Abstract

The rapid expansion of digital trade presents transformative opportunities for South-South cooperation, particularly between China and West Africa. However, emerging new risks in technological, institutional, and sociocultural domains pose significant challenges to sustainable e-business collaboration. This study proposes a Pythagorean Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process (PF-AHP) framework to evaluate and prioritize these risks under conditions of uncertainty and expert judgment ambiguity. By integrating fuzzy logic with AHP, the model effectively captures the vagueness and imprecision inherent in multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM). Expert assessments from professionals in digital trade, cybersecurity, and risk management were used to conduct pairwise comparisons across three primary risk categories: Technological, Institutional, and Sociocultural Risks. The results indicate that Institutional Risk (weight: 0.3488) holds the highest priority, followed by Sociocultural Risk (weight: 0.3268) and Technological Risk (weight: 0.3244), highlighting the critical influence of cultural alignment, consumer trust, and behavioral norms in cross-border digital collaboration. The PF-AHP approach enhances decision reliability by incorporating membership, non-membership, and indeterminacy degrees, offering a robust tool for risk assessment in complex digital supply chains. This research contributes to the discourse on equitable digital globalization and provides strategic insights for policymakers and stakeholders aiming to build inclusive, resilient, and mutually beneficial digital trade ecosystems between China and West Africa.

1. Introduction

Global trade is seeing a substantial transition propelled by digital technologies. The conventional emphasis on the transportation of tangible items across borders is increasingly augmented by the digital transmission of data, services, and products through e-business platforms. The transformation is fundamentally driven by the rise of e-commerce ecosystems that amalgamate diverse services, including transportation, banking, and cloud computing. These ecosystems are transforming international trade dynamics, with China in the forefront as a global e-business leader, while West Africa is starting to adopt digital solutions to expedite economic development.

China’s involvement in the digital revolution is founded on its extensive internet infrastructure [], comprising over 1 billion internet users, exceptional technical capabilities, and a strong, thriving e-commerce environment. China has become a major player in global e-business, using projects like the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to spread its power across Africa. China’s expanding economic might is changing the way commerce works throughout the world. This gives West Africa, a region that has always been on the edge of global digital trade, a chance to work together more. The argument over global digital sovereignty has also gotten stronger in the last few years. More and more African countries, notably those in West Africa, want to be in charge of their own data and digital infrastructure so they don’t have to rely on foreign digital powers.

Another important reason for the sudden need is the region’s growing population. Mobile technology use is growing quickly in Africa, especially in West Africa, where there are a lot of young, tech-savvy people. This makes mobile-first solutions more and more possible for growing e-commerce. Mobile internet is spreading quickly, which is helping this change happen. In West Africa, mobile phones are becoming the main way for people to access e-commerce sites. Countries such as Ghana, Nigeria, and Côte d’Ivoire are at the forefront of digitalizing their economies, developing innovative financial services, and nurturing a new cohort of technology entrepreneurs. However, substantial obstacles persist, such as insufficient digital infrastructure, legislative fragmentation, and cybersecurity issues, which can impede the complete actualization of digital trade potential. This change in demographics, together with the rise of mobile internet, makes this relationship even more important right now, giving a sense of urgency to our study.

West Africa, comprising 16 member states of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), spans approximately 6 million km2, about one-fifth of the African continent, and is home to over 420 million people (World Bank, 2024). The region is characterized by rapid urbanization and a youthful, tech-savvy population, which has fueled the adoption of mobile first digital services. However, digital trade in West Africa operates across 10 distinct national currencies, reflecting fragmented monetary systems that complicate cross-border e-commerce and financial interoperability (AfDB, 2023). Internet penetration, while growing, remains uneven averaging around 50% in urban centers but significantly lower in rural areas posing both opportunities and infrastructural challenges for digital collaboration.

However, barriers impede the path to digital prosperity in West Africa. Issues such as inadequate digital infrastructure, uneven regulations, restricted data management capabilities, and security vulnerabilities persist. Many small enterprises continue to face challenges in accessing global digital value chains due to insufficient exposure, financial resources, or digital competencies. Chinese enterprises seeking to penetrate African digital marketplaces must navigate unfamiliar territories, cultural disparities, and heightened scrutiny on data security and digital sovereignty concurrently.

In this evolving context, it is imperative to inquire. How can China and West Africa collaborate in commerce supply chains to ensure mutual benefit and sustainability? What strategies must be implemented to ensure that this collaboration fosters inclusive growth, honors local contexts, and unlocks sustainable innovation?

This study is driven by the need to understand how China and West Africa can develop a mutually beneficial and sustainable digital trade partnership in the era of rapid digital transformation. While extensive research has explored Sino-African cooperation in traditional domains such as infrastructure, energy, and resource extraction, there remains a critical gap in understanding the role of digital trade and e-business as key enablers of South-South cooperation. Digital connectivity, e-commerce platforms, and smart supply chains present transformative opportunities for inclusive economic growth, yet they also introduce complex, multidimensional risks that are not adequately addressed by conventional evaluation frameworks.

To bridge this gap, this research investigates the key risks, technological, institutional, and sociocultural, that hinder effective e-business collaboration between China and West Africa, while identifying strategic pathways toward resilient and context-sensitive digital integration. A major limitation of existing risk assessment models lies in their inability to handle uncertainty, subjective expert judgments, and imprecision in decision-making processes, often leading to unstable or unreliable outcomes.

To address these challenges, this study proposes the use of Pythagorean Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process (PF-AHP) framework, which integrates fuzzy set theory with the classical AHP to better capture ambiguity, hesitation, and inconsistency in expert evaluations. By incorporating degrees of membership, non-membership, and indeterminacy, the PF-AHP model allows for more robust pairwise comparisons under conditions of uncertainty. This approach enhances the reliability and robustness of risk prioritization, offering a more comprehensive and adaptive methodology for assessing emerging risks in cross-border digital supply chains between China and West Africa.

This paper aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of China–West Africa digital trade collaboration through a multilevel analysis incorporating regional insights, expert judgment, and a structured Pythagorean Fuzzy AHP framework. By evaluating key risks in technological, institutional, and sociocultural domains, the study contributes to the growing discourse on digital globalization and highlights the potential of South–South partnerships to foster equity, inclusivity, and mutual development in the digital economy. It illustrates the evolving digital relationship between China and West Africa, demonstrating how strategic, digitally enabled cooperation can move beyond traditional donor-recipient dynamics toward innovation-driven, sustainable, and context-sensitive partnerships suited for the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century.

2. Literature Review

E-business risks China’s cooperation with West Africa has significantly evolved over the past two decades, driven by shared interests in economic development, infrastructure investment, and political alignment. However, despite its potential, the Chinese e-businesses operating in West Africa as a result of this cooperation faces challenges and risks threatening its success.

Institutional risks concentrate on the uncertainties and challenges that arise due to the nature, quality, and stability of the system in which a business operates. These risks which include absence of coherent e-business policies, the lack of digital transaction regulations, limited data governance, and weak e-government support [,,,] for digital trade significantly escalate transaction costs in e-business by creating an environment of uncertainty and unpredictability. Transaction Cost Theory (TCT) posits that firms seek to minimize transaction costs, particularly those related to information asymmetry, monitoring, and enforcement [,]. According to Cauffman & Goanta [], in the absence of clear policies and regulations, firms face higher compliance costs, as they must invest more in legal expertise, adjust their operations to various and often changing standards, and manage the risks of opportunistic behavior. This inefficiency necessitates greater vigilance and coordination costs, ultimately inflating the overall transaction costs and hindering smooth cross-border operations in the digital economy [,]. Technological risks are the potential problems and threats that arise from the use, implementation, and management of technology in business operations []. These risks can disrupt e-businesses ability to function effectively, often leading to increased costs, inefficiencies, or failures. These encompasses complexity of modern e-business technologies, lack of IT expertise, cybersecurity threats and digital infrastructure deficiencies [,]. Recent studies underscore how sociocultural misalignment, such as divergent norms around data privacy or digital trust, can amplify transaction costs in Sino-African digital ventures [,].

According to TCT, in the e-business environment where uncertainty and unpredictability exist, these problems substantially increase transaction costs in e-business []. For instance, when firms face inadequate IT infrastructure or cybersecurity vulnerabilities, they incur higher costs for monitoring, protection, and technology integration, as well as potential data breaches or system failures []. Moreover, the complexity of modern technologies adds to the difficulty of efficient coordination and decision-making, raising the cost of transaction management and further complicating cross-border operations []. According to Nanda & Zhang [], sociocultural risks are the challenges e-businesses face when interacting with diverse cultural, social, and behavioral norms across different regions. Risks such as language barriers, consumer behavior differences, cultural misalignment in virtual workforces, resistance to online payments, social media-induced cultural conflicts, and perceived digital neo-colonialism significantly heighten transaction costs, uncertainty and opportunism in cross-border e-business, as outlined in TCT [,,,]. Sociocultural differences create communication barriers, misaligned expectations, and customer resistance, which lead to higher negotiation and coordination costs [,]. Firms must invest more in adapting their marketing strategies, modifying user experiences, and overcoming cultural misunderstandings, all of which increase monitoring, contract enforcement, and relationship management costs, ultimately raising the total transaction costs [,].

In the legal context, risk refers to the likelihood or possibility of facing adverse consequences, liabilities, or legal challenges due to actions, decisions, or situations that may violate laws, regulations, or contractual obligations []. Legal risks can vary depending on the industry, geography, and nature of the business. In this China-West Africa e-business context, risks such as legal and regulatory frameworks, limited cybercrime legislation, intellectual property (IP) challenges, and legal culture differences, escalate transaction costs in e-business []. This is in line with TCT assumption since firms operating in cross-border economic exchanges are likely to face uncertainties and risks []. Weak legal frameworks increase compliance and monitoring costs as firms navigate unclear or inconsistent regulations []. The lack of cybercrime laws and IP protections raises the risk of fraud, theft, and disputes, necessitating higher investments in legal safeguards []. Cultural differences in legal practices add complexity to contract enforcement and litigation processes, further increasing transaction costs and hindering smooth operations [,].

In all, while the potential for China-West Africa cooperation in e-business is significant, it is negatively affected by institutional, technological, cultural and legal risks. These risks increase transaction costs by introducing complexities and uncertainties. Institutional risks, such as differing regulations, require more investment in compliance and legal strategies. Cultural differences heighten communication barriers and opportunism. Legal risks complicate contract enforcement across borders. Technological risks, like infrastructure issues and cybersecurity threats, add further complexity. Together, these risks necessitate greater vigilance, monitoring, and higher upfront investments, significantly raising the overall transaction costs for firms operating internationally.

2.1. Identification of E-Business Cooperation Opportunities

2.1.1. Digital Platforms and Market Access

Cross-border e-commerce sites like Alibaba and Jumia enable business to access global consumer markets. These Cross-border e-commerce platforms have grown quickly, giving people in many parts of the world access to a wide range of markets []. These platforms are like digital doors for small and medium-sized businesses (SMEs) in West Africa. They allow these businesses to reach customers outside of their local marketplaces, both in Africa and around the world. Digital platforms like Jumia are becoming more common, which means that local firms may reach bigger audiences without having to spend a lot of money on infrastructure. Alibaba and other platforms like it provide China with a well-established e-commerce ecosystem that African enterprises may join. This makes it easier for West African firms to get started because they can use existing logistics networks, payment systems, and customer bases [].

2.1.2. Logistics and Payment Systems

Investments in intelligent logistics and the integration of mobile and financial technology payment systems are essential. Effective logistics and secure payment solutions are essential for the proper functioning of e-business supply chains. In the framework of China-West Africa collaboration, investments in intelligent logistics and financial technology payment systems are crucial for advancing e-commerce and trade between regions.

Logistics: The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) of China has begun significant investments in infrastructure, encompassing ports, trains, and airports, which are essential for enhancing cross-border trade in Africa. These expenditures have been augmented to support e-commerce, necessitating rapid and efficient delivery options. Intelligent logistics systems employing artificial intelligence, big data, and Internet of Things (IoT) technologies are revolutionizing the movement and tracking of goods across international borders. Effective logistics is crucial for overcoming obstacles such as prolonged delivery delays, insufficient standardization, and elevated transportation costs that impede trade in numerous African nations. For instance, China’s e-commerce behemoths, such as Alibaba, have invested in logistics networks to optimize the transit of goods from suppliers to customers. Such assets are now progressively accessible in West African marketplaces.

Payment Systems: The swift embrace of mobile money solutions in West Africa significantly propels e-commerce. Services such as M-Pesa in Kenya and MTN Mobile Money in Ghana have facilitated digital transactions for millions of individuals. This mobile-centric ecosystem enables businesses and customers to execute e-commerce transactions safely. Moreover, China’s fintech innovations, such WeChat Pay and Alipay, have established global benchmarks for mobile payment systems. These solutions are being incorporated into e-business platforms, facilitating cross-border mobile payments and enabling both African and Chinese enterprises to execute transactions rapidly and securely. An essential aspect of integrating these systems is assuring compliance with local regulatory frameworks and fostering customer trust in the security of these platforms, which may necessitate the development of more robust cybersecurity infrastructures.

2.1.3. Capacity Building and Skills Transfer

Training initiatives in e-commerce and public-private collaborations can cultivate local proficiency. The efficacy of e-business collaboration between China and West Africa is contingent not only upon the accessibility of technology and infrastructure but also on the potential to cultivate local talent and entrepreneurial acumen. In this environment, capacity building and skills transfer are essential for enabling both Chinese and West African enterprises to fully capitalize on digital trade prospects.

Training Programs in E-Commerce: Collaborative initiatives between China and West Africa, exemplified by the eWTP (Electronic World Trade Platform), emphasize the enhancement of local capabilities in digital commerce [,]. These programs provide training to local enterprises in e-commerce competencies, digital marketing, and logistics administration. Alibaba’s eWTP has educated small business proprietors in Africa on establishing and managing online storefronts while integrating them with global trade networks. Numerous digital literacy programs focus on entrepreneurs and small business proprietors, instructing them in the utilization of e-commerce platforms and comprehension of the digital environment. These programs are essential for improving local competitiveness and enabling enterprises in West Africa to effectively participate in global markets.

Public-Private Partnerships (PPP): Establishing public-private partnerships (PPPs) to facilitate the transfer of technology, experience, and investment is an essential strategy. Public-private partnerships have effectively facilitated the advancement of digital infrastructure, including internet accessibility, payment systems, and training centers. These collaborations can give access to advanced technologies and expertise from Chinese companies while harmonizing with local requirements and developmental objectives. West African SMEs acquire exposure to Chinese business concepts and technologies through capacity-building projects, enabling them to adapt these to local contexts. This enhances the entrepreneurial ecosystem, fosters innovation, and ultimately fortifies the region’s digital economy.

By facilitating skills transfer via specialized training, collaborative initiatives, and company incubation, both China and West Africa can accelerate the establishment of competitive and sustainable enterprise ecosystems. This will foster a more robust and inclusive digital economy adept at addressing the problems presented by climate change, infrastructure deficiencies, and regulatory inconsistencies.

2.2. Risk Analysis in China–West Africa E-Business Supply Chains

This section analyzes the intrinsic risks and challenges that affect the efficient functioning of e-business supply networks between China and West Africa. These obstacles arise from infrastructural constraints, regulatory complications, cybersecurity threats, and geopolitical volatility. To effectively incorporate e-business concepts in this region, these risks must be deliberately mitigated.

Infrastructure Disparities: Unreliable internet access and an unpredictable power supply present substantial obstacles to the establishment of a seamless and effective e-business environment in West Africa. Although China possesses a strong technology infrastructure that underpins its e-commerce ecosystem, most West African countries continue to have significant deficiencies in internet access and electrical reliability.

Uneven Internet Connectivity: Many West African nations face challenges with inadequate internet availability, especially in rural regions []. This mismatch impedes local enterprises’ access to global e-commerce platforms, thereby limiting their capacity to engage international clients. Countries such as Ghana have made progress, however continue to encounter difficulties in linking isolated populations.

Power Supply Issues: Regular power outages impede the operational efficiency of enterprises, particularly in logistics, data processing, and e-commerce operations that necessitate continuous uptime. The technological sophistication of China and its global infrastructure network, shown by initiatives like the Digital Silk Road, may act as a catalyst for bridging these disparities []. Significant investments are necessary to improve both digital and physical infrastructure in West Africa.

2.2.1. Regulatory and Legal Challenges

Variations in data protection, trade rules, and regulations generate considerable complications in reconciling China’s e-business practices with those of West Africa. The absence of unified rules and disparate laws within the region poses challenges to enterprises seeking to operate globally.

Data Protection and Privacy: In West Africa, data protection legislation is inadequate or inconsistent, resulting in ambiguity about data management, sharing, and safeguarding. This may discourage customers from engaging in online transactions, especially cross-border ones, due to apprehensions regarding privacy and security.

Inconsistent Trade Policies: China’s e-commerce trade strategy is well articulated, but West African nations exhibit diverse legal frameworks concerning e-commerce, taxation, and commercial operations. The absence of a cohesive regulatory framework hinders cross-border e-commerce, impeding enterprises’ ability to expand geographically.

Policy Alignment: The failure of regional policy coherence among nations like as Ghana, Nigeria, and Côte d’Ivoire poses further obstacles for Chinese enterprises aiming to develop. Regulatory disparities in e-commerce, tariffs, and cross-border data transfers must be resolved through policy harmonization to enable more seamless collaboration and trade.

2.2.2. Cybersecurity and Trust Issues

Deficiency in digital literacy and cybersecurity frameworks, coupled with insufficient consumer trust, enhances vulnerabilities. The growing dependence on digital platforms for e-commerce and payment systems necessitates the assurance of secure transactions and the safeguarding of consumer data.

Cybersecurity Vulnerabilities: Businesses and consumers in West Africa frequently encounter increased risks of cyberattacks owing to inadequate cybersecurity infrastructure. Malicious activities, including hacking, fraud, and data breaches, jeopardize the expansion of e-commerce platforms and diminish customer trust in online transactions.

Lack of Consumer Trust: Digital literacy is very low in most West African regions, and consumers frequently exhibit skepticism towards online enterprises. In the absence of sufficient consumer protection legislation and safe systems, the adoption of e-commerce may remain constrained. This dilemma necessitates focused initiatives to foster confidence via enhanced online security protocols and awareness campaigns regarding the safety of digital platforms.

2.2.3. Geopolitical and Economic Risks

Political instability and trade disparities promote the development of e-business supply chains between China and West Africa. Although China’s worldwide trade activities are extensive, West African governments frequently have difficulties in sustaining political stability and managing trade relations.

Political Instability: Certain nations in West Africa encounter difficulties, including frequent leadership transitions, civil disturbances, and internal wars, resulting in an uncertain business climate for international investment. Political instability erodes investor confidence and can impede the advancement of critical infrastructure and regulatory frameworks for digital commerce.

Trade Imbalances: The trade connection between West Africa and China is frequently marked by an imbalance, in which the region exports raw materials while importing manufactured goods. This trade imbalance may obstruct the opportunity for mutually advantageous growth in e-business. Moreover, economic obstacles like variable currency rates and inflation affect the cost-effectiveness and efficiency of international transactions.

While geopolitical instability and macroeconomic volatility, for instance, trade imbalances, fluctuating exchange rates, are not modeled as standalone criteria in this study, they are conceptually embedded within Institutional Risk. For example, currency instability and asymmetric trade structures directly influence regulatory unpredictability, contract enforceability, and policy coherence, core dimensions of institutional environments in West Africa.

2.3. Strategic Approaches for Sustainable Cooperation

For China and West Africa to build resilient, inclusive, and secure e-business supply chains, it is crucial to implement strategic frameworks that are adaptable to local contexts and can align long-term goals with technological advancements. Below are some key strategic approaches that can ensure sustainable cooperation in the digital trade ecosystem.

Policy Harmonization and Bilateral Frameworks: A primary barrier in promoting effective China-West Africa e-business collaboration is the absence of policy uniformity. The different regulations, legislation, and trade policies between China and specific West African countries, as well as intra-regional discrepancies, can obstruct fluid cross-border trade []. Divergences in data protection legislation, tax regulations, and intellectual property rights among various regions hinder the integration of digital trade platforms, impeding the scalability of e-business solutions []. To resolve this challenge, regional and bilateral policy frameworks must be harmonized to establish a cohesive digital environment that facilitates enhanced collaboration. These frameworks would create uniform rules for e-commerce, safeguard customer data, and encourage equitable digital activities throughout both areas.

By establishing a unified legal and regulatory framework, China and West Africa can reduce legal impediments and promote foreign investment in the digital economy []. At the regional level, ECOWAS (Economic Community of West African States) can assume a pivotal role by harmonizing digital policies among West African nations, assuring the alignment of shared aims and standards. At the bilateral level, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) provides a strategic avenue for collaborative policy formulation. Bilateral agreements should emphasize not only commerce but also digital collaboration, encompassing accords on data transfers, cybersecurity, and investments in digital infrastructure. These frameworks would not only augment legal certainty but also bolster trust between Chinese enterprises and their West African counterparts.

Infrastructure Investment and Technology Transfer: The digital barrier between China and many West African countries constitutes a major impediment to efficient e-business collaboration. Joint ICT infrastructure developments are crucial for the flourishing of digital trade. Investment in both physical and digital infrastructure is essential to establish a basis for effective e-business ecosystems in West Africa. Specifically, investment is essential in broadband connectivity, data centers, and cloud computing infrastructure. China have extensive expertise in constructing large-scale infrastructure projects, while West Africa has the opportunity to capitalize on these capabilities through collaborative ventures and investment partnerships.

Chinese enterprises, in partnership with local authorities, can facilitate the construction and modernization of infrastructure that will bolster e-commerce platforms, payment systems, and logistical networks throughout the region []. This would allow local enterprises to access global markets and improve digital capacities in West Africa. Technology transfer is essential for local innovation. China, as a frontrunner in various emerging technologies including artificial intelligence (AI), big data, and the Internet of Things (IoT), can assist West Africa through training and information dissemination in these domains. Through collaboration in technical development, Chinese companies may enhance local capacity in digital technology and entrepreneurship, thereby enabling small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and local innovators to engage actively in the digital economy. Technology transfer must be integrated with skills development to enable the workforce in West Africa to utilize the latest technologies for commercial advancement.

Cybersecurity Cooperation and Digital Ethics: With the expansion of the digital economy, the demand for comprehensive cybersecurity measures also increases. West Africa encounters considerable obstacles in safeguarding its digital infrastructure, as numerous nations grapple with data protection, cyber-attack prevention, and the assurance of secure digital transactions. These vulnerabilities might erode confidence in e-commerce platforms, obstructing their acceptance and expansion. China, possessing established cybersecurity frameworks, is pivotal in offering experience and technologies to enhance West Africa’s cyber resilience. Collaboration in cybersecurity between China and West Africa may include mutual intelligence sharing, capacity enhancement, and collaborative security activities aimed at safeguarding digital platforms and consumers. This includes the formulation of national cybersecurity policies, security assessments, and response strategies to identify and mitigate cyber threats. A crucial domain is digital ethics. As e-business platforms grow, it is imperative to ensure ethical AI utilization, data protection, and equal access to digital resources.

China and West Africa need to cooperate in formulating ethical standards for AI applications, guaranteeing that technologies are utilized transparently and equitably. Advocating for ethical methods in data collecting and digital transactions will foster trust among customers, businesses, and governments, which is essential for the success of any digital ecosystem. These projects will promote sustainable, inclusive digital growth by assuring equitable benefits of digital technologies for all stakeholders.

Inclusive and SME-Focused Strategies: The inclusion of digital trade ecosystems is essential for ensuring that the advantages of e-business collaboration reach not just huge corporations and multinational organizations but also small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), local entrepreneurs, and marginalized communities. In West Africa, SMEs usually serve as the economic backbone yet are often marginalized from digital trade due to constraints such as restricted access to technology, insufficient digital skills, and elevated operational costs. To guarantee the inclusivity of digital trade advantages, China and West Africa must prioritize initiatives that facilitate the integration of SMEs into the digital economy. This may encompass training initiatives aimed at enhancing digital literacy among local entrepreneurs, enabling them to proficiently access and utilize e-commerce platforms, digital payment systems, and online marketing tools [].

Moreover, access to cost-effective digital tools, including cloud services and digital payment solutions, must be enabled for SMEs to ensure their competitiveness against larger firms. Through the use of inclusive digital platforms and business models, China and West Africa may establish a more equal digital environment. This entails providing resources and support to marginalized women and youth entrepreneurs to enable their success in the digital economy. Moreover, public-private partnerships (PPPs) can significantly contribute to small business development by offering funding and capacity-building assistance customized to the distinct requirements of SMEs.

3. Methodology

In this section, we propose the use of the Pythagorean Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process (PF-AHP) methodology for evaluating and prioritizing risks associated with the digital trade collaboration between China and West Africa. The Pythagorean Fuzzy AHP combines fuzzy logic with the AHP framework to handle the uncertainty and imprecision inherent in expert judgment during decision-making processes. Following a similar framework for risk mitigation from Zhao et al. [] to optimize the risk evaluation considering the interrelationships among criteria utilizing the underlying conditions of criteria in the works of Gadafi et al. [] and Tamimu and Liang [].

The expert panel involved in this study consisted of professionals with diverse backgrounds in digital trade, e-commerce, and risk management. Their expertise ensured that the risk evaluation was comprehensive and well-rounded. Table 1 presents the demographic information of the experts who contributed to pairwise comparisons and analysis.

Table 1.

Demographics of Characteristics of Experts Involved.

Although the expert panel comprises six professionals, this sample size is methodologically appropriate for Pythagorean Fuzzy AHP applications in emerging contexts where domain-specific expertise is scarce but critical. Previous studies using fuzzy MCDM methods in complex, cross-regional settings, for example, some recent studies such as Zhao et al. [], Tamimu et al. [] and Gadafi and Musa [] similarly rely on small panels of high-expertise to capture nuanced judgments under uncertainty. The PF-AHP framework compensates for limited sample size by explicitly modeling hesitation and ambiguity through membership, non-membership, and indeterminacy degrees, enhancing decision robustness without requiring statistical generalizability. The Pythagorean Fuzzy AHP method inherently accommodates and quantifies subjectivity through its three-dimensional representation, membership, non-membership, and indeterminacy degrees, allowing for explicit modeling of hesitation and ambiguity in expert judgments. This structure reduces reliance on consensus and instead captures the full spectrum of expert uncertainty, thereby improving the robustness of outcomes even with a small panel.

The methodology for risk evaluation and prioritization using Pythagorean Fuzzy AHP consists of the following steps in detail below.

3.1. Step 1: Risk Identification

The first step involves identifying the risks involved in the digital trade collaboration between China and West Africa. These risks can be categorized into several groups, such as:

- Technological Risks: Infrastructural issues, cybersecurity vulnerabilities, technology integration challenges.

- Institutional Risks: Legal frameworks, regulatory inconsistencies, policy alignment challenges.

- Sociocultural Risks: Cultural differences, language barriers, resistance to digital adoption.

These identified risks will form the criteria for our pairwise comparisons.

3.2. Step 2: Constructing the Pairwise Comparison Matrix

In AHP, we perform pairwise comparisons between the criteria to assess their relative importance. In this case, we will represent the expert judgments using Pythagorean fuzzy numbers.

A Pythagorean fuzzy number is defined as a triplet , where:

- is the membership degree, which represents the degree of preference for one criterion over another.

- is the non-membership degree, representing the degree of dis-preference.

- is the indeterminacy degree, which quantifies the uncertainty in the expert’s judgment.

For pairwise comparison between criteria and , we define the Pythagorean fuzzy number .

For example, a comparison between criterion and criterion might yield:

This indicates that is preferred over with a membership degree of 0.8, a non-membership degree of 0.1, and an indeterminacy degree of 0.1.

The pairwise comparison matrix is symmetric, i.e., .

3.3. Step 3: Normalizing the Fuzzy Pairwise Comparison Matrix

In this step, we normalize the pairwise comparison matrix to ensure consistency. The Pythagorean fuzzy numbers are normalized such that:

This normalization ensures that the comparison matrix is consistent and that all fuzzy numbers satisfy the Pythagorean identity. To normalize a fuzzy number , we compute the norm and divide each component by it:

3.4. Step 4: Aggregating the Normalized Fuzzy Values

Once the pairwise comparison matrix is normalized, we aggregate the normalized fuzzy numbers for each column. The aggregation of fuzzy numbers for each criterion is computed as:

This aggregation reflects the total importance of each criterion relative to all other criteria.

3.5. Step 5: Defuzzifying the Aggregated Values

The next step is to convert the aggregated fuzzy numbers into crisp values. This is done by performing a defuzzification process. For each aggregated fuzzy number , the defuzzified value is calculated as:

This yields a crisp score for each criterion, which represents its relative importance.

3.6. Step 6: Calculating the Weights of the Criteria

After defuzzifying the aggregated fuzzy values, we calculate the relative weights of the criteria. The weight of each criterion is computed by normalizing the defuzzified values as follows:

This ensures that the sum of all the weights equals 1, providing a normalized scale for comparing the importance of each criterion.

3.7. Step 7: Ranking the Criteria Based on Weights

Finally, the criteria are ranked based on their weights. The criterion with the highest weight is ranked first, followed by the next most important, and so on. The ranking is computed by sorting the criteria in descending order of their weights.

The Pythagorean Fuzzy AHP provides a comprehensive and robust method for evaluating and prioritizing risks in situations involving uncertainty and expert judgment. By incorporating fuzzy logic into the AHP framework, this methodology allows for more accurate and reliable decision-making in complex environments, such as the digital trade collaboration between China and West Africa.

4. Results

This section presents the results of the methodology following all the steps from pairwise comparisons, normalized matrix, fuzzy aggregation, defuzzification, and ranking of criteria.

4.1. Pairwise Comparison Matrix (Fuzzy Numbers)

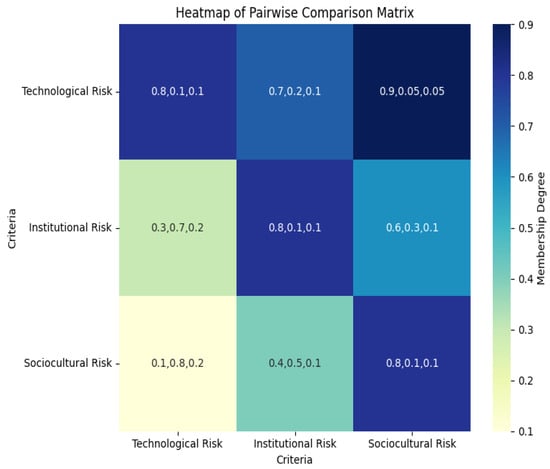

The pairwise comparison matrix in Table 2 captures the relationships between the three criteria (Technological, Institutional, and Sociocultural Risk). The fuzzy values in each cell represent the degree of preference between two criteria on a scale of 0 to 1. The first number in each triplet represents the degree of membership (), the second is the non-membership degree (), and the third is the degree of indeterminacy ().

Table 2.

Fuzzy Values for Pairwise Comparison Matrix.

For example, the comparison between Technological Risk and Institutional Risk shows a value of (0.80, 0.10, 0.10), indicating that Technological Risk is significantly more important than Institutional Risk, with a membership degree of 0.80, a low non-membership of 0.10, and minimal indeterminacy (0.10).

4.2. Normalized Pairwise Comparison Matrix

The normalized pairwise comparison matrix presented in Table 3 is derived by normalizing the fuzzy values from the previous matrix to ensure consistency and make them suitable for aggregation. The values reflect the relative importance of each criterion. For instance, Technological Risk is more important than Sociocultural Risk, as shown by the normalized value of (1.00, 0.06, 0.06). This normalization ensures that the values are compatible for further aggregation and decision-making processes in the fuzzy AHP.

Table 3.

The values for Normalized Pairwise Comparison Matrix.

4.3. Aggregated Fuzzy Values (Column-Wise Summation)

The aggregated fuzzy values in Table 4 are obtained by summing the membership (), non-membership (), and indeterminacy () values across all criteria. These aggregated values provide a single point of reference for each criterion’s fuzzy characteristics. For instance, Sociocultural Risk has the highest aggregated membership degree (2.87), indicating it is considered the most significant criterion in terms of membership degree. Technological Risk has the highest non-membership degree, suggesting it is seen as less clearly defined or more uncertain compared to the others.

Table 4.

Criteria Aggregated Fuzzy Values (Column-wise Summation).

4.4. Defuzzified Values (Crisp Scores)

The defuzzified values of Table 5 represent the crisp scores for each criterion, calculated by reducing the fuzzy values into single values for easier comparison. These scores reflect the overall importance of each criterion based on the fuzzy evaluation. Institutional Risk, with a defuzzified value of 1.86, is deemed the most critical in this evaluation, followed closely by Sociocultural Risk (1.74). Technological Risk has the lowest defuzzified value (1.73), indicating it is the least significant of the three.

Table 5.

Criterion Defuzzified Values (Crisp Scores).

4.5. Weights of the Criteria

Table 6 presents the weights of the criteria derived from the defuzzified values and represents their relative importance in the decision-making process. In this case, Institutional Risk holds the highest weight (0.35), followed by Sociocultural Risk (0.33) and Technological Risk (0.32). These weights provide a quantifiable measure of the relative significance of each risk factor in the digital trade collaboration.

Table 6.

Aggregated Weights of the Criteria.

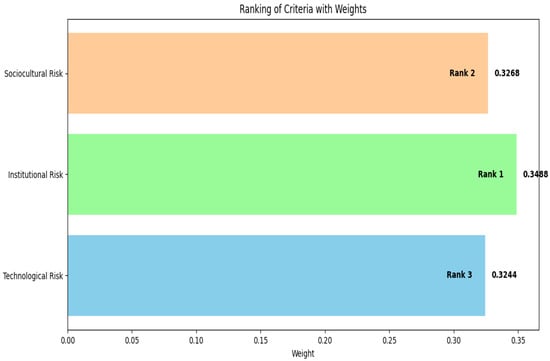

4.6. Ranking of Criteria

The ranking of criteria is illustrated in Table 7 based on the weights obtained in Table 5. Institutional Risk is ranked first, followed closely by Sociocultural Risk in second place, and Technological Risk in third place. This ranking reflects the relative importance of each risk factor based on the fuzzy AHP approach. Despite Institutional Risk having the highest defuzzified value, its rank is affected by the combination of all fuzzy values, with Institutional Risk emerging as the most significant when considering both membership and non-membership degrees.

Table 7.

Final Ranking of Criteria.

4.7. Results Visualization and Analysis

Figure 1 illustrates the fuzzy pairwise comparison between three different risk criteria: Technological, Institutional, and Sociocultural. The fuzzy values are represented using a color gradient from dark blue (indicating lower values) to light yellow (indicating higher values). These values express the degree of importance or relevance between each pair of criteria. In this context, the heatmap plot aids in identifying how each risk factor interacts in terms of prioritization and mutual influence, which is essential for setting weights in the AHP approach. This provides a visual aid for decision-makers to evaluate the most critical risk criteria in the context of digital trade.

Figure 1.

Heatmap of Pairwise Comparison Matrix.

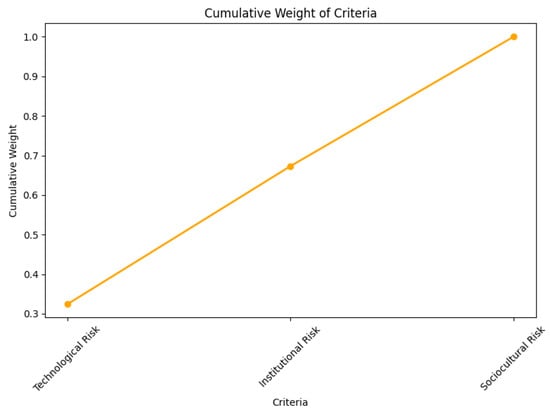

Figure 2 shows the cumulative weight of the criteria, presenting how the weights of the risk factors (Technological, Institutional, and Sociocultural) accumulate. The increasing trend in the graph demonstrates the relative significance of each factor within the fuzzy AHP approach. The Technological Risk has the lowest weight, while Institutional Risk holds the highest cumulative weight. This means that, in this particular evaluation, Institutional Risk is considered the most crucial for decision-making, with Sociocultural and Technological Risks ranked second and third, respectively.

Figure 2.

Cumulative Weight of Criteria.

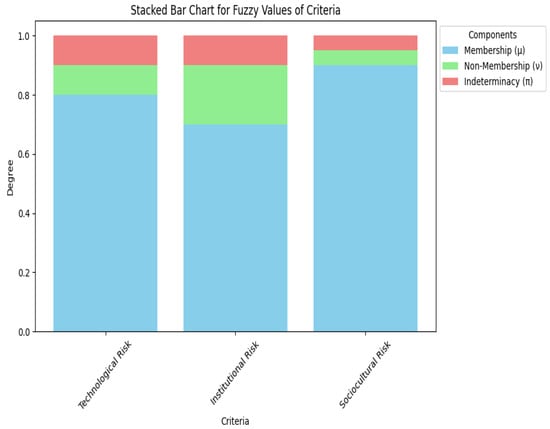

Figure 3 offers a breakdown of the fuzzy values for each risk criterion, highlighting the membership (), non-membership (), and indeterminacy () values for each of the three criteria. This visualization is crucial for understanding the uncertainty and vagueness involved in the fuzzy AHP method. A higher degree of membership suggests that a risk criterion is more clearly defined, while non-membership and indeterminacy levels show where ambiguities might lie. This chart facilitates a deeper understanding of how the criteria are perceived and how their fuzzy values are distributed.

Figure 3.

Stacked Bar Chart for Fuzzy Values of Criteria.

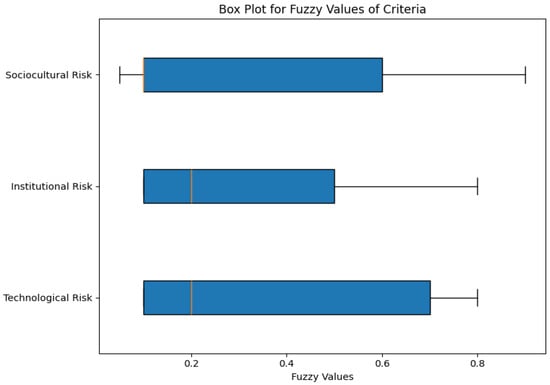

Figure 4 provides an overview of the distribution of fuzzy values for each risk criterion. It shows the median, interquartile range (IQR), and potential outliers for the membership degree across each criterion. Institutional Risk exhibits a wider spread in its fuzzy values, indicating more variability or uncertainty compared to the other criteria. Technological Risk appears more concentrated, with less variance in its fuzzy values, suggesting a clearer consensus on its evaluation. This plot is instrumental in gauging the level of consensus or divergence in the evaluation of risks.

Figure 4.

Box Plot for Fuzzy Values of Criteria.

Figure 5 ranks the risk criteria based on their final evaluated importance. It shows that Institutional Risk holds the highest rank, followed by Sociocultural Risk, with Technological Risk last. This ranking reflects the cumulative weightings and is crucial for understanding the decision-making process. The fuzzy AHP approach, through its assessment of membership, non-membership, and indeterminacy, provides a robust framework for ranking and prioritizing criteria in complex decision environments.

Figure 5.

Ranking of Criteria.

4.8. Study Implication

The findings of this study carry significant theoretical, practical, and policy implications for digital trade collaboration between China and West Africa. Theoretically, the application of the Pythagorean Fuzzy AHP method advances existing risk evaluation models by addressing uncertainty and inconsistency in expert judgments, thereby improving the accuracy and stability of multi-criteria decision-making in international e-business contexts. Practically, the prioritization of sociocultural risks, including language barriers, resistance to digital adoption, and cultural misalignment, underscores the need for Chinese enterprises to adopt localized strategies, enhance digital literacy, and foster consumer trust through culturally sensitive user experiences and transparent data practices.

While technological and sociocultural challenges remain relevant, the prominence of institutional factors suggests that soft infrastructure and human-centered design are equally critical to successful digital integration. From a policy perspective, the results advocate for strengthened bilateral and regional frameworks, including harmonized digital regulations, joint capacity-building initiatives, and public-private partnerships focused on SME inclusion. Moreover, fostering ethical AI use, data sovereignty, and cybersecurity cooperation can help mitigate risks while promoting equitable digital development. For development agencies and investors, this study emphasizes the importance of investing not only in physical ICT infrastructure but also in social capital, education, and cross-cultural communication to ensure sustainable and inclusive digital trade growth.

While the findings highlight institutional risk as the top priority across West Africa, stakeholders must interpret this ranking with caution. The region encompasses 16 ECOWAS countries with significant heterogeneity in digital maturity, consumer behavior, linguistic diversity, and regulatory frameworks. For example, Nigeria’s digital payment ecosystem differs markedly from that of landlocked Niger or francophone Côte d’Ivoire. Therefore, national-level adaptations of this risk framework are essential before implementation.

4.9. Study Limitation

While this study offers a robust and innovative framework for evaluating risks in China-West Africa digital trade collaboration using the Pythagorean Fuzzy AHP (PF-AHP) method, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the risk assessment relies heavily on expert judgment, which, despite being sourced from professionals with diverse regional and sectoral expertise, may introduce subjectivity and potential bias. The small sample size of the expert panel (n = 6) limits the generalizability of the findings, as the results are context-specific and may not fully represent the broader perspectives of stakeholders across all West African countries or Chinese enterprises engaged in digital trade. While the small expert panel limits statistical generalizability, it ensures depth and contextual relevance, particularly vital in under-researched regions like West Africa where qualified experts with Sino-African digital trade experience are rare.

In addition, the study focuses on three primary risk categories, Technological, Institutional, and Sociocultural Risks, while other relevant dimensions such as environmental sustainability, geopolitical volatility, and economic instability were not explicitly modeled as separate criteria. Although some of these aspects are implicitly covered under institutional or sociocultural factors, their exclusion as independent variables may affect the comprehensiveness of the risk evaluation.

Although geopolitical, economic, and environmental risks were not treated as independent criteria due to the study’s focus on core operational risk domains, their influence is implicitly captured within the Institutional and Sociocultural categories. However, future research should explicitly model these factors as distinct criteria to enable a more granular and dynamic risk assessment framework.

Also, the PF-AHP method, while effective in handling uncertainty and imprecision, assumes consistency in pairwise comparisons and does not account for dynamic changes over time. The static nature of the model means it captures risk priorities at a specific point in time and may not reflect evolving digital trade conditions, policy shifts, or technological advancements in the region. Regulatory reforms, technological breakthroughs, shifts in consumer trust, or geopolitical realignments can rapidly alter risk priorities, a limitation inherent to static MCDM models. The geographic scope is generalized across West Africa, overlooking intra-regional disparities in digital infrastructure, regulatory maturity, and consumer behavior among countries such as Nigeria, Ghana, Senegal, and Côte d’Ivoire. A more granular, country-level analysis would provide deeper insights into localized risk profiles and policy implications.

5. Conclusions

This study has systematically evaluated the emerging risks in China-West Africa digital trade collaboration using a novel Pythagorean Fuzzy AHP approach. By leveraging expert knowledge and fuzzy set theory, the methodology effectively handles the ambiguity and subjectivity often associated with cross-border risk assessment. The analysis reveals that while technological and institutional challenges such as inadequate infrastructure and regulatory fragmentation, are significant, sociocultural risks emerge as the most critical factor influencing the success of digital trade initiatives. This highlights the importance of understanding local consumer behavior, overcoming cultural resistance, and building digital trust, elements that are often overlooked in technology-driven development agendas. The ranking of risks provides a clear roadmap for stakeholders to allocate resources strategically, with emphasis on inclusive digital platforms, skills transfer, and culturally adaptive business models. Furthermore, the study reinforces the potential of South-South cooperation to evolve beyond traditional donor-recipient dynamics into innovation-driven, equitable partnerships. Future research could extend this framework by incorporating dynamic risk factors, longitudinal data, or comparative analyses across other African regions. However, this study lays a foundational approach for managing complexity in digital supply chains and supports the vision of a more resilient, inclusive, and sustainable digital economy in West Africa through strategic collaboration with global partners like China. For future studies, we shall extend this PF-AHP framework by incorporating geopolitical volatility, macroeconomic indicators for example, exchange rate risk, inflation, and environmental sustainability as independent risk dimensions to yield a more holistic evaluation of digital trade collaboration. Also given the fluid nature of digital globalization, future research could integrate longitudinal data, scenario-based forecasting, or hybrid models, for example, PF-AHP integration with system dynamics or machine learning to track how risk weights shift over time. Such innovations could significantly enhance the adaptive utility of this framework for real-world decision-making.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G.T. and S.Z.; methodology, M.G.T.; software, M.G.T.; validation, M.G.T., X.Y. and Q.X.; formal analysis, M.G.T.; investigation, S.Z.; resources, S.Z.; data curation, M.G.T.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G.T.; writing—review and editing, S.Z., X.Y., J.Z. and Q.X.; visualization, M.G.T.; supervision, S.Z.; project administration, S.Z.; funding acquisition, S.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Sichuan Social Science Planned Key Research Project (SCJ23ND61), the 2022 Central Chinese University Fundamental Research Program for Humanities and Social Science Cultivation Key Project (No. ZYGX2022FRJH004), and Regional funded Studies of the Ministry of Education of China (No. 2024-N01).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions and raw data presented in this study are included and referenced in this article. However, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhao, Y.; Feng, Y. Research on the Development and Influence on the Real Economy of Digital Finance: The Case of China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santarius, T.; Dencik, L.; Diez, T.; Ferreboeuf, H.; Jankowski, P.; Hankey, S.; Hilbeck, A.; Hilty, L.M.; Höjer, M.; Kleine, D.; et al. Digitalization and Sustainability: A Call for a Digital Green Deal. Environ. Sci. Policy 2023, 147, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zetzsche, D.A.; Anker-Sørensen, L.; Passador, M.L.; Wehrli, A. DLT-based enhancement of cross-border payment efficiency—A legal and regulatory perspective. Law Financ. Mark. Rev. 2021, 15, 70–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Wu, J.; Qiao, Y.; Yao, H. Government data governance framework based on a data middle platform. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 74, 289–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeks, R.; Gómez-Morantes, J.E.; Graham, M.; Howson, K.; Mungai, P.W.; Nicholson, B.; Van Belle, J.-P. Digital platforms and institutional voids in developing countries: The case of ride-hailing markets. World Dev. 2021, 145, 105528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Cheng, R.; Fei, J.; Khanal, R. Enhancing Digital Innovation Ecosystem Resilience through the Interplay of Organizational, Technological, and Environmental Factors: A Study of 31 Provinces in China Using NCA and fsQCA. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuypers, I.R.; Hennart, J.F.; Silverman, B.S.; Ertug, G. Transaction cost theory: Past progress, current challenges, and suggestions for the future. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2021, 15, 111–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauffman, C.; Goanta, C. A new order: The digital services act and consumer protection. Eur. J. Risk Regul. 2021, 12, 758–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badiane, K.; Lin, H.; Lee, H. Analysis of differences in business etiquette between China and Africa: The case of Senegal and Morocco. J. Educ. Issues 2022, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maditinos, D.; Chatzoudes, D.; Sarigiannidis, L. Factors affecting e-business successful implementation. Int. J. Commer. Manag. 2014, 24, 300–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.D. Concepts of Digital Economy and Industry 4.0 in Intelligent and Information Systems. Int. J. Intell. Netw. 2021, 2, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhao, S.; Wang, X.; Yao, Y. Study on the effect of digital economy on high-quality economic development in China. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumor, K.; Shurong, Z.; Dumor, H.K.; Ampaw, E.M.; Amouzou, E.K.; Okae-Adjei, S.; Boadi, E.K. Evaluating the effect of ICT on trade and economic growth from the perspective of Eastern African belt and road countries. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2023, 30, 452–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbebi, M. Exploring the human capital development dimensions of Chinese investments in Africa: Opportunities, implications and directions for further research. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 2019, 54, 189–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Gray, C.M.; Toombs, A.L.; Liu, C.; Liu, W. Building a Cross-Cultural UX Design Dual Degree. In With Design: Reinventing Design Modes; Bruyns, G., Wei, H., Eds.; IASDR 2021; Springer: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhartini, S.; Mahbubah, N.A.; Basjir, M. Development of SME’s business cooperation information technology system design. East.-Eur. J. Enterp. Technol. 2022, 6, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendricks, S.; Mwapwele, S.D. A systematic literature review on the factors influencing e-commerce adoption in developing countries. Data Inf. Manag. 2024, 8, 100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, A.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, F. How would the COVID-19 pandemic reshape retail real estate and high streets through acceleration of E-commerce and digitalization? J. Urban Manag. 2021, 10, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.L.; Hu, P.; Tsai, S.; Chen, X.D. The business analysis on the home-bias of E-commerce consumer behavior. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 21, 855–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, W.Y. Risk Perception Disparities in E-Business: Analyzing SME Roles, Experience and Legal Compliance Challenges. J. Enterp. Bus. Intell. 2024, 4, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.Z.; Fu, J.; Hu, F.; Xiang, Y.; Sun, Q. Dark side of enterprise social media usage: A literature review from the conflict-based perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 61, 102393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Xu, M.; Chen, X. Social media, gendered anxiety and disease-related misinformation: Discourses in contemporary China’s online anti-African sentiments. Asian J. Commun. 2021, 31, 485–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinonen, A.; Roto, V. Service Design Handover to user experience design—A systematic literature review. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2023, 154, 107087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putrevu, J.; Mertzanis, C. The adoption of digital payments in emerging economies: Challenges and policy responses. Digit. Policy, Regul. Gov. 2024, 26, 476–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunju, F.H. Digital Warfare: Exploring Cyber Criminality Amidst Armed Conflict in Southwest Region of Cameroon. J. Res. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2024, 3, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, A.; Sinha, S.K.; Govindan, K. Prioritizing risk mitigation strategies for environmentally sustainable clothing supply chains: Insights from selected organizational theories. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 28, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrai, M.A. Adaptive governance along Chinese-financed BRI railroad megaprojects in East Africa. World Dev. 2021, 141, 105388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danja, I.I.; Wang, X. Matching comparative advantages to special economic zones for sustainable industrialization. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Wang, J. Corporate governance, law, culture, environmental performance and CSR disclosure: A global perspective. J. Int. Financ. Mark. Inst. Money 2021, 70, 101264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, I.O.; Alhassan, M.D. Global e-readiness as a foundation for e-government and e-business development: The effect of political and regulatory environment. Int. J. Bus. Inf. Syst. 2023, 44, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adaileh, M.J.; Elrehail, H. E-Business Supply Chain Collaboration Measurement Scale: A Confirmatory Approach. Int. J. Supply Chain. Manag. 2018, 7, 22–34. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:216830091 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Yang, L.; Dong, J.; Yang, W. Analysis of Regional Competitiveness of China’s Cross-Border E-Commerce. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tamimu, M.G.; Chai, J. Dynamic Supply Chain Decision-Making of Live E-Commerce Considering Netflix Marketing Under Different Power Structures. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Yuan, J.; Li, T. Harmonizing digital trade for sustainable stride: Unveiling the industrial pollution reduction effect of China’s cross-border E-commerce comprehensive pilot zones. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedlund, H.J. Is China eroding the bargaining power of traditional donors in Africa. Int. Aff. 2017, 93, 389–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunhu, Y. Strategies of “Go Globe” for Chinese EPC. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lemi, D.I. Challenges and Opportunities of E-commerce in the African Market: A Case Analysis of Amazon.com. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2024, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osho, O.; Onuoha, C.I.; Ugwu, J.N.; Falaye, A.A. E-Commerce in Nigeria: A Survey of Security Awareness of Customers and Factors that Influence Acceptance. In Proceedings of the OcRI Conference, Ibadan, Nigeria, 7–9 September 2016; Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:2492494 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Zhao, S.; Tamimu, M.G.; Luo, A.; Sun, T.; Yang, Y. Hesitant Fuzzy-BWM Risk Evaluation Framework for E-Business Supply Chain Cooperation for China–West Africa Digital Trade. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadafi, T.M.; Decui, L.; Darko, A.P. Two stages method-based on Africa smart irrigation system assessment for willingness to pay: A case of Ghana Northern Region. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2025, 102, 102318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamimu, M.G.; Liang, D. Sustainable mining development in Ghana: An integrated AHP-TOPSIS-Manhattan distance approach. Resour. Policy 2025, 110, 105757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamimu, M.G.; Zhao, S.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Sun, T.; Luo, A. Fuzzy logic-BWM-based risk assessment for E-business cooperation in China-West Africa digital trade: A path to sustainable business and policies. Glob. Econ. Res. 2025, 1, 100014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadafi, T.M.; Musa, T. An integrated fuzzy-BWM-TOPSIS with Chebyshev distance approach for risk evaluation in e-business cooperation. Int. J. Manag. Fuzzy Syst. 2025, 11, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).