Abstract

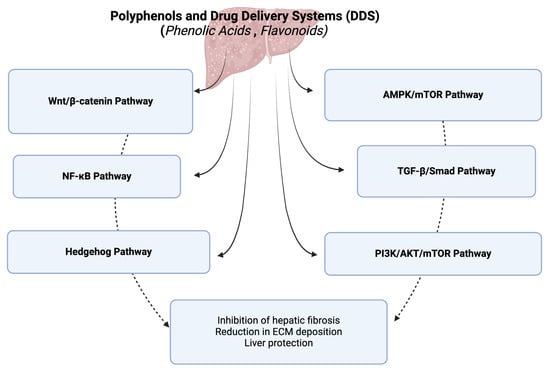

Chronic liver injuries often lead to hepatic fibrosis, a condition characterized by excessive extracellular matrix accumulation and abnormal connective tissue hyperplasia. Without effective treatment, hepatic fibrosis can progress to cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma. Current treatments, including liver transplantation, are limited by donor shortages and high costs. As such, there is an urgent need for effective therapeutic strategies. This review focuses on the potential of plant-based therapeutics, particularly polyphenols, phenolic acids, and flavonoids, in treating hepatic fibrosis. These compounds have demonstrated anti-fibrotic activities through various signaling pathways, including TGF-β/Smad, AMPK/mTOR, Wnt/β-catenin, NF-κB, PI3K/AKT/mTOR, and hedgehog pathways. Additionally, this review highlights the advancements in nanoparticulate drug delivery systems that enhance the pharmacokinetics, bioavailability, and therapeutic efficacy of these bioactive compounds. Methodologically, this review synthesizes findings from recent studies, providing a comprehensive analysis of the mechanisms and benefits of these plant-based treatments. The integration of novel drug delivery systems with plant-based therapeutics holds significant promise for developing effective treatments for hepatic fibrosis.

1. Introduction

Chronic liver injuries are a primary manifestation of hepatic fibrosis [1], which represents an abnormal wound healing response characterized by excessive extracellular matrix (ECM) accumulation and abnormal connective tissue hyperplasia [2]. Without effective treatment, hepatic fibrosis can advance to cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma [3]. Currently, liver transplantation is the most effective treatment for cirrhosis, but its clinical application is limited due to the shortage of donors and high costs [4]. There is no specific medication for treating hepatic fibrosis, and many hepatic anti-fibrotic drugs are still in the research and development phase [1]. Considering the severe consequences of hepatic fibrosis, understanding the underlying mechanisms leading to its development and progression is crucial. This understanding is essential for developing effective therapeutic strategies [2].

Polyphenols are increasingly gaining attention for the development of potential drugs for liver disease treatment. Numerous polyphenols have demonstrated hepatic anti-fibrotic activity by inhibiting the activity of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) [2]. These bioactive compounds operate through various pathways, including the TGF-β/Smad signaling pathways, AMPK/mTOR, Wnt/β-catenin, NF-κB, PI3K/AKT/mTOR, hedgehog pathways, and other factors associated with hepatic fibrosis.

Hepatic fibrosis can be mitigated using medicinal plants, plant extracts, and bioactive compounds derived from plants that inhibit the activation of hepatic stellate cells and reduce ECM deposition [5,6]. Plant extracts are a mixture of bioactive compounds and pharmacokinetic synergists [7]. These biologically active compounds can work synergistically to enhance the therapeutic efficacy of plant-based medicines [8]. Medicinal plants and their phytocompounds can protect the liver through various mechanisms, including the inhibition of fibrogenesis, oxidative stress, and tumor growth [9].

As most liver injuries are chronic conditions that require long-term treatment, it is important to minimize the side effects of hepatoprotective drugs. All bioactive compounds, including plant-based drugs, can have adverse effects. Therefore, further research on plant-based drugs with hepatic anti-fibrotic effects is necessary [10]. Despite significant progress in understanding the pathogenesis of hepatic fibrosis, no effective agent has been developed yet to prevent or directly reverse the fibrotic process [11]. The administered dose of biologically active compounds significantly influences the clinical response. Higher doses of such compounds have shown superior clinical efficacy but are associated with increased toxicity in various organs [12]. Many plant-based drugs and plant extracts have poor absorption and low bioavailability due to their poor lipid solubility or improper molecular sizes [13].

The aim of this review is to comprehensively analyze and synthesize current research on the anti-fibrotic effects of polyphenols, specifically phenolic acids and flavonoids, and to evaluate the advancements in nanoparticulate drug delivery systems that enhance the pharmacokinetics and therapeutic efficacy of these bioactive compounds. By exploring the molecular mechanisms through which polyphenols modulate key signaling pathways implicated in hepatic fibrosis, and by assessing the potential of novel delivery systems to improve their bioavailability and reduce side effects, this review seeks to provide a detailed understanding of the potential therapeutic applications in the treatment of hepatic fibrosis and to identify future research directions in this field.

2. Polyphenols and Hepatic Fibrosis

The intricate mechanisms driving hepatic fibrosis highlight the need for combined therapeutic approaches that target multiple signaling pathways. In addition to chemical compounds, various natural products have shown effectiveness in treating hepatic fibrosis [14]. Polyphenols, which are secondary metabolites naturally found in many plant-derived foods and beverages commonly consumed in the human diet, are particularly noteworthy. Based on their chemical structure, polyphenols are classified into several categories: phenolic acids (including hydroxycinnamic and hydroxybenzoic acids), flavonoids, stilbenes, tannins, and lignans [15,16,17,18,19].

2.1. Phenolic Acids

Phenolic acids are the simplest phenolic compounds, characterized by a single phenolic ring with multiple hydroxyl or methoxyl groups attached [20]. They are divided into two main categories: derivatives of hydroxycinnamic acid and derivatives of hydroxybenzoic acid [21].

Hydroxycinnamic acids are aromatic carboxylic acids with an unsaturated side chain [22]. In these acids, the carboxylic acid functional group is separated from the phenol ring by a double bond (C=C) [21]. Cinnamic acids function as phytohormones and are precursors to chalcones, flavonoids, anthocyanins, and stilbenes [22]. Hydroxycinnamic acids associated with hepatic fibrosis include chlorogenic acid, ferulic acid, isochlorogenic acid, p-coumaric acid, rosmarinic acid, salvianolic acids A and B, and sinapic acid (Table 1).

Hydroxybenzoic acids are phenols substituted with a carboxylic acid functional group directly bonded to the phenol ring [21]. These acids are less abundant in plants and are components of complex structures such as tannins and lignins [23]. This category includes p-hydroxybenzoic, protocatechuic, vanillic, syringic, and gallic acids [24]. Hydroxybenzoic acids with hepatic anti-fibrotic activity include gallic acid, protocatechuic acid, and vanillic acid (Table 1).

Table 1.

Pharmacological effects of phenolic acids in liver fibrosis.

Table 1.

Pharmacological effects of phenolic acids in liver fibrosis.

| Class of Phenolic Acids | Bioactive Compounds | Cell Lines/ Animal Model | Pharmacological Effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxycinnamic acids | Chlorogenic acid | LX-2 cells Sprague-Dawley rats |

| [25] |

| Sprague-Dawley rats |

| [26] | ||

| Ferulic acid | MPHs, RAW 264.7 cells, and LX-2 cells C57BL/6J mice |

| [27] | |

| Isochlorogenic acid B | C57BL/6 mice |

| [28] | |

| p-Coumaric acid | LX-2 cells C57BL/6 mice |

| [29] | |

| Rosmarinic acid | Sprague-Dawley rats HSC-T6 |

| [30] | |

| Salvianolic acid A | Sprague-Dawley rats |

| [31] | |

| Salvianolic acid B | C57BL/6 mice LO2 cells |

| [32] | |

| C57BL/6 mice LX2 and WRL68 cells |

| [33] | ||

| HSC-LX-2 cells BALB/c mice |

| [34] | ||

| JS1 and LX2 cells |

| [35] | ||

| Sprague-Dawley rats |

| [36] | ||

| LX-2 and T6 cells BALB/c mice |

| [37] | ||

| LX-2 cells |

| [38] | ||

| HSC-T6 and LX-2 cells |

| [39] | ||

| Sinapic acid | Sprague-Dawley rats |

| [40] | |

| Hydroxybenzoic acids | Gallic acid and dodecyl gallate | Wistar albino rats |

| [41] |

| Protocatechuic acid | HSC-T6 cells C57BL/6 mice |

| [42] | |

| Vanillic acid | Sprague-Dawley rats HSC-T6 cells |

| [43] |

Legend: ↑ increased/up-regulated; ↓ decreased/down-regulated; Akt, protein kinase B; ALB, albumin; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AMPK, adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; Atg5, autophagy-related gene 5; BAMBI, “bone morphogenetic protein” activin membrane-bound inhibitor; Bax, Bcl-2-associated X protein; Bcl-2, B-cell lymphoma-2; CAT, catalase; Ccl2, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2; CCl4, carbon tetrachloride; CIV, type IV collagen; Col-1, collagen 1; Col1α1, collagen type 1 alpha 1; Col1α2, collagen type 1 alpha 2; Col3α1, collagen type 3 alpha 1; Col4α1, collagen type 4 alpha 1; COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; CTGF, connective tissue growth factor; DMN, dimethylnitrosamine; Ecm1, extracellular matrix protein 1; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase; ERK1/2, extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2; FGF19, fibroblast growth factor; FGFR4, fibroblast growth factor receptor 4; GLB, globulin; Gli1, transcription factor glioma-associated oncogene homolog 1; GPx, glutathione peroxidase; GR, glutathione reductase; GSH, glutathione; GST, glutathione-S-transferase; HA, hyaluronic acid; HSCs, hepatic stellate cells; HYP, hydroxyproline; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; IL-6, interleukin-6; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; LC3B, microtubule-associated protein 2 light chain 3 type B; LN, laminin; LncRNA, long non-coding RNA; LOX, lysyloxidase; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; LX-2, human hepatic stellate cell line; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; MDA, malondialdehyde; MIF, macrophage migration inhibitory factor; MMP-9, matrix metalloproteinase 9; MPHs, mouse primary hepatocytes; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; MYD88, myeloid differentiation primary response 88; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa B; NLRP3, NLR family pyrin domain containing 3; NOX2, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase-2; Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; PAI, plasminogen activator inhibitor; p-Akt, phosphorylated protein kinase B; PCIII, procollagen type III; PDGFRβ, platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta; PDGF-βR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta; p-ERK, phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; PIIIP, procollagen III peptide; p-JNK, phosphorylated c-Jun N-terminal kinase; p-mTOR, phosphorylated mammalian target of rapamycin; p-Smad2, phosphorylated Smad2; P-Smad2/3L, phosphorylation of Smad2/3 at linker regions; P-Smad2C, phosphorylation of Smad2 at C-terminal linker regions; p-Smad3, phosphorylated Smad3; P-Smad3C, phosphorylation of Smad3 at C-terminal linker regions; Ptch1, membrane protein receptor protein patched homolog 1; PTP1B, protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B; ROR, regulator of reprogramming; ROS, reactive oxygen species; Shh, Sonic hedgehog protein; Smo, membrane protein receptor Smoothened; SOD, superoxide dismutase; TAA, thioacetamide; TBIL, total bilirubin; TGF-β1, transforming growth factor beta 1; TIMP-1, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 1; TLR4, toll-like receptor 4; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha; α-SMA, alpha smooth muscle actin; γ-GT, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase.

2.2. Flavonoids

Flavonoids are a class of plant pigments increasingly utilized in drug development and nutraceutical applications [44]. These natural phenolic compounds feature a phenyl benzo (γ) pyrone-derived structure, comprising two benzene rings (A and B) connected by a pyrane ring (C) [45].

The effectiveness of orally administered flavonoids is limited due to their low dissolution rate, partial degradation in the acidic gastric environment, reduced permeability, and extensive first-pass metabolism before reaching systemic circulation [46].

Flavonoids are categorized into different subclasses based on the specific carbon atom of ring C to which ring B is attached and the degree of unsaturation and oxidation of ring C. These subclasses include flavan-3-ols (also known as flavanols or catechins), flavonols, flavones, flavanones, isoflavones, anthocyanidins, and chalcones [47,48].

2.2.1. Flavanols

Flavanols (IUPAC name: 3-hydroxy-2-phenylchromen-4-one) are a subclass of flavonoids and serve as secondary metabolites in plants [49]. Their chemical structure includes a hydroxyl group (-OH) on the third carbon atom (C3) and a carbonyl group (C=O) on the fourth carbon atom of the central heterocyclic ring [50].

Table 2 summarizes the pharmacological effects of several flavanol compounds on liver fibrosis, highlighting their ability to reduce fibrosis, oxidative stress, inflammation, and hepatic stellate cell activation. Each compound—epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), dihydromyricetin, hesperetin and its derivatives, hesperidin, liquiritigenin, naringenin, and naringin—demonstrates protective effects against liver damage through various mechanisms, including the modulation of signaling pathways like TGF-β1/Smad, PI3K/Akt, and cGAS-STING, ultimately contributing to the attenuation of liver fibrosis and improvement in liver function.

Table 2.

Pharmacological effects of flavanols in liver fibrosis.

2.2.2. Flavonols

Flavonols are bioavailable compounds with multiple therapeutic benefits, such as hepatoprotective activity, free radical scavenging, cardioprotective, antiviral, antibacterial, and antineoplastic properties [73]. Flavonols contain a central structure of 3-hydroxyflavones, also known as 3-hydroxy-2-phenylchromen-4-one [74,75]. Flavonols are distinguished from other groups of flavonoids by the hydroxylation of one of the benzene rings. Each flavonol presents a distinct pattern of hydroxylation of the benzene ring [76,77]. The free forms of flavonols are called aglycones. The latter have a common structure of a 3-hydroxyflavone backbone and are distinguished by the position of the hydroxyl groups. The number of hydroxyl groups significantly contributes to the bioactivity of these compounds [78,79].

Table 3 summarizes the pharmacological effects of various flavonols in reducing liver fibrosis. These compounds—fisetin, galangin, isorhamnetin, kaempferol, dihydrokaempferol, morin, myricetin, myricitrin, and quercetin—work primarily by inhibiting key fibrotic pathways, including PI3K/Akt, Wnt/β-catenin, TGF-β1-Smad, and ERK1/2 signaling pathways, by reducing inflammation and oxidative stress, suppressing hepatic stellate cell activation, and enhancing antioxidant defenses.

Table 3.

Pharmacological effects of flavonols in liver fibrosis.

2.2.3. Flavones

Flavones constitute another subclass of flavonoids. Their core structure includes a double bond between the C2 and C3 positions and a ketone group at the C4 position on ring C. The molecular formula for flavones is in [20,105,106]. Typically, flavones have a hydroxyl group at the fifth position of ring A, with additional hydroxylation potentially occurring at other positions, such as the seventh position of ring A or the 3′ and 4′ positions of ring B [107].

Table 4 provides a detailed summary of the pharmacological effects of flavones in combating liver fibrosis. These flavones act by reducing oxidative stress, inflammation, and collagen deposition, primarily through the inhibition of key fibrogenic signaling pathways like TGF-β/Smad and PI3K/Akt (baicalein, chrysin, isovitexin). They also suppress the activation and proliferation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), promote apoptosis and autophagy, and restore the balance of extracellular matrix (ECM) components (diosmin, isoorientin, ligustroflavone, isovitexin). Additionally, some flavones enhance antioxidant defenses and modulate pathways such as Nrf2 (alpinetin), cGAS-STING (oroxylin A), and Hippo/YAP and autophagy pathways (nobiletin), repressing the miR-17-5p/Wnt/β-catenin signaling (diosmin), suppressing TGF-β1-induced Smad and AKT signaling (luteolin), inhibiting the TLR2/TLR4 pathway (luteoloside), blocking the p38 MAPK and PDGF-Rβ signaling pathways (tricin), and contributing to the attenuation of liver fibrosis and the restoration of normal liver structure and function in various cell and animal models.

Table 4.

Pharmacological effects of flavones in liver fibrosis.

2.2.4. Flavanones

Flavanones are a subclass of flavonoids characterized by their distinct chemical structure. They have a flavan nucleus with a saturated three-carbon chain and a hydroxyl group attached to the second carbon (C2). This structure differentiates them from other flavonoids, such as flavones and flavonols, which have a double bond between C2 and C3. Flavanones are commonly found in citrus fruits such as oranges, lemons, and grapefruits, and they contribute to the characteristic bitterness of these fruits. Examples of flavanones include naringenin, hesperetin, and eriodictyol.

Flavanones have been studied for their potential health benefits, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer properties. Their bioavailability and metabolism are subjects of ongoing research to better understand their therapeutic potential.

Table 5 highlights how flavanones mitigate liver fibrosis by inhibiting key fibrogenic pathways, via the SIRT1/TGF-β1/Smad3 signaling pathway, enhancing autophagy, and inhibiting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway (ampelopsin), by reversing activated HSCs to their quiescent state, modulating autophagy, and inhibiting the mTOR signaling pathway (naringin), or by reducing oxidative stress and inflammation, enhancing antioxidant defenses via the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway, and inhibiting HSC activation through the TGF-β/Smad and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways (pinocembrin), leading to reduced fibrosis and improved liver function.

Table 5.

Pharmacological effects exerted by flavonones in liver fibrosis.

2.2.5. Isoflavones

Isoflavones are a subclass of flavonoids, which are naturally occurring compounds found in plants. Unlike other flavonoids, isoflavones have a unique structural feature where the B ring is attached to the C3 position of the central C ring, rather than the C2 position. This structural variation imparts distinct biological activities to isoflavones.

Isoflavones are predominantly found in legumes, with soybeans being the most significant source. Some of the well-known isoflavones include genistein, daidzein, and glycitein.

Table 6 highlights how isoflavones mitigate liver fibrosis by reducing oxidative stress, inflammation, and collagen deposition, while inhibiting key fibrogenic pathways such as JAK2/STAT3, TGF-β/Smad, and ERK1/2 (calycosin, genistein, puerarin, glabridin, soy isoflavone, tectorigenin). These compounds also promote the balance of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and tissue inhibitors (TIMPs), enhance antioxidant defenses, and modulate HSC activation, contributing to the attenuation of fibrosis and improvement in liver function.

Table 6.

Pharmacological effects of isoflavones in liver fibrosis.

2.2.6. Anthocyanidins

Anthocyanidins are pigments responsible for the colors in plants, flowers, and fruits [48]. Anthocyanins from blueberries have been shown to regulate the epigenetic modifications of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), thereby intervening in the treatment of hepatic fibrosis [154,155,156].

Table 7 highlights how anthocyanidins reduce liver fibrosis by inhibiting key fibrotic processes such as HSC activation, inflammation, oxidative stress, and collagen deposition, while enhancing antioxidant defenses, promoting apoptosis, and modulating signaling pathways such as Nrf2 and TGF-β/Smad, contributing to improved liver function and reduced fibrosis.

Table 7.

Pharmacological effects of anthocyanidins in liver fibrosis.

2.2.7. Chalcones

Chalcones are a subclass of flavonoids characterized by their unique open-chain structure. Unlike other flavonoids that have a closed ring system, chalcones consist of two aromatic rings (A and B) joined by a three-carbon α,β-unsaturated carbonyl system.

Chalcones are found in various plant species and are known for their bright yellow pigments. They serve as precursors in the biosynthesis of other flavonoids and isoflavonoids through the chalcone isomerase-catalyzed cyclization.

Table 8 demonstrates that chalcones effectively combat liver fibrosis by targeting several critical mechanisms. These compounds inhibit the activation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), reduce oxidative stress, and suppress inflammatory responses. Additionally, chalcones promote apoptosis in fibrotic cells, decrease collagen deposition, and modulate key signaling pathways such as Nrf2/HO-1, NF-κB, and metabolic processes like glycolysis. Together, these actions lead to significant reductions in fibrosis and improvements in liver function across various experimental models.

Table 8.

Pharmacological effects of chalcones in liver fibrosis.

2.3. Stilbenes

Stilbenes are organic compounds characterized by a 1,2-diphenylethylene structure, commonly found in plants such as grapes, berries, and peanuts. Known for their potent antioxidant properties, these phytochemicals have been extensively researched for their potential health benefits. Resveratrol, a notable stilbene, offers liver protection against damage from chemicals, cholestasis, and alcohol; improves glucose metabolism and lipid profiles; and reduces liver fibrosis and steatosis [173]. It regulates fibrogenesis by reducing portal pressure, inhibiting hepatic stellate cell activation, and enhancing endothelial function, as well as modulating key signaling pathways like NF-κB and PI3K/Akt [174,175], and inducing autophagy via the microRNA-20a/PTEN/PI3K/AKT axis [176].

In liver fibrosis models, such as those induced by dimethylnitrosamine (DMN), resveratrol reduces inflammatory cell infiltration and fibrosis, lowering MDA levels, increasing GPx and SOD levels, and inhibiting inflammatory mediators like NO, TNF-α, and IL-1β [177,178,179]. Additionally, resveratrol alleviates mercury-induced liver fibrosis by activating the Sirt1/PGC-1α pathway and regulating the microbiota–gut–liver axis, enhancing the abundance of Bifidobacterium [180]. In obstructive jaundice, it protects liver function by modulating lipid metabolism, reducing oxidative stress, and down-regulating targets like mTOR and CYP enzymes [181]. Piceatannol, a resveratrol analog, effectively protects against CCl4-induced liver fibrosis in mice by improving liver function, reducing collagen deposition, and suppressing fibrosis markers via the TGF-β/Smad pathway. It also alleviates oxidative damage, highlighting its potential as a preventive agent for liver fibrosis [182].

Pterostilbene, found in grapes and berries, inhibits DMN-induced liver fibrosis in rats by improving liver function, reducing fibrotic changes, and decreasing hepatic stellate cell activation. It lowers serum ALT and AST levels, improves histopathology, and reduces fibrosis markers like α-SMA, TGF-β1, and MMP2, likely through the inhibition of the TGF-β1/Smad signaling pathway [183]. In another study, pterostilbene with a superior pharmacokinetic profile showed stronger anti-fibrotic effects than hydroxylated stilbenes in a CCl4-induced rat liver fibrosis model. It significantly reduced fibrosis markers and down-regulated key signaling pathways, demonstrating more potent protective activity.

Another stilbene, mulberroside A, reduces CCl4-induced liver fibrosis in mice by inhibiting the pro-inflammatory response and cytokine expression, providing significant liver protection without directly affecting hepatic stellate cell proliferation [184].

3. Polyphenol-Based Drug Delivery Systems and Hepatic Fibrosis

Nanoparticulate drug delivery systems significantly enhance the pharmacokinetics of drugs, including their absorption, metabolism, and excretion [185,186,187]. Compared to traditional formulations, nanoencapsulation offers several advantages, such as improved solubility and bioavailability, targeted drug delivery, consistent drug release, reduced dosage, and fewer side effects [188].

Nanoparticles (NPs) play a crucial role in improving the efficiency of co-delivery methods due to their ability to easily cross cell membranes because of their small size, enhance drug kinetics, and escape lysosomal degradation following endocytosis [189,190,191]. The main challenge of co-delivery systems is using carriers to simultaneously transport drugs with different properties [192]. Various modified carriers, such as liposomes, micelles, and polymeric NPs, have been employed to enhance the efficiency of co-delivery systems [193].

Polymeric nanoparticles, solid lipid nanoparticles, polymeric micelles, dendrimers, liposomes, nanocapsules, nanogels, nano-emulsions, and carbon nanotubes are examples of novel drug delivery systems (NDDSs). These systems, composed of biocompatible and biodegradable materials, offer numerous advantages over conventional dosage forms, such as controlled drug release, improved stability, and reduced adverse effects [194,195].

Nanocarriers ensure site-specific delivery of therapeutics, thereby improving bioavailability, stability, solubility, controlled release of active ingredients, and prolonged drug action [196,197]. Additionally, nanocarriers protect drugs from metabolic degradation [198]. Examples of nanocarriers include nanocapsules, nanospheres, nano-emulsions, and nano-sized vesicular carriers [196].

Polymeric NPs are effective carriers for the oral administration of flavonoids. They enhance physicochemical stability, increase solubilization and bioavailability by improving absorption at the enterocyte level, and maintain therapeutic levels in blood and plasma with a significant increase in mean residence time [199,200]. Polymeric NPs protect against degradation, provide controlled release of therapeutic agents, and enhance specific transport [201].

Poly(D,L-lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) is a biopolymer used in the preparation of NPs for various therapeutic applications. It protects compounds from degradation and offers sustained drug release [202,203]. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved PLGA due to its properties, including biocompatibility, biodistribution, and biodegradability [204,205]. PLGA has been used in numerous drug delivery systems, both targeted and non-targeted [206,207].

PLGA nanoparticles are taken up by endocytosis, releasing the drug in intracellular locations, thereby improving therapeutic action and reducing side effects [207,208]. The rapid absorption of PLGA nanoparticles by the reticuloendothelial system can be significantly reduced by modifying their surface with poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG). This modification extends the circulation time of nanosystems in the blood, allows targeting to tissues, and prevents opsonization [209,210]. These nanoparticles with hydrophilic surfaces have shown improved permeability, presumably due to the prolonged residence time of the carrier in the blood [211,212]. The surface modification of nanoparticles with polyethylene glycol (PEG) extends circulation time, reduces non-specific interactions, and favors accumulation in tumors due to increased permeability and retention [212,213].

Polycaprolactone (PCL), a biodegradable polymer, is suitable for controlled drug release due to its high permeability to many drugs and lack of toxicity [214]. PCL can also form blends with other polymers [215].

Table 9 highlights the effectiveness of polyphenol-based drug delivery systems in combating liver fibrosis by leveraging advanced formulations that enhance the bioavailability, targeting, and therapeutic efficacy of active compounds. These formulations, including nanoparticles, nanocomplexes, liposomes, and exosomes, significantly improve the delivery of polyphenols like galangin, quercetin, chrysin, luteolin, hesperidin, naringenin, silibinin, silymarin, and curcumin. The enhanced delivery systems allow these compounds to more effectively reduce oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrotic markers such as ALT, AST, TGF-β1, and collagen deposition. Additionally, these systems improve the modulation of key signaling pathways like TGF-β/Smad, NF-κB, and Nrf2, leading to a better preservation of liver architecture and function in various experimental models of liver fibrosis.

Table 9.

The main pharmacological effects exerted by polyphenol-based drug delivery systems in liver fibrosis.

4. Conclusions and Perspectives

The integration of plant-based therapeutics with advanced nanoparticulate drug delivery systems offers a promising approach to treating hepatic fibrosis. Polyphenols, phenolic acids, and flavonoids have shown significant potential in mitigating hepatic fibrosis by targeting multiple signaling pathways involved in the disease’s progression. These natural compounds exert anti-fibrotic effects through mechanisms such as the inhibition of hepatic stellate cell activation, reduction in extracellular matrix deposition, and modulation of inflammatory responses. Overall, the signaling pathways modulated by these natural compounds in the context of hepatic fibrosis, which lead to the inhibition of hepatic fibrosis, reduction in extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition, and overall liver protection, are the TGF-β/Smad pathway, AMPK/mTOR pathway, Wnt/β-catenin pathway, NF-κB pathway, PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, and hedgehog pathway (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A diagram of signaling pathways modulated by polyphenols and their drug delivery systems in hepatic fibrosis. This figure was created with BioRender.com.

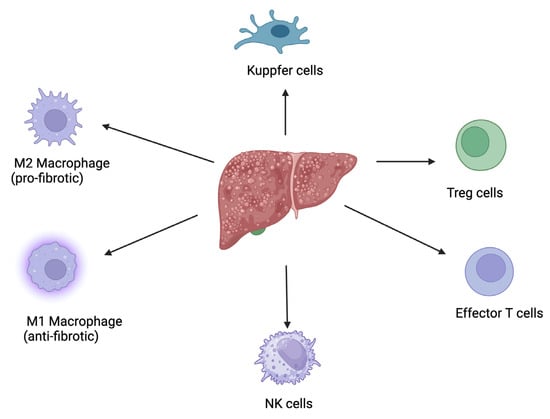

However, the modulation of immune cells and immune responses mediated by polyphenols (Figure 2) are key events in the resolution of liver fibrosis: (a). the modulation of macrophage polarization from the pro-fibrotic M2 phenotype to the anti-fibrotic M1 phenotype, which subsequently produces pro-inflammatory cytokines that help clear apoptotic cells and degrade the extracellular matrix; (b). inhibition of hepatic stellate cell activation, through reducing the secretion of pro-fibrotic cytokines like TGF-β from immune cells; (c). regulation of T-cell responses, particularly influencing the balance between regulatory T-cells (Tregs) and effector T-cells; (d). reduction in oxidative stress and inflammation, by scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS) and inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway, which are key contributors to liver fibrosis; (e). enhancement in autophagy in immune cells and hepatic stellate cells, a process that facilitates the clearance of damaged cells and reduces the deposition of extracellular matrix proteins; (f). modulation of the Kupffer cell activity, by reducing their pro-inflammatory cytokine production and promoting their role in clearing fibrotic tissue; (g). enhancing the cytotoxic activity of NK cells against activated hepatic stellate cells, leading to their apoptosis and reducing fibrogenesis.

Figure 2.

A diagram illustrating the role of immune cells and immune responses mediated by polyphenols in the resolution of liver fibrosis. This figure was created with BioRender.com.

Nanoparticulate drug delivery systems further enhance the therapeutic efficacy of these bioactive compounds by improving their solubility, bioavailability, and pharmacokinetics. Polymeric nanoparticles, solid lipid nanoparticles, polymeric micelles, and other novel drug delivery systems have demonstrated the ability to deliver therapeutic agents with high precision and reduced side effects.

Future research should focus on translating these findings into clinical applications. Rigorous clinical trials are needed to validate the safety and efficacy of plant-based therapeutics and nanoparticulate drug delivery systems in human subjects.

In conclusion, the convergence of plant-based therapeutics and innovative drug delivery systems represents a promising frontier in the fight against hepatic fibrosis. Continued research and development in this area hold the potential to significantly improve the management and treatment of this debilitating condition.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C. and A.H.; methodology, S.A.; investigation, A.C., F.F., S.D. and M.P.; resources, A.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C., F.F., A.H., S.A., S.D. and M.P.; writing—review and editing, A.C., A.H., S.A., S.D. and M.P.; supervision, F.F.; project administration, A.C.; funding acquisition, A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Romanian Ministry of Research and Innovation, PN-III-P1-1.1-PD-2021-0327 (PD 94/2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shan, L.; Wang, F.; Zhai, D.; Meng, X.; Liu, J.; Lv, X. New Drugs for Hepatic Fibrosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 874408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Huang, C.; Li, S.; Jiang, X.; Chang, H.; Li, M. Research Progress Regarding the Effect and Mechanism of Dietary Polyphenols in Liver Fibrosis. Molecules 2023, 29, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Z.; Sun, H.; Xue, T.; Gan, C.; Liu, H.; Xie, Y.; Yao, Y.; Ye, T. Liver Fibrosis: Therapeutic Targets and Advances in Drug Therapy. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 730176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altamirano-Barrera, A.; Barranco-Fragoso, B.; Méndez-Sánchez, N. Management Strategies for Liver Fibrosis. Ann. Hepatol. 2017, 16, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duval, F.; Moreno-Cuevas, J.E.; González-Garza, M.T.; Rodríguez-Montalvo, C.; Cruz-Vega, D.E. Protective Mechanisms of Medicinal Plants Targeting Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation and Extracellular Matrix Deposition in Liver Fibrosis. Chin. Med. 2014, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latief, U.; Ahmad, R. Herbal Remedies for Liver Fibrosis: A Review on the Mode of Action of Fifty Herbs. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2018, 8, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Luan, X.; Zheng, M.; Tian, X.-H.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, W.-D.; Ma, B.-L. Synergistic Mechanisms of Constituents in Herbal Extracts during Intestinal Absorption: Focus on Natural Occurring Nanoparticles. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermenean, A.; Smeu, C.; Gharbia, S.; Krizbai, I.A.; Ardelean, A. Plant-Derived Biomolecules and Drug Delivery Systems in the Treatment of Liver and Kidney Diseases. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2016, 22, 5415–5441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Prete, A.; Scalera, A.; Iadevaia, M.D.; Miranda, A.; Zulli, C.; Gaeta, L.; Tuccillo, C.; Federico, A.; Loguercio, C. Herbal Products: Benefits, Limits, and Applications in Chronic Liver Disease. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. ECAM 2012, 2012, 837939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Sharma, N.; Shukla, S.; Behl, T.; Gupta, S.; Anwer, M.K.; Vargas-De-La-Cruz, C.; Bungau, S.G.; Brisc, C. Understanding the Potential Role of Nanotechnology in Liver Fibrosis: A Paradigm in Therapeutics. Molecules 2023, 28, 2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Tantawy, W.H.; Temraz, A. Anti-Fibrotic Activity of Natural Products, Herbal Extracts and Nutritional Components for Prevention of Liver Fibrosis: Review. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 128, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaeiamiri, E.; Bahramsoltani, R.; Rahimi, R. Plant-Derived Natural Agents as Dietary Supplements for the Regulation of Glycosylated Hemoglobin: A Review of Clinical Trials. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesarwani, K.; Gupta, R. Bioavailability Enhancers of Herbal Origin: An Overview. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2013, 3, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, B. The Molecular Mechanisms of Liver Fibrosis and Its Potential Therapy in Application. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laddomada, B.; Blanco, A.; Mita, G.; D’Amico, L.; Singh, R.P.; Ammar, K.; Crossa, J.; Guzmán, C. Drought and Heat Stress Impacts on Phenolic Acids Accumulation in Durum Wheat Cultivars. Foods 2021, 10, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quideau, S.; Deffieux, D.; Douat-Casassus, C.; Pouységu, L. Plant Polyphenols: Chemical Properties, Biological Activities, and Synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2011, 50, 586–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarano, A.; Chieppa, M.; Santino, A. Plant Polyphenols-Biofortified Foods as a Novel Tool for the Prevention of Human Gut Diseases. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarano, A.; Chieppa, M.; Santino, A. Looking at Flavonoid Biodiversity in Horticultural Crops: A Colored Mine with Nutritional Benefits. Plants 2018, 7, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsao, R. Chemistry and Biochemistry of Dietary Polyphenols. Nutrients 2010, 2, 1231–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cháirez-Ramírez, M.H.; de la Cruz-López, K.G.; García-Carrancá, A. Polyphenols as Antitumor Agents Targeting Key Players in Cancer-Driving Signaling Pathways. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 710304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mamari, H. Phenolic Compounds: Classification, Chemistry, and Updated Techniques of Analysis and Synthesis. In Phenolic Compounds—Chemistry, Synthesis, Diversity, Non-Conventional Industrial, Pharmaceutical and Therapeutic Applications; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022; Volume 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Seedi, H.R.; El-Said, A.M.A.; Khalifa, S.A.M.; Göransson, U.; Bohlin, L.; Borg-Karlson, A.-K.; Verpoorte, R. Biosynthesis, Natural Sources, Dietary Intake, Pharmacokinetic Properties, and Biological Activities of Hydroxycinnamic Acids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 10877–10895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manach, C.; Scalbert, A.; Morand, C.; Rémésy, C.; Jiménez, L. Polyphenols: Food Sources and Bioavailability. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 79, 727–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, L.D.; Monteiro, M.C.; Teodoro, A.J. Anticancer Properties of Hydroxycinnamic Acids—A Review. Cancer Clin. Oncol. 2012, 1, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Luo, L.; Zhu, Z.-D.; Zhou, X.; Wang, Y.; Xue, J.; Zhang, J.; Cai, X.; Chen, Z.-L.; Ma, Q.; et al. Chlorogenic Acid Inhibits Liver Fibrosis by Blocking the miR-21-Regulated TGF-Β1/Smad7 Signaling Pathway in Vitro and in Vivo. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Dong, L.; Jiang, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, G.; Dang, X.; Lu, X.; Jia, M. Chlorogenic Acid Reduces Liver Inflammation and Fibrosis through Inhibition of Toll-like Receptor 4 Signaling Pathway. Toxicology 2013, 303, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Xue, X.; Fan, G.; Gu, Y.; Zhou, F.; Zheng, Q.; Liu, R.; Li, Y.; Ma, B.; Li, S.; et al. Ferulic Acid Ameliorates Hepatic Inflammation and Fibrotic Liver Injury by Inhibiting PTP1B Activity and Subsequent Promoting AMPK Phosphorylation. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 754976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Huang, K.; Niu, Z.; Mei, D.; Zhang, B. Protective Effect of Isochlorogenic Acid B on Liver Fibrosis in Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis of Mice. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2019, 124, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truong, T.M.T.; Seo, S.H.; Chung, S.; Kang, I. Attenuation of Hepatic Fibrosis by P-Coumaric Acid via Modulation of NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation in C57BL/6 Mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2023, 112, 109204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.-S.; Jiang, W.-L.; Tian, J.-W.; Qu, G.-W.; Zhu, H.-B.; Fu, F.-H. In Vitro and in Vivo Antifibrotic Effects of Rosmarinic Acid on Experimental Liver Fibrosis. Phytomedicine Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2010, 17, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Song, F.; Li, S.; Wu, B.; Gu, Y.; Yuan, Y. Salvianolic Acid A Attenuates CCl4-Induced Liver Fibrosis by Regulating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR, Bcl-2/Bax and Caspase-3/Cleaved Caspase-3 Signaling Pathways. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2019, 13, 1889–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Wang, L.; Fan, W.; Gao, S.; Zhang, D.; Ling, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, L.; Bai, F.; et al. Salvianolic Acid B Attenuates Liver Fibrosis by Targeting Ecm1 and Inhibiting Hepatocyte Ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 2024, 69, 103029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.-B.; Jiang, L.; Ni, J.-D.; Xu, Y.-H.; Liu, F.; Liu, W.-M.; Wang, S.-G.; Liu, Z.-Q.; Wang, C.-Y. Salvianolic Acid B Suppresses Hepatic Fibrosis by Inhibiting Ceramide Glucosyltransferase in Hepatic Stellate Cells. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2023, 44, 1191–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Li, S.; Chen, P.; Gu, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, C.; Wang, R.; Yuan, Y. Salvianolic Acid B Inhibits Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation and Liver Fibrosis by Targeting PDGFRβ. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 122, 110550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, N.; Zhang, J.; Ping, J.; Xu, L. Salvianolic Acid B Inhibits Autophagy and Activation of Hepatic Stellate Cells Induced by TGF-Β1 by Downregulating the MAPK Pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 938856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Duan, R.; Xu, T.; Hong, J.; Gu, W.; Lin, A.; Lian, L.; Huang, H.; Lu, J.; Li, T. Salvianolic Acid B Inhibits the Progression of Liver Fibrosis in Rats via Modulation of the Hedgehog Signaling Pathway. Exp. Ther. Med. 2022, 23, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Li, S.; Chen, P.; Yue, X.; Wang, S.; Gu, Y.; Yuan, Y. Salvianolic Acid B Suppresses Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation and Liver Fibrosis by Inhibiting the NF-κB Signaling Pathway via miR-6499-3p/LncRNA-ROR. Phytomedicine Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2022, 107, 154435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Chen, M.; Wang, B.; Han, Y.; Shang, H.; Chen, J. Salvianolic Acid B Blocks Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation via FGF19/FGFR4 Signaling. Ann. Hepatol. 2021, 20, 100259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Chen, W.; Ding, H.; Li, D.; Wen, G.; Zhang, C.; Lu, W.; Chen, M.; Yang, Y. Salvianolic Acid B Exerts Anti-Liver Fibrosis Effects via Inhibition of MAPK-Mediated Phospho-Smad2/3 at Linker Regions in Vivo and in Vitro. Life Sci. 2019, 239, 116881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.-S.; Kim, K.W.; Chung, H.Y.; Yoon, S.; Moon, J.-O. Effect of Sinapic Acid against Dimethylnitrosamine-Induced Hepatic Fibrosis in Rats. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2013, 36, 608–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perazzoli, M.R.A.; Perondi, C.K.; Baratto, C.M.; Winter, E.; Creczynski-Pasa, T.B.; Locatelli, C. Gallic Acid and Dodecyl Gallate Prevents Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Acute and Chronic Hepatotoxicity by Enhancing Hepatic Antioxidant Status and Increasing P53 Expression. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2017, 40, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, B.; Yang, Z.; Wang, S.; Guo, M.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Bi, X. The Protective Role of Protocatechuic Acid against Chemically Induced Liver Fibrosis in Vitro and in Vivo. Die Pharm. 2021, 76, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Tan, J.; Lv, X.; Zhang, J. Vanillic Acid Alleviates Liver Fibrosis through Inhibiting Autophagy in Hepatic Stellate Cells via the MIF/CD74 Signaling Pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 168, 115673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beecher, G.R. Overview of Dietary Flavonoids: Nomenclature, Occurrence and Intake. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 3248S–3254S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, N.C.; Samman, S. Flavonoids—Chemistry, Metabolism, Cardioprotective Effects, and Dietary Sources. J. Nutr. Biochem. 1996, 7, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnam, D.V.; Ankola, D.D.; Bhardwaj, V.; Sahana, D.K.; Kumar, M.N.V.R. Role of Antioxidants in Prophylaxis and Therapy: A Pharmaceutical Perspective. J. Control. Release Off. J. Control. Release Soc. 2006, 113, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, E.; Kandaswami, C.; Theoharides, T.C. The Effects of Plant Flavonoids on Mammalian Cells: Implications for Inflammation, Heart Disease, and Cancer. Pharmacol. Rev. 2000, 52, 673–751. [Google Scholar]

- Panche, A.N.; Diwan, A.D.; Chandra, S.R. Flavonoids: An Overview. J. Nutr. Sci. 2016, 5, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubina, R.; Krzykawski, K.; Kabała-Dzik, A.; Wojtyczka, R.D.; Chodurek, E.; Dziedzic, A. Fisetin, a Potent Anticancer Flavonol Exhibiting Cytotoxic Activity against Neoplastic Malignant Cells and Cancerous Conditions: A Scoping, Comprehensive Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, A.M.; Meier, G.P.; Haendiges, S.; Taylor, L.P. Structure-Activity Relationship Studies of Flavonol Analogues on Pollen Germination. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 2175–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.; Tsuchishima, M.; Tsutsumi, M. Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate Inhibits Osteopontin Expression and Prevents Experimentally Induced Hepatic Fibrosis. Biomed. Pharmacother. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 151, 113111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arffa, M.L.; Zapf, M.A.; Kothari, A.N.; Chang, V.; Gupta, G.N.; Ding, X.; Al-Gayyar, M.M.; Syn, W.; Elsherbiny, N.M.; Kuo, P.C.; et al. Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate Upregulates miR-221 to Inhibit Osteopontin-Dependent Hepatic Fibrosis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0167435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, H.; Cai, S.; Shao, R.; He, H. The Anti-Fibrotic Effects of Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate in Bile Duct-Ligated Cholestatic Rats and Human Hepatic Stellate LX-2 Cells Are Mediated by the PI3K/Akt/Smad Pathway. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2015, 36, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tipoe, G.L.; Leung, T.M.; Liong, E.C.; Lau, T.Y.H.; Fung, M.L.; Nanji, A.A. Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate (EGCG) Reduces Liver Inflammation, Oxidative Stress and Fibrosis in Carbon Tetrachloride (CCl4)-Induced Liver Injury in Mice. Toxicology 2010, 273, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasuda, Y.; Shimizu, M.; Sakai, H.; Iwasa, J.; Kubota, M.; Adachi, S.; Osawa, Y.; Tsurumi, H.; Hara, Y.; Moriwaki, H. (−)-Epigallocatechin Gallate Prevents Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Rat Hepatic Fibrosis by Inhibiting the Expression of the PDGFRbeta and IGF-1R. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2009, 182, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhen, M.-C.; Wang, Q.; Huang, X.-H.; Cao, L.-Q.; Chen, X.-L.; Sun, K.; Liu, Y.-J.; Li, W.; Zhang, L.-J. Green Tea Polyphenol Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate Inhibits Oxidative Damage and Preventive Effects on Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Hepatic Fibrosis. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2007, 18, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, X.; Ding, C.; Gu, Y.; Liu, W. Dihydromyricetin Reverses Thioacetamide-Induced Liver Fibrosis Through Inhibiting NF-κB-Mediated Inflammation and TGF-Β1-Regulated of PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 783886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Yu, L.; Zhou, M.; Hou, P.; Yi, L.; Mi, M. Dihydromyricetin Ameliorates Liver Fibrosis via Inhibition of Hepatic Stellate Cells by Inducing Autophagy and Natural Killer Cell-Mediated Killing Effect. Nutr. Metab. 2021, 18, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, R.; Wang, N.; Luo, H.; Lu, J. Hesperetin Mitigates Bile Duct Ligation-Induced Liver Fibrosis by Inhibiting Extracellular Matrix and Cell Apoptosis via the TGF-Β1/Smad Pathway. Curr. Mol. Med. 2018, 18, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, X.-F.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, S.; Li, H.-D.; Chen, S.-Y.; Wang, J.-N.; Pan, X.-Y.; Bu, F.-T.; Huang, C.; et al. Hesperetin Derivative Attenuates CCl4-Induced Hepatic Fibrosis and Inflammation by Gli-1-Dependent Mechanisms. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 76, 105838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Chen, X.; Chen, S.-Y.; Wang, A.; Wu, S.; Wu, Y.-Y.; Cheng, M.; Xu, J.-J.; Li, X.-F.; Huang, C.; et al. Hesperetin Derivative Decreases CCl4 -Induced Hepatic Fibrosis by Ptch1-Dependent Mechanisms. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2022, 36, e23149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Kong, L.-N.; Huang, C.; Ma, T.-T.; Meng, X.-M.; He, Y.; Wang, Q.-Q.; Li, J. Hesperetin Derivative-7 Inhibits PDGF-BB-Induced Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation and Proliferation by Targeting Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2015, 25, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.-X.; Chen, X.; Yang, Y.; Huang, H.-M.; Li, H.; Huang, C.; Meng, X.-M.; Li, J. Hesperitin Derivative-11 Suppress Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation and Proliferation by Targeting PTEN/AKT Pathway. Toxicology 2017, 381, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.-J.; Jiang, H.-C.; Wang, A.; Bu, F.-T.; Jia, P.-C.; Zhu, S.; Zhu, L.; Huang, C.; Li, J. Hesperetin Derivative-16 Attenuates CCl4-Induced Inflammation and Liver Fibrosis by Activating AMPK/SIRT3 Pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 915, 174530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasehi, Z.; Kheiripour, N.; Taheri, M.A.; Ardjmand, A.; Jozi, F.; Shahaboddin, M.E. Efficiency of Hesperidin against Liver Fibrosis Induced by Bile Duct Ligation in Rats. BioMed Res. Int. 2023, 2023, 5444301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Vargas, J.E.; Zarco, N.; Shibayama, M.; Segovia, J.; Tsutsumi, V.; Muriel, P. Hesperidin Prevents Liver Fibrosis in Rats by Decreasing the Expression of Nuclear Factor-κB, Transforming Growth Factor-β and Connective Tissue Growth Factor. Pharmacology 2014, 94, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, W.; Zhou, G.; Zhao, B.; Xiao, Q.; Li, C.; Fan, S.; Dong, P.; Zheng, J. Liquiritigenin Suppresses the Activation of Hepatic Stellate Cells via Targeting miR-181b/PTEN Axis. Phytomedicine Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2019, 66, 153108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.H.; Park, K.-I.; Kim, K.-Y.; Lee, J.-H.; Jang, E.J.; Ku, S.K.; Kim, S.C.; Suk, H.Y.; Park, J.Y.; Baek, S.Y.; et al. Liquiritigenin Inhibits Hepatic Fibrogenesis and TGF-Β1/Smad with Hippo/YAP Signal. Phytomed. Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2019, 62, 152780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xia, S.; Wang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, F.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Kong, D.; Zhang, Z.; Shao, J.; et al. Naringenin Is a Potential Immunomodulator for Inhibiting Liver Fibrosis by Inhibiting the cGAS-STING Pathway. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2023, 11, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Aquino, E.; Quezada-Ramírez, M.A.; Silva-Olivares, A.; Casas-Grajales, S.; Ramos-Tovar, E.; Flores-Beltrán, R.E.; Segovia, J.; Shibayama, M.; Muriel, P. Naringenin Attenuates the Progression of Liver Fibrosis via Inactivation of Hepatic Stellate Cells and Profibrogenic Pathways. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 865, 172730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Aquino, E.; Zarco, N.; Casas-Grajales, S.; Ramos-Tovar, E.; Flores-Beltrán, R.E.; Arauz, J.; Shibayama, M.; Favari, L.; Tsutsumi, V.; Segovia, J.; et al. Naringenin Prevents Experimental Liver Fibrosis by Blocking TGFβ-Smad3 and JNK-Smad3 Pathways. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 4354–4368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mihi, K.A.; Kenawy, H.I.; El-Karef, A.; Elsherbiny, N.M.; Eissa, L.A. Naringin Attenuates Thioacetamide-Induced Liver Fibrosis in Rats through Modulation of the PI3K/Akt Pathway. Life Sci. 2017, 187, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajender; Mazumder, A.; Sharma, A.; Azad, M.A.K. A Comprehensive Review of the Pharmacological Importance of Dietary Flavonoids as Hepatoprotective Agents. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. ECAM 2023, 2023, 4139117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnuolo, C.; Moccia, S.; Russo, G.L. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Flavonoids in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 153, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M.S.; Almezgagi, M.; Zhang, Y.; Bashir, A.; Abdullah, H.M.; Gamah, M.; Wang, X.; Zhu, Q.; Shen, X.; Ma, Q.; et al. Mechanistic New Insights of Flavonols on Neurodegenerative Diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 137, 111253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daryanavard, H.; Postiglione, A.E.; Mühlemann, J.K.; Muday, G.K. Flavonols Modulate Plant Development, Signaling, and Stress Responses. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2023, 72, 102350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcone Ferreyra, M.L.; Rius, S.P.; Casati, P. Flavonoids: Biosynthesis, Biological Functions, and Biotechnological Applications. Front. Plant Sci. 2012, 3, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popiolek-Kalisz, J.; Fornal, E. The Impact of Flavonols on Cardiovascular Risk. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Sharma, P.; Singh Tuli, H.; Sharma, A.K. Phytochemical and Pharmacological Properties of Flavonols. In eLS; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–12. ISBN 978-0-470-01590-2. [Google Scholar]

- El-Fadaly, A.A.; Afifi, N.A.; El-Eraky, W.; Salama, A.; Abdelhameed, M.F.; El-Rahman, S.S.A.; Ramadan, A. Fisetin Alleviates Thioacetamide-Induced Hepatic Fibrosis in Rats by Inhibiting Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2022, 44, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, Y.; Lu, H.; Xu, H. Galangin Reverses Hepatic Fibrosis by Inducing HSCs Apoptosis via the PI3K/Akt, Bax/Bcl-2, and Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway in LX-2 Cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2020, 43, 1634–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Gong, G.; Yang, W.; Li, Y.; Jiang, M.; Li, L. Antifibrotic Activity of Galangin, a Novel Function Evaluated in Animal Liver Fibrosis Model. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2013, 36, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidi, M.; Matour, E.; Beheshti Nasab, H.; Cheraghzadeh, M.; Shakerian, E. Isorhamnetin Exerts Antifibrotic Effects by Attenuating Platelet-Derived Growth Factor-BB-Induced HSC-T6 Cells Activation via Suppressing PI3K-AKT Signaling Pathway. Iran. Biomed. J. 2023, 27, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.; Feng, J.; Lu, X.; Yao, Z.; Liu, Q.; Lv, Y.; Han, Y.; Deng, J.; Zhou, Y. Isorhamnetin Inhibits Liver Fibrosis by Reducing Autophagy and Inhibiting Extracellular Matrix Formation via the TGF-Β1/Smad3 and TGF-Β1/P38 MAPK Pathways. Mediat. Inflamm. 2019, 2019, 6175091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.H.; Kim, S.C.; Kim, K.M.; Jang, C.H.; Cho, S.S.; Kim, S.J.; Ku, S.K.; Cho, I.J.; Ki, S.H. Isorhamnetin Attenuates Liver Fibrosis by Inhibiting TGF-β/Smad Signaling and Relieving Oxidative Stress. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 783, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, R.; Cao, C.; Hu, X.; Du, K.; Zhang, J.; Li, M.; Li, B.; Lin, H.; Zhang, A.; Li, Y.; et al. Kaempferol Attenuates Carbon Tetrachloride (CCl4)-Induced Hepatic Fibrosis by Promoting ASIC1a Degradation and Suppression of the ASIC1a-Mediated ERS. Phytomed. Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2023, 121, 155125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Li, C.; Zhang, R.; Zhan, Y.; Lin, L.; Lang, Z.; Tao, Q.; Zheng, J. Kaempferol Inhibits Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation by Regulating miR-26b-5p/Jag1 Axis and Notch Pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 881855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Huang, S.; Huang, Q.; Ming, Z.; Wang, M.; Li, R.; Zhao, Y. Kaempferol Attenuates Liver Fibrosis by Inhibiting Activin Receptor-like Kinase 5. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 6403–6410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Wei, S.; Wu, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, B.; Huang, D.; Dong, W. Dihydrokaempferol Attenuates CCl4-Induced Hepatic Fibrosis by Inhibiting PARP-1 to Affect Multiple Downstream Pathways and Cytokines. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2023, 464, 116438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perumal, N.; Perumal, M.; Halagowder, D.; Sivasithamparam, N. Morin Attenuates Diethylnitrosamine-Induced Rat Liver Fibrosis and Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation by Co-Ordinated Regulation of Hippo/Yap and TGF-Β1/Smad Signaling. Biochimie 2017, 140, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, L.; Wang, X.-M.; Xu, D.-Y.; Sang, L.-X.; Han, Y.; Jiang, L.-Y. Morin Enhances Hepatic Nrf2 Expression in a Liver Fibrosis Rat Model. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 8334–8344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Ahmad, S.; Najar, A. Morin, a Plant Derived Flavonoid, Modulates the Expression of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-γ Coactivator-1α Mediated by AMPK Pathway in Hepatic Stellate Cells. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2017, 9, 5662–5670. [Google Scholar]

- MadanKumar, P.; NaveenKumar, P.; Devaraj, H.; NiranjaliDevaraj, S. Morin, a Dietary Flavonoid, Exhibits Anti-Fibrotic Effect and Induces Apoptosis of Activated Hepatic Stellate Cells by Suppressing Canonical NF-κB Signaling. Biochimie 2015, 110, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heeba, G.H.; Mahmoud, M.E. Therapeutic Potential of Morin against Liver Fibrosis in Rats: Modulation of Oxidative Stress, Cytokine Production and Nuclear Factor Kappa B. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2014, 37, 662–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MadanKumar, P.; NaveenKumar, P.; Manikandan, S.; Devaraj, H.; NiranjaliDevaraj, S. Morin Ameliorates Chemically Induced Liver Fibrosis in Vivo and Inhibits Stellate Cell Proliferation in Vitro by Suppressing Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2014, 277, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.-S.; Jung, K.H.; Park, I.-S.; Kwon, S.W.; Lee, D.-H.; Hong, S.-S. Protective Effect of Morin on Dimethylnitrosamine-Induced Hepatic Fibrosis in Rats. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2009, 54, 782–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, Y.; Sun, Q.; Li, W.; Lu, Z.-M.; Xu, H.-Y.; Shi, J.-S.; Xu, Z.-H. The Common Dietary Flavonoid Myricetin Attenuates Liver Fibrosis in Carbon Tetrachloride Treated Mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1600392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domitrović, R.; Rashed, K.; Cvijanović, O.; Vladimir-Knežević, S.; Škoda, M.; Višnić, A. Myricitrin Exhibits Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory and Antifibrotic Activity in Carbon Tetrachloride-Intoxicated Mice. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2015, 230, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, Y.A.; Hassan, H.M.; El-Gayar, A.M.; Abdel-Rahman, N. Combined Quercetin and Simvastatin Attenuate Hepatic Fibrosis in Rats by Modulating SphK1/NLRP3 Pathways. Life Sci. 2024, 337, 122349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, A.; Sheikh, N.; Shahzad, M.; Saeed, G.; Fatima, N.; Akhtar, T. Quercetin Ameliorates Thioacetamide-Induced Hepatic Fibrosis and Oxidative Stress by Antagonizing the Hedgehog Signaling Pathway. J. Cell. Biochem. 2022, 123, 1356–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jin, Q.; Yao, Q.; Xu, B.; Li, L.; Zhang, S.; Tu, C. The Flavonoid Quercetin Ameliorates Liver Inflammation and Fibrosis by Regulating Hepatic Macrophages Activation and Polarization in Mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhang, Q.; Mo, W.; Feng, J.; Li, S.; Li, J.; Liu, T.; Xu, S.; Wang, W.; Lu, X.; et al. Quercetin Prevents Hepatic Fibrosis by Inhibiting Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation and Reducing Autophagy via the TGF-Β1/Smads and PI3K/Akt Pathways. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jin, Q.; Yao, Q.; Xu, B.; Li, Z.; Tu, C. Quercetin Attenuates the Activation of Hepatic Stellate Cells and Liver Fibrosis in Mice through Modulation of HMGB1-TLR2/4-NF-κB Signaling Pathways. Toxicol. Lett. 2016, 261, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Ortega, L.D.; Alcántar-Díaz, B.E.; Ruiz-Corro, L.A.; Sandoval-Rodriguez, A.; Bueno-Topete, M.; Armendariz-Borunda, J.; Salazar-Montes, A.M. Quercetin Improves Hepatic Fibrosis Reducing Hepatic Stellate Cells and Regulating Pro-Fibrogenic/Anti-Fibrogenic Molecules Balance. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 27, 1865–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gürler, S.; Kiraz, Y.; Baran, Y. Chapter 21. Flavonoids in Cancer Therapy: Current and Future Trends. In Biodiversity and Biomedicine; Ozturk, M., Egamberdieva, D., Pešić, M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 403–440. [Google Scholar]

- Hostetler, G.L.; Ralston, R.A.; Schwartz, S.J. Flavones: Food Sources, Bioavailability, Metabolism, and Bioactivity. Adv. Nutr. Bethesda Md 2017, 8, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hano, C.; Tungmunnithum, D. Plant Polyphenols, More than Just Simple Natural Antioxidants: Oxidative Stress, Aging and Age-Related Diseases. Medicines 2020, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Hu, R.; Li, J.; Xing, X.; Chen, J.; Zhou, Q.; Sun, J. Alpinetin Exerts Anti-Inflammatory, Anti-Oxidative and Anti-Angiogenic Effects through Activating the Nrf2 Pathway and Inhibiting NLRP3 Pathway in Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Liver Fibrosis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 96, 107660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melaibari, M.; Alkreathy, H.M.; Esmat, A.; Rajeh, N.A.; Shaik, R.A.; Alghamdi, A.A.; Ahmad, A. Anti-Fibrotic Efficacy of Apigenin in a Mice Model of Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Hepatic Fibrosis by Modulation of Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Fibrogenesis: A Preclinical Study. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Yu, Q.; Dai, W.; Wu, L.; Feng, J.; Zheng, Y.; Li, Y.; Guo, C. Apigenin Alleviates Liver Fibrosis by Inhibiting Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation and Autophagy via TGF-Β1/Smad3 and P38/PPARα Pathways. PPAR Res. 2021, 2021, 6651839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, M.; Yang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, J. Transcriptomics and Proteomics Analysis of System-Level Mechanisms in the Liver of Apigenin-Treated Fibrotic Rats. Life Sci. 2020, 248, 117475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhi, F.; Lun, W.; Deng, Q.; Zhang, W. Baicalin Inhibits PDGF-BB-Induced Hepatic Stellate Cell Proliferation, Apoptosis, Invasion, Migration and Activation via the miR-3595/ACSL4 Axis. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 41, 1992–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, H.; Han, H.; Hong, D.; Ren, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, C. Protective Effects of Baicalin on Carbon Tetrachloride Induced Liver Injury by Activating PPARγ and Inhibiting TGFβ1. Pharm. Biol. 2011, 49, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Che, Q.-M.; Zhao, X.; Pu, X.-P. Antifibrotic Effects of Chronic Baicalein Administration in a CCl4 Liver Fibrosis Model in Rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 631, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balta, C.; Ciceu, A.; Herman, H.; Rosu, M.; Boldura, O.M.; Hermenean, A. Dose-Dependent Antifibrotic Effect of Chrysin on Regression of Liver Fibrosis: The Role in Extracellular Matrix Remodeling. Dose-Response Publ. Int. Hormesis Soc. 2018, 16, 1559325818789835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balta, C.; Herman, H.; Boldura, O.M.; Gasca, I.; Rosu, M.; Ardelean, A.; Hermenean, A. Chrysin Attenuates Liver Fibrosis and Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation through TGF-β/Smad Signaling Pathway. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2015, 240, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, H.F.; Abdel-Rafei, M.K.; Galal, S.M. Diosmin Attenuates Radiation-Induced Hepatic Fibrosis by Boosting PPAR-γ Expression and Hampering miR-17-5p-Activated Canonical Wnt-β-Catenin Signaling. Biochem. Cell Biol. Biochim. Biol. Cell. 2017, 95, 400–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Liu, Y.; Pan, Z.; Huang, X.; Wang, J.; Cao, W.; Chen, Z. Eupatilin Ameliorates Hepatic Fibrosis and Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation by Suppressing β-Catenin/PAI-1 Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-X.; Huang, Q.-F.; Lin, X.; Wei, J.-B. [Protective effect of isoorientin on alcohol-induced hepatic fibrosis in rats]. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi China J. Chin. Mater. Medica 2013, 38, 3726–3730. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Q.F.; Zhang, S.J.; Zheng, L.; Liao, M.; He, M.; Huang, R.; Zhuo, L.; Lin, X. Protective Effect of Isoorientin-2″-O-α-L-Arabinopyranosyl Isolated from Gypsophila Elegans on Alcohol Induced Hepatic Fibrosis in Rats. Food Chem. Toxicol. Int. J. Publ. Br. Ind. Biol. Res. Assoc. 2012, 50, 1992–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Luo, W.; Chen, S.; Su, H.; Zhu, W.; Wei, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Long, Y.; Shi, Y.; Wei, J. Isovitexin Alleviates Hepatic Fibrosis by Regulating miR-21-Mediated PI3K/Akt Signaling and Glutathione Metabolic Pathway: Based on Transcriptomics and Metabolomics. Phytomed. Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2023, 121, 155117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, R.; Tian, W.; Cao, W.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, H.-N.; Feng, Y.-D.; Li, C.; Li, Z.-Z.; Li, X.-Q. Ligustroflavone Ameliorates CCl4-Induced Liver Fibrosis through down-Regulating the TGF-β/Smad Signaling Pathway. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2021, 19, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batudeligen; Han, Z.; Chen, H.; Narisu; Xu, Y.; Anda; Han, G. Luteolin Alleviates Liver Fibrosis in Rat Hepatic Stellate Cell HSC-T6: A Proteomic Analysis. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2023, 17, 1819–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, X.; Xu, W.; Wang, S.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Deng, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Guo, C. Antifibrotic Effects of Luteolin on Hepatic Stellate Cells and Liver Fibrosis by Targeting AKT/mTOR/p70S6K and TGFβ/Smad Signalling Pathways. Liver Int. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Liver 2014, 35, 1222–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domitrović, R.; Jakovac, H.; Tomac, J.; Sain, I. Liver Fibrosis in Mice Induced by Carbon Tetrachloride and Its Reversion by Luteolin. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2009, 241, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiu, M.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; Yuan, S.; Qin, B.; Sun, J.; Cui, L.; Song, J. Regulation of SIRT1-TLR2/TLR4 Pathway in Cell Communication from Macrophages to Hepatic Stellate Cells Contribute to Alleviates Hepatic Fibrosis by Luteoloside. Acta Histochem. 2023, 125, 151989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Feng, D.; Ye, H.; Liao, W. Nobiletin Alleviated Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition of Hepatocytes in Liver Fibrosis Based on Autophagy-Hippo/YAP Pathway. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2024, 68, e2300529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Weng, J.; Chen, X.; Ma, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, F.; Shao, J.; Zheng, S. Oroxylin A Activates Ferritinophagy to Induce Hepatic Stellate Cell Senescence against Hepatic Fibrosis by Regulating cGAS-STING Pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 162, 114653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Guo, M.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Kong, D.; Shao, J.; Tan, S.; Chen, A.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, Z.; et al. ROS-Dependent Inhibition of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signaling Is Required for Oroxylin A to Exert Anti-Inflammatory Activity in Liver Fibrosis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020, 85, 106637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, M.; He, J.; Jin, H.; Lian, N.; Shao, J.; Guo, Q.; Wang, S.; Zhang, F.; Zheng, S. Oroxylin A Induces Apoptosis of Activated Hepatic Stellate Cells through Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Apoptosis Int. J. Program. Cell Death 2019, 24, 905–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Jia, Y.; Li, M.; Wang, L.; Shao, J.; Guo, Q.; Tan, S.; Ding, H.; Chen, A.; Zhang, F.; et al. Blockade of Glycolysis-Dependent Contraction by Oroxylin a via Inhibition of Lactate Dehydrogenase-a in Hepatic Stellate Cells. Cell Commun. Signal. CCS 2019, 17, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Zhang, Z.; Yao, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhang, F.; Shao, J.; Chen, A.; Zheng, S. Activation of Autophagy Is Required for Oroxylin A to Alleviate Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Liver Fibrosis and Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2018, 56, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seki, N.; Toh, U.; Kawaguchi, K.; Ninomiya, M.; Koketsu, M.; Watanabe, K.; Aoki, M.; Fujii, T.; Nakamura, A.; Akagi, Y.; et al. Tricin Inhibits Proliferation of Human Hepatic Stellate Cells in Vitro by Blocking Tyrosine Phosphorylation of PDGF Receptor and Its Signaling Pathways. J. Cell. Biochem. 2012, 113, 2346–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.-S.; Li, H.-D.; Yang, X.-J.; Li, J.-J.; Xu, J.-J.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Q.-Q.; Yang, L.; He, C.-S.; Huang, C.; et al. Wogonin Attenuates Liver Fibrosis via Regulating Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation and Apoptosis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 75, 105671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.-Q.; Sun, Y.-Z.; Ming, Q.-L.; Tian, Z.-K.; Yang, H.-X.; Liu, C.-M. Ampelopsin Attenuates Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Mouse Liver Fibrosis and Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation Associated with the SIRT1/TGF-Β1/Smad3 and Autophagy Pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 77, 105984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Shi, H.; Ren, F.; Chen, D.; Chen, Y.; Duan, Z. Naringin in Ganshuang Granule Suppresses Activation of Hepatic Stellate Cells for Anti-Fibrosis Effect by Inhibition of Mammalian Target of Rapamycin. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2017, 21, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Said, M.M.; Azab, S.S.; Saeed, N.M.; El-Demerdash, E. Antifibrotic Mechanism of Pinocembrin: Impact on Oxidative Stress, Inflammation and TGF-β /Smad Inhibition in Rats. Ann. Hepatol. 2018, 17, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, F.; Wang, A.; Li, D.; Wang, Y.; Lin, L. Pinocembrin from Penthorum Chinense Pursh Suppresses Hepatic Stellate Cells Activation through a Unified SIRT3-TGF-β-Smad Signaling Pathway. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2018, 341, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, G.; Sun, C.; Wang, J. Hepatoprotective Effect and Possible Mechanism of Phytoestrogen Calycosin on Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Liver Fibrosis in Mice. Naunyn. Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2020, 394, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Yang, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, C.; Chen, G.; Hu, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, H.; et al. Hepatoprotective Effect of Genistein against Dimethylnitrosamine-Induced Liver Fibrosis in Rats by Regulating Macrophage Functional Properties and Inhibiting the JAK2/STAT3/SOCS3 Signaling Pathway. Front. Biosci. Landmark Ed. 2021, 26, 1572–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganai, A.A.; Husain, M. Genistein Attenuates D-GalN Induced Liver Fibrosis/Chronic Liver Damage in Rats by Blocking the TGF-β/Smad Signaling Pathways. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2017, 261, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.; Huang, R.; Zhang, S.; Lin, J.; Wei, L.; He, M.; Zhuo, L.; Lin, X. Protective Effect of Genistein Isolated from Hydrocotyle Sibthorpioides on Hepatic Injury and Fibrosis Induced by Chronic Alcohol in Rats. Toxicol. Lett. 2013, 217, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, A.L.; Montezuma, T.D.; Fariña, G.G.; Reyes-Esparza, J.; Rodríguez-Fragoso, L. Genistein Modifies Liver Fibrosis and Improves Liver Function by Inducing uPA Expression and Proteolytic Activity in CCl4-Treated Rats. Pharmacology 2008, 81, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, H.; Gu, J.; Xu, W.; Yuan, N.; Sun, J.; Li, H. Glabridin Inhibits Liver Fibrosis and Hepatic Stellate Cells Activation through Suppression of Inflammation and Oxidative Stress by Activating PPARγ in Carbon Tetrachloride-Treated Mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 113, 109433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Pan, L.; Zou, H.; Miao, X.; Cheng, J.; Wu, Y. Puerarin Alleviates Liver Fibrosis via Inhibition of the ERK1/2 Signaling Pathway in Thioacetamide-Induced Hepatic Fibrosis in Rats. Exp. Ther. Med. 2019, 18, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.-R.; Wei, S.-J.; Huang, Y.-Q.; Xing, W.; Wang, L.-Y.; Liang, L.-L. Mechanism of Combined Use of Vitamin D and Puerarin in Anti-Hepatic Fibrosis by Regulating the Wnt/β-Catenin Signalling Pathway. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 4178–4185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Shi, X.-L.; Feng, M.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.-H.; Zhao, X.; Han, B.; Ma, H.-C.; Dai, B.; Ding, Y.-T. Puerarin Protects against CCl4-Induced Liver Fibrosis in Mice: Possible Role of PARP-1 Inhibition. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2016, 38, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.; Xu, L.; He, Q.; Liang, T.; Duan, X.; Li, R. Anti-Fibrotic Effects of Puerarin on CCl4-Induced Hepatic Fibrosis in Rats Possibly through the Regulation of PPAR-γ Expression and Inhibition of PI3K/Akt Pathway. Food Chem. Toxicol. Int. J. Publ. Br. Ind. Biol. Res. Assoc. 2013, 56, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Xu, L.; Liang, T.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Duan, X. Puerarin Mediates Hepatoprotection against CCl4-Induced Hepatic Fibrosis Rats through Attenuation of Inflammation Response and Amelioration of Metabolic Function. Food Chem. Toxicol. Int. J. Publ. Br. Ind. Biol. Res. Assoc. 2013, 52, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zheng, N.; He, Q.; Li, R.; Zhang, K.; Liang, T. Puerarin, Isolated from Pueraria Lobata (Willd.), Protects against Hepatotoxicity via Specific Inhibition of the TGF-Β1/Smad Signaling Pathway, Thereby Leading to Anti-Fibrotic Effect. Phytomed. Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2013, 20, 1172–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Ji, G.; Liu, J. Reversal of Chemical-Induced Liver Fibrosis in Wistar Rats by Puerarin. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2006, 17, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-F.; Chen, B.-C.; Lai, D.-D.; Jia, Z.-R.; Andersson, R.; Zhang, B.; Yao, J.-G.; Yu, Z. Soy Isoflavone Delays the Progression of Thioacetamide-Induced Liver Fibrosis in Rats. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 46, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.-X.; Shi, D.-H.; Chen, Y.-X.; Cui, J.-T.; Wang, Y.-R.; Jiang, C.-P.; Wu, J.-H. The Therapeutic Effects of Tectorigenin on Chemically Induced Liver Fibrosis in Rats and an Associated Metabonomic Investigation. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2012, 35, 1479–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, W.; Liao, X.; Xie, R.-J.; Tian, T.; Yu, L.; Liu, X.; Liu, J.; Li, P.; Han, B.; Yang, T.; et al. The Effects of Blueberry Anthocyanins on Histone Acetylation in Rat Liver Fibrosis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 96761–96773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, W.; Liao, X.; Tian, T.; Yu, L.; Liu, X.; Li, B.; Liu, J.; Han, B.; Xie, R.J.; Ji, Q.H.; et al. Study on the Effects of Blueberry Treatment on Histone Acetylation Modification of CCl4-Induced Liver Disease in Rats. Genet. Mol. Res. GMR 2017, 16, 16019188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, W.; Liao, X.; Yu, L.; Tian, T.; Liu, X.; Liu, J.; Cai, L.-J.; Xiao, X.; Xie, R.-J.; Yang, Q. Effects of Blueberries on Migration, Invasion, Proliferation, the Cell Cycle and Apoptosis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. Biomed. Rep. 2016, 5, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Du, J.; Liu, L.; Fan, H.; Yu, Y.; Luo, Y.; Gu, F.; Yu, H.; Liao, X. Anthocyanins Improve Liver Fibrosis in Mice by Regulating the Autophagic Flux Level of Hepatic Stellate Cells by Mmu_circ_0000623. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 3002–3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, R.; Gao, J.; Liu, H.; Zhang, C.; Huang, J.; Fan, J.; Wei, J. Preventive Effect and Mechanism of Anthocyanins from Aronia Melanocarpa Elliot on Hepatic Fibrosis Through TGF-β/Smad Signaling Pathway. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2022, 80, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Wu, Y.; Long, C.; He, P.; Gu, J.; Yang, L.; Liang, Y.; Wang, Y. Anthocyanins Isolated from Blueberry Ameliorates CCl4 Induced Liver Fibrosis by Modulation of Oxidative Stress, Inflammation and Stellate Cell Activation in Mice. Food Chem. Toxicol. Int. J. Publ. Br. Ind. Biol. Res. Assoc. 2018, 120, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Guo, H.; Shen, T.; Tang, X.; Yang, Y.; Ling, W. Cyanidin-3-O-β-Glucoside Purified from Black Rice Protects Mice against Hepatic Fibrosis Induced by Carbon Tetrachloride via Inhibiting Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 6221–6230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domitrović, R.; Jakovac, H. Antifibrotic Activity of Anthocyanidin Delphinidin in Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Hepatotoxicity in Mice. Toxicology 2010, 272, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Wu, C.; Huang, W. Malvidin Induces Hepatic Stellate Cell Apoptosis via the Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Pathway and Mitochondrial Pathway. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 5095–5106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.-S.; Li, X.-X.; Li, H.-T.; Zhang, Y. Pelargonidin Ameliorates CCl4-Induced Liver Fibrosis by Suppressing the ROS-NLRP3-IL-1β Axis via Activating the Nrf2 Pathway. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 5156–5165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Nan, J.-X.; Zhao, Y.Z.; Woo, S.W.; Park, E.-J.; Kang, T.-H.; Seo, G.S.; Kim, Y.-C.; Sohn, D.H. The Chalcone Butein from Rhus Verniciflua Shows Antifibrogenic Activity. Planta Med. 2003, 69, 990–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Tian, H.; Chen, J.; Huang, D.; Ding, F.; Ma, T.; Xi, J.; Wu, C.; Zhang, Y. Isobavachalcone Attenuates Liver Fibrosis via Activation of the Nrf2/HO-1 Pathway in Rats. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 128, 111398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, H.; Sidhu, S.; Chopra, K.; Khan, M.U. Hepatoprotective Effect of Trans-Chalcone on Experimentally Induced Hepatic Injury in Rats: Inhibition of Hepatic Inflammation and Fibrosis. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2016, 94, 879–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorn, C.; Heilmann, J.; Hellerbrand, C. Protective Effect of Xanthohumol on Toxin-Induced Liver Inflammation and Fibrosis. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2012, 5, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorn, C.; Kraus, B.; Motyl, M.; Weiss, T.S.; Gehrig, M.; Schölmerich, J.; Heilmann, J.; Hellerbrand, C. Xanthohumol, a Chalcon Derived from Hops, Inhibits Hepatic Inflammation and Fibrosis. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2010, 54 (Suppl. S2), S205–S213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, C.T.; Nguyen, G.; Park, S.Y.; Dong, H.N.; Cho, Y.K.; Lee, J.-H.; Im, S.-S.; Choi, D.-H.; Cho, E.-H. Phloretin Ameliorates Succinate-Induced Liver Fibrosis by Regulating Hepatic Stellate Cells. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 38, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, Y. Icariin-Induced miR-875-5p Attenuates Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition by Targeting Hedgehog Signaling in Liver Fibrosis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 35, 482–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algandaby, M.M.; Breikaa, R.M.; Eid, B.G.; Neamatallah, T.A.; Abdel-Naim, A.B.; Ashour, O.M. Icariin Protects against Thioacetamide-Induced Liver Fibrosis in Rats: Implication of Anti-Angiogenic and Anti-Autophagic Properties. Pharmacol. Rep. PR 2017, 69, 616–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]