional Scanning Electron Microscopy of Bacteria. Infocus Mag. 2008, 10, 42–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relucenti, M.; Familiari, G.; Donfrancesco, O.; Taurino, M.; Li, X.; Chen, R.; Artini, M.; Papa, R.; Selan, L. Microscopy Methods for Biofilm Imaging: Focus on SEM and VP-SEM Pros and Cons. Biology 2021, 10, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefèvre, C.T.; Bazylinski, D.A. Ecology, Diversity, and Evolution of Magnetotactic Bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2013, 77, 497–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefèvre, C.T.; Bennet, M.; Landau, L.; Vach, P.; Pignol, D.; Bazylinski, D.A.; Frankel, R.B.; Klumpp, S.; Faivre, D. Diversity of Magneto-Aerotactic Behaviors and Oxygen Sensing Mechanisms in Cultured Magnetotactic Bacteria. Biophys. J. 2014, 107, 527–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flies, C.B.; Jonkers, H.M.; de Beer, D.; Bosselmann, K.; Böttcher, M.E.; Schüler, D. Diversity and Vertical Distribution of Magnetotactic Bacteria along Chemical Gradients in Freshwater Microcosms. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2005, 52, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salam, M.A.; Korkmaz, N.; Cycil, L.M.; Hasan, F. Isolation, Microscopic and Magnetotactic Characterization of Magnetospirillum Moscoviense MS-24 from Banjosa Lake, Pakistan. Biotechnol. Lett. 2023, 45, 967–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcano, L.; Orue, I.; Gandia, D.; Gandarias, L.; Weigand, M.; Abrudan, R.M.; García-Prieto, A.; García-Arribas, A.; Muela, A.; Fdez-Gubieda, M.L.; et al. Magnetic Anisotropy of Individual Nanomagnets Embedded in Biological Systems Determined by Axi-Asymmetric X-Ray Transmission Microscopy. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 7398–7408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaible, G.A.; Kohtz, A.J.; Cliff, J.; Hatzenpichler, R. Correlative SIP-FISH-Raman-SEM-NanoSIMS Links Identity, Morphology, Biochemistry, and Physiology of Environmental Microbes. ISME Commun. 2022, 2, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, I.S.M.; Pichel, M.P.; Zondervan, L.; Abelmann, L.; Misra, S. Characterization and Control of Biological Microrobots. In Experimental Robotics: The 13th International Symposium on Experimental Robotics; Desai, J.P., Dudek, G., Khatib, O., Kumar, V., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 617–631. ISBN 978-3-319-00065-7. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, I.S.M.; Magdanz, V.; Sanchez, S.; Schmidt, O.G.; Misra, S. Magnetotactic Bacteria and Microjets: A Comparative Study. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Tokyo, Japan, 3–7 November 2013; pp. 2035–2040. [Google Scholar]

- Ilett, M.; S’ari, M.; Freeman, H.; Aslam, Z.; Koniuch, N.; Afzali, M.; Cattle, J.; Hooley, R.; Roncal-Herrero, T.; Collins, S.M.; et al. Analysis of Complex, Beam-Sensitive Materials by Transmission Electron Microscopy and Associated Techniques. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2020, 378, 20190601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ophus, C. Quantitative Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy for Materials Science: Imaging, Diffraction, Spectroscopy, and Tomography. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2023, 53, 105–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahidi, H.; Syed, K.; Guo, H.; Wang, X.; Wardini, J.L.; Martinez, J.; Bowman, W.J. A Review of Grain Boundary and Heterointerface Characterization in Polycrystalline Oxides by (Scanning) Transmission Electron Microscopy. Crystals 2021, 11, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, T.E.; Li, H.; Bessette, S.; Gauvin, R.; Patience, G.S.; Dummer, N.F. Experimental Methods in Chemical Engineering: Scanning Electron Microscopy and X-Ray Ultra-Microscopy—SEM and XuM. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2022, 100, 3145–3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodoroaba, V.-D. Chapter 4.4—Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (EDS). In Characterization of Nanoparticles; Hodoroaba, V.-D., Unger, W.E.S., Shard, A.G., Eds.; Micro and Nano Technologies; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 397–417. ISBN 978-0-12-814182-3. [Google Scholar]

- Haddad, G.; Takakura, T.; Bellali, S.; Fontanini, A.; Ominami, Y.; Khalil, J.B.; Raoult, D. A Preliminary Investigation into Bacterial Viability Using Scanning Electron Microscopy–Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Analysis: The Case of Antibiotics. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 967904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.I.; Oh, S.-W.; Kim, Y.-J. Power of Scanning Electron Microscopy and Energy Dispersive X-Ray Analysis in Rapid Microbial Detection and Identification at the Single Cell Level. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rimal, B.; Chang, J.D.; Liu, C.; Kim, H.; Aderotoye, O.; Zechmann, B.; Kim, S.J. Scanning Electron Microscopy and Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy of Staphylococcus Aureus Biofilms. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 37610–37620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashfaq, M.Y.; Al-Ghouti, M.A.; Al Disi, Z.A.; Zouari, N. Investigating the Microorganisms-Calcium Sulfate Interaction in Reverse Osmosis Systems Using SEM-EDX Technique. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 103963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, J.; Khanna, A.S.; Sahney, R.; Bhattacharya, A. Super Protective Anti-Bacterial Coating Development with Silica–Titania Nano Core–Shells. Nanoscale Adv. 2020, 2, 4093–4105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oestreicher, Z.; Valverde-Tercedor, C.; Chen, L.; Jimenez-Lopez, C.; Bazylinski, D.A.; Casillas-Ituarte, N.N.; Lower, S.K.; Lower, B.H. Magnetosomes and Magnetite Crystals Produced by Magnetotactic Bacteria as Resolved by Atomic Force Microscopy and Transmission Electron Microscopy. Micron 2012, 43, 1331–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marqués-Marchán, J.; Jaafar, M.; Ares, P.; Gubieda, A.G.; Berganza, E.; Abad, A.; Fdez-Gubieda, M.L.; Asenjo, A. Magnetic Imaging of Individual Magnetosome Chains in Magnetotactic Bacteria. Biomater. Adv. 2024, 163, 213969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibniz Institute DSMZ: Details. Available online: https://www.dsmz.de/collection/catalogue/details/culture/DSM-3856 (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Balkwill, D.L.; Maratea, D.; Blakemore, R.P. Ultrastructure of a Magnetotactic Spirillum. J. Bacteriol. 1980, 141, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Paul, N.L.; Deturche, R.; Beal, J.; Popa, C.O.; Ionescu, R.E. Flexible Copper-Based TEM Grid for Microscopic Characterization of Aged Magnetotactic Bacteria MS-1 and Their Magnetosome Crystals in Air-Dried Droplet. Molecules 2026, 31, 253. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020253

Paul NL, Deturche R, Beal J, Popa CO, Ionescu RE. Flexible Copper-Based TEM Grid for Microscopic Characterization of Aged Magnetotactic Bacteria MS-1 and Their Magnetosome Crystals in Air-Dried Droplet. Molecules. 2026; 31(2):253. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020253

Chicago/Turabian StylePaul, Natalia Lorela, Regis Deturche, Jeremie Beal, Catalin Ovidiu Popa, and Rodica Elena Ionescu. 2026. "Flexible Copper-Based TEM Grid for Microscopic Characterization of Aged Magnetotactic Bacteria MS-1 and Their Magnetosome Crystals in Air-Dried Droplet" Molecules 31, no. 2: 253. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020253

APA StylePaul, N. L., Deturche, R., Beal, J., Popa, C. O., & Ionescu, R. E. (2026). Flexible Copper-Based TEM Grid for Microscopic Characterization of Aged Magnetotactic Bacteria MS-1 and Their Magnetosome Crystals in Air-Dried Droplet. Molecules, 31(2), 253. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020253