Abstract

Multiple myeloma (MM) is still considered an incurable hematologic cancer and, in the last decades, the treatment goal has been to obtain a long-lasting disease control. However, the recent availability of new effective drugs has led to unprecedented high-quality responses and prolonged progression-free survival and overall survival. The improvement of response rates has prompted the development of new, very sensitive methods to measure residual disease, even when monoclonal components become undetectable in patients’ serum and urine. Several scientific efforts have been made to develop reliable and validated techniques to measure minimal residual disease (MRD), both within and outside the bone marrow. With the newest multidrug combinations, a good proportion of MM patients can achieve MRD negativity. Long-lasting MRD negativity may prove to be a marker of “operational cure”, although the follow-up of the currently ongoing studies is still too short to draw conclusions. In this article, we focus on results obtained with new-generation multidrug combinations in the treatment of high-risk smoldering MM and newly diagnosed MM, including the potential role of MRD and MRD-driven treatment strategies in clinical trials, in order to optimize and individualize treatment.

1. Introduction

Multiple Myeloma (MM) is a hematologic malignancy caused by the outgrowth of monoclonal plasma cells that leads to end-organ damage [1]. In 2018, MM accounted for 1.2% of all cancer diagnoses and 1.6% of all cancer deaths in Europe [2]. The median overall survival (OS) of newly diagnosed (ND) MM patients improved from 3.9 years for patients diagnosed between 2004 and 2007 to 6.3 years for those diagnosed between 2008 and 2012 to a median OS that is not yet reached in patients diagnosed after 2012 [3]. The introduction of new drug classes like proteasome inhibitors (PIs), immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs), and, more recently, monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) has been the main determinant of the observed OS improvement, together with an improved supportive care. Nevertheless, the main cause of death in MM patients is still the development of drug-resistant disease [4]. Although obtaining deep responses is a universally recognized predictive factor of good outcome [5], long-term disease control, rather than disease eradication, is still the aim of MM treatment in current clinical practice, since the available data show that even patients achieving minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity relapse. This confirms the so-far incurable nature of MM. Recent data, comparing the survival of young MM patients treated between 2005 and 2015 to that of young patients affected by curable hematologic diseases (e.g., diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and Hodgkin Lymphoma (HL)) [6] and to that of the general population showed that MM patients have a 20-fold excess mortality compared to the general population, while DLBCL and HL have a non-significant excess mortality [6].

However, more recent results from clinical trials exploring novel three-drug and four-drug combinations showed unprecedented rates of prolonged and deep responses [7,8,9,10,11], with acceptable safety profiles even in elderly patients, thus increasing the likelihood not only to achieve disease control, but potentially cure, at least in a subset of patients. To design a potentially curative strategy, we have to focus on the first stages of the disease (smoldering MM (SMM), newly diagnosed MM (NDMM)), when the patient is treatment-naïve and disease genomic complexity is lower, as compared to the advanced relapsed/refractory setting.

In this review, we provide a summary of the new techniques used to detect residual disease at high sensitivity and of the results obtained in SMM and NDMM with new-generation combinations. We also explore how we can exploit these data in the future, towards a potential cure of MM.

2. Evolution of Response Criteria and MRD Techniques

To enable disease eradication strategies, it is mandatory to have sensitive methods to detect small amounts of residual disease after treatment. MM response criteria evolved together with therapies. While before the introduction of novel agents, the rates of complete remission (CR) were very low (2% after 3 cycles of vincristine–doxorubicin–dexamethasone [12]), with novel combinations CR can now be obtained in >60% of patients [9]. Conventionally, MM response is evaluated measuring M-protein levels in the blood and urine, but it is now clear that even when M-protein disappears, residual disease can still be present [13]. The Spanish group showed that, among patients with a conventionally defined CR, there was a significant difference in outcome between MRD-negative and MRD-positive patients (median progression-free survival (PFS) 63 vs. 27 months, p < 0.001; median OS not reached vs. 59 months, p < 0.001). Interestingly, the outcome of patients with MRD-positive CR was similar to the outcome of those achieving only a partial response (PR), thus suggesting that the advantage of reaching CR over PR relies on the MRD-negative status. Recently, response criteria have been updated, introducing a universal definition of MRD beyond CR (for a detailed definition of the updated response criteria, please refer to Kumar et al., 2016) [14,15,16,17].

Two techniques have been developed and validated to detect MRD into the bone marrow: multiparameter flow cytometry (MFC) and next-generation sequencing (NGS).

MFC detects and quantifies tumor plasma cells using cell surface and cytoplasmic markers. Neoplastic plasma cells are characterized by the aberrant expression of molecules like CD19, CD20, CD27, CD28, CD33, CD38, CD45, CD56, CD117, and surface membrane immunoglobulin [18]. The first attempts to detect MRD by MFC had a maximum sensitivity of 10−4–10−5. The optimization of the MFC assay using two 8-color tubes, a bulk-lysis procedure, the acquisition of ≥107 cells/sample, and the automatic plasma cell gating through a software tool led to reproducible results and enhanced the maximum sensitivity to 10−5–10−6 (next-generation flow, NGF) [19,20]. Using NGF, Flores-Montero and colleagues demonstrated that 25% of patients who were classified as MRD-negative by second-generation MFC were indeed MRD-positive by NGF [20]. Moreover, NGF negativity predicted a significantly longer PFS than second-generation MFC negativity among CR patients (p = 0.02) [20].

NGS technique was mainly developed by Adaptive Biotechnologies (Seattle, WA, USA) by producing and validating ClonoSEQ® Assay, which has recently obtained, by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the authorization as standardized technique for the disease evaluation in MM patients [21]. In this test, DNA from the immunoglobulin genes is amplified and sequenced using baseline bone marrow sample and identical sequences detected in more than 5% of the reads are identified as clonal gene rearrangements. These rearrangements are then searched in follow-up samples to identify MRD [22,23]. NGS reaches maximum sensitivity up to 10−6 [21].

Ongoing clinical trials are evaluating NGS vs. NGF/MFC and their correlation [24], and will help understand if the two techniques can be considered equivalent in identifying MRD negativity at a specific cut-off. Each technique has its own advantages and drawbacks (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of next-generation sequencing (NGS) and next-generation flow (NGF) for the detection of minimal residual disease (MRD) in multiple myeloma.

The maximum sensitivity reached is a key point, especially in a curative perspective. Each log depletion in MRD levels predicts a 1-year median OS advantage (5.9 years at 10−2–10−3, 6.8 years at 10−3–10−4, and ≥7.5 years at 10−4), suggesting that MRD levels at the highest sensitivity should be pursued [25]. Several reports suggested that once MRD-negative statuses are reached with a high sensitivity technique, patient prognoses are similar independently from the treatment that induced MRD negativity [26,27]. This observation also seems to apply to patients with adverse baseline prognostic factors (e.g., high-risk cytogenetics or elevated Revised International Staging System (R-ISS) stage), among whom MRD-negative patients at a sensitivity of 10−5–10−6 [26,28], but not at a sensitivity of 10−4 [29], showed similar clinical outcomes compared to standard-risk patients. Nevertheless, reaching MRD negativity in high-risk patients may be harder [30], and intensive regimens are likely needed in this patient population [8,9].

Even when evaluating MRD at a sensitivity of 10−6, there are still patients that can relapse. Relapses can also be caused by extramedullary disease [31]. Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) is currently considered the standard of care to assess residual disease outside the bone marrow [32,33]. The predictive role of post-treatment PET/CT has been demonstrated by different studies [34,35,36] and, in a head-to-head comparison [34], the normalization of PET/CT outperformed that of conventional magnetic resonance imaging after therapy for the prediction of PFS and OS. Recently, Zamagni et al. presented data on the standardization of PET/CT to define criteria for MRD negativity using the 5-point Deauville score. PET/CT imaging was a reliable predictor of outcomes regardless of treatment. The achievement of a Deauville score ≤3 was the predictor of a longer time to disease progression and overall survival (OS) and, consequently, a potential standardized definition of PET/CT negativity [37].

MRD assessed by PET/CT and bone marrow techniques synergistically predict patient outcome, with the best PFS detected in patients who were MRD-negative both within and outside the bone marrow [38]; hence the definition of Imaging MRD negativity.

Both the NGS and the NGF-plus-Imaging approaches are needed for the response evaluation in the setting of a curative strategy. Nevertheless, from a practical perspective, it should be determined if all these techniques are necessary for all patients, or if it is possible to develop an algorithm to define how to proceed. To do this, we need to answer open questions such as: In which patients should we perform MRD (CR, stringent CR (sCR) very good partial response (VGPR))? What is the proportion of patients who are still PET-positive despite being MRD-negative in the bone marrow with a high cut-off level (e.g., 10−6)? Vice versa, how many PET-positive patients are MRD-negative? Who are the patients that show discrepancies between the two evaluations? Ongoing studies including both BM and PET/CT evaluation at specific time points will help in drawing conclusions [37].

In the future, liquid biopsy approaches that use peripheral blood samples could potentially overcome the need to assess MRD both in the bone marrow and by imaging. However, these techniques are still at early developmental stages [39].

Besides achieving MRD negativity, a more important factor is maintaining it [40]: here comes the definition of “sustained MRD negativity” by the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG), which uses the 1-year cut-off. An effort should be made to define the optimal duration of MRD negativity to reach an “operational cure”; this still remains an unanswered question, with a potentially great clinical relevance. For instance, in the chronic myeloid leukemia field, a sustained major molecular response lasting at least 2 years is usually required to be a candidate for treatment discontinuation [41], and longer deep molecular response durations prior to discontinuation are associated with the increasing probability of maintaining a major molecular response after discontinuation [42]. Little data are available in MM. Using MFC to monitor MM patients after induction and at different time points post-autologous stem-cell transplantation (ASCT), Gu and colleagues showed that, among patients achieving MRD negativity after the post-induction time point, MRD reappearance can happen 18–24 months after ASCT, thus suggesting that long-term confirmation of sustained MRD negativity may be necessary [43].

3. Treatment of High-Risk SMM

SMM [44] is an asymptomatic plasma cell neoplasm harboring a variable risk of progression to MM. Several scores have been proposed to assess SMM risk of progression to symptomatic MM (Table 2) [45,46].

Table 2.

Smoldering multiple myeloma: risk stratification systems.

The 2/20/20 model was the most recently proposed; its name comes from the resulting cut-offs of M-protein, bone marrow plasma cells (BMPC), and free light chains (FLC). M-protein >2g/dL (hazard ratio (HR) 1.56, p = 0.01; BMPC % >20% (HR 2.28, p < 0.0001), and FLC ratio (FLCr) >20 (HR 2.13, p < 0.0001)) independently predicted shorter time to progression (TTP) in multivariate analysis. Three risk groups were identified: Low risk (none of the risk factors), intermediate risk (1 risk factor), and high risk (≥2 risk factors), with a median TTP of 110, 68, and 29 months, respectively (p < 0.0001) [45]. The high-risk group consisted of 36% of the analyzed cohort of SMM.

A retrospective multicenter study by the IMWG validated the 2/20/20 model; furthermore, incorporating the cytogenetic abnormalities detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH; presence vs. absence of t(4,14), t(14,16), 1q gain, and/or del13), they identified four risk categories with a 2-year progression risk of 3.7% (low risk), 25% (low–intermediate), 49% (intermediate–high), and 72% (high) [49].

The current standard of care for SMM is periodical monitoring, with a suggested frequency based on patient risk to identify the possible evolution to symptomatic MM in due time and avoid severe organ damage. While this strategy suits well low-risk SMM patients who are unlikely to progress to MM, it may be questionable in high-risk SMM. In this setting, open questions are: (1) Can these patients benefit from an early therapy aiming at delaying the very likely evolution to MM? (2) Is there a possibility that early treatment may actually cure the disease? The latter hypothesis is based upon the very good outcome observed in patients with symptomatic MM and good prognosis [50], as well as upon a lower genomic complexity during the early phases of the disease that, together with a lower tumor burden, might suggest a higher possibility of cure [51]. Moreover, better treatment feasibility is expected in asymptomatic patients in good conditions. This rationale led to the design of clinical trials for the treatment of high-risk SMM (Table 3).

Table 3.

Smoldering multiple myeloma: Selected clinical trials.

In the phase III randomized QuiRedex study, 119 high-risk SMM patients [52] received lenalidomide–dexamethasone (Rd) vs. observation. After a median follow-up of 75 months, the median TTP was not reached in the Rd group (n = 57) vs. 23 months in the observation group (n = 62, HR 0.24, p < 0.0001). An advantage in OS in the Rd arm was also detected (HR 0.43, p = 0.024). Interestingly, survival was similar in the two groups for patients who had previously received subsequent lines of therapy at the progression to active disease (HR 1.34, p = 0.50). The Rd combination showed acceptable levels of toxicity: Grade ≥3 adverse events (AEs) were infection (6%), asthenia (6%), neutropenia (5%), and skin rash (3%). During treatment, two patients treated with lenalidomide died of infection. A higher rate of second primary malignancies (SPMs) was detected in the Rd group (10%) vs. the observation group (2%). Of note, progression was defined by classical CRAB criteria (hyperCalcemia, Renal failure, Anemia, and Bone lesions) and advanced imaging techniques at screening were not performed, thus suggesting that the study also included patients who would currently be classified as having symptomatic MM.

The efficacy of lenalidomide was also shown in the phase II/III E3A06 study, in which lenalidomide was compared to observation in SMM [62]. After a median follow-up of 35 months in phase III of the trial, the overall response rate (ORR) was 50% in the R group and 0% in the observational group. One-year, 2-year, and 3-year PFS were respectively 98%, 93%, and 91% in the R group, favorably comparing with respectively 89%, 76%, and 66% in the observational arm (HR 0.28, p = 0.002). Among lenalidomide-treated patients, grade 3/4 non-hematologic toxicities occurred in 28% of the phase III patients, with hypertension and infections being most common toxicities. However, no difference in scores regarding the quality of life was noted between the lenalidomide and the observational groups. In this trial, SPMs were detected in 11.4% of lenalidomide-treated patients vs. 3.4% of patients in the observational group.

In this setting, another attractive drug is the second-generation PI ixazomib, which is characterized by a convenient oral administration and shows good safety results. In a phase I study, ixazomib associated with dexamethasone showed good tolerability and high response rate (ORR 64%, PR 57%, and VGPR 14%) [55]. A phase II study exploring the entirely oral triplet ixazomib–lenalidomide–dexamethasone confirmed the good tolerability profile and efficacy of this combination, with a 58% of ≥VGPR (CR 19%, VGPR 34%) [58].

MAbs were also evaluated for the treatment of SMM. The anti-SLAMF7 elotuzumab as single agent showed a low response rate (ORR 10%, minimal response (MR) 29%), with a 2-year PFS of 69%, while first data of the combination with Rd showed a ≥VGPR rate of 43% [56,57].

The phase II CENTAURUS trial evaluated daratumumab alone in 123 patients with three different dose schedules and durations (long intense, intermediate, short intense; Table 3) [60]. At a median follow-up of 25.9 months, ≥VGPR rates were higher in the long intense and intermediate arms compared to the short intense arm (29%, 25%, and 18%, respectively). The 24-month PFS rates were 90%, 82%, and 75% in the three arms. Grade ≥3 AEs occurred in 44% (long intense), 27% (intermediate), and 15% (short intense) of patients. The most frequent grade 3–4 AEs were hypertension and hyperglycemia. The subcutaneous formulation of daratumumab is also being explored in a randomized phase III trial against active monitoring in this setting (NCT03301220). Another anti-CD38 mAb, isatuximab, is under evaluation (NCT02960555).

More intense regimens using three- or four-drug combinations ±ASCT were used in the high-risk SMM setting, aiming at the eradication of MM.

In a small cohort of 12 high-risk SMM patients, Korde and colleagues demonstrated that carfilzomib–lenalidomide–dexamethasone (KRd) induced deep responses (≥CR 100%) and MRD negativity (92% by MFC); after a median follow-up of 15.9 months, none of the patients progressed to MM [53]. Interestingly, the same regimen administered in the NDMM setting produced a lower rate of deep responses (≥CR 56%), suggesting that high-risk SMM patients can be more sensitive to treatment [53].

In the single-arm, phase II GEM-CESAR trial, patients received KRd as induction, ASCT, KRd as consolidation and maintenance therapy with Rd. After a median follow-up of 32 months (8–128), the 30-month PFS was 93% and each phase of therapy was associated with increasing rates of MRD negativity evaluated by NGF (sensitivity 3 × 10−6; 31% after induction, 56% after ASCT, 63% after consolidation). During induction, the most common G≥3 AEs were infections (18%), skin rash (9%), neutropenia (6%), and thrombocytopenia (11%). Cardiac AEs were rare: 1 grade 1 atrial fibrillation, 1 cardiac failure secondary to respiratory infection, and 3 cases of hypertension during consolidation [54].

Another ongoing randomized phase II study (HO147SMM) is comparing KRd to Rd, but no data are available yet.

The addition of the anti-CD38 mAb daratumumab to KRd induction and consolidation is being evaluated in the ASCENT study (NCT03289299), which is now recruiting patients. A randomized comparison of daratumumab–Rd vs. Rd in the context of high-risk SMM is also ongoing (NCT03937635).

4. Treatment of Symptomatic NDMM

The first efforts aiming at a curative approach in NDMM were done by the University of Arkansas group in the 1990s, developing a program called Total Therapy (TT) using a series of non-cross-resistant induction regimens, 2 cycles of high-dose chemotherapy, followed by ASCT and maintenance treatment [63]. Toxicity concerns and the unavailability of novel agents hindered the success of this approach, although the long-term follow-up of treated patients (median 21 years) showed a plateau in the survival curves with an estimated cure rate of 9% based on PFS data and of 18% based on the duration of CR [64].

Currently, general treatment approaches in NDMM patients are tailored upon their eligibility for high-dose therapy (HDT) and ASCT [65].

4.1. ASCT-Eligible Patients

The current therapeutic approach includes sequential induction therapy and ASCT ± consolidation, followed by maintenance. Induction is typically administered for 4–6 cycles prior to ASCT [66]. The introduction of the PI bortezomib increased the response rate compared to classical chemotherapy [67], and is now a backbone of treatment. The addition of a third drug to the bortezomib–dexamethasone (Vd) combination (i.e., thalidomide [VTd], cyclophosphamide [VCd], lenalidomide [VRd], doxorubicin [PAD]) increased the depth of response [68]. In a head-to-head comparison, VTd was superior to VCd as induction prior to HDT–ASCT in terms of ORR (92% vs. 83%) and ≥VGPR rate (66% vs. 56%) [69], demonstrating that even with first-generation novel agents, the combination of a PI and an IMiD was beneficial.

In phase III trials, VRd induction was tested in the PETHEMA and Intergroupe Francophone du Myélome (IFM) 2009 studies (Table 4).

Table 4.

Newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: selected clinical trials enrolling transplant-eligible patients.

No randomized trial directly compared VRd vs. VTd induction, although a recent integrated analysis of French and Spanish trials was performed (VRd: PETHEMA, GEM 2012, and IFM 2009; VTd: GEM2005 and IFM 2013-04) [79]. In the Spanish studies, after 6 cycles of induction, the ≥VGPR rate was 66.3% vs. 51.2% (p = 0.003) in VRd vs. VTd groups. In the French studies, after 4 cycles of induction, the ≥VGPR rate was similar between VRd vs. VTd groups (57.1% vs. 56.5%). The safety profile of VRd was better than that of VTd in both Spanish and French studies, with a lower rate of polyneuropathy (PNP).

High-dose melphalan (200 mg/m2, MEL200) followed by ASCT is currently a standard approach in transplant-eligible patients, due to the longer PFS showed in randomized clinical studies comparing ASCT vs. novel agent-based therapy [50,74,80,81], but the role of double vs. single ASCT is still an open issue. The EMN02/HO95 phase III trial showed a benefit in the double ASCT arm in terms of PFS (3-year PFS 73% vs. 64% in double vs. single ASCT); this effect was particularly evident in the high cytogenetic risk group, where an OS benefit was also noticed [82]. Similarly, in a meta-analysis including three phase III trials, after a median follow-up of 10 years, double ASCT was significantly better than single ASCT in terms of PFS and OS. Consistent with the EMN02/HO95 data, the benefit was particularly evident in the high-risk group [82], suggesting that, in this patient population, a double ASCT is advisable. Nevertheless, the STAMINA trial did not show any difference in PFS or OS of patients receiving double vs. single ASCT. It is always difficult to perform comparisons between different trials, but the better and prolonged induction (VRD) used in the majority of the patients enrolled in the STAMINA study (whereas 3-4 cycles of VCD were used in the EMN02 study) and the lower compliance to the second ASCT procedure reported in the same study can partially explain the different results [83].

Many trials explored consolidation regimens with the rationale to deepen patient response. In the most recently published PETHEMA study, VRd induction, ASCT, and VRd consolidation produced a ≥CR rate of 58% (46% sCR, 12% CR) [75]. These data are consistent with the IFM phase II and phase III studies using VRd consolidation. In the IFM2009 study, VRd consolidation after VRd induction and ASCT showed a similar trend, with the ≥CR rate increasing from 27% during the induction phase, to 47% after ASCT to 50% after consolidation (sCR 40%, CR 10%) (Table 4) [70]. Response deepened over time, as well as MRD negativity. In the PETHEMA study, MRD by NGF with a cut-off sensitivity of 3 × 10−6 progressively increased from 34.5% post-induction to 53.4 % post-ASCT, to 58% after consolidation [75]. The phase III STAMINA and EMN02/HO95 trials were designed to evaluate the role of consolidation vs. no consolidation in a randomized fashion. In the STAMINA trial, the 38-month probability for PFS was respectively 58% with single ASCT + VRd consolidation, 58% with tandem ASCT and no consolidation, and 53% with single ASCT and no consolidation, with no statistical differences [83]. In the EMN02/HO95 study, VRd consolidation after ASCT/bortezomib–melphalan–prednisone (VMP) showed a PFS advantage, with a 5-year PFS of 48% in the VRd consolidation arm and 41% in the no consolidation arm [83,84].

In transplant-eligible patients, maintenance therapy is the standard approach after ASCT ± consolidation. A meta-analysis of three phase III trials randomizing patients to lenalidomide vs. observation/placebo showed a significant benefit in the lenalidomide arm in terms of PFS (median, 53 months vs. 24 months, HR 0.48; p = 0.001) and OS (not reached (NR) vs. 86 months, HR 0.75; p = 0.001) [85]. More recently, the Myeloma XI study confirmed the advantage of lenalidomide maintenance vs. observation after ASCT (median PFS 57 vs. 30 months, HR 0.48, p < 0.0001; 3-year OS 87.5% vs. 80.2%, HR 0.69, p = 0.01) [86]. Maintenance with lenalidomide can also further deepen the response, with 27–30% of MRD-positive patients becoming MRD-negative during treatment [87]. Besides its efficacy, the tolerability of continuous lenalidomide maintenance is an important issue. In the meta-analysis, about 30% of subjects receiving lenalidomide experienced a treatment-related AE that led to discontinuation. Moreover, a higher incidence of SPMs in the lenalidomide arm was reported, although it was outweighed by the advantage of a better disease control [85]. Although the optimal duration is currently considered to be until progressive disease, the median actual duration is generally around 2–3 years [85], with retrospective data showing a benefit in patients continuing the drug for at least 2 years [88,89]. However, there are currently no randomized prospective data showing evidence that lenalidomide until progressive disease is better than its administration for a prolonged but fixed duration [74].

Maintenance with lenalidomide alone showed conflicting results in high-risk patients [85,86], and the addition of PIs was suggested to be beneficial [90]. In a phase III trial [91], long-term treatment with bortezomib showed to abrogate the negative effect of deletion 17p [92,93,94]. Moreover, in a randomized study, the administration of the second-generation PI ixazomib as post-ASCT maintenance improved PFS compared to placebo and showed a similar effectiveness for both standard- and high-risk patients [95].

The high rate of deep responses (CR and MRD negativity) obtained after this sequential first-line treatment could further be improved by incorporating the second-generation irreversible PI carfilzomib or adding a fourth drug class, such as the anti-CD38 mAbs.

The incorporation of carfilzomib into first-line treatment was tested in several trials (Table 4) [53,96,97,98]. In the randomized phase II FORTE trial, carfilzomib was combined either with lenalidomide (KRd) or cyclophosphamide (KCd) with or without ASCT (arm A KCd–ASCT–KCd; arm B KRd–ASCT–KRd; arm C KRd-12 cycles), followed by maintenance with KR or R. After a median follow-up of 26 months, the post-consolidation response rates and MRD negativity were significantly higher in the two KRd arms (B and C) than in the KCd arm (A): ≥VGPR rate was 74% (arm A), 87% (arm B), and 87% (arm C), and the ≥CR rate 38% (arm A), 50% (arm B), and 52% (arm C). The MRD negativity rate by MFC 10−5 after consolidation was respectively 41% (arm A), 58% (arm B), and 54% (arm C) [99]. The main non-hematologic grade ≥3 AEs were hypertension (8% KRd-12 vs. 3% KRd–ASCT and KCd–ASCT), cardiac AEs (2% KRd-12 vs. 3% KRd–ASCT vs. 3% KCd–ASCT), infections (13% KRd-12 vs. 10% KRd–ASCT vs. 9% KCd–ASCT), and hepatic AEs (10% KRd-12 vs. 8% KRd–ASCT vs. 1% KCd–ASCT) [99].

Despite similar MRD negativity rates, a lower number of early relapsing patients was noted in the KRd–ASCT arm than in the KRd-12 arm. This was observed in intermediate + high-risk patients, but not in standard-risk patients, suggesting that, despite the use of second-generation PIs upfront, ASCT could still play a role in this patient population [9].

The addition of an anti-CD38 antibody to triplet regimens has been explored in several trials as well. In the phase III trial CASSIOPEIA, daratumumab–VTd (Dara–VTd) induction-ASCT–Dara–VTd was superior to VTd-ASCT-VTd in terms of response rate after consolidation, with ≥VGPR rate of 83% vs. 78%, CR rate of 10% vs. 6%, and sCR rate of 28.9% vs. 20.3%. MRD negativity (10−5) after consolidation was reached in 64% vs. 44% of patients in the Dara–VTd vs. VTd arms; PFS was significantly improved in the Dara–VTd group, as compared with the control group (HR 0.47, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.33–0.67, p < 0.0001) [77].

The phase II GRIFFIN study compared Dara–VRd to VRd alone (Table 4). Dara–VRd improved the sCR rate by end of consolidation (42.4% vs. 32.0%). Overall, post-consolidation response was better in the Dara–VRd arm (≥VGPR 91%, ≥CR 52%, of which 59% MRD-negative) compared to the VRd arm (≥VGPR 73%, ≥CR 42%, of which 24% MRD-negative); MRD negativity was achieved in 44% of patients in the Dara–VRd arm after consolidation (10−5 threshold by NGS) [76].

A phase Ib study evaluated the addition of daratumumab to carfilzomib-based induction (Dara–KRd). Serious AEs occurred in 46% of patients. The most common grade 3–4 AEs were lymphopenia (50%) and neutropenia (23%); 1 cardiac grade 3 AE was observed (congestive heart failure). In 22 treated patients, ORR was 100% (CR 5%, ≥VGPR 86) [11].

Similarly, the addition of isatuximab to KRd is being investigated in the phase II GMMG-CONCEPT study. In the safety run-in phase (10 patients), the overall safety profile was consistent with those previously reported with KRd and isatuximab. Non-hematologic grade ≥3 AEs were treatment-unrelated cerebral vascular disorder (2 patients), self-limiting ventricular tachycardia (1), and diarrhea (1). Three patients experienced a grade 2 infusion-related reaction (IRR) during the first infusion of isatuximab [100].

Quadruplet regimens not including mAbs may allow to achieve deep responses in the majority of patients, preserving the opportunity to use mAbs after induction ± ASCT in patients not achieving MRD negativity. Bortezomib–lenalidomide–cyclophosphamide–dexamethasone (VRCd) produced a ≥VGPR rate of 33% after 4 induction cycles [71], while carfilzomib–lenalidomide–cyclophosphamide–dexamethasone (KRCd) produced a ≥VGPR rate of 82% (MRD negativity 55% at 10−4–10−5 sensitivity by flow cytometry) after a median of 4 induction cycles (range 1–12) in transplant-eligible patients [72].

In a small group of patients, the addition of the second-generation oral PI ixazomib to Rd (Ixa–Rd) during induction followed by ASCT or by ixazomib maintenance induced a good response, with 63% of patients achieving ≥VGPR and 12% MRD negativity. However, responses were not as deep as those reached in patients treated with upfront daratumumab or carfilzomib, making Ixa–Rd less appealing from a curative perspective [78].

4.2. ASCT-Ineligible Patients

ASCT-ineligible patients are a heterogeneous population. Scores predicting mortality and the risk of treatment toxicity in elderly patients have been assessed. Evidence from clinical trials [101] suggested that frailty-adapted therapies should be applied and that mainly fit patients can benefit from strategies aiming at the deepest possible response, due to higher toxicities with similar therapies in intermediate–fit/frail patients that in the end hamper the effectiveness of treatment itself [102,103].

The standard first-line treatment schemes for elderly patients are VMP, Rd, and VRd. In the phase III VISTA trial, VMP was superior to melphalan-prednisone (MP) in terms of CR rate, PFS, and OS (median 56 months vs. 43 months) [104,105].

Continuous Rd significantly increased PFS and OS compared to MPT and also prolonged PFS (but not OS) compared to Rd18 (median PFS 26 months for Rd vs. 21 months for Rd18 and 21.9 months for MPT; 4-year estimated OS 59% for Rd vs. 56% for Rd18 and 51% for MPT). Rd was also generally better tolerated than MPT [106]. In a phase III clinical trial specifically designed for intermediate–fit patients, according to the IMWG frailty score, continuous Rd was compared to Rd induction for 9 cycles followed by R maintenance alone at lower doses: PFS was superimposable, with a better tolerability with Rd–R [107].

VRd was also prospectively compared to Rd in the SWOGS0777 trial (Table 5), which, however, was not restricted to elderly patients (median age 63 years) [108]. The addition of bortezomib to Rd resulted in significantly improved PFS (43 months vs. 30 months in the Rd group; p = 0.0018) and OS (75 months vs. 64 months in the Rd group; p = 0.025). Regarding safety, the VRd combination showed higher rates of grade ≥3 AEs (82 vs. 75%), neurological toxicities (33% vs. 11%), and discontinuation (23% vs. 10%). The high neurological toxicity could be due to the two-weekly intravenous infusion of bortezomib used in this trial. In a small phase II study [109], a modified VRd, including lower lenalidomide doses (15 mg) and weekly subcutaneous bortezomib (“VRd lite”), produced a median PFS of 35.1 months and fewer toxic effects.

Table 5.

Newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: selected clinical trials enrolling transplant-ineligible patients.

Studies exploring the upfront use of anti-CD38 mAbs in transplant-ineligible patients showed deep responses also in this setting. In the ALCYONE trial, the quadruplet daratumumab–VMP (Dara–VMP) was compared to VMP showing a clear advantage in PFS (HR 0.50, 95% CI 0.38–0.65, p < 0.001) [27]. At least CR rates were 42 vs. 24% and MRD negativity rates by NGS were 22.3% vs. 6.2%, respectively. Safety issues mostly consisted of IRRs (overall 27%, grade ≥3 5%) and a high incidence of infections (grade ≥3 pneumonia 11% vs. 4% in the Dara–VMP vs. VMP arms).

Similarly, in the phase III randomized MAIA study, Dara–Rd significantly prolonged PFS as compared to Rd (HR 0.56, 95% CI 0.43–0.73, p < 0.001), with ≥CR rates of 47% vs. 24% and MRD negativity in 24% vs. 7% patients, respectively. The safety profile was similar in the two arms, but the daratumumab group experienced a higher incidence of neutropenia and infections (including pneumonia) than the Rd group. As in the ALCYONE study, IRRs were reported in the daratumumab arm (overall 40%, mostly of grades 1–2 with an incidence of grade ≥3 IRRs of 2.7%) [110].

An ongoing phase I study is investigating isatuximab, in combination with VRd (Isa–VRd): the first report on 22 patients showed good tolerability, with 46% of grade ≥3 AEs, mostly hematologic. Besides, response rates are promising, with MRD negativity rates (10−6) by NGS of 33% and by NGF 18% [111].

The good results from the upfront use of second-generation PIs in the transplant-eligible setting encouraged its exploration in several clinical trials for the treatment of elderly patients. Carfilzomib associated with melphalan and prednisone (KMP) showed promising results in a phase I/II study, with 90% ORR and 58% ≥VGPR rates and about 8% of grade ≥3 cardiovascular AEs [112]. However, in the phase III CLARION study, KMP failed to outperform VMP in terms of PFS, OS and MRD negativity rates [113]. The safety profile was different between the two arms, with KMP inducing more acute renal failure (any grade 13.9% vs. 6.2%), more cardiac failure (any grade 10.8% vs. 4.3%), and less peripheral neuropathy (grade ≥2 2.5% vs. 35.1%) than VMP.

The association of carfilzomib with cyclophosphamide dexamethasone (KCd) was evaluated in two phase I/II studies, the first adopting the once-weekly carfilzomib schedule and the second the twice-weekly schedule [114,115]. Both trials demonstrated a high efficacy profile (median PFS 35.7 and 35.5 months, respectively; 3-year OS: 72% and 75%) with acceptable toxicity. Overall toxicities mainly occurred during the induction phase and the incidence of non-hematologic AEs was similar to that observed with the KMP combination. KCd showed a lower myelotoxicity than KMP and VMP. Of note, few AEs emerged during maintenance. The once- and twice-weekly schedules were compared in a meta-analysis, with no significant differences in terms of efficacy and toxicities, and with a benefit also observed in high-risk patients [116].

5. Future Perspectives

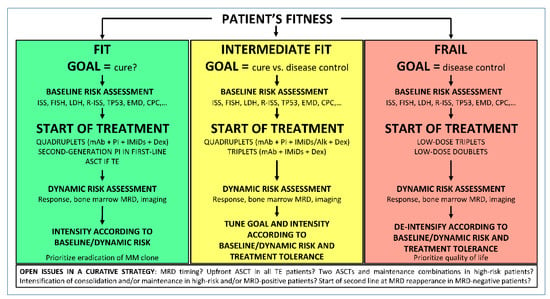

Patient fitness is one of the first factors to consider when planning the treatment strategy. Despite the manageable profile of some effective combinations, frail patients can unlikely tolerate full-dose combinations that may induce high MRD negativity. In these patients, disease control rather than cure may be the more realistically achievable goal. Nevertheless, disease control lasting for a few years, even without achieving CR or MRD negativity, could allow very elderly patients to have the same survival of age-matched healthy subjects, considering their actual life expectancy. On the other hand, in fit patients, the outcome-limiting factor is usually disease progression, and a curative approach aiming at sustained MRD negativity could be pursued. This approach should incorporate baseline risk evaluation and dynamic risk evaluation (MRD achievement and duration) during treatment (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proposed algorithm to set treatment goal in NDMM patients. ISS, international staging system; FISH, fluorescence in-situ hybridization; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; R-ISS, revised ISS; EMD, extramedullary disease; CPC, circulating plasma cells; mAb, monoclonal antibody; PI, proteasome inhibitor; IMiDs, immunomodulatory drugs; ASCT, autologous stem cell transplantation; TE, transplant eligible; MRD, minimal residual disease.

Baseline risk factors such as International Staging System (ISS), cytogenetics, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels [117], extramedullary disease [118], circulating plasma cells [119], TP53 mutations [94], and many others can help define our therapeutic strategy. For instance, the use of double ASCT and long-term treatment with a PI plus IMiDs maintenance could be beneficial in the presence of high-risk cytogenetics [92]. The dynamic evaluation of patient risk after the start of treatment can also help tune treatment intensity. Many MRD-driven therapeutic choices are under investigation in clinical trials. One possibility is to evaluate treatment escalation in patients who do not achieve MRD negativity at a pre-specified time point. In particular, this could be the approach for high-risk aggressive MM, mirroring a strategy such as the one used for acute leukemia, where achieving MRD is the goal to achieve cure. Another possibility is to evaluate treatment withholding in patients with sustained MRD negativity. This could be the option with standard-risk disease, where the disease behavior is more similar to that of chronic leukemias. In MRD-negative patients, if a reappearance of MRD is detected, restarting prior therapy if previously interrupted, or starting a different second-line therapy before the development of an overt relapse, can also be explored. Of note, the deferral of treatment is currently recommended, even at the reappearance of a monoclonal component (biochemical relapse), if the increase of the monoclonal component is slow [120]. Treating the reappearance of MRD might be a further step for prolonged disease control but its usefulness should be demonstrated in well-designed trials.

Before using MRD in the treatment of MM, several questions need to be answered. The first question is in which patients we should test MRD (in CR or sCR patients only, or in VGPR patients). The rationale to test MRD in VGPR patients is that, due to the long half-life of serum immunoglobulin (~1 month), the complete clearance of monoclonal component could take months until all the cells producing it have been eradicated, especially in IgG cases [121]. In these cases, VGPR patients who are MRD-negative in the bone marrow achieve CR in the months following MRD testing. However, MM is a spatially heterogeneous disease and residual plasma cells in extramedullary sites can produce the monoclonal component in VGPR cases in the presence of MRD negativity in the bone marrow. If this is the case, MRD should probably be measured at sCR and the confirmation of bone marrow MRD negativity with imaging techniques should be performed. In the context of a MRD-driven therapy, it is also tricky to evaluate (a) the impact and the likelihood of “false negative” or “false positive” MRD results; (b) the right time point; (c) the reasonably achievable cut-off at a specific time point. For instance, in the transplant-eligible setting, the post-induction time point could be used to investigate different durations and/or intensifications of induction regimens, and to understand whether or not intensification with transplant is necessary. It is possible that, after different treatments, different cut-offs can be achievable. As an example, a 10−5 negativity can be the reasonable goal after induction, but with prolonged intensification (transplant or further consolidation), a deepest MRD negativity should likely be the goal. This means that different MRD cut-offs at different time points should be considered in planning MRD-driven treatment strategies. Moreover, the question is if treatment decision can rely on a single MRD evaluation, or if, as for all the other response categories, MRD needs to be confirmed. This also affects the choice of the best time point (for instance, can we reasonably use a post-induction time point to make decisions on treatment intensification if we consider an induction with 4 cycles only?). Secondly, we should also consider the importance of MRD duration, particularly in the context of continuous therapy.

In the transplant-eligible setting, a further issue is the role of checking and the feasibility of pursuing MRD negativity in the peripheral blood stem-cell collection. Autografts contaminated with MM cells (MRD-positive autografts at a sensitivity of 10−7 by NGS) predicted a worse PFS than MRD-negative autografts [122]. However, this effect was mitigated in patients receiving further treatment after ASCT. Indeed, it should be noted that ASCT, consolidation and maintenance, especially with drugs not used during induction, still have the potential to eradicate MRD in a substantial number of patients who are MRD-positive at post-induction time point [7,8,43,70,123].

While the achievement of MRD negativity is clearly predictive of good outcomes, some NDMM patients are characterized by an MGUS-like plasma cell compartment [124]. In these patients, long-term disease control can be accomplished without achieving deep responses, probably due to an immune control of the residual disease. Further research is needed to reliably identify this patient population.

Moreover, the restoration of a physiological immune system at the time of MRD assessment could also play a role in predicting the patients that will possibly not relapse [28].

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, we are living exciting times in the field of MM, with many new regimens and strategies in the pipeline and an increasing knowledge of the complexity of the disease. Even if we currently do not have any evidence that we are able to cure MM in the great majority of treated patients, the longer follow-ups of the recent studies will determine the percentage of subjects able to actually maintain a disease-free status for a very long time. New well-designed MRD-driven trials will help us determine if it will be worth aiming at the cure of the disease and what will be the best therapeutic approach to achieve it.

Author Contributions

Substantial contributions to the conception or design: All the authors. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All the authors. First draft: M.D., L.B., S.O., and F.G. Supervision: M.B. and F.G. Critical revision for important intellectual content: All the authors. Final approval of the version to be published: All the authors. Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: All the authors.

Funding

No funding was provided for this contribution.

Conflicts of Interest

S.O. has received honoraria from Amgen, Celgene, and Janssen; and has served on the advisory boards for Adaptive Biotechnologies, Janssen, Amgen, and Takeda. M.B. has received honoraria from Sanofi, Celgene, Amgen, Janssen, Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and AbbVie; and has received research funding from Sanofi, Celgene, Amgen, Janssen, Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Mundipharma. F.G. has received honoraria from Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Janssen, Takeda, and served on the advisory boards for Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Janssen, Roche, Takeda, and AbbVie. The other authors declare no competing financial interests.

Abbreviations

| IMWG | International Myeloma Working Group |

| MRD | minimal residual disease |

| NGF | next-generation flow |

| NGS | next-generation sequencing |

| FLC | free light chain |

| M-protein | myeloma protein |

| FCM | flow cytometry |

| SUVmax | maximum standardized uptake value |

| MFC | multiparameter flow cytometry |

| FDG | Fluorodeoxyglucose |

| PET/CT | Positron emission tomography/computed tomography |

| N | number |

| TTP | time to progression |

| y | year |

| NR | not reached |

| CA | chromosomal abnormalities |

| PCs | plasma cells |

| BMPCs | bone marrow PCs |

| HR | hazard ratio |

| FLCr | free light chain ratio |

| FISH | fluorescence in situ hybridization |

| Pts | patients |

| V | bortezomib |

| R, Len | lenalidomide |

| d, dex | dexamethasone |

| T | thalidomide |

| FU | follow-up |

| PFS | progression-free survival |

| OS | overall survival |

| G | grade |

| P | p-value |

| MM | multiple myeloma |

| K | carfilzomib |

| CRAB | hypercalcemia, renal failure, anemia, and bone lesions |

| SMM | smoldering MM |

| ORR | overall response rate |

| Dara | daratumumab |

| ASCT | autologous stem-cell transplantation |

| Y | years |

| NA | not available |

| iv | intravenous |

| D | day |

| AE | adverse event |

| sc | subcutaneous |

| p.o. | orally |

| G-CSF | granulocyte colony-stimulating factor |

| Obs. | observation |

| TE | Transplant-eligible |

| NTE | non-transplant-eligible |

| NDMM | newly diagnosed multiple myeloma |

| C | cyclophosphamide |

| PD | progressive disease |

| MR | minimal response |

| PR | partial response |

| VGPR | very good PR |

| CR | complete response |

| nCR | near CR |

| sCR | stringent CR |

| CHF | congestive heart failure |

| SPMs | second primary malignancies |

| MRD neg | MRD negative/negativity |

| M, Mel | melphalan |

| Mel200 | melphalan at 200 mg/m2 |

| Bu | busulfan |

| p | prednisone |

| Ixa | ixazomib |

| SAEs | serious AEs |

| TEAEs | treatment-emergent AEs |

| GIT | gastrointestinal toxicity |

| QW | given every week |

| Q2W | given every two weeks |

| Q4W | given every 4 weeks |

| CI | confidence interval |

| ISS | International Staging System |

| R-ISS | Revised ISS |

| LDH | lactate dehydrogenase |

| EMD | extramedullary disease |

| CPC | circulating plasma cells |

| mAb | monoclonal antibody |

| PI | proteasome inhibitor |

| IMiDs | immunomodulatory drugs |

References

- Palumbo, A.; Anderson, K. Multiple myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1046–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferlay, J.; Colombet, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Dyba, T.; Randi, G.; Bettio, M.; Gavin, A.; Visser, O.; Bray, F. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: Estimates for 40 countries and 25 major cancers in 2018. Eur. J. Cancer 2018, 103, 356–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandakumar, B.; Binder, M.; Dispenzieri, A.; Kapoor, P.; Buadi, F.; Gertz, M.A.; Lacy, M.; Dingli, D.; Hwa, L.; Leung, N.; et al. Continued improvement in survival in multiple myeloma (MM) including high-risk patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37. Abstract #8039 [ASCO 2019 Meeting]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda-Avila, M.A.; Ortiz-Ortiz, K.J.; Torres-Cintrón, C.R.; Birmann, B.M.; Epstein, M.M. Trends in cause of death among patients with multiple myeloma in Puerto Rico and the United States SEER population, 1987–2013. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 146, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Delasalle, K.; Feng, L.; Thomas, S.; Giralt, S.; Qazilbash, M.; Handy, B.; Lee, J.J.; Alexanian, R. CR represents an early index of potential long survival in multiple myeloma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010, 45, 498–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, P.; Kumar, S.K.; Cerhan, J.R.; Maurer, M.J.; Dingli, D.; Ansell, S.M.; Rajkumar, S.V. Defining cure in multiple myeloma: A comparative study of outcomes of young individuals with myeloma and curable hematologic malignancies. Blood Cancer J. 2018, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avet-Loiseau, H.; Moreau, P.; Attal, M.; Hulin, C.; Arnulf, B.; Corre, J.; Garderet, L.; Karlin, L.; Lambert, J.; Macro, M.; et al. Efficacy of daratumumab (DARA) + bortezomib/thalidomide/dexamethasone (D-VTd) in transplant-eligible newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (TE NDMM) based on minimal residual disease (MRD) status: Analysis of the CASSIOPEIA trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37. Abstract #8017 [ASCO 2019 International Meeting]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, T.; Raje, N.S.; Vij, R.; Reece, D.; Berdeja, J.G.; Stephens, L.A.; McDonnell, K.; Rosenbaum, C.A.; Jasielec, J.; Richardson, P.G.; et al. Final Results of a Phase 2 Trial of Extended Treatment (tx) with Carfilzomib (CFZ), Lenalidomide (LEN), and Dexamethasone (KRd) Plus Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation (ASCT) in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma (NDMM). Blood 2016, 128. Abstract #675 [ASH 2016 58th Meeting]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, F.; Cerrato, C.; Petrucci, M.T.; Zambello, R.; Gamberi, B.; Ballanti, S.; Omedè, P.; Palmieri, S.; Troia, R.; Spada, S.; et al. Efficacy of carfilzomib lenalidomide dexamethasone (KRd) with or without transplantation in newly diagnosed myeloma according to risk status: Results from the forte trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37. Abstract #8002 [ASCO 2019 Annual Meeting]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorhees, P.M.; Rodriguez, C.; Reeves, B.; Nathwani, N.; Costa, L.J.; Lutska, Y.; Hoehn, D.; Pei, H.; Ukropec, J.; Qi, M.; et al. Efficacy and Updated Safety Analysis of a Safety Run-in Cohort from Griffin, a Phase 2 Randomized Study of Daratumumab (Dara), Bortezomib (V), Lenalidomide (R), and Dexamethasone (D.; Dara-Vrd) Vs. Vrd in Patients (Pts) with Newly Diagnosed (ND) Multiple, M. Blood 2018, 132. Abstract #151 [ASH 2018 60th Meeting]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubowiak, A.J.; Chari, A.; Lonial, S.; Weiss, B.M.; Comenzo, R.L.; Wu, K.; Khokhar, N.Z.; Wang, J.; Doshi, P.; Usmani, S.Z. Daratumumab (DARA) in combination with carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (KRd) in patients (pts) with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MMY1001): An open-label, phase 1b study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35. Abstract #8000 [ASCO 2017 Annual Meeting]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokhorst, H.M.; Schmidt-Wolf, I.; Sonneveld, P.; van der Holt, B.; Martin, H.; Barge, R.; Bertsch, U.; Schlenzka, J.; Bos, G.M.J.; Croockewit, S.; et al. Thalidomide in induction treatment increases the very good partial response rate before and after high-dose therapy in previously untreated multiple myeloma. Haematologica 2008, 93, 124–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahuerta, J.-J.; Paiva, B.; Vidriales, M.-B.; Cordón, L.; Cedena, M.-T.; Puig, N.; Martinez-Lopez, J.; Rosiñol, L.; Gutierrez, N.C.; Martín-Ramos, M.-L.; et al. Depth of Response in Multiple Myeloma: A Pooled Analysis of Three PETHEMA/GEM Clinical Trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 2900–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajkumar, S.V.; Harousseau, J.-L.; Durie, B.; Anderson, K.C.; Dimopoulos, M.; Kyle, R.; Blade, J.; Richardson, P.; Orlowski, R.; Siegel, D.; et al. Consensus recommendations for the uniform reporting of clinical trials: Report of the International Myeloma Workshop Consensus Panel 1. Blood 2011, 117, 4691–4695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Paiva, B.; Anderson, K.C.; Durie, B.; Landgren, O.; Moreau, P.; Munshi, N.; Lonial, S.; Bladé, J.; Mateos, M.-V.; et al. International Myeloma Working Group consensus criteria for response and minimal residual disease assessment in multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, e328–e346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, B.; Gutiérrez, N.C.; Rosiñol, L.; Vídriales, M.-B.; Montalbán, M.-Á.; Martínez-López, J.; Mateos, M.-V.; Cibeira, M.-T.; Cordón, L.; Oriol, A.; et al. High-risk cytogenetics and persistent minimal residual disease by multiparameter flow cytometry predict unsustained complete response after autologous stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma. Blood 2012, 119, 687–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanni, C.; Zamagni, E.; Versari, A.; Chauvie, S.; Bianchi, A.; Rensi, M.; Bellò, M.; Rambaldi, I.; Gallamini, A.; Patriarca, F.; et al. Image interpretation criteria for FDG PET/CT in multiple myeloma: A new proposal from an Italian expert panel. IMPeTUs (Italian Myeloma criteria for PET USe). Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2016, 43, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Montero, J.; de Tute, R.; Paiva, B.; Perez, J.J.; Böttcher, S.; Wind, H.; Sanoja, L.; Puig, N.; Lecrevisse, Q.; Vidriales, M.B.; et al. Immunophenotype of normal vs. myeloma plasma cells: Toward antibody panel specifications for MRD detection in multiple myeloma. Cytometry Part B Clin. Cytom. 2016, 90, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stetler-Stevenson, M.; Paiva, B.; Stoolman, L.; Lin, P.; Jorgensen, J.L.; Orfao, A.; Van Dongen, J.; Rawstron, A.C. Consensus guidelines for myeloma minimal residual disease sample staining and data acquisition. Cytometry Part B Clin. Cytom. 2016, 90, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Montero, J.; Sanoja-Flores, L.; Paiva, B.; Puig, N.; García-Sánchez, O.; Böttcher, S.; Van Der Velden, V.H.J.; Pérez-Morán, J.J.; Vidriales, M.B.; García-Sanz, R.; et al. Next Generation Flow for highly sensitive and standardized detection of minimal residual disease in multiple myeloma. Leukemia 2017, 31, 2094–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. Authorizes First Next Generation Sequencing-Based Test to Detect Very Low Levels of Remaining Cancer Cells in Patients with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia or Multiple Myeloma. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-authorizes-first-next-generation-sequencing-based-test-detect-very-low-levels-remaining-cancer (accessed on 23 October 2019).

- Faham, M.; Zheng, J.; Moorhead, M.; Carlton, V.E.H.; Stow, P.; Coustan-Smith, E.; Pui, C.H.; Campana, D. Deep-sequencing approach for minimal residual disease detection in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 2012, 120, 5173–5180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladetto, M.; Brüggemann, M.; Monitillo, L.; Ferrero, S.; Pepin, F.; Drandi, D.; Barbero, D.; Palumbo, A.; Passera, R.; Boccadoro, M.; et al. Next-generation sequencing and real-time quantitative PCR for minimal residual disease detection in B-cell disorders. Leukemia 2014, 28, 1299–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avet-Loiseau, H.; Bene, M.C.; Wuilleme, S.; Corre, J.; Attal, M.; Arnulf, B.; Garderet, L.; Macro, M.; Stoppa, A.-M.; Delforge, M.; et al. Concordance of Post-consolidation Minimal Residual Disease Rates by Multiparametric Flow Cytometry and Next-generation Sequencing in CASSIOPEIA. In Proceedings of the 17th International Myeloma Workshop, Boston, MA, USA, 12–15 September 2019; Volume 8. [Abstract #OAB–004]. [Google Scholar]

- Rawstron, A.C.; Gregory, W.M.; de Tute, R.M.; Davies, F.E.; Bell, S.E.; Drayson, M.T.; Cook, G.; Jackson, G.H.; Morgan, G.J.; Child, J.A.; et al. Minimal residual disease in myeloma by flow cytometry: Independent prediction of survival benefit per log reduction. Blood 2015, 125, 1932–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrot, A.; Lauwers-Cances, V.; Corre, J.; Robillard, N.; Hulin, C.; Chretien, M.L.; Dejoie, T.; Maheo, S.; Stoppa, A.M.; Pegourie, B.; et al. Minimal residual disease negativity using deep sequencing is a major prognostic factor in multiple myeloma. Blood 2018, 132, 2456–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateos, M.-V.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Cavo, M.; Suzuki, K.; Jakubowiak, A.; Knop, S.; Doyen, C.; Lucio, P.; Nagy, Z.; Kaplan, P.; et al. Daratumumab plus Bortezomib, Melphalan, and Prednisone for Untreated Myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paiva, B.; Cedena, M.T.; Puig, N.; Arana, P.; Vidriales, M.B.; Cordon, L.; Flores-Montero, J.; Gutierrez, N.C.; Martín-Ramos, M.L.; Martinez-Lopez, J.; et al. Minimal residual disease monitoring and immune profiling in multiple myeloma in elderly patients. Blood 2016, 127, 3165–3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawstron, A.C.; Child, J.A.; de Tute, R.M.; Davies, F.E.; Gregory, W.M.; Bell, S.E.; Szubert, A.J.; Navarro-Coy, N.; Drayson, M.T.; Feyler, S.; et al. Minimal Residual Disease Assessed by Multiparameter Flow Cytometry in Multiple Myeloma: Impact on Outcome in the Medical Research Council Myeloma IX Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 2540–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, S.; op Bruinink, D.H.; ŘÍhová, L.; Spada, S.; van der Holt, B.; Troia, R.; Gambella, M.; Pantani, L.; Grammatico, S.; Gilestro, M.; et al. Minimal residual disease (MRD) monitoring by multiparameter flow cytometry (MFC) in newly diagnosed transplant eligible multiple myeloma (MM) patients: Results from the EMN02/HO95 phase 3 trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, B.; Puig, N.; Cedena, M.T.; Cordon, L.; Vidriales, M.-B.; Burgos, L.; Flores-Montero, J.; Lopez-Anglada, L.; Gutierrez, N.; Calasanz, M.J.; et al. Impact of Next-Generation Flow (NGF) Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) Monitoring in Multiple Myeloma (MM): Results from the Pethema/GEM2012 Trial. Blood 2017, 130. Abstract #905 [ASH 2017 58th Meeting]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bladé, J.; Fernández De Larrea, C.; Rosiñol, L.; Cibeira, M.T.; Jiménez, R.; Powles, R. Soft-tissue plasmacytomas in multiple myeloma: Incidence, mechanisms of extramedullary spread, and treatment approach. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 3805–3812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, P. PET-CT in MM: A new definition of CR. Blood 2011, 118, 5984–5985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Moreau, P.; Attal, M.; Caillot, D.; Macro, M.; Karlin, L.; Garderet, L.; Facon, T.; Benboubker, L.; Escoffre-Barbe, M.; Stoppa, A.-M.; et al. Prospective Evaluation of Magnetic Resonance Imaging and [18F]Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography-Computed Tomography at Diagnosis and Before Maintenance Therapy in Symptomatic Patients With Multiple Myeloma Included in the IFM/DFCI 2009 Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 2911–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamagni, E.; Patriarca, F.; Nanni, C.; Zannetti, B.; Englaro, E.; Pezzi, A.; Tacchetti, P.; Buttignol, S.; Perrone, G.; Brioli, A.; et al. Prognostic relevance of 18-F FDG PET/CT in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients treated with up-front autologous transplantation. Blood 2011, 118, 5989–5995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartel, T.B.; Haessler, J.; Brown, T.L.Y.; Shaughnessy, J.D.; van Rhee, F.; Anaissie, E.; Alpe, T.; Angtuaco, E.; Walker, R.; Epstein, J.; et al. F18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in the context of other imaging techniques and prognostic factors in multiple myeloma. Blood 2009, 114, 2068–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamagni, E.; Nanni, C.; Dozza, L.; Carlier, T.; Tacchetti, P.; Versari, A.; Chauvie, S.; Gallamini, A.; Attal, M.; Gamberi, B.; et al. Standardization of 18F-FDG PET/CT According to Deauville Criteria for MRD Evaluation in Newly Diagnosed Transplant Eligible Multiple Myeloma Patients: Joined Analysis of Two Prospective Randomized Phase III Trials. Blood 2018, 132. Abstract #257 [ASH 2018 60th Meeting]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasche, L.; Alapat, D.; Kumar, M.; Gershner, G.; McDonald, J.; Wardell, C.P.; Samant, R.; Van Hemert, R.; Epstein, J.; Williams, A.F.; et al. Combination of flow cytometry and functional imaging for monitoring of residual disease in myeloma. Leukemia 2019, 33, 1713–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzotti, C.; Buisson, L.; Maheo, S.; Perrot, A.; Chretien, M.-L.; Leleu, X.; Hulin, C.; Manier, S.; Hébraud, B.; Roussel, M.; et al. Myeloma MRD by deep sequencing from circulating tumor DNA does not correlate with results obtained in the bone marrow. Blood Adv. 2018, 2, 2811–2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avet-Loiseau, H.; San-Miguel, J.F.; Casneuf, T.; Iida, S.; Lonial, S.; Usmani, S.Z.; Spencer, A.; Moreau, P.; Plesner, T.; Weisel, K.; et al. Evaluation of Sustained Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) Negativity in Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma (RRMM) Patients (Pts) Treated with Daratumumab in Combination with Lenalidomide Plus Dexamethasone (D-Rd) or Bortezomib Plus Dexamethasone (D-Vd): An. Blood 2018, 132. Abstract #3272 [ASH 2018 60th Meeting]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radich, J.P.; Deininger, M.; Abboud, C.N.; Altman, J.K.; Berman, E.; Bhatia, R.; Bhatnagar, B.; Curtin, P.; DeAngelo, D.J.; Gotlib, J.; et al. Chronic myeloid leukemia, version 1.2019. JNCCN J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2018, 16, 1108–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saussele, S.; Richter, J.; Guilhot, J.; Gruber, F.X.; Hjorth-Hansen, H.; Almeida, A.; Janssen, J.J.W.M.; Mayer, J.; Koskenvesa, P.; Panayiotidis, P.; et al. Discontinuation of tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy in chronic myeloid leukaemia (EURO-SKI): A prespecified interim analysis of a prospective, multicentre, non-randomised, trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Liu, J.; Chen, M.; Huang, B.; Li, J. Longitudinal Flow Cytometry Identified “Minimal Residual Disease” (MRD) Evolution Patterns for Predicting the Prognosis of Patients with Transplant-Eligible Multiple Myeloma. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018, 24, 2568–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, S.V.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Palumbo, A.; Blade, J.; Merlini, G.; Mateos, M.-V.; Kumar, S.; Hillengass, J.; Kastritis, E.; Richardson, P.; et al. International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, e538–e548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshman, A.; Vincent Rajkumar, S.; Buadi, F.K.; Binder, M.; Gertz, M.A.; Lacy, M.Q.; Dispenzieri, A.; Dingli, D.; Fonder, A.L.; Hayman, S.R.; et al. Risk stratification of smoldering multiple myeloma incorporating revised IMWG diagnostic criteria. Blood Cancer J. 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherry, B.M.; Korde, N.; Kwok, M.; Manasanch, E.E.; Bhutani, M.; Mulquin, M.; Zuchlinski, D.; Yancey, M.A.; Maric, I.; Calvo, K.R.; et al. Modeling progression risk for smoldering multiple myeloma: Results from a prospective clinical study. Proc. Leuk. Lymphoma 2013, 54, 2215–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyle, R.A.; Remstein, E.D.; Therneau, T.M.; Dispenzieri, A.; Kurtin, P.J.; Hodnefield, J.M.; Larson, D.R.; Plevak, M.F.; Jelinek, D.F.; Fonseca, R.; et al. Clinical Course and Prognosis of Smoldering (Asymptomatic) Multiple Myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 2582–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Persona, E.; Vidriales, M.B.; Mateo, G.; García-Sanz, R.; Mateos, M.V.; De Coca, A.G.; Galende, J.; Martín-Nuñez, G.; Alonso, J.M.; De Heras, N.L.; et al. New criteria to identify risk of progression in monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance and smoldering multiple myeloma based on multiparameter flow cytometry analysis of bone marrow plasma cells. Blood 2007, 110, 2586–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Miguel, J.; Mateos, M.-V.; Gonzalez, V.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Kastritis, E.; Hajek, R.; de Larrea Rodríguez, C.; Morgan, G.J.; Merlini, G.; Mangiacavalli, S.; et al. Updated risk stratification model for smoldering multiple myeloma (SMM) incorporating the revised IMWG diagnostic criteria. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37. Abstract #8000 [ASCO 2019 Annual Meeting] Updated data presented at the meeting. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, F.; Oliva, S.; Petrucci, M.T.; Conticello, C.; Catalano, L.; Corradini, P.; Siniscalchi, A.; Magarotto, V.; Pour, L.; Carella, A.; et al. Chemotherapy plus lenalidomide versus autologous transplantation, followed by lenalidomide plus prednisone versus lenalidomide maintenance, in patients with multiple myeloma: A randomised, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 1617–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Corral, L.; Gutiérrez, N.C.; Vidriales, M.B.; Mateos, M.V.; Rasillo, A.; García-Sanz, R.; Paiva, B.; San Miguel, J.F. The progression from MGUS to smoldering myeloma and eventually to multiple myeloma involves a clonal expansion of genetically abnormal plasma cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 1692–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos, M.V.; Hernández, M.T.; Giraldo, P.; de la Rubia, J.; de Arriba, F.; Corral, L.L.; Rosiñol, L.; Paiva, B.; Palomera, L.; Bargay, J.; et al. Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone versus observation in patients with high-risk smouldering multiple myeloma (QuiRedex): Long-term follow-up of a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 1127–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korde, N.; Roschewski, M.; Zingone, A.; Kwok, M.; Manasanch, E.E.; Bhutani, M.; Tageja, N.; Kazandjian, D.; Mailankody, S.; Wu, P.; et al. Treatment With Carfilzomib-Lenalidomide-Dexamethasone With Lenalidomide Extension in Patients With Smoldering or Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma. JAMA Oncol. 2015, 1, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateos, M.-V.; Martínez-López, J.; Rodríguez-Otero, P.; de la Calle, G.V.; González, M.-S.; Oriol, A.; Gutiérrez, N.-C.; Paiva, B.; Rios, R.; Rosiñol, L.; et al. Curative strategy (gem-cesar) for high-risk smoldering myeloma: Carfilzomib, lenalidomide and dexamethasone (krd) as induction followed by hdt-asct, consolidation with krd and maintenance with rd. HemaSphere 2019, 3, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailankody, S.; Salcedo, M.; Tavitian, E.; Korde, N.; Lendvai, N.; Hassoun, H.; Lesokhin, A.M.; Lahoud, O.B.; Smith, E.L.; Hultcrantz, M.; et al. Ixazomib and dexamethasone in high risk smoldering multiple myeloma: A clinical and correlative pilot study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37. Abstract #8051 [ASCO 2019 Annual Meeting]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagannath, S.; Laubach, J.; Wong, E.; Stockerl-Goldstein, K.; Rosenbaum, C.; Dhodapkar, M.; Jou, Y.-M.; Lynch, M.; Robbins, M.; Shelat, S.; et al. Elotuzumab monotherapy in patients with smouldering multiple myeloma: A phase 2 study. Br. J. Haematol. 2018, 182, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Ghobrial, I.M.; Bustoros, M.; Reyes, K.; Hornburg, K.; Badros, A.Z.; Vredenburgh, J.J.; Boruchov, A.; Matous, J.V.; Caola, A.; et al. Phase II Trial of Combination of Elotuzumab, Lenalidomide, and Dexamethasone in High-Risk Smoldering Multiple Myeloma. Blood 2018, 132. Abstract #154 [ASH 2018 60th Meeting]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustoros, M.; Liu, C.; Reyes, K.; Hornburg, K.; Guimond, K.; Styles, R.; Savell, A.; Berrios, B.; Warren, D.; Dumke, H.; et al. Phase II Trial of the Combination of Ixazomib, Lenalidomide, and Dexamethasone in High-Risk Smoldering Multiple Myeloma. Blood 2018, 132. Abstract #804 [ASH 2018 60th Meeting]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brighton, T.A.; Khot, A.; Harrison, S.J.; Ghez, D.; Weiss, B.M.; Kirsch, A.; Magen, H.; Gironella, M.; Oriol, A.; Streetly, M.; et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study of siltuximab in high-risk smoldering multiple myeloma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 3772–3775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landgren, O.; Cavo, M.; Chari, A.; Cohen, Y.C.; Spencer, A.; Voorhees, P.M.; Estell, J.; Sandhu, I.; Jenner, M.; Williams, C.; et al. Updated Results from the Phase 2 Centaurus Study of Daratumumab (DARA) Monotherapy in Patients with Intermediate-Risk or High-Risk Smoldering Multiple Myeloma (SMM). Blood 2018, 132. Abstract #1994 [ASH 2018 60th Meeting]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, S.V.; Voorhees, P.M.; Goldschmidt, H.; Baker, R.I.; Bandekar, R.; Kuppens, S.; Neff, T.; Qi, M.; Dimopoulos, M.A. Randomized, open-label, phase 3 study of subcutaneous daratumumab (DARA SC) versus active monitoring in patients (Pts) with high-risk smoldering multiple myeloma (SMM): AQUILA. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36. Abstract #TPS8062 (ASCO 2018 Annual Meeting]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonial, S.; Jacobus, S.; Fonseca, R.; Weiss, M.; Kumar, S.; Orlowski, R.Z.; Kaufman, J.L.; Yacoub, A.M.; Buadi, F.K.; O’Brien, T.; et al. Randomized Trial of Lenalidomide Versus Observation in Smoldering Multiple Myeloma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37. Abstract #8001 [ASCO 2019 Annual Meeting]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlogie, B.; Jagannath, S.; Desikan, K.R.; Mattox, S.; Vesole, D.; Siegel, D.; Tricot, G.; Munshi, N.; Fassas, A.; Singhal, S.; et al. Total therapy with tandem transplants for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Blood 1999, 93, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barlogie, B.; Mitchell, A.; van Rhee, F.; Epstein, J.; Yaccoby, S.; Zangari, M.; Heuck, C.; Hoering, A.; Morgan, G.J.; Crowley, J. Curing Multiple Myeloma (MM) with Total Therapy (TT). Blood 2014, 124. Abstract #195 [ASH 2014 56th Meeting]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos, M.V.; San Miguel, J.F. Management of multiple myeloma in the newly diagnosed patient. Hematology 2017, 2017, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreau, P.; Attal, M.; Facon, T. Frontline therapy of multiple myeloma. Blood 2015, 125, 3076–3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harousseau, J.-L.; Attal, M.; Avet-Loiseau, H.; Marit, G.; Caillot, D.; Mohty, M.; Lenain, P.; Hulin, C.; Facon, T.; Casassus, P.; et al. Bortezomib plus dexamethasone is superior to vincristine plus doxorubicin plus dexamethasone as induction treatment prior to autologous stem-cell transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: Results of the IFM 2005-01 phase III trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 4621–4629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, F.; Engelhardt, M.; Terpos, E.; Wäsch, R.; Giaccone, L.; Auner, H.W.; Caers, J.; Gramatzki, M.; van de Donk, N.; Oliva, S.; et al. From transplant to novel cellular therapies in multiple myeloma: EMN guidelines and future perspectives. Haematologica 2018, 103, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, P.; Hulin, C.; Macro, M.; Caillot, D.; Chaleteix, C.; Roussel, M.; Garderet, L.; Royer, B.; Brechignac, S.; Tiab, M.; et al. VTD is superior to VCD prior to intensive therapy in multiple myeloma: Results of the prospective IFM2013-04 trial. Blood 2016, 127, 2569–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussel, M.; Lauwers-Cances, V.; Robillard, N.; Hulin, C.; Leleu, X.; Benboubker, L.; Marit, G.; Moreau, P.; Pegourie, B.; Caillot, D.; et al. Front-line transplantation program with lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone combination as induction and consolidation followed by lenalidomide maintenance in patients with multiple myeloma: A phase II study by the Intergroupe Francophone du Myélome. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 2712–2717. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Flinn, I.; Richardson, P.G.; Hari, P.; Callander, N.; Noga, S.J.; Stewart, A.K.; Turturro, F.; Rifkin, R.; Wolf, J.; et al. Randomized, multicenter, phase 2 study (EVOLUTION) of combinations of bortezomib, dexamethasone, cyclophosphamide, and lenalidomide in previously untreated multiple myeloma. Blood 2012, 119, 4375–4382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlyn, C.; Davies, F.; Cairns, D.; Striha, A.; Hockaday, A.; Kishore, B.; Garg, M.; Williams, C.; Karunanithi7, K.; Lindsay, J.; et al. Quadruplet KCRD (Carfilzomib, Cyclophosphamide, Lenalidomide and Dexamethasone) Induction for Newly Diagnosed Myeloma Patients. In Proceedings of the International Myeloma Workshop, Boston, MA, USA, 12–15 September 2019; p. e2, [Abstract #OAB–002]. Updated data presented at the meeting. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, G.H.; Davies, F.E.; Pawlyn, C.; Cairns, D.; Striha, A.; Hockaday, A.; Collett, C.; Jones, J.R.; Kishore, B.; Garg, M.; et al. A Quadruplet Regimen Comprising Carfilzomib, Cyclophosphamide, Lenalidomide, Dexamethasone (KCRD) Vs an Immunomodulatory Agent Containing Triplet (CTD/CRD) Induction Therapy Prior to Autologous Stem Cell Transplant: Results of the Myeloma XI Study. Blood 2018, 132. Abstract #302 [ASH 2018 60th Meeting]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attal, M.; Lauwers-Cances, V.; Hulin, C.; Leleu, X.; Caillot, D.; Escoffre, M.; Arnulf, B.; Macro, M.; Belhadj, K.; Garderet, L.; et al. Lenalidomide, Bortezomib, and Dexamethasone with Transplantation for Myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1311–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosinol, L.; Oriol, A.; Rios, R.; Sureda, A.; Blanchard, M.J.; Hernández, M.T.; Martínez-Martínez, R.; Moraleda, J.M.; Jarque, I.; Bargay, J.; et al. Bortezomib, Lenalidomide and Dexamethasone (VRD-GEM) As Induction Therapy Prior Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation (ASCT) in Multiple Myeloma (MM): Results of a Prospective Phase III Pethema/GEM Trial. Blood 2017, 130. Abstract #2017 [ASH 2017 59th Annual Meeting]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorhees, P.; Kaufman, J.L.; Laubach, J.; Sborov, D.; Reeves, B.; Rodriguez, C.; Chari, A.; Silbermann, R.; Costa, L.; Anderson, L.; et al. Daratumumab + Lenalidomide, Bortezomib & Dexamethasone Improves Depth of Response in Transplant-eligible Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma: GRIFFIN. In Proceedings of the 17th International Myeloma Workshop, Boston, MA, USA, 12–15 Septemebr 2019; pp. 546–547, [Abstract #OAB–87]. [Google Scholar]

- Moreau, P.; Attal, M.; Hulin, C.; Arnulf, B.; Belhadj, K.; Benboubker, L.; Béné, M.C.; Broijl, A.; Caillon, H.; Caillot, D.; et al. Bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone with or without daratumumab before and after autologous stem-cell transplantation for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (CASSIOPEIA): A randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet 2019, 394, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.K.; Berdeja, J.G.; Niesvizky, R.; Lonial, S.; Laubach, J.P.; Hamadani, M.; Stewart, A.K.; Hari, P.; Roy, V.; Vescio, R.; et al. Ixazomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: Long-term follow-up including ixazomib maintenance. Leukemia 2019, 33, 1736–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosiñol Dachs, L.; Hebraud, B.; Oriol, A.; Colin, A.-L.; Rios, R.; Hulin, C.; Blanchard, M.J.; Caillot, D.; Sureda, A.; Hernández, M.T.; et al. Integrated Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials Evaluating Bortezomib + Lenalidomide + Dexamethasone or Bortezomib + Thalidomide + Dexamethasone Induction in Transplant-Eligible Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma. Blood 2018, 132. Abstract #3245 [ASH 2018 60th Meeting]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, A.; Cavallo, F.; Gay, F.; Di Raimondo, F.; Ben Yehuda, D.; Petrucci, M.T.; Pezzatti, S.; Caravita, T.; Cerrato, C.; Ribakovsky, E.; et al. Autologous Transplantation and Maintenance Therapy in Multiple Myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 895–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavo, M.; Hájek, R.; Pantani, L.; Beksac, M.; Oliva, S.; Dozza, L.; Johnsen, H.E.; Petrucci, M.T.; Mellqvist, U.-H.; Conticello, C.; et al. Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation Versus Bortezomib-Melphalan-Prednisone for Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma: Second Interim Analysis of the Phase 3 EMN02/HO95 Study. Blood 2017, 130. Abstract #397 [ASH 2017 59th Meeting]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavo, M.; Goldschmidt, H.; Rosinol, L.; Pantani, L.; Zweegman, S.; Salwender, H.J.; Lahuerta, J.J.; Lokhorst, H.M.; Petrucci, M.T.; Blau, I.; et al. Double Vs Single Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation for Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma: Long-Term Follow-up (10-Years) Analysis of Randomized Phase 3 Studies. Blood 2018, 132. Abstract #124 [ASH 2018 60th Meeting]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadtmauer, E.A.; Pasquini, M.C.; Blackwell, B.; Hari, P.; Bashey, A.; Devine, S.; Efebera, Y.; Ganguly, S.; Gasparetto, C.; Geller, N.; et al. Autologous transplantation, consolidation, and maintenance therapy in multiple myeloma: Results of the BMT CTN 0702 trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonneveld, P.; Beksac, M.; Van der Holt, B.; Dimopoulos, M.; Carella, A.; Ludwig, H.; Driessen, C.; Wester, R.; Hajek, R.; Cornelisse, P.; et al. Consolidation followed by maintenance vs maintenance alone in newly diagnosed, transplant eligible multiple myeloma: A randomized phase 3 study of the european myeloma network (emn02/ho95 mm trial). HemaSphere 2018, 2, 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, P.L.; Holstein, S.A.; Petrucci, M.T.; Richardson, P.G.; Hulin, C.; Tosi, P.; Bringhen, S.; Musto, P.; Anderson, K.C.; Caillot, D.; et al. Lenalidomide Maintenance After Autologous Stem-Cell Transplantation in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma: A Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 3279–3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, G.H.; Davies, F.E.; Pawlyn, C.; Cairns, D.A.; Striha, A.; Collett, C.; Hockaday, A.; Jones, J.R.; Kishore, B.; Garg, M.; et al. Lenalidomide maintenance versus observation for patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (Myeloma XI): A multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]