Abstract

All contemporary living cells are composed of a collection of self-assembled molecular elements that by themselves are non-living but through the creatibon of a network exhibit the emergent properties of self-maintenance, self-reproduction, and evolution. This short review deals with the on-going research that aims at either understanding how life emerged on the early Earth or creating artificial cells assembled from a collection of small chemicals. In particular, this article focuses on the work carried out to investigate how self-assembled compartments, such as amphiphile and lipid vesicles, contribute to the emergent properties as part of a greater system.

1. Introduction

The term “emergence” refers to phenomena in which the structures and behavior of multicomponent systems exceed those predicted from knowledge of the individual components. The first appearance of living systems on the early Earth can be understood as an emergent phenomenon, because protocells, the simpler progenitors of contemporary living cells, were composed of a self-assembled collection of molecules that by themselves were non-living. Yet, together, these assemblies must have exhibited properties of self-maintenance, self-reproduction, and evolution, the hallmarks of life.

Using protocells, emergence can be studied in model systems that display functions similar to, but simpler than those of living systems. Components of such a model have been long debated and recently a consensus has started to emerge: to be functional, a protocell would need to be composed of a compartment, a reaction network, and information components [1,2,3]. But the components can only lead to emergent properties if their inter-connections are realized. At the core of the protocell design and the resulting interactions between components, entropy plays a significant role in the driving forces that defines/shapes processes such as aggregation and folding of macromolecules, as well as molecular recognition between the components, for example by affecting fitness landscapes or encouraging the exclusion of hydrophobic moieties.

This mini-review will focus on the formation of compartment structures and their interaction with the environment and possible protocell components, while identifying possible emergent properties that can arise from these interactions. Structures can create a spatial organization of chemicals and therein their reactions (i.e. compartmentalize them). For example, some form of compartmentalization, i.e. spatial separation, is essential to life for simple processes, such as the formation of chemical gradients or the protection of biomolecules from degradation. It also is a prerequisite for the appearance for well-documented emergent properties such as the link between a phenotype out of a genotype [4,5], or the arrangements of metabolic networks in a vectorial fashion [6]. Today, these boundary structures are formed primarily of complex lipids, which are an evolutionary product of living systems. However, some much simpler chemical species exist that have analogous, if not identical, properties and/or functions.

The formation of boundary structures is the first prerequisite whether one tries to model chemical evolution surrounding the origin of a self-replicating network on the early Earth (Origin of Life) or build an artificial protocell (Artificial Life). The main difference between structures designed for either areas of interest lays in the chemical composition of the systems, which in the former case is determined by their prebiotic availability and the latter by the imagination and goals of the researchers. In the exploration of the Origin of Life, it is also necessary to consider the environment on Earth four billion years ago (a difficult proposition). In contrast, when designing the artificial systems, it is possible to assemble container structures that have specific properties, which are not necessarily biomimetic. Work in creating a complex chemical network with emergent properties is therefore represented over a large spectrum from attempting realism [7] to constructing a completely novel metabolism [8]. Most of the research described to date falls well in between these two extremes using a mixture of synthetic and biological molecules.

In this review, the formation of amphiphile based compartments by self-assembly and the resulting compartment properties will first be described especially in relation with environmental influences. Then the focus will shift to demonstrating how these compartments can influence the functions and interactions of the three protocell components leading to new, emergent properties.

2. Self-Assembly of Amphiphile Compartments

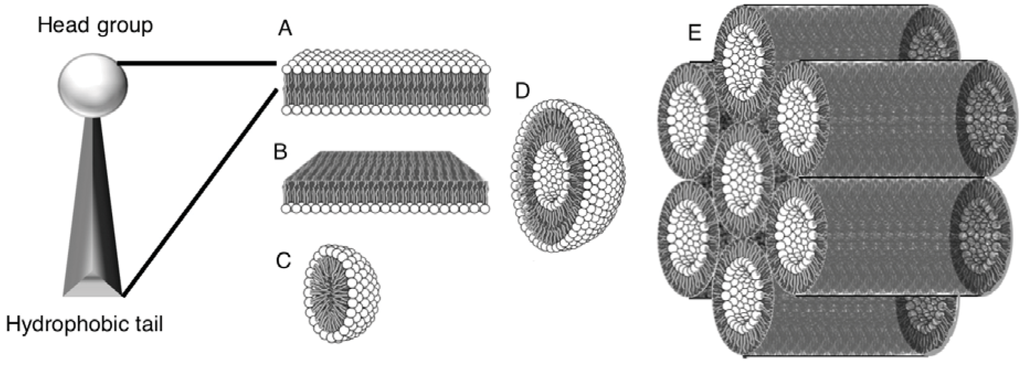

To discuss the emergent properties of these systems, it is helpful to fully understand the chemical properties of the structural building blocks. Amphiphiles have a unique interaction with water that causes structure formation and plays a large role in the interactions between the resulting structures and the environment. The properties of water are highly dependent on its network of hydrogen bonds, which governs the interactions with solutes. Amphiphiles have a hydrophilic part (head group) that is either polar or charged and thus can participate in the hydrogen-bonding network with water. However, the hydrophobic amphiphile moiety (tail), such an medium length single hydrocarbon chain (C > 8), will not be able to hydrogen bond and will be forced out of solution to minimize the free energy (increase the number of hydrogen-bonds in the water, thus the entropy of the mixture). The sum of these interactions causes the formation of structures, where head groups interact with the water while tails are packed together away from the water: monolayers, micelles, lamellar phase(e.g., bilayers and vesicles), or a hexagonal phase (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Basic amphiphile aggregate structures. Head groups interact with water; hydrophobic tails aggregate into a hydrophobic phase. Structures shown: (A) bilayer; (B) monolayer; (C) micelle; (D) vesicle/liposome (E) Inverse hexagonal phase HII.

Figure 1.

Basic amphiphile aggregate structures. Head groups interact with water; hydrophobic tails aggregate into a hydrophobic phase. Structures shown: (A) bilayer; (B) monolayer; (C) micelle; (D) vesicle/liposome (E) Inverse hexagonal phase HII.

The structures formed are dependent on the properties of the amphiphile used, as well as the environmental constraints, such as temperature, pH, and ionic strength. The formation of structures from the differing “shapes” of amphiphiles has been hypothesized and the concept of a packing parameter has been proposed [9]. The parameter value can serve to gauge the potential structure adopted by amphiphiles, however, the theoretical prediction neglects the interactions between the hydrophobic tails in the self-assembly and as such should be used with caution [10]. It is dependent on the size of the head group relative to the tail in both length and structure (branched, unsaturated, number of). The most biologically relevant and versatile of these structures are bilayers that close themselves into vesicles, or liposomes (Figure 1D).

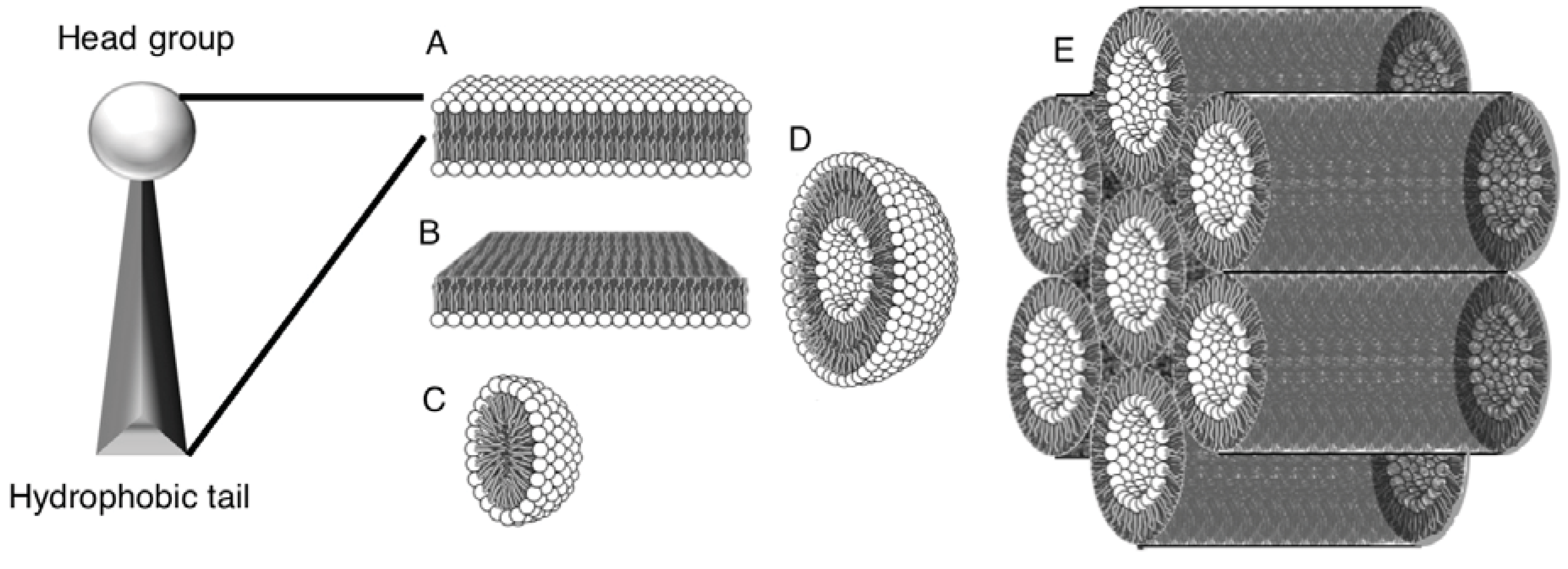

To accommodate many applications, numerous lipid varieties and mixtures have been investigated in terms of microstructure self-assembly. Most commonly phospholipids (Figure 2-(1)) are employed, as they comprise the majority of cell membranes, however more rare and complex lipid varieties have been employed for a variety of characteristics and functions to be endowed on the structures; for examples see below. Aside from phospholipids, single-chain amphiphiles (Figure 2-(2)–2-(8)) will be discussed in relation to their emergent properties, as historically, they have been the focus of early Earth research.

Figure 2.

Amphiphile chemical structures. A) Hydrophilic head groups: (1) diacyl glycerol, (2) carboxylic acid, (3) alcohol, (4) monoacyl glycerol, (5) amine, (6) trimethyl amine, (7) sulfate, (8) phosphate. B) Lipophilic tail group: (A) alkyl with 16 carbons, hexadecyl (B) alkenyl with 18-carbon octadecenyl (C) isoprenyl. R’ represents phosphocholine; R” represents isoprenyl side chains.

Figure 2.

Amphiphile chemical structures. A) Hydrophilic head groups: (1) diacyl glycerol, (2) carboxylic acid, (3) alcohol, (4) monoacyl glycerol, (5) amine, (6) trimethyl amine, (7) sulfate, (8) phosphate. B) Lipophilic tail group: (A) alkyl with 16 carbons, hexadecyl (B) alkenyl with 18-carbon octadecenyl (C) isoprenyl. R’ represents phosphocholine; R” represents isoprenyl side chains.

The study of vesicles has adopted and invented many different techniques for analysis and comparison [11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. The Critical Vesicle Concentration (CVC), which the minimal concentration of a given amphiphile needed to form vesicles, is particularly important when using single chain amphiphiles as they are characterized by a high CVC due to their reduced hydrophobic interactions compared to double-chained lipids. By carefully examining the transition from a dilute solution of monomers to a concentrated vesicle-containing suspension, it is possible to determine the steps leading up to fully formed vesicles, and thereby discover important self-assembly properties.

The pH of the solution plays a critical role in vesicle formation of ionic lipids, such as fatty acids [18]. Specifically, it is well documented that fatty acids tend to form vesicles in a pH range close to their apparent acid pKa. These amphiphiles need to be present both in deprotonated and protonated state in order to form H-bonds between their head groups, thereby stabilizing the bilayers structures. The apparent pKa increases with increasing hydrocarbon tail length. This observation may seem to be counterintuitive. Indeed, the extension of the hydrocarbon chains by methylene groups should have no chemical effect on the pKa because it is dependent only upon the electronic effects felt by the acid head group. This pKa effect is explained by the aggregation of amphiphiles into structures, which causes an increased interaction of proximal head groups as concentration increases. The net effect is a change in the equilibrium needed for acid deprotonation by the OH- from the bulk solution, resulting in the apparent increase of the fatty acid pKa [19].

It has further been shown that, as the concentration of fatty acid increases from a monomer- to a vesicle- solution, smaller aggregates are formed at intermediate concentrations. By monitoring the pKa during a dilution of vesicles, it is possible to demonstrate these structures [20]. At the beginning of the dilution experiment, the pKa does not vary and vesicles predominantly exist. Once the solution is diluted below the CVC, the pKa starts to decrease linearly with respect to concentration until it reaches a pKa ≈ 5. This linear decrease can only be explained by the formation of “pre-vesicular” aggregates. A possible pathway to self-assembly of vesicles would therefore be a first nucleation of these small aggregates that can then rapidly incorporate additional molecules into their structure, leading to the formation of stable vesicles.

Most amphiphiles will participate in bilayer formation both by themselves and in admixture under the right conditions. The mixed character of bilayer structures can impart new properties to them or alter others depending, among other things, on whether the two or more amphiphiles are miscible or not. The miscibility of two amphiphiles can be gauged by measuring the phase transition temperature (Tm) of the mixed bilayer. Tm generally decreases as the degree of unsaturation increases but is also affected by head group [21], and non-lipid molecules such as cholesterol [22]. If composed of two immiscible amphiphiles, mixed bilayers can simultaneously have distinct areas, some in a gel state (solid) and other in a liquid-crystal state (fluid) at a given temperature.

Clearly, the multi-state of the lamellar phase can directly affect bilayer permeability to hydrophilic solutes [23]. But the formation of these distinct phases often referred to as domain formation, is also known to affect various other functions in biological membranes [24]. This partitioning has also been investigated in model membranes to determine the structural effect of such domain mixtures. These domain boundaries cause curvature deformation in an effort to reduce line tension between domains [25] resulting in interesting budding effects. Rapid domain formation can even provide necessary force to induce spontaneous division of liposomes [26]. This phenomenon in itself is a property that emerges from the complex behavior of amphiphile mixtures. As these mixtures increase in number of components, such discoveries become more common and are the focus of the remainder of this review.

3. Vesicle Interactions with Small Chemicals and Polymers

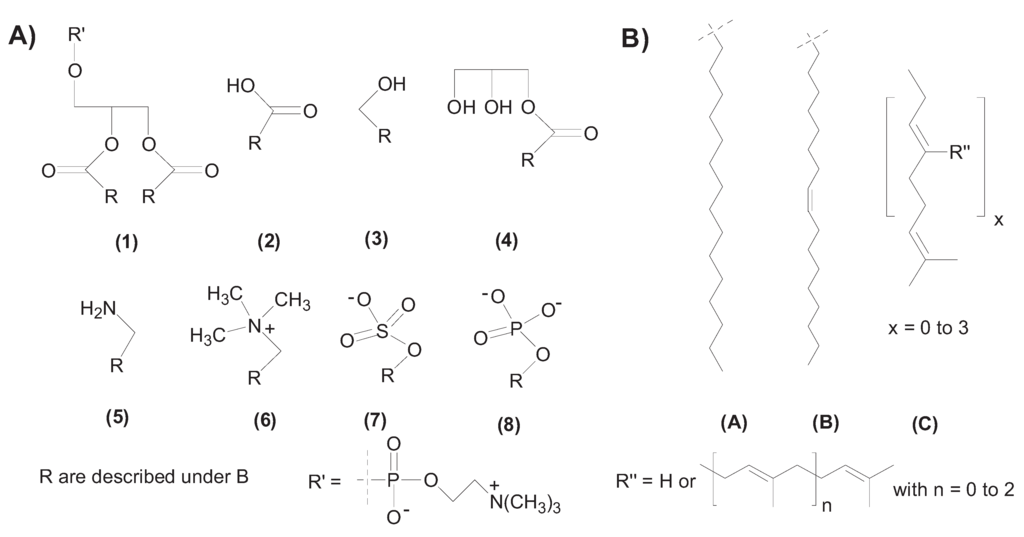

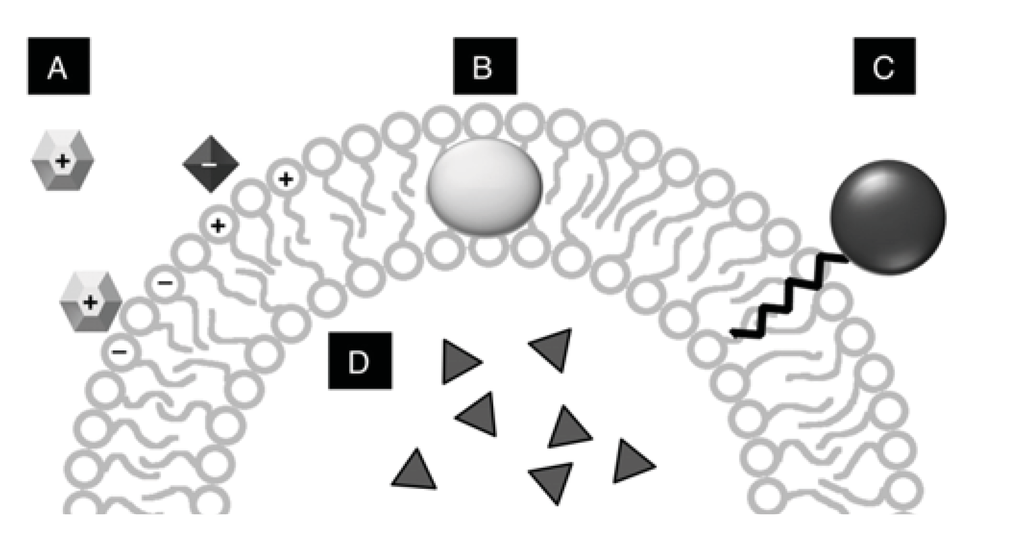

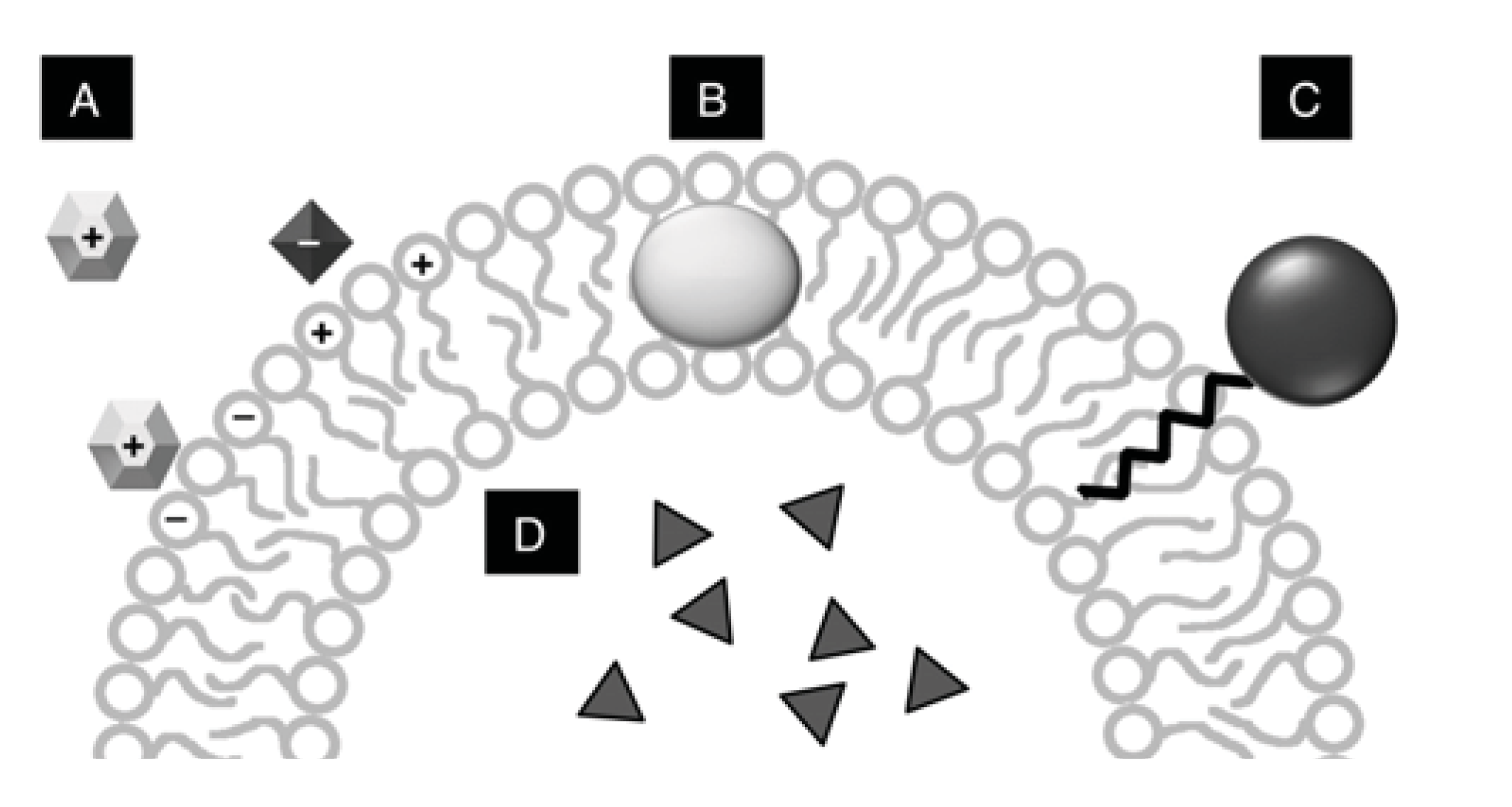

Self-assembled bilayers that form the boundaries of vesicles will interact with solutes present in their aqueous environments (Figure 3 and Table 1). Depending on the properties of the solutes, these interactions can either stabilize or destabilize the vesicles. They can occur at surfaces with ionic or hydrogen bonding, in the membrane itself as lipophilic interactions, or indirectly as solutes can be entrapped within the aqueous volume of the protocell.

3.1. Membrane Stability

Vesicles can become unstable upon exposure to stresses from the environment. Because of the extensive number of possible membrane compositions, as well as the great number and variety of solutes that contribute to amphiphile-water interactions, it is necessary to generalize these interactions. Stability depends on three different aspects of vesicle suspensions:

- Environmental factors such as temperature and pressure of the solutions can change the fluidity of the amphiphiles causing precipitation or dissolution.

- Additional solutes including salts, buffers, biomolecules, and other chemicals like residual organic solvents, or catalytic cofactors can potentially decrease the hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions of bilayers causing membrane disruption. For a full summary containing various instances see for example [27].

- The composition of the membrane considering the head and tail group type and mixtures of co-surfactants will interact with the environment and solutes in species-specific manner (e.g., anionic vesicles are sensitive to cations).

Figure 3.

Interaction zones in vesicles. (A) Electrostatic interactions, either positively or negatively charged membranes can attract ionic solutes; (B) lipophilic association within the bilayer for very hydrophobic molecules; (C) lipophilic anchor association for molecules that are polar or charged, but can be derivatized; (D) encapsulation or entrapment for aqueous solutes.

Figure 3.

Interaction zones in vesicles. (A) Electrostatic interactions, either positively or negatively charged membranes can attract ionic solutes; (B) lipophilic association within the bilayer for very hydrophobic molecules; (C) lipophilic anchor association for molecules that are polar or charged, but can be derivatized; (D) encapsulation or entrapment for aqueous solutes.

Table 1.

Summary of molecular interaction with vesicles.

| Molecular species | Internal | Surface association * | Hydrophobic association |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA | X | X | |

| RNA | X | X | |

| PAH | X | ||

| Protein | X | X | X |

| Fluorescent dyes | X | X | |

| Amino acids | X | X | |

| Molecules derivatized with hydrophobic tails** | X | ||

| Sugars | X |

* Dependent on membrane composition; ** The strength of the association will depend on the balance between the hydrophilic character and hydrophobic one, i.e., the length of the hydrocarbon chain, which has been added to the hydrophilic molecules, as shown for anchored DNA strands [28].

Additionally stability is difficult to define, as it is dependent on application. In general, stability is defined by the maintenance of an enclosed volume by the bilayer. Some stable systems are not dependent on this property, such as membrane bound metabolic complexes [6], which rely on bilayer formation, but not vesicle stability. Furthermore, some systems have more strict stability requirements such as the ability to withstand temperature fluctuations [17] or exhibiting semi-permeability [21]. For example, decanoic acid vesicles at a pH close to their pKa are stable enough for encapsulating highly charged metal-ligand complexes, but unable to encapsulate charged fluorescent dyes. This points to a sliding scale of stability, where the use defines the stable/unstable threshold. Generally, increasing the complexity of the head group(s), such as adding a co-surfactant that can hydrogen bond with more amphiphiles, will increase a vesicle system’s stability. Increasing the hydrophobicity of the tail groups will have a similar effect and can be achieved either by lengthening or increasing the number of the lipophilic tail(s) [17].

3.2. Interaction of Vesicles with Biomolecules

Interaction is a broad term that could imply vesicle interaction on several levels: encapsulation and containment in the internal volume, insertion of molecules into the hydrophobic bilayer core, or surface association with the polar head groups. A summary of these interactions is listed in Table 1. Although a larger body of literature on these interactions exist, the research described here will only focus on creating life by discussing informational and metabolically important molecules. Though not all examples are ‘emergent’, they are highly important for understanding of multicomponent chemical networks when modeling life.

For protocells to support an internalized metabolism to synthesize biopolymers, like cells but without complex membrane pores, permeability of simple building blocks through membranes is of great importance. The permeability of protons [21,29,30], water [21], ions [31,32], amino acids [33,34,35], proteins [36], nucleotides [37], DNA [38,39], and various dyes [17] has been studied in a variety of vesicle compositions. In general, larger molecules and charged molecules are less permeable than small or uncharged molecules and in the case of nucleotides the difference between a NTP and a dimer, for example pApA, is already sufficient to prevent the diffusion of the latter across membranes [27].

Ribose, as a sugar backbone, is highly important for the formation of a catalytic information molecule with regards to the RNA-world hypothesis, and therefore has been investigated along with other sugars for membrane permeation, resulting in the discovery that the permeation of ribose is faster than other aldopentoses or hexoses in both fatty acid and phospholipid membranes [40]. The distinctive conformation of ribose allows for a remarkably less polar conformation than other sugars, and hence enhances the permeability across the hydrophobic barrier [41]. This selective mechanism has been proposed to explain the nature of the early catalyst backbone (RNA ribozymes).

Hydrophobicity can do more than regulate permeation; it is also a driving force for the association of molecules. Hydrophobic bilayer character assures a much stronger interaction between certain biomolecules and vesicles than is the case with aqueous solutes, which can diffuse on and off the vesicle surface or leak from the internal contents. This association relies on the hydrophobicity of the target molecule, which leads to these substances being relatively insoluble in water.

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are sufficiently hydrophobic to phase partition into bilayers and can add new chemical functions to the resulting mixed bilayers. PAHs are used for straightforward activities such as staining bilayers for fluorescence microscopy (Nile Red, Texas Red). However, photoexcitation can also lead to more complex phenomena such as building up transbilayer pH- [42,43] or electron- gradients [44]. PAH are also useful in stabilizing bilayer structures to reduce the permeability of single chain amphiphiles [45].

The lipid-water boundary provides an alternate location for solute interaction. This surface can easily be chemically modified by altering the amphiphile composition. This effect can be seen in the encapsulation efficiency of DNA in the presence or absence of cationic lipids. The addition of a positively charged amphiphile (DDAB) to neutral phospholipid vesicles causes an increase in the encapsulation efficiency of DNA [38]. This increase in efficiency stems from the binding of the DNA to the cationic lipid, changing the structure and solubility of the DNA itself (transition from a relaxed water-solubilized structure to a condensed/aggregated structure).

These examples provide an overview of the possible interactions vesicles can have with biologically relevant molecules. These molecules once associated to vesicles would be responsible for forming chemical networks, spatially defined by the membranes, which allow further protocellular evolution, as discussed below.

3.3. Interaction between Vesicles

Sometimes overlooked, vesicle-vesicle interactions can result in important properties of simple self-assembled structures, and these interactions must be considered by researchers in both experimentally positive and negative ways. Interaction can be as limited as diffusion mediated collisions or as extensive as fusion and total integration of protocell components. Positive interaction effects can include the mixing of reaction components from separate vesicle populations or vesicle growth. Loss of homogeneity of the suspensions or loss of individual vesicle identity contributes to some of the negative effects.

One biopolymer/lipid interaction, not discussed above, has been observed with surprising morphogenic properties. Cationic liposomes composed of phospholipids (DOPE/DC-Chol) can be aggregated by the addition of plasmid DNA [46] due to the interaction of the positively charged lipid with the negatively charged DNA backbone. A variety of structures can be formed from this interaction, including linear DNA strands surrounded by “bilayer tubules”. Thus, high DNA concentrations cause the fusion of vesicles, although no quantitative study has been performed. This is a prime example of the complexity of DNA/liposome interaction and the creation of a variety of structures, some of which are the results of fusion events between vesicles.

Using tRNA, it is also possible to aggregate preformed liposomes (POPC charged with positive surfactant CTAB) [47]. This behavior is dependent on the size of the liposomes. Reversible aggregation occurred for vesicles of 160 nm in diameter but not for those with 80 nm diameter. This dissimilarity is likely due to the membrane curvature, allowing greater tRNA interaction on the gentler curve. The emergence of a vesicle selection mechanism based on size could be significant for both origins of life and artificial systems as a passive method for gathering productive protocells or it could allow growing cells to be differentiated from individuals lacking a metabolism.

Another use of nucleic acid structure could rely on hybridization of single stranded DNAs anchored on vesicles to achieve sequence-specific vesicle interaction. By derivatizing amphiphiles with nucleobase head groups [48] or complexing them with DNA strands [49], it is possible to cause the aggregation, but not fusion, of phospholipid vesicles. These controlled associations highlight the customizability when working with amphiphile structures for use in an artificial cell.

In a more prebiotically plausible system, unstable vesicle populations (fatty acids) exhibit uncontrollable spontaneous vesicle fusion. However, increasing fatty acid chain length or the addition of co-surfactants (glycerol monoacyl amphiphiles) reduces or eliminates this fusion [17]. Destabilization can be re-introduced by simple temperature fluctuation, causing greater vesicle fluidity and permeability.

In contrast, controlled mixing between vesicle populations is possible [50]. This mixing is achieved by ‘charging’ the vesicles, for example by adding small amounts of ionic amphiphiles (oleate as anionic and didodecyl dimethyl ammonium bromide as cationic amphiphiles) to uncharged phospholipid populations. Cationic vesicles will fuse with anionic vesicles, shown by the mixing of internal contents and subsequent chemical reaction.

As described in this section, simple bilayer structures used as protocellular container boundaries do more than simply encapsulate chemicals or regulate the exchanges between the container and the environments. Through various chemico-physical interactions, they can alter the properties of these chemicals and potentially lead to their organization into complex reaction and information network that should at least permit the emergence of self-maintenance, and self-reproduction properties of the whole protocell. They might also support evolution and adaptation.

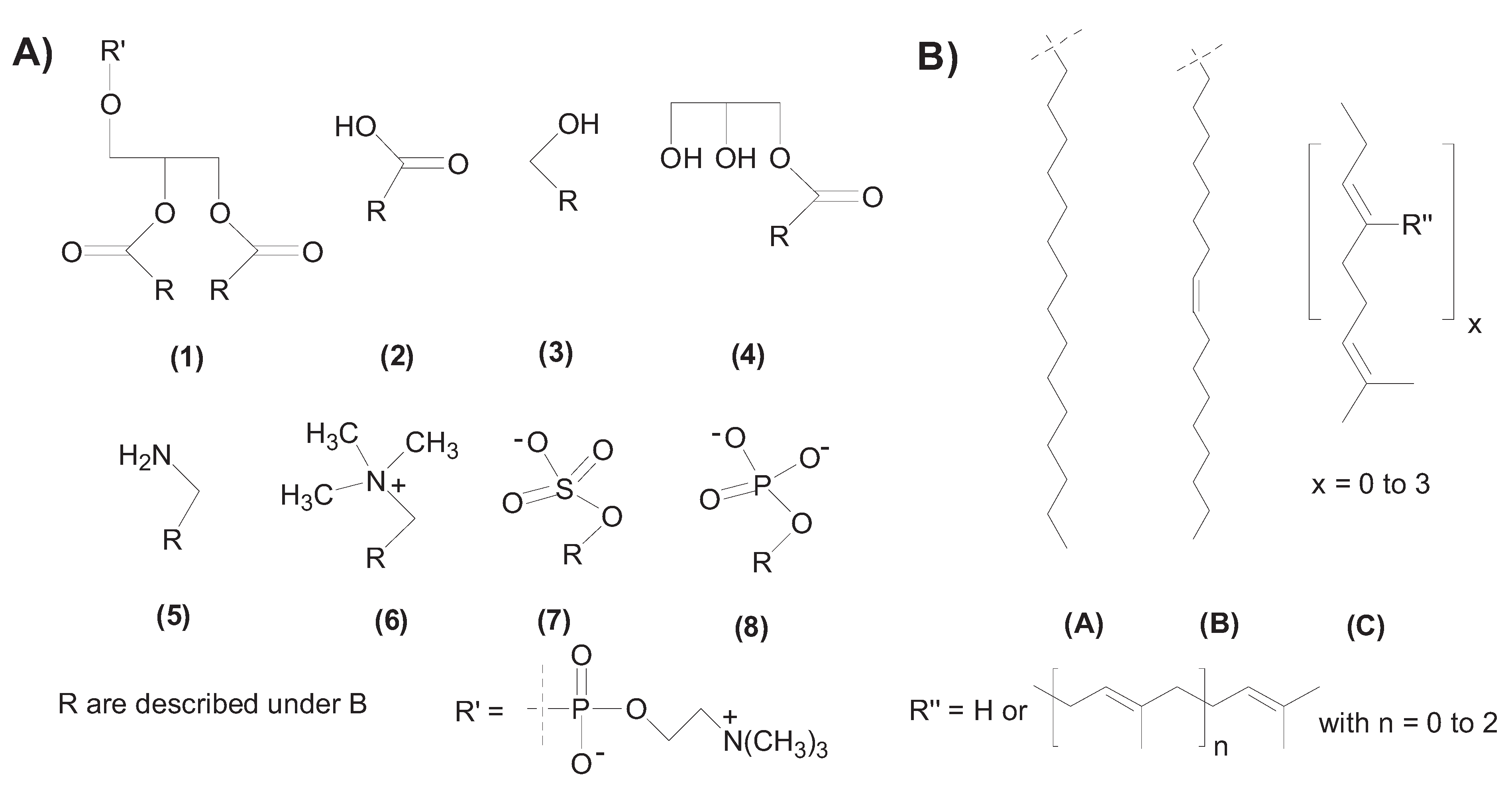

4. Membrane Related Reactions

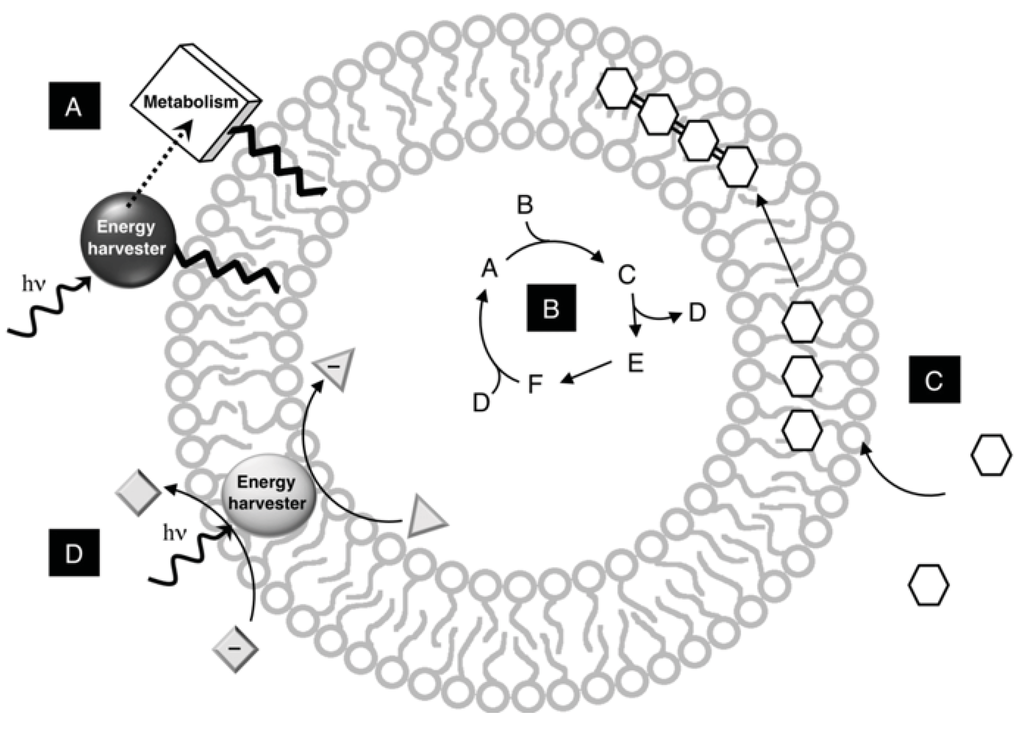

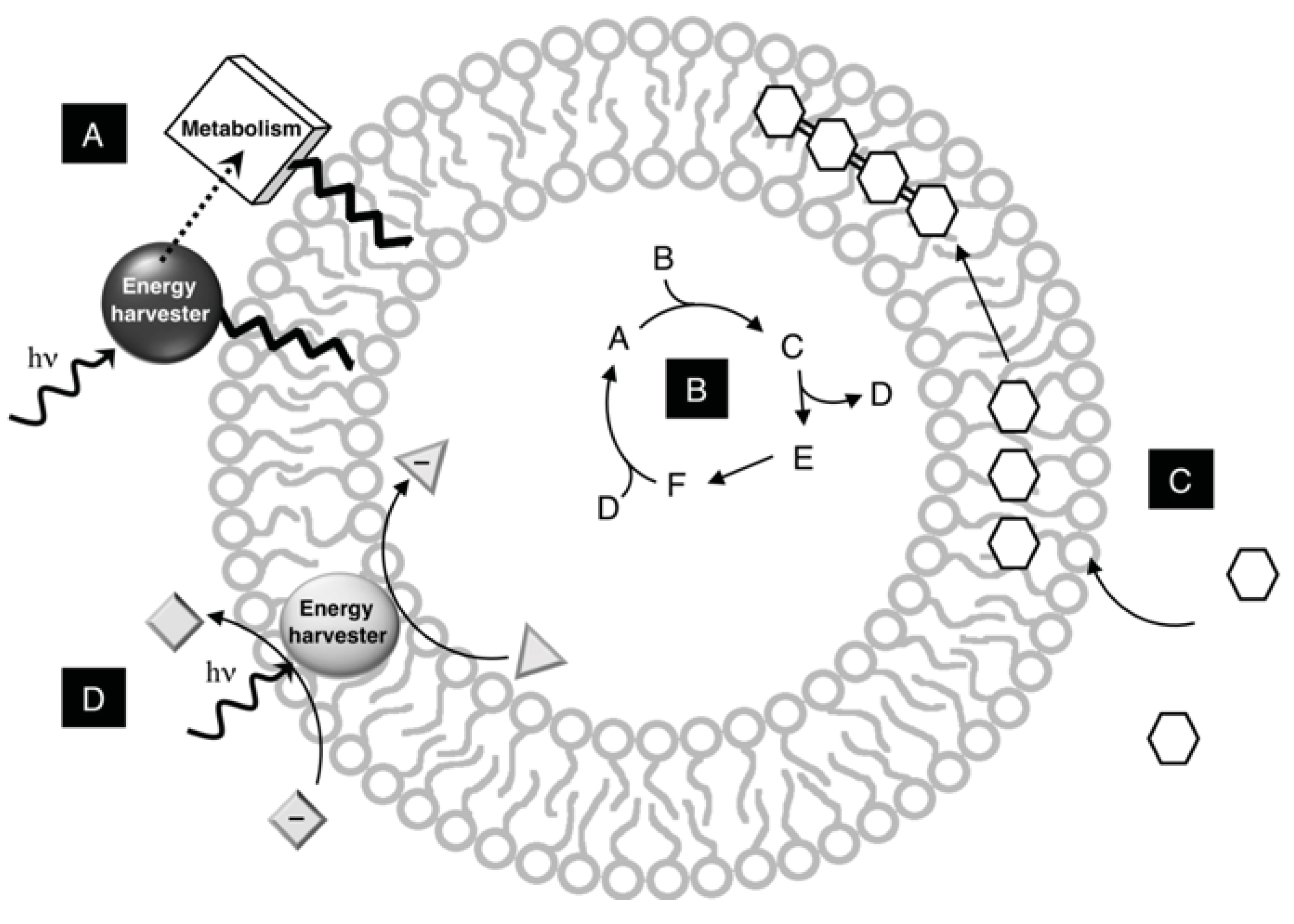

Container structures provide a rare opportunity to contain, mix, and protect molecules as discussed above, however they also provide a unique set of environments for chemical reactions to occur: in the internal volume, in the membrane, and at the lipid/water interface (Figure 4). The emergent properties of often intricate reactive networks in relation to container structures is discussed without attempting an in-depth survey of all implementations of liposomes and vesicles as bioreactors [2,51,52].

Figure 4.

Membrane functionality in model protocells. A vesicle can provide a variety of environments for protocell construction and function. (A) Metabolic complexes are anchored directly in bilayers with a lipophilic tail; (B) Metabolic networks are completely encapsulated into the internal aqueous volume of the vesicle; (C) Membranes concentrate nutrients within the bilayer, which are then polymerized; (D) Metabolic complexes are sufficiently hydrophobic to embed in the core of the bilayer to organize reactions spatially.

Figure 4.

Membrane functionality in model protocells. A vesicle can provide a variety of environments for protocell construction and function. (A) Metabolic complexes are anchored directly in bilayers with a lipophilic tail; (B) Metabolic networks are completely encapsulated into the internal aqueous volume of the vesicle; (C) Membranes concentrate nutrients within the bilayer, which are then polymerized; (D) Metabolic complexes are sufficiently hydrophobic to embed in the core of the bilayer to organize reactions spatially.

Systems where membrane support chemical reactions or reaction networks can be grouped in two broad categories: those where (i) the membranes themselves or the membrane enclosed aqueous volume serve as co-localization vessels and (ii) the membrane multiphase character is the foundation for a differentiated reaction set-up.

For historical reasons, protocell development has often focused on three types of reactions: the synthesis of biopolymers, the synthesis of other protocell building blocks, such as amphiphiles, and the uptake of energy from a primary source, such as light. The biopolymer synthesis is considered central to the origin of life due to their ability to catalyze reactions under mild conditions as well as code for the information to construct a cell, while the synthesis of other building blocks is a prerequisite for self-maintenance and self-reproduction. These central roles have led to many hypothesized scenarios to explain how life initially emerged. The energy uptake and transduction is essential to permit the emergence of truly (semi-) autonomous protocell. Some experimental evidence exists to support scenarios involving membranes as a central participant in these three processes and will be now reviewed.

4.1. Membranes as Colocalization Systems

Some complex protocell designs aim to creating a functional artificial cell with the help of reconstituted biological architectures only composed of the necessary components for protein production. This complex biological network contains about 80 molecular components but still does not represent a fully independent metabolism, and is clearly simpler than modern organisms. This large reaction network, the transcription and translation machinery, is then encapsulated within liposomes (Figure 4B). Remarkably, it can be observed that liposomes with a radius of about 100 nm harbor protein expression, and the amount of fluorescent protein in the vesicles can be, on average, about 6 times greater than in a bulk solution [53]. The expression of protein is not solely limited to fluorescent protein and the simultaneous synthesis of two functional proteins associated with the production of a lipid, phosphatic acid, is also achieved as their products can be positively identified in the system boundaries [54]. That is, the container growth is in principle linked with an internalized production of amphiphiles.

These results are comparable to those obtained using slightly larger containers (water-oil emulsions) [55] where the minimum required concentration of DNA templates is in the range of that commonly found in cells. Encapsulation also permits the acceleration of cascade reactions, as primary product concentrations grow more rapidly in the small reactor internal volume [56].

Considering that the encapsulation procedures used to prepare these liposomes achieves small encapsulation yields, only a subset of the liposomes can contain all of the necessary components. Actually, classic statistical analysis gives a negligible probability to a simultaneous encapsulation of so many components in a 100 nm radius spherical compartment. Thus, the expression improvement observed is likely much higher locally than estimated and may well represent an emergent property of encapsulated chemical networks.

A related approach toward artificial cells using cell-free expression systems as above is to look at the vesicle as a container for a “genetic circuit” [57]. In this way, it is possible to examine the possibilities and obstacles that are encountered in such complex networks from an engineering perspective. Interestingly, this research has “found” many requirements that need to be addressed for such a system. Vesicles can burst when used as a bioreactor, however the insertion of a selective pore to allow the uptake of nutrients and the release of waste, leads to a stable reaction system for days [58]. Another requirement that has emerged is the necessity of degradation. Once a messenger RNA is translated into protein, it needs to be broken down so that it is not repeatedly transcribed by the system. The feasibility of this process has been demonstrated [59] but has yet to be implemented in a vesicle.

The difficulties inherent to the usage of an enclosed transcription-translation system for protocellular metabolisms (reproduction of a functional metabolic system, genetic information control on the protocell functions, limited permeability of molecules across bilayers) have led researchers to propose an alternate approach to co-localization of reaction components (Figure 4A). The idea here is to co-localization all chemicals on the interface of a bilayer structure by anchoring the entire network to the structure as opposed to encapsulate an entire metabolism/information system inside a semi-permeable barrier [60]. In several instances, the anchoring of catalytic molecules and in part their co-factors have been conducive to improved reactions, for example the template-directed RNA polymerase ribozyme exhibited higher activity once anchored to micelles [58]. The advantages of this anchored system are numerous. Nutrients and waste products can freely diffuse to and from the metabolic/informational core of the network. It also eliminates the problem of vesicle lysis, as only the bilayer itself needs to stay intact. This system is more flexible in terms of structure type as well, where oil droplets or reverse micelles can also be used. However, it should be noted that the type and complexity of the catalytic assemblies anchored in vesicle bilayers will be limited compared to the complexity of a transcription-translation apparatus sometimes encapsulated in vesicular and liposomal protocell models.

One such an “interfacial” system has recently been proposed that envisions information and catalytic molecules all anchored in bilayers by aliphatic hydrocarbon chain moieties. Furthermore, while typically information is thought of as a distant metabolic control, the researchers foresee the information molecules not as a true encoding molecule, but rather as a sequence dependent actuator of the metabolic process that produces fatty acid from an oil-like precursor. The nucleobases should play the role of an electron donor/relay in the amphiphile-precursor photo-fragmentation catalyzed by a metal complex. The metal center is a ruthenium atom. The effectiveness of the electron relay function should depend on the base sequence of the information molecule, as the investigation of electron transfer on DNA strands has established [61]. This approach simplifies the mechanism of information utilization by a protocell and should ease protocellular reproduction.

In the current embodiment of this simplified model, the nucleic acid polymer was replaced by a single nucleobase, 8-oxoguanine [62], but this simplified version of the protocell has already allowed the investigation of several processes essential for the function of a protocell. First, a metabolic conversion of amphiphile precursors into building blocks can be achieved under modulating control of some form of information, this at a pace resulting in the growth of the container boundaries. Moreover, the role of the membrane to localize the reaction components is crucial in determining the rate of precursor conversion. The initial rate of precursor conversion into fatty acid is highly dependent on the interaction between the information, the energy harvester, and the bilayer itself. In fact, the conversion rate became less dependent on the ruthenium complex-nucleobase catalyst configuration as long as both the ruthenium and the oxoguanine were tightly associated with the bilayers. At the relatively high local concentrations of catalysts used, the advantage of the intramolecular electron transfer between the nucleobase and the ruthenium complex almost completely disappears. However, with the increasing concentrations of product a reduction in rate can be seen. Contrary to traditional product inhibition, this reduction in rate is caused by the formation/growth of the structures. This weakening of metabolism was caused by a dilution of the reactant and catalysts in the bilayer, where they are localized. These results demonstrate that the bilayer, i.e., the container, can be sufficient for the co-location needed for efficient electron transfer [63]. That is, the interactions between the container and the other two components of the protocell can alter the expected chemistry.

These steps of co-localizing information, metabolism, and container are essential for the progress of protocell design. Using the unique properties of vesicles, including their customizability, it should be possible to create a functional protocell.

4.2. Membranes as Multiphase Reaction systems and Reaction Scaffolds

The introduction of a membrane changes the dynamics of a chemical reaction when compared to bulk reactions, and could have contributed to the emergence of complex reaction networks, and ultimately protocells. Because of their multiphase properties, membranes can change the chemical environment as well as promoting spatial organization, for example by concentrating them on their surface or within their hydrophobic interior. These alterations should facilitate reactions such as polymerization by condensation of monomers, which is the main synthetic pathway to important biopolymers. For both amino and nucleic acids, enhancements of non-enzymatic polymerization, or self-condensation have been reported compared to the same type of reaction in a bulk aqueous medium.

Amino acid polymerization should lead to short random peptide strands with sufficient structural complexity to show enzymatic (catalytic) activity, as low catalytic activity was established in even peptide dimers [64]. Polycondensation of amino acids is possible in solution when monomers are activated using N-carboxyanhydride [65,66,67,68], however sequence specificity is impossible in such a situation. The introduction of a membrane changes the dynamics of the condensation reaction such that hydrophobic amino acids can be joined more efficient (high rates, yields and length of products) on membranes than in solution [69,70]. This membrane driven reaction concentrates the reactants on the surface of the bilayer, bringing them close enough to easily react. Another method can be used to concentrate and react dipeptides on the surface using a helper molecule, 2-ethoxy-1-ethoxycarbonyl-1,2-dihydroquinoline (EEDQ, a condensing agent). This reaction can be modulated by altering the surface charge of the membrane: positively charged amino acids polymerize on negative membranes and negatively charged dipeptides on positive membranes. It is also possible to sequentially add a series of amino acids (e.g., tryptophan followed by glutamic acid). The products are short oligomers that interact strongly with the reaction matrix.

In the case of nucleic acids, in particular RNA, it is strongly suggested that they played a significant role in the emergence of life (the RNA world hypothesis) as RNA can serve as both an information molecule and a catalyst [71], as opposed to DNA or peptides. As is the case for peptide polymerization, non-enzymatic polymerization of RNA oligomers from the corresponding monomers in a bulk aqueous medium has been rather difficult. The synthesis of short RNA oligomers was carried out using activated nucleotides with generally low yields. For example, non-enzymatic template replication only works efficiently for guanine derivatives on homopolymeric templates (poly-cytosine) [72]. Also, the polycondensation of monomers in bulk aqueous medium only yields dimers and traces of trimers and tetramers even at high monomer concentrations (more than 1 M) [73]. Finally, polycondensation on mineral matrices might yield longer oligomers but the yield of insertion of monomers into oligomers are low [74]. Moreover, and perhaps more importantly, the likelihood of these activated molecules under prebiotic conditions is poor, therefore non-activated nucleotide systems are being explored.

Chemical activation of the mononucleotides may not be required if synthesis of phosphodiester bonds could be driven by the chemical potential of fluctuating anhydrous and hydrated conditions, with heat providing activation energy during dehydration [75]. Amphiphile bilayers that compose vesicles or liposomes could represent a model for such a fluctuating environment. The molecular arrangement of the bilayer seems to be preserved when vesicles are dehydrated (D.W. Deamer, personal communication). If small molecules, such as RNA monomers, are present in the aqueous medium during the dehydration, they will be trapped between fragments of the amphiphile bilayers, and likely ordered into a structure potentially conducive to polymerization. In this way, it was possible to polycondensate RNA nucleotides up to products with 100 monomer units [75], as membranes likely ordered the monomers while dehydration concentrated them.

Amphiphile structures and their interfaces can also serve as reaction media that allow for the reactions to occur [76]. Among those, some such as the hydrolysis of fatty acid anhydrides are highly relevant to the protocell design. The hydrolysis of fatty acid anhydrides into fatty acids occurs spontaneously in water [77]. This reaction is initially slow, however, after a concentration above the CVC of the product has been achieved, a rate increase is observed. Indeed, the addition of preformed vesicles to the neat anhydride oil in water increased the initial rate of hydrolysis significantly pointing to autocatalysis. This reaction, however, is a downhill process (a high-energy bond is broken) and the “catalysis” in this case is a side effect of the vesicle-induced solubility, rather than of a cellular synthetic network that produces more amphiphiles from nutrients.

To realize a truly up-hill reaction, the uptake of energy and its conversion into chemical bonds (energy transduction process) is necessary and usually is a two-electron transfer reaction. Here again, protocell membranes could play a crucial role, as their counterparts in cells do it, and the question of whether these simple structures (compared to cellular membranes) can maintain gradients during their build-up until the gradient amplitude is large enough to allow it to drive uphill reactions. It is possible to create a chemical gradient across a membrane using simple photosensitive membrane bound PAHs as shown with a simple chemical network [44]. In this system, a PAH, [2,3a]-naphthopyrene spontaneously associated with the fatty acid bilayers of vesicles which contained encapsulated ferricyanide, while EDTA was present in the external medium. Upon irradiation of the vesicles, trans-membrane electron transfer between EDTA and ferricyanide was induced by the excited PAH. This PAH photochemistry occurred without substantial decomposition of the chromophores or vesicles. That is, this network created a chemical potential that is yet to be harnessed for further reactions.

The actual transduction of light energy was demonstrated in experiments aiming at creating artificial photosynthetic systems [6,78]. Using a complex photosensitizing system with light-sensitive molecules called antennae and F0F1-ATP synthases at its core, the authors created a functional light harvesting system that produces ATP from ADP. Self-assembled bilayers provided the framework necessary to achieve vectorial organization of all molecules, i.e., permitted the arrangement of the complex machinery as to transduce light energy into chemical bonds. That is, even rather simple bilayers composed of one phospholipid, POPC, can be used to sequentially create a pH gradient strong enough to the permit ATP synthesis (which requires 4 equivalent protons for each ATP produced). Artificial bilayers can therefore achieve a vectorial flow in a chemical network similar to those observed in biology.

The preceding discussion on sequential steps for creating an emergent living system is only the beginning of a long process of discovery. Interesting research concerning the combination of membranes with complex chemical reaction networks, focusing on spatial organization and the maintenance of chemical gradients will be at the forefront of both the artificial life and origins of life fields.

5. Conclusions and Outlook

It has been suggested that emergent properties of chemical systems are simply complexities that are not yet understood, and that greater understanding will reduce their number [79]. In relation to the complex properties of chemical networks, it is historically true that as new analytical methods and technologies are developed greater information is available to evaluate weak but important interactions/forces, and therefore gain a greater understanding on how life is achieved.

These weak forces have played a great role in understanding living systems in the same way that chemical bonds were crucial to the understanding of basic chemistry. This is highlighted well with the example of the simplicity of bilayer self-assembly, which is influenced by a range of environmental conditions. Furthermore, the interactions of these structures with anywhere from ions up to large biopolymers emphasizes their versatility and possibilities for expanding our understanding of how we can create our own “living systems” (either as models for systems present on the early Earth or as Artificial living cells), and the properties that emerge from such systems.

Much progress has been made in attaining the individual and even multiple functions seen in living cells. This makes it likely that the successful construction of a protocell will occur in the near future, but the main extent obstacle is the true integration of all functions in a single self-maintaining, self-reproducing system capable of evolution, thereby truly possessing emergent properties. Indeed, as shown for the container in this review, each component of the protocell (container, metabolism and information) might alone or through interactions with the one or another component already exhibit abilities that could be considered emergent properties. Thus, it seems to be reasonable to attempt the design of protocells [60] in a systemic approach, i.e., construct them with all their components present even in an extremely simplified manner.

Protocells, however, are inherently non-living and strive to define the requirements and limits of abridged metabolic, informational, and structural interactions. Using these systems, biology could slowly emerge from chemistry and narrow the definition of what “alive” really means. The creation of an artificial cell has promise to be one of the great challenges of the 21st century.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Members of the Center for Fundamental Living Technology (FLinT), in particular Anders N. Albertsen, for many discussions. This work was supported by FLinT at the University of Southern Denmark and its sponsors, the Danish Research Foundation Professorship and the University of Southern Denmark.

References

- Szostak, J.W.; Bartel, D.P.; Luisi, P.L. Synthesizing life. Nature 2001, 409, 387–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luisi, P.L.; Ferri, F.; Stano, P. Approaches to semi-synthetic minimal cells: A review. Naturwissenschaften 2006, 93, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, S.; Chen, L.; Nilsson, M.; Abe, S. Bridging nonliving and living matter. Artif. Life 2003, 9, 269–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agresti, J.J.; Kelly, B.T.; Jaschke, A.; Griffiths, A.D. Selection of ribozymes that catalyse multiple-turnover Diels-Alder cycloadditions by using in vitro compartmentalization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 16170–16175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomura, S.M.; Tsumoto, K.; Hamada, T.; Akiyoshi, K.; Nakatani, Y.; Yoshikawa, K. Gene expression within cell-sized lipid vesicles. ChemBioChem 2003, 4, 1172–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberg-Yfrach, G.; Rigaud, J.-L.; Durantini, E.N.; Moore, A.L.; Gust, D.; Moore, T.A. Light-driven production of ATP catalyzed by F0F1-ATP synthase in an artificial photosynthetic membrane. Nature 1998, 392, 479–482. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Miller, S.L.; Urey, H.C. Organic compound synthesis on the primitive earth. Science 1959, 130, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, L. Inorganic molecular capsules: From structure to function. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 3576–3578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Israelachvili, J. Intermolecular and Surface Forces, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Nagarajan, R. Molecular packing parameter and surfactant self-assembly: The neglected role of the surfactant tail. Langmuir 2001, 18, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milsmann, M.H.W.; Schwendener, R.A.; Weder, H.-G. The preparation of large single bilayer liposomes by a fast and controlled dialysis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1978, 512, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talsma, H.; Van Steenbergen, M.; Borchert, J.C.H.; Crommelin, D.J.A. A novel technique for the One-Step preparation of liposomes and nonionic surfactant vesicles without the use of organic solvent. Liposome formation in acontinuous gas stream: the BUBBLE method. J. Pharm. Sci. 1994, 83, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortara, R.A.; Quina, F.H.; Chaimovich, H. Formation of closed vesciles from a simple phosphate diester. Preparation and some properties of vesicles of Dihexadecyl phosphate. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1978, 81, 1080–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnard, P.A.; Deamer, D.W. Preparation of vesicles from nonphospholipid amphiphiles. Meth. Enzymology 2003, 372, 133–151. [Google Scholar]

- Domazou, A.S.; Luisi, P.L. Size distribution of spontaneously formed liposomes by the alcohol injection method. J. Liposome Res. 2002, 12, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castile, J.D.; Taylor, K.M.G. Factors affecting the size distribution of liposomes produced by freeze-thaw extrusion. Int. J. Pharm. 1999, 188, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, S.E.; Deamer, D.W.; Boncella, J.M.; Monnard, P.A. Chemical evolution of amphiphiles: glycerol monoacyl derivatives stabilize plausible prebiotic membranes. Astrobiology 2009, 9, 979–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hargreaves, W.R.; Deamer, D.W. Liposomes from ionic, single-chain amphiphiles. Biochem. US 1978, 17, 3759–3768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cistola, D.P.; Atkinson, D.; Hamilton, J.A.; Small, D.M. Phase-behavior and bilayer properties of fatty-acids—hydrated 1-1 acid soaps. Biochem. US 1986, 25, 2804–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanicky, J.R.; Shah, D.O. Effect of premicellar aggregation on the pK(a) of fatty acid soap solutions. Langmuir 2003, 19, 2034–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula, S.; Volkov, A.G.; VanHoek, A.N.; Haines, T.H.; Deamer, D.W. Permeation of protons, potassium ions, and small polar molecules through phospholipid bilayers as a function of membrane thickness. Biophys. J. 1996, 70, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullen, T.P.W.; Lewis, R.N.A.H.; McElhaney, R.N. Differential scanning calorimetric study of the effect of cholesterol on the thermotropic phase behavior of a homologous series of linear saturated phosphatidylcholines. Biochem. US 1993, 32, 516–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, H.; Okada, S. Ethanol-enhanced permeation of phosphatidylcholine/ phosphatidylethanolamine mixed liposomal membranes due to ethanol-induced lateral phase separation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1996, 1283, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnovsky, M.J.; Kleinfeld, A.M.; Hoover, R.L.; Klausner, R.D. The concept of lipid domains in membranes. J. Cell. Biol. 1982, 94, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumgart, T.; Hess, S.T.; Webb, W.W. Imaging coexisting fluid domains in biomembrane models coupling curvature and line tension. Nature 2003, 425, 821–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inaoka, Y.; Yamazaki, M. Vesicle fission of giant unilamellar vesicles of liquid-ordered-phase membranes induced by amphiphiles with a single long hydrocarbon chain. Langmuir 2007, 23, 720–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deamer, D.W.; Dworkin, J.P. Chemistry and physics of primitive membranes. Top. Curr. Chem. 2005, 259, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsen, U.; Simonsen, A.C.; Vogel, S. DNA-controlled assembly of soft nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 10462–10463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deamer, D.W.; Gutknecht, J. Proton permeation through model membranes. Methods Enzymol. 1986, 127, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Deamer, D.W. Proton permeation of lipid bilayers. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 1987, 19, 457–479. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Paula, S.; Deamer, D.W. Permeation of chloride, bromide, and iodide across phospholipid bilayers. Biophys. J. 1997, 72, Th341–Th341. [Google Scholar]

- Paula, S.; Deamer, D.W. Membrane permeability barriers to ionic and polar solutes. Membr. Permeabil. 1999, 48, 77–95. [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti, A.C.; Deamer, D.W. Permeation of membranes by the neutral form of amino-acids and peptides - relevance to the origin of peptide translocation. J. Mol. Evol. 1994, 39, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakrabarti, A.C.; Deamer, D.W. Permeability of lipid bilayers to amino-acids and phosphate. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1992, 1111, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harang, E.A.; Deamer, D.W. Amino-acid permeability across liposome bilayers. Biophys. J. 1990, 57, A487–A487. [Google Scholar]

- Walde, P.; Goto, A.; Monnard, P.A.; Wessicken, M.; Luisi, P.L. Oparins reactions revisited-enzymatic-synthesis of poly(adenylic acid) in MICELLES and self-reproducing vesicles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 7541–7547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnard, P.A.; Deamer, D.W. Nutrient uptake by protocells: A liposome model system. Orig. Life Evol. Biosphere 2001, 31, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnard, P.A.; Oberholzer, T.; Luisi, P. Entrapment of nucleic acids in liposomes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1997, 1329, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansy, S.S.; Schrum, J.P.; Krishnamurthy, M.; Tobe, S.; Treco, D.A.; Szostak, J.W. Template-directed synthesis of a genetic polymer in a model protocell. Nature 2008, 454, 122–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacerdote, M.G.; Szostak, J.W. Semipermeable lipid bilayers exhibit diastereoselectivity favoring ribose. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 6004–6008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, C.Y.; Pohorille, A. Permeation of membranes by ribose and its diastereomers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 10237–10245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escabi-Perez, J.R.; Romero, A.; Lukac, S.; Fendler, J.H. Aspects of artificial photosynthesis. Photoionization and electron transfer in dihexadecylphosphate vesicles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979, 101, 2231–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deamer, D.W. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: primitive pigment systems in the prebiotic environment. Adv. Space Res. 1992, 12, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cape, J.L.; Monnard, P.A.; Boncella, J.M. Prebiotically relevant mixed fatty acid vesicles support anionic solute encapsulation and photochemically catalyzed trans-membrane charge transport. Chem. Sci. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namani, T.; Deamer, D.W. Stability of model membranes in extreme environments. Orig. Life Evol. Biosphere 2008, 38, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sternberg, B.; Sorgi, F.L.; Huang, L. New structures in complex formation between DNA and cationic liposomes visualized by freeze-fracture electron microscopy. FEBS Lett. 1994, 356, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luisi, P.L.; de Souza, T.P.; Stano, P. Vesicle behavior: In search of explanations. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 14655–14664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berti, D.; Luisi, P.L.; Baglioni, P. Molecular recognition in supramolecular structures formed by phosphatidylnucleosides-based amphiphiles. Colloid Surface A 2000, 167, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadorn, M.; Eggenberger Hotz, P. DNA-mediated self-assembly of artificial vesicles. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caschera, F.; Stano, P.; Luisi, P.L. Reactivity and fusion between cationic vesicles and fatty acid anionic vesicles. J. Coll. Interface Sci. 2010, 345, 561–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walde, P.; Ichikawa, S. Review. Enzyme inside lipid vesicles: preparation, reactivity and applications. Biomol. Eng. 2001, 18, 143–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnard, P.A.; DeClue, M.S.; Ziock, H.J. Organic nano-compartments as biomimetic reactors and protocells. Curr. Nanosci. 2008, 4, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira de Souza, T.; Stano, P.; Luisi, P.L. The minimal size of liposome-based model cells brings about a remarkably enhanced entrapment and protein synthesis. ChemBioChem 2009, 10, 1056–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuruma, Y.; Stano, P.; Ueda, T.; Luisi, P.L. A synthetic biology approach to the construction of membrane proteins in semi-synthetic minimal cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1788, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tawfik, D.S.; Griffiths, A.D. Man-made cell-like compartments for molecular evolution. Nat. Biotechnol. 1998, 16, 652–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishikawa, K.; Sato, K.; Shima, Y.; Urabe, I.; Yomo, T. Expression of a cascading genetic network within liposomes. FEBS Lett. 2004, 576, 387–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noireaux, V.; Bar-Ziv, R.; Godefroy, J.; Salman, H.; Libchaber, A. Toward an artificial cell based on gene expression in vesicles. Phys. Biol. 2005, 2, P1–P8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noireaux, V.; Libchaber, A. A vesicle bioreactor as a step toward an artificial cell assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 17669–17674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, J.; Noireaux, V. Study of messenger RNA inactivation and protein degradation in an Escherichia coli cell-free expression system. J. Biol. Eng. 2010, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, S.; Chen, L.H.; Deamer, D.; Krakauer, D.C.; Packard, N.H.; Stadler, P.F.; Bedau, M.A. Transitions from nonliving to living matter. Science 2004, 303, 963–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giese, B. Electron transfer in DNA. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2002, 6, 612–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeClue, M.S.; Monnard, P.A.; Bailey, J.A.; Maurer, S.E.; Collis, G.E.; Ziock, H.J.; Rasmussen, S.; Boncella, J.M. Nucleobase mediated, photocatalytic vesicle formation from an ester precursor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 931–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurer, S.E.; DeClue, M.S.; Albertsen, A.N.; Dörr, M.; Kuiper, D.S.; Ziock, H.; Rasmussen, S.; Boncella, J.M.; Monnard, P.-A. Interactions between catalyst and amphiphilic structures and their implications for a protocell model. ChemPhysChem 2011, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Hatfield, S.; Wan, R.; Zhu, Q.; Li, X.; McMills, M.; Ma, Y.; Li, J.; Brown, K.L.; He, C.; Liu, F.; Chen, X. Dipeptide seryl-histidine and related oligopeptides cleave DNA, protein, and a carboxyl ester. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2000, 8, 2675–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Orgel, L.E. Polymerization of beta-amino acids in aqueous solution. Orig. Life Evol. Biosphere 1998, 28, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.R., Jr.; Orgel, L.E. Oligomerization of negatively-charged amino acids by carbonyldiimidazole. Orig. Life Evol. Biosphere 1996, 26, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehler, K.W.; Orgel, L.E. N,N′-carbonyldiimidazole-induced peptide formation in aqueous solution. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1976, 434, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brack, A. Selective emergence and survival of early polypeptides in water. Orig. Life Evol. Biosphere 1987, 17, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blocher, M.; Liu, D.J.; Walde, P.; Luisi, P.L. Liposome-assisted selective polycondensation of alpha-amino acids and peptides. Macromolecules 1999, 32, 7332–7334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blocher, M.; Liu, D.J.; Luisi, P.L. Liposome-assisted selective polycondensation of alpha-amino acids and peptides: The case of charged liposomes. Macromolecules 2000, 33, 5787–5796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, W. Origin of life - the Rna world. Nature 1986, 319, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohidi, M.; Zielinski, W.S.; Chen, C.H.; Orgel, L.E. Oligomerization of 3′-amino-3′deoxyguanosine-5′phosphorimidazolidate on a d(CpCpCpCpC) template. J. Mol. Evol. 1987, 25, 97–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanavarioti, A. Dimerization in highly concentrated solutions of phospho-imidazolide activated mononucleotides. Orig. Life Evol. Biosphere 1997, 27, 357–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, J.P. Montmorillonite catalysis of 30–50 mer oligonucleotides: Laboratory demonstration of potential steps in the origin of the RNA world. Orig. Life Evol. Biosphere 2002, 32, 311–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajamani, S.; Vlassov, A.; Benner, S.; Coombs, A.; Olasagasti, F.; Deamer, D. Lipid-assisted synthesis of RNA-like polymers from mononucleotides. Orig. Life Evol. Biosphere 2008, 38, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vriezema, D.M.; Aragones, M.C.; Elemans, J.A.A.W.; Cornelissen, J.J.L.M.; Rowan, A.E.; Nolte, R.J.M. Self-assebled nanoreactors. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 1445–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walde, P.; Wick, R.; Fresta, M.; Mangone, A.; Luisi, P.L. Autopoietic self-reproduction of fatty-acid vesicles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 11649–11654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg-Yfrach, G.; Liddell, P.A.; Hung, S.-C.; Moore, A.L.; Gust, D.; Moore, T.A. Conversion of light energy to proton potential in liposomes by artificial photosythetic reaction centres. Nature 1997, 389, 239–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balazs, A.C.; Epstein, I.R. Chemistry, emergent or just complex? Science 2009, 325, 1632–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2011 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).