Abstract

Type I interferons (IFN), immediately triggered following most viral infections, play a pivotal role in direct antiviral immunity and act as a bridge between innate and adaptive immune responses. However, numerous viruses have evolved evasion strategies against IFN responses, prompting the exploration of therapeutic alternatives for viral infections. Within the type I IFN family, 12 IFNα subtypes exist, all binding to the same receptor but displaying significant variations in their biological activities. Currently, clinical treatments for chronic virus infections predominantly rely on a single IFNα subtype (IFNα2a/b). However, the efficacy of this therapeutic treatment is relatively limited, particularly in the context of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection. Recent investigations have delved into alternative IFNα subtypes, identifying certain subtypes as highly potent, and their antiviral and immunomodulatory properties have been extensively characterized. This review consolidates recent findings on the roles of individual IFNα subtypes during HIV and Simian Immunodeficiency Virus (SIV) infections. It encompasses their induction in the context of HIV/SIV infection, their antiretroviral activity, and the diverse regulation of the immune response against HIV by distinct IFNα subtypes. These insights may pave the way for innovative strategies in HIV cure or functional cure studies.

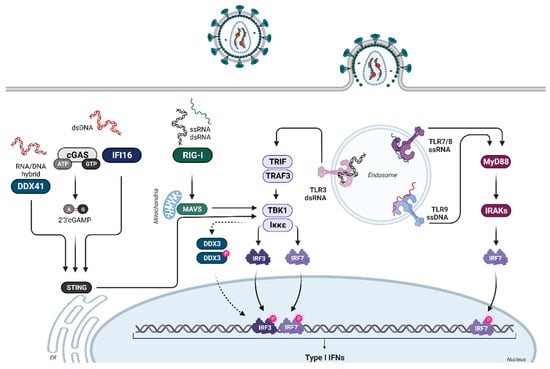

1. Introduction

Type I interferons (IFN) belong to a pleiotropic cytokine family and are rapidly induced by viral infections. They bind to their ubiquitously expressed IFNα/β receptor (IFNAR), consisting of the two subunits, IFNAR1 and IFNAR2. This binding activates the classical Jak (Janus kinases)-STAT (signal transducers and activators of transcription proteins) signaling cascade, which leads to the transcription of hundreds of IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs). During infection with certain viruses, specific patterns of ISGs are expressed, resulting in distinct antiviral activities for each virus [1]. These activities include the expression of directly acting ISGs, so-called viral restriction factors, as well as the repression of cellular dependency factors, so-called IFN-repressed genes (IRepGs) [2,3,4]. In addition to these more direct antiviral effects, type I IFNs also modulate virus-specific innate and adaptive immune responses by promoting the differentiation and activation of innate and adaptive immune cells.

Type I IFNs belong to a multigene family consisting of several IFNα subtypes but only one IFNβ, IFNε, IFNκ, and IFNω (human), or limitin (mouse) [5]. IFNα subtype genes exist in all vertebrates [6,7], and they likely developed from an ancestor IFNA-like gene by gene conversion and duplication [6,7]. All 13 human IFNA subtype genes (IFNA1, IFNA2, IFNA4, IFNA5, IFNA6, IFNA7, IFNA8, IFNA10, IFNA13, IFNA14, IFNA16, IFNA17, and IFNA21) are located on chromosome 9 [8,9,10] and encode for 12 different IFNα subtype proteins, with identical sequences of mature IFNα1 and IFNα13, thus referred to here as IFNα1. The human IFNα subtypes have similarities in structure: they lack introns, they have similar protein lengths (165–166 amino acids), and their protein sequences are highly conserved (75–99% amino acid sequence identity) [11,12]. The IFNα subtypes all bind to the same IFNα/β receptor, but they differ in their binding affinity to both receptor subunits [13]. This may be associated with differences in downstream signaling events, including the phosphorylation of distinct STAT molecules and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK), which were reported after stimulation of cells with individual subtypes [14,15]. Furthermore, there is growing evidence that cell type specificities, the microenvironment, receptor avidity, timing, and fine-tuning of downstream signaling events, all contribute to the complex biology of IFNα subtypes [16,17]. This ultimately results in distinct antiviral and immunomodulatory properties of individual subtypes in different viral infections [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. Here, we summarize the growing body of literature on the biological role of IFNα subtypes in retroviral infections, with a special focus on HIV and SIV infections. Specifically, in this review, we discuss the induction of IFNα subtype expression by retroviruses, their antiretroviral capacity, and their impact on innate and adaptive immune responses against retroviruses.

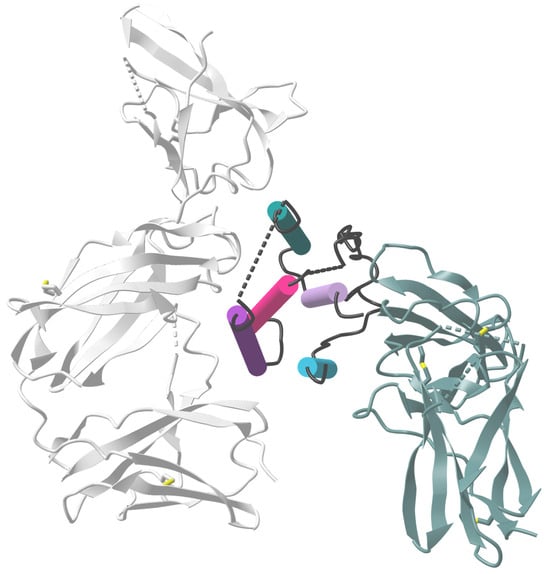

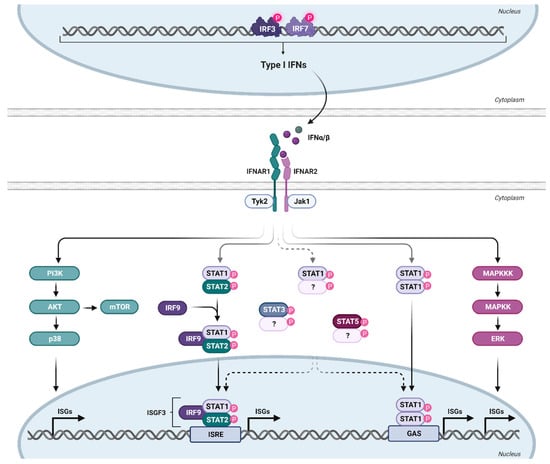

3. IFNα Subtype-Mediated Downstream Signaling and ISG Expression Pattern during HIV Infection

The expressed and secreted IFNα subtypes all bind to a common heterodimeric type I IFN receptor, consisting of the subunits IFNAR1 and IFNAR2. In general, IFNα subtypes have a higher binding affinity to IFNAR2 (KD: 0.4–5 nM; except for IFNα1—220 nM) than to IFNAR1 (KD 0.5–5 µM) [13], indicating an initial binding to IFNAR2, which then recruits IFNAR1 to form the ternary complex [43,44]. The different subtypes have various binding affinities to both receptor subunits; however, the binding affinities do not necessarily reflect the antiviral activity (tested against VSV or EMCV) of the individual subtypes [13]. The binding affinities to IFNAR2 are comparable for all subtypes, with the exception of IFNα1, with a binding affinity that is more than 130-fold lower compared to IFNα2 [13]. The product of the binding affinities to both receptor subunits (IFNAR1 and IFNAR2) of IFNα2, IFNα4, IFNα5, IFNα10, IFNα17, and IFNα21 are comparable, whereas the subtypes IFNα7, IFNα8, and IFNα16 have a three to four times higher binding affinity, and IFNα6 and IFNα14 have an eight times higher binding affinity compared to IFNα2. The two outliers are IFNα1 and IFNβ, with an affinity that is 40 times lower and 1000 times higher, respectively, than that of IFNα2 [44]. The formation of the ternary complex leads to the activation of the canonical JAK-STAT pathway, although signaling through IFNAR1 alone by IFNβ has recently also been suggested [45]. Since IFNAR lacks intrinsic kinase activity, it relies on the receptor-associated protein JAK1 and tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) to phosphorylate STAT1 and STAT2 [46], followed by the heterodimerization of STAT1-STAT2, which recruits IRF9 to form the IFN-stimulated gene factor 3 (ISGF3) complex (Figure 2). ISGF3 then translocates into the nucleus, where it binds to a conserved genomic sequence motif (about 15 bp), called the IFN-stimulated response element (ISRE), located in the promoter region of numerous IFN-stimulated genes [47,48]. IRF9 is a key factor for transcriptional regulation, as it provides the specificity for binding to ISRE, which regulates the transcription of hundreds of ISGs and thereby the establishment of an antiviral state in cells or even whole organs [49]. Recently, the homeostatic chromatin state of ISRE was shown to be cell type-specific, resulting in cell type-specific differences in ISRE binding patterns upon IFN stimulation [50].

Figure 2.

Type I IFN signaling. Binding of type I IFN to the ubiquitously expressed IFNα/β receptor triggers the activation of various signaling cascades. IFNAR consists of the subunits IFNAR1 and IFNAR2, with a higher affinity of IFN for IFNAR2. This leads to initial IFNAR2 binding, followed by IFNAR1 recruitment to form the ternary complex. For canonical signaling, phosphorylation of the receptor unit by Janus kinases (Tyk2 and Jak1) activates transcription factors STAT1 and STAT2, forming together with IRF9 the trimeric ISGF3 complex. ISGF3 translocates to the nucleus, binding to ISRE and inducing the transcription of numerous ISGs. Apart from the canonical JAK-STAT signaling pathway, other non-classical signaling cascades downstream of the IFNAR are also activated upon IFN binding. Created with BioRender.com.

The antiviral state in cells is mainly induced by the canonical signaling pathway described above, which results in the expression of many ISGs that contribute to IFN-specific biological activity [51]. However, IFNα can also signal through non-canonical pathways (Figure 2). The activation of these non-canonical pathways may lead to profound differences in ISG expression patterns [52]. STAT1-STAT1 homodimers or other STAT dimers, such as STAT3, and STAT5A, can be activated by IFNα subtypes and are part of STAT-dependent non-canonical pathways. STAT4 and STAT6 appear to be restricted to certain cell types but can also be activated by IFNα [53,54]. These complexes, especially STAT1 homodimers, can bind to the IFNγ-activated site (GAS) element, which is present in the promoter region of certain ISGs [55]. Some ISGs only have ISRE or GAS elements in their promoter region; however, some ISGs have both elements, indicating that the ISG pattern induced by individual IFNα subtypes may vary according to their STAT signaling and promoter element activation [53]. We showed, for example, that IFNα14 induces STAT1:STAT2 heterodimer signaling as well as STAT1:STAT1 homodimer activation of GAS elements [24]. This combined type I and II IFN signaling resulted in the induction of 844 ISGs in hepatoma cells, whereas the only canonical type I IFN signaling by IFNα2 induces only 325 ISGs. This large set of additionally induced ISGs by the IFNα14 subtype was at least correlated with its strong antiviral activity against HIV [56] and HBV [24]. Similar findings were made in HIV target cells, human lamina propria CD4+ T cells [57]. Here, IFNα2 induced only 302 ISGs (including 266 core ISGs expressed by all five tested IFNα subtypes in the study), whereas the more antiviral IFNα14 induced a large number of 509 additional ISGs measured by RNA sequencing technology. In addition to the STAT signaling pathways, STAT-independent downstream signaling, such as MAPK and phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3K), showed activation upon type I IFN binding to IFNAR [58]. The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway, which mediates mRNA translation, can be activated downstream of the PI3K/AKT pathway [53]. Also downstream of this pathway is p38, which is rapidly activated in response to IFNα, without modifying the activation of the STAT pathway, and has been demonstrated to be crucial for the antiviral function of IFN [59]. Another non-canonical pathway is the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling cascade. In contrast to p38 downstream signaling, this pathway has not yet been investigated thoroughly [60]. However, cell-specific activation of this pathway upon IFNα treatment has been demonstrated [61]. Interestingly, HIV has been shown to use both pathways (p38 and ERK) to deplete CD4+ T cells from the immune system as well as to produce new virions [62], indicating a potential influence of IFN on T cell depletion or viral replication. However, IFNα has been shown to inhibit HIV latency and even reverse established latency in a STAT1-, STAT3-, and/or STAT5-dependent manner, independent of NFκB activation [63].

To analyze changes in signaling pathways, researchers often investigate posttranslational modifications (PTMs), especially phosphorylation, since they are important in signal transduction and many cellular processes (reviewed in [64]). Currently, the characterization and quantification of phosphorylated peptides and proteins are performed using well-established high-throughput MS-based phosphoproteomics, which has proven to be particularly useful for simultaneously monitoring numerous phosphoproteins within different signaling networks [65]. Phosphoproteomics has been used successfully to screen for primary human CD4+ T cells after HIV-1 infection, resulting in a global view of the signaling events induced during the first minute of HIV-1 entry [66]. Other ways to analyze the phosphorylation of signaling events in a more targeted manner are using phosphoflow cytometry or western blots. Phosphoflow analysis of T and NK cells revealed strong differences in STAT1 and STAT5 phosphorylation after treatment with IFNα2, IFNα14, and IFNβ. IFNα14 and the high-affinity IFNβ significantly increased the frequencies of phosphorylated STAT1, STAT3, and STAT5 in the gut- and blood-derived T and NK cells, whereas a higher activation of pSTAT5 was observed in PBMCs and a higher STAT1 phosphorylation in LPMCs. Additionally, significant differences in the phosphorylation of STAT5 were observed in both healthy and HIV-infected individuals, indicating an IFNα subtype-specific potency to stimulate T and NK cell responses during HIV-1 [67]. In addition, western blot analysis of IFN-stimulated murine CD8+ T cells demonstrated strong phosphorylation of STAT1 and STAT2 by murine IFNα6 and IFNα11, which was completely undetectable in CD8+ T cells after stimulation with murine IFNα1 and IFNα2 [68]. Furthermore, tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT1 was also induced in response to murine IFNα1, IFNα2, IFNα4, and IFNα5 in J2E erythroid cells, while tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3 was induced only in response to IFNα1. This indicates cell-type-specific differences in the activation of different STAT molecules by various IFNα subtypes.

All of the above demonstrates the complexity of the downstream signaling of IFNα and suggests that there may still be undefined mechanisms that mediate cellular IFN responses. Also, a more detailed understanding of how infections such as SIV/HIV utilize these pathways to their benefit is needed, which may provide insights into their pathogenesis. Finally, further characterization of each IFNα subtype and activation of downstream signaling cascades is needed, since this may provide important insight on their antiviral and immunomodulatory diversity.

6. Concluding Remarks

When type I IFNs were discovered, many scientists believed that they represented the golden bullet against many infections. However, 67 years later, many features, especially of IFNα subtypes, are still unknown. One problem was that a lot of data on the clinically approved IFNα2 was generated, whereas the other subtypes were largely ignored. Also, the role of IFNα subtypes in HIV infection has only recently been studied. We discuss here that the induction of individual IFNα subtypes during retroviral infection is a very complex process, most likely influenced by many parameters, including the infected cell type, the infecting virus strain, and pathways of viral sensing. More research is needed to better define this multiparameter process because it is very important for intrinsic as well as innate immunity against HIV. Also very relevant for these initial arms of HIV immunity are the signaling pathways that individual IFNα subtypes induce in HIV target cells. Preliminary research on this topic clearly shows that there is much more than the canonical STAT1:STAT2 signaling pathway. Several other signaling pathways are involved, depending on the specific IFNα subtype used for the stimulation of a cell. The different signaling pathways shape the pattern of ISGs that are expressed. Since several of these ISGs are well-known HIV restriction factors or influence innate immunity against HIV, the IFN-induced ISG pattern is most likely crucial to preventing the establishment of HIV infection upon exposure. Thus, it is of utmost importance to understand these IFN-mediated mechanisms because they might provide new tools to prevent HIV infections. After an HIV infection has been established, IFNα subtypes are still very important because they also positively influence the adaptive immune response against HIV, which is very important to provide a time period of virus control. However, during chronic HIV infection, type I IFN responses and IFN treatment have also been associated with hyperimmune activation, T cell dysfunction, inefficient virus control, and CD4+ T cell depletion. Recent studies suggest that this might be more associated with IFNβ than IFNα subtypes. However, the therapeutic potential of each IFNα subtype against acute and chronic HIV infection has to be thoroughly tested, and it is not unlikely that some subtypes may have a more beneficial effect, whereas others may have a more detrimental effect. So far, IFNα14 seems to have outstanding potential for anti-HIV activity. Even with this data at hand, one can still question if IFNα subtypes will ever be used for HIV therapy since we have a very potent and effective ART in clinical use. However, ART does not induce HIV cure or functional cure. HIV cure strategies usually aim to develop combination therapies that reactivate the latent virus from the reservoir, stop its replication with ART, and strengthen immunity to then control or eliminate the virus. For such cure strategies, IFNα subtypes might be important, as it has been shown that they can reactivate latent HIV and stimulate potent antiviral immune responses, so they fulfill two of the requirements for HIV cure. These are interesting possibilities for the therapeutic application of IFNα subtypes in HIV infection, but before such applications can be established, more research on IFNα subtypes, which we missed carrying for almost 60 years, is needed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.S., U.D. and B.S.; writing—original draft preparation, K.S., Z.K., U.D. and M.I.; writing—review and editing, K.S., Z.K., U.D. and B.S.; visualization, Z.K.; funding acquisition, K.S., U.D. and B.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the German Research Foundation [priority program SPP1923 to K.S. (SU1030/1-2), U.D. (DI714/18-2) and B.S. (SI-1785/2-2)].

Data Availability Statement

This review article does not contain new data to make available.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Duisburg-Essen.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Schoggins, J.W.; Wilson, S.J.; Panis, M.; Murphy, M.Y.; Jones, C.T.; Bieniasz, P.; Rice, C.M. A diverse range of gene products are effectors of the type I interferon antiviral response. Nature 2011, 472, 481–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trilling, M.; Bellora, N.; Rutkowski, A.J.; de Graaf, M.; Dickinson, P.; Robertson, K.; da Costa, O.P.; Ghazal, P.; Friedel, C.C.; Alba, M.M.; et al. Deciphering the modulation of gene expression by type I and II interferons combining 4sU-tagging, translational arrest and in silico promoter analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, 8107–8125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megger, D.A.; Philipp, J.; Le-Trilling, V.T.K.; Sitek, B.; Trilling, M. Deciphering of the Human Interferon-Regulated Proteome by Mass Spectrometry-Based Quantitative Analysis Reveals Extent and Dynamics of Protein Induction and Repression. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sertznig, H.; Roesmann, F.; Wilhelm, A.; Heininger, D.; Bleekmann, B.; Elsner, C.; Santiago, M.; Schuhenn, J.; Karakoese, Z.; Benatzy, Y.; et al. SRSF1 acts as an IFN-I-regulated cellular dependency factor decisively affecting HIV-1 post-integration steps. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 935800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Pesch, V.; Lanaya, H.; Renauld, J.C.; Michiels, T. Characterization of the murine alpha interferon gene family. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 8219–8228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woelk, C.H.; Frost, S.D.; Richman, D.D.; Higley, P.E.; Kosakovsky Pond, S.L. Evolution of the interferon alpha gene family in eutherian mammals. Gene 2007, 397, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Yang, L.; Liu, W. Distinct evolution process among type I interferon in mammals. Protein Cell 2013, 4, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz, M.O.; Pomykala, H.M.; Bohlander, S.K.; Maltepe, E.; Malik, K.; Brownstein, B.; Olopade, O.I. Structure of the human type-I interferon gene cluster determined from a YAC clone contig. Genomics 1994, 22, 540–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genin, P.; Lin, R.; Hiscott, J.; Civas, A. Differential regulation of human interferon A gene expression by interferon regulatory factors 3 and 7. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2009, 29, 3435–3450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freaney, J.E.; Zhang, Q.; Yigit, E.; Kim, R.; Widom, J.; Wang, J.P.; Horvath, C.M. High-density nucleosome occupancy map of human chromosome 9p21-22 reveals chromatin organization of the type I interferon gene cluster. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2014, 34, 676–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, M.P.; Owczarek, C.M.; Jermiin, L.S.; Ejdebäck, M.; Hertzog, P.J. Characterization of the type I interferon locus and identification of novel genes. Genomics 2004, 84, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwarthoff, E.C.; Mooren, A.T.; Trapman, J. Organization, structure and expression of murine interferon alpha genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985, 13, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoie, T.B.; Kalie, E.; Crisafulli-Cabatu, S.; Abramovich, R.; DiGioia, G.; Moolchan, K.; Pestka, S.; Schreiber, G. Binding and activity of all human alpha interferon subtypes. Cytokine 2011, 56, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cull, V.S.; Tilbrook, P.A.; Bartlett, E.J.; Brekalo, N.L.; James, C.M. Type I interferon differential therapy for erythroleukemia: Specificity of STAT activation. Blood 2003, 101, 2727–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakoese, Z.; Le-Trilling, V.T.; Schuhenn, J.; Francois, S.; Lu, M.; Liu, J.; Trilling, M.; Hoffmann, D.; Dittmer, U.; Sutter, K. Targeted mutations in IFNalpha2 improve its antiviral activity against various viruses. mBio 2023, 14, e02357-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasello, E.; Pollet, E.; Vu Manh, T.P.; Uze, G.; Dalod, M. Harnessing Mechanistic Knowledge on Beneficial Versus Deleterious IFN-I Effects to Design Innovative Immunotherapies Targeting Cytokine Activity to Specific Cell Types. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll, H.P.; Maier, T.; Zommer, A.; Lavoie, T.; Brostjan, C. The differential activity of interferon-alpha subtypes is consistent among distinct target genes and cell types. Cytokine 2011, 53, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbert, K.; Joedicke, J.J.; Meryk, A.; Trilling, M.; Francois, S.; Duppach, J.; Kraft, A.; Lang, K.S.; Dittmer, U. Interferon-alpha subtype 11 activates NK cells and enables control of retroviral infection. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerlach, N.; Gibbert, K.; Alter, C.; Nair, S.; Zelinskyy, G.; James, C.M.; Dittmer, U. Anti-retroviral effects of type I IFN subtypes in vivo. Eur. J. Immunol. 2009, 39, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scagnolari, C.; Trombetti, S.; Selvaggi, C.; Carbone, T.; Monteleone, K.; Spano, L.; Di Marco, P.; Pierangeli, A.; Maggi, F.; Riva, E.; et al. In vitro sensitivity of human metapneumovirus to type I interferons. Viral Immunol. 2011, 24, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cull, V.S.; Bartlett, E.J.; James, C.M. Type I interferon gene therapy protects against cytomegalovirus-induced myocarditis. Immunology 2002, 106, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Härle, P.; Cull, V.; Agbaga, M.P.; Silverman, R.; Williams, B.R.; James, C.; Carr, D.J. Differential effect of murine alpha/beta interferon transgenes on antagonization of herpes simplex virus type 1 replication. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 6558–6567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Li, S.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, J.; Francois, S.; Lu, M.; Yang, D.; Dittmer, U.; Sutter, K. Different antiviral effects of IFNα subtypes in a mouse model of HBV infection. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Lai, F.; Wang, Y.; Sutter, K.; Dittmer, U.; Ye, J.; Zai, W.; Liu, M.; Shen, F.; et al. Functional Comparison of Interferon-α Subtypes Reveals Potent Hepatitis B Virus Suppression by a Concerted Action of Interferon-α and Interferon-γ Signaling. Hepatology 2021, 73, 486–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, Y.; Schwerdtfeger, M.; Westmeier, J.; Littwitz-Salomon, E.; Alt, M.; Brochhagen, L.; Krawczyk, A.; Sutter, K. Superior antiviral activity of IFNbeta in genital HSV-1 infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 949036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuhenn, J.; Meister, T.L.; Todt, D.; Bracht, T.; Schork, K.; Billaud, J.N.; Elsner, C.; Heinen, N.; Karakoese, Z.; Haid, S.; et al. Differential interferon-alpha subtype induced immune signatures are associated with suppression of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2111600119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heil, F.; Hemmi, H.; Hochrein, H.; Ampenberger, F.; Kirschning, C.; Akira, S.; Lipford, G.; Wagner, H.; Bauer, S. Species-specific recognition of single-stranded RNA via toll-like receptor 7 and 8. Science 2004, 303, 1526–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Wu, J.; Wu, Y.T.; Du, F.; Aroh, C.; Yan, N.; Sun, L.; Chen, Z.J. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is an innate immune sensor of HIV and other retroviruses. Science 2013, 341, 903–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gringhuis, S.I.; Hertoghs, N.; Kaptein, T.M.; Zijlstra-Willems, E.M.; Sarrami-Forooshani, R.; Sprokholt, J.K.; van Teijlingen, N.H.; Kootstra, N.A.; Booiman, T.; van Dort, K.A.; et al. HIV-1 blocks the signaling adaptor MAVS to evade antiviral host defense after sensing of abortive HIV-1 RNA by the host helicase DDX3. Nat. Immunol. 2017, 18, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solis, M.; Nakhaei, P.; Jalalirad, M.; Lacoste, J.; Douville, R.; Arguello, M.; Zhao, T.; Laughrea, M.; Wainberg, M.A.; Hiscott, J. RIG-I-mediated antiviral signaling is inhibited in HIV-1 infection by a protease-mediated sequestration of RIG-I. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 1224–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, T.; Sato, S.; Ishii, K.J.; Coban, C.; Hemmi, H.; Yamamoto, M.; Terai, K.; Matsuda, M.; Inoue, J.; Uematsu, S.; et al. Interferon-alpha induction through Toll-like receptors involves a direct interaction of IRF7 with MyD88 and TRAF6. Nat. Immunol. 2004, 5, 1061–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, K.; Yanai, H.; Mizutani, T.; Negishi, H.; Shimada, N.; Suzuki, N.; Ohba, Y.; Takaoka, A.; Yeh, W.C.; Taniguchi, T. Role of a transductional-transcriptional processor complex involving MyD88 and IRF-7 in Toll-like receptor signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 15416–15421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genin, P.; Vaccaro, A.; Civas, A. The role of differential expression of human interferon—A genes in antiviral immunity. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev. 2009, 20, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacey, A.R.; Norris, P.J.; Qin, L.; Haygreen, E.A.; Taylor, E.; Heitman, J.; Lebedeva, M.; DeCamp, A.; Li, D.; Grove, D.; et al. Induction of a striking systemic cytokine cascade prior to peak viremia in acute human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection, in contrast to more modest and delayed responses in acute hepatitis B and C virus infections. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 3719–3733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, C.; Taubert, D.; Jung, N.; Fatkenheuer, G.; van Lunzen, J.; Hartmann, P.; Romerio, F. Preferential upregulation of interferon-alpha subtype 2 expression in HIV-1 patients. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2009, 25, 577–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Sun, B.; Esser, S.; Jessen, H.; Streeck, H.; Widera, M.; Yang, R.; Dittmer, U.; Sutter, K. Expression Pattern of Individual IFNA Subtypes in Chronic HIV Infection. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2017, 37, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, M.S.; Guo, K.; Gibbert, K.; Lee, E.J.; Dillon, S.M.; Barrett, B.S.; McCarter, M.D.; Hasenkrug, K.J.; Dittmer, U.; Wilson, C.C.; et al. Interferon-α Subtypes in an Ex Vivo Model of Acute HIV-1 Infection: Expression, Potency and Effector Mechanisms. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1005254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, S.M.; Guo, K.; Austin, G.L.; Gianella, S.; Engen, P.A.; Mutlu, E.A.; Losurdo, J.; Swanson, G.; Chakradeo, P.; Keshavarzian, A.; et al. A compartmentalized type I interferon response in the gut during chronic HIV-1 infection is associated with immunopathogenesis. AIDS 2018, 32, 1599–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutrieux, J.; Fabre-Mersseman, V.; Charmeteau-De Muylder, B.; Rancez, M.; Ponte, R.; Rozlan, S.; Figueiredo-Morgado, S.; Bernard, A.; Beq, S.; Couedel-Courteille, A.; et al. Modified interferon-alpha subtypes production and chemokine networks in the thymus during acute simian immunodeficiency virus infection, impact on thymopoiesis. AIDS 2014, 28, 1101–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easlick, J.; Szubin, R.; Lantz, S.; Baumgarth, N.; Abel, K. The early interferon alpha subtype response in infant macaques infected orally with SIV. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2010, 55, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaritsky, L.A.; Dery, A.; Leong, W.Y.; Gama, L.; Clements, J.E. Tissue-specific interferon alpha subtype response to SIV infection in brain, spleen, and lung. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2013, 33, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodero, M.P.; Decalf, J.; Bondet, V.; Hunt, D.; Rice, G.I.; Werneke, S.; McGlasson, S.L.; Alyanakian, M.A.; Bader-Meunier, B.; Barnerias, C.; et al. Detection of interferon alpha protein reveals differential levels and cellular sources in disease. J. Exp. Med. 2017, 214, 1547–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaks, E.; Gavutis, M.; Uze, G.; Martal, J.; Piehler, J. Differential receptor subunit affinities of type I interferons govern differential signal activation. J. Mol. Biol. 2007, 366, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piehler, J.; Thomas, C.; Garcia, K.C.; Schreiber, G. Structural and dynamic determinants of type I interferon receptor assembly and their functional interpretation. Immunol. Rev. 2012, 250, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Weerd, N.A.; Vivian, J.P.; Nguyen, T.K.; Mangan, N.E.; Gould, J.A.; Braniff, S.J.; Zaker-Tabrizi, L.; Fung, K.Y.; Forster, S.C.; Beddoe, T.; et al. Structural basis of a unique interferon-β signaling axis mediated via the receptor IFNAR1. Nat. Immunol. 2013, 14, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, G.R.; Darnell, J.E., Jr. The JAK-STAT pathway at twenty. Immunity 2012, 36, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnell, J.E., Jr.; Kerr, I.M.; Stark, G.R. Jak-STAT pathways and transcriptional activation in response to IFNs and other extracellular signaling proteins. Science 1994, 264, 1415–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, T.; Goujon, C.; Malim, M.H. HIV-1 and interferons: Who’s interfering with whom? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suprunenko, T.; Hofer, M.J. The emerging role of interferon regulatory factor 9 in the antiviral host response and beyond. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev. 2016, 29, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leviyang, S. Interferon stimulated binding of ISRE is cell type specific and is predicted by homeostatic chromatin state. Cytokine X 2021, 3, 100056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, W.M.; Chevillotte, M.D.; Rice, C.M. Interferon-stimulated genes: A complex web of host defenses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 32, 513–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNab, F.; Mayer-Barber, K.; Sher, A.; Wack, A.; O’Garra, A. Type I interferons in infectious disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platanias, L.C. Mechanisms of type-I- and type-II-interferon-mediated signalling. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005, 5, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivashkiv, L.B.; Donlin, L.T. Regulation of type I interferon responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 14, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalska, A.; Blaszczyk, K.; Wesoly, J.; Bluyssen, H.A.R. A Positive Feedback Amplifier Circuit That Regulates Interferon (IFN)-Stimulated Gene Expression and Controls Type I and Type II IFN Responses. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavender, K.J.; Gibbert, K.; Peterson, K.E.; Van Dis, E.; Francois, S.; Woods, T.; Messer, R.J.; Gawanbacht, A.; Müller, J.A.; Münch, J.; et al. Interferon Alpha Subtype-Specific Suppression of HIV-1 Infection In Vivo. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 6001–6013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Shen, G.; Kibbie, J.; Gonzalez, T.; Dillon, S.M.; Smith, H.A.; Cooper, E.H.; Lavender, K.; Hasenkrug, K.J.; Sutter, K.; et al. Qualitative Differences Between the IFNα subtypes and IFNβ Influence Chronic Mucosal HIV-1 Pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervas-Stubbs, S.; Perez-Gracia, J.L.; Rouzaut, A.; Sanmamed, M.F.; Le Bon, A.; Melero, I. Direct effects of type I interferons on cells of the immune system. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 2619–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platanias, L.C. The p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway and its role in interferon signaling. Pharmacol. Ther. 2003, 98, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanifer, M.L.; Pervolaraki, K.; Boulant, S. Differential Regulation of Type I and Type III Interferon Signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.J.; Wang, W.; Wang, W.B.; Ren, H.; Qi, Z.T. Involvement of ERK pathway in interferon alpha-mediated antiviral activity against hepatitis C virus. Cytokine 2015, 72, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furler, R.L.; Uittenbogaart, C.H. Signaling through the P38 and ERK pathways: A common link between HIV replication and the immune response. Immunol. Res. 2010, 48, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Sluis, R.M.; Zerbato, J.M.; Rhodes, J.W.; Pascoe, R.D.; Solomon, A.; Kumar, N.A.; Dantanarayana, A.I.; Tennakoon, S.; Dufloo, J.; McMahon, J.; et al. Diverse effects of interferon alpha on the establishment and reversal of HIV latency. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardito, F.; Giuliani, M.; Perrone, D.; Troiano, G.; Lo Muzio, L. The crucial role of protein phosphorylation in cell signaling and its use as targeted therapy (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2017, 40, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, J. A review on recent trends in the phosphoproteomics workflow. From sample preparation to data analysis. Anal. Chim. Acta 2022, 1199, 338857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojcechowskyj, J.A.; Didigu, C.A.; Lee, J.Y.; Parrish, N.F.; Sinha, R.; Hahn, B.H.; Bushman, F.D.; Jensen, S.T.; Seeholzer, S.H.; Doms, R.W. Quantitative phosphoproteomics reveals extensive cellular reprogramming during HIV-1 entry. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 13, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakoese, Z.; Schwerdtfeger, M.; Karsten, C.B.; Esser, S.; Dittmer, U.; Sutter, K. Distinct Type I Interferon Subtypes Differentially Stimulate T Cell Responses in HIV-1-Infected Individuals. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 936918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickow, J.; Francois, S.; Kaiserling, R.L.; Malyshkina, A.; Drexler, I.; Westendorf, A.M.; Lang, K.S.; Santiago, M.L.; Dittmer, U.; Sutter, K. Diverse Immunomodulatory Effects of Individual IFNα Subtypes on Virus-Specific CD8+ T Cell Responses. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperber, S.J.; Gocke, D.J.; Haberzettl, C.; Kuk, R.; Schwartz, B.; Pestka, S. Anti-HIV-1 activity of recombinant and hybrid species of interferon-alpha. J. Interferon Res. 1992, 12, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katabira, E.T.; Sewankambo, N.K.; Mugerwa, R.D.; Belsey, E.M.; Mubiru, F.X.; Othieno, C.; Kataaha, P.; Karam, M.; Youle, M.; Perriens, J.H.; et al. Lack of efficacy of low dose oral interferon alfa in symptomatic HIV-1 infection: A randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Sex. Transm. Infect. 1998, 74, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alston, B.; Ellenberg, J.H.; Standiford, H.C.; Muth, K.; Martinez, A.; Greaves, W.; Kumi, J. A multicenter, randomized, controlled trial of three preparations of low-dose oral alpha-interferon in HIV-infected patients with CD4+ counts between 50 and 350 cells/mm(3). Division of AIDS Treatment Research Initiative (DATRI) 022 Study Group. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 1999, 22, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzoni, L.; Foulkes, A.S.; Papasavvas, E.; Mexas, A.M.; Lynn, K.M.; Mounzer, K.; Tebas, P.; Jacobson, J.M.; Frank, I.; Busch, M.P.; et al. Pegylated Interferon alfa-2a monotherapy results in suppression of HIV type 1 replication and decreased cell-associated HIV DNA integration. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 207, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmuth, D.M.; Murphy, R.L.; Rosenkranz, S.L.; Lertora, J.J.; Kottilil, S.; Cramer, Y.; Chan, E.S.; Schooley, R.T.; Rinaldo, C.R.; Thielman, N.; et al. Safety, tolerability, and mechanisms of antiretroviral activity of pegylated interferon Alfa-2a in HIV-1-monoinfected participants: A phase II clinical trial. J. Infect. Dis. 2010, 201, 1686–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauzin, A.; Espinosa Ortiz, A.; Blake, O.; Soundaramourty, C.; Joly-Beauparlant, C.; Nicolas, A.; Droit, A.; Dutrieux, J.; Estaquier, J.; Mammano, F. Differential Inhibition of HIV Replication by the 12 Interferon Alpha Subtypes. J. Virol. 2021, 95, e0231120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, N.; Schmeisser, H.; Dolan, M.A.; Bekisz, J.; Zoon, K.C.; Wahl, S.M. Structural variants of IFNalpha preferentially promote antiviral functions. Blood 2011, 118, 2567–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalie, E.; Jaitin, D.A.; Abramovich, R.; Schreiber, G. An interferon alpha2 mutant optimized by phage display for IFNAR1 binding confers specifically enhanced antitumor activities. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 11602–11611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.; Moraga, I.; Levin, D.; Krutzik, P.O.; Podoplelova, Y.; Trejo, A.; Lee, C.; Yarden, G.; Vleck, S.E.; Glenn, J.S.; et al. Structural linkage between ligand discrimination and receptor activation by type I interferons. Cell 2011, 146, 621–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwerdtfeger, M.; Dickow, J.; Schmitz, Y.; Francois, S.; Karakoese, Z.; Malyshkina, A.; Knuschke, T.; Dittmer, U.; Sutter, K. Immunotherapy With Interferon alpha11, But Not Interferon Beta, Controls Persistent Retroviral Infection. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 809774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, S.; Choi, J.G.; Ortega, N.M.; Zhang, J.; Shankar, P.; Swamy, N.M. Gene therapy with plasmids encoding IFN-beta or IFN-alpha14 confers long-term resistance to HIV-1 in humanized mice. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 78412–78420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutter, K.; Lavender, K.J.; Messer, R.J.; Widera, M.; Williams, K.; Race, B.; Hasenkrug, K.J.; Dittmer, U. Concurrent administration of IFNalpha14 and cART in TKO-BLT mice enhances suppression of HIV-1 viremia but does not eliminate the latent reservoir. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 18089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruenbach, M.; Muller, C.K.S.; Schlaepfer, E.; Baroncini, L.; Russenberger, D.; Kadzioch, N.P.; Escher, B.; Schlapschy, M.; Skerra, A.; Bredl, S.; et al. cART Restores Transient Responsiveness to IFN Type 1 in HIV-Infected Humanized Mice. J. Virol. 2022, 96, e0082722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, N.G.; Bosinger, S.E.; Estes, J.D.; Zhu, R.T.; Tharp, G.K.; Boritz, E.; Levin, D.; Wijeyesinghe, S.; Makamdop, K.N.; del Prete, G.Q.; et al. Type I interferon responses in rhesus macaques prevent SIV infection and slow disease progression. Nature 2014, 511, 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnathan, D.; Lawson, B.; Yu, J.; Patel, K.; Billingsley, J.M.; Tharp, G.K.; Delmas, O.M.; Dawoud, R.; Wilkinson, P.; Nicolette, C.; et al. Reduced Chronic Lymphocyte Activation following Interferon Alpha Blockade during the Acute Phase of Simian Immunodeficiency Virus Infection in Rhesus Macaques. J. Virol. 2018, 92, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanderford, T.H.; Slichter, C.; Rogers, K.A.; Lawson, B.O.; Obaede, R.; Else, J.; Villinger, F.; Bosinger, S.E.; Silvestri, G. Treatment of SIV-infected sooty mangabeys with a type-I IFN agonist results in decreased virus replication without inducing hyperimmune activation. Blood 2012, 119, 5750–5757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Ma, J.; Li, J.; Li, D.; Li, G.; Li, F.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, H.; Yasui, F.; Ye, C.; et al. Blocking type I interferon signaling enhances T cell recovery and reduces HIV-1 reservoirs. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, A.; Rezek, V.; Youn, C.; Lam, B.; Chang, N.; Rick, J.; Carrillo, M.; Martin, H.; Kasparian, S.; Syed, P.; et al. Targeting type I interferon-mediated activation restores immune function in chronic HIV infection. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nganou-Makamdop, K.; Billingsley, J.M.; Yaffe, Z.; O’Connor, G.; Tharp, G.K.; Ransier, A.; Laboune, F.; Matus-Nicodemos, R.; Lerner, A.; Gharu, L.; et al. Type I IFN signaling blockade by a PASylated antagonist during chronic SIV infection suppresses specific inflammatory pathways but does not alter T cell activation or virus replication. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1007246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teijaro, J.R.; Ng, C.; Lee, A.M.; Sullivan, B.M.; Sheehan, K.C.; Welch, M.; Schreiber, R.D.; de la Torre, J.C.; Oldstone, M.B. Persistent LCMV infection is controlled by blockade of type I interferon signaling. Science 2013, 340, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.B.; Yamada, D.H.; Elsaesser, H.; Herskovitz, J.; Deng, J.; Cheng, G.; Aronow, B.J.; Karp, C.L.; Brooks, D.G. Blockade of chronic type I interferon signaling to control persistent LCMV infection. Science 2013, 340, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.T.; Sullivan, B.M.; Teijaro, J.R.; Lee, A.M.; Welch, M.; Rice, S.; Sheehan, K.C.; Schreiber, R.D.; Oldstone, M.B. Blockade of interferon Beta, but not interferon alpha, signaling controls persistent viral infection. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 17, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swainson, L.A.; Sharma, A.A.; Ghneim, K.; Ribeiro, S.P.; Wilkinson, P.; Dunham, R.M.; Albright, R.G.; Wong, S.; Estes, J.D.; Piatak, M.; et al. IFN-alpha blockade during ART-treated SIV infection lowers tissue vDNA, rescues immune function, and improves overall health. JCI Insight 2022, 7, e153046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.X.; Fish, E.N. The yin and yang of viruses and interferons. Trends Immunol. 2012, 33, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crouse, J.; Kalinke, U.; Oxenius, A. Regulation of antiviral T cell responses by type I interferons. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuka, M.; De Giovanni, M.; Iannacone, M. The role of type I interferons in CD4+ T cell differentiation. Immunol. Lett. 2019, 215, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolumam, G.A.; Thomas, S.; Thompson, L.J.; Sprent, J.; Murali-Krishna, K. Type I interferons act directly on CD8 T cells to allow clonal expansion and memory formation in response to viral infection. J. Exp. Med. 2005, 202, 637–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cha, L.; Berry, C.M.; Nolan, D.; Castley, A.; Fernandez, S.; French, M.A. Interferon-alpha, immune activation and immune dysfunction in treated HIV infection. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 2014, 3, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquelin, B.; Petitjean, G.; Kunkel, D.; Liovat, A.S.; Jochems, S.P.; Rogers, K.A.; Ploquin, M.J.; Madec, Y.; Barre-Sinoussi, F.; Dereuddre-Bosquet, N.; et al. Innate immune responses and rapid control of inflammation in African green monkeys treated or not with interferon-alpha during primary SIVagm infection. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbeuval, J.P.; Boasso, A.; Grivel, J.C.; Hardy, A.W.; Anderson, S.A.; Dolan, M.J.; Chougnet, C.; Lifson, J.D.; Shearer, G.M. TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) in HIV-1-infected patients and its in vitro production by antigen-presenting cells. Blood 2005, 105, 2458–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraietta, J.A.; Mueller, Y.M.; Yang, G.; Boesteanu, A.C.; Gracias, D.T.; Do, D.H.; Hope, J.L.; Kathuria, N.; McGettigan, S.E.; Lewis, M.G.; et al. Type I interferon upregulates Bak and contributes to T cell loss during human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, S.; Tanaskovic, S.; Helbig, K.; Rajasuriar, R.; Kramski, M.; Murray, J.M.; Beard, M.; Purcell, D.; Lewin, S.R.; Price, P.; et al. CD4+ T-cell deficiency in HIV patients responding to antiretroviral therapy is associated with increased expression of interferon-stimulated genes in CD4+ T cells. J. Infect. Dis. 2011, 204, 1927–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosinger, S.E.; Utay, N.S. Type I interferon: Understanding its role in HIV pathogenesis and therapy. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2015, 12, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, Y.; Zhang, T.; Wang, R.; Zhang, H.; Huang, X.; Yin, J.; Zhang, L.; Xu, X.; Wu, H. Plasma IP-10 is associated with rapid disease progression in early HIV-1 infection. Viral Immunol. 2012, 25, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rout, S.S.; Di, Y.; Dittmer, U.; Sutter, K.; Lavender, K.J. Distinct effects of treatment with two different interferon-alpha subtypes on HIV-1-associated T-cell activation and dysfunction in humanized mice. AIDS 2022, 36, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichtfuss, G.F.; Meehan, A.C.; Cheng, W.J.; Cameron, P.U.; Lewin, S.R.; Crowe, S.M.; Jaworowski, A. HIV inhibits early signal transduction events triggered by CD16 cross-linking on NK cells, which are important for antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2011, 89, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, C.Y.; Chang, J.J.; Dantanarayana, A.I.; Solomon, A.; Evans, V.A.; Pascoe, R.; Gubser, C.; Trautman, L.; Fromentin, R.; Chomont, N.; et al. Combination Immune Checkpoint Blockade Enhances IL-2 and CD107a Production from HIV-Specific T Cells Ex Vivo in People Living with HIV on Antiretroviral Therapy. J. Immunol. 2022, 208, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).