Abstract

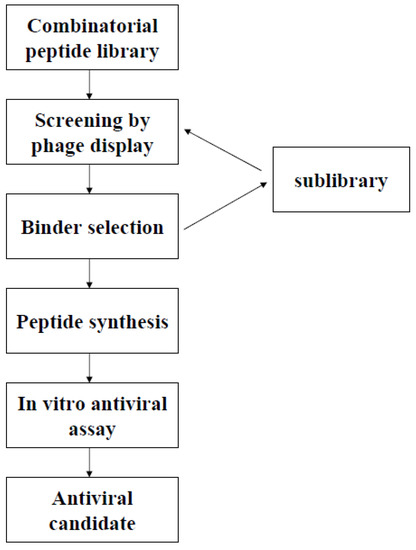

Given the growing number of diseases caused by emerging or endemic viruses, original strategies are urgently required: (1) for the identification of new drugs active against new viruses and (2) to deal with viral mutants in which resistance to existing antiviral molecules has been selected. In this context, antiviral peptides constitute a promising area for disease prevention and treatment. The identification and development of these inhibitory peptides require the high-throughput screening of combinatorial libraries. Phage-display is a powerful technique for selecting unique molecules with selective affinity for a specific target from highly diverse combinatorial libraries. In the last 15 years, the use of this technique for antiviral purposes and for the isolation of candidate inhibitory peptides in drug discovery has been explored. We present here a review of the use of phage display in antiviral research and drug discovery, with a discussion of optimized strategies combining the strong screening potential of this technique with complementary rational approaches for identification of the best target. By combining such approaches, it should be possible to maximize the selection of molecules with strong antiviral potential.

1. Introduction

Phage display technology was first used by George Smith in 1985 [1]. It took several years to appreciate the potential of this new tool, but the increasing number of publications relating to its use attests to the versatility of this technique for many applications, including epitope mapping, the isolation of high-affinity proteins, protein engineering and drug discovery. Phage display is based on the expression of the molecules of interest (peptides or proteins) as a fusion with the amino- or carboxy-terminus of a protein present on the surface of the bacteriophage [1,2]. This makes it possible to expose combinatorial protein/peptide libraries on the surface of recombinant phages. The exposed proteins/peptides are then selected by an affinity selection procedure, based on their ability to bind a specific target, such as an antibody, an enzyme, a purified receptor, a nucleic acid or other non protein molecule [2]. The selection process consists of several iterative cycles, each comprising capture, washing and elution steps, for progressive enrichment and amplification of the phage population carrying molecules with a higher affinity for the target. These molecules are then tested individually, to assess their activity or ability to perform the desired function. We focus here on the use of phage display to search for new antiviral compounds in highly diverse peptide libraries. Antibody libraries, another popular application of phage display for the selection of antibodies with high affinity/specificity, is not discussed here.

Antiviral research is an active domain of research, as there are too few molecules available for fighting viral infections and there may even be no available treatment for many neglected viral diseases. There is an urgent need to extend our antiviral arsenal, both to control diseases caused by emerging or endemic viruses and to overcome resistant mutants selected by treatment with the available antiviral molecules. Novel strategies and high-throughput technologies are required to address this need for new drug discovery.

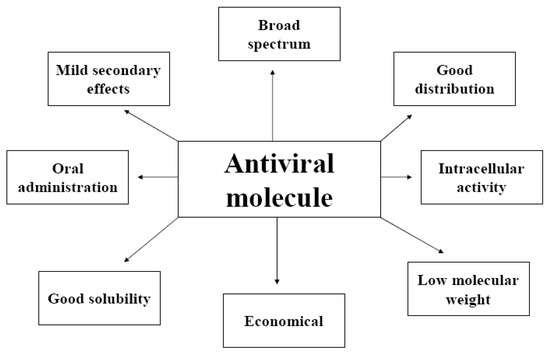

Antiviral molecules must satisfy the same conditions as any therapeutic substance (ADME properties: absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion): low molecular weight, good solubility, rapid elimination of the target organism, few secondary effects, simple and inexpensive production and easy administration [3] (Figure 1). Moreover, all antiviral molecules targeting the intracellular steps of the viral cycle must be able to enter cells, to express their inhibitory potential [4].

Figure 1.

Principal characteristics of a perfect antiviral molecule.

In parallel to the development of traditional molecules, such as nucleoside analogs, with well demonstrated efficacy, the pharmaceutical industry is now exploring new avenues, such as antiviral peptides. These peptides may prevent viral attachment to host cell receptors or inhibit the replication complex by interfering with protein-protein interactions, dissociating the complex and/or inhibiting its formation [4,5,6,7,8].

Two main approaches can be used to identify such peptides:

- A cognitive approach based on knowledge about the structure/function of the viral components and the interactions they establish within the complex and, possibly, with cellular partners.

- A random approach involving the high-throughput screening of highly diverse combinatorial molecule libraries generated by natural or organic chemistry (nucleic acids, peptides, proteins). This approach is particularly useful for the rapid isolation of candidate antiviral molecules [9] in cases in which little is known about the target protein, ruling out the use of more rational techniques [7].

Peptides have several advantages over traditional chemical compounds, but also a number of disadvantages. On the positive side, they are highly specific and effective, because they mimic the smallest possible part of a functional protein. They also have other very interesting therapeutic characteristics, such as high biodegradability by peptidases present in the body, limiting their accumulation in tissues and resulting in lower toxicity, because their degradation products are amino acids [3]. The potential drawbacks of peptide use are a limited ability to cross membrane barriers, a short half-life (rapid blood clearance) and potential immunogenicity [10], complex modes of action, high production costs and poor oral absorption, often necessitating intravenous administration [3,11]. Nevertheless, it is possible to overcome these limitations [3] through the use of new technologies modifying these molecules and their delivery, stability and application in preclinical settings [12]. For example, D-peptides are resistant to natural proteases (unlike L-peptides), have a longer half-life in serum, can be effectively absorbed orally [8] and are recommended for therapeutic use [13].

3. The Choice of the Target Protein: A Critical Decision

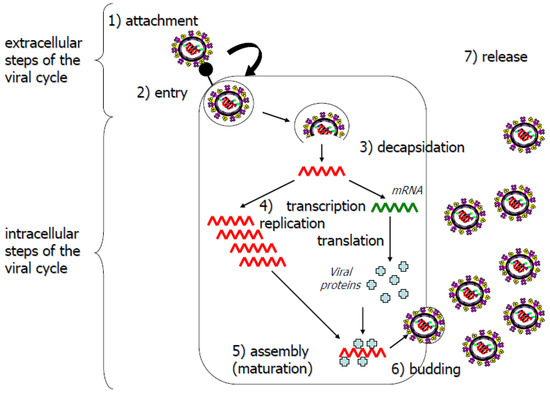

Antiviral molecules should target key steps of the viral life cycle. These steps can be defined, in particular, by studying the structure-function relationships of viral proteins and their cellular partners. All infection steps (Figure 3) can potentially be targeted for the development of antiviral agents: penetration, release of the viral capsid or genome into the cell, transcription/replication, translation, assembly or the release of progeny virus [45]. Molecules targeting internal steps of the viral cycle are confronted by an additional challenge: entering the cell to exert their inhibitory effects. Cellular proteins essential for the viral replication cycle are also potential targets. The designers of antiviral agents tend to prefer agents with the broadest spectrum of antiviral efficiency, for reasons of both efficiency and economy [26,46]. Treatments should therefore preferentially target proteins involved in generic steps of the viral cycle [47].

The phage display of combinatorial peptide libraries has already been used successfully several times over the last 15 years, in the discovery of inhibitory peptides active against viruses (Table 1). The first viruses to be targeted were hepatitis B virus (HBV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and both these two viruses remain the most frequently targeted, but other viruses from different families were also considered. Diverse strategies and targets have been used, providing an incidental demonstration of the versatility of the method. Two main approaches are used:

- (1). Targeting of the viral proteins responsible for virus entry into cells (extracellular steps)

- (2). Targeting of the various elements of the viral replication complex and the cellular partners of viral proteins within infected cells (intracellular steps).

Table 1.

Examples of antiviral peptides selected by phage display of combinatorial peptide libraries.

| Viral replication step | Virus | Target | Library | Year | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extracellular steps | IBV | whole virus | 12-mer | 2006 | [48] |

| CMV | whole virus | 9-mer | 1999 | [49] | |

| Human rotavirus | whole virus | 15-mer | 2007 | [50] | |

| WSSV | whole virus | 10-mer | 2003 | [51] | |

| NDV | whole virus | Cyclic 7-mer | 2002 | [52,53] | |

| NDV | whole virus | 7-mer | 2005 | [54] | |

| GCHV | whole virus | 9-mer | 2000 | [55] | |

| ANDV | whole virus | 9-mer | 2009 | [34] | |

| AIV (H9N2) | whole virus | 7-mer | 2009 | [35,56] | |

| West-Nile | protein E | Mouse brain cDNA | 2007 | [57] | |

| HCV | protein E2 | 7-mer | 2010 | [59] | |

| HBV | protein domain PreS | 12-mer | 2007 | [58] | |

| HIV-1 | protein gp41 | 10-mer | 1999 | [37] | |

| HIV-1 | protein gp41 | 8-mer / 7-mer | 2007 | [8] | |

| HIV-1 | protein gp41 | 8-mer / 7-mer | 2010 | [13] | |

| Influenza A | protein HA | 15-mer | 2010 | [14] | |

| SNV, HTNV, PHV | integrin alpha/beta | cyclic 9-mer | 2005 | [73] | |

| Intracellular steps | HBV | protein HBcAg | 6-mer | 1995 | [60] |

| HBV | protein HBcAg | C-7-mer-C | 2003 | [20] | |

| HBV | protein HBsAg | C-7-mer-C | 2005 | [62] | |

| HIV | integrase | 7-mer | 2004 | [65] | |

| HIV | protein GAG | 12-mer | 2005 | [66] | |

| HIV | protein Tat | fd pVIII fragments | 2005 | [69] | |

| HIV | protein LcK | 12-mer | 2005 | [71] | |

| HCV | polymerase NS5B | C-7-mer-C | 2003 | [63] | |

| HCV | polymerase NS5B | 7-mer/12-mer/C-9-mer-C | 2008 | [64] | |

| HPV16 | protein E2 | 7-mer / 12-mer | 2003 | [36] | |

| VSV | IFN receptor | 7-mer | 2008 | [75] | |

| HCV | interleukin 10 | 15-mer | 2011 | [76] |

Figure 3.

Simplified diagram of the viral life cycle. Extracellular (1, 2 and 7) and intracellular (3, 4, 5 and 6) steps are indicated.

3.3. Targeting cellular proteins

Targeting a cellular protein playing a role in viral infection or in the antiviral immune response is a particularly appropriate approach for viruses with a high mutation frequency capable of developing resistance against drugs targeting their own proteins.

Again, much of the pioneering research in this domain was carried out on HIV, with the demonstration that a peptide isolated for its affinity for the SH3 domain of the cellular kinase Lck acts as a competitive inhibitor of the HIV Nef protein [71], opening up new perspectives for the development of anti-HIV molecules [72]. However, the use of cellular targets has the particular advantage of providing a potential response to several different viruses. For example, αvβ3 integrin, which is responsible for the entry of hantaviruses into cells, has been used for the screening of a combinatorial cyclic 9-mer peptide library by phage display [73]. Seventy peptides were found to be effective competitors for this receptor and eight of these peptides had a sequence similar to a region of the viral glycoprotein. Some of the selected peptides were able to inhibit infection by Sin Nombre virus (SNV) in a focus reduction assay. In tests assessing the ability of these peptides to inhibit infection by other hantaviruses, the most promising peptides inhibited Hantaan virus (HTNV) infection more effectively than Prospect Hill virus (PHV), which uses a different receptor to enter cells. This strongly suggests that peptides act by competing with the viral glycoprotein for binding to the integrin receptor. The best four peptides, when chemically synthesized independently of the phage, retained their ability to inhibit the entry of SNV into cells, this effect being the most marked when they were used in combination [18].

Another strategy involves enhancing or complementing the immune response, particularly for viruses that naturally counteract innate immunity. Attempts have been made to identify compounds enhancing the immune response and capacity to resist microbial infection [74]. For example, screening of a peptide library against the IFN receptor led to the selection of two candidate peptides mimicking IFN-α antiviral activity against vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) [75]. Interferon-α can also be stimulated indirectly, by targeting its inhibitors. A 15-mer peptide library has been screened against interleukin 10 (IL-10), a cytokine induced by the HCV core protein and involved in the poor cellular immune response against this virus. Two peptides inhibiting IL-10 were shown to restore the ability of dendritic cells to produce INF-α and to strengthen the anti-HCV T-cell response [76]. This approach is similar to the use of siRNA to target Hsp70, which is overproduced during dengue infection and favors virus multiplication by suppressing type 1 IFN production [77]. Consequently, Hsp70 is a potentially promising cellular target for a phage display strategies aiming to identify peptides active against dengue for use in treatment.

4. Conclusions

Phage display is an efficient technology for selecting peptides with a high affinity for the target, but it is not always possible to obtain candidates with strong antiviral potential by this approach. However, selected peptides can subsequently be improved by rational approaches (drug design, modified residues, mutagenesis, etc.) [24]. In addition, phage display techniques facilitate the emergence of motifs common to selected peptides that can be used to fix positions in a secondary library, thereby retaining the best features of the selected peptides and allowing a gradual improvement in their affinity through successive selections [12].

We have described here success stories resulting in promising antiviral peptide candidates and demonstrating the potential of phage display for use in drug discovery. However, several similar studies have failed to select candidates with sufficient antiviral effects, even when the peptides were selected for their high affinity for the target used. On the one hand, it is not uncommon for molecules displaying significant binding when displayed on the phage surface to lose this capacity and their antiviral effect when synthesized without the carrier and tested in vitro/in vivo. On the other hand, a high capacity to bind the target is not necessarily associated with an antiviral effect, particularly when the binding domain is located outside the active site of the target.

A reverse strategy may therefore constitute a viable alternative approach for increasing the inhibitory potential of molecules. This would involve the initial development of functional screens [78,79], with phage display techniques then used to improve the affinity of the peptides displaying some ability to inhibit the function targeted. This rational approach would help to guide and to limit the degree of “freedom” of peptide libraries, with the phage display combinatorial approach contributing a greater diversity than would be possible with a purely rational approach [25]. The choice of amino acids constituting the candidate peptide can be left random, to provide flexibility and optimize affinity for the target [25]. Directed evolution by phage display has already been used to improve the catalytic properties of enzymes [80,81,82] and to isolate peptides mimicking interferon with stronger biological properties than the wild-type molecule [83,84]. Similarly, the characteristics of the antiviral drug palivizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody used to treat respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection, have been improved by an iterative approach of mutagenesis associated with phage display [85], a method that has also proved effective for an antiviral candidate peptide [61]. Thus, although the considerable potential for the use of phage display in antiviral research is well established, it remains clear how best to use it and how (and when) to integrate it into a broader process including rational, functional and structural studies of the interactions within viral complexes and with cellular partners [24].

With a view to the development of therapeutic applications, it is important to take into account, very early in the selection strategy, all the essential parameters for the design of the molecule, which must ultimately be active in animals or humans: transmembrane penetration, metabolic stability, tissue distribution and elimination, etc. These data should ideally be integrated into the original library. For example, a few small peptide sequences, such as those of penetratin, Tat or VP22, are useful for promoting passage across the membrane and the specific delivery of the peptide to a cell or organ [12]. The generation of peptide libraries fused to a transmembrane signal peptide, such as the HIV Tat peptide, would make it possible to select peptides with a conformation similar to that they are likely to adopt during cell delivery. This would prevent the selection of peptides with characteristics that change during their transformation into therapeutic molecules. In any case, the use of short sequences is commercially advantageous, as it can greatly reduce the cost of production. Identification of the minimal antiviral sequence is therefore of great importance [14].

Good specificity for the target is a general requirement of the candidate peptides. However, when different strains of a virus or different viruses are targeted, extreme specificity may limit the spectrum of activity of the peptide in clinical use [14]. In this case, it is preferable to develop antiviral drugs with a broad spectrum of inhibitory activity. The choice of targets with a structure and/or function common to different viruses is the first step in the antiviral strategy [14]. Screening the library against a protein target conserved among viruses, or successive screenings of the same library against targets of similar function from different viruses could lead to the emergence of molecules with broad-spectrum potential. This approach can be completed by a functional approach involving the testing of molecules with antiviral effects against one virus against related viruses from the same family [57].

For a broad-spectrum approach, proteins involved in virus attachment and penetration are obvious potential targets, but elements of the viral transcription/replication complex and their cellular partners are frequently more strongly conserved and should not be ignored. As mentioned above, one target of choice is the replication ribonucleoprotein complex (RNP) of NSRV, which has a similar structure in unsegmented (Rhabdoviridae, Paramyxoviridae and Filoviridae families) and segmented (Orthomyxoviridae and Bunyaviridae families) viruses, and which typically operates independently of cellular polymerases. In addition, there is no obvious counterpart of this replication complex in humans, suggesting a low likelihood of side effects if used for treatment. Typically, the use of broad-spectrum molecules is the only way to compensate for the low economic attractiveness of neglected diseases to the pharmaceutical industry. Phage display, which has been preferentially applied to diseases with high economic potential, such as HIV or hepatitis, is a unique tool combining original strategies with an exceptional screening potential. It should be applied to neglected diseases against which no antiviral molecule is currently available.

Acknowledgments

Guillaume Castel held a fellowship from Institut Pasteur. Mohamed Chteoui held a fellowship of Fondation Mérieux, 17, rue Bourgelat, Lyon. Bernadette Heyd held a postdoctoral fellowship supported by the ANR project ANRAGE: “Structural Dynamics of the Rabies Virus Replication Complex: Search for New Antiviral Targets” (domain “Microbiology - Immunology - Emerging Diseases”).

References and Notes

- Smith, G.P. Filamentous fusion phage: Novel expression vectors that display cloned antigens on the virion surface. Science 1985, 228, 1315–1317. [Google Scholar]

- Souriau, C.; Hua, T.; Lefranc, M.; Weill, M. Présentation à la surface de phages filamenteux: Les multiples applications du phage display. Médecine/Sciences 1998, 14, 300–309. [Google Scholar]

- Decaffmeyer, M.; Thomas, A.; Brasseur, R. Les médicaments peptidiques: Mythe ou réalité ? Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. 2008, 12, 2057. [Google Scholar]

- Brissette, R.; Goldstein, N.I. The use of phage display peptide libraries for basic and translational research. Methods Mol. Biol. 2007, 383, 203–213. [Google Scholar]

- Loregian, A.; Palu, G. Disruption of the interactions between the subunits of herpesvirus DNA polymerases as a novel antiviral strategy. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2005, 11, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loregian, A.; Palu, G. Disruption of protein-protein interactions: Towards new targets for chemotherapy. J. Cell Physiol. 2005, 204, 750–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicent, M.J.; Perez-Paya, E.; Orzaez, M. Discovery of inhibitors of protein-protein interactions from combinatorial libraries. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2007, 7, 83–95. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, B.D.; VanDemark, A.P.; Heroux, A.; Hill, C.P.; Kay, M.S. Potent D-peptide inhibitors of HIV-1 entry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 16828–16833. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal, M.; Endoh, H. Prospects for drug screening using the reverse two-hybrid system. Trends Biotechnol. 1999, 17, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.; Yao, C.; Wang, L.; Min, W.; Xu, J.; Xiao, J.; Huang, M.; Chen, B.; Liu, B.; Li, X.; Jiang, H. An albumin-conjugated peptide exhibits potent anti-HIV activity and long in vivo half-life. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, C.M.; Cohen, M.A.; Bloom, S.R. Peptides as drugs. QJM 1999, 92, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladner, R.C.; Sato, A.K.; Gorzelany, J.; de Souza, M. Phage display-derived peptides as therapeutic alternatives to antibodies. Drug Discov. Today 2004, 9, 525–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, B.D.; Francis, J.N.; Redman, J.S.; Paul, S.; Weinstock, M.T.; Reeves, J.D.; Lie, Y.S.; Whitby, F.G.; Eckert, D.M.; Hill, C.P.; Root, M.J.; Kay, M.S. Design of a potent D-peptide HIV-1 entry inhibitor with a strong barrier to resistance. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 11235–11244. [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara, T.; Onishi, A.; Saito, T.; Shimada, A.; Inoue, H.; Taki, T.; Nagata, K.; Okahata, Y.; Sato, T. Sialic acid-mimic peptides as hemagglutinin inhibitors for anti-influenza therapy. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 4441–4449. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, G.P.; Petrenko, V.A. Phage display. Chem. Rev. 1997, 97, 391–410. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, J.R.; Deutscher, S.L. In vivo bacteriophage display for the discovery of novel peptide-based tumor-targeting agents. Methods Mol. Biol. 2009, 504, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.J.; Panganiban, L.C.; Devlin, P.E. Random peptide libraries: A source of specific protein binding molecules. Science 1990, 249, 404–406. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, P.R.; Hjelle, B.; Brown, D.C.; Ye, C.; Bondu-Hawkins, V.; Kilpatrick, K.A.; Larson, R.S. Multivalent presentation of antihantavirus peptides on nanoparticles enhances infection blockade. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 2079–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowman, H.B. Bacteriophage display and discovery of peptide leads for drug development. Annu Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 1997, 26, 401–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, K.L.; Yusoff, K.; Seow, H.F.; Tan, W.S. Selection of high affinity ligands to hepatitis B core antigen from a phage-displayed cyclic peptide library. J. Med. Virol. 2003, 69, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladner, R.C. Constrained peptides as binding entities. Trends Biotechnol. 1995, 13, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Privalov, P.L.; Gill, S.J. Stability of protein structure and hydrophobic interaction. Adv. Protein Chem. 1988, 39, 191–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergeeva, A.; Kolonin, M.G.; Molldrem, J.J.; Pasqualini, R.; Arap, W. Display technologies: Application for the discovery of drug and gene delivery agents. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2006, 58, 1622–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pande, J.; Szewczyk, M.M.; Grover, A.K. Phage display: Concept, innovations, applications and future. Biotechnol. Adv. 2010, 28, 849–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falciani, C.; Lozzi, L.; Pini, A.; Bracci, L. Bioactive peptides from libraries. Chem. Biol. 2005, 12, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.K.; Smith, G.P. Searching for peptide ligands with an epitope library. Science 1990, 249, 386–390. [Google Scholar]

- Krumpe, L.R.; Atkinson, A.J.; Smythers, G.W.; Kandel, A.; Schumacher, K.M.; McMahon, J.B.; Makowski, L.; Mori, T. T7 lytic phage-displayed peptide libraries exhibit less sequence bias than M13 filamentous phage-displayed peptide libraries. Proteomics 2006, 6, 4210–4222. [Google Scholar]

- Castagnoli, L.; Zucconi, A.; Quondam, M.; Rossi, M.; Vaccaro, P.; Panni, S.; Paoluzi, S.; Santonico, E.; Dente, L.; Cesareni, G. Alternative bacteriophage display systems. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2001, 4, 121–133. [Google Scholar]

- Burritt, J.B.; Bond, C.W.; Doss, K.W.; Jesaitis, A.J. Filamentous phage display of oligopeptide libraries. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 238, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, A.M.; Weiss, G.A. Optimizing the affinity and specificity of proteins with molecular display. Mol. Biosyst. 2006, 2, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, S.S. Engineering M13 for phage display. Biomol. Eng. 2001, 18, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Connell, D.; Becerril, B.; Roy-Burman, A.; Daws, M.; Marks, J.D. Phage versus phagemid libraries for generation of human monoclonal antibodies. J. Mol. Biol. 2002, 321, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jestin, J.L. Functional cloning by phage display. Biochimie 2008, 90, 1273–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P.R.; Hjelle, B.; Njus, H.; Ye, C.; Bondu-Hawkins, V.; Brown, D.C.; Kilpatrick, K.A.; Larson, R.S. Phage display selection of cyclic peptides that inhibit Andes virus infection. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 8965–8969. [Google Scholar]

- Rajik, M.; Jahanshiri, F.; Omar, A.R.; Ideris, A.; Hassan, S.S.; Yusoff, K. Identification and characterisation of a novel anti-viral peptide against avian influenza virus H9N2. Virol. J. 2009, 6, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, T.; Austin, D.; Guo, D.; Srimatkandada, S.; Wang, T.; Kubushiro, K.; Masumoto, N.; Tsukazaki, K.; Nozawa, S.; Deisseroth, A.B. Peptides inhibitory for the transcriptional regulatory function of human papillomavirus E2. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003, 9, 5423–5428. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert, D.M.; Malashkevich, V.N.; Hong, L.H.; Carr, P.A.; Kim, P.S. Inhibiting HIV-1 entry: Discovery of D-peptide inhibitors that target the gp41 coiled-coil pocket. Cell 1999, 99, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyd, B.; Pecorari, F.; Collinet, B.; Adjadj, E.; Desmadril, M.; Minard, P. In vitro evolution of the binding specificity of neocarzinostatin, an enediyne-binding chromoprotein. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 5674–5683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knobel, D.L.; Cleaveland, S.; Coleman, P.G.; Fevre, E.M.; Meltzer, M.I.; Miranda, M.E.; Shaw, A.; Zinsstag, J.; Meslin, F.X. Re-evaluating the burden of rabies in Africa and Asia. Bull World Health Organ. 2005, 83, 360–368. [Google Scholar]

- Massé, N.; Selisko, B.; Malet, H.; Peyrane, F.; Debarnot, C.; Decroly, E.; Benarroch, D.; Egloff, M.; Guillemot, J.; Alvarez, K.; Canard, B. Le virus de la dengue: Cibles virales et antiviraux. Virologie 2007, 11, 121–133. [Google Scholar]

- Rodi, D.J.; Soares, A.S.; Makowski, L. Quantitative assessment of peptide sequence diversity in M13 combinatorial peptide phage display libraries. J. Mol. Biol. 2002, 322, 1039–1052. [Google Scholar]

- Malone, J.; Sullivan, M.A. Analysis of antibody selection by phage display utilizing anti-phenobarbital antibodies. J. Mol. Recognit. 1996, 9, 738–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schier, R.; Marks, J.D. Efficient in vitro affinity maturation of phage antibodies using BIAcore guided selections. Hum. Antibodies Hybridomas 1996, 7, 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Adey, N.B.; Mataragnon, A.H.; Rider, J.E.; Carter, J.M.; Kay, B.K. Characterization of phage that bind plastic from phage-displayed random peptide libraries. Gene 1995, 156, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyssen, P.; De Clercq, E.; Neyts, J. Molecular strategies to inhibit the replication of RNA viruses. Antiviral Res. 2008, 78, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aman, M.J.; Kinch, M.S.; Warfield, K.; Warren, T.; Yunus, A.; Enterlein, S.; Stavale, E.; Wang, P.; Chang, S.; Tang, Q.; Porter, K.; Goldblatt, M.; Bavari, S. Development of a broad-spectrum antiviral with activity against Ebola virus. Antiviral Res. 2009, 83, 245–251. [Google Scholar]

- Bray, M. Highly pathogenic RNA viral infections: Challenges for antiviral research. Antiviral Res. 2008, 78, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Chen, H.; Tan, Y.; Jin, M.; Guo, A. Identification of one peptide which inhibited infectivity of avian infectious bronchitis virus in vitro. Sci. Chin. C Life Sci. 2006, 49, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, K.C.; Cockburn, W.; Whitelam, G.C. Selection of phage-display peptides that bind to cucumber mosaic virus coat protein. J. Virol. Methods 1999, 79, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, N.; Yao, L.G.; Zhang, X.M.; Guo, T.L.; Kan, Y.C. Screening for peptides of anti-rotavirus by phage-displayed technique. Sheng Wu Gong Cheng Xue Bao 2007, 23, 403–408. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, G.; Qian, J.; Wang, Z.; Qi, Y. A phage-displayed peptide can inhibit infection by white spot syndrome virus of shrimp. J. Gen. Virol. 2003, 84, 2545–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanujam, P.; Tan, W.S.; Nathan, S.; Yusoff, K. Novel peptides that inhibit the propagation of Newcastle disease virus. Arch. Virol. 2002, 147, 981–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, S.L.; Tan, W.S.; Shaari, K.; Abdul Rahman, N.; Yusoff, K.; Satyanarayanajois, S.D. Structural analysis of peptides that interact with Newcastle disease virus. Peptides 2006, 27, 1217–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, M.; Ohashi, K.; Onuma, M. Identification and characterization of peptides binding to newcastle disease virus by phage display. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2005, 67, 1237–1241. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Ke, L.H.; Jiang, H.; Li, C.Z.; Tien, P. Selection of a specific peptide from a nona-peptide library for in vitro inhibition of grass carp hemorrhage virus replication. Virus Res. 2000, 67, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajik, M.; Omar, A.R.; Ideris, A.; Hassan, S.S.; Yusoff, K. A novel peptide inhibits the influenza virus replication by preventing the viral attachment to the host cells. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2009, 5, 543–548. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, F.; Town, T.; Pradhan, D.; Cox, J.; Ashish; Ledizet, M.; Anderson, J.F.; Flavell, R.A.; Krueger, J.K.; Koski, R.A.; Fikrig, E. Antiviral peptides targeting the west nile virus envelope protein. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 2047–2055. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Q.; Zhai, J.W.; Michel, M.L.; Zhang, J.; Qin, J.; Kong, Y.Y.; Zhang, X.X.; Budkowska, A.; Tiollais, P.; Wang, Y.; Xie, Y.H. Identification and characterization of peptides that interact with hepatitis B virus via the putative receptor binding site. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 4244–4254. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, H.W.; Lee, S.W.; Myung, H. Selection of peptides binding to HCV e2 and inhibiting viral infectivity. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 20, 1769–1771. [Google Scholar]

- Dyson, M.R.; Murray, K. Selection of peptide inhibitors of interactions involved in complex protein assemblies: Association of the core and surface antigens of hepatitis B virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 2194–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottcher, B.; Tsuji, N.; Takahashi, H.; Dyson, M.R.; Zhao, S.; Crowther, R.A.; Murray, K. Peptides that block hepatitis B virus assembly: Analysis by cryomicroscopy, mutagenesis and transfection. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 6839–6845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.S.; Tan, G.H.; Yusoff, K.; Seow, H.F. A phage-displayed cyclic peptide that interacts tightly with the immunodominant region of hepatitis B surface antigen. J. Clin. Virol. 2005, 34, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A.; Zaccardi, J.; Mullen, S.; Olland, S.; Orlowski, M.; Feld, B.; Labonte, P.; Mak, P. Identification of constrained peptides that bind to and preferentially inhibit the activity of the hepatitis C viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Virology 2003, 313, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Park, C.; Lee, J.H.; Myung, H. Selection and target-site mapping of peptides inhibiting HCV NS5B polymerase using phage display. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 18, 328–333. [Google Scholar]

- Desjobert, C.; de Soultrait, V.R.; Faure, A.; Parissi, V.; Litvak, S.; Tarrago-Litvak, L.; Fournier, M. Identification by phage display selection of a short peptide able to inhibit only the strand transfer reaction catalyzed by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 13097–13105. [Google Scholar]

- Sticht, J.; Humbert, M.; Findlow, S.; Bodem, J.; Muller, B.; Dietrich, U.; Werner, J.; Krausslich, H.G. A peptide inhibitor of HIV-1 assembly in vitro. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005, 12, 671–677. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz, J.; Koch, J.; Kaur, A.; Raja, C.; Stein, S.; Grez, M.; Pustowka, A.; Mensch, S.; Ferner, J.; Moller, L.; Bannert, N.; Tampe, R.; Divita, G.; Mely, Y.; Schwalbe, H.; Dietrich, U. Inhibition of HIV-1 by a peptide ligand of the genomic RNA packaging signal Psi. Chem. Med. Chem. 2008, 3, 749–755. [Google Scholar]

- Enshell-Seijffers, D.; Smelyanski, L.; Gershoni, J.M. The rational design of a 'type 88' genetically stable peptide display vector in the filamentous bacteriophage fd. Nucl. Acids Res. 2001, 29, E50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krichevsky, A.; Rusnati, M.; Bugatti, A.; Waigmann, E.; Shohat, S.; Loyter, A. The fd phage and a peptide derived from its p8 coat protein interact with the HIV-1 Tat-NLS and inhibit its biological functions. Antiviral Res. 2005, 66, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, G.J.; Talan, D.A.; Abrahamian, F.M. Biological terrorism. Infect Dis. Clin. North Am. 2008, 22, 145–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.; Hoffmann, S.; Wiesehan, K.; Jonas, E.; Luge, C.; Aladag, A.; Willbold, D. Insights into human Lck SH3 domain binding specificity: Different binding modes of artificial and native ligands. Biochemistry 2005, 44, 15042–15052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stangler, T.; Tran, T.; Hoffmann, S.; Schmidt, H.; Jonas, E.; Willbold, D. Competitive displacement of full-length HIV-1 Nef from the Hck SH3 domain by a high-affinity artificial peptide. Biol. Chem. 2007, 388, 611–615. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, R.S.; Brown, D.C.; Ye, C.; Hjelle, B. Peptide antagonists that inhibit Sin Nombre virus and hantaan virus entry through the beta3-integrin receptor. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 7319–7326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzianabos, A.O. Polysaccharide immunomodulators as therapeutic agents: Structural aspects and biologic function. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2000, 13, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Bai, G.; Chen, J.Q.; Tian, W.; Cao, Y.; Pan, P.W.; Wang, C. Identification of antiviral mimetic peptides with interferon alpha-2b-like activity from a random peptide library using a novel functional biopanning method. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2008, 29, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Valdes, N.; Manterola, L.; Belsue, V.; Riezu-Boj, J.I.; Larrea, E.; Echeverria, I.; Llopiz, D.; Lopez-Sagaseta, J.; Lerat, H.; Pawlotsky, J.M.; Prieto, J.; Lasarte, J.J.; Borras-Cuesta, F.; Sarobe, P. Improved dendritic cell-based immunization against hepatitis C virus using peptide inhibitors of interleukin 10. Hepatology 2011, 53, 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Padwad, Y.S.; Mishra, K.P.; Jain, M.; Chanda, S.; Ganju, L. Dengue virus infection activates cellular chaperone Hsp70 in THP-1 cells: Downregulation of Hsp70 by siRNA revealed decreased viral replication. Viral. Immunol. 2010, 23, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunner, W.H.; Pallatroni, C.; Curtis, P.J. Selection of genetic inhibitors of rabies virus. Arch. Virol. 2004, 149, 1653–1662. [Google Scholar]

- Pelet, T.; Miazza, V.; Mottet, G.; Roux, L. High throughput screening assay for negative single stranded RNA virus polymerase inhibitors. J. Virol. Methods 2005, 128, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Strobel, H.; Ladant, D.; Jestin, J.L. In vitro selection for enzymatic activity: A model study using adenylate cyclase. J. Mol. Biol. 2003, 332, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Soumillion, P.; Jespers, L.; Bouchet, M.; Marchand-Brynaert, J.; Winter, G.; Fastrez, J. Selection of beta-lactamase on filamentous bacteriophage by catalytic activity. J. Mol. Biol. 1994, 237, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, H.; Holder, S.; Sutherlin, D.P.; Schwitter, U.; King, D.S.; Schultz, P.G. A method for directed evolution and functional cloning of enzymes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 10523–10528. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, K.; Taniai, M.; Torigoe, K.; Yamamoto, S.; Arai, N.; Suemoto, Y.; Yoshida, K.; Okura, T.; Mori, T.; Fujioka, N.; Tanimoto, T.; Miyata, M.; Ariyasu, H.; Ushio, C.; Fujii, M.; Ariyasu, T.; Ikeda, M.; Ohta, T.; Kurimoto, M.; Fukuda, S. Creation of interferon-alpha8 mutants with amino acid substitutions against interferon-alpha receptor-2 binding sites using phage display system and evaluation of their biologic properties. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2009, 29, 161–170. [Google Scholar]

- Kalie, E.; Jaitin, D.A.; Abramovich, R.; Schreiber, G. An interferon alpha2 mutant optimized by phage display for IFNAR1 binding confers specifically enhanced antitumor activities. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 11602–11611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Pfarr, D.S.; Tang, Y.; An, L.L.; Patel, N.K.; Watkins, J.D.; Huse, W.D.; Kiener, P.A.; Young, J.F. Ultra-potent antibodies against respiratory syncytial virus: Effects of binding kinetics and binding valence on viral neutralization. J. Mol. Biol. 2005, 350, 126–144. [Google Scholar]

- Sample Availability: Not available.

© 2011 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).