Abstract

As part of our interest in the volatile phytoconstituents of aromatic plants of the Great Basin, we have obtained essential oils of Ambrosia acanthicarpa (three samples), Artemisia ludoviciana (12 samples), and Gutierrezia sarothrae (six samples) from the Owyhee Mountains of southwestern Idaho. Gas chromatographic analyses (GC-MS, GC-FID, and chiral GC-MS) were carried out on each essential oil sample. The essential oils of A. acanthicarpa were dominated by monoterpene hydrocarbons, including α-pinene (36.7–45.1%), myrcene (21.6–25.5%), and β-phellandrene (4.9–7.0%). Monoterpene hydrocarbons also dominated the essential oils of G. sarothrae, with β-pinene (0.5–18.4%), α-phellandrene (2.2–11.8%), limonene (1.4–25.4%), and (Z)-β-ocimene (18.8–39.4%) as major components. The essential oils of A. ludoviciana showed wide variation in composition, but the relatively abundant compounds were camphor (0.1–61.9%, average 14.1%), 1,8-cineole (0.1–50.8%, average 11.1%), (E)-nerolidol (0.0–41.0%, average 6.8%), and artemisia ketone (0.0–46.1%, average 5.1%). This is the first report on the essential oil composition of A. acanthicarpa and the first report on the enantiomeric distribution in an Ambrosia species. The essential oil compositions of A. ludoviciana and G. sarothrae showed wide variation in composition in this study and compared with previous studies, likely due to subspecies variation.

Keywords:

ragweed; burweed; bur-sage; white sage; silver wormwood; broom snakeweed; gas chromatography; enantiomers 1. Introduction

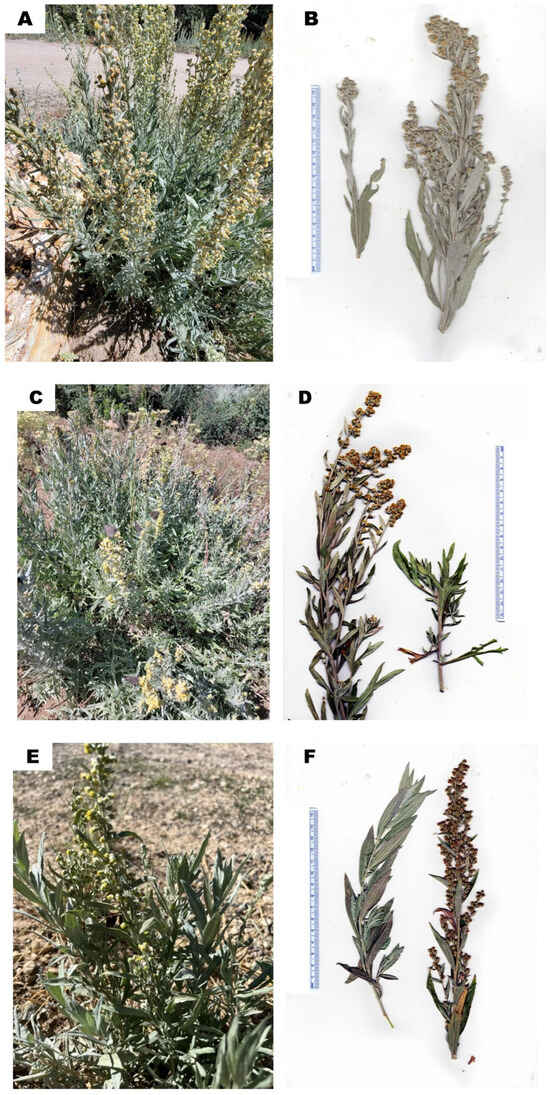

Ambrosia acanthicarpa Hook. (bur ragweed, burweed, bur-sage) is an annual member of the Asteraceae. The leaves are deltoid to narrowly lanceolate, to 8 cm long and 6 cm wide, pinnately to tripinnately lobed, and both leaf surfaces are green and have a dense covering of short, matted hairs [1]. The stems are grayish-green, with stiff, bristly hairs (Figure 1). In the United States, the plant ranges from eastern Washington and Oregon, eastern and southern California, east to western North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, and Kansas, and the panhandle of Texas [1].

Figure 1.

Ambrosia acanthicarpa. (A): Photograph of A. acanthicarpa (K. Swor). (B): Scan of pressed plant (W.N. Setzer).

Previous phytochemical investigations of A. acanthicarpa have revealed the plant to be a source of sesquiterpene lactones, including artemisiifolin, chamissonin, psilostachyin C, confertiflorin, deacetylconfertiflorin, and cumambrin B [2,3]. As far as we are aware, there have been no previous studies on the essential oil of this plant.

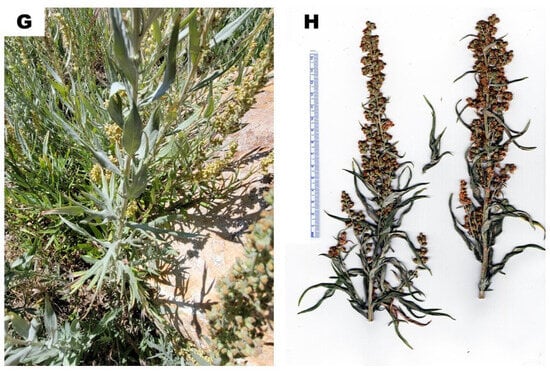

Artemisia ludoviciana Nutt. (white sage, silver wormwood, Asteraceae) is a perennial herb, 30–70 cm tall, with a sagebrush odor. The leaves are alternate, entire, or lobed, 3–11 cm long, and up to 1.5 cm wide, with a dense covering of short, matted hairs. The plant flowers from August through September, producing numerous nodding flower heads (Figure 2) [4,5]. The plant is highly polymorphic and there are several subordinate taxa. World Flora Online currently lists seven subspecies, including Artemisia ludoviciana subsp. albula (Wooton) D.D. Keck, Artemisia ludoviciana subsp. candicans (Rydb.) D.D. Keck, Artemisia ludoviciana subsp. incompta (Nutt.) D.D. Keck, Artemisia ludoviciana subsp. lindleyana (Besser) Lesica, Artemisia ludoviciana subsp. ludoviciana, Artemisia ludoviciana subsp. mexicana (Spreng.) D.D. Keck, and Artemisia ludoviciana subsp. redolens (A. Gray) D.D. Keck. [6]. Of these, A. ludoviciana subsp. ludoviciana [7], A. ludoviciana subsp. candicans [8], and A. ludoviciana subsp. incompta [9] are known to occur in Idaho. However, these subspecies are variable morphologically, intergrade between taxa, and recognition of the discreet taxa is therefore difficult and questionable. Artemisia ludoviciana is widespread throughout western North America, ranging from Ontario and Michigan, west to British Columbia, and south through Texas, Louisiana, California, and Mexico [4,5].

Figure 2.

Artemisia ludoviciana. (A): Photograph of A. ludoviciana, plant B1 (K. Swor). (B): Scan of pressed plant B1 (W.N. Setzer). (C): Photograph of A. ludoviciana, plant C1 (K. Swor). (D): Scan of pressed plant C1 (W.N. Setzer). (E): Photograph of A. ludoviciana, plant T1 (K. Swor). (F): Scan of pressed plant T1 (W.N. Setzer). (G): Photograph of A. ludoviciana, plant U1 (K. Swor). (H): Scan of pressed plant U1 (W.N. Setzer).

The plant is used in traditional herbal medicine throughout its range. In Mexico, the people use an infusion of the aerial parts of A. ludoviciana to treat diarrhea, parasitic diseases, painful conditions, and diabetes [10,11]. In the Great Basin of North America, the Paiute people used a decoction of A. ludoviciana as a bath for aching feet, as a poultice for rheumatism or other aches, to treat rashes and skin eruptions, and to relieve diarrhea, while the Shoshone took the plant for coughs, colds, and influenza, and to stop diarrhea [12].

Artemisia ludoviciana has proven to be a rich source of sesquiterpene lactones, including ludovicin-A, -B, -C, and -D [13], ludalbin [14], anthemidin [15], arteludovicinolide-A, -B, -C, and -D [16], douglanin, santamarin, arglanine, artemorin, chrysartemin B, armefolin, and ridentin [17]; flavonoids, including jaceosidin, tricin, hispidulin, chrysoeriol, apigenin, axillarin, eupafolin, selagin, luteolin [18], eupatilin, and jaceosidin [17]; and the spiroketals 2-(2-thienylidene)-1,6-dioxaspiro[4.5]dec-3-ene and 5-[[5-(1,6-dioxaspiro[4.5]dec-3-en-2-ylidenemethyl)-2-thienyl]-2-thienylmethyl]-2-furanbutanol [19]. There have been previous investigations on the essential oil composition of A. ludoviciana from different geographical locations, including Utah, USA [20], Huixquilucan, State of Mexico, Mexico [21], Alberta, Canada [22], Ozumba, State of Mexico, Mexico [23], South Dakota, USA [24], Istanbul, Türkiye (cultivated) [25], and Wyoming, USA [26].

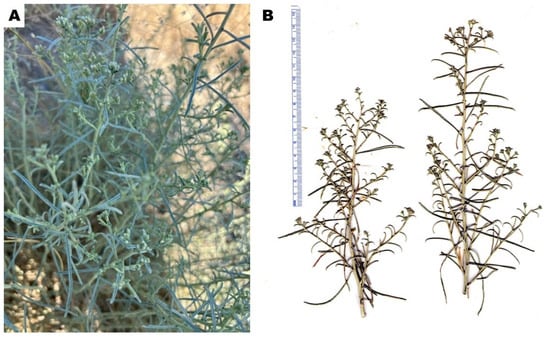

Gutierrezia sarothrae (Pursh) Britton & Rusby (syn. Xanthocephalum sarothrae (Pursh) Shinners, broom snakeweed, Asteraceae) is an herbaceous shrub, 10–60 cm in height; stems are green to brown; leaves are alternate, lanceolate, sometimes filiform, green, up to 4–55 mm long, and 0.3–5 mm wide (Figure 3). The plant flowers July-November, producing numerous small, bright-yellow flowers [27,28,29]. Gutierrezia sarothrae ranges throughout western North America, from eastern Oregon and Washington, eastern and southern California east to the Great Plains, and from southern Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba, south into northern Mexico [27,30].

Figure 3.

Gutierrezia sarothrae. (A): Photograph of G. sarothrae (K. Swor). (B): Scan of pressed plant (W.N. Setzer).

Diterpenoids, including polyalthic acid, daniellic acid, nivenolide, and gutierrezial [31,32,33], and flavonoids, including apigenin, luteolin, calycopterin, jaceidin, sudachitin, and sarothrin [34], have been isolated and characterized from G. sarothrae extracts. The plant is an invasive weed and there have been several reports on the toxic effects of livestock grazing on G. sarothrae, causing abortions [30]. The abortifacient compounds in G. sarothrae are not known, but diterpene acids may be responsible [30]. There have been previous investigations of the essential oil composition of G. sarothrae from New Mexico and from Utah, USA [35,36,37].

As part of our ongoing efforts to obtain and characterize essential oils from the Asteraceae of the Great Basin [38], the purpose of this study is to obtain and chemically characterize the essential oils of A. acanthicarpa, A. ludoviciana, and G. sarothrae from southwestern Idaho. Although there have been previous investigations on the essential oils of A. ludoviciana and G. sarothrae, this present study is focused on the species from southwestern Idaho and also includes enantioselective gas chromatographic analyses to determine the enantiomeric distributions of chiral terpenoid constituents in these essential oils.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Ambrosia acanthicarpa

Hydrodistillation of the aerial parts of A. acanthicarpa yielded salmon-colored essential oils with a fish-like odor in yields of 4.36–5.01%. Gas chromatographic analysis led to identification of 135 components representing 97.6–98.0% of the total compositions (Table 1). Monoterpene hydrocarbons dominated the essential oils with α-pinene (36.7–45.1%), myrcene (21.6–25.5%), and β-phellandrene (4.9–7.0%) as the major components.

Table 1.

Chemical composition (percent of total) of the essential oil from the aerial parts of Ambrosia acanthicarpa from southwestern Idaho.

Although there have been no previous investigations of A. acanthicarpa essential oil compositions, there have been several reports on chemical compositions of other Ambrosia essential oils. Cicció and Chaverri have examined Ambrosia cumanensis Kunth from Costa Rica and have summarized the major components in Ambrosia essential oils published prior to 2015 [39]. A summary of the major components of Ambrosia essential oils published since 2015 is shown in Table 2. Ambrosia essential oils are typically dominated by sesquiterpene hydrocarbons and/or oxygenated monoterpenoids, in contrast to A. acanthicarpa, which was dominated by monoterpene hydrocarbons.

Table 2.

Major components of Ambrosia essential oils from the literature.

Enantioselective GC-MS was carried out on the three A. acanthicarpa samples (Table 3). The (−)-enantiomers were dominant for α-thujene (73.8–77.9%), α-pinene (99.3–99.4%), camphene (93.5–95.8%), β-pinene (86.5–87.9%), (E)-β-caryophyllene (100%), and germacrene D (93.5–100.0%). (+)-β-Phellandrene (97.0–98.2%), and (+)-δ-cadinene were the predominant enantiomers. Sabinene and limonene occurred in virtually racemic mixtures. Only one peak was observed for α-phellandrene (samples #2 and #3), but the RI is consistent with (+)-α-phellandrene. Likewise, only one peak was observed for lavandulol and the RI is consistent with (−)-lavandulol. One peak was observed for borneol, but the RI (1337) was in between (−)-borneol (1335) and (+)-borneol (1340), so the enantiomer cannot be assigned. Only one peak was observed for β-bisabolene, but the RI is consistent with the (+)-enantiomer. As far as we are aware, there have been no previous investigations on the enantiomeric distribution of essential oil components of Ambrosia species.

Table 3.

Enantiomeric distribution of chiral terpenoids in the essential oil from the aerial parts of Ambrosia acanthicarpa.

2.2. Artemisia ludoviciana

Essential oils from the aerial parts of A. ludoviciana were obtained from 12 individual plants in yields ranging from 0.580% to 3.306% (average yield 2.17%). Gas chromatographic analysis of the 12 A. ludoviciana essential oil samples (GC-FID, GC-MS) led to identification of 232 compounds accounting for 79.2–99.0% of the total compositions (Table 4). Although the essential oils were qualitatively similar, there were large quantitative differences in the compositions. The compounds found in relatively abundant concentrations were camphor (0.1–61.9%, average 14.1%), 1,8-cineole (0.1–50.8%, average 11.1%), (E)-nerolidol (0.0–41.0%, average 6.8%), artemisia ketone (0.0–46.1%, average 5.1%), linalool (0.1–19.9%, average 4.1%), and santolina triene (trace-18.8%, average 4.0%). There were also several unidentified components with relatively high concentrations. The mass spectra of the major unidentified compounds are available as supplementary material (Supplementary Figure S1).

Table 4.

Chemical composition (percent of total) of the essential oil from the aerial parts of Artemisia ludoviciana from the Owyhee Mountains of Idaho.

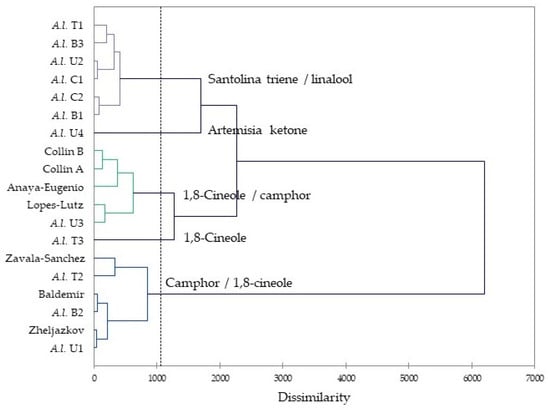

Previous investigations of A. ludoviciana essential oil showed camphor to be abundant (15.9–46.2%, average 30.0%), followed by 1,8-cineole (0.7–26.2%, average 15.2%), borneol (0.9–18.0%, average 8.5%), and α-terpineol (0.2–18.0%, average 3.3%) [21,22,23,24,25,26]. In order to place the volatile phytochemistry of this plant into perspective, an agglomerative hierarchical cluster (AHC) analysis was carried out using the major components in the essential oils from this work as well as the previously published compositions. The cluster analysis shows five possible groupings based on chemical compositions (Figure 4). The chemical groupings are (1) a santolina triene/linalool cluster, (2) a camphor/1,8-cineole cluster, (3) a 1,8-cineole “cluster” (one sample only), (4) a 1,8-cineole/camphor cluster, and (5) an artemisia ketone “cluster” (one sample only). Surprisingly, the 12 Idaho samples are distributed throughout the five clusters, demonstrating the phytochemical diversity of this plant species even within a small geographical range.

Figure 4.

Dendrogram obtained by agglomerative hierarchical cluster (AHC) analysis of Artemisia ludoviciana essential oil compositions from this work and previously published investigations (Collin A, B [24], Anaya-Eugenio [23], Lopes-Lutz [22], Zavala-Sanchez [21], Baldemir [25], Zheljazkov [26]).

Enantioselective GC-MS analyses were carried out on the 12 A. ludoviciana essential oil samples (Table 5). Pure enantiomers (enantiomeric excess, ee = 100%) were found for (−)-α-thujene, (−)-lavandulol, (−)-borneol, (−)-α-copaene, (−)-(E)-β-caryophyllene, (−)-germacrene D, and (+)-δ-cadinene. The levorotatory enantiomers predominated for α-pinene (average ee = 46.0%), camphene (average ee = 94.4%), β-pinene (average ee = 73.6%), cis-sabinene hydrate (average ee = 70.2%), and trans-sabinene hydrate (average ee = 29.9%). Several monoterpenoid constituents did not show consistent enantiomeric distribution. Sabinene was mostly dominated by (−)-sabinene, but one sample (A.l. C1) had (+)-sabinene as the major enantiomer. Likewise, (−)-terpinen-4-ol dominated most essential oil samples, but sample A.l. T2 showed a slight excess of (+)-terpinen-4-ol. Similarly, (−)-α-terpineol predominated in most samples, but sample A.l. B2 showed an excess of (+)-α-terpineol. In the case of limonene, four samples had (−)-limonene predominating, while two samples had (+)-limonene as the major enantiomer. There was no consistency in the enantiomeric distribution of linalool. In the case of camphor, (−)-camphor predominated except for one sample (A.l. T3). Note, however, that camphor was abundant in samples A.l. C2, A.l T1, A.l. T2, and A.l. U2, so separation of the enantiomers was likely not possible. A similar situation existed for (E)-nerolidol; two samples (A.l. B1 and A.l. B3) had high concentrations of (E)-nerolidol, precluding enantiomeric separation.

Table 5.

Enantiomeric distribution (percent) of chiral terpenoid components of the essential oil of Artemisia ludoviciana.

There have been several reports that investigated the enantiomeric distributions of monoterpenoids in Artemisia essential oils. Consistent with the enantiomeric distributions for α-pinene, camphene, and β-pinene, the (−)-enantiomers predominated in the essential oil of Artemisia annua L. [46] and Artemisia tridentata subsp. vaseyana (Rydb.) Beetle [47]. Limonene enantiomers were variable in A. ludoviciana (this work), but (+)-limonene was dominant in Artemisia arborescens L. [48] and (−)-limonene was dominant in A. annua [46]. Linalool enantiomeric distribution was inconsistent in A. ludoviciana (this work), while (+)-linalool predominated in A. arborescens [48,49]. (+)-Terpinen-4-ol and (−)-α-terpineol were the dominant enantiomers in A. arborescens [48,49]. Interestingly, (−)-terpinen-4-ol was the dominant enantiomer in Artemisia tridentata Nutt. subsp. tridentata and A. tridentata subsp. vaseyana, but (+)-terpinen-4-ol dominated the essential oil of Artemisia tridentata subsp. wyomingensis Beetle & A.L. Young [47]. However, (−)-α-terpineol was the dominant enantiomer in A. tridentata subsp. vaseyana [47].

Consistent with the observations in A. ludoviciana, (−)-camphor was the dominant enantiomer in A. arborescens from Algeria or southern Italy [48], Artemisia herba-alba Asso [50]. In contrast, however, (+)-camphor was the dominant enantiomer in A. arborescens from Sicily [49] and A. tridentata subsp. wyomingensis and A. tridentata subsp. vaseyana from Idaho, USA [47]. Although (−)-borneol was the only enantiomer observed in A. ludoviciana (this work) and A. tridentata subsp. wyomingensis and subsp. vaseyana [47], (+)-borneol was the dominant enantiomer in A. arborescens [48].

2.3. Gutierrezia sarothrae

Six individual samples of G. sarothrae were collected and hydrodistillation of the aerial parts of the plants gave pale-yellow essential oils in yields ranging from 3.681% to 4.606%. The essential oils were analyzed by GC-MS and GC-FID (Table 6). The most abundant components in the G. sarothrae essential oils were the monoterpene hydrocarbons (Z)-β-ocimene (18.8–39.4%), limonene (1.4–25.4%), β-pinene (0.5–18.4%), and α-phellandrene (2.2–11.8%), along with the diacetylenes (Z,E)-matricaria ester (0.2–9.3%) and (E,Z)-matricaria ester (0.1–7.5%). There were also several unidentified components with relatively high concentrations in the G. sarothrae essential oils. The mass spectra of the major unidentified compounds are available as supplementary material (Supplementary Figure S2). Although present in small amounts, the presence of nepetalactones was unexpected.

Table 6.

Chemical composition (percent of total) of the essential oil from the aerial parts of Gutierrezia sarothrae from southwestern Idaho.

A previous analysis of G. sarothrae essential oil from New Mexico reported geraniol (53.8%), γ-humulene (12.2%), trans-verbenol (6.0%), and verbenone (4.2%) as major components [35]. A subsequent examination of G. sarothrae essential oil from Utah by Epstein and Seidel [36] showed the major components to be (+)-α-pinene (12.6–22.9%), (−)-β-pinene (27.6–40.4%), (+)-limonene (7.2–13.1%), camphor (0.7–10.9%), (−)-pinocarvone (trace-11.3%), and (+)-verbenone (trace-6.0%). Another sample of G. sarothrae from New Mexico showed α-pinene (0.4–9.4%), β-pinene 0.7–9.6%), p-cymene (labeled as o-cymene, but the RI is more consistent with p-cymene, 2.5–7.9%), limonene (2.4–13.4%), cryptone (2.4–8.1%), bornyl acetate (2.8–4.5%), (E)-β-caryophyllene (2.3–4.8%), and β-eudesmol (0.1–5.9%) [37]. There is apparently much variation in the essential oil compositions of this plant and is likely due to subspecies variation [36]. Lane [27] has concluded, based on morphological characteristics, that “Gutierrezia sarothrae is an extremely variable taxon that possibly should be subdivided into a number of taxonomic varieties.” Ralphs and McDaniels have characterized eight chemotypes of G. sarothrae based on diterpenoid composition [30]. World Flora Online currently lists three varieties of G. sarothrae (var. sarothrae, var. pomariensis S.L. Welsh, and var. pauciflora Eastw.) [51].

The enantiomeric distributions of chiral terpenoid components were determined using chiral GC-MS (Table 7). (−)-α-Pinene (62.4–96.2%), (−)-β-pinene (97.3–99.8%), (−)-terpinen-4-ol (64.2–69.6%), (−)-α-terpineol (70.8–98.1%), and (−)-citronellol (64.7–70.2%) were the dominant enantiomers. Five of the six G. sarothrae essential oils showed (+)-limonene to be the major enantiomer (>90%), but sample G.s. #2 had (−)-limonene with 71.5%. Only one peak was observed for α-phellandrene, and its calculated RI was between the database RI values for (+)- and (−)-α-phellandrene, so identification of the enantiomer is in doubt. The predominance of (−)-β-pinene and (+)-limonene is in agreement with Epstein and Seidel [36]. In contrast, however, (−)-α-pinene was the major enantiomer in this present study, while Epstein and Seidel isolated (+)-α-pinene.

Table 7.

Enantiomeric distribution of chiral terpenoids in the essential oil from the aerial parts of Gutierrezia sarothrae.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Plant Material, Hydrodistillation

Aerial parts of several individuals of A. acanthicarpa, A. ludoviciana, and G. sarothrae were collected from the Owyhee mountains of southwestern Idaho. The plants were identified by W.N. Setzer by comparison with samples from the New York Botanical Garden [52,53,54] and the Brigham Young University Herbarium via the Intermountain Region Herbarium Network [55]. Voucher specimens (WNS-Aa-7768, WNS-Al-7669, WNS-Al-7782, WNS-Gs-7772) have been deposited with the University of Alabama in Huntsville herbarium. The plant materials were frozen fresh (−20 °C) and stored frozen until distilled. For each plant sample, the fresh-frozen aerial parts were hydrodistilled for 4 h using a Likens-Nickerson apparatus with continuous extraction of the distillate with dichloromethane. The collection and hydrodistillation details are summarized in Table 8.

Table 8.

Collection and hydrodistillation details for Ambrosia acanthicarpa, Artemisia ludoviciana, and Gutierrezia sarothrae from the Owyhee Mountains of Idaho.

3.2. Gas Chromatographic Analyses

The essential oils of the aerial parts of Ambrosia acanthicarpa, Artemisia ludoviciana, and Gutierrezia sarothrae were analyzed by gas chromatography coupled with flame ionization detection (GC-FID, gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS), and chiral GC-MS as previously described [56]. Instrumental details are provided as supplementary material (Supplementary Table S1). Retention indices (RI) were calculated based on a homologous series of n-alkanes using the linear equation of van den Dool and Kratz [57]. The essential oil components were identified by comparing their RI values (within ten RI units) and their MS fragmentation patterns (>80% similarity) with those reported in the Adams [58], FFNSC3 [59], NIST20 [60], and Satyal [61] databases. The compound percentages were based on raw peak areas without standardization. The individual enantiomers were determined from the chiral GC-MS analysis by comparison of RI values with authentic samples (Sigma-Aldrich, Milwaukee, WI, USA), which have been compiled in our in-house database. Percentages of each enantiomer were calculated from raw peak integration.

3.3. Hierarchical Cluster Analysis

The agglomerative hierarchical cluster (AHC) analysis was carried out on the A. ludoviciana essential oils using XLSTAT v. 2018.1.1.62926 (Addinsoft, Paris, France). The AHC analysis was performed using the concentrations of the 15 most abundant components (santolina triene, α-pinene, camphene, β-pinene, 1,8-cineole, lavender lactone, artemisia ketone, linalool, nonanal, camphor, borneol, terpinen-4-ol, α-terpineol, carvacrol, and davanone) from this current work as well as those previously reported compositions from the literature [21,22,23,24,25,26]. Dissimilarity was used to determine clusters, considering Euclidean distance, and Ward’s method was used to define agglomeration.

4. Conclusions

This is the first report on the chemical characterization of A. acanthicarpa essential oil. This species is wide-ranging in western North America, but the plants in this investigation were obtained from only one location in southwestern Idaho. Clearly, additional collections are needed to characterize the essential oil of this species more fully. In addition, this work complements previous investigations of A. ludoviciana by extending the geographical sampling as well as including enantiomeric distributions of chiral terpenoid components. It is apparent that not only the essential oil compositions, but also the enantiomeric distributions, are highly variable in A. ludoviciana. A comparison of essential oil analyses of G. sarothrae from this work and from previous investigations has revealed much variation in composition. Obviously, additional work on the essential oils of A. acanthicarpa, A. ludoviciana, and G. sarothrae are needed from different geographical locations. DNA barcode investigations may help to correlate with chemotypes of these species to help define the subspecies in these plants.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/molecules29061383/s1, Figure S1: Mass spectra of major unidentified components in the essential oils of Artemisia ludoviciana; Figure S2: Mass spectra of major unidentified components in the essential oils of Gutierrezia sarothrae. Table S1: Instrument details for the gas chromatographic analyses of Ambrosia acanthicarpa, Artemisia ludoviciana, and Gutierrezia sarothrae.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.N.S.; methodology, P.S. and W.N.S.; software, P.S.; validation, W.N.S.; formal analysis, A.P. and W.N.S.; investigation, K.S., A.P., P.S. and W.N.S.; data curation, W.N.S.; writing—original draft preparation, W.N.S.; writing—review and editing, K.S., A.P., P.S. and W.N.S.; project administration, W.N.S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by W.N.S.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the manuscript and Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

This work was carried out as part of the activities of the Aromatic Plant Research Center (APRC, https://aromaticplant.org/, accessed on 20 February 2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Payne, W.W. A re-evaluation of the genus Ambrosia (Compositae). J. Arnold Arbor. 1964, 45, 401–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissman, T.A.; Griffin, S.; Waddell, T.G.; Chen, H.H. Sesquiterpene lactones. Some new constituents of Ambrosia species: A. psilostachya and A. acanthicarpa. Phytochemistry 1969, 8, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, G.D.I. A chemotaxonomic study of some members of the Ambrosiinae (Compositae) II; The absolute and relative configuration of axivalin and its congeners. Ph.D. Thesis, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, J.R.; McArthur, E.D. Artemisia ludoviciana Nutt. Louisiana sagewort. In Wildland Shrubs of the United States and Its Territories: Thamnic Descriptions: Volume 1; Francis, J.K., Ed.; Forest Service, United States Department of Agriculture: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2004; pp. 69–71. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, M.; Roberts, W. White Sage Artemisia ludoviciana Nutt. Available online: https://plants.usda.gov/DocumentLibrary/plantguide/pdf/pg_arlu.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2024).

- World Flora Online. Artemisia ludoviciana Nutt. Available online: https://www.worldfloraonline.org/taxon/wfo-0000003410 (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- eFloras.org Artemisia ludoviciana Nuttall subsp. Ludoviciana. Available online: http://www.efloras.org/florataxon.aspx?flora_id=1&taxon_id=250068071 (accessed on 22 July 2023).

- eFloras.org Artemisia ludoviciana Nuttall subsp. candicans (Rydberg) D. D. Keck. Available online: http://www.efloras.org/florataxon.aspx?flora_id=1&taxon_id=250068069 (accessed on 22 July 2023).

- eFloras.org Artemisia ludoviciana Nuttall subsp. incompta (Nuttall) D. D. Keck. Available online: http://www.efloras.org/florataxon.aspx?flora_id=1&taxon_id=250068070 (accessed on 22 July 2023).

- Abad, M.J.; Bedoya, L.M.; Apaza, L.; Bermejo, P. The Artemisia L. genus: A review of bioactive essential oils. Molecules 2012, 17, 2542–2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anaya-Eugenio, G.D.; Rivero-Cruz, I.; Rivera-Chávez, J.; Mata, R. Hypoglycemic properties of some preparations and compounds from Artemisia ludoviciana Nutt. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 155, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moerman, D.E. Native American Ethnobotany; Timber Press, Inc.: Portland, OR, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-0-88192-453-4. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.H.; Geissman, T.A. Sesquiterpene lactones of Artemisia: Constituents of A. ludoviciana ssp. mexicana. Phytochemistry 1970, 9, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissman, T.A.; Saitoh, T. Ludalbin, a new lactone from Artemisia ludoviciana. Phytochemistry 1972, 11, 1157–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, W.W.; Ubben Jenkins, E.E. Anthemidin, a new sesquiterpene lactone from Artemisia ludoviciana. J. Nat. Prod. 1979, 42, 279–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakupovic, J.; Tan, R.X.; Bohlmann, F.; Boldt, P.E.; Jia, Z.J. Sesquiterpene lactones from Artemisia ludoviciana. Phytochemistry 1991, 30, 1573–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Cancino, A.; Cano, A.E.; Delgado, G. Sesquiterpene lactones and flavonoids from Artemisia ludoviciana ssp. mexicana. Phytochemistry 1993, 33, 1113–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-L.; Mabry, T.J. Flavonoids from Artemisia ludoviciana var. ludoviciana. Phytochemistry 1982, 21, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, O.; Wallnöfer, B.; Widhalm, M.; Greger, H. Naturally occurring thienyl-substituted spiroacetal enol ethers from Artemisia ludoviciana. Liebigs Ann. der Chemie 1988, 1988, 525–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, K.; Epstein, W.W. Studies on the biogenesis of non-head-to-tail monoterpenes. Isolation of (1R,3R)-chrysanthemol from Artemesia ludoviciana. J. Org. Chem. 1975, 40, 2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavala-Sánchez, M.A.; Pérez-Gutiérrez, S.; Pérez-González, C.; Sánchez-Saldivar, D.; Arias-García, L. Antidiarrhoeal activity of nonanal, an aldehyde isolated from Artemisia ludoviciana. Pharm. Biol. 2002, 40, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes-Lutz, D.; Alviano, D.S.; Alviano, C.S.; Kolodziejczyk, P.P. Screening of chemical composition, antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Artemisia essential oils. Phytochemistry 2008, 69, 1732–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anaya-Eugenio, G.D.; Rivero-Cruz, I.; Bye, R.; Linares, E.; Mata, R. Antinociceptive activity of the essential oil from Artemisia ludoviciana. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 179, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, G.; St-Gelais, A.; Turcotte, M.; Gagnon, H. Composition of the essential oil and of some extracts of the aerial parts of Artemisia ludoviciana var. latiloba Nutt. Am. J. Essent. Oils Nat. Prod. 2017, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Baldemir, A.; Karaman, Ü.; İlgün, S.; Kaçmaz, G.; Demirci, B. Antiparasitic efficacy of Artemisia ludoviciana Nutt. (Asteraceae) essential oil for Acanthamoeba castellanii, Leishmania infantum and Trichomonas vaginalis. Indian J. Pharm. Educ. Res. 2018, 52, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheljazkov, V.D.; Cantrell, C.L.; Jeliazkova, E.A.; Astatkie, T.; Schlegel, V. Essential oil yield, composition, and bioactivity of sagebrush species in the Bighorn Mountains. Plants 2022, 11, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, M.A. Taxonomy of Gutierrezia (Compositae: Astereae) in North America. Syst. Bot. 1985, 10, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladyman, J.A.R. Gutierrezia sarothrae (Pursh) Britt. & Rusby, broom snakeweed. In Wildland Shrubs of the United States and Its Territories: Thamnic Descriptions: Volume 1; Francis, J.K., Ed.; United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service: Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico, 2004; pp. 367–369. [Google Scholar]

- eFloras.org Gutierrezia sarothrae. Available online: http://www.efloras.org/florataxon.aspx?flora_id=1&taxon_id=250066828 (accessed on 12 August 2023).

- Ralphs, M.H.; McDaniel, K.C. Broom snakeweed (Gutierrezia sarothrae): Toxicology, ecology, control, and management. Invasive Plant Sci. Manag. 2011, 4, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohlmann, F.; Zdero, C.; King, R.M.; Robinson, H. Gutierrezial and further diterpenes from Gutierrezia sarothrae. Phytochemistry 1984, 23, 2007–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Dalal, S.; Goetz, M.; Cassera, M.B.; Kingston, D.G.I. New antiplasmodial diterpenes from Gutierrezia sarothrae. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2016, 11, 719–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, D.R.; Cook, D.; Larsen, S.W.; Stonecipher, C.A.; Johnson, R. Diterpenoids from Gutierrezia sarothrae and G. microcephala: Chemical diversity, chemophenetics and implications to toxicity in grazing livestock. Phytochemistry 2020, 178, 112465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hradetzky, D.; Wollenweber, E.; Roitman, J.N. Flavonoids from the leaf resin of snakeweed, Gutierrezia sarothrae. Zeitschrift fur Naturforsch.Sect. C J. Biosci. 1987, 42, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molyneux, R.J.; Stevens, K.L.; James, L.F. Chemistry of toxic range plants. Volatile constituents of broomweed (Gutierrezia sarothrae). J. Agric. Food Chem. 1980, 28, 1332–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, W.W.; Seidel, J.L. Monoterpenes of Gutierrezia sarothrae. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1989, 37, 651–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucero, M.E.; Fredrickson, E.L.; Estell, R.E.; Morrison, A.A.; Richman, D.B. Volatile composition of Gutierrezia sarothrae (broom snakeweed) as determined by steam distillation and solid phase microextraction. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2006, 18, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, A.; Satyal, P.; Swor, K.; Setzer, W.N. Essential oils of two Great Basin composites: Chaenactis douglasii and Dieteria canescens from southwestern Idaho. J. Essent. Oil Plant Compos. 2023, 1, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicció, J.F.; Chaverri, C. Essential oil composition of Ambrosia cumanensis (Asteraceae) from Costa Rica. Am. J. Essent. Oils Nat. Prod. 2015, 3, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Solís-Quispe, L.; Pino, J.A.; Marín-Villa, J.Z.; Tomaylla-Cruz, C.; Solís-Quispe, J.; Aragón-Alencastre, L.J.; Hernández, I.; Cuellar, C.; Rodeiro, I.; Fernández, M.D. Chemical composition and antioxidant activity of Ambrosia arborescens Miller leaf essential oil from Peruvian Andes. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2022, 34, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janaćković, P.; Rajčević, N.; Gavrilović, M.; Novaković, J.; Radulović, M.; Miletić, M.; Janakiev, T.; Dimkić, I.; Marin, P.D. Essential oil composition of Ambrosia artemisiifolia and its antibacterial activity against phytopathogens. Biol. Life Sci. Forum 2022, 15, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Shao, H.; Zhou, S.; Mei, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Huang, L.; Lv, G. Chemical composition and phytotoxicity of essential oil from invasive plant, Ambrosia artemisiifolia L. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 211, 111879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzrafi, M.; Wolberg, S.; Abu-Nassar, J.; Zelinger, E.; Bar, E.; Cafri, D.; Lewinsohn, E.; Shtein, I. Distinctive foliar features and volatile profiles in three Ambrosia species (Asteraceae). Planta 2023, 257, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzmán, L.; Malla, J.L.; Ramírez, J.; Gilardoni, G.; Calva, J.; Hidalgo, D.; Valarezo, E.; Rey-Valeirón, C. Acaricidal efficacy of plants from Ecuador, Ambrosia peruviana (Asteraceae) and Lepechinia mutica (Lamiaceae) against larvae and engorged adult females of the common cattle tick, Rhipicephalus microplus. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarić-Krsmanović, M.; Umiljendić, J.G.; Radivojević, L.; Rajković, M.; Šantrić, L.; Đurović-Pejčev, R. Chemical composition of Ambrosia trifida essential oil and phytotoxic effect on other plants. Chem. Biodivers. 2020, 17, e1900508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holm, Y.; Laakso, I.; Hiltunen, R.; Galambosi, B. Variation in the essential oil composition of Artemisia annua L. of different origin cultivated in Finland. Flavour Fragr. J. 1997, 12, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swor, K.; Satyal, P.; Poudel, A.; Setzer, W.N. Chemical characterization of three Artemisia tridentata essential oils and multivariate analyses: A preliminary investigation. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2023, 18, 1934578X231154965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Presti, M.; Crupi, M.L.; Zellner, B.d.; Dugo, G.; Mondello, L.; Dugo, P.; Ragusa, S. Characterization of Artemisia arborescens L. (Asteraceae) leaf-derived essential oil from Southern Italy. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2007, 19, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, M.E.A.; Militello, M.; Saia, S.; Settanni, L.; Aleo, A.; Mammina, C.; Bombarda, I.; Vanloot, P.; Roussel, C.; Dupuy, N. Artemisia arborescens essential oil composition, enantiomeric distribution, and antimicrobial activity from different wild populations from the Mediterranean area. Chem. Biodivers. 2016, 13, 1095–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, M.E.A.; Vanloot, P.; Bombarda, I.; Naubron, J.V.; Dahmane, E.M.; Aamouche, A.; Jean, M.; Vanthuyne, N.; Dupuy, N.; Roussel, C. Analysis of the major chiral compounds of Artemisia herba-alba essential oils (EOs) using reconstructed vibrational circular dichroism (VCD) spectra: En route to a VCD chiral signature of EOs. Anal. Chim. Acta 2016, 903, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Flora Online. Gutierrezia sarothrae (Pursh) Britton & Rusby. Available online: https://www.worldfloraonline.org/taxon/wfo-0000038804 (accessed on 13 February 2024).

- New York Botanical Garden. C. V. Starr Virtual Herbarium. Available online: https://sweetgum.nybg.org/science/vh/specimen-list/?SummaryData=Ambrosia acanthicarpa (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- New York Botanical Garden. C. V. Starr Virtual Herbarium. Available online: https://sweetgum.nybg.org/science/vh/specimen-list/?SummaryData=Artemisia ludoviciana (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- New York Botanical Garden. C. V. Starr Virtual Herbarium. Available online: https://sweetgum.nybg.org/science/vh/specimen-list/?SummaryData=Gutierrezia sarothrae (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Herbarium, B.Y.U. Intermountain Region Herbarium Network. Available online: https://www.intermountainbiota.org/portal/index.php (accessed on 16 August 2023).

- Poudel, A.; Dosoky, N.S.; Satyal, P.; Swor, K.; Setzer, W.N. Essential oil composition of Grindelia squarrosa from southern Idaho. Molecules 2023, 28, 3854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Dool, H.; Kratz, P.D. A generalization of the retention index system including linear temperature programmed gas-liquid partition chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 1963, 11, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.P. Identification of Essential Oil Components by Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry, 4th ed.; Allured Publishing: Carol Stream, IL, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-1-932633-21-4. [Google Scholar]

- Mondello, L. FFNSC 3; Shimadzu Scientific Instruments: Columbia, MD, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- NIST20; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2020.

- Satyal, P. Development of GC-MS Database of Essential Oil Components by the Analysis of Natural Essential Oils and Synthetic Compounds and Discovery of Biologically Active Novel Chemotypes in Essential Oils. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Alabama in Huntsville, Huntsville, AL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).