Abstract

With the rapid advancements in industrial technology, the demand for high-performance lubrication has surpassed the capabilities of traditional solid or liquid lubricants. In this study, a novel MXene-based solvent-free lubricating nanofluid was developed through the surface functionalization of Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets. This innovative material combines the superior mechanical properties of solid Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets with the stable flow and rapid self-repairing capabilities of liquid lubricants. The successful synthesis of the MXene-based solvent-free nanofluid lubricant was confirmed through a series of characterization techniques, and it was demonstrated that this nanofluid maintained excellent flowability at room temperature. Subsequent tribological tests revealed that the friction coefficient and the wear performance of the MXene-based solvent-free nanofluid lubricant improved with increasing mass concentrations of Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets under consistently applied loads. These results indicate that the MXene-based solvent-free nanofluid lubricant significantly reduces friction and wear, showcasing its potential as a high-performance lubricant for industrial applications.

1. Introduction

The annual economic losses caused by friction and wear between metal components are immense. Friction is a primary contributor to part degradation, reduced equipment lifespan, and significant energy waste [1]. It is estimated that approximately one-third of the energy consumed in the global mining and transportation industries is due to overcoming friction [2,3]. Moreover, around 80% of mechanical failures are attributed to component wear [4,5]. Lubrication is a highly effective method for controlling friction and wear, helping to reduce energy loss and extend the operational life of equipment [6]. Lubricants minimize frictional wear between interacting surfaces and facilitate the smooth relative motion of solid components [7]. Lubricants are categorized into various types based on their physical or chemical properties, including solid lubricants (e.g., graphene) [8,9,10,11], gaseous lubricants (e.g., compressed air or other gases) [12,13], liquid lubricants (e.g., oils) [14,15,16], and semi-solid lubricants [17,18]. However, both solid and liquid lubricants have inherent limitations when used independently. Solid lubricants often suffer from poor heat dissipation, limited self-healing capabilities, and shorter lifespans [19,20,21,22], while liquid lubricants are highly dependent on ambient temperature and are prone to issues such as creep [23,24,25,26]. To address these challenges, integrating solid lubricants into liquid lubrication systems as filler components or leveraging chemical engineering techniques to transform solid-phase lubricants into liquid-phase systems can offer a promising solution. This approach combines the rapid self-repair, high mechanical strength, and stability of solid lubricants with the fluidity and adaptability of liquid lubricants, potentially resulting in a new generation of lubricants with enhanced load-bearing capacity and performance.

Fortunately, the combination of liquid fluidity and solid functionality through surface modification methods has provided a versatile platform for specific applications in recent decades [27,28,29,30]. For instance, Guo et al. [31] developed a solvent-free lubricant by modifying reduced graphene oxide with hyperbranched polyamine ester liquid using surface chemical engineering techniques. They observed significant improvements in the lubricant’s dispersibility and lubricity. Similarly, various surface modification strategies have been employed to synthesize porous liquids for applications in gas adsorption and separation. Li et al. [32] used imidazolium cationic-based Polymerized Ionic Liquids (PILs) to modify carbon networks, creating HCS@PILs. Mobility was achieved through an anion-exchange method by balancing the surface charge of HCS@PILs with Polyethylene Glycol (PEG). These strategies for preparing solvent-free nanofluids provide valuable insights and directions for the synthesis of advanced lubricants with superior performance in the future.

Two-dimensional (2D) nanomaterials have shown great potential as lubricants due to their exceptional physical and chemical properties [33,34]. For example, graphene [31,35,36] and hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN) [37] have been extensively studied as lubricants over the past decade [34,38,39,40,41,42]. Although the dispersion stability and chemical reaction mechanisms of these 2D materials as lubricants require further investigation [43], their excellent lubrication properties under extreme operating conditions (e.g., high temperature, high pressure, and high speed) have garnered increasing research interest and attention [44,45,46]. Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets, with their weakly bonded multilayer structure and self-lubricating properties, hold significant promise in the field of lubricants [47,48,49]. For instance, Rosenkranz et al. [50] investigated the effect of Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets on the friction and wear properties of highly loaded steel/steel dry sliding under varying contact pressures and relative humidity levels. They found that Ti3C2Tx MXene-coated samples exhibited a 2.3-fold reduction in friction and a 2.7-fold reduction in wear under moderate contact pressure and low relative humidity conditions. Additionally, the Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheet layers are connected by relatively weak van der Waals forces, allowing the nanosheets to slip easily under friction, a unique property beneficial for lubrication [51,52]. Despite these advantages, Ti3C2Tx MXene still faces several challenges as a lubricant [53,54]. Firstly, its compatibility with different materials requires further exploration [55]. Secondly, its long-term stability needs improvement [54]. Many researchers have attempted to use Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets as lubricant additives to enhance friction performance by leveraging their excellent mechanical properties. However, Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets often exhibit poor dispersion in most base oils, limiting their effectiveness in improving friction performance [56,57,58]. Addressing these challenges will be crucial for unlocking the full potential of Ti3C2Tx MXene in lubrication applications.

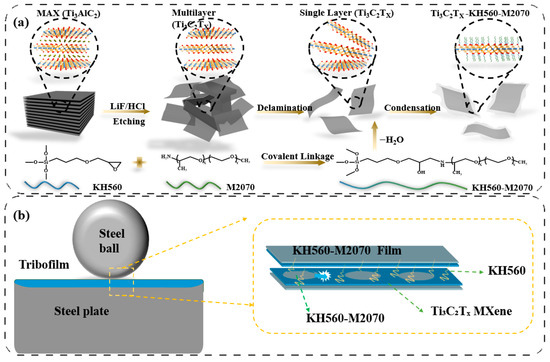

In this study, a novel MXene-based solvent-free nanofluid lubricant was successfully designed and synthesized. As illustrated in Scheme 1a, the lubricant features a distinctive “core-neck-crown” architecture comprising three essential components: Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets serving as the structural core, the coupling agent γ-(2,3-epoxypropoxy)propyltrimethoxysilane (KH560) as an intermediate layer, and the amphiphilic polyether amine M2070 as the fluid canopy. This design concept shares similarities with solvent-free graphene lubricants, where functionalized graphene cores are typically grafted with organic coronas to achieve fluidity. However, unlike graphene-based systems that rely primarily on physical adsorption films and low interlayer shear, the MXene-based nanofluid exhibits a more sophisticated lubrication mechanism. As depicted in Scheme 1b, the Ti3C2Tx nanosheets not only facilitate interlayer sliding but also participate in the formation of a tribofilm enriched with Ti–O–C components, thereby enhancing interfacial adhesion and load-bearing capacity. Simultaneously, the KH560-M2070 polymer architecture enables rapid repair of damaged nanosheet structures. To evaluate the tribological performance, lubricants with MXene concentrations of 0.3 wt.%, 1.0 wt.%, and 2.5 wt.% were prepared and tested. CLSM analysis of the wear scars demonstrated that both the friction coefficient and wear decreased significantly with increasing MXene concentration under constant load. These findings confirm that the MXene-based nanofluid effectively integrates the self-lubricating characteristics of solid lubricants with the fluidity and self-healing capabilities of liquid lubricants, providing a robust and scalable strategy for developing high-performance lubricants suitable for demanding tribological conditions.

Scheme 1.

Diagram of (a) the preparation process and (b) the proposed lubrication mechanism of the MXene-based solvent-free nanofluid lubricant (Ti3C2Tx-KH560-M2070).

2. Result and Discussion

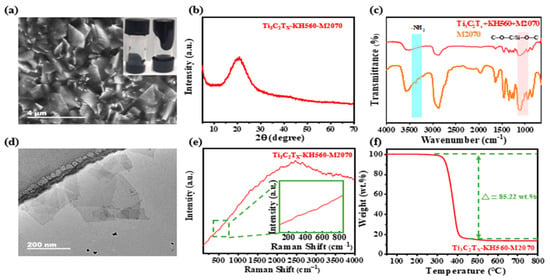

Initially, the Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets obtained through etching exhibit a thin and lightweight sheet-like structure, as confirmed by SEM (Figure 1a) and TEM (Figure 1d) images. The XRD spectra of the precursor MAX-phase Ti3AlC2 powder before and after etching in the LiF/HCl mixture are shown in Figure 1b. After etching, the (002) diffraction peaks of Ti3AlC2 shift to a lower angle, and the strong diffraction peak at 39° disappears, indicating the selective removal of the Al atomic layer from the Ti3AlC2 structure [59,60]. ATR-IR spectroscopy (Figure 1c) reveals the presence of abundant hydroxyl groups on the surface of the Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets, which is crucial for subsequent covalent grafting. The Raman spectrum in Figure 1e shows that Ti3AlC2 exhibits features similar but not identical to those previously reported [61], likely due to variations in the type of MAX products received from different suppliers [62]. The TGA curves (Figure 1f) show no significant mass loss up to 800 °C, confirming that the Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets are free of volatile solvents. These results demonstrate the successful preparation of Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets that meet the experimental requirements, providing a solid foundation for further modification and covalent grafting of organic oligomers.

Figure 1.

Characterization of the Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets. (a) SEM, (b) XRD pattern, (c) ATR-IR spectrum, (d) TEM, (e) Raman spectrum, and (f) TGA traces under N2 atmosphere at 5 °C/min, respectively.

In Figure 2a, the prepared MXene-based solvent-free nanofluid is dispersed in a continuous medium and exhibits excellent flowability at room temperature. In contrast to the Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets, the XRD pattern of the MXene-based solvent-free nanofluid (Figure 2b) reveals a distinct peak at 20°, attributed to the organic oligomers grafted onto the surface of the nanosheets [63]. The ATR-IR analysis (Figure 2c) confirms the successful covalent functionalization of Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets. Significant spectral modifications are observed in the functionalized nanofluid compared to the pristine MXene. The emergence of characteristic C–H stretching vibrations at 2920 cm−1 and 2850 cm−1 provides clear evidence for the incorporation of organic constituents from KH560 and M2070. The spectral changes in the 3400 cm−1 region, coupled with the appearance of an amide-related absorption at 1640 cm−1, indicate the consumption of amine groups in M2070 through epoxy ring-opening with KH560. Additionally, the pronounced broad absorption between 1000 and 1100 cm−1, corresponding to Si–O–C and C–O–C stretching modes, verifies the covalent linkage established between the MXene sheets and the polymer canopy via the silane coupling agent. These collective spectroscopic findings substantiate the successful construction of the targeted “core–neck–crown” configuration through covalent surface modification. However, the characteristic peaks of the -NH2 group around 3400 cm−1 disappear, likely due to the epoxy ring-opening covalent reaction with KH560 [64]. This reaction forms a stable “core–neck–crown” architecture in which the KH560–M2070 polymer shell creates a compact protective layer around the MXene nanosheets. The shell effectively blocks thermal and oxidative attack, thereby significantly delaying the degradation of the MXene core. This protective effect is directly evidenced by the TEM image obtained after three months of storage (Figure 2d), where the nanosheets retain their structural integrity without observable oxidation. The suppression of MXene-related Raman features in Figure 2e also indirectly reflects the complete encapsulation by the organic coating. TGA (Figure 2f) provides quantitative support for this protection mechanism: the major mass loss of ~85.22 wt.% corresponds to decomposition of the polymer shell, which may consume local oxygen and generate a thin carbonaceous layer that further protects the MXene surface. Consequently, the sample maintains ~15 wt.% residual mass even at 800 °C, demonstrating the remarkable thermal stability endowed by the composite structure.

Figure 2.

Characterization of the MXene-based solvent-free nanofluid (Ti3C2Tx-KH560-M2070). (a) SEM (The inner picture shows the optical photograph of the MXene-based solvent-free nanofluid), (b) XRD pattern, (c) ATR-IR spectrum, (d) TEM, (e) Raman spectra (the green frame shows a partial enlargement), and (f) TGA traces under N2 atmosphere at 5 °C/min, respectively.

The prepared MXene-based solvent-free nanofluid demonstrates excellent stability and fluidity at room temperature, making it a promising candidate for use as a novel lubricant (i.e., MXene-based solvent-free nanofluid lubricant). The tribological properties of this lubricant were tested at three different concentrations of Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets: 0.3 wt.%, 1.0 wt.%, and 2.5 wt.%. Figure 3a provides a schematic of the tribometer setup used for friction testing. Figure 3b–d display the friction coefficients of the MXene-based solvent-free nanofluid lubricants with varying Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheet concentrations (0.3 wt.%, 1.0 wt.%, and 2.5 wt.%) under applied loads of 1 N, 3 N, and 5 N. A clear trend is observed: the stable friction coefficients of the MXene-based solvent-free nanofluid lubricants decrease as the concentration of Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets increases, regardless of the applied load. For example, under a 1 N load, the stable friction coefficients are approximately 0.032 (0.3 wt.%), 0.030 (1.0 wt.%), and 0.028 (2.5 wt.%). This trend of decreasing friction coefficients with increasing nanosheet concentration is consistent across all tested loads (1 N, 3 N, and 5 N). Furthermore, the stable friction coefficients also decrease as the applied load increases. The lowest friction coefficient, approximately 0.022, is achieved with the 2.5 wt.% Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets concentration under a 5 N load, as illustrated in Figure 3d. These results highlight the effectiveness of the MXene-based solvent-free nanofluid lubricant in reducing friction under varying conditions.

Figure 3.

(a) Schematic working diagram of the tribometer and (b–d) The friction coefficients of the MXene-based solvent-free nanofluid lubricants with different concentrations of Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets and varied applied loads of 1 N, 3 N, and 5 N.

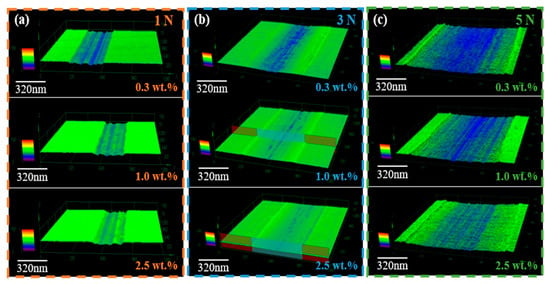

The wear morphology of steel plates lubricated with the MXene-based solvent-free nanofluid under varying applied loads was characterized using Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM). As illustrated in Figure 4a–c, under loads of 1 N, 3 N, and 5 N, the wear scars consistently became shallower and narrower with increasing mass concentration of Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets, indicating a clear correlation between nanosheet concentration and enhanced anti-wear performance. This improvement stems from the synergistic behavior of the nanofluid’s multi-component architecture: the Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets act as a solid lubricant by promoting interlayer shear and in situ formation of a protective tribofilm, while the fluid polyether amine canopy (M2070) ensures low shear stress and rapid replenishment of wear zones. The KH560 coupling agent covalently links the MXene and polymer, reinforcing the structural integrity and enabling a robust, adaptive, and self-repairing lubricating system. Together, these features allow the nanofluid to spread uniformly, maintain a continuous lubricating film, and rapidly recover damaged areas, thereby stabilizing the friction coefficient and combining the key advantages of solid and liquid lubricants for effective friction and wear reduction.

Figure 4.

CLSM was used to characterize the wear morphology of the MXene-based solvent-free nanofluid lubricants with different concentrations of Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets. The applied loads are (a) 1 N, (b) 3 N, and (c) 5 N, respectively.

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Materials

Layered ternary carbide (Ti3AlC2) MAX phase powder with a 200-mesh size was purchased from Forsman Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). The organosilane coupling agent γ-(2,3-epoxypropoxy) propyltrimethoxysilane (KH560, AR, 98%) and lithium fluoride (LiF, ≥98%) were obtained from Aladdin Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Polyether amine M2070 was supplied by Dalian Liansheng Trading Co., Ltd. (Dalian, China). Concentrated hydrochloric acid was purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All chemicals were used as received without further purification.

3.2. Preparation of Ti3C2Tx MXene Nanosheets

The conventional two-step method for obtaining Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets, which was adopted in the study reported here, involves etching the aluminum atomic layer from the MAX phase using HF acid. As illustrated in Scheme 1, 15 mL of 12 mol/L HCl was first mixed with 5 mL of deionized water to prepare 20 mL of a 9 mol/L HCl solution. Next, 1.6 g of LiF was slowly added to the diluted HCl solution and stirred for 10 min using a Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) magnetic stirrer. Afterward, 1 g of Ti3AlC2 powder was gradually introduced into the HCl/LiF mixture. The mixture was allowed to react at 35 °C for 24 h under continuous stirring. Once the reaction was complete, the mixture was centrifuged with deionized water at 4000 rpm until the supernatant reached a neutral pH. The resulting product was then sonicated for 1 h under nitrogen protection to exfoliate the MXene layers. Finally, the mixture was centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 30 min to isolate few-layer or monolayer Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets in an aqueous solution. This solution was subsequently used as the base material for preparing the nanofluids in this study.

3.3. Synthesis of the MXene-Based Solvent-Free Nanofluid Lubricant (Ti3C2Tx-KH560-M2070)

In the preparation process, 10 g of M2070 and an equimolar amount of KH560 were dissolved in 100 mL of methanol. The solution was then subjected to condensation and reflux at a constant temperature of 45 °C for 12 h. Following this, an aqueous solution of Ti3C2Tx MXene (50 mg/mL) was added to the KH560-M2070 methanol solution, and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for an additional 12 h. The resulting dispersion was transferred into a dialysis bag with a molecular weight cut-off of 5000 and dialyzed for 2 days, with the deionized water being replaced 4–6 times during this period. After dialysis, the excess water in the dispersion was removed using rotary evaporation. This process yielded the final product: a MXene-based solvent-free nanofluid lubricant (Ti3C2Tx-KH560-M2070).

3.4. Characterization

The attenuated total reflection infrared (ATR-IR) spectra were acquired using a Nicolet iS50 intelligent ATR-IR spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with a spectral range of 500–4000 cm−1. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were captured at an accelerating voltage of 5 kV. For transmission electron microscopy (TEM) imaging, a sample dispersion (5 mg/mL) was drop-cast onto carbon-coated copper grids and allowed to dry naturally at room temperature before imaging at 120 kV. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was conducted using a Q50 TA instrument under a nitrogen atmosphere, with a heating rate of 5 °C/min. Raman spectroscopy measurements of Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets and the MXene-based solvent-free nanofluid lubricant were performed using a 532 nm laser (Renishaw inVia, Pliezhausen, Germany). Friction and wear tests were conducted using a Tribometer (Center for Tribology, Campbell, CA, USA), while wear scar characterization was performed using a Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope (CLSM, Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The wear tests employed a ball-on-disk configuration (CSM tribometer (TRB-III), Jinan Zhongwei Casting and Forging Grinding Ball Co., Ltd., Jinan, China), where the friction and wear behavior of a steel plate coated with the MXene-based solvent-free nanofluid lubricant was evaluated against a steel ball (AISI 52100 steel, 6 mm diameter, Ra ≈ 20 nm, Jinan Zhongwei Casting and Forging Grinding Ball Co., Ltd., Jinan, China) in a linear reciprocating motion. Prior to testing, the 304 stainless steel plate was polished, cleaned, and coated with the MXene-based solvent-free nanofluid lubricant. The tests were conducted under applied loads of 1 N, 3 N, and 5 N at a constant sliding speed of 60 mm/s, a wear track length of 10 mm, and a test duration of 30 min. All tribological measurements were performed under ambient conditions of 25 ± 2 °C and 45 ± 5% relative humidity. After the tests, the morphology of the wear scars on the 304 stainless steel plate was analyzed using CLSM.

4. Conclusions

In the study reported here, a MXene-based solvent-free nanofluid was successfully developed through the surface functionalization of Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets using the coupling agent γ-(2,3-epoxypropoxy) propyltrimethoxysilane (KH560) and the amphiphilic long-chain liquid polyether amine M2070, constructing a distinctive “core–neck–crown” architecture. The resulting nanofluid exhibits excellent stability and fluidity at room temperature, making it suitable for use as a novel lubricant. Subsequent tribological characterization revealed that both the stable friction coefficients and wear decrease significantly with increasing mass fraction of Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets under varying applied loads, indicating outstanding friction-reduction and anti-wear performance. More importantly, integrated structural and tribological analysis reveals a solid–liquid synergistic lubrication mechanism during sliding: the MXene nanosheets, serving as the solid lubricating core, form a protective tribofilm with low shear strength due to their facile interlayer slip, while the outer M2070 liquid polymer provides fluid lubrication and flexible cushioning, enabling rapid replenishment of worn areas. Covalently linked by KH560, these two components form a stable hybrid, resulting in a continuous, flexible, and self-repairing composite lubrication film at the friction interface. This solid–liquid synergy is identified as the fundamental reason for the superior tribological performance.

The findings of this work demonstrate that the MXene-based solvent-free nanofluid lubricant not only effectively reduces friction and wear but also overcomes the drawbacks of conventional MXene additives in oil-based systems, such as poor stability and agglomeration, while exhibiting the potential to combine the advantages of both solid and liquid lubricants. This study thereby offers a viable route for developing high-performance lubricating materials capable of operating under demanding industrial conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.Z., X.L. and H.L.; Methodology, J.X., Y.Z., M.Z., J.W., L.L. and H.L.; Validation, X.L., J.X., M.Z., J.W., L.L. and H.L.; Formal analysis, W.Z., L.L., H.L. and P.L.; Investigation, W.Z., X.L., J.W., L.L., H.L. and P.L.; Resources, W.Z., X.L., J.X., Y.Z., M.Z., J.W., L.L., H.L. and P.L.; Data curation, X.L., J.X., Y.Z., M.Z., J.W., L.L., H.L. and P.L.; Writing—original draft, W.Z.; Writing—review and editing, W.Z. and P.L.; Supervision, W.Z. and P.L.; Project administration, W.Z. and P.L.; Funding acquisition, W.Z. and P.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Key Core Technology Research Project of China Petroleum (No. 2022-ZG15), Key Science and Technology Projects for Basic and Prospective Research of CNPC (No. 2023ZZ11), CNPC Youth Science and Technology Special Project (No. 2024DQ03122), Key Research and Development Program of Shaanxi (No. 2024GX-YBXM-391), the Shaanxi Fundamental Science Research Project for Chemistry & Biology (No. 22JHQ023). The authors also acknowledge the support from the State Key Laboratory of Oil and Gas Equipment.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Xuwu Luo, Junfeng Xie, Yaoming Zhang, Mifeng Zhao and Junhui Wei were employed by the company PetroChina Tarim Oilfield Company, Korla, China. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Benarbia, A.; Tomomewo, O.S.; Laalam, A.; Khalifa, H.; Bertal, S.; Abadli, K. Enhancing Wear Resistance of Drilling Motor Components: A Tribological and Materials Application Study. Eng 2024, 5, 566–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, K.; Kivikytö-Reponen, P.; Härkisaari, P.; Valtonen, K.; Erdemir, A. Global energy consumption due to friction and wear in the mining industry. Tribol. Int. 2017, 115, 116–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, Q.U.; Zhao, Y.; Zaman, S.; Batool, K.; Nasir, R. Reviewing energy efficiency and environmental consciousness in the minerals industry Amidst digital transition: A comprehensive review. Resour. Policy 2024, 91, 104851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, K.; Andersson, P.; Erdemir, A. Global energy consumption due to friction in passenger cars. Tribol. Int. 2012, 47, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramendia, E.; Brockway, P.E.; Taylor, P.G.; Norman, J. Global energy consumption of the mineral mining industry: Exploring the historical perspective and future pathways to 2060. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2023, 83, 102745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Garabedian, N.; Schneider, J.; Greiner, C. Waviness Affects Friction and Abrasive Wear. Tribol. Lett. 2023, 71, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartz, W.J. Lubricants and the environment. Tribol. Int. 1998, 31, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uniyal, P.; Gaur, P.; Yadav, J.; Khan, T.; Ahmed, O.S. A Review on the Effect of Metal Oxide Nanoparticles on Tribological Properties of Biolubricants. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 12436–12456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, J.H.; Li, Y.F.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Wang, Y.M.; Wang, Y.J. High-Temperature Solid Lubricants and Self-Lubricating Composites: A Critical Review. Lubricants 2022, 10, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Liu, S.; Ji, Z.; Guo, R.; Sun, C.; Guo, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, Q. 3D printing of PTFE-filled polyimide for programmable lubricating in the region where lubrication is needed. Tribol. Int. 2022, 167, 107405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.A.A.A.; Takhakh, A.M.; Al-Waily, M. A review of use of nanoparticle additives in lubricants to improve its tribological properties. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 52, 1442–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakabayashi, T.; Williams, J.; Hutchings, I. The action of gaseous lubricants in the orthogonal machining of an aluminium alloy by titanium nitride coated tools. Surf. Coat. Technol. 1993, 57, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, K.; Liu, G. Drag reduction by gas lubrication with bubbles. Ocean Eng. 2022, 258, 111833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanola, A.; Gajrani, K.K. Novel insights into graphene-based sustainable liquid lubricant additives: A comprehensive review. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 386, 122523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresme, F.; Kornyshev, A.A.; Perkin, S.; Urbakh, M. Electrotunable friction with ionic liquid lubricants. Nat. Mater. 2022, 21, 848–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somers, A.E.; Howlett, P.C.; Macfarlane, D.R.; Forsyth, M. A Review of Ionic Liquid Lubricants. Lubricants 2013, 1, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Banga, H.K.; Singh, H.; Kundal, S. An outline on modern day applications of solid lubricants. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 28, 1962–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoi, F.C.; Bhandari, B.R.; Prakash, S. Tribo-rheology and sensory analysis of a dairy semi-solid. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 70, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Islam, M.; Roy, R.; Younis, H.; AlNahyan, M.; Younes, H. Carbon Nanomaterial-Based Lubricants: Review of Recent Developments. Lubricants 2022, 10, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharf, T.W.; Prasad, S.V. Solid lubricants: A review. J. Mater. Sci. 2012, 48, 511–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnet, C.; Erdemir, A. Solid Lubricant Coatings: Recent Developments and Future Trends. Tribol. Lett. 2004, 17, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilbag, S.; Rao, P.V. Performance improvement of hard turning with solid lubricants. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2008, 38, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Qu, J. Ionic Liquids as Lubricant Additives: A Review. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 3209–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Liang, Y.; Liu, W. Ionic liquid lubricants: Designed chemistry for engineering applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 2590–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Li, S. A review of recent developments of friction modifiers for liquid lubricants (2007–present). Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2014, 18, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Yu, Q.; Liu, W.; Zhou, F. Ionic liquid lubricants: When chemistry meets tribology. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 7753–7818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Yao, D.; Wang, D.; He, Z.; Tian, X.; Xin, Y.; Su, F.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; et al. Amino-functionalized ZIFs-based porous liquids with low viscosity for efficient low-pressure CO2 capture and CO2/N2 separation. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 429, 132296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mow, R.E.; Lipton, A.S.; Shulda, S.; Gaulding, E.A.; Gennett, T.; Braunecker, W.A. Colloidal three-dimensional covalent organic frameworks and their application as porous liquids. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 23455–23462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavykina, A.; Cadiau, A.; Gascon, J. Porous liquids based on porous cages, metal organic frameworks and metal organic polyhedra. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 386, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, X.; Yang, Z.; Wang, D.; Duan, X.; Xin, Y.; Zhu, H.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Yao, D.; Zheng, Y. Expanding the gallery of solvent-free nanofluids: Using layered double hydroxides as core nanostructures. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 455, 140797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, P.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Tang, J.; Liu, H.; Shao, Q.; Ding, T.; Umar, A.; Guo, Z. Solvent-free graphene liquids: Promising candidates for lubricants without the base oil. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 542, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Schott, J.A.; Zhang, J.; Mahurin, S.M.; Sheng, Y.; Qiao, Z.A.; Hu, X.; Cui, G.; Yao, D.; Brown, S.; et al. Electrostatic-Assisted Liquefaction of Porous Carbons. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 129, 15154–15158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos-Leal, E.L.; Osuna-Zatarain, A.; Garcia-Garcia, A. Frictional Properties of Two-Dimensional Nanomaterials as an Additive in Liquid Lubricants: Current Challenges and Potential Research Topics. Lubricants 2023, 11, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Liu, S. 2D nanomaterials as lubricant additive: A review. Mater. Des. 2017, 135, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Gao, T.; Li, Y.; He, Y.; Shi, Y. Two-dimensional (2D) graphene nanosheets as advanced lubricant additives: A critical review and prospect. Mater. Today Commun. 2021, 29, 102755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, P.; Lei, Y.; Li, W.; Fan, M. Two-dimension layered nanomaterial as lubricant additives: Covalent organic frameworks beyond oxide graphene and reduced oxide graphene. Tribol. Int. 2020, 143, 106051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Chen, G.; He, Y.; Li, S.; Duan, Z.; Li, Y.; Luo, J. A novel route to the synthesis of an Fe3O4/h-BN 2D nanocomposite as a lubricant additive. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 6583–6588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miró, P.; Audiffred, M.; Heine, T. An atlas of two-dimensional materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 6537–6554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.X.; Liu, S.; Yan, C.; Wang, X.J.; Wang, L.; Yu, Y.M.; Li, S.Y. Abrasion properties of self-suspended hairy titanium dioxide nanomaterials. Appl. Nanosci. 2017, 7, 691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ren, T.; Li, Z. Recent advances of two-dimensional lubricating materials: From tunable tribological properties to applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 11, 9239–9269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spear, J.C.; Ewers, B.W.; Batteas, J.D. 2D-nanomaterials for controlling friction and wear at interfaces. Nano Today 2015, 10, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, Y. Superlubricity achieved with two-dimensional nano-additives to liquid lubricants. Friction 2020, 8, 1007–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.L.; Cao, Y.; Tian, P.; Guo, F.; Tian, Y.; Zheng, W.; Ji, X.; Liu, J. Soluble, Exfoliated Two-Dimensional Nanosheets as Excellent Aqueous Lubricants. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 32440–32449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, S.; Wang, W. Nanodiamond plates as macroscale solid lubricant: A “non-layered” two-dimension material. Carbon 2022, 198, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha-Tijerina, J.; Peña-Paras, L.; Narayanan, T.; Garza, L.; Lapray, C.; Gonzalez, J.; Palacios, E.; Molina, D.; García, A.; Maldonado, D.; et al. Multifunctional nanofluids with 2D nanosheets for thermal and tribological management. Wear 2013, 302, 1241–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhang, F.; Yang, K.; Xiong, Y.; Tang, J.; Chen, H.; Duan, M.; Li, Z.; Zhang, H.; Xiong, B. Review of two-dimensional nanomaterials in tribology: Recent developments, challenges and prospects. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 321, 103004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naguib, M.; Mochalin, V.N.; Barsoum, M.W.; Gogotsi, Y. 25th Anniversary Article: MXenes: A New Family of Two-Dimensional Materials. Adv. Energy Mater. 2014, 26, 992–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anasori, B.; Lukatskaya, M.R.; Gogotsi, Y. 2D metal carbides and nitrides (MXenes) for energy storage. In MXenes; Jenny Stanford Publishing: Singapore, 2023; pp. 677–722. [Google Scholar]

- Ran, J.; Gao, G.; Li, F.T.; Ma, T.Y.; Du, A.; Qiao, S.Z. Ti3C2 MXene co-catalyst on metal sulfide photo-absorbers for enhanced visible-light photocatalytic hydrogen production. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 13907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marian, M.; Song, G.C.; Wang, B.; Fuenzalida, V.M.; Krauß, S.; Merle, B.; Tremmel, S.; Wartzack, S.; Yu, J.; Rosenkranz, A. Effective usage of 2D MXene nanosheets as solid lubricant–Influence of contact pressure and relative humidity. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 531, 147311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, C.Y.; Kan, C.W.; Mak, C.L.; Chau, K.H. Flexible Energy Storage System—An Introductory Review of Textile-Based Flexible Supercapacitors. Processes 2019, 7, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, W.; Mai, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, L.; Li, S.; Jie, X. Two-dimensional Ti3C2 coating as an emerging protective solid-lubricant for tribology. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 20154–20162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronchi, R.M.; Arantes, J.T.; Santos, S.F. Synthesis, structure, properties and applications of MXenes: Current status and perspectives. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 18167–18188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boidi, G.; F. de Queiróz, J.C.; Profito, F.J.; Rosenkranz, A. Ti3C2Tx MXene Nanosheets as Lubricant Additives to Lower Friction under High Loads, Sliding Ratios, and Elevated Temperatures. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 6, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Du, C.F.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, X.; Ye, Q.; Liu, S.; Liu, W. Dialkyl Dithiophosphate-Functionalized Ti3C2Tx MXene Nanosheets as Effective Lubricant Additives for Antiwear and Friction Reduction. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 11080–11087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, M.; Tremmel, S.; Wartzack, S.; Song, G.; Wang, B.; Yu, J.; Rosenkranz, A. Mxene nanosheets as an emerging solid lubricant for machine elements–Towards increased energy efficiency and service life. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 523, 146503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xue, S.; Yan, Y.; Bai, W.; Du, C.F.; Liu, S.; Ye, Q.; Zhou, F. Zwitterionic polymer-functionalized nitrogen-doped MXene nanosheets as aqueous lubricant additive. Tribol. Int. 2023, 186, 108625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Li, T.; Li, W.; Tang, H.; Zhang, L.; Yu, Y.; Qiao, Z. Ti3C2Tx MXenes–An effective and long-storable oil lubricant additive. Tribol. Int. 2023, 180, 108273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Wei, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Caro, J.; Wang, H. A Two-Dimensional Lamellar Membrane: MXene Nanosheet Stacks. Angewandte Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 1825–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naguib, M.; Kurtoglu, M.; Presser, V.; Lu, J.; Niu, J.; Heon, M.; Hultman, L.; Gogotsi, Y.; Barsoum, M.W. Two-dimensional nanocrystals produced by exfoliation of Ti3AlC2. In MXenes; Jenny Stanford Publishing: Singapore, 2023; pp. 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.; Bati, A.S.R.; Grace, T.S.L.; Batmunkh, M.; Shapter, J.G. Ti3C2Tx (MXene)-Silicon Heterojunction for Efficient Photovoltaic Cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 1901063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarycheva, A.; Gogotsi, Y. Raman spectroscopy analysis of the structure and surface chemistry of Ti3C2Tx MXene. In MXenes; Jenny Stanford Publishing: Singapore, 2023; pp. 333–355. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Gao, Q.; Hou, K.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Yang, S. Solvent-free covalent MXene nanofluid: A new lubricant combining the characteristics of solid and liquid lubricants. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Xin, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zheng, Y.; Yao, D.; Yang, Z.; Lei, X. A universal approach to turn UiO-66 into type 1 porous liquids via post-synthetic modification with corona-canopy species for CO2 capture. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 416, 127625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.