Abstract

The growth of e-commerce live streaming has expanded sales channel options for fresh agricultural suppliers. This study investigates a two-echelon supply chain consisting of a fresh agricultural supplier and downstream retailers. Using differential game theory, we examine the supplier’s preservation technology level and product greenness, analyzing and comparing equilibrium strategies under three different modes: e-commerce platform sales mode (SP), head streamer sales mode (SH) and ordinary streamer sales mode (SN). The results demonstrate that SP is the dominant strategy when retailers’ marginal profits are low. Conversely, under high marginal profit conditions, the optimal selection depends on streamer cooperation costs: SH is preferred with low head streamer costs; widening cost gaps introduce temporal considerations between SH and SN; further gap expansion makes SN optimal. Furthermore, product greenness is related to supplier’s marginal profit, while the preservation technology level is jointly determined by supplier’s marginal profit and retailers’ inspection costs. Finally, combinations of these modes are also investigated.

1. Introduction

With the rapid development of the Internet, the e-commerce industry in the field of fresh agricultural products has gradually emerged. Especially in recent years, live streaming e-commerce has developed rapidly and become a significant sales avenue for fresh agricultural products. Evidence from major promotional events illustrates its expanding influence: during the “Tmall 618” campaign (a major mid-year online shopping festival hosted by Alibaba’s Tmall platform), the fresh food category saw a GMV growth rate exceeding 261%, attributable to live streaming (https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1802257171027885821&wfr=spider&for=pc accessed on 12 December 2024). Influencer collaborations, such as that between YouTube creator Ann Reardon and the brand HelloFresh, have further demonstrated the model’s capacity to enhance brand visibility and sales (https://www.cifnews.com/article/158422 accessed on 12 December 2024).

However, this sales model also presents significant challenges. Some live streaming platforms face considerable quality control risks in product selection, and instances of selling inferior products as premium ones have been reported. Moreover, the channel dominance exerted by head streamers can compress suppliers’ profit margins and potentially disincentivize investments in innovation of preservation technology and green technology, thereby affecting product sustainability and long-term supply chain resilience. Thus, identifying suitable online sales channels for fresh agricultural suppliers remains an important research question.

Amidst heightened governmental and consumer focus on food safety, the greenness of fresh agricultural products has become a decisive factor influencing. According to the definition of China’s Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (http://www.moa.gov.cn/nybgb/2012/dbaq/201805/t20180516_6142243.htm accessed on 12 December 2024), agricultural product greenness quantifies nutritional value and the environmental and health impacts of production chemical residues (e.g., pesticides, heavy metals). Higher greenness indicates greater nutritional value, lower environmental pollution, and reduced health risks from residues, serving as a key differentiator from conventional products. This paper terms supplier’s effort to enhance product greenness as “green technology investment effort”. Additionally, given product perishability and consumer preference for freshness, suppliers must continuously enhance preservation technology to prevent spoilage, while downstream retailers must execute rigorous freshness screenings. Examples include the supplier adopting advanced nano-preservation films and vacuum pre-cooling instead of basic refrigeration, or e-platform like Kuaishou (a short-video and live streaming e-commerce platform in China) conducting random inspections through certified third-party agencies (https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=Mzg5NzcyMDg2Nw==&mid=2247492437&idx=2&sn=550b982ef6719a3ee15c3b5d59a2754a&chksm=c06fd419f7185d0fd9050c5d1323bda22cf3b0a771d8cbd1fc1707dcf1139822669eacd0b4e8&scene=27 accessed on 12December 2024). This paper defines such practices as “supplier preservation technology investment effort” and “downstream retailer freshness detection effort” [1]. So, how should a fresh agricultural supplier allocate resources between preservation and green technologies? How should downstream retailers determine freshness detection effort to maximize profits? And crucially, how do consumer preferences for preservation technology level versus greenness impact the equilibrium strategies of supply chain participants?

To address these issues above, our research primarily focuses on the following three questions:

- (1)

- For fresh agricultural product suppliers, is it more advantageous to sell on an e-commerce platform or through live streaming sales?

- (2)

- If a fresh agricultural product supplier chooses live streaming sales, would partnering with a head streamer or an ordinary streamer yield greater profitability?

- (3)

- Do preferences regarding preservation technology level and environmental sustainability influence fresh product suppliers’ decisions on different sales channels?

In order to answer these questions, we build a two-echelon supply chain, which consists of a fresh agricultural supplier, an e-commerce platform or streamers, and use differential game theory to analyze the dynamic evolution of preservation technology level and greenness. We also analyze the changes in profit in different channels, so as to help suppliers make decisions. This paper contributes in the following three aspects: First, we develop a dynamic revenue optimization model for fresh agricultural supply chains, identifying key thresholds for suppliers’ choices among three sales modes—e-commerce platform, head streamer, and ordinary streamer—and clarifying the profit boundaries and applicable conditions of each mode. Second, by incorporating two state variables: preservation technology level and product greenness, we find the relationship between the state variables and supply chain participants’ marginal profit, and freshness detection effort, respectively. This finding systematically reveals the dynamic formation pathways of quality attributes in multi-modal sales environments for fresh agricultural products, advancing beyond prior research that often focused on single quality dimensions or static analysis. Third, we extract practically actionable managerial insights: suppliers should dynamically adjust their sales modes according to marginal profit levels and cost structures, and balance short-term gains with long-term green transition goals in markets where consumer preference for freshness significantly outweighs that for green attributes. These contributions not only provide quantitative support for sales-mode decision making by fresh agricultural suppliers but also offer theoretical foundations for promoting the sustainable development of the live streaming e-commerce industry.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the relevant literature and highlights the innovation and contribution of this paper. Section 3 introduces the model setting in this study. In Section 4, we derive the optimal results of the three models, followed by a comparative analysis in Section 5. Section 6 provides a detailed numerical analysis of the equilibrium results. In Section 7, we extend the original model and consider two dual channels. Finally, Section 8 concludes the paper, discusses managerial implications, and summarizes directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

In this section, we divide the literature related to this paper into three parts: (1) Analysis of decision making factors of the fresh agricultural supply chain, (2) E-commerce platform and live sales, (3) Application of differential game in supply chain decision making.

2.1. Analysis of Decision-Making Factors of Fresh Agricultural Supply Chain

This study analyzes two key decision factors affecting fresh agricultural product quality: preservation effort and green effort. Regarding preservation effort, it refers to the technical and managerial investments made by supply chain actors to maintain the freshness of fresh agricultural products. Existing research primarily examines its impact mechanisms from policy, technological, and behavioral perspectives: Zhang et al. investigated the impact of dual carbon policies on preservation effort [2]. Their findings indicate that increased carbon taxes and carbon trading prices reduce preservation levels. Liu et al. constructed a novel product supply chain model integrated with blockchain technology, using product freshness and reputation as state variables. Their research reveals that the introduction of blockchain incentivizes suppliers to enhance preservation efforts while prompting e-commerce platforms to adjust their marketing strategies, ultimately optimizing the long-term freshness level of the supply chain [3]. Li et al. found through comparative research that blockchain traceability systems can incentivize preservation efforts in supply chains but may also intensify waste due to information transparency, with product shelf life being the key determinant of its win–win effect [4]. Bai et al. constructed a “Gen AI + blockchain” integrated model, which effectively incentivizes preservation efforts in the agricultural supply chain and enhances consumer trust by optimizing inventory and preservation resource allocation [5]. While prior studies emphasize how emerging technologies drive preservation efforts, we model preservation effort as an endogenous decision variable in a differential game framework. This approach reveals how economic incentives shape preservation investments across sales modes. Yu et al. examined how a supplier, as a preservation effort decision-maker, balances quality disclosure versus non-disclosure, demonstrating that robust preservation effort mitigates retailers’ information disclosure dilemma [6]. Zhang et al. modeled a fresh food supply chain to analyze different leadership modes and preservation strategies, demonstrating that supplier-led service level delays enhance preservation effort, while retailer gains lower wholesale prices by improving service level under low-preservation conditions [7]. While existing studies primarily analyze preservation efforts from static perspectives, this study employs a differential game approach to model preservation effort as a time-varying continuous decision process. This dynamic framework offers a more granular capture of the evolving nature of preservation behaviors in fresh agricultural supply chains.

Regarding green effort, it is defined in this study as quality-oriented investment aimed at enhancing product nutritional value and reducing chemical residues. In contrast, most existing studies define green effort from the perspectives of environmental certification or carbon emissions: Wang et al. studied a green fresh supply chain where farmers’ green improvement level positively affects demand, while comparing green improvement level under three different contract modes [8]. Tan et al. incorporated greenness into an agricultural product supply chain model, using game theory to analyze green decision level among supply chain members with and without cost-sharing for green investment [9]. While Tan et al. analyzed green investment through static game theory, this study employs a dynamic framework to reveal how green efforts evolve with marginal profit and sales modes, demonstrating long-term threshold effects. Chen et al. introduced behavioral factors (overconfidence and reference price) into green supply chain analysis, revealing how irrational decisions affect product greenness and supply chain coordination [10]. Philip and Marathe developed a farmer–retailer supply chain game model under demand and yield uncertainty, introducing greenness into the demand function [11]. Cai et al. not only examined manufacturers’ green investment decisions but also further analyzed the moderating effect of green efficiency on channel strategies under retailer fairness concerns and dual-channel structures [12]. Existing studies predominantly treat “green effort” as a macro-level investment in environmental improvement and analyze it through static models. In contrast, we define green effort as a quality-focused investment to enhance nutritional value and reduce chemical residues, and use dynamic methods to examine its long-term evolution.

Furthermore, few studies consider the effects of preservation effort and green effort on the demand for fresh agricultural products at the same time. Our research bridges this gap by incorporating consumer preferences for both preservation technology levels and product greenness, further studying the influence of these preferences on the profit of fresh agricultural suppliers when they choose different sales models.

2.2. E-Commerce Platform and Live Sales

The e-commerce platform sales model remains a focal point in supply chain management. Most existing literature on e-commerce platforms examines them from perspectives such as comparisons with physical retail or analysis of platform technological empowerment: Zhao et al. employed an evolutionary game approach to determine whether brand influence or platform traffic confers a comparative advantage in omnichannel negotiations [13]. Yu et al. demonstrated the critical role of commission rates in e-commerce channel operations within a manufacturer’s dual-channel framework, combining platform-based private label sales and physical retail distribution [14]. Jiang et al. applied the Stackelberg game to model a supply chain comprising a platform and multiple retailers, examining how platform digital empowerment affects the profits of both the platform and the retailers [15]. Yan et al. find that when e-commerce platforms’ own promotions are less effective, cross-platform cooperative promotion (e.g., joint membership) increases platform profits and supply chain sustainability [16].

Live streaming sales, as an important branch of e-commerce, have attracted increasing research attention in recent years. Some studies employ empirical methods to examine consumer behavior. For instance, Duong et al. integrated live streaming interaction with blockchain technology and empirically analyzed how the two jointly promote online agricultural product purchases by building product trust, providing new empirical evidence for research on trust mechanisms in agricultural e-commerce [17]. Other studies utilize analytical modeling to examine participant behavior in live streaming supply chains. Some studies primarily focus on the overall impact of live streaming on supply chains, such as risks and cost allocation. For example, Xu et al. integrated blockchain technology and influencer economy risks into the analytical framework of agricultural supply chains. They revealed that, in the context of platforms empowering product quality through blockchain technology, the introduction of live streaming channels may amplify the uncertainty of supply chain returns due to the influencer effect [18]. Lou et al. applied the Stackelberg approach to study the impact of fairness concerns from both live streamers and manufacturers on the allocation of after-sales service costs [19]. While others delve into the specific strategic decisions of participants in live streaming, such as the selection of influencer types, pricing, and cooperation conditions, Ye et al. used game theory to analyze sellers’ preferences for influencer types and pricing strategies, showing these choices depend on the bargaining power in the influencer industry and fixed payments to top influencers [20]. Cui et al. demonstrate that with high live streaming spillover effects, commission rates and cost-sharing mechanisms can coordinate sales mode decisions between enterprises and influencers, achieving win-win outcomes and enhancing overall profit [21]. Du et al. examined the manufacturer’s channel selection between celebrity streamers and ordinary streamers, while this study further incorporates the e-commerce platform sales model into the comparative framework [22]. Through a dynamic model, we systematically reveal the differences among the three channels: platform sales, head streamer collaboration, and ordinary streamer collaboration. Cui et al. employed a game-theoretic approach to examine optimal collaboration strategies between brand owners and streamers aimed at reducing product return rates [23].

This study differs from the aforementioned research in the following aspects. First, it shifts the research focus from the predominantly studied industrial and virtual products to fresh agricultural products. Second, it employs the differential game method instead of static or empirical approaches. Third, it establishes a systematic comparison between traditional e-platform sales and streamer-led live streaming modes, departing from prior research that typically juxtaposes e-commerce with offline retail or solely compares head versus ordinary streamers. Together, these contributions address gaps in the current literature on live streaming e-commerce supply chain.

2.3. Application of Differential Game in Supply Chain Decision-Making

Differential game theory provides a robust strategic framework for analyzing continuous-time, multi-agent systems where participants aim to optimize individual objectives and achieve a Nash equilibrium. Initially applied to advertising research, Zhang et al. examined how profit margins influence cooperative advertising decisions [24]. Cheng et al. developed a two-stage pricing model incorporating consumer data and advertising effort to compare differentiated versus unified pricing benefits in supply chains [25]. Within the specific domain of fresh produce supply chains, differential game theory has gained widespread traction. Zhang and Ma. investigated differential game theory between fresh product retailer and supermarket supplier in dual-channel systems, comparing optimal strategies under different return policies (refunds versus exchanges) [26]. Liu et al. analyzed how supplier–retailer relationships affect investments in pre-cooling and carbon reduction technologies, thereby impacting aggregate profits [27]. Ma et al. evaluated preservation technology and carbon reduction levels from long-term, dynamic perspectives in cold chain systems [28]. Liu et al. incorporated blockchain-supported traceability reputation and product freshness to examine e-platform’s choice between resale or agency models for fresh food sales [29].

The preceding literature underscores the suitability of differential game theory is well-suited for addressing long-term dynamic decision making problems in fresh agricultural supply chains. Compared to other dynamic models, differential games provide closed-loop optimal strategies for firms through the Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman equation. This characteristic renders the approach particularly advantageous for analyzing state variables, such as preservation technology levels and greenness, that require sustained investment to maintain. However, existing studies have rarely employed this dynamic approach to examine decision making in fresh product supply chains when introducing live streaming channels. To bridge this gap, this paper develops a differential game model with preservation technology level and greenness as state variables to investigate fresh agricultural suppliers’ channel selection strategies between e-commerce platforms and live streaming channels from a dynamic perspective.

In summary, we compare our research with the existing related research in Table 1 List of the most relevant literature.

Table 1.

List of the most relevant literature.

3. Model Assumption and Symbol Introduction

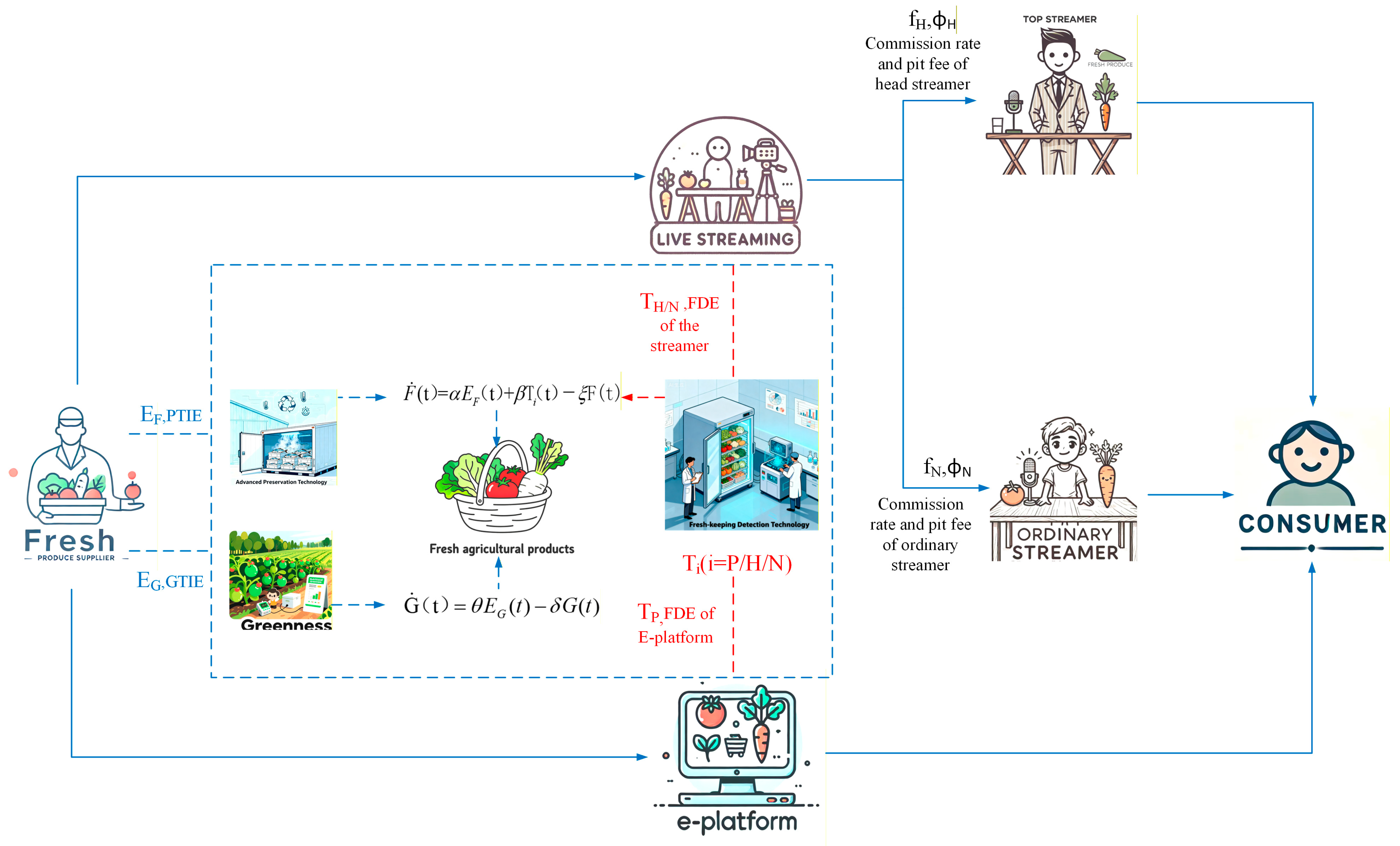

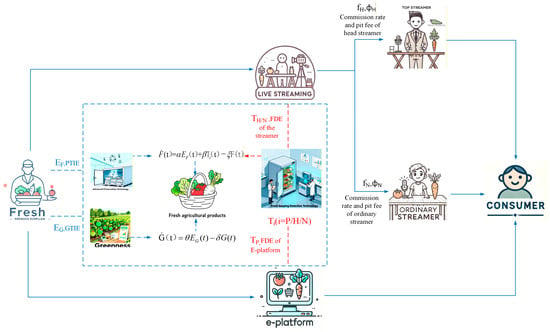

We investigated a fresh agricultural supply chain system encompassing two sales models: an e-commerce platform and live streaming. In the P-model (e-commerce platform sales), the supplier first invests in preservation technologies and green technologies to enhance the quality of fresh agricultural products, which are subsequently sold on the e-commerce platform. In the live streaming sales model, the supplier may opt for either the H-model (head streamer sales) or the N-model (ordinary streamer sales) for product sales. It is crucial to note that within both the P-model and H-model, the platform or the head streamer conducts freshness detection on products to ensure their high quality, which in turn drives supplier to improve their preservation technology levels to meet the product requirements set by the platform or the head streamer. Figure 1 shows the structure of the fresh agricultural supply chain. Table 2 provides the specific definitions of all parameters and variables mentioned in the text.

Figure 1.

The structure of the fresh agricultural supply chain. Note: Blue dotted line box indicates the decision-making process between suppliers and downstream retailers, while the red dotted line denotes that this variable is determined by downstream retailers. Blue dashed lines and font denote variables determined by suppliers; red dashed lines and font denote variables determined by downstream retailers.

Table 2.

The main parameters and symbols used in this paper.

This study develops an infinite-horizon differential game model with two state variables: preservation technology level F(t) and the product greenness G(t). Differential game theory is adopted because it captures the dynamic and strategic interaction among supply chain members over time, allowing us to analyze how their decisions on technology investment and quality control evolve under long-term incentives. Their dynamic evolution draws on the classical Nerlove–Arrow capital accumulation model [36]: state variables are enhanced through strategic investments and efforts, with the marginal contribution of each investment measured by specific coefficients (e.g., α, β, θ). At the same time, state variables undergo natural depreciation at constant rates, denoted by the decay rates ξ and δ. Setting the decay rates as constants captures the diminishing-value characteristic of the state variables while preserving the model’s analytical tractability. From a managerial perspective, constant decay simplifies the planning of recurring investments while still representing the erosion of technological and green advantages over time. The infinite-horizon setting directs players’ attention to long-term gains and facilitates the analysis of the system’s long-run stable equilibrium.

This study employs a linear demand function and assumes constant decay rates, primarily for the sake of theoretical simplicity and analytical tractability. These classic assumptions allow us to derive clear analytical solutions for the relationship between technology investment and profit under different sales models and to distill interpretable decision thresholds. Admittedly, these simplifying assumptions impose limitations on capturing real-world complexity. Relaxing these assumptions—for instance, by introducing demand nonlinearity or time-varying decay rates—would increase the difficulty of solving the model but could further uncover phenomena such as diminishing marginal returns on technology investment, synergies between green and preservation factors, and strategic adjustments in dynamic environments, offering a richer perspective for understanding the long-term evolution of supply chains.

Based on the above contents and the research of Ma et al. and Zhang et al., the higher the level of preservation technology, the better the freshness of products and the longer the preservation time [1,28]. We describe the dynamic change process of supplier’s fresh-keeping technology level as follows

where denotes the preservation technology level at time t, represents the rate of change in the level of preservation technology with time, represents the preservation technology investment effort (PTIE) of suppliers, and represents the freshness detection effort (FDE) of downstream retailers, denote the effect coefficients of the preservation technology investment efforts and freshness detection efforts on the preservation technology level [1,28,37]. They reflect the efficiency with which investment is converted into technological improvement. A larger value of α and β indicates that each unit of effort invested by the supplier yields a more significant increase in the preservation technology level. represents the initial value of the preservation technology level. Over time, the preservation technology level naturally depreciates due to equipment aging and technological obsolescence, with a decay rate of .

Similarly, as government policies and consumer preferences evolve, the greenness of fresh products has become a critical factor influencing sales. Therefore, we assume that the dynamic change process of the greenness of fresh products is expressed by the following formulation, with the initial value of the greenness being .

According to Liang et al., we describe the dynamic change process of the green degree of fresh agricultural products as follows [38]

where represents the change rate of greenness of fresh products with time, represents the supplier’s green technology investment effort (GTIE), and represents the impact elasticity of green technology investment effort on product greenness. A higher value of θ indicates that each additional unit of green technology investment made by the supplier results in a more pronounced improvement in greenness. represents the initial value of greenness. Similarly, with the passage of time, the green technical standards given by the government are gradually improved, or the green technical equipment is backward, which leads to the gradual slowdown of the greenness growth of products, and its decay rate is represented by .

We assume that the investment cost of green technology, the investment cost of preservation technology, and the cost of freshness detection of downstream retailers are all quadratic functions of the investment efforts of green technology, preservation technology and freshness detection, respectively [34,35], namely

This quadratic cost function is common in economics and supply chain research because it reflects the real-world situation of “the more you invest, the higher the marginal cost,” and it is convenient for mathematical modeling and solving optimal decisions. Where are the cost coefficients of green technology investment efforts, preservation technology investment efforts and freshness detection efforts, respectively. These cost coefficients (λ) represent the economic efficiency of corresponding investments, where higher values indicate greater marginal costs for achieving the same level of technological improvement or detection accuracy.

We assume that the demand for fresh products has a linear positive correlation with the level of preservation technology, greenness (https://sww.hangzhou.gov.cn/art/2025/8/18/art_1229451271_58904641.html accessed on 15 December 2024) and freshness detection effort. Referring to the demand function settings of Ma et al. and Zhang et al., Liu et al., and Xia et al., we express the demand function by the following formula [1,3,28,39].

where represents the potential market demand of fresh agricultural products, indicates the market influence of e-commerce platform and streamer, and the influence of head streamer is higher than that of the ordinary streamer, that is .

4. Model Analysis

In this section, superscript P, H, and N represent e-commerce platform, head streamer, and ordinary streamer mode, respectively.

4.1. Mode of E-Commerce Platform (SP)

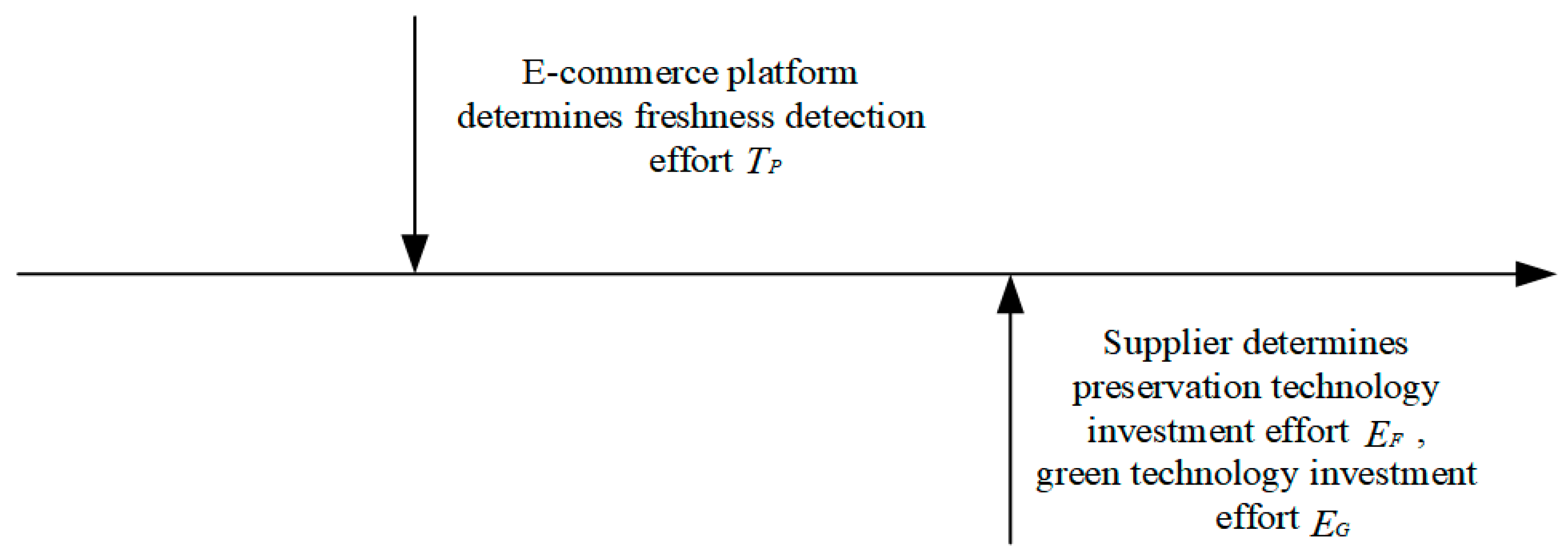

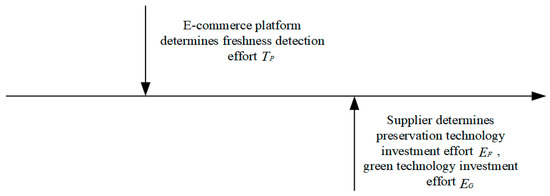

E-commerce platforms often have a great influence and pay attention to their own goodwill. Therefore, under SP mode, the e-commerce platform is the leader and the supplier is a follower, and the decision making order is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Decision sequence of SP mode.

The revenue functions of the supplier and the e-commerce platform are

Proposition 1.

The optimal equilibrium strategies for PTIE, GTIE of the supplier, and FDE of the e-commerce platform in the mode of SP are listed below.

Corollary 1.

The optimal state trajectories of the preservation technology level and greenness are as follows.

The maximum expected benefits of the supplier, e-commerce platform, and fresh supply chain system are, respectively,

Coefficient terms (such as , etc.) and proof. See Appendix A.

Corollary 2.

The influence of key parameters on the supplier’s best PTIE, GTIE, and the e-commerce platform’s best FDE is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Sensitivity analysis in the mode of e-commerce platform (SP).

Corollary 2 reveals several key relationships governing the equilibrium strategies.

First, both the optimal PTIE and GTIE are positively correlated with the supplier’s marginal profit. The greater the supplier’s marginal profit, the more they earn, and the more motivated they are to invest in the preservation technology level and greenness. This relationship reveals the essence of the profit-driven mechanism in supply chains: sufficient profit margins serve as a fundamental incentive for driving quality upgrades and technological innovation. Second, the optimal PTIE is also positively influenced by the e-commerce platform’s marginal profit. The greater the marginal profit of the e-commerce platform, the more willing she is to invest in the fresh-keeping inspection of products. Third, consumer preferences for preservation and greenness have a direct positive impact on the supplier’s investment efforts. As consumers’ preference for preservation technology level and greenness of fresh agricultural products increases, the market has greater demand for products with higher preservation technology level and greenness, which prompts suppliers of fresh agricultural products to increase their investment in preservation technology level and greenness. At the same time, the increase in consumers’ preference for the preservation technology level of fresh agricultural products can also promote the e-commerce platform to pay more attention to the FDE of products, so the preference for preservation technology level is positively related to the best FDE. The rising consumer demand for products with high freshness and green attributes stimulates suppliers to increase investments in these areas. Simultaneously, consumers’ emphasis on preservation technology motivates e-commerce platforms to enhance freshness detection efforts, reflecting the pivotal role of demand-side pull. Finally, the influence coefficient of FDE on demand is positively related to the FDE of the e-commerce platform. This suggests that as consumers place greater importance on the platform’s inspection and verification role, it creates a feedback loop that amplifies the platform’s incentive to invest more heavily in freshness detection.

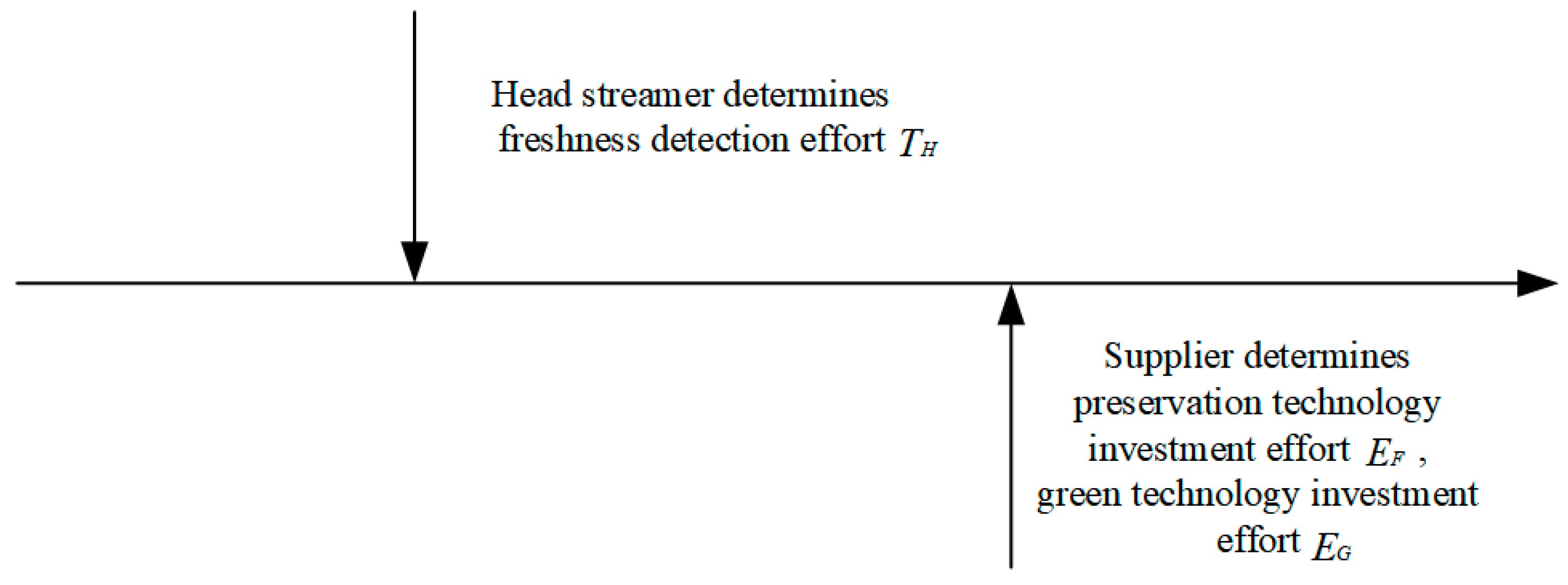

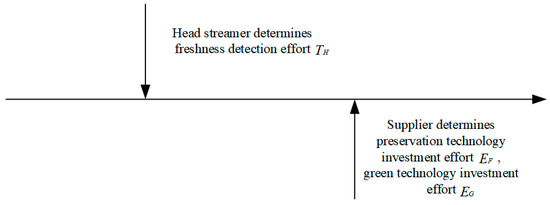

4.2. Mode of Head Streamer (SH/SN)

The head streamer has great influence and strong sales ability, and it occupies a dominant position in the channel. Therefore, in SH mode, the head streamer is the leader and the supplier is the follower, and the decision making order is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Decision sequence of SH mode.

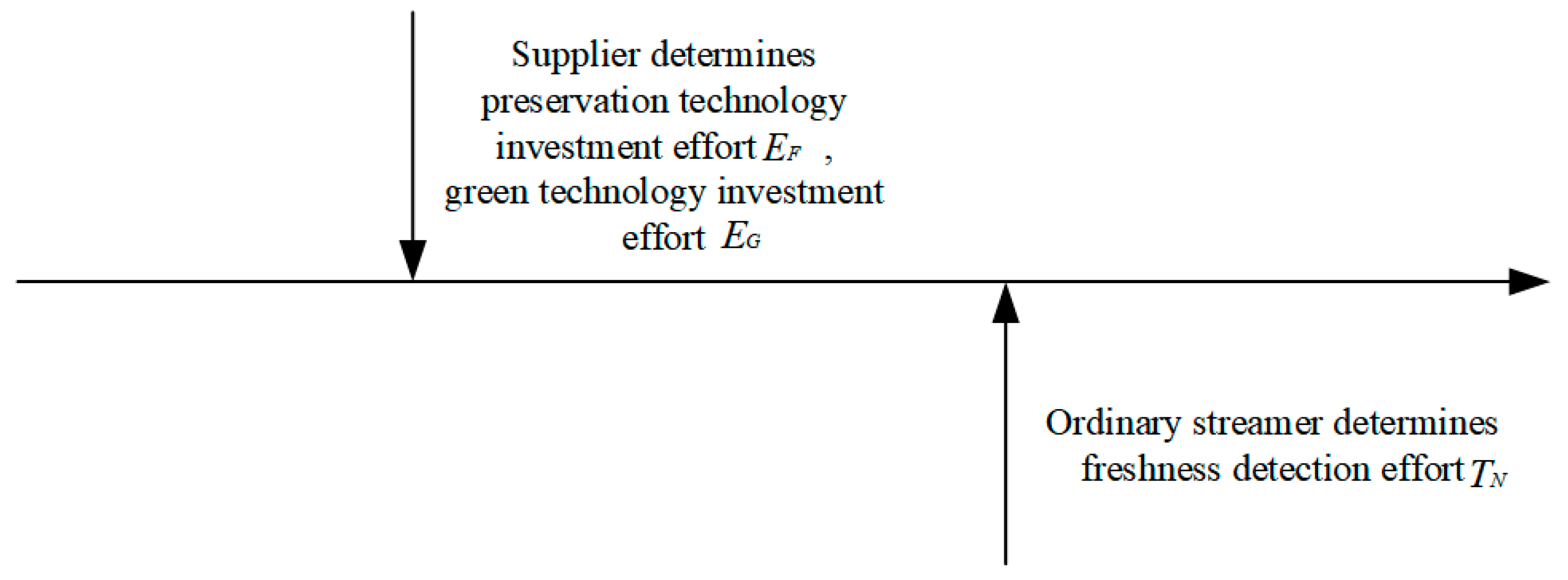

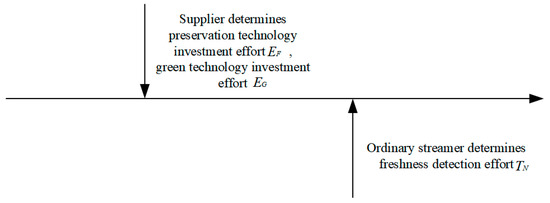

An ordinary streamer has a weak influence and sales ability, and is in a weak position in the channel. Therefore, in SN mode, the supplier is the leader and the ordinary streamer is the follower, and the decision making order is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Decision sequence of SN mode.

The supplier chooses to cooperate with the streamer to sell, they have to pay the streamer a commission of proportion according to the total profit and a fixed pit fee . It is worth noting that , .

The revenue functions of the supplier and the head/ordinary streamer are [1,2,40]

Proposition 2.

The optimal equilibrium strategies for PTIE, the GTIE of the supplier, and FDE of the head streamer in the mode of SH/SN are listed below.

Corollary 3.

The optimal state trajectories of the preservation technology level and greenness are as follows.

The maximum expected profit values of the supplier, head streamer, and fresh supply chain system are, respectively,

Coefficient terms (such as , etc.) and proof. See Appendix B and Appendix C.

Corollary 4.

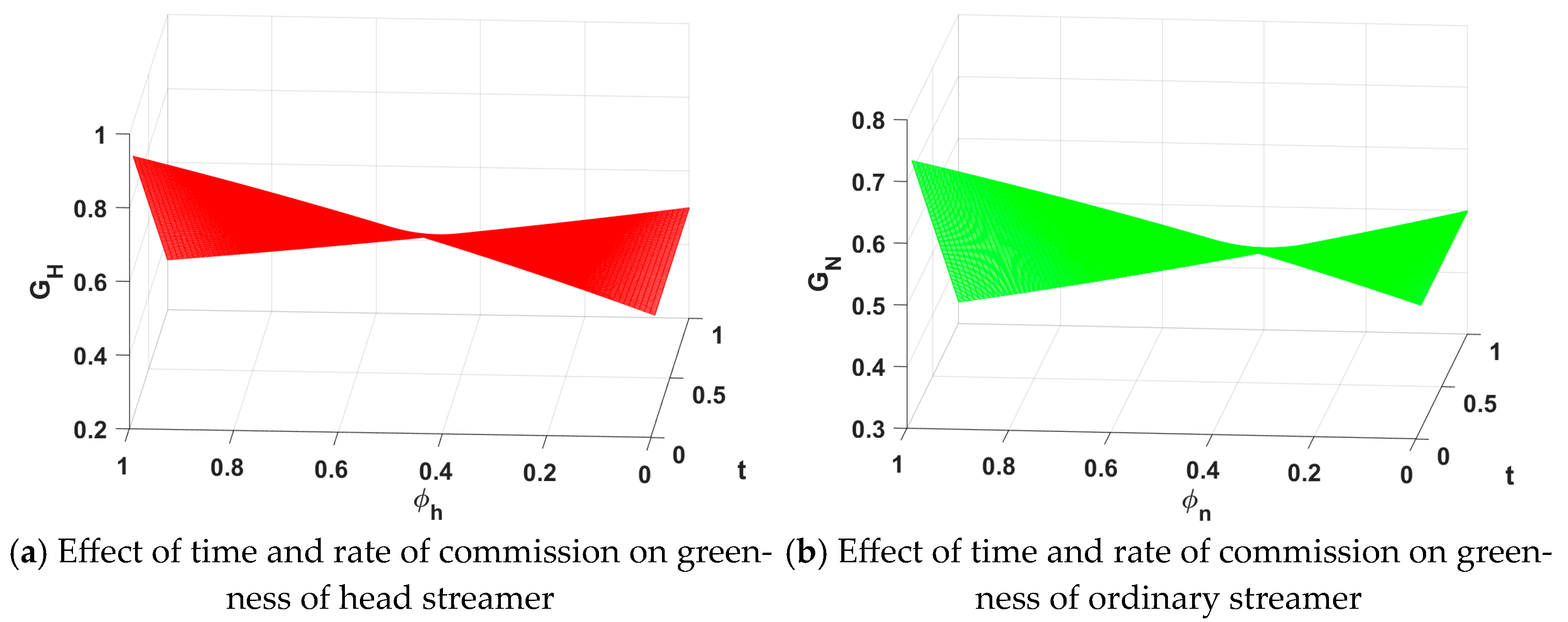

Influence of commission ratio on supplier’s optimal PTIE, GTIE, and streamer’s optimal FDE are

, , .

Corollary 4 shows that when the supplier chooses to cooperate with the head/ordinary streamer to sell fresh agricultural products, the commission rate serves as a pivotal determinant of each party’s strategic decisions. Specifically, the commission rate is negatively related to PTIE and GTIE decided by the supplier. A higher commission rate reduces the supplier’s profit margin, which in turn lowers investment in preservation and green technologies. On the contrary, the head/ordinary streamer’s commission rate is positively correlated with the FDE decided by the streamer. Similarly, this is because the higher the streamer’s commission rate, the more they earn, and the more money they have to invest in product preservation testing. This dual-direction mechanism highlights a fundamental trade-off in streamer-based supply chains: while higher commissions can strengthen downstream quality monitoring, they may simultaneously weaken upstream production-side investment. Therefore, designing a balanced commission structure becomes critical to aligning incentives across the chain and achieving coordinated improvements in both product quality and supply-chain profitability.

5. Comparisons Among Different Models

On the basis of the above model analysis, this section compares the optimal PTIE and GTIE of the fresh agricultural supplier, the FDE of downstream retailers, and the supplier’s profit under three different modes, and it further analyzes the interaction between sales channels and optimal strategies and the optimal strategy selection of the supplier. Proof is shown in Appendix D.

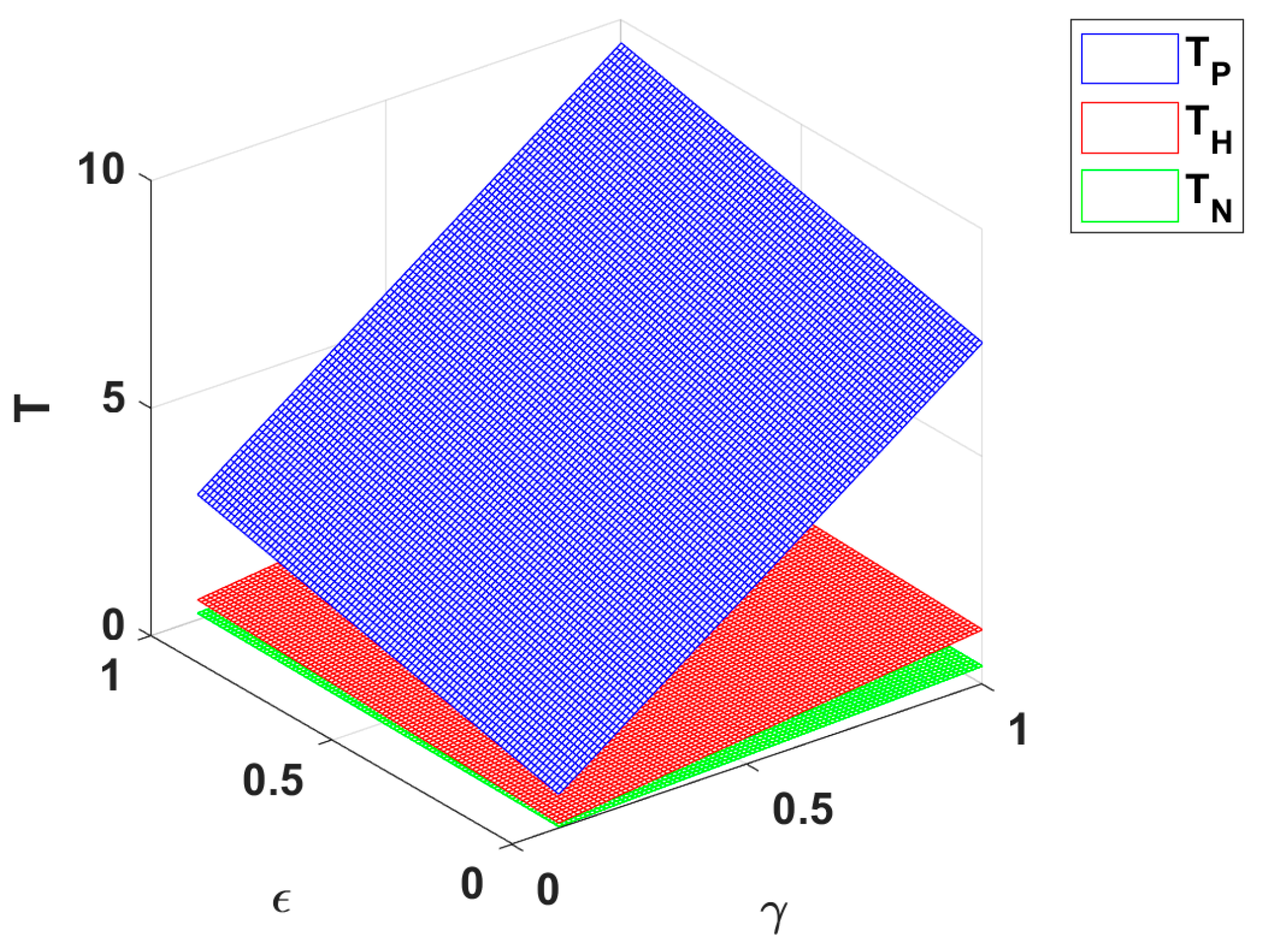

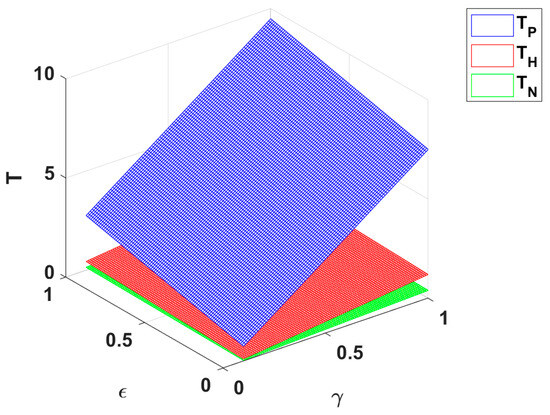

Proposition 3.

Comparison between the optimal PTIE and GTIE of the fresh agricultural product supplier and the FDE of downstream retailers under three sales modes: e-commerce platform, head streamer and ordinary streamer.

(1) The relationship between the PTIE and GTIE (That is ) of fresh agricultural product suppliers under three sales modes is as follows.

- If , then is the largest; if , then is the largest; if , then is the largest.

- For specific comparisons, see Table A1 in Appendix D.

From Equations (5) and (10), we can see that , respectively, represents the marginal profit of the supplier under the SP/SH/SN modes. Proposition 3-(1) indicates that fresh agricultural suppliers’ investments in preservation and greenness depend on the level of marginal profit they achieve under different sales modes. When a channel offers a higher net marginal profit, the supplier has the strongest economic incentive to invest in technology within that channel, and accordingly, the optimal level of investment is also the highest. When marginal profits are higher, it indicates that the marginal benefit curve of technological investment shifts upward. According to the principle of optimal input of production factors, the supplier will correspondingly increase their level of technological investment. Thus, profit margin drives quality upgrading: when a sales mode yields higher profits, the supplier’s incentive and ability to invest in preservation and green technologies increase. Based on this, the supplier should prioritize sales modes that offer sustainable profits and develop long-term technology investment plans accordingly. At the same time, it is recommended that e-commerce platforms and streamers optimize profit-sharing mechanisms to incentivize suppliers’ quality investments, rather than relying solely on price competition or traffic subsidies.

(2) The FDE size relationship of downstream retailers under the three sales modes is as follows.

- If , then is the largest; if , then is the largest; if , then is the largest.

- For specific comparisons, see Table A2 in Appendix D.

As shown in Proposition 3-(2), the freshness detection effort of downstream retailers remains correlated with their marginal profit. As indicated in Appendix D, denote the thresholds derived from comparing with , with and with , respectively. That is to say, when the net marginal profit of retailers P/H/N is the highest, the corresponding channel also achieves the maximum level of preservation and detection effort. Therefore, the magnitude of FDE across different sales modes follows the same variation pattern as PTIE and GTIE, that is, it is proportional to the corresponding retailers’ marginal profit. Only when retailers’ marginal profit is sufficiently large do they have the capacity to invest in product freshness detection efforts. This conclusion reminds suppliers that high-quality products require profit assurance throughout the entire supply chain. When selecting sales modes, it is essential not only to focus on sales volume and profit-sharing ratios but also to evaluate whether partners can provide sustainable profit support for the quality assurance system.

Proposition 4.

Comparison of greenness and preservation technology level of fresh agricultural products.

(1) The greenness size relationship of fresh agricultural products under the three sales modes is as follows.

- If , then is the largest; if , then is the largest; if , then is the largest.

- For specific comparisons, see Table A3 in Appendix D.

Proposition 4-(1) shows that the threshold for greenness level across different modes aligns with Proposition 3-(1). This is because greenness is primarily influenced by green technology investment, meaning greenness is also positively correlated with suppliers’ marginal profits. When the supplier achieves maximum marginal profits under the SP mode, selling fresh agricultural products through this channel enhances product greenness. Similarly, when suppliers’ marginal profits are maximized under the SH/SP mode, collaborating with the head/ordinary streamer can further enhance greenness. The supplier must select sales modes that ensure reasonable profit margins to achieve the green upgrade of fresh agricultural products.

(2) The preservation technology level size relationship of fresh agricultural products under the three sales modes is

When , , otherwise, .

When , , otherwise, .

When , , otherwise, .

From Proposition 4-(2), it can be seen that the preservation technology level is not only related to the marginal profit but also related to the degree of freshness detection effort. When and are greater than a certain threshold or is less than a certain threshold, choosing an e-commerce platform for sale can improve the preservation technology level. When and are greater than a certain threshold or is less than a certain threshold, cooperation with the head streamer can improve the preservation technology level; otherwise, the supplier should choose ordinary streamer mode. In other words, if the supplier’s marginal profit under the P/H/N sales modes is sufficiently high, or if the retailer’s preservation and detection effort is strong in these modes, the highest preservation technology level will be achieved in that corresponding mode. Conversely, if the retailer’s preservation effort in another sales mode is too low, it helps to identify which mode delivers the best preservation performance. This result also shows the importance of the level of fresh-keeping inspection. For example, CCTV’s “3·15” exposure of Oriental selection and the use of trough-head meat for braised plum vegetables sold in the live streaming room of three sheep exposed the problems of product selection and the inspection process in the live streaming industry. If the inspection investment is insufficient, the quality of fresh agricultural products will be difficult to guarantee (https://t.cj.sina.com.cn/articles/view/1988645095/768850e7020017iqx accessed on 15 December 2024).

6. Numerical Experiments

This section constructs an e-commerce livestreaming supply chain model involving a fresh agricultural product supplier and downstream retailers. The supplier faces a strategic choice between direct sales via an e-commerce platform or livestreaming sales. They may collaborate with a head or an ordinary streamer based on actual conditions. The numerical simulation study proceeds as follows:

(1) Real-world data collection. Based on industry research data, commission rates for fresh agricultural streamers cluster around three tiers: 10%, 15%, and 20% (https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1797572678270534247&wfr=spider&for=pc accessed on 15 December 2024). Head streamer slot fees can reach RMB 150,000 (https://pinkehao.com/infor/14214.html accessed on 15 December 2024), while ordinary streamers charge between RMB 50,000 and 100,000 (https://hangzhou.11467.com/info/10284825.htm accessed on 15 December 2024). Therefore, we assume a commission rate of for the head streamer and for an ordinary streamer. Research also indicates that head streamers possess significantly greater market influence than ordinary streamers. Following the measurement methodology [1], this study sets the influence coefficient for the head streamer as and for an ordinary streamer as . For comparative purposes, the e-commerce platform’s influence coefficient is set as an intermediate value between head and ordinary streamer, i.e., .

(2) Data Standardization. Due to issues such as inconsistent units and complex influencing factors in the raw data, all parameters require standardized conversion. After eliminating interference factors and performing unit conversions, the standardized data were substituted into the theoretical model for calculation. MATLAB R2022a software was employed for numerical simulation and visualization.

(3) Preliminary Results Analysis. Initial simulations showed that large disparities in parameter values (e.g., high pit fees relative to other parameters) obscured variation trends in key variables, hindering the visualization of core findings.

(4) Parameter Optimization Adjustments. To enhance simulation effectiveness, the parameter system was recalibrated while maintaining the original theoretical framework, referencing value standards from multiple literature sources [1,28,29,30]: . The optimized simulation results are as follows.

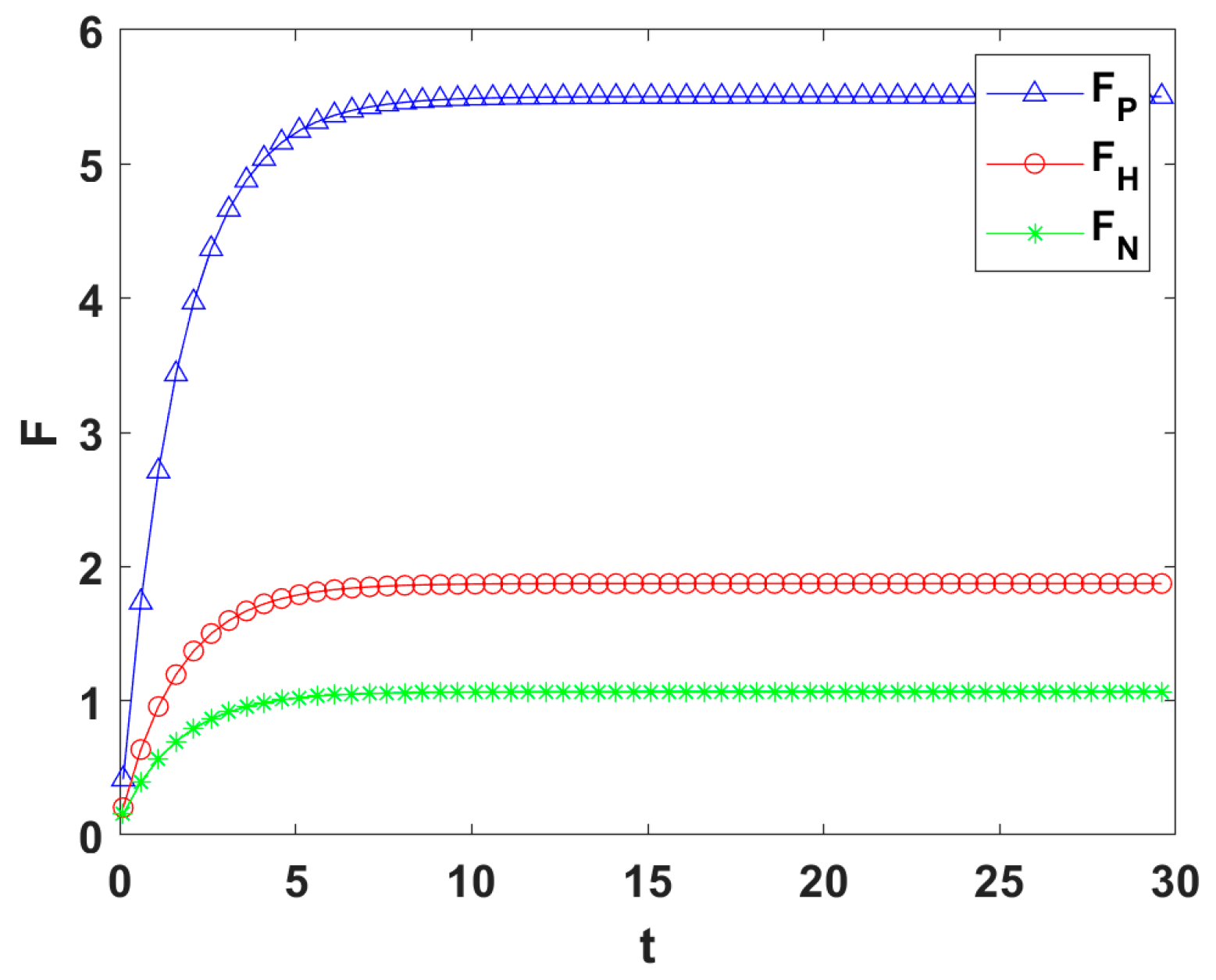

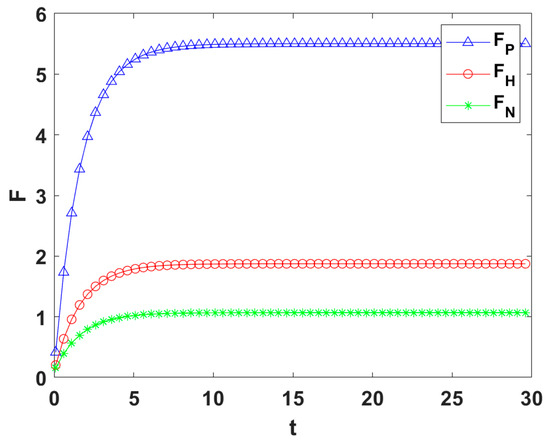

Figure 5 and Figure 6 illustrate that both freshness preservation technology level () and product greenness () tend to stabilize over time. Figure 5 indicates that freshness preservation technology is highest when collaborating with an e-commerce platform, followed by a head live streamer, and lowest with an ordinary streamer. This stems from the pressure exerted by the platform’s stringent inspection standards and the relatively stronger inspection capabilities of the head streamer. Figure 6 reveals that product greenness is maximized when partnering with a head streamer, followed by an e-commerce platform, and lowest with ordinary streamers. Combined with Figure 5, this suggests that under the e-commerce platform mode, suppliers may reduce investments in green technologies to maintain high standards of freshness preservation. From the supplier’s perspective, collaboration with high-standard e-commerce platforms or head streamers is advisable, provided they can effectively balance investments in freshness preservation and green technologies to avoid resource misallocation. When partnering with an ordinary streamer, the supplier should strengthen guidance and enhance their supply chain influence.

Figure 5.

The trajectories of the level of preservation technology over time.

Figure 6.

The trajectories of the level of green technology over time.

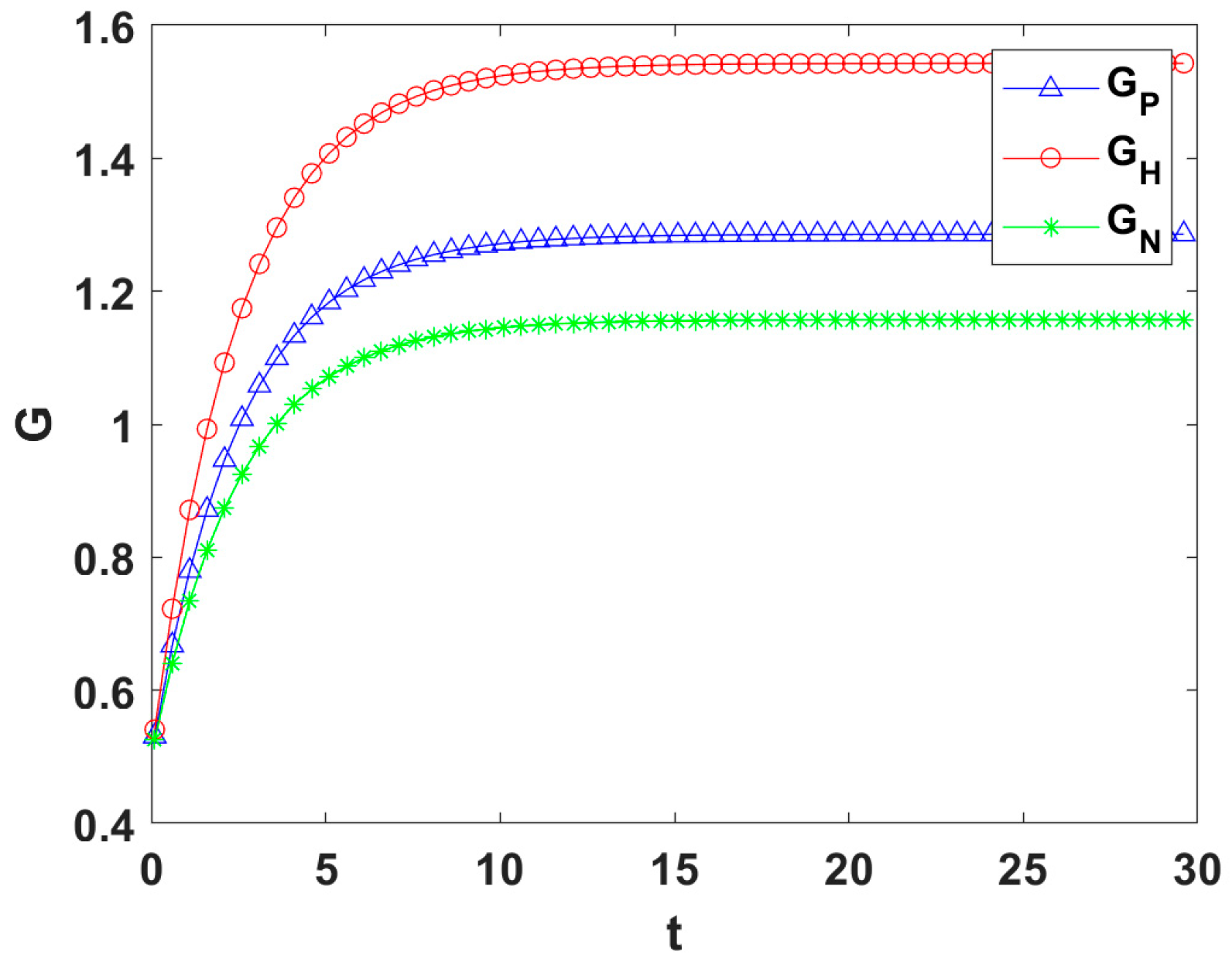

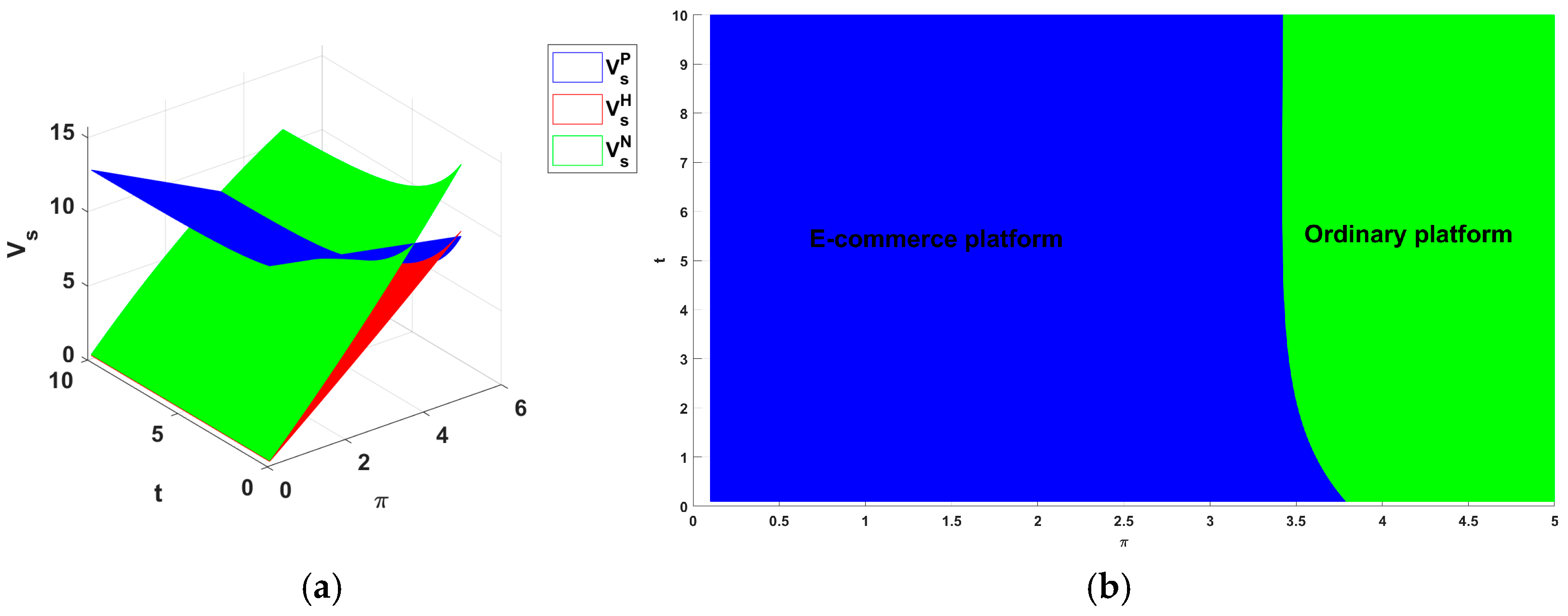

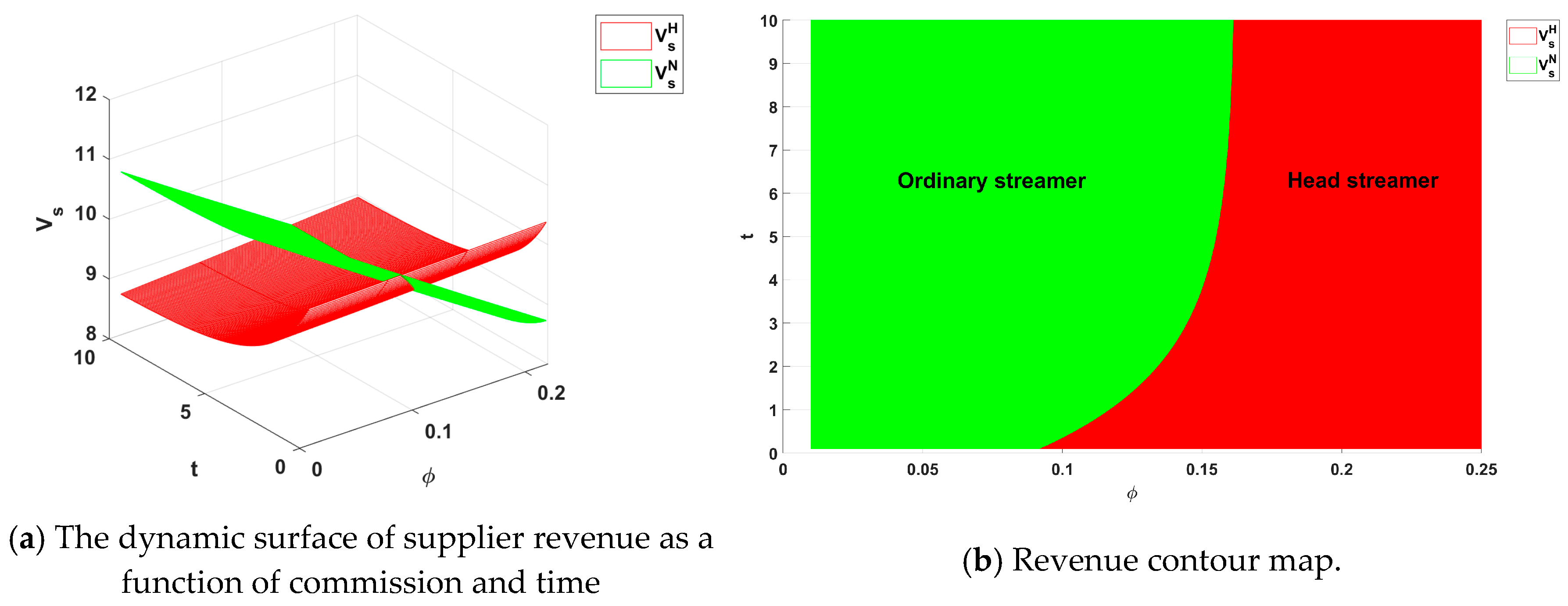

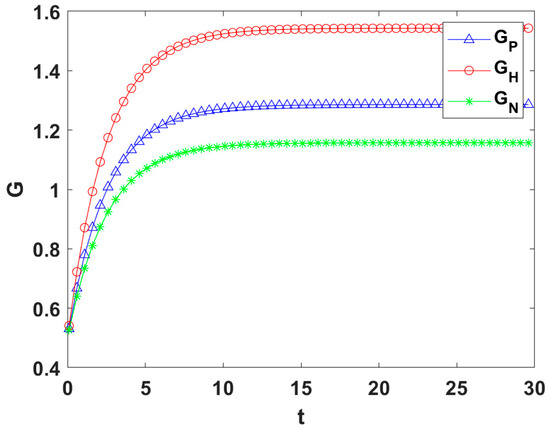

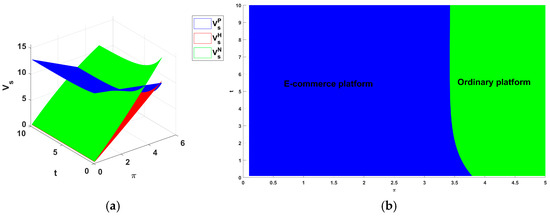

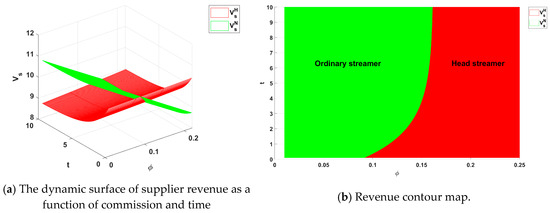

Figure 7 illustrates the influence of marginal revenue of downstream retailers (unified as for convenience of representation in the figure) and time in the supply chain on suppliers’ revenue. Figure 7a shows that as time passes, when becomes larger, the supplier’s profit from choosing an e-commerce platform becomes lower. This is because under the e-commerce platform mode, the platform and supplier make profits separately, and only represents the platform’s marginal profit. In reality, the e-commerce platform often reduces the supplier’s profit to obtain higher profits for itself. For example, fresh food group-buy platforms like Duoduo Grocery and Meituan Preferred keep lowering prices for suppliers to save costs (https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1742515595406018054&wfr=spider&for=pc accessed on 16 December 2024). Under the live streaming collaboration model, is the total marginal revenue of the live streaming channel and is shared between both parties. The higher is, the greater the supplier’s revenue, indicating a positive correlation between the two. Figure 7b further illustrates the revenue indifference curve () for the supplier choosing between the e-commerce platform and head streamer: when the marginal profit is relatively high, partnering with head streamer is more advantageous; when the marginal profit is relatively low, selecting the e-commerce platform is a more suitable choice. This finding substantiates Proposition 4, which posits that suppliers must determine their sales mode based on their marginal profit. Take the popular agricultural product “Yanshu 25” as an example. From being little known to being sold on Pinduoduo (A well-known e-commerce platform in China), its daily orders jumped to 4000–5000 and quickly expanded to many provinces across the country (https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MjM5NDY5MzE4MA==&mid=2652784463&idx=3&sn=5f22cfe8687383d5640a027054bd38a6&chksm=bd690e1c8a1e870ac8fbaea3736d15eff61f8d938c4593311bc5b391f0d12499a6bf9409330c&scene=27 accessed on 16 December 2024). This shows that the e-commerce platform model can effectively increase sales and help supplier makes profits.

Figure 7.

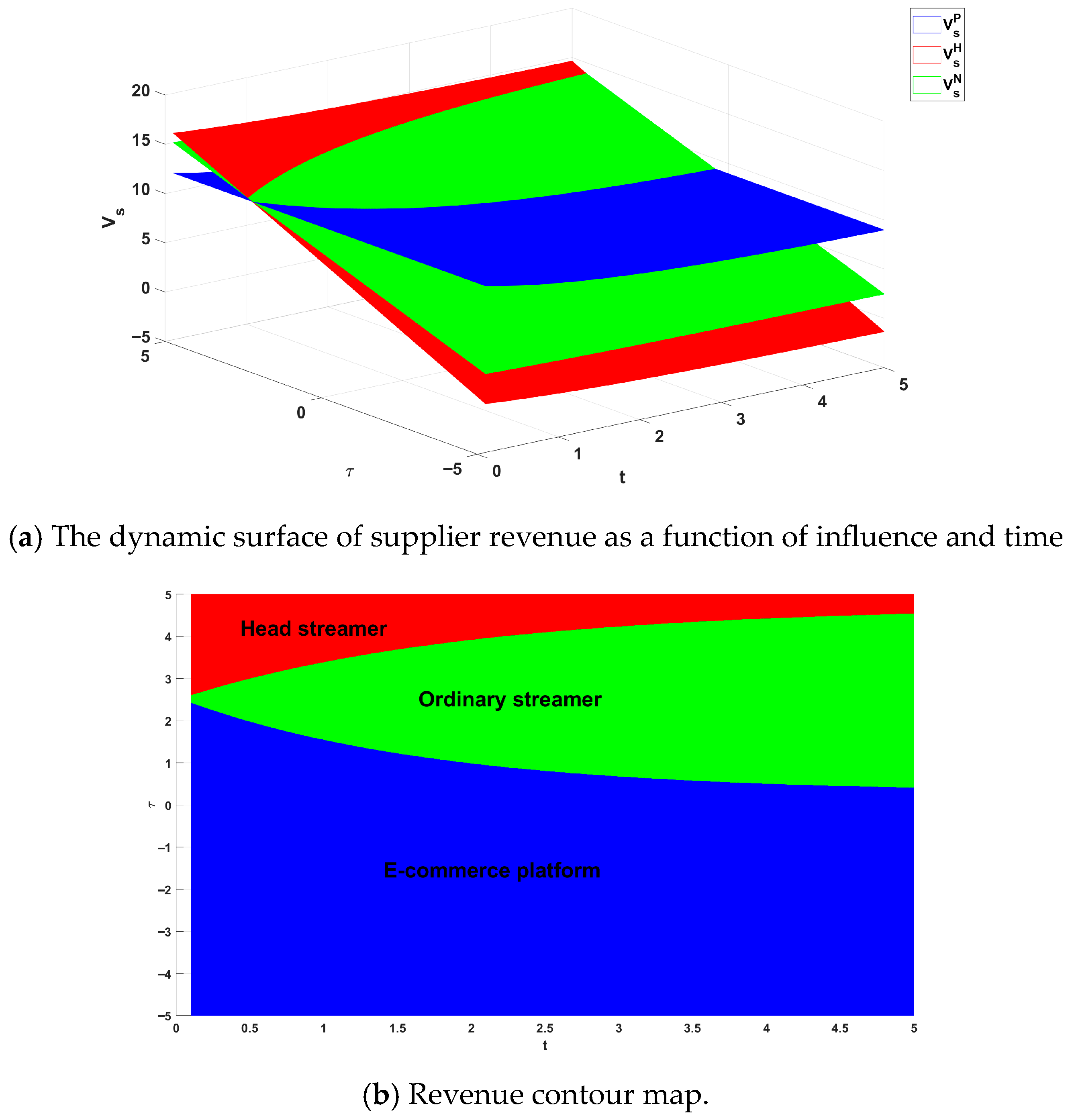

Influence of marginal revenue and time on supplier revenue (). (a) The dynamic surface of supplier revenue as a function of marginal revenue and time. (b) Revenue contour map.

Figure 8 demonstrates how supplier profits change when , namely the head streamer’s commission rate rises to 25% and pit fee increases to 1.5, while the ordinary streamer’s fees stay constant. The figure also presents the profit equal lines for and . The results indicate that for high marginal profits, the supplier should initially select an ordinary streamer and later transition to a head streamer. This pattern connects to two key factors: the supplier’s preservation technology level and greenness . Early in the process, when both and remain below the head streamer’s detection requirement, working with an ordinary streamer who has a lower standard proves more beneficial. As and improve and stabilize over time, eventually meeting the head streamer’s criteria, switching to head streamer mode becomes the better choice. Figure 9 shows the change in the supplier’s income when , namely, head streamer fees remain high while ordinary streamer fees decrease, and the profit of is given in Figure 9b. When the head streamer’s commission rate and pit fee substantially exceed those of an ordinary streamer, a supplier with high marginal profits should opt for an ordinary streamer. In summary, suppliers must conduct a comprehensive evaluation of streamer fees and revenue-sharing structures to prevent high commissions from eroding their profits.

Figure 8.

Influence of marginal revenue and time on supplier revenue (). (a) The dynamic surface of supplier revenue as a function of marginal revenue and time. (b) Revenue contour map.

Figure 9.

Influence of marginal revenue and time on supplier revenue (). (a) The dynamic surface of supplier revenue as a function of marginal revenue and time. (b) Revenue contour map.

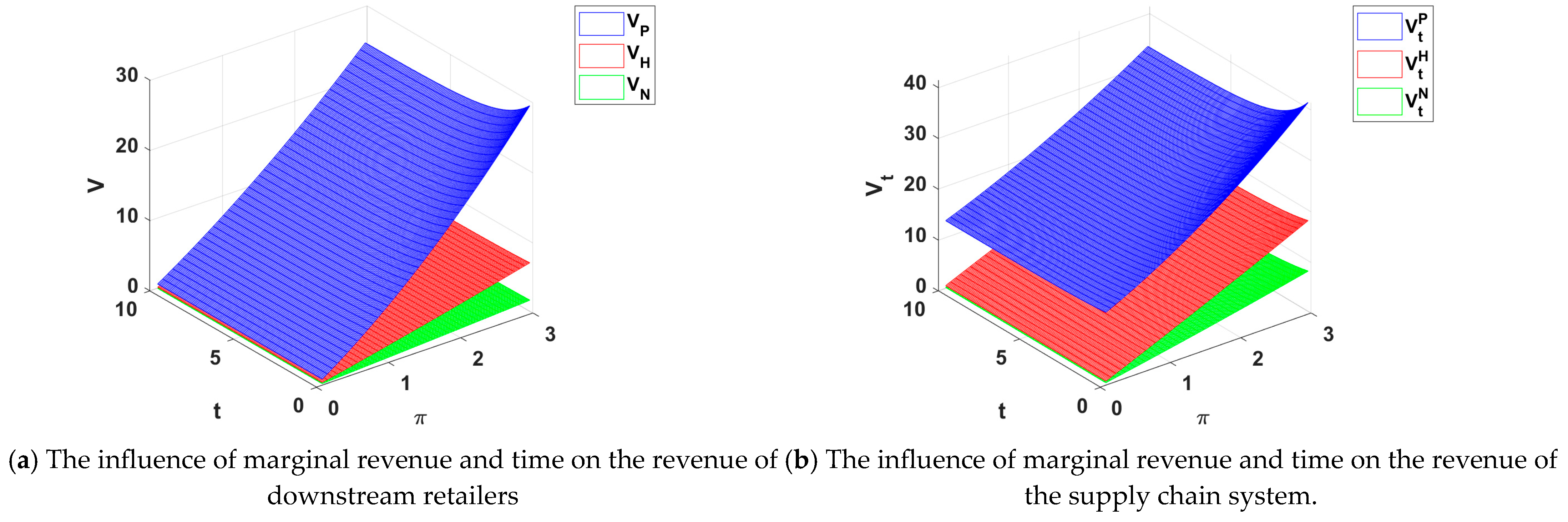

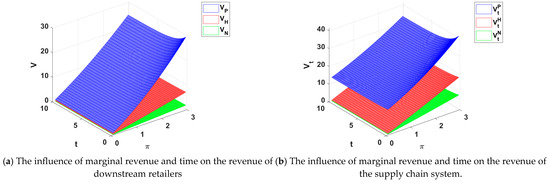

Figure 10a shows that the profit of the e-commerce platform, head streamer, and ordinary streamer decreases over time due to the perishability of fresh products, but increases as their marginal profit rises. As downstream retailers in the supply chain, their profits grow with their respective marginal revenues. Among them, the e-commerce platform shows the most significant profit growth. Figure 10b indicates that overall supply chain profit is positively correlated with marginal profit but negatively correlated with time. When the supplier opts to cooperate with the e-commerce platform, the system-wide profit shows an upward trend, as the platform’s significant profit increase offsets the decline observed in Figure 7a. These results suggest that suppliers should prioritize the e-commerce platform for selling fresh agricultural products when aiming to maximize overall supply chain benefits.

Figure 10.

The influence of marginal revenue and time on the revenue of downstream retailers and the supply chain system.

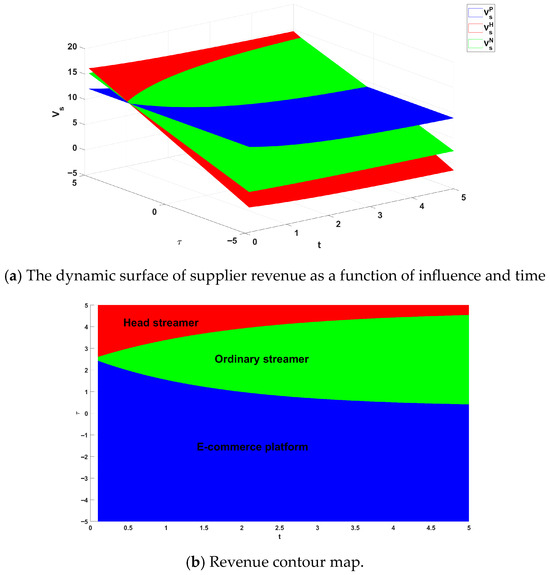

Figure 11a illustrates the dynamic impact of streamer influence on the supplier’s channel selection over time. For comparison, we standardize the streamer’s influence as . As the streamer’s influence increases, the supplier’s profit rises accordingly because greater influence enhances fan effects, attracts more traffic, boosts sales, and ultimately increases the supplier’s earnings. Figure 11b shows that the supplier’s optimal choice varies with different influence levels. The supplier benefits most from collaborating with a head streamer only when the influence is high. At medium influence levels, partnering with an ordinary streamer proves better. When the influence is low, the supplier achieves higher profits by opting for e-commerce platform sales. For example, early pioneers in online fresh food, such as Dingdong Maicai and JD Maicai, attracted suppliers by developing front-warehouse models (https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1760893110791962433&wfr=spider&for=pc accessed on 16 December 2024). With the rise of live-streaming e-commerce, many fresh food platforms began inviting influencers to promote sales. For example, JD invited celebrity Wang Xiaoli to livestream sell hairy crabs, generating 7.13 million RMB in GMV (https://cj.sina.com.cn/articles/view/6494755109/1831e192500101ecua accessed on 16 December 2024). In conclusion, when the streamer’s influence is strong enough to attract consumers, the supplier should choose streamer collaboration. When the influence remains insufficient to drive traffic, the supplier should opt for e-commerce platform sales.

Figure 11.

Influence of streamer influence and time on supplier’s income.

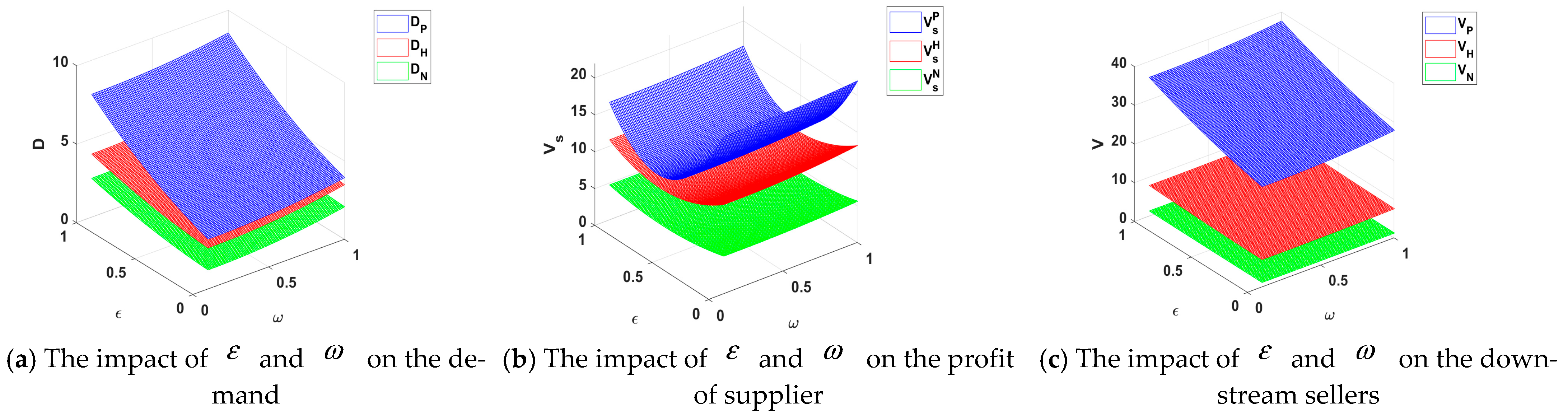

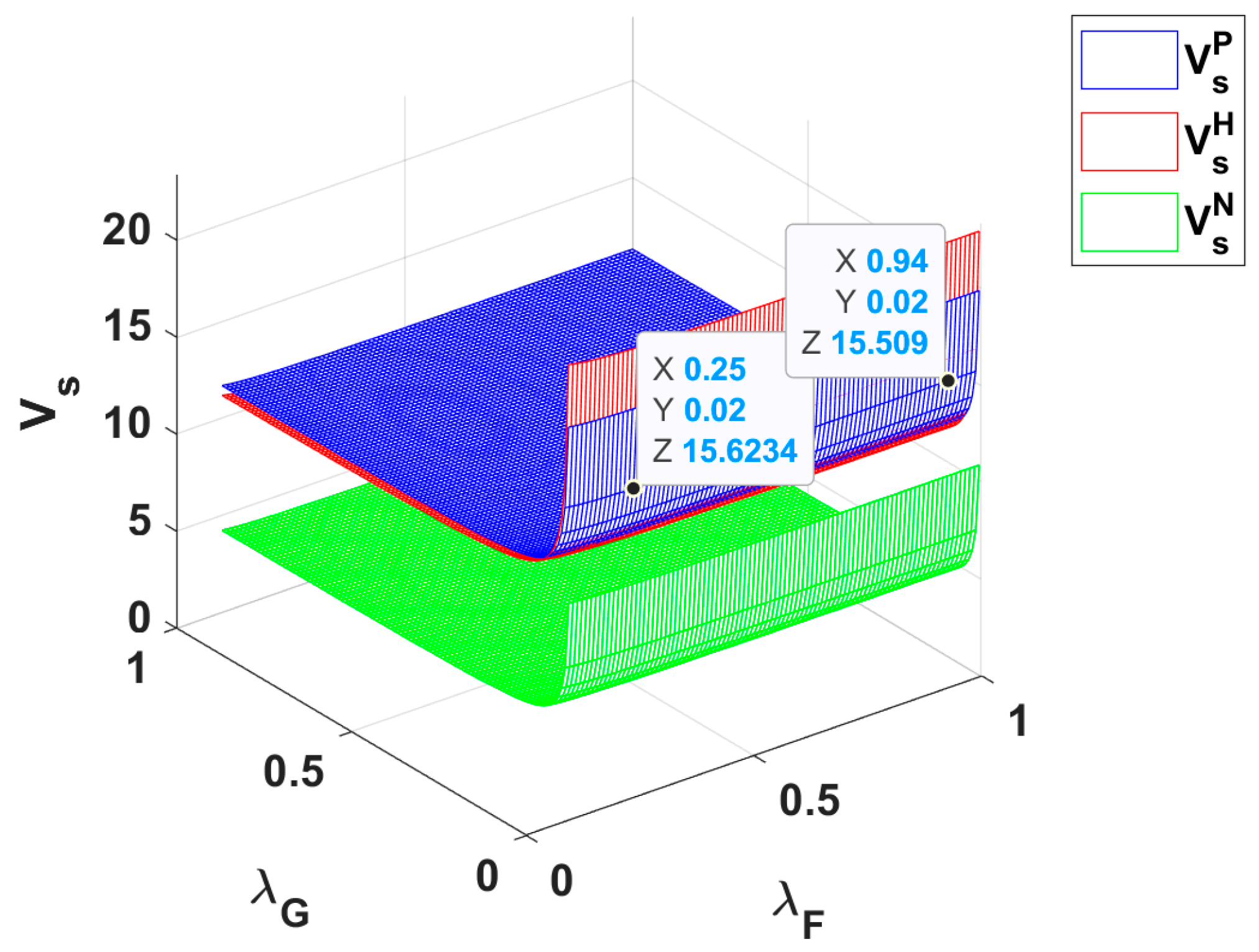

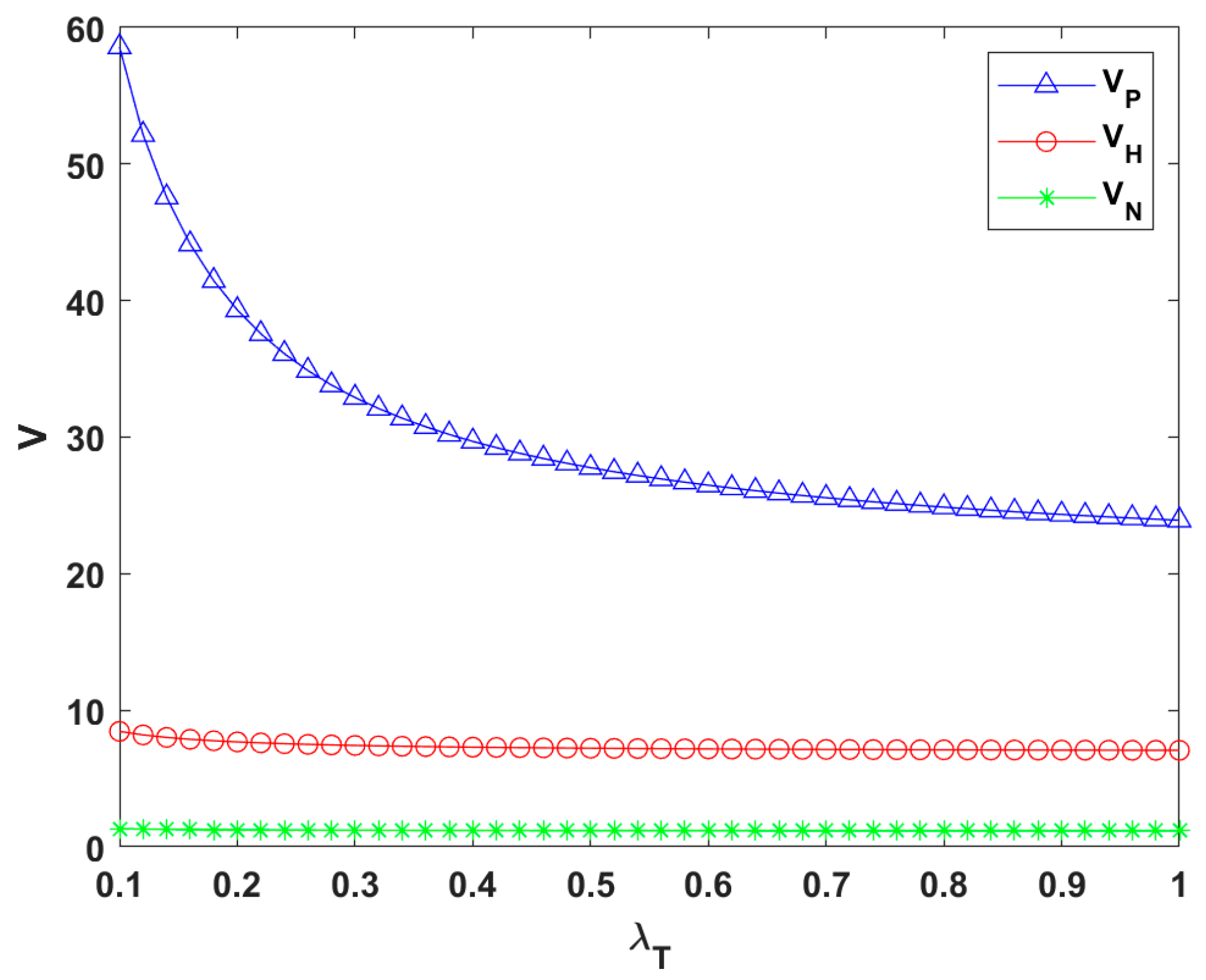

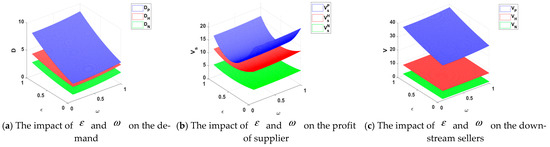

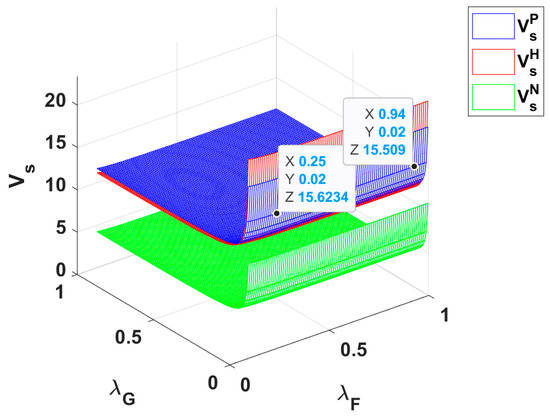

Figure 12 examines how consumer preferences for the preservation technology level and greenness affect demand, supplier profits, and downstream retailers’ profits. To make comparisons clearer, we use t = 0.3 as an example for analysis.

Figure 12.

The impact of and on the demand, profit of supplier, and downstream sellers.

Figure 12a shows that market demand D increases with both and across all three channels, but grows more significantly with than , indicating consumers value preservation technology more. Figure 12b reveals that supplier profits under all three channels first decrease, then increase with rising , with this pattern being most pronounced for . This phenomenon occurs because initial investments in preservation technology may not be immediately recouped; profits subsequently rise as market preference for fresher products intensifies. Additionally, supplier profits under all channels increase slightly with , suggesting that improving greenness has a limited impact on boosting profits. Figure 12c demonstrates that downstream retailers’ profits increase with both and . The growth is strongest for relative to , while increases of and are smaller. All three profits show insignificant growth trends with . Based on these findings, we advocate for the following strategic implications: suppliers should prioritize freshness preservation technology as their core investment focus while adopting a measured development strategy for green technologies. Retailers should emphasize promoting high-preservation products and establish incentive systems tied to freshness level. Collectively, all supply chain participants must recognize that advancements in freshness preservation technology yield greater tangible returns compared to solely pursuing greenness.

Figure 13 shows the influence of preservation technology level preference and the influence coefficient of FDE on demand on FDE. It can be seen that can improve FDE more than , and the FDE of e-commerce platform is the most obvious with the growth of . Therefore, the e-commerce platform should focus on demonstrating the returns generated by enhanced testing technologies to all parties in the supply chain. This will enable the supplier to clearly recognize the value of detection, thereby incentivizing them to increase their commitment to freshness preservation technology.

Figure 13.

The impact of and on the freshness detection level.

Based on the findings in Figure 14, green technology investment costs () exert the most significant impact on supplier profits, with cost increases leading to a sharp decline in returns. In contrast, the effect of freshness preservation technology investment costs () on supplier profits is relatively limited, and as shown in Figure 11a, consumers place greater emphasis on freshness preservation technology. Therefore, a supplier cannot arbitrarily reduce the costs associated with freshness testing, a factor that significantly influences preservation technology levels. This conclusion is further substantiated by Proposition A1-(2).

Figure 14.

Influence of GTIE and FTIE cost factors on supplier’s profit.

As shown in Figure 15, for downstream retailers, increased freshness detection costs markedly reduce their profits, a phenomenon particularly pronounced under the e-commerce platform mode.

Figure 15.

Influence of FDE cost coefficient on downstream sellers profit.

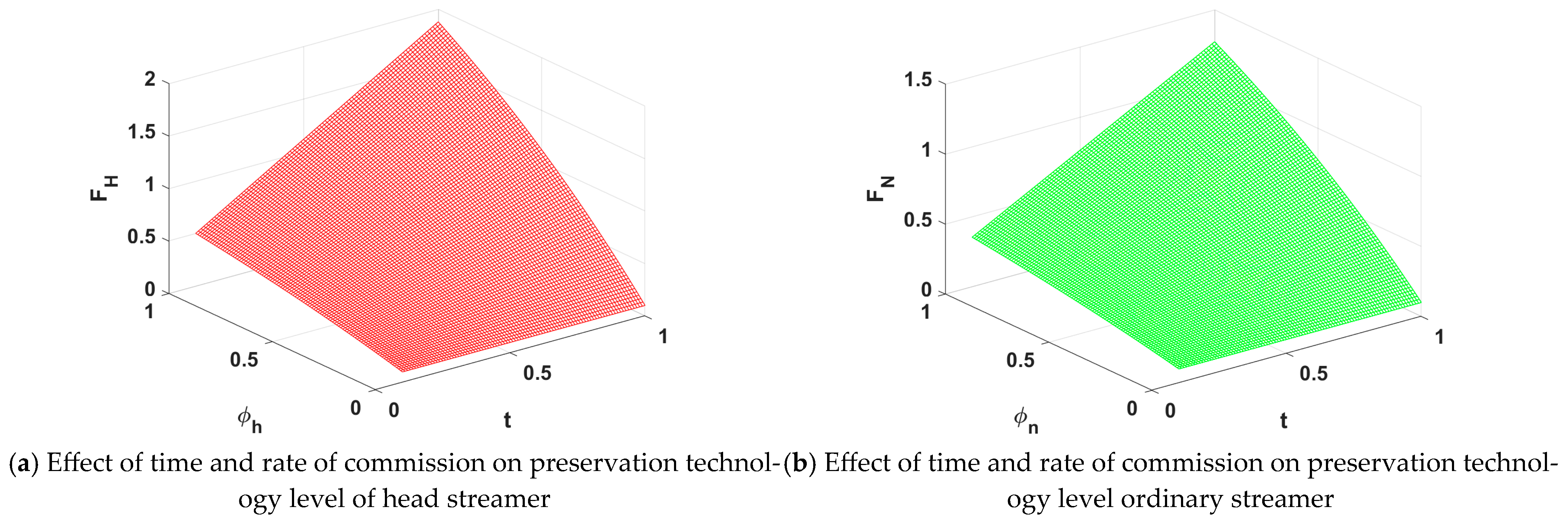

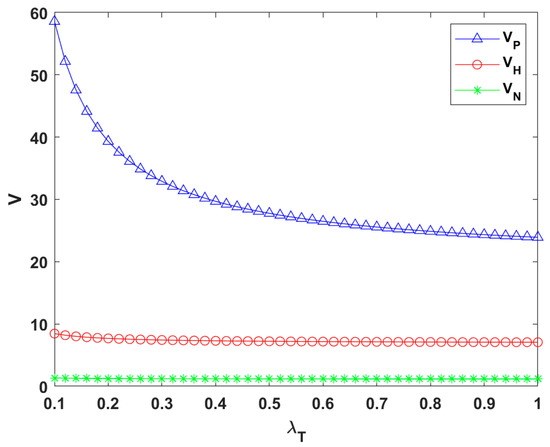

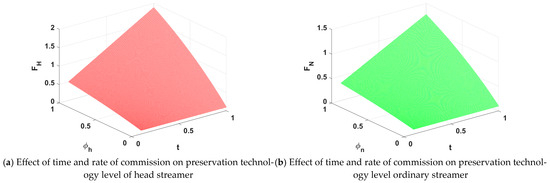

Figure 16 illustrates that the preservation technology level exhibits a positive relationship with the streamer’s commission rate over time, showing an accelerating growth trend. This pattern indicates that increasing the streamer’s commission rate provides a positive incentive for the supplier to improve preservation technology. Since the streamer is responsible for preservation quality checks, a higher commission encourages greater investment in preservation testing, which in turn motivates the supplier to enhance their preservation technology. The head streamer mode leads to a significant increase in the preservation technology level compared to the ordinary streamer mode, suggesting that the head streamer is more effective in driving preservation technology advancements. This difference can be attributed to the stronger bargaining power held by head streamers, which enables them to exert greater pressure on supplier to meet higher preservation standard.

Figure 16.

Effect of time and rate of commission on preservation technology level.

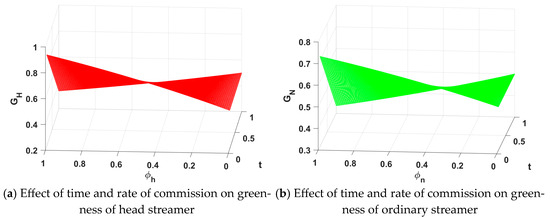

Figure 17 illustrates that over time, a lower commission rate leads to an effective increase in the greenness level, whereas a higher commission rate results in a decline. As indicated Figure 15, this occurs because high streamer commissions compress the supplier’s profit margin. To maintain high preservation technology standard under such conditions, the supplier may reduce investment in green technology, thereby lowering the greenness level. In the head streamer mode, the decline in greenness occurs more gradually. This can be attributed to the head streamer’s strong influence and higher sales volume, which generate economies of scale. These economies enable the supplier to allocate relatively more resources to green technology compared to other cost items. As a result, the adverse effect of a high commission rate on greenness investment is mitigated, helping to moderate the decline in greenness.

Figure 17.

Effect of time and rate of commission on greenness.

As shown in Figure 18, the commission rate significantly influences suppliers’ choice of live streamers. At a lower commission rate, the ordinary streamer yields higher profits for the supplier, but this advantage diminishes rapidly as the rate increases. Conversely, supplier profits under the head streamer mode steadily increase with rising commission rate. This phenomenon stems from the differing potential of the two streamer types. For ordinary streamers with limited capabilities, a higher commission rate struggles to incentivize increased sales, ultimately harming supplier profits. For head streamer, however, a high commission rate effectively mobilizes their superior marketing prowess. By substantially boosting sales volume, they offset suppliers’ commission expenses, ultimately driving supplier profit growth. Therefore, when the commission rate is high, priority should be given to collaborating with the head streamer, leveraging their strong sales conversion capabilities to safeguard supplier profits.

Figure 18.

Effect of time and rate of commission on profit of supplier.

7. Model Expansion

Considering that in reality, fresh products are often sold together in e-commerce platforms and live streaming rooms, this paper extends the original model to help fresh agricultural suppliers make a choice between single-channel or dual-channel sales.

We formulate two distinct dual-channel configurations: simultaneous distribution via the e-commerce platform and a head streamer (P+H), and via the e-commerce platform and an ordinary streamer (P+N). In reality, the cost of a fresh supplier cooperating with both the head streamer and the ordinary streamer is too high, and there are few cases, so this paper will not consider it.

As mentioned above, the assumptions of preservation technology level and greenness remain unchanged. However, the demand functions are adapted to characterize the P+H and P+N scenarios. Referring to previous literature [41,42], we set the demand function here as

Among them, we divide the potential market demand of the P+H channel into two parts by influence. The potential market demand ratio of the e-commerce platform is , and the potential market demand ratio of the head streamer is .

Because it is difficult to discuss the profit of the downstream sellers in the dual channel, and this paper analyzes it from the perspective of the supplier, we only discuss the change in the supplier’s profit here, and the supplier’s profit can be obtained from Equations (20) and (21) as follows.

After calculation, the profit of the supplier in the P+H channel is

Coefficient terms (such as , etc.). See the Appendix C.

Similarly, the demand functions of the P+N channel are

Similarly, we divide the potential market demand of the P+N channel into two parts by influence. The potential market demand ratio of the e-commerce platform is , and the potential market demand ratio of the ordinary streamer is .

Then, the profit of suppliers in the P+N channel is

After the calculation, the profit of the supplier in the P+N channel is

Coefficient terms (such as , etc.). See the Appendix C.

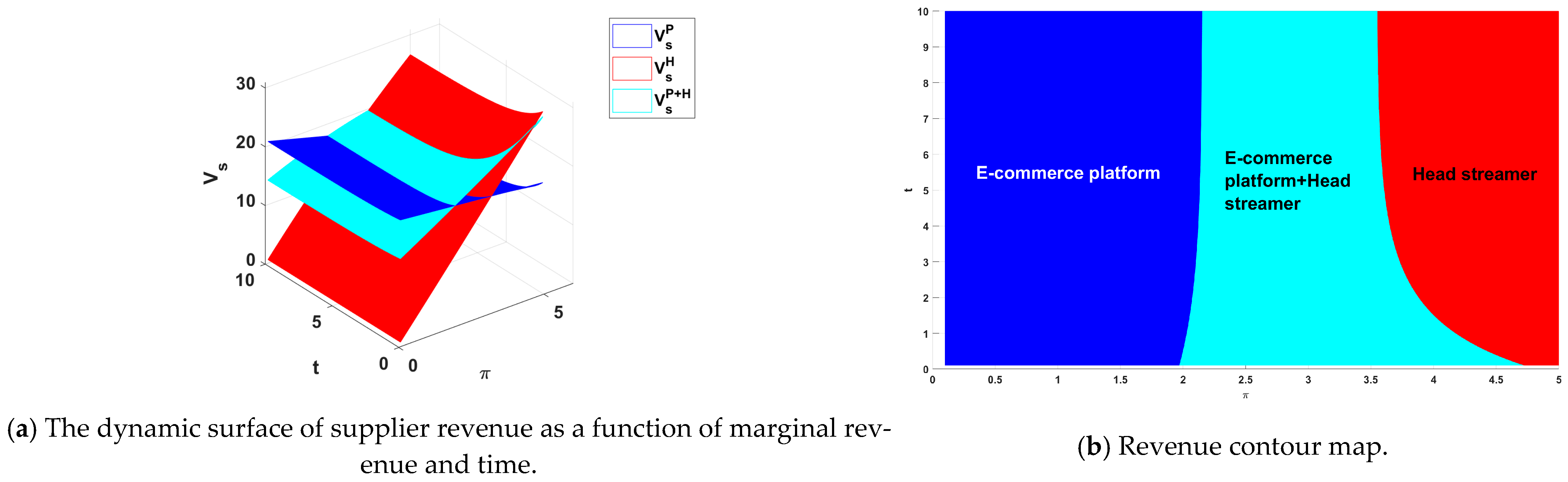

Consistent with the above, because the optimal solutions of suppliers’ profits cannot be compared by mathematical operations, we use numerical analysis to compare them. However, unlike the previous paper, in order to make the distribution ratio of potential demand greater than 0, we no longer use as the benchmark value here, but let , and other parameters are consistent with Section 6.

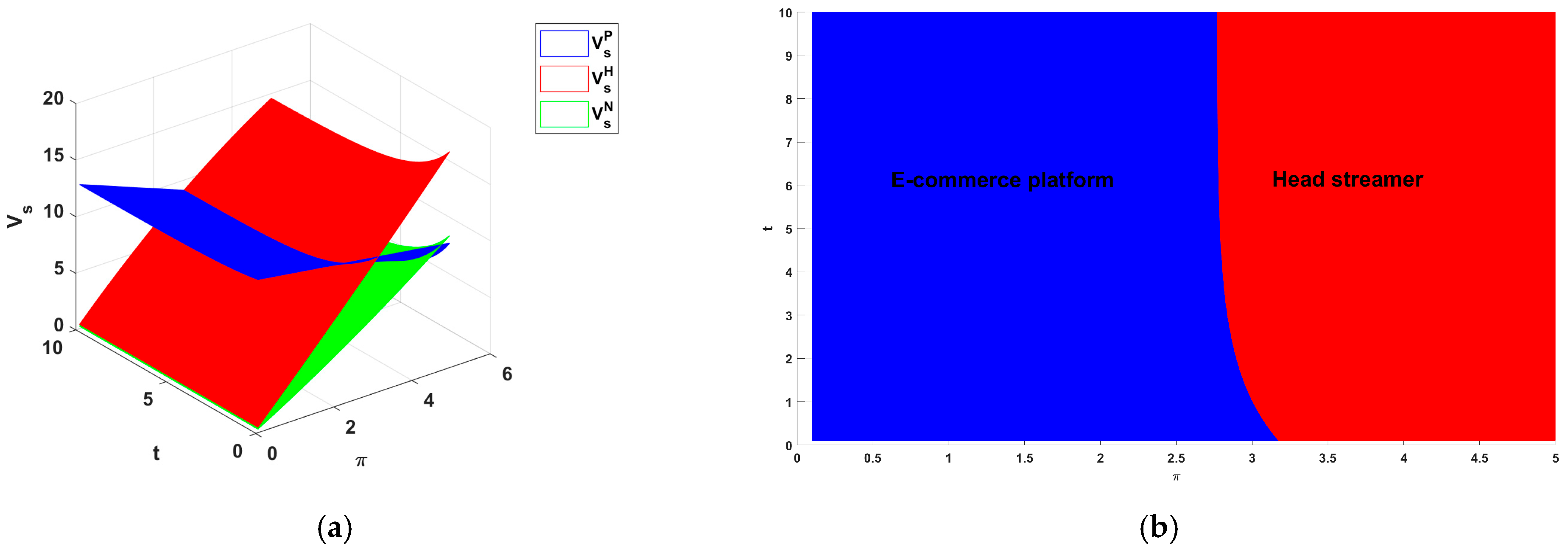

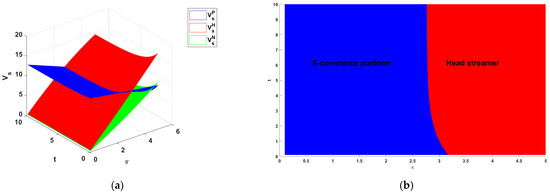

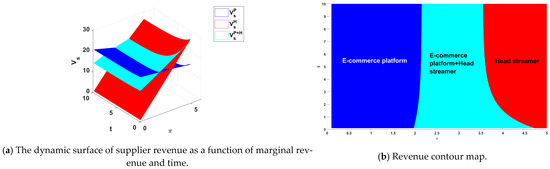

As illustrated in Figure 19, the supplier’s channel selection depends on the size of the marginal profit; the marginal profit exists in different ranges, and the profit size of the supplier is also different, which can be clearly seen from the head view on the left. When the marginal profit is in the middle and high, suppliers can make more profits by choosing the dual channel of e-commerce platform and head streamer, while suppliers should choose the head streamer and e-commerce platform, respectively, when the marginal profit is extremely large and small. This pattern stems from the inherent logic that marginal profit determines supplier profitability: moderate marginal profit provides the supplier with the residual capacity to engage in dual-mode sales; under lower marginal profit, opting for cooperation with a relatively low-cost e-commerce platform is more conducive to profitability; extremely high marginal profit enables the supplier to bear the high costs associated with the head streamer and achieve higher returns.

Figure 19.

The impact of and t on the profit of the supplier in single-channel and dual-channel (P+H) modes.

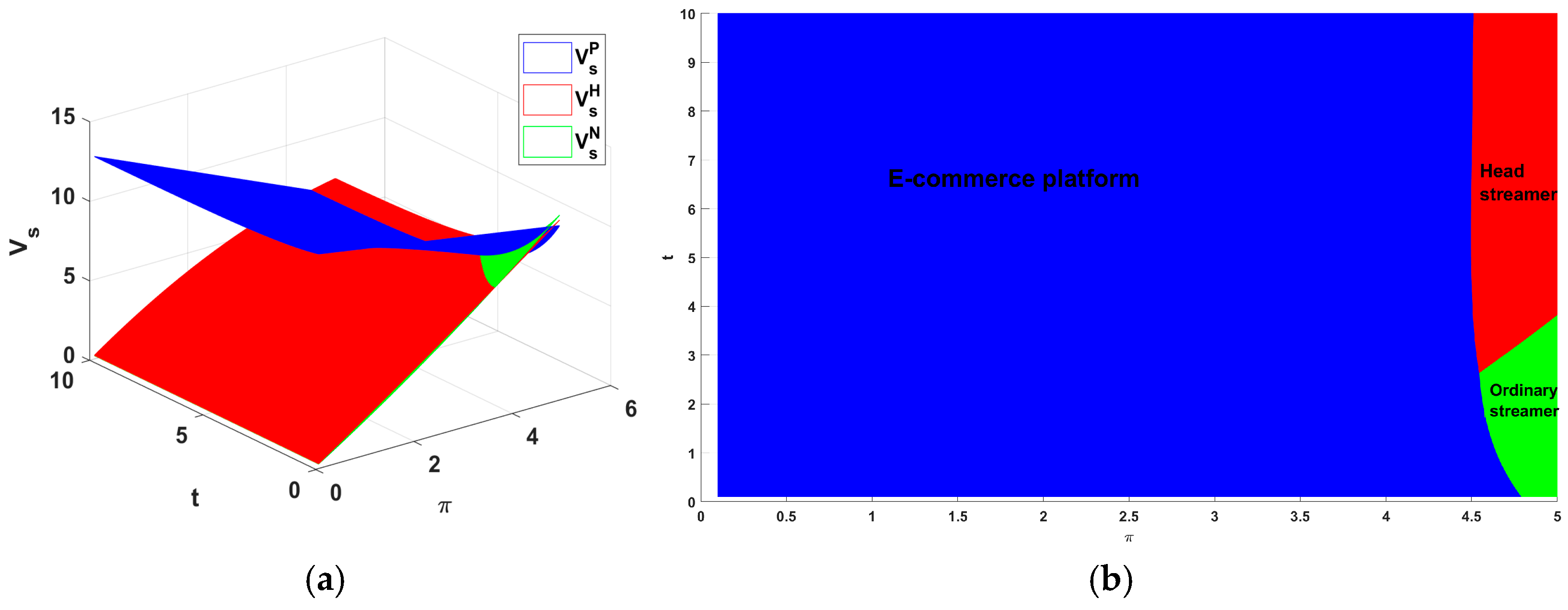

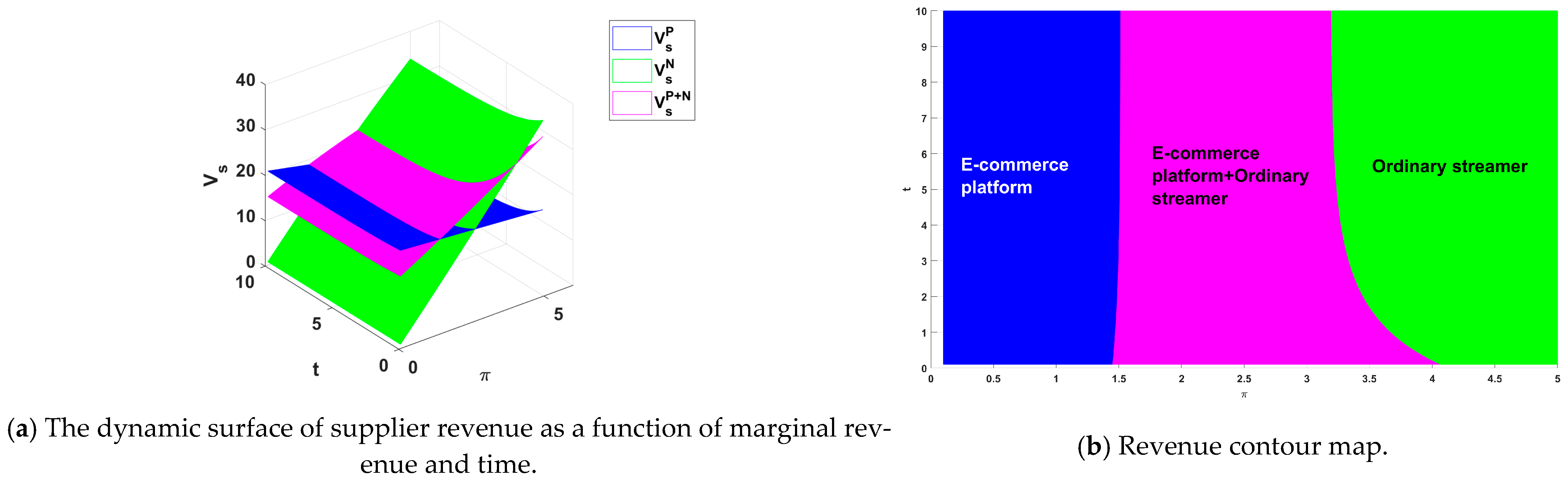

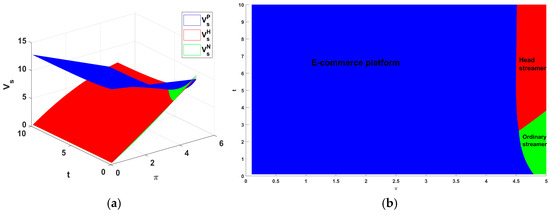

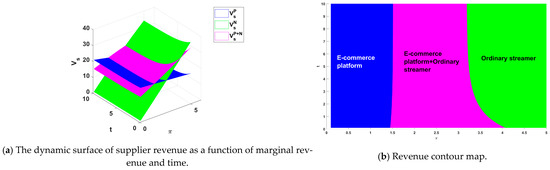

Similarly, as illustrated in Figure 20, the supplier’s channel selection is contingent upon varying levels of marginal profit. As can be seen from the head view on the left, the marginal profit is also in the middle, and the supplier has the spare capacity to choose the dual-channel mode of e-commerce platform and ordinary streamer; however, compared with Figure 12, this interval is smaller because the commission of the ordinary streamer is lower and the cost of the supplier is lower, so the marginal profit threshold of supplier’s choice of ordinary streamer is smaller than that of head streamer. However, compared with Figure 12, the marginal profit condition of choosing the P+N channel is lower than that of the single e-commerce platform channel, which shows that the P+N channel is the easier selection for the supplier than the P+H channel.

Figure 20.

The impact of and t on the profit of the supplier in single-channel and dual-channel (P+N) mode.

8. Conclusions and Management Insights

The rise of live streaming e-commerce provides fresh agricultural suppliers with new sales channel options. How to select the appropriate sales channel to maximize profits has become an urgent problem for suppliers to solve. This paper constructs a fresh agricultural supply chain consisting of a supplier and downstream retailers. We consider three decision variables: the supplier’s preservation technology investment effort, green technology investment effort, and downstream retailers’ freshness detection effort. The study establishes state equations for preservation technology level and greenness, examining the profits of supply chain members under three sales modes: e-commerce platform sales, head streamer sales, and ordinary streamer sales. Using differential game theory methods, we build a Stackelberg game model between the supplier and downstream retailers with dynamic equilibrium conditions. The research systematically evaluates the trade-offs of the three sales modes under varying conditions, providing reasonable recommendations to help fresh agricultural suppliers choose the most suitable sales mode. The study draws the following conclusions.

(1) Investment levels and marginal profits: The preservation technology investment effort (PTIE), green technology investment effort (GTIE), and freshness detection effort (FDE) depend on the marginal profit of each decision-maker. This indicates that the profit-sharing mechanism serves as a core lever for incentivizing technological upgrading in the supply chain. If downstream retailers can ensure the supplier’s marginal profit space through well-designed allocation schemes, it will directly promote long-term investment in preservation and green technologies.

(2) Preservation technology level and greenness: Greenness is mainly determined by marginal profit. Channels with higher marginal profits achieve higher greenness. Preservation technology level is jointly influenced by marginal profit and freshness detection costs. When the e-commerce platform’s freshness detection cost exceeds a certain threshold, or when the streamer’s freshness detection cost falls below a certain threshold, choosing the e-commerce platform better improves preservation technology. This provides a theoretical basis for suppliers to select appropriate channels according to different quality objectives. This study not only identifies the optimal sales mode for maximizing preservation technology but also determines the best choice for maximizing product greenness, filling a gap in existing literature.

(3) Supplier profits: During the low-profit stage, the e-commerce platform is more conducive to securing supplier revenue due to its stable channel characteristics. As profit margins increase, streamer-based models become a potentially advantageous option, but a rigorous evaluation of the alignment between streamer influence and cost structure is essential. If the commission and slotting fees of a head streamer significantly exceed the traffic premium they bring, then an ordinary streamer or platform-based model may instead offer greater sustainable profitability.

(4) Channel influence: Supplier must consider both the streamer’s influence and cost-effectiveness. When the head streamer’s influence reaches the leading level in the industry, collaboration may create significant scale effects. However, if influence is insufficient to offset costs, ordinary streamers may be superior, and with low influence, the traditional e-commerce platform’s advantages should be prioritized for profit maximization. Therefore, suppliers should establish an influence cost-balanced evaluation framework to avoid compromising profit resilience in pursuit of traffic.

(5) Consumer preferences: The study confirms that consumer preference for preservation technology significantly outweighs their focus on green attributes, which may lead suppliers to systematically prioritize “preservation over greenness” in investment decisions. This finding suggests that advancing green transformation requires market education or external incentives.

(6) Commission impact: High commission rates, while incentivizing streamers to enhance quality control and promote preservation technology, may crowd out resources for green technology investment. Comparisons reveal that the head streamer model exerts a relatively weaker inhibitory effect on green investment, indicating its superior comprehensive coordination capability.

(7) Dual-Channel Considerations: Incorporating a dual-channel mode of e-commerce platform and live streaming, the optimal choice for the supplier also needs to be decided according to the marginal profit of downstream sellers. Generally speaking, compared with cooperation with a single streamer (head streamer or ordinary streamer), the marginal profit condition of choosing the P+H channel is higher than that of choosing the P+N channel. This finding provides differentiated channel entry pathways for suppliers of varying scales: suppliers with weaker profit foundations may prioritize the “platform + ordinary streamer” model to achieve a more stable sales structure, while suppliers with sufficient profit margins can directly adopt the “platform + head streamer” combination to secure traffic support.

Based on the findings of this study, integrated management insights are proposed for all relevant stakeholders. Suppliers should adopt refined channel management strategies, initially building a sales foundation through e-commerce platforms and then introducing live streaming channels as marginal profits increase, while carefully balancing streamer influence with associated costs. Given the observed stronger consumer preference for freshness over environmental sustainability, suppliers should prioritize product freshness while steadily advancing green transformation, flexibly combining “platform + head streamer” models for high-value-added products and “platform + ordinary streamer” models for mass-market goods. Streamers should strengthen quality-control collaboration with suppliers, establish transparent and traceable product information disclosure mechanisms, and optimize commission structures to encourage sustainable supply chain investments. E-commerce platforms should provide data-driven tools to monitor freshness and green performance, design incentives that reward high-quality and sustainable practices, and introduce credible certification labels to support informed consumer choice. Consumers can promote market shifts toward greater sustainability by prioritizing products with verified freshness and credible green credentials in their purchasing decisions. Industry and policymakers should implement targeted green subsidies and tax incentives, establish tiered quality-control standards linking freshness inspection, streamer credit ratings, and platform oversight to create a market-driven virtuous cycle, and foster third-party verification systems to enhance the credibility of quality and environmental claims in live streaming commerce. Such coordinated efforts can steer the fresh agricultural live streaming supply chain toward greater transparency, efficiency, and sustainability.

Our study acknowledges several key limitations that provide avenues for future research. First, the reliance on a linear and additive demand function, while analytically tractable, may oversimplify the potential complementary or substitutive interactions between preservation efforts and product greenness observed in real markets. Future work could introduce nonlinear demand specifications or explicit interaction terms to examine how such dynamics influence channel choice and strategy, thereby enriching the theoretical foundation of live streaming e-commerce. Second, the model assumes fixed decay rates, constant costs, and stable influence coefficients, which may not reflect real-world variability in consumer preferences or streamer performance. Extending the framework to incorporate stochastic or time-varying parameters would enhance its realism and robustness. Moreover, a key limitation is that our model does not systematically compare hybrid channel strategies. Future work could extend the framework to examine synergies or competition between combined sales modes. Lastly, as a theoretical modeling study, our conclusions lack empirical validation. While the model offers meaningful analytical insights, its practical relevance would be strengthened by future empirical or case-based verification. Additionally, the results may lack generalizability, as the model is built specifically on the Chinese live streaming e-commerce context. Future research could empirically validate the model, adopt alternative demand specifications, or extend it to settings with multiple suppliers or competing platforms. Such efforts would enhance both the generalizability and practical relevance of the findings.

Author Contributions

N.A.: Investigation, Methodology, Data curation, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft. L.Z.: Methodology, Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Fund of China (24BGL098).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the support from the National Social Science Fund of China (24BGL098).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

E-Commerce Platform Model Solution

The HJB equation of the supplier is

where is a function of the supplier’s revenue value, represents the partial derivative of the value function to , represents the partial derivative of the value function to . The first-order condition for is calculated from (A1), and the supplier’s optimal freshness improvement effort is

The supplier’s optimal greenness improvement effort is

Furthermore, the HJB equation for the E-commerce platform can be obtained as

Similarly, is the profit value function of the E-commerce platform, and denotes the partial derivative of the value function with respect to , denotes the partial derivative of the value function with respect to .

Substituting into (A4) and solving its first-order condition on , we find that the best freshness detection effort of the E-commerce platform is

Then substituting and into (A1) and (A4), we obtain

Let , the undetermined coefficient method can get

Substitute into , respectively, we get

Substituting it into the state equation, the trajectory equation can be obtained as follows

Proof of Corollary 2.

Appendix B

Head Streamer Model Solution

The HJB equation of the supplier is

where is a function of the supplier’s revenue value, represents the partial derivative of the value function to , represents the partial derivative of the value function to . The first-order condition for is calculated from (A8), and the supplier’s optimal freshness improvement effort is

The supplier’s optimal greenness improvement effort is

Furthermore, the HJB equation for the Head streamer can be obtained as

Similarly, is the profit value function of the Head streamer, and denotes the partial derivative of the value function with respect to , denotes the partial derivative of the value function with respect to .

Substituting into (A11) and solving its first-order condition on , we find that the best freshness detection effort of the Head streamer is

Then substituting and into (A8) and (A11), we obtain

Let , the undetermined coefficient method can get

Substitute into , respectively, we get

Substituting it into the state equation, the trajectory equation can be obtained as follows

Proof of Corollary 4.

Appendix C

Ordinary Streamer Model Solution

The HJB equation of the Ordinary streamer is

where is a function of the supplier’s revenue value, represents the partial derivative of the value function to , represents the partial derivative of the value function to . The first-order condition for is calculated from (A15), and Ordinary streamer’s optimal freshness detection effort is

Furthermore, the HJB equation for the supplier can be obtained as

Similarly, is the profit value function of the Head streamer, and denotes the partial derivative of the value function with respect to , denotes the partial derivative of the value function with respect to . Substitute in (A17) and get the first derivative of . The supplier’s optimal greenness improvement effort is

The supplier’s optimal greenness improvement effort is

Then substituting and into (A15) and (A17), we obtain

Let , the undetermined coefficient method can get

Substitute into respectively, we

Substituting it into the state equation, the trajectory equation can be obtained as follows

Proof of Corollary 4.

The extension of the model proof follows a similar procedure to that presented in Appendix A, Appendix B and Appendix C.

In the expansion model, the coefficient terms of the profit function are as follows:

- (1) P+H model

- (2) P+N model

Appendix D

Proof of Proposition 4-(1).

The comparison of PTIE:

,

, Therefore when

,

; When

,

;

,, Therefore when

,

; When

,

;

,

,

, Therefore when

,

; When

,

;

The comparison of GTIE:

,

, Therefore when

,

; When

,

;

,

, Therefore when

,

; When

,

;

, , , Therefore when , ; When , .

The specific comparison is shown in the table below.

Table A1.

Optimal mode Selection of PTIE and GTIE.

Table A1.

Optimal mode Selection of PTIE and GTIE.

| Conditions | Size relation of PTIE/GTIE () | Optimal Mode Selection | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | ||||

| P | ||||

| — | ||||

| N | ||||

| H | ||||

| — | ||||

| H | ||||

| N | ||||

Proof of Proposition 4-(2).

The comparison of FDE:

=

,

,

, otherwise,

;

,

,

, otherwise,

;

, , , otherwise, .

The specific comparison is shown in the table below.

Table A2.

Optimal mode selection of FDE.

Table A2.

Optimal mode selection of FDE.

| Conditions | Size Relation of FDE | Optimal Mode Selection | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | ||||

| P | ||||

| — | ||||

| N | ||||

| H | ||||

| — | ||||

| H | ||||

| N | ||||

Proposition

A1.

(1) , , Therefore when , ; When , ;

, , Therefore when , ; When , ;

, , , Therefore when , ; When , .

The specific comparison is shown in the table below.

Table A3.

Optimal mode selection of greenness.

Table A3.

Optimal mode selection of greenness.

| Conditions | Size Relation of Greenness | Optimal Mode Selection | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | ||||

| P | ||||

| — | ||||

| N | ||||

| H | ||||

| — | ||||

| H | ||||

| N | ||||

(2)

,

Because , so when , , ;

When , , .

In summary,

, , otherwise, .

The comparison of and , and is omitted here due to its similarity to the aforementioned approach.

References

- Zhang, Z.J.; Chen, Z.W.; Wan, M.Y.; Zhang, Z. Dynamic quality management of live streaming e-commerce supply chain considering streamer type. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 182, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Fu, S.C.; Ma, F.F.; Miao, B.X. The complexity analysis of decision-making for horizontal fresh supply chains under a trade-off between fresh-keeping and carbon emission reduction. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2024, 183, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; He, Y.; Pakdel, G.H.; Li, S. Dynamic optimization of e-commerce supply chains for fresh products with blockchain and reference effect. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2025, 214, 124040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Hadj-Hamou, K.; Rekik, Y. Blockchain traceability valuation for perishable agricultural products: Balancing economic benefit and social impact. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2025, 206, 104546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Liu, Z.; Wu, W.; Xu, N.; Jiang, M. “GenAI+ Blockchain” to coordinate agricultural supply chains to improve quality trust: An agent-based simulation study. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1591350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]