Abstract

Plastic streams dominated by polyethylene (PE) including PE HD/MD (High Density/Medium Density) and PE LD/LLD (Low Density/Linear Low Density), polypropylene (PP), and polyvinyl chloride (PVC) across Europe demand a design framework that links synthesis with end of life reactivity, supporting circular economic goals and European Union waste management targets. This work integrates polymerization derived chain architecture and depolymerization mechanisms to guide selective valorization of commercial plastic wastes in the European context. Catalytic topologies such as Bronsted or Lewis acidity, framework aluminum siting, micro and mesoporosity, initiators, and strategies for process termination are evaluated under relevant variables including temperature, heating rate, vapor residence time, and pressure as encountered in industrial practice throughout Europe. The analysis demonstrates that polymer chain architecture constrains reaction pathways and attainable product profiles, while additives, catalyst residues, and contaminants in real waste streams can shift radical populations and observed selectivity under otherwise similar operating windows. For example, strong Bronsted acidity and shape selective micropores favor the formation of C2 to C4 olefins and Benzene, Toluene, and Xylene (BTX) aromatics, while weaker acidity and hierarchical porosity help preserve chain length, resulting in paraffinic oils and waxes. Increasing mesopore content shortens contact times and limits undesired secondary cracking. The use of suitable initiators lowers the energy threshold and broadens processing options, whereas diffusion management and surface passivation help reduce catalyst deactivation. In the case of PVC, continuous hydrogen chloride removal and the use of basic or redox co catalysts or ionic liquids reduce the dehydrochlorination temperature and improve fraction purity. Staged dechlorination followed by subsequent residue cracking is essential to obtain high quality output and prevent the release of harmful by products within European Union approved processes. Framing process design as a sequence that connects chain architecture, degradation chemistry, and operating windows supports mechanistically informed selection of catalysts, severity, and residence time, while recognizing that reported selectivity varies strongly with reactor configuration and feed heterogeneity and that focused comparative studies are required to validate quantitative structure to selectivity links. In European post consumer sorting chains, PS and PC are frequently handled as separate fractions or appear in residues with distinct processing routes, therefore they are not included in the polymer set analyzed here. Polystyrene and polycarbonate are outside the scope of this review because they are commonly handled as separate fractions and are typically optimized toward different product slates than the gas, oil, and wax focused pathways emphasized here.

1. Introduction

Diverting plastic waste away from landfills is no longer just a matter of space and leachate control; it is an opportunity to recover carbon as useful energy carriers and chemicals via thermal and catalytic valorization [1,2,3]. In this manuscript, the term polyolefins is used in the chemical sense for olefin derived polymers, including PE, PP, and PVC. For clarity in process design, PE and PP are often discussed together, whereas PVC is discussed in dedicated parts because chlorine driven dehydrochlorination introduces distinct constraints on reactor operation, corrosion, and product purification. Across these polymers, chain architecture formed during polymerization provides a baseline for radical formation and scission statistics after melting, while processing history, ageing, additives, impurities, and operating conditions can widen and shift the observed kinetics and product distributions [1,2,3,4,5]. The aim of this review is to provide a defensible process design bridge for PE including PE HD MD and PE LD LLD, PP, and PVC by linking polymerization derived chain architecture to dominant thermolysis pathways, and by showing how operating variables and intervention layers (catalysts, initiators, and halogen management) shift the product window between gas, oil, wax, and aromatics. Because post consumer feeds differ in additive packages, catalyst residues, and contamination levels, the structure and selectivity discussed in this review are interpreted as mechanistic tendencies within reported operating windows, not as universal quantitative correlations. In this review, structure selectivity links are stated only as directional trends within stated operating windows, and Tables 2 and 3 report the minimum basis conditions (reactor mode, temperature program, heating rate, vapor residence time, atmosphere or pressure, and for catalysts the catalyst to polymer ratio and contact mode) required for a defensible comparison.

This review focuses on the dominant olefin derived polymer streams relevant for thermal recycling of European post consumer plastics, specifically PE including PE LD and PE LLD, PE HD and PE MD, PP. Polystyrene (PS) and polycarbonate (PC) are not treated in detail in this work because their pyrolysis pathways and target products differ from the oil and wax oriented product windows emphasized here, and because they are typically managed as separate fractions in practical sorting and processing routes. LLDPE is addressed within the PE LD family because its short chain branching architecture and packaging relevance place it within the same mechanistic and process design envelope for pyrolysis severity and product distribution. Strategic catalytic interventions—hydrogenolysis, metathesis, and acid site mediated cracking on micro/mesoporous frameworks—translate that mechanistic control into targeted product slates while minimizing waste formation [1,2,3].

For HDPE, LDPE and PP, well resolved kinetic and mechanistic studies converge on random C–C scission, β-scission, hydrogen abstraction, and backbiting as the primary routes that set the baseline gas vs. condensable yields [6,7]. Process severity and heat-flux history strongly modulate light olefin formation; under high heating rates, pressure and heating rate redistribute diene/alkene/alkane balances, while parametric datasets with advanced analytics clarify how temperature and residence time steer primary volatiles without prolonged cracking [8,9]. Mixed virgin and waste PP and PE LD/LLD systems exhibit lowered apparent barriers, enabling comparable conversions at milder temperatures—an operational advantage for waste streams [10]. Once acids are introduced, shape selectivity compresses distributions toward gasoline/BTX cuts over Hydrogen—form Zeolite Socony Mobil-5 (HZSM-5), whereas weaker acidity and larger pores, coupled with rapid quenching, preserve longer chains conducive to wax/oil fractions [11]. PP’s tertiary centers accentuate formation of C1–C4 and gasoline range intermediates at moderate severities; temperature programmed profiles delineate the window to pivot between off gas for combined heat and power (CHP) and liquids for upgrading [12].

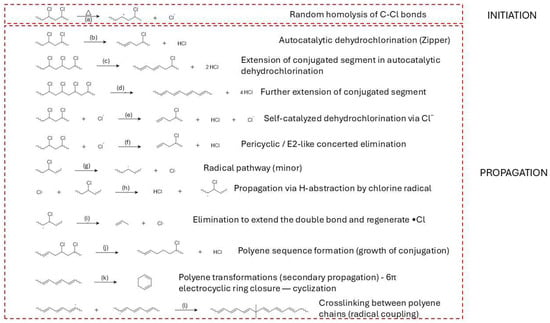

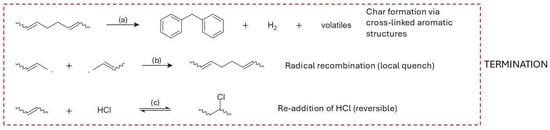

PVC requires a sequenced flowsheet. The first stage is controlled dehydrochlorination, governed by zipper type autocatalysis captured by classical kinetics and supported by evidence for parallel unimolecular and radical pathways; a modern two step kinetic picture aligns with these fundamentals and explicitly links the structure of the dehydrochlorinated residue to subsequent reactivity [13,14,15]. Selectivity improves when HCl is continuously removed. Additives and processing strategies that curtail HCl activity slow the autocatalytic loop and redirect pathways [16]. Metal chlorides/oxides lower the onset temperature for dehydrochlorination and can suppress aromatization from polyenes, enabling cleaner gases and residues for downstream conversion [17,18]. When aromatics form, they arise via intramolecular cyclizations of conjugated sequences—a mechanistic insight that justifies short residence and the use of mild basic/redox cocatalysts downstream to limit condensation [19]. Halogen–metal interactions matter operationally: Cu-based species markedly perturb HCl/volatile organic compound (VOC) release profiles, underscoring the need for halogen guards and compatible metallurgy [20]. At the molecular scale, defect-assisted chlorine migration and Thermogravimetric—Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (TG-FTIR) diagnostics on cable grades reinforce an analytics led two stage design (dechlorination → residue cracking) and help place capture media and catalysts effectively [21,22].

Catalyst microstructure, especially the balance of Brønsted and Lewis acidity, framework Al siting, and pore architecture, strongly influences how polymer derived intermediates traverse these degradation networks under a given temperature and residence time regime. Hierarchical ZSM-5 families and tuned acidity/alkalinity increase light olefin and aromatic yields while suppressing coke by mitigating secondary hydrogen transfer and cyclization in tight micropores [23,24,25]. Micropore topology dictates where coke nucleates and grows, linking void geometry to deactivation kinetics and selectivity loss [26]. Precise placement of framework Al can tilt pathways toward primary β-scission over secondary oligomerization, boosting olefin formation from LDPE/PP feeds [27].

Mechanistically, acidity aware molecular kinetic models and first-principles microkinetics illuminate when monomolecular cracking, bimolecular hydride transfer, or aromatization dominate, and how temperature or acid site density toggles among these regimes [28,29]. Zeolite confined β-scission barriers depend jointly on hydrocarbon structure and pore confinement, providing predictive handles to match feed microstructure (branching, unsaturation) with catalyst topology [30].

Operational levers couple with microstructure to steer outcomes. CO2 cofeeds promote dehydrogenation and shift equilibria toward aromatics over mesoporous HZSM-5 and Ga/ZSM-5, reducing coproduced H2 [31]. In PP/PE upgrading, mesopore enrichment shortens contact times and curbs secondary reactions, raising propylene/olefin selectivity without deep cracking [32]. Phase aware residence time control and staged/co feed strategies modulate pool chemistry, enabling concurrent formation of ethylene/propylene and para-xylene on a single catalyst bed when architecture and conditions are cooptimized [33,34].

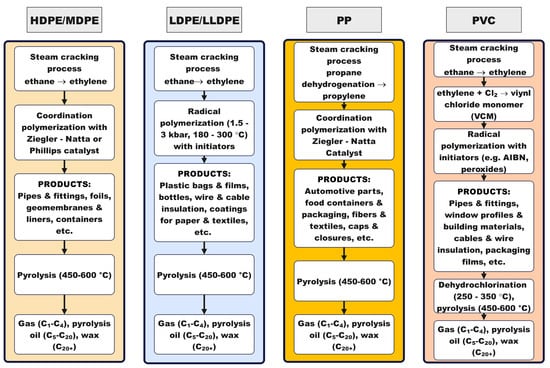

Stability hinges on diffusion management and acid site tailoring. Micropore-diffusion control and hierarchical/core–shell architectures delay pore mouth blockage and lower coke yield; phosphorus modification or external surface passivation further balances acidity to sustain activity at high conversion [25,35,36]. Pairing mesoporous domains in bifunctional systems limits methane and other light gas losses during hydrogenolysis/hydrocracking, extending time on stream while biasing liquids over gases [37]. Recent demonstrations with H-form MFI-type zeolite (HMFI) catalysts show that PP can be converted to light olefins even below classical pyrolytic temperatures when carbocation chemistry and external surface sites are leveraged, broadening the operable window for selective, energylean upgrading [38]. Figure 1 synthesizes this structure, mechanism and operation logic: starting from monomer supply and polymerization mode (Ziegler–Natta or radical) that largely defines chain architecture of PE HD/MD, PE LD/LLD, PP, and PVC, it maps the dominant thermolysis routes (random/β-scission, H-abstraction/backbiting; zipper dehydrochlorination for PVC), the key operating levers (temperature, heating rate, residence time, rapid quench), and the role of optional catalysts/initiators and HCl management (for PVC) in steering outcomes from light gases to paraffinic oils/waxes.

Figure 1.

Overview of the pathway from raw materials to pyrolysis for PE HD/MD, PE LD/LLD, PP, and PVC. Monomer supply (ethylene, propylene, VCM) and polymerization mode (coordination or radical) set the chain microstructures (branching, tertiary C, C–Cl) that influences baseline radical formation and scission tendencies after melting. At the end of life, fractions unsuitable for mechanical recycling are routed to pyrolysis. Dominant degradation modes are random/β-scission (HDPE), random scission with H-abstraction/backbiting (LDPE), β-scission (PP), and zipper dehydrochlorination to HCl and a polyene residue (PVC). Operating variables (temperature, heating rate, residence time, rapid quench) and optional catalysts/initiators (e.g., zeolites, metals, peroxides) tune product windows from gases to oils/waxes; for PVC, staged dechlorination with HCl capture precedes cracking of the residue.

A mechanistic viewpoint converts “non mechanistic operating window selection” into design: it identifies which bonds break first, which intermediates dominate, and where to intervene with catalysts (acid strength, metal function, topology), initiators (to set onset and radical populations), and suppressors/rapid quench (to limit secondary cracking and preserve chain length). That same insight maps operating envelopes, such as heating rate ramps and final temperatures, that bias gases toward cogeneration rather than paraffinic waxes/oils suitable for candles and heat storage materials (e.g., paraffins)—Phase Change Materials (PCMs)—turning landfilled liabilities into controllable product slates with defensible process conditions.

2. Polymerization—Derived Microstructure of HDPE, LDPE, PP, and PVC

In this review, “microstructure” is used in the molecular sense (chain architecture), i.e., branching (SCB/LCB), stereoregularity/tacticity, defect motifs (e.g., tertiary C sites, labile chlorides, head-to-head units), and molecular weight distribution. We refer to semicrystalline morphology (crystallinity, lamellae, amorphous/crystalline domains) separately as “morphology”, because it depends not only on polymerization but also on processing and thermal history (cooling rate, ageing, etc.). Since PE/PP pyrolysis occurs after melting, morphology is not treated as a primary mechanistic control variable in the molten degradation regime; the focus in Section 2 is the chain architecture that remains present in the melt and governs radical formation and scission statistics.

For clarity, polyethylene is treated using HDPE and LDPE as bounding chain architectures, while LLDPE is discussed within the PE LD family for packaging relevant waste streams.

Industrial production routes differ across the polymer set treated in this review. HDPE and PP are manufactured predominantly by coordination polymerization using Ziegler Natta and metallocene catalyst systems, which is why Section 2.1 focuses on coordination insertion control of chain architecture. LDPE is treated through high pressure free radical polymerization and PVC through radical routes used in industrial practice, which is why Section 2.2 is written in a radical polymerization context. Other polymerization modes exist for some monomers, including ionic routes, but they are not required for the specific PE HD/MD, PE LD/LLD, PP, and PVC scope of this review or for the structure to degradation argument developed later.

2.1. Coordination Polymerization Mechanism of HDPE/MPDE and PP

Coordination polymerization initiates by forming an active metal-alkyl complex at a Group IV transition metal site, typically involving titanium or zirconium as the central metal. This species is generated in situ by reacting a stable precatalyst with an alkylaluminum co-catalyst, such as triethylaluminum and methylaluminoxane (e.g., Et3Al, MAO), which simultaneously alkylates the metal and removes ligands, creating a vacant coordination site. This vacancy allows the olefin to bind via π-complexation, where electron donation and back-donation between the monomer and the metal stabilize the complex [39,40,41]. In titanium-based systems, this interaction facilitates 1,2-insertion of the monomer into the metal–carbon bond, forming the first covalent link in the polymer chain and converting the site into an active center for propagation. Initially, Ti(IV) alkyl cations were proposed as the active species, but recent studies show that Ti(III) alkyls, formed by partial reduction with the co-catalyst, often dominate. These Ti(III) species are more effective due to their unpaired electron, which enhances monomer coordination and insertion [39]. In copolymerizations (e.g., ethylene–propylene), each monomer follows the same insertion pathway, though differences in reactivity lead to a mix of random and block segments [42]. Activation energies for initiation are moderate, ranging from 33 to 67 kJ mol−1, depending on the catalyst type. Homogeneous systems generally show lower barriers, supporting efficient initiation under mild conditions, though high co catalyst concentrations may still promote side reactions [43,44,45,46].

In the coordination polymerization of HDPE, chain propagation proceeds via repeated insertion of ethylene monomers into a growing metal–carbon bond at an active center such as Ti–C or Zr–C. This occurs through a classical migratory insertion mechanism, which begins with π-complexation of ethylene to a vacant site on the transition metal, followed by insertion into the metal–alkyl bond [46]. In Ziegler–Natta systems, propagation is highly stereoselective, leading to linear HDPE with low branching. Metallocene catalysts, such as zirconocene complexes, allow more precise control over polymer architecture [47]. Computational studies show that while the first few insertions face slightly increasing energy barriers due to steric hindrance and agostic interactions, these barriers later decrease, stabilizing the propagation process [48].

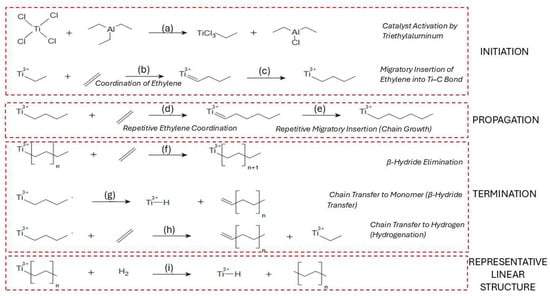

The coordination of ethylene to the active site involves π-complexation, wherein the ethylene molecule donates electron density to the empty d-orbitals of the titanium center, forming a non-covalent π-complex [39,49]. This coordination orients the monomer for the subsequent insertion step but does not yet form a covalent bond. This step, along with the preceding catalyst activation, is illustrated in Figure 2a,b.

Figure 2.

Proposed reaction mechanism for the coordination polymerization of ethylene to HDPE using a TiCl4/Al(C2H5)3 Ziegler–Natta catalytic system. (a) Activation of the TiCl4 catalyst by triethylaluminum, forming an active titanium–ethyl species, (b) π-coordination of ethylene to the Ti3+ center, (c) migratory insertion of ethylene into the Ti–C bond, extending the chain by two carbon atoms, (d) coordination of another ethylene molecule to the titanium center, (e) repeated migratory insertions of ethylene during chain propagation, (f) chain termination by β-hydride elimination forming a terminal double bond, (g) chain transfer to monomer via β-hydride transfer, producing a saturated chain and regenerating a Ti–ethyl site, (h) chain transfer to hydrogen (hydrogenation), terminating the chain with a fully saturated alkyl end, and (i) formation of the final linear HDPE chain structure, which is highly crystalline due to minimal branching.

The migratory insertion of the coordinated ethylene into the Ti–C bond marks the beginning of chain growth, also known as chain initiation (Figure 2c) [50]. This step results in the formation of a new Ti–CH2–CH2–R species, where R denotes the rest of the growing polymer chain. Once the first insertion has occurred, the catalyst–polymer complex is fully activated for propagation [51]. Propagation in the coordination polymerization of HDPE involves the repeated migratory insertion of ethylene monomers into the growing metal–carbon bond, as shown in Figure 2d [52]. Each propagation step requires a fresh coordination of ethylene, followed by insertion into the Ti–C bond at the active site, typically a titanium–alkyl species. This process is highly stereoselective and normally yields linear polyethylene with minimal branching when Ziegler–Natta or metallocene catalysts are used [39,53].

Chain termination occurs through several competing mechanisms, the most common being β-hydride elimination (BHE), β-hydride transfer to monomer (BHT), and hydrogenolysis (chain transfer to hydrogen). In β-hydride elimination, a β-hydrogen from the growing polymer chain is transferred to the metal, resulting in the formation of a vinyl-terminated polymer and a metal–hydride species (Figure 2e). This pathway becomes more dominant at low monomer concentration and is generally less energetically favored than BHT [54]. β-Hydride transfer to the monomer, shown in Figure 2f, involves transferring a β-hydrogen to a nearby ethylene molecule rather than to the metal center, producing a saturated chain end and regenerating the active site. This route is often preferred due to its lower activation energy and ability to maintain polymerization activity, especially under ethylene-rich conditions [55,56]. Finally, chain transfer to hydrogen, or hydrogenation, involves hydrogenolysis of the metal–carbon bond (Figure 2g). This process leads to saturated alkyl-terminated chains and is commonly used industrially to control molecular weight distribution. It is highly selective and depends on hydrogen concentration and the catalyst’s structure [57,58]. Finally, chain transfer to hydrogen, or hydrogenation, involves hydrogenolysis of the metal–carbon bond (Figure 2h). This process leads to saturated alkyl-terminated chains and is commonly used industrially to control molecular weight distribution. It is highly selective and depends on both hydrogen concentration and the catalyst’s structure [58]. The resulting linear polyethylene structure with minimal branching is represented in Figure 2i.

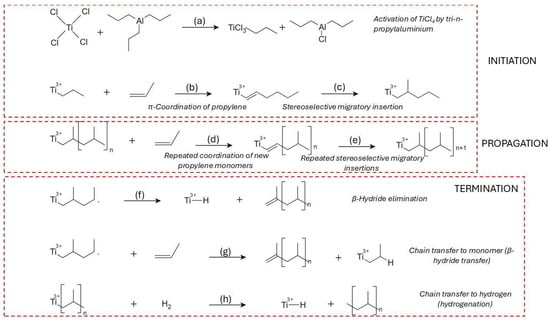

In the coordination polymerization of PP, the process initiates with catalyst activation identical to HDPE, involving the formation of a Ti(III)–ethyl complex on MgCl2 after alkylation by AlEt3 (Figure 3a) [59]. Propylene coordinates to the active site via its C=C double bond, forming a π-complex with a specific facial orientation, governed by the stereoelectronic environment of the metal center (Figure 3b). This orientation dictates the regio- and stereochemistry of insertion, which occurs via migratory insertion of the CH2 group into the Ti–C bond (Figure 3c) [60]. The resulting growing chain maintains a defined stereoregularity—either isotactic, syndiotactic, or atactic—depending on the symmetry and ligand design of the catalyst system [61]. Electron donors, both internal (e.g., diisobutyl phthalate) and external (e.g., silane-based modifiers), fine-tune this environment by altering the electron density at the titanium center and the π-complex coordination geometry [62,63].

Figure 3.

Reaction mechanism pathway of the synthesis of PP using the Ziegler-Natta catalyst TiCl4. (a) The catalyst activation or reduction of Ti(IV) to Ti(III) and alkylization of the transition metal center, and formation of the Ti3+-ethyl complex; (b) monomer coordination or π complex formation; (c) migratory insertion or chain initiation; (d) chain propagation (repeated migratory insertions); (e) chain termination—β hydride elimination; (f) chain termination—β-hydride transfer to monomer (g) chain termination—hydrogenation or chain transfer to hydrogen; (h) chain transfer to hydrogen (hydrogenation).

The propagation of PP chains continues via successive insertions, each guided by steric and electronic effects that enforce specific tacticity. C2-symmetric zirconocene catalysts are known to promote high isotacticity through chiral induction and enantiomorphic site control [64]. Kinetic studies have shown that the first propylene insertion is stereodetermining, while subsequent insertions propagate the same configuration unless interrupted by chain transfer or site deactivation (Figure 3d,e) [65]. Metallocenes and advanced Ziegler–Natta catalysts can achieve turnover frequencies ranging from 0.1 to 1 monomer per active site per second under optimized conditions [66].

Termination mechanisms in PP polymerization are more diverse due to the additional methyl group on the monomer, which permits β-methyl elimination in addition to β-hydride elimination. In β-methyl elimination, the methyl group is removed from the β-position and transferred to the metal center, forming allylic or branched end-groups [67]. β-Hydride elimination, the more common route, leads to vinyl-terminated PP chains and Ti–H species (Figure 3f), whereas β-hydride transfer to monomer results in a new Ti–alkyl center and a terminally unsaturated chain (Figure 3g) [68,69]. Octahedral zirconium complexes with carefully tuned ligand geometries demonstrate comparable precision: while one catalyst may yield site-controlled isotactic chains, a structurally similar complex may produce syndiotactic polymers under chain-end control, emphasizing the sensitivity of stereochemical outcome to ligand design [70]. The migratory insertion mechanism becomes essential in specific catalyst systems, particularly those based on C2-symmetric s-bis(indenyl) {SBI}-type zirconocenes. These catalysts direct monomer coordination to the sterically crowded site, favoring chain migration and high isotacticity. Thermochemical modeling of the first few insertion steps correlates well with experimental pentad distributions, confirming that migratory insertion mechanisms dominate in these systems and are necessary for achieving highly isoselective propagation [71].

Chain transfer to hydrogen is especially significant industrially, where molecular hydrogen is used to produce PP with reduced molecular weight and improved processability (Figure 3h) [57,58]. This pathway involves the cleavage of the metal–carbon bond by hydrogen, forming a saturated polymer and a new Ti–H center, which can reinitiate polymerization or become deactivated depending on the system [72].

Computational studies have further refined these mechanistic pathways, revealing two dominant transition states in β-hydride transfer: Syn Transition State (TSA), which favors direct metal–hydrogen bonding and is common in less sterically hindered environments, and Anti Transition State (TSC), more prominent in bulkier catalysts where propagation is sterically hindered and termination is favored [56,73]. Subtle changes in ligand geometry, donor type, and monomer concentration govern the selection between these routes. These findings demonstrate the crucial role of catalyst design and polymerization environment in determining the final properties of PP.

Overall, coordination polymerization of HDPE and PP follows a fundamentally similar mechanism driven by metal-catalyzed coordination–insertion, but their differences in monomer structure led to distinct stereochemical pathways, termination behavior, and catalyst requirements. The design of catalyst ligands, use of electron donors, and operational parameters such as hydrogen pressure and monomer concentration together allow precise control of polymer microstructure, molecular weight distribution, and end-group functionality. These parameters must be finely tuned to meet specific industrial requirements, particularly for the sustainable and efficient synthesis of HDPE, LDPE and PP under modern green chemistry constraints.

2.2. Free Radical Polymerization of LDPE and PVC

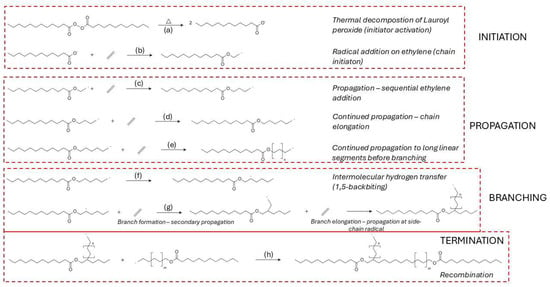

The synthesis of LDPE via high-pressure free radical polymerization is initiated by the thermal decomposition of organic peroxides, which generate reactive radicals capable of initiating chain growth [74,75,76,77]. The efficiency of this initiation step is highly dependent on the peroxide’s molecular structure, decomposition kinetics, and compatibility with process parameters such as temperature, pressure, and residence time [75,78]. Among the commonly used initiators, lauroyl peroxide is frequently applied due to its predictable decomposition behavior [79]. The decomposition pathway of lauroyl peroxide is illustrated in Figure 4a, where homolytic O–O bond cleavage leads to the formation of two acyloxy radicals [79]. These radicals subsequently react with ethylene monomers to form the first macroradical species, as shown in Figure 4b [80].

Figure 4.

Proposed free radical polymerization mechanism for the formation of LDPE using lauroyl peroxide as initiator. (a) Decomposition of lauroyl peroxide yields two primary radicals, (b) radical addition to ethylene initiates chain growth, (c) propagation by sequential ethylene additions, (d) continued linear propagation via repetitive monomer insertions, (e) extended chain growth under high-pressure conditions, (f) intramolecular hydrogen transfer (1,5-backbiting) forms a secondary internal radical, (g) branch formation via ethylene addition at the side-chain radical site, with branch elongation through continued propagation from the newly formed branch point, and (h) termination by recombination of two radical chain ends.

Initiator structure plays a pivotal role in defining polymerization performance [81]. For instance, bi-functional peroxides produce multiple radical centres upon decomposition, enabling more rapid initiation and increased monomer conversion relative to their mono-functional counterparts [82]. This enhanced efficiency is crucial for maintaining high yields and narrow molecular weight distributions, especially under the extreme conditions characteristic of LDPE production [83]. Meanwhile, tetrafunctional initiators like JWEB50 have been shown to outperform conventional mono-functional initiators in other monomer systems, underscoring the broader utility of multifunctional peroxides in radical polymerizations [84].

The decomposition of organic peroxides typically proceeds via homolytic O–O bond cleavage, producing acyloxy, alkyl, or alkoxy radicals depending on the peroxide type [85]. These radicals differ in reactivity and thermal stability, attributes that can be fine-tuned through steric and electronic modifications to the initiator structure [86]. For example, dialkyl peroxides yield fast initiation with reduced side reactions, while hydroperoxides and ketone peroxides, though reactive, pose safety concerns and are limited to niche applications [76].

Initiator performance evolves with changes in process conditions [87]. Each peroxide displays an optimal temperature range where radical generation is maximized and undesired side reactions are minimized [88]. Beyond this range, excessive decomposition reduces radical efficiency, diminishing polymer yield despite higher initiator consumption [89]. The introduction of composite initiation strategies—such as combining azo and peroxide initiators—has been explored to balance radical reactivity and propagation control, especially in systems where fine-tuning molecular architecture is desirable [76,85,90].

Overall, initiation in LDPE polymerization hinges on precise radical generation via carefully selected peroxides [76,85,90]. By optimizing initiator structure, dosing, and thermal behavior in response to reactor conditions, industrial processes can achieve efficient chain initiation with minimal waste and maximum product control [91].

Propagation in the free radical polymerization of LDPE proceeds through the sequential addition of ethylene monomers to growing chain radicals, a process governed by a delicate balance between chain growth, intermolecular chain transfer, and intramolecular branching [92,93,94]. This propagation sequence is shown in Figure 4c–e [92]. One of the dominant branching mechanisms is 1,5-hydrogen backbiting, where a hydrogen atom is abstracted from a methylene unit five carbon atoms upstream, producing a secondary or tertiary radical that enables the formation of short-chain branches—an essential structural feature of LDPE [92]. This reaction is shown in Figure 4f, where the terminal radical folds back and abstracts a hydrogen atom from an internal CH2 group, generating a branched radical that can further propagate (Figure 4g) [79,89,94]. This pathway has a relatively low activation energy, 54 kJ mol−1, making it kinetically favorable under high-pressure industrial conditions [95].

The competing intermolecular chain transfer reactions—particularly those involving hydrogen abstraction by solvent, monomer, or polymer—exhibit higher activation energies (~100 kJ mol−1) and primarily regulate molecular weight [96,97]. All three kinetic processes—propagation, chain transfer, and branching—scale quadratically with ethylene fugacity, reinforcing the role of pressure [98]. Kinetic models have been developed that explicitly account for primary propagation and secondary branching mechanisms [99,100]. These simulate molecular weight and branching distributions by solving recursion equations under realistic reactor conditions [101].

Termination occurs predominantly through bimolecular reactions between macroradicals, with recombination (combination) and disproportionation as the main pathways [96]. These are exemplified in Figure 4h, where two growing macroradicals undergo recombination to form a saturated polymer chain [102]. Chain-length-dependent termination (CLDT) has been confirmed using Pulsed Laser Polymerization (PLP) and Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) techniques, showing that short radicals terminate faster than longer ones [103,104]. Activation energy for termination is also chain-length dependent: short chains exhibit Ea of 25–39 kJ mol−1, while longer radicals show values of 18–24 kJ mol−1 [105]. The selectivity between termination modes is influenced by viscosity, radical size, and temperature. Higher temperatures and lower viscosities favor disproportionation, while viscous media promote recombination [102].

Termination dynamics are modelled using MWD-based simulations and Monte Carlo approaches that account for diffusion, backbiting, and gel effects [91]. Advanced techniques such as Single Pulse-Pulsed Laser Polymerization-Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (SP-PLP-EPR) quantify propagation and backbiting effects with high resolution [106,107].

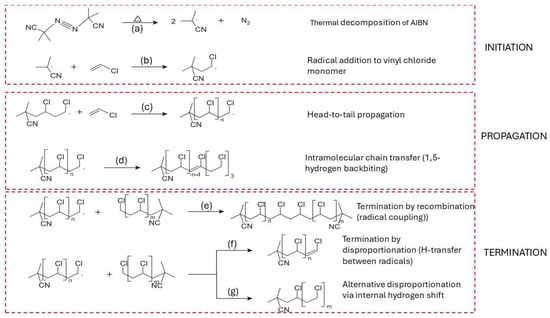

The free radical polymerization of vinyl chloride (VC) is initiated by the thermal decomposition of azo compounds such as azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN), which cleaves into two carbon-centered radicals [85,92,102]. This decomposition step is depicted in Figure 5a. The generated radicals add to vinyl chloride monomers, resulting in the formation of primary macroradicals as shown in Figure 5b [108]. Chain propagation proceeds predominantly through head-to-tail monomer addition, forming a linear and stereoregular structure, illustrated in Figure 5c [109]. The propagation step is highly exothermic, with activation energies at 24.9 kJ mol−1, depending on the tacticity and chain environment [110,111].

Figure 5.

Proposed mechanism of free radical polymerization of vinyl chloride (VC) using AIBN as initiator. (a) Thermal decomposition of AIBN generates two 2-cyano-2-propyl radicals and nitrogen gas. (b) The primary radical adds to vinyl chloride, forming an initiating macroradical. (c) Propagation occurs via head-to-tail addition of successive vinyl chloride monomers, yielding a stereoregular –CH2–CHCl– polymer backbone. (d) Intramolecular chain transfer through 1,5-hydrogen backbiting forms a mid-chain radical, initiating branching. (e) Termination by recombination, where two macroradicals couple to form a saturated chain. (f) Termination by disproportionation via hydrogen atom transfer, producing one saturated and one unsaturated PVC chain. (g) An alternative disproportionation route, involving an internal hydrogen shift, yields a saturated polymer end-group.

Intramolecular chain transfer via 1,5-hydrogen backbiting becomes significant as conversion increases, with the activation energy estimated at around 54.3 kJ mol−1 [94,111]. This step is visualized in Figure 5d, where the growing terminal radical abstracts a hydrogen atom from a methylene group within the chain, forming a mid-chain radical (MCR) [112,113,114]. The rate constant for the first propagation step from the branching site (BP1) is several orders of magnitude lower than for terminal propagation, although subsequent propagation steps (BP2, BP3) recover near-terminal reactivity [111,113,115].

At high monomer concentrations, chain transfer to monomer occurs via hydrogen abstraction, creating a new initiating radical and terminating the existing chain [113,116]. Although slower than propagation, this process becomes significant at elevated conversions and influences both molecular weight and the distribution of internal unsaturations [116,117]. Chain transfer to polymer results in long-chain branching and higher polydispersity, especially under bulk polymerization conditions [116].

Internal double bonds are formed through β-chlorine elimination or long-range hydrogen transfer [117]. These unsaturations behave like chain-end groups and contribute to thermal and UV instability of the polymer [118]. Stereoselective backbiting is also known to introduce tacticity-related defects, particularly at lower conversions when radicals exhibit greater conformational flexibility [119].

As polymerization proceeds toward high conversion (>85%), monomer availability in the reaction phase decreases sharply, and radical propagation slows due to increasing viscosity and reduced chain mobility [109,120]. Under these conditions, propagation shifts toward monomolecular reactions, and structural defects such as branching and internal unsaturation increase [120]. Chloroallylic end groups, commonly associated with chain termination, decrease in frequency at these stages, indicating a shift in dominant termination mechanisms [120,121].

Figure 5e–g summarizes the principal radical termination pathways relevant for radical chain reactions in general and it is included here as a conceptual reference for later degradation discussions, not as a claim that polymerization termination and pyrolysis termination are identical. In recombination (Figure 5e) [122], two macroradicals couple to form a single, saturated polymer chain, thereby neutralizing radical activity. Disproportionation (Figure 5f) entails hydrogen transfer from one radical to another, resulting in a saturated and an unsaturated chain, while a variant shift mechanism (Figure 5g) [123] yields a saturated molecule through internal stabilization. The balance between recombination and disproportionation is regulated by factors such as radical chain length, temperature, and melt viscosity [123,124]. Typically, short-chain radicals, owing to their higher diffusion rates, favor disproportionation, whereas larger, more hindered radicals promote recombination [105].

CLDT has been confirmed through experiments using pulsed laser polymerization and EPR spectroscopy [105,123]. These findings are relevant for modeling termination kinetics and predicting molecular weight distributions in industrial PVC production [109].

Chain transfer appears to play a significant role in PVC polymerization, particularly under high conversion and bulk-phase conditions. The observed number of initiator-derived end groups per chain is often below 0.4, which indicates that a single radical may initiate several chains through sequential transfer reactions. This mechanism aligns with industrial observations of lower-than-expected molecular weights despite moderate initiator concentrations. Terminal unsaturations introduced by disproportionation are critical for stability, as they can act as reactive sites under thermal or UV stress [125].

Accurate modelling of PVC polymerization must consider conversion-dependent changes in phase composition, chain mobility, and radical diffusion [105,126]. Such models have incorporated chain transfer, backbiting, and termination kinetics using detailed mechanistic frameworks [105]. Advanced computational methods like Gaussian-3 (Møller–Plesset 2)—Radical (G3(MP2)-RAD) and Our-N-layer Integrated Orbital and Molecular mechanics (ONIOM) have also been applied to estimate propagation constants and structural defect pathways, with results in agreement with experimental observations [93,127]. These approaches reveal that defect formation is not random but governed by steric constraints, energetic preferences, and local radical dynamics [125].

Ultimately, the development of structure–property relationships in PVC depends on precise control of chain propagation, transfer, and termination processes. By adjusting processing conditions such as initiator concentration, temperature, and monomer feed rates, polymer microstructure and product performance can be tuned to meet specific application requirements.

2.3. Linking Polymerization-Derived Microstructure to Pyrolysis: Radical Chain Kinetics and Product Selectivity

This subsection serves as a transition between polymer synthesis and thermal degradation. This structure to reactivity bridge is developed for saturated chain polyolefins, and it is not extended here to aromatic backbone polymers such as PS or carbonate polymers such as PC. It explains how polymerization defined molecular microstructure (chain architecture) constrains radical formation, scission statistics, and chain-transfer/termination tendencies during pyrolysis, thereby affecting degradation kinetics and product selectivity. This structure—reactivity linkage does not imply mechanistic equivalence between polymerization and pyrolysis; it uses chain architecture as the connecting variable between synthesis and degradation. Commercial waste plastics have heterogeneous processing and service histories. Cooling rate, shear during melt processing, and thermal ageing can change oxidation level, additive state, and the density of weak links, which can shift apparent onset temperature and kinetics. In this review, polymerization derived chain architecture is treated as a baseline descriptor, while processing and ageing history is treated as an uncertainty layer that can widen the observed behavior around that baseline.

In this subsection, noncatalytic thermolysis is treated as the baseline degradation mechanism, while catalytic upgrading over zeolites and additive assisted routes such as Ca based dechlorination are treated as intervention layers that can shift selectivity beyond the baseline. Quantitative generalization is limited because reported yields depend strongly on reactor type, heating program, residence time, pressure, and additives. Solid-state crystallinity is sometimes reported for commercial grades as an accessible proxy correlated with linearity/branching, however, it depends on processing history and is not preserved once the polymer is molten. Coordination polymerization of ethylene with Ziegler–Natta or metallocene catalysts typically produces HDPE with short-chain branching (SCB) in the range of roughly <0.1–2 branches per 1000 carbon atoms and crystallinity around 60–80% [128,129,130]. High-pressure free radical polymerization yields LDPE with about 6–12 SCB/1000 C and a reduced crystallinity of ~30–50% [128]. Stereospecific coordination systems for PP generate isotactic grades with >90–99% meso pentad content and crystallinity of ~50–70%, in contrast to atactic PP with negligible crystallinity [131,132,133]. LLDPE is produced mainly by coordination copolymerization of ethylene with alpha olefin comonomers, which generates controlled short chain branching with minimal long chain branching, so it should be treated as a distinct packaging relevant polyethylene grade rather than merged into LDPE. In PVC, radical polymerization conditions and conversion history determine the fraction of labile structural defects (allylic and tertiary chlorides, head-to-head units, chain-end unsaturations), which may range from below 1% up to a few percent of repeat units and dominate the onset and rate of dehydrochlorination [134,135]. These relationships are summarized in Table 1, which compares polymerization method, branching level, tacticity, and molecular weight distribution for representative commercial PE-LD/LLD and PE-HD/MD, PP, and PVC grades.

Table 1.

Representative polymerization-derived microstructural parameters for major commodity polymers.

The selection of polymerization mechanism, catalyst system and operating conditions quantitatively fixes the accessible microstructural window and therefore constrains the pyrolysis product spectrum. In practice, catalyst identity (Ziegler–Natta vs. metallocene), use of hydrogen, initiator type and dose, reaction temperature and conversion can all be expressed as control variables that tune branching degree, tacticity, crystallinity, molecular weight distribution and defect content [50,130]. Table 2 organizes these relationships for representative coordination and radical systems, explicitly linking polymerization control knobs to microstructural descriptors and to the resulting changes in wax, olefin and dehydrochlorination behaviour. The selectivity shifts summarized in Table 2 are compiled from literature sources that use different reactor configurations and operating windows, and from materials with different additive packages. The table is intended to show directionality of structure and reactivity links under comparable mechanistic regimes, while absolute yields remain sensitive to process severity, residence time, and formulation specific additives or contaminants.

Table 2.

Polymerization control: detailed quantitative effects on chain architecture and associated trends in pyrolysis selectivity. ↑ indicates an increase in the corresponding parameter relative to the reference condition; ↓ indicates a decrease.

Table 2.

Polymerization control: detailed quantitative effects on chain architecture and associated trends in pyrolysis selectivity. ↑ indicates an increase in the corresponding parameter relative to the reference condition; ↓ indicates a decrease.

| Polymerization Control (Specific Agents/Conditions) | Chain Architecture Descriptor (Molecular) | Pyrolysis Conditions | Pyrolysis Product Selectivity | Rationale | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ziegler–Natta catalyst (TiCl4/AlR3), ↑ H2 cofeed (PE) | SCB ↓ (0.1 → 0.02/1000 C); linear sequence fraction ↑ (60 → 75%); Mw ↓ (by up to 50%) | Continuous conical spouted bed reactor: inert nitrogen atmosphere, heating rate 10 °C per min atmospheric pressure, reactor temperature 450 to 600 °C, polymer feed rate about 1 g per min, nitrogen spouting flow about 11 L per min, short vapor residence time | Wax yield +10–15%; olefin yield −10% | H2 acts as a chain transfer agent, shortening chains and increasing linearity and branching density; fewer branches and more linear segments favour paraffinic wax formation during pyrolysis. | [54,129,130,142] |

| Metallocene catalyst (e.g., Cp2ZrCl2/MAO, PP, PE) | Tacticity ↑ (meso pentad > 99% for PP); Mw/Mn ↓ (6 → 2); defects isolated | Fixed bed reactor: inert nitrogen environment, heating rate 10 °C per min, reactor temperature 500 to 600 °C, isothermal hold 30 min, effective pyrolysis duration about 5 to 10 min depending on temperature. | BTX (catalytic) yield +15–20%; higher wax fractions | Single site control produces highly uniform, stereoregular chains, enhancing the fraction of long, substituted segments that aromatize and survive as heavy waxes in pyrolysis. | [130,143] |

| Peroxide initiator (e.g., di tert-butyl peroxide, LDPE), ↑ concentration, T ↑ | SCB ↑ (6 → 12 /1000 C atoms); branch point density increases, including tertiary carbon sites | Fixed bed reactor: inert nitrogen environment, heating rate 10 °C per min, reactor temperature 500 to 600 °C, isothermal hold 30 min, no carrier gas flow during pyrolysis, effective reaction time about 5 to 10 min. | Light olefin yield +20%; wax yield −15% | Peroxide initiated radical polymerization generates more branching and amorphous content; branched sites undergo β-scission more readily, giving shorter C2–C4 olefins. | [144,145,146] |

| PVC via free radical route (e.g., AIBN), ↑ conversion/temperature | Labile defects ↑ (<1 → 5/1000; tertiary/allylic Cl, HTHT units) | Batch tube reactor: isothermal 530 °C, residence time 25 min, inert atmosphere, heating rate 15 °C per min | Dehydrochlorination T ↓ −30 °C; aromatics/char yield +10% | Higher conversion or temperature increases labile Cl—containing defects, lowering the barrier for HCl elimination and promoting backbone crosslinking and aromatization. | [21,134,135,147] |

Typical Ziegler–Natta polyethylene systems employ titanium tetrachloride (TiCl4) with a cocatalyst, AlR3 [54]. Additional hydrogen increases chain-transfer frequency, shortens chains and favours more linear, crystalline structures; such feeds degrade more slowly and accumulate as long-chain paraffinic waxes, while reduced branching suppresses short-olefin formation [129,130]. Metallocene catalysts such as Cp2ZrCl2 activated with MAO generate highly uniform chains; in PP, this produces very high isotactic indices (meso pentad > 99%), which in catalytic pyrolysis often translate into BTX yields above ~35 wt% over zeolites and into a larger fraction of heavy liquids [68,74].

Peroxide-initiated LDPE, produced under high pressure and temperature, responds strongly to initiator concentration and temperature [144,146]. Free radical PVC synthesis with initiators such as AIBN shows an analogous control lever: higher polymerization temperature or greater conversion increases the population of head-to-head linkages and tertiary or allylic chloride sites, which act as weak points. These defects enable HCl elimination at lower temperatures and leave conjugated backbones that readily crosslink and aromatize, increasing char and aromatic yields in thermal degradation [21,134,135,147]. Together, the relationships in Table 1 and Table 2 provide a quantitative bridge from polymerization operation (choice of catalyst and initiator, use of H2, temperature, and conversion) to microstructure, and on to the direction and magnitude of changes in wax, light olefin, BTX, and dehydrochlorination behaviour.

These microstructural parameters translate into measurable differences in pyrolysis product distributions under technologically relevant conditions. At moderate severities typical for plastic waste valorization (e.g., 450–600 °C, inert or vacuum atmosphere, short vapor residence times), linear HDPE grades with low SCB and high crystallinity generally produce a condensable oil/wax fraction on the order of 50–80 wt%, dominated by n-alkanes and α-olefins in the C10–C30 range, with the remainder as permanent gases [137,138,148]. Under comparable non-catalytic conditions, branched LDPE grades (≈6–12 SCB per 1000 C atoms) usually yield only ~35–45 wt% oils/waxes, while the fraction of light olefins (C2–C4) increases roughly into the 40–60 wt% range of total products [128,149]. Representative studies show that increasing SCB content from around 2 to around 8 branches per 1000 carbons can reduce wax/oil yields by about 10–15% and increase light olefin yields by roughly 15–20%, demonstrating that branching generated during radical polymerization is a first-order design variable for gas vs. liquid selectivity in polyethylene pyrolysis [148]. Under the same severity and residence time window, LLDPE is expected to show intermediate selectivity, compared with HDPE it shifts toward higher light olefin formation due to higher short chain branching, while compared with LDPE it preserves a larger oil and wax fraction because it lacks the highly branched long chain architecture typical for high pressure LDPE. These quantitative trends are summarized in Table 3, which lists typical ranges of onset temperature, apparent activation energy, and product yields (oil/wax, light olefins, and BTX) for PE HD/MD, PE LD/LLD, isotactic PP, and PVC under comparable pyrolysis conditions, with and without HZSM-5.

Table 3.

Representative pyrolysis performance ranges for HDPE, LDPE, isotactic PP, and PVC. Onset temperature and depend on TGA heating rate. Yield ranges refer to 450 to 600 °C under inert or vacuum atmosphere with short vapor residence times of about 0.5 to 5.6 s.

Table 3.

Representative pyrolysis performance ranges for HDPE, LDPE, isotactic PP, and PVC. Onset temperature and depend on TGA heating rate. Yield ranges refer to 450 to 600 °C under inert or vacuum atmosphere with short vapor residence times of about 0.5 to 5.6 s.

| Polymer | Pyrolysis Onset T (°C) | Ea (kJ mol−1) | Basis Conditions (Kinetics and Yields) | Oil/Wax Yield 450–600 °C (%) | Olefin Yield (%) | BTX Yield w/o HZSM-5 (%) | BTX Yield w/HSZM-5 | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HDPE | 400–440 | 222–270 | TGA under inert gas, heating rate 5 to 30 K min−1; reactor pyrolysis at 450 to 600 °C, inert or vacuum atmosphere, vapor residence time 1.4 to 5.6 s, catalyst polymer ratio (mass): 33:1 | 50–80 | 30–45 | <10 | 25–35 | [137,150,151] |

| LDPE/LLDPE | 410–475 | 190–240 | TGA under inert gas, heating rate 5 to 30 K min−1; reactor pyrolysis at 450 to 600 °C, inert or vacuum atmosphere, vapor residence time at or below 0.5 s for liquid rich operation, catalyst polymer ratio (mass): 10:1 | 35–45 | 45–60 | 10–20 | 30–40 | [128,138,149] |

| PP (isotactic) | 370–420 | 240–301 | TGA under inert gas, heating rate 5 to 30 K min−1; reactor pyrolysis at 450 to 600 °C, inert or vacuum atmosphere, vapor residence time 1.4 to 5.6 s, catalyst polymer ratio (mass): 80:1 | 40–60 | 35–50 | 15–20 | 35–53 | [132,152,153] |

| PVC | 270–320 (dehydrochlorination) | 131–199 | TGA under inert gas, heating rate 5 to 30 K min. Increasing heating rate from 5 to 30 K min−1 shifts the main decomposition peak from about 266 °C to 307 °C inert atmosphere. Product yields depend strongly on residence time and secondary reactions under the reactor conditions reported in the cited studies. Catalyst polymer ratio (CaO/Cl): 1:2 | 10–20 | <5 | <5 | <10 | [134,135] |

Solid state crystallinity is a morphology descriptor influenced by processing history. It is not used here as a primary mechanistic driver of molten phase pyrolysis. When mentioned elsewhere, it is treated only as a proxy correlated with chain architecture.

From a mechanistic viewpoint, this behavior is consistent with the scission statistics of linear versus branched segments. In molten polyethylene, long linear sequences (typical of HDPE grades with low SCB) tend to generate longer-lived secondary radicals and favor β-scission pathways that yield long-chain fragments and α-olefins, preserving heavier condensables at moderate severity. In contrast, higher SCB/LCB levels (typical of LDPE) increase the frequency of substituted radical sites and intramolecular backbiting, promoting shorter fragments and higher light-olefin yields. Because pyrolysis proceeds after melting, semicrystalline morphology is not treated as a primary mechanistic control variable in this regime. Transport effects are more appropriately discussed via melt viscosity and diffusion, which depend mainly on molecular weight and branching [151,154]. During pyrolysis, Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) monitoring show that linear segments are cleaved more rapidly than densely branched regions, with a characteristic decrease in maximum segment length from on the order of 100 carbon atoms to below ~50 carbon atoms early in the degradation, while branch-rich regions show higher tendencies for crosslinking and char formation [128]. This difference in local reactivity explains why LDPE produces higher proportions of light olefins and branched hydrocarbons at the expense of heavy waxes under identical thermal histories.

Differences in apparent onset temperatures and activation energies reported across commercial PE/PP grades are often discussed alongside solid-state crystallinity; however, crystallinity depends on both chain architecture and processing history and is not preserved once the polymer is molten [132,133]. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) shows that HDPE grades with high crystallinity exhibit sharp melting peaks around 130 °C and higher melting enthalpies, while LDPE shows broader melting ranges (≈70–110 °C) and lower enthalpies, reflecting microstructural heterogeneity [128]. Apparent activation energies and onset temperatures reported by TGA vary across commercial grades primarily because chain architecture and molecular weight distributions differ, including branching density, defect motifs, and dispersity. Under comparable thermal programs, more linear and higher molecular weight feeds tend to preserve longer fragments at moderate severity, while more highly branched architectures more readily generate shorter olefins and lighter products [134]. Thus, polymerization control variables such as catalyst family, hydrogen use, comonomer feed, temperature, and conversion are expressed quantitatively in terms of branching, defect content, and molecular weight distribution, which can then be linked to wax versus gas trends under specified pyrolysis conditions [136,149,155].

For PP, the density and spatial organization of tertiary carbons, fixed during stereoregular coordination polymerization, strongly promote β-scission and aromatization, especially under catalytic conditions [132]. Isotactic PP with high meso content generally displays higher thermal stability in non-catalytic pyrolysis, with mass-loss onset temperatures often reported around 400–420 °C, whereas atactic-rich grades with lower crystallinity may start to decompose around 350–380 °C [132]. Once degradation proceeds beyond the initial random scission phase, both isotactic and atactic PP produce liquids enriched in branched C5–C12 hydrocarbons and propylene oligomers, but isotactic grades with more extended crystallizable sequences tend to preserve more high-molecular-weight material at a given conversion [136,156]. When PP is processed over Brønsted-acidic zeolites such as HZSM-5 at ~650–750 °C with short vapor residence times, the high abundance of tertiary carbons and methyl-substituted backbone segments leads to elevated BTX yields: typical values reported are on the order of 35–50 wt% BTX in the liquid fraction, compared with roughly 20–30 wt% for HDPE under similar catalytic conditions [157].

Solid-state NMR and fractionation experiments show that isotactic PP sequences can partially isomerize toward more disordered configurations during heating, with a gradual decrease in isotactic pentad content and growth of mixed or syndiotactic sequences [132,133]. This loss of stereoregularity correlates with a decrease in crystallinity and an acceleration of mass loss at later stages of pyrolysis. Samples that start with higher isotacticity and narrower molecular-weight distributions (typical of metallocene catalysts) maintain their crystalline domains longer and show slower conversion to gases at a given temperature, biasing the product slate toward heavier liquids [133]. Thus, polymerization conditions that define isotacticity and molecular-weight dispersity serve as quantitative levers for controlling the distributions of BTX-rich, paraffinic, and gaseous products in PP pyrolysis.

In PVC, the link between polymerization defects and pyrolysis is particularly direct. Labile structural defects, introduced by radical initiation and propagation under non-ideal conditions (e.g., elevated temperature, high conversion, chain-transfer events), lower the activation energy for HCl elimination and shift the dehydrochlorination temperature window [135]. TGA measurements often show a two-stage mass-loss pattern: a first stage between roughly 270–380 °C dominated by HCl evolution and polyene formation, followed by a second stage at higher temperatures, where the conjugated backbone cracks to aromatics, gases and char. Samples with defect contents below about 1% typically begin releasing HCl at ≈300–320 °C, whereas materials with 3–5% labile defects can show onsets closer to 270–290 °C and higher total HCl evolution rates [134]. At a fixed thermal program, more defective PVC grades frequently yield higher fractions of aromatics and char, and slightly lower fractions of condensable aliphatic liquids, because early dehydrochlorination drives extensive backbone conjugation and crosslinking [158]. In practical terms, initiator selection, reaction temperature, chain-transfer control and conversion limits in PVC polymerization can be viewed as upstream parameters for setting the dehydrochlorination profile, HCl release rate and aromatic/char yield in downstream thermal treatment [159,160].

Process variables interact with this microstructural “baseline” but do not erase it at moderate severity. For HDPE and LDPE, increasing heating rate from slow values (e.g., 10–20 °C min−1) to swift values (e.g., flash pyrolysis conditions) generally increases the fraction of light olefins and suppresses secondary cracking of volatiles, yet linear HDPE still tends to produce more long-chain waxes than LDPE at the same temperature and residence time [161,162,163]. Similarly, short vapor residence times (≲0.5 s) favor liquid-rich product slates from LDPE at ~500 °C, whereas longer residence times (>1 s) or stronger acidic catalysts drive increased aromatization and gas formation; however, branched LDPE consistently yields more light olefins and aromatics than linear HDPE under matching conditions because its microstructure furnishes more substituted radical and carbocation intermediates [164,165].

Both vapor residence time and heating rate exert profound, quantifiable influences on product distribution, selectivity, and degradation pathways during polymer pyrolysis. Detailed micro-pyrolysis experiments have shown that for ordinary polyolefins such as HDPE, LDPE, PP and PVC, decreasing the vapor residence time from 5.6 s to 1.4 s at a reactor temperature of 600 °C shifts the product distribution significantly towards heavier waxes and liquid hydrocarbons in the C5–C20 range. In contrast, extending the vapor residence time strongly favors secondary cracking processes, resulting in a markedly higher yield of light gases and aromatic products [165,166]. For instance, under these conditions, gas yields from HDPE can rise from approximately 30 wt% at short residence times to as much as 80 wt% when the residence time is extended and the temperature is increased to 675 °C. Aromatic liquid yields also increase under more severe conditions, reaching values up to 15 wt%. These shifts in product spectrum due to residence time control are consistent with both laboratory and reactor-scale results, further demonstrating that tuning the residence time distribution in fluidized-bed reactors can shift selectivity by 25% or more toward desired products.

Recent studies show that varying the vapor residence time (typically in the range of 1.4–5.6 s) can significantly alter the product distribution, with shorter residence times favoring heavier waxes, while extended residence times lead to more gaseous and aromatic products [165]. This is especially true at higher temperatures (550–675 °C), where longer residence times promote extensive cracking. These findings are in line with reactor scale experiments where manipulating residence time distribution caused shifts of 10–25% in target product yields.

The heating rate is equally decisive in controlling degradation behavior and the evolution of product slats. At low heating rates, around 5 K min−1, the onset and maximum of mass loss are observed at lower temperatures, supporting gradual volatilization and enhanced formation of char and solid residue. As the heating rate increases to values such as 30 K min−1, the maximum rate of pyrolytic decomposition is shifted to higher temperatures (e.g., PVC’s Tmax increases from 539 K to 580 K under these conditions), facilitating more intense gas formation, rapid release of small-molecule volatiles (such as HCl from PVC), and substantially greater yields of light olefins and aromatics [167]. For polyolefins, heating rates up to 1000 °C s−1, as achieved in flash or micropyrolysis, can lead to near-complete primary conversion within just a few seconds. Fast heating compresses the pyrolysis interval, maximizes light product recovery, and minimizes secondary reactions [165].

Studies, such as those published in [167], demonstrate that increasing the heating rate (from 5 K min−1 to 30 K min−1 or even up to 1000 °C s−1) reduces the pyrolysis time, enhances the production of gaseous and light olefin products, and decreases the overall formation of heavier hydrocarbons and waxes. Such rapid heating is particularly beneficial for maximizing the recovery of lighter components and minimizing secondary cracking [168].

From a modeling perspective, these trends can be captured by kinetic schemes in which rate constants depend explicitly on microstructural descriptors. Random scission models for HDPE can use a single effective scission probability that reproduces the observed chain-length distribution and C1–C5 gas composition, whereas LDPE models require distinct rate constants for scission at linear segments versus branch-rich segments and sometimes incorporate parallel crosslinking reactions [169]. In PP, kinetic models that weight β-scission and aromatization pathways by tertiary-carbon fraction and degree of substitution reproduce the higher BTX yields observed for isotactic PP relative to polyethylene under catalytic conditions [170]. For PVC, two-step kinetic schemes with defect-controlled dehydrochlorination followed by polyene cracking account for the strong sensitivity of onset temperature and HCl release rate to small changes in defect content [134].

Polymerization conditions set the microstructure which biases wax oil, light olefin, gas and catalytic BTX tendencies under stated operating windows, while absolute yields remain sensitive to reactor severity, residence time and formulation. In practice, linear HDPE is wax-oriented; branched LDPE favors light olefins; stereoregular PP is BTX-oriented over acidic catalysts; and PVC with engineered defect content demands staged dehydrochlorination with basic sorbents.

Therefore, chain architecture provides a baseline framework for interpreting selectivity trends, while processing history and ageing can widen observed product distributions and shift apparent onset temperature even under similar operating conditions.

Commercial waste plastics are formulated materials and may contain antioxidants and stabilizers, fillers and pigments, plasticizers in PVC, residual catalyst species, and external contaminants. These components can scavenge radicals or promote radical generation, modify acid or redox microenvironments, and change the apparent onset and product distribution under the same nominal reactor temperature. Therefore, the chain architecture discussion in this subsection is treated as a mechanistic baseline, while additive and impurity effects are treated as an overlay that can shift the magnitude and sometimes the direction of selectivity trends

3. Mechanistic Pathways and Kinetic Characteristics of Thermal Degradation in HDPE, LDPE, PP and PVC

The following mechanistic descriptions treat chain architecture as the primary substrate level control, while recognising that additives, catalyst residues, and contaminants in waste derived feeds can overlay these pathways by shifting radical chemistry and apparent kinetics.

3.1. HDPE

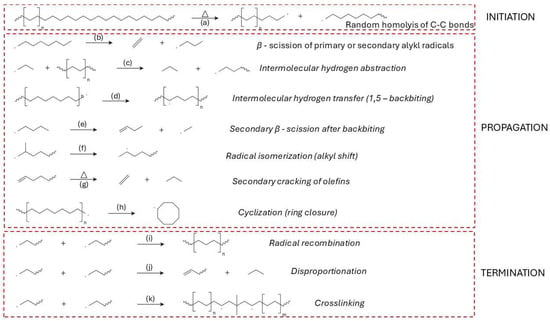

The initiation of thermal degradation in HDPE proceeds via homolytic cleavage of carbon–carbon (C–C) bonds, triggered when the system temperature exceeds the bond dissociation energy threshold. This process results in the formation of primary alkyl radicals that mark the onset of degradation, initiating radical chain reactions across the polymer backbone [80,81,82].

Early degradation events are predominantly described by a random scission model, wherein each C–C bond along the linear polymer chain has an equal probability of breaking under thermal stress (Figure 6a). This statistical approach successfully captures observed kinetic behavior and molecular weight distributions during pyrolysis, particularly in the absence of branching or catalytic residues [80,82,83]. However, site-specific initiation mechanisms have also been proposed, emphasizing preferential scission at structurally weaker sites—such as allylic positions or residual catalyst centres—where degradation may commence at lower temperatures [84].

Figure 6.

Thermal degradation mechanism of HDPE: (a) initiation by random C–C bond homolysis; (b) β-scission of primary/secondary alkyl radicals; (c) intermolecular hydrogen abstraction; (d) intramolecular hydrogen transfer (1,5-backbiting); (e) secondary β-scission following backbiting; (f) radical isomerization via alkyl shift; (g) secondary cracking of olefins; (h) cyclization into cyclic radicals; (i) radical recombination forming saturated chains; (j) disproportionation yielding unsaturated end groups; (k) crosslinking via radical coupling between chains.

Homolytic scission events generate highly reactive radicals that participate in subsequent reactions, such as hydrogen abstraction (Figure 6c), vinyl formation, and β-scission (Figure 6b). These radicals create vinyl and vinylidene end groups, with vinyl groups forming at rates significantly higher than the evolution of ethylene in early degradation stages, suggesting that functional group generation dominates over monomer recovery in the initiation phase [86].

Experimental studies have shown that the initiation step is highly sensitive to molecular weight, crystallinity, and thermal history. In waste derived feeds, prior melt processing and thermal ageing can introduce oxidized sites and additional weak links, which can shift the apparent onset temperature and kinetics. Lower molecular weight fractions degrade more readily due to enhanced chain mobility and reduced thermal stability, while crystalline regions offer greater resistance to bond rupture [81,86,171]. The onset temperature for random scission typically ranges between 400 and 440 °C, although the presence of impurities, chain defects, or catalytic residues can lower this threshold by as much as 100 °C [151].

Kinetic modelling of the initiation phase supports a homolytic mechanism with reported activation energies for HDPE degradation ranging from approximately 222 kJ mol−1 to 270 kJ mol−1, depending on the method used (e.g., Kissinger or Ozawa-Flynn-Wall and Vyazovkin isoconversional method) and the polymer architecture [151]. These values reflect the energy requirement for C–C bond cleavage and provide a quantitative foundation for process optimization in thermal recycling.

Although the random scission model remains widely accepted, recent work has highlighted the importance of distinguishing between uniformly random (chain reaction) and structurally biased (attack on β-positioned carbon) initiation. These distinctions are particularly relevant for refining pyrolysis models and improving the accuracy of product yield predictions in both open and closed systems [7,81].

Ultimately, the initiation of HDPE thermal degradation is best described as a complex interplay between random homolytic bond scission and site-specific activation, both of which are governed by temperature gradient rate and final temperature. Understanding this initiation step is essential for controlling downstream reaction pathways and optimizing the pyrolytic conversion of HDPE into valuable hydrocarbon fractions.

The propagation phase of HDPE thermal degradation is governed by a complex network of free radical-driven reactions that proceed following the initial homolytic cleavage of C–C bonds. At the beginning (at lower temperatures), the primary mechanism is random scission; as temperatures rise and the concentration of β-carbon positions increases, β-scission becomes the dominant mechanism (Figure 6b). Hypothesis can be supported by the formation of alkene products at higher temperatures of pyrolysis [172].Intermolecular hydrogen abstraction (Figure 6c) is another key step, where radicals extract hydrogen atoms from neighbouring polymer chains or smaller hydrocarbon molecules, thereby generating new radical sites and further driving the degradation process [86,172]. Intramolecular hydrogen transfer (Figure 6d), commonly referred to as backbiting, plays a critical role in creating secondary radical sites that undergo secondary β-scission (Figure 6e), contributing to the diversity of volatile products [171,173].

Radical isomerization, including alkyl shifts, promotes the rearrangement of radical intermediates to more stable configurations (Figure 6f), thereby altering the final product distribution [172,174]. Secondary cracking of olefins, especially under elevated temperatures and prolonged vapor residence times, further reduces long-chain olefins into lighter hydrocarbons (Figure 6g) [151,175].

Cyclization reactions can occur during degradation, where radicals undergo ring closure to form cyclic hydrocarbons (Figure 6h). These cyclic intermediates can subsequently undergo dehydrogenation and further rearrangements, eventually leading to the formation of aromatics and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), especially at temperatures above 600 °C [151,172,174,175].

Vinylidene formation is another important reaction pathway, leading to the development of vinyl-type structures through radical-induced elimination reactions, contributing to the unsaturation of the degradation products [151,172]. Minor radical β-scission and recombination equilibria also play a role in controlling the balance between chain fragmentation and radical stability, particularly at elevated temperatures (Figure 6i) [172,176].

Radical-induced disproportionation further contributes to the diversity of degradation products (Figure 6j) by forming stable radicals and smaller hydrocarbons [110]. Additionally, aromatization and PAH formation pathways are significant under severe pyrolytic conditions, as cyclic radicals undergo dehydrogenation and ring rearrangement to form stable aromatic structures [151].

Ring-opening reactions of cyclic hydrocarbons contribute to the formation of linear chain products, further enhancing the diversity of volatile products [151,171]. Dehydrogenation processes, especially at elevated temperatures, increase the unsaturation level in the resulting hydrocarbons and promote the formation of aromatic compounds [171,175,177].

Experimental studies confirm that the progression of propagation reactions and the final product distribution are highly dependent on the thermal environment and residence time. Low temperatures and short vapor residence times favour a broader spectrum of alkanes, alkenes, and waxes, while higher temperatures and longer residence times predominantly yield light hydrocarbons, monoaromatics, and PAHs [172,174].

Oxidative pathways, although not the focus of the propagation phase under inert pyrolysis conditions, may become significant in processing environments such as extrusion, where oxygen exposure leads to the formation of oxidized volatiles, such as aldehydes and carboxylic acids [178]. Additives, including flame retardants and catalytic residues, can also modulate the degradation pathway by accelerating or redirecting radical reactions toward desired product distributions or char formation [179,180].

Overall, the propagation phase in HDPE thermal degradation involves a dynamic interplay of β-scission, hydrogen abstraction, backbiting, isomerization, secondary cracking, cyclization, vinylidene formation, and dehydrogenation reactions. These mechanisms collectively dictate the evolution of product species and govern the molecular weight reduction, unsaturation levels, and aromatic content in the final pyrolysis products.

For HDPE, shown in Figure 6i–k, the termination processes outlined in Figure 5 are strongly influenced by crystallinity and branching [181,182]. Under vacuum and in the absence of oxygen, recombination of macroradicals is favored due to high melt viscosity, contributing to the retention of molecular weight and wax formation [169]. Disproportionation is supported by the formation of vinyl and vinylidene groups observed in product analysis, particularly in branched or low-mobility regions [181,183]. HDPE’s limited unsaturation restricts crosslinking, but the process can be promoted by residual catalyst fragments or increased branching [184]. The balance of these mechanisms dictates the yield of long-chain paraffins, olefins, and the potential for network formation under varying thermal conditions [185].

3.2. LDPE

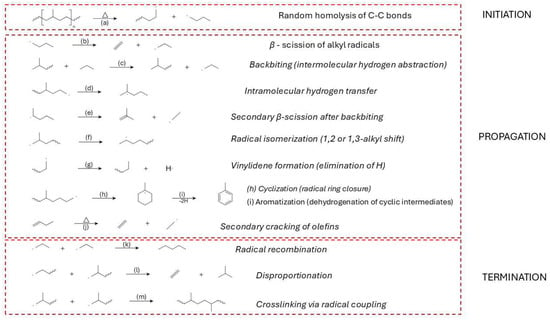

The thermal degradation of LDPE under vacuum initiates through random homolytic scission of C–C bonds along the polymer backbone (Figure 7a). This unimolecular process occurs without oxidative interference and becomes significant at elevated temperatures between 410 and 475 °C, where thermal energy exceeds the bond dissociation threshold of saturated carbon chains [186]. The alkyl radicals generated in this initiation step serve as the starting point for subsequent β-scission and hydrogen abstraction reactions.

Figure 7.

Thermal degradation mechanism of LDPE: (a) random C–C bond scission (homolysis); (b) β-scission of alkyl radicals; (c) backbiting (intermolecular hydrogen abstraction); (d) intramolecular hydrogen transfer; (e) secondary β-scission after backbiting; (f) radical isomerization (1,2 or 1,3-alkyl shift); (g) vinylidene formation (H elimination); (h) cyclization (ring closure); (i) aromatization (dehydrogenation of cyclic intermediates); (j) secondary cracking of olefins; (k) radical recombination; (l) disproportionation; (m) crosslinking via radical coupling.

Although often modelled as purely random, the cleavage of C–C bonds in LDPE is not uniformly statistical. Thermochemical studies and experimental analyses suggest a preference for scission at structurally weaker sites, such as allylic positions or tertiary carbons, due to their lower dissociation energies [7,81,187]. These preferential sites enable radical formation at lower activation energies and contribute to the early evolution of unsaturated species such as vinyl and vinylidene groups [188].

Upon C–C bond cleavage, primary and secondary alkyl radicals are formed. The stability of these radicals influences their reactivity, with secondary radicals generally being more thermodynamically favored and more likely to propagate the degradation process [186]. The radicals can also undergo stabilization through resonance delocalization or hydrogen abstraction from neighboring chains, forming longer-lived radical intermediates capable of driving further decomposition [189].

The initiation phase also leads to significant structural changes within the polymer matrix. These include the formation of double bonds and unsaturated end-groups, an increase in reactive chain ends, and the production of low molecular weight aliphatic fragments such as alkanes and alkenes [190]. These effects are consistent with both experimental measurements and kinetic simulations, which have reported early-stage molecular weight reduction and volatile product evolution as primary indicators of radical initiation [191].