Abstract

Norditerpenes are considered to be a common and widely studied class of bioactive compounds in plants, exhibiting a wide array of complex and diverse structural types and originating from various sources. Based on the number of carbons, norditerpenes can be categorized into C19, C18, C17, and C16 compounds. Up to now, 557 norditerpenes and their derivatives have been found in studies published between 2010 and 2023, distributed in 51 families and 132 species, with the largest number in Lamiaceae, Euphorbiaceae, and Cephalotaxaceae. These norditerpenes display versatile biological activities, including anti-tumor, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and antioxidant properties, as well as inhibitory effects against HIV and α-glucosidase, and can be considered as an important source of treatment for a variety of diseases that had a high commercial value. This review provides a comprehensive summary of the plant sources, chemical structures, and biological activities of norditerpenes derived from natural sources, serving as a valuable reference for further research development and application in this field.

1. Introduction

Diterpenes are natural terpenes composed of twenty carbon atoms in their molecules and are formed by the polymerization of four isoprene units. They are widely distributed in plants, particularly in plant-secreted milk and resin. In addition to plants, diterpenes can also be found in fungal metabolites and marine organisms. Generally consisting of 20 carbons, diterpenes can give rise to norditerpenes with fewer carbon atoms due to the absence of one to three carbon atoms within the diterpene core structure. C19 norditerpenes, which lack one carbon atom, represent the most common structural type among norditerpenes. Natural sources of norditerpenes exhibit diverse pharmacological activities including anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor, and antimicrobial effects. Therefore, extensive attention has been drawn toward research on norditerpenes. Norditerpene alkaloids are a class of norditerpenes. Yong Shen and coworkers reviewed 337 naturally occurring diterpene alkaloids, including 251 norditerpene alkaloids, derived from studies published between 2008 and 2018 [1]. To avoid the duplication of previous work, this article reviews the structural types and biological activities of norditerpenes (norditerpene alkaloids are not included) derived from studies published between 2010 and 2023. In general, 557 norditerpenes and their derivatives were found in the natural world, distributed into 132 species and 51 families (Table 1). This provides the basis for further research on the discovery of natural product drugs.

Table 1.

Sources of 557 norditerpenes (families, genera, and species and the corresponding quantity of the compounds).

2. Chemical Constituents of C19 Norditerpenes

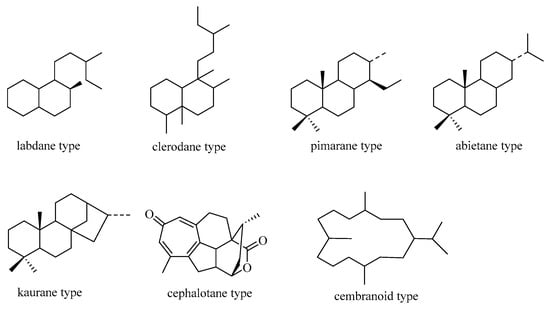

In nature, seven primary categories of C19 norditerpenes have been identified: the labdane, pimarane, abietane, kaurane, clerodane, cephalotane, and cembranoid types. These types are shown in Figure 1 as their fundamental frameworks. Additionally, there are other norditerpenes with distinctive structures in the natural environment.

Figure 1.

Basic skeleton of C19 norditerpenes.

2.1. Labdane

Labdane norditerpenes are commonly found as bicyclic diterpenes, with a trans-fused A/B ring in the nuclear parent and a side chain typically consisting of a six-carbon open chain. The presence of hydroxyl groups on the side chain allows for easy dehydration and condensation reactions, leading to the formation of a five-membered ring. Labdane-type diterpenes with both an open-chain structure and a five-membered ring in the side chain have a wide distribution (Table 2, Figure 2).

Table 2.

Chemical constituents of labdane-type C19 norditerpenes.

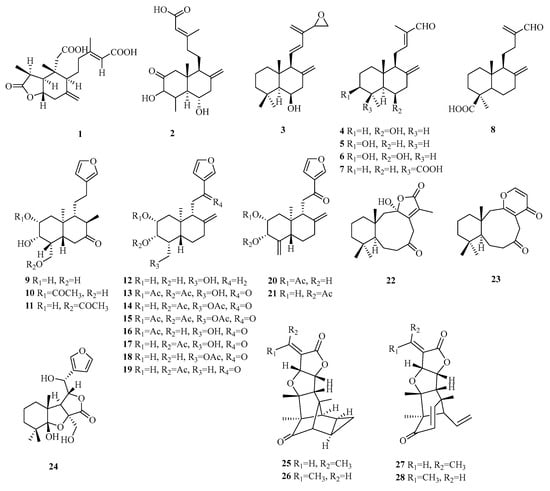

Figure 2.

Structures of labdane-type C19 norditerpenes.

Compound 1 is a novel diterpene belonging to the 3-nor-2,3-seco-labdane class. It is characterized by fission the between C-2 and C-3 of ring A, followed by decarboxylation at C-3. Compound 2 is a rare 19-nor labdane-type diterpene isolated from fungus, while compounds 3–8 possess a fused bicyclic fragment with a 6/6 fusion, both of which are classified as 15-norditerpenes. Compounds 9–21 belong to the ent-nor-furano diterpene of the labdane series. Compounds 22–23 feature unique nine-membered ring structures, showcasing unprecedented characteristics. Compound 23 exhibits an exceptional structural motif with a fused α, β-unsaturated-γ-lactone unit, and a nine-membered ring B at C-10/C-11. Compound 24 represents a rare instance of a 6-norlabdane-type diterpene containing a tetrahydrofuran-lactone moiety. Compounds 25–26 display unparalleled hexacyclic structures as 19-nor-secolabdane diterpenes with tetracyclodecane skeletons. Compounds 27–28 are structurally similar to compounds 25–26 and exist as Z(E)-isomers.

2.2. Clerodane

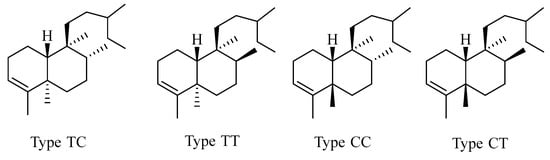

Clerodane norditerpenes consist of a fused-ring decalin moiety (C1–C10) and a six-carbon side chain at C-9. Based on the A/B ring junction configuration and the substituents on C-8 and C-9, its skeletons can be classified into four types (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Basic skeletons of clerodane-type C19 norditerpenes.

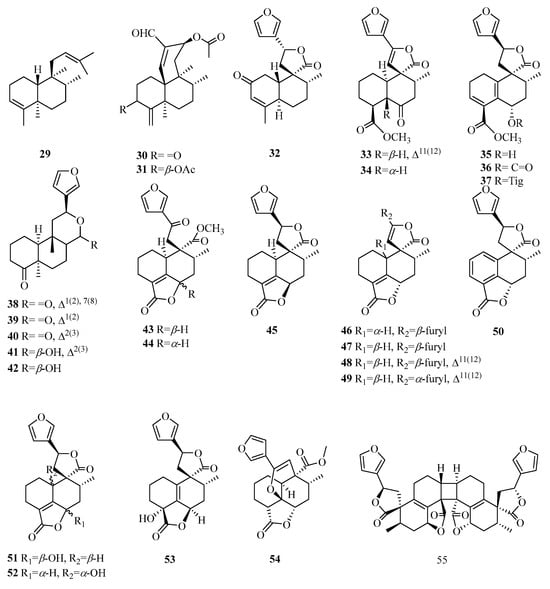

Compound 29 is characterized by a double bond between carbon atoms C-3 and C-4. Compounds 30–31 have a fused tricyclic ring system with a 6/6/6 configuration. Compound 32 belongs to the bioactive clerodane class of 19-nor-diterpenes, featuring a cyclohexenone decalin ring. Compound 33 is a dehydrogenated derivative of compound 34, resulting in the removal of hydrogen atoms from positions C11–C12. Compounds 35–37 exhibit a distinct 3,5(10)-diene moiety. Compounds 38–40 belong to the furanoditerpenes of the 18-nor-clerodane class. Compounds 43–44 display an opened lactone ring at positions 17 and 12, accompanied by oxidation occurring at position C-12. Compounds 43–52 possess a butenolide moiety extending from C-19 to C-6. Compound 53 demonstrates a similar structure, albeit featuring a double bond between C-5 and C-10. Compound 54 consists of a unique cage-like tetracyclic ring system, fused in a pattern of 6/6/6/5, which is formed by the incorporation of a 5,12-epoxy ring. Compound 55 is identified as an exceptionally symmetrical diterpene dimer characterized by the formation of a cyclobutane ring through [2 + 2] cycloaddition (Table 3, Figure 4).

Table 3.

Chemical constituents of clerodane-type C19 norditerpenes.

Figure 4.

Structures of clerodane-type C19 norditerpenes.

2.3. Pimarane

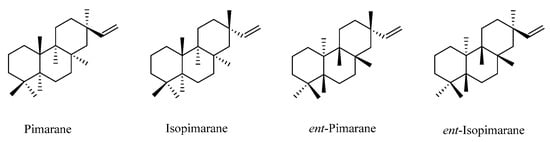

Pimarane norditerpenes are tricyclic diterpenes and are widely distributed in nature. Pimarane norditerpenes are mainly divided into four types (Figure 5): pimarane, isopimarane, ent-pimarane, and ent-isopimarane. Isopimarane norditerpenes are a class of compounds classified by pimarane norditerpenes according to the difference of chiral centers in the molecule, and they are also the largest number of pimarane norditerpenes (Table 4, Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Basic skeletons of pimarane-type C19 norditerpenes.

Table 4.

Chemical constituents of pimarane-type C19 norditerpenes.

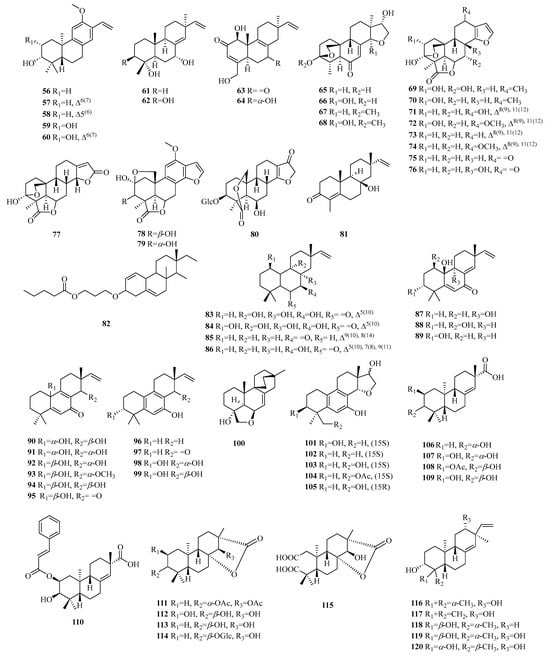

Figure 6.

Structures of pimarane-type C19 norditerpenes.

2.3.1. Pimarane

Compounds 56–75 belong to the category of pimarane-type norditerpene compounds. Compounds 56–60 featured a methoxy group at C-12 and included a vinyl fragment at C-13. Compounds 63–64 are exceptional members within the bacterial norditerpene metabolite family. Compounds 65–77 exhibit a tetracyclic structure with a 3,20-epoxy bridge, except for compounds 69–77, which also feature lactone carbon at C-19, indicating the presence of the 19,6-gamma-lactone moiety. Compound 77 has been identified as (9βH)-17-norpimarane dilactone. Additionally, both compounds 78 and 79 exhibit β orientation of the 2,20-epoxy bridge. Compound 80 represents the first example of a glucoside derivative of 17-nor-pimarane diterpenes.

2.3.2. Isopimarane

Compounds 81–105 are isopimarane-type norditerpene compounds, with compound 82 featuring a bulky O-propyl pentanoate group at C-3. Compounds 90–95 exhibit unique examples of the 20-nor-isopimarane type, characterized by the presence of a cyclohexa-2,5-dien-1-one moiety. Compounds 96–99 represent four aromatic norditerpenes. Compound 100 possesses an unusual skeleton composed of an 18-nor-9, 16-cyclo-isopimarane framework with a cage-like bicycle [2.2.2] octane moiety. Lastly, compounds 101–105 display a rare 14,16-cyclic ether unit and possess a unique 6/6/6/5 tetracyclic cycloether skeleton.

2.3.3. Ent-Pimarane

Compounds 106–109 exhibit an ester bond instead of the olefinic bond at C-13. Compound 110 displays an additional cinnamoyl group and a vinyl benzene moiety. Compounds 111–115 are characterized by a rare 16-nor-ent-pimarane skeleton and demonstrate the presence of γ-lactone between the C15-O-C8 bonds. Compound 115 represents the first reported instance of this previously undescribed skeleton of 2, 3-seco-16-nor-ent-pimarane.

2.3.4. Ent-Isopimarane

Compounds 116–117 represent the first examples of 18 (or 19)-ent-isopimarane norditerpenes. Compound 117 has a double bond at C-14, while compounds 118–120 feature a hydroxyl group at C-4, with compound 119 being the C-4 epimer of 120.

2.4. Abietane

Abietane norditerpenes are tricyclic diterpenes commonly formed through rearrangements of pimarane norditerpenes. The core structure consists of a hydrogenated phenanthrene with an isopropyl group at C-13, geminal dimethyl groups at C-4, and a methyl group at C-20. Ring B and the side chains on the C ring can easily undergo rearrangement to form a five-membered ring, with some quinone structures also found on the C ring. Abietane norditerpenes are primarily classified into abietane type, ent-abietane type, and seco-abietane type (in Table 5, Figure 7).

Table 5.

Chemical constituents of abietane-type C19 norditerpenes.

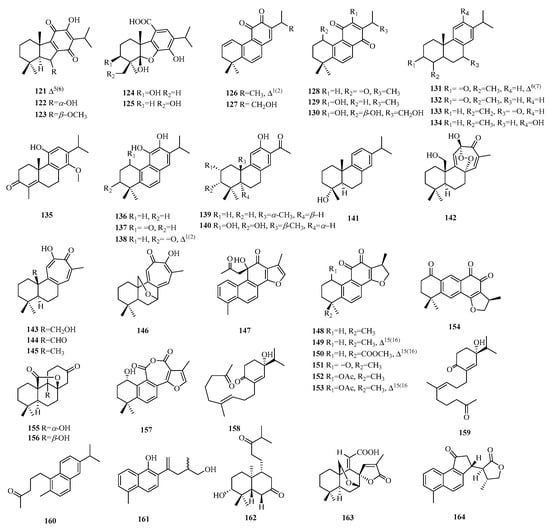

Figure 7.

Structures of abietane-type C19 norditerpenes.

Compounds 121–123 belong to the 8-nor-7(8→14),9(8→7)-di-abeo-abietane skeleton type. Compounds 124–125 possess a 6-nor-6,7-seco-abietane skeleton. Compounds 126–127 contain a moiety of 1,2-quinone, while compounds 128–130 feature a moiety of 1,4-quinone in ring C. Compounds 126–141 are aromatic norditerpenes, while compounds 142–146 feature a tropolone moiety; notably, compound 142 is characterized by the presence of a peroxide group connecting C-8 and C-12. Furthermore, compounds 147–153 demonstrate rearranged side chains that form an oxygen-containing five-membered ring. Compounds 155–156 possess a unique γ-lactone subgroup located between C-8 and C-20. Compound 157 is a seven-membered norditerpene featuring two carbonyl groups in the C ring. Compounds 158–162 are seco-abietane norditerpenes. Compounds 158–159 possess a unique 18-nor-5,10: 9,10-disecoabietane skeleton, while compound 160 exhibits a rearranged angular methyl group at C-5 and belongs to the 4, 5-seco-19-nor-abietane skeleton. Compound 163 is characterized by a 7β,19-epoxydecalin spirally linked with a five-membered α, β-unsaturated lactone ring, and an acrylic acid moiety.

2.5. Kaurane

Kaurane norditerpenes represent a class of tetracyclic diterpenes characterized by the hydrophenanthrene core skeleton. These compounds can be classified into two configurations, namely kaurane and ent-kaurane. It is worth noting that the ent-kaurane-type norditerpenes exhibit remarkable abundance (Table 6, Figure 8).

Table 6.

Chemical constituents of kaurane-type C19 norditerpenes.

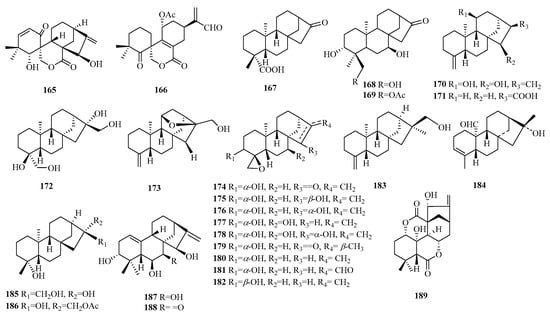

Figure 8.

Structures of kaurane-type C19 norditerpenes.

Compounds 165–166 are spiral seco ent-kaurane norditerpenes. Compound 165 is a naturally occurring compound with a structure of 6-nor-6,7-seco-ent-kauranoid, while compound 166 featured a 6,7: 8,15-seco-ent-kaurane diterpene skeleton.

Compounds 170–182 are classified as ent-18-norkaurene-type diterpenes. Compound 173 features an 11β,16β-epoxy ring moiety. Compounds 174–182 exhibit a 4β, 19-epoxy ring moiety. Compounds 183–186 are categorized as C-19 nor-ent-kaurane norditerpenes.

Compounds 187–188 demonstrate a unique structural pattern of 20-nor-ent-kaurane norditerpenes. Compound 189 is determined to be a nor-6,7-seco-1,7: 6, 11-diolide-ent-kaurane, and the first diterpenene within the category of the 20-nor-enmein type.

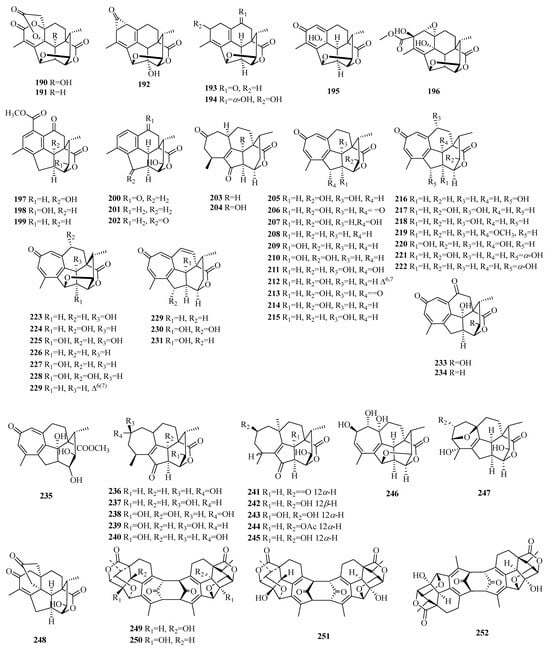

2.6. Cephalotane

In the past decade, more than fifty cephalotane-type norditerpenes have been discovered through previous phytochemical investigations, which can be categorized into four distinct structural groups: A-ring-contracted cephalotane-type norditerpenes, cephalotaxus troponoids (C19), 17-nor-cephalotane-type diterpenes (C19), and cephalotane dimers (Table 7, Figure 9).

Table 7.

Chemical constituents of cephalotane-type C19 norditerpenes.

Figure 9.

Structures of cephalotane-type C19 norditerpenes.

Compounds 190–202 are norditerpenes featuring a contracted A-ring structure. Compound 192 exhibits a distinctive bicyclo [4.1.0] hepta-2,4-dien-7-one moiety. Compounds 203–235 belong to cephalotaxus troponoids, which represent the predominant group of cephalotane-type norditerpenes. The skeletal structure of cephalotaxus troponoids is distinguished by a highly rigid tetracyclic carbon framework, encompassing a tropone moiety, multiple oxygenated groups, and methyl substituents at positions C-4 and C-12. Cephalotaxus troponoids are derived from labdane-type norditerpenes. The 17-nor-cephalotane-type diterpenes were derived from cephalotaxus troponoids via a reduction in the tropone ring. Compounds 236–248 exemplify this class of diterpenes, while compound 247 features an 8-oxabicyclo [3.2.1] oct-2-ene moiety. Compounds 249–252 represent the first example of C19 norditerpene dimers and possess a unique tricycle [6.4.1.12, 7] tetradeca-3,5,9,11-tetraene-13,14-dione core, and both ends are terminated with a C2 symmetric or asymmetric rigid polycyclic ring system.

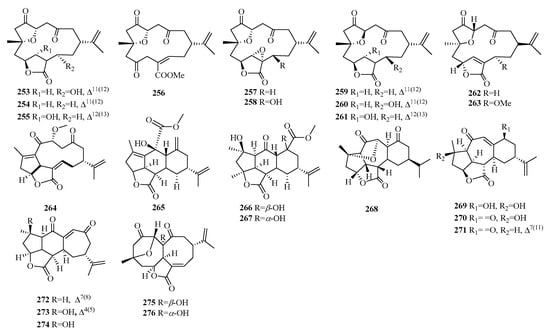

2.7. Cembranoid

Cembranoid-type norditerpenes are macrocyclic diterpenes that belong to a class of natural products characterized by fourteen-membered rings and possess three symmetrically distributed methyl groups and one isopropyl group. Isopropyl-cembrane-type norditerpenes, primarily formed through isopropyl or isopropenyl substitution, represent the most common cembrane-type norditerpenes (Table 8, Figure 10).

Table 8.

Chemical constituents of cembranoid-type C19 norditerpenes.

Figure 10.

Structures of cembranoid-type C19 norditerpenes.

Compounds 253–263 are characterized by the presence of polycyclic furanobutenolide-derived norcembranoid diterpenes isolated from soft corals. Compound 264 possesses a rare 5/5/11-fused tricyclic ring system, while compounds 265–267 possess a 5/5/6/6 tetracyclic ring system. Compounds 268–274 possess a cyclopentane ring, a cyclohexane ring, and a seven-membered ring. Compounds 275–276 display an uncommon 8/8 bicyclic carbon core.

2.8. Others

Compounds 277–278 are lathyrane-type norditerpenes. Compound 279 is an atypical C19 furano-norditerpene. Compounds 280–282 have uncommon characteristics as cassane-type norditerpenes. The classification of compounds 283–286 confirms their identity as cleistanthane-type norditerpenes. The discovery of compounds 283–284 marks the first examples of phenylethylene-bearing derivatives among 20-nor-diterpenes, with compound 284 exhibiting a unique 3,10-oxybridge moiety. Compound 286 stands out due to its scarcity among phenylacetylene-containing 18-nor-diterpene glycosides. Compounds 287–291 exhibit the characteristic fusicoccane-type norditerpenes. Specifically, compounds 287–289 belong to a unique category of 16-nor-dicyclopenta [a,d]-cyclooctane norditerpenes, while compound 287 features an undescribed tetracyclic ring system with a configuration of 5/6/6/5. Compounds 292–293 are obtained through the rearrangement of the crotofolane skeleton. Compounds 294–295 exhibit a pair of enantiomeric norditerpenes featuring an unexpected 6/5/6/6-fused tetracyclic ring system. Compounds 296–298 are uniformly classified as ent-atisane norditerpenes. Compound 299 possesses a perhydroazulene ring system, while compounds 300–302 represent three newly rearranged oxygenated terpenes. Compounds 303–304 belong to the class of spongian diterpenes and exhibit a highly distinctive carbon skeleton known as 3-nor-spongian. Li’s group unveiled four unprecedented C19 norditerpenes, including compound 305 with a cyclopenta[b]furan-2,5-dione skeleton, compound 306 with a pyran[b]furan-2,6-dione skeleton, and compounds 307–308, which are epimerides possessing a pair of dioxaspiro[4.4]nonane skeletons.

Compound 309 is a naturally occurring norditerpene with a seven-membered ring mulinane skeleton lacking the C-16-methyl group. Compound 310 possesses an undescribed nor-guanacastane skeleton. Compound 312 has been identified as an isomer of 311. Compounds 313–314 belong to yonarane norditerpenes, and compound 317 belongs to inelegane-type norditerpenes. Compound 315 is considered an undescribed bicyclo[11.3.0]hexadecane carbon skeleton, whereas compounds 316–321 are consistently classified as verticillane-type norditerpenes. Compounds 322–323 are norditerpene glycosides. Compounds 324–332 represent new norditerpene lactones, whereas compounds 333–345 are norditerpene oidiolactones. Compounds 347–358 have been identified as norditerpene picrotoxanes. Compound 359 exhibits a podocarpane skeleton, while compound 360 belongs to the xeniaphyllane-type norditerpene. Compounds 363–364 are a heterodimeric diterpene consisting of an ent-abietane and an 18-nor-rosane skeleton with an aromatic ring (Table 9, Figure 11).

Table 9.

Chemical constituents of other compounds of C19 norditerpenes.

Figure 11.

Structures of other compounds of C19 norditerpenes.

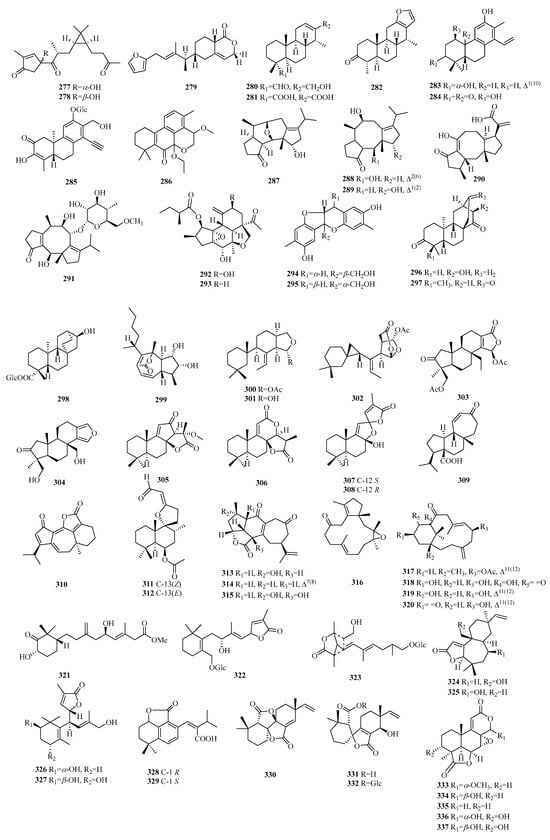

3. Chemical Constituents of C18 Norditerpenes

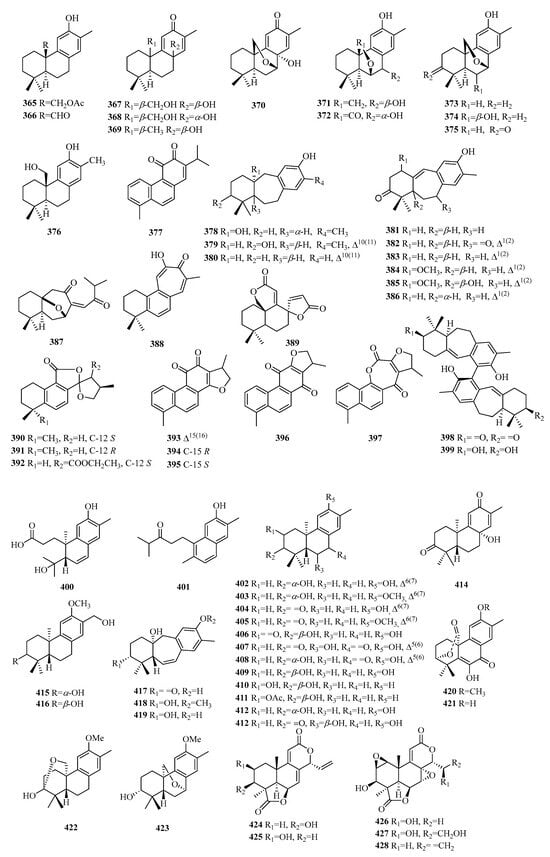

Ten primary categories of C18 norditerpenes have been identified in the natural environment, including the labdane, abietane, podocarpane, pimarane, cassane, aspergilane, benzodioxane, commiphorane, totarane, and cephalotane types. Additionally, there are other norditerpenes with atypical structures and certain abietane dipolymers found in nature (Table 10, Figure 12).

Table 10.

Chemical constituents of C18 norditerpenes.

Figure 12.

Structures of C18 norditerpenes.

3.1. Abietane

Compound 365 is a new abietane type and has been reported as a 20-acetyl derivative of 15,16-dinorpymara-8,11,13-trien-12-ol, known as salyunnanin F. Compound 368 is a diastereomer of 367. Compounds 370–375 exhibit an ether bridge between C-18 and C-6 or C-7. Compounds 378–388 are dinorditerpenes derived from an abietane-type skeleton with a seven-membered ring in the tricyclic skeleton. Compound 387 is a unique C18 norditerpene bearing a special seco-ring C. Compounds 389–397 belong to a special class of tetracyclic abietane-type dinorditerpenes. The stem bark of Trigonostemon chinensis yielded two novel dimeric degraded diterpenes, compounds 398–399, featuring a homodimeric biaryl skeleton derived from the rearrangement of chiral nonracemic abietane-type norditerpenes. This structural motif is connected through an axially chiral biaryl 11,11′-linkage.

3.2. Podocarpane

The podocarpane type is a trinucleated norditerpene. Compounds 400–414 and 420–423 are new 13-methyl-ent-podocarpane norditetrpenoids, while 427–428 are 12-methyl-ent-podocarpane norditetrpenoids.

Compounds 400–401 exhibit a unique dinorditerpene bearing a special seco-ring A, and 400 is a 13-methyl-3,4-seco-ent-podocarpane norditetrpenoid. Compounds 417–419 are classified as 13-methyl-9(10→20)-abeo-ent-podocarpane norditetrpenoids. Compounds 420–431 are 13-methyl-7-oxo-ent-podocarpane norditetrpenoids, and compound 420 is a derivative methylated at position 12 of compound 421. Compounds 424–428 belong to a special class of tetracyclic diterpenes.

3.3. Other Compounds

Compound 429 is an oxidized derivative of the common C20 labdane precursor and is identified as a 15,16-dinor labdane diterpene. Compounds 430–435 are determined to be 14,15-bisnor labdane diterpenes. Compounds 436–437 present the 6,7-dinorlabdane diterpenes with a peroxide bridge. Compound 438 is a special norditerpene glucoside and is defined as lyonivaloside I.

Compounds 439–448 contain a unique skeleton of 15,16-dinor-ent-pimarane diterpenes. Compound 449 represents a novel phenolic cassane norditerpene. Compound 450 exhibits a new aspergilane skeleton in structure with a special 6/5/6 tricyclic system containing an α,β-unsaturated spironolactone moiety in the B ring. Compound 451 is a novel natural product with a rare 6/6/5-fused tricyclic ring system. Compounds 452–453 are two compounds consisting of dinorditerpene and 90-norrosmarinic acid derivatives and are linked by a 1,4-benzodioxanyl motif. Compounds 454–455 are aromatic tetranuclear terpenoids with unprecedented carbon skeletons from Resina Commiphora and possess an uncommon 6/6/6/6 ring system. Compounds 458–465 have been identified as a series of totarane-type norditerpenes. Compounds 464–468 exhibit the rare characteristic of A-ring contraction, known as cephanolide A–C. Compound 469 possesses a skeleton of 17,19-dinorxeniaphyllane.

4. Chemical Constituents of C17 Norditerpenes

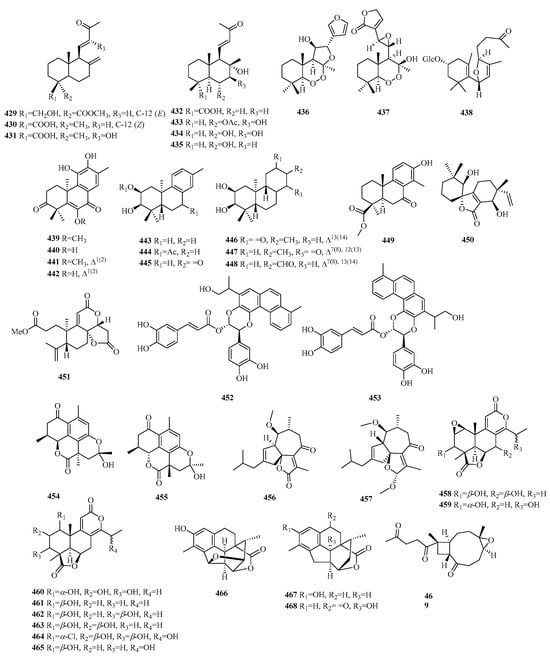

Seven major types of C17 norditerpenes have been reported in nature: the labdane type, abietane type, podocarpane type, briarane type, cassane type, cembrane type, and kaurane type. Additionally, there are other trinorditerpenes with special structures and some podocarpane dimers in nature (Table 11, Figure 13).

Table 11.

Chemical constituents of C17 norditerpenes.

Figure 13.

Structures of C17 norditerpenes.

4.1. Abietane

Compounds 470–477 are 15,16,17-bis-norditerpenes. Compound 479 is the 16-OH derivative of 478. Compound 480 represents a rare skeleton of a 20-nor-abietane. Compound 482 is defined as the C-7 epimer of compound 485, while compounds 484–486 are aromatic tetranuclear terpenoids with unprecedented carbon skeletons from S. digitaloides. Compounds 487–488 possess a unique γ-lactone subunit moiety positioned between C-8 and C-20, leading to the generation of the carbonyl carbon at C-13 through the degradation of the isopropyl group.

4.2. Podocarpane

Compounds 489–511 are trinorditerpenes of the podocarpane type. Compounds 509–510, existing as atropisomers, are two previously unknown dimeric trinorditerpenes separated from the root bark of C. orbiculatus. Compound 511 is a rare dimeric trinorditerpene with a 1,4-benzodioxane moiety.

4.3. Others

Compound 512 is a novel labdane-norditerpenoid glycoside with a six-membered epoxy system (8→13). Compound 513 is a novel norditerpene derived from a briarane skeleton. Compound 514 represents a previously unidentified trinorcassane diterpenoid bearing a dicyclic norditerpenoid with three acetoxy moieties. Compound 515 is determined to be a cembrane-type macrocyclic trinorditerpenoid with a fused 10/6 carbon skeleton. Compound 516 is a unique trinorditepenoid containing an unprecedented 20-epoxy-ent-kaurane skeleton. Compounds 517–521 are three pairs of unfrequent C17 γ-lactone norditerpenoid enantiomers.

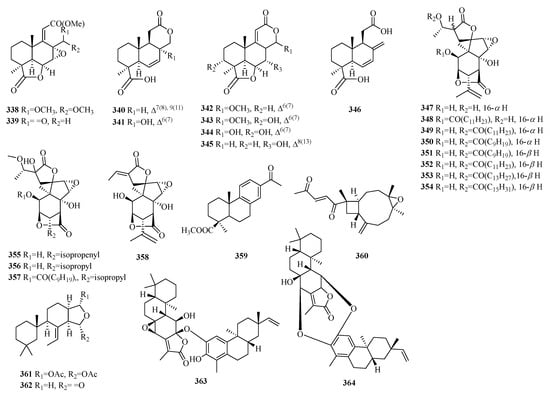

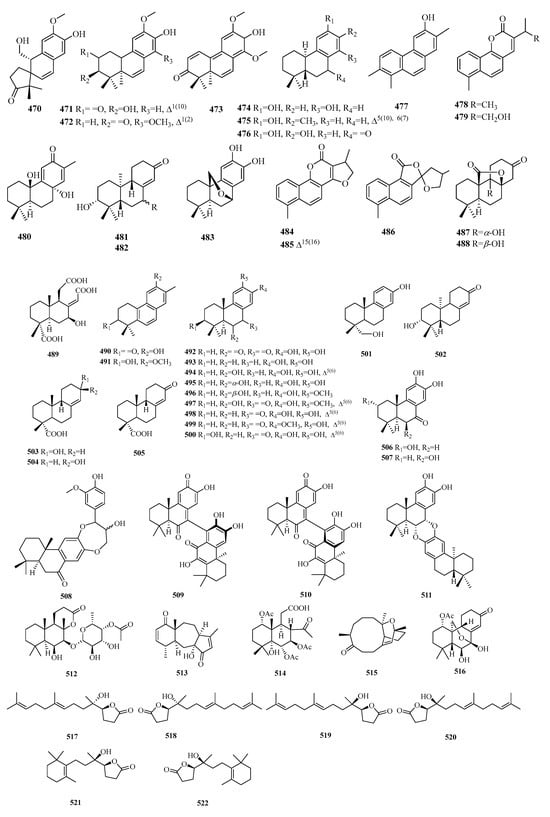

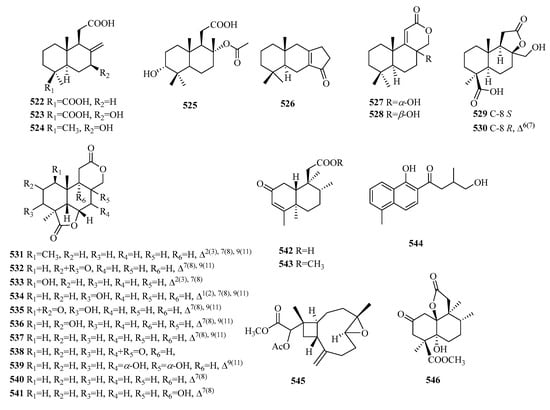

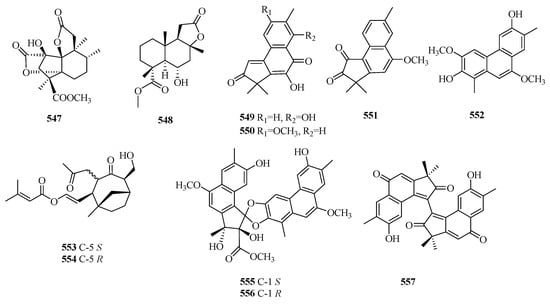

5. Chemical Constituents of C16 Norditerpenes

Four main types of C16 norditerpenes have been found in nature: the labdane type, clerodane type, xeniaphyllane type, and abietane type. In addition to the common four types, there are also other norditerpenoids with unique structures and some dimers in nature sources (Table 12, Figure 14).

Table 12.

Chemical constituents of C16 norditerpenes.

Figure 14.

Structures of C16 norditerpenes.

5.1. Labdane

C16-labdane norditerpenes are common bicyclic diterpenes with four fewer carbon atoms. Compounds 522–525 are known as bicyclic norditerpenoids. Compound 525 is the first to be reported in nature. Compound 526 is a rare rearranged labdane-type tetranorditerpenoid with a fused tricarbocyclic system (6/6/5) and an α,β-unsaturated cyclopentenone unit in ring C. Compounds 527 and 528 represent a pair of new labdane-type tetranorditerpenoid epimers, which are the first known examples of naturally derived labdane tetranorditerpenoids. Compounds 531–541 are a series of tetracyclic tetranorlabdane diterpenoids.

5.2. Others

Compounds 542–543 exhibit clerodane-type tetranorditerpenoids. Compound 544 is a novel abietane tetranorditerpenoid, known as castanol C. Compound 545 possesses an unprecedented carbon skeleton derived from xeniaphyllane. Compound 546 is a newly reported tetranorditerpenoid featuring a special fused ring system of 6/6/5. Compound 547 is a new C16 tetranorditerpenoid lactone with an uncommon tetracyclic fuse system of 5/5/5/6. Compounds 549–551 possess an unprecedented framework of 2H-benz[e]inden-2-one. Compounds 552–553 represent a pair of epimers of vibsane-type tetranorditerpenes with a bicyclo[4.2.1]nonane unit. Compounds 555–556 comprise a pair of rearranged tetranorditerpenoid dimers with a spiroketal core moiety.

6. Pharmacological Activities

Norditerpene, a substance of profound pharmacological significance, manifests diverse primary pharmacological effects and biological activities encompassing cytotoxicity, anti-inflammatory activity, and antibacterial and antiviral actions, as well as antioxidant potential.

6.1. Cytotoxic activity

The anti-tumor activity of numerous norditerpenes has been extensively reported. The cytotoxicity of norditerpenes is the most frequently studied biological activity, and a table listing their cytotoxic activities is provided (Table 13). The cytotoxic activity of compound 208 was found to be the most potent against A549, Hela, and SGC-7901 cell lines, with IC50 values of 0.10 µM, 0.13 µM, and 0.14 µM, respectively [78].

Table 13.

Cytotoxic activity of norditerpenes.

6.2. Antimicrobial Activity

6.2.1. Antibacterial Activity

Inulifolinone D (16) from A. inulifolium can enhance the bactericidal activity against S. aureus. (MIC = 150–75 μg/mL) [10]. Actinomadurol (64) showed high antibacterial activity against pathogenic strains, including Staphylococcus aureus, Rhizophila Kocuria, and Proteus Hauseri, with MICs ranging from 0.39 to 0.78 μg/mL. However, Jbir-65 (63) did not exhibit any antibacterial activity, suggesting that the hydroxyl group at C-7 was responsible for antibacterial activity [25]. Compounds 69–72, 74, and 79–80 from I. Trichantha showed antibacterial activity against both standard and resistant strains of H. pylori, with an MIC of 8–64 μg/mL. In addition, compounds 72 and 74 showed superior antibacterial activity against H. pylori compared to other compounds, with MIC values ranging from 8 to 16 μg/mL. SAR studies have demonstrated that CH3O-12 and 3, 20-epoxy moiety in 17-nor-pimarane diterpenes can function as activating groups, while the sugar moiety at C-2 might an inactivated group. The combination of antibiotic-icacinlactone B with either metronidazole or amoxicillin exhibited notable additive effects (FICI = 0.56–0.75) against the clinical strain HP159, suggesting that combination therapy has the potential to enhance antimicrobial activity, reduce dosage requirements, and mitigate adverse side effects. Compounds 87, 89, 96, 98, and 99 displayed inhibitory activities against E. tarda, M. luteus, P. aeruginosa, V. harveyi, and V. parahemolyticus, with MIC values of 4.0 μg/mL each; compounds 87 and 99 also exhibited activity against the F. graminearum, with MIC values of 2.0 and 4.0 μg/mL, respectively [34]. Compounds 90–91 exhibited comparable MIC values of 8.0 μg/mL against zoonotic pathogenic bacteria, including E. coli, E. tarda, V. harveyi, and V. parahaemolyticus. Compound 93 exhibited potent activity (MIC = 4.0 μg/mL) against the plant pathogen F. graminearum [35]. Salprzelactone (164) showed higher antibacterial activity against A. aerogenes than streptomycin, acheomycin, and ampicillin, as indicated by MIC values of 62.5 μg/mL versus 125 μg/mL, 250 μg/mL, and 125 μg/mL, respectively [55]. The growth of S. aureus was inhibited by citrinovirin (299) at an MIC of 12.4 μg/mL, while it displayed toxicity toward A. salina, with an LC50 of 65.6 μg/mL. Moreover, compound 299 exhibited inhibitory effects ranging from 14.1% to 37.2% against C. Marina, H. Akashiwo, and P.donghaiense at 100 μg/mL; however, it stimulated the growth of S.trochoidea [101]. Compound 531 displayed potent activity against E. tarda, with an MIC value of 16 μg/mL [162,166]. Compounds 555–556 showed moderate antimicrobial activities against S. aureus, 8#MRSA, and 82#MRSA, with MIC values from 1.56 to 6.25 μg/mL [173].

6.2.2. Antifungal Activity

Compounds 333, 335, and 342 displayed antifungal activity against C. neoformans (MIC = 17.5, 12.5, and 10.0 μg/mL, respectively) and C. albicans (MIC = 20, 20, and 12.5 μg/mL, respectively) [116]. Compounds 333 and 342 also demonstrated inhibitory effects on the growth of P. destructans, with MIC values of 7.5 and 15 μg/mL, respectively [116]. Compound 534 showed moderate antifungal activities against C. albicans, with an MIC of 16 μg/mL [162].

6.2.3. Antiviral Activity

The compound eupneria J (118) displayed potent anti-HIV-1 activity (IC50 = 0.31 μM). These findings suggest that the presence of a β-oriented hydroxyl group at C-4 may enhance its anti-HIV-1 activity. Furthermore, it is plausible that the acetoxyl group at C-18, rather than at C-3, contributes to an augmented anti-HIV effect [41]. Compound 276 exhibited antiviral activity against human enterovirus EV71, with an IC50 value of 5.0 μM [87]. Compound 394 exhibited anti-HBV activity by effectively suppressing the secretion of HBsAg and HBeAg, with IC50 values of 0.11 and 0.18 μM, respectively. In addition, it also effectively suppressed HBV DNA replication, with an SI value of 647.2 [56]. Compounds 422–423 showed potent anti-HCV activity, with EC50 values of 7.5 and 6.6 μM, respectively [128]. Compounds 490–491 demonstrated moderate anti-HCV activity, exhibiting EC50 values of 13.0 ± 0.3 μM and 23.6 ± 1.9 μM, respectively [148].

6.3. Anti-Inflammatory

The activation of NLRP3 inflammasome causes pyroptosis and results in the maturation of caspase-1 and the secretion of IL-1β [15]. The anti-NLRP3 inflammasome effects of compound 31 were evaluated by MCC950 (IC50 = 23.1 ± 5.3 µM) as a positive control, which can specifically inhibit NLRP3 inflammasomes. Compound 31 inhibited IL-1β secretion (IC50 = 5.5 ± 3.2 µM) and maturation of caspase-1 in a dose–dependent manner, indicating that cell pyroptosis is prevented, thereby demonstrating its ability to inhibit NLRP3 inflammasome activation [15].

Compound 82 derived from P. malabarica showed anti-inflammatory (anti-5-LOX) effects, with IC50 values of 0.75 mg/mL, more potent than ibuprofen (IC50 = 0.93 mg/mL). In vitro, compared with ibuprofen (selectivity index = 0.44), compound 82 exhibits a higher selectivity index (anti-COX-1IC50/anti-COX-2IC50 = 0.85), indicating fewer side effects. Notably, compound 82 exhibits promising potential against both cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase [30].

The inhibitory potential of compound 279 against 5-LOX (IC50 = 0.92 mg/mL) was found to be higher than ibuprofen (IC50 = 0.96 mg/mL) [89].

Compound 110 showed significant inhibition, with an IC50 value of 14.7 ± 1.8 μM, surpassing the potency of PDTC (Pyrrolidinedithiocarbamate, IC50 = 26.3 µM), a well-established positive control for an NF-κB inhibitor [39].

Compound 190 from C. sinensis exhibited effective inhibition of NF-κB activity (IC50 4.12 ± 0.61 µM) [73]. Salvialba acid (163) has been shown to possess anti-inflammatory effects on TNF-α-induced vascular inflammation in HAECs (human aortic endothelial cells) [60].

Compound 208, obtained from the twigs and leaves of C. fortune, dose–dependently inhibited TNF-α-induced NF-κB activation with an IC50 value of 0.10 μM, which was similar to the inhibitory effect of the positive control MG132 (a proteasome inhibitor, IC50 = 0.15 μM). These results suggest that the tropone moiety is important for the cytotoxicity and the inhibition of NF-κB signaling [78].

Compounds 255, 261, and 269 also displayed inhibitory effects on NF-κB with inhibitory rates of 28.6%, 25.1%, and 12.5% in a dose of 50 µM compared to the positive control PDTC (IC50 = 37 µM) [82,86].

Compounds 494–496 and 500 demonstrated moderate inhibitory activities against NF-κB activation in RAW264.7 macrophages, with IC50 values of 15, 25, 19, and 4 μM, respectively [149,150,151]. Compound 8 was the most effective compound in inhibiting LPS-induced nitric oxide (NO) production (IC50 = 3.56 μM) in T. orientalis. Moreover, it attenuated the expression of iNOS and COX-2 at both mRNA and protein levels by inhibiting LPS-induced degradation of I-κBα and activation of NF-κB, as well as reducing ERK phosphorylation [7].

Compounds 324 and 325 exerted pronounced inhibition of NO production in LPS-induced macrophages (RAW 264.7), with IC50 values of 7.50 and 6.49 μM, respectively [113].

Compound 437 showed a significant anti-inflammatory effect on LPS-induced NO production in RAW264.7 cells (IC50 = 21.0 μM) [12].

Compounds 445–448 showed potent inhibitory activity against LPS-induced production of NO and TNF-α in RAW264.7 cells, with IC50 values of below 25 µM [40,137].

Compounds 373, 374, 378, and 480 exhibited potent inhibition of NO release in the cell culture medium of LPS-stimulated macrophages. Furthermore, they significantly inhibited iNOS expression in J774A.1 macrophages at doses of 50–12.5 μM [122].

Compounds 493 and 508 exhibited potent inhibitory effects on LPS-stimulated NO releases and pro-inflammatory mediators, with IC50 values of 4.9 and 12.60 μM, respectively, by suppressing iNOS and COX-2 expressions to prevent NO production [139]. 13-epi-scabrolide C (263) inhibited the production of IL-12 and IL-6 in LPS-stimulated BMDCs (bone marrow-derived cells, IC50 = 5.30 ± 0.21 and 13.12 ± 0.64 μM, respectively). This suggests that the C-13 methoxyl moiety may play an important role in anti-inflammatory activity [82].

Scrodentoids H,I (307–308) exert anti-inflammatory effects by reducing LPS-induced inflammation and inhibiting the JNK/STAT3 pathway in macrophages. STAT proteins play a pivotal role in modulating cytokine-mediated inflammatory responses, and STAT3 is highly correlated with inflammatory responses. In response to inflammatory stimuli, STAT3 acts as a transcription factor that directly governs the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Scrodentoids H and I might be beneficial in the treatment of inflammatory diseases, like ulcerative colitis and atherosclerotic diseases [105].

Sinusiaetone A (316) from S. siaesensis exhibited significant inhibition against LPS-induced inflammation in BV-2 microglia at a concentration of 20 μM and also decreased the mRNA levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-1β [109].

6.4. Antioxidative Activity

Compound 82 showed antioxidant activity comparable to α-tocopherol, exhibiting an IC50 value of approximately 0.6 mg/mL for DPPH scavenging activity, and it can serve as a natural alternative to synthetic antioxidants [30].

The radical quenching analysis revealed that compound 279 exhibited a higher antioxidant activity (IC50 value of 0.60 mg/mL) compared to α-tocopherol. This suggests the potential of compound 279 as a natural antioxidant in future applications, attributed to its low hydrophobicity and spatial variability [89].

6.5. α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity

Compounds 2, 298, and 363 displayed an inhibitory effect on α-glucosidase and were evaluated by p-nitro-phenyl-α-D-glucopyranoside as the substrate and acarbose as a positive control. Compound 2 showed a moderate inhibition, with IC50 values of 282 μM, surpassing the efficacy of the positive control acarbose (1.33 mM) [2]. Compound 298 displayed significant inhibition, with an IC50 value of 64.05 ± 1.59 μg/mL [100]. Compound 363 showed a moderate inhibition on α-glucosidase (IC50 = 7.94 μM). At the same time, the inhibition kinetics of compound 363 were studied via a noncompetitive inhibition mechanism, and the inhibition kinetics parameter (Ki) was 10.8 μM [120].

6.6. Cell Proliferation Activity

Compounds 100, 477, and 473 exhibited inhibitory effects on concanavalin A-induced T cell proliferation (IC50 = 13.6, 1.66, and 2.09 μM, respectively), as well as lipopolysaccharide-induced B cell proliferation (IC50 = 22.4, 1.37, and 3.31 μM, respectively), without exhibiting any obvious cytotoxicity to T cells and B cells [37,146]. Compounds 258 and 261 showed strong inhibitory activities against Con A-induced T lymphocyte proliferation, with IC50 values of 23.7 and 8.69 μM, respectively. The remarkable enhancement in activity can be attributed to the configurational inversion at C-5 in compound 261 [81].

Compound 515 has been confirmed to promote the proliferation and differentiation of umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells into keratinocyte-like cells at a concentration of 10 μM [158].

6.7. Other Activities

Compounds 34, 43, and 55 demonstrated the NGF-mediated promotion of neurite outgrowth on PC12 cells at a concentration of 10 μM [17]. Compound 509 showed a potent neuroprotective effect against a hydrogen peroxidation-induced reduction in cell viability in PC12 cells at a concentration of 1 μM [151,154]. Compound 58 displayed the most effective inhibitory effect on osteoclast differentiation, exhibiting IC50 values of 0.7 μM. It downregulated the expression levels of osteoclast-related genes and promoted the apoptosis of osteoclasts. Compounds 58–60 inhibited osteoclast formation, with IC50 ranging from 0.7 to 4.0 μM, thereby demonstrating their antiosteoporosis effects [23]. Compounds 95–97 showed potent biological activities against some marine organisms. Compound 97 was highly toxic to A. salina, with an LC50 value of 6.36 μM. Moreover, compound 96 displayed significant toxicity toward C. marina and H. akashiwo (LC50 = 0.81 and 2.88 μM, respectively), while compound 95 exhibited higher effectiveness against Alexandrium sp., with an LC50 value of 8.73 μM [36]. Compounds 143 and 152–154 selectively inhibited BChE, with IC50 values of 2.4, 7.9, 50.8, and 0.9 µM, respectively. Moreover, compounds 143 and 154 moderately inhibited AChE, with IC50 values of 329.8 μM and 342.9 μM, respectively [54]. Compounds 249–252 effectively inhibited Th17 differentiation, exhibiting IC50 values ranging from 2 to 18.07 μM. Compounds 250–251 were more effective than the positive control digoxin, which is a classical inhibitor of Th17 differentiation [80]. Compound 364 inhibited the acetyl transfer activity of M. tuberculosis GlmU, with an IC50 value of 41.85 μM, representing a novel therapeutic target for tuberculosis [120]. Compound 371 can significantly inhibit the formation of macrophage foam cells induced by oxidized low-density lipoprotein, suggesting its potential as a protective agent against atherosclerosis [134]. Compounds 454–456 displayed antifobrotic activities on TGF-β1-induced rat renal proximal tubular cells, effectively attenuating the excessive production of collagen I and α-SMA [141]. Compound 505 exhibited inhibitory activities against PTP1B and was a moderate time-dependent inactivator of PTP1B, with ki value of 0.11 M−1 s−1 [6]. Compound 539 exhibited a mortality rate of 30% in P. redivivus and 28% in C. elegans within a 24 h period at a concentration of 400 mg/L, whereas the control group (5% acetone) only resulted in a mortality rate of 1.5% during the same time frame [161]. The anti-AD activity of compound 547 was comparatively weaker than memantine (p < 0.05), and it can be regarded as an anti-AD compound candidate [170].

7. Conclusions

This review summarized 557 compounds among C19, C18, C17, and C16 norditerpenes from 2010–2023. Obviously, C19 norditerpenes are the characteristic and main bioactive components of norditerpenes. Lamiaceae plants contain abundant norditerpenes, especially Isodon and Salvia genera. The Lamiaceae plant Salvia miltiorrhiza possesses abundant C19 norditerpenes, and the Cephalotaxaceae plant Cephalotaxus fortunei possesses abundant cephalotane-type norditerpenes.

Most norditerpenes exhibited anti-tumor, anti-inflammatory, anti-bacterial, and antioxidant properties, as well as inhibitory effects against HIV and α-glucosidase. Recent research suggests that norditerpenes may be a possibility for the future development of anti-tumor drugs. For example, euphorane C (139) inhibited the proliferation of K562 cells (IC50 = 3.59 µM) and provided the possibility for developing anti-leukemia drugs. Cephinoid H (208) isolated from C. fortunei showed the strongest cytotoxic activities, with IC50 values of 0.10, 0.13, and 0.14 µM against cell lines A549, Hela, and SGC-7901, respectively. It can be used as a candidate drug for treating various types of cancer. In Table 14, most norditerpenes have inhibitory effects on lung cancer, breast cancer, and cervical cancer cells. We should find appropriate targets to explore their mechanisms and focus on their in vivo activities in the future. With the rapid development of nanomaterials, we can combine effective norditerpenoids with them to improve their targeting and efficacy. Due to antibiotic resistance and side effects, it is meaningful to discover new antibiotics. Actinomadurol (64) has good antibacterial activity and provides the possibility for the discovery of antibiotics. At the same time, the structure–activity relationship was studied, which found that the hydroxyl group at C-7 affected antibacterial activity. CH3O-12 and the 3,20-epoxy moiety in 17-nor-pimarane diterpenes can function as activating groups, while the sugar moiety at C-2 might be an inactivated group. This is beneficial for the design and synthesis of new antibacterial drugs. Norditerpenes produce anti-inflammatory effects by influencing recognized markers of inflammatory processes such as IF, NO levels, nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TGF-α). In the future, norditerpenes may be a useful and safe method for treating inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, and can play a similar role as ibuprofen and dexamethasone.

Table 14.

Anti-inflammatory activity of norditerpenes.

Although current research has shown that these compounds exhibit various biological activities, most of the research mainly focuses on in vitro cell activity assays. It is necessary to investigate their in vivo activities. Further clinical trials are crucial to confirm the pharmacological effects of norditerpenes in order to fully illustrate their therapeutic effects on diseases. We hope that this review can promote research on norditerpenes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and writing the manuscript draft, N.Z.; data analysis, Q.Z.; collecting the references, Q.Y. and G.F.; writing—review and editing, W.S.; project administration and funding acquisition, W.W. and B.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant Nos. 82074122 and 82174078); the Ungraduated Students Research Innovative Program of Hunan University of Chinese Medicine (grant No. 2022CX71); Key Research and Development Programs of Hunan Science and Technology Department (grant No. 2023SK2046); Research Foundation of Education Bureau of Hunan Province (grant No. 23A0280).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Source databases for these publications include the Science Citation Index (SCI), SCI Expanded.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| A549 | Human non-small cell lung cancer cells |

| AGS | Human gastric adenocarcinoma cells |

| ARE | Antioxidant response element |

| BGC-823 | Human gastric adenocarcinoma cells |

| BMDCs | Bone marrow-derived cells |

| COXs | Cyclooxygenases |

| Con A | Knife-beetle protein A |

| ED50 | Median effective dose |

| GlmU | GlcNAc-P uridyltransferase |

| HepG2 | Human hepatocellular carcinoma cells |

| Hela | Human cervical carcinoma cells |

| Huh-7 | Human hepatocellular carcinoma cells |

| HL-60 | Human promyelocytic leukemia cells |

| HT-29 | Human colon cancer cells |

| HCTs | Human colon cancer cells |

| HAECs | Human aortic endothelial cells |

| iNOS | Inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| IC50 | 50% inhibiting concentration |

| ICAM-1 | Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 |

| ILs | Interleukins |

| JNK | c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase |

| KBs | Human oral epidermoid carcinoma cells |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MIC | Minimum inhibitory concentration |

| MCF-7 | Human breast cancer cells |

| MDA-MB | Triple-negative breast cancer cells |

| MG132 | A proteasome inhibitor |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa B |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| NGF | Nerve growth factor |

| PANC-1 | Human pancreatic cancer cells |

| PDTC | Pyrrolidinedithiocarbamate |

| SMMC-7721 | Human hepatocarcinoma cells |

| SW-480 | Human colon cancer cells |

| SGC-7901 | Human stomach cancer cells |

| SK-BR-3 | Human breast cancer cells |

| SKOV3 | Human ovarian cancer cells |

| STAT | Signal transducers and activators of transcription |

| T-47D | Human breast duct cancer cells |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-α |

| TCM | Traditional Chinese medicine |

| VCAM-1 | Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 |

References

- Shen, Y.; Liang, W.J.; Shi, Y.N.; Kennelly, E.J.; Zhao, D.K. Structural diversity, bioactivities, and biosynthesis of natural diterpenoid alkaloids. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2020, 37, 763–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, X.Q.; Bai, J.; Hu, X.L.; Wu, X.; Xue, C.M.; Han, A.H.; Su, G.Y.; Hua, H.M.; Pei, Y.H. Penioxalicin, a novel 3-nor-2,3-seco-labdane type diterpene from the fungus Penicillium oxalicum TW01-1. Tetrahedron Lett. 2015, 56, 5013–5016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.L.; Liu, W.; Han, S.Y.; Zhang, J.; Xu, W.; Li, Q.; Cheng, Z.B. Penitholabene, a rare 19-nor labdane-type diterpenoid from the deep-sea-derived fungus Penicillium thomii YPGA3. Fitoterapia 2020, 146, 104691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.L.; Yang, X.Y.; Zhang, X.K.; Song, Z.T.; Liu, F.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Jin, D.Q.; Xu, J.; Lee, D.; et al. Bioactive terpenoids from Euonymus verrucosus var. pauciflorus showing no inhibitory activities. Bioorg. Chem. 2019, 87, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Linuma, M.; Wang, J.S.; Oyama, M.; Ito, T.; Kong, L.Y. Terpenoids from Chloranthus serratus and their anti-inflammatory activities. J. Nat. Prod. 2012, 75, 694–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, T.T.; Zhao, J.; Shi, X.; Hu, S.C.; Gao, K. Norditerpenoids from Agathis macrophylla. Food Chem. 2012, 131, 972–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.H.; Li, H.; Wu, Q.; Lee, H.J.; Ryu, J.H. A new labdane diterpenoid with anti-inflammatory activity from Thuja orientalis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 146, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbinot, R.B.; Oliveira, J.A.M.D.; Bernardi, D.I.; Melo, U.Z.; Zanqueta, E.B.; Endo, E.H.; Ribeiro, F.M.; Volpato, H.; Figueiredo, M.C.; Back, D.F.; et al. Structural characterization and biological evaluation of 18-nor-ent-labdane diterpenoids from Grazielia gaudichaudeana. Chem. Biodivers. 2019, 16, e1800644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshinori, S.; Sachie, M.; Suyatno, S.; Motoo, T. Nine new norlabdane diterpenoids from the leaves of Austroeupatorium inulifolium. Helv. Chim. Acta 2011, 94, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacon-Morales, P.A.; Amaro-Luis, J.M.; Fermin, L.B.R.; Peixoto, P.A.; Deffieux, D.; Pouysegu, L.; Quideau, S. Preparation and bactericidal activity of oxidation derivatives of austroeupatol, an ent-nor-furano diterpenoid of the labdane series from Austroeupatorium inulifolium. Phytochem. Lett. 2019, 29, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Luo, J.G.; Shan, S.M.; Wang, X.B.; Luo, J.; Yang, M.H.; Kong, L.Y. Amomaxins A and B, two unprecedented rearranged labdane norditerpenoids with a nine-membered ring from Amomum maximum. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 1572–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; Xiao, L.G.; Bi, L.S.; Si, Y.; Zhang, X.M.; Chen, J.H.; Liu, H.Y. Hedychins E and F: Labdane-type norditerpenoids with anti-Inflammatory activity from the rhizomes of Hedychium forrestii. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 6936–6939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.N.; Zhang, J.Z.; Li, X.; Wang, X.N.; Xie, C.F.; Zhou, J.C.; Lou, H.X. Pallambins A and B, unprecedented hexacyclic 19-nor-secolabdane diterpenoids from the Chinese liverwort Pallavicinia ambigua. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 1102–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.M.; Jiang, W.Q.; Feng, Q.; Lu, H.; Zhou, Y.P.; Liao, J.; Wang, Q.T.; Sheng, G.Y. Identification of 15-nor-cleroda-3,12-diene in a Dominican amber. Org. Geochem. 2017, 113, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, D.W.; Xiong, F.; Cheng, B.; Zhou, Y.L.; Zeb, M.A.; Tang, P.; Pang, W.H.; Zhang, R.H.; Li, X.L.; Zhang, X.J.; et al. Callintegers A and B, unusual tricyclo[4.4.0.09,10]tetradecane clerodane diterpenoids from Callicarpa integerrima with inhibitory effects on NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J. Nat. Prod. 2022, 85, 2675–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, B.A.; Firme, C.L.; Maciel, M.A.M.; Kaiser, C.R.; Schilling, E.; Bortoluzzi, A.J. Experimental and NMR theoretical methodology applied to geometric analysis of the bioactive clerodane trans-dehydrocrotonin. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2014, 25, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, M.F.; Pan, Y.H.; Hu, R.; Yuan, F.Y.; Huang, D.; Tang, G.H.; Li, W.; Yin, S. Highly modified nor-clerodane diterpenoids from Croton yanhuii. Fitoterapia 2021, 153, 104979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.H.; Ning, D.S.; Wu, X.D.; Huang, S.S.; Li, D.P.; Lv, S.H. New clerodane diterpenoids from the twigs and leaves of Croton euryphyllus. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 25, 1329–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, M.F.; Hu, R.; Liu, Y.X.; Fan, R.Z.; Xie, X.L.; Yin, S. Two highly oxygenated nor-clerodane diterpenoids from Croton caudatus. J. Asian. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 22, 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhang, P.L.; Zhou, M.X.; Shen, T.; Zou, Y.X.; Lou, H.X.; Wang, X.N. New nor-clerodane-type furanoditerpenoids from the rhizomes of Tinospora capillipes. Phytochem. Lett. 2016, 15, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, G.H.; Xue, J.J.; Liang, W.L.; Yang, S.J. Three new bioactive diterpenoids from the roots of Croton crassifolius. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 35, 1421–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, H.W.; Luo, J.G.; Zhu, M.D.; Shan, S.M.; Kong, L.Y. Teucvisins A-E, five new neo-clerodane diterpenes from Teucrium viscidum. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2014, 62, 472–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.; Luo, X.K.; Yin, Z.Y.; Xu, J.; Gu, Q. Diterpenoids from the aerial parts of Flueggea acicularis and their activity against RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 94, 103453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Guo, P.Y.; Liu, A.J.; Sui, S.Y.; Shi, S.; Guo, S.X.; Dai, J.G. Aquilariaenes A–H, eight new diterpenoids from Chinese eaglewood. Fitoterapia 2019, 133, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, B.; Kim, B.Y.; Cho, E.J.; Oh, K.B.; Shin, J.H.; Goodfellow, M.; Oh, D.C. Actinomadurol, an antibacterial norditerpenoid from a rare actinomycete, Actinomadura sp. KC 191. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 1886–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, B.; Zhao, M.; Wu, Z.L.; Onakpa, M.M.; Burdette, J.E.; Che, C.T. 19-nor-pimaranes from Icacina trichantha. Fitoterapia 2020, 144, 104612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.M.; Zhou, J.F.; Zeng, L.P.; Xu, J.C.; Onakpa, M.M.; Duan, J.A.; Che, C.T.; Bi, H.K.; Zhao, M. Pimarane-derived diterpenoids with anti-Helicobacter pylori activity from the tuber of Icacina trichantha. Org. Chem. Front. 2021, 8, 3014–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Onakpa, M.M.; Chen, W.L.; Santarsiero, B.D.; Swanson, S.M.; Burdette, J.E.; Asuzu, I.U.; Che, C.T. 17-Norpimaranes and (9βH)-17-norpimaranes from the tuber of Icacina trichantha. J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 78, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.X.; Li, B.; Ye, J.; Zhang, W.D.; Shen, Y.H.; Yin, J. A new norditerpenoid from Euonymus grandiflorus Wall. Nat. Prod. Res. 2013, 27, 1716–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joy, M.; Chakraborty, K. An unprecedented antioxidative isopimarane norditerpenoid from bivalve clam, Paphia malabarica with anti-cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase potential. Pharm. Biol. 2017, 55, 819–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.N.; Bashyal, B.P.; Wijeratne, E.M.K.; U'Ren, J.M.; Liu, M.P.; Gunatilaka, M.K.; Arnold, A.E.; Gunatilaka, A.A.L. Smardaesidins A-G, isopimarane and 20-nor-isopimarane diterpenoids from Smardaea sp., a fungal endophyte of the moss Ceratodon purpureus. J. Nat. Prod. 2011, 74, 2052–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Lecce, R.; Masi, M.; Linaldeddu, B.T.; Pescitelli, G.; Maddau, L.; Evidente, A. Bioactive specialized metabolites produced by the emerging pathogen Diplodia olivarum. Beilstein. Archi. 2020, 2020, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, H.; Sebe, M.; Nagaki, M.; Eguchi, K.; Kagiyama, I.; Hitora, Y.; Frisvad, J.C.; Williams, R.M.; Tsukamoto, S. Taichunins A-D, Norditerpenes from Aspergillus taichungensis. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 1377–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.D.; Li, X.M.; Li, X.; Xu, G.M.; Liu, Y.; Wang, B.G. Aspewentins D–H, 20-nor-isopimarane derivatives from the deep sea sediment-derived fungus Aspergillus wentii SD-310. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 1347–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.D.; Lin, X.; Li, X.M.; Xu, G.M.; Liu, Y.; Wang, B.G. 20-nor-isopimarane epimers produced by Aspergillus wentii SD-310, a fungal strain obtained from deep sea sediment. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, F.P.; Liang, X.R.; Liu, X.H.; Ji, N.Y. Aspewentins A–C, norditerpenes from a cryptic pathway in an algicolous strain of Aspergillus wentii. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 429–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.P.; Li, J.; Zhao, Z.Z.; Li, X.Y.; Liu, S.L.; Wang, Q.Y.; Liu, J.K. Diterpenes with bicyclo[2.2.2]octane moieties from the fungicolous fungus Xylaria longipes HFG1018. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2020, 18, 2410–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Li, X.M.; Li, X.D.; Xu, G.M.; Liu, Y.; Wang, B.G. 20-Nor-isopimarane cycloethers from the deep-sea sediment-derived fungus Aspergillus wentii SD-310. RSC Adv. 2016, 79, 75981–75987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhao, J.J.; Chen, J.L.; Zhu, L.P.; Wang, D.M.; Jiang, L.; Yao, D.P.; Zhao, Z.M. Diterpenoids from aerial parts of Flickingeria fimbriata and their nuclear factor-kappaB inhibitory activities. Phytochemistry 2015, 117, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.L.; Zhao, Z.M.; Xue, X.; Tang, G.H.; Zhu, L.P.; Yang, D.P.; Jiang, L. Bioactive norditerpenoids from Flickingeria fimbriata. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 14447–14456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.J.; Dai, W.F.; Liu, D.; Jiang, M.Y.; Zhang, Z.J.; Chen, X.Q.; Chen, C.H.; Li, R.T.; Li, H.M. Bioactive ent-isopimarane diterpenoids from Euphorbia neriifolia. Phytochemistry 2020, 175, 112373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.X.; Xie, C.F.; An, L.J.; Yang, X.Y.; Xi, Y.R.; Yuan, S.; Zhang, C.Y.; Tuerhong, M.; Jin, D.Q.; Lee, D.H.; et al. Bioactive diterpenoids from the stems of Euphorbia royleana. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadir, A.; Zheng, G.J.; Zheng, X.F.; Jin, P.F.; Maiwulanjiang, M.; Gao, B.; Aisa, H.A.; Yao, G.M. Structurally diverse diterpenoids from the roots of Salvia deserta based on nine different skeletal types. J. Nat. Prod. 2021, 84, 1442–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.W.; Liu, X.; Xie, D.; Chen, R.D.; Tao, X.Y.; Zou, J.H.; Dai, J.G. Two new diterpenoids from cell cultures of Salvia miltiorrhiza. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2013, 61, 576–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.; Li, L.; Wang, D.D.; Wang, H.Q.; Liu, C.; Li, B.M.; Yan, Y.; Fang, L.H.; Du, G.H.; Chen, R.Y. Isolation and bioactivity of diterpenoids from the roots of Salvia grandifolia. Phytochemistry 2015, 116, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Adhikari, A.; Choudhary, M.I.; Ayatollahi, S.A.; Atta-Ur-Rahman. New adduct of abietane-type diterpene from Salvia leriifolia Benth. Nat. Prod. Res. 2016, 30, 1511–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eghtesadi, F.; Farimani, M.M.; Hazeri, N.; Valizadeh, J. Abietane and nor-abitane diterpenoids from the roots of Salvia rhytidea. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alizadeh, Z.; Farimani, M.M.; Parisi, V.; Marzocco, S.; Ebrahimi, S.N.; Tommasi, N.D. Nor-abietane diterpenoids from Perovskia abrotanoides roots with anti-inflammatory potential. J. Nat. Prod. 2021, 84, 1185–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Wang, S.X.; Chen, Y.X. Abietane diterpenoids with potent cytotoxic activities from the resins of Populus euphratica. Nat. Prod. Commune 2019, 14, 1934578X19850029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.H.; Li, Y.; Wu, X.D.; He, J.; Chen, X.Q.; Xu, G.; Peng, L.Y.; Zhao, Q.S. Norditerpenoids from Salvia castanea Diels f. pubescens. Fitoterapia 2012, 83, 1072–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Peng, Y.; Li, L.Z.; Gao, P.Y.; Gao, C.; Xia, S.X.; Song, S.J. Two new abietane diterpenoids from the roots of Tripterygium wilfordii Hook. f. Helv. Chim. Acta 2013, 96, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.L.; Zou, M.F.; Chen, B.L.; Yuan, F.Y.; Zhu, Q.F.; Zhang, X.; Lin, Y.; Long, Q.D.; Liu, W.L.; Liao, S.G. Euphorane C, an unusual C17-norabietane diterpenoid from Euphorbia dracunculoides induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human leukemia K562 cells. Arab. J. Chem. 2022, 15, 104203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.M.; Li, H.L.; Huang, G.L.; Chen, Y.G. A new abietane mono-norditerpenoid from Podocarpus nagi. Nat. Prod. Res. 2017, 31, 844–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lusarczyk, S.; Senol Deniz, F.S.; Abel, R.; Pecio, Ł.; Pérez-Sánchez, H.; Cerón-Carrasco, J.P.; Den-Haan, H.; Banerjee, P.; Preissner, R.; Krzyżak, E.; et al. Norditerpenoids with selective anti-cholinesterase activity from the roots of Perovskia atriplicifolia Benth. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.L.; Wang, X.Z.; Xiao, J.; Luo, X.H.; Yao, X.J.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Chen, Y.J.; Crews, P.; Wu, Q.X. New abietane diterpenoids from the roots of Salvia przewalskii. Tetrahedron 2013, 69, 6687–6692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.Q.; He, Y.F.; Li, G.; Liu, Y.J.; Gao, W.; Huang, L.Q. Effects of combined Eelicitors on tanshinone metabolic profiling and SmCPS expression in Salvia miltiorrhiza hairy root culture. Molecules 2013, 18, 7473–7485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, K.; Zou, J.; Wang, Y.X.; Zhao, C.L.; Ye, J.H.; Zhang, J.J.; Pan, L.T.; Zhang, H.J. Rubesanolides F and G: Two novel lactone-type norditerpenoids from Isodon rubescens. Molecules 2021, 26, 3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Zhang, S.D.; Li, Y.L.; Yang, X.W.; Zeng, H.W.; Li, H.L.; Zhang, W.D. Abieseconordines A and B, two novel norditerpenoids with a 18-nor-5,10: 9,10-disecoabietane skeleton from Abies forrestii. Helv. Chim. Acta 2012, 95, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.J.; Xiong, J.; Liu, S.T.; Pan, L.L.; Hu, J.F. ent-Abietane-type and related seco-/nor-diterpenoids from the rare chloranthaceae plant Chloranthus sessilifolius and their nntineuroinflammatory activities. J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 78, 1635–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.T.; Ma, S.L.; Lou, H.X.; Zhu, R.X.; Sun, L.R. Two novel abietane norditerpenoids with anti-inflammatory properties from the roots of Salvia miltiorrhiza var. alba. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 7106–7109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.G.; Yan, B.C.; Li, X.N.; Du, X.; Wu, H.Y.; Zhan, R.; Li, Y.; Pu, J.X.; Sun, H.D. 6,7-Seco-ent-kaurane-type diterpenoids from Isodon eriocalyx var. laxiflora. Tetrahedron 2014, 70, 7445–7453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Du, X.; Pang, G.; Shi, Y.M.; Wang, W.G.; Zhan, R.; Kong, L.M.; Li, X.N.; Li, Y.; Pu, J.X. Ternifolide A, a new diterpenoid possessing a rare macrolide motif from Isodon ternifolius. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 3210–3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueno, A.K.; Barcellos, A.F.; Costa-Silva, T.A.; Mesquita, J.T.; Ferreira, D.D.; Tempone, A.G.; Romoff, P.; Antar, G.M.; Lago, J.H.G. Antitrypanosomal activity and evaluation of the mechanism of action of diterpenes from aerial parts of Baccharis retusa. Fitoterapia 2018, 125, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faiella, L.; Piaz, F.D.; Bader, A.; Braca, A. Diterpenes and phenolic compounds from Sideritis pullulans. Phytochemistry 2014, 106, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Liang, Y.R.; Chen, S.X.; Wang, W.X.; Zou, Y.K.; Nuryyeva, S.; Houk, K.N.; Xiong, J.; Hu, J.F. Amentotaxins C–V, Structurally diverse diterpenoids from the leaves and twigs of the vulnerable conifer Amentotaxus argotaenia and their cytotoxic effects. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 2129–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, M.L.; Llanos, G.G.; Castanys, S.; Gamarro, F.; Bazzocchi, I.L.; Jimenez, I.A. Terpenoids from Maytenus species and assessment of their reversal activity against a multidrug-resistant Leishmania tropica line. Chem. Biodivers. 2011, 8, 2291–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, H.; Xu, Q.L.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, Z.Y.; Dong, L.M.; Tan, J.W. Two new ent-kaurane diterpenoids from Wedelia trilobata (L.) Hitchc. Phytochem. Lett. 2015, 11, 260–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isyaka, S.M.; Mas-Claret, E.; Langat, M.K.; Hodges, T.; Selway, B.; Mbala, B.M.; Mvingu, B.K.; Mulholland, D.A. Cytotoxic diterpenoids from the leaves and stem bark of Croton haumanianus (Euphorbiaceae). Phytochemistry 2020, 178, 112455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.Q.; Li, S.Q.; Liao, C.C.; Dai, W.F.; Rao, K.R.; Ma, X.R.; Li, R.T.; Chen, X.Q. Structurally diversified ent-kaurane and abietane diterpenoids from the stems of Tripterygium wilfordii and their anti-inflammatory activity. Bioorg. Chem. 2021, 115, 105178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.X.; Sun, L.R.; Feng, F.; Mo, J.X.; Zhu, H.; Yang, B.; He, Q.J.; Gan, L.S. Cytotoxic diterpenoids from the stem bark of Annona squamosa L. Helv. Chim. Acta 2013, 96, 656–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, W.G.; Wu, H.Y.; Liu, M.; Jiang, H.Y.; Du, X.; Li, Y.; Pu, J.X.; Sun, H.D. ent-Kaurene diterpenoids from Isodon phyllostachys. Tetrahedron Lett. 2017, 58, 349–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, R.; Li, X.N.; Du, X.; Wang, W.G.; Dong, K.; Su, J.; Li, Y.; Pu, J.X.; Sun, H.D. Bioactive ent-kaurane diterpenoids from Isodon rosthornii. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 1267–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.B.; Fan, Y.Y.; Gan, L.S.; Zhou, Y.B.; Li, J.; Yue, J.M. Cephalotanins A–D, four norditerpenoids represent three highly rigid carbon skeletons from Cephalotaxus sinensis. Chemistry 2016, 22, 14648–14654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.P.; Zhou, B.; Zimbres, F.M.; Cassera, M.B.; Zhao, J.X.; Yue, J.M. Cephalotane-type norditerpenoids from Cephalotaxus fortunei var. alpine. Chin. J. Chem. 2022, 40, 1177–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.Y.; Xu, J.B.; Liu, H.C.; Gan, L.S.; Ding, J.; Yue, J.M. Cephanolides A–J, cephalotane-type diterpenoids from Cephalotaxus sinensis. J. Nat. Prod. 2017, 80, 3159–3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.P.; Liu, H.C.; Wang, G.C.; Liu, Q.F.; Xu, C.H.; Ding, J.; Fan, Y.Y.; Yue, J.M. 17-nor-Cephalotane-type diterpenoids from Cephalotaxus fortunei. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 1565–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.X.; Fan, Y.Y.; Xu, J.B.; Gan, L.S.; Xu, C.H.; Ding, J.; Yue, J.M. Diterpenoids and lignans from Cephalotaxus fortune. J. Nat. Prod. 2017, 80, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, L.; Zhong, X.H.; Chen, X.J.; Zhang, B.J.; Bao, M.F.; Cai, X.H. Bioactive norditerpenoids from Cephalotaxus fortunei var. alpina and C. lanceolata. Phytochemistry 2018, 151, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, G.; Zhang, H.; Fan, Y.; Liu, H.; Ding, J.; Yue, J.M. Mannolides A–C with an intact diterpenoid skeleton providing insights on the biosynthesis of antitumor Cephalotaxus Troponoids. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 1880–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.P.; Fan, Y.Y.; Deng, W.D.; Zheng, C.Y.; Li, T.; Yue, J.M. Cephalodiones A-D: Compound characterization and semisynthesis by [6+6] cycloaddition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2021, 60, 9374–9378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.X.; Yang, M.; Li, H.; Li, S.W.; Yao, L.G.; Li, G.; Tang, W.; Wang, C.H.; Liang, L.F.; Guo, Y.W. Polycyclic furanobutenolide-derived norditerpenoids from the South China Sea soft corals Sinularia scabra and Sinularia polydactyla with immunosuppressive activity. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 94, 103350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.T.; Nguyen, H.N.; Nguyen, X.C.; Quang, T.H.; Tung, P.T.; Dat, L.D.; Chae, D.; Kim, S.; Koh, Y.S.; Kiem, P.V. Anti-inflammatory norditerpenoids from the soft coral Sinularia maxima. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 23, 228–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L.; Jin, T.Y.; Liu, X.H.; Zhang, J.R.; Shi, X.; Wang, M.F.; Huang, R.F.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, K.C.; Li, G.Q. Sinudenoids A–E, C19-norcembranoid diterpenes with unusual scaffolds from the soft coral Sinularia densa. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 9007–9011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, R.A.; Smith, R.C.; Roizen, J.L.; Jones, A.C.; Virgil, S.C.; Stoltz, B.M. Development of a unified enantioselective, convergent synthetic Aapproach toward the furanobutenolide-derived polycyclic norcembranoid diterpenes: Asymmetric formation of the polycyclic norditerpenoid carbocyclic core by tandem annulation cascade. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 3467–3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.A.L.; von Salm, J.L.; Clark, S.; Ferlita, S.; Nemani, P.; Azhari, A.; Rice, C.A.; Wilson, N.G.; Kyle, D.E.; Baker, B.J. Keikipukalides, furanocembrane diterpenes from the antarctic deep sea octocoral Plumarella delicatissima. J. Nat. Prod. 2018, 81, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Ji, M.; Li, X.D.; Ren, J.W.; Yin, F.L.; van Ofwegen, L.; Yu, S.W.; Chen, X.G.; Lin, W.H. Fragilolides A–Q, norditerpenoid and briarane diterpenoids from the gorgonian coral Junceella fragilis. Tetrahedron 2017, 73, 2518–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Tang, Q.; Huang, J.; Li, T.; Ouyang, H.; Lin, W.H.; Yan, X.J.; Yan, X.; He, S. Sinuscalide A: An antiviral norcembranoid with an 8/8-fused carbon scaffold from the South China Sea soft coral Sinularia scabra. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87, 9806–9814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.W.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, C.M.; Yu, C.; Ding, J.Y.; Li, X.X.; Hao, X.J.; Wang, Q.; Li, S.L. Japodagricanones A and B, novel diterpenoids from Jatropha podagrica. Fitoterapia 2014, 98, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, K.; Krishnan, S.; Joy, M. Antioxidative oxygenated terpenoids with bioactivities against pro-inflammatory inducible enzymes from Indian squid, Uroteuthis (Photololigo) duvaucelii. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 35, 909–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.L.; Chen, L.; Li, Y.H.; Sun, S.K.; Ma, S.G.; Li, Y.; Qu, J. Cassane and nor-cassane diterpenoids from the roots of Erythrophleum fordii. Phytochemistry 2020, 174, 112343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamikawa, S.; Oshimo, S.; Ohta, E.; Nehira, T.; Omura, H.; Ohta, S. Cassane diterpenoids from the roots of Caesalpinia decapetala var. japonica and structure revision of caesaljapin. Phytochemistry 2016, 121, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Cao, D.H.; Xiao, Y.D.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Wang, J.N.; Shi, X.C.; Xiao, C.F.; Hu, H.B.; Xu, Y.K. Aspidoptoids A–D: Four new diterpenoids from Aspidopterys obcordata vine. Molecules 2020, 25, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.Q.; Lv, J.J.; Wang, Y.M.; Xu, M.; Zhu, H.T.; Wang, D.; Yang, C.R.; Wang, Y.F.; Zhang, Y.J. Phyllanflexoid C: First example of phenylacetylene-bearing 18-nor-diterpenoid glycoside from the roots of Phyllanthus flexuosus. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013, 54, 4670–4674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.L.; Lin, S.; Zhang, S.T.; Pan, L.F.; Chai, C.W.; Su, J.C.; Yang, B.Y.; Liu, J.J.; Wang, J.P.; Hu, Z.X. Modified fusicoccane-type diterpenoids from Alternaria brassicicola. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 1931–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, H.; He, L.M.; Xue, Y.Q.; Jia, J.; Wang, S.B.; Zhu, K.K.; Hong, K.; Cai, Y.S. A new fusicoccane-type norditerpene and a new indone from the marine-derived fungus Aspergillus aculeatinus WHUF0198. Chem. Biodivers. 2021, 18, e2100562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bie, Q.; Chen, C.M.; Yu, M.Y.; Guo, J.R.; Wang, J.P.; Liu, J.J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, H.C.; Zhang, Y.H. Dongtingnoids A–G: Fusicoccane diterpenoids from a Penicillium Species. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawakami, S.; Toyoda, H.; Harinantenaina, L.; Matsunami, K.; Otsuka, H.; Shinzato, T.; Takeda, Y.; Kawahata, M.; Yamaguchi, K. Eight new diterpenoids and two new nor-diterpenoids from the stems of Croton cascarilloides. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2013, 61, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, W.J.; Geng, C.A.; Zhang, X.M.; Chen, H.; Yang, C.Y.; Rong, G.Q.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, H.B.; Wang, H.; Zhou, N.J. (±)-Paeoveitol, a pair of new norditerpene enantiomers from Paeonia veitchii. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 424–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.X.; Liu, C.P.; Qi, W.Y.; Han, M.L.; Han, Y.S.; Wainberg, M.A.; Yue, J.M. Eurifoloids A–R, structurally diverse diterpenoids from Euphorbia neriifolia. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 2224–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oanh, V.T.K.; Ha, N.T.T.; Duc, H.V.; Thuc, D.N.; Hang, N.T.M.; Thanh, L.N. New triterpene and nor-diterpene derivatives from the leaves of Adinandra poilanei. Phytochem. Lett. 2021, 45, 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.R.; Miao, F.P.; Song, Y.P.; Liu, X.H.; Ji, N.Y. Citrinovirin with a new norditerpene skeleton from the marine algicolous fungus Trichoderma citrinoviride. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 5029–5031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A.M.; Pierens, G.K.; Forster, L.C.; Winters, A.E.; Cheney, K.L.; Garson, M.J. Rearranged diterpenes and norditerpenes from three Australian Goniobranchus Mollusks. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 447–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.Y.; Sun, D.Y.; Liang, L.F.; Yao, L.G.; Chen, K.X.; Guo, Y.W. Spongian diterpenes from Chinese marine sponge Spongia officinalis. Fitoterapia 2018, 127, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.Q.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Huang, C.; Chen, K.X.; Li, Y.M. Scrodentoids F-I, four C19-norditerpenoids from Scrophularia dentate. Tetrahedron 2016, 72, 8031–8035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, G.H.; Sun, L.Q.; Xu, J.W.; Li, Y.M.; Dunzhu, C.; Zhang, L.Q.; Qian, F. Scrodentoids H and I, a pair of natural epimerides from Scrophularia dentata, inhibit inflammation through JNK-STAT3 axis in THP-1 cells. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2020, 2020, 1842347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San-Martin, A.; Bacho, M.; Nunez, S.; Rovirosa, J.; Soler, A.; Blanc, V.; Leon, R.; Olea, A.F. A novel normulinane isolated from Azorella compacta and assessment of its antibacterial activity. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 2018, 63, 4082–4085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, Y.T.H.; Palfner, G.; Lima, C.; Porzel, A.; Brandt, W.; Frolov, A.; Sultani, H.; Franke, K.; Wagner, C.; Merzweiler, K. Nor-guanacastepene pigments from the Chilean mushroom Cortinarius pyromyxa. Phytochemistry 2019, 165, 112048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidhal, N.; Zhou, X.M.; Chen, G.Y.; Zhang, B.; Han, C.R.; Song, X.P. Chemical constituents of Leucas zeylanica and their chemotaxonomic significance. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2020, 89, 104006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.H.; Li, W.S.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Luo, H.; Wang, J.R.; Zhang, H.Y.; Zeng, Z.R.; Chen, B.; Li, X.W.; Guo, Y.W. Sinusiaetone A, an anti-inflammatory norditerpenoid with a bicyclo[11.3.0]hexadecane nucleus from the Hainan soft coral Sinularia siaesensis. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 5621–5625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.S.; Cheng, Y.B.; Lin, Y.C.; Liaw, C.C.; Chang, J.Y.; Kuo, Y.H.; Shen, Y.C. Nitrogen-containing diterpenoids, sesquiterpenoids, and nor-diterpenoids from Cespitularia taeniata. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 5796–5814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.C.; Lin, C.C.; Chu, Y.C.; Fu, C.W.; Sheu, J.H. Bioactive diterpenes, norditerpenes, and sesquiterpenes from a Formosan soft coral Cespitularia sp. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.Y.; Li, L.Z.; Liu, K.C.; Sun, C.; Sun, X.; Wu, Y.N.; Song, S.J. Natural terpenoid glycosides with in vitro/vivo antithrombotic profiles from the leaves of Crataegus pinnatifida. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 48466–48474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.G.; Li, Z.L.; Bai, J.; Meng, D.L.; Li, N.; Pei, Y.H.; Zhao, F.; Hua, H.M. Anti-inflammatory diterpenoids from the roots of Euphorbia ebracteolata. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 792–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.B.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Ma, S.G.; Qu, J.; Jiang, J.D.; Chen, X.G.; Zhang, D.; Yu, S.S. Terpenoids from the roots of Alangium chinense. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2015, 17, 1025–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.Z.; Liang, X.; Sun, X.; Qi, X.L.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Q.C.; Song, S.J. Bioactive norditerpenoids and neolignans from the roots of Salvia miltiorrhiza. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016, 14, 10050–10057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusman, Y.; Wilson, M.B.; Williams, J.M.; Held, B.W.; Blanchette, R.A.; Anderson, B.N.; Lupfer, C.R.; Salomon, C.E. Antifungal norditerpene oidiolactones from the fungus Oidiodendron truncatum, a potential biocontrol agent for whitenose syndrome in bats. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivon, F.; Retailleau, P.; Desrat, S.; Touboul, D.; Roussi, F.; Apel, C.; Litaudon, M. Isolation of picrotoxanes from Austrobuxus carunculatus using taxonomy-based molecular networking. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 3069–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivon, F.; Retailleau, P.; Desrat, S.; Touboul, D.; Roussi, F.; Apel, C.; Litaudon, M. Sinuhirtone A, an uncommon 17, 19-dinorxeniaphyllanoid, and nine related new terpenoids from the Hainan soft coral Sinularia hirta. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, I.M.; Paola, A.; Perez, M.; Garcia, M.; Blustein, G.; Schejter, L.; Palermo, J.A. Antifouling Diterpenoids from the Sponge Dendrilla Antarctica. Chem. Biodivers. 2022, 19, e202100618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.L.; Wang, C.; Cheng, Z.B.; Tian, X.G.; Jia, J.M.; Cui, Y.L.; Feng, L.; Sun, C.P.; Zhang, B.J.; Ma, X.C. Diterpenoids isolated from Euphorbia ebracteolata roots and their inhibitory effects on α-Glucosidase. J. Nat. Prod. 2017, 80, 3218–3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.Y.; Liao, Y.; Yang, Z.G.; Yang, X.W.; Shen, X.L.; Li, R.T.; Xu, G. Cytotoxic diterpenoids from Salvia yunnanensis. Phytochemistry 2014, 106, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y.Y.; Peng, L.Y.; Yang, X.W.; Pan, Z.H.; Liu, E.D.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Q.S. Diterpenoid constituents of the roots of Salvia digitaloides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 12157–12161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, F.; Zhang, D.W.; Qu, G.W.; Li, G.S.; Dai, S.J. New abietane norditerpenoid from Salvia miltiorrhiza with cytotoxic activities. J. Asian. Nat. Prod. Res. 2012, 14, 913–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Tang, C.P.; Ke, C.Q.; Li, X.Q.; Liu, J.; Gan, L.S.; Weiss, H.; Gesing, E.; Ye, Y. Constituents of Trigonostemon chinensis. J. Nat. Prod. 2010, 73, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.Y.; Zhou, J.; Huang, C.G.; Hu, Q.F.; Huang, X.Z.; Wang, W.; Zhang, L.Z.; Li, G.P.; Xia, F.T. Two novel antiviral terpenoids from the cultured Perovskia atriplicifolia. Tetrahedron 2015, 71, 3844–3849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Tang, C.P.; Mandi, A.; Kurtan, T.; Ye, Y. Trigonostemons G and H, dinorditerpenoid dimers with axially chiral biaryl linkage from Trigonostemon chinensis. Chirality 2020, 32, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.F.; Liu, F.F.; Zhu, Z.D.; Fang, Q.Q.; Qu, S.J.; Zhu, W.L.; Yang, L.; Zuo, J.P.; Tan, C.H. Flueggenoids A–E, new dinorditerpenoids from Flueggea virosa. Fitoterapia 2019, 133, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, C.H.; Cheng, J.C.; Shen, D.Y.; Wu, T.S. Anti-hepatitis C virus dinorditerpenes from the roots of Flueggea virosa. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.Y.; Zhang, C.Y.; Dai, J.J.; Rahman, K.; Zhang, H. Diterpenoids with thioredoxin reductase inhibitory activities from Jatropha multifida. Nat. Prod. Res. 2017, 31, 2753–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, F.R.; Wang, S.W.; Chen, S.R.; Lee, C.Y.; Sheu, J.H.; Cheng, Y.B. Aleuritin, a novel dinor-diterpenoid from the twigs of Aleurites moluccanus with an anti-lymphangiogenic effect. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2020, 18, 7892–7898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Y.Y.; Su, J.; Zhang, Z.J.; Li, L.W.; Fan, M.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, X.D.; Zhao, Q.S. Two new anti-proliferative C18-norditerpenes from the roots of Podocarpus macrophyllus. Chem. Biodivers. 2018, 15, e1800043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.; Ying, S.H.; Li, J.Y.; Chen, H.W.; Zang, Y.; Wang, W.X.; Li, J.; Xiong, J.; Hu, J.F. Phytochemical and biological studies on rare and endangered plants endemic to China. Part XV. Structurally diverse diterpenoids and sesquiterpenoids from the vulnerable conifer Pseudotsuga sinensis. Phytochemistry 2020, 169, 112184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirzania, F.; Farimani, M.M.; Sarrafi, Y.; Ebrahimi, S.N.; Troppmair, J.; Kwiatkowski, M.; Stuppner, H.; Alilou, M. New sesterterpenoids from Salvia mirzayanii Rech.f. and Esfand. stereochemical characterization by computational electronic circular dichroism. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 783292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]