Abstract

Background: Facebook represents a new dimension for global information sharing. Suicidal behaviours and attempts are increasingly reported on Facebook. This scoping review explores the various aspects of suicidal behaviours associated with Facebook, discussing the challenges and preventive measures. Methods: PubMed, Google Scholar, and Scopus were searched for related articles published in English up to October 2021, using different combinations of “Facebook” and “suicide”. A group of experts comprising consultant psychiatrists screened the records and read the full-text articles to extract relevant data. Twenty-eight articles were chosen as relevant and included in the review under four selected themes. Results: Facebook impacts on suicidal behaviours in different aspects. Announcing suicides through sharing notes or personal information may lead to the prediction of suicide but be harmful to the online audience. Live-streaming videos of suicide is another aspect that questions Facebook’s ability to monitor shared contents that can negatively affect the audience. A positive impact is helping bereaved families to share feelings and seek support online, commemorating the lost person by sharing their photos. Moreover, it can provide real-world details of everyday user behaviours, which help predict suicide risk, primarily through novel machine-learning techniques, and provide early warning and valuable help to prevent it. It can also provide a timeline of the user’s activities and state of mind before suicide. Conclusions: Social media can detect suicidal tendencies, support those seeking help, comfort family and friends with their grief, and provide insights via timelining the users’ activities leading to their suicide. One of the limitations was the lack of quantitative studies evaluating preventative efforts on Facebook. The creators’ commitment and the users’ social responsibility will be required to create a mentally healthy Facebook environment.

1. Introduction: Suicides and Social Media

Globally, 700,000 people die yearly by suicide, and 77% of these suicides occur in low and middle-income countries [1]. Suicides are frequently under-reported for various societal, economic, and political reasons; therefore, the actual number of suicides is believed to be significantly higher [2]. Early cases have been documented wherein users took to social media to post suicide notes, announce, or even broadcast their suicide attempts [3]. Social connectedness, school support, and family relationships are major protective factors against suicide. Further, the use of distractions, problem-solving skills, and high self-esteem reduced the risk of developing suicidal ideation [4]. Some risk factors in young people for suicide include lack of social support, imprisonment, poor life skills, family history, diagnosed mental disorders, adverse life events, abuse in childhood, academic stress, use of alcohol, and cyberbullying [5].

Today, social media has become a mainstay of communication, and out of the diverse options available, Facebook is the largest known platform, with close to three billion users [6]. Social media broadens the scope and content of human communication and allows for free expression and selective representation of undesirable behaviour [7]. An emerging trend in the last few years is announcing suicide on Facebook [8]. It is observed that young people who self-harm use the Internet frequently to express their distress, and there is a rising trend of people dying by suicide after posting on social media, which is found to have assortative patterns [9]. Certain users post their intent publicly on social media and then die by suicide, and a number of such cases have been reported [6].

According to studies, expressing suicidal intent via social media platforms might be seen as an unconventional means of seeking help, and this has encouraged researchers to look into harnessing the powers of social media to prevent suicides [10]. It is observed that users are keen to be helpful; however, they lack the knowledge required. Efforts focused on empowering social media users, such as forming rescue or support groups, would make for a convivial and welcoming online world [11,12,13]. Prevention of suicides by monitoring social media posts and analysing online behaviour would be possible [14]. Artificial intelligence-driven suicide prediction methods are tested and used that could improve the capacity to identify those at risk of self-harm and suicide, and, hopefully, could save lives [15].

Although the associations between suicidal behaviour and social media can be investigated in several psychosocial aspects, few studies have addressed this issue to consolidate the relevant evidence available in the literature. There is currently no report on the percentage of Facebook-associated suicides that lead to death. The extent of the detrimental effects that social media can have in this regard, and their possible contributions to predicting and preventing suicidal behaviours remain controversial. We aimed to identify factors related to announcing suicide on Facebook, live-streaming of suicidal behaviour, grieving suicide, and preventing suicides to understand the socio-cultural implications and the role of the audience and how one can prevent such events. Out of all the social media platforms, we focused on Facebook, which has the largest number of followers and a unique online culture [16,17].

2. Methods

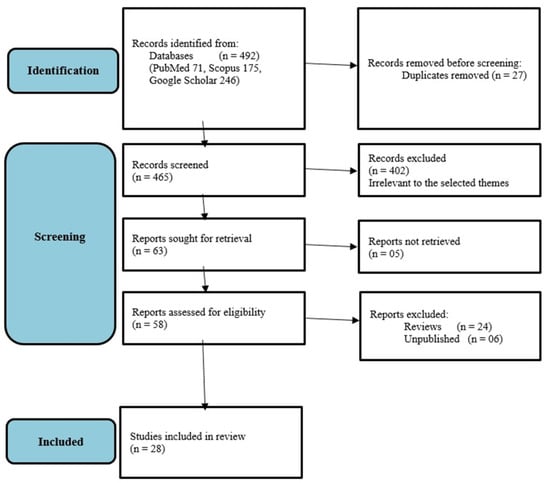

We searched Google Scholar, Scopus, and PubMed up to October 2021 from the beginning of data for articles related to announcing suicide on Facebook, live-streaming of suicidal behaviour, grieving suicide, and preventing suicides. The selected themes were decided by a panel of experts comprising consultant psychiatrists (authors) who have published on mental-health aspects of social media use. The search strategy used on PubMed was ‘Facebook suicide [Title/Abstract]) OR (Facebook suicidal [Title/Abstract]) AND (English Language), and it yielded seventy-one initial results. We used the search term “Facebook suicide” on Google Scholar, leading to 246 article findings. We searched article title, abstract, and keywords as “Facebook suicide” on Scopus, leading to 175 articles. A relevant article was only selected if the publication provided information about an association between suicidal behaviour and Facebook use in the selected themes. A group of consultant psychiatrists went through all of the articles, and data were extracted from each original article. Only English language peer-reviewed studies were included in the review. We also reviewed the reference lists of included articles for additional publications. Abstracts, unpublished research, reviews, and duplicates were excluded. All search results were perused on the relevance to the topics announcing suicide on Facebook, live-streaming of suicidal behaviour, grieving suicide, and preventing suicides. The articles not reporting data on the above themes were excluded after two consultant psychiatrists studied each one. Consultant psychiatrists as experts identified key points relevant to each theme in the study. A key point was defined as a finding of the selected study that is relevant for identifying and preventing suicides concerning Facebook use.

3. Results

Figure 1 shows the study selection process. We have summarised the significant findings of the most relevant studies that were retrieved by our search of the literature into four distinctive categories: announcement of suicide decision on Facebook (Table 1); video-streaming of the act of suicide on Facebook (Table 2); using Facebook for grieving after a suicide (Table 3); and using Facebook for prevention of suicide (Table 4). The tables include key points relevant to the topics and themes selected by the consultant psychiatrists. As indicated in Table 1, the announcement of suicide on Facebook can be made through sharing suicide notes, personal information, or preceding life events leading to suicide, which can be helpful in the prediction of suicide. Facebook also provides a large audience with whom the suicidal behaviours can be shared, which can negatively affect them.

Figure 1.

Publication selection process.

Table 1.

Announcing suicide on Facebook.

Table 2.

Live-streaming suicide on Facebook.

Table 3.

Facebook and grieving suicide.

Table 4.

Facebook and Suicide Prevention.

Table 2 summarises the reported data on cases where Facebook shared the live-streaming of videos of suicide online. The main concerns were the ability of Facebook to monitor the content of these videos and how it can prevent their spread, which can negatively affect the audience.

One of the major advantages of Facebook is the forum it provides for grieving family members or friends, through which they can share feelings and obtain support from other users online, as well as commemorating the dead person by sharing their photos or posts (Table 3).

Table 4 summarises the studies on another advantageous use of Facebook: suicide prevention. There have been different suggestions and actions in this regard, such as artificial intelligence algorithms that can predict and help prevent suicides, online support groups where people can share their distress, reduce the risk of suicide, and help other users who commiserate with the person sharing their hardships and feelings.

4. Discussion

Ref. [1], we explored the association between suicidal behaviour with Facebook and selected 28 studies as relevant out of 492 search findings. The review focused on four areas: announcing suicide; live-streaming; grieving suicide; and prevention strategies.

More people sharing personal information openly on Facebook allows them a chance to reach out to others even without knowing them. There are several reports of reported suicides where a suicide note was shared on Facebook beforehand [3,6,18,20]. In emotionally distressful situations, it may be possible to offer support and prevent a potential suicide [24]. By analysing public posts and suicide notes, social media platforms should identify users at an elevated risk and provide online support [3,6,18]. Suicide notes found on Facebook were associated with a younger age, psychoactive substance use, and previous non-suicidal self-injury in the individual [20].

Further, young people could express and share their suicidal thoughts on social media more conveniently than with their families or professionals [8]. An unrestricted reach for self-expression was provided by Facebook and encouraged people in distress to normalise self-harming behaviour, and some even competed with others to injure themselves more seriously [21,22]. Apart from the opportunity to express their distress, repetitive negative thinking, which is likely to be present in many in emotional distress, and addictive Facebook use are associated with suicidal ideation and suicidal behaviour. This may have led to a social–emotional environment invigorating potential harm directed at self [40].

Few studies have investigated the links between social media use, personality disorders, and traits [42,43]. For example, having more Facebook friends has been associated with mania, histrionic, and narcissistic personality disorder symptoms, and fewer symptoms of dysthymia and schizoid personality disorder [43]. Facebook users, compared to non-users, reportedly had higher self-esteem and narcissism levels [42]. These findings possibly underscore the crucial impacts of personality disorders and their traits on suicidal behaviours via social media.

People stream their suicide attempts live, and timely interventions with the support of the regional mental health teams are required to save lives [23]. At times, loved ones are left helpless by such incidents, and some have taken legal action against the social media platform [44]. Persons who live-streamed suicidal behaviour were mainly under 35 years of age, and a majority were male students resorting to hanging and poisoning to harm themselves [24]. The victims had experienced relationship conflicts and academic stressors, as seen by their most recent posts before harm, and it is shown that stress-management interventions through Facebook are beneficial for young people [45].

Memorial pages on Facebook have given a platform for loved ones to mourn the loss of a family member or even a fictional character due to suicide [25,27,29]. These pages contained long, detailed posts by loved ones and words suggesting they struggled with their losses [28]. Women experiencing a loss and grieving were more likely to be Facebook subscribers, and mental health messages would be able to offer psychological support [26]. Furthermore, research shows that many individuals use Internet forums and Facebook groups to grieve losses and find emotional support [25,27]. Despite many people seeking face-to-face professional support, they preferred informal support from online platforms such as Facebook. For many, Facebook allowed bereaved people to memorialise their loved ones and feel their ongoing virtual presence [3,18]. Individuals post on Facebook about their loss and grief to commemorate the deceased loved ones, mourn, and remember their special occasions, allowing them to vent their distress in a virtual environment [30,46].

Multi-task artificial neural network models analysing Facebook posts could predict suicide risk better than a single-task model [31]. This will facilitate building tools to predict suicide risk among users correctly and has successfully dealt with crises in inpatient settings [36]. Users on Facebook can anonymously post their distress, minimal suppression of emotional expression, and prevent interpersonal communication breakdowns [33,34]. Social media, such as Facebook, provides an opportunity to talk to others and provide emotional support. There are substantial benefits of social media in suicide prevention [35]. However, Facebook needs to adhere to suicide-reporting guidelines, as harmful content is frequently seen and should prevent the glorification of suicidal deaths [37,38]. In the future, Facebook has demonstrated efficacy and cost-efficiency in recruiting people for suicide prevention activities which could be used to develop far-reaching strategies [39]. Newer technologies, such as artificial intelligence and machine learning, will play a core role in future preventive strategies, and finding the correct balance between safety and ethics will be a significant challenge [47]. Facebook, indeed, needs an algorithm to detect and prevent suicide in action and to achieve this, machine learning classifiers need to be built, and many examples need to be fed into the system [48]. Various combinations of words impact on the classifier’s confidence, and it scores the content based on previously confirmed cases of suicidal expression. The classifier scores are inserted into a random forest learning algorithm, a machine learning type specialising in numerical data [48].

Our scoping review showed both positive and negative effects of Facebook on suicidal behaviour. It provided an audience to express distress and live-stream harmful behaviour. On the other hand, Facebook allowed loved ones to mourn virtually and share their grief with others. Further, limited studies showed that Facebook could provide opportunities to prevent suicides and function as a protective agent. As a limitation, there were only a few quantitative studies to analyse, and it was challenging to reach broader conclusions. In addition, the studies that were found were heterogeneous in methodology and approach.

Further, our methodology only focused on four selected themes and a scoping approach for the review. Most data were qualitative, and establishing causal relationships between Facebook use and suicidal behaviour is complex. Creating a psychologically healthy Facebook experience will depend on the developers’ commitment and the users’ social responsibility, and further longitudinal quantitative studies are required to investigate the association between Facebook use and suicidal risk. Lastly, we did not investigate other factors influencing the use of Facebook and suicide.

5. Future Clinical Implications

Our review found numerous reports of posting suicide notes on Facebook and the live-streaming of self-harm viewed by many. In addition, people were using Facebook to mourn the loss of loved ones and newer technologies are being used to detect high-risk posts early so that interventions can be offered. Whether the suicide prevention algorithm of Facebook and other social media can effectively reduce the rate of suicides is an issue that requires further evaluation in large-scale, well-designed studies [49]. The possible association between the excessive use of social media networks and a higher risk of suicidal behaviours remains controversial and needs further investigation. As stated in previous studies, the extensive use of social media as an addictive behaviour can increase the likelihood of suicidal behaviours through interactions with specific users, social groups, or online communities [50]. This is of cardinal importance in adolescents and young adults, in which imitative suicide is a major mechanism.

One important matter that deserves close attention from clinicians, social media regulators, and policymaking authorities is the ethical and moral issues that may arise when breaching the privacy of social media users by looking into and analysing their details. This may be indeed necessary for specialists who try to help the users and prevent deaths by suicide [49].

6. Recommendations

- We recommend that future studies focus on real-world data and algorithms that provide insight into self-harm risk based on social media information. Moreover, further studies are required to shed light on the possible link between the addictive use of social media and suicidal behaviours;

- State authorities and policymakers are recommended to enforce strict data sharing regulations so that users’ personal information and privacy are not affected. Artificial intelligence methods should anonymise the necessary information and provide valuable information to therapists;

- Advertisement campaigns regarding suicide prevention on Facebook can promote the use of hotlines and mobile applications, providing dependable and practical support for people in distress;

- Facebook can also efficiently increase the general population’s awareness regarding mental health issues and educate the communities to prevent the stigmatisation of mental illnesses. This can reduce the rate of suicidal behaviours and deaths by suicide in the long term;

- An option for being under surveillance for suicide risk should be extended to all users;

- All social media platforms, including Facebook, should use techniques for users to report harmful websites and activities of other users;

- Direct and quick ways to obtain psychological support via Facebook should be available;

- Public health initiatives should target Facebook to promote awareness of psychological problems in schools, colleges, and other settings;

- Those in charge of suicide prevention and public-health outreach efforts must keep up with Facebook trends, user preferences, and relevant legal issues;

- Finally, using Facebook to raise public awareness and education about mental health issues is a sensible modern public health strategy to save lives.

7. Conclusions

Social media can detect suicidal tendencies, support those seeking help, comfort family and friends with their grief, and provide insights via timelining the users’ activities leading to their suicide. One of the limitations was the lack of quantitative studies evaluating preventative efforts on Facebook. The creators’ commitment and the users’ social responsibility will be required to create a mentally healthy Facebook environment.

Author Contributions

S.S. (Sheikh Shoiband): conceptualization, writing first draft; S.S. (Sheikh Shoiband) and T.W.A.: collecting data. All other authors have contributed to the present paper equally in writing the first draft and revising the final version. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available upon request by Authors Sheikh Shoib and Sarya Swed.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- De Berardis, D.; Martinotti, G.; Di Giannantonio, M. Editorial: Understanding the Complex Phenomenon of Suicide: From Research to Clinical Practice. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snowdon, J.; Choi, N.G. Undercounting of suicides: Where suicide data lie hidden. Glob. Public Health 2020, 15, 1894–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruder, T.D.; Hatch, G.M.; Ampanozi, G.; Thali, M.J.; Fischer, N. Suicide Announcement on Facebook. Crisis 2011, 32, 280–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, D.; Carli, V.; Iosue, M.; Javed, A.; Herrman, H. Suicide Prevention in Childhood and Adolescence: A Narrative Review of Current Knowledge on Risk and Protective Factors and Effectiveness of Interventions. Asia-Pac. Psychiatry 2021, 13, e12452. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/appy.12452 (accessed on 12 September 2022). [CrossRef]

- Simbar, M.; Golezar, S.; Alizadeh, S.H.; Hajifoghaha, M. Suicide Risk Factors in Adolescents Worldwide: A Narrative Review. J. Rafsanjan Univ. Med. Sci. 2018, 16, 1153–1168. Available online: http://journal.rums.ac.ir/article-1-3851-en.html (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Behera, C.; Kishore, S.; Kaushik, R.; Sikary, A.K.; Satapathy, S. Suicide announced on Facebook followed by uploading of a handwritten suicide note. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020, 52, 102061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venegas-Vera, A.V.; Colbert, G.B.; Lerma, E.V. Positive and negative impact of social media in the COVID-19 era. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 21, 561–564. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.d.R.; Qusar, M.S.; Islam, M.d.S. Suicide after Facebook posts–An unnoticed departure of life in Bangladesh. Emerg. Trends Drugs Addict. Health 2021, 1, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cero, I.; Witte, T.K. Assortativity of suicide-related posting on social media. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seward, A.; Harris, K.M. Offline versus online suicide-related help seeking: Changing domains, changing paradigms. J. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 72, 606–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, K.w.; Cheng, Q.; Wong, P.W.C.; Yip, P.S.F. Responses to a self-presented suicide attempt in social media: A social network analysis. Crisis: J. Crisis Interv. Suicide Prev. 2013, 34, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhang, W.; Harris, K.; Chen, Q.; Xu, X. Dying online: Live broadcasts of Chinese emerging adult suicides and crisis response behaviors. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westerlund, M. Talking suicide: Online conversations about a taboo subject. Nord. Rev. 2013, 34, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.; Cox, G.; Bailey, E.; Hetrick, S.; Rodrigues, M.; Fisher, S.; Herrman, H. Social media and suicide prevention: A systematic review. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2016, 10, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Hotman, D.; Loh, E. AI enabled suicide prediction tools: A qualitative narrative review. BMJ Health Care Inf. 2020, 27, 100175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, H.T.G.; Edge, N. “They are happier and having better lives than I am”: The impact of using Facebook on perceptions of others’ lives. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2012, 15, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, K.L.; Forest, A.L. Communicating commitment: A relationship-protection account of dyadic displays on social media. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2020, 46, 1059–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahuja, A.K.; Biesaga, K.; Sudak, D.M.; Draper, J.; Womble, A. Suicide on facebook. J Psychiatr. Pract. 2014, 20, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid Soron, T. Use of facebook for developing suicide database in Bangladesh. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2019, 39, 110–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, J.R.; Lee, W.; Shetty, H.; Broadbent, M.; Cross, S.; Hotopf, M.; Stewart, R. ‘He left me a message on Facebook’: Comparing the risk profiles of self-harming patients who leave paper suicide notes with those who leave messages on new media. BJPsych Open 2016, 2, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, G.; DeSilva, R. Social Media Applications: A Potential Avenue for Broadcasting Suicide Attempts and Self-Injurious Behavior. Cureus 2020, 12, e10759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kailasam, V.K. Can Social Media Help Mental Health Practitioners Prevent Suicides? Available online: https://www.facebook.com/notes/american- (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Majeed, M.H.; Arooj, S.; Afzal, M.Y.; Ali, A.A.; Mirza, T. Live suicide attempts on Facebook. Can we surf to save? Australas. Psychiatry 2018, 26, 671–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soron, T.R.; Islam, S.M.S. Suicide on Facebook-the tales of unnoticed departure in Bangladesh. Glob. Ment. Health 2020, 7, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeGroot, J.M.; Leith, A.P.R.I.P. Kutner: Parasocial Grief Following the Death of a Television Character. Omega 2018, 77, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feigelman, W.; McIntosh, J.; Cerel, J.; Brent, D.; Gutin, N.J. Identifying the social demographic correlates of suicide bereavement. Arch. Suicide Res. 2019, 23, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, E.; Krysinska, K.; O’Dea, B.; Robinson, J. Internet Forums for Suicide Bereavement. Crisis 2017, 38, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scourfield, J.; Evans, R.; Colombo, G.; Burrows, D.; Jacob, N.; Williams, M.; Burnap, P. Are youth suicide memorial sites on Facebook different from those for other sudden deaths? Death Stud. 2019, 44, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.; Bailey, L.; Kennedy, D. ‘We do it to keep him alive’: Bereaved individuals’ experiences of online suicide memorials and continuing bonds. Mortality 2015, 20, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilmaç, J.A. Martyrs Never Die: Virtual Immortality of Turkish Soldiers. Omega 2018, 78, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ophir, Y.; Tikochinski, R.; Asterhan, C.S.C.; Sisso, I.; Reichart, R. Deep neural networks detect suicide risk from textual facebook posts. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.; Teh, Z.; Lamblin, M.; Hill, N.T.M.; La Sala, L.; Thorn, P. Globalization of the #chatsafe guidelines: Using social media for youth suicide prevention. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2021, 15, 1409–1413. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yeo, T.E.D. “Do You Know How Much I Suffer?”: How Young People Negotiate the Tellability of Their Mental Health Disruption in Anonymous Distress Narratives on Social Media. Health Commun. 2020, 36, 1606–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teo, A.R.; Strange, W.; Bui, R.; Dobscha, S.K.; Ono, S.S. Responses to Concerning Posts on Social Media and Their Implications for Suicide Prevention Training for Military Veterans: Qualitative Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e22076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.; Rodrigues, M.; Fisher, S.; Bailey, E.; Herrman, H. Social media and suicide prevention: Findings from a stakeholder survey. Shanghai Arch. Psychiatry 2015, 27, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Haines-Delmont, A.; Chahal, G.; Bruen, A.J.; Wall, A.; Khan, C.T.; Sadashiv, R.; Fearnley, D. Testing Suicide Risk Prediction Algorithms Using Phone Measurements With Patients in Acute Mental Health Settings: Feasibility Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2020, 8, e15901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumner, S.A.; Burke, M.; Kooti, F. Adherence to suicide reporting guidelines by news shared on a social networking platform. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 16267–16272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, N.A.; Nathan, K.I. Suicide, stigma, and utilizing social media platforms to gauge public perceptions. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Torok, M.; Shand, F.; Chen, N.; McGillivray, L.; Burnett, A.; Larsen, M.E.; Mok, K. Performance, Cost-Effectiveness, and Representativeness of Facebook Recruitment to Suicide Prevention Research: Online Survey Study. JMIR Ment. Health 2020, 7, e18762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brailovskaia, J.; Margraf, J.; Teismann, T. Repetitive negative thinking mediates the relationship between addictive Facebook use and suicide-related outcomes: A longitudinal study. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Jacobs, L. “Inbox me, please”: Analysing comments on anonymous Facebook posts about depression and suicide. J. Psychol. Afr. 2019, 29, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umegaki, Y.; Higuchi, A. Personality traits and mental health of social networking service users: A cross-sectional exploratory study among Japanese undergraduates. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2022, 6, 100177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, L.D.; Whaling, K.; Rab, S.; Carrier, L.M.; Cheever, N.A. Is Facebook creating “iDisorders”? The link between clinical symptoms of psychiatric disorders and technology use, attitudes and anxiety. Comput. Human Behav. 2013, 29, 1243–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, J. Friend Challenges Facebook Over Ronnie McNutt Suicide Video. BBC News, 20 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- George, D.R.; Dellasega, C.; Whitehead, M.M.; Bordon, A. Facebook-based stress management resources for first-year medical students: A multi-method evaluation. Comput. Human Behav. 2013, 29, 559–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer, L.M.; Enck, S. Is my grief too public for you? The digitalization of grief on FacebookTM. Philos. Technol. 2018, 44, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrade, N.N.G.; Pawson, D.; Muriello, D.; Donahue, L.; Guadagno, J. Ethics and Artificial Intelligence: Suicide Prevention on Facebook. Philos. Technol. 2018, 31, 669–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Card, C. How Facebook AI Helps Suicide Prevention. Meta. 2018. Available online: https://about.fb.com/news/2018/09/inside-feed-suicide-prevention-and-ai/ (accessed on 26 January 2022).

- Celedonia, K.L.; Corrales Compagnucci, M.; Minssen, T.; Lowery Wilson, M. Legal, ethical, and wider implications of suicide risk detection systems in social media platforms. J. Law Biosci. 2021, 8, lsab021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrynikola, N.; Auad, E.; Menjivar, J.; Miranda, R. Does social media use confer suicide risk? A systematic review of the evidence. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2021, 3, 100094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).