Abstract

Mini-LC systems, including Cap-LC, Nano-LC and Chip-LC, offer a sustainable alternative to conventional LC methods thanks to their reduced solvent consumption, enhanced separation efficiency and environmentally friendly operation. Integrating micro-scale sample preparation techniques, such as µ-SPE, IT-SPME, LPME and QuEChERS, with Mini-LC significantly improving analytical sensitivity and selectivity. Mini-LC coupled with mass spectrometry has demonstrated excellent performance in the detection of trace levels of pesticides, pharmaceuticals, veterinary drug residues, perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs), and mycotoxins. Despite current challenges relating to matrix effects, instrument stability and method standardization, Mini-LC represents a promising analytical platform for the cost-effective, high-sensitivity, green monitoring of contaminants in food safety and environmental analysis. This review summarizes recent advances in the application of Mini-LC techniques for analyzing emerging organic contaminants (EOCs) in food and environmental samples. This paper also provides a critical review of this topic, covering works published in the last four years (early 2022–mid 2025). Additionally, it discusses the use of these techniques in combination with mass spectrometry (e.g., low-resolution MS or high-resolution MS) for the detection of EOCs in food and environmental samples.

1. Introduction

Miniaturized-LC (Mini-LC) systems have attracted increasing attention due to their potentials as advanced chromatographic separation processes. These highly adaptable platforms allow for the sensitive analysis of a variety of compounds [1]. When used with mass spectrometry, these systems greatly enhance analyte ionization efficiency. Mini-LC is widely used in several fields including proteomic and metabolomic mixtures of new chemical entities [2,3,4], food safety [5,6], pharmaceuticals [7], molecular toxicology [8] and drug discovery [9]. One of the most notable advantages of Mini-LC is the reduced consumption of chemicals, which not only lowers costs, but also minimizes environmental impact. In the context of Mini-LC systems, narrow columns with an internal diameter (ID) of less than 1 mm are used, which significantly reduces injection volumes and flow rates. Different types of columns are used in Mini-LC, such as particle-packed [10], monolithic columns [7] and open tubular columns [11]. Micro-pillar array columns and chip columns are also used in Mini-LC or portable-LC systems [12]. Although particle-packed columns are widely used in Mini-LC, monolithic columns are a promising alternative material. Monolithic columns have several features, such as lower back pressure and high versatility [13]. These narrow bore columns offer several notable benefits, including reduced chromatographic dilution, lower solvent consumption, and greater efficiency. However, these benefits come with challenges, such as the fact that the dead volume becomes more significant at reduced scales, potentially leading to band broadening. Researchers have addressed this issue by using connecting tubing with very small inner diameter and zero dead volume fittings to minimize the overall dead volume of the setup [14].

Mini-LC techniques are also a rapidly emerging tool for analyzing organic contaminants and detecting low-abundance contaminants such as organic pollutants in different samples that require higher sensitivity. Recently, the importance of EOCs has grown significantly, mainly due to advancements in miniaturized analytical systems that allow for their detection at high sensitivity, typically ranging from nanograms to micrograms per liter. Research has shown that surface waters and wastewater contain endocrine-disrupting compounds (EDCs), such as hormones and pharmaceuticals. This illustrates the inefficiency of traditional wastewater treatment methods in eliminating these pollutants. Thereupon, researchers and public health advocates are increasingly concerned about these pollutants because they can accumulate in nature, persist in the environment for extended periods, and cause harmful effects.

The analysis of organic pollutants is a key issue in environmental analytical chemistry. The production and consumption of harmful chemicals have resulted in thousands of compounds being discharged into the environment. The high persistence and mobility of some of these substances causes them to migrate away from the site of application, reaching surface and groundwater, and consequently bioaccumulating in the food chain [15]. The EU Water Framework Directive established controls on a list of persistent chemicals in the environment that can bioaccumulate and pose a risk to human health and the environment [16]. These regulated compounds are controlled and monitored worldwide using analytical methods. Many substances classified as priority pollutants are pesticides, such as organochlorides, organophosphates, triazines and sulfonylureas. There are several regulations concerning the application of pesticides and concentration limits in the environment and in drinking water [17,18]. The legal limit for individual pesticides in drinking water is generally 0.1 µg L−1, while the limit for total pesticides is 0.5 µg L−1. For surface waters, the environmental quality standard varies for each pesticide, ranging from ng L−1 to µg L−1 [19]. EOCs, which include pharmaceuticals, personal care products, pesticides, plasticizers and industrial additives, are increasingly being detected at trace levels in food and environmental matrices, posing risks to both the environment and human health. For example, antibiotic residues in dairy products and aquaculture environments have been linked to antimicrobial resistance, and persistent plasticizers such as bisphenol A and phthalates have been shown to disrupt the endocrine system in wildlife and humans. Furthermore, trace-level herbicides and pharmaceutical metabolites found in surface water can bio-accumulate through the food chain, thereby adversely affecting aquatic ecosystems and entering the food supply. These findings highlight the urgent need for robust, sensitive and sustainable analytical strategies to monitor and mitigate EOCs in complex matrices. In this context, Mini-LC technologies offer significant advantages by combining high separation efficiency with reduced solvent consumption and enhanced portability. This makes them particularly suitable for on-site, high-throughput analysis of EOCs in food safety and environmental assessment.

Miniaturization and automation are becoming an ever-popular necessity in modern chromatography [20]. In this sense, Mini-LC is achieved through reduction in the analytical column internal diameter, which is directly related to the system flow rate [21]. The development of portable LC instruments and on-line sample processing methods that make in situ analysis feasible has significantly contributed to the advanced organic contaminant analysis in both environmental monitoring and other fields. This review article summarizes the fundamental principles of Mini-LC systems, discusses technological developments and analysis strategies, and reports on some recent applications involving mass spectrometry (e.g., low-resolution and high-resolution MS) from 2022 to the present day.

2. Emerging Organic Contaminants

Emerging organic contaminants are substances that can be present in certain foodstuffs or different samples due to environmental contamination, production processes, cultivation practices, or environmental contamination. Recently, in response to regulated contaminants (pesticides, veterinary drugs, toxins, food and plant contaminants, etc.) several substances have emerged as EOCs, which can be defined as unregulated and recently discovered potentially harmful to human health. These EOCs have become a hot topic in the critical issue of 21st-century food and environmental safety, which poses a serious threat to human health and life worldwide [22] due to their toxicity mechanisms not being fully understood. Legislation is being revised to include new information that had not previously been taken into account, and tested methodologies have improved [23]. Recent studies have investigated certain types of EOCs, looking into where they come from, how they get there, and what they do. Agricultural runoff often contains herbicides and pesticides that pollute nearby bodies of water [24,25]. Studies have shown how EOCs impact aquatic organisms, complicating the ecosystems they invade [26]. Furthermore, when environmentally relevant contaminants interact with other pollutants, their combined effects can intensify both ecological damage and toxicity, resulting in a greater overall impact than either substance alone [27].

Addressing the challenges related to EOCs requires a multidisciplinary approach that unites expertise in toxicology, environmental science, and analytical chemistry. New methods for treating water, such as advanced oxidation processes and biofiltration, are being explored to determine their effectiveness in removing EOCs. At the same time, better ways to monitor water quality are being developed to detect EOCs more effectively [28]. It is crucial for regulatory agencies, businesses, and research institutions to collaborate in establishing rules for managing and mitigating the risks associated with EOCs. The challenge posed by EOCs necessitates an ongoing commitment to research and innovation in both analysis and remediation strategies. The chemical complexity of EOCs requires analytical platforms that can deliver high sensitivity and resolution, as well as the ability to quickly handle low sample volumes. A major area of research is finding better ways to analyze these species, such as using Mini-LC techniques to improve the sensitivity and specificity of detection. Mini-LC systems are a useful alternative to traditional LC systems as they are easier to transport, use less solvent and can achieve high-efficiency separations in a more compact format.

Mini-LC techniques are becoming increasingly important for determining contaminants because they transfer mass more efficiently, broaden signal peaks less and are compatible with low-volume, high-throughput workflows. This is especially useful given that emerging organic pollutants are usually found in very small amounts, in complicated matrices and in a wide range of structures. Not only is Mini-LC a useful addition to existing methods, it is also a necessary step forward in solving current analytical problems in EOC analysis.

3. Sample Preparation for the Determination of EOCs in Mini-LC

The analysis of EOCs such as pharmaceuticals, personal care products, pesticides, and industrial chemicals is notoriously challenging due to their low concentrations in complex environmental, food, and biological matrices [29]. The transition from conventional HPLC to Mini-LC systems encompassing capillary-LC (Cap-LC), Nano-LC and Chip-LC presents a paradigm shift in analytical science, offering enhanced mass sensitivity, reduced solvent consumption, and superior compatibility with mass spectrometry (MS) [30]. However, this miniaturization places stringent demands on the sample introduction process. The core challenge lies in the volumetric mismatch between typical sample preparation volumes (microliters) and the nanoliter-scale injection volumes required to maintain chromatographic efficiency in Mini-LC [31]. Traditional sample preparation methods are not well-suited for Mini-LC, as they can require large solvent volumes and introduce significant dead volume, negating the sensitivity benefits of miniaturization. The field has therefore shifted towards developing miniaturized, selective, and efficient sample preparation strategies that are seamlessly compatible with Mini-LC systems [32]. Sample preparation is a critical step in Mini-LC analysis of EOCs, as the reduced column dimensions and low flow rates necessitate highly efficient extraction and pre-concentration techniques to achieve optimal sensitivity and reproducibility [1]. Due to the trace-level concentrations of EOCs in complex matrices (e.g., environmental waters, biological fluids, and food samples), effective sample cleanup and enrichment are essential [33]. Solid-phase extraction (SPE) remains the most widely used method, offering high selectivity through various sorbents (e.g., C18, hydrophilic-lipophilic balance, molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs), and mixed-mode phases) tailored for specific contaminant classes such as pharmaceuticals, pesticides, or PFAS [34]. For even greater sensitivity, miniaturized SPE (µ-SPE) and dispersive SPE (d-SPE) reduce solvent consumption and improve extraction efficiency [35].

Recently, Andreasidou et al. [36] developed an acrylic copolymer-based dispersive solid-phase microextraction (d-µ-SPE) method for extracting 24 endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) from wastewater, followed by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis. This method has a low LOD (2–92 ng L−1) and LOQ (6–279 ng L−1), and a wide linear range of 100–33,300 ng L−1. Liquid-phase microextraction (LPME) methods, including dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction (DLLME) and hollow-fiber LPME (HF-LPME), provide significant enrichment factors while reducing co-extracted matrix interferences. Recently, Domínguez-Liste et al. [37] developed a liquid–liquid extraction (LLE) method for extracting endocrine-disrupting chemicals from semen, followed by LC-MS/MS analysis. This method showed a low LOD of 0.02–0.3 ng mL−1 and good recovery rates of 85.5–112.5%. PFAS and phenolic EDCs were quantified in serum samples from 21 volunteers. QuEChERS is commonly used to analyze multi-residue analytes in different samples, and it can be combined with µ-SPE or online cleanup to produce extracts suitable for Mini-LC. Nguyen and Baduel [38] developed a QuEChERS-based UPLC-MS/MS method for extracting, purifying and analyzing 90 EOCs, including pharmaceuticals, flame retardants, plasticisers and PFAS, in soil and sediment. The developed method demonstrated good accuracy, precision, and recovery (70–120% with RSD <20%), as well as good linearity, low matrix effects, and low LOQs (0.25–10 µg kg−1). More details on the comparison of miniaturized sample preparation techniques for mini-LC analysis of EOCs were given in Table S1.

Recent advancements in on-line sample preparation, such as in-tube solid-phase microextraction (IT-SPME) and turbulent flow chromatography (TFC), enable direct coupling with Mini-LC systems, enhancing automation and reducing analyte loss [39]. Despite these innovations, challenges remain, including matrix effects, the need for stringent method optimization, and the limited loading capacity of Mini-LC columns [12]. The success of any Mini-LC analysis hinges on a robust and efficient sample introduction (i.e., injection) system. The core challenge is introducing a representative, narrow sample plug into the separation column with minimal band broadening and without compromising the system’s low volumetric flow rates [30]. In capillary and Nano-LC, where flow rates are in the microliter to nL/min range, even minor dead volumes in the injection pathway can significantly degrade chromatographic resolution [40].

The development of robust, precise, and low-dispersion sample introduction techniques is essential for advancing Mini-LC applications in EOC analysis. Several injection strategies have been developed to meet these demands. A widely adopted solution is the use of integrated trap columns in a “capture-and-elute” configuration [41]. This approach allows for the loading of a relatively large sample volume (e.g., up to 100 µL) onto a trap column at a higher flow rate. Subsequent valve switching directs the mobile phase to flush the concentrated analytes from the trap column onto the analytical column for separation. This method effectively addresses the injection volume mismatch in Nano-LC, pre-concentrates analytes to enhance sensitivity, and enables the on-line desalting or purification of complex samples like food and environmental water extracts or biological fluids. For instance, in the analysis of emerging organic micropollutants in river water, offline SPE is often used as a preliminary concentration and cleanup step, with the final extract being reconstituted in a small volume compatible with Mini-LC injection [42]. Moreover, advancements in microfluidic Chip-LC systems represent the pinnacle of integration. These chips seamlessly incorporate nano-scale injection valves and sample loops directly onto the device, drastically reducing dead volume and ensuring the sample plug is introduced with high precision [43]. The evolution towards these fully integrated, automated injection systems is critical for enhancing the reproducibility, robustness, and analytical performance of Mini-LC methods in the routine monitoring of emerging contaminants. Future trends focus on integrating nanomaterials (e.g., graphene oxide, carbon nanotubes) and bioaffinity-based extraction methods (e.g., immunosorbents, aptamers) to improve selectivity and detection limits. Overall, the development of efficient, green, and high-throughput sample preparation techniques is crucial to unlocking the full potential of Mini-LC in EOC analysis.

3.1. Challenges of Sample Preparation for Mini-LC

A key element of Mini-LC workflows is the introduction of samples with low dispersion. Due to the production of very small peak volumes by narrow-bore columns, even slight dead volumes in valves, connectors or injection loops can greatly diminish chromatographic efficiency [44]. Of the available strategies, trap-and-elute setups have emerged as the most commonly used for EOC analysis. A compact trap column enables several microlitres of sample to be introduced at elevated flow rates, followed by valve switching and backflushing into the analytical column [15]. This method addresses the discrepancy in injection volume, improves sensitivity and offers online desalting or purification for complex matrices such as food extracts, wastewater and biological fluids. In river water analysis, solid-phase extraction (SPE) is often performed offline to minimize sample volume, with final reconstitution occurring in a solvent suitable for Mini-LC prior to trap-and-elute injection [42]. In Mini-LC, the injection method must provide a precise, narrow sample plug for narrow-bore columns; usual injection volumes are just a few nanolitres. Larger injections lead to instant band widening and reduced efficiency. Due to the very low peak volumes in nano-LC, even minor dead volumes in valves, loops or fittings can disrupt analyte focusing. Consequently, efficient Mini-LC injection systems depend on low-dispersion components and techniques that focus analytes at the column entrance immediately after introduction.

Several injection methods have been developed to overcome the stringent volume and dispersion constraints of Mini-LC. The choice of method is influenced by the intricacy of the matrix, the required sensitivity and the configuration of the system. Micro-volume rotary valves with loops ranging from 10 nL to 1 µL provide an easy method for delivering small, precisely defined volumes. Mazzoni et al. [45] developed an online SPE/UHPLC-MS/MS method for determining perfluoroalkyl acids in drinking and surface waters. The extraction-to-analysis process took 20 min, and the validated method was used to determine PFFA in waters collected from various locations in Italy. The trap-and-elute setup is the most commonly employed Mini-LC injection method for complex matrices. A short trap column retains analytes while large-volume samples are loaded, allowing unretained matrix elements to be flushed away. Following the valve switch, the analytes are released in a tight band onto the analytical column. This method increases sensitivity, enhances matrix clean-up and reduces extra-column dispersion, making it particularly beneficial for trace-level endocrine-disrupting compound (EDC) analysis in food and environmental samples. Recently, Zhao et al. [46] developed a hybrid monolithic in-tube SPME-UPLC-MS/MS method for the quantification of cannabinoids. This method successfully quantified ten cannabinoids in human urine samples and sewage water, achieving good recovery rates (85.5–112%).

3.2. Considerations for Specific Matrices in EOC Analysis

The choice of sample introduction method for Mini-LC is heavily influenced by the complexity of the matrix. For clean aqueous samples such as surface water or wastewater, trap-LC is particularly efficient as it allows direct loading of several microlitres while concentrating trace EOCs and removing particulates. More intricate matrices, such as urine, plasma and various biological fluids, typically require offline dilution or protein precipitation prior to online trapping. In this case, the trap column serves as both a preconcentration unit and a safeguard for the analytical column. Similarly, food and environmental samples benefit from offline solid-phase extraction (SPE), followed by trap-LC, to achieve final purification and analyte concentration. In summary, the progression from basic nano-loop injections to combined trap-and-elute and chip-based technologies has enabled Mini-LC to process more complex samples. Ongoing improvements in automation and minimized dead volumes are anticipated to further enhance performance [45].

4. Mini-LC Systems

EOCs are a growing class of compounds that are being separated and detected in various samples, attracting significant attention. These contaminants include pesticides, pharmaceuticals, persistent organic pollutants, perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs), secondary metabolite contaminants and synthetic organic compounds. Recent advances in Mini-LC systems combined with low-resolution (ion trap or triple quadrupole) or high-resolution (Q-Exactive or Q-TOF) MS have begun to shed light on the distribution patterns and potential health risks associated with these substances.

To provide a clearer overview, the main differences between conventional LC and Mini-LC should be listed in terms of their applications. While both methods share similar separation principles, they differ in terms of column size, operational scale, solvent use, sensitivity, and practical issues related to instrument design and method development. These differences are important because they affect the effectiveness of the analysis, its environmental impact, and its suitability for routine or specific analyses. Table S1 provides a comparison of the two systems’ main features, highlighting their respective advantages and disadvantages. Mini-LC is much easier to use, and both the instrumentation and the connections are operated in the same way as conventional scale LC systems. This opens up opportunities to apply Mini-LC to novel workflows and applications [47]. Despite the advantages of Mini-LC techniques, some limitations must be acknowledged to provide a balanced perspective. For laboratories that use conventional LC techniques, it may be challenging to switch to miniaturized methods that are incompatible with their current protocols [48]. Although Mini-LC systems utilize less solvent and incur lower operational costs, the initial expense of specialized components such as microfabricated columns, compact pumps and high-precision interfaces may exceed that of conventional LC systems. These small parts can also be more difficult to maintain from a technical point of view [49]. Mini-LC systems often present greater experimental challenges, particularly during the various stages of method development and optimization. Because the columns are smaller and have less dead volume, the system is more sensitive to small changes in sample handling, gradient accuracy, and temperature control. Achieving reliable and reproducible separations with Mini-LC techniques may require a higher level of technical skill [50]. When selecting Mini-LC systems for routine or high-throughput applications, it is essential to consider these practical factors thoroughly. Despite these limitations, however, these systems offer an attractive alternative to conventional LC. Mini-LC systems broaden the scope of LC and open up new frontiers, such as drug testing, cellular structure analysis, and microbiological analysis. These systems not only broaden the scope of LC but also open up new frontiers, such as drug testing, the analysis of cellular structures, and microbiologic analyses [51]. There are several types of Mini-LC system, including Cap-LC, Nano-LC, Chip-LC and portable LC systems. These systems offer an attractive alternative to conventional LC. Recent advances have enabled the development of portable systems and online sample processing platforms, significantly contributing to sample monitoring.

Cap-LC, Nano-LC and Chip-LC are three commonly used techniques of Mini-LC. Each has its own advantages and disadvantages. Cap-LC strikes a good balance between size and performance. It features intermediate column diameters and low flow rates (µL min−1), which make separation more efficient and require less solvent than conventional LC. It is also mechanically stable and reproducible, providing detection limits in the nanogram range. Nano-LC takes miniaturization much further by utilizing narrow-bore columns and flow rates of nL min−1. This makes it highly sensitive down to the picogram level, which is ideal for omics studies and ultra-trace analyses. However, this higher sensitivity can lead to operational issues such as column clogging, flow instability and greater variability in retention time and peak area, making it less suitable for high-throughput analyses. Chip-LC, on the other hand, features a built-in microfabricated chip design that integrates chromatographic channels and injectors into a compact structure. This results in an extremely low dead volume, requires less sample and solvent, and enables use in portable or point-of-care settings. While Chip-LC has many advantages, it is often limited by tolerances in chip manufacturing, reduced process flexibility, shorter channel lengths and significant variability from chip to chip. The lack of standard designs for different brands exacerbates this issue. In summary, Cap-LC prioritizes operational robustness, Nano-LC prioritizes sensitivity at the expense of reproducibility, and Chip-LC prioritizes integration and miniaturization, but struggles with standardization and batch-to-batch consistency.

These techniques differ substantially in terms of their columns, flow rates, sample volumes, separation efficiencies and detection limits. The performance parameters of Cap-LC, Nano-LC and Chip-LC systems are summarized in Table S2.

4.1. Cap-LC

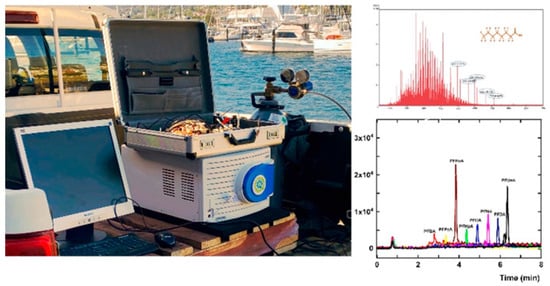

Cap-LC is used to analyze emerging organic contaminants. The main benefit of Cap-LC is that it can separate and analyze compounds at lower concentrations more accurately. This system uses smaller column diameters (e.g., 0.2–1.0 mm) and lower mobile phase volumes. This not only makes the analysis more sensitive, but it also cuts down on waste generation [48,52]. These systems make analyses more efficient and more sensitive to mass by reducing dispersion and using less solvent. This feature is particularly beneficial for analyzing EOCs that contain various organic pollutants [48]. The hyphenation of Cap-LC and mass spectrometry (LC-MS) enables precise detection of organic micro-pollutants, providing high-resolution data that is crucial for environmental monitoring and safety assessments [53]. Cap-LC combined with sensitive detection methods, especially mass spectrometry, has improved detection limits for EOCs, enabling the analysis of trace levels in complex environmental samples. Improvements in micro-flow-controlled techniques also help Cap-LC work faster by making it more sensitive to changes in concentration. Cap-LC provides several unique benefits and is a “greener” technique that uses significantly less mobile phase and is highly flexible and useful in various fields, including EOCs analysis. A portable Cap-LC system were developed to test pharmaceuticals, showing this miniaturized tool could be used in advanced analyses [54]. This flexibility is important for dealing with EOCs that might come from drugs or runoff from farms. Figure 1 shows a field portable Cap-LC/MS system for field based applications [55].

Figure 1.

A robust, portable and miniature battery powered gradient Cap-LC system for pharmaceutical analysis (left panel) and On-site PFAS analysis (right panel). Reproduced with permission [55].

4.2. Nano-LC

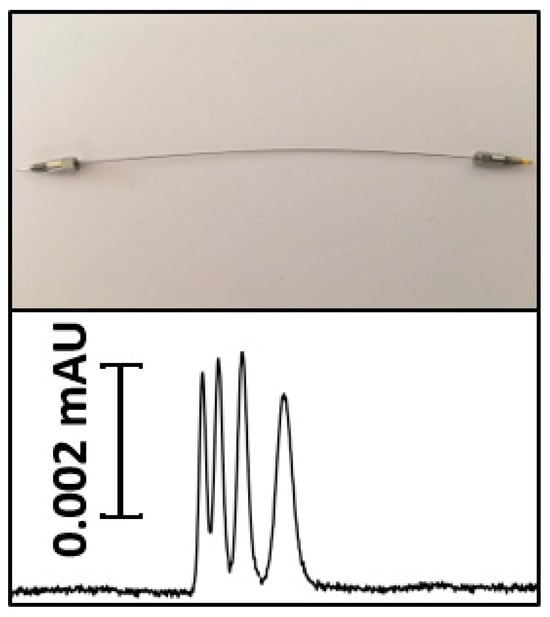

Nano-LC is a very high sensitive technique for the separation and analysis of different compounds in complex matrices [39]. This technique has profoundly impacted the analysis of organic contaminants, especially as regulatory frameworks increasingly prioritize the detection of pollutants at trace levels. Nano-LC (column i.d. 0.2–0.05 mm, flow rates 2–0.1 μL min−1), presents new opportunities to enhance both analytical performance and sustainability [7]. This miniaturization improves chromatographic performance by reducing the inner diameter of the column and flow rates. It also offers substantial environmental and economic benefits, primarily due to a significant reduction in solvent consumption. Several types of column are used in Nano-LC [10]. These columns, including particle packed columns and monolithic columns provide great sensitivity and separation compatibility [12]. The high compatibility of Nano-LC with mass spectrometry significantly amplifies the capabilities of contaminant analysis. This combination promotes high-resolution detection and characterizes the chemical nature of organic contaminants efficiently. Zacs et al. constructed an innovative Nano-LC/MS system for analyzing perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in complex matrices. They also emphasized the importance of overcoming chromatographic peak constraints to improve analytical precision [56]. A new metal tubing confined monolithic nano-column with an internal diameter of 20 µm has been developed for bioanalytical separations in nano-LC. The results in a robust, highly sensitive platform for Nano-LC separations of complex biomolecular samples, offering a promising alternative to existing miniaturized stationary phases in advanced omics applications (see Figure 2) [57]. This encompasses microarray bioassays and MS of components from minute amounts of samples after Nano-LC separation. Nano-LC are used not only for the monitoring of food safety [58,59] but also to monitor the environment, especially to check the quality and safety of water [60]. This adaptation is shown by the selective analysis of different pollutants in water samples. Integrating Nano-LC with advanced materials enhances our ability to detect and remediate complex organic pollutants in various ecosystems.

Figure 2.

A new metal tubing confined monolithic nano-column with an internal diameter of 20 µm [57].

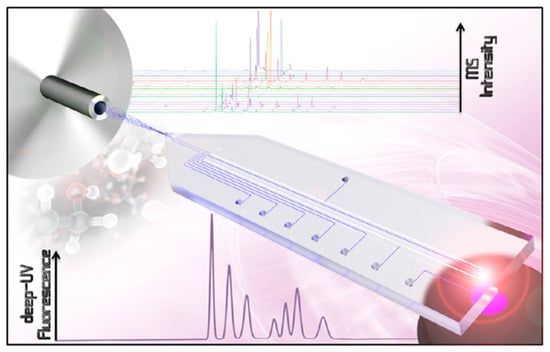

4.3. Chip-Liquid Chromatography

Fast, modular Chip-LC systems are attracting a great deal of attention for on-line analysis, as they reduce overall solvent consumption by over 80% compared to conventional LC [61,62]. The incorporation of Chip-LC in the analysis of EOCs received a significant progression in modern chromatography [63], mainly owing to its compact design, solvent efficiency, and versatility in handling complex sample matrices. Chip-LC uses microfabrication technologies to make small, efficient separation systems that obtain high-resolution results much faster than regular LC [62]. New microfabrication methods have given Chip-LC technology a significant boost by making it possible to create tiny fluidic channels and work with small sample sizes. Chip-LC technology has a wide range of applications, particularly in fields such as environmental and food safety, where precise contaminant detection is essential [64]. One possible application is the use of a modular, chip-based supercritical fluid chromatography system combined with ambient pressure ionization. This method can quickly separate samples, which is important for meeting the requirements of emerging contaminant analysis [65]. Chip-LC operates in a similar way to regular LC but is integrated into microfluidic designs. Its smaller dimensions make it easy to quickly separate and analyze small samples without compromising sensitivity or resolution. Each design has its own flow characteristics and efficiencies [66]. Figure 3 illustrates a novel, two-dimensional, chip-based-HPLC (2D-chip-HPLC) approach. This method facilitates multiple transfers from the effluent of the first dimension onto the column head of the second separation dimension. This approach is particularly valuable for studying EOCs, as obtaining samples can be challenging due to environmental concerns, as it enables working with small sample volumes. Recent advancements include the integration of Chip-LC with sophisticated detection techniques, such as mass spectrometry and ion mobility spectrometry. For instance, the combination of 2D-chip-HPLC and ion mobility spectrometry (IMS) has revealed significant differences in the separation mechanisms, facilitating the identification and measurement of complex mixtures of contaminants [67]. This combination allows analysts to distinguish compounds based on their size, shape and charge, significantly enhancing the depth of analysis of intricate environmental samples contaminated with various organic pollutants. Furthermore, combining high-resolution mass spectrometry with Chip-LC makes it possible to perform non-targeted analyses, which are crucial for identifying EOCs in complex biological matrices. The combination of Chip-LC and mass spectrometry is increasingly recognized as an effective way of improving the specificity and sensitivity of detection methods. For the structural design and assembly of a polymeric microfluidic chip intended for Chip-LC applications.

Figure 3.

A two-dimensional chip for multiple transfers from the first-dimension effluent onto the column head of the second separation dimension. Reproduced with permission [66].

5. Recent Applications of EOCs in Food and Environmental Samples

There has been an increased awareness towards the use of Mini-LC techniques for the analysis of EOCs for the evaluation of different food samples. Traditional analytical techniques are not suitable for determining food contaminants because they are destructive and time-consuming [68]. Therefore, this section discusses recent and selected analyses of food contaminants by Mini-LC. Readers are also referred to the following review articles [6,7,15,24,63,69,70,71], which include some earlier applications. Table 1 shows the results of all contaminant analyses performed using Mini-LC, alongside several instrumental parameters.

Table 1.

EOC analyses performed using Mini-LC techniques, alongside some instrumental parameters.

The assurance of food safety is a paramount global concern, necessitating highly sensitive and selective analytical methods to monitor a wide array of chemical contaminants. These substances, which include mycotoxins, pesticide residues, veterinary drugs, and environmental pollutants, can be present at trace levels in complex food matrices, posing significant risks to human health. The application of Mini-LC, particularly Nano-LC, has proven highly effective for the sensitive determination of various food contaminants [5], including mycotoxins, veterinary drug residues, and pesticides. The ability to achieve low ngL−1 or even pgL−1 detection limits is crucial for ensuring food safety, as many of these contaminants are toxic even at trace levels. Recent studies have demonstrated that Mini-LC methods can achieve sensitivity levels consistent with international standards (e.g., EU MRLs, US EPA and WHO guidelines) for contaminants such as PFAS, pesticide residues and pharmaceuticals, thereby aligning with regulatory practices. Capillary and microchip LC systems, for example, have successfully quantified pesticide residues at concentrations below EU Maximum Residue Limits (MRLs) and PFAS compounds within U.S. EPA advisory levels. These results confirm that Mini-LC platforms can meet current regulatory expectations for EOC detection and support harmonized monitoring approaches across different jurisdictions.

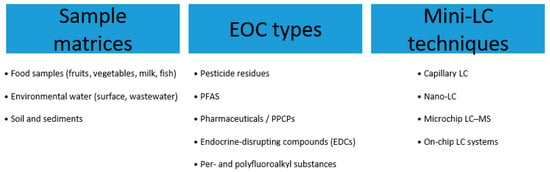

Mini-LC, particularly when coupled with MS, has emerged as a powerful technique in this field. Its exceptional sensitivity, low solvent consumption, and ability to handle complex samples make it ideally suited for the detection and quantification of food contaminants at concentrations often mandated by stringent regulatory limits. Figure 4 summarizes the Mini-LC techniques for the analysis of environmental and food samples for EOCs. With regard to miniaturized-LC-based analyses of food contaminants, emphasis has been placed on articles published since 2022, as previous review articles have focused on earlier periods [5,6,7,24,71]. This section therefore details recent advances and applications of Mini-LC for analyzing key classes of food and environmental EOCs, primarily from early-2022 to mid-2025.

Figure 4.

The Mini-LC techniques for the analysis of environmental and food samples for EOCs.

5.1. Pesticide Residues

The monitoring of pesticide residues is crucial for assessing compliance with Maximum Residue Levels (MRLs). The trend towards multi-residue methods (MRMs), which aim to analyze hundreds of compounds in a single run, demands high chromatographic resolution. The use of low flowrate not only increases ionization efficiency and minimizes ionization suppression but also boost sensitivity compared to analytical-scale LC–MS methods [58]. Microflow-LC has experienced rapid growth, driven by the emergence of mass spectrometry applications that meet the need for analyzing small volumes of precious samples with ever-higher sensitivity [72]. Cap-LC with column internal diameters of 0.2 to 0.5 mm offers a robust compromise between sensitivity and throughput. The use of long columns packed with sub-2-µm or core–shell particles provides the high peak capacity needed to separate complex mixtures of pesticides and their metabolites. This is especially important for distinguishing between isomeric compounds that co-elute in conventional HPLC. Various column types with different IDs were used to analyze pesticides in given samples [58,73,74,75]. Mini-LC is particularly valuable for analyzing new pesticides with complex compositions. For example, the analysis of short-chain chlorinated paraffins (SCCPs), which consist of thousands of congeners, is nearly impossible with traditional-LC without severe chromatographic interference [76]. The superior efficiency of narrow bore columns, especially when coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS), enables a more detailed congener-specific separation, leading to more accurate quantification. The drastic reduction in organic solvent consumption (often >95% compared to HPLC) aligns with the principles of green chemistry, making Mini-LC an environmentally friendly choice for routine pesticide monitoring laboratories. Various advanced Mini-LC techniques, such as the two-dimensional LC method, were used for pesticide detection in corn products [77]. These techniques are powerful and ‘greener’ alternatives to conventional methods.

5.2. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)

PFAS are a diverse group of synthetic chemicals that have been widely used for over 60 years due to their unique properties. They are persistent EOCs that pose significant health risks through dietary exposure [78]. Despite their widespread use, concerns about the environmental and health impacts of these substances have only recently emerged. These compounds have been detected in several foods, including fish and shellfish, as well as animal-origin foods such as livestock, poultry products and milk. They have also been found in plant-based foods [79]. A Nano-LC/HRMS system, an efficient Mini-LC technique for the analysis of PFAS, was used to analyze PFAS in food products ranging from 0.001 to 0.3 ng g−1 [56] and aqueous film-forming foams (AFFFs) and municipal wastewater samples ranging from 0.05 to 0.4 µg g−1 [80]. These results are promising for the determination of EOCs with low content in the samples. A sensitive method based on Cap-LC/UV was developed to assess the presence and dissipation of herbicides with a wide range of polarities in soil, using in-tube solid-phase microextraction (IT-SPME) [81]. This study used tritosulfuron (TRT), triflusulfuron-methyl (TRF), aclonifen (ACL) and bifenox (BF) as probe compounds. Suitable linearity was achieved at concentration levels of 0.5–4.0 µg g−1 for TRT and TRF, and 0.2–1.0 µg g−1 for ACL and BF. Intra- and interday precision (expressed as relative standard deviation) was ≤4% and ≤8%, respectively. The limits of detection (LODs) and quantification (LOQs) were in the ranges 0.05–0.1 µg g−1 and 0.1–0.4 µg g−1, respectively.

5.3. Herbicides

Herbicides (HBs) are chemicals used to kill or inhibit the growth of unwanted plants and weeds. The intensive use of HBs in modern agriculture continues to pose a significant threat to the environment. After application, HBs can disperse to different environmental compartments, such as soil, groundwater or surface water, through various processes. Consequently, many countries have established maximum residue limits (MRLs), specifying limits of no more than 0.1 µg L−1 for individual herbicides and 0.5 µg L−1 for the cumulative concentration of all herbicides [82]. Therefore, the use of high-sensitivity separation techniques has become a key issue for preventing and controlling HBs. These contaminants were determined using a microfluidic Chip-LC system with 0.0099–0.1388 mmol L−1 of the LODs values [82]. Five triazine herbicides were detected in environmental waters using a graphene oxide-ionic liquid-based solid-phase microextraction (SBSE) system coupled to a Cap-LC-MS/MS system, with LOD values ranging from 0.0005 to 0.15 ng mL−1 [83]. In addition, the degradation of HBs [84], bifenox and aclonifen, in water was studied using a C18 (150 mm × 0.5 mm ID, 5 µm) column in a Cap-LC/DAD system. This allowed LOD values of 10, 35 and 1550 ng L−1 to be obtained for aclonifen (ACL), bifenox (BF) and bifenox acid (BFA), respectively [85].

5.4. Veterinary Drug Contaminants

Veterinary drugs, including antibiotics, anthelmintics, and growth promoters, can leave residues in animal-derived products like meat, milk, eggs, and honey. The low flow rates of Mini-LC significantly enhance ionization efficiency in electrospray MS sources, leading to improved signal-to-noise ratios. This high sensitivity is crucial for detecting antibiotic residues such as sulfonamides, tetracyclines, and fluoroquinolones at levels below their respective MRLs [5]. Chloramphenicol (CAP) is an effective broad-spectrum antibiotic against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. This was determined using ProFlow Nano-LC/UV with a graphene oxide-functionalized monolithic nano-column, with an LOD of 0.02 µgkg−1 [86]. Nano-LC/UV with particle packed column was also used to separate chiral drug contaminants in water samples [87]. This study examined the enantioseparation of ten chiral drugs on CSP-amylose tris(3-chloro-5-methyphenylcarbamate), which was suitable for the coupling of MS detection by dedicated nano-spray interfaces.

5.5. Toxins

Marine biotoxins are chemical contaminants that are produced naturally by certain types of algae and other microorganisms, such as bacteria. Ciguatera (CFP) poisoning from eating contaminated fish is the most common type of food poisoning caused by marine biotoxins worldwide, with an estimated 20,000–50,000 cases occurring each year. Cap-LC/HRMS was used to analyze CFP toxins in fish samples, confirming C-CTX1 as the main ciguatoxin present [88,89].

Mycotoxins, toxic secondary metabolites produced by fungi, are among the most pervasive and hazardous food contaminants due to their carcinogenic, teratogenic, and immunosuppressive effects. Their analysis is challenging because of their low abundance in complex matrices like grains, nuts, and spices. The high mass sensitivity of Cap-/Nano-LC [90] and chip-based LC systems [64] is a critical advantage for mycotoxin analysis. For instance, aflatoxins (e.g., Aflatoxin B1, a potent carcinogen) have been successfully determined in nuts and cereals using microfluidic Nano-LC-MS systems [64]. These integrated platforms achieve detection limits as low as 1 ng L−1 (ppt), which is essential for compliance with regulatory standards that are often set in the low µg kg−1 (ppb) range. The integration of sample preparation and separation on a single chip minimizes sample handling and reduces analyte loss, leading to superior reproducibility. The trap-column approach is frequently employed. A large volume of a purified food extract can be loaded onto a trap column, concentrating the target mycotoxins and allowing for further matrix clean-up online before elution to the analytical column [91]. This is particularly useful for multi-mycotoxin methods targeting groups like aflatoxins, ochratoxin A, and fumonisins simultaneously.

5.6. Secondary Metabolite Contaminants

Pyrrolizidine alkaloids (PAs) are chemical compounds naturally produced by some plants and are known for their toxic effects. They can be particularly damaging to the liver, and some are carcinogenic. The advantages of the developed Mini-LC/MS methods include increased sensitivity compared to conventional flow LC-MS. These systems are promising for the sensitive detection of PAs in samples [92].

Garcinia mangostana L. is widely recognized for its traditional medicinal uses, as well as its growing relevance in the nutraceutical sector. The cytotoxic effects of an alcoholic extract of Garcinia mangostana L. were investigated using Cap-LC-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS [93]. This approach provided a better understanding of the cytotoxic potential of the extract against leukemic cells and emphasized its selectivity for cancer cells. Cap-LC system was also applied for non-psychoactive cannabinoids identification [94]. This study also included an AGREE analysis to determine the presence of 24 cannabinoids in hemp inflorescence extracts, in accordance with the requirements of Green Analytical Chemistry standards and using an eco-sustainable analytical method (see Figure 5) [95]. The most widely accepted of these metrics is AGREE, which was used to obtain a final score of 0.71 out of 1.00 using the Mini-LC methodology. This shows that Mini-LC is a promising green analytical methodology. It was also reported that the presence of certain plant contaminants is crucial for metabolic syndrome, as determined using a Nano-LC/HRMS system [96].

Figure 5.

Results of AGREE analysis for the Nano-LC method for Simultaneous Analysis of L-Carnitine and Acetyl-L-Carnitine in food samples. Reproduced with permission [95].

5.7. Other Contaminants

Mini-LC also finds applications in monitoring other process-derived contaminants [97,98]. Certain PAHs, like benzo[a]pyrene, are genotoxic and can form in food during grilling or smoking [99]. Mini-LC provides the necessary sensitivity for the determination of relevant compounds in the samples [97,100,101]. When coupled with MS, it allows for the confident identification and quantification of a broader range of PAHs in complex food matrices like oils and smoked meats. A combination of weir-based blockage and single-particle frit was employed to separate PAHs by passing nano-sized silica particles through a miniaturized glass microchip channel [102]. PAHs were also separated using monolithic columns incorporating carbon dots by RP/Cap-LC [103]. Contaminants such as acrylamide or furan, which form during thermal processing of food, can also be analyzed using Mini-LC-MS/MS. The high sensitivity required for these small, polar molecules in starchy foods like potato chips or coffee is effectively achieved with Cap-LC or Nano-LC systems.

6. Technical Challenges and Prospects of Mini-LC

Mini-LC faces some technical challenges that prevent its regular use. A significant issue is matrix interference: the narrow-bore columns and low-volume injection routes are easily affected by proteins, lipids, humic substances and salts, which can contaminate the system or hinder MS detection. Even with trap-and-elute setups, highly complex samples often require extensive pretreatment to ensure consistent performance. The stability of instruments poses another challenge. Working with nano- and micro- flow rates requires precise pump, valve, and temperature regulation, as minor variations can significantly affect retention time and peak shape. The restricted loading capacity of Mini-LC columns adds to the complexity of analysis as they are more prone to overload and can degrade rapidly when subjected to concentrated or inadequately purified extracts. Furthermore, the lack of uniformity in column formats, interfaces and operating protocols across manufacturers complicates method transfer and extensive method validation. Despite these difficulties, the outlook for Mini-LC remains positive. Progress in microfluidics, enhanced low-flow pump technologies, and stronger trapping and extraction materials continually improves system reliability and user-friendliness. Enhanced standardization and integration of sample preparation with Mini-LC, especially in narrow-column and chip-based platforms, is expected to improve accessibility and facilitate the wider use of regular monitoring of emerging contaminants.

7. Conclusions

Mini-LC has firmly established itself as one of the most powerful and sustainable analytical approaches for determining emerging organic contaminants (EOCs) in food and environmental samples. Continued miniaturization of chromatographic systems encompassing capillary-, nano- and chip-LC configurations—has substantially improved separation efficiency, sensitivity and eco-efficiency by minimizing solvent use and adopting a compact design. Coupling these systems with high-resolution mass spectrometry enables the reliable detection of EOCs at trace and ultra-trace levels across complex matrices, thereby advancing both food safety and environmental monitoring. Nevertheless, several technical and methodological challenges remain. These include issues related to column standardization, matrix effects, reduced injection capacities and the robustness of low-flow systems. Addressing these issues is essential to facilitate broader routine applications. Progress in microfabrication, robust low-volume pumps and intelligent fluid handling is expected to further improve method reproducibility and portability.

Looking to the future, the emergence of miniaturized two-dimensional liquid chromatography (2D-LC) offers a promising way to enhance peak capacity and multidimensional separation in micro- and nanoscale formats. The development of lab-on-chip mini-LC devices with fully integrated sample preparation, separation and detection modules could transform on-site monitoring by providing a scalable platform for real-time environmental diagnostics and rapid food contamination screening. Furthermore, integration with artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning algorithms will facilitate the automated optimization of chromatographic parameters, intelligent peak deconvolution and predictive data analytics. This will lead to faster method development and more accurate contaminant classification. In summary, the convergence of advanced materials, microfluidic engineering and AI-based data processing will define the next generation of Mini-LC systems. It is anticipated that these future developments will transform Mini-LC from a specialized research tool into a standardized, autonomous and field-deployable technology for comprehensive EOC monitoring and sustainable analytical practice.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/molecules31010068/s1, Table S1: Comparison of miniaturized sample preparation techniques for Mini-LC analysis of EOCs; Table S2: The key features are compared in terms of the advantages and disadvantages of conventional LC and Mini-LC systems; Table S3: Performance Parameters of Cap-LC, Nano-LC, and Chip-LC Systems.

Author Contributions

C.A.: writing—original draft preparation; writing—review and editing; funding acquisition; supervision; A.A.: writing—original draft preparation; writing—review and editing; M.A.: writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing; B.S.: writing—review and editing; Z.E.R.: writing—review and editing; supervision; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aydoğan, C.; Rigano, F.; Krčmová, L.K.; Chung, D.S.; Macka, M.; Mondello, L. Miniaturized LC in Molecular Omics. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 11485–11497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zietek, B.M.; Mladic, M.; Bruyneel, B.; Niessen, W.M.A.; Honing, M.; Somsen, G.W.; Kool, J. Nanofractionation Platform with Parallel Mass Spectrometry for Identification of CYP1A2 Inhibitors in Metabolic Mixtures. SLAS Discov. 2018, 23, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yates, J.R. The Revolution and Evolution of Shotgun Proteomics for Large-Scale Proteome Analysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 1629–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydoğan, C. New Advances in Nano-Liquid Chromatography for Proteomics Analysis. In Advances in Chromatography; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; ISBN 978-1-003-50056-8. [Google Scholar]

- Fedorenko, D.; Bartkevics, V. Recent Applications of Nano-Liquid Chromatography in Food Safety and Environmental Monitoring: A Review. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2021, 53, 98–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydoğan, C. Nanoscale Separations Based on LC and CE for Food Analysis: A Review. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 121, 115693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydoğan, C.; Beltekin, B.; Aslan, H.; Yılmaz, F.; Göktürk, I.; Denizli, A.; El-Rassi, Z. Nanoscale Separations: Recent Achievements. J. Chromatogr. Open 2022, 2, 100066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uniformly 15N-Labeled Recombinant Ricin A-Chain as an Internal Retention Time Standard for Increased Confidence in Forensic Identification of Ricin by Untargeted Nanoflow Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Analytical Chemistry. Available online: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.analchem.9b03389 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Zietek, B.M.; Still, K.B.M.; Jaschusch, K.; Bruyneel, B.; Ariese, F.; Brouwer, T.J.F.; Luger, M.; Limburg, R.J.; Rosier, J.C.; Iperen, D.J.v.; et al. Bioactivity Profiling of Small-Volume Samples by Nano Liquid Chromatography Coupled to Microarray Bioassaying Using High-Resolution Fractionation. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 10458–10466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, S.R.; Olsen, C.; Lundanes, E. Nano Liquid Chromatography Columns. Analyst 2019, 144, 7090–7104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.C.; Rodriguez, E.S.; Haddad, P.R.; Paull, B. Recent Advances in Open Tubular Capillary Liquid Chromatography. Analyst 2019, 144, 3464–3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydoğan, C.; Günyel, Z.; Ali, A.; Göktürk, I.; Yılmaz, F.; Denizli, A. Recent Advances and Applications of Miniaturized Analytical- and on-Line Sample Preparation- Columns. J. Chromatogr. Open 2025, 8, 100247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svec, F.; Lv, Y. Advances and Recent Trends in the Field of Monolithic Columns for Chromatography. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 250–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Huang, Y.; Cao, H.; Mei, X.; Feng, T.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, B. A Complementary Type of Zero Dead Volume Connection for Capillary Column Liquid Chromatography. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 10149–10154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Bautista, S.; Molins-Legua, C.; Campíns-Falcó, P. Miniaturized Liquid Chromatography in Environmental Analysis. A Review. J. Chromatogr. A 2024, 1730, 465101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUR-Lex. Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000 Establishing a Framework for Community Action in the Field of Water Policy; EUR-Lex: Brussels, Belgium, 2000; Volume 327. [Google Scholar]

- EUR-Lex. Directive—2009/128—EN. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2009/128/oj/eng (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions REPowerEU Plan; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2022.

- EUR-Lex. Directive—2008/105—EN. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2008/105/oj/eng (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Cruz, J.C.; Souza, I.D.D.; Lanças, F.M.; Queiroz, M.E.C. Current Advances and Applications of Online Sample Preparation Techniques for Miniaturized Liquid Chromatography Systems. J. Chromatogr. A 2022, 1668, 462925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szumski, M.; Buszewski, B. State of the Art in Miniaturized Separation Techniques. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2002, 32, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, F.; Wang, H.-S.; Menon, S. Food Safety in the 21st Century. Biomed. J. 2018, 41, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campo, J.; Picó, Y. 17—Emerging Contaminants and Toxins. In Chemical Analysis of Food, 2nd ed.; Pico, Y., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 729–758. ISBN 978-0-12-813266-1. [Google Scholar]

- Pena-Pereira, F.; Bendicho, C.; Pavlović, D.M.; Martín-Esteban, A.; Díaz-Álvarez, M.; Pan, Y.; Cooper, J.; Yang, Z.; Safarik, I.; Pospiskova, K.; et al. Miniaturized Analytical Methods for Determination of Environmental Contaminants of Emerging Concern—A Review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2021, 1158, 238108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugudamani, I.; Oke, S.A.; Gumede, T.P.; Senbore, S. Herbicides in Water Sources: Communicating Potential Risks to the Population of Mangaung Metropolitan Municipality, South Africa. Toxics 2023, 11, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, H.; Ding, Y.; Bai, S. Emerging Organic Contaminant Removal in Constructed Wetlands; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 451–454. [Google Scholar]

- Viotti, P.V.; Moreira, W.M.; Straioto, H.; Bergamasco, R.; Scaliante, M.H.N.O.; Vieira, M.F. The ‘Chimie Douce’ Process towards the Modification of Natural Zeolites for Removing Drugs and Pesticides from Water. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2022, 97, 2149–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Narvaez, O.M.; Peralta-Hernandez, J.M.; Goonetilleke, A.; Bandala, E.R. Treatment Technologies for Emerging Contaminants in Water: A Review. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 323, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yan, X.; Zhou, X.; Peng, P.; Sun, Q.; Zhao, F. Advances in the On-Line Solid-Phase Extraction-Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Analysis of Emerging Organic Contaminants. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 160, 116976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Bautista, S.; Navarro-Utiel, R.; Ballester-Caudet, A.; Campíns-Falcó, P. Towards in Field Miniaturized Liquid Chromatography: Biocides in Wastewater as a Proof of Concept. J. Chromatogr. A 2022, 1673, 463119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas Medina, D.A.; Lanças, F.M. What Still Hinders the Routine Application of Miniaturized Liquid Chromatography beyond the Omics Sciences? J. Chromatogr. Open 2024, 6, 100149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas Medina, D.A.; Cardoso, A.T.; Maciel, E.V.S.; Lanças, F.M. Current Materials for Miniaturized Sample Preparation: Recent Advances and Future Trends. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 165, 117120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, N.; Khorram, P.; Duman, O.; Sibel, T.; Hassan, S. Overview of Nanosorbents Used in Solid Phase Extraction Techniques for the Monitoring of Emerging Organic Contaminants in Water and Wastewater Samples. Trends Environ. Anal. Chem. 2020, 25, e00081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar Mogaddam, M.R.; Beiramzadeh, S.; Nazari Koloujeh, M.; Changizi Kecheklou, A.; Daghi, M.M.; Farajzadeh, M.A.; Tuzen, M. Chapter 4—Sorbent-Based Extraction Procedures. In Green Analytical Chemistry; Locatelli, M., Kaya, S., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 59–117. ISBN 978-0-443-16122-3. [Google Scholar]

- Orazbayeva, D.; Koziel, J.A.; Trujillo-Rodríguez, M.J.; Anderson, J.L.; Kenessov, B. Polymeric Ionic Liquid Sorbent Coatings in Headspace Solid-Phase Microextraction: A Green Sample Preparation Technique for the Determination of Pesticides in Soil. Microchem. J. 2020, 157, 104996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreasidou, E.; Martello, L.; Heath, D.; Bikiaris, D.N.; Lambropoulou, D.A.; Heath, E. Synthesis and Evaluation of a New Acrylic Copolymer for Dispersive Solid-Phase Microextraction of Organic Contaminants from Urban Wastewater. Microchem. J. 2025, 210, 113038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Liste, A.; Espín-Moreno, L.; Schweiss, M.O.; Papay-Ramírez, L.; Mustieles, V.; Rodríguez-Carrillo, A.; Vela-Soria, F.; Ballesteros, O. Simultaneous Identification of Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals in Semen Using a Miniaturized Salt-Assisted Liquid-Liquid Extraction Procedure Followed by LC-MS/MS Analysis. Microchem. J. 2025, 218, 115243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.N.; Baduel, C. Optimization and Validation of an Extraction Method for the Analysis of Multi-Class Emerging Contaminants in Soil and Sediment. J. Chromatogr. A 2023, 1710, 464287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberg-Larsen, H.; Wilson, S.R.; Lundanes, E. Recent Advances in On-Line Upfront Devices for Sensitive Bioanalytical Nano LC Methods. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2021, 136, 116190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplitz, A.S.; Kresge, G.A.; Selover, B.; Horvat, L.; Franklin, E.G.; Godinho, J.M.; Grinias, K.M.; Foster, S.W.; Davis, J.J.; Grinias, J.P. High-Throughput and Ultrafast Liquid Chromatography. Anal. Chem. 2019, 92, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydoğan, C.; Alharthi, S. Nano-LC with New Hydrophobic Monolith Based on 9-Antracenylmethyl Methacrylate for Biomolecule Separation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilpinen, K.; Tisler, S.; Jørgensen, M.B.; Mortensen, P.; Christensen, J.H. Temporal Trends and Sources of Organic Micropollutants in Wastewater. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 957, 177555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhamid, M.A.A.; Ki, M.-R.; Yoon, H.J.; Pack, S.P. Microfluidic Sensors for Micropollutant Detection in Environmental Matrices: Recent Advances and Prospects. Biosensors 2025, 15, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira dos Santos, N.G.; Maciel, E.V.S.; Vargas Medina, D.A.; Lanças, F.M. NanoLC-EI-MS: Perspectives in Biochemical Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzoni, M.; Rusconi, M.; Valsecchi, S.; Martins, C.P.B.; Polesello, S. An On-Line Solid Phase Extraction-Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry Method for the Determination of Perfluoroalkyl Acids in Drinking and Surface Waters. J. Anal. Methods Chem. 2015, 2015, 942016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Qin, M.; Zheng, T.; Wu, G. Hybrid Monolithic Column In-Tube Solid-Phase Microextraction for Pretreatment of Synthetic Cannabinoids Prior to Determination by UPLC-QTRAP MS/MS. Microchem. J. 2025, 215, 114396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggleston-Rangel, R. Why Use Miniaturized Columns in Liquid Chromatography? Benefits and Challenges. LCGC International. Available online: https://www.chromatographyonline.com/view/why-use-miniaturized-columns-in-liquid-chromatography-benefits-and-challenges (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Hanson, E.K.; Foster, S.W.; Piccolo, C.; Grinias, J.P. Considerations for Method Development and Method Translation in Capillary Liquid Chromatography: A Tutorial. J. Chromatogr. Open 2024, 6, 100190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Křížek, T.; Kubíčková, A. Microscale Separation Methods for Enzyme Kinetics Assays. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2012, 403, 2185–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karageorgou, E.G.; Kalogiouri, N.P.; Samanidou, V.F. Green Approaches in High-Performance Liquid Chromatography for Sustainable Food Analysis: Advances, Challenges, and Regulatory Perspectives. Molecules 2025, 30, 3573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrucci, M.; Ali, I.; Mansour, F.R.; Ulusoy, H.I.; Ulusoy, S.; Kabir, A.; Abollino, O.; Giacomino, A.; Inaudi, P.; Locatelli, M.; et al. Chemical Analysis Using Miniaturized and Portable 3D Printed Systems: Where Are We Now? J. Chromatogr. Open 2025, 8, 100241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotny, M.V. Development of Capillary Liquid Chromatography: A Personal Perspective. J. Chromatogr. A 2017, 1523, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, S.R.; Berg, H.E.; Roberg-Larsen, H.; Lundanes, E. Chapter 3.3—Hyphenations of One-Dimensional Capillary Liquid Chromatography with Mass Spectrometry: State-of-the-Art Applications. In Hyphenations of Capillary Chromatography with Mass Spectrometry; Tranchida, P.Q., Mondello, L., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 319–367. ISBN 978-0-12-809638-3. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, S.W.; Xie, X.; Pham, M.; Peaden, P.A.; Patil, L.M.; Tolley, L.T.; Farnsworth, P.B.; Tolley, H.D.; Lee, M.L.; Grinias, J.P. Portable Capillary Liquid Chromatography for Pharmaceutical and Illicit Drug Analysis. J. Sep. Sci. 2020, 43, 1623–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemida, M.; Ghiasvand, A.; Gupta, V.; Coates, L.J.; Gooley, A.A.; Wirth, H.-J.; Haddad, P.R.; Paull, B. Small-Footprint, Field-Deployable LC/MS System for On-Site Analysis of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Soil. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 12032–12040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacs, D.; Fedorenko, D.; Pasecnaja, E.; Bartkevics, V. Application of Nano-LC – Nano-ESI – Orbitrap-MS for Trace Determination of Four Priority PFAS in Food Products Considering Recently Established Tolerable Weekly Intake (TWI) Limits. Anal. Chim. Acta 2023, 1251, 341027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydoğan, C. Recent Advances and Applications in Nano Liquid Chromatography. In Proceedings of the XXI National Chromatography Congress Abstract Book, Didim-Aydın, Türkiye, 14–16 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-González, D.; Pérez-Ortega, P.; Gilbert-López, B.; Molina-Díaz, A.; García-Reyes, J.F.; Fernández-Alba, A.R. Evaluation of Nanoflow Liquid Chromatography High Resolution Mass Spectrometry for Pesticide Residue Analysis in Food. J. Chromatogr. A 2017, 1512, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydoğan, C.; Rassi, Z.E. MWCNT Based Monolith for the Analysis of Antibiotics and Pesticides in Milk and Honey by Integrated Nano-Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Orbitrap Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Methods 2019, 11, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlioz-Barbier, A.; Buleté, A.; Fildier, A.; Garric, J.; Vulliet, E. Non-Targeted Investigation of Benthic Invertebrates (Chironomus riparius) Exposed to Wastewater Treatment Plant Effluents Using Nanoliquid Chromatography Coupled to High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry. Chemosphere 2018, 196, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westphal, H.; Schmidt, S.; Lama, S.; Polack, M.; Weise, C.; Oestereich, T.; Warias, R.; Gulder, T.; Belder, D. Development of an Automated Platform for Monitoring Microfluidic Reactors through Multi-Reactor Integration and Online (Chip-)LC/MS-Detection. React. Chem. Eng. 2024, 9, 1739–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Oleschuk, R.D. Advances in Microchip Liquid Chromatography. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas Medina, D.A.; Maciel, E.V.S.; Lanças, F.M. Miniaturization of Liquid Chromatography Coupled to Mass Spectrometry. 3. Achievements on Chip-Based LC–MS Devices. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2020, 131, 116003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.-Y.; Lin, S.-L.; Chan, S.-A.; Lin, T.-Y.; Fuh, M.-R. Microfluidic Chip-Based Nano-Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry for Quantification of Aflatoxins in Peanut Products. Talanta 2013, 113, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weise, C.; Schirmer, M.; Polack, M.; Korell, A.; Westphal, H.; Schwieger, J.; Warias, R.; Zimmermann, S.; Belder, D. Modular Chip-Based nanoSFC–MS for Ultrafast Separations. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 13888–13896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piendl, S.K.; Geissler, D.; Weigelt, L.; Belder, D. Multiple Heart-Cutting Two-Dimensional Chip-HPLC Combined with Deep-UV Fluorescence and Mass Spectrometric Detection. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 3795–3803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.-C.; Zhang, W.-Z.; Chen, W.-R.; Jair, Y.-C.; Wu, Y.-H.; Liu, Y.-H.; Chen, P.-Z.; Chen, L.-Y.; Chen, P.-S. Engineering an Integrated System with a High Pressure Polymeric Microfluidic Chip Coupled to Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) for the Analysis of Abused Drugs. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2022, 350, 130888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGorrin, R.J. One Hundred Years of Progress in Food Analysis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 18, 8076–8088. Available online: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jf900189s (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Weng, X.; Neethirajan, S. Ensuring Food Safety: Quality Monitoring Using Microfluidics. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 65, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanali, C.; Dugo, L.; Dugo, P.; Mondello, L. Capillary-Liquid Chromatography (CLC) and Nano-LC in Food Analysis. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2013, 52, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía-Carmona, K.; Maciel, E.V.S.; Lanças, F.M. Miniaturized Liquid Chromatography Applied to the Analysis of Residues and Contaminants in Food: A Review. Electrophoresis 2020, 41, 1680–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girel, S.; Meister, I.; Glauser, G.; Rudaz, S. Hyphenation of Microflow Chromatography with Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry for Bioanalytical Applications Focusing on Low Molecular Weight Compounds: A Tutorial Review. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2025, 44, 491–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, S.A.; Whittington, A.; McNally, M.E.P. Demonstration of the Utility of a 1.5mm ID UHPLC Column for Pesticide Analysis Using the Multi-Analyte Method. J. Chromatogr. A 2025, 1756, 466054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesús, F.; Cutillas, V.; Aguilera del Real, A.M.; Fernández-Alba, A.R. Advancements in Multiresidue Pesticide Analysis in Fruits and Vegetables Using Micro-Flow Liquid Chromatography Coupled to Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chim. Acta 2025, 1358, 344100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, N.G.P.; Medina, D.A.V.; Lanças, F.M. Development of Wall-Coated Open Tubular Columns and Their Application to Nano Liquid Chromatography Coupled to Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Molecules 2023, 28, 5103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoura, C.; Larvor, F.; Marchand, P.; Bizec, B.L.; Cariou, R.; Bichon, E. Quantification of Chlorinated Paraffins by Chromatography Coupled to High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry—Part B: Influence of Liquid Chromatography Separation. Chemosphere 2024, 352, 141401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Pozo, L.; Arena, K.; Cacciola, F.; Dugo, P.; Mondello, L. Development and Validation of a Multi-Class Analysis of Pesticides in Corn Products by Comprehensive Two-Dimensional Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2023, 1701, 464064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PFAS National Primary Drinking Water Regulation Rulemaking. Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/03/29/2023-05471/pfas-national-primary-drinking-water-regulation-rulemaking?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Souza, M.C.O.; Domingo, J.L. Levels of per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Foodstuffs: A Review of Dietary Exposure, Health Risks, and Regulatory Challenges. Food Res. Int. 2025, 221, 117494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Wang, Q.; Chen, H.; Li, M. Rapid Quantitative Analysis and Suspect Screening of Per-and Polyfluorinated Alkyl Substances (PFASs) in Aqueous Film-Forming Foams (AFFFs) and Municipal Wastewater Samples by Nano-ESI-HRMS. Water Res. 2022, 219, 118542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Palma, C.E.; Campíns-Falcó, P.; Herráez-Hernández, R. Assessing the Dissipation of Pesticides of Different Polarities in Soil Samples. Soil Syst. 2024, 8, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, D.; Yan, Y.; Yu, Y.; Du, B.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X. Integrating Liquid Chromatography-Electrochemical Detection-Surface Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy on Microfluidic Chip for Phenylurea Herbicides Analysis. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2024, 407, 135436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, A.T.; Lanças, F.M. Determination of Triazine Herbicides in Environmental Waters Using Graphene Oxide-Ionic Liquid-Based SBSE Coupled to Capillary Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Microchem. J. 2025, 215, 114270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra-Mora, P.; Herráez-Hernández, R.; Campíns-Falcó, P. Minimizing the Impact of Sample Preparation on Analytical Results: In-Tube Solid-Phase Microextraction Coupled on-Line to Nano-Liquid Chromatography for the Monitoring of Tribenuron Methyl in Environmental Waters. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 721, 137732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Palma, C.E.; Herráez-Hernández, R.; Campíns-Falcó, P. Study of the Degradation of Diphenyl-Ether Herbicides Aclonifen and Bifenox in Different Environmental Waters. Chemosphere 2023, 336, 139238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, N.; Aydoğan, C. ProFlow Nano-Liquid Chromatography with a Graphene Oxide-Functionalized Monolithic Nano-Column for the Simultaneous Determination of Chloramphenicol and Chloramphenicol Glucuronide in Foods. J. Food Sci. 2022, 87, 1721–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salido-Fortuna, S.; Bosco, C.D.; Gentili, A.; Castro-Puyana, M.; Marina, M.L.; D’Orazio, G.; Fanali, S. Enantiomeric Analysis of Drugs in Water Samples by Using Liquid–Liquid Microextraction and Nano-Liquid Chromatography. Electrophoresis 2023, 44, 1177–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estevez, P.; Oses Prieto, J.; Burlingame, A.; Gago Martinez, A. Characterization of the Ciguatoxin Profile in Fish Samples from the Eastern Atlantic Ocean Using Capillary Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry. Food Chem. 2023, 418, 135960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estevez, P.; Oses-Prieto, J.; Castro, D.; Penin, A.; Burlingame, A.; Gago-Martinez, A. First Detection of Algal Caribbean Ciguatoxin in Amberjack Causing Ciguatera Poisoning in the Canary Islands (Spain). Toxins 2024, 16, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szumski, M.; Grzywiński, D.; Prus, W.; Buszewski, B. Monolithic Molecularly Imprinted Polymeric Capillary Columns for Isolation of Aflatoxins. J. Chromatogr. A 2014, 1364, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Multichannel Open Tubular Enzyme Reactor Online Coupled with Mass Spectrometry for Detecting Ricin. Analytical Chemistry. Available online: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.analchem.7b02590 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Jansons, M.; Fedorenko, D.; Pavlenko, R.; Berzina, Z.; Bartkevics, V. Nanoflow Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry Method for Quantitative Analysis and Target Ion Screening of Pyrrolizidine Alkaloids in Honey, Tea, Herbal Tinctures, and Milk. J. Chromatogr. A 2022, 1676, 463269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeppa, S.D.; Micucci, M.; Ferrini, F.; Gioacchini, A.M.; Piccoli, G.; Potenza, L.; Bartolacci, A.; Annibalini, G.; Rehman, A.A.; Calcabrini, C.; et al. Differential Cytotoxic Effects of Garcinia mangostana Pericarp Extract on Leukaemic versus Normal Human Cell Lines: Insights into Selective Anticancer Activity. J. Herb. Med. 2024, 48, 100937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Tella, R.; Rigano, F.; Guarnaccia, P.; Dugo, P.; Mondello, L. Non-Psychoactive Cannabinoids Identification by Linear Retention Index Approach Applied to a Hand-Portable Capillary Liquid Chromatography Platform. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2022, 414, 6341–6353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydoğan, C.; Ercan, M.; El Rassi, Z. Simultaneous Analysis of L-Carnitine and Acetyl-L-Carnitine in Food Samples by Hydrophilic Interaction Nano-Liquid Chromatography. Methods Protoc. 2025, 8, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Cheong, K.-L.; He, Y.; Liew, A.; Huang, J.; Huang, C.; Zhong, S.; Sathuvan, M. Hylocereus Polyrhizus Pulp Residues Polysaccharide Alleviates High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity by Modulating Intestinal Mucus Secretion and Glycosylation. Foods 2025, 14, 2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto, C.; Herráez-Hernández, R.; Campíns-Falcó, P. Determination of Chlorophylls a and b and β-Carotene in Environmental Waters: Diminishing Wastes and Analysis Time by in-Tube Solid-Phase Microextraction Coupled on-Line to Nano Liquid Chromatography. Adv. Sample Prep. 2023, 8, 100093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana-Mayor, Á.; D’Orazio, G.; Rodríguez-Delgado, M.Á.; Socas-Rodríguez, B. Natural Eutectic Solvent-Based Temperature-Controlled Liquid–Liquid Microextraction and Nano-Liquid Chromatography for the Analysis of Herbal Aqueous Samples. Foods 2025, 14, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydoğan, C. Critical Review of New Advances in Food and Plant Proteomics Analyses by Nano-LC/MS towards Advanced Foodomics. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 176, 117759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhail, I.E.; Lam, S.C.; Coates, L.J.; Rodriguez, E.S.; Gooley, A.; Paull, B. Determination of Haloacetic Acids in Municipal Tap Water and Swimming Pool Water Using Portable Capillary Liquid Chromatography—Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2025, 1751, 465941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Tan, L.; Zhang, M.; Shi, H.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, D.; Zou, J. Rapid Determination of Biogenic Amines in Ossotide Injections by Microfluidic Chip-Mass Spectrometry Platform: Optimization of Microfluidic Chip Derivatization Using Response Surface Methodology. Microchem. J. 2024, 199, 109989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Li, K.; Dou, X.; Li, N.; Wang, X. Nano-Sized Stationary Phase Packings Retained by Single-Particle Frit for Microchip Liquid Chromatography. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2024, 35, 108806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]