Abstract

The popular tobacco and e-cigarette chemical flavorant (−)-menthol acts as a nonselective, noncompetitive antagonist of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs), and contributes to multiple physiological effects that exacerbates nicotine addiction-related behavior. Menthol is classically known as a TRPM8 agonist; therefore, some have postulated that TRPM8 antagonists may be potential candidates for novel nicotine cessation pharmacotherapies. Here, we examine a novel class of TRPM8 antagonists for their ability to alter nicotine reward-related behavior in a mouse model of conditioned place preference. We found that these novel ligands enhanced nicotine reward-related behavior in a mouse model of conditioned place preference. To gain an understanding of the potential mechanism, we examined these ligands on mouse α4β2 nAChRs transiently transfected into neuroblastoma-2a cells. Using calcium flux assays, we determined that these ligands act as positive modulators (PMs) on α4β2 nAChRs. Due to α4β2 nAChRs’ important role in nicotine dependence, as well as various neurological disorders including Parkinson’s disease, the identification of these ligands as α4β2 nAChR PMs is an important finding, and they may serve as novel molecular tools for future nAChR-related investigations.

1. Introduction

The single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of α4 and β2 receptor subunit genes (CHRNA4 and CHRNB2), which comprise a major nicotinic subtype in the brain (α4β2), are associated with heightened dependence on nicotine and initial subjective responses in both African American and youth populations [1,2]. To date, approved nicotine cessation pharmacotherapies have principally targeted α4β2 nAChRs: partial agonist, varenicline [3,4]; antagonist, bupropion [5,6]. Despite this, smoking cessation rates remain low [7], prompting the need for investigation into pharmacotherapies with a novel mechanism of action that may produce higher cessation rates. Transient receptor potential (TRP) channels have been investigated for their potential involvement in the effects of nicotine [8,9,10]. The reason for this comes from the understanding that menthol, the natural ligand for TRP melastatin 8 (TRPM8) and the most popular and widely used tobacco and e-cigarette flavor, causes several biological effects that contribute to nicotine reward and reinforcement.

One contributing effect is mediated through menthol’s interaction with TRPM8, which results in a cooling sensation that may reduce the harsh throat irritation of nicotine and tobacco [11,12,13,14,15,16]. This may contribute to smokers and vapers inhaling more nicotine, and thus may contribute to elevations in plasma nicotine concentrations [17]. In addition to its counterirritant effects, menthol has been shown to directly facilitate nicotine self-administration. Oral menthol, the TRPM8 partial agonist and cooling agent, WS-23, and cold temperatures (~11 °C) significantly increase nicotine intravenous (i.v.) self-administration in female adolescent rats, compared to nicotine alone or other tastant/odorant cues. Menthol also induces a considerable nicotine extinction burst, re-instates extinguished nicotine-seeking behavior, and acts as a conditioned cue for nicotine [16], suggesting that menthol may have direct effects on nAChRs beyond the sensory effects discussed above. In addition, constellation pharmacology efforts have identified TRPM8 and a7 nAChR co-expression in cold thermosensors from mouse and rat dorsal root ganglia and trigeminal ganglia [18].

In recent years, the direct effects of menthol on nAChRs have begun to be identified. Menthol enhances the nicotine-induced upregulation of nAChRs [19,20] and enhances reward-related behavior in conditioned place preference assays [19], the vapor self-administration of nicotine [21], intravenous self-administration of nicotine [16,22], and nucleus accumbens dopamine release [23]. These findings support the previous findings that menthol may be a cue-reinforcer for nicotine use [24].

Given that menthol is a well-characterized agonist of TRPM8, some have speculated that TRPM8 antagonists may be potential candidates as novel pharmacotherapies for smoking cessation, by directly affecting nicotinic pharmacology or by blocking menthol’s counter-irritant effects in relation to smoke inhalation. A novel class of menthol-derived TRPM8 antagonists has recently been discovered [25]. Based on menthol’s ability to enhance nicotine reward-related behavior, we tested these novel TRPM8 antagonists for their ability to modulate nicotine reward-related behavior using a mouse model of conditioned place preference. Here, we report that one of the most potent TRPM8 antagonists in this class (VBJ104, TRPM8 IC50 of 6 ± 1 nM) enhanced nicotine reward-related behavior, and this was due to its ability to act as a positive modulator (PM) of α4β2 nAChRs.

2. Results

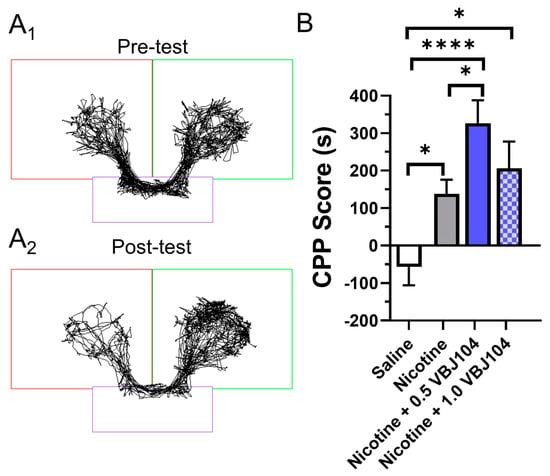

We have previously shown that the TRPM8 agonist menthol enhances nicotine reward-related behavior when combined with nicotine [19], and this likely happens by directly binding to nAChRs [26]. We then decided to examine the impact of a potent TRPM8 antagonist, VBJ104 (Figure 1), on nicotine reward-related behavior in a mouse model of conditioned place preference (CPP). We hypothesized that the potent ligands of TRPM8 that displayed antagonist properties may exert the opposite effect to menthol on nicotine reward-related behavior, and result in a reduction in reward, as opposed to enhancement. We used an unbiased 10-day CPP protocol, which was identical to previously published methods [19,27,28] (Figure 2A). Mice were assigned to cohorts injected with saline, 0.5 mg/kg nicotine, 0.5 mg/kg nicotine plus 0.5 mg/kg VBJ104, or 0.5 mg/kg nicotine plus 1.0 mg/kg VBJ104. Using a one-way ANOVA, we detected a significant overall effect of drug treatment (F(3, 36) = 10.1, p < 0.0001).

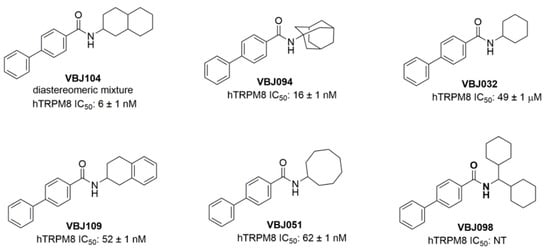

Figure 1.

Structures of novel VBJ series compounds. The IC50 values of hTRPM8 are from a previously published report [25].

Figure 2.

(A1,A2) Representative time-traces for a mouse used in pre- and post-tests in a conditioned place preference assay and assigned to the 0.5 mg/kg nicotine treatment group. (B) Male and female mice were assigned saline, 0.5 mg/kg nicotine, 0.5 mg/kg VBJ104 plus 0.5 mg/kg nicotine, or 1.0 mg/kg VBJ104 plus 0.5 mg/kg nicotine, and used in a CPP assay (via intraperitoneal injections; n = 10 mice per condition, 5 males and 5 females). * p < 0.05; **** p <0.0001.

Using a post hoc Tukey means comparison, we detected the presence of significant place preference with 0.5 mg/kg nicotine (Figure 2B). This is similar to previous reports examining nicotine reward-related behavior in mice [19,27,29]. VBJ104, a mixture of two diastereomers, is composed of >85% of the 2SR, 9RS and 10SR isomers (isolated, hTRPM8 IC50: 1.4 ± 1.0 nM). We chose a dose equivalent to that of nicotine (0.5 mg/kg VBJ104) and previous menthol investigations (1.0 mg/kg VBJ104 [19]). Here, we observed that nicotine plus 0.5 mg/kg VBJ104 produced a significant increase in reward-related behavior when compared to nicotine (p < 0.05; Figure 2B). Nicotine plus 1.0 mg/kg VBJ104 produced a significant CPP compared to saline (p < 0.0001), but not compared to nicotine alone. We observed nearly identical place preference between male and female mice for nicotine (CPP scores of 131.2 and 127.5, respectively) and nicotine plus 0.5 mg/kg VBJ104 (CPP score of 261.5 and 269.8, respectively). Given the lack of sex differences, we combined data for both males and females into Figure 2B.

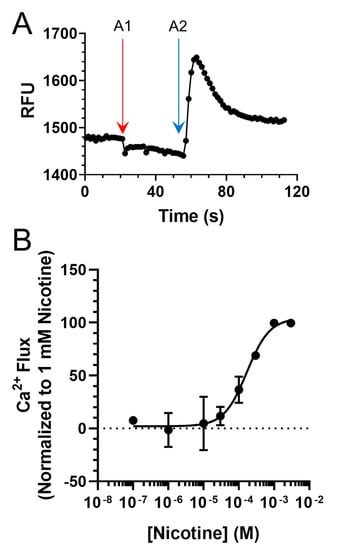

Our behavioral results contradicted our hypothesis, given that we observed an enhancement in nicotine reward-related behavior. To examine how these compounds could enhance nicotine reward-related behavior, we conducted follow-up assays to determine their effects on nAChR pharmacology. To do so, we used a Ca2+ flux assay with neuroblastoma-2a cells transiently transfected with α4β2 nAChRs. While this cell type has been used extensively to study nAChRs in electrophysiology and microscopy assays [30,31,32], it is underutilized in fluorescence plate-reading assays compared to HEK cell lines. Therefore, we created a control nicotine concentration–response curve, and verified that our assay reproduced a nicotine EC50 value (81.1 ± 18.5 µM) consistent with previous literature reports, which utilized a Flexstation platform [26,33,34] (Figure 3). This EC50 indicates that our transient transfection of α4β2 nAChRs and our functional analysis via Ca2+ flux likely measure mostly low-sensitivity α4β2 nAChRs.

Figure 3.

(A) Representative Ca2+ Flux trace from a single 96-well plate seeded with cells transiently transfected with mouse α4β2 nAChRs. A1 and A2 designate drug additions 1 (vehicle) and 2 (100 µM nicotine). (B) Concentration–response of nicotine on neuroblastoma-2a cells transiently transfected with α4β2 nAChRs. Data are mean ± SEM and are normalized to 1 mM nicotine. For B, n = 6 individual experiments.

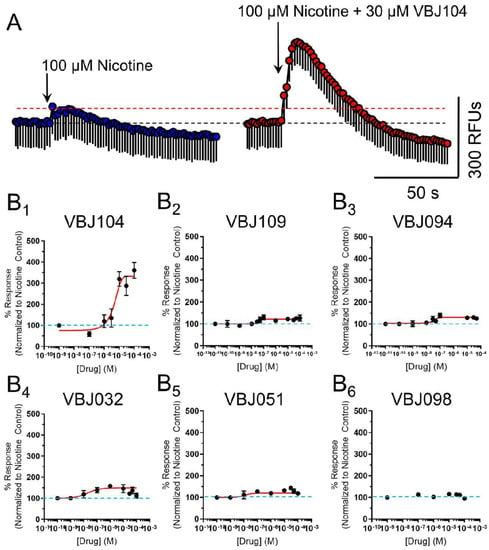

Next, we examined VBJ104 and five analogs (VBJ032, VBJ051, VBJ094, VBJ098, and VBJ109; see Figure 1) for their ability to alter nAChR and nicotine-induced nAChR function. As these compounds are unknowns, we used a two-addition drug application protocol (see Figure 3A), wherein the first addition included the VBJ compounds by themselves (at varying concentrations) and the second addition included the VBJ compound and 100 µM nicotine (~EC60). We observed no α4β2 nAChR agonist activity with any of the VBJ compounds at concentrations up to 100 µM (data not shown).

However, in combination with nicotine, we observed that the compounds enhanced nAChR function in a concentration-dependent manner (Table 1 and Figure 4). Accordingly, we classified these compounds as putative α4β2-positive modulators (PMs). VBJ104, which was most potent as an antagonist for TRPM8, showed the lowest potency as a PM for α4β2 nAChRs (EC50 of 4.6 µM, Table 1), but it exhibited the highest increase in efficacy (361%, Table 1). The remaining VBJ compounds exhibited much higher potencies, with a drastically reduced impact on efficacy compared to VBJ104 (Table 1 and Figure 4). VBJ098 showed no activity as an agonist, PM, or antagonist.

Table 1.

In vitro Ca2+ flux data.

Figure 4.

(A) Representative Ca2+ flux from a 100 µM application of nicotine (left) and a 2 µM application of nicotine in the presence of 30 µM VBJ104 on cells transiently transfected with mouse α4β2 nAChRs. Data are mean ± SEM (triplicate data points). (B1–B6) Concentration–response curves for varying concentrations of VBJ ligands in the presence of 100 µM nicotine. For B1–B6, n = 4–7 individual experiments.

3. Discussion

Menthol acts as an agonist of TRPM8 and a NAM of α4β2 nAChRs [35]. This novel series of compounds were characterized as antagonists of TRPM8 [25], and we found they failed to stimulate α4β2 nAChR activation on their own. However, they increased nAChR function in a concentration-dependent manner. Accordingly, we have deemed these compounds as putative α4β2 PMs. We acknowledge that further investigation needs to be conducted to determine if these ligands act orthosterically or allosterically. Therefore, we chose not to label these ligands as putative positive allosteric modulators (PAMs), and instead limited our designation at this time to putative PMs.

It is important to mention that there exist two types of nAChR PAMs: type-I PAMs potentiate nAChR peak-currents but have little impact on desensitization or inactivation; type-II PAMs potentiate nAChR peak-currents, and also prolong activation by enhancing slow-phase desensitization at the cost of fast-phase desensitization [36]. While we have determined that compounds such as VBJ104 can enhance agonist-induced α4β2 nAChR function, there is a need to examine the impact on desensitization and open–close channel time.

As to how VBJ104 may enhance nicotine reward-related behavior, first we can consider what is known regarding the mechanism of another TRPM8 ligand, menthol. In the case of menthol, its ability to enhance nicotine reward and reinforcement lies in its ability to alter dopamine neuron excitability [19], enhance dopamine release [23], enhance nicotine-induced upregulation of nAChRs [19,20], and act on TRPM8-related mechanisms [13]. While we have no evidence that these VBJ series compounds can alter any of these mechanisms, the ability to act as a PM on α4β2 nAChRs alone can explain how they enhance nicotine reward-related behavior. α4β2 nAChRs have been well-characterized to be critical in nicotine-related reward mechanisms [29,37,38,39]. Thus, enhancing the activity of nicotine on this subtype could have an impact on not only nicotine reward and reinforcement, but also on tolerance and sensitization.

While these ligands have no potential utility in nicotine cessation, α4β2 nAChR PMs (or PAMs) may be useful for other diseases and disorders. PAMs of nAChRs have been implicated for their potential use in treatment of schizophrenia [40] and cognitive disabilities [41]. Given that menthol exerts an effect on all subtypes of nAChRs and many members of the Cys-loop superfamily [35,42,43,44,45,46], follow-up studies for these VBJ compounds’ activity on other nAChR subtypes and ligand-gated ion channels may be necessary.

While the results of this study did not follow our original hypothesis, we have discovered a new series of α4β2 nAChR PMs that may be useful as novel probes. As discussed above, examinations of activity on the major nAChR subtypes, and possibly other members of the Cys-loop superfamily, must be carried out. Additionally, another potential follow-up for this work would be to expand our concentration–response studies to determine if VBJ104 may have a concentration-dependent dual effect (see Figure 4B1). Similarly, there needs to be an expanded dose range for our CPP assays. Currently, the higher dose of VBJ104 (1.0 mg/kg) produces a lesser response than the 0.5 mg/kg dose. Nicotine exhibits an inverted-U dose response in CPP assays, exhibiting a peak of reward-related behavior followed by aversion-related behavior at higher doses. Thus, higher doses of VBJ104 may potentiate nAChR actions to a degree that produces a similar aversion-related response. Thus, while we have failed to identify a novel chemical scaffold for nicotine cessation, we may have discovered compounds that are useful in other areas of interest. This will require careful examination via assays related to learning, memory, and anxiety-related behaviors.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Mice

All experiments were conducted in accordance with the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals provided by the National Institutes of Health. Protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Marshall University. Adult male and female wildtype C57BL/6J mice (3–5 months old) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (https://www.jax.org/strain/000664, accessed on 7 November 2019). Mice were kept on a standard 12/12 h light/dark cycle at 22 °C and given food and water ad libitum.

4.2. Reagents and Dose Selection

The calcium-sensitive fluorescent probe, Calcium 6, was obtained from Molecular Devices (Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Minimum essential medium (MEM) was obtained from Corning. Opti-MEM, penicillin and streptomycin were obtained from Invitrogen Corporation (Grand Island, NY, USA). Nicotine ditartrate dihydrate (product # 415660500) was obtained from Acros Organics (Fair Lawn, NJ, USA). We utilized a nicotine dose of 0.5 mg/kg (with respect to free base) for its previously determined rewarding effect for mice in conditioned place preference assays [19,29]. VBJ series compounds (see Table 1) were prepared as described previously [25]. All molecules were >99.6% pure, as determined by elemental analysis. For pharmacological evaluation, all compounds were initially dissolved in 100% DMSO (0.01 M stocks) due to solubility. Further dilutions of compounds were made in double-distilled H2O or extracellular solution (ECS) (≤100 μM).

4.3. Conditioned Place Preference (CPP) Assays

CPP assays were completed in a three-chamber spatial place preference chamber (Harvard Apparatus, PanLab, dimensions: 47.5 × 27.5 × 47.5 cm) using male and female C57BL/6J mice. Time in chambers was recorded by motion tracking software (SMART 3.0). A 10-day, unbiased protocol identical to previous studies [19,28] was used where drugs (saline, nicotine (0.5 mg/kg), nicotine plus 0.5 mg/kg VBJ104, and nicotine plus 1.0 mg/kg VBJ104) were given immediately before confinement in the right white/grey chamber on drug days, and saline was given immediately before confinement in the left white/black chamber on saline days (via intraperitoneal injections). On day 1, a pre-test was completed wherein mice were placed in the central chamber and allowed free access to the apparatus for 20 min. Mice that spent >65% of the test in one chamber were excluded and the remaining mice were counterbalanced. For counterbalancing, mice were separated into groups of approximately equal bias, similar to previously published CPP methods [47]. No exclusions were necessary for these studies. Following counterbalancing, no initial biases were noted. The mice received their designated drug injections on days 2, 4, 6, and 8, and received saline injections on days 3, 5, 7, and 9. Each conditioning period lasted 20 min. On day 10, a post-test was completed whereby the mice were again placed in the central chamber and allowed free access for 20 min. In total, 5 male and 5 female C57BL/6J mice, 3–5 months old, were used in the CPP assays for each treatment group. Time spent in in the saline-paired chamber was subtracted from time spent in the drug-paired chamber to score the pre-test and post-test. CPP score (or change from baseline) was determined by subtracting the pre-test score from the post-test score. A significant positive CPP score is indicative of reward-related behavior, while a significant reduction is indicative of aversion-related behavior.

No sex differences were observed and data for males and females were combined (see Results for specifics). Data are expressed as a change in baseline preference, which was analyzed using a one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Tukey.

4.4. Neuro-2a Cell Culture and Transient Transfections

Mouse neuroblastoma-2a (neuro-2a) cells were cultured using standard techniques. Cells were maintained in minimum essential medium (MEM, product #10-010-CV obtained from Corning) plus 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 IU/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator. Cells were plated at a density of 1.5–2.0 × 105 cells per well in clear 96-well culture plates previously coated with poly-l-ornithine. At 24 h after plating, neuro-2a cells were transfected with α4 and β2 nAChR subunits using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen) following manufacturer recommendations in Opti-MEM. The plasmid concentrations used for transfection were 5 µg of α4 and β2 (mouse) nAChR subunits for each 96-well plate. At 24 h after transfection, the 96-well plates were washed and replaced with standard culture medium. At 24 h after replacing with standard culture medium, 96-well plates were used in Flexstation assays.

4.5. Calcium 6 Assay (Calcium Accumulation Assay)

The Calcium 6 procedure was carried out via a previously published procedure with minor modifications using calcium 5 [48,49,50]. For this calcium accumulation assay, neuro-2a cells transiently expressing mouse α4β2 nAChRs were used (see above for transfection methods). On the day of the experiment, cells were incubated in the dark for 2 h at 24 °C with 50% Calcium 6 NW dye (Molecular Devices). The plates were then placed into a fluid handling integrated fluorescence plate reader (Flexstation III, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and fluorescence was read at an excitation of 485 nm and emission of 525 nm from the bottom of the plate with changes in fluorescence monitored at ~0.8 s intervals. Baseline fluorescence was monitored for 20 s and then two drug additions (first at 20 s and the second at 60 s) were applied using a Flexstation application speed of 2. At the beginning of the Flexstation assays, each well in the 96-well plate started with 100 µL of solution. For nicotine concentration response, the first addition contained only assay buffer (50 µL), and the second addition contained nicotine (50 µL) at 4× the target concentration.

For assays examining the VBJ compounds, potential PM activity was assessed using the following protocol. For the nicotine control group, assay buffer (50 µL) was added in the first addition, and nicotine (50 µL of a 400 µM solution) was added to achieve a final concentration of 100 µM. Treatment groups received the VBJ compound (50 µL of a 3× solution) in the first addition and then the same nicotine solution (400 µM) with the desired concentration of the VBJ compound (1×) in the second addition. Sham-treated groups were only given assay buffer.

4.6. Calculations

Functional responses were quantified by first calculating the net fluorescence (the difference between control sham-treated and control agonist-treated groups). Results were expressed as a percentage of control (100 μM nicotine). For each PM, six concentrations were used in a series of concentration–response studies. Following transformation to log values, sigmoidal-varied slope curves were fit to data using Prism 9 with no constraints (Graphpad, San Diego, CA, USA). From these curves, EC50 and maximal changes in efficacy were determined for each PM. Functional data were calculated from the number of observations (n) performed in triplicate. Due to the use of log values in calculating the EC50 values, geometric (as opposed to arithmetic) means were calculated for PMs in this study. All EC50 values are expressed as geometric means (95% confidence limits). Due to solubility problems, compound concentrations greater than 100 μM were not used in our concentration–response studies with VBJ compounds. The DMSO concentration at this compound concentration was ≤1%, and this had no effects on basal- or agonist-induced increases in fluorescence intensity.

4.7. Statistical Analysis

All results are presented as mean ± SEM and all statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9. Data were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA. When effects were shown to be significant, a post hoc Tukey test was performed to compare the individual drug treatment groups. For CPP assays, males and females were analyzed separately using a two-way ANOVA. No sex differences were noted; therefore, sexes were combined.

4.8. Supplemental Methods

Supplemental methods and data are available in the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online. Table S1: MDR1-MDCK permeability, Table S2: Stability in mouse liver microsomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.J.H.; methodology, B.J.H.; formal analysis, S.Y.C. and B.J.H.; investigation, S.Y.C., A.T.A. and B.J.H.; resources, V.B.J.; synthesis of reagents, PK profiling and analysis, S.Y.C. and B.J.H.; writing—original draft preparation, B.J.H.; writing—review and editing, S.Y.C., V.B.J. and B.J.H.; funding acquisition, V.B.J. and B.J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Joan C Edwards School of Medicine and School of Pharmacy Collaboration Grant mechanism (BJH and VBJ), the National Institutes of Health NIGMS (U54GM104942-04 to VBJ), a predoctoral fellowship to SYC from the PhRMA Foundation, and by startup funds through the Marshall University Research Corporation (BJH).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research conducted under the guidelines of the US National Institutes of Health and was approved by Marshall University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol #664, approved on 12/06/2016 and renewed 1/1/2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Sample Availability

Samples of the compounds listed in this work are available from the authors.

References

- Li, M.D.; Beuten, J.; Ma, J.Z.; Payne, T.J.; Lou, X.Y.; Garcia, V.; Duenes, A.S.; Crews, K.M.; Elston, R.C. Ethnic- and gender-specific association of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha4 subunit gene (CHRNA4) with nicotine dependence. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005, 14, 1211–12199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ehringer, M.A.; Clegg, H.V.; Collins, A.C.; Corley, R.P.; Crowley, T.; Hewitt, J.K.; Hopfer, C.J.; Krauter, K.; Lessem, J.; Rhee, S.H.; et al. Association of the neuronal nicotinic receptor beta2 subunit gene (CHRNB2) with subjective responses to alcohol and nicotine. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2007, 144, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalak, B.K.; Carroll, F.I.; Luetje, C.W. Varenicline is a partial agonist at α4β2 and a full agonist at α7 neuronal nicotinic receptors. Mol. Pharm. 2006, 70, 801–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coe, J.W.; Brooks, P.R.; Vetelino, M.G.; Wirtz, M.C.; Arnold, E.P.; Huang, J.; Sands, S.B.; Davis, T.I.; Lebel, L.A.; Fox, C.B.; et al. Varenicline: An a4b2 nicotinic receptor partial agonist for smoking cessation. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 3474–3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richmond, R.; Zwar, N. Review of bupropion for smoking cessation. Drug Alcohol. Rev. 2003, 22, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slemmer, J.E.; Martin, B.R.; Damaj, M.I. Bupropion is a nicotinic antagonist. J. Pharm. Exp. 2000, 295, 321–327. [Google Scholar]

- Benli, A.R.; Erturhan, S.; Oruc, M.A.; Kalpakci, P.; Sunay, D.; Demirel, Y. A comparison of the efficacy of varenicline and bupropion and an evaluation of the effect of the medications in the context of the smoking cessation programme. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2017, 15, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Talavera, K.; Gees, M.; Karashima, Y.; Meseguer, V.M.; Vanoirbeek, J.A.J.; Damann, N.; Everaerts, W.; Benoit, M.; Janssens, A.; Vennekens, R.; et al. Nicotine activates the chemosensory cation channel TRPA1. Nat. Neurosci. 2009, 12, 1293–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Feng, Z.; Li, W.; Ward, A.; Piggott, B.J.; Larkspur, E.R.; Sternberg, P.; Xu, X.S. A C. elegans Model of Nicotine-Dependent Behavior: Regulation by TRP-Family Channels. Cell 2006, 127, 621–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oliveira-Maia, A.J.; Stapleton-Kotloski, J.R.; Lyall, V.; Phan, T.-H.T.; Mummalaneni, S.; Melone, P.; DeSimone, J.A.; Nicolelis, M.A.L.; Simon, S.A. Nicotine activates TRPM5-dependent and independent taste pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 1596–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Willis, D.N.; Liu, B.; Ha, M.A.; Jordt, S.; Morris, J.B. Menthol attenuates respiratory irritation responses to multiple cigarette smoke irritants. FASEB J. 2011, 25, 4434–4444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ha, M.A.; Smith, G.J.; Cichocki, J.A.; Fan, L.; Liu, Y.-S.; Caceres, A.I.; Jordt, S.E.; Morris, J.B. Menthol Attenuates Respiratory Irritation and Elevates Blood Cotinine in Cigarette Smoke Exposed Mice. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fan, L.; Balakrishna, S.; Jabba, S.V.; Bonner, P.; Taylor, S.R.; Picciotto, M.R.; Jordt, S.-E. Menthol decreases oral nicotine aversion in C57BL/6 mice through a TRPM8-dependent mechanism. Tob. Control. 2016, 25, ii50–ii54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.-Y.; Lin, Y.-J.; Lee, H.-F.; Ho, C.-Y.; Ruan, T.; Kou, Y.R. Menthol suppresses laryngeal C-fiber hypersensitivity to cigarette smoke in a rat model of gastroesophageal reflux disease: The role of TRPM8. J. Appl. Physiol. 2015, 118, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, A.-H.; Liu, M.-H.; Ko, H.-K.B.; Perng, D.-W.; Lee, T.-S.; Kou, Y.R. Inflammatory Effects of Menthol vs. Non-menthol Cigarette Smoke Extract on Human Lung Epithelial Cells: A Double-Hit on TRPM8 by Reactive Oxygen Species and Menthol. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, T.; Wang, B.; Chen, H. Menthol facilitates the intravenous self-administration of nicotine in rats. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Benowitz, N.L.; Herrera, B.; Jacob, P. Mentholated Cigarette Smoking Inhibits Nicotine Metabolism. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004, 310, 1208–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Teichert, R.W.; Memon, T.; Aman, J.W.; Olivera, B.M. Using constellation pharmacology to define comprehensively a somatosensory neuronal subclass. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 2319–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henderson, B.J.; Wall, T.R.; Henley, B.M.; Kim, C.H.; McKinney, S.; Lester, H.A. Menthol Enhances Nicotine Reward-Related Behavior by Potentiating Nicotine-Induced Changes in nAChR Function, nAChR Upregulation, and DA Neuron Excitability. Neuropsychopharmacology 2017, 42, 2285–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brody, A.L.; Mukhin, A.G.; La Charite, J.; Ta, K.; Farahi, J.; Sugar, C.A.; Mamoun, M.S.; Vellios, E.; Archie, M.; Kozman, M.; et al. Up-regulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in menthol cigarette smokers. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013, 16, 957–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cooper, S.Y.; Akers, A.T.; Henderson, B.J. Flavors Enhance Nicotine Vapor Self-administration in Male Mice. Nicotine. Tob. Res. 2021, 23, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, L.; Harrison, E.; Gong, Y.; Avusula, R.; Lee, J.; Zhang, M.; Rousselle, T.; Lage, J.; Liu, X. Enhancing effect of menthol on nicotine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology 2016, 233, 3417–3427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, M.; Harrison, E.; Biswas, L.; Tran, T.; Liu, X. Menthol facilitates dopamine-releasing effect of nicotine in rat nucleus accumbens. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2018, 175, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahijevych, K.; Garrett, B.E. The Role of Menthol in Cigarettes as a Reinforcer of Smoking Behavior. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2010, 12, S110–S116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Journigan, V.B.; Feng, Z.; Rahman, S.; Wang, Y.; Amin, A.R.M.R.; Heffner, C.E.; Bachtel, N.; Wang, S.; Gonzalez-Rodriguez, S.; Fernández-Carvajal, A.; et al. Structure-Based Design of Novel Biphenyl Amide Antagonists of Human Transient Receptor Potential Cation Channel Subfamily M Member 8 Channels with Potential Implications in the Treatment of Sensory Neuropathies. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2020, 11, 268–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, B.J.; Grant, S.; Chu, B.W.; Shahoei, R.; Huard, S.M.; Saladi, S.S.M.; Tajkhorshid, E.; Dougherty, D.A.; Lester, H.A. Menthol stereoisomers exhibit different effects on a4b2 nAChR upregulation and dopamine neuron spontaneous firing. eNeuro 2018, 5, e0465-18.2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Avelar, A.J.; Akers, A.T.; Baumgard, Z.J.; Cooper, S.Y.; Casinelli, G.P.; Henderson, B.J. Why flavored vape products may be attractive: Green apple tobacco flavor elicits reward-related behavior, upregulates nAChRs on VTA dopamine neurons, and alters midbrain dopamine and GABA neuron function. Neuropharmacology 2019, 158, 107729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, B.J.; Wall, T.; Henley, B.M.; Kim, C.H.; Nichols, W.A.; Moaddel, R.; Xiao, C.; Lester, H.A. Menthol alone upregulates midbrain nAChRs, alters nAChR sybtype stoichiometry, alters dopamine neuron firing frequency, and prevents nicotine reward. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 2957–2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapper, A.R.; McKinney, S.L.; Nashmi, R.; Schwarz, J.; Deshpande, P.; Labarca, C.; Whiteaker, P.; Marks, M.J.; Collins, A.C.; Lester, H.A. Nicotine activation of α4* receptors: Sufficient for reward, tolerance and sensitization. Science 2004, 306, 1029–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, B.; Srinivasan, R.; Nichols, W.A.; Dilworth, C.N.; Gutierrez, D.F.; Mackey, E.D.; McKinney, S.; Drenan, R.M.; Richards, C.I.; Lester, H.A. Nicotine exploits a COPI-mediated process for chaperone-mediated up-regulation of its receptors. J. Gen. Physiol. 2013, 143, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivasan, R.; Pantoja, R.; Moss, F.J.; Mackey, E.D.W.; Son, C.; Miwa, J.; Lester, H.A. Nicotine upregulates α4β2 nicotinic receptors and ER exit sites via stoichiometry-dependent chaperoning. J. Gen. Physiol. 2011, 137, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Richards, C.I.; Srinivasan, R.; Xiao, C.; Mackey, E.D.; Miwa, J.M.; Lester, H.A. Trafficking of α4* nicotinic receptors revealed by superecliptic phluorin: Effects of a β4 amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-associated mutation and chronic exposure to nicotine. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 31241–31249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nelson, M.E.; Kuryatov, A.; Choi, C.H.; Zhou, Y.; Lindstrom, J. Alternate stoichiometries of a4b2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Mol. Pharm. 2003, 63, 332–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- González-Cestari, T.F.; Henderson, B.J.; Pavlovicz, R.E.; McKay, S.B.; El-Hajj, R.A.; Pulipaka, A.B.; Orac, C.M.; Reed, D.D.; Boyd, R.T.; Zhu, M.X.; et al. Effect of Novel Negative Allosteric Modulators of Neuronal Nicotinic Receptors on Cells Expressing Native and Recombinant Nicotinic Receptors: Implications for Drug Discovery. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008, 328, 504–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hans, M.; Wilhelm, M.; Swandulla, D. Menthol Suppresses Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Functioning in Sensory Neurons via Allosteric Modulation. Chem. Senses 2012, 37, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, C.K.; Byun, N.; Bubser, M. Muscarinic and nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonists and allosteric modulators for the treatment of schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 2012, 37, 16–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ngolab, J.; Liu, L.; Zhao-Shea, R.; Gao, G.; Gardner, P.D.; Tapper, A.R. Functional Upregulation of α4* Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors in VTA GABAergic Neurons Increases Sensitivity to Nicotine Reward. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 8570–8578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nashmi, R.; Xiao, C.; Deshpande, P.; McKinney, S.; Grady, S.R.; Whiteaker, P.; Huang, Q.; McClure-Begley, T.; Lindstrom, J.M.; Labarca, C.; et al. Chronic nicotine cell specifically upregulates functional α4* nicotinic receptors: Basis for both tolerance in midbrain and enhanced long-term potentiation in perforant path. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 8202–8218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grieder, T.E.; Besson, M.; Maal-Bared, G.; Pons, S.; Maskos, U.; van der Kooy, D. beta2* nAChRs on VTA dopamine and GABA neurons separately mediate nicotine aversion and reward. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 25968–25973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonio-Tolentino, K.; Hopkins, C.R. Selective α7 nicotinic receptor agonists and positive allosteric modulators for the treatment of schizophrenia—a review. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2020, 29, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermann, D.B.; Sandager-Nielsen, K.; Dyhring, T.; Smith, M.; Jacobsen, A.-M.; Nielsen, E.Ø.; Grunnet, M.; Christensen, J.K.; Peters, D.; Kohlhaas, K.; et al. Augmentation of cognitive function by NS9283, a stoichiometry-dependent positive allosteric modulator of α2- and α4-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 167, 164–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ton, H.T.; Smart, A.E.; Aguilar, B.L.; Olson, T.T.; Kellar, K.J.; Ahern, G.P. Menthol Enhances the Desensitization of Human alpha3beta4 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. Mol. Pharm. 2015, 88, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashoor, A.; Nordman, J.; Veltri, D.; Yang, K.-H.S.; Al Kury, L.; Shuba, Y.; Mahgoub, M.; Howarth, F.C.; Sadek, B.; Shehu, A.; et al. Menthol Binding and Inhibition of α7-Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ashoor, A.; Nordman, J.; Veltri, D.; Yang, K.-H.S.; Shuba, Y.; Al Kury, L.; Sadek, B.; Howarth, F.C.; Shehu, A.; Kabbani, N.; et al. Menthol Inhibits 5-HT3 Receptor–Mediated Currents. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2013, 347, 398–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Corvalan, N.A.; Zygadlo, J.A.; Garcia, D.A. Stereo-selective activity of menthol on GABA(A) receptor. Chirality 2009, 21, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.C.; Turcotte, C.M.; Betts, B.A.; Yeung, W.-Y.; Agyeman, A.S.; Burk, L.A. Modulation of human GABAA and glycine receptor currents by menthol and related monoterpenoids. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2004, 506, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanjakdar, S.S.; Maldoon, P.P.; Marks, M.J.; Brunzell, D.H.; Maskos, U.; McIntosh, J.M.; Bowers, M.S.; Damaj, M.I. Differential roles of a6b2* and a4b2* neuronal nicotinic receptors in nicotine- and cocaine-conditioned reward in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology 2015, 40, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yi, B.; Long, S.; González-Cestari, T.F.; Henderson, B.J.; Pavlovicz, R.E.; Werbovetz, K.; Li, C.; McKay, D.B. Discovery of benzamide analogs as negative allosteric modulators of human neuronal nicotinic receptors: Pharmacophore modeling and structure-activity relationship studies. Bioorganic. Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 4730–4743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Henderson, B.J.; Gonzalez-Cestari, T.F.; Yi, B.; Pavlovicz, R.E.; Boyd, R.T.; Li, C.; Bergmeier, S.C.; McKay, D.B. Defining the putative inhibitory site for a selective negative allosteric modulator of human a4b2 neuronal nicotinic receptors. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2012, 3, 682–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Henderson, B.J.; Orac, C.M.; Maciagiewicz, I.; Bergmeier, S.C.; McKay, D.B. 3D-QSAR and 3D-QSSR models of negative allosteric modulators facilitate the design of a novel selective antagonist of human a4b2 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 1797–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).