Abstract

Background: Health-related mobile applications (apps) are rapidly increasing in number. There is an urgent need for assessment tools and algorithms that allow the usability and content criteria of these applications to be objectively assessed. The aim of this work was to establish and validate a concept for orthopedic societies to rate health apps to set a quality standard for their safe use. Methods: An objective rating concept was created, consisting of nine quality criteria. A self-declaration sheet for app manufacturers was designed. Manufacturers completed the self-declaration, and the app was examined by independent internal reviewers. The pilot validation and analysis were performed on two independent health applications. An algorithm for orthopedic societies was created based on the experiences in this study flow. Results: “Sprunggelenks-App“ was approved by the reviewers with 45 (98%) fulfilled criteria and one (2%) unfulfilled criterion. “Therapie-App” was approved, with 28 (61%) met criteria, 6 (13%) unfulfilled criteria and 12 (26%) criteria that could not be assessed. The self-declaration completed by the app manufacturer is recommended, followed by a legal and technical rating performed by an external institution. When rated positive, the societies’ internal review using independent raters can be performed. In case of a positive rating, a visual certification can be granted to the manufacturer for a certain time frame. Conclusion: An objective rating algorithm is proposed for the assessment of digital health applications. This can help societies to improve the quality assessment, quality assurance and patient safety of those apps. The proposed concept must be further validated for inter-rater consistency and reliability.

1. Introduction

Digitization has become an integral part of everyday life due to the expansion of the capabilities of the Internet as well as the use of smartphones and corresponding mobile applications (apps) [1]. Apps can facilitate daily life on many levels and have also found their place in the healthcare sector. Consequently, patients and physicians thrive on gaining maximum advantages from digital mobile health products in terms of screening, diagnostics, therapy and rehabilitation [2,3]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has stressed that new technologies should be employed to benefit from the full potential of digitalization. The topic’s relevance was further increased by the current COVID-19 pandemic [4]. There are many “fitness” and “lifestyle” or even diagnostic and therapy-related smartphone apps available [5]. However, the offer in the major app stores is extensive and confusing; for example, in July 2022, there were 54,603 apps in the category “Medical” in the Google® Play Store alone [6]. The highly liberal app markets have a drawback, as they are poorly regulated. App quality control is minimal [7]. In addition to that, the rapid development of health-related apps makes it increasingly difficult for consumers, physicians, and healthcare organizations to identify appropriate and high-quality apps in commercial app stores [8,9]. While apps are presented with a star rating system in commercial app stores, there is no indication of their professional and technical quality. Star rating systems can be an indicator of user satisfaction, which does not necessarily equate with the clinical quality and safety of the application [10]. There are also concerns about inappropriate and inaccurate health-related apps compromising or negatively effecting the user’s health and safety [11,12,13]. Several studies have, therefore, aimed to elaborate assessment criteria and tools for health-related apps [14]. However, assessment criteria also seem to be very heterogenous, which might reflect on different assessment approaches. Over the years, several players from the private and public sectors have attempted to improve the lack of quality and regulation on the app market, but none of these attempts prevailed. One exception is the regulatory scheme for medical devices that only applies to a very limited number of apps [15]. Passing the regulatory process is one possible criterion for quality, but “quality” comprises many more aspects, such as technical soundness, as proof of basic functionality. Clearly, there is a need for criteria with which users (healthy laypeople, patients or medical staff) can objectively identify whether certain app products are suitable for their own needs [16,17].

In some countries, it has been proposed to create prescription-based smartphone apps that medical insurance can cover. Worldwide, Germany was the first country to recommend introducing the prescription of digital health applications via federal law. This increased the need for adequate quality assessments [18,19,20]. Here, the certification of medical products is well established and has proven to contribute to quality enhancement in various fields of the healthcare system [21,22].

There are different approaches to creating an objective evaluation of apps based on defined quality criteria [7]. Some institutions are already pursuing the path of certification based on predefined quality criteria, such as the NHS App library or the Diabetes App seal “DiaDigital” of the German Diabetes Associations [23,24,25]. While validated test procedures are available [26,27,28], literature research on PubMed® using the search terms “certificate + mobile app” only revealed 77 results (as of October 2022) with very heterogenic approaches.

An appropriate solution for quality assurance of medical and health-related apps that equally considers the character of the market, the technology, the use, the users, and the setting is still missing but needed [11]. A unified set of criteria for the self-declaration of the quality of health apps was created in 2019 [29].

Previous data have shown that smartphone apps are still underused in the medical sector but could enhance patient satisfaction and communication between patients and physicians, as well as the quality of care [30]. In orthopedics, studies have revealed that patients would be willing to use telehealth and smartphone applications [31,32]. Furthermore, smartphone apps are used, e.g., to support the process of lower-back pain treatment and proved not to be inferior to conventional physiotherapy [33]. However, these apps may lack medical evidence and professional involvement, which results in the demand for the regulation and evaluation of such apps [34].

Thus, this work aimed to establish and validate a user-friendly rating tool for health-related apps in the field of orthopedics, which can be used by orthopedic societies to certify apps, thereby setting quality standards in terms of clinical quality and safe usage of apps of both patients and physicians.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Setting

To create a workable, stable, validated and clearly structured concept for app rating, a review of the previously published literature was conducted on PubMed®.

In accordance with AWMF recommendations (Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften e.V. or Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany), the proposed concept is based on nine central quality principles, including applicable sub-principles for the rating of medical applications [29]. Besides the main criteria, sub-criteria of each main criteria were developed (e.g., (A) “risk awareness” and (B) “risk handling” in “Appropriateness of Risk”). This chosen app rating concept has been evaluated in several publications. The central principles are presented and elucidated in Table 1 [15,35].

Table 1.

Detailed explanation of the nine central quality principles for medical apps, as proposed by AWMF.

Since there are no examples in the digital or print literature, a self-declaration sheet was created based on these principles that must be completed by the application manufacturer.

To ease the process of app rating for orthopedic societies and to make the procedures transparent for manufacturers, an evaluation sheet was created, which must be filled in by appointed representatives of the respective orthopedic/traumatological society to evaluate the application.

2.2. Pilot Validation

For the validation process we used a sample of two apps. For the analysis, we approached two independent health-application manufacturers:

- Sprunggelenks-App (“Ankle-Joint-App”), Mediploy GmBH, 40764 Langenfeld, Germany.

- Therapie-App (“Therapy app”), Bauerfeind®, 07937 Zeulenroda-Triebes, Germany.

Both manufacturers were informed that the evaluation process was only for study purposes and that no certification would be granted in case of positive validation.

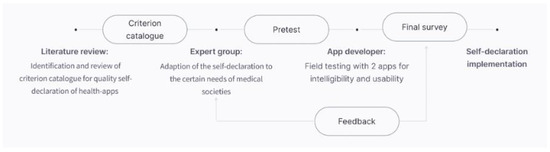

After receiving the self-declaration reports of the manufacturers, each application was rated by the coauthors S.T. and S.B. for validation [36]. The workflow of the study is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Workflow of the study.

2.3. Recommendations for Orthopedic Societies

Based on the experiences and findings of the chosen approach, a strategy for a potential procedure for orthopedic societies was created on how to create an internal validation and recommendation process for patients and colleagues about relevant apps in their field.

2.4. Justification of Methods Used

The synthesis of the structured concept for app rating was based on well-established quality criteria, which makes our concept robust and pre-validated. A pilot validation was performed using two independent app manufactures who were naïve to the proposed self-declaration sheet, which eradicated any bias.

3. Results

The free PubMed search revealed 1256 published articles in 2020. Most of the studies focused on the assessment of the respective health application by patients. No publication described a standardized certification algorithm for medical apps.

3.1. Self-Declaration Sheet

A self-declaration sheet (see Table 2) for the manufacturer was synthesized based on the previously published criteria for the self-declaration of the quality of health apps [29]. The self-declaration sheet is based on the previously published nine quality criteria. Sub-criteria were restructured according to the need to rate digital health applications in the fields of orthopedics and traumatology. Each quality principle is explained briefly to make the self-declaration sheet better understandable (Table 2).

Table 2.

Self-declaration sheet for app manufacturers. Application for acceptance of the app review.

3.2. Society Evaluation Sheet

The society evaluation sheet (see Table 3) focuses on the primary data of the proposed health app (manufacturer details, the purpose of the proposed application, technical evaluation, etc.) Furthermore, every sub-criterion within the quality principles can be rated as fulfilled (green), not fulfilled (red) or not assessable (yellow). In addition, six sub-criteria regarding the test quality criteria must be answered accordingly. At the end of the sheet, the reviewer can add general recommendations and further comments and classify the proposed app as approved or not approved.

Table 3.

Society evaluation sheet: rating sheet for internal assessment through independent internal reviewers.

3.3. Pilot Validation

Besides the app’s “demographics” (store availability, aim, specifications, etc.), there were 46 sub-criteria to be answered regarding the manufacturer’s fulfilment. Since this was a pilot validation, the technical assessment by an external company or society was not performed. “Sprunggelenks-App“ (Ankle app) by Mediploy GmbH was approved by the reviewer and was rated with 45 (98%) fulfilled criteria and one (2%) not fulfilled criterion. The reviewers also approved “Therapie-App” (Therapy app) by Bauernfeind®. However, the application was rated with 28 (61%) criteria that were met, while 6 (13%) criteria were not fulfilled. An additional 12 (26%) criteria could not be assessed (Table 4). Due to data security reasons, we did not include the detailed answer sheets of the manufacturers.

Table 4.

Results of the pilot validation using “Therapie-App” and “Sprunggelenks-App”. Sub-criteria were rated as fulfilled (green), not fulfilled (red) or not assessable (black).

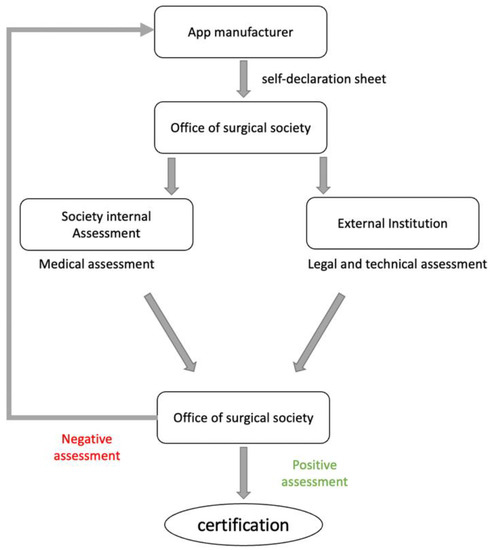

3.4. Proposal for Society Assessment

Based on the experiences of the validation process, the below procedure is suggested.

The evaluation process is started after the manufacturer has submitted the self-declaration form, which can be downloaded from the society’s website. If all documents are completed, the submitted application should be sent to an external institution that evaluates legal and technical aspects. If sufficient, the societies’ internal review (Table 3), using independent raters, should be performed. Independent raters for potential health apps should be chosen for the different orthopedic sections (e.g., “upper extremity” or “spine” when applicable). If rated positive, the society’s logo could be granted to the manufacturer as visual certification. If rated negative, the manufacturer should be given a period of 3 months to improve the app and/or declaration. The certificate should be valid for a limited timespan only, for example, for three years, after which a re-evaluation is required (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flowchart depicting the proposed algorithm for the rating of mobile apps performed by orthopedic societies.

3.5. Practical Implications

The practical experiences of the rating process are as follows:

- The initial reviewing process takes 2–3 h.

- In case of uncertainties and the need to contact the manufacturer, the initial reviewing process can be significantly prolonged.

- A coordinator between the society and the reviewer should be chosen for an initial briefing regarding the process.

- An external institution must review the legal and technical requirements of the apps. Apparent violations of legal and technical requirements would, therefore, already lead to the exclusion of the app from the rating process, even before the professional content assessment.

- Financial compensation for coordinators and reviewers should be considered to maintain a general willingness to review proposed health applications. We suggest that the individual manufacturer covers this.

4. Discussion

Using smartphones and corresponding mobile applications (apps) provides access to information and interventions at any time and in various settings. Previous studies have shown that health-related apps have the potential to make a significant difference in the health outcomes of patients [37]. However, there are also concerns about inappropriate apps that could potentially limit or even negatively affect patient health outcomes. Further concerns include privacy and data security issues [11,38,39].

The rapid development of health-related apps makes it increasingly difficult for consumers, physicians and healthcare organizations to identify appropriate and high-quality apps in commercial online application stores [8,9]. For the selection of apps, users often rely on star rating systems and user reviews provided by the respective app stores, even if these evaluation methods can be misleading [10,40]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to support consumers, both patients and recommending physicians, in identifying appropriate and safe apps.

There have been various approaches to assess health-related mobile applications in the past [41]. A common tool that has been validated is the Mobile App Rating Scale (MARS), developed as a multidimensional measure tool to pilot, classify and assess the quality of mobile health apps [27]. The MARS consists of 23 items in five subscales (engagement, functionality, aesthetics, and information quality and subjective quality). The subjective quality subscale is, however, excluded from the overall mean app quality score in this scoring system [27]. A separate version of the MARS for end users, the uMARS, was also created as a simple tool for users, to assess the quality of health-related apps [42]. On the other hand, the AWMF recommendation, which has been used for the app-rating in this study, proposes nine central quality principles for the rating of medical apps, with associated sub-criteria [29]. This allows an even more differentiated and discriminate rating of the apps to be performed, and at the same time, has fewer main objectives, which makes the proposed rating system handier. Furthermore, the MARS has been validated as a tool for the comparison of health applications rather than for the rating of specific health applications performed by, e.g., medical societies.

In this study, we introduce an algorithm for orthopedic/traumatological societies that would allow them to assess and certify the structural and content-related quality of commercial apps that focus on orthopedic/traumatological conditions. The proposed rating system is based on standardized objective items. This visual certification could help users, consumers and medical professionals to choose the appropriate apps for their needs. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study that describes the development of an algorithm that aims to certify clinically relevant and safe apps in the field of orthopedics/ traumatology.

The award of a certificate or seal of approval goes hand in hand with an excessive level of responsibility, as users trust its validity [43]. Valid test processes usually require a strict methodical approach and the implementation of state-of-the-art test processes. Quality losses in the test are inevitable if this cannot be guaranteed in the long term. However, it should also be considered that the affixing of quality seals to medical products may be problematic in a legal sense, as at least in Europe, the CE marking does not tolerate any other markings that could potentially lead to confusion [44]. To abstain from any evaluation completely, however, contradicts the obvious need for qualitative guidance for patients and doctors from the authors’ point of view.

An app-rating process based on self-declarations is proposed. Manufacturers would have the possibility to let their applications be certified by the respective orthopedic/traumatological society. After an initial assessment of legal and technical aspects performed by an external company, the application is evaluated on content quality by a reviewer from the respective society. Following this proposed process, it could be assured that the health application is checked for correctness in terms of medical standards and quality requirements.

The legal and formal requirements are primarily in a regulatory gray area and are regularly overtaken by rapidly and dynamically developing technical innovations. A potentially faulty test identified by the user can immediately lead to a loss of integrity on the part of the testing / certifying institution.

We propose the logo “APProved by (name of the respective society)” for the visual certification of the application in case of a positive rating, albeit with a limited validity of this certification (e.g., three years). This restriction would ensure that health-related applications evaluated following this process are repeatedly checked for quality. Implications of this process are that it requires good coordination, is time intensive, and can take up to 6 h when there are uncertainties on the reviewer’s side.

A self-declaration process is proposed, as the comprehensive search for suitable health applications in the different app stores would be too strenuous for the respective societies, even when using search engines or specially programmed algorithms. Furthermore, orthopedic/traumatological societies do not have the capacity to evaluate more variables of proposed applications than the medical/technical facets (e.g., legal concerns, technical requirements). One significant advantage of this concept of self-declaration is that the technical checks of the proposed apps are performed by external institutions, which reduces the workload for the orthopedic/traumatological society, which would only be responsible for strict medical feasibilities. Furthermore, the respective society cannot be made liable for legal inconsistencies.

However, there were also limitations to this study. First, only two health-related apps were rated in this study by only two reviewers for pilot validation. The consistency and inter-rater reliability could, therefore, not be evaluated. Furthermore, only one certifying approach was examined and tested. Alternative frameworks for certification processes, including other rating scales, were not considered.

5. Conclusions

Due to an increasing number of medical smartphone applications (apps), there is an urgent need for an objective quality assessment for both usability and content. The proposed rating algorithm for digital health applications in orthopedics and traumatology can help societies to improve the quality assessment and quality assurance of those apps. The proposed concept should be further tested for inter-rater consistency and reliability and should be validated in future studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, data analysis and writing of the manuscript, J.S.; editing and writing, Y.Y.; co-writing and co-conceptualization, F.D.; editing and critical review, U.-V.A.; editing and critical review, S.T.; editing and critical review, J.J.; editing and critical review, D.P.; editing and critical review, S.L.; editing and critical review, S.B.; conceptualization and critical review: D.A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank A. M. Broughton as a native speaker for reviewing the English language in this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Krebs, P.; Duncan, D.T. Health App Use Among US Mobile Phone Owners: A National Survey. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2015, 3, e4924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongworawat, M.D.; Capistrant, G.; Stephenson, J.M. The Opportunity Awaits to Lead Orthopaedic Telehealth Innovation: AOA Critical Issues. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2017, 99, e93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashfaq, A.; Esmaili, S.; Najjar, M.; Batool, F.; Mukatash, T.; Al-Ani, H.A.; Koga, P.M. Utilization of Mobile Mental Health Services among Syrian Refugees and Other Vulnerable Arab Populations—A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health: Workforce 2030; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- Higgins, J.P. Smartphone Applications for Patients’ Health and Fitness. Am. J. Med. 2016, 129, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Number of mHealth Apps Available in the Google Play Store from 1st Quarter 2015 to 2nd Quarter 2022. online2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/779919/health-apps-available-google-play-worldwide/ (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- Albrecht, U.V.; Hillebrand, U.; von Jan, U. Relevance of Trust Marks and CE Labels in German-Language Store Descriptions of Health Apps: Analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018, 6, e10394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henson, P.; David, G.; Albright, K.; Torous, J. Deriving a practical framework for the evaluation of health apps. Lancet Digit. Health 2019, 1, e52–e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyatt, J.C. How can clinicians, specialty societies and others evaluate and improve the quality of apps for patient use? BMC Med. 2018, 16, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Drouin, K.; Newmark, L.P.; Lee, J.; Faxvaag, A.; Rozenblum, R.; Pabo, E.A.; Landman, A.; Klinger, E.; Bates, D.W. Many Mobile Health Apps Target High-Need, High-Cost Populations, But Gaps Remain. Health Aff. 2016, 35, 2310–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, B.; Hickey, E.; Mitchell, C.; Patel, M. The need for quality assurance of health apps. BMJ Br. Med. J. 2015, 351, h5915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Torous, J.; Nicholas, J.; Larsen, M.E.; Firth, J.; Christensen, H. Clinical review of user engagement with mental health smartphone apps: Evidence, theory and improvements. Evid. Based Ment. Health 2018, 21, 116–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, T.L.; Wyatt, J.C. mHealth and mobile medical Apps: A framework to assess risk and promote safer use. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, A.E.; Davenport, T.A.; Wong, T.; Moon, H.-W.; Hickie, I.B.; LaMonica, H.M. Evaluating the quality and safety of health-related apps and e-tools: Adapting the Mobile App Rating Scale and developing a quality assurance protocol. Internet Interv. 2021, 24, 100379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrecht, U.V.; Malinka, C.; Long, S.; Raupach, T.; Hasenfuss, G.; von Jan, U. Quality Principles of App Description Texts and Their Significance in Deciding to Use Health Apps as Assessed by Medical Students: Survey Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019, 7, e13375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malinka, C.; von Jan, U.; Albrecht, U.V. Prioritization of Quality Principles for Health Apps Using the Kano Model: Survey Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2022, 10, e26563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nouri, R.; R Niakan Kalhori, S.; Ghazisaeedi, M.; Marchand, G.; Yasini, M. Criteria for assessing the quality of mHealth apps: A systematic review. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2018, 25, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bundesministerium für Gesundheit. Ärzte Sollen Apps Verschreiben Können Gesetz für eine Bessere Versorgung durch Digitalisierung und Innovation (Digitale-Versorgung-Gesetz—DVG). 2019. Available online: https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/digitale-versorgung-gesetz.html#:~:text=Apps%20auf%20Rezept%2C%20Videosprechstunden%20einfach,2019%20in%20Kraft%20getreten%20ist (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Bundesministerium für Gesundheit. Gesetzentwurf der Bundesregierung Entwurf eines Gesetzes für eine Bessere Versorgung durch Digitalisierung und Innovation (Digitale-Versorgung-Gesetz—DVG). 2019. Available online: https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/fileadmin/Dateien/3_Downloads/Gesetze_und_Verordnungen/GuV/D/Digitale-Versorgung-Gesetz_DVG_Kabinett.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Bundesgesetzblatt. Gesetz für eine Bessere Versorgung durch Digitalisierung und Innovation (Digitale-Versorgung-Gesetz) Vom 09. Dezember 2019. Bundesgesetzblatt Jahrgang 2019 Teil 1 Nr. 49: Bundesanzeiger Verlag GmbH. 2019. Available online: https://dejure.org/BGBl/2019/BGBl._I_S._2562 (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- EndoCert GmbH. Das Weltweit Erste Zertifizierungssystem in der Endoprothetik; 2020. Available online: https://endocert.de/?view=article&id=12:das-weltweit-erste-zertifizierungssystem-in-der-endoprothetik&catid=14 (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- KTQ-GmbH. Kooperation für Transparenz und Qualität im Gesundheitswesen GmbH; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- NHS. NHS Apps Library; NHS: London, UK, 2019.

- DIA Event und Promotion GmbH. DiaDigital; DIA Event und Promotion GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Johannes Bittner, T.T. AppQ: Gütekriterien-Kernset für mehr Transparenz bei Digitalen Gesundheitsanwendungen; 2019. Available online: https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/de/unsere-projekte/der-digitale-patient/projektnachrichten/appq/ (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Messner, E.M.; Terhorst, Y.; Barke, A.; Baumeister, H.; Stoyanov, S.; Hides, L.; Kavanagh, D.; Pryss, R.; Sander, L.; Probst, T. Development and Validation of the German Version of the Mobile Application Rating Scale (MARS-G). JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2020, 8, e14479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoyanov, S.R.; Hides, L.; Kavanagh, D.J.; Zelenko, O.; Tjondronegoro, D.; Mani, M. Mobile app rating scale: A new tool for assessing the quality of health mobile apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2015, 3, e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrecht, U.-V. APP-SYNOPSIS—USER-DEUTSCHE VERSION. Available online: http://www.app-synopsis.de (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Albrecht, U.-V. Einheitlicher Kriterienkatalog zur Selbstdeklaration der Qualität von Gesundheits-Apps; Version 1.2 vom 22.06.2019 ed: Ehealth Suisse. 2019. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334192980_Einheitlicher_Kriterienkatalog_zur_Selbstdeklaration_der_Qualitat_von_Gesundheits-Apps (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Datillo, J.R.; Gittings, D.J.; Sloan, M.; Hardaker, W.M.; Deasey, M.J.; Sheth, N.P. “Is There An App For That?” Orthopaedic Patient Preferences For A Smartphone Application. Appl. Clin. Inform. 2017, 8, 832–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, J.; Keller, F.; Pape, H.-C.; Osterhoff, G. Would patients undergo postoperative follow-up by using a smartphone application? BMC Surg. 2020, 20, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, J.; Osterhoff, G.; Kaufmann, E.; Estel, K.; Neuhaus, V.; Willy, C.; Hepp, P.; Pape, H.; Back, D.A. What is the acceptance of video consultations among orthopedic and trauma outpatients? A multi-center survey in 780 outpatients. Injury 2021, 52, 3304–3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toelle, T.R.; Utpadel-Fischler, D.A.; Haas, K.-K.; Priebe, J.A. App-based multidisciplinary back pain treatment versus combined physiotherapy plus online education: A randomized controlled trial. NPJ Digit. Med. 2019, 2, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, S.J.; Robertson, G.A.; Connor, K.L.; Brady, R.R.; Wood, A.M. Smartphone apps for orthopaedic sports medicine—A smart move? BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2015, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrecht, U.V.; Framke, T.; von Jan, U. Quality Awareness and Its Influence on the Evaluation of App Meta-Information by Physicians: Validation Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019, 7, e16442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airaksinen, N.K.; Nurmi-Luthje, I.S.; Kataja, J.M.; Kroger, H.P.J.; Luthje, P.M.J. Cycling injuries and alcohol. Injury 2018, 49, 945–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Lee, E. Effectiveness of Mobile Health Application Use to Improve Health Behavior Changes: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Healthc. Inf. Res. 2018, 24, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tangari, G.; Ikram, M.; Sentana, I.W.B.; Ijaz, K.; Kaafar, M.A.; Berkovsky, S. Analyzing security issues of android mobile health and medical applications. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2021, 28, 2074–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, A.; Kedia, S.; Wyant, D.K.; Ahn, S.; Bhuyan, S.S. Use of mobile health applications for health-promoting behavior among individuals with chronic medical conditions. Digit. Health 2019, 5, 2055207619882181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Chantal, P.L.; Chagnon, A.; Cardinal, M.; Faieta, J.; Guertin, A. Evidence of User-Expert Gaps in Health App Ratings and Implications for Practice. Front. Digit. Health 2022, 4, 765993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handel, M.J. mHealth (Mobile Health)—Using Apps for Health and Wellness. Explore 2011, 7, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoyanov, S.R.; Hides, L.; Kavanagh, D.J.; Wilson, H. Development and Validation of the User Version of the Mobile Application Rating Scale (uMARS). JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2016, 4, e72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, D.G. Maintenance of Certification and the Challenge of Professionalism. Pediatrics 2017, 139, e20164371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentley, D. CE marking—What does it really mean? J. Tissue Viability 1999, 9, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).