Release of Bioactive Peptides from Whey Protein During In Vitro Digestion and Their Effect on CCK Secretion in Enteroendocrine Cells: An In Silico and In Vitro Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Effect of In Vitro Digestion on WPC Proteins and Free Amino Acid Release

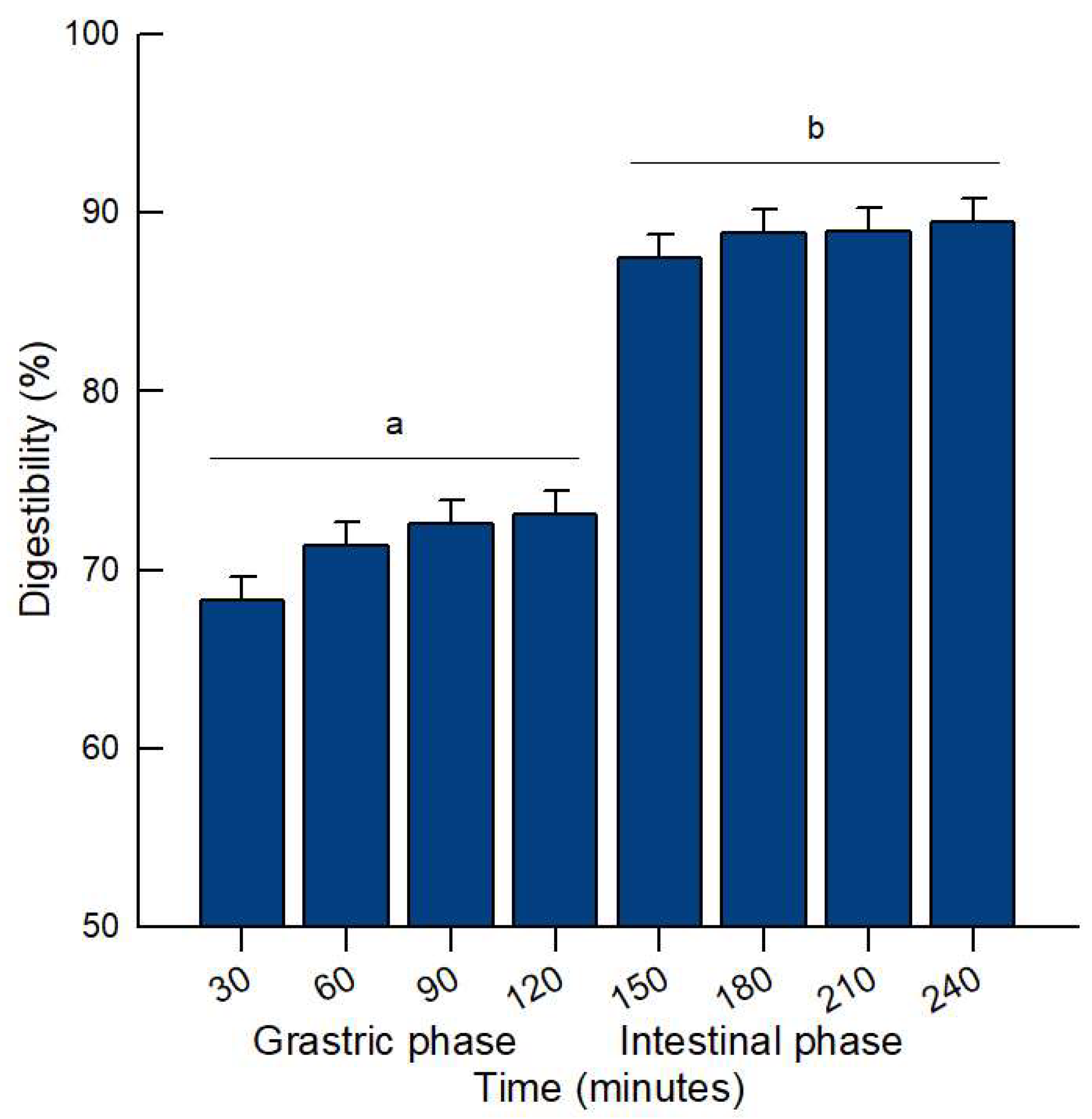

2.1.1. In Vitro Digestibility

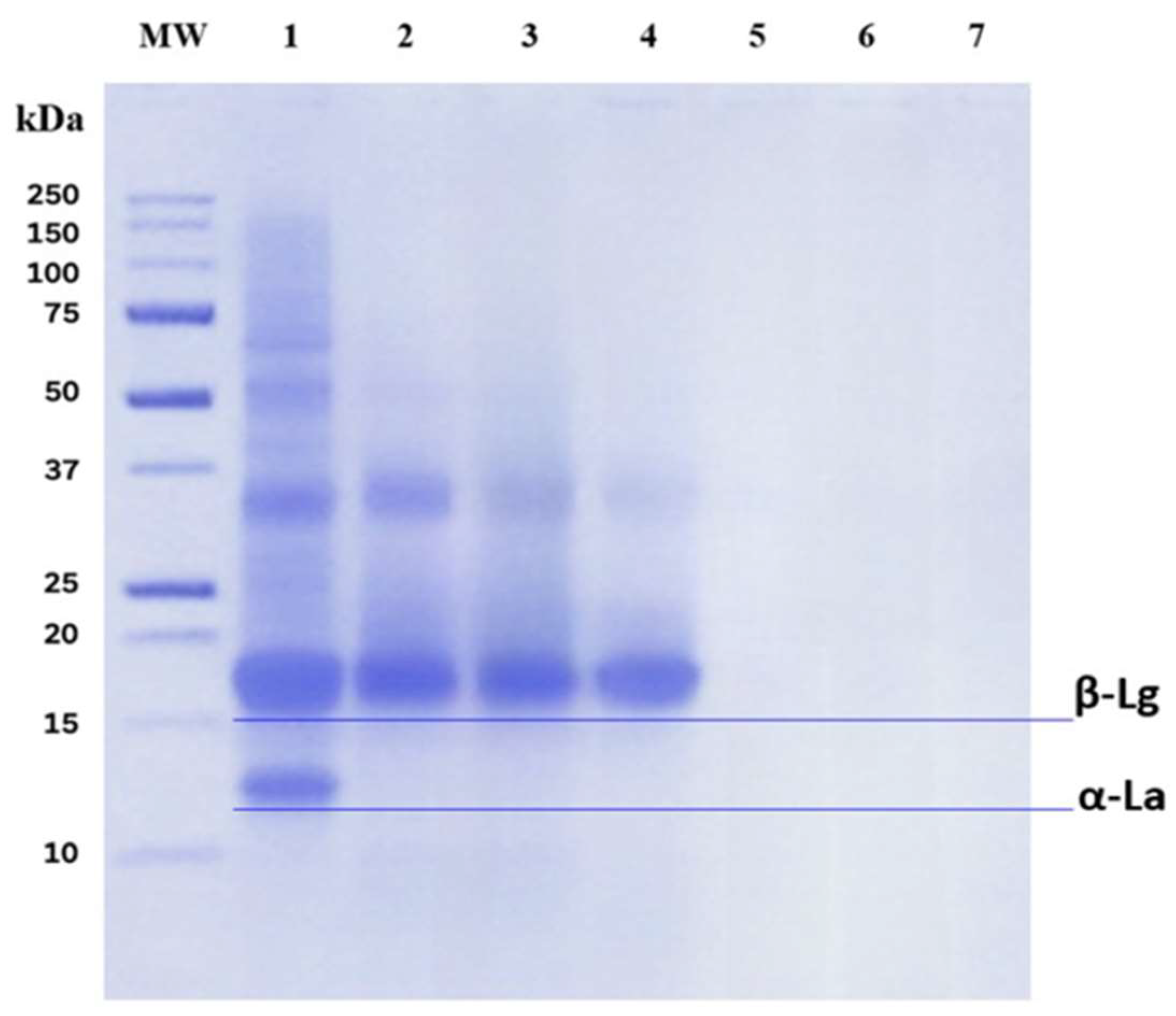

2.1.2. SDS–PAGE

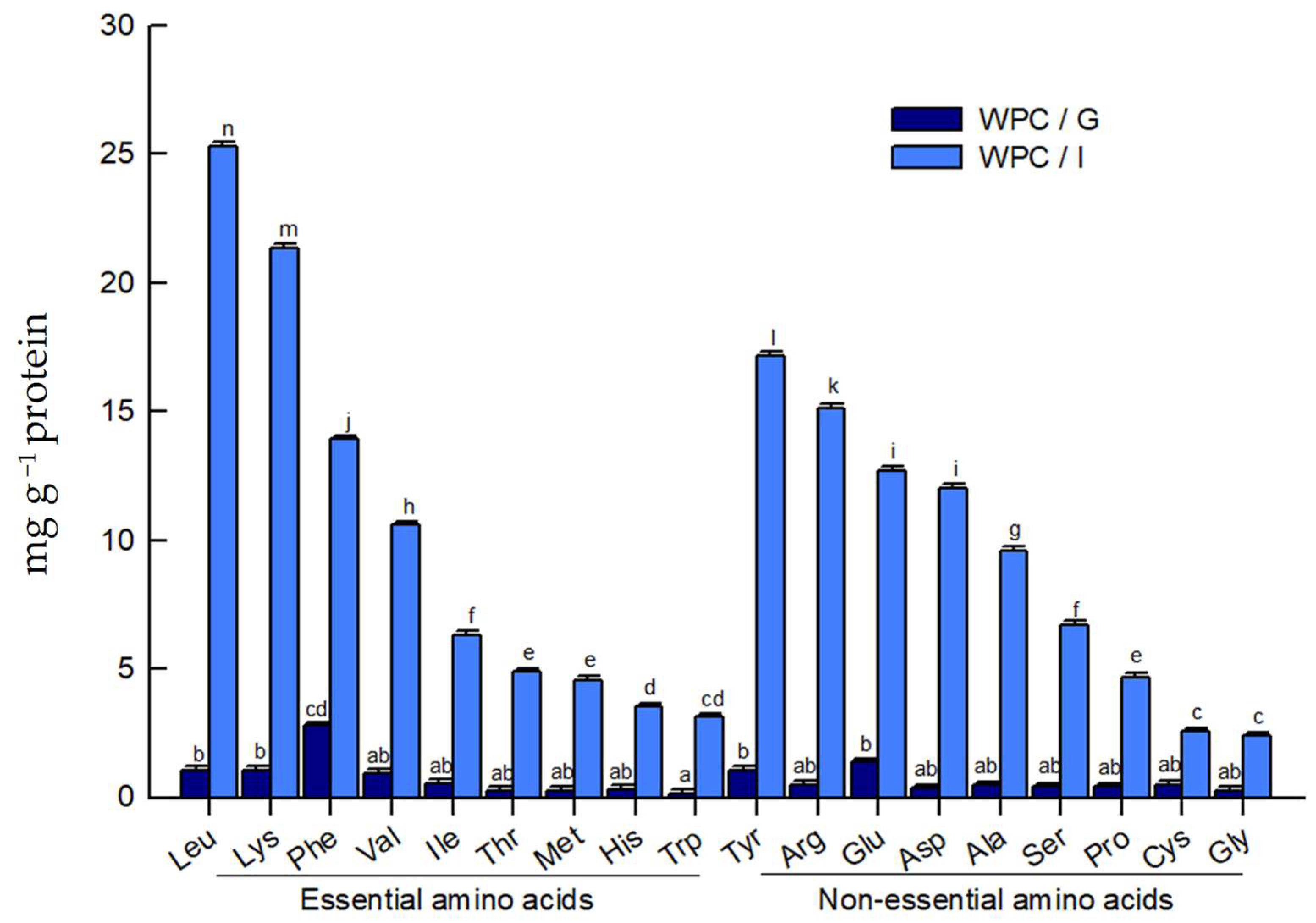

2.1.3. Free Amino Acids in Digests

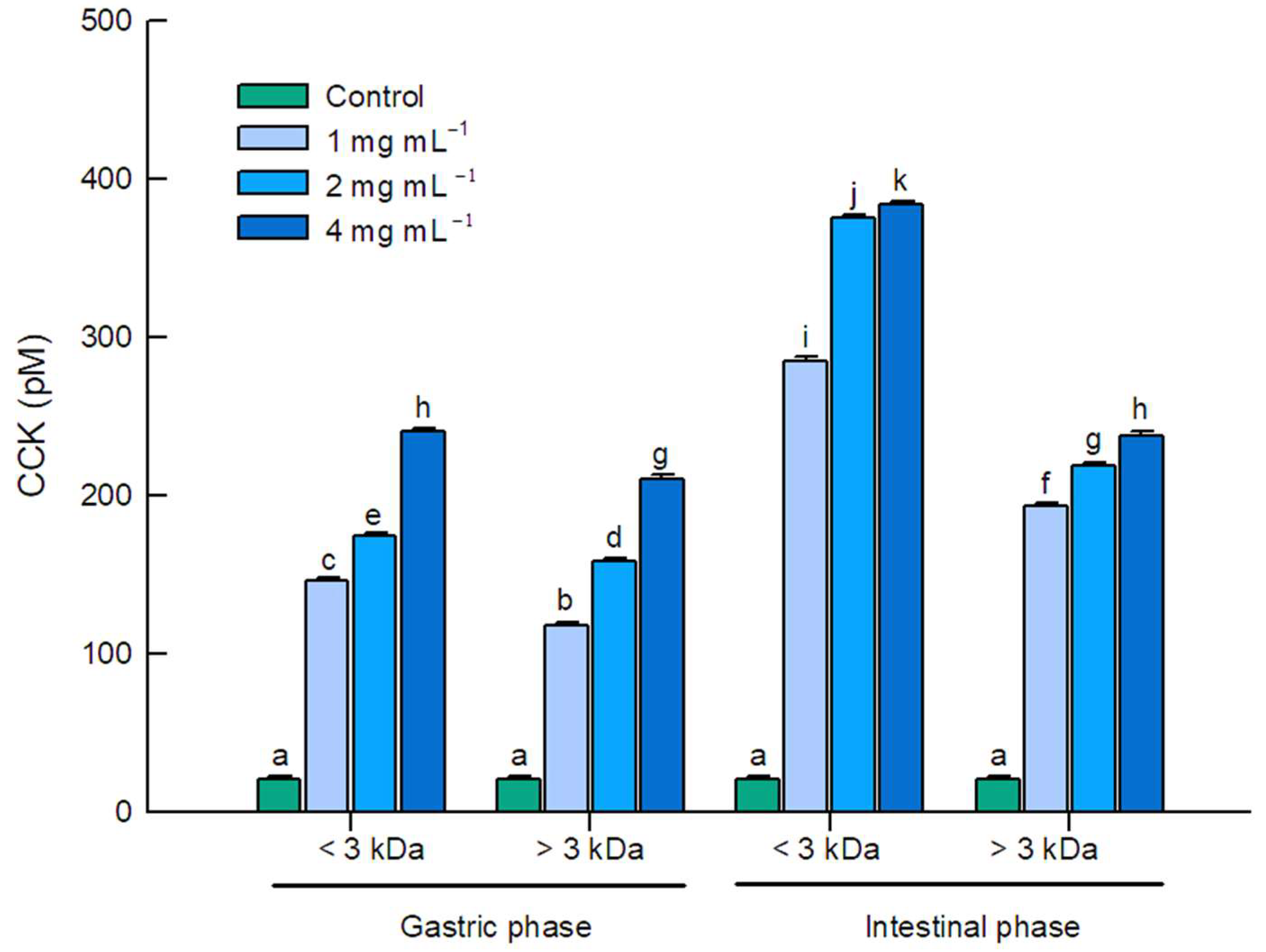

2.2. CCK Secretion in STC–1 Cells Induced by Whey Protein Digests

2.3. Peptides Released During In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion of WPC

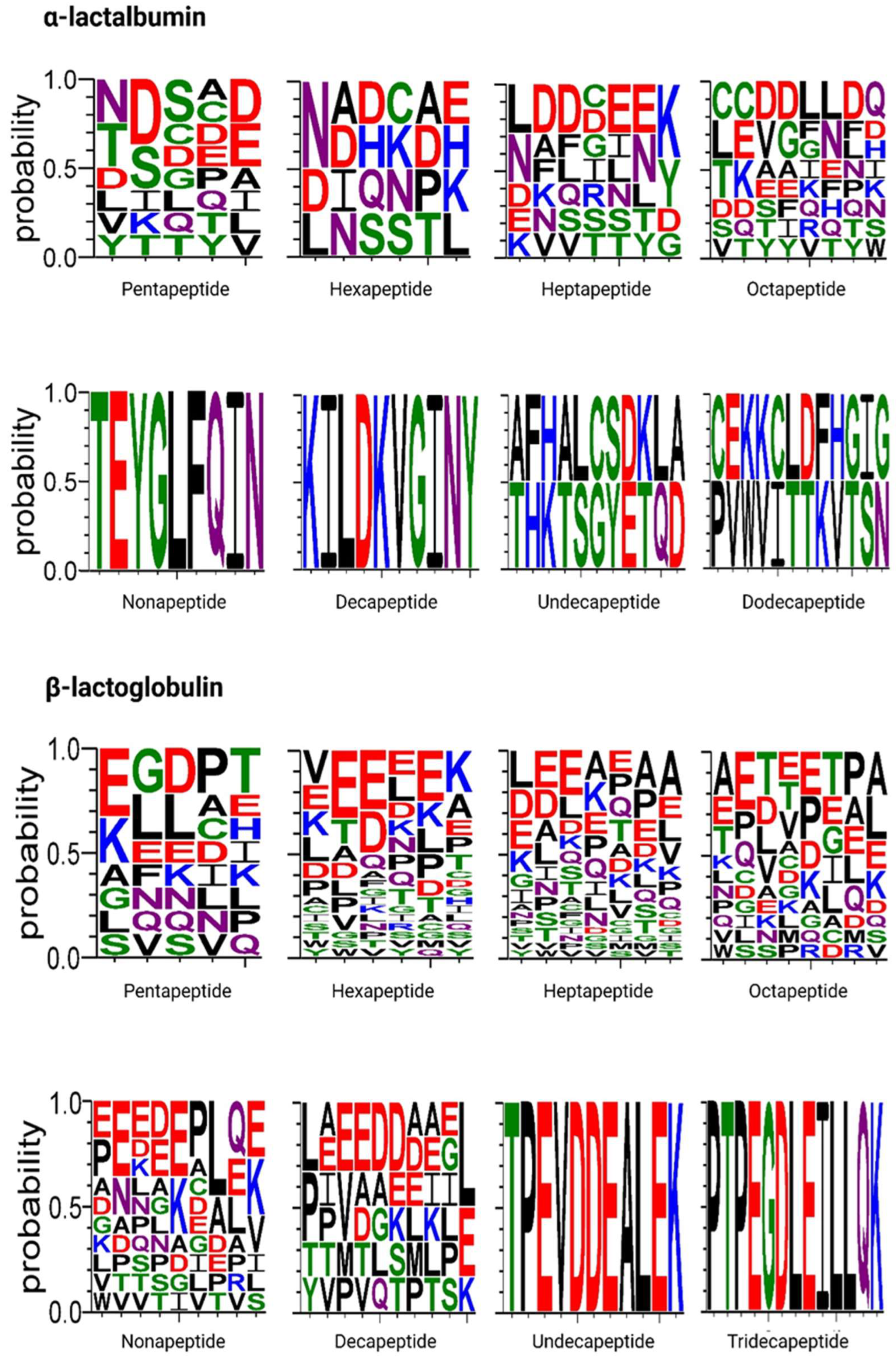

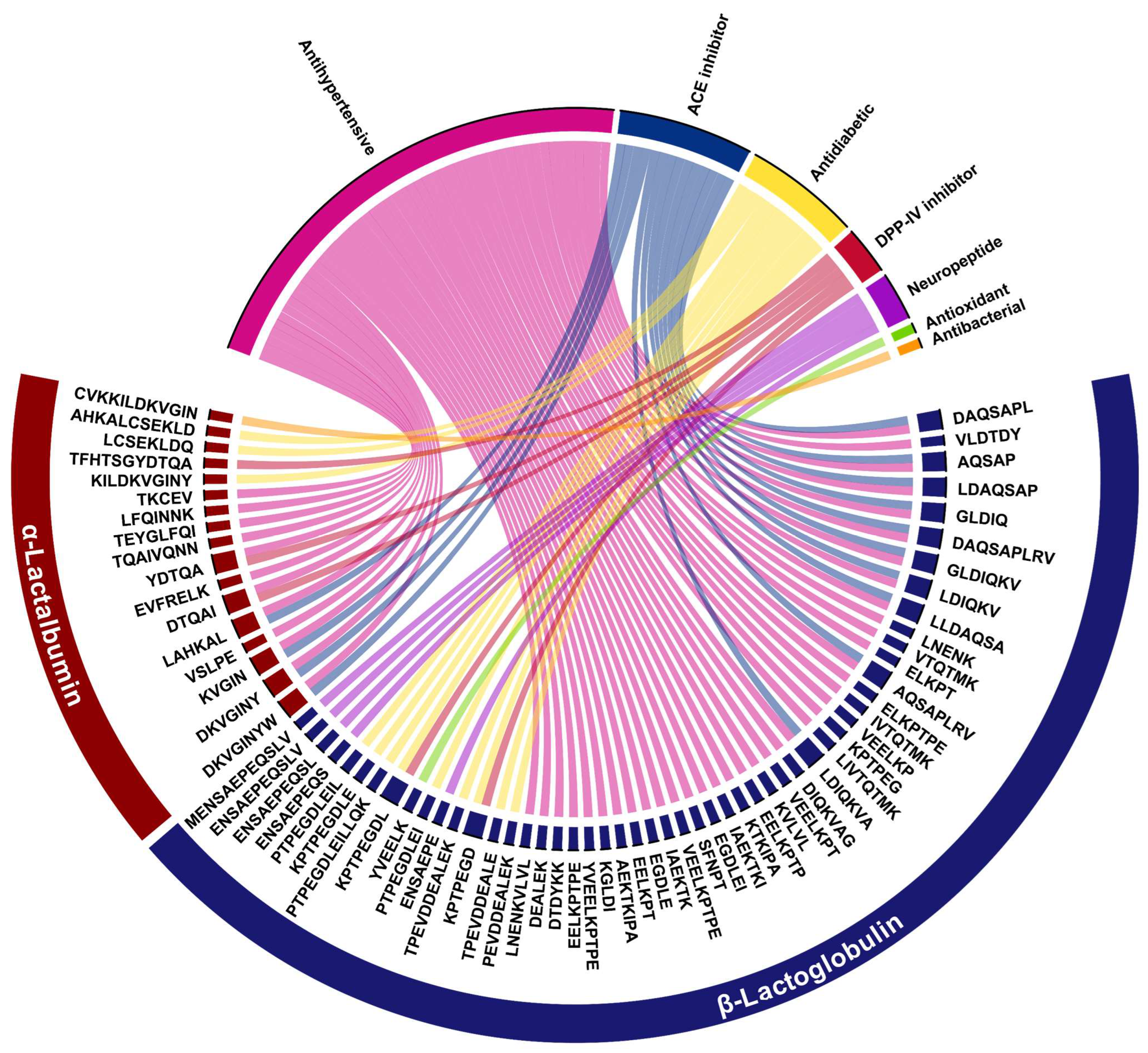

2.4. In Silico Bioactivity Profiling of Whey-Derived Peptides

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion of Whey Protein Concentrate

3.3. Fractionation of Digests by Ultrafiltration

3.4. In Vitro Protein Digestibility

3.5. Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate–Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE)

3.6. Free Amino Acid Analysis

3.7. Cell Assays

3.8. Assessment of Cellular Viability

3.9. CCK Secretion Study

3.10. Peptide Identification by Tandem Mass Spectrometry (HPLC–MS/MS)

3.11. In Silico Analysis of Peptide Bioactivity

3.12. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AA | Amino acids |

| AP | Protein content after in vitro digestion |

| ATCC | American Type Culture Collection |

| BP | Protein content before in vitro digestion |

| BSA | Bovine serum albumin |

| CaSR | Calcium-sensing receptor |

| CCK | Cholecystokinin |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium |

| DPP-IV | Dipeptidyl peptidase-IV |

| EECs | Enteroendocrine cells |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| FDR | False discovery rate |

| GLP-1 | Glucagon-like peptide-1 |

| GPCR | G protein–coupled receptor |

| CID | Collision-induced dissociation |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| LC–MS/MS | Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry |

| MWCO | Molecular weight cut-off |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PYY | Peptide YY |

| SDS–PAGE | Sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis |

| STC-1 | Murine enteroendocrine cell line (ATCC CRL-3254) |

| WPC | Whey protein concentrate |

| α-La | α-lactalbumin |

| β-Lg | β-lactoglobulin |

References

- Cifuentes, L.; Acosta, A. Homeostatic Regulation of Food Intake. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2022, 46, 101794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, G.S.; Page, A.J.; Eldeghaidy, S. The Gut-Brain Axis in Appetite, Satiety, Food Intake, and Eating Behavior: Insights from Animal Models and Human Studies. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2024, 12, e70027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Arshad, M.T.; Maqsood, S.; Ikram, A.; Gnedeka, K.T. Gut-Brain Axis in Obesity: How Dietary Patterns Influ-ence Psychological Well-Being and Metabolic Health? Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marić, G.; Gazibara, T.; Zaletel, I.; Labudović Borović, M.; Tomanović, N.; Ćirić, M.; Puškaš, N. The Role of Gut Hormones in Appetite Regulation. Acta Physiol. Hung. 2014, 101, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Hernández, M.; Miralles, B.; Amigo, L.; Recio, I. Intestinal Signaling of Proteins and Digestion-Derived Products Relevant to Satiety. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 10123–10131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morell, P.; Fiszman, S. Revisiting the Role of Protein-Induced Satiation and Satiety. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 68, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, G.; Schellekens, H.; Cuesta-Marti, C.; Maneschy, I.; Ismael, S.; Cuevas-Sierra, A.; Martínez, J.A.; Silvestre, M.P.; Marques, C.; Moreira-Rosário, A.; et al. A Menu for Microbes: Unraveling Appetite Regula-tion and Weight Dynamics through the Microbiota-Brain Connection across the Lifespan. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2025, 328, G206–G228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignot-Gutiérrez, A.; Serena-Romero, G.; Guajardo-Flores, D.; Alvarado-Olivarez, M.; Martínez, A.J.; Cruz-Huerta, E. Proteins and Peptides from Food Sources with Effect on Satiety and Their Role as Anti-Obesity Agents: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.-P.; Raybould, H.E. Estrogen and Gut Satiety Hormones in Vagus–Hindbrain Axis. Peptides 2020, 133, 170389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Liu, M.; Li, Y. Role of Plant-Derived Protein Hydrolysates and Peptides in Appetite Regulation. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 159, 104976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizarroso, N.A.; Martín, D.; Ramos, S. A Review on the Role of Food-Derived Bioactive Molecules in Satiety. Nutrients 2021, 13, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Hernández, M.; Vivanco-Maroto, S.M.; Miralles, B.; Recio, I. Food Peptides as Inducers of CCK and GLP-1 Secretion and GPCRs Involved in Enteroendocrine Cell Signalling. Food Chem. 2023, 402, 134225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulug, E.; Acikgoz Pinar, A.; Yildiz, B.O. Impact of Ultra-Processed Foods on Hedonic and Homeostatic Appetite Regulation: A Systematic Review. Appetite 2025, 213, 108139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walzem, R.L.; Dillard, C.J.; German, J.B. Whey Components: Millennia of Evolution Create Functionalities for Mammalian Nutrition: What We Know and What We May Be Overlooking. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2002, 42, 353–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.; Lee, S.-J.; Rutherfurd-Markwick, K.J. Sports and Exercise Supplements. In Whey Proteins; Boland, M., Singh, H., Eds.; Academic Press/Elsevier: London, UK, 2019; pp. 579–635. ISBN 978-0-12-812124-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, M.; Cheng, S.; Lu, W.; Du, M. Advancement and Prospects of Bioinformatics Analysis for Studying Bioactive Peptides from Food-Derived Protein: Sequence, Structure, and Functions. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2018, 105, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintieri, L.; Ladisa, G.; Vito, D.; Caputo, L.; Schirinzi, W.; De Bellis, F.; Smiriglia, L.; Monaci, L. Unraveling the Biological Properties of Whey Peptides and Their Potential in Health Promotion. Nutrients 2025, 17, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luparelli, A.; Trisciuzzi, D.; Schirinzi, W.M.; Caputo, L.; Smiriglia, L.; Quintieri, L.; Nicolotti, O.; Monaci, L. Whey Proteins and Bioactive Peptides: Advances in Production, Selection and Bioactivity Profiling. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansinhbhai, C.H.; Sakure, A.; Liu, Z.; Maurya, R.; Das, S.; Basaiawmoit, B.; Bishnoi, M.; Kondepudi, K.K.; Padhi, S.; Rai, A.K.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory, ACE Inhibitory, Antioxidative Activities and Release of Novel Antihypertensive and Antioxidative Peptides from Whey Protein Hydrolysate with Molecular Interactions. J. Am. Nutr. Assoc. 2022, 41, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumny, E.H.; Kempka, A.P. Bioactive Whey Peptides: A Bibliometric and Functional Overview. Discov. Food 2025, 5, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, G.H.; Tecimer, S.N.; Shah, D.; Zafar, T.A. Protein Source, Quantity, and Time of Consumption Determine the Effect of Proteins on Short-Term Food Intake in Young Men. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 3011–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tulipano, G.; Faggi, L.; Cacciamali, A.; Caroli, A.M. Whey Protein-Derived Peptide Sensing by Enteroendocrine Cells Compared with Osteoblast-like Cells: Role of Peptide Length and Peptide Composition, Focussing on Products of β-Lactoglobulin Hydrolysis. Int. Dairy J. 2017, 72, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morena, F.; Cencini, C.; Calzoni, E.; Martino, S.; Emiliani, C. A Novel Workflow for In Silico Prediction of Bioactive Peptides: An Exploration of Solanum lycopersicum By-Products. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez Longarela, N.; Paredes Ramos, M.; López Vilariño, J.M. Bioinformatics Tools for the Study of Bioactive Peptides from Vegetal Sources: Evolution and Future Perspectives. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 3476–3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Toalá, J.E.; Cruz-Narváez, Y.; Quintanar-Guerrero, D.; Liceaga, A.M.; Zambrano-Zaragoza, M.L. In Silico Bioactivity Analysis of Peptide Fractions Derived from Brewer’s Spent Grain Hydrolysates. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 2804–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbacz, K.; Wawrzykowski, J.; Czelej, M.; Waśko, A. In Silico Proteomic Profiling and Bioactive Peptide Potential of Rapeseed Meal. Foods 2025, 14, 2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles, B.; Del Barrio, R.; Cueva, C.; Recio, I.; Amigo, L. Dynamic Gastric Digestion of a Commercial Whey Protein Concentrate. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 1873–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Huang, F.; Zhao, Y.; Ouyang, K.; Xie, H.; Xiong, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, Q. Slow-Digestive Yeast Protein Concentrate: An Investigation of Its In Vitro Digestibility and Digestion Behavior. Food Res. Int. 2023, 174, 113572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tulipano, G. Role of Bioactive Peptide Sequences in the Potential Impact of Dairy Protein Intake on Metabolic Health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulet-Cabero, A.I.; Torcello-Gómez, A.; Saha, S.; Mackie, A.R.; Wilde, P.J.; Brodkorb, A. Impact of Caseins and Whey Proteins Ratio and Lipid Content on In Vitro Digestion and Ex Vivo Absorption. Food Chem. 2020, 319, 126514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Accardo, F.; Prandi, B.; Terenziani, F.; Tedeschi, T.; Sforza, S. Evaluation of In Vitro Whey Protein Digestibility in a Protein–Catechins Model System Mimicking Milk Chocolate: Interaction with Flavonoids Does Not Hinder Protein Bioaccessibility. Food Res. Int. 2023, 169, 112888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchón, J.; Fernández-Tomé, S.; Miralles, B.; Hernández-Ledesma, B.; Tomé, D.; Gaudichon, C.; Recio, I. Protein Degradation and Peptide Release from Milk Proteins in Human Jejunum: Comparison with In Vitro Gastrointestinal Simulation. Food Chem. 2018, 239, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.; Li, J.; Dai, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, T. Digestibility of Polymerized Whey Protein Using In Vitro Digestion Model and Antioxidative Property of Its Hydrolysate. Food Biosci. 2021, 42, 101109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Tomé, S.; Hernández-Ledesma, B. Gastrointestinal Digestion of Food Proteins under the Effects of Released Bioactive Peptides on Digestive Health. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2020, 64, 2000401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hira, T.; Nakajima, S.; Eto, Y.; Hara, H. Calcium-Sensing Receptor Mediates Phenylalanine-Induced Cholecystokinin Secretion in Enteroendocrine STC-1 Cells. FEBS J. 2008, 275, 4620–4626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elovaris, R.A.; Hutchison, A.T.; Lange, K.; Horowitz, M.; Feinle-Bisset, C.; Luscombe-Marsh, N.D. Plasma Free Amino Acid Responses to Whey Protein and Their Relationships with Gastric Emptying, Blood Glucose- and Appetite-Regulatory Hormones and Energy Intake in Lean Healthy Men. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigamonti, A.E.; Leoncini, R.; De Col, A.; Tamini, S.; Cicolini, S.; Abbruzzese, L.; Cella, S.G.; Sartorio, A. The Appetite-Suppressant and GLP-1-Stimulating Effects of Whey Proteins in Obese Subjects Are Associated with Increased Circulating Levels of Specific Amino Acids. Nutrients 2020, 12, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Cheng, C.Y.; Sun, X.; Pedicone, A.J.; Mahamadzadeh, M.; Cheng, S.X. The Extracellular Calcium-Sensing Receptor in the Intestine: Evidence for Regulation of Colonic Absorption, Secretion, Motility, and Immunity. Front. Physiol. 2016, 7, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caron, J.; Cudennec, B.; Domenger, D.; Belguesmia, Y.; Flahaut, C.; Kouach, M.; Lesage, J.; Goossens, J.-F.; Dhulster, P.; Ravallec, R. Simulated GI Digestion of Dietary Protein: Release of New Bioactive Peptides Involved in Gut Hormone Secretion. Food Res. Int. 2016, 89, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geraedts, M.C.P.; Troost, F.J.; Fischer, M.A.J.G.; Edens, L.; Saris, W.H.M. Direct Induction of CCK and GLP-1 Release from Murine Endocrine Cells by Intact Dietary Proteins. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2011, 55, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Moya, T.; Planes-Muñoz, D.; Frontela-Saseta, C.; Ros-Berruezo, G.; López-Nicolás, R. Milk Whey from Different Animal Species Stimulates the In Vitro Release of CCK and GLP-1 through a Whole Simulated Intestinal Digestion. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 7208–7216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Xue, L.; Fu, Q.; Wang, H.Y.; Cao, H.; Huang, K.; Guan, X. Novel Cholecystokinin Secretion-Stimulating Pep-tides from Oat Protein Hydrolysate: Sequence Identification and Insight into the Mechanism of Action. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 10998–11006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutrou, R.; Gaudichon, C.; Dupont, D.; Jardin, J.; Airinei, G.; Marsset-Baglieri, A.; Benamouzig, R.; Tomé, D.; Leonil, J. Sequential Release of Milk Protein–Derived Bioactive Peptides in the Jejunum in Healthy Humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 97, 1314–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos-Hernández, M.; Amigo, L.; Recio, I. Induction of CCK and GLP-1 release in enteroendocrine cells by egg white peptides generated during gastrointestinal digestion. Food Chem. 2020, 329, 127188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivanco-Maroto, S.M.; Gómez-Marín, C.; Recio, I.; Miralles, B. Milk Peptides Found in Human Jejunum Induce Enteroendocrine Hormone Secretion and Inhibit DPP-IV. Food Funct. 2025, 16, 5301–5311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S.D.; Beverly, R.L.; Qu, Y.; Dallas, D.C. Milk Bioactive Peptide Database: A Comprehensive Database of Milk Protein-Derived Bioactive Peptides and Novel Visualization. Food Chem. 2017, 232, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, S.D.-H.; Liang, N.; Rathish, H.; Kim, B.J.; Lueangsakulthai, J.; Koh, J.; Qu, Y.; Schulz, H.-J.; Dallas, D.C. Bioactive Milk Peptides: An Updated Comprehensive Overview and Database. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 11510–11529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavares, T.; del Mar Contreras, M.; Amorim, M.; Pintado, M.; Recio, I.; Malcata, F.X. Novel Whey-Derived Pep-tides with Inhibitory Effect against Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme: In Vitro Effect and Stability to Gastrointes-tinal Enzymes. Peptides 2011, 32, 1013–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajterer, C.; Shani Levi, C.; Lesmes, U. An In Vitro Digestion Model Accounting for Sex Differences in Gastrointestinal Functions and Its Application to Study Differential Protein Digestibility. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 132, 107850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, H.; Nakato, J.; Mizushige, T.; Iwakura, H.; Sato, M.; Suzuki, H.; Kanamoto, R.; Ohinata, K. Lacto-Ghrestatin, a Novel Bovine Milk-Derived Peptide, Suppresses Ghrelin Secretion. FEBS Lett. 2017, 591, 2121–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrochano, A.R.; Arranz, E.; De Noni, I.; Stuknytė, M.; Ferraretto, A.; Kelly, P.M.; Buckin, V.; Giblin, L. Intestinal Health Benefits of Bovine Whey Proteins after Simulated Gastrointestinal Digestion. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 49, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodkorb, A.; Egger, L.; Alminger, M.; Alvito, P.; Assunção, R.; Ballance, S.; Bohn, T.; Bourlieu-Lacanal, C.; Boutrou, R.; Carrière, F.; et al. INFOGEST Static In Vitro Simulation of Gastrointestinal Food Digestion. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 991–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradford, M.M. A Rapid and Sensitive Method for the Quantitation of Microgram Quantities of Protein Utilizing the Principle of Protein–Dye Binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najdi Hejazi, S.; Orsat, V.; Azadi, B.; Kubow, S. Improvement of the In Vitro Protein Digestibility of Amaranth Grain through Optimization of the Malting Process. J. Cereal Sci. 2016, 68, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serena-Romero, G.; Ignot-Gutiérrez, A.; Conde-Rivas, O.; Lima-Silva, M.I.; Martínez, A.J.; Guajardo-Flores, D.; Cruz-Huerta, E. Impacto de la Digestión In Vitro en la Digestibilidad, Liberación de Aminoácidos y Actividad Antioxidante de las Proteínas de Amaranto (Amaranthus cruentus L.) y Cañihua (Chenopodium pallidicaule Aellen) en Células Caco-2 y HepG2. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çevikkalp, S.A.; Löker, G.B.; Yaman, M.; Amoutzopoulos, B. A Simplified HPLC Method for Determination of Tryptophan in Some Cereals and Legumes. Food Chem. 2016, 193, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grønning, A.G.B.; Kacprowski, T.; Schéele, C. MultiPep: A Hierarchical Deep Learning Approach for Multi-Label Classification of Peptide Bioactivities. Biol. Methods Protoc. 2021, 6, bpab021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conover, W.J.; Iman, R.L. Rank Transformations as a Bridge between Parametric and Nonparametric Statistics. Am. Stat. 1981, 35, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Amino Acid Sequence | Protein | Residue Range | Reported Bioactivity | Molecular Mass (Da) | Isoelectric Point (pI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FHTSGYDTQA | α–La | 30–40 | DPP–IV Inhibitor | 1125.4712 | 4.98 |

| CKDDQNPH | α–La | 61–68 | Antibacterial | 955.3806 | 5.14 |

| DKVGINY | α–La | 97–103 | ACE inhibitor | 807.4114 | 6.69 |

| DKVGINYW | α–La | 97–104 | ACE inhibitor | 993.4905 | 6.70 |

| LAHKA | α–La | 105–110 | ACE inhibitor | 538.3219 | 10.14 |

| LCSEKLDQ | α–La | 110–117 | DPP–IV Inhibitor | 934.4415 | 4.00 |

| LIVTQTMK | β–Lg | 1–8 | Immunomodulator | 932.5348 | 10.14 |

| VLDTDY | β–Lg | 94–99 | ACE inhibitor | 724.3268 | 2.88 |

| TPEVDDEALEK | β–Lg | 125–135 | DPP–IV Inhibitor | 1244.5752 | 3.43 |

| LSFNPTQ | β–Lg | 149–155 | ACE inhibitor | 805.3958 | 5.44 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ignot-Gutiérrez, A.; Arellano-Castillo, O.; Serena-Romero, G.; Alvarado-Olivarez, M.; Guajardo-Flores, D.; Martínez, A.J.; Cruz-Huerta, E. Release of Bioactive Peptides from Whey Protein During In Vitro Digestion and Their Effect on CCK Secretion in Enteroendocrine Cells: An In Silico and In Vitro Approach. Molecules 2026, 31, 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020238

Ignot-Gutiérrez A, Arellano-Castillo O, Serena-Romero G, Alvarado-Olivarez M, Guajardo-Flores D, Martínez AJ, Cruz-Huerta E. Release of Bioactive Peptides from Whey Protein During In Vitro Digestion and Their Effect on CCK Secretion in Enteroendocrine Cells: An In Silico and In Vitro Approach. Molecules. 2026; 31(2):238. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020238

Chicago/Turabian StyleIgnot-Gutiérrez, Anaís, Orlando Arellano-Castillo, Gloricel Serena-Romero, Mayvi Alvarado-Olivarez, Daniel Guajardo-Flores, Armando J. Martínez, and Elvia Cruz-Huerta. 2026. "Release of Bioactive Peptides from Whey Protein During In Vitro Digestion and Their Effect on CCK Secretion in Enteroendocrine Cells: An In Silico and In Vitro Approach" Molecules 31, no. 2: 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020238

APA StyleIgnot-Gutiérrez, A., Arellano-Castillo, O., Serena-Romero, G., Alvarado-Olivarez, M., Guajardo-Flores, D., Martínez, A. J., & Cruz-Huerta, E. (2026). Release of Bioactive Peptides from Whey Protein During In Vitro Digestion and Their Effect on CCK Secretion in Enteroendocrine Cells: An In Silico and In Vitro Approach. Molecules, 31(2), 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020238