Abstract

Digital retail is undergoing a paradigm shift driven by the deep integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and augmented reality (AR). Although prior studies have examined the independent effects of AI-based personalized recommendation (cognitive path) and AR-enabled immersion (experiential path), how their integration systematically shapes user behavior through internal psychological mechanisms remains an important unresolved theoretical gap. To address this gap, this study develops an integrated model grounded in the stimulus–organism–response (S-O-R) framework and trust transfer theory. Specifically, the model examines how personalized recommendation, as a dynamic external stimulus, influences users’ cognitive state (perceived usefulness) and experiential state (immersion); how the overall trust of users in the integrated platform can be used as a key boundary condition to adjust the transformation efficiency from the above stimulus to the internal state; and how the above cognitive and experiential states can ultimately drive the continued usage intention through the mediation of positive emotional response. Based on survey data from 400 Chinese consumers with AR shopping experience on Taobao, analyzed using structural equation modeling (SEM), the results indicate that (1) personalized recommendation positively affects both immersion and perceived usefulness; (2) platform trust significantly and positively moderates the effects of personalized recommendation on both immersion and perceived usefulness; (3) both cognitive and experiential states stimulate positive emotions, which in turn enhance continued usage intention, with perceived usefulness exerting a stronger effect; (4) a key theoretical finding is that there is a significant positive correlation between perceived usefulness and immersion, revealing the coupling of psychological paths in an integrated environment; however, immersion does not moderate the effect of personalized recommendation on emotional responses, suggesting that the current integration mode emphasizes the formation of a stable psychological structure rather than real-time interaction. This study makes three contributions to the existing literature. First, it extends the application of S–O–R theory in a complex technological environment by analyzing the “organism” as a parallel and related cognitive-experience dual path and confirming its coupling relationship. Second, it elucidates the enabling role of trust as a moderating mechanism rather than a direct antecedent, thereby enriching micro-level evidence for trust transfer theory in the context of technology integration. Finally, by contrasting path coupling with process regulation, this study provides a more detailed distinction for understanding the theoretical connotations and boundaries of AI–AR technology integration, which may mainly be a kind of structural integration.

1. Introduction

Digital commerce is undergoing a fundamental paradigm shift, increasingly shaped by the integration of intelligent systems such as artificial intelligence (AI) and augmented reality (AR). In this emerging paradigm, AI is no longer confined to the back-end of algorithm optimization, or front-end sensory presentation. Such systems analyze user behavior and historical data to infer preferences, thereby enhancing the relevance of the presented options and supporting more informed decisions [1]. Meanwhile, AR technology enriches the user experience by superimposing digital information on the physical environment, enabling users to conduct immersive “try on” or “preview” interactions, thereby establishing a connection between online and offline shopping [2], effectively bridging the gap between online and offline shopping. However, despite the accelerated pace of commercial adoption, a core theoretical gap remains. Specifically, existing research lacks a coherent framework to explain how this comprehensive technical stimulus shapes users’ psychology and behavior through the interaction system of cognition and experience.

Existing academic discussions still regard AI and AR as parallel or complementary independent tools to a large extent. In this view, AI is primarily responsible for background algorithmic optimization and recommendation generation, whereas AR focuses on sensory presentation and interactive experience [3]. Although these parallel tracks are valuable, such discussions inadvertently deal with cognitive (AI-driven) and experiential (AR-driven) paths in isolation, failing to fully reflect the reality of the increasing integration of AI and AR in contemporary digital platforms. In advanced e-commerce environments, AI dynamically drives AR content and contextual adaptation, while AR generates context-rich data that feed back into AI algorithms, jointly shaping a more adaptive user experience. Although the application of AI in the field of e-commerce (especially the personalized recommendation system) has been widely studied [4,5,6,7], the immersion experience of AR and its impact and behavioral intention have also accumulated a wealth of studies [2,8,9], but the research in these two aspects is mainly developed on a parallel track. This has created a key theoretical gap. Specifically, when AI and AR are integrated into a unified platform, the important theoretical gap of how key technical features affect user behavior through parallel cognitive and experience paths has not been fully filled.

Accordingly, existing research predominantly examines these technologies in isolation [10,11], failing to capture how personalized recommendations as external stimuli (S) trigger parallel cognitive and affective pathways (O) and drive behavioral responses through the mediating factors of immersion and perceived usefulness (R). This oversight limits a comprehensive understanding of consumer decision-making processes in advanced digital retail environments. Moreover, the underlying mechanisms of transforming these technological stimuli into sustained usage behaviors remain unexplored. Prior research has noted that in the literature related to personalized recommendation systems, there is a lack of research on the impact of immersion and a lack of research on a series of subsequent consumer behaviors [12]. Although the stimulus–organism–response framework has been applied to online contexts, its use in explaining the continuous process from recommendation exposure to emotional response and subsequent usage behavior remains limited. Although it has been confirmed that trust can partially moderate the relationship between key factors and purchase intention [13], trust as a key boundary condition has not received sufficient attention in existing models. Further research is needed on how user trust in the platform moderates the psychological impact of technological stimuli [14,15]. Consequently, understanding of the psychological coupling of AI–AR technology in a comprehensive environment and how this coupling, which may be regulated by key factors such as user trust, can be transformed into sustained behavioral outcomes is limited. Addressing this gap is essential for advancing theories of user engagement in next-generation, technology-infused retail platforms.

To address the aforementioned research gaps, this study develops an integrated research model grounded in the stimulus–organism–response (S-O-R) framework to systematically examine the following core issues: whether, in AI–AR integrated e-commerce environments, personalized recommendations influence consumers’ continuance intention through parallel cognitive (perceived usefulness) and experiential (immersion) pathways (RQ1); and whether platform trust serves as a boundary condition that moderates the effects of personalized recommendations on both cognitive (perceived usefulness) and experiential (immersion) pathways (RQ2).

To empirically test the proposed theoretical model, data were collected via a questionnaire survey of 400 Chinese consumers and analyzed using structural equation modeling (SEM). The selection of Chinese consumers as the research sample is theoretically and contextually appropriate. The Chinese retail market represents an advanced context for digital transformation, in which numerous enterprises are leveraging integrated AR and AI technologies to reshape consumption scenarios and establish differentiated competitive advantages. Moreover, Chinese consumers demonstrate high levels of acceptance and substantial experience with emerging interactive technologies, thereby providing a research setting with strong ecological validity for examining how technology integration influences consumer behavior.

By extending the stimulus–organism–response (S-O-R) framework and trust transfer theory in the integrated AI–AR e-commerce environment, this study advances the existing literature in the following three aspects.

First, this study advances understanding of the internal processes of the “organism” by conceptualizing a dual-path psychological mechanism. Specifically, the organism state is decomposed into parallel cognitive (perceived usefulness) and experiential (immersion) pathways. In addition, the components of the response are refined by differentiating between proximal emotional responses and distal behavioral outcomes (continued usage intention). This structured application delineates a continuous cognition–experience–emotion–behavior process, thereby providing a more precise mechanism explanation for how technological stimuli are internalized and transformed into continuous behavioral outcomes in digital retail.

Second, by introducing trust as a moderating variable, this study extends the boundary conditions of the S-O-R framework. The study demonstrates that users’ trust in the platform play a crucial moderating role, strengthening the influence of the stimulus (personalized recommendation) on the organism state (immersion and perceived usefulness). This integration enriches the S-O-R paradigm, explaining when stimuli are most effective, transcending the universal effect and becoming a contingent effect, driving the framework to evolve from a universal effect model to a contextual model.

Third, this study empirically demonstrates the catalytic role of trust in a multi-technology context, enriching the application scenarios of the trust transfer theory. The study shows that users’ general trust transfer in the e-commerce platform enhances their perceived value and immersion of specific AI and AR functions. Trust is shown to function not merely as an outcome or direct antecedent of behavior, but as a catalytic mechanism that amplifies the psychological efficacy of external technological stimuli, providing micro-level evidence for understanding the function of trust in complex technological environments.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The second section of the article reviews the concepts and development of the S-O-R and trust transfer theory. The third section describes the variables and methods for collecting samples. The fourth section conducts validity analysis and path analysis of the model. The fifth section summarizes the research results, discusses the limitations of the study, and explores the directions for future research.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Theoretical Background

2.1.1. S-O-R Model

The S-O-R framework provides a classic and robust paradigm for explaining how environmental cues trigger observable behaviors through an individual’s internal state [15]. Within this framework, the stimulus (S) refers to external environmental factors, the organism (O) denotes individuals’ internal cognitive and affective states elicited by such stimuli, and the response (R) represents the resulting behavioral reactions or intentions. The S-O-R framework has been widely applied to explain consumers’ cognitive and emotional responses to technology-mediated environments, including AR-enabled retail contexts [16]. Prior research has further emphasized that the framework provides a powerful tool for analyzing the structured relationship between the technological environment and user behavior [17]. Overall, the value of the S-O-R framework lies in its ability to capture the interaction between environmental stimuli and consumer psychological and behavior responses.

Despite its strong explanatory power, direct application of the S-O-R framework to intelligent retail environments characterized by deep AI–AR integration requires further contextual extension. In prior research, stimuli are typically conceptualized as relatively static or pre-designed interface elements [1]. In contrast, the AI-driven personalized recommendation system examined in this study is inherently dynamic—continuously updated based on user data—and interactive, as it can trigger subsequent user actions [18]. As such, it constitutes a real-time, algorithmically generated informational stimulus. The primary expansion of this study lies in redefining “stimulus”, emphasizing its attribute as an “interactive dynamic information entity” in the intelligent integration scenario, in order to more accurately capture the starting point of technological impact.

Within highly immersive AR interaction experience, the “organism” state of the user exhibits complexity. Traditional studies often treat the cognitive and emotional dimensions as relatively independent or simply sequentially connected constructs. However, in deeply integrated technological environments, users’ cognitive evaluations and experiential emotional perceptions are likely to occur simultaneously, interwoven and dynamically influencing each other [19,20]. Accordingly, the organism is structurally analyzed into two parallel paths, a cognitive path (centered on perceived usefulness) and an experiential path (centered on immersion), with the hypothesis that these paths reinforce each other in AI–AR integrated experiences. This processing aims to open the organism black box and reveal the interaction of its internal psychological mechanisms.

Furthermore, the response stage is refined by distinguishing proximal emotional reactions from distal behavioral intentions, such as continuance intention. Emotions are conceptualized as a mediating mechanism that translates organism states into long-term behavioral outcomes. This distinction clarifies the transmission mechanism from psychological processes to behavioral outcomes, emphasizing the mediating role of emotions in the post-adoption stage.

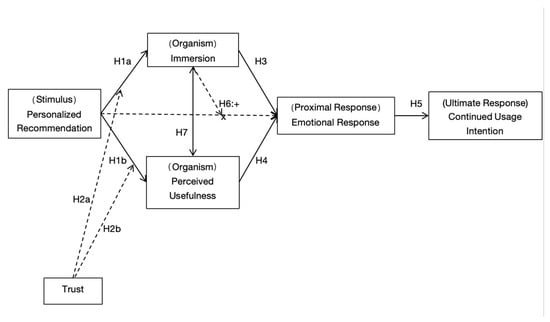

Collectively, these extensions organize variables within the S-O-R framework [21,22], redefine stimuli in the intelligent environment, conduct structural analysis of the organism’s dual paths, and refine the response stage, thereby contextualizing and enhancing the model. They also render the S-O-R framework more suitable for explaining users’ psychology and behavior in the integrated environment of AI and AR, and provide a more detailed theoretical perspective for the future application of the S-O-R framework in the context of intelligent business. As shown in Figure 1, the conceptual framework of this study is presented.

Figure 1.

Research model.

2.1.2. Trust Transfer Theory

The theory of trust transfer posits that the trust established within one entity can be transferred to another related entity associated with it [23]. This process is fundamentally cognitive, whereby individuals generalize their trust in a familiar target to new, associated contexts [24,25]. In the field of e-commerce research, trust transfer theory has been applied to examine trust propagation, typically conceptualized as intra-channel transfer (from a primary brand to a sub-brand within a platform) and inter-channel transfer (from offline to online channels) [26,27].

Trust is a critical factor in ensuring the reliability of a platform, and this theory has been widely applied in the dynamic study of trust in e-commerce [28,29,30]. Empirical studies demonstrate that trust in the source of information can significantly shape brand attitudes and consumer evaluations [25,31]. Visual cues representing the physical location of the entity on the website can also effectively enhance users’ trust intentions and purchase intentions [32]. The trust transfer process offers a theoretical perspective for understanding the establishment of initial trust in digital environments [33].

In commercial platforms that integrate new technologies such as AI and AR, trust transfer exhibits greater complexity. First, the overall trust formed by users towards the entire e-commerce shopping platform, based on repeated interactions and brand reputation, constitutes the foundation of the trust reservoir. This reservoir facilitates the initial transfer from the platform to the technology, and users tend to attribute credibility to the embedded AI recommendation system and AR interface within the platform [34].

Second, within the integrated systems, cross-technology trust transfer can emerge. Positive experiences with one technological component may enhance trust in another [35,36]. For instance, when the AI system consistently delivers accurate and useful recommendations, users may infer that the AR tools used to visualize these recommended products are also reliable and true [37]. Conversely, highly realistic and effective AR experiences provide sensory evidence that reinforces confidence in the AI recommendation system [38]. Such reciprocal trust reinforcement among technological components contributes to the dynamic consolidation of overall platform trust.

In this study, trust is operationalized as users’ overall perception of the integrated AI–AR systems within the platform. This construct represents the aggregated trust state emerging from a multi-level transfer process, encompassing both platform-to-technology trust and the reciprocal reinforcement among technological components. Overall trust is set as a key boundary condition (moderator variable), aiming to examine how it moderates the relationship between stimuli (personalized recommendation) and organisms (immersion and perceived usefulness). This approach does not directly test the transfer path; rather, it investigates how the aggregated platform trust formed through the transfer mechanism serves as a regulatory factor shaping users’ psychological processing of integrated technological features. In mature, highly integrated business platform ecosystems, users typically form an overall judgment of the platform’s trustworthiness through continuous and diverse interactions [14]. Such overall trust is the fundamental psychological prerequisite for adopting embedded AI and AR functionalities as integral components of platform services [39]. Consequently, it aggregates the outcome of the multi-level trust transfer process into a measurable key moderator variable, which is particularly suitable for testing how trust reserves systematically relate to the user’s reception efficiency of technological stimuli in real integrated environments.

This perspective extends the trust transfer theory beyond traditional inter-entity migration, highlighting how aggregated trust, as a moderating factor, affects the effectiveness of the stimulus–organism relationship in the context of technology integration, thereby providing a new theoretical entry point for understanding the dynamic role of trust in intelligent business.

2.1.3. The Conceptualization of the Integrated Experience of AI and AR: A Bidirectional Augmented Perspective

Although prior studies have extensively examined the individual impacts of AI and AR in e-commerce—with AI focusing on cognitive utility in personalization [4,5,6,7] and AR emphasizing immersive experiential value [2,8,9]—important theoretical gaps remain. Much of the existing academic research treats these technologies as parallel or complementary tools operating on independent tracks. Such an isolated perspective overlooks the collaborative dynamics of contemporary digital platforms, where AI dynamically configures AR content, which in turn generates rich contextual data to refine AI algorithms. Consequently, a coherent framework explaining how AI–AR integration systematically shapes user psychology through interacting cognitive and experiential pathways is lacking. To address this gap, this study goes beyond the conventional single-technology perspective and provides a theoretical definition for AI–AR integration. It is conceptualized as a bidirectional enhancement process that can generate intelligent contextually immersive experiences. This process consists of two interrelated mechanisms that establish a mutually reinforcing feedback loop system, which has not been fully elucidated in previous research.

First, intelligent contextual immersion denotes the enhancement of AR experience through the personalized capabilities of AI [40]. Traditional AR provides standardized immersion, such as fixed 3D product models [41]. In integrated AI–AR systems, AI enhances user experiences at interaction points by leveraging individual profiles, including historical preferences and browsing histories, as exemplified by Lacoste’s virtual shoe try-on and TopShop’s virtual dressing room applications [42]. Consequently, immersion transitions from a static experience to an intelligent, contextually adaptive one, closely aligned with users’ personal needs, thereby substantially increasing depth, personal relevance, and decision-making value.

Second, the immersive-driven data loop highlights that AR functions not merely as a presentation layer but also a critical data capture interface. Unlike traditional online interactions, which primarily generate superficial behavioral indicators such as clicks and dwell time [43], immersive AR interactions—such as manipulating virtual products or assembling combinations—generate rich, contextual data reflecting user’s interests, hesitations, and esthetic preferences [44,45]. This high-quality feedback forms a real-time data loop, making subsequent AI recommendations more accurate and context-sensitive [46], thereby creating a continuous adaptation mechanism absent in independent technology deployment.

From this dual enhancement perspective, the integration of AI–AR is therefore defined as a mutually reinforcing dynamic process. Personalized recommendations (AI outputs) and immersive experiences (AR perceptions) thus become interdependent dimensions within a unified system. Accordingly, although this study does not operationally isolate their independent effects, it theoretically captures their psychological coupling. This conceptualization represents a substantive advancement beyond traditional single-technology research, as it provides a framework to examine the comprehensive psychological architecture formed by the fusion of cognitive and experiential stimuli.

2.2. Hypothesis and Model Development

Personalized recommendation systems, as a key source of information, deliver accurate and relevant content that fosters users’ positive evaluation of system intelligence and relevance. Immersion is a temporal psychological state in which users’ sensory attention becomes detached from the physical environment, blurring the boundary between reality and virtual contexts [47]. AR enhances user experiences by enabling immersive and interactive forms of recommendation presentation [48]. Acharya et al. observed that highly personalized recommendation enables consumers to experience temporal dissociation and heightened concentration, thereby fostering immersion [12]. When users receive recommendation content that closely matches their preferences, their depth of engagement with the platform environment is enhanced. Recent studies indicate that recommendation systems enrich immersive user journeys by predicting and presenting content based on users’ prior activities [43,49]. Through heightened attentional focus and reduced awareness of the surrounding environment, users are more likely to develop immersive experiences.

In digital commerce contexts, perceived usefulness specifically refers to the extent to which consumers believe that personalized recommendation systems assist them in completing shopping tasks and enhancing decision-making quality [12,50]. Personalized recommendation systems curate product suggestions based on users’ historical behaviors and preferences. By filtering irrelevant options and presenting aligned information, these systems reduce consumers’ cognitive load during product evaluation. This reduction in cognitive effort facilitates more efficient decision-making, thereby enhancing the perceived usefulness of the system [11]. The convenience and relevance of the information delivered by such systems are among the most critical factors influencing users’ perceived usefulness [20]. Lv and Huang emphasized that personalized recommendation, as an automated and data-driven tool, enables users to fulfill their individualized needs through product and service processes recommended by intelligent systems [1], thereby improving overall decision-making quality. Users primarily perceive technology as useful when its information and functions effectively support purchase-related decisions.

Within the S-O-R framework, personalized recommendation systems function as external stimuli that influence users’ internal cognitive and affective states by delivering tailored and highly relevant product information. These systems reduce information overload and increase task relevance, thereby improving users’ concentration and engagement while elevating perceived usefulness at the cognitive level. Accordingly, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1a.

Personalized recommendation is positively associated with immersion.

H1b.

Personalized recommendation is positively associated with perceived usefulness.

The trust transfer theory posits that an individual’s trust in a certain entity significantly influences the depth of processing and acceptance of the information provided by that entity [51]. In the AI–AR integrated shopping context examined in this study, whether personalized recommendations—the core output of intelligent platform services—can effectively stimulate users’ internal states largely depends on users’ overall evaluations of system trustworthiness.

In this study, trust is operationalized as users’ overall perception of the platform and its integrated AI–AR technological system within the usage context. Conceptually, this overall trust perception is regarded as the result of a trust transfer process [52,53]. It originates from the transfer of users’ baseline platform trust to specific technical functions and may be dynamically consolidated due to the reliability and consistency demonstrated by the AI and AR components in the actual experience [27]. Accordingly, it represents the user’s comprehensive trust judgment of the integrated technical ecosystem.

Based on this, this study proposes that this overall trust constitutes a crucial boundary condition that moderates the strength of the influence of the core external stimulus (personalized recommendation) on the user’s internal state (immersion and perceived usefulness). When the overall trust level is high, the psychological costs and perceived risks associated with interpreting system-generated recommendations are substantially reduced [54]. This psychological state prompts the user to be more willing to invest cognitive resources and deeply immerse themselves in the environment constructed by the recommended content, thereby strengthening the stimulating effect of personalized recommendation on immersion [40]. Simultaneously, high trust functions as a positive heuristic, reinforcing users’ expectations regarding the functional value of recommended information and increasing their tendency to view recommendations as effective decision aids, thereby strengthening the impact of personalized recommendations on perceived usefulness [55]. When engaging with system-generated suggestions, high platform trust reduces users’ psychological vigilance and perceived risks. This reduced defensive posture allows users to engage more openly and deeply with recommended content, thereby increasing the likelihood of immersive experiences and higher usefulness evaluations. Accordingly, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H2a.

Trust positively moderates the relationship between personalized recommendation and immersion, such that the higher the user’s trust level, the stronger the positive association of personalized recommendation with immersion.

H2b.

Trust positively moderates the relationship between personalized recommendation and perceived usefulness, such that the higher the user’s trust level, the stronger the positive association of personalized recommendation with perceived usefulness.

The S-O-R framework, as a core organismic state, is posited to directly elicit users’ proximal emotional responses. Emotions are shaped by environmental stimuli and play a critical role in guiding users’ decision-making processes. Immersion originates from the conscious sensation of “being in” an environment, which is grounded in unconscious spatial perception processes [56,57]. When users are fully immersed in a virtual environment, their attention, emotions, and sensory perceptions become highly focused on the mediated environment [2,8]. This psychological shift enhances sensitivity to emotional cues inherent in brands, products, or experiences, thereby intensifying emotional response such as pleasure, excitement, surprise, or trust. Prior research on virtual reality has demonstrated that immersive viewing experiences significantly influence emotional arousal and perception through vivid sensory cues [58]. When digital immersive experiences can effectively simulate the usage scenarios of the real world, the emotional response within these environments will become reliable predictive indicators for users’ reactions in real life. Importantly, emotions triggered in immersive digital environments are comparable to those invoked in physical settings, further enhancing their predictive validity [59]. Accordingly, emotions elicited in highly immersive media environments exhibit higher predictive validity and more accurately reflect users’ emotional states and behavioral tendencies in actual usage scenarios. Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3.

Immersion is positively associated with emotional response.

From a cognitive appraisal perspective, perceived usefulness is expected to translate into positive emotional responses. This is because emotions are fundamentally generated through an individual’s cognitive evaluation of events, which then trigger corresponding affective reactions that guide subsequent decisions and behaviors [60,61]. Within the digital shopping context, perceived usefulness constitutes a key cognitive appraisal of a system’s functionality, reflecting the degree to which users believe that a recommendation system or virtual environment assists them in achieving their goals [62,63]. Crucially, perceived usefulness has been established as a key antecedent of user satisfaction [64]. Consequently, when users perceive a system as highly useful, this positive cognitive assessment can trigger positive emotional response and reinforce uses’ confidence in the platform [65], thereby guiding their subsequent behaviors.

During product selection, consumers often rely on cognitive heuristics to simplify complex decision-making processes. In this context, perceived usefulness serves as a salient positive signal that not only guides rational judgment but also acts as a mental shortcut shaping emotional response [61,65]. As a positive cognitive cue, perceived usefulness effectively elicits positive emotional reactions. The cognitive transformation of useful information transforms objective system outputs into subjective experiential states, thereby triggering stronger affective responses. Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4.

Perceived usefulness is positively associated with emotional response.

Within the S-O-R framework, the proximal emotional response (ER) functions as a pivotal affective mechanism driving ultimate behavioral outcomes. Positive emotions elicited during the AI–AR-enabled shopping experience, such as pleasure and excitement, enhance platform attractiveness and foster user’s psychological attachment [66,67]. Such affective states reduce decision uncertainty and motivate continued engagement, thereby directly strengthening the intention to continue using the platform [68]. In digital marketing contexts, these positive emotions are not merely incidental but functional, translating directly into sustained behavioral intentions [69]. Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H5.

Emotional response is positively associated with continued usage intention.

Apart from the direct influence, the path through which personalized recommendations affect users’ emotional responses is likely to be contingent on the experiential context. Immersion, conceptualized as a state of deep cognitive engagement and psychological absorption, has been proven to significantly alter an individual’s processing mode of external stimuli [8,70]. In this state, personalized recommendations are unlikely to be perceived as an intrusive external cue. Instead, they become an integrated component of the ongoing experiential narrative in the AR environment. This situational consistency between the recommended content and the immersive experience can enhance the users’ affective processing [71].

Specifically, in high-immersion experiences, the recommended content has a higher situational consistency with the AR environment and exploration behavior of the users. When recommended items are perceived as a coherent and relevant part of the exploration journey, this will prompt users to experience stronger positive emotions, such as pleasure, excitement, or desire [21]. Conversely, when the immersion level is lower, the same recommendations may be processed more rationally or dismissed as isolated information.

Building on the above theoretical reasoning, this study proposes that immersion plays a positive moderating role between personalized recommendation and emotional response; that is, the higher the immersion level, the stronger the enhancing effect of personalized recommendation on positive emotional response. Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H6.

Immersion positively moderates the relationship between personalized recommendation and emotional response. That is, the higher the user’s immersion level, the stronger the positive association of personalized recommendation with emotional response.

In the stimulus–organism–response (S-O-R) framework, organism (O) represents the internal state triggered by external stimuli [16]. In the context of this study, the integration of AI–AR aims to simultaneously activate users’ cognitive and experiential states through personalized recommendation (stimuli). We propose that perceived usefulness (the cognitive path) and immersion (the experiential path) are not independent of each other but are positively correlated [72]. This association constitutes a key manifestation of technology integration at the psychological level of users.

From cognitive appraisal to experiential immersion, perceived usefulness provides a motivational basis for deep engagement [73]. When users are convinced that the system can improve decision-making efficiency and quality, their interaction behavior tends to become more goal-oriented. This goal-oriented focus reduces cognitive distraction and prompts users to fully engage in the AR environment, thereby promoting the formation of immersion [74,75].

On the other hand, from experiential validation to cognitive reinforcement, immersive interactions provide users with embodied evidence. High fidelity and spatial exploration of products in the AR environment generates direct sensory feedback about product attributes [76,77]. Such immersive experiences serve as experiential validation of the system’s perceived usefulness, reinforcing users’ cognitive judgments regarding the system’s practicality and effectiveness.

In a technology system that effectively integrates AI and AR functions, perceived usefulness and immersive experience are expected to show a jointly reinforcing variation. The positive correlation between them reflects the degree to which the technological stimulus is integrated into a coherent psychological representation. Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H7.

There is a positive correlation between perceived usefulness and immersion.

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Sampling and Data Collection

This study adopted a cross-sectional questionnaire-based survey design. The questionnaire was developed and administered via a Chinese online research platform “Wenjuanxing” (Changsha Lanxing Information Technology Co., Ltd., Changsha, China).

The purpose of this study was to investigate users’ AR shopping experience. Therefore, two screening questions were included at the beginning of the questionnaire: “Have you ever used the Taobao app?”; “Have you ever used AR shopping functions such as ‘AR try-on’ in the Taobao app?”. Only participants who answered ‘yes’ to the above two questions could enter the formal questionnaire (Appendix A).

This study employed purposive non-probability sampling. Through the sample service of the Wenjuanxing platform, the research team distributed the questionnaire link to the group marked as “Taobao users” in its active sample library. This push method, based on specific user profiles, aims to reach the target population efficiently. Therefore, the size and boundaries of the target population cannot be precisely defined, and it is impossible to calculate the sampling error and confidence interval with statistical significance. The sample results should not be directly extended to all Chinese Internet users or all users of e-commerce platforms. This study aims to provide in-depth exploratory evidence for understanding the psychological mechanism of this specific and emerging user group in the environment of technology integration.

In addition to the above screening questions, to mitigate potential common method bias, the study implemented several procedural remedies during the questionnaire design and distribution [78]. Firstly, the items measuring different latent variables were randomly arranged to avoid the consecutive occurrence of items of the same construct. Secondly, in the questionnaire introduction, participants were clearly informed of the anonymity of the survey, the purely academic purpose of the data, and the commitment to strict confidentiality to reduce social desirability bias. Finally, reverse-scored items were set in the scale (such as emotional response) to prompt participants to read and answer carefully. In total, 480 questionnaires were distributed. After excluding incomplete responses, regular responses, or short completion times, a total of 400 valid questionnaires were obtained, with an effective recovery rate of 83.33%.

As shown in Table 1, 37.25% of the participants were male, 62.75% were female, and the majority were aged between 26 and 35 (46.5%), followed by participants aged between 18 and 25 (24.75%). The educational background ranged from high school to doctoral degree, with 38.25% having a Master’s degree and 33.25% having a Bachelor’s degree. Variations in age, gender, and experience of the sample may influence the frequency of AR usage. In terms of frequency of use, 32.75% indicated occasional use and 32.5% indicated several times a week, indicating a sample with substantial practical experience.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of sample characteristics.

3.2. Measures

This research model comprises six latent variables. All items were assessed using a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). The measurement of key construct elements was adapted according to the established scales in the literature to ensure content validity. As shown in Table 2, item wording was appropriately contextualized based on the specific context of this study, namely, the e-commerce environment that integrates AI recommendations and AR experiences. The specific sources and sample items are as follows:

Table 2.

Questionnaire content.

Personalized recommendation (PR) was measured using a three-item scale adapted by Nguyen et al. to measure users’ perception of the personal relevance of the recommended content [79].

Immersion (IM) uses a three-item scale adapted by Daassi and Debbabi to measure the cognitive investment and time distortion degree of users in AR interactions [2].

Perceived usefulness (PU) and trust (TR) use scales adapted from Arghashi and Yuksel for measurement [15]. The former is used to assess users’ perception of the practicality of platform functions, and the latter is used to measure the overall trust level of users in the platform’s reliability.

Emotional response (ER) measures positive emotional states by drawing on the three-item scale of Xia et al. [65].

Continued usage intention (CUI) uses a three-item scale based on the work of Bhattacherjee to reflect users’ willingness to continue using the platform in the future [80]. Table 2 presents the questionnaire content used in this study. Descriptive statistics for all measurement items are presented in Appendixe A and Appendixe B.

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Bias

To examine the potential influence of common method bias on the study findings, a statistical approach was employed. First, an unrotated exploratory factor analysis (Harman single-factor test) was conducted on all 18 measurement items in the model. The results showed that the first extracted factor explained 23.395% of the total variance, which was below the commonly accepted threshold of 40% [78], suggesting that common method bias is unlikely to pose a serious threat in this study.

4.2. Validity Analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) indicated an excellent model fit to the data. As shown in Table 3, all fit indices met or exceeded their recommended thresholds (χ2/df = 1.460; GFI = 0.953; CFI = 0.981; TLI = 0.976; RMSEA = 0.034), collectively indicating a strong fit [81].

Table 3.

CFA model fit indices.

Convergent validity was assessed based on standardized factor loadings, average variance extracted (AVE), and composite reliability (CR), following the established criteria proposed by Fornell and Larcker [82]. As summarized in Table 4, all standardized factor loadings were statistically significant (p < 0.001) and exceeded 0.55, all AVE values were above the 0.50 benchmark, and all CR values were greater than 0.70, thereby providing strong evidence of satisfactory convergent validity.

Table 4.

Reliability and convergent validity of measurement model.

Discriminant validity was evaluated using the criterion established by Fornell and Larcker [82]. As shown in Table 5, the results indicate that discriminant validity was satisfactorily established. For example, the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) for personalized recommendation (PR) is 0.840, exceeding its highest correlation with any other construct (0.284 with continued usage intention, CUI). Likewise, the square root of the AVE for trust (TR) is 0.820, surpassing its absolute highest correlation (0.100 with emotional response, ER). The low-to-moderate correlations observed among the distinct constructs, together with the strong internal item loadings demonstrated previously, provide robust evidence supporting discriminant validity. This confirms that each construct in the model is statistically distinct and uniquely captures a phenomenon not represented by others.

Table 5.

Discriminant validity.

4.3. Structural Equation Modeling Analysis

Following confirmation of the measurement model, a structural equation model (SEM) was employed to test the hypothesized direct paths within the structural model. The structural model demonstrated a good fit to the observed data (χ2/df = 1.993; CFI = 0.964; TLI = 0.956; RMSEA = 0.050), as shown in Table 6. All fit indices met the recommended thresholds proposed by Hu and Bentler (1999), confirming that the model is suitable for subsequent path analysis [81].

Table 6.

Fit indices for the measurement and structural models.

The results of the direct path analysis within the structural model are summarized in Table 7. All hypothesized direct paths were supported. Personalized recommendation (PR) exerted a significant positive impact on immersion (IM) (β = 0.298; p < 0.001) and perceived usefulness (PU) (β = 0.323; p < 0.001), supporting hypotheses H1a and H1b. Furthermore, both immersion (IM) (β = 0.131; p = 0.028) and perceived usefulness (PU) (β = 0.273; p < 0.001) significantly predicted proximal emotional response, supporting hypotheses H3 and H4. Proximal emotional response (ER) had a significant positive impact on the intention to continue using (CUI) (β = 0.307; p < 0.001), supporting hypothesis H5.

Table 7.

Structural path coefficient testing.

The positive correlation between perceived usefulness (PU) and immersion (IM) was further examined via the standardized correlation coefficient in the confirmatory factor analysis model. As reported in Table 5, the correlation between PU and IM was significant (φ = 0.153; p < 0.01). supporting hypothesis H7. Thus, all direct path hypotheses in the proposed research model were supported.

To clarify the relative contributions of the cognitive and experiential paths in driving emotional response, this study compared the standardized path coefficients of H3 and H4. The results indicated that the effect of perceived usefulness (PU) on emotional response (ER) (β = 0.273) was stronger than that of immersion (IM) (β = 0.131), with the difference being statistically significant. This finding suggests that in the integrated AI–AR shopping context studied in this research, users’ emotional responses are more strongly influenced by cognitive evaluations of technological practicality utility than purely by immersive experiences. This insight provides empirical evidence regarding the relative weighting of cognitive and experiential mechanisms in a fused AI–AR environment, which simultaneously embodies both functional and experiential attributes.

4.4. Moderation Analysis

Given the limitations of Amos in testing moderation effects, the SPSS PROCESS macro (Version 4.0) was employed to examine interaction effects. This approach is specifically designed to test interaction effects and allows direct estimation and significance testing of the moderating effect [83].

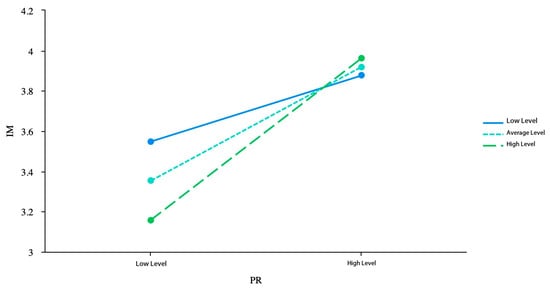

First, the moderating effect of trust (TR) between personalization and immersion was tested, corresponding to H2a. As shown in Table 8, the coefficient of the interaction term (personal recommendation × trust) was significantly positive (β = 0.119; p = 0.006), and the increment in model R2 was significant (ΔR2 = 0.018; p = 0.006). Although the ΔR2 value of this interaction term was relatively small, indicating that it explained modest additional variance of additional variance, its statistical significance still supports the theoretical role of trust as a key boundary condition. This finding indicates that trust amplifies the positive impact of personalized recommendation on immersion [84].

Table 8.

Moderation effect (PR × Trust → IM).

Notably, after including the interaction term, the main effect of TR became non-significant. This suggests that trust primarily functions as a moderator, influencing the strength of the PR–IM relationship rather than exerting a direct effect on IM [83]. Simple slope analysis further revealed (Figure 2) that trust was high and the relationship between personal recommendation and immersion was stronger, providing additional support for H2a.

Figure 2.

Moderating effect (PR × Trust → IM).

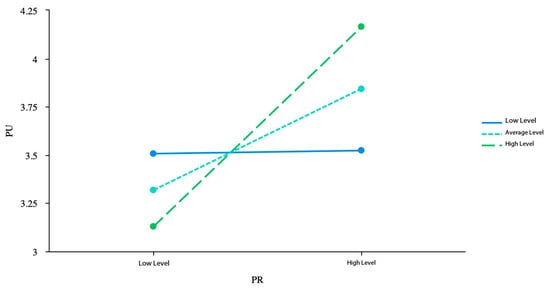

Second, the moderating effect of trust (TR) on the relationship between personalized recommendation (PR) and perceived usefulness (PU) was tested, corresponding to H2b. As presented in Table 9, the interaction term (personalized recommendation × trust) was also significantly positive (β = 0.255; p < 0.01), and ΔR2 = 0.090; p < 0.001. Although the additional variance explained by the interaction is moderate, its statistical significance confirms that trust functions as a critical moderator, enhancing the effect of PR on PU [84]. The simple slope analysis (Figure 3) further revealed that at high levels of TR, the positive relationship between PR and PU was stronger, providing additional support for H2b.

Table 9.

Moderation effect (PR × TR → PU).

Figure 3.

Moderating effect (PR × TR → PU).

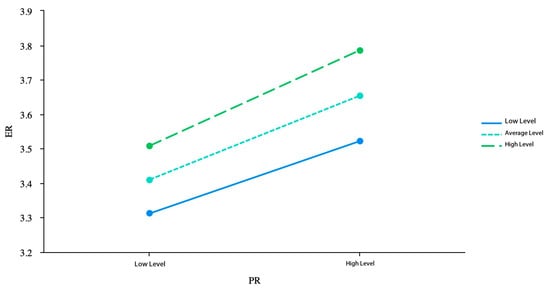

Notably, contrary to the expected results of H6, the moderating effect of immersion (IM) on the relationship between PR and emotional response (ER) was not statistically significant. As presented in Table 10, the interaction term (PR × IM) was non-significant (β = 0.117; p = 0.729), and ΔR2 indicated no meaningful change. Simple slope analysis (Figure 4) indicated that the slopes of PR → ER were comparable under both high and low IM conditions. Consequently, H6 was not supported, suggesting that IM, as an experiential state, may not serve as a key boundary condition for enhancing the emotional impact of PR in this context. Theoretical implications are discussed in the subsequent section.

Table 10.

Moderation effect (PR × IM → ER).

Figure 4.

Moderating effect (PR × IM → ER).

5. Discussion

Building on the S-O-R framework and trust transfer theory, this study developed and empirically tested an integrated model to elucidate the psychological mechanisms through which the integration of AI and AR technology has an impact on users’ continued usage intention (CUI). The study found that personalized recommendation (PR), as the core external stimulus, can significantly enhance users’ immersion (IM) experience and perceived usefulness (PU), then stimulate positive emotional response (ER) and ultimately increase user’s continued usage intention (CUI).

This study’s theoretical contribution primarily lies in the in-depth examination of the internal structure of the impact pathways and their boundary conditions. The analysis reveals an asymmetry in the effects of the cognitive (PU) and experiential (IM) paths on emotional response, with PU exerting a substantially stronger influence than IM. Although the two affect emotion independently, there is a significant positive correlation between PU and IM, which shows that in the technology integration environment, users’ cognitive judgment and experience perception are not separated from each other, but together constitute an interrelated psychological system. Moreover, TR functions primarily as a regulatory factor, enhancing the efficiency with which external stimuli (PR) are transformed into internal psychological states (PU and IM), rather than directly determining these states.

Notably, immersion (IM) did not significantly moderate the impact of personalized recommendation (PR) on emotional response (ER). In functionally oriented, mature e-commerce contexts, AI–AR integration appears to emphasize the establishment of a stable psychological structure that combines cognitive evaluations and experiential perceptions, systematically enhancing overall experiential value, rather than dynamically amplifying the immediate emotional impact of recommendations.

This study is grounded in real-world application scenarios with a high degree of technology integration in domestic e-commerce platforms, and focuses on the overall perception of users on the integrated technology. By examining the fundamental pathways through which technology integration influences behavior, analyzing the relative strength of cognitive and experiential paths, and clarifying the moderating role of trust (TR), the study provides a nuanced theoretical perspective on how AI–AR integration shapes user psychology in digital smart retail environments. Overall, the study can be seen as an expansion and refinement of existing theories in the new context of technology integration. Its conclusion is more reflected in the phased dynamic of users’ psychological mechanisms. Nevertheless, these findings still need to be further verified in different technology configurations, cultural contexts, and product types, so as to jointly promote the continuous improvement of the theoretical system in this field. The theoretical contributions and practical implications of this study are elaborated in the subsequent sections.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This study offers several novel and theoretically significant contributions to the literature on information systems, consumer behavior, and immersive digital commerce. First, the study advances S-O-R theory by reconceptualizing the organism as a psychologically coupled system rather than a set of discrete internal states [16]. Prior applications of the S-O-R framework in digital and technology-mediated contexts have typically operationalized the organism as independent cognitive or affective components (e.g., perceived usefulness or enjoyment examined in parallel) [18,85]. This conventional approach implicitly assumes that cognitive evaluations and experiential states are processed independently. Addressing this theoretical limitation, the present study develops and empirically validates a coupled cognitive–experiential organism structure, in which perceived usefulness (PU) and immersion (IM) are psychologically interdependent rather than isolated.

The findings reveal that the significant positive association between PU and IM indicates that, in AI–AR integrated environments, instrumental evaluations and immersive experiences jointly constitute a unified psychological system. By providing empirical evidence for this coupling mechanism, this study fills a critical gap in prior research that examined AI-driven utility and AR-driven experience along parallel tracks without capturing their psychological interaction [3,86]. Hence, this study advances S-O-R theory by moving beyond a static and fragmented view of the organism toward a more structured and mutually reinforcing conceptualization, providing a refined theoretical lens for understanding internal user processes in complex, multi-technology retail environments.

Second, this study contributes to the information systems and marketing literature by reconceptualizing the theoretical role of trust (TR) from a direct behavioral antecedent to a situational enabler within integrated digital platforms. To date, existing studies have predominantly treated trust as a direct determinant of behavioral intention or internal states in technology adoption models [15]. Contrary to this dominant perspective, our findings indicate that overall platform trust (TR) does not directly influence immersion (IM) or perceived usefulness (PU). Instead, trust functions as a significant positive moderator that strengthens the effects of personalized AI-driven recommendations on both cognitive and experiential organism states.

This finding addresses an underexplored research gap regarding how trust operates within mature, interactive socio-technical systems. Specifically, this study extends trust transfer theory by demonstrating that, in integrated platform ecosystems, trust (TR) primarily acts as a contextual catalyst that lowers users’ psychological resistance and amplifies the effectiveness of technological stimuli [28,34]. By shifting the role of trust from a primary driver to a key boundary condition, this study enriches the micro-level theoretical understanding of trust in digital environments and provides a more nuanced explanation of how trust shapes user responses to advanced technologies [35].

Third, this study contributes to consumer behavior and technology adoption research by identifying a clear boundary condition for the relative importance of cognitive versus experiential pathways in AR-enhanced e-commerce. While prior research in immersive commerce has predominantly emphasized hedonic or immersive experiences as the primary drivers of user engagement and emotional responses, our findings reveal a systematic asymmetry between organismic states [44]. Specifically, perceived usefulness (PU) exerts a significantly stronger impact on users’ emotional responses (ER) than immersion (IM).

This finding addresses an underexplored theoretical question by demonstrating that, in goal-directed e-commerce contexts, users’ emotional responses (ER) are predominantly driven by cognitive evaluations of instrumental value, even in the presence of immersive AR features [59,65]. By providing empirical evidence that challenges the experience-dominant perspective, this study clarifies that the relative salience of experiential versus cognitive pathways depends on the utilitarian nature of the task environment. Consequently, it extends consumer behavior and technology adoption theories by identifying a boundary condition under which cognitive appraisal predominates in shaping emotional responses within immersive digital commerce settings.

Fourth, this study contributes to AI–AR research by clarifying the nature of AI–AR integration through a conceptual distinction between structural coupling and processual coupling. Although the term “technology integration” is widely discussed in the literature, it is often applied in a generalized and conceptually ambiguous manner, without specifying how different technologies interact at the psychological level [19].

Consistent with our hypotheses, the findings indicate that AI–AR integration in the examined context is primarily realized through structural coupling, whereby multiple technologies jointly construct a stable and unified psychological foundation for users. This stands in conceptual contrast to processual coupling, in which one technology dynamically moderates or modifies the real-time effect of another [21]. This distinction indicates that, in the present context, AI and AR operate synergistically by forming a coherent psychological structure rather than by interactively adjusting each other’s immediate functional effects.

By explicitly defining and empirically distinguishing these two forms of integration, this study addresses an key conceptual gap in prior research and provides a clearer theoretical framework for analyzing multi-technology systems [40,72]. Accordingly, the study provides significant theoretical implications for future research by enabling scholars to investigate with greater precision how different forms of AI–AR integration influence user psychology and behavior. In doing so, it advances theoretical development in information systems and digital marketing toward more context-sensitive and nuanced explanations.

Taken together, the academic contributions of this study can be summarized in three main aspects. First, the study refines the core theoretical framework to more effectively explain user psychology in integrated technological environments, thereby advancing middle-range theory in technology integration and consumer behavior. Second, by empirically examining the psychological integration of AI and AR, this study moves beyond isolated effect analyses and bridges two previously fragmented research streams on AI and AR. Finally, the study clarifies the conceptual mechanisms underlying technology integration and establishes a theoretical foundation for context-sensitive research in digital marketing, immersive commerce, and information systems.

5.2. Practical Implications

This study offers three specific and actionable insights for strategically integrating AI and AR technologies and designing user experience on e-commerce platforms.

First, given the significant interrelation between cognition and experience states, optimizing the accuracy of AI recommendations or the immersion level of AR alone may produce substantial gains with minimal effort. Management should define core performance indicators that assess the effectiveness of technological integration [87], such as the conversion rate of products recommended by AI after the AR experience, or the degree to which the depth of AR interaction affects users’ willingness to accept recommendations in the future. This approach guides technical teams to develop a seamless data-experience loop, ensuring that the AR environment can intelligently retrieve and visualize personalized recommendations, thereby realizing the full integration value.

Second, given that trust can significantly amplify the effect of technological stimulation, in the AR interface, it is possible to incorporate friendly prompts (such as “This virtual try-on is generated based on your preferred style”) to clarify algorithm logic and enhance transparency [11]. In the AR try-on interface, the “recommendation reasons” can be displayed in the form of floating labels, such as “Recommended based on your frequently browsed casual style”; in scenarios such as virtual try-on, disclaimer prompts can be proactively provided (such as “The simulation effect is for reference only”) and multi-angle views can be shown. By actively managing expectations, a professional and reliable image can be cultivated, thereby reducing users’ psychological risk perception [35].

Finally, considering that cognitive pathways dominate emotional responses and immersion’s immediate moderating effect is insignificant, AR design for utilitarian products (e.g., household appliances; tools) should emphasize efficacy demonstration and risk mitigation (e.g., clearly displaying internal structures and size comparisons) to maximize perceived usefulness. For hedonic products (e.g., clothing; cosmetics), bolder investment should be made in immersive narratives and emotional scene construction (e.g., themed virtual fitting rooms) [2,76,88]. For instance, for cosmetic products, AR can provide two virtual try-on scenarios, “daily makeup effect” and “evening makeup effect”, to enhance the sense of situational immersion. Although deep immersion may not directly enhance the effectiveness of a single recommendation, it can effectively increase user loyalty, brand favorability, and exploration pleasure, thereby serving the long-term goal of brand building.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study examines the user psychological mechanism in the environment where AI and AR have achieved commercial integration from the perspectives of personalized recommendation and immersion experience. Therefore, the research design prioritizes ecological validity over experimentally testing the synergistic effects of AI and AR integration. This approach ensures that findings closely reflect real-world business scenarios; however, it also limits the generalizability and causal inference of the results, which warrant further validation across diverse contexts.

First, although this study identifies correlations among variables using cross-sectional survey data, causal inference remains limited. Future research should employ longitudinal designs or controlled experiments to clarify causal directions and effect magnitudes among variables. We chose a survey method with high ecological validity to capture the overall perception and psychological process of users in an authentic and integrated business environment. Nonetheless, this reality-oriented research approach also brings corresponding limitations. For instance, it is impossible to separate the independent effects and interactive effects of different technical conditions, such as “AI only”, “AR only”, and “AI+AR integration”, through experimental manipulation, and it is also difficult to quantify the technical synergy (e.g., the “1 + 1 > 2” effect). Subsequent studies could employ a 2 × 2 factorial experimental design (AI personalization: high vs. low; AR immersion: high vs. low) to rigorously test causal relationships and disentangle both the independent contributions and integration effects of AI and AR.

Second, the dataset is drawn from a user population with a single cultural background (Chinese). Consequently, the generalizability of findings requires validation across diverse cultural contexts, e-commerce platforms, and product types (e.g., high- vs. low-intervention products). Future studies could replicate the present model across varied cultural contexts to assess cross-cultural robustness and examine potential moderating effects of cultural values (e.g., individualism vs. collectivism).

Third, trust was operationalized as a holistic assessment of the integrated system, without deconstructing its potential multidimensional sources (e.g., institutional trust in the platform, algorithmic competence, or interface benevolence). Future research may incorporate multidimensional trust scales to elucidate micro-level pathways of trust transfer. Similarly, immersion could be measured across sensory, cognitive, and affective dimensions to capture its role as a moderating variable more precisely.

Finally, this study offers a detailed perspective for understanding the integration mechanism. The findings indicate that the correlation between cognition and experience (H7) is significant, whereas the immediate moderating effect of experience on emotional response (H6) is non-significant. This suggests that the AI–AR integration mechanism may be contingent upon contextual factors. Future studies could manipulate the recommendation types (utilitarian vs. hedonistic) and immersion levels (high-/low-fidelity AR experience) to examine whether the moderating effect posited in H6 persists across product categories and experiential contexts, thereby further elucidating the contextual dynamics of AI–AR integration.

Additionally, investigating other mediating or moderating mechanisms (e.g., flow experience; technology-related anxiety) and comparing the long-term effects of integrated versus single-technology modes on user engagement represent promising avenues for future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H.; methodology, J.H.; formal analysis, J.H.; investigation, J.H.; resources, J.H.; data curation, J.H.; writing—original draft preparation, J.H.; writing—review and editing, E.T.L.; supervision, E.T.L.; project administration, E.T.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Sejong University (protocol code SU-2025-048 and date of approval 18 September 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used in this study is publicly available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/5TLJ3K, accessed on 6 January 2026.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Questionnaire Survey

Questionnaire survey

Only respondents who answered “Yes” to both questions proceeded to the formal survey.

1. Have you ever used the Taobao app?

□ yes

□ no

2. Have you ever used augmented reality (AR) shopping functions such as ‘AR try on’ in the Taobao app?

□ yes

□ no

Thank you for participating in this survey. The questionnaire is designed to understand your feelings and behavioral tendencies in the process of experiencing augmented reality (AR) and artificial intelligence (AI) recommendation technology. This survey is conducted anonymously. All data are only used for academic research. We will keep your answers strictly confidential. Please answer according to your real experience.

1. Gender: □ male □ female

2. Age: □ 18–25 □ 26–35 □ 36–45 □ above 46

3. Education: □ high school and below □ Bachelor’s □ Master’s □ doctorate

4. Contact frequency of personalized recommendation service: □ almost every day (≥1 time/day) □ several times a week (≥4 times/months) □ occasionally (1–3 times/months) □ very rarely (≤1 times/months)

Note: In order to control the common method deviation, the items measuring different potential variables are randomly arranged in the questionnaire to avoid the continuous occurrence of items with the same structure. In addition, a reverse scoring item was set in the scale to prompt participants to answer cautiously.

Instructions: please choose the option that best suits your opinion according to your real experience of using the AR shopping function on the Taobao platform.

(1 = strongly disagree; 2 = disagree; 3 = average; 4 = agree; 5 = strongly agree)

| Item | Statement | Corresponding Latent Variable |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | The AR experience on the platform made me feel happy. | Emotional Response (ER) |

| 2 | I obtained a highly realistic sensory experience in the system. | Immersion (IM) |

| 3 | I trust that the platform will not disclose my personal information. | Trust (TR) |

| 4 | The recommendations I receive are tailored to my preference. | Personalized Recommendation (PR) |

| 5 | Using this platform for shopping makes it easier for me to find the goods I need. | Perceived Usefulness (PU) |

| 6 | I will keep using this platform as regularly as I do now. | Continued Usage Intention (CUI) |

| 7 | The recommendations are personalized. | Personalized recommendation (PR) |

| 8 | The interaction and content of the platform aroused my positive emotions. (R) | Emotional Response (ER) |

| 9 | The recommendations and functions of the platform have been of great help to me overall. | Perceived Usefulness (PU) |

| 10 | I will frequently use this platform for shopping. | Continued Usage Intention (CUI) |

| 11 | When shopping through the platform, it made me so immersed that I forgot about the real environment around me. | Immersion (IM) |

| 12 | I believe the information provided by the platform is accurate and reliable. | Trust (TR) |

| 13 | The interactive experience of the platform made me feel completely immersed. | Immersion (IM) |

| 14 | The recommendations match my needs. | Personalized recommendation (PR) |

| 15 | The AR function has improved my shopping efficiency. | Perceived Usefulness (PU) |

| 16 | During the usage process, I felt familiar and excited. | Emotional Response (ER) |

| 17 | I intend to continue using this platform in the future. | Continued Usage Intention (CUI) |

| 18 | I believe the personalized recommendations of the platform are made with consideration for my interests. | Trust (TR) |

Note: (R) indicates that the question is a reverse-scoring question.

This appendix presents the complete questionnaire distributed to the respondents. In the actual data collection, this study uses purposeful non-probability sampling and uses the “questionnaire star” platform to push the questionnaire link to the group marked as “Taobao users” in its active sample library. It is difficult to define the exact scale and boundary of the overall target (active users with AR shopping experience on the Taobao platform). Therefore, this study cannot calculate the sampling error and confidence interval defined in the random sampling survey, and its sample results should not be directly extended to all Chinese Internet users. The core value of this study is to provide in-depth exploratory evidence for understanding the psychological mechanism of this specific and emerging user group in the environment of technology integration.

Appendix B. Descriptive Statistics of Measurement Items

| Latent Variable | Item | Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (SD) | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personalized Recommendation (PR) | PR1 | 3.75 | 1.022 | −0.524 | −0.317 |

| PR2 | 3.73 | 0.978 | −0.417 | −0.460 | |

| PR3 | 3.65 | 1.030 | −0.428 | −0.479 | |

| Trust (TR) | TR1 | 3.33 | 1.231 | −0.250 | −0.833 |

| TR2 | 3.32 | 1.177 | −0.235 | −0.718 | |

| TR3 | 3.49 | 1.242 | −0.487 | −0.683 | |

| Immersion (IM) | IM1 | 3.63 | 1.098 | −0.477 | −0.506 |

| IM2 | 3.56 | 1.086 | −0.361 | −0.646 | |

| IM3 | 3.75 | 1.051 | −0.547 | −0.283 | |

| Perceived Usefulness (PU) | PU1 | 3.68 | 1.010 | −0.521 | −0.116 |

| PU2 | 3.70 | 0.974 | −0.347 | −0.453 | |

| PU3 | 3.43 | 1.040 | −0.303 | −0.439 | |

| Emotional Response (ER) | ER1 | 3.60 | 1.055 | −0.355 | −0.566 |

| ER2 | 3.59 | 1.014 | −0.354 | −0.417 | |

| ER3 | 3.42 | 1.098 | −0.239 | −0.612 | |

| Continued Usage Intention (CUI) | CUI1 | 3.48 | 1.122 | −0.251 | −0.805 |

| CUI2 | 3.71 | 1.017 | −0.358 | −0.618 | |

| CUI3 | 3.46 | 1.061 | −0.192 | −0.678 |

References

- Lv, L.; Huang, M. Can personalized recommendations in charity advertising boost donation? The role of perceived autonomy. J. Advert. 2024, 53, 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daassi, M.; Debbabi, S. Intention to reuse AR-based apps: The combined role of the sense of immersion, product presence and perceived realism. Inf. Manag. 2021, 58, 103453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeri, M.; Sadeghi-Niaraki, A.; Grubert, J.; Choi, S.M. Personalized AR Content and POI Recommendation in Mobile Cultural Heritage Systems Using Semantic Relatedness. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2025, 24, 11628–11640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potwora, M.; Zakryzhevska, I.; Mostova, A.; Kyrkovskyi, V.; Saienko, V. Marketing strategies in e-commerce: Personalised content, recommendations, and increased customer trust. Financ. Credit Act. Probl. Theory Pract. 2023, 5, 562–573. [Google Scholar]

- Vullam, N.; Vellela, S.S.; Reddy, V.; Rao, M.V.; SK, K.B. Multi-agent personalized recommendation system in e-commerce based on user. In Proceedings of the 2023 2nd International Conference on Applied Artificial Intelligence and Computing (ICAAIC), Salem, India, 4–6 May 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 1194–1199. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, N.; Abdelraouf, M.; El-Shihy, D. The Moderating Role of Personalized Recommendations in the Trust–Satisfaction–Loyalty Relationship: An Empirical Study of AI-Driven E-Commerce. Future Bus. J. 2025, 11, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, A.; Yang, J. Optimisation of E-Commerce Personalised Recommendation Algorithms Driven by Neural Network Models. J. Combin. Math. Combin. Comput. 2025, 127, 3003–3020. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, D. How Does Immersion Work in Augmented Reality Games? A User-Centric View of Immersion and Engagement. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2019, 22, 1212–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Frank, B. Optimizing Live Streaming Features to Enhance Customer Immersion and Engagement: A Comparative Study of Live Streaming Genres in China. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 81, 103974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Sun, W.; Liu, J.; Nah, K.; Yan, W.; Tan, S. The Influence of AR on Purchase Intentions of Cultural Heritage Products: The TAM and Flow-Based Study. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Qiu, X.; Wang, Y. The Impact of AI-Personalized Recommendations on Clicking Intentions: Evidence from Chinese E-Commerce. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, N.; Sassenberg, A.M.; Soar, J. The Role of Cognitive Absorption in Recommender System Reuse. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senali, M.G.; Iranmanesh, M.; Ghobakhloo, M.; Foroughi, B.; Asadi, S.; Rejeb, A. Determinants of Trust and Purchase Intention in Social Commerce: Perceived Price Fairness and Trust Disposition as Moderators. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2024, 64, 101370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arghashi, V.; Yuksel, C.A. Interactivity, Inspiration, and Perceived Usefulness! How Retailers’ AR-Apps Improve Consumer Engagement through Flow. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 64, 102756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, N.; Ryding, D.; Vignali, G.; Pantano, E. AR Atmospherics and Virtual Social Presence Impacts on Customer Experience and Customer Engagement Behaviours. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2025, 53, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Xu, Y.; Porterfield, A. Antecedents and Moderators of Consumer Adoption toward AR-Enhanced Virtual Try-On Technology: A Stimulus–Organism–Response Approach. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 1319–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adawiyah, S.R.; Purwandari, B.; Eitiveni, I.; Purwaningsih, E.H. The influence of AI and AR technology in personalized recommendations on customer usage intention: A case study of cosmetic products on shopee. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Yoon, S. Testing the Effects of Personalized Recommendation Service, Filter Bubble and Big Data Attitude on Continued Use of TikTok. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2025, 37, 1280–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Xiong, S.; Zhang, C. Effects of Virtual Makeups ‘Perceived Augmentation on Consumers’ Perceived Value. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2025, 37, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H.Y.; Perks, H. Effects of Consumer Perceptions of Brand Experience on the Web: Brand Familiarity, Satisfaction and Brand Trust. J. Consum. Behav. 2005, 4, 438–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaris, C.; Vrechopoulos, A.; Sarantopoulos, P.; Doukidis, G. Additive Omnichannel Atmospheric Cues: The Mediating Effects of Cognitive and Affective Responses on Purchase Intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 64, 102731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, M.D.U.; Tseng, T.H.; Cheng, H.L.; Chiu, C.M. An Empirical Analysis of eWOM Valence Effects: Integrating Stimulus–Organism–Response, Trust Transfer Theory, and Theory of Planned Behavior Perspectives. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 81, 104026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buntain, C.; Golbeck, J. Trust Transfer between Contexts. J. Trust Manag. 2015, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Hong, I.B. Consumer’s Electronic Word-of-Mouth Adoption: The Trust Transfer Perspective. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2019, 23, 595–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Lu, Y.; Wang, B.; Wei, K.K. The Role of Inter-Channel Trust Transfer in Establishing Mobile Commerce Trust. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2011, 10, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]