Abstract

Homogeneous Kolbe-Schmitt carboxylation of phenoxides offers a mild and effective alternative to the classical high-temperature solid-phase Kolbe-Schmitt reaction. To develop this into a practical synthetic approach, we investigated several fundamental dependencies, particularly the impact of cations (Na, K, Li, Cs, and Rb), phenoxide concentration, and solvents (DMSO or DMF) on the yield and regioisomeric ratio of hydroxyaromatic carboxylic acids (HACAs). We identified optimal conditions for the effective carboxylation of different phenoxides, including a chiral Ellman’s sulfinamide derived from ortho-vanillin. Both solvents and cations were found to be crucial in the carboxylation of phenoxides. Due to solvation effects, DMSO directs CO2 attack to the para-position of phenoxide, while DMF, although less selective, generally affords higher HACA yields. The addition of equiv. amounts of mesitolate salt to phenoxide in either DMSO or DMF solution often drives the reaction to completion, resulting in yields of up to 98%. Phenoxides containing several EWG groups, such as halogens or alkyl groups, adjacent to the reaction center show considerably lower reactivity in carboxylation; however, by carefully adjusting parameters, acceptable conversions (>70%) can be achieved. Using the gasometry, we assessed the stability of phenoxide and mesitolate carbonate complexes in DMSO. These experiments revealed distinct stages for the onset of decomposition and carboxylation at atmospheric pressure, indicating a lower energy barrier in the homogeneous process. Further insight into carbonate complex behavior was obtained through DOSY and 13C NMR experiments, which support increased molecular association in solution and correlate with enhanced reactivity.

Keywords:

carboxylation; CO2; phenoxides; Kolbe–Schmitt; hydroxyaromatic carboxylic acids (HACA); DMSO; DMF 1. Introduction

The acute climate problem of atmospheric CO2 accumulation has spurred a reevaluation of all industrial processes with high greenhouse gas emissions [1]. In turn, this opened up the opportunity for chemists to consider the CO2 molecule as a universal and virtually inexhaustible source of synthetic carbon-Cl [2,3,4,5,6,7]. The global scientific and industrial community has made enormous efforts to develop processes for extracting CO2 from air and industrial waste streams to convert it into valuable chemicals, such as carboxylic acids, methanol, carbonates, carbon monoxide, methane, and higher hydrocarbons. However, the high thermodynamic stability and low energy of CO2 require substantial energy input for its transformation, with costs rising as the degree of carbon reduction increases [3]. Consequently, only a limited number of CO2 conversion processes are economically viable up to day. Among these, the synthesis of hydroxyaromatic carboxylic acids (HACAs) via direct carboxylation of solid phenoxides—the Kolbe-Schmitt reaction—remains the oldest and most established method [8,9]. Since Kolbe’s initial discovery in 1860, carboxylation of phenoxide and Schmitt’s later high-pressure modification, numerous variants of this synthesis have been developed (Scheme 1) [10,11,12]. HACAs produced by the Kolbe-Schmitt reaction are essential industrial compounds, widely used as pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, dyes, food preservatives, and technical products such as lubricants and antifreezes, as well as in polymer manufacturing [13,14].

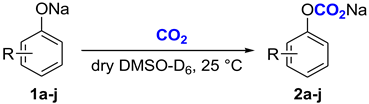

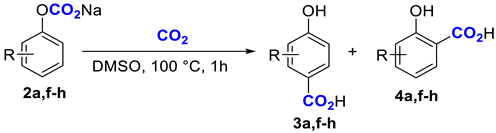

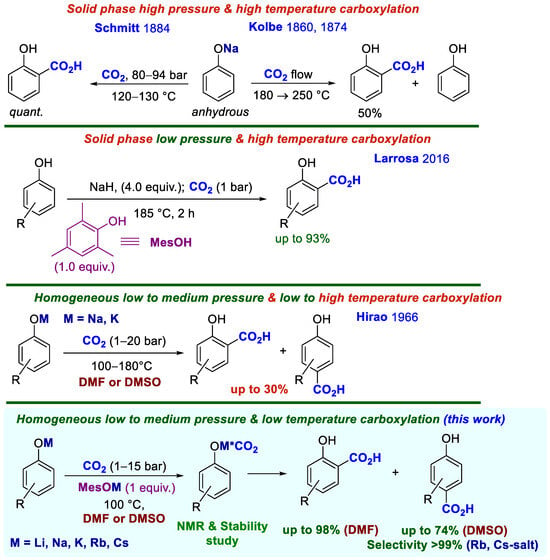

Scheme 1.

Development of the phenoxides carboxylation reaction. The * indicates uncertainty in the structure of the carbonate complex.

However, despite its successful industrial history and the wide range of applications of such important products as HACAs, the Kolbe–Schmitt reaction remains a poorly understood phenomenon. This is primarily due to the inherent challenges of studying this solid-state process. The combination of inconvenient properties—heterogeneity, moisture sensitivity, the need for high temperature and pressure, poor reproducibility, and a lack of standardized conditions—has resulted in a contradictory reaction mechanism and unclear intermediate structures. These complexities acquire new data on this reaction, both scientifically relevant and vital.

We proposed that transferring the classical heterogeneous Kolbe-Schmitt reaction into a homogeneous phase, with the potential for greater standardization, could accelerate the understanding of the mechanism and enable the development of milder, more versatile methods for the carboxylation of phenoxides. This advancement is particularly crucial for fine organic synthesis, where substrates often contain chiral centers and sensitive functional groups. Indeed, many HACAs exhibit high biological activity and are valuable building blocks in medicinal chemistry [13,14,15,16,17,18,19].

The rationale for this possibility was provided by the previous works on the use of solvents as active media, solvating phenoxides and changing their reactivity in carboxylation reaction [20,21]. The work of Kosugi et al., [22,23] who demonstrated the fundamental feasibility of low-temperature carboxylation, alongside data on enzymatic carboxylation occurring under nearly physiological conditions [24]. Of particular interest was the report by Larrosa et al. [25], which highlighted the promoting effect of in situ-generated sodium mesitolate (sodium 2,4,6-trimethylphenoxide, MesONa) in the atmospheric-pressure carboxylation of phenoxides—a modern adaptation of the classical high-temperature Kolbe synthesis (Scheme 1).

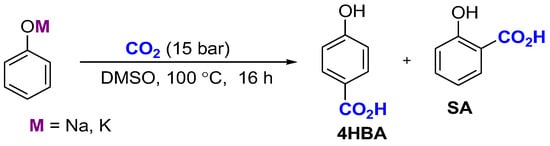

While Hirao had previously shown that phenoxide carboxylation could be performed in homogeneous solution [21], the low efficiency of this approach prevented the development of a general method for homogeneous carboxylation (Scheme 1). In our recent work [26], which implemented the homogeneous carboxylation concept, we established quantitative parameters for water’s influence on the Kolbe-Schmitt reaction. We revealed nonlinear dependencies of both reaction yield and regioselectivity on phenoxide concentration and clearly demonstrated the promoting effect of basic salts, with sodium mesitolate proving most effective. For instance, the chemical yield of the 4-hydroxybenzoic acid (4HBA) and salicylic acid (SA) mixture from PhONa carboxylation increased up to twofold with 3 equiv. of sodium isopropylcarbonate and by 1.6-fold with 1 equiv. of MesONa. The advantage of working in solutions also allowed us to obtain spectral data on the intermediate carbonate complex of the phenoxide [sodium(benzo-15-crown-5)]. In the 13C NMR spectrum, the carboxylate carbon resonance appeared unusually upfield at 142 ppm, relative to typical carbonates, providing direct evidence for the postulated “elusive” carbonate complex.

The present study continues this investigation, offering new insights into fundamental data on the reactivity of lithium, rubidium, and cesium phenoxides in DMSO and DMF and the influence of a number of factors on this process; into the relationship between the stability of intermediate carbonate complexes, their reactivity, and the donor-acceptor ability of substituents in the aromatic ring. During this work the interplay between phenoxide concentration, carboxylation yield, regioisomeric composition, and molecular association of carbonate complexes in solution was investigated. Finally this study culminates in the development of a mild and general method for synthesizing hydroxyaromatic carboxylic acids (HACAs) via a homogeneous Kolbe-Schmitt reaction. (Scheme 1).

This material is divided into the following sections:

- Study of the influence of Li, Cs and Rb cations on the yield and regioselectivity of carboxylation of phenoxides in DMSO;

- Effect of DMF solvent on the yield and regioselectivity of carboxylation of phenoxides;

- Gasometric determination of the stability of carbonate complex of potassium phenoxide in DMSO solution;

- NMR study of the influence of concentration of carbonate complex of phenoxide on its molecular association in solution and registration of spectral characteristics of various carbonate complexes in DMSO solution;

- Synthetic application of the homogeneous carboxylation method in the synthesis of HACAs.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Study of the Influence of Li, Cs, and Rb Cations on the Yield and Regioselectivity of Carboxylation of Phenoxides in DMSO

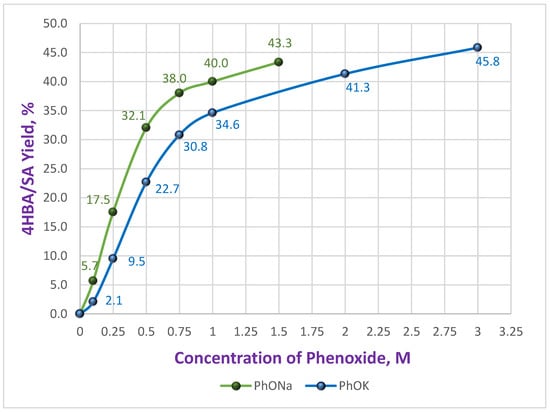

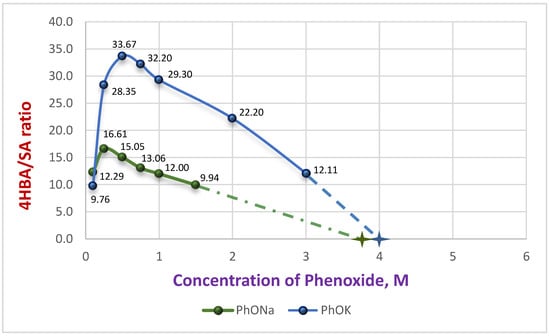

As demonstrated in our earlier work [26], the choice of the metal cation (Na+ or K+) in the phenoxide salt has a significant impact on both the chemical yield and regioselectivity of carboxylation in DMSO for the production of hydroxybenzoic acids. These dependencies were represented graphically, revealing distinct nonlinear, concentration-dependent patterns. The regioselectivity curves further exhibited extrema in the range corresponding to the maximum carboxylation rate. (see Scheme 2, Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Scheme 2.

Carboxylation of phenoxides in DMSO.

Figure 1.

Dependence of the 4HBA&SA yield on the initial concentration of Na and K phenoxides [26].

Figure 2.

Dependence of 4HBA/SA ratio on initial concentration of PhOM with extrapolation to the X-axis [26].

Building on our hypothesis that these trends could be explained by the formation of molecular associates derived from phenylcarbonate, we investigated the behavior of phenoxides containing other alkali metal cations: Cs, Rb, and Li. Phenoxides of Cs and Rb were synthesized by reacting the corresponding commercial hydroxides with phenol, followed by drying (see Supplementary Materials). Li-phenoxide was prepared according to a previously reported method [26] and introduced into solution as its carbonate complex, as pure Li-phenoxide exhibits extremely poor solubility in DMSO (~0.34 mM at 25 °C, determined by HPLC). Employing our previously described method for evaluating phenoxides’ reactivity in small vials under uniform conditions in a 700 mL steel high-pressure reactor ([26], see also Supplementary Materials, Photo S1), we conducted a series of reactions. The resulting mixtures were analyzed quantitatively via reversed-phase HPLC.

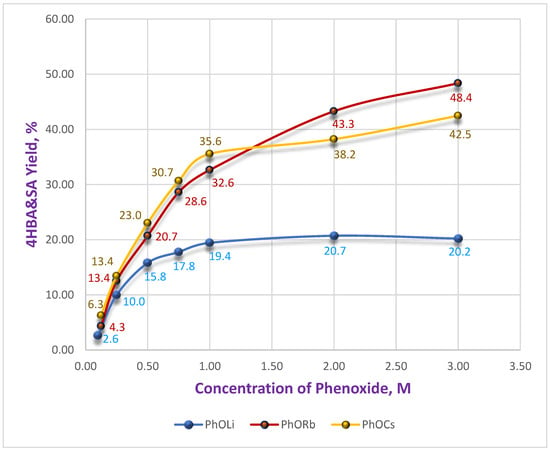

As shown, Li-phenoxide has the lowest reactivity across the entire concentration range (0.125–3.0 M) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Dependence of the 4HBA&SA yield on the initial concentration of Li, Cs and Rb phenoxides.

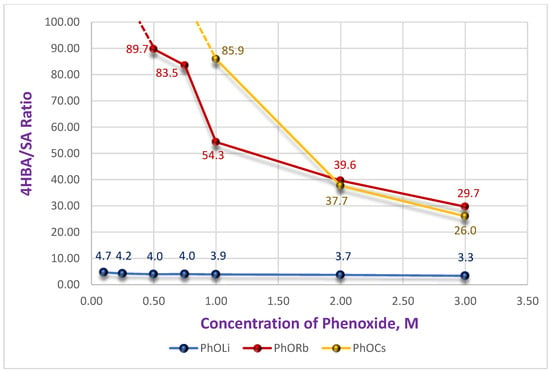

The yield curve (blue) reaches a plateau at 1.0 M PhOLi and remains constant (~20%) for concentrations up to 3.0 M. A similar constancy is observed for PhOLi in the graph showing the dependence of the ratio of isomeric acids 4HBA/SA (Figure 4). At low PhOLi concentrations (up to 0.75 M), the 4HBA/SA ratio is only 4.7–4.0. With an increase in concentration to 3.0 M it changes only marginally to 3.3. This behavior is consistent with a constancy of coordination sphere for the Li-ion, which remains essentially unchanged with concentration—a consequence of its strong Lewis acidity. A similar effect of rapid saturation of the coordination sphere in DMSO, as reflected in the activity coefficients, has been reported for lithium nitrate compared with sodium and potassium salts [27].

Figure 4.

Dependence of 4HBA/SA ratio on initial concentration of PhOM with extrapolation to undetectable level of SA.

The behavior of Cs and Rb phenoxides differs sharply from PhOLi. It is nearly identical to that of PhOK (see Figure 1 and Figure 3), with the difference that PhORb is slightly more reactive, and PhOCs is somewhat less reactive, than PhOK. Maximum yields of 42.5% and 48.4% were obtained for Cs and Rb solutions, respectively, at 3.0 M.

However, significant differences from both potassium and sodium salts emerge when examining the 4HBA/SA ratio (Figure 4; compare with Figure 1).

At low concentrations (≤0.25 M), SA was undetectable in the reaction mixtures for Cs and Rb phenoxides, even after HPLC analysis of concentrated samples.

At a concentration of 0.5 M solution, the 4HBA/SA ratio for Rb was 90:1. In contrast for Cs, SA remained undetected until reaching 1.0 M, where 4HBA/SA = 86:1, while for Rb it was 54:1. At higher concentrations, the isomer ratios converged for both salts, reaching 38–40:1 at 2.0 M and 26–30:1 at 3.0 M. Even at these concentrations, the regioselectivity remained several times higher than that achieved with the potassium salt. This effect could be of practical value for achieving high regioselectivity in the carboxylation of substituted phenoxides. The observed trend suggests that the coordination ability of the cation in DMSO solution (Li < Na < K < Rb < Cs) [28] plays a key role in the observed dependencies. Considering our earlier assumption that two molecules of the carbonate complex (and/or phenoxide) participate in the transition state [26], we can draw the following Scheme 3.

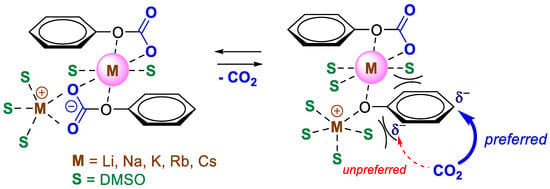

Scheme 3.

Suggested intermediates in the homogeneous carboxylation of phenoxide.

It can be suggested that an ionic associate with solvated cations and anions of the carbonate complex exists in solution. When heated, one (or both) of the carbonate complex molecules loses CO2, forming an active phenoxide, which undergoes carboxylation. Depending on the solvation shell of the cation, steric hindrances of varying levels arise in the ortho-position of the phenol ring. In the case of DMSO, the growth of the solvation shell and, accordingly, steric hindrances in the ortho-position increase with the size of the cation, which directs the carboxylation to the para-position.

2.2. Effect of DMF Solvent on the Yield and Regioselectivity of Carboxylation of Phenoxides

Comparing the regioselectivity curves of Na-Cs phenoxides, one can note that with increasing concentration, the proportion of ortho-carboxylation leading to SA increases. Because of such behavior, an analogy arises with classical solid phase Kolbe-Schmitt reaction, when by concentrating the reaction mixture, in the limit, we can arrive at the selective formation of only SA. Extrapolating the regioselectivity curves of sodium and potassium phenoxides to the X-axis, it can be assumed that already in the range of 4–5 M solutions, regioselective formation of SA is expected (see Figure 2). However, such concentration values are difficult to obtain experimentally, due to the insufficient solubility of phenoxides in DMSO. Therefore, we also studied the carboxylation of PhONa in dried DMF (water content <15 ppm), where phenoxides are more soluble. Mixtures of PhONa and DMF were obtained in various concentrations from 1 to 5 M and even more. For ease of calculation, molar ratios of PhONa/DMF rather than concentrations were used: 1:11.4 (1 M), 1:4, 1:3, 1:2.5 (5 M), 1:2, 1:1.5, 1:1, 3:1, and 5:1.

The test reactions were carried out under standard conditions at 100 °C and an initial CO2 pressure of 15 bar for 3 h. The composition of the reaction mixtures was quantitatively analyzed by HPLC (Table 1).

Table 1.

Carboxylation of PhONa in DMF.

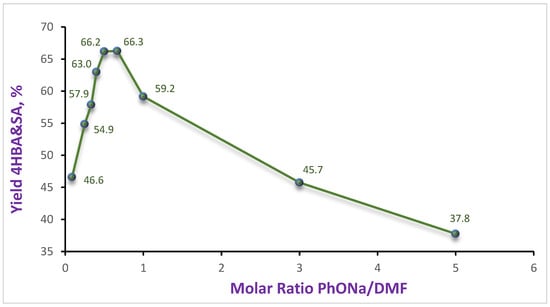

The initial experiment with a 1 M solution showed a relatively high SA content in the mixture (see Table 1, n. 1, 2). Additionally, the reaction proceeded faster, and the yield of the acid mixture was higher than in DMSO ([26] in 1 M—40%; 1.5 M—43% for 16 h). A gradual increase in the concentration of PhONa led to an increase in the SA content and, consequently, to a rise in the total yield to 66% (Table 1, n. 1–6). It should be noted that up to a DMF/PhONa ratio of 2.0–1.5:1, the absolute content of 4HBA (32–34%) remained virtually unchanged. Further reduction in the DMF quantity led to a gradual decrease in the total yield to 37.8% due to a sharp reduction in the 4HBA amounts (Table 1, n. 7–9). The graphical representation of the obtained results on the total yield is shown in Figure 5, which exhibits a characteristic maximum in the range of ratios 1:1.5–2.0.

Figure 5.

Dependence of the 4HBA&SA yield on the molar ratio of PhONa in DMF.

Since a 3 h period was initially used as the test time to evaluate the reaction yield, this time was extended to 16 h at an optimal PhONa/DMF ratio (1.0:2.0). To our delight, the total yield of 4HBA&SA reached almost 84%. The regioselectivity of PhONa carboxylation in DMF differs significantly from that in DMSO, with a higher proportion of SA formed even in a dilute 1 M solution. As the concentration increases, the 4HBA/SA ratio first equalizes (see n 1–5), and then SA begins to predominate in the mixture. However, a further reduction in the amount of solvent and the transition of the reaction to a heterogeneous solid phase process result in the termination of carboxylation. Actually, the reaction proceeds locally at the place where the solvent is introduced. At the same time, the unsolvated part of the solid sodium phenoxide (phenylcarbonate) remains unchanged, without entering into the carboxylation reaction of the aromatic system. The differences in the regioselectivity of carboxylation in DMF and DMSO are in good agreement with the decrease in standard partial molar volumes (V0) of alkali cations [29], particularly for Na+ (−2 cm3 mol−1/DMF vs. 3 cm3 mol−1/DMSO), K+ (6 cm3 mol−1/DMF vs. 11 cm3 mol−1/DMSO) and Cs+ (17 cm3 mol−1/DMF vs. 23 cm3 mol−1/DMSO). These differences in V0 would be responsible for more tight steric environment in molecular associates confirming our hypothesis about the influence of cation solvation on regioselectivity. Moreover, DMSO provides stronger solvation of charged molecules as known from its electron donor DN (Donor Number) DMSO = 29.8 and DMF = 26.6 as well as electron acceptor abilities AN (Acceptor Number) DMSO = 19.3 and DMF = 16.0 [30]. These solvation properties would limit accessing of CO2 towards oxygen and ortho-site in phenoxide.

Thus, although our attempt to connect homogeneous and solid-phase processes was largely ineffective, DMF is a successful solvent that increases phenoxide conversion and promotes more efficient ortho-carboxylation.

2.3. Gasometric Determination of the Stability of Carbonate Complexes of Phenoxides in DMSO Solution

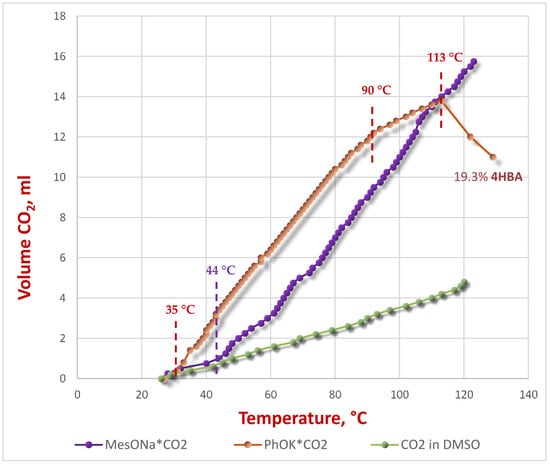

One of the aims of our work was to determine the stability of the PhOK*CO2 complex in a DMSO solution. It was proposed that the carboxylation of the phenoxide occurs in the anionic form, and the conditions of the intermediate carbonate’s decomposition are among the influencing factors [22,26]. For this purpose, we used the gasometry method, in which we recorded the volume of CO2 evolved from a 1 M solution of the PhOK*CO2 along with a gradual increase in temperature. To eliminate the influence of dissolved CO2 and its thermal expansion, comparative measurements of CO2 evolution from a saturated DMSO solution were conducted under identical conditions, including thermostatting of the gas meter’s measuring tube. Additionally, we measured the decomposition of the MesONa*CO2 complex, yielding the following graphical dependences (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Results of gasometry measurements in DMSO.

The analysis of the decomposition curve for PhOK*CO2 reveals three clearly separated stages of decomposition. The first stage begins at 35 °C, marking the onset of decomposition of the carbonate complex. At 90 °C, a bend appears on the curve, indicating a slower release of CO2, similar to the rate of CO2 release dissolved in DMSO. This stage continues until the temperature reaches 113 °C, at which point a second bend appears, accompanied by rapid CO2 absorption from the gasometer. HPLC analysis of the endpoint gasometric measurement shows the formation of 19.3% 4HBA after 38 min at atmospheric CO2 pressure. Gasometry demonstrates that the carbonate complex in solution begins to decompose at a much lower temperature than in a classical heterogeneous system. Notably, Dinjus et al. demonstrated [31] that decomposition of the solid carbonate complex occurs at 75–80 °C. It was shown that this process is not accompanied by the formation of SA, but represents the decarboxylation of the complex. Hirao and Kito also revealed [32] that thermal decomposition of the PhOK*CO2 occurs above 70 °C.

The stage of slowing CO2 release at 90 °C apparently corresponds to both the completion of the carbonate complex decomposition and the onset of carboxylation of phenoxide at atmospheric pressure. The third bend in the curve after 113 °C is apparently due to the carboxylation reaction, which is confirmed by the formation of noticeable amounts of 4HBA during this short period.

The decomposition of the solution of the carbonate complex MesONa also exhibits a characteristic form. In this case, the complex decomposes only at 44 °C, indicating its greater stability. This is explained by the greater donor properties of the aryl fragment, which stabilize the carbonate form. Interestingly, the ortho-methyl groups of mesitolate do not significantly affect the complex’s stability. A further increase in temperature shows only a gradual decomposition of the complex without a carboxylation reaction, which, in principle, is not realizable in mesitolate.

2.4. NMR Study of the Influence of Concentration of Carbonate Complex of Phenoxide on Its Molecular Association in Solution and Registration of Spectral Characteristics of Various Carbonate Complexes in DMSO Solution

2.4.1. Molecular Weight Determination of Carbonate Complex of PhONa by DOSY

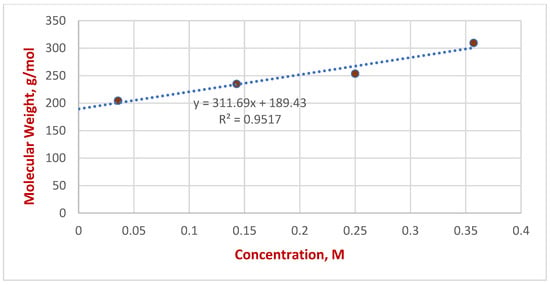

The study of concentration dependences of the carboxylation of phenoxides (yield of hydroxybenzoic acids and their regioisomeric composition) is consistent with the participation of non-monomeric phenoxide molecules in the carboxylation reaction. To investigate the proposed formation of molecular associates in solutions of phenoxides (or their carbonate complexes) in DMSO, we used diffusion-ordered NMR spectroscopy (DOSY), which enables accurate molecular mass determination. For this purpose, solutions of PhONa*CO2 were prepared in dry DMSO-D6 (dried over 4Å molecular sieves) with concentrations of 0.036 M, 0.143 M, 0.250 M, and 0.357 M. Uncharged standard compounds with different molecular weights (Ph3PO (278 g/mol), 1,1′-bis(diphenylphosphino)ferrocene (dppf, 554 g/mol) and standard polystyrene (PS, 1320 g/mol)) that do not form associates were added to each solution, and residual DMSO-D5 (83 g/mol) was used as low-molecular weight standard. From the DOSY spectra, the diffusion coefficients of the standards and the carbonate complex PhONa were determined, and the dependence of the decimal logarithm of the diffusion coefficients on the decimal logarithm of the molar masses of the standards was constructed. According to the Stokes-Einstein equation, the diffusion coefficient of a substance in a solution is directly proportional to the temperature and inversely proportional to the viscosity of the medium and the hydrodynamic radius, which is proportional to the molar mass of the substance.

Equation (1): Equation for bonding diffusion coefficient and molecular weight

The corresponding dependences of diffusion coefficients on molecular weight were obtained. For the obtained dependencies, linear approximations were constructed at each concentration (see Supplementary Materials), with determination coefficients (R2) of 0.991, 0.977, 0.993, and 0.995, respectively, indicating a good fit of the data by a linear function. From the obtained diffusion coefficients, the apparent molecular mass of the PhONa carbonate complex in a DMSO-D6 solution was determined using approximated straight lines. For solutions of the carbonate complex PhONa with concentrations of 0.036M, 0.143M, 0.250M, and 0.357M, the molecular masses obtained were 204.5, 234.9, 253.6, and 309.6 g/mol, respectively. Next, the dependence of the molecular mass determined by the DOSY NMR method on the concentration of the carbonate complex PhONa was constructed (Figure 7). The theoretical value of molecular weight of the monomeric form of the carbonate complex (PhONa*CO2) is 160.1 g/mol, though in a solution sodium ion will be solvated with several molecules of DMSO-D6 and observed molecular weight will be higher. The exact molecular weight of solvated cations is difficult to estimate because solvent molecules are in dynamic exchange. For the obtained dependence of the observed molar mass of sodium phenyl carbonate on its concentration, a linear approximation was constructed, the angular coefficient of which was 311.7, and the free coefficient was equal to 189.4. The equation of the approximating line is: MWt = 311.7*C + 189.4, R2 = 0.95. From the obtained line, one can conclude that the observed molecular mass increases with the increasing concentration of PhONa*CO2 in the solution.

Figure 7.

Dependence of the molecular mass determined by the DOSY NMR method on the concentration of the carbonate complex PhONa.

The value of the free term of the obtained approximating line is 189.4. This dependence may indicate a dynamic equilibrium and the formation of molecular associates consisting of phenyl carbonate anions, sodium cations and DMSO (DMSO-D6). The slope of the approximating line is 311.7, from which it follows that, for each unit increase in concentration, the average molecular weight increases by 311.7 g/mol. For example, at 1.0 M concentration, the molecular weight of the phenyl carbonate complex will be about 501 g/mol, and at 3.0 M it can be about 1124 g/mol, maintaining linearity with increasing concentration. Particularly, the molecular weight of the dimeric carbonate complex without the second solvated cation is 465 g/mol (see Scheme 2).

2.4.2. NMR Characteristics of Various Carbonate Complexes in DMSO Solution

Another important problem that can be studied using the NMR method is the spectral characteristics of carbonate complexes on 13C nuclei. We believe that this information can be used in the future for quantum chemical modeling of the reactivity of carbonate complexes. In the preceding paper, we obtained the 13C NMR spectrum of a phenyl carbonate complex in which a crown ether moiety bound the sodium cation. The chemical shift in the carboxylate carbon was 142 ppm, significantly shifted to the upper field relative to the chemical shifts in typical stable carbonates (Table 2). Therefore, we concluded that the carbonate complex has an intermediate structure between a carbonate and dissolved CO2 [26]. In the present work, a series of new carbonate complexes 2a–j were obtained from the corresponding phenoxides 1a–j (Table 2) by saturating the phenoxide solutions with CO2 (10 bar) in a steel autoclave and subsequent NMR analysis at ambient pressure. For comparison, literature data are given for the chemical shifts in the carboxylate carbon atoms of solid potassium phenylcarbonate (Table 2, n 1), a saturated solution of CO2 in DMF (Table 2, n 2), and a phenylcarbonate complex with crown ether (Table 2, n 3).

Table 2.

Chemical shifts 13C NMR of CO2 and synthesized carbonate complexes.

The new method does not require the use of a crown ether, and for most compounds, data can be obtained specifically for carbonate complexes (Table 2, n 4–10; 2a–g). The chemical shifts in alkyl-substituted phenyl carbonates 2b–2d, 2f are in the region of 148–149 ppm, and those of unsubstituted phenyl carbonate 2a and 2,4-ditBuPh-carbonate 2e are 142–143 ppm (Table 2). Apparently, the chemical shift in the carboxylate carbon is related to the stability of the carbonate complex. In compounds with a donor aromatic system, the chemical shift is shifted towards stable carbonates, and weakening of donor activity or steric factors (as in 2e) leads to the opposite values. Methoxy-substituted carbonate 2g shows a chemical shift at 137 ppm. Further deactivation of the aromatic system leads to the failure to fix a stable carbonate complex. The carbon atom signals become very close to dissolved CO2 both in position (Table 2, n 11–12, 2h,i) and in shape (much narrower signals). However, we believe this is not purely dissolved CO2 but rather a form of its interaction with phenoxide. This is confirmed by the influence of CO2 pressure on chemical shift positions. At 4 bar (NMR ampoules for spectra under pressure), the signals of the carboxylate atom and the ortho-carbon atoms begin to shift, indicating interaction with CO2. The presence of a 4-chloro substituent in 2k does not cause significant destabilization of the carbonate complex, shifting the carbon signal to 140 ppm (Table 2, n 14). At the same time, the 3-alkyl group enhances carbonate stability, as the 2o chemical shift is highest for the 3-methyl derivative (Table 2, n 15).

Though the correlation of electronic properties of substituents with the stability of carbonate complexes (Figure 6) and chemical shifts in carboxylate carbon (Table 2) is quite clear, the correlation of reactivity with 13C chemical shifts is not evident. A more stable intermediate carbonate can be less reactive and vice versa. To determine the degree of mutual influence of the stability of the carbonate complex and its reactivity, four comparative carboxylation experiments were carried out with sodium phenoxide and three ortho-substituted phenoxides—2-chloro, 2-methoxy, and 2-allyl (100 °C, 1 h, 15 bar in DMSO). The choice of substrates was made in such a way as to, on the one hand, exclude the influence of the steric factor on the reaction center, and on the other hand, to ensure that the values of the chemical shifts in the carboxylate carbons lay on a line with decreasing values. In addition, the reaction time was reduced to 1 h to obtain non-completed reactions. As a result, the following values of chemical yield of hydroxybenzoic acids were obtained (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparable carboxylation of substituted phenoxides.

The most stable allyl-substituted derivative 2f provides a higher yield of acids 3f&4f (50.8%), whereas the less stable non-substituted phenyl-derivative 2a gave already 40% yield of 3a&4a (Table 4). This trend is followed by the two remaining carbonates, 2g and 2h, yielding 37.2% and 10.2% of the corresponding acids. Thus, 13C chemical shifts can be convenient markers for assessing the reactivity of phenoxides.

Table 4.

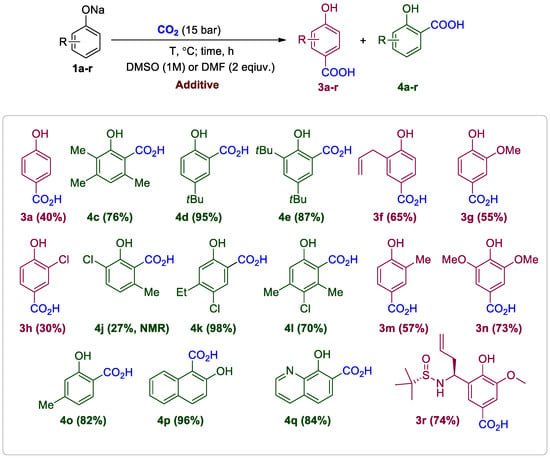

Substrate scope for carboxylation.

2.5. Synthetic Application of the Homogeneous Carboxylation Method in the Synthesis of HACAs

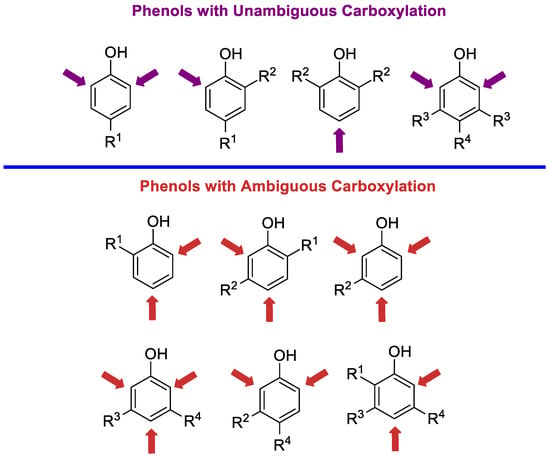

Having in hand data on the reactivity of phenoxides under various conditions and understanding how to optimize yield and control selectivity during carboxylation, we prepared different phenols for homogeneous carboxylation. All compounds can be divided into two types: those with unambiguous and those with ambiguous regioselectivity (Scheme 4). Depending on the phenol group, the conditions for carboxylation should be selected. Of course, in the group of phenols with ambiguous selectivity, it is necessary to take into account the steric influence of substituents, which play an essential role in the regioselectivity of carboxylation.

Scheme 4.

Direction of carboxylation reactions in substituted phenols.

To conduct synthetic experiments, phenoxides were prepared using various methods: (a) metal hydroxides (K, Na, Cs, Rb); (b) solutions of methylates in methanol (Li, Na, K); (c) sodium hydride in THF or DCM.

In DMF, sodium phenoxide 1a showed no selectivity (Table 4; also see Table 2). The best selectivity was observed with Cs- or Rb-phenoxides, where Cs-phenoxide efficiently yielded 4HBA 3a (40%) when the reaction was carried out in DMSO. The acid was isolated from the reaction mixture through filtration. It was noted that obtaining the acid from sodium mesitolate 1b through carboxylation was impossible. In the trimethyl-substituted phenol 1c, two carboxylation pathways—ortho and para—were possible. However, the presence of two methyl groups at the para position of 1c completely blocked the reaction along this pathway, resulting in the formation of only acid 4c (Scheme 5, Table 4). The reaction rate was low due to the adjacent methyl group, requiring a combination of conditions for a good yield: the addition of MesONa 1b in DMF and heating at 120 °C. Under these conditions, the yield of 4c reaches 76%. When introducing only one tBu substituent into the para position of the phenyl ring in 1d, unambiguous carboxylation to the ortho position was expected. Carboxylation was first tested in DMSO, and to our surprise, the product—4d (5%)—was virtually absent (Table 4). It was found that carbonate associates in DMSO virtually blocked the ortho positions of phenol (see also Scheme 3), confirming the conclusion that the carboxylation pathways to the ortho and para positions are completely kinetically independent [26]. Replacing the solvent with DMF and using additive 1b allows one to obtain acid 4d in fairly quantitative yield (95%). Disubstituted phenol 1e was also successfully carboxylated under these conditions, yielding 4e (87%) (Scheme 5, Table 4). For mono-substituted ambiguous phenols 1f and 1g, the selectivity issue is resolved by using DMSO, while DMF did not provide such a possibility for these substrates. The corresponding para-substituted acids 3f (65%) and 3g (55%) were isolated by chromatography (Scheme 5, Table 4). The introduction of the acceptor chlorine substituent in 1h significantly slowed down the reaction (even the carbonate complex is unstable, Table 2). Therefore, the yield in DMSO is low for 3h (30%) (Scheme 5, Table 4). The unfavorable electronic properties of phenol 1j were complemented by the steric influence of the methyl group, resulting in a low yield of 4j (27%) even in DMF (Scheme 5, Table 4).

Scheme 5.

HACAs from phenoxides carboxylation in solvents.

At the same time, the halogen at the 4-position of phenol 1k does not interfere with carboxylation at all. Under optimized conditions in DMF with 1b additive, 4k is obtained almost quantitatively (98%) (Scheme 5, Table 4). Though 1k is an ambiguous phenol (see Scheme 4), the ethyl group has sufficient steric effect for achieving complete regioselectivity. To compare the course of the classical solid-phase Kolbe-Schmitt reaction with 1k, we performed the reaction without solvent at 150–160 °C. The acid 4k (80%) was obtained for 2 h, but along with 1.8% of the regioisomeric ortho-acid. Clearly, milder carboxylation conditions in the solvent yield a cleaner reaction.

The carboxylation reaction of phenol 1l proceeds unambiguously but slowly, similarly to 1c, so the same conditions were used: MesONa 1b, DMF, and heating at 120 °C. As a result, acid 4l (70%) (Scheme 5, Table 4) was obtained and collected by simple filtration.

ortho-Cresol 1m was selectively carboxylated in DMSO using its cesium salt, and the para-acid 3m (57%) was isolated by chromatography. Perry and Kong reported similar effect of para-selectivity of cesium salt in carboxylation in DMF solution [33] (this paper appeared during our submission). Carboxylation of syringol salt 1n (together with guaiacol 1g, a product of lignin pyrolysis) in DMSO with 1b additive smoothly yielded acid 3n (73%). The unexpectedly lower yield in DMF of 3n (39%) is likely due to the salt’s poorer solubility in this solvent. It should be noted that solubility affects the reaction yield and should be taken into account.

The reaction of the meta-cresol salt 1o, carried out under our mild conditions, is highly indicative of selectivity. meta-Cresol is an ambiguous phenol and the observed earlier regioselectivity of its carboxylation was quite moderate—5.7:1 [25]. We believe this is due to the high reaction temperature. In our conditions, the reaction in DMF was very selective for the formation of 4o (99:1, 70%). Using 1b additive, the yield of 4o was increased to 92% while maintaining the high selectivity of 97:3 of the carboxylation (Scheme 5, Table 4).

Phenoxides derived from condensed aromatic systems—2-naphtholate 1p and 8-hydroxyquinolinate 1q—were tested under the developed conditions. Sodium naphtholate 1p yields acid 4p (96%) almost quantitatively at 70 °C in DMSO (Scheme 5, Table 4). After optimization of the reaction conditions (DMF with 1b additive), acid 4q (84%) was obtained from 1q in high yield, though previously the yield of 4q in DMF under atmospheric CO2 pressure was lower, 34% [34].

In our method, the reaction conditions are much milder than those of the classical Kolbe-Schmitt method. This allows us to carboxylate not only typical phenols but also more sensitive compounds containing chiral centers capable of racemization. Specifically, we synthesized enantiomerically pure Ellman homoallyl amide 1r from ortho-vanillin, converted it to the disodium salt, and carboxylated it in DMSO with 1b (Scheme 5, Table 4). The reaction proceeds unambiguously, but quite slowly with 1r, so we extended the reaction time to 24 h, yielding 3q in good yield (74%) without the formation of stereoisomeric products.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Synthesis of Sodium Phenoxides

3.1.1. Variation A (1f, 1g, 1m, 1n, 1p)

Sodium (569 mg, 24.8 mmol) was dissolved in dry MeOH (10 mL) from 0 to 25 °C. Phenol (25.0 mmol) was dissolved in a minimal volume of MeOH, then a MeONa solution was added. The solvent was distilled under reduced pressure (15 Torr) on a water bath (30 °C), then solid phenoxide salt was crushed into a powder under Ar. This powder was dried under vacuum (0.1 mbar) on an oil bath (200 °C) for 10 h. This extended heating is required to remove traces of phenols

3.1.2. Variation B (1c–1e, 1h–1l, 1o, 1q)

Under Ar atmosphere NaH (60% dispersion in mineral oil) (280 mg, 7.0 mmol) was washed trice with hexane (5 mL) to remove the oil. dry THF or DCM (10 mL) was added to the washed NaH powder, and phenol (7.0 mmol) was added portion wise. After 1 h, when H2 evolution was complete, the solvents were evaporated under reduced pressure (15 Torr), and sodium phenoxide was dried under vacuum (0.1 mbar) on an oil bath (200 °C) for 10 h. This extended heating is required to remove traces of phenols

3.2. Carboxylation Experimental Procedures

3.2.1. Standard Procedure for the Carboxylation of Sodium Phenoxide in DMSO

Under Ar atmosphere sodium phenoxide (1.0 mmol) was poured as a solid from a bulk dry salt into a small glass vessel (3 mL) equipped with a magnetic stirrer bar. Anhydrous DMSO (1 mL) was added, and the vessel was placed into a steel pressure reactor (V = 20 mL, Photo S1). The reactor was pressurized under 15 bar of CO2 and placed into an oil bath (100 °C) with stirring for 16 h. After the completion of the reaction, the reactor was cooled, and CO2 pressure was slowly released (≈10 min). NaHCO3 (sat. solution) (2 mL, 2.0 equiv.) was added to the reaction mixture, and organic impurities were removed by extraction with EtOAc (3 × 5 mL). The aqueous layer was acidified to pH = 1 with conc. HCl, and the product was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 5 mL). The combined organic extract was washed with NaCl (sat solution) (1 × 5 mL), dried over Na2SO4 and evaporated to dryness. The pure product was obtained by recrystallization or column chromatography.

3.2.2. Standard Procedure for the Carboxylation of Sodium Phenoxide in DMF

Under Ar atmosphere sodium phenoxide (1.0 mmol) was poured as a solid from a bulk dry salt into a small glass vessel (3 mL) equipped with a magnetic stirrer bar. Anhydrous DMF (155 µL, 2.0 mmol, 2.0 equiv.) was added, and the vessel was placed into a steel pressure reactor (V = 20 mL, Photo S1). The reactor was pressurized under 15 bar of CO2 and placed into an oil bath (100 °C) with stirring for 16 h. After the completion of the reaction, the reactor was cooled, and CO2 pressure was slowly released (≈10 min). NaHCO3 (sat. solution) (2 mL, 2.0 equiv.) and water (5 mL) were added to the reaction mixture, and organic impurities were removed by extraction with EtOAc (3 × 5 mL). The aqueous layer was acidified to pH = 1 with conc. HCl, and the product was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 5 mL). The combined organic extracts were washed with NaCl (sat solution) (1 × 5 mL), water (1 × 5 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated to dryness. The pure product was obtained by recrystallization or column chromatography.

3.3. Preparation and Carboxylation of a Chiral Ellman’s Sulfinamide with a Phenolic Group

3.3.1. Synthesis of Ellman’s Imine

ortho-Vanillin (2.28 g, 15.0 mmol), (S)-2-methyl-2-propanesulfinamide (1.87 g, 15.5 mmol) and Ti(OiPr)4 (17.1 g, 17.8 mL, 60.0 mmol) in THF (15 mL) were placed in a 50 mL flask under Ar. The flask was stoppered, and the solution was stirred while heating on an oil bath at 60 °C for 24 h. The resulting mixture was gradually poured into a mixture of water (180 mL) and DCM (50 mL) and stirred for 3 h until a yellowish precipitate formed. The resulting suspension was filtered through a Hyflo® Super-Cell® filter pad, the filter pad was carefully washed with DCM (3 × 20 mL). The organic phase was separated, the aqueous phase was extracted with DCM (20 mL), and the combined organic extracts were dried over MgSO4. The resulting solution was evaporated on a rotatory evaporator. The residual oil was recrystallized from hexane to give (S,E)-N-(2-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzylidene)-2-methylpropane-2-sulfinamide (3.38 g, 88%) as a beige solid, m.p. 118–120 °C (hexane), Rf 0.20 (hexane/EtOAc, 4:1). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 11.25 (s, 1H, OH), 8.67 (s, 1H, CH=N), 7.07 (dd, 1H, J = 7.8, 1.4 Hz, Ar), 7.02 (dd, 1H, J = 8.1, 1.0 Hz, Ar), 6.90 (t, 1H, J = 7.9 Hz, Ar), 3.89 (s, 3H, OMe), 1.22 (s, 9H, tBu) ppm. 13C NMR (CDCl3, 101 MHz): δ 165.4, 150.2, 148.4, 124.5, 119.5, 118.4, 116.0, 57.9, 56.2, 22.2 (3C) ppm. NMR spectra coincide with the literature data [35].

3.3.2. Copper(I)-Catalyzed Diastereoselective Allylation of Ellman’s Imine

Ellman’s imine (10.0 mmol) and Cu(PPh3)3Cl*MeCN (0.463 g, 0.5 mmol) were dissolved in THF (25 mL) under Ar. To this solution at −15 °C were added tBuOK solution (1.0 M in THF, 0.5 mL, 0.5 mmol), Et3N (3.02 g, 4.18 mL, 30.0 mmol) and triallylborane- 1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane adduct (1.23 g, 5.0 mmol, 0.5 equiv.) and the solution was stirred for 1.5 h at this temperature. A solution of MeOH (0.32 g, 0.4 mL, 10.0 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) in THF (10 mL) was added to the formed mixture via syringe pump over 1 h, after which the mixture was stirred for another 1 h and quenched with AcOH (3.0 mL, 50.0 mmol) at −15 °C. The mixture was diluted with EtOAc (15 mL) and a mixture of K2CO3 solution and 25% aq.NH3 (for copper extraction). The organic layer was separated and washed several times with a mixture of brine and 25% aq.NH3 until the blue coloration disappeared. The resulting extract was dried over MgSO4 and evaporated to give the crude homoallylamine as a viscous yellow oil. This product was purified by column chromatography (hexane/EtOAc 1:1) to afford (S)-N-((S)-1-(2-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)but-3-en-1-yl)-2-methylpropane-2-sulfinamide (2.56 g, 86%) as a white solid, m.p. 87–89 °C (hexane/EtOAc), Rf = 0.29 (hexane/EtOAc 1:1), de > 99% (NMR), [α]D25 + 40.3 (c 1.0, CHCl3). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 6.80–6.75 (m, 2H, Ar), 6.75–6.71 (m, 1H, Ar), 6.36 (s, 1H, OH), 5.69 (ddt, 1H, J = 17.2, 10.2, 7.0 Hz, CH=), 5.06–4.98 (m, 2H, CH2=), 4.51 (q, 1H, J = 7.3 Hz, CH), 4.20 (d, 1H, J = 7.7 Hz, NH), 3.79 (s, 3H, OMe), 2.74–2.67 (m, 1H, CH2), 2.61–2.54 (m, 1H, CH2), 1.20 (s, 9H, tBu) ppm. 13C NMR (CDCl3, 101 MHz): δ 146.9, 143.2, 135.0, 128.1, 120.1, 119.6, 117.4, 109.8, 57.3, 56.2, 55.9, 40.4, 22.8 (3C) ppm. Anal. Mr(C15H23NO3S) = 297.140, calcd: C, 60.58; H, 7.80; N, 4.71; found: C, 60.61; H, 7.92; N, 4.58.

3.3.3. Carboxylation of Ellman’s Phenolic Sulfinamide

Under Ar atmosphere NaH (60% dispersion in mineral oil) (120 mg, 3.0 mmol, 2.0 equiv.) was washed with n-hexane (3 × 3 mL) to remove oil. To the washed NaH were added THF (5 mL) and a solution of phenolic sulfonamide (446 mg, 1.5 mmol) in THF (5 mL). After 1 h, when H2 evolution ceased, the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure (15 Torr), and 1r was dried under vacuum (0.1 mbar) on an oil bath (100 °C) for 3 h, yielding 1r as a pale yellow solid. Under Ar atmosphere 1r (341 mg, 1.0 mmol), MesONa (158 mg, 1.0 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), and DMSO (1 mL) were placed into a steel pressure reactor (20 mL) equipped with a magnetic stirring bar. The reactor was sealed under 15 bar of CO2 and immersed into an oil bath (100 °C) with stirring for 24 h. The reaction mixture was cooled; the CO2 pressure was slowly released (≈10 min). NaHCO3 (sat. solution) (2 mL, 2 equiv.) was added to the reaction mixture, and organic impurities were removed by extraction with EtOAc (3 × 5 mL). The aqueous phase was acidified with AcOH (577 μL, 10 equiv.), and the product was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 5 mL). The combined organic extract was washed with NaCl (sat solution) (1 × 5 mL), dried over Na2SO4 and evaporated to dryness. The residue was purified by column chromatography (EtOAc) to give 3r (252 mg, 74%) as a pale beige solid. Rf = 0.15 (EtOAc), m.p. = 108–110 °C (EtOAc), [α]D25 + 132.3 (c 1.0, CHCl3). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): δ 12.52 (br.s, 1H, COOH), 9.57 (br.s, 1H, OH), 7.69 (d, 1H, J = 2.0 Hz, Ar), 7.35 (d, 1H, J = 1.9 Hz, Ar), 5.78–5.67 (m, 2H, CH= and NH), 5.02–4.94 (m, 2H, CH2=), 4.63 (td, 1H, J = 8.6, 5.8 Hz, CH), 3.84 (s, 3H, OMe), 2.50–2.43 (m, 1H, CH2), 2.38–2.31 (m, 1H, CH2), 1.08 (s, 9H, tBu) ppm. 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 101 MHz): δ 167.5, 147.2, 146.6, 135.6, 130.3, 122.3, 121.0, 116.9, 110.4, 55.8, 55.7, 53.1, 40.9, 22.6 (3C) ppm. Anal. Mr(C16H23NO5S) = 341.130, calcd: C, 56.29; H, 6.79; N, 4.10; found: C, 56.20; H, 6.82; N, 4.08.

4. Conclusions

As a result of the current investigation, we have developed a method for gentle, efficient, and homogeneous carboxylation of phenoxides using the Kolbe-Schmitt reaction. Novel fundamental data on the reactivity of alkali metal phenoxides in DMSO and DMF were obtained, including concentration-dependent regioselectivity of the carboxylation. Especially interesting were record values of para-regioselectivity on carboxylation of rubidium and cesium salts of phenoxides in DMSO (SA was not detected at low concentrations of phenoxide). The use of sodium mesitolate as a promoting additive provides higher chemical yield of a variety of hydroxyaromatic acids, including heterocyclics. Under optimized conditions we achieved nearly quantitative yields of hydroxyaromatic acids with several substrates, confirming the effectiveness and practicality of our method.

Furthermore, we utilized our developed method to record 13C NMR spectra of carbonate complexes of substituted phenoxides in DMSO solution for the first time, including the chemical shift in the carboxylate carbon, the least intense signal in the spectra. By studying DOSY spectra of phenoxides alongside calibration standards, we identified molecular associates which are suggested to be responsible for the most rapid carboxylation in solution.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/molecules31020239/s1, experimental details; NMR spectra are available in the supporting information file. Table S1. Required volumes of DMSO and PhOM solutions. Photo S1. Left: Small steel pressure reactors (V = 20 mL). Right: A large steel pressure reactor for a multi-vial reaction (V = 700 mL). Photo S2. Concentrated solutions of PhOCs (left) and PhOLi*CO2 (right) at 3.0 M concentration in DMSO. Scheme S1. Gas measuring apparatus. Table S2. Required volumes of DMSO and PhONa solutions. Figure S1. Dependence of the logarithm of the diffusion coefficient on the logarithm of the molecular weight at C(PhONa) = 0.036 M. Figure S2. Dependence of the logarithm of the diffusion coefficient on the logarithm of the molecular weight at C(PhONa) = 0.143 M. Figure S3. Dependence of the logarithm of the diffusion coefficient on the logarithm of the molecular weight at C(PhONa) = 0.250 M. Figure S4. Dependence of the logarithm of the diffusion coefficient on the logarithm of the molecular weight at C(PhONa) = 0.357 M. Table S3. Calculation of diffusion coefficients and molecular weights. Refs. [25,26,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46] are cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

N.Y.K., conceptualization, methodology, supervision, investigation, and writing—original draft and editing; A.L.M. and I.P.B., project administration, resources, D.A.M. and M.S.A., methodology, data curation, formal analysis, validation, visualization, writing—review and editing; M.A.T., registration of NMR spectra; review and editing; D.G.Y. data curation, formal analysis, review and editing; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a grant from the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation, grant number 075-15-2024-646.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

This work was performed using the equipment of the Shared Research Center—Analytical center of deep oil processing and petrochemistry of TIPS RAS.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Artz, J.; Mu, T.E.; Thenert, K.; Kleinekorte, J.; Meys, R.; Sternberg, A.; Bardow, A. Sustainable Conversion of Carbon Dioxide: An Integrated Review of Catalysis and Life Cycle Assessment. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 434–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aresta, M. (Ed.) Carbon Dioxide as Chemical Feedstock; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; ISBN 9783527324750. [Google Scholar]

- Aresta, M.; Dibenedetto, A.; Angelini, A. Catalysis for the Valorization of Exhaust Carbon: From CO2 to Chemicals, Materials, and Fuels. Technological Use of CO2. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 1709–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olah, G.A.; Goepper, A.; Prakash, G.K.S. Beyond Oil and Gas: The Methanol Economy; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tortajada, A.; Juliá-Hernández, F.; Börjesson, M.; Moragas, T.; Martin, R. Transition-Metal-Catalyzed Carboxylation Reactions with Carbon Dioxide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 15948–15982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S. (Ed.) CO2 as a Building Block in Organic Synthesis; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsov, N.Y.; Maximov, A.L.; Beletskaya, I.P. Novel Technological Paradigm of the Application of Carbon Dioxide as a C1 Synthon in Organic Chemistry: I. Synthesis of Hydroxybenzoic Acids, Methanol, and Formic Acid. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 58, 1681–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolbe, H. Ueber Synthese Der Salicylsäure. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1860, 113, 125–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, R. Beitrag Zur Kenntniss Der Kolbe’schen Salicylsäure Synthese. J. Für Prakt. Chem. 1885, 31, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, A.S.; Jeskey, H. The Kolbe-Schmitt Reaction. Chem. Rev. 1957, 57, 583–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, O.; Onwudili, J.A.; Yuan, Q. A Critical Review of the Production of Hydroxyaromatic Carboxylic Acids as a Sustainable Method for Chemical Utilisation and Fixation of CO2. RSC Sustain. 2023, 1, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergeev, E.E.; Rodikova, Y.A.; Zhizhina, E.G. Salicylic Acid Synthesis Methods: A Review. Catal. Ind. 2024, 16, 312–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritzer, E.; Sundermann, R. Hydroxycarboxylic Acids, Aromatic. In Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Boullard, O.; Leblanc, H.; Besson, B. Salicylic Acid. In Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tiefenbacher, K.; Gollner, A.; Mulzer, J. Syntheses and Antibacterial Properties of Iso-Platencin, Cl-Iso-Platencin and Cl-Platencin: Identification of a New Lead Structure. Chem. A Eur. J. 2010, 16, 9616–9622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadem, S.; Marles, R.J. Monocyclic Phenolic Acids; Hydroxy- and Polyhydroxybenzoic Acids: Occurrence and Recent Bioactivity Studies. Molecules 2010, 15, 7985–8005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekinci, D.; Şentürk, M.; Küfrevioğlu, Ö.İ. Salicylic Acid Derivatives: Synthesis, Features and Usage as Therapeutic Tools. Expert. Opin. Ther. Pat. 2011, 21, 1831–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manuja, R.; Sachdeva, S.; Jain, A.; Chaudhary, J. A Comprehensive Review on Biological Activities of P-Hydroxy Benzoic Acid. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2013, 22, 109–115. [Google Scholar]

- López-Herrador, S.; Corral-Sarasa, J.; González-García, P.; Morillas-Morota, Y.; Olivieri, E.; Jiménez-Sánchez, L.; Díaz-Casado, M.E. Natural Hydroxybenzoic and Hydroxycinnamic Acids Derivatives: Mechanisms of Action and Therapeutic Applications. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meek, W.H.; Fuchsman, C.H. Carboxylation of Substituted Phenols in N,N-Dimethylamide Solvents at Atmospheric Pressure. J. Chem. Eng. Data 1969, 14, 388–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirao, I. Use of Carbon Dioxide in Industrial Organic Chemistry—The Behavior of Carbon Dioxide in the Kolbe-Schmitt Reaction. J. Synth. Org. Chem. Jpn. 1976, 34, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosugi, Y.; Imaoka, Y.; Gotoh, F.; Rahim, M.A.; Matsui, Y.; Sakanishi, K. Carboxylations of Alkali Metal Phenoxides with Carbon Dioxide. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2003, 1, 817–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosugi, Y.; Rahim, M.A.; Takahashi, K.; Imaoka, Y.; Kitayama, M. Carboxylation of Alkali Metal Phenoxide with Carbon Dioxide at Terrestrial Temperature. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2000, 14, 841–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierbaumer, S.; Nattermann, M.; Schulz, L.; Zschoche, R.; Erb, T.J.; Winkler, C.K.; Tinzl, M.; Glueck, S.M. Enzymatic Conversion of CO2: From Natural to Artificial Utilization. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 5702–5754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Preciado, S.; Xie, P.; Larrosa, I. Carboxylation of Phenols with CO2 at Atmospheric Pressure. Chem. A Eur. J. 2016, 22, 6798–6802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merzliakov, D.A.; Alexeev, M.S.; Topchiy, M.A.; Yakhvarov, D.G.; Kuznetsov, N.Y.; Maximov, A.L.; Beletskaya, I.P. Development of Homogeneous Carboxylation of Phenolates via Kolbe–Schmitt Reaction. Molecules 2025, 30, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kloss, A.A.; Ronald Fawcett, W. ATR-FTIR Studies of Ionic Solvation and Ion-Pairing in Dimethyl Sulfoxide Solutions of the Alkali Metal Nitrates. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1998, 94, 1587–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Bagchi, B. Ion Diffusion Captures Composition-Dependent Anomalies in Water–DMSO Binary Mixtures. J. Chem. Phys. 2024, 160, 114505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcus, Y.; Hefter, G. Standard Partial Molar Volumes of Electrolytes and Ions in Nonaqueous Solvents. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 3405–3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutmann, V. Empirical parameters for donor and acceptor properties of solvents. Electrochim. Acta 1976, 21, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunert, M.; Dinjus, E.; Nauck, M.; Sieler, J. Structure and Reactivity of Sodium Phenoxide—Following the Course of the Kolbe-Schmitt Reaction. Chem. Ber. 1997, 130, 1461–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirao, I.; Kito, T. Carboxylation of Phenol Derivatives. XXI. The Formation Reaction of the Complex from Alkali Phenoxide and Carbon Dioxide. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1973, 46, 3470–3474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Perry, G.J.P.; Kong, D. A Para-Selective Kolbe–Schmitt Reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, e22503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nycz, J.E.; Malecki, G.J. Synthesis, Spectroscopy and Computational Studies of Selected Hydroxyquinoline Carboxylic Acids and Their Selected Fluoro-, Thio-, and Dithioanalogues. J. Mol. Struct. 2013, 1032, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Ren, X.; Liu, H.; Tang, Z. Study on Synthesis of Ortho-Hydroxyl Aromatic N-Tert-Butylsulfinyl Imines Under Microwave Irradiation. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 34, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayama, T.; Kitamura, M.; Kobayashi, Y.; Arakawa, Y.; Kudo, K. Synthesis of Alq3-Pendent Soluble Polymers and Their Application to Organic Light Emitting Diode. Kobunshi Ronbunshu 2006, 63, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexeev, M.S.; Strelkova, T.V.; Ilyin, M.M.; Nelyubina, Y.V.; Bespalov, I.A.; Medvedev, M.G.; Khrustalev, V.N.; Kuznetsov, N.Y. Amine Adducts of Triallylborane as Highly Reactive Allylborating Agents for Cu(I)-Catalyzed Allylation of Chiral Sulfinylimines. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2024, 22, 4680–4696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuznetsov, N.Y.; Tikhov, R.M.; Strelkova, T.V.; Bubnov, Y.N. Dimethylamine Adducts of Allylic Triorganoboranes as Effective Reagents for Petasis-Type Homoallylation of Primary Amines with Formaldehyde. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2018, 16, 7115–7119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borys, A.M. An Illustrated Guide to Schlenk Line Techniques. Organometallics 2023, 42, 182–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burfield, D.R.; Smithers, R.H. Desiccant Efficiency in Solvent Drying. 3. Dipolar Aprotic Solvents. J. Org. Chem. 1978, 43, 3966–3968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Wu, N.; Zhang, S.; Xi, P.; Su, X.; Lan, J.; You, J. Synthesis of Phenol, Aromatic Ether, and Benzofuran Derivatives by Copper-Catalyzed Hydroxylation of Aryl Halides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 8729–8732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gevorgyan, V. General Method for the Synthesis of Salicylic Acids from Phenols Through Palladium-Catalyzed Silanol-Directed C—H Carboxylation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 2255–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheurer, A.; Mosset, P.; Bauer, W.; Saalfrank, R.W. A Practical Route to Regiospecifically Substituted (R)- and (S)-Oxazolylphenols. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 2001, 3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, K.; Fan, A.; Dai, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, M.; Yao, X. Selective Demethylation and Debenzylation of Aryl Ethers by Magnesium Iodide Under Solvent-Free Conditions and Its Application to the Total Synthesis of Natural Products. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009, 7, 5084–5090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques Dit Lapierre, T.J.W.; Cruz, M.G.F.D.M.L.; Brito, N.P.F.; Resende, D.D.M.; Souza, F.D.O.; Pilau, E.J.; da Silva, M.F.B.; Neves, B.J.; Murta, S.M.F.; Rezende Júnior, C.D.O. Hit-to-Lead Optimization of a Pyrazinylpiperazine Series Against Leishmania Infantum and Leishmania Braziliensis. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 256, 115445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Huang, K. Identification of Antioxidants from Taraxacum Mongolicum by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography–Diode Array Detection–Radical-Scavenging Detection–Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Experiments. J. Chromatogr. A 2008, 1209, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.