Abstract

There is an increasing number of academic and regulatory investigations into the behavioral and psychological implications of using Buy Now, Pay Later (BNPL) services due to their rapid growth. There have been extensive investigations into impulse purchases using BNPL services; however, there has been relatively little focus placed upon examining post-purchase regret associated with BNPL service use. The purpose of this paper is to present a systematic review of the extant literature investigating how BNPL service use relates to both impulsive purchasing behavior and post-purchase regret. A total of ten empirical studies were identified through a comprehensive search of the Scopus database according to the PRISMA 2020 guidelines, which were all published between 2018 and 2025. The results indicated that BNPL features, including deferred payments, perceived affordability, and urgency cues, are consistent predictors of both greater impulsive purchasing and lower levels of payment salience. The results of this review, however, reveal that many existing studies have failed to directly measure post-purchase regret and instead rely on proxy indicators, including financial distress, emotional discomfort, and decreased well-being. These findings, therefore, highlight a major theoretical and methodological void in the existing literature. In addition, by providing a synthesis of the current evidence base, this review aims to provide a clearer understanding of how BNPL features influence both consumer decision-making processes and post-purchase emotional responses; additionally, this review highlights the necessity for future research to utilize valid measures of regret, longitudinal designs and ethically informed analytical frameworks when investigating the psychological impacts of adopting BNPL services.

1. Introduction

The rapid increase of Buy Now, Pay Later (BNPL) services between 2018 and 2025 has dramatically altered the world of global consumer finance by enabling users to buy things now and pay later using interest-free instalments. With an accelerating pace of digital commerce and maturing fintech infrastructures, BNPL use has rapidly expanded across both developed and developing countries [1,2]. Younger generations are taking advantage of BNPL due to its flexibility and accessibility compared to traditional forms of credit [3].

Behavioural finance suggests that BNPL minimises the “pain of payment” for consumers by changing the way they view their payments in terms of smaller instalments, which results in less cognitive resistance to spending [4,5]. While BNPL has helped democratize the ability of people to make purchases, the rate at which BNPL has grown has led to a large amount of academic, ethical, and regulatory scrutiny of BNPL. Behavioural nudges used in BNPL marketing strategies, including instalment framing, urgency cues, and loss aversion appeals, are being identified as behavioural nudges that can lead to consumers making impulsive purchases [6,7].

Post-purchase regret is defined as a consumer’s feelings of remorse after making an impulse purchase based upon comparisons between what was purchased and what could have been bought instead [8]. Regret affects consumers’ future purchasing behaviours, loyalty, and ultimately affects their overall financial health. Although there is a large body of research examining impulse buying and regret in the area of consumer behaviour, very little research has examined the constructs of impulse buying and regret in the context of BNPL.

Three gaps define the current state of academic literature.

First, BNPL serves as a payment service as well as a persuasive marketing platform designed to change how consumers perceive prices and diminish their subjective financial risks. Very few studies have explored how BNPLs’ marketing tactics transform into impulse purchases and consumers’ emotional reactions to those purchases.

Second, most of the existing BNPL research has focused on identifying factors that contribute to the adoption of BNPL, understanding consumers’ perceptions of financial risk associated with BNPL, and exploring regulatory issues [9,10]. There has been very little attention paid to the psychological consequences of BNPL use.

Third, although previous studies have demonstrated links between digital payment tools, such as mobile wallets and e-banking apps, and impulsive consumption [11], the combination of BNPL characteristics—including delayed payment salience and algorithmic nudging—is relatively new to the theory of impulsive behaviour.

Recent studies indicate several possible areas of concern: impulsivity may be a mediator of risky debt [12]; compulsive BNPL behaviour may be due to materialism [13]; mindfulness may be a protective factor [14]; and social comparison may be a moderating variable in BNPL-related well-being [15]. However, among the studies that explore these emerging concerns, the direct and validated measurement of post-purchase regret is missing. Researchers have relied on proxy measures, including financial distress, decreased well-being or dissatisfaction, thus leaving an important emotional outcome of BNPL use unexplored.

Therefore, this study performs a systematic and integrated examination of BNPL research between 2018 and 2025 to describe the development of theories, methods, and evidence regarding the relationship between BNPL use, impulsive buying, and post-purchase regret. Utilising PRISMA 2020 guidelines [16] and the CASP appraisal [17], this study identifies the conceptual gaps, provides an overview of the current knowledge, and establishes a framework for future research. The purpose of this study is to integrate a fragmented body of research related to BNPL use and to identify the role of regret within BNPL-related behavioural outcomes.

Furthermore, to provide information for scholars, policymakers, and practitioners who seek to develop innovations in BNPL that are consistent with consumer protection and overall financial well-being.

A reason for expanding the literature on post-purchase regret is that we can no longer see regret as simply an emotional response to the quality of the products purchased, but rather, regret is now recognized to be a complex affective—cognitive response to purchasing decisions made by consumers in modern retail environments. Regret has traditionally been understood within consumer research as a type of counterfactual emotion, which is a cognitive response to the idea that one’s current situation could have been better if they had selected another option [8,18]; therefore, it is distinguishable from dissatisfaction, which is generally defined by expectation-disconfirmation logic, i.e., consumers perceive how well the product performs compared to what was expected [19,20]. Self-report scales have been widely used as a method of assessing regret after purchase, utilizing established measures of self-blame and the feeling of making an incorrect purchasing decision [18,21]. In addition, the most recent findings suggest that regret may lead to actual post-purchase behavior (e.g., writing negative reviews about products purchased, returning products) in digital marketplaces, thus further illustrating the relevance of regret in the context of e-commerce [22,23].

2. Methodology

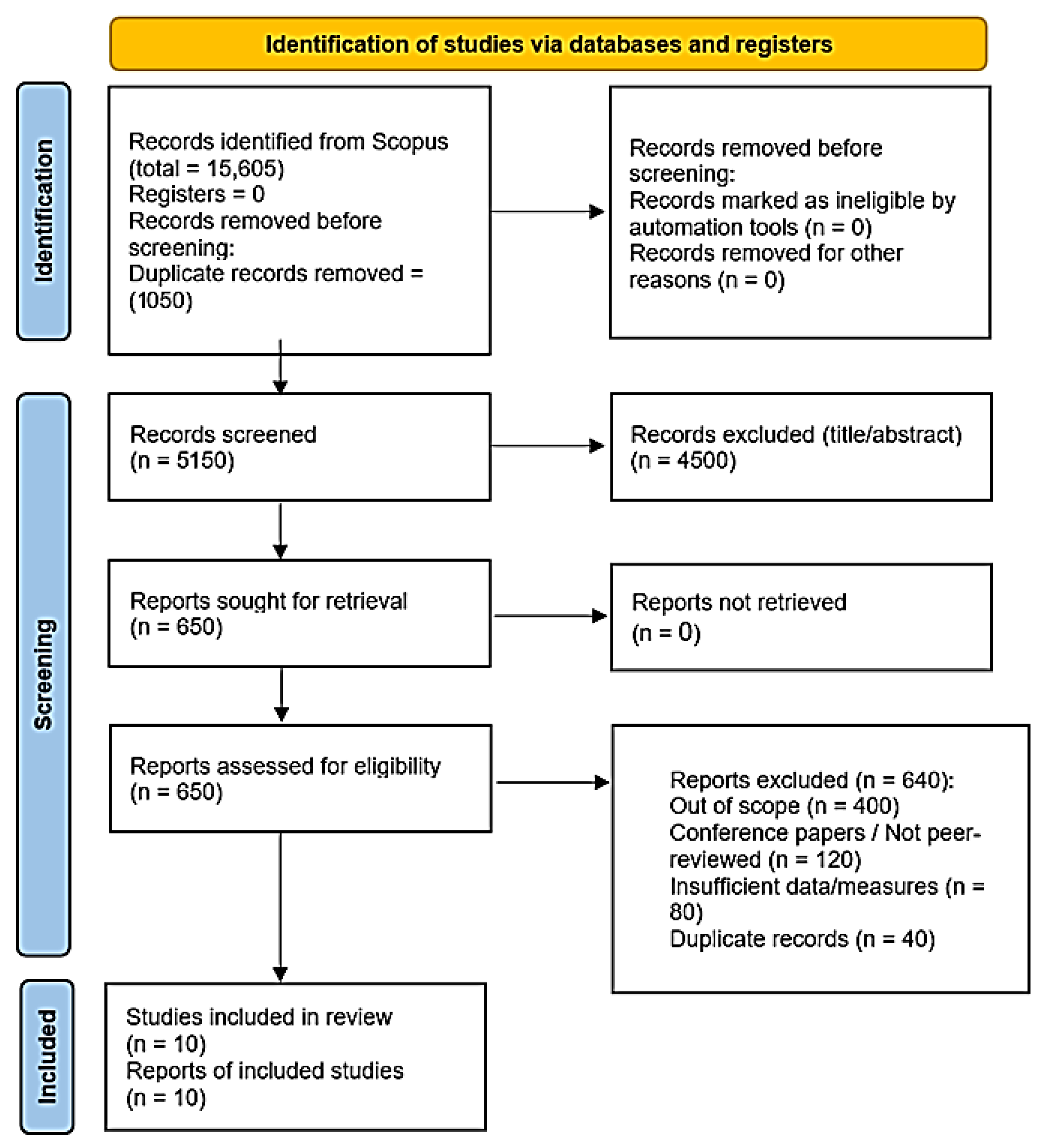

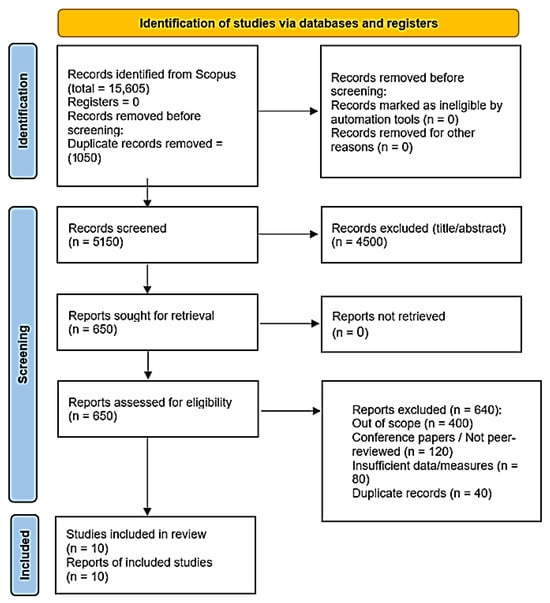

To ensure methodological rigour and transparency, this systematic review was conducted and reported in full accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines [16,24]. A completed PRISMA 2020 checklist is provided in Appendix A, and the study selection process is illustrated using a PRISMA 2020 flow diagram (Figure 1). The review protocol was developed a priori to guide the search strategy, screening procedures, and data extraction processes; however, it was not formally registered in an international registry such as PROSPERO or the Open Science Framework (OSF).

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for study selection (2018–2025).

Database searches were conducted between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2025 to ensure comprehensive coverage of the existing literature on Buy Now, Pay Later (BNPL) services. The methodological design followed four sequential stages consistent with best practices for conducting rigorous systematic reviews in business and consumer research [25]: (i) identification of relevant studies through a structured database search; (ii) screening and eligibility assessment based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria; (iii) systematic data extraction and synthesis; (iv) critical appraisal of the methodological quality of the included studies. By integrating these stages, the review strikes an appropriate balance between breadth of coverage and analytical depth, allowing for a robust synthesis of evidence at the intersection of BNPL adoption, impulsive buying, and post-purchase regret.

2.1. Search Strategy

This review utilised Scopus as its primary database, due to its broad scope of high-quality journals across fields of study, including Business, Marketing, Psychology and Behavioural Finance. This selection is supported by several systematic reviews in Consumer Behaviour that have used Scopus in recent years [26,27], thereby providing both quality and breadth of relevant data.

A search strategy was applied between the dates of 1 January 2010, and 31 December 2025. To capture the fundamental constructs of interest, a Boolean search query was created to apply to the title, abstract, and keyword fields of each potential record:

(“Buy Now Pay Later” or “BNPL”) AND (“impulsive buying” or “impulse buying” or “impulsive purchase” or “impulse purchase”) AND (“post-purchase regret” or “consumer regret” or “purchase regret”) AND (“behavioural finance” or “consumer behaviour” or “digital payment”).

Only peer-reviewed journal articles written in the English language, along with review-type papers, were retained within this analysis. All conference papers, book chapters, and grey literature were excluded from the study. Search results were exported into both CSV and BibTex formats to assist in the screening process and reference management, while adhering to the established guidelines for transparency regarding search strategies [24].

This review utilized the Scopus database to provide the exclusive source for the identification of all relevant studies. The reason for selecting the Scopus database was its ability to be a large, source-neutral abstract and citation database that is independently curated by a Content Selection and Advisory Board (CSAB), and covers many peer-reviewed scholarly journals across many different disciplines, such as the social sciences and business-related fields [28]. Studies comparing methodologies have shown that the Scopus database indexes a higher number of active scholarly journals than the Web of Science Core Collection [29]. It has also been demonstrated that the differences in database coverage can lead to meaningful variations in retrieved corpora within interdisciplinary areas [26,30]. The emphasis of evidence synthesis methodology suggests that the selection of the search system can affect recall, reproducibility, and inclusiveness; using a single database may result in missing unique relevant records that are indexed elsewhere. Future reviews would likely benefit from the use of multiple databases (e.g., Scopus and Web of Science) and/or additional search methods specific to the discipline being reviewed [31,32,33,34].

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Appropriate inclusion and exclusion criteria were utilised to narrow down the sample size of the identified studies. The search time frame included peer-reviewed articles from 1 January 2010 to 31 December 2025. Only those articles that have a publication date of 1 January 2018 through 31 December 2025 are eligible for inclusion in this review because this time frame corresponds with increased globalisation and proliferation of BNPL services [1,2].

Articles were included if they (i) explicitly examined BNPL in relation to impulsive buying and/or post-purchase regret; (ii) reported empirical or conceptual contributions within the domains of consumer behaviour, behavioural finance, or marketing; (iii) were peer-reviewed and written in English. Publications were excluded if they were outside the subject scope (e.g., engineering, medicine), not peer-reviewed, not in English, or did not provide sufficient data for synthesis. Only full-text articles with adequate empirical or conceptual contributions were retained for analysis, in line with best practice for systematic literature reviews [16,25].

The applied criteria are summarised in Table 1, which illustrates how boundaries were set to enhance methodological rigour, comparability, and transparency.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.3. Screening and PRISMA Flow

A total of 15,605 records were identified through the Scopus database search covering the period from 2010 to 2025. After removing 1050 duplicate records using a combined automatic and manual de-duplication procedure, 5150 unique records remained for title and abstract screening. Title and abstract screening were conducted independently by two reviewers, and any disagreements were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached. This screening stage resulted in the exclusion of 4500 records that were not relevant to the specific focus of the review.

Following title and abstract screening, 650 records were retained for full-text assessment. All full-text articles were successfully retrieved and independently assessed for eligibility by two reviewers. During this stage, 640 records were excluded for the following reasons: being out of scope with the research objectives (n = 400), conference papers or non–peer-reviewed publications (n = 120), insufficient data or lack of relevant measures related to impulsive buying or post-purchase regret (n = 80), and duplicate records identified at the full-text stage (n = 40). As a result, a total of 10 studies met all inclusion criteria and were included in the final systematic review. The studies included in this review directly investigated the relationship between BNPL adoption and the incidence of impulsive buying and/or post-purchase regret. Figure 1 provides a representation of the systematic review selection process in the form of a PRISMA 2020 Flow Diagram. It presents the typical procedures for the screening of studies, in addition to enhancing the methodology’s transparency and reproducibility [16,35].

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

Systematic data extraction was conducted using a defined approach, based on the research questions and objectives of the current study. Two researchers independently used a structured coding tool to extract the following study attributes: Author(s), Year of Publication, Country/Context, Sample Characteristics, Theoretical Framework, Method Design, Measurement Constructs, Analytical Methods, Key Findings, and Stated Limitations. These are consistent with the guidelines for conducting systematic literature reviews [25].

To enhance reliability, the data were reviewed independently by two researchers, and any discrepancies between them were discussed and resolved, as is standard best practice for systematic reviews [16].

All of the extracted data were compiled into an evidence matrix table (Table 2), from which the themes were synthesised via thematic synthesis. Inductive clustering of the evidence revealed three recurring thematic domains: (i) Psychological Mechanisms (Impulsivity, Self-Control, Religiosity); (ii) Structural Determinants (Demographics, Financial Literacy); (iii) Ethical/Regulatory Dimensions (Responsible Consumption, Transparency, Sustainability). Thematic synthesis was able to provide both the interpretative depth and the comparative descriptive analysis that allows for an interpretation of the evidence base, similar to previous studies [27,36].

Table 2.

Summary of included studies (2018–2025).

2.5. Methodological Quality Appraisal

For assessing the robustness of the included studies, the ten-point CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme) Checklist (version 2020) has been utilised. CASP is commonly used to appraise the methodological quality of reviews within health care, psychology and social sciences [17]. The ten-point checklist has been applied to each of the included studies. It includes criteria such as clarity of aims, appropriateness of methodology, suitability of design, recruitment strategy, data collection procedures, analytical rigour, ethical considerations, clarity of findings, and overall contribution.

The CASP Checklist was chosen as the sole appraisal instrument, as the studies included in this review were primarily cross-sectional surveys with some conceptual integration. While both the AXIS tool for cross-sectional studies [42] and the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [43] could have potentially been applied to evaluate these studies, they were not designed to allow for consistent and comparable appraisal of all studies.

Two independent reviewers appraised the studies to increase reliability. A consensus was achieved on nine of the ten studies, with the remaining disagreement being resolved through discussion. Therefore, a 90 per cent agreement level was achieved by the reviewers, and a Cohen’s Kappa Coefficient of 0.81, indicating a high degree of agreement between reviewers [44]. The results of the CASP appraisal of the ten studies are reported in detail in Table 3, Section 3, which provides a comparative assessment of each of the ten studies included in this review.

Table 3.

CASP quality assessment of included studies (2018–2025).

2.6. Risk of Bias Assessment

The review of study-level bias and review-level bias focused upon assessing the sampling methodologies utilised in all included studies; the type of data collected; and a systematic assessment of the quality of the studies themselves, utilising the CASP Checklist. The majority of studies presented in this review used cross-sectional self-report surveys based on either students or convenience samples from digitally engaged countries, including Indonesia, India, Australia and Poland. As a result, both sampling techniques create an increased risk of selection bias and, therefore, limit the generalizability of the findings to larger populations of financially aware young adults who are active users of digital channels to purchase products. Also, due to the reliance on self-administered questionnaires, there are concerns related to common-method variance and social-desirability bias when assessing financially and morally sensitive constructs, such as debt, compulsive spending, and financial stress. While many of the studies presented herein indicated they used valid measures and/or advanced analytical techniques, only a few studies provided evidence that they directly addressed these biases with procedural remedies (e.g., temporal separation; anonymity assurances) or statistical diagnostics (e.g., Harman’s single factor test; marker variables).

Given that the review only considered sources listed in Scopus, which includes high-quality journals across many disciplines, the decision only to consider Scopus may have also created a database bias in that studies identified in other potential databases (i.e., Web of Science, PsycINFO, specialised finance/psychology databases) would be omitted. Furthermore, restricting the search to only peer-reviewed, English-language articles may have created language and publication bias in excluding practitioner reports, regulatory documents, and non-English academic literature addressing BNPL-related impulsivity and regret. Since the area of BNPL is still developing and has only been studied since 2018–2025, it is reasonable to assume that there are early-stage or null-result studies that remain unreported. These structural biases do not negate the findings of this review; however, they do indicate that caution should be taken when interpreting the findings and suggest that future reviews should include searches of multiple databases, languages and publication formats in order to provide a more comprehensive evidence base.

2.7. Transparency and Replicability

Throughout the review process, the detailed search strategy, PRISMA 2020 documentation and screening log [16] were thoroughly recorded in accordance with best-practice recommendations for systematic reviews. Although the protocol was defined before the start of the study (internally) rather than formally registered on platforms that support methodological accountability, such as the Open Science Framework (OSF) or PROSPERO [45], all Boolean searches (TITLE-ABS-KEY), database parameters and time frames (2010–2025) were fully documented. This level of documentation facilitates replication and aligns with established guidance for the transparent reporting of results in evidence syntheses [25].

A completed PRISMA 2020 checklist is provided in Appendix A. The extracted dataset (CSV and BibTeX formats) can be made available upon request. Together, these materials strengthen methodological transparency, replicability, and the credibility of the review’s findings through adherence to PRISMA and CASP standards.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Overview

There are 10 studies that have been published since 2018 to date, which met the inclusion criteria for this review and were therefore analysed within it. The field of study is relatively new and reflects the emerging area of scholarly inquiry into BNPL’s relationship to impulsive buying and post-purchase regret.

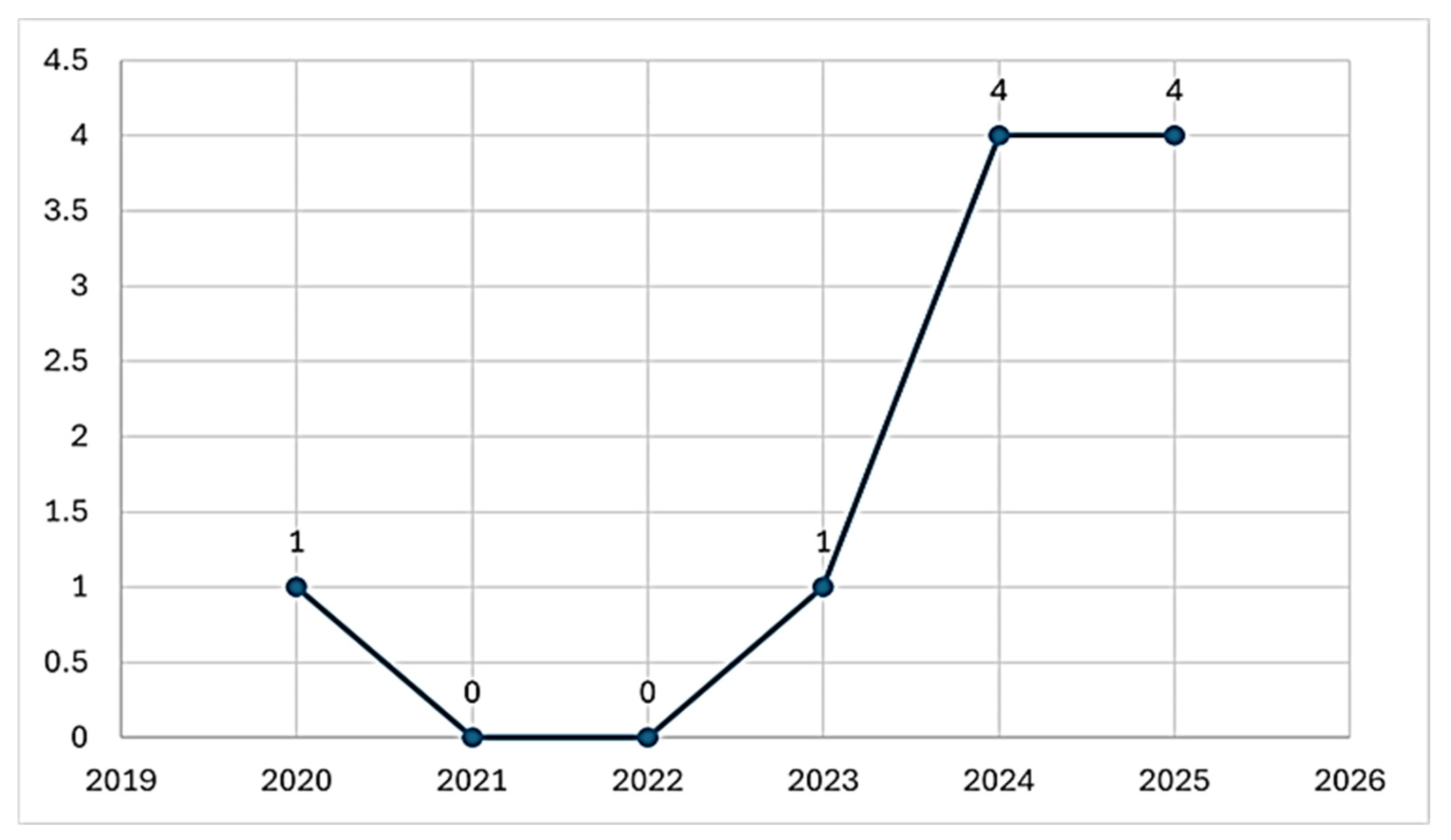

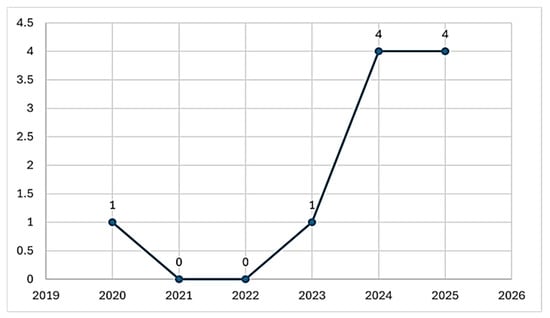

Figure 2 illustrates the temporal distribution of the reviewed studies. Studies published before 2020 were limited to two, as only one was published in 2020 and another in 2023. There were no relevant studies published in 2021 or 2022. These time gaps reflect the early stages of BNPL scholarship and likely the interruptions experienced by researchers worldwide due to the COVID-19 pandemic [46].

Figure 2.

Temporal distribution of included studies (2019–2026).

The number of studies published has increased sharply in 2024 and 2025, as four studies were published in each year. The rapid growth demonstrates the increasing use of BNPL around the world and the developing understanding among scholars of its behavioural and psychological implications [1,2]. The increase also highlights the relevance of this review to provide a comprehensive analysis of an emerging and highly diverse field of study.

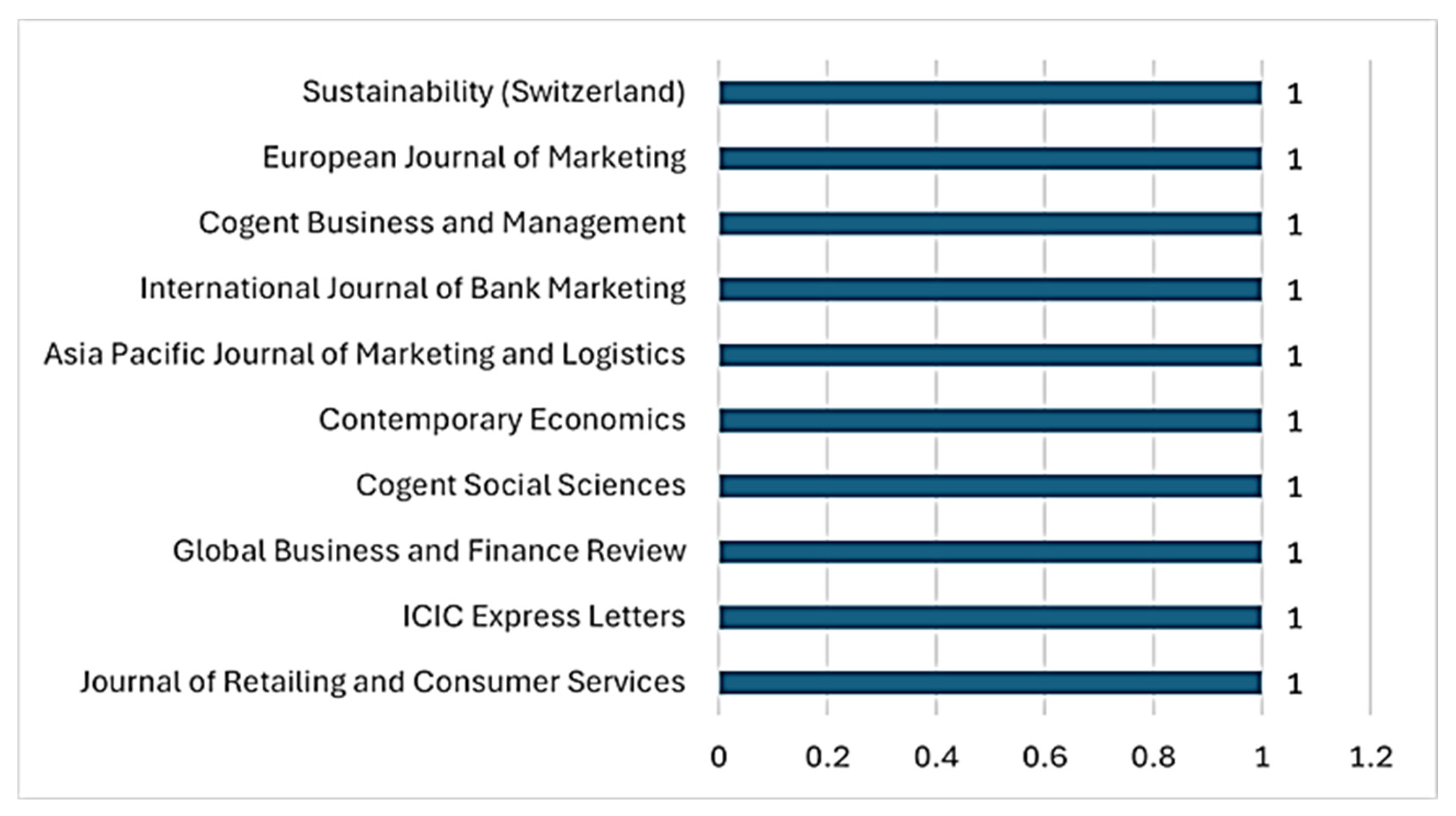

3.2. Publication Outlets

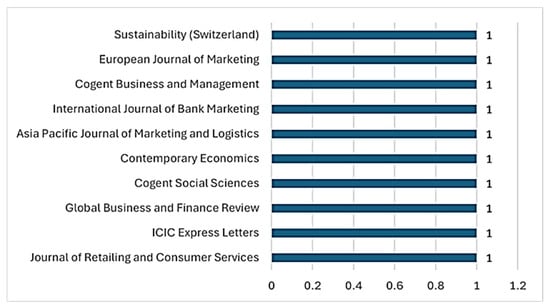

A wide range of journals were used as publication sources for this review of literature (see Figure 3), indicating that all studies reviewed appeared in separate journals. The use of several different journals represents a number of other disciplines, such as, but not limited to, consumer research, marketing, finance, and sustainability. Examples of these are: the Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, the Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, the International Journal of Bank Marketing, the European Journal of Marketing, and Sustainability (Switzerland).

Figure 3.

Publication outlets of included studies (2018–2025).

The diversity of journals suggests that the BNPL research area is in its exploratory stage and therefore has no one journal that dominates the discussion around it, as is typical of emerging and developing areas of research [25]. The diversity of disciplines represented by the journals also suggests that BNPL is relevant to many different places, including consumer behaviour, marketing strategies, financial well-being, and sustainable consumption [27].

It should be noted that many of the journals listed represent high-level journals, suggesting that the BNPL research area is gaining increasing levels of academic legitimacy within those top-tier academic domains, which is consistent with Podsakoff et al. [47] who demonstrated that publication in leading journals is often seen as a sign of the maturity and acceptance of a new or emerging area of academic research.

3.3. Characteristics of Included Studies

The ten studies in this systematic review are summarised in Table 2 in terms of the authors, geographic locations, conceptual models, methodologies used, and conclusions drawn. The majority of research studies were located in Asia, especially India and Indonesia, where there has been significant growth in both fintech adoption and Buy Now, Pay Later (BNPL) usage. Studies were also conducted in more-developed countries like Australia, New Zealand, Germany, and Poland, which allows researchers to make comparisons between developing and more developed financial systems.

Methodologically, the majority of studies surveyed customers using cross-sectional survey designs that analysed customer responses with Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) analysis. PLS-SEM is currently the dominant methodology in BNPL behavioural research [48,49]. However, alternative methods, including some form of mixed-methods research and exploratory modelling (for example, DEMATEL and regression-based frameworks), were employed but very infrequently. The dominance of PLS-SEM research demonstrates the heavy reliance on self-reporting from customers in BNPL research and the potential for future research to explore the value of longitudinal or experimental study designs.

Theoretically, Impulsive Buying Theory (IBT), Cognitive Dissonance Theory (CDT), and Behavioural Finance were the three primary theories applied in BNPL research. The additional theoretical frameworks applied include Materialism, Self-Control/Mindfulness, and Social Comparison Theory [50]. These theoretical perspectives identify many of the psychological and behavioural factors that influence BNPL usage.

There was no commonality in terms of how the studies examined post-purchase regret as an element of the constructs modelled in the studies In addition to examining impulsive behaviour, financial awareness, and well-being, all of the studies in the review addressed post-purchase consequences that are closely related to regret, such as economic stress, compulsive buying, and reduced well-being, rather than regret itself as a directly operationalised construct. Regret, although it may be the most critical post-purchase consequence of BNPL, has been significantly underexamined [8]. Therefore, the review identifies a gap in the existing literature regarding the relationship between BNPL usage and regret and provides the opportunity to examine BNPL usage in the broader behavioural and ethical context.

3.4. Results of Quality Appraisal

The CASP assessment (Table 3) revealed that most studies demonstrated high methodological rigour, particularly in terms of clearly stated aims, valid measures, and the use of advanced analytical techniques. Studies employing structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) and exploratory causal methods (e.g., DEMATEL) scored highest on analytical robustness [17].

Nevertheless, several common limitations were observed. First, a substantial number of studies relied on student-based or convenience samples, which restricts generalisability to broader consumer populations [51]. Second, the heavy reliance on cross-sectional survey designs limits the ability to draw causal inferences regarding BNPL use, impulsivity, and post-purchase regret [52]. Third, although impulsivity and financial well-being were frequently measured, the absence of direct operationalisation of post-purchase regret was a recurrent gap, leaving one of the most critical consumer outcomes underexplored [8].

Despite these limitations, the overall quality of the included studies was judged to be medium-to-high to high, ensuring that the synthesis rests on a solid empirical and conceptual foundation. Table 3 presents a comparative overview of the CASP evaluation, demonstrating the strengths and weaknesses of each study.

3.5. Thematic Synthesis

These ten studies provided a basis for synthesising the primary themes that represent how BNPL use relates to impulse buying and regret. Three major themes that are representative of how BNPL influences impulse buying and subsequent regret-related outcomes can be derived from the data.

3.5.1. Theme 1: BNPL Enables Impulsivity

BNPL was found to enable impulse buying in nearly every study examined. The means by which BNPL enabled impulse buying were through instalment plans, providing a sense of urgency, and creating a false perception of affordability. By removing the saliency of payment immediately after purchase, these mechanisms reduce cognitive barriers to impulsive decision making and create a predisposition toward purchasing based on emotions rather than planned actions, particularly with younger and less financially sophisticated individuals [5,53].

3.5.2. Theme 2: Post-Purchase Regret and Financial Stress

Post-purchase regret was infrequently assessed directly within the context of the studies reviewed here; however, indirect indicators of post-purchase regret were evident in the forms of increased financial stress, compulsive buying, dissatisfaction, and decreased overall well-being. Therefore, it appears that when BNPL encourages impulse buying, it also leads to regret-related consequences, thereby supporting the theoretical relationships between instant gratification and long-term cognitive dissonance [8]. None of the ten studies examined in this review directly measured regret. All studies examined here indirectly measured regret using proxy measures of stress, dissatisfaction, and/or overall well-being.

3.5.3. Theme 3: Moderators and Protective Factors

A number of the studies reviewed here indicated various contextual moderator variables that influenced the outcome of BNPL use. These include financial awareness, religiosity, mindfulness, and cultural values. These moderating variables have been found to moderate impulsivity and mitigate adverse economic outcomes associated with BNPL use, providing avenues for consumer education, ethical marketing practices, and regulatory intervention [54,55]. Furthermore, these moderator variables illustrate that the effect of BNPL use is not consistent across all users but varies based on psychological and sociocultural contexts.

3.6. Summary of Findings

The existing body of evidence for BNPL, impulsive purchasing behaviour, and post-purchase regret is still developing; however, it has experienced a considerable increase in interest by researchers since 2023.

There is consistent evidence of BNPL contributing to impulsive consumption via instalment framing, urgency cues, and perceived affordability. Although there is limited empirical evidence that directly addresses post-purchase regret, most studies have addressed this topic through indirect means, including constructs such as financial stress, decreased well-being, and compulsive purchasing behaviour [8].

A significant gap exists within the extant literature regarding post-purchase regret, as it is likely the most salient behavioural and emotional outcome of BNPL usage. In order to address this void, future research should utilise longitudinal, experimental, and cross-cultural methodologies to develop a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms associated with post-purchase regret. Furthermore, the inclusion of additional theoretical frameworks that are multidisciplinary in nature (i.e., encompassing both behavioural and ethical/financial domains) will be crucial to provide a more holistic understanding of the consumer and social implications of BNPL [52].

It should be noted that many of the studies that were included in this review did not measure post-purchase regret as a separate psychological construct by means of validated regret measures. Rather, the studies used various other indicators (e.g., financial stress, emotional discomfort, perceived financial burden, lower subjective well-being) as indirect measures for regret. Although the measures described above are conceptually different than regret, there is substantial research showing that regret is often accompanied by additional negative affect experienced after the initial decision, and that it is negatively correlated with well-being outcomes [23,56,57]. Further, there is also ample evidence indicating that financial stress and financial difficulties (i.e., financial difficulty resulting from debt) have significant effects on both well-being and how individuals make financial decisions, therefore they could represent possible downstream consequences that may occur if an individual experiences regret after their consumption or financial decision-making process [56,58].

4. Discussion

Triangulating thematic synthesis (descriptive trends), quality appraisal, and ten studies from peer-reviewed literature published between 2018 and 2025 provides empirical evidence that while research on BNPL related to impulsive buying and post-purchase regret is expanding quickly, it remains largely in its early stages of development.

4.1. Theoretical Positioning

Placed at the intersection of Consumer Psychology and Behavioural Finance, the review has extended previous theory to show BNPL purchasing is both financially based and psychologically influenced through digital nudges and cognitive biases. Although Impulsive Buying Theory explained the affective nature of BNPL purchasing, Cognitive Dissonance Theory explained why regret and negative post-purchase emotions arise from repayment commitments. The review therefore placed BNPL into the distinct consumption environment, which increases the emotional conflict between consumers’ cognitive control and the instalment framing and affordability illusions used to influence their purchasing decisions. In establishing this theoretical placement, the review established an enhanced analytical basis for examining regret as a significant yet unrecognised consumer outcome.

4.2. Evolution of Research Activity

The time pattern clearly shows how new the research trend is here. The first studies appeared sporadically between 2020 and 2022, followed by substantial growth in 2024 and 2025, which reflects both the rapid diffusion of BNPL services in retail markets and the growing interest of academics and regulators in their implications [41,59]. Reports like the UK Woolard Review [60], the OECD [1], and the BIS [2] are significant contributions to this surge of interest and, therefore, create an environment that can attract more scholarly work. This surge indicates the timeliness of integrating the evidence into a coherent body and signals that the theoretical and methodological foundation of the area remains underdeveloped in this area of rapid expansion [2,27].

4.3. Interdisciplinary but Fragmented Landscape

The reviewed research was published across a wide variety of academic journals in several disciplines, including marketing, finance, psychology, and multidisciplinary fields, as an illustration of how BNPL is relevant to multiple disciplines but also as a reflection of a fractured body of knowledge without a single discipline or field being identified as the primary discipline. Fragmentation of similar sorts has been reported in digital finance areas such as mobile payment systems [27,61], which indicates that BNPL research will require more integration of theory and more cohesiveness in research agendas. This review provides one of the first steps toward reducing the dispersion mentioned above and combining evidence from all of these different areas so that a unifying body of BNPL research can emerge [62].

4.4. Theoretical Insights

There are three major intellectual currents. First, these mechanisms in BNPL, like instalment framing, urgency cues, and affordability illusions, serve as a behavioural nudge that reduces the psychological barrier for consumption, therefore extending Impulsive Buying Theory (IBT) as well as indicating how digital payment systems increase impulsivity [7,63,64].

Second, the indirect indicators of the post-purchase regret are aligned with Cognitive Dissonance Theory (CDT) as they have been indicated to have an adverse effect from the conflict between short-term satisfaction from using the product and repayment obligation [65,66]; however, post-purchase regret has seldom been assessed in studies or operationalized as a valid construct, which is a serious conceptual gap.

Third, some variables moderate the behavior of users, like financial awareness, religiosity, and mindfulness, which suggest the possibility of integrating behavioral finance and consumer ethics perspectives on this topic and expanding the current theoretical frameworks with cultural and psychological buffers [54,55,67,68].

4.4.1. Why Post-Purchase Regret Has Not Been Directly Measured in BNPL Research

Although the potential impact of post-purchase regret in consumer decision-making is theoretically essential, none of the ten studies in this review directly operationalised post-purchase regret as a validated construct. Instead, researchers relied on proxy indicators, such as financial stress, compulsive buying behaviour, and reduced well-being, to infer regret-related experiences. This absence of direct measurement indicates a significant methodological and conceptual gap between BNPL research and the broader literature on post-purchase regret. First, most studies have been focused on the adoption of BNPL, with few examining the drivers of adoption (e.g., perceived risk, indebtedness, materialism, convenience), and none have examined the emotional responses consumers experience subsequent to purchasing using BNPL. Second, the instruments used by researchers to measure BNPL have not included valid measures of regret; therefore, researchers are forced to use proxy variables for regret, such as financial stress, compulsive buying behaviour, or reduced well-being. Third, the fact that many studies of BNPL have employed cross-sectional designs and have relied upon students as subjects limits the ability of these studies to capture regret, since regret typically develops over time, only after the consumer has completed their payment cycle. Fourth, because the growth of BNPL was so rapid (2020–2025), research on BNPL has tended to focus almost exclusively on the issues related to the adoption of BNPL (and the risks associated with it) and has paid little attention to the psychological aftermath of purchasing using BNPL, making it empirically underdeveloped.

Therefore, the absence of measures of regret does not indicate that regret is irrelevant to the study of BNPL but instead represents a significant methodological blind spot. Future studies of BNPL should include valid measures of regret, employ longitudinal or experimental designs, and conceptualise regret as an independent emotional response, as opposed to being a derivative of dissatisfaction or financial strain. Addressing this research gap will be necessary to build a complete understanding of the psychological implications of BNPL.

Accordingly, in the present review, such variables are interpreted as indirect manifestations of post-purchase regret rather than as direct measurements of the construct itself, and this distinction is maintained to avoid conceptual ambiguity when synthesizing findings across heterogeneous operationalizations.

4.4.2. Methodological Synthesis Across Included Studies

The synthesis identifies some consistent patterns across methods used in the 10 studies reviewed, including strengths and weaknesses of the extant literature. The studies are primarily based upon a quantitative cross-sectional survey design, and seven of those studies utilised PLS-SEM as their primary analysis tool. Although the high level of similarity among the methods used can provide a comparable way to test models and measure latent constructs, the dominant usage of the same analytical technique limits causal inference. It makes it challenging to capture psychological phenomena that evolve, such as post-purchase regret.

Only one of the studies employed a causal modelling methodology (DEMATEL) or a mixed-methods approach (vignettes), and these represent exceptions to the predominantly correlational nature of the existing body of research.

The sampling frame is similar in breadth to the methodologies used to collect data, and a majority of the studies sampled students or used convenience samples comprising digitally active youth in India, Indonesia, Australia, and Poland. Utilising student or convenience samples maximises internal validity of the results; however, it limits the generalizability of the findings to other youth outside of digitally active youth, particularly due to differences in culture, economics, and regulations related to BNPL in different markets around the world.

In addition, the widespread use of self-administered online questionnaires may create an increased risk of social desirability bias and standard method variance (CMV). Furthermore, while CMV is often addressed statistically and/or procedurally in many studies, none of the studies reviewed by this synthesis did so.

The measurement of various constructs (impulsive buying, financial stress, materialism, and consumerism) was consistent in its use of validated scales. No study, however, used validated measurements of post-purchase regret. Instead, each study inferred regret through constructs that occur after the decision to buy, i.e., reduced well-being, compulsive buying behaviour, or subjective indicators of financial distress.

The omission of validated regret measurements represents a methodological gap in BNPL research design. Specifically, because impulse purchases and emotional responses to those purchases typically occur at different points in time, the cross-sectional survey design is incapable of capturing the timing of when these two events occurred.

Collectively, the synthesis of the above-described studies indicates that although there is substantial analytical sophistication in the BNPL field, the methodological approach of the studies reviewed is narrow. Therefore, future studies would be enhanced by employing longitudinal designs, experimental designs, and mixed-methods designs, expanding sample frames to include a broader range of youth than those who are digitally engaged, and utilizing validated measures of regret to improve the understanding of the psychological effects of BNPL-driven impulsivity.

4.4.3. Proposed Conceptual Framework

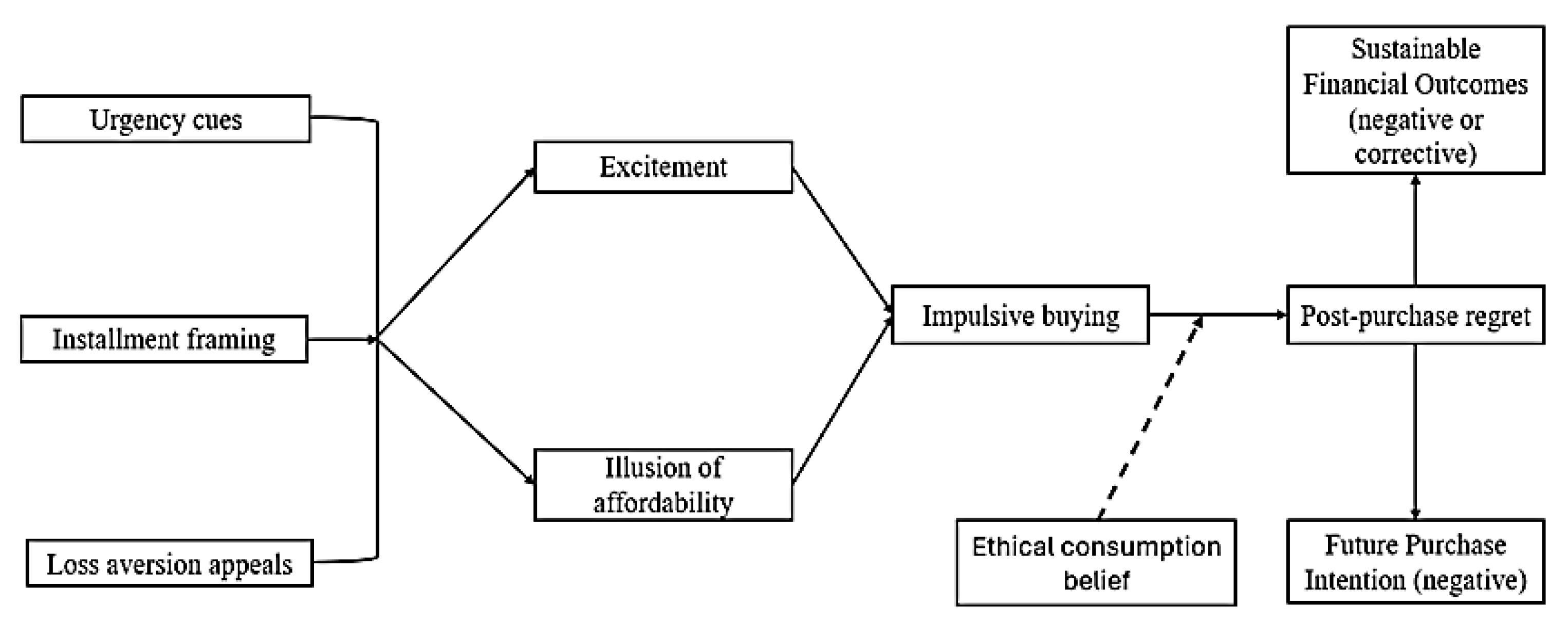

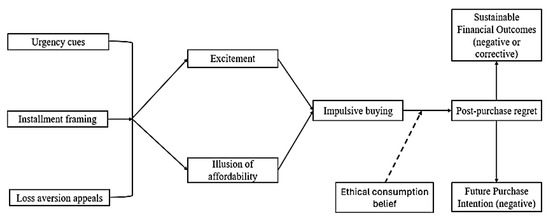

Building upon previously established theories of psychology and consumer behaviour, the proposed conceptual framework outlines how BNPL marketing strategies generate cognitive processing, emotional response, impulsive behaviour, and ultimately post-purchase regret. The Affective Mechanism is based on the dual-process model of decision-making [69] that differentiates fast, emotionally based decision-making from slow, rational decision-making. Cues used in BNPL marketing strategies, such as urgency messages, loss aversion appeals, and so forth, elicit positive emotional responses, thereby decreasing the amount of time and energy available for consumers to evaluate options reflectively and increasing the likelihood that they will make an impulse purchase. The Cognitive Pathway is based on [64] Cognitive Dissonance Theory. When consumers act in ways that do not match their values, they experience psychological discomfort, which leads to dissonance. BNPL marketing strategies utilise cues specific to BNPL marketing, such as instalment framing and affordability illusions that decrease consumers’ use of cognitive control, create distorted mental images of costs and risks associated with purchasing, and subsequently lead to impulse purchases that are the precursors to dissonance-generated regret.

The theoretical integration of BNPL marketing mechanisms, impulsive buying behavior, and post-purchase regret, as illustrated in Figure 4, represents a theory-based, integrated conceptual framework versus an empirically supported, causal relationship model. This integrated conceptual framework was established by synthesizing both empirical and conceptual work related to BNPL marketing mechanisms and impulsive buying behavior from a large number of studies identified via a systematic review using the PRISMA methodology. The primary function of this framework is to organize, synthesize, and conceptually explain how BNPL marketing mechanisms are associated with impulsive buying behavior and subsequently with post-purchase regret.

Figure 4.

Conceptual framework.

Unlike empirically derived models, such as the TAM, which utilize statistical hypothesis testing to establish evidence for the existence of causal relationships among variables, the current framework does not provide empirical evidence for causal relationships among the variables. Rather, it identifies recurring patterns, mechanisms, and gaps in the literature. Therefore, the framework should be viewed as a theory-integrating model to guide future empirical research, especially longitudinal and experimental designs that may investigate the relationships proposed within the framework.

The moderating effect of Ethical Consumption Belief, as outlined in the framework, relates to the theory of Moral Self-Regulation and Value-Congruence [70]. Consumers who believe in ethical consumption are more likely to evaluate their purchasing decisions through a moral lens. Therefore, they are more likely to experience greater levels of regret if their impulsively or unsustainably purchased products contradict their personal ethical values. On the other hand, those consumers with lower ethical orientations may be less likely to experience these emotions. Overall, the integration of these theories into the proposed conceptual framework provides support for the structure of the framework and provides insight into the manner in which BNPL marketing strategies can initiate both emotional and cognitive processes that influence consumers to make impulse purchases and experience post-purchase regret, while also influencing long-term behaviours such as future purchase intentions and sustainable financial well-being.

The conceptual model for the study proposes that Impulsive Buying Theory and Cognitive Dissonance Theory are complementary frameworks to understand the factors leading to BNPL use and its effects. Impulsive Buying Theory is used to describe how BNPL’s characteristics, like deferred payment plans and installment-based pricing, reduce the immediate financial burden of a purchase and make consumers more likely to spend impulsively [5,71,72,73]. This also occurs when consumers see their purchases divided into multiple payments, which reduces how aware they are of the total price they will pay, and makes it easier for them to ignore the financial burden of the purchase and act on impulse [74].

In addition to the ways BNPL prices influence consumer spending habits, other marketing tools, such as creating the impression of urgency, can motivate consumers to buy sooner or make quicker decisions to buy online [75] and create the conditions for consumers to engage in impulsive purchasing.

The methodology for developing the proposed framework utilized an organized synthesis process. The first step involved identifying repeated or common marketing mechanisms related to BNPL found throughout the reviewed research (i.e., installment framing, urgency cues, and affordability illusions). Second, the most common psychological responses (i.e., impulsive buying and post-purchase emotions), as previously discussed, were grouped by their theoretical consistency with Impulsive Buying Theory and Cognitive Dissonance Theory [76]. Third, indirect indicators of regret (i.e., financial stress, decreased well-being, and compulsive purchasing) were conceptualized as downstream manifestations of post-purchase regret because no validated measures of regret existed in the literature reviewed.

Thus, this systematic synthesis-based methodology assured that the framework was developed through consistent theoretical patterns and empirically observable patterns across the reviewed research and acknowledged the existing methodological constraints of the field.

Once the consumer has made an impulsive purchase using BNPL, Cognitive Dissonance Theory describes the potential psychological response that follows. For example, once a consumer has purchased something with BNPL, the consumer may realize that they did not get what they expected from their purchase, and therefore, they feel uncomfortable, blame themselves, or regret their decision [8,21,64,66].

As supported by previous studies, impulsive purchases are followed by regret over the purchase and/or bad emotions [77]. The conceptual model integrates the two theories to capture both the conditions that lead to impulsive purchasing and the long-term psychological consequences of the purchase [77,78]. Table 4 shows Key Constructs and Conceptual Definitions in BNPL Research.

Table 4.

Key Constructs and Conceptual Definitions in BNPL Research.

4.5. Methodological Strengths and Weaknesses

CASP Assessment shows the majority of research conducted has used strong statistical methods, especially by the use of PLS-SEM or DEMATEL, with a validated scale [49]. However, there are four significant limitations to the body of research as follows: (i) the large amount of cross-sectional survey-based research, which limits the ability to infer causality [96]; (ii) the large number of students and convenience samples, which limit the generalizability of the results [51]; (iii) the limited geographical scope, primarily limited to Asian and European countries, and therefore may not be representative of the global variability of BNPL [14,97]; (iv) the lack of direct measurement of regret in this body of research, with researchers using dissatisfaction, compulsive buying, or financial stress as proxies for regret [98]. The reliance on self-reported surveys also increases the risk of common-method bias [99]. These limitations represent the developmental stage of the research and indicate that the research is still developing towards establishing a standardised methodology.

4.6. Practical and Policy Implications

The results exemplify that BNPL has a dual-sided nature. The use of instalment framing and the impact of urgency cues will have the immediate effect of increasing short-term sales. However, it can also have the unintended consequence of damaging consumer trust by causing customers to experience regret-related outcomes [98]. Therefore, for marketers who are interested in using BNPL responsibly, transparency is key. Marketing practices must be responsible and affordable, and campaigns need to be balanced between promotional efforts [10]. For regulators, there is a need for regulations to identify behavioural biases like loss aversion and affordability illusion, and there is a need to promote financial literacy programs specifically for young consumers [60,100]. As for international guidelines and standards, such as the UN Principles for Responsible Digital Lending and the OECD recommendations for consumer protection, these represent the appropriate frameworks to support the development of responsible regulations for BNPL [1,101].

Overall, the literature reflects BNPL as an enabler of digital consumption, but it is also a source of financial vulnerability. The current body of research has made significant contributions to the advancement of theoretical knowledge by relating impulsivity and regret. The body of research regarding BNPL is still relatively limited and conceptually and methodologically restricted. In order to advance the body of research regarding BNPL, there needs to be better theoretical integration of the disciplines of consumer behaviour, behavioural finance, and ethics, and there also needs to be greater methodological innovation with regard to longitudinal and experimental studies. It is also critical to extend the scope of study regarding the cultural and regulatory diversity of the contexts of BNPL to fully understand all of the behavioural and social consequences of BNPL. Therefore, this literature review provides an essential contribution to the consolidation of isolated pieces of research and the identification of the following steps for research, practice, and policy.

5. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Although this review’s methodology has been rigorously applied, the review is subject to some key limitations that need to be carefully considered. The first limitation is the fact that this review relied solely upon Scopus for database search, which, as an exhaustive database, may have omitted relevant studies indexed in databases such as Web of Science, PsycINFO or ABI/INFORM. Future systematic reviews could benefit from using multiple databases to increase the breadth of studies searched and thus decrease selection bias. The second limitation is the restriction of searching to only peer-reviewed publications written in English, which may represent a form of publication bias that favours formal, Western-centric academic publication at the expense of potentially valuable insight from grey literature, or those published in languages other than English. The third limitation relates to the fact that the synthesis was completed using a relatively small number of studies (n = 10), which reflects the developing nature of BNPL research, and therefore, conclusions derived from this study should be interpreted cautiously. The fourth limitation is that all studies identified in this review used cross-sectional surveys as their design methodology, which restricts the ability to infer causality between variables and obscures how regret evolves. The fifth limitation is that the use of indirect measures of post-purchase regret also indicates that one of the most significant psychological consequences of BNPL consumption is still poorly researched.

Additionally, given the reliance upon self-report survey designs to collect data in this review, there are several reasons why potential standard method biases could exist. Future research should endeavour to incorporate procedural and statistical remedies (such as Harman’s Single-Factor Test or Marker Variables) to mitigate bias. Additionally, although CASP was applied uniformly throughout this review, it would be beneficial for future reviews to employ additional assessment tools (for example, AXIS or MMAT) to increase the robustness of quality assessments and provide greater comparability amongst them.

The data in many of these studies were collected using samples of college students or by convenience sampling. These samples, although common in behavioral and consumer research due to their availability and practicality, are often non-probability samples and do not provide an adequate representation of the diverse demographics, socio-economic statuses, and cultures that influence how consumers make decisions in the world outside of academic research settings [51,102]. The literature has also shown that there is considerable variability in the results obtained using samples of college students across different cohorts of students, and as such have raised issues with respect to both the robustness of the findings as well as the potential to extend the conclusions of the studies to larger populations [103]. As such, it has been reported that there are considerable differences in the results that are obtained using samples of students versus those of non-students, and that the composition of the sample can significantly impact the inferences made as well as the external validity of the research [104,105]. Therefore, the associations found between BNPL usage, impulsive purchasing behaviors, and post-purchase regret should be viewed with a high degree of caution when attempting to generalize the findings of the current studies to other populations than the ones studied [102,106]. Future research would be improved through the use of more diverse samples (i.e., cross-cultural, age-diverse, and socio-economically diverse) and through additional recruitment methods that increase the breadth of the populations represented in future research [107].

Another general limitation that was observed throughout the literature review is that most studies have relied upon cross-sectional research methods; as such, it has been difficult for researchers to assess the dynamic and changing nature of consumers’ post-purchase emotional and cognitive responses due to the nature of cross-sectional methods. While a cross-sectional design can be an excellent method to identify relationships between BNPL and the outcomes experienced by consumers using the service, this design type has limitations in assessing how temporal ordering occurs and also limits the ability to establish strong evidence for causality in the process when the process of interest takes place over time [51,106].

Ultimately, future research should expand its methodological and contextual scope to: (i) extend beyond English language, academic publications and to include grey literature from diverse international contexts; (ii) utilise longitudinal, experimental and/or mixed-method designs to improve causal inference; (iii) investigate cross-cultural contexts and under researched regions including the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America; (iv) measure post-purchase regret as a validated concept directly rather than indirectly; (v) incorporate ethics, sustainability and consumer wellbeing into research on the long-term societal impacts of adopting BNPL. By addressing the limitations identified in this review, future research can progress towards a more comprehensive, interdisciplinary, and ethically grounded understanding of the role of BNPL in influencing consumer behaviour.

Future Research Directions

A better understanding of the methodology, conceptually and contextually, of BNPL and its relationship to impulse purchasing and post-purchase regret can be achieved through future research focusing on the gaps identified in this study. There are three specific avenues to pursue to advance BNPL research further.

Firstly, researchers need to employ broader methodologies than cross-sectional surveys and use both longitudinal and experimental designs to capture the temporal changes in an individual’s emotional responses. This is particularly relevant because post-purchase regret typically develops after the first payment cycle of a BNPL loan has been completed. Longitudinal studies will help to identify how the impulsive BNPL purchases develop into cognitive dissonance, stress, or regret over time. Experimental studies employing manipulations of instalment framing, urgency cues, or affordability illusions will help to strengthen the causal linkages between impulsive behaviour and BNPL environments.

Secondly, there is currently no evidence of validated measures of regret in the BNPL literature that researchers can apply to their studies. Therefore, the development of standardised instruments to measure regret in BNPL settings is required. Researchers should either utilise established regret scales and adapt them to measure regret in BNPL settings or develop new BNPL-specific measures of regret that can differentiate between immediate dissatisfaction, financial pressure, and genuine post-purchase regret. The application of valid measures of regret will enable researchers to progress from using proxy measures of regret (e.g., decreased well-being and compulsive buying) and facilitate more accurate theoretical testing of the constructs of IBT and CDT in BNPL settings.

Thirdly, the current sampling strategies used by researchers are limited. Most current studies have focused on young, digitally active, and predominantly middle-class populations in SE Asia, India, Australia, and certain regions in Europe. In order to understand the global variability in the psychological effects of BNPL, it is essential to include samples from diverse cross-cultural, socio-economic, and underrepresented markets, including but not limited to the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America. These different marketplaces vary significantly in terms of financial education, religious values, government regulations protecting consumers, and debt culture; therefore, they are critical for understanding the variation in the psychological impacts of BNPL across cultures. Comparative cross-cultural studies could identify how cultural values, religiosity, financial knowledge, or social norms influence the level of impulsiveness and regret experienced by consumers.

Fourthly, researchers should consider incorporating a more integrated theoretical framework when conducting BNPL studies. The majority of existing studies rely on IBT, CDT or Behavioural Finance theory; however, integrating these theories with ethical consumption, mindfulness, or digital nudging frameworks could produce a more comprehensive understanding of how consumers process BNPL cues and modulate the emotional consequences of BNPL decisions. In addition, researchers could explore moderators such as self-control, financial awareness, and ethical consumption beliefs to explain why some consumers report significant levels of regret, whereas other consumers do not.

Lastly, industry and policy provide opportunities for BNPL research through an interdisciplinary approach. Future research should assess whether consumer protection regulations, transparency requirements, and responsible marketing policies and procedures reduce the levels of impulsiveness and regret reported by consumers. Furthermore, research examining how the algorithmic design of apps, user interfaces, AI-based nudges, and repayment reminders affects consumers’ purchasing behaviours could create meaningful implications for policymakers and Fintech developers.

The results of this study, due to a relatively low number of studies included within this review, should be viewed appropriately and not as indicating conclusions or generalizations, but rather indicate developing trends and emerging patterns that require additional research utilizing both longitudinal and experimental methodologies.

6. Implications

6.1. Theoretical Implications

The findings of this study provide an integrated theory for the use of BNPL through the combination of existing theories from consumer behaviour, psychology, and finance. This review expands upon the impulse buying theory (IBT) regarding how BNPL digital payment formats, i.e., instalments and urgency cues, can be used as behavioural nudge mechanisms to increase impulse purchases [59,107]. Additionally, the findings support cognitive dissonance theory (CDT) in that consumers are likely to feel regretful or have “bad feelings” when their repayment responsibilities for the BNPL loan contradict the instant gratification they experience from making a purchase [8,15].

Finally, this study identifies moderators of BNPL use, including financial consciousness, mindfulness, and religiosity, which will allow researchers to broaden the scope of explanations of behavioural finance [14,38]. These moderators provide a basis for further BNPL research to expand beyond simple usage/adoption models into a multidisciplinary framework that includes psychological, cultural, and ethical influences on purchasing decisions [97].

6.2. Managerial Implications

For the practitioner, BNPL is a two-edged sword. In terms of converting customers, BNPL will be effective at reducing the burden of payments and increasing sales growth for the retailer. However, if BNPL is based solely on impulse (and the consumer cannot repay), then this could lead to the development of dissatisfaction with the purchase, post-purchase regrets, and/or financial distress. These issues could ultimately damage long-term loyalty and brand equity.

Retailers and Fintech providers should implement clear and transparent communications regarding repayment requirements and potential risks associated with BNPL, assess the affordability of BNPL to protect financially sensitive consumers, and create marketing promotions that focus on developing sustainable customer relationships rather than maximising short-term sales. The integration of accountability within the marketing of BNPL will enable companies to mitigate the negative consequences of BNPL, increase consumer confidence, and allow them to differentiate their company in an ever-increasing competitive environment of digital finance.

6.3. Policy Implications

The results indicate that from a regulatory perspective, there is a need for behaviorally informed policy which addresses the cognitive biases influencing the adoption of BNPL with specific regard to its features (e.g., installment framing, urgency cues, loss aversion appeals) in addition to traditional disclosure based approaches which may fail to account for how consumers tend to underestimate or discount future cost(s).

Therefore, policymakers should enhance affordability checks on BNPL products and require BNPL providers to conduct transparent risk assessment(s). Policymakers should also implement requirements for BNPL providers to provide transparent and standardised formats for disclosures, to reduce information asymmetry, and implement financial literacy programs directed towards the youth population, who are the primary demographic influenced by BNPL-induced impulse purchasing behaviours.

As such, by integrating behavioural science into existing consumer protection policy, policymakers will be able to find an appropriate level of regulation of financial innovation and responsibility, so that BNPL can contribute positively to financial inclusion and not negatively influence debt cycle(s), nor negatively affect consumers.

The results of this literature review have important implications for regulators, policymakers, and practitioners in the industry who are concerned with ensuring that BNPL is used ethically. Regulatory authorities should take into account the observed relationship between BNPL attributes and the increase in impulsive buying behaviors, and as such, can require clearer disclosure from BNPL providers, require cooling-off periods, and enhance consumer protection mechanisms to minimize potential harm.

7. Conclusions

The research in this paper provides an overview of all of the previous work done in relation to whether or not there is a link between using Buy Now, Pay Later (BNPL) products and impulsive buying and/or feeling sorry about purchases made after they are completed.

Through gathering data from all of the research articles written since 2018 through 2025, the authors show that because BNPL has become so popular and used by so many people it has changed the way people shop and created new ways of shopping, as well as creating new behaviors and ethical issues in today’s digital marketplace.

Furthermore, while research indicates that post-purchase regret is a common result of BNPL use, very little research has measured post-purchase regret directly. Therefore, most of the time, researchers have used indirect measures of post-purchase regret, including financial stress, a decrease in overall well-being, and compulsive spending behavior.

While these indirect measures can help understand the results of BNPL use, they also show that there are conceptual and methodological gaps in the body of literature surrounding BNPL use. To address this gap in the literature, the direct measurement of post-purchase regret will have to be addressed, as well as the consistent use of valid measurement tools.

This research contributes to the theory area by combining the Impulsive Buying Theory and the Cognitive Dissonance Theory to explain the antecedents and post-usage dynamics of BNPL use.

By conceptualizing impulsive purchase decisions as behavioral triggers and post-purchase regret as an evaluative response to those behavioral triggers, the proposed framework provides a cohesive explanation for how BNPL features affect consumers’ decision-making processes and emotional experiences. In addition to contributing to the body of knowledge by extending current theoretical models, the proposed framework links pre-purchase motivations to post-purchase psychological effects, thereby providing a unique contribution to the field.

Additionally, the review demonstrates the overwhelming prevalence of cross-sectional research designs and convenience samples within the existing body of literature, which limits the potential to measure the temporal progression of regret and to establish causal relationships. Therefore, future research would greatly benefit from using longitudinal, experimental, and mixed-methods research approaches to provide a stronger foundation for establishing causality, and by increasing the diversity of the participants included in research to increase the external validity of the findings.

Accordingly, the conceptual framework proposed in this review should be understood as an integrative theoretical contribution derived from systematic evidence synthesis, rather than a statistically validated causal model.

Finally, the findings from this research indicate that there needs to be a better, more transparent design of BNPL services and that clearer guidelines should be established for the industry. Some of the changes that could potentially occur include clear disclosure practices, clearer repayment obligation disclosures, and the inclusion of behavioral safeguards (i.e., cooling-off period) that can assist in reducing the likelihood of impulsive purchasing decisions and reducing consumer harm. Overall, this research adds to the conversation regarding the ethics of digital finance by explaining the psychological factors involved in the use of BNPL services and identifying areas for future research to create more sustainable and consumer-focused digital finance systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.M.N. and C.A.C.W.; methodology, O.M.N. and S.N.A.H.; validation, C.A.C.W., L.A.-Z. and A.S.A.-A.; formal analysis, O.M.N.; data curation, O.M.N. and S.N.A.H.; writing—original draft preparation, O.M.N.; writing—review and editing, C.A.C.W., S.N.A.H., L.A.-Z. and A.S.A.-A.; visualization, O.M.N.; supervision, C.A.C.W.; project administration, O.M.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new primary data were created or collected in this study. The analysis is based exclusively on secondary data derived from previously published and publicly available academic sources indexed in the Scopus database. Search results, screening records, and bibliographic datasets (CSV and BibTeX formats) were generated as part of the systematic review process and can be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Supplementary note: Full Scopus search strategy. Database: Scopus. Search field: TITLE-ABS-KEY. (“Buy Now Pay Later” OR “BNPL”). AND (“impulsive buying” OR “impulse buying” OR “impulsive purchase” OR “impulse purchase”). AND (“post-purchase regret” OR “consumer regret” OR “purchase regret”). AND (“behavioural finance” OR “consumer behaviour” OR “digital payment”). Last search date: 31 December 2025. Limits and filters applied: English-language publications only; peer-reviewed journal articles and review papers; conference proceedings, book chapters, editorials, and grey literature were excluded. Temporal filtering (2018–2025) was applied during the screening stage.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere appreciation to Che Aniza Che Wel and Siti Ngayesah Ab Hamid for their invaluable supervision, continuous guidance, and constructive feedback throughout the development of this manuscript. Their academic insight and unwavering support were instrumental in shaping the quality and direction of this work. The authors also thank Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM) for providing educational support during the research process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BNPL | Buy Now, Pay Later |

| CASP | Critical Appraisal Skills Programme |

| CDT | Cognitive Dissonance Theory |

| CMV | Standard Method Variance |

| IBT | Impulsive Buying Theory |

| MMAT | Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool |

| PLS-SEM | Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling |

Appendix A

Table A1.

PRISMA 2020 Checklist.

Table A1.

PRISMA 2020 Checklist.

| Item | Section | Checklist Requirement (PRISMA 2020) | Location in Manuscript |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Title | Identify the report as a systematic review. | Title |

| 2 | Abstract | Provide a structured summary following PRISMA for Abstracts (or equivalent). | Abstract |

| 3 | Rationale | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of existing knowledge. | 1. Introduction |

| 4 | Objectives | Provide an explicit statement of the objective(s) or question(s) addressed. | 1. Introduction |

| 5 | Eligibility criteria | Specify inclusion and exclusion criteria and how studies were grouped for synthesis. | 2.2 + Table 1 |

| 6 | Information sources | Specify all databases, registers, websites, organisations, and other sources searched, and the date last searched. | 2.1 |

| 7 | Search strategy | Present full search strategies for all databases, registers, and websites, including filters and limits used. | Appendix A (Supplementary note: Full Scopus search string) |

| 8 | Selection process | Specify the methods used to decide whether a study met inclusion criteria, including the number of reviewers and the use of automation tools. | 2.3 |

| 9 | Data collection process | Specify methods used to collect data, including the number of reviewers and verification procedures. | 2.4 |

| 10 | Data items | List and define all outcomes and other variables for which data were sought. | 2.4 |

| 11 | Study risk of bias assessment | Specify methods used to assess risk of bias in included studies. | 2.5–2.6 + Table 3 |

| 12 | Effect measures | Specify effect measures for each outcome (if a quantitative synthesis is conducted). | Not applicable (no quantitative synthesis or meta-analysis conducted) |

| 13 | Synthesis methods | Describe the processes used to prepare data, tabulate results, and synthesise findings; justify choices. | 2.4 + 3.5 |

| 14 | Reporting bias assessment | Describe methods used to assess risk of bias due to missing results (publication or reporting bias). | 2.6 |

| 15 | Certainty assessment | Describe methods used to assess certainty or confidence in the body of evidence (e.g., GRADE). | Not assessed (no meta-analysis; high heterogeneity across study designs and outcomes) |

| 16 | Study selection | Describe results of the search and selection process, ideally using a flow diagram. | 2.3 + Figure 1 |

| 17 | Study characteristics | Cite each included study and present its characteristics. | 3.3 + Table 2 |

| 18 | Risk of bias in studies | Present assessments of risk of bias for each included study. | 3.4 + Table 3 |

| 19 | Results of individual studies | For each study, present summary statistics and findings where available. | Table 2 |

| 20 | Results of syntheses | Summarise the main results of the synthesis, including patterns and relationships. | 3.5–3.6 |

| 21 | Reporting biases | Present assessments of risk of bias due to missing results. | 2.6 + Limitations |

| 22 | Certainty of evidence | Present assessments of certainty or confidence in the evidence. | Not assessed (no meta-analysis; high heterogeneity across study designs and outcomes) |

| 23 | Discussion | Provide a general interpretation of results in the context of other evidence and discuss limitations and implications. | 4. Discussion + 5. Conclusions |

| 24 | Registration and protocol | Provide registration information for the review protocol or state if not registered. | 2. Methodology (PRISMA compliance statement) |

| 25 | Support | Describe sources of financial or non-financial support for the review. | Funding/Acknowledgements |

| 26 | Competing interests | Declare any competing interests of the review authors. | Conflicts of Interest |

| 27 | Availability of data, code, and other materials | Report on which materials are publicly available and where they can be accessed. | 2.7 Transparency + Data Availability |

References

- OECD. Consumer Finance Risk Monitor; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelli, G.; Gambacorta, L.; Pancotto, L. Buy Now, Pay Later: A Cross-Country Analysis. Bank for International Settlements Quarterly Review, March 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.bis.org/publ/qtrpdf/r_qt2312e.htm (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Worldpay. Buy Now, Pay Later Guide for Smaller Merchants. 2023. Available online: https://www.worldpay.com/en/insights/articles/buy-now-pay-later-guide-merchants (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Bellary, S.; Bala, P.K.; Chakraborty, S. Exploring Cognitive-Behavioral Drivers Impacting Consumer Continuance Intention of Fitness Apps Using a Hybrid Approach of Text Mining, SEM, and ANN. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 81, 104045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prelec, D.; Loewenstein, G. The Red and the Black: Mental Accounting of Savings and Debt. Mark. Sci. 1998, 17, 4–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakar, R.M.; Fauziyah, N.; Rahmat, A. Do Consumers Perceive Impulsive Buying and Pain of Payment? E-Commerce Transactions Using Pay Later, E-Wallet, and Cash-On-Delivery. Gadjah Mada Int. J. Bus. 2025, 27, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rook, D.W.; Fisher, R.J. Normative Influences on Impulsive Buying Behavior. J. Consum. Res. 1995, 22, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeelenberg, M.; Pieters, R. A Theory of Regret Regulation 1.0. J. Consum. Psychol. 2007, 17, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z. Buy Now, Pay Later: Market Impact and Policy Considerations (Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Brief No. 25-03). Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. 2025. Available online: https://www.richmondfed.org/publications/research/economic_brief/2025/eb_25-03 (accessed on 14 December 2025).