Abstract

Urinary incontinence (UI) is a significant global health issue that impacts mainly middle-aged women, severely affecting their quality of life. Emerging research highlights the urinary microbiome’s complex role in the etiology and management of UI, with microbial dysbiosis potentially influencing symptom severity and treatment outcomes. This systematic review aimed to evaluate the current evidence on the urinary microbiome’s role in diagnosing and managing UI, focusing on variations in microbial composition across UI subtypes. We identified 21 studies, mostly employing 16S rRNA sequencing to characterize urinary microbiota and their associations with various UI subtypes, including urgency urinary incontinence (UUI), overactive bladder (OAB), and stress urinary incontinence (SUI). The findings revealed distinct microbial patterns, such as reduced Lactobacillus levels and increased Gardnerella prevalence, particularly in UUI. Altered microbiome profiles correlated with symptom severity, with reduced Lactobacilli suggesting a protective role in maintaining urinary health. Specific microbial species, including Actinotignum schaalii and Aerococcus urinae, emerged as potential biomarkers for UI diagnosis. Despite promising findings, limitations such as small sample sizes, variability in microbiome profiling methods, and insufficient causal evidence underscore the need for further research.

1. Introduction

Urinary incontinence (UI) is a prevalent and debilitating lower urinary tract condition that significantly impacts the quality of life of those affected. The prevalence of UI is approximately 45%, with prevalence increasing with age from 28% in women aged 30 to 39 years to 55% in women aged 80 to 90 years [1]. It is characterized by the involuntary loss of urine and encompasses symptoms such as frequent urination, urgency, and nocturia. Traditionally, the urinary tract was considered a sterile environment; however, recent studies have revealed a complex and dynamic microbial community within the urinary system [2]. This evolving understanding suggests that alterations in the urinary microbiome may contribute to the pathogenesis of various UI subtypes, including urgency urinary incontinence (UUI), overactive bladder (OAB), stress urinary incontinence (SUI), and mixed urinary incontinence (MUI), which are distinguished by their clinical characteristics [3]. SUI involves urine leakage triggered by physical exertion, such as coughing, sneezing, or exercising. UUI is defined by a sudden and intense urge to urinate, often leading to involuntary leakage before reaching the restroom. OAB, closely related to UUI, is characterized by urgency with or without leakage, often accompanied by frequency and nocturia [4].

MUI combines symptoms of SUI and UUI, presenting challenges for diagnosis and treatment due to its multifactorial nature. Other less common subtypes include functional incontinence, where physical or cognitive limitations prevent timely access to the restroom, and overflow incontinence, caused by incomplete bladder emptying [5].

Although age, menopause, body mass index (BMI), and parity are well-established risk factors for UI, the underlying pathophysiology remains poorly understood [6]. Emerging research suggests that the urinary microbiome may play a key role in these mechanisms. The microbiome’s interaction with the immune system is thought to influence symptom severity, providing a potential new method for diagnosis and treatment [7].

Advances in microbial detection techniques, such as 16S rRNA gene sequencing and expanded quantitative urine culture (EQUC), have challenged the traditional concept of sterile urine in healthy individuals, revealing a diverse microbial ecosystem within the urinary tract [8]. These technologies allow for the identification of bacteria and other microorganisms, including those that are not detectable by standard culture methods.

Maintaining a delicate microbial balance within the urinary tract is critical for urinary health. Disruptions to this balance, or dysbiosis, have been associated with various urinary conditions, including UUI and OAB [9]. The urinary microbiome includes diverse bacterial genera such as Lactobacillus, Corynebacterium, Streptococcus, Actinomyces, Staphylococcus, Gardnerella, and Bifidobacterium. A greater abundance of Lactobacillus is linked to a healthier urinary environment, while an overrepresentation of bacteria like Gardnerella and Prevotella is associated with UUI and other urinary symptoms [10]. This growing body of evidence underscores the importance of microbial homeostasis in maintaining urinary tract health and highlights dysbiosis as a potential contributor to UI pathogenesis.

The role of the urinary microbiome in diagnosing and managing UI is a growing area of research. Understanding how microbiome composition varies across UI subtypes, such as UUI, OAB, and SUI, could pave the way for innovative diagnostic tools and personalized treatment strategies. By identifying microbiome-based biomarkers, researchers hope to improve early detection and develop targeted therapies that restore microbial balance without relying on antibiotics [6].

This systematic review aimed to synthesize the existing evidence on the role of the urinary microbiome in diagnosing and managing urinary incontinence. Specifically, it explores microbiome differences across UI subtypes and their influence on management.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review adheres to the guidance of the Cochrane Collaboration and follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement. The research protocol was registered in PROSPERO with the assigned registration number CRD42025633823. Embase, Medline, PubMed, PsychInfo, and CINAHL were searched using their respective database search engines up to September 2024.

A comprehensive search was conducted to identify studies examining the relationship between urinary incontinence (UI) and the urinary microbiome. The search strategy utilized Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and keywords related to UI, bladder dysfunction, and the urinary microbiome. Terms such as urine incontinence, incontinence, overactive bladder, bladder disease, urinary dysfunction, and bladder dysfunction were used to capture all relevant studies on the relationship between the bladder microbiome and UI. To identify research focusing on the microbiome, terms including microbiome, biome, bacterial microbiome, bladder microbiota, and urinary tract microbiota were employed.

The search combined terms related to UI and the microbiome using the Boolean operator “AND.” Results were refined by applying filters to include only studies conducted on humans and published in English. Additionally, the inclusion criteria specified that the study population must consist of women aged 18 years and older. Manual searches were performed through the reference lists of included articles and relevant citations retrieved from the primary search results to complete the electronic search. Studies were included if they provided data on the relationship between bladder microbiota and UI. Exclusion criteria encompassed studies involving animals or children and research conducted primarily in laboratory settings, as well as non-English articles, reviews, editorials, surveys, poster presentations, and abstracts from major journals.

Two researchers independently screened the titles and abstracts of all retrieved studies to identify those eligible for inclusion for full-text screening and further data extraction. In cases of uncertainties or disagreements during this initial screening, a senior reviewer was consulted to resolve the issue and reach a final decision. Following this, data from each included study were systematically extracted and recorded in a predesigned data extraction spreadsheet. This spreadsheet captured key details, including the primary author, publication year, study design, age and presence of urinary incontinence, microbiome analysis techniques, and any reported associations between the bladder microbiome and urinary health outcomes.

The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed using the modified Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS). Each study was assigned a score ranging from 0 to 9, with higher scores indicating better methodological quality. The assessment focused on criteria such as sample representativeness, group comparability, and outcome measurement.

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics and Demographics

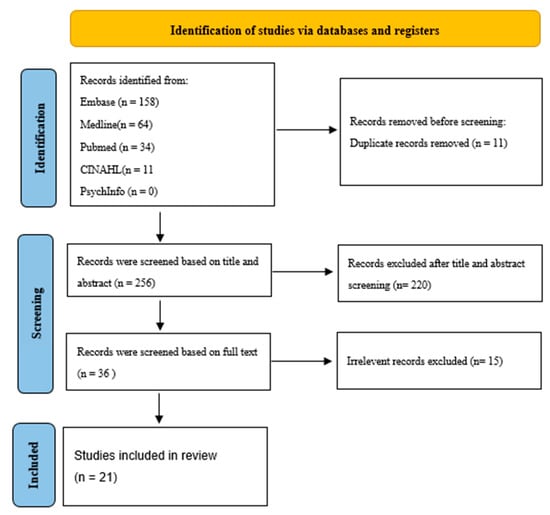

Using a comprehensive search strategy, a total of 256 studies were identified after duplicates were removed. Following the screening of titles and abstracts, excluding duplicates and non-human studies, 36 articles were selected for full-text review. Figure 1 shows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart, outlining the study selection process. Of the selected articles, 15 papers were excluded due to irrelevance or missing data, resulting in 21 studies being included in the final review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram [11] study selection process.

The final selection comprised studies published from 1947 to 30 December 2024, with participant sample sizes ranging from 9 to 1004, totaling 3125 participants across all studies. However, the earliest study meeting our inclusion criteria and included in the final analysis was published in 2015. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the included studies. The majority were cross-sectional (seven studies), followed by case–control studies (four studies); there were also three prospective cohort studies and three clinical trials, including a quasi-experimental trial. Participants primarily consisted of women aged 18 and older with urinary incontinence, with mean ages ranging from 37.1 years to 75 years.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the systematic review.

3.2. Microbiome Analysis and Incontinence Outcomes

Microbiome analysis methods varied across studies, most utilizing 16S rRNA gene sequencing to characterize bacterial communities. Diversity in microbiome composition was reported, with significant variations observed between participants with and without urinary incontinence. The studies reported a consistent association between the severity of the urinary microbiome and urinary incontinence. Specifically, several studies found that lower levels of Lactobacilli were correlated with increased symptom severity.

3.3. Impact of Microbiome on Incontinence Types

This review highlighted differences in microbiome profiles among various types of incontinence. One study showed that women with urinary incontinence demonstrated higher bacterial abundance and richness, with specific species such as Actinotignum schaalii and Aerococcus urinae more prevalent in UI cohorts. Microbial diversity, however, was not significantly different between UI patients and controls, suggesting that bacterial richness rather than diversity may be linked to symptom severity. For example, studies focusing on OAB and UUI indicated distinct bacterial compositions compared to controls. Common findings included a dominance of Lactobacillus spp. in most samples, with some studies identifying other bacterial species as potential contributors to symptom manifestation.

3.4. Methodological Quality

The methodological quality of the included scores ranged from 4 to 9. Most studies met the sample representativeness, comparability, and outcome assessment criteria. However, a few studies reported limitations, including potential biases in microbiome sample collection methods and small sample sizes.

4. Discussion

UI is a significant public health problem affecting millions of people worldwide. This study systematically reviewed the growing body of literature investigating the role of the urinary microbiome in the etiology and treatment of UI among adult women. We reviewed 22 studies that used 16S rRNA gene sequencing to comprehensively assess how microbiome profiling contributes to understanding UI pathophysiology. These studies have characterized the complex bacterial communities within the urinary tract, revealing complicated relationships between the composition of urinary microbiota and UI symptoms and extending the way to new diagnostic and therapeutic approaches.

One study showed significant differences in the urinary microbiome of patients with OAB with detrusor overactivity compared to OAB patients without detrusor overactivity and matched controls. Specifically, studies indicated that OAB patients with detrusor overactivity tend to have a less diverse microbiome and a higher proportion of Lactobacillus, particularly Lactobacillus iners [14]. These findings align with the broader understanding of microbial dysbiosis in OAB and suggest that the urinary microbiome may be involved in the pathogenesis of a specific phenotype of OAB.

The findings from the other included studies indicated an inverse correlation between Lactobacillus and the severity of urinary incontinence, suggesting a protective role of Lactobacilli in sustaining a healthy urinary tract [12,21,32]. Lactobacillus species, including L. iners, are known to help maintain a balanced microbial environment by preventing UTIs. The mechanism outcompetes pathogenic bacteria, such as Escherichia coli, for resources and adhesion sites on the urinary tract lining [31]. The underpresentation of Lactobacillus in OAB patients with detrusor overactivity may indicate an altered microbial balance that could contribute to the onset or exacerbation of OAB symptoms [31]. Therefore, understanding how microbial dysbiosis influences the severity of OAB symptoms may lead to new therapeutic strategies targeting the urinary microbiome. Additionally, the results from different studies revealed that bacterial richness might be more important than diversity in determining the severity of UI [20,32]. Actinotignum schaalii and Aerococcus urinae were two specific bacterial species that showed higher prevalence in patients with UI, indicating their potential as microbial biomarkers for diagnosing specific UI subtypes [23]. This finding could promote the development of more personalized diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for UI management.

This review showed that different treatment techniques are necessary for incontinence categories such as OAB and UU since they are associated with variations in microbiota profiles. These groups’ overrepresentation of specific bacterial species highlights the value of microbiome studies in creating and overseeing patient care programs. This fact introduces the prospect of employing treatments for individual patients. In other words, altering the urine microbiota would be a novel therapeutic approach, especially for individuals who do not react to conventional medications. The correlations between the urine microbiome and the severity suggest the opportunity for microbiome-targeted therapies. Interventions aimed at restoring healthy Lactobacillus levels or modulating specific pathogenic species could offer novel treatment avenues for UI. Therefore, microbiome profiling could be useful for determining who is more susceptible to UI or for developing individualized treatment plans.

It is important to note that current treatments for OAB remain limited to medications and behavioral interventions, particularly for patients with severe symptoms [19]. However, microbiome-targeted therapies could offer a novel avenue for those who do not respond well to traditional treatments. Given the variations in UI subtypes, microbiome profiling may help tailor treatment, including in patients who do not respond to conventional therapies.

The studies included in this review employed various methods for microbiome analysis, predominantly utilizing 16S rRNA gene sequencing. This approach provides a comprehensive characterization of bacterial communities and allows for the identification of specific taxa associated with UI. However, differences in sample collection methods, such as the use of catheterized versus midstream urine samples, may introduce variability in microbiome profiles and impact the comparability of results. On the other hand, despite the promising findings, several controversies and gaps remain in the current understanding of the urinary microbiome’s role in UI. For example, the complexity of polymicrobial interactions poses challenges for establishing definitive causal relationships between specific microbiome profiles and urinary disorders. Additionally, the influence of host factors, such as hormonal changes and age, further complicates these interactions, suggesting a need for continued research to unravel these dynamics [6].

When considering patients with positive urine cultures or analyses suggesting infection, it is important to distinguish whether the urinary microbiome changes are due to infection or an underlying cause of UI [33]. Pathogens like E. coli confound microbiome analysis, and their role in driving or merely coexisting with UI symptoms needs further clarification. Future research should aim to separate the effects of infection from dysbiosis to better understand the microbiome’s role in UI.

The modified NOS ranged from moderate to high quality for the included studies. Most studies adequately addressed sample representativeness, comparability, and outcome assessment. However, common limitations in included studies were small sample sizes and potential biases in microbiome sample collection, which may affect the generalizability of findings. Additionally, the variability in analytical techniques emphasizes the importance of adopting uniform methods to improve the reliability of results. Therefore, future studies should standardize sample collection protocols and include larger, more diverse populations to enhance the validity and reliability of results.

5. Conclusions

This review highlights the role of the urinary microbiome in UI. We found that Lactobacillus iners is more prevalent in OAB with detrusor overactivity, while reduced Lactobacillus levels correlate with greater UI severity. The presence of Actinotignum schaalii and Aerococcus urinae suggests potential microbial biomarkers for diagnosis. Considering the variation in microbiota compositions observed in different UI subtypes, microbiome profiling can optimize treatment selection, specifically for patients who do not respond to conventional therapies. However, inconsistencies in sample collection methods and analytical approaches currently hinder the reliability and applicability of existing findings. Future studies should standardize methodologies and include diverse populations to validate these approaches and enhance clinical applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.S. and M.A.S.; methodology, P.S.; screening, P.S. and Z.R.; data extraction, E.T., Z.R. and Z.S.; formal analysis and synthesis, P.S., Z.R., E.T., Z.S., S.N.G., B.B. and M.A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, P.S., S.N.G. and Z.R.; supervision, M.A.S. and B.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable for studies not involving humans or animals.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| ICIQ | International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire |

| LUTS | Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms |

| MESA | Medical, Epidemiologic, and Social Aspects of Aging |

| MUI | Mixed Urinary Incontinence |

| NOS | Newcastle–Ottawa Scale |

| OAB | Overactive Bladder |

| OAB DO | Overactive Bladder Detrusor Overactivity |

| OABQ | Overactive Bladder Questionnaire |

| OABSS | Overactive Bladder Symptom Score |

| OTU | Operational Taxonomic Unit |

| PFIQ | Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire |

| PGSC | Patient Global Symptom Control |

| PPIUS | Patient Perception of Intensity Urgency Scale |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analyses |

| SDI | Shannon Diversity Index |

| SUI | Stress Urinary Incontinence |

| UDI | Urogenital Distress Inventory |

| USS | Urgency Severity Scale |

| UUI | Urgency Urinary Incontinence |

| UDI | Urogenital Distress Inventory |

References

- Melville, J.L.; Katon, W.; Delaney, K.; Newton, K. Urinary incontinence in US women: A population-based study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2005, 165, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiteside, S.A.; Razvi, H.; Dave, S.; Reid, G.; Burton, J.P. The microbiome of the urinary tract—A role beyond infection. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2015, 12, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chorbińska, J.; Krajewski, W.; Nowak, Ł.; Małkiewicz, B.; Del Giudice, F.; Szydełko, T. Urinary Microbiome in Bladder Diseases-Review. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leslie, S.W.; Tran, L.N.; Puckett, Y. Urinary Incontinence. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559095/ (accessed on 11 August 2024).

- Dieter, A.A. Background, Etiology, and Subtypes of Urinary Incontinence. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 64, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govender, Y.; Gabriel, I.; Minassian, V.; Fichorova, R. The Current Evidence on the Association between the Urinary Microbiome and Urinary Incontinence in Women. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.W.; Lee, K.W.; Kim, Y.H. The microbiome’s function in disorders of the urinary bladder. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 1, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasiorek, M.; Hsieh, M.H.; Forster, C.S. Utility of DNA Next-Generation Sequencing and Expanded Quantitative Urine Culture in Diagnosis and Management of Chronic or Persistent Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2019, 58, e00204-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.S.; Lee, J.W. Urinary Tract Infection and Microbiome. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, M.M.; Hilt, E.E.; Rosenfeld, A.B.; Zilliox, M.J.; Thomas-White, K.; Fok, C.; Kliethermes, S.; Schreckenberger, P.C.; Brubaker, L.; Gai, X.; et al. The female urinary microbiome: A comparison of women with and without urgency urinary incontinence. mBio 2014, 5, e01283-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnes, M.U.; Siddiqui, N.Y.; Karstens, L.; Gantz, M.G.; Dinwiddie, D.L.; Sung, V.W.; Bradley, M.; Brubaker, L.; Ferrando, C.A.; Mazloomdoost, D.; et al. Urinary microbiome community types associated with urinary incontinence severity in women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 230, 344.e1–344.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabriel, I.; Delaney, M.L.; Au, M.; Courtepatte, A.; Bry, L.; Minassian, V.A. Impact of microbiota and host immunologic response on the efficacy of anticholinergic treatment for urgency urinary incontinence. Int. Urogynecology J. 2023, 34, 3041–3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javan Balegh Marand, A.; Baars, C.; Heesakkers, J.; van den Munckhof, E.; Ghojazadeh, M.; Rahnama’i, M.S.; Janssen, D. Differences in the Urinary Microbiome of Patients with Overactive Bladder Syndrome with and without Detrusor Overactivity on Urodynamic Measurements. Life 2023, 13, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joyce, C.; Halverson, T.; Gonzalez, C.; Brubaker, L.; Wolfe, A.J. The Urobiomes of Adult Women With Various Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Status Differ: A Re-Analysis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 860408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardos, R.; Leung, E.T.; Dahl, E.M.; Davin, S.; Asquith, M.; Gregory, W.T.; Karstens, L. Network-Based Differences in the Vaginal and Bladder Microbial Communities Between Women With and Without Urgency Urinary Incontinence. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 759156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, H.E.; Carnes, M.U.; Komesu, Y.M.; Lukacz, E.S.; Arya, L.; Bradley, M.; Rogers, R.G.; Sung, V.W.; Siddiqui, N.Y.; Carper, B.; et al. Association between the urogenital microbiome and surgical treatment response in women undergoing midurethral sling operation for mixed urinary incontinence. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 226, 93.e1–93.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Q.; Li, L.; Zhou, H.; Wu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wu, B.; Qiu, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Song, Q.; Zhao, J.; et al. The detection of urinary viruses is associated with aggravated symptoms and altered bacteriome in female with overactive bladder. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 984234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikata, R.; Yamaguchi, M.; Mase, Y.; Tatsuyuki, A.; Myint KZ, Y.; Ohta, H. Evaluation of the efficacy of Lactobacillus-containing feminine hygiene products on vaginal microbiome and genitourinary symptoms in pre- and postmenopausal women: A pilot randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Chen, C.; Zeng, J.; Wen, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhao, J.; Wu, P. Interplay between bladder microbiota and overactive bladder symptom severity: A cross-sectional study. BMC Urol. 2022, 22, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Li, K.; Sun, Q.; Xie, M.; Huang, P.; Yu, Y.; Wang, B.; Xue, J.; Zhu, Z.; et al. Unraveling the impact of Lactobacillus spp. and other urinary microorganisms on the efficacy of mirabegron in female patients with overactive bladder. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 1030315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komesu, Y.M.; Dinwiddie, D.L.; Richter, H.E.; Lukacz, E.S.; Sung, V.W.; Siddiqui, N.Y.; Zyczynski, H.M.; Ridgeway, B.; Rogers, R.G.; Arya, L.A.; et al. Defining the relationship between vaginal and urinary microbiomes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 222, 154.e1–154.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, T.K.; Lin, H.; Gao, X.; Thomas-White, K.J.; Hilt, E.E.; Mueller, E.R.; Wolfe, A.J.; Dong, Q.; Brubaker, L. Bladder bacterial diversity differs in continent and incontinent women: A cross-sectional study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 223, 729.e1–729.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas-White, K.; Taege, S.; Limeira, R.; Brincat, C.; Joyce, C.; Hilt, E.E.; Mac-Daniel, L.; Radek, K.A.; Brubaker, L.; Mueller, E.R.; et al. Vaginal estrogen therapy is associated with increased Lactobacillus in the urine of postmenopausal women with overactive bladder symptoms. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 223, 727.e1–727.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, K.; Kang, R.; Sathiananthamoorthy, S.; Khasriya, R.; Malone-Lee, J. A blinded observational cohort study of the microbiological ecology associated with pyuria and overactive bladder symptoms. Int. Urogynecology J. 2018, 29, 1493–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komesu, Y.M.; Richter, H.E.; Carper, B.; Dinwiddie, D.L.; Lukacz, E.S.; Siddiqui, N.Y.; Sung, V.W.; Zyczynski, H.M.; Ridgeway, B.; Rogers, R.G.; et al. The urinary microbiome in women with mixed urinary incontinence compared to similarly aged controls. Int. Urogynecology J. 2018, 29, 1785–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtiss, N.; Balachandran, A.; Krska, L.; Peppiatt-Wildman, C.; Wildman, S.; Duckett, J. A case controlled study examining the bladder microbiome in women with Overactive Bladder (OAB) and healthy controls. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2017, 214, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas-White, K.J.; Kliethermes, S.; Rickey, L.; Lukacz, E.S.; Richter, H.E.; Moalli, P.; Zimmern, P.; Norton, P.; Kusek, J.W.; Wolfe, A.J.; et al. Evaluation of the urinary microbiota of women with uncomplicated stress urinary incontinence. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 216, 55.e1–55.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, G.; Chen, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H. Urinary Microbiome and Psychological Factors in Women with Overactive Bladder. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karstens, L.; Asquith, M.; Davin, S.; Stauffer, P.; Fair, D.; Gregory, W.T.; Rosenbaum, J.T.; McWeeney, S.K.; Nardos, R. Does the Urinary Microbiome Play a Role in Urgency Urinary Incontinence and Its Severity? Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2016, 6, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas-White, K.J.; Hilt, E.E.; Fok, C.; Pearce, M.M.; Mueller, E.R.; Kliethermes, S.; Jacobs, K.; Zilliox, M.J.; Brincat, C.; Price, T.K.; et al. Incontinence Medication Response Relates to the Female Urinary Microbiota. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2016, 27, 723–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, M.M.; Zilliox, M.J.; Rosenfeld, A.B.; Thomas-White, K.J.; Richter, H.E.; Nager, C.W.; Visco, A.G.; Nygaard, I.E.; Barber, M.D.; Schaffer, J.; et al. The female urinary microbiome in urgency urinary incontinence. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 213, 347.e1–347.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willis-Gray, M.G.; Dieter, A.A.; Geller, E.J. Evaluation and management of overactive bladder: Strategies for optimizing care. Res. Rep. Urol. 2016, 8, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).