Exploring the Drivers of Content Entrepreneurs’ Compliance with Generative AI Policies: A Mixed-Methods Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Content Entrepreneurship

2.2. Generative AI

2.3. Deterrence Theory

| Study | Model Summary | Research Method | Major Finding(s) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variable(s) | Mediator(s) | Moderator(s) | Dependent Variable(s) | |||

| [35] | Deterrent certainty, Deterrent severity, Preventive security software, Motivational factors, Environmental factors | - | - | Computer abuse | Survey |

|

| [12] | Security policies, SETA program, Computer monitoring | Perceived sanction certainty, Perceived sanction severity | - | IS misuse intention | Hypothetical scenario research design |

|

| [17] | Severity of penalty, Certainty of detection, Normative beliefs, Peer behavior | - | - | IS security policy compliance intention | Survey |

|

| [10] | Detection probability, Sanction severity, Security risks, Perceived benefits, Personal norms (Moral beliefs) | - | Personal norms | Internet usage policy compliance intention | Survey |

|

| [38] | Neutralization techniques, Formal/informal sanctions, Shame | - | - | Intention to violate IS security policy | Hypothetical scenario research design |

|

| [36] | Formal/informal sanction certainty, Formal/informal sanction severity, Sanction celerity Perceived threat severity, Perceived threat susceptibility | Perceived self-efficacy, Perceived Response efficacy | - | IS security policy compliance intention | Hypothetical scenario research design |

|

| [39] | Neutralization techniques, Formal/informal sanction certainty, Formal/informal sanction severity | Shame, Intention to use shadow IT | - | Actual usage of shadow IT | Survey |

|

| [11] | Perceived sanction severity | Perceived self-efficacy, Perceived descriptive norm, Perceived response cost | Perceived self-efficacy, Perceived descriptive norm, Perceived response cost | IS security policy compliance intention | Survey |

|

| [37] | Formal/informal sanction certainty, Formal/informal sanction severity, Sanction celerity | - | Contextual moderators, Methodological moderators | Information security policy compliance behavior | Meta-analysis |

|

| [16] | Awareness of being monitored | Sanction severity, Sanction certainty, Sanction celerity | - | Computer usage policy compliance intention | Survey |

|

| [13] | Formal/informal sanction certainty, Formal/informal sanction severity, Shame, Moral beliefs, Neutralization techniques | - | Power distance, Uncertainty avoidance, Individualism vs. Collectivism | Intention to violate IS security policy | Hypothetical scenario research design |

|

| [14] | Fear, Anger | Formal/informal sanction certainty, Formal/informal sanction severity | - | Computer-related deviant behavioral intention | Hypothetical scenario research design |

|

| [15] | Perceived deterrent severity, Perceived deterrent certainty, Ethical leadership, Abusive supervision | - | - | IS security policy compliance intention | Hypothetical scenario research design |

|

| [40] | Organizational sanctions (sanction severity, sanction certainty, sanction celerity), Financial benefits, Self-control, Psychological contract violations | Organizational deterrence | Organizational deterrence, Self-control | Insider computer abuse | Survey |

|

| [41] | Formal/informal sanction severity, Formal/informal sanction certainty, Shame, Moral beliefs, Neutralization techniques | - | Gender | University students’ intention to misuse ChatGPT | Hypothetical scenario research design |

|

| This study | Peer communication | Perceived sanction certainty, severity, and celerity, Perceived social norm | Perceived social norm | Content entrepreneurs’ intention to comply with GenAI policies | Mixed-method approach |

|

3. Exploratory Study

3.1. Research Method

3.2. Interview Results

4. Quantitative Study

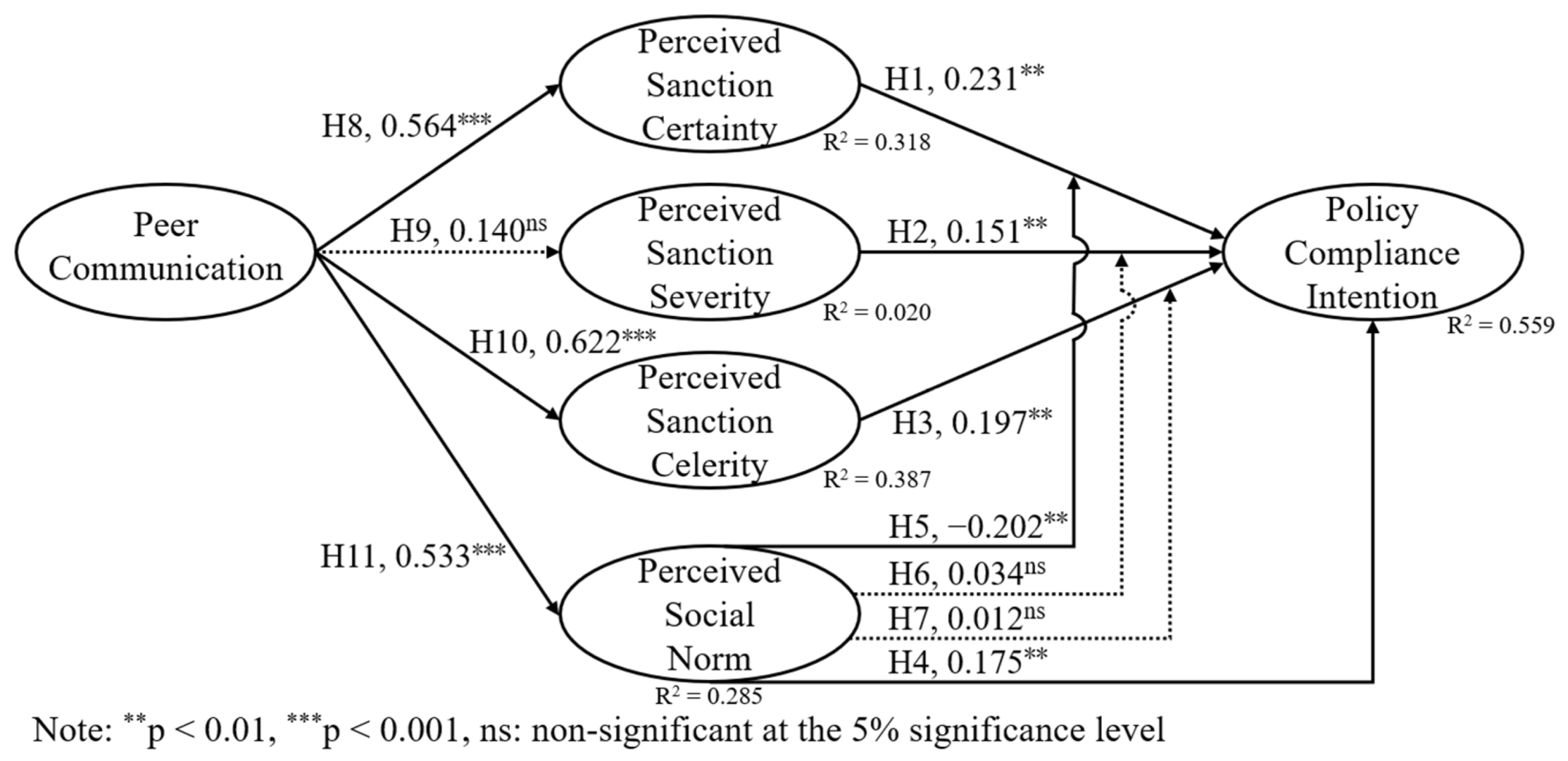

4.1. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

4.2. Research Method

4.3. Data Collection

4.4. Data Analysis and Results

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Key Findings

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fernandes, C.; Ferreira, J.J.; Veiga, P.M.; Kraus, S.; Dabić, M. Digital entrepreneurship platforms: Mapping the field and looking towards a holistic approach. Technol. Soc. 2022, 70, 101979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleier, A.; Fossen, B.L.; Shapira, M. On the role of social media platforms in the creator economy. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2024, 41, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Yang, Y.; Zhong, P. How does AI affect the self-actualization of content creators in dynamic environments? A knowledge management perspective. Technol. Soc. 2025, 81, 102855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Daily. China’s Booming Online Audio and Video Industry Tops 1 Billion Users. 28 March 2024. Available online: https://global.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202403/28/WS66057cb0a31082fc043bf44d.html (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Cillo, P.; Rubera, G. Generative AI in innovation and marketing processes: A roadmap of research opportunities. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2024, 53, 684–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, D.; Satornino, C.B.; Davenport, T.; Guha, A. How generative AI is shaping the future of marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2024, 53, 702–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Oh, C.; Kim, H.Y. AI vs. human-generated content and accounts on Instagram: User preferences, evaluations, and ethical considerations. Technol. Soc. 2024, 79, 102705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laine, J.; Minkkinen, M.; Mäntymäki, M. Understanding the ethics of generative AI: Established and new ethical principles. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2025, 56, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, E.A.S.; Osman, M.E.; Mohamed, B.A. The impact of artificial intelligence on social media content. J. Soc. Sci. 2024, 20, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Sarathy, R. Understanding compliance with internet use policy from the perspective of rational choice theory. Decis. Support Syst. 2010, 48, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wu, D.; Chen, L.; Teng, J.K.L. Sanction severity and employees’ information security policy compliance: Investigating mediating, moderating, and control variables. Inf. Manag. 2018, 55, 1049–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arcy, J.; Hovav, A.; Galletta, D.F. User awareness of security countermeasures and its impact on information systems misuse: A deterrence approach. Inf. Syst. Res. 2009, 20, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, A.; Siponen, M.T.; Straub, D.W. Effects of sanctions, moral beliefs, and neutralization on information security policy violations across cultures. Inf. Manag. 2020, 57, 103212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Luo, X.R.; Hsu, C. Anger or fear? Effects of discrete emotions on employee’s computer-related deviant behavior. Inf. Manag. 2020, 57, 103180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xu, J. Deterrence and leadership factors: Which are important for information security policy compliance in the hotel industry. Tour. Manag. 2021, 84, 104282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raddatz, N.I.; Marett, K.; Trinkle, B.S. The impact of awareness of being monitored on computer usage policy compliance: An agency view. J. Inf. Syst. 2020, 34, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herath, T.; Rao, H.R. Encouraging information security behaviors in organizations: Role of penalties, pressures and perceived effectiveness. Decis. Support Syst. 2009, 47, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Brown, S.A.; Bala, H. Bridging the qualitative-quantitative divide: Guidelines for conducting mixed methods research in information systems. MIS Q. 2013, 37, 21–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Brown, S.A.; Sullivan, Y.W. Guidelines for conducting mixed-methods research: An extension and illustration. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2016, 17, 435–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafesse, W.; Dayan, M. Content creators’ participation in the creator economy: Examining the effect of creators’ content sharing frequency on user engagement behavior on digital platforms. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 73, 103357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y. Content marketing in the social media platform: Examining the effect of content creation modes on the payoff of participants. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 77, 103629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstetter, R.; Gollnhofer, J.F. The creator’s dilemma: Resolving tensions between authenticity and monetization in social media. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2024, 41, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edeling, A.; Wies, S. Embracing entrepreneurship in the creator economy: The rise of creatrepreneurs. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2024, 41, 436–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres, R.; Schreier, M.; Schweidel, D.A.; Sorescu, A. The creator economy: An introduction and a call for scholarly research. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2024, 41, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, W.; Zeng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.; Fan, W. What makes user-generated content more helpful on social media platforms? Insights from creator interactivity perspective. Inf. Process. Manag. 2023, 60, 103201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amankwah-Amoah, J.; Abdalla, S.; Mogaji, E.; Elbanna, A.; Dwivedi, Y.K. The impending disruption of creative industries by generative AI: Opportunities, challenges, and research agenda. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2024, 79, 102759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żyminkowska, K.; Zachurzok-Srebrny, E. The role of artificial intelligence in customer engagement and social media marketing—Implications from a systematic review for the tourism and hospitality sectors. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sætra, H.S. Generative AI: Here to stay, but for good? Technol. Soc. 2023, 75, 102372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordella, A.; Gualdi, F. Regulating generative AI: The limits of technology-neutral regulatory frameworks. Insights from Italy’s intervention on ChatGPT. Gov. Inf. Q. 2024, 41, 101982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Sheng, D.; Zhou, Z.; Wu, Y. AI hallucination: Towards a comprehensive classification of distorted information in artificial intelligence-generated content. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovari, A.; De Rosa, F. Exploring the challenges of generative AI on public sector communication in Europe. Media Commun. 2025, 13, 9644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, B.; Bao, L. Generative artificial intelligence policies: Information governance. Manag. Decis. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, J. Assessing the deterrence doctrine: A challenge for the social and behavioral sciences. Am. Behav. Sci. 1979, 22, 653–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, E.S.; Loftus, T.C. Integration of certainty, severity, and celerity information in judged deterrence value: Further evidence and methodological equivalence. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 26, 226–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, D.W. Effective IS security: An empirical study. Inf. Syst. Res. 1990, 1, 255–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, A.C.; Warkentin, M.; Siponen, M. An enhanced fear appeal rhetorical framework: Leveraging threats to the human asset through sanctioning rhetoric. MIS Q. 2015, 39, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trang, S.; Brendel, B. A Meta-analysis of deterrence theory in information security policy compliance research. Inf. Syst. Front. 2019, 21, 1265–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siponen, M.; Vance, A. Neutralization: New insights into the problem of employee information systems security policy violations. MIS Q. 2010, 34, 487–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silic, M.; Barlow, J.B.; Back, A. A new perspective on neutralization and deterrence: Predicting shadow IT usage. Inf. Manag. 2017, 54, 1023–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, A.J.; Roberts, T.L.; Posey, C.; Lowry, P.B.; Fuller, B. Going beyond deterrence: A middle-range theory of motives and controls for insider computer abuse. Inf. Syst. Res. 2023, 34, 342–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, S.; Chauhan, S.; Motiwalla, L. Examining business students’ intentions to misuse ChatGPT through the lens of deterrence and neutralisation theories. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gentles, S.J.; Charles, C.; Ploeg, J.; McKibbon, K. Sampling in qualitative research: Insights from an overview of the methods literature. Qual. Rep. 2015, 20, 1772–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuetz, S.W.; Gewald, H.; Johnston, A.C.; Thatcher, J.B. What goals drive employees’ information systems security behaviors? A mixed methods study of employees’ goals in the workplace. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2025, 26, 1390–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-W.; Kankanhalli, A.; Lee, H.-L. Investigating decision factors in mobile application purchase: A mixed-methods approach. Inf. Manag. 2016, 53, 727–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wu, Y.C. Balancing innovation and regulation in the age of generative artificial intelligence. J. Inf. Policy 2024, 14, 385–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, U.E. Evaluating alignment in large language models: A review of methodologies. AI Ethics 2025, 5, 3233–3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G.S. Crime and punishment: An economic approach. J. Political Econ. 1968, 76, 169–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.G.; Newquist, S.C.; Schatz, R.W. Reputation and its risks. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2007, 85, 104–114. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, T.C.; Turanovic, J.J. Celerity and deterrence. In Deterrence, Choice, and Crime; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory; Prentice Hall Press: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Goldstein, N.J. Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2004, 55, 591–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paternoster, R.; Simpson, S. Sanction threats and appeals to morality: Testing a rational choice model of corporate crime. Law Soc. Rev. 1996, 30, 549–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yu, C.; Wei, Y. Social media peer communication and impacts on purchase intentions: A consumer socialization framework. J. Interact. Mark. 2012, 26, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.-M.H.; Ngoc, B.M. Consumption-related social media peer communication and online shopping intention among Gen Z consumers: A moderated-serial mediation model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 153, 108100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, L.R.; Muralidharan, S. Understanding social media peer communication and organization–public relationships: Evidence from China and the United States. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2016, 94, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geber, S.; Baumann, E.; Klimmt, C. Where do norms come from? Peer communication as a factor in normative social influences on risk behavior. Commun. Res. 2019, 46, 708–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrigan, M.; Feddema, K.; Wang, S.; Harrigan, P.; Diot, E. How trust leads to online purchase intention founded in perceived usefulness and peer communication. J. Consum. Behav. 2021, 20, 1297–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W.; Marcolin, B.L.; Newsted, P.R. A partial least squares latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: Results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic-mail emotion/adoption study. Inf. Syst. Res. 2003, 14, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Marking Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, P.M. Common method bias in marketing: Causes, mechanisms, and procedural remedies. J. Retail. 2012, 88, 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan, J. How OpenAI’s text-to-video tool Sora could change science-and society. Nature 2024, 627, 475–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagin, D.S. Criminal deterrence research at the outset of the twenty-first century. Crime Justice 1998, 23, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, H. The impact of generative AI on management innovation. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2025, 44, 100767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| # of Participant | Key Interview Quotes |

|---|---|

| #1 (Male, 22 years old, 2 years of content creation experience, primarily using deepseek) |

|

| |

| #2 (Male, 56 years old, 6 months of content creation experience, primarily using deepseek and Doubao) |

|

| |

| #3 (Female, 22 years old, 3 years of content creation experience, primarily using Doubao) |

|

| |

| #4 (Female, 39 years old, 3.5 years of content creation experience, primarily using KIMI and deepseek) |

|

| |

| #5 (Male, 30 years old, 5 years of content creation experience, primarily using Doubao) |

|

| |

| #6 (Female, 48 years old, 10 months of content creation experience, primarily using deepseek and ERNIE) |

|

| |

| #7 (Male, 26 years old, 5 months of content creation experience, primarily using deepseek and Doubao) |

|

|

| Constructs | Items | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Peer Communication | 1. I discuss GenAI usage with my peers. | [56] |

| 2. I ask my peers for advice about GenAI usage. | ||

| 3. I obtain information about GenAI usage from my peers. | ||

| 4. I talk with my peers about using GenAI for content creation. | ||

| Perceived Sanction Certainty | 1. I am likely to incur sanctions if I violate GenAI policies. | [15,40] |

| 2. Sanctions will follow if GenAI policies are violated. | ||

| 3. If caught committing a GenAI policy violation, the probability of sanction would be high. | ||

| 4. It is likely that I would be punished if I were caught violating GenAI policies. | ||

| Perceived Sanction Severity | 1. It is likely that the punishment would be severe if I violate GenAI policies. | [15,40] |

| 2. Sanctions for violations of GenAI policies would be severe. | ||

| 3. If I were caught violating GenAI policies, the sanctions would be very severe. | ||

| 4. If I violate GenAI policies, the sanctions would put me in serious trouble. | ||

| Perceived Sanction Celerity | 1. The punishment from GenAI policy violation would be swift. | [36,40] |

| 2. I would be punished quickly for GenAI policy violation. | ||

| 3. Sanctions for GenAI policy violation would be delivered quickly. | ||

| 4. Punishment to GenAI policy violations would be instantaneous. | ||

| Perceived Social Norm | 1. I believe that other peers comply with the GenAI policies. | [11,17] |

| 2. It is likely that the majority of other peers comply with the GenAI policies. | ||

| 3. I am convinced that other peers comply with the GenAI policies. | ||

| Policy Compliance Intention | 1. I intend to comply with the requirements of GenAI polices in the future. | [15,16] |

| 2. I intend to perform my responsibilities prescribed in the GenAI policies. | ||

| 3. I am likely to follow the GenAI policies. | ||

| 4. I intend to comply with the GenAI policies. |

| Category | Item | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 112 | 67.1 |

| Female | 55 | 32.9 | |

| Age | 18–19 | 4 | 2.4 |

| 20–29 | 83 | 49.7 | |

| 30–39 | 62 | 37.1 | |

| >39 | 18 | 10.8 | |

| Education | High school or lower | 29 | 17.4 |

| Bachelor’s or college degree | 135 | 80.8 | |

| Graduate degree | 3 | 1.8 | |

| Industry Sector | Service | 50 | 29.9 |

| Manufacturing | 37 | 22.2 | |

| Agriculture | 3 | 1.8 | |

| Student | 16 | 9.6 | |

| Others | 61 | 36.5 | |

| Duration of Content Creation | ≤12 Months | 6 | 3.6 |

| 13–24 Months | 62 | 37.1 | |

| 25–36 Months | 71 | 42.5 | |

| >36 Months | 28 | 16.8 | |

| Frequently Used GenAI | Doubao | 87 | 52.1 |

| deepseek | 24 | 14.4 | |

| ERNIE | 14 | 8.4 | |

| ChatGPT | 8 | 4.8 | |

| Others | 34 | 20.3 | |

| Total | - | 167 | 100 |

| Construct | Indicator | Standardized Loading | CR | AVE | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peer Communication | PC1 | 0.843 | 0.858 | 0.696 | 0.853 |

| PC2 | 0.881 | ||||

| PC3 | 0.854 | ||||

| PC4 | 0.753 | ||||

| Perceived Sanction Certainty | SCer1 | 0.837 | 0.884 | 0.738 | 0.882 |

| SCer2 | 0.870 | ||||

| SCer3 | 0.881 | ||||

| SCer4 | 0.849 | ||||

| Perceived Sanction Severity | SSev1 | 0.887 | 0.912 | 0.786 | 0.909 |

| SSev2 | 0.894 | ||||

| SSev3 | 0.893 | ||||

| SSev4 | 0.871 | ||||

| Perceived Sanction Celerity | SCel1 | 0.881 | 0.876 | 0.724 | 0.873 |

| SCel2 | 0.883 | ||||

| SCel3 | 0.813 | ||||

| SCel4 | 0.825 | ||||

| Perceived Social Norm | PSN1 | 0.896 | 0.858 | 0.778 | 0.857 |

| PSN2 | 0.878 | ||||

| PSN3 | 0.872 | ||||

| Policy Compliance Intention | PCI1 | 0.895 | 0.912 | 0.789 | 0.911 |

| PCI2 | 0.872 | ||||

| PCI3 | 0.903 | ||||

| PCI4 | 0.884 |

| Construct | Mean | S.D. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Perceived Sanction Celerity | 5.400 | 0.987 | 0.851 | |||||

| 2. Perceived Sanction Certainty | 5.523 | 1.047 | 0.608 | 0.859 | ||||

| 3. Policy Compliance Intention | 5.647 | 0.961 | 0.583 | 0.597 | 0.888 | |||

| 4. Peer Communication | 5.801 | 1.034 | 0.622 | 0.564 | 0.611 | 0.834 | ||

| 5. Perceived Sanction Severity | 5.421 | 1.095 | 0.133 | 0.093 | 0.269 | 0.140 | 0.886 | |

| 6. Perceived Social Norm | 5.597 | 0.925 | 0.581 | 0.597 | 0.572 | 0.533 | 0.148 | 0.882 |

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Perceived Sanction Celerity | - | |||||

| 2. Perceived Sanction Certainty | 0.691 | - | ||||

| 3. Policy Compliance Intention | 0.653 | 0.665 | - | |||

| 4. Peer Communication | 0.720 | 0.648 | 0.694 | - | ||

| 5. Perceived Sanction Severity | 0.150 | 0.104 | 0.295 | 0.159 | - | |

| 6. Perceived Social Norm | 0.666 | 0.683 | 0.647 | 0.620 | 0.169 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lou, L.; Jiao, Y.; Koh, J.; Dai, W. Exploring the Drivers of Content Entrepreneurs’ Compliance with Generative AI Policies: A Mixed-Methods Approach. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 284. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040284

Lou L, Jiao Y, Koh J, Dai W. Exploring the Drivers of Content Entrepreneurs’ Compliance with Generative AI Policies: A Mixed-Methods Approach. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2025; 20(4):284. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040284

Chicago/Turabian StyleLou, Liguo, Yongbing Jiao, Joon Koh, and Weihui Dai. 2025. "Exploring the Drivers of Content Entrepreneurs’ Compliance with Generative AI Policies: A Mixed-Methods Approach" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 20, no. 4: 284. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040284

APA StyleLou, L., Jiao, Y., Koh, J., & Dai, W. (2025). Exploring the Drivers of Content Entrepreneurs’ Compliance with Generative AI Policies: A Mixed-Methods Approach. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 20(4), 284. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040284