Abstract

Azidophenylselenylation (APS) of glycals is a straightforward transformation for preparing phenylseleno 2-azido-2-deoxy derivatives, which are useful blocks in the synthesis of 2-amino-2-deoxy-glycoside-containing oligosaccharides. However, the previously developed APS methods employing the CH2Cl2 as solvent, Ph2Se2-PhI(OAc)2 (commonly known as BAIB), and a source of N3− are still not universal and show limited efficiency for glycals with gluco- and galacto-configurations. To address this limitation, we revisited both heterogeneous (using NaN3) and homogeneous (using TMSN3) APS approaches and optimized the reaction conditions. We found that glycal substrates with galacto- and gluco-configurations require distinct conditions. Galacto-substrates react relatively rapidly, and their conversion depends mainly on efficient azide-ion transfer into the organic phase, which is promoted by nitrile solvents (CH3CN, EtCN). In contrast, for the slower gluco-configured substrates, complete conversion requires a non-polar solvent still capable of azide-ion transfer, such as benzene. These observations were applied to the optimized synthesis of phenylseleno 2-azido-2-deoxy derivatives of d-galactose, d-glucose, l-fucose, l-quinovose, and l-rhamnose.

1. Introduction

1-Azido-2-deoxy derivatives of monosaccharides are widely used as synthetic precursors of 2-amino-2-deoxy-monosaccharides, particularly in the construction of diverse biologically important oligosaccharides containing such units [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. To introduce 2-azido-2-deoxy-glycosyl residues into oligosaccharide chains, several types of glycosyl donors have been employed, starting from 2-azido-2-deoxy-galactosyl bromides whose pioneering synthesis was proposed by Lemieux and Ratcliffe [8]. Other types of glycosyl donors include glycosyl chlorides [9,10,11], imidates [12,13,14], thioglycosides [15,16,17], hemiacetals [18], and selenoglycosides [19,20,21,22].

2-Azido-2-deoxy-derivatives of phenyl 1-selenoglycosides are regarded as promising glycosylation agents [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31], as the PhSe leaving group in glycosylation reactions remains stable under typical protecting-group manipulations used in oligosaccharide synthesis. They can be obtained from glycals via anti-Markovnikov addition to the double bond employing Ph2Se2, NaN3, and bis(acetoxy)iodobenzene (BAIB) in CH2Cl2 [32], with subsequent adaptations of this reaction to glycals by Czernecki [33,34] and Santoyo-González [35], which improved the preparation of 2-azidoselenogalactoside 2 from tri-O-acetyl-d-galactal 1 and 2-azidoselenoglucoside 7 from tri-O-acetyl-d-glucal 6 (Scheme 1).

The synthesis of phenyl 2-azido-2-deoxy-1-selenoglycosides was significantly improved when homogeneous conditions for the azidophenylselenylation (APS) of glycals using the TMSN3-Ph2Se2-BAIB system were established by us [19,36]. However, both variants of the APS reaction, homogeneous and heterogeneous, remain challenging to scale up and show, in some cases, poor reproducibility. For example, galactal 1 (0.1 mmol) treated with APS/NaN3 affords product 2 in 88–90% yield, whereas scaling up to >4 mmol reduces the yield to 53% [19]. In contrast to industrial settings, where hydrodynamics and mass-transfer parameters can be rigorously controlled, laboratory-scale equipment does not allow faithful geometric or mixing similarity upon scale-up. The use of flow conditions [37] for the APS/TMSN3 variant provides reproducibility of the process but requires specialized and non-standard equipment, which seems excessive for the synthesis of such a building block.

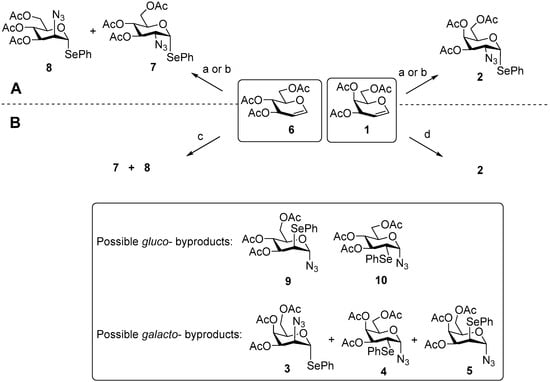

Scheme 1.

Previously described (A) and present (B) APS-protocols for galactal 1 and glucal 6 transformation leading to phenylseleno 2-azido-2-deoxyglycosides 2 and 7, 8 and associated byproducts 3–5 and 9, 10. Reagents and conditions: (a) [19] TMSN3, Ph2Se2, BAIB, CH2Cl2; (b) [38] NaN3, Ph2Se2, BAIB, CH2Cl2; (c) NaN3, Ph2Se2, BAIB, C6H6; d) NaN3, Ph2Se2, BAIB, EtCN.

Another limitation concerns the stereoselectivity of N3 addition at C-2. In the case of substrates bearing an equatorial substituent at C-4, such as glucal or rhamnal, the reaction affords a mixture of products with equatorial (gluco-configuration) and axial (manno-configuration) N3 groups in approximately equal amounts [38]. In contrast, for substrates possessing an axial substituent at C-4, such as galactal and fucal, the ratio is markedly shifted toward the C-2-equatorial product with galacto-configuration.

Despite extensive studies, a clear understanding of how mixing regime and solvent effects govern the outcome of APS reactions remains limited, which complicates the rational optimization of this transformation. The heterogeneous variant remains highly attractive due to the ready availability of all required reagents and its overall simplicity. This inherent limitation of APS in standard batch reactors was a key motivation for our study, prompting us to identify other experimentally accessible and simple factors that could enable reliable preparative-scale synthesis. Specifically, we systematically examined the influence of solvents with different abilities to dissolve NaN3, mass-transfer efficiency, and phase-transfer additives on the outcome of APS of glycals.

The optimized conditions were subsequently applied to the scalable synthesis of the most practically useful phenyl 2-azido-2-deoxy-1-selenoglycosides, including galacto-, fuco- [39], quinovo-, and rhamno-derived building blocks. Particular attention was given to achieving reproducible gram-scale reactions and obtaining the gluco-configured product selectively in the case of glucal substrates.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Reaction Background

The APS reaction is initiated by ligand exchange of an acetate group at the iodine atom in BAIB (11) with N3− (Figure 1A) [36], producing a mixed iodane 12. Subsequent homolytic cleavage of the I-N3 bond in 12 generates an azidyl radical (N3·), which reacts with Ph2Se2, forming phenylselenyl azide (PhSeN3). PhSeN3 is the principal reactive species responsible for the formation of anti-Markovnikov product 15 from the APS-processing of substrate 13 through radical 14. The overall outcome of the reaction is strongly affected by mass-transfer limitations [40], often leading to diverse and sometimes counterintuitive outcomes. Inadequate agitation of solid NaN3 promotes a competing pathway (Figure 1B) [41], giving rise to 2-selenylated radical 16 and subsequently producing acetate 17 [38,42].

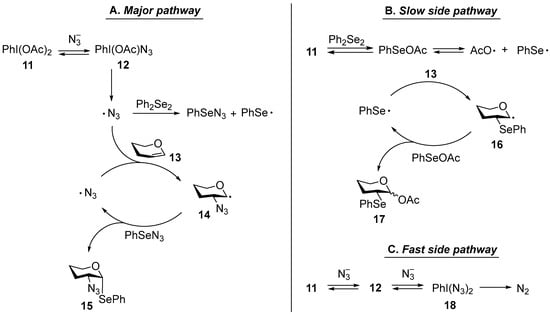

Figure 1.

Critical steps of APS mechanism: (A) pathway leading to desired 2-azido-2-deoxy-1-seleno-glycosides; (B) side pathway resulting in acetyl 2-deoxy-2-seleno-glycosides; (C) side pathway connected with N2 evolution and azide depletion.

Conversely, overly vigorous stirring can disrupt micromixing and foster unproductive radical-radical encounters (e.g., between N3 or bis-azide iodane 18), resulting in N2 evolution and azide depletion and thus reducing the effective azide concentration and preventing complete glycal conversion (by analogy with other mixing-sensitive fast radical reactions [43]) (Figure 1C). Polar solvents, while improving NaN3 solubility, shift the APS reaction toward Markovnikov selectivity and the formation of 2-phenylseleno derivatives. Consequently, the efficiency of APS depends mainly on three interrelated parameters—solvent polarity, mixing intensity, and the presence of silyl additives (TMSCl or TMSOTf), which promote in situ generation of TMSN3 and facilitate phase transfer. To systematically evaluate the impact of these parameters, we first established a set of unified experimental conditions ensuring reproducible mixing and temperature control.

2.2. Evaluation of Reaction Parameters on a Small Scale

To systematically evaluate the influence of reaction parameters, we first examined the APS of tri-O-acetyl-d-galactal 1 [44] as a model reaction under rigorously controlled conditions (Scheme 1). The preparative synthesis of galactal 1 is described in the Supplementary Information. To ensure reproducible mixing, all APS experiments on a small scale (0.14 and 0.42 mmol per 2 mL; see Tables S1, S3 and S4 in Supplementary Information) were conducted under identical conditions: 7 mL glass tubes (inner diameter 12 mm, PTFE-lined screw caps) equipped with identical 9.5 mm × 4.7 mm PTFE-coated stir bars, stirred at 900 rpm, and thermostatted at 15 ± 0.5 °C—the temperature identified as optimal in preliminary trials. Although no strong sensitivity of APS to moisture or atmosphere was detected, reactions were carried out under argon to avoid oxygen capture and potential impact on byproduct pathways under vigorous mixing.

A wide range of heterogeneous APS conditions is reported, with varying NaN3, BAIB, and Ph2Se2 ratios for different substrates. Particular attention should be given to Ph2Se2: while its excess ensures a sufficient concentration of the active azide (PhSeN3) until full conversion of 13, the optimal amount differs between sub-0.25 mmol (0.6 equiv.) and >2 mmol (1.2 equiv.) scales [38]. Large excesses, however, reduce the yield and hinder product crystallization [37]. We therefore first examined the influence of substrate 1 concentration (0.07–0.21 M) and the 1 to Ph2Se2 ratio (0.6–1.2 equiv.) in various solvents to establish a baseline for further optimization (Table S1 in Supplementary Information). These experiments established that, for galactal APS, a concentration of 0.21 M and 0.6 equiv. of Ph2Se2 are optimal, with the addition sequence NaN3—BAIB—Ph2Se2.

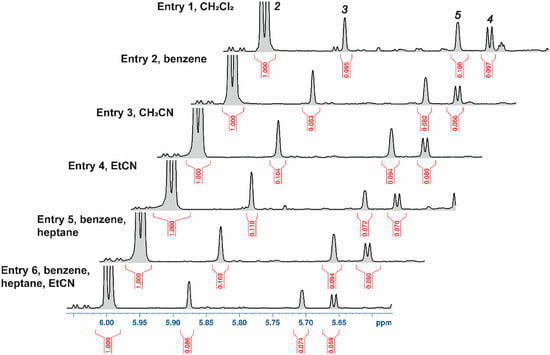

The outcomes of the APS experiments were evaluated by 1H NMR analysis of the crude mixtures in CDCl3, obtained after the reaction mixtures were quenched with aqueous NaHCO3-Na2S2O3, extracted with EtOAc, and concentrated (Figure 2). APS of galactal 1 afforded the target phenyl 2-azido-2-deoxy-1-seleno-D-galactoside 2 together with byproducts 3–5, whose characteristic H-1 signals are shown in Figure 2 (and Figure S1 in Supplementary Information). Talose 3 arises from incomplete stereocontrol, whereas 2-phenylselenoglycosyl azides 4 and 5 originate from the Markovnikov pathway. In addition, a substantial amount of poorly identifiable byproducts was formed. These were evaluated by approximate integration and taken into account when assessing the reaction efficiency (see Figure S1 in the Supplementary Information, where the signals of compounds 2–5 are shown in color and the non-identifiable byproducts in gray). The solvent set included non-polar benzene as well as heptane (to decrease polarity) and nitriles capable of Na+ solvation (thus enhancing NaN3 transfer), namely MeCN and EtCN. The latter combines the CN group’s solvating ability with lower polarity.

Figure 2.

Selected 1H NMR spectral region (δ 5.47–6.06 ppm) of the crude reaction mixtures of tri-acetylgalactal 1 APS (Table 1). The H-1 signals of compounds 2, 3, 5, and 4 are indicated by their respective labels. A more detailed spectrum is provided in the Supplementary Information (Figure S1), where the non-identifiable byproducts are shown in gray.

Ratios of APS products derived from galactal 1 and yields of 2, calculated from the integration of identifiable anomeric signals in the 1H NMR spectra, together with reaction times, are summarized in Table 1. Full conversion of galactal 1 in CH2Cl2 (Entry 1) required four days and furnished an NMR yield of 77%. The reaction generated copious foam, which separated the solid and liquid phases and required periodic manual agitation. Switching to benzene (Entry 2) mitigated foaming and unexpectedly halved the reaction time to two days while increasing the yield to 80%.

Table 1.

The results APS of galactal 1 (Scheme 1) at full conversion: yields of target anti-Markovnikov’s galacto-adduct 2 and its ratios with talo-isomer 3, as well as the ratios of target anti-Markovnikov’s (2, 3) and Markovnikov’s adducts 4 and 5 with galacto- and talo-configurations.

In MeCN, the reaction reached completion within 21 h (Entry 3). Propionitrile (EtCN) delivered the most favorable outcome (Entry 4): full conversion in 15 h, the highest yield of 2-azido-2-deoxy-1-selenogalactose 2, an improved Gal:Tal ratio, and a superior anti-Markovnikov/Markovnikov ratio. The crude mixture produced in EtCN gave a noticeably cleaner 1H-NMR spectrum than those obtained from reactions in CH2Cl2 or benzene and contained fewer non-identifiable byproducts (see the “gray” signals in Figure S1 in the Supplementary Information). The product also crystallized readily during work-up.

In the benzene/heptane (1:1) mixture (Entry 5), the amount of unidentified byproducts was lower than in neat benzene. To combine the desirable features of the individual solvents, a ternary mixture of benzene/EtCN/heptane (1:1:1, Entry 6) was evaluated. This blend and EtCN afforded the highest NMR yield, optimal C-2 stereoselectivity and regioselectivity, minimal Ph2Se2 oxidation products, and excellent crystallizability.

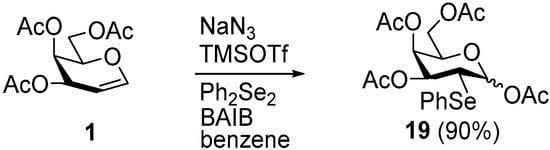

To probe whether catalytic silyl additives could enhance N3− transfer and thereby shorten APS reactions, galactal 1 was subjected to the most effective solvent conditions from Table 1 in the presence of TMSCl or TMSOTf at 3 mol % relative to NaN3 (Table 2). In benzene (Entry 1), TMSOTf diverted the pathway, furnishing 2-phenylseleno-2-deoxy-1-O-acetyl adduct 19 as the major product after two hours (Scheme 2), whereas TMSCl merely slowed conversion and diminished the yield of the target azidoselenide 2 (Entry 2).

Table 2.

The results of APS of galactal 1 in the presence of TMS-additives (3 mol %) (Scheme 1).

Scheme 2.

Formation of 2-phenylseleno-2-deoxy-1-O-acetate 19 during APS of galactal 1 in benzene with a catalytic amount of TMSOTf (Table 2, Entry 1).

This behavior is consistent with two distinct modes of action of TMSOTf depending on the solvent. In EtCN, the higher coordinating ability and polarity favor its role as a phase-transfer promoter for N3−, accelerating its delivery to BAIB and increasing the rate of PhSeN3 formation. In contrast, in benzene. which lacks coordination ability to Na+ TMSOTf, more strongly activates BAIB toward ligand exchange with acetate, thereby favoring the generation of PhSeOAc and PhSe·over N3·. Introducing TMSCl into the benzene/EtCN/heptane (1:1:1) system lengthened the reaction (Entry 4).

We next examined the APS of tri-O-acetyl-glucal 6 [45] in the most promising solvents identified for galactal 1 and monitored both the combined yield of the 2-azido products as well as the diastereomeric ratio of formed gluco- (7) and manno-product (8) (Table 3). The preparative synthesis of glucal 6 is described in Supplementary Information.

Table 3.

Solvent effect on the APS of tri-O-acetyl-glucal 6 and formation of gluco- and manno-product 7 and 8 (Scheme 1) 1.

Unless otherwise noted, reactions were performed at 6 concentration of 0.21 M and with 0.6 equiv. Ph2Se2. In benzene (Entry 1), the substrate was consumed within 48 h, affording an equimolar mixture of phenylseleno 2-azido-2-deoxy-glucoside 7 and -mannoside 8 in good combined yield. Reducing the concentration of 6 to 0.07 M in the same solvent (Entry 2) slowed the reaction left starting material unconsumed, and shifted the diastereomeric ratio to favor the manno-isomer.

A benzene/heptane (1:1) medium (Entry 3) further decreased the rate (conversion remained incomplete after six days), yet, for the first time in the above experiments, the product ratio favored gluco-isomer 7. This indicated that lower-polarity environments may bias stereochemistry toward gluco-product formation. In MeCN (Entry 4) and EtCN (Entry 5), the reaction was again sluggish, and the product mixture showed a slight excess of manno-isomer 8.

Overall, solvent polarity and substrate concentration exert competing effects on both reaction rate and diastereocontrol: neat benzene provides the only case of full conversion, whereas mixed aromatic-aliphatic media offer a potential handle for enhancing gluco-selectivity that merits further optimization.

2.3. Scaling-Up Experiments

The optimized APS conditions were adopted for the preparative synthesis of phenylseleno 2-azido-2-deoxy-galactoside 2 and -glucoside 7. Taking into account the results from Table 1 and Table 3, EtCN was selected for APS of galactal 1, while benzene for glucal 6.

To ensure homogeneous distribution of the reagents, which is difficult to control upon laboratory scale-up, the NaN3-containing mixture was thoroughly homogenized by stirring and sonication, after which BAIB and Ph2Se2 were added in small portions over about 10 min each. During scale-up, we maintained geometric similarity of the reaction vessels, including the ratio of the stir bar size to the diameter of the reaction mixture. Furthermore, we found that the most reproducible results were obtained when the vessel was chosen such that the ratio of the reaction mixture’s diameter to its height was close to 1:1. Under these conditions, APS of galactal 1 on a 1.1 g (4+ mmol) and further scaling was successful. However, when the reaction was run in a standard 250 mL round-bottom flask with a 2 g charge, it remained incomplete, with about 20% of galactal 1 unreacted. Scaling glucal 6 APS revealed another limitation: in benzene, suspending NaN3 uniformly throughout the volume became difficult at glucal loads above 1.5 g, suggesting that this may be the practical upper limit of this protocol.

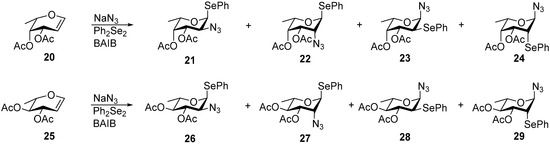

The conditions that proved effective in APS of galactal and glucal at higher loadings were next applied to fucal 20 [46] and rhamnal 25 [47] (Scheme 3, preparative synthesis of 20 and 25 is described in Supplementary information). Solvent choice was guided by analogy: for fucal, whose configuration closely resembles that of galactal, APS was examined in MeCN and EtCN (Table 4, Entries 1 and 2). For rhamnal, on the other hand, the glucal precedent was followed, and APS was evaluated in benzene (Table 4, Entry 3).

Scheme 3.

APS of fucal 20 and rhamnal 25 leading to phenyl 2-azido-2-deoxy-1-selenoglycosides 21 and 26, as well as associated byproducts 22–24, and 28–29.

Table 4.

Results of the APS of fucal 20 and rhamnal 25 (Scheme 3): yields of product mixtures 21–24 (Entries 1, 2) and 26–29 (Entry 3), and the ratios of the corresponding 2-azido-stereoisomers: fuco- and talo-adducts 21 and 22 (Entries 1–2), quino- and rhamno-adducts 26 and 27 (Entry 3), as well as the ratios of anti-Markovnikov (21 + 22) and (26 + 27) to the corresponding Markovnikov adducts (23 + 24) and (28 + 29) adducts.

APS of fucal 20 (0.5 mmol) in EtCN afforded a combined yield of 65% for the product mixture (Table 4, Entry 1), which included phenylseleno 2-azido-2-deoxyfucoside 21 (58%), accompanied by minor products: phenylseleno 2-azido-2,6-dideoxy-l-taloside 22 (4%), as well as 2-phenylseleno-2,6-dideoxy-l-talosylazide 24, (2%) and its fuco-isomer 23 (1%). These values were calculated from NMR spectra by using the above-described approach after partial separation of the mixture by column chromatography.

When the reaction was conducted in MeCN on a 2.5 mmol scale, the combined yield of the mixture increased to 91%, and the yield of 2-azidofucoside 21 improved markedly to 79%, albeit with a slight decrease in stereoselectivity (Table 4, Entry 2). Although at this stage, pure product 21 could not be isolated, it is known that Zemplén O-deacetylation allows further separation of phenyl 2-azido-2-deoxy-1-phenylseleno-α-l-fucoside by simple crystallization [30].

APS of rhamnal 25 was first carried out using 0.6 equiv of Ph2Se2, corresponding to the optimized loading established for other glycals in the general APS protocol. Under these conditions, the reaction proceeded slowly, and the conversion remained modest. Increasing the amount of Ph2Se2 to 1.2 equiv (Table 4, Entry 3) led to marginal improvement: after 40 h, the conversion reached 79%, affording the mixture of 26–29 in 49% isolated yield. NMR analysis of the purified mixture (after removal of the starting material) confirmed the formation of 26% of 2-azidoquinovoside 26, 19% of 2-azidorhamnoside 27, and a total of 4% of the phenylseleno byproducts 28 and 29.

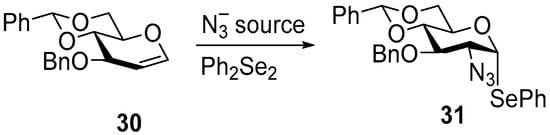

In order to study an alternative approach toward phenylseleno 2-azido-2-deoxy-glucosides, the APS of 3-O-benzyl-4,6-di-O-benzylidene-glucal 30 was studied as the substituent of triacetylglucal 6 (Scheme 4). It was first examined under the heterogeneous conditions that had proved fastest for galactal 1 (EtCN as solvent, a substrate concentration of 0.21 molar, and 0.6 equiv of Ph2Se2). Synthesis of 30 was carried out through known 2-O-acetyl-3-O-benzyl-4,6-O-benzyliden-β-d-glucopyranoside [48] and is described in Supplementary Information. Under these conditions, only trace amounts of phenylseleno 2-azido-2-deoxy-glucoside 31 were detected sporadically (Table 5, entry 1). Follow-up tests showed that this sporadic activity correlated with traces of μ-oxo-bis(acetoxy)iodobenzene (μ-oxo-BAIB) [49], a minor impurity occasionally present in commercial BAIB, rather than with the standard oxidant itself.

Scheme 4.

APS of 3-O-benzyl-4,6-di-O-benzylidene-glucal 30.

Table 5.

Influence of oxidant and solvent on the APS of glucal 30 (Scheme 4).

To clarify the role of μ-oxo-BAIB, it was prepared from BAIB (see Supplementary Information) and added (1:1, n/n) to the standard heterogeneous APS of 30 (entry 2). This reaction favored the formation of the gluco-product 31, albeit in only 22% isolated yield. Although not preparatively useful, the striking selectivity encouraged us to revisit the classical homogeneous protocol. With TMSN3/BAIB in CH2Cl2 at −35 °C, the glucoside 31 was obtained in 65% yield after chromatography (entry 3). When BAIB was replaced by BAIB/μ-oxo-BAIB (1:4) at the same temperature, the reaction time shortened from 24 h to 30 min, a 50-fold acceleration, while the isolated yield increased to 76% (entry 4). These results indicate that (i) low temperature is essential for efficient conversion of used glucal 30, and (ii) μ-oxo-BAIB acts as a more selective oxidant than BAIB in this substrate class.

Systematic variation of solvent polarity and phase-transfer conditions revealed that the rate and selectivity of azidophenylselenylation (APS) are governed primarily by the efficiency of N3− mass transfer. Improved dispersion of NaN3 directly correlated with cleaner reaction profiles and higher yields. For tri-O-acetyl-d-galactal 1, optimal performance in EtCN is attributed to rapid N3− delivery and efficient generation of the reactive PhSeN3. In contrast, for glucal 6, benzene afforded the best results, maintaining anti-Markovnikov selectivity through its low polarity.

In EtCN with glucal 6, the high solubility of NaN3 is offset by solvent polarity effects that alter the relative rates of competing pathways, most likely through polarization of the C=C bond and steric differences between glucal 6 and galactal 1, thereby slowing conversion despite potentially faster mass transfer.

Catalytic TMSCl had little influence on the APS rate or conversion, whereas TMSOTf accelerated galactal APS two- to threefold in EtCN but diverted the reaction toward phenylselenoacetylation (→19) in benzene. These observations highlight the dual role of silyl additives as both phase-transfer promoters and electrophilic activators of BAIB, depending on solvent coordination strength.

Scaling experiments confirmed that mass-transfer control remains crucial at preparative levels. APS of galactal 1 in EtCN and glucal 6 in benzene (1.5–2 g, >3 mmol) furnished 76% of crystalline phenylseleno 2-azidogalactoside 2 and 72% of a 1.2:1 mixture of phenylseleno-2-azido-glucose and -mannose isomers 7 and 8. The same optimized protocol applied to l-fucal 20 in MeCN produced a 91% combined yield dominated by 2-azidofucoside 21 (79%), together with minor byproducts 22–24. APS of l-rhamnal 25 in benzene gave mainly 2-azidoquinovoside 26 and 2-azidorhamnoside 27 with only traces of phenylseleno derivatives 28 and 29.

When applied to 3-O-benzyl-4,6-O-benzylidene-glucal 30, the use of μ-oxo-BAIB markedly promoted formation of phenylseleno-2-azidoglucose; under homogeneous TMSN3/CH2Cl2 conditions, the yield reached 76%, 12–15% higher than with BAIB alone.

Thus, the study provides both a practical synthetic route to biologically relevant azido-selenoglycoside building blocks and mechanistic insight into the factors that govern APS selectivity and scalability.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Methods

EtCN, benzene, and heptane were used as received. Comparative runs with EtCN (dried by successive distillation over P2O5 and CaH2) and benzene (distilled over sodium/benzophenone ketyl) showed no change in the reaction rate or isolated yield of the APS products. CH2Cl2, MeCN were purified as described for EtCN and were not tested for their impact on the efficiency of the APS. Analytical thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on silica gel 60 F254 aluminum sheets (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), and visualization was accomplished using UV light (Analytik Jena (UVP), Jena, Germany) or by charring at 150 °C with 10% (v/v) H3PO4 in isopropanol. Column chromatography was performed on silica gel 60, 40–63 μm (Merck) and, when specified on, 25–40 µm (Merck). Optical rotation values were measured using a JASCO DIP-360 polarimeter (JASCO, Tokyo, Japan) at a specified temperature in the specified solvent. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded at 300, 400, and 600 MHz as detailed for each compound. Chemical shifts were referenced to residual solvent signals. Structural assignments were made with additional information from gCOSY, gHSQC. High-resolution mass spectra were acquired by electrospray ionization on a MicrO TOF II (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, USA) instrument.

3.2. Safe Note

A moderate evolution of N2 can accompany PhI(N3)2 side pathways; therefore, vigorous stirring in fully closed vessels should be avoided. For safety reasons, EtOAc is recommended for the aqueous work-up instead of CHCl3, which may form unstable species under azidation conditions.

3.3. Representative Example of Heterogeneous APS Test Reaction Protocol

- 3,4,6-tri-O-acetyl-2-azido-2-deoxy-1-(phenylseleno)-α-d-galactopyranoside (2) (Table 1, Entry 4)

To the tri-O-acetylgalactal 1 (0.42 mmol, 0.21 M) solution in EtCN (2 mL) cooled to +15 °C, NaN3 (54.6 mg, 0.84 mmol) was first added, followed by BAIB (162.3 mg, 0.504 mmol). After 20 min of stirring, Ph2Se2 (78.7 mg, 0.25 mmol) was introduced into the reaction mixture. The progress of the reaction was monitored by TLC (toluene/EtOAc, 7:1). Once the reaction was complete, the contents of the test tube were diluted 4–5 times with EtOAc and transferred to a separatory funnel containing an aqueous mixture of 10% Na2S2O3 and saturated NaHCO3 (1:1). The funnel was shaken, and after separation of the organic phase, the aqueous phase was washed three additional times with EtOAc. The combined organic extracts were concentrated under reduced pressure, and the dry residue was analyzed by NMR. Data for phenylseleno 2-azido-2-deoxy-galactoside (2): colorless oil; Rf = 0.40 (toluene/EtOAc, 7:1). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.63–7.56 (m, 2H, PhSe), 7.32–7.24 (m, 3H, PhSe), 5.99 (d, J1,2 = 5.4 Hz, 1H, H-1), 5.46 (br d, J4,3 = 3.3 Hz, 1H, H-4), 5.11 (dd, J3,2 = 10.8 Hz, J3,4 = 3.2 Hz, 1H, H-3), 4.25 (dd, J2,1 = 5.4 Hz, J2,3 = 10.9 Hz, 1H, H-2), 4.66 (br t, J5,6 = 6.5 Hz, 1H, H-5), 4.04 (m, 2H, H-6), 2.14, 2.05, 1.96 (3s, 3×1H, CH3 (Ac)). 13C{1H } NMR (100.6 MHz, CDCl3): δ 170.5, 170.1, 169.7 (C=O (Ac)), 134.9 (ipso Ar(PhSe)), 129.4, 128.3 (PhSe), 81.2 (C-1), 71.4 (C-3), 69.1 (C-5), 67.3 (C-4), 61.7 (C-6), 20.8 (CH3(Ac)). Data are consistent with the literature [37]. NMR data for products 3–5, identified as components of the mixture 2–5 obtained after APS of galactal, are provided in the Supplementary Information and are consistent with the reported literature data [37].

3.4. Representative Example of Heterogeneous APS Test Reaction Protocol with Additive

- 3,4,6-tri-O-acetyl-2-azido-2-deoxy-1-(phenylseleno)-α-d-galactopyranoside (2) (Table 2, Entry 3)

The reaction was conducted as described above, except that TMSOTf (6.3 µL, 4 mol % relative to NaN3) was added immediately after the addition of Ph2Se2.

3.5. General Large-Scale APS Procedure

- 3,4,6-tri-O-acetyl-2-azido-2-deoxy-1-(phenylseleno)-α-d-galactopyranoside (2)

To a solution of tri-O-acetylgalactal 1 (1.10 g, 4.0 mmol) in EtCN (20.3 mL), NaN3 (523 mg, 8.05 mmol) was added at room temperature under argon in a cylindrical round-bottomed flask (30 mm diameter) equipped with a 23 × 9 mm PTFE-coated stir bar. The mixture was sonicated for 3 min, then stirred for an additional 10 min. After cooling to +15 °C, BAIB (1.53 g, 4.8 mmol) was added portion-wise over 10 min, and stirring was continued for 15 min until the reaction mixture developed a pearlescent sheen. Ph2Se2 (750.6 mg, 2.4 mmol) was then added portion-wise over 15 min, and the reaction was stirred at 1000–1100 rpm for 27 h, until completion. The mixture was quenched as described for the representative small-scale test reaction. After quenching and concentration, the solids (2.3 g) were purified by crystallization from iPrOH (3.8 mL) to afford pure phenyl seleno-2-azido-galactoside 2 (1.43 g, 76%).

- 3,4,6-tri-O-acetyl-2-azido-2-deoxy-1-(phenylseleno)-α-l-gluco- (7) and mannopyranoside (8)

APS of glucal 6 was carried out according to the general large-scale procedure described for galactal 1, except that benzene was used as the solvent. The reaction afforded a combined yield of 70–72% for the isolated mixture, consisting of 7, 8, and minor byproducts 9 and 10 in a 1.2:1:0.2:0.1 ratio, as determined by NMR after partial separation by column chromatography on SiO2 (toluene-EtOAc gradient, 10 → 35%). NMR data for products 7–10 from the APS of: 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.59–7.52 (m, 5.8H, Ph), 7.34–7.26 (m, 8.8H, Ph), 5.92 (d, J1,2 = 5.6Hz, 1H, H-17), 5.78 (d, J1,2 = 1.4 Hz, 1.3H, H-18), 5.65 (d, J1,2 = 1.8 Hz, 0.24H, H-19), 5.40 (t, 0.24H, H-49), 5.36 (t, J4,3 = J4,5 = 9.7 Hz, 1.3H, H-48), 5.31–5.24 (m, 2.6H, H-37,8), 5.04 (dd, J = 9.2 Hz, J = 10.2 Hz, H-47), 4.92 (m, 1H, H-57), 4.40 (m, 1.3H, H-58), 3.35 (dd, J2,1 = 1.4 Hz, J2,3 = 3.7 Hz, 1.3H, H-28), 4.29–4.25 (m, 2.3H, H-6A7,8), 4.09–4.03 (m, 2.3H, H-6B8, H-27), 3.94 (dd, J6B,5 = 2.2 Hz, J6B,6A = 12.5 Hz, 1H, H-6B7), 3.80 (dd, J2,1 = 1.9 Hz, J2,3 = 4.4 Hz, H-29), 2.15, 2.12, 2.08, 2.06, 2.05, 2.04, 2.00 (7×s, 28.6H, CH3(Ac)). 13C{1H } NMR (150.9 MHz, CDCl3): δ 170.7, 170.6, 170.1, 169.9, 169.6 (C=O (Ac)), 134.7, 134.3, 129.6, 129.4, 128.6, 128.4 (PhSe), 90.3 (C-19), 83.8 (C-17), 82.7 (C-18), 74.0 (C-59), 73.0 (C-37), 71.7 (C-38), 71.4 (C-58), 70.2 (C-57), 68.5 (C-47), 66.7 (C-49), 66.0 (C-48), 63.5 (C-28), 62.4 (C-27), 62.3 (C-69), 62.2 (C-68), 61.9 (C-67), 47.2 (C-29), 20.8 (CH3 (Ac)) and are consistent with the literature [35].

- 3,4-di-O-acetyl-2-azido-2-deoxy-1-(phenylseleno)-α-l-fucopyranoside (21)

APS of fucal 20 was carried out according to the general large-scale procedure described for galactal 1, except that MeCN was used as the solvent. The reaction afforded a combined yield of 91% for the isolated mixture, consisting of 21 (79%), phenyl 2-azido-2,6-dideoxy-l-taloside 22 (8%), 2-phenylseleno-2,6-dideoxy-l-talosyl acetate 24 (2%), and 2-deoxy-2-phenylseleno-fucosyl acetate 23 (1%), as determined by NMR after partial separation by column chromatography on SiO2 (petroleum ether-EtOAc gradient, 1:0 → 9:1). Data for compounds 21–24: 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.63–7.54 (m, 3H), 7.37–7.26 (m, 5H), 5.97 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H, H-121), 5.86 (br. s, 0.3H, H-122), 5.70 (s, 0.13H, H-124), 5.65 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 0.04H, H-123), 5.40–5.26 (m, 2H, H-3, H-4), 5.15 (dd, J = 10.8, 3.2 Hz, 1H, H-321), 4.52 (m, 1.3H, H-521,22), 4.36–4.21 (m, 1.2H, H-524,23), H-221) 4.10–4.05 (m, 0.3H, H-222), 3.62–3.55 (m, 0.04H, H-223), 3.49–3.44 (m, 0.13H, H-224), 2.19 (s, 3H), 2.09 (s, 3H), 1.31–1.17 (m, 2H, H-6), 1.11 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 3H, H-621). 13C NMR (75.5 MHz, CDCl3): δ 170.3, 169.7, 134.6, 134.2, 133.9, 129.5, 129.4, 129.1, 128.2, 128.0, 92.0 (C-124), 91.1 (C-123), 84.4 (C-121), 83.3 (C-122), 71.6 (C-321), 70.6 (C-323), 70.1 (C-421), 69.0, 68.6 (C-322), 68.3, 67.4, 67.3, 67.1, 59.5 (C-222), 58.7 (C-221), 45.7 (C-224), 43.5 (C-223), 30.0, 29.7, 20.9, 20.6, 20.6, 16.3 (C-6), 16.0 (C-6), 15.8 (C-6). The characterization data for 21 are consistent with those reported [50].

- 3,4-di-O-acetyl-2-azido-2-deoxy-1-(phenylseleno)-α-l-quinovoso- (26) and -rhamnopyranosides (27)

APS of rhamnal 25 was carried out according to the general large-scale procedure described for galactal 1, except that benzene was used as the solvent and 1.2 equiv Ph2Se2 was employed. The reaction afforded a combined yield of 49% for the isolated mixture, consisting of 26 (26%), phenyl 2-azido-2,6-dideoxy-l-rhamnoside 27 (19%), 2-phenylseleno-2,6-dideoxy-l-quinovosyl acetate 28 and 2-deoxy-2-phenylseleno-rhamnosyl acetate 29 (4%), as determined by NMR after partial separation by column chromatography on SiO2 (toluene-EtOAc gradient, 1:0 → 98:2). Data for compounds 26–29: 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.73–7.53 (m, 4H), 7.46–7.13 (m, 7H), 5.85 (d, J1,2 = 5.4 Hz, 1H, H-126), 5.70 (d, J1,2 = 1.2 Hz, 0.7H, H-127), 5.62–5.56 (m, 0.15H, H-128,29), 5.37–5.10 (m, 2.7H, H-3, H-4), 4.80 (t, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H, H-426), 4.39–4.16 (m, 2.4H, H-227, H-526, H-527), 4.07–3.97 (m, 1H, H-226), 3.83 (dd, J = 4.0, 1.7 Hz, 0.1H, H-229), 2.13–2.04 (m, 11H, Ac), 1.29–1.20 (m, 3H, H-627, H-628,29, 1.15 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 3H, H-626). 13C NMR (76 MHz, CDCl3) δ 134.6, 134.1, 129.4, 129.2, 128.3, 128.1, 83.9 (C-126), 82.6 (C-127), 73.6 (C-426), 72.9 (C-326), 71.5, 70.8, 69.7 (C-527), 68.4 (C-526), 63.8, 62.7 (C-226), 20.7, 20.6, 17.2 (C-6), 17.0 (C-6). The characterization data for 26 and 27 are consistent with those reported [35].

3.6. Representative Example of the APS of Benzylidene-Protected Glucal 30 Using μ-Oxo-bis(acetyloxy)iodobenzene as the Oxidant

- Phenyl 2-azido-3-O-benzyl-4,6-O-benzylidene-2-deoxy-1-selenyl-α-d-glucopyranoside (31) (Table 4, Entry 4)

A solution of glucal 30 (40.0 mg, 0.12 mmol) and Ph2Se2 (38.4 mg, 0.12 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (1.4 mL) was cooled to −35 °C under argon. While stirring, TMSN3 (0.24 mmol, 32.4 µL) was added, followed by μ-oxo-BAIB and BAIB mixture (73 mg, containing 80 mol % μ-oxo-BAIB and 20 mol % BAIB). After 30 min, TLC analysis showed complete consumption of the starting material. The reaction mixture was then diluted with CH2Cl2 and washed with saturated aqueous NaHCO3. The aqueous phase was extracted twice with CH2Cl2, and the combined organic extracts were dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. Purification by silica-gel chromatography (petroleum ether-EtOAc gradient, 40:1 → 15:1) afforded colorless crystals of phenyl 2-azido-3-O-benzyl-4,6-O-benzylidene-2-deoxy-1-seleno-α-d-glucopyranoside 31 (49 mg, 76%). Data for 31: 1H NMR (CDCl3,300 MHz): δ 7.72 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.63 (dd, J = 8.0, 1.6 Hz, 4H), 7.60–7.21 (m, 32H), 5.89 (d, J1,2 = 9.5 Hz, 1H, H-1), 5.62 (s, 1H, PhCH), 5.01 (d, JAB = 10.9 Hz, 1H, BnA), 4.81 (d, JAB = 10.9 Hz, 1H, BnB), 4.37 (dd, J6A,6B = 10.5, J6A,5 = 5.0 Hz, 1H, H-6A), 3.86–3.72 (m, 2H, H-4, H-6B), 3.64 (dd, J3,2 = 10.6, J3,4 = 8.7 Hz, 1H, H-3), 3.50 (td, J5,4 = 9.7, J5,6A = 5.0 Hz, 1H, H-5), 3.30 (dd, J2,3 = 10.6, J2,1 = 9.5 Hz, 1H, H-2), 1.99 (s, 3H, Ac). 13C{1H} NMR (76 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 168.9, 138.1, 137.1, 135.9, 135.3, 129.3, 129.2, 129.1, 129.0, 128.5, 128.4, 128.3, 128.3, 128.3, 128.2, 127.9, 127.7, 127.1, 126.1, 126.0, 101.3 (PhCH), 94.4 (C-1), 83.1 (C-4), 78.0 (C-3), 77.5, 77.5, 76.6, 75.3 (Bn), 68.5 (C-6), 66.5 (C-5), 48.7 (C-2), 20.7 (Ac). Characterization data are consistent with those reported [51].

4. Conclusions

It was shown that APS efficiency critically depends on controlling N3− mass transfer, which can be regulated by solvent polarity. While the reaction in general benefits from a compromise between solvent polarity, which promotes N3− mass transfer, and unpolar media, which favor the desired regioselectivity, glycal substrates with different C-4 configurations (galacto- and gluco-series) require distinct solvent types to achieve optimal conversion and purity. The optimized heterogeneous APS protocol developed in this study provides reproducible, gram-scale access to three valuable phenylseleno 2-azido-2-deoxy-monosaccharides, namely galactoside 2, glucoside 7, and fucoside 21, and extends the methodology to quinovose 26 and rhamnose 27 derivatives. Moreover, application of μ-oxo-BAIB to the APS of 3-O-benzyl-4,6-O-benzylidene-d-glucal 30 enabled isolation of a pure gluco-configured product 31 in high yield, underscoring the potential of this oxidant for selective and scalable synthesis. Further study of the discovered protocol and its dependence on glycal structure is under investigation in this laboratory and will be reported in due course.

Supplementary Materials

The following Supplementary information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/molecules31010054/s1. It contains full experimental procedures fot the preparation of glycals 1, 6, 20, 25, and 30, the synthesis of µ-oxo-BAIB, and additional optimization experiments including: Scheme S1. Preparation of glycals 1 and 6; Scheme S2. Preparation of l-fucal 20; Scheme S3. Preparation of l-rhamnal 25; Scheme S4. Preparation of glucal 30; Scheme S5. Synthesis of µ-oxo-BAIB. Complete NMR data for compounds 1–9 and 16 are provided, together with the 1H NMR spectra of crude APS mixtures (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table S1): Figure S1. Comparison of 1H NMR spectra of crude mixtures of APS transformation of galactal 1 in various solvents (Table 1) recorded in CDCl3; Figure S2. Selected 1H NMR spectral region (δ 5.47–6.06 ppm) of the crude reaction mixtures of tri-acetylgalactal 1 APS (Table S1); Figure S3. Selected 1H NMR spectral region (δ 5.47–6.06 ppm) of the crude reaction mixtures of tri-acetylgalactal 1 APS (Table 2); Figure S4. Selected 1H NMR spectral region (δ 5.47–6.06 ppm) of the crude reaction mixtures tri-acetylglucal 6 APS (Table 3). Tables S1–S6 summarize the reaction conditions, reagent quantities, and NMR assignments: Table S1. Selected APS of galactal 1 (in addition to Table 1, Scheme 1) and outcome determined by NMR; Table S2. Reagent quantities, solvent system, and substrate concentration for azidophenylselenylations of galactal 1 presented in Table 1 and Table 2; Table S3. Reagent quantities, solvent system, and substrate concentration for azidophenylselenylations of glucal 6 presented in Table 3; Table S4. Reagent quantities, solvent system, and substrate concentration for azidophenylselenylations of galactal 1 presented in Table S1; Table S5. 1H-NMR data for compounds 1–9, 16 (CDCl3); Table S6. 13C{1H}-NMR data for compounds 1–9, 16 (CDCl3).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.S.K. and N.E.N.; methodology, B.S.K. and N.E.N.; validation, B.S.K. and N.E.N.; investigation, B.S.K., O.V.B., D.V.Y. and T.M.V.; resources, N.E.N.; writing—original draft preparation, B.S.K., D.V.Y., and T.M.V.; writing—review and editing, N.E.N.; visualization, B.S.K.; supervision, N.E.N.; funding acquisition, N.E.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (Grant 19-73-30017-P).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and Supplementary Information. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| APS | Azidophenylselenylation |

| BAIB | [Bis(acetoxy)iodo]benzene |

| EtCN | Propionitrile |

| MeCN | Acetonitrile |

| µ-oxo-BAIB | μ-oxo-bis(acetoxy)iodobenzene (BAIB dimer) |

References

- Østerlid, K.E.; Li, S.; Unione, L.; Bino, L.D.; Sorieul, C.; Carboni, F.; Berni, F.; Bertuzzi, S.; Van Puffelen, B.; Arda, A.; et al. Synthesis, Conformal Analysis, and Antibody Binding of Staphylococcus aureus Capsular Polysaccharide Type 5 Oligosaccharides. Angew. Chem. 2025, 137, e202511378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, H.; Xu, L.; Wang, H.; Gao, J. Chemical Synthesis of Conjugation-Ready Oligosaccharide Haptens of Pseudomonas aeruginasa O11 and Staphylococcus aureus Type 5. Org. Lett. 2025, 27, 12160–12165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhaumik, I.; Misra, A.K. Convergent Synthesis of the Tetrasaccharide Repeating Unit of the O -Polysaccharide of Salmonella enterica O41. ChemistrySelect 2017, 2, 3065–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H.; Mandal, P.K. Synthetic Routes Toward Pentasaccharide Repeating Unit Corresponding to the O-Antigen of Escherichia coli O181. Tetrahedron Lett. 2019, 60, 860–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.; Mukhopadhyay, B. Chemical Synthesis of the Tetrasaccharide Repeating Unit of the O-Antigenic Polysaccharide from Plesiomonas shigelloides Strain AM36565. Carbohydr. Res. 2013, 376, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Meng, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhao, Q.; Gao, J. Total Synthesis of the Tetrasaccharide Haptens of Vibrio vulnificus MO6-24 and BO62316 and Immunological Evaluation of Their Protein Conjugates. JACS Au 2022, 2, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, A.; Kulkarni, S.S. Total Synthesis of the Repeating Units of Proteus penneri 26 and Proteus vulgaris TG155 via a Common Disaccharide. Org. Lett. 2023, 25, 4400–4405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemieux, R.U.; Ratcliffe, R.M. The Azidonitration of Tri-O-Acetyl-d-Galactal. Can. J. Chem. 1979, 57, 1244–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plattner, C.; Höfener, M.; Sewald, N. One-Pot Azidochlorination of Glycals. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 545–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.-X.; Tsai, Y.-T.; Lin, Y.-T.; Li, J.-Y.; Chang, C.-C. Design and Synthesis of Trivalent Tn Glycoconjugate Polymers by Nitroxide-Mediated Polymerization. Tetrahedron 2019, 75, 130776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, K.; Kawa, M.; Saito, Y.; Hashimoto, H.; Yoshimura, J. Synthetic Studies on Glycocinnamoylspermidine. II. Synthesis of 4-O-(2-Azido-2-Deoxy-d-Xylopyranosyl)-2-Azido-2-Deoxy-d-Xylopyranose Derivatives. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1986, 59, 3137–3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Hendriks, A.; van Dalen, R.; Bruyning, T.; Meeuwenoord, N.; Overkleeft, H.S.; Filippov, D.V.; van der Marel, G.A.; van Sorge, N.M.; Codée, J.D.C. (Automated) Synthesis of Well-Defined Staphylococcus aureus Wall Teichoic Acid Fragments. Chem.—A Eur. J. 2021, 27, 10461–10469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Overkleeft, H.S.; van der Marel, G.A.; Codée, J.D.C. Reagent Controlled Glycosylations for the Assembly of Well-Defined Pel Oligosaccharides. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 15872–15884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shou, K.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, Y.; Liu, B.; Zhou, Q.; Tan, Q.; Li, F.; Wang, X.; Lu, G.; Xiao, G. Highly Stereoselective α-Glycosylation with GalN3 Donors Enabled Collective Synthesis of Mucin-Related Tumor Associated Carbohydrate Antigens. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 6552–6561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slättegård, R.; Teodorovic, P.; Kinfe, H.H.; Ravenscroft, N.; Gammon, D.W.; Oscarson, S. Synthesis of Structures Corresponding to the Capsular Polysaccharide of Neisseria meningitidis Group A. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2005, 3, 3782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Vorm, S.; Overkleeft, H.S.; van der Marel, G.A.; Codée, J.D.C. Stereoselectivity of Conformationally Restricted Glucosazide Donors. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 4793–4811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lourenço, E.C.; Ventura, M.R. Improvement of the Stereoselectivity of the Glycosylation Reaction with 2-Azido-2-Deoxy-1-Thioglucoside Donors. Carbohydr. Res. 2016, 426, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhetuwal, B.R.; Wu, F.; Meng, S.; Zhu, J. Stereoselective Synthesis of 2-Azido-2-Deoxy-β-d-Mannosides via Cs2CO3-Mediated Anomeric O-Alkylation with Primary Triflates: Synthesis of a Tetrasaccharide Fragment of Micrococcus luteus Teichuronic Acid. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 16196–16206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironov, Y.V.; Sherman, A.A.; Nifantiev, N.E. Homogeneous Azidophenylselenylation of Glycals Using TMSN3–Ph2Se2–PhI(OAc)2. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 9107–9110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatuntseva, E.A.; Sherman, A.A.; Tsvetkov, Y.E.; Nifantiev, N.E. Phenyl 2-Azido-2-Deoxy-1-Selenogalactosides: A Single Type of Glycosyl Donor for the Highly Stereoselective Synthesis of α- and β-2-Azido-2-Deoxy-d-Galactopyranosides. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 708–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazakova, E.D.; Yashunsky, D.V.; Krylov, V.B.; Bouchara, J.-P.; Cornet, M.; Valsecchi, I.; Fontaine, T.; Latgé, J.-P.; Nifantiev, N.E. Biotinylated Oligo-α-(1→4)-d-Galactosamines and Their N-Acetylated Derivatives: α-Stereoselective Synthesis and Immunology Application. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 1175–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazakova, E.D.; Yashunsky, D.V.; Nifantiev, N.E. The Synthesis of Blood Group Antigenic A Trisaccharide and Its Biotinylated Derivative. Molecules 2021, 26, 5887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kärkkäinen, T.S.; Ravindranathan Kartha, K.P.; MacMillan, D.; Field, R.A. Iodine-Mediated Glycosylation En Route to Mucin-Related Glyco-Aminoacids and Glycopeptides. Carbohydr. Res. 2008, 343, 1830–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, B.; van Dijk, J.H.M.; Zhang, Q.; Overkleeft, H.S.; van der Marel, G.A.; Codée, J.D.C. Synthesis of the Staphylococcus aureus Strain M Capsular Polysaccharide Repeating Unit. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 2514–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedini, E.; Cirillo, L.; Parrilli, M. Synthesis of the Trisaccharide Outer Core Fragment of Burkholderia cepacia pv. Vietnamiensis Lipooligosaccharide. Carbohydr. Res. 2012, 349, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, B.; Parameswarappa, S.G.; Lisboa, M.P.; Kottari, N.; Guidetti, F.; Pereira, C.L.; Seeberger, P.H. Nucleophile-Directed Stereocontrol Over Glycosylations Using Geminal-Difluorinated Nucleophiles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 14431–14434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Qiao, Z.; Wang, L.; Wang, P.; Song, N.; Li, M. β-Glycosylations with 2-Deoxy-2-(2,4-Dinitrobenzenesulfonyl)-Amino-Glucosyl/Galactosyl Selenoglycosides: Assembly of Partially N-Acetylated β-(1→6)-Oligoglucosaminosides. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 9004–9025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Njeri, D.K.; Ragains, J.R. Total Synthesis of an All-1,2-Cis-Linked Repeating Unit from the Acinetobacter baumannii D78 Capsular Polysaccharide. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 3461–3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Shen, W.; Cao, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xue, W. Thiourea-Cu(OTf)2/NIS-Synergistically Promoted Stereoselective Glycoside Formation with 2-Azidoselenoglycosides or Thioglycosides as Donors. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2024, 22, 2137–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, B.; Ali, S.; Overkleeft, H.S.; van der Marel, G.A.; Codée, J.D.C. Mapping the Reactivity and Selectivity of 2-Azidofucosyl Donors for the Assembly of N-Acetylfucosamine-Containing Bacterial Oligosaccharides. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 848–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linker, T. Addition of Heteroatom Radicals to Endo-Glycals. Chemistry 2020, 2, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tingoli, M.; Tiecco, M.; Chianelli, D.; Balducci, R.; Temperini, A. Novel Azido-Phenylselenenylation of Double Bonds. Evidence for a Free-Radical Process. J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 6809–6813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czernecki, S.; Ayadi, E.; Randriamandimby, D. Seleno Glycosides. 2. Synthesis of Phenyl 2-(N-Acetylamino)- and 2-Azido-2-Deoxy-1-Seleno-α-d-Glycopyranosides via Azido-Phenylselenylation of Diversely Protected Glycals. J. Org. Chem. 1994, 59, 8256–8260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czernecki, S.; Ayadi, E.; Randriamandimby, D. New and Efficient Synthesis of Protected 2-Azido-2-Deoxy-Glycopyranoses from the Corresponding Glycal. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1994, 35–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoyo-Gonzalez, F.; Calvo-Flores, F.G.; Garcia-Mendoza, P.; Hernandez-Mateo, F.; Isac-Garcia, J.; Robles-Diaz, R. Synthesis of Phenyl 2-Azido-2-Deoxy-1-Selenoglycosides from Glycals. J. Org. Chem. 1993, 58, 6122–6125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironov, Y.V.; Grachev, A.A.; Lalov, A.V.; Sherman, A.A.; Egorov, M.P.; Nifantiev, N.E. A Study of the Mechanism of the Azidophenylselenylation of Glycals. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2009, 58, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guberman, M.; Pieber, B.; Seeberger, P.H. Safe and Scalable Continuous Flow Azidophenylselenylation of Galactal to Prepare Galactosamine Building Blocks. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2019, 23, 2764–2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomitskaya, P.A.; Argunov, D.A.; Tsvetkov, Y.E.; Lalov, A.V.; Ustyuzhanina, N.E.; Nifantiev, N.E. Further Investigation of the 2-Azido-Phenylselenylation of Glycals. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 2021, 5897–5904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peturova, M.; Vitiazeva, V.; Toman, R. Structural Features of the O-Antigen of Rickettsia typhi, the Etiological Agent of Endemic Typhus. Acta Virol. 2015, 59, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atiemo-Obeng, V.A.; Penney, W.R.; Armenante, P. Solid–Liquid Mixing. In Handbook of Industrial Mixing; Paul, E.L., Atiemo-Obeng, V.A., Kresta, S.M., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 543–584. ISBN 978-0-471-26919-9. [Google Scholar]

- Varala, R.; Seema, V.; Dubasi, N. Phenyliodine(III)Diacetate (PIDA): Applications in Organic Synthesis. Organics 2022, 4, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltanzadeh, B.; Jaganathan, A.; Yi, Y.; Yi, H.; Staples, R.J.; Borhan, B. Highly Regio- and Enantioselective Vicinal Dihalogenation of Allyl Amides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 2132–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roessler, A.; Rys, P. Wenn die Rührgeschwindigkeit die Produktverteilung bestimmt: Selektivität mischungsmaskierter Reaktionen. Chem. Unserer Zeit 2001, 35, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Wu, C.; Lin, M.; Liao, P.; Chang, C.; Chuang, H.; Lin, S.; Lam, S.; Verma, V.P.; Hsu, C.; et al. Establishment of Guidelines for the Control of Glycosylation Reactions and Intermediates by Quantitative Assessment of Reactivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 16775–16779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koseki, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Kamishima, T.; Kwon, E.; Kasai, H. Formation of Five-Membered Carbocycles from d -Glucose: A Concise Synthesis of 4-Hydroxy-2-(Hydroxymethyl)Cyclopentenone. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2019, 92, 1324–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grugel, H.; Albrecht, F.; Boysen, M.M.K. pseudo Enantiomeric Carbohydrate Olefin Ligands—Case Study and Application in Kinetic Resolution in Rhodium(I)-Catalysed 1,4-Addition. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2014, 356, 3289–3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, J.T.; van Heerden, F.R.; Holzapfel, C.W. Preparation of an Analogue of Orbicuside A, an Unusual Cardiac Glycoside. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2005, 16, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitz, M.; Bundle, D.R. Synthesis of Di- to Hexasaccharide 1,2-Linked β-Mannopyranan Oligomers, a Terminal S-Linked Tetrasaccharide Congener and the Corresponding BSA Glycoconjugates. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 66, 8411–8423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, H.-C.; Bryan, J.; Henson, W.; Zhdankin, V.V.; Gandhi, K.; David, S. New, Milder Hypervalent Iodine Oxidizing Agent: Using μ-Oxodi(Phenyliodanyl) Diacetate, a (Diacetoxyiodo)Benzene Derivative, in the Synthesis of Quinones. J. Chem. Educ. 2019, 96, 2622–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Schumann, B.; Zou, X.; Pereira, C.L.; Tian, G.; Hu, J.; Seeberger, P.H.; Yin, J. Total Synthesis of a Densely Functionalized Plesiomonas shigelloides Serotype 51 Aminoglycoside Trisaccharide Antigen. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 3120–3127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokatly, A.I.; Vinnitsky, D.Z.; Kamneva, A.A.; Yashunsky, D.V.; Tsvetkov, Y.E.; Nifantiev, N.E. Glycosylation with Derivatives of Phenyl 2-Azido-2-Deoxy-1-Seleno-α-d-Gluco- and -α-d-Mannopyranosides. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2023, 72, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.