Abstract

Haloketoesters are synthetic intermediates in various cyclization reactions that facilitate the production of biologically active compounds. Nonetheless, the selective synthesis of dihaloketoesters and trihaloketoesters, which are expected to be highly versatile, presents significant challenges. In this study, we designed a new synthetic approach that selectively and efficiently produces haloketoesters through the halogenative C–C bond cleavage and ring-opening reactions of cyclic 1,3-diketones. This convenient method enables the direct synthesis of di- and trichloro-functionalized ketoesters from 1,3-cyclohexadiones under mild conditions. Na2HPO4, employed as a buffer salt, proved to be effective in facilitating the alcoholytic ring-opening reaction of 2,2-dichloro-1,3-cyclohexadiones, which were generated as synthetic intermediates.

1. Introduction

Acyclic keto acids and ketoesters are amenable to a range of cyclization reactions, resulting in diverse ring structures including disubstituted lactams [1,2,3,4], acyllactams [5], disubstituted cyclic amines [6,7], monosubstituted lactones [8,9,10,11], gem-disubstituted lactones [12,13], monosubstituted enol lactones [14], acyllactones [15,16], other heterocycles [17,18], and carbocyclic compounds [19]. These acyclic molecules can be synthesized through various strategies such as the retro-Claisen reaction [20,21,22,23], Michael reaction [24,25,26], directed oxidation reaction [27], oxidative ring-opening reaction [28,29,30,31], cross-coupling reaction [32,33], and insertion reaction [34]. These methodologies facilitate the introduction of diverse substituents and enable a variety of synthetic approaches from the appropriate starting materials.

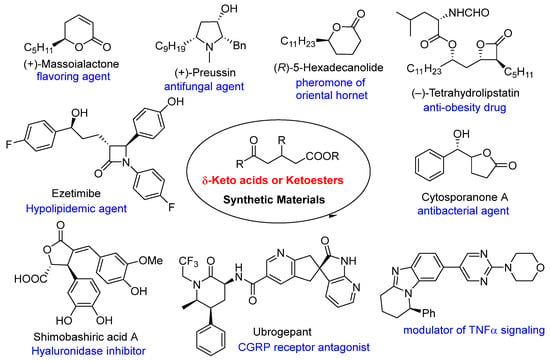

Keto acids and ketoesters are recognized for their inclusion in various bioactive compounds, such as duazomycin (N-acetyl DON) [35], esonarimod (KE-298) [36], (R)-flobufen [37], kynurenine [38], tanomastat (BAY 12-9566) [39], and 3F-5-AL [40], rendering them significant synthetic targets. Furthermore, keto acids and ketoesters serve as excellent synthetic building blocks, possessing at least two reactive sites with distinct chemical properties. Indeed, numerous synthetic methodologies have been developed utilizing these compounds as key molecules for the synthesis of bioactive compounds, including cytosporanone A, massoialactone, preussin, hexadecanolide, tetrahydrolipstatin, ezetimibe, shimobashiric acid A, ubrogepant, and several unnamed substances (Figure 1) [1,15,41,42,43,44,45].

Figure 1.

Bioactive compounds synthesized using δ-keto acids and ketoesters as intermediates.

In particular, functionalized haloketoesters are highly versatile in their derivatization. Dihaloacyl groups are applicable to asymmetric reduction [46,47,48], aldol reactions [49,50,51,52], Z-alkenoate formation [53,54,55], [4+3] cycloaddition [53,55], and various heterocycle formations [53,56,57,58,59]. Furthermore, trihaloacyl groups have been employed in asymmetric Mannich-type reactions [60,61,62], asymmetric reduction followed by Jocic-type reactions [63], radical addition reactions [64], and Grignard reactions [65]. Trihaloacyl groups also serve as leaving groups during alcoholysis [66] and aminolysis [67]. Our previous research demonstrated that haloketoesters, which possess both a haloacyl moiety and an ester moiety, provide additional versatility in derivatizations [68,69,70].

However, the selective synthesis of di- and trihaloketoesters via ketoester halogenation presents significant challenges. This difficulty arises because the introduction of halogen atoms at the ketone α-position competes with halogenation at the alternative α’-position. Additionally, overreactions such as trihalogenation (e.g., haloform reactions) complicate the synthesis of dihalogenated compounds, rendering it exceedingly difficult to control both the regioselectivity and the number of halogen atoms introduced.

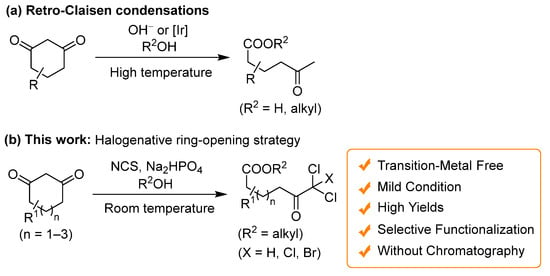

This study focuses on selective halogenation via ring-opening reactions of cyclic 1,3-diketones, which are readily synthesized using various methodologies [71,72,73,74,75,76,77]. Traditional approaches to reagent-controlled ring-opening reactions employ strong bases, as well as metal-catalyst-controlled retro-Claisen condensations [20], albeit requiring elevated temperatures. These methods facilitate the formation of non-functionalized ring-opening products from cyclic 1,3-diketones (Scheme 1a). Integrating halogenation under harsh conditions is not conducive to the selective synthesis of haloketoesters. In this study, we successfully developed a direct and selective synthesis method for di- and trihaloketoesters from cyclic 1,3-diketones, eliminating the need for transition metals, through convenient halogenative ring-opening esterification under mild conditions (Scheme 1b). Notably, the synthesis of dichloroketo acids was accomplished without using chromatography. Our approach for synthesizing functionalized ketoesters has the potential to advance the molecular transformation of 1,3-cyclohexadiones into diverse heterocyclic compounds.

Scheme 1.

Ring-cleavage reactions of cyclic 1,3-diketones: (a) Retro-Claisen condensations; (b) This work: Halogenative ring-opening strategy.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Optimization of Buffer Salt for Halogenative Ring-Opening Reaction

The gem-dihalomethylketone moiety is a potent site for C–C bond cleavage. Initial halogenative C–C bond cleavage reactions of acyclic molecules are primarily of interest for their degradative fragmentation properties [78]. In recent years, however, synthetically valuable C–C bond cleavage reactions have been developed, including gem-difluorination [79,80], dichlorination [81,82,83,84,85], and dibromination [81,83], through the use of halogenating agents and nucleophiles. Analogous reactions have been implicated in the biosynthesis of biologically active compounds [86,87]. However, halogenative C–C bond cleavage reactions involving the ring opening of cyclic molecules have not been extensively explored for synthetic applications. Although such reactions have been conducted using alcohols [88,89,90], water [91], and amines [92,93,94] as nucleophiles, they are generally restricted to ring-strained substrates and often require harsh conditions such as high temperatures and strong bases. The dichloroacetylation of amines, employing cyclic gem-dichlorodiester as the sacrificial agent, utilizes a comparable C–C bond cleavage process [95].

Building upon the product analysis of multiple reactions observed during the monochlorodimedone assay [69], we previously demonstrated the stepwise cleavage of the C–C bond in a cyclic substrate devoid of ring strain [70]. Nevertheless, C–C bond cleavage accompanied by the dichlorination of cyclic diketones under one-pot conditions has not been demonstrated.

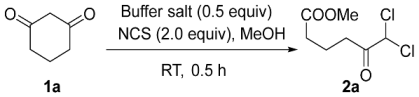

This study focuses on the direct synthesis of di- or trichloroketo acid methyl esters from cyclic 1,3-diketones under considerably mild conditions in an alcoholic medium containing N-chlorosuccinimide (NCS) and buffer salts at ambient temperature. Initially, the influence of buffer salts on the conversion of cyclohexadione 1a to dichloroketoester 2a in the presence of MeOH was assessed, and the results are presented in Table 1. The sodium salt exhibited a higher product yield than the potassium salt. Moreover, weakly basic salts such as Na2HPO4, NaHCO3, and AcONa (entries 1, 5, and 9, respectively) were determined to be more effective than NaH2PO4, a weakly acidic salt (entry 3), and Na2CO3, a relatively strong base (entry 7). Consequently, Na2HPO4 was identified as the optimal salt for the halogenative ring cleavage. When a catalytic amount of the base was used, the reaction was stopped after 30 min. Therefore, a minimum of 0.5 equivalents of Na2HPO4 was required for the reaction to proceed completely.

Table 1.

Effect of buffer salt on the halogenative ring-cleavage reaction.

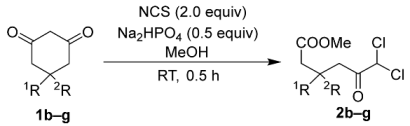

2.2. Substrate Scope

The substrate scope was evaluated under the optimized conditions using Na2HPO4 (Table 2). For the synthesis of 5-substituted dichloroketo acid methyl esters 2b–g from the corresponding 1,3-cyclohexadiones 1b–g, 2.0 equivalents of NCS were used in the presence of 0.5 equivalents of Na2HPO4. This direct synthesis yielded monosubstituted dichloroketoesters 2b–d and gem-disubstituted dichloroketoesters 2e–g with high efficiency (Table 2). The comparable yields of methyl-substituted products 2b,e and phenyl-substituted products 2c,f indicate that the 5-position of the corresponding substrates 1b,c,e,f was not significantly influenced by steric hindrance in this reaction. Furthermore, p-anisyl-substituted product 2d and p-tolyl-substituted product 2g demonstrated the potential to introduce additional substituents at the aryl moiety. However, this method is unsuitable for the synthesis of dibromoketoesters because the buffer salt induces debromination of the synthetic intermediate 2,2-dibromo-1,3-cyclohexadiones [69,96].

Table 2.

Substrate scope of the halogenative ring-cleavage reaction producing dichloroketoesters.

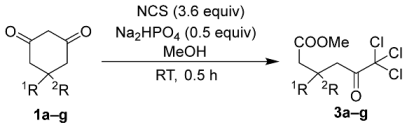

By contrast, the utilization of 3.6 equivalents of NCS facilitated the synthesis of trichloroketo acid methyl esters 3a–g. This reaction requires excess NCS beyond the stoichiometric quantities. When only 3.0 equivalents of NCS were employed, small amounts of the corresponding dichloroketoesters 2a–g persisted within the reaction system as synthetic intermediates, complicating the purification of the desired corresponding trichloroketoesters 3a–g. This approach successfully yielded trichloroketoesters without substituent 3, with monosubstituents 3b–d and gem-disubstituents 3e–g in high yields (Table 3). The yields of trichloroketoesters 3a–g were comparable to those of the corresponding dichloroketoesters 2a–g (see Table 2).

Table 3.

Halogenative ring-cleavage reaction producing trichloroketoesters 3a–g.

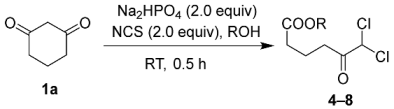

Additionally, alcohols that functioned as co-solvents were screened. The ester moiety of the product in this reaction depends on the alcohol used. For the synthesis of dichloroketo acid alkyl ester, 2.0 equivalents of NCS and Na2HPO4 were used in a dehydrated alcohol with 3 Å molecular sieves, as detailed in Table 4. Ring-cleavage reactions with EtOH, nPrOH, and 2-methoxyethanol yielded the corresponding ethyl ester 4, n-propyl ester 5, and 2-methoxyethyl ester 6, respectively, with high efficiency (entries 1–3). Conversely, ring cleavage using nBuOH and iBuOH afforded the corresponding n-butyl ester 7 and i-butyl ester 8, respectively, in low yields (entries 4 and 5). As mentioned above, these esters are produced in the presence of primary alcohols. However, when the secondary alcohol iPrOH or the tertiary alcohol tBuOH was employed, the corresponding esters were not formed; instead, the reactions resulted in the formation of dichloroketo acids. This indicates that the steric hindrance of the alcohol side chain significantly influences the nucleophilic reaction of alcohols with gem-dichlorinated synthetic intermediates.

Table 4.

Synthesis of dichloroketo acid alkyl esters.

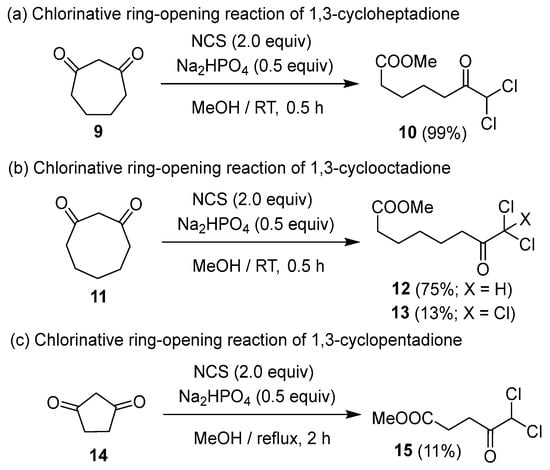

The dichlorinative ring cleavage of 1,3-cycloheptadione 9 afforded the corresponding product 10 in good yield, whereas 1,3-cyclooctadione 11 produced the corresponding dichloroketoester 12 along with trichloroketoester 13 as a byproduct (Scheme 2a,b). This implies that the chlorination of 1,3-cyclooctadione 11 is the rate-determining step of the dichlorinative ring-cleavage reaction. On the other hand, 1,3-cyclopentanone 14 did not undergo chlorination at ambient temperature; however, the corresponding dichloroketoester 15 was obtained in low yield under reflux conditions (Scheme 2c). The inability to synthesize 15 using Cs2CO3, a stronger base, indicates that Na2HPO4, a weaker base, is more suitable for this reaction.

Scheme 2.

Ring-size scope for halogenative ring cleavage, of (a) 1,3-cycloheptadione, (b) 1,3-cyclooctadione, and (c) 1,3-cyclopentadione.

2.3. Mechanism

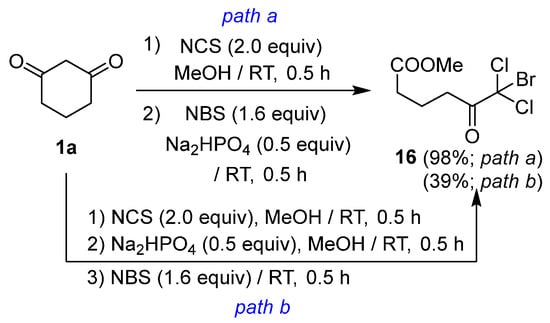

Mixed trihaloketoesters can be synthesized through a stepwise approach involving gem-chlorination of cyclic 1,3-diketones, followed by alcoholic ring cleavage of the resulting cyclic dichloro-1,3-diketones. For instance, dichloromonobromoketoester 16 was obtained in 98% yield via gem-chlorination of cyclic diketone 1a, followed by the addition of Na2HPO4 in the presence of NBS (Scheme 3, path a). However, the addition of NBS after the ring-cleavage reaction with Na2HPO4 resulted in a reduced yield of 39% (Scheme 3, path b). This observation indicates that the enolate generated immediately prior to the ring-cleavage reaction served as a highly reactive intermediate for the third subsequent halogenation.

Scheme 3.

Control experiment for trihalogenative ring-cleavage reactions.

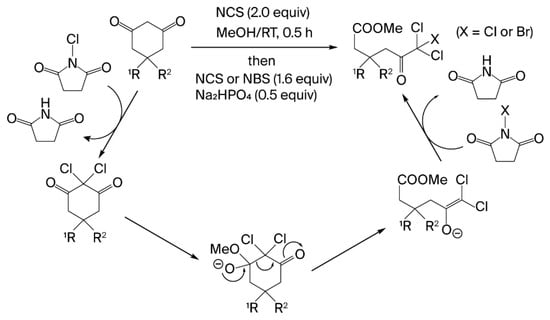

Halogenative ring cleavage of cyclic 1,3-diketones involves two independent processes: gem-dichlorination and alcoholic ring opening (Figure 2). In the gem-dichlorination process, the reaction proceeds quantitatively—even in the absence of Na2HPO4—because the succinimide anion generated from NCS during chlorination acts as a base. The carbonyl group of the cyclic 1,3-diketone, which completely suppresses enol–enol isomerization via gem-dichlorination, regains its electrophilicity, thereby facilitating nucleophilic reactions with alcohols. However, the alcohol ring-opening process requires Na2HPO4. The recarbonylation of the alkoxy anion generated by the nucleophilic reaction of alcohols drives the irreversible cleavage of the C–C bond, while the intramolecular gem-chloroacetyl moiety aids in charge stabilization. Consequently, an environment with excess halogenating agent for gem-dichlorination resulted in the formation of a trihaloketoester from the enol anion, whereas an environment lacking excess halogenating agent yielded a dihaloketoester, as the enol anion was readily protonated by the surrounding protic solvent. Although the reaction mechanism is similar to the classical Lieben haloform reaction, it differs in the number of required halogen atoms and the reaction selectivity for C–C bond cleavage. Our method requires dihalogenation for the cleavage of cyclic 1,3-diketones, whereas the haloform reaction typically requires trihalogenation for substrates containing an acetyl group. Another distinction is that the trihaloacetyl moiety in the trihaloketoesters is retained without further fragmentation in our method. This unique chemoselectivity is synthetically advantageous.

Figure 2.

Mechanism of halogenative ring-cleavage reaction producing trihaloketoester.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Information

5-(p-Methoxyphenyl)-1,3-cyclohexanedione 1d [97] was prepared from 4-(p-methoxyphenyl)-3-butene-2-one and diethyl malonate according to the literature. 5-Methyl-5-phenyl-1,3-cyclohexanedione 1f [98] and 5-methyl-5-p-tolyl-1,3-cyclohexanedione 1g were prepared from 5-methylresorcinol according to the literature. 1H and 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were recorded on an ECS 400 and ECX 500 NMR spectrometer (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) using deuterated chloroform (CDCl3) as the solvent. Chemical shifts (δ) are reported in ppm relative to tetramethylsilane (δ = 0) as an internal standard. The coupling constants (J) are reported in Hertz, and the multiplicity is reported according to the following convention: singlet (s), doublet (d), double doublet (dd), triplet (t), quintet (quin), sextet (sext), octet (o), broad singlet (br), and multiplet (m). The chemical shifts (number of protons, multiplicity, and coupling constants) are reported. Infrared (IR) spectra were recorded using a JASCO FT/IR-4200 spectrometer (JASCO, Tokyo, Japan) using the diffuse reflectance method with KBr powder. Absorption is expressed in units of reciprocal centimeters (cm−1). High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were obtained using the electron ionization (EI) method and recorded using a JMS-700 spectrometer (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

3.2. Synthesis of Haloketo Acid Alkyl Esters

3.2.1. General Procedure for Synthesizing Dichloroketo Acid Methyl Esters

To a solution of a 1,3-cyclohexadione (1.0 mmol) and NCS (267.1 mg, 2.0 mmol) in MeOH (10 mL), Na2HPO4 (71 mg, 0.5 mmol) was added. After stirring the mixture at room temperature for 0.5 h, the solvent was evaporated. The product was dissolved in CH2Cl2, and the extract was filtered through filter paper for dehydration. After evaporation to remove the solvent, the product was dissolved in hexane by sonication, and the extract was filtered through filter paper. The removal of the solvent by evaporation afforded the purified product.

3.2.2. 6,6-Dichloro-5-oxo-hexanoic Acid Methyl Ester (2a)

Colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 2.00 (2H, quin, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.40 (2H, t, J = 7.3 Hz), 2.92 (2H, t, J = 7.1 Hz), 3.69 (3H, s), 5.84 (1H, s) ppm. 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 18.9, 32.6, 33.9, 51.7, 69.7, 173.3, 196.7 ppm. IR (ATR, KBr): ν 3649, 3545, 3456, 2953, 2848, 2596, 2411, 2068, 1733, 1606, 1438, 1372, 1210, 1088, 1053, 892, 867, 782, 727 cm−1. HRMS (EI, m/z) calcd for C7H11Cl2O3 [M + 1]+: 213.0085; found: 213.0079.

3.2.3. 6,6-Dichloro-3-methyl-5-oxo-hexanoic Acid Methyl Ester (2b)

Colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.04 (3H, d, J = 6.9 Hz), 2.30 (1H, dd, J = 15.6, 7.3 Hz), 2.38 (1H, dd, J = 15.6, 6.4 Hz), 2.57 (1H, o, J = 6.9 Hz), 2.79 (1H, dd, J = 17.8, 7.3 Hz), 2.91 (1H, dd, J = 17.9, 6.2 Hz), 3.68 (3H, s), 5.82 (1H, s) ppm. 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 19.8, 26.2, 40.2, 41.1, 51.6, 70.0, 172.6, 195.9 ppm. IR (ATR, KBr): ν 3656, 3620, 3539, 3456, 2968, 2845, 2741, 2610, 2019, 1736, 1437, 1370, 1171, 1078, 1039, 1009, 957, 858, 784, 733, 663, 551 cm−1. HRMS (EI, m/z) calcd for C8H13Cl2O3 [M + 1]+: 227.0242; found: 227.0240.

3.2.4. 6,6-Dichloro-5-oxo-3-phenyl-hexanoic Acid Methyl Ester (2c)

Colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 2.68 (1H, dd, J = 15.6, 7.4 Hz), 2.74 (1H, dd, J = 16.0, 7.3 Hz), 3.23 (2H, d, J = 7.3 Hz), 3.61 (3H, s), 3.74 (1H, quin, J = 7.3 Hz), 5.71 (1H, s), 7.20–7.26 (3H, m), 7.28–7.34 (2H, m) ppm. 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 37.0, 40.1, 41.0, 51.7, 69.9, 127.2, 127.2, 128.7, 142.1, 172.0, 195.0 ppm. IR (ATR, KBr): ν 3063, 3030, 3005, 2952, 2845, 1954, 1878, 1735, 1604, 1496, 1455, 1438, 1368, 1336, 1265, 1221, 1161, 1127, 1081, 1028, 993, 889, 845, 793, 764, 733, 700, 562, 522 cm−1. HRMS (EI, m/z) calcd for C13H14Cl2O3 [M]+: 288.0320; found: 288.0323.

3.2.5. 6,6-Dichloro-3-(4-methoxy-phenyl)-5-oxo-hexanoic Acid Methyl Ester (2d)

Colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 2.64 (1H, dd, J = 15.1, 7.8 Hz), 2.70 (1H, dd, J = 16.0, 7.3 Hz), 3.18 (2H, d, J = 7.3 Hz), 3.60 (3H, s), 3.78 (3H, s), 5.70 (1H, s), 6.83 (2H, d, J = 8.7 Hz), 7.15 (2H, d, J = 8.7 Hz) ppm. 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 36.3, 40.3, 41.2, 51.7, 55.2, 69.9, 114.0, 128.3, 134.0, 158.5, 172.0, 195.0 ppm. IR (ATR, KBr): ν 3659, 3562, 3459, 3002, 2954, 2838, 2602, 2549, 2493, 2426, 2059, 1883, 1736, 1612, 1583, 1514, 1439, 1366, 1250, 1084, 1031, 830, 794, 743, 556, 539 cm−1. HRMS (EI, m/z) calcd for C14H16Cl2O4 [M]+: 318.0426; found: 318.0426.

3.2.6. 6,6-Dichloro-3,3-dimethyl-5-oxo-hexanoic Acid Methyl Ester (2e)

Colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.14 (6H, s), 2.50 (2H, s), 2.97 (2H, s), 3.65 (3H, s), 5.83 (1H, s) ppm. 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 28.1, 32.6, 44.0, 44.3, 51.3, 70.5, 172.4, 195.7 ppm. 1H and 13C NMR data are consistent with those reported in the literature [67].

3.2.7. 6,6-Dichloro-3-methyl-5-oxo-3-phenyl-hexanoic Acid Methyl Ester (2f)

Colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 2.88 (1H, d, J = 15.1 Hz), 2.98 (1H, d, J = 15.1 Hz), 3.43 (1H, d, J = 17.8 Hz), 3.50 (1H, d, J = 17.8 Hz), 3.58 (3H, s), 5.61 (1H, s), 7.20–7.25 (1H, m), 7.30–7.35 (4H, m) ppm. 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 26.1, 39.0, 44.5, 44.9, 51.5, 70.4, 125.2, 126.7, 128.5, 145.4, 171.9, 194.7 ppm. IR (ATR, KBr): ν 3673, 3561, 3455, 3091, 3060, 2952, 2844, 2602, 1952, 1874, 1730, 1602, 1582, 1497, 1444, 1382, 1351, 1209, 1078, 1011, 956, 850, 766, 738, 697, 633, 560, 540, 525 cm−1. HRMS (EI, m/z) calcd for C14H16Cl2O3 [M]+: 302.0476; found: 302.0470.

3.2.8. 6,6-Dichloro-3-methyl-5-oxo-3-p-tolyl-hexanoic Acid Methyl Ester (2g)

Colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 2.88 (3H, s), 2.31 (3H, s), 2.86 (1H, d, J = 15.1 Hz), 2.95 (1H, d, J = 15.1 Hz), 3.40 (1H, d, J = 17.9 Hz), 3.46 (1H, d, J = 17.8 Hz), 3.58 (3H, s), 5.60 (1H, s), 7.13 (2H, d, J = 8.3 Hz), 7.21 (2H, d, J = 8.7 Hz) ppm. 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 20.9, 26.2, 38.7, 44.5, 45.1, 51.4, 70.4, 125.1, 129.2, 136.2, 142.4, 171.9, 194.8 ppm. HRMS (EI, m/z) calcd for C15H18Cl2O3 [M]+: 316.0633; found: 316.0628.

3.2.9. General Procedure for Synthesis of Trichloroketo Acid Methyl Esters

To a solution of 1,3-cyclohexadiones (1.0 mmol) and NCS (480.7 mg, 3.6 mmol) in MeOH (10 mL), Na2HPO4 (71.0 mg, 0.5 mmol) was added. After the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 0.5 h, the solvent was removed by evaporation. The product was dissolved in CH2Cl2, and then the extract was filtered through filter paper for dehydration. After evaporation for the removal of the solvent, the product was dissolved in hexane by sonication, and then the extract was filtered through filter paper. The concentrated filtrate by evaporation was purified by silica gel chromatography with AcOEt/hexane solution.

3.2.10. 6,6,6-Trichloro-5-oxo-hexanoic Acid Methyl Ester (3a)

Colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 2.08 (2H, quin, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.44 (2H, t, J = 7.1 Hz), 3.11 (1H, t, J = 7.2 Hz), 3.69 (3H, s) ppm. 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 19.9, 32.4, 32.9, 51.7, 96.2, 173.0, 190.1 ppm. IR (ATR, KBr): ν 3482, 2957, 2880, 2846, 2364, 2357, 2330, 1737, 1438, 1370, 1266, 1171, 1104, 1062, 1010, 958, 877, 821, 752, 699, 650, 634, 591, 561 cm−1. HRMS (FAB, m/z) calcd for C7H10Cl3O3 [M + H]+: 246.9696; found: 246.9697.

3.2.11. 6,6,6-Trichloro-3-methyl-5-oxo-hexanoic Acid Methyl Ester (3b)

Colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.07 (3H, d, J = 6.9 Hz), 2.34 (1H, dd, J = 15.5, 7.5 Hz), 2.43 (1H, dd, J = 15.5, 6.9 Hz), 2.64 (1H, o, J = 6.8 Hz), 2.98 (1H, dd, J = 17.8, 7.5 Hz), 3.11 (1H, dd, J = 17.6, 5.9 Hz), 3.69 (3H, s) ppm. 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 19.5, 27.0, 39.9, 40.1, 51.6, 96.4, 172.4, 189.3 ppm. IR (ATR, KBr): 3820, 3661, 3481, 2953, 2880, 2845, 2741, 2616, 2017, 1738, 1437, 1370, 1267, 1173, 1102, 1063, 1009, 957, 876, 819, 754, 704, 592, 553 cm−1. HRMS (FAB, m/z) calcd for C8H12Cl3O3 [M + H]+: 260.9852; found: 260.9854.

3.2.12. 6,6,6-Trichloro-5-oxo-3-phenyl-hexanoic Acid Methyl Ester (3c)

Colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 2.71 (1H, dd, J = 16.0, 7.3 Hz), 2.80 (1H, dd, J = 16.0, 7.3 Hz), 3.41 (2H, d, J = 7.3 Hz), 3.61 (3H, s), 3.80 (1H, quin, J = 7.4 Hz), 7.20–7.33 (5H, m) ppm. 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 37.0, 40.1, 40.2, 51.7, 55.2, 96.2, 114.0, 128.4, 133.6, 158.6, 171.9, 188.4 ppm. IR (ATR, KBr): 3474, 3447, 3085, 3063, 3031, 3008, 2956, 2933, 2905, 2848, 1968, 1953, 1889, 1731, 1693, 1603, 1583, 1496, 1455, 1438, 1425, 1378, 1362, 1258, 1218, 1166, 1102, 1077, 989, 918, 903, 876, 824, 764, 700, 610, 557, 542 cm−1. HRMS (EI, m/z) calcd for C14H13Cl3O3 [M]+: 321.9930; found: 321.9928.

3.2.13. 6,6,6-Trichloro-3-(4-methoxy-phenyl)-5-oxo-hexanoic Acid Methyl Ester (3d)

Colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 2.68 (1H, dd, J = 15.9, 7.9 Hz), 2.75 (1H, dd, J = 16.0, 7.3 Hz), 3.36 (2H, d, J = 6.9 Hz), 3.61 (3H, s), 3.70–3.83 (1H, m), 6.83 (2H, d, J = 8.7), 7.17 (2H, d, J = 8.7) ppm. 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 37.0, 40.1, 40.2, 51.7, 55.2, 96.2, 114.0, 128.4, 133.6, 158.6, 171.9, 188.4 ppm. IR (ATR, KBr): 3003, 2953, 2838, 1738, 1612, 1583, 1514, 1438, 1366, 1301, 1250, 1179, 1114, 1089, 1035, 874, 833, 747, 708, 549 cm−1. HRMS (EI, m/z) calcd for C15H15Cl3O4 [M]+: 352.0036; found: 352.0037.

3.2.14. 6,6,6-Trichloro-3,3-dimethyl-oxo-hexanoic Acid Methyl Ester (3e)

Colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.17 (6H, s), 2.58 (2H, s), 3.23 (2H, s), 3.66 (3H, s) ppm. 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 27.7, 32.8, 42.7, 44.1, 51.3, 96.7, 172.3, 189.2 ppm. IR (ATR, KBr): 3672, 3477, 3241, 2953, 2844, 2629, 2021, 1739, 1437, 1392, 1352, 1227, 1076, 1011, 881, 833, 748, 697, 652, 626, 560 cm−1. HRMS (EI, m/z) calcd for C9H14Cl3O3 [M + H]+: 275.0008; found: 275.0016.

3.2.15. 6,6,6-Trichloro-3-methyl-5-oxo-3-phenyl-hexanoic Acid Methyl Ester (3f)

Colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.63 (3H, s), 2.91 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz), 3.05 (1H, d, J = 15.1 Hz), 3.58 (3H, s), 3.71 (1H, d, J = 18.8 Hz), 3.77 (1H, d, J = 18.8 Hz), 7.20–7.25 (1H, m), 7.30–7.38 (4H, m) ppm. 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 25.7, 39.1, 42.9, 44.7, 51.5, 96.5, 125.3, 126.6, 128.5, 145.2, 171.8, 188.2 ppm. IR (ATR, KBr): ν 3670, 3489, 3091, 3060, 3026, 2952, 2843, 2602, 2017, 1949, 1873, 1731, 1602, 1583, 1498, 1436, 1383, 1347, 1277, 1206, 1082, 1013, 958, 874, 821, 758, 698, 632, 551, 535 cm−1.

3.2.16. 6,6,6-Trichloro-3-methyl-5-oxo-3-p-tolyl-hexanoic Acid Methyl Ester (3g)

Colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.60 (3H, s), 2.31 (3H, s), 2.94 (1H, d, J = 15.1 Hz), 3.03 (1H, d, J = 15.1 Hz), 3.59 (3H, s), 3.64 (1H, d, J = 18.8 Hz), 3.74 (1H, d, J = 18.8 Hz), 7.13 (2H, d, J = 8.2 Hz), 7.23 (2H, d, J = 8.2 Hz) ppm. 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 20.9, 25.8, 38.8, 42.9, 44.7, 51.5, 96.6, 125.2, 129.2, 136.2, 142.3, 171.9, 188.2 ppm. IR (ATR, KBr): ν 3508, 2952, 1901, 1735, 1517, 1436, 1417, 1381, 1347, 1277, 1204, 1097, 1077, 1013, 959, 877, 858, 816, 751, 708, 681, 661, 630, 602, 593, 551 cm−1. HRMS (EI, m/z) calcd for C15H17Cl3O3 [M]+: 320.0243; found: 320.0244.

3.2.17. General Procedure for Synthesis of Dichloroketo Acid Alkyl Esters

To a solution of a 1,3-cyclohexadione (1.0 mmol) and NCS (267.1 mg, 2.0 mmol) in alcohol (10 mL), Na2HPO4 (71.0 mg, 0.5 mmol) was added. After stirring the mixture at room temperature for 0.5 h, the solvent was evaporated. The product was dissolved in CH2Cl2, and the extract was filtered through filter paper for dehydration. After evaporating the solvent, the product was dissolved in hexane via sonication, and the extract was filtered through filter paper. The filtrate was concentrated by evaporation and purified by silica gel chromatography using an ethyl acetate (AcOEt)/hexane solution.

3.2.18. 6,6-Dichloro-5-oxo-hexanoic Acid Ethyl Ester (4)

Colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.26 (3H, t, J = 7.3 Hz), 2.00 (2H, quin, J = 7.3 Hz), 2.38 (2H, t, J = 7.3 Hz), 2.92 (2H, t, J = 7.3 Hz), 4.14 (2H, q, J = 7.3 Hz), 5.83 (1H, s) ppm 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 4.2, 18.9, 32.9, 33.8, 60.5, 69.8, 172.8, 196.7 ppm. IR (ATR, KBr): ν 3643, 3451, 2983, 1731, 1448, 1376, 1190, 1094, 1029, 858, 789, 735 cm−1. HRMS (EI, m/z) calcd for C8H13Cl2O3 [M + H]+: 227.0242; found: 227.0244.

3.2.19. 6,6-Dichloro-5-oxo-hexanoic Acid Propyl Ester (5)

Colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.94 (3H, t, J = 7.5 Hz), 1.65 (3H, sext, J = 7.3 Hz), 2.00 (2H, quin, J = 7.3 Hz), 2.39 (2H, t, J = 7.3 Hz), 2.93 (2H, t, J = 7.1 Hz), 4.05 (2H, t, J = 6.9 Hz), 5.83 (1H, s) ppm. 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 10.4, 18.9, 21.9, 32.8, 33.8, 66.2, 69.8, 172.9, 196.7 ppm. IR (ATR, KBr): ν 3446, 2969, 2880, 1732, 1459, 1395, 1379, 1314, 1185, 1089, 1061, 1002, 912, 849, 788, 736 cm−1. HRMS (EI, m/z) calcd for C9H14Cl2O3 [M + H]+: 241.0398; found: 241.0400.

3.2.20. 6,6-Dichloro-5-oxo-hexanoic Acid 2-Methoxy-Ethyl Ester (6)

Colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 2.01 (2H, q, J = 7.3 Hz), 2.44 (2H, t, J = 7.3 Hz), 2.93 (2H, t, J = 7.1 Hz), 3.39 (3H, s), 3.58–3.61 (2H, m), 4.24–4.26 (2H, m), 5.84 (1H, s) ppm. 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 18.9, 32.7, 33.8, 59.0, 63.6, 69.8, 70.4, 172.8, 196.7 ppm. 1 IR (ATR, KBr): ν 3632, 3449, 2936, 1732, 1452, 1407, 1380, 1127, 1033, 861, 784, 734, 534 cm−1. HRMS (EI, m/z) calcd for C9H14Cl2O4 [M + H]+: 257.0347; found: 257.0344.

3.2.21. 6,6-Dichloro-5-oxo-hexanoic Acid Butyl Ester (7)

Colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.94 (3H, t, J = 7.5 Hz), 1.38 (2H, sext, J = 7.6 Hz), 1.61 (2H, quin, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.00 (2H, quin, J = 7.3 Hz), 2.39 (2H, t, J = 7.3 Hz), 2.92 (2H, t, J = 7.1 Hz), 4.09 (2H, t, J = 6.9 Hz), 5.83 (1H, s) ppm. 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 13.7, 18.9, 19.1, 30.6, 32.9, 33.9, 64.5, 69.8, 172.9, 196.7 ppm. IR (ATR, KBr): ν 3620, 3449, 2961, 2874, 1732, 1457, 1394, 1314, 1188, 1063, 1024, 966, 845, 788, 731, 518 cm−1. HRMS (EI, m/z) calcd for C10H16Cl2O3 [M + H]+: 255.0555; found: 255.0552.

3.2.22. 6,6-Dichloro-5-oxo-hexanoic Acid Isobutyl Ester (8)

Colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.93 (6H, d, J = 6.8 Hz), 1.88–1.98 (1H, m), 2.00 (2H, quin, J = 7.3 Hz), 2.40 (2H, t, J = 7.3 Hz), 2.93 (2H, t, J = 7.1 Hz), 3.87 (2H, d, J = 6.9 Hz), 5.83 (1H, s) ppm. 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 18.9, 19.1, 27.7, 32.8, 33.9, 69.8, 70.7, 172.9, 196.7 ppm. IR (ATR, KBr): ν 3650, 3450, 2961, 2875, 1732, 1470, 1382, 1189, 1088, 1014, 946, 782, 728, 521 cm−1. HRMS (EI, m/z) calcd for C10H16Cl2O3 [M + H]+: 255.0555; found: 255.0552.

3.2.23. 7,7-Dichloro-5-oxo-heptanoic Acid Methyl Ester (10)

Colorless oil. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.67–1.72 (4H, m), 2.36 (2H, t, J = 6.9 Hz), 2.86 (2H, t, J = 6.9 Hz), 3.68 (3H, s), 5.84 (1H, s) ppm. 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 23.1, 24.1, 33.6, 34.5, 51.6, 69.8, 173.6, 196.9 ppm. HRMS (EI, m/z) calcd for C8H13Cl2O3 [M + H]+: 227.0242; found: 227.0243.

3.2.24. 8,8-Dichloro-5-oxo-octanoic Acid Methyl Ester (12)

Colorless oil. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.35–1.41 (2H, m), 1.63–1.72 (4H, m), 2.33 (2H, t, J = 7.5 Hz), 2.83 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz), 3.67 (3H, s), 5.82 (1H, s) ppm. 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 23.4, 24.5, 28.3, 33.8, 34.6, 51.5, 69.9, 174.0, 197.1 ppm. HRMS (EI, m/z) calcd for C9H15Cl2O3 [M + H]+: 241.0398; found: 241.0404.

3.2.25. 8,8,8-Trichloro-5-oxo-octanoic Acid Methyl Ester (13)

Colorless oil. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.41 (2H, quin, J = 7.7 Hz), 1.68 (2H, quin, J = 7.6 Hz), 1.77 (2H, quin, J = 7.4 Hz), 2.34 (2H, t, J = 7.5 Hz), 3.00 (2H, t, J = 7.5 Hz), 3.68 (3H, s) ppm. 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 24.4, 24.5, 28.3, 33.66, 33.75, 51.6, 96.4, 173.9, 190.5 ppm.

3.2.26. 5,5-Dichloro-5-oxo-pentanoic Acid Methyl Ester (15)

Colorless oil. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 2.70 (2H, t, J = 6.6 Hz), 3.16 (2H, t, J = 6.6 Hz), 3.70 (3H, s), 5.93 (1H, s) ppm. 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 27.9, 30.2, 52.0, 69.7, 172.4, 195.9 ppm. HRMS (EI, m/z) calcd for C6H9Cl2O3 [M + H]+: 198.9929; found: 198.9929.

3.2.27. 6-Bromo-6,6-dichloro-5-oxo-hexanoic Acid Methyl Ester (16)

Colorless oil. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 2.06 (2H, quin, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.42 (2H, t, J = 7.5 Hz), 3.14 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz), 3.67 (3H, s) ppm. 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 20.1, 32.4, 32.8, 51.7, 80.8, 173.1, 190.4 ppm. HRMS (EI, m/z) calcd for C7H10BrCl2O3 [M + H]+: 290.9190; found: 290.9194.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we identified a unique reaction system that facilitates the direct synthesis of di- and trichloroketoesters from cyclic 1,3-diketones at ambient temperatures. The use of Na2HPO4, which plays a key role in the alcoholytic ring-opening reactions of the 2,2-dichloro-1,3-diketones generated as intermediates, was demonstrated to yield haloketo acid methyl esters with high efficiency. The selective synthesis of dichloro and trichloro products can be modulated by the stoichiometry of the NCS. Although the mechanism by which Na2HPO4 influences C–C bond cleavage remains unclear, this method has significant potential for further derivatization. The integration of this method with various heterocycle formation techniques utilizing haloketo acids and their esters is anticipated to aid in the synthesis of diverse new compounds functionalized with or without halogen atoms.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/molecules31010199/s1, 1H and 13C NMR spectra of compounds 2a−g, 3a−g, 4−8, 10, 12, 13, 15, and 16.

Author Contributions

H.C. found the direct synthesis of di- or trichloroketo acid methyl esters from cyclic 1,3-diketones and drafted the manuscript; N.K., H.Y., M.F., Y.M., and Z.J. also contributed to the experiments; T.D. directed this study as a project and finalized the manuscript with critical discussion. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by JST CREST (grant number JPMJCR20R1) and the Ritsumeikan Global Innovation Research Organization (R-GIRO) project. H.C. also acknowledges support from a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (JSPS KAKENHI grant number 24K09738) from JSPS.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this work is in the article and Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shi, Y.; Tan, X.; Gao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Yin, Q. Direct synthesis of chiral NH lactams via Ru-catalyzed asymmetric reductive amination/cyclization cascade of keto acids/esters. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 2707–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Netkaew, C.; Darcel, C. Iron-catalysed switchable synthesis of pyrrolidines vs pyrrolidinones by reductive amination of levulinic acid derivatives via hydrosilylation. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2019, 361, 1781–1786. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Zhou, P.; Zhu, Z.; Guo, Y.; Lv, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, L. Multisite CuNi/Al2O3 catalyst enabling high-efficiency reductive amination of biomass-derived levulinic acid (esters) to pyrrolidones under mild conditions. ACS Catal. 2025, 15, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourelle-Insua, Á.; Zampieri, L.A.; Lavandera, I.; Gotor-Fernández, V. Conversion of γ- and δ-keto esters into optically active lactams. Transaminases in cascade processes. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2018, 360, 686–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Sun, X.; Yu, W.; Rai, R.; Deschamps, J.R.; Mitchell, L.A.; Jiang, C.; MacKerell, A.D.; Xue, F. Facile synthesis of spirocyclic lactams from β-keto carboxylic acids. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 3070–3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panda, S.; Nanda, A.; Saha, R.; Ghosh, R.; Bagh, B. Cobalt-catalyzed chemodivergent synthesis of cyclic amines and lactams from ketoacids and anilines using hydrosilylation. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 16997–17009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Tongdee, S.; Ammaiyappan, Y.; Darcel, C. A concise route to cyclic amides from nitroarenes and ketoacids under iron-catalyzed hydrosilylation conditions. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2021, 363, 3859–3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Xing, C.-G.; Zhang, C.; Zheng, Y.-C.; Pan, J.; Xu, J.-H.; Bai, Y.-P. Efficient stereoselective synthesis of structurally diverse γ- and δ-lactones using an engineered carbonyl reductase. ChemCatChem 2019, 11, 2600–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, N.; Namba, T.; Kawaguchi, K.; Matsumoto, Y.; Ohkuma, T. Chemoselectivity control in the asymmetric hydrogenation of γ- and δ-keto esters into hydroxy esters or diols. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 1386–1389. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Rodríguez, A.; Borzęcka, W.; Lavandera, I.; Gotor, V. Stereodivergent preparation of valuable γ- or δ-hydroxy esters and lactones through one-pot cascade or tandem chemoenzymatic protocols. ACS Catal. 2014, 4, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guijarro, D.; Pablo, Ó.; Yus, M. Synthesis of γ-, δ-, and ε-lactams by asymmetric transfer hydrogenation of N-(tert-butylsulfinyl)iminoesters. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 3647–3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machrouhi, F.; Pârles, E.; Namy, J.-L. Barbier-type reactions of cyclic acid anhydrides and keto acids mediated by an SmI2-(Nil2-catalytic) system preparation of disubstituted lactones. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 1998, 2431–2436. [Google Scholar]

- Wada, M.; Honna, M.; Kuramoto, Y.; Miyoshi, N. A Grignard-type addition of allyl unit to carbonyl compounds containing a carboxyl group by using BiCl3 Zn(0) allyl bromide. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1997, 70, 2265–2267. [Google Scholar]

- Mandal, A.K.; Jawalkar, D.G. Studies toward the syntheses of functionally substituted γ-butyrolactones and spiro-γ-butyrolactones and their reaction with strong acids: A novel route to α-pyrones. J. Org. Chem. 1989, 54, 2364–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhhang, S.; Lian, F.; Xue, M.; Qin, T.; Li, L.; Zhang, X.; Xu, K. Electrocatalytic dehydrogenative esterification of aliphatic carboxylic acids: Access to bioactive lactones. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 6622–6625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyanik, M.; Suzuki, D.; Yasui, T.; Ishihara, K. In situ generated (hypo)iodite catalysts for the direct α-oxyacylation of carbonyl compounds with carboxylic acids. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 5331–5334. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.-Y.; Huang, Y.-B.; Hu, B.; Li, K.-M.; Zhang, J.-L.; Zhang, X.; Yan, X.-Y.; Lu, Q. A bio-based click reaction leading to the dihydropyridazinone platform for nitrogen-containing scaffolds. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 2672–2680. [Google Scholar]

- Jha, A.; Naidu, A.B.; Abdelkhalik, A.M. Transition metal-free one-pot cascade synthesis of 7-oxa-2-azatricyclo[7.4.0.02,6]trideca-1(9), 10, 12-trien-3-ones from biomass-derived levulinic acid under mild conditions. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013, 11, 7559–7565. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Miyazaki, T.; Maekawa, H.; Yonemura, K.; Yamamoto, Y.; Yamanaka, Y.; Nishiguchi, I. Mg-promoted facile and selective intramolecular cyclization of aromatic δ-ketoesters. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 1598–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawata, A.; Takata, K.; Kuninobu, Y.; Takai, K. Indium-catalyzed retro-Claisen condensation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 7793–7795. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, C.B.; Rao, D.C.; Babu, D.C.; Venkateswarlu, Y. Retro-Claisen condensation with FeIII as catalyst under solvent-free condensation. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 2010, 2855–2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, M.A.; Huynh, V.T.; Hommelsheim, R.; Koenigs, R.M.; Nguyen, T.V. An efficient method for retro-Claisen-type C–C bond cleavage of diketones with tropylium catalyst. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 12970–12973. [Google Scholar]

- Chevella, D.; Thota, C.; Majumder, S. Amverlyst-15 catalysed retro-Claisen condensation of β-diketones with alcohols: A practical approach to synthesize estres and ketoesters. Mol. Catal. 2023, 548, 113408. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, G.-X.; Wen, J.; Lai, T.-T.; Xie, D.; Zhou, C.-H. Sequential Michael addition/Claisen condensation of aromatic β-diketones with α,β-unsaturated esters: An approach to obtain 1,5-ketoesters. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016, 14, 2390–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostinho, M.; Kobayashi, S. Strontium-catalyzed highly enantioselective Michael additions of malonates to enones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 2430–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasuda, M.; Chiba, K.; Ohigashi, N.; Katoh, Y.; Baba, A. Michael addition of stannyl ketone enolate to α,β-unsaturated esters catalyzed by tetrabutylammonium bromide and an ab initio theoretical study of the reaction course. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 7291–7300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.S.; White, M.C. Combined effects on selectivity in Fe-catalyzed methylene oxidation. Science 2010, 327, 566–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Chen, D.; Qian, S.; Zheng, Y.; Huang, S. Selective C–C bond cleavage of cycloalkanones by NaNO2/HCl. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 6525–6529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, H.; Duan, X.-H.; Yang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, L.-N. Visble light-driven, copper-catalyzed aerobic oxidative cleavage of cycloalkanones. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 8263–8273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatsuji, Y.; Kobayashi, Y.; Masuda, S.; Takemoto, Y. Azolium/hydroquinone organo-radical Co-catalysis: Aerobic C–C bond cleavage in ketones. Chem. Eur. J. 2021, 27, 2633–2637. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, H.; Duan, X.-H.; Liu, L.; Guo, L.-N. Metal-free, visible-light-induced selective C–C bond cleavage of cycloalkanones with molecular oxygen. Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 11690–11694. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Z.; Cai, X.; Li, J.; Dai, M. Catalytic cyclopropanol ring opening for divergent syntheses of γ-butyrolactones and δ-ketoesters containing all-carbon quaternary centers. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 5907–5914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, G.; Yi, H.; Sun, T.; Wang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, G.; Wang, J. Copper(I)-catalyzed chemoselective coupling of cyclopropanols with diazoesters: Ring-opening C–C bond formations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 3945–3950. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Xi, S.; Wang, Q.; Fu, L.; He, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, M. Facile synthesis of δ-ketoesters via formal two-carbon insertion into β-ketoesters. Tetrahedron Lett. 2022, 92, 153656. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, R.-D.; Hin, N.; Prchalová, E.; Pal, A.; Lam, J.; Rais, R.; Slusher, B.S.; Tsukamoto, T. Medel studies towards prodrugs of the glutamine antagonist 6-diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine (DON) containing a diazo precursor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 50, 128321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, P.; Ravelli, D.; Wu, J. Direct synthesis of thioesters from feedstock chemicals and elemental sulfur. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 5846–5854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wen, J.; Yao, L.; Nie, H.; Jiang, R.; Chen, W.; Zhang, X. Highly chemo- and enantioselective hydrogenation of 2-substituted-4-oxo-2-alkenoic acids. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 4812–4816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, F.A.; Zhang, H.; Lee, S.H. Masked oxo sulfinimines (N-sulfinyl imines) in the asymmetric synthesis of proline and pipecolic acid derivatives. Org. Lett. 2001, 3, 759–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kluender, H.C.E.; Benz, G.H.H.H.; Brittelli, D.R.; Bullock, W.H.; Combs, K.J.; Dixon, B.R.; Schneider, S.; Wood, J.E.; Vanzandt, M.C.; Wolanin, D.J.; et al. Derivatives of Substituted 4-Biarybutyric Acid as Matrix Metalloprotease Inhibitors. U.S. Patent 5,789,434A, 4 August 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Pashikanti, G.; Chavan, L.N.; Liebeskind, L.S.; Goodman, M.M. Synthetic efforts toward the synthesis of a fluorinated analog of 5-aminolevulinic acid: Practical synthesis of racemic and enantiomerically defined 3-fluoro-5-aminolevulinic acid. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 89, 12176–12186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, R.; Ghosh, S.K. Enantioselective route to b-silyl-d-keto esters by organocatalyzed regioselective Michael addition of methyl ketones to a (silylmethylene)malonate and their use in natural product synthesis. Synthesis 2011, 2011, 1936–1945. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.-Y.; Bin, H.-Y.; Wei, T.; Cheng, H.-A.; Lin, Z.-P.; Fu, X.-F.; Li, Y.-Q.; Xie, J.-H.; Yan, P.-C.; Zhou, Q.-L. Iridium-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation of g- and d-ketoacids for enantioselective synthesis of g- and d-lactones. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 818–822. [Google Scholar]

- Krabbe, S.W.; Johnson, J.S. Asymmetric total syntheses of megacerotonic acid and Shimobashiric acid A. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 1188–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, N.; Cleator, E.; Kosjek, B.; Yin, J.; Xiang, B.; Chen, F.; Kuo, S.C.; Belyk, K.; Mullens, P.R.; Goodyear, A.; et al. Practical asymmetric synthesis of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor antagonist subrogepant. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2017, 21, 1851–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.-H.; Xie, J.-H.; Liu, W.-P.; Zhou, Q.-L. Catalytic asymmetric hydrogenation of δ-ketoesters: Highly efficient approach to chiral 1,5-diols. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 7833–7836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannopoulos, V.; Smonou, I. Asymmetric reaction of α,α-dichloro-β-keto esters by NADPH-dependent ketoreductases. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 2022, e202200410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fager, D.C.; Lee, K.; Hoveyda, A.H. Catalytic enantioselective addition of an allyl group to ketones containing a tri-, a di-, or a monohalomethyl moiety. Stereochemical control based on distinctive electronic and steric attributes of C–Cl, C–Br, and C–F bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 16125–16138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.-S.; Phansavath, P.; Ratovelomanana-Vidal, V. Synthesis of enantioenriched α,α-dichloro- and α,α-difluoro-β-hydroxy esters and amides by ruthenium-catalyzed asymmetric transfer hydrogenation. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 5107–5111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, M.; Zheng, Y.; Terell, J.L.; Ad, M.; Opoku-Temeng, C.; Bentley, W.E.; Sintim, H.O. Geminal dihalogen isosteric replacement in hydrated Al-2 affords potent quorum sensing modulators. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 2617–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concellón, J.M.; Rodríguez-Solla, H.; Concellón, C.; Díaz, P. Synthesis of E-α,β-unsaturated ketones with complete stereoselectivity via sequential aldol-type/elimination reactions promoted by samarium-diiodide or chromium dichloride. Synlett 2006, 2006, 837–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppe, C.; das Chagas, R.P. Indium(I) bromide-promoted stereoselective preparation of (E)-α,β-unsaturated ketones via sequential intermolecular aldol-type coupling/elimination reactions of α,α-dichloroketones with aldehydes. J. Organometal. Chem. 2006, 691, 5856–5860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasai, H.; Arai, S.; Shibasaki, M. Catalytic aldol reaction with Sm(HMDS)3 and its application for the introduction of a carbon–carbon triple bond at C-13 in prostaglandin synthesis. J. Org. Chem. 1994, 59, 2661–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthore-Dalion, L.; Zard, S.Z. Chemoselective reduction: Xanthates as traceless precursors of polyfunctionalized α,α-dichloroketones. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 5545–5548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthore, L.; Li, S.; White, L.V.; Zard, S.Z. Radical solution to the alkylation of the highly base-sensitive 1,1-dichloroacetone. Application to the synthesis of Z-alkenoates and E,E-dienoates. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 5320–5323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grainger, R.S.; Owoare, R.B.; Tisselli, P.; Steed, J.W. A synthetic alternative to the type-II intramolecular 4 + 3 cycloaddition reation. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 7899–7902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganiek, M.A.; Ivanova, M.V.; Martin, B.; Knochel, P. Mild homologation of esters through continuous flow chloroacetate Claisen reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 17249–17253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzschneider, K.; Häring, A.P.; Haack, A.; Corey, D.J.; Benter, T.; Kirsch, S.F. Pathways in degradation of geminal diazides. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 8242–8250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Zou, H.; Dong, Q.; Wang, R.; Lu, L.; Zhu, Y.; He, W. Synthesis of 2-keto(hetero)aryl benzox(thio)azoles through base promoted cyclization of 2-amino(thio)phenols with α,α-dihaloketones. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limanto, J.; Desmond, R.A.; Gauthier, D.R., Jr.; Devine, P.N.; Reamer, R.A.; Volante, R.P. A regioselective approach to 5-substituted 3-amino-1,2,4-triazines. Org. Lett. 2003, 5, 2271–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morimoto, H.; Yoshino, T.; Yukawa, T.; Lu, G.; Matsunaga, S.; Shibasaki, M. Lewis base assisted Brønsted base catalysis: Bidentate phosphine oxides as activators and modulators of Brønsted basic lanthanum–aryloxides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 9125–9129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morimoto, H.; Lu, G.; Aoyama, N.; Matsunaga, S.; Shibasaki, M. Lanthanum aryloxide/pybox-catalyzed direct asymmetric Mannich-type reactions using a trichloromethyl ketone as a propionate equivalent donor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 9588–9589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, H.; Wiedemann, S.H.; Yamaguchi, A.; Harada, S.; Chen, Z.; Matsunaga, S.; Shibasaki, M. Trichloromethyl ketones as synthetically versatile donors: Application in direct catalytic mannich-type reactions and the stereoselective synthesis of azetidines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 3146–3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perryman, M.S.; Harris, M.E.; Foster, J.L.; Joshi, A.; Clarson, G.J.; Fox, D.J. Trichloromethyl ketones: Asymmetric transfer hydrogenation and subsequent Jocic-type reactions with amines. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 10022–10024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rexit, A.A.; Hu, X. Intermolecular atom transfer radical addition of α,α,α-trichloromethyl ketones and alkenes mediated by a CuCl/bpy system. Tetrahedron 2015, 71, 2313–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essa, A.H.; Lerrick, R.I.; Çiftci, E.; Harrington, R.W.; Waddell, P.G.; Clegg, W.; Hall, M.J. Grignard-mediated reduction of 2,2,2-trichloro-1-arylethanones. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 5793–5803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrill, L.C.; Stark, D.G.; Taylor, J.E.; Smith, S.R.; Squires, J.A.; D’Hollander, A.C.A.; Simal, C.; Shapland, P.; O’Riordan, T.J.C.; Smith, A.D. Organocatalytic Michael addition lactonisation of carboxylic acids using α,β-unsaturated trichloromethyl ketones as α,β-unsaturated ester equivalents. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014, 12, 9016–9027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attaba, N.; Taylor, J.E.; Slawin, A.M.Z.; Smith, A.D. Enantioselective NHC-catalyzed redox [4 + 2]-hetero-Diels–Alder reaction using α,β-unsaturated trichloromethyl ketones as amide equivalents. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 9728–9739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China, H.; Yoto, Y.; Sasa, H.; Kikushima, K.; Dohi, T. Reconstructive synthesis of fluorinated dihydropyrido[1,2-a]indolones by a cyclohexadiones cut-to-fuse strategy. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2025, 367, e202401037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China, H.; Okada, Y.; Dohi, T. The multiple reactions in the monochlorodimedone assay: Discovery of unique dehalolactonizations under mild conditions. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2015, 4, 1065–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China, H.; Yatabe, H.; Kageyama, N.; Fujitake, M.; Kikushima, K.; Dohi, T. New syntheses of haloketo acid methyl esters and their transformation to halolactones by reductive cyclization. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2020, 69, 1804–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.-B.; Zhao, H.-Y.; Zhang, J.; Thiemann, T. Raney Ni-Al alloy mediated hydrodehalogenation and aromatic ring hydrogenation of halogenated phenols in aqueous medium. J. Chem. Res. 2009, 2009, 342–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.; Watanabe, A.; Noyori, R. Palladium(0)-catalyzed reaction of α,β-epoxy ketones leading to β-diketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980, 102, 2095–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, T.; Kadoya, R.; Arai, M.; Takahashi, H.; Kaisi, Y.; Mizuta, T.; Yoshikai, K.; Saito, S. Revisiting [3+3] route to 1,3-cyclohexanedione frameworks: Hidden aspect of thermodynamically controlled enolates. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 66, 8000–8009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Bandna; Shil, A.K.; Singh, B.; Das, P. Consecutive Michael–Claisen process for cyclohexane-1,3-dione derivative (CDD) synthesis from unsubstituted and substituted acetone. Synlett 2012, 23, 1199–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Benmohamed, R.; Arvanites, A.C.; Morimoto, R.I.; Ferrante, R.J.; Kirsch, D.R.; Silverman, R.B. Cyclohexane 1,3-diones and their inhibition of mutant SOD1-dependent protein aggregation and toxicity in PC12 cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012, 20, 1029–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirihara, M.; Kakuda, H.; Ichinose, M.; Ochiai, Y.; Takizawa, S.; Mokuya, A.; Okubo, K.; Hatano, A.; Shiro, M. Fragmentation of tertiary cyclopropanol compounds catalyzed by vanadyl acetylacetonate. Tetrahedron 2005, 61, 4831–4839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, E.A.; DeForest, C.A.; Anseth, K.S. A mild, large-scale synthesis of 1,3-cyclooctanedione: Expanding access to difluorinated cyclooctyne for copper-free click chemistry. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 1871–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.K. An exceptionally facile reaction of α,α-dichloro-β-keto esters with bases. J. Org. Chem. 1973, 38, 4081–4982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-M.; Yi, W.-B.; Shen, W.-Z.; Lu, G.-P. A route to α-fluoroalkyl sulfides from α-fluorodiaroylmethanes. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 592–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leng, D.J.; Black, C.M.; Pattison, G. One-pot synthesis of difluoromethyl ketones by a difluorination/fragmentation process. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016, 14, 1531–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Z.; Lam, Y.-P.; Chan, K.-S.; Yeung, Y.-Y. Zwitterion-catalyzed deacylative dehalogenation of β-oxo amides. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 7353–7357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, X.; Li, Q.; Lu, Z.; Yang, X. N-Chloro-N-methoxybenzenesulfonamide: A chlorinating reagent. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 2016, 5937–5940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, D.; Huang, P.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, R.; Liang, Y.; Dong, D. Divergent synthesis of α,α-dihaloamides through α,α-dihalogenation of β-oxo amides by using N-halosuccinimides. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 2013, 5376–5380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, W.; Chen, C.; Tan, L. Approach for the direct synthesis of β-dichlorosubstituted acetanilides using iodine trichloride (ICl3) as the oxidant and catalyst. Chin. J. Chem. 2013, 31, 453–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.-B.; Chen, C.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, Z.-B. Organic synthesis using (diacetoxyiodo)benzene (DIB): Unexpected and novel oxidation of 3-oxo-butanamides to 2,2-dihalo-N-phenylacetamides. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2012, 8, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Ohashi, M.; Hung, Y.-S.; Scherlach, K.; Watanabe, K.; Hertweck, C.; Tang, Y. AoiQ catalyzes geminal dichlorination of 1,3-diketone natural products. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 7267–7271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podzelinska, K.; Latimer, R.; Bhattacharya, A.; Vining, L.C.; Zechel, D.L.; Jia, Z. Chloramphenicol biosynthesis: The structure of CmlS, a flavin-dependent halogenase showing a covalent flavin-aspartate bond. J. Mol. Biol. 2010, 397, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Buyck, L.; De Prooter, H.; Schamp, N. Hexachlorodimedone: Ring opening and intermolecular substitution of halogen. Preparation of γ, δ-diketoacids and esters. Bull. Soc. Chim. Belg. 1988, 97, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee-Ruff, E.; Hopkinson, A.C.; Kazarians-Moghaddam, H. Photochemistry of α,α-disubstituted bicyclic cyclobutanones—A potential thermal-photochemical metathesis reaction. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983, 24, 2067–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigg, M.G.; Roberts, S.M.; Suschitzky, H. Stereocontrolled addition of some sulfenyl halides to bicyclo[3.2.0]hept-2-en-6-ones and modification of the adducts. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1 1981, 926–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donskaya, N.A.; Bessmertnykh, A.G.; Drobush, V.A.; Shabarov, Y.S. Sterically shielded halocyclobutanones. I. Reactions of cyclopropyl-substituted 2,2-dichlorocyclobutanes with potassium hydroxide. Zhu. Org. Khim. 1987, 23, 745–751. [Google Scholar]

- Gaidamaka, S.N.; Benzmenova, T.E.; Shantalii, O.A.; Usenko, Y.N.; Varshavets, T.N.; Rozko, A.N. Synthesis and reaction of 2,2-dichloro-3-oxothiolane 1,1-dioxide with some nucleophiles. Zhu. Org. Khim. 1988, 24, 1726–1731. [Google Scholar]

- Chernova, L.N.; Simonov, V.D. Reaction of perchloro-2-cyclopenten-1-one and perchloro-4-cyclopentene-1,3-dione with ammonia and aliphatic amines. Zhu. Org. Khim. 1980, 16, 1653–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, P.R.; Duke, A.J. Ring-opening reactions of 7,7-dichlorobicyclo[3.2.0]hept-2-en-6-one and its conversion into methyl benzoate with methoxide ion. J. Chem. Soc. C 1971, 1764–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heard, D.M.; Lennox, A.J.J. Dichloromeldrum’s acid (DiCMA): A practical and green amides dichloroacetylation reagent. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 3368–3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China, H.; Okada, Y.; Dohi, T. Suppression mechanism for enol-enol isomerization of 2-substituted dimedones. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2015, 4, 952–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Deeb, I.Y.; Funakoshi, T.; Shimomoto, Y.; Matsubara, R.; Hayashi, M. Dehydrogenative formation of resorcinol derivatives using Pd/C–ethylene catalytic system. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 2630–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halili, M.A.; Bachu, P.; Lindahl, F.; Bechara, C.; Mohanty, B.; Reid, R.C.; Scanlon, M.J.; Robinson, C.V.; Fairlie, D.P.; Martin, J.L. Small molecule inhibitors of disulfide bond formation by the bacterial DsbA–DsbB dual enzyme system. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015, 10, 957–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.