Abstract

There is a lack of research directly examining the relationships between future orientation, individualism, prosocial engagement and identity status among Chinese youth. This study focuses on the moderating role of identity status in the relationship between individualistic values, future orientation and prosocial behaviours. The study sample consists of 1817 Chinese youth aged between 15 and 28. Six patterns of identity statuses were identified by a hierarchical cluster analysis. Path analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between the independent variables and youths’ prosocial engagement and the moderating effects of identity status. The results showed that future orientation is significantly related to prosocial engagement, while individualistic value is not significantly associated with it. The interaction of future orientation and identity status significantly affects prosocial engagement. The effect of future orientation is greater for those in searching moratorium and carefree diffusion and lower for those in achievement and foreclosure. These imply that time perspective intervention may facilitate the prosocial engagement of students who lack a mature and committed identity.

2. Procedure and Methods

The data came from the first phase of a longitudinal study conducted by the authors about youth identity status and psychosocial well-being. Participants were recruited from 14 secondary schools and 36 higher educational institutions in Hong Kong. Secondary schools were selected randomly from the school lists in Hong Kong, and invitation letters were sent to the selected schools for consent to distribute the questionnaire to their students. This study included secondary schools and higher education institutions from various districts and different banding systems. The research assistant contacted the students onsite or online to collect the data. College students were invited through the researchers’ networks. A professional survey company assisted with data collection. The company is a research institution established in 2000 by a university in Hong Kong, and it became independent in 2009. It has conducted more than 600 research projects for academic staff of universities and government units in Hong Kong. Invalid cases were removed from the sample. Participants who completed the questionnaire in less than 10 min and showed repeated patterns in scales (especially with reversed items) were considered as providing invalid responses. A total of 2333 samples were collected, of which 493 were excluded based on the abovementioned criteria. Additionally, 23 cases were removed for not meeting the cluster-analysis criteria. Therefore, the final sample size is 1817. Information was successfully obtained from 1817 youth aged between 15 and 28. There were 727 male respondents and 1090 female respondents. The demographic information of participants is stated in Table 1. The mean age was 18.94 with a standard deviation of 2.96. This study involved 958 secondary school students and 882 college students. Of these, 1495 were local-born Hong Kong residents, and 322 were non-local-born residents. The non-local-born students came from Mainland China and Macau and have similar cultural backgrounds to those of local Hong Kong Chinese students. A total of 29.0% of the respondents’ fathers had attained a high school education, while 14.4% had a college education or higher. Meanwhile, 34.1% of the respondents’ mothers had completed high school, while 12.2% had a college education or higher. A total of 49.8% of the respondents came from government-aided secondary schools, 2.4% from government-owned or direct subsided secondary schools, 32.8% from self-financed degree programmes, 10.2% from government-funded degree programmes, 4.4% from self-financed sub-degree programmes, and 0.4% from government-funded sub-degree programmes. Among the respondents, 443 (24.22%) were classified as Moratorium; 413 (22.73%) were Searching Moratorium; 391 (21.52%) were Foreclosure; 236 (12.99%) were Carefree Diffusion; 188 (10.35%) were Achievement and 146 (8.04%) were Diffused Diffusion.

Table 1.

Demographic information of participants.

2.1. Ethical Approval

Online informed consent was obtained from the participants. Participants were required to indicate their acceptance to join this study before starting to fill in the online questionnaire. Parents of participants under 18 years old from secondary schools were also informed via email or letter. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the University’s research ethics committee. No animals were used in this research. All human research procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional committee and with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Prosocial Engagement

The 16-item Prosocialness Scale for Adults was adopted to assess four fundamental aspects of prosocial behaviours: helping behaviours, sharing, attempting to take care of others, willingness to help and assist the needy, and feeling empathic with others (Caprara et al., 2005). Participants were asked to rate the extent of each item in describing themselves on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1, never true, to 5, almost always true. Examples of scale items contain statements such as, “I share the things that I have with my friends” and “I try to be close to and take care of those who are in need”. Statements include helping behaviours toward both in-group and out-group members. The higher the score, the greater the level of prosocial behaviour. The scale has confirmed adequate psychometric properties, good reliability, and high construct validity (Caprara et al., 2005). The Cronbach’s Alpha of this scale in this study is 0.92, which implies very good reliability.

2.2.2. Individualistic Value

The 8-item short-form measurement of individualism (IND) was used (Triandis & Gelfand, 1998). The scale has been proven to have configural and metric equivalence, good reliability, as well as good convergent and divergent validity (Cozma, 2011). The construct of IND comprises two factors, horizontal individualism and vertical individualism, each with four items. Examples of scale items contain statements such as, “I’d rather depend on myself than others” and “Competition it the law of nature”. The Cronbach’s Alpha of horizontal individualism and vertical individualism sub-scales in this study are 0.81 and 0.80, respectively, which implies good reliability.

2.2.3. Future Orientation

Five items from the Consideration of Future Consequences Scale were employed to measure future orientation (Strathman et al., 1994). Respondents indicated whether or not the statement is characteristic of themselves from a 5-point Likert Scale from 1, “extremely uncharacteristic”, to 5, “extremely characteristic.” Examples of scale items contain statements such as “Often I engage in a particular behaviour in order to achieve outcomes that may not result for many years” and “I am willing to sacrifice my immediate happiness or well-being in order to achieve future outcomes”. The one-dimension scale has been confirmed with very good internal consistency in four samples of university students with a Cronbach’s alpha between 0.80 and 0.86 (Strathman & Joireman, 2005). The convergent validity of the scale was supported by its relationship with other individual-differences measures (Strathman et al., 1994). The Cronbach’s Alpha of this scale in this study is 0.78, which implies good reliability.

2.2.4. Identity Status

The 25-item Dimensions of Identity Development Scale (DIDS) was employed to measure the identity status of participants. The scale is rated on a 5-point Likert Scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), which consists of five items per each of the five identity dimensions: commitment making, identification with commitment, exploration in breadth, exploration in depth, and ruminative exploration (Luyckx et al., 2008). Examples of scale items contain statements such as “I have decided on the direction I am going to follow in my life”, “I think about different goals that I might pursue”, “I worry about what I want to do with my future”, “My future plans give me self-confidence” and “I think about the future plans I already made”. A mean score was computed for each dimension; the higher the score, the greater the level. Participants were classified into six identity clusters based on the mean score of these dimensions. The five identity dimensions model was proved to have good internal and external validity (Luyckx et al., 2008).

Using IBM Statistics SPSS (version 27), cluster analyses were conducted for each sample using a two-step procedure (Gore, 2000). Before the implementation of this clustering procedure, 18 multivariate outliers (with high Mahalanobis distance values) were removed. Firstly, a hierarchical cluster analysis was conducted on the five identity dimensions using Ward’s method based on squared Euclidean distances. After evaluating the four- to six-cluster solution, a 6-cluster solution was retained based on the theoretical interpretability, parsimony, and explanatory power of the cluster solution (the cluster solution had to explain at least 50% of the variance in the different identity dimensions). Secondly, the initial cluster centres were used in an iterative k-means clustering procedure. As a result, six patterns of identity statuses are identified from the scale: Carefree Diffusion, Moratorium, Achievement, Diffused Diffusion, Searching Moratorium, and Foreclosure. The five sub-scales of DIDS have good reliability (Commitment making = 0.89, Identification with commitment = 0.85, Exploration in breadth = 0.84, Exploration in depth = 0.77, and Ruminative exploration = 0.80). A confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to examine the factor structure of DIDS. The results confirmed the six patterns of identity statuses with satisfactory to good model fit (RMSEA < 0.001, CFI = 0.918, TLI = 0.901 and SRMR = 0.064).

Similar to the findings by Luyckx et al. (2008), the Achievement cluster scored high on both commitment dimensions and exploration in depth, intermediate on exploration in breadth, and from low to very low on ruminative exploration. These youths have high commitment and exploration with mature identity status. They continue to gather information and strongly identify with their choices. The Foreclosure cluster scored moderately high on commitment and moderately low on all exploration dimensions. These youths commit to an identity and values that others place on them without exploring. Moratorium was characterised by a low score on both commitment dimensions and a from moderate to high score on exploration dimensions. The Moratorium status represents the transitional crisis. These youths continue to search for alternatives but fail to identify with any option and feel pressured to make a specific choice. The Searching Moratorium cluster scored moderately high in all dimensions. Youths with searching moratorium status are more adaptive than those with Moratorium status who are unsuccessful in finding alternative commitments (Meeus et al., 2012). In contrast, participants in the Diffused Diffusion cluster scored from low to very low on commitment and exploration dimensions and high on ruminative exploration. Diffused Diffusion represents individuals who have attempted to develop a sense of identity but seem to be locked in a ruminative cycle of perpetual exploration (S. J. Schwartz et al., 2012). Carefree Diffusion was characterised by from low to intermediate scores on both commitment dimensions, very low scores on exploration in breadth and depth, and moderately low scores on ruminative exploration. These youths lack an interest in engaging in any form of exploration and are unbothered by the absence of commitment (Luyckx et al., 2011).

The researchers translated all scales from English to Chinese and then back-translated them to the original version, consulting a native English scholar for appropriateness. Before the data collection, a pilot test with 465 samples was conducted. Based on the results, the Chinese wordings of the scales were further revised, and all scales showed good internal consistency.

2.3. Analytical Plan

First, the three independent variables were mean-centred to obtain a Z-score for analysis. Given the moderator, identity status is a six-class categorical variable; five dummy variables were created and then interacted with three independent variables to obtain 15 interactions in SPSS 27.0. After that, two models were run to conduct path analysis in Mplus 7.4; the first model contains only the independent variables (future orientation, horizontal individualism and vertical individualism) to determine whether the three independent variables accounted for a significant amount of variance in youths’ prosocial engagement. Next, the interaction terms for identity status were added in the second model. The Searching Moratorium group was chosen as a reference group because these young people are highly explorative but have not yet developed a mature identity status. Gender, age, and education level were added as control variables in the two models.

3. Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations among independent and dependent variables are stated in Table 2. The mean score of prosocialness is 3.58 out of 5, implying respondents have moderate levels of prosocial engagement. The mean score of future orientation is 4.59 out of 7, which implies moderate levels of consideration of future consequences among participants. The mean scores of horizontal individualism and vertical individualism are 6.31 and 5.84 out of 9, respectively, implying that young Chinese people in Hong Kong value independence and equality among individuals, but they place less emphasis on competition and personal advancement. According to the correlational analyses, prosocial engagement is positively related to future orientation, horizontal individualism, and vertical individualism (β = 0.34, p < 0.001; β = 0.09, p < 0.001; β = 0.08, p < 0.001). Future orientation is positively related to horizontal individualism and vertical individualism (β = 0.30, p < 0.001; β = 0.19, p < 0.001). Horizontal individualism and vertical individualism are positively related (β = 0.41, p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Mean, standard deviations and correlation matrix between variables.

In model one, after controlling gender, age, local/nonlocal, father/mother education levels, and participant’s education level, the results indicated that future orientation is significantly and positively related to prosocial engagement (b = 0.34, p = 0.000), but two dimensions of individualism are both insignificantly related to prosocial engagement (horizontal individualism, b = −0.03, p = 0.216; vertical individualism, b = 0.02, p = 0.390). Respondents with an identity status with a high level of exploration in breadth and exploration in depth have a high level of prosocial engagement, such as achievement (b = 0.67, p < 0.001), moratorium (b = 0.44, p < 0.001), and searching moratorium (b = 0.60, p < 0.001). Consistent with previous studies, females have more prosocial behaviour than males (b = 0.21, p < 0.001). Non-local students have more prosocial behaviour than local students (b = −0.08, p < 0.001). However, age, education levels of the father and mother, and participant’s education level are unrelated to prosocial engagement (b = −0.01, p = 0.580; b = 0.01, p = 0.692; b = −0.01, p = 0.593; b = −0.06, p = 0.467). The findings of this study are at odds with previous research suggesting that age and education influence prosocial behaviour. The specific educational context in Hong Kong may diminish the effects of these factors. In Hong Kong, senior secondary students are required to participate in well-organized community service programs integrated into the school curriculum. This involvement facilitates high school students’ engagement in prosocial behaviours. As a result, younger secondary students in Hong Kong may demonstrate levels of prosocial engagement comparable to, or even higher than, those of older college students.

In model two, the moderation analysis indicated that the relationship between future orientation and prosocial engagement in the Diffused Diffusion and Foreclosure groups was significantly different from the relationship between future orientation and prosocial engagement in the Searching Moratorium group (Diffused diffusion, binteraction = −0.28, p = 0.006; Foreclosure, binteraction = −0.16, p = 0.036). In these three groups, future orientation is significantly related to prosocial engagement, except for in the Diffused Diffusion group (Searching Moratorium group: b = 0.38, p = 0.000; Diffused Diffusion group: b = 0.10, p = 0.271; Foreclosure group: b = 0.22, p = 0.000). The results indicated that future orientation had a stronger positive relationship with prosocial engagement in the Searching Moratorium group than in the Diffused Diffusion and Foreclosure groups.

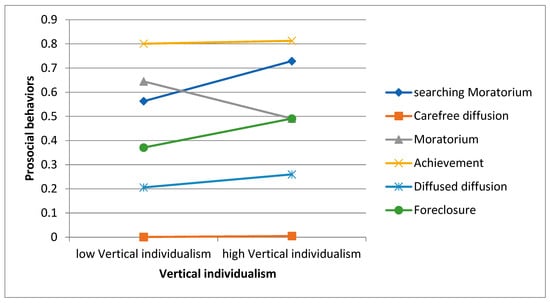

For individualism, the moderation analysis indicated that the relationship between vertical individualism and prosocial engagement in the Moratorium group is significantly different from the relationship between vertical individualism and prosocial engagement in the Searching Moratorium group (Moratorium, binteraction = −0.16, p = 0.021). In the Searching Moratorium group, vertical individualism is insignificantly related to prosocial engagement (Searching Moratorium group: b = 0.08, p = 0.105). In the Moratorium group, vertical individualism is related to prosocial engagement at a marginally significant level (b = −0.08, p = 0.098). The results indicated that vertical individualism is more likely to have a negative association with prosocial behaviours in the Moratorium group compared with the reference group (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Results for the moderating role of identity in the relationship between vertical individualism and prosocialness (N = 1817).

4. Conclusions and Discussion

The results of the path analysis indicated that youth who have a mature identity, characterized by high levels of both breadth and depth of exploration, engage in more prosocial behaviours compared to those with lower levels of exploration in both areas. Openness and curiosity are vital to identity exploration (Luyckx et al., 2008). Prosocial engagement is one of the means that allows youth to explore their goals, values, and beliefs before making commitments. Therefore, youth with Achievement, Moratorium, and Searching Moratorium statuses have more prosocial engagement. This finding implies that having a more mature and adaptive identity status may result in greater prosocial engagement. The continuous search for various alternatives and attitudes is essential for encouraging prosocial actions. However, youth with a Foreclosure identity show high commitment but low exploration, which discourages prosocial engagement.

The results of the present study failed to support the direct relationship between individualistic values and prosocial engagement. This study revealed that Hong Kong youth have higher levels of horizontal individualist values than vertical individualist values (M = 6.31/9; M = 5.84/9). Western values may foster independence in Hong Kong youth, but Chinese values may prevent them from prioritizing competitiveness and individual achievement. Both Western individualism and Confucianism emphasise the importance of achievement and success; Chinese youths may understand and practice them in different ways than their counterparts in Western societies (Weng et al., 2021). Although Chinese culture emphasises collectivistic values, young people in Hong Kong may be influenced by individualistic values in certain situations. According to the results of model two, identity status moderates the relationship between vertical individualism and prosocial engagement. Vertical individualism is marginally related to prosocial engagement only in the Moratorium group but is not related in other groups. Youth in the Moratorium group have low commitments but high exploration. Emphasizing individual autonomy with low commitment and high exploration may cause youth to focus on their achievement and neglect the needs of others, reducing prosocial tendencies. Other studies found that individualism is associated with career-related volunteer motivation (Finkelstein, 2010). Although individualism focuses on autonomy and self-fulfilment and favours personal goals over group goals, the autonomy treasured in individualism may encourage individuals to help strangers and become involved in civic activities to voice out and fight for their benefits. Autonomy also facilitates respect for others and a sense of personal responsibility that encourages volunteering (Waterman, 1981). The above findings contradict Triandis’s (2001) conclusion that individuals with high individualistic values are less likely to serve the community. Therefore, inconclusive results have been found in the present Hong Kong study and previous studies in other societies. Individualistic values may enhance or discourage prosocial engagement. However, the present study further suggests that vertical individualistic value is negatively related to prosocial engagement for youth with Moratorium identity status.

The limited connection between individualistic values and prosocial behaviour may stem from endorsing collectivistic values in Chinese culture. In this context, the individualistic values held by the Chinese may differ from those of Westerners. The emphasis on community and social responsibility fosters prosocial behaviour (Bartolo et al., 2023). Relational harmony and social responsibility are key components of Confucian ethics in China that encourage young people to engage in prosocial actions. These values inspire individuals to consider the needs of others, helping to counterbalance the influence of individualistic values. Among Chinese youths in Hong Kong, the coexistence of both collectivistic and individualistic values among Chinese youth may reduce the adverse effects of individualism on their engagement in prosocial activities. Further studies may be conducted to clarify the relationship between individualism and prosocial engagement in different identity statuses and compare the situations in Western and Asian societies.

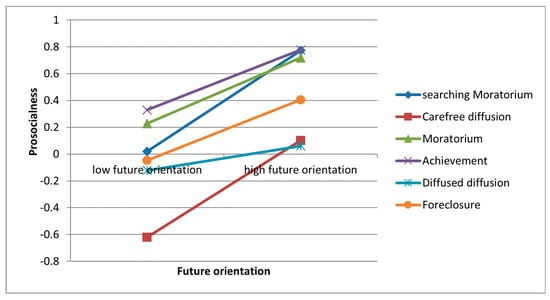

Identity status moderates the relationship between future orientation and prosocial engagement (see Figure 2). After controlling identity status, future orientation is not related to prosocial engagement for youth with an identity status of Diffused Diffusion. In contrast, future orientation is positively associated with prosocial engagement for youth in other statuses. The relationship between future orientation with prosocial engagement is greater for those in Searching Moratorium (b = 0.25, p < 0.001) and Carefree Diffusion (b = 0.23, p < 0.001) and is lower for those in Achievement (b = 0.14, p = 0.01) and Foreclosure (b = 0.15, p < 0.001). These results imply that the relationship between future orientation and prosocial engagement for those youth who feel sure about and identify with and internalise their choices with commitment is weak. These youth with more mature identity statuses guide them on their life paths. The results above add value to the recent discussion and demonstrate that the relationship between future orientation and prosocial engagement can differ depending on a youth’s identity status.

Figure 2.

Results for the moderating role of identity in the relationship between future orientation and prosocialness (N = 1817).

Youth with Searching Moratorium and Carefree Diffusion have less adaptive identity with low commitment as well as from high to moderate levels of rumination and indecision (Luyckx et al., 2008). In terms of the lack of mature and committed identity, this study’s results suggest that a strong future orientation can facilitate the prosocial engagement of such individuals to further exploration. Previous studies have confirmed the positive effect of time perspective interventions on enhancing goal striving, openness to future projects, career decision-making, and the career search self-efficacy of participants (Ferrari et al., 2012; Mooney et al., 2021; Park et al., 2020). Another study also proved that time perspective intervention could enhance the regular physical activity of youth (Hall & Fong, 2003). Such interventions facilitate youth’s prosocial engagement with similar planning and goal setting. However, for those with more adaptive identity statuses, such as Achievement and Foreclosure, future orientation has less effect on them because they tend to have a clear life goal and plan for their development. Youth with Diffused Diffusion have low commitment and exploration but high rumination (Luyckx et al., 2008). Due to a lack of intention for exploration and lower levels of perspective-taking under rumination, future orientation fails to motivate the youth with Diffused Diffusion to engage in prosocial activities. Assisting these youth to develop a more mature identity may be more effective in facilitating their prosocial engagement.

Previous studies have shown that group-based identity development programs help participants discuss identity issues, enhance self-understanding, and build critical thinking and problem-solving skills (Berman et al., 2008). Using participatory and empowering approaches, these programs enable individuals to identify life challenges and find effective solutions (Meca et al., 2014). Human libraries, experience sharing, discussions about life issues, and goal setting are common teaching and learning activities covered in identity interventions. These interventions help participants set goals, create pathways to achieve them, and identify potential obstacles through self-reflection and group discussions. Digital identity interventions can also be used to incorporate social media activities, such as watching career-related videos and exploring LinkedIn profiles, to support personal identity exploration and online networking (Soh et al., 2024). Identity intervention can be used to help young people develop a more mature identity and encourage their prosocial behaviour.

This paper is based on cross-sectional data, which cannot explore the relationship between identity development and prosocial trajectory. The authors will further explore how independent variables and identity status impact prosocial behaviour, as well as the relationships among these variables, by utilizing longitudinal data from various stages of the project. Future research could examine how collectivistic values interact with individualistic values to influence the prosocial behaviour of Chinese youths. This study focuses on the relationship between identity status, individualist values, future orientation, and prosocial engagement while ignoring the influence of psychological status. Previous studies revealed that personal well-being, life satisfaction, and happiness promote prosocial engagement (González Moreno & Molero Jurado, 2024; H. Zhang & Zhao, 2021; Y. Zhang, 2022), while depression inhibits prosocial behaviour in Chinese societies (Y. Zhang, 2022). Future studies can investigate whether various psychological statuses can modify the relationship among the study variables. Moreover, information was gathered through a self-reported questionnaire, which may generate response bias. Future studies can use observation or diaries to avoid this self-reported bias. This study only focuses on Chinese youth in Hong Kong, limiting the generalizability of the findings to Chinese in mainland China and youth from other ethnicities. The results show that non-local students have more prosocial behaviours than local students, although both are Chinese. Further studies can expand the sample to youth in other regions. Nevertheless, despite the above limitations, this study offers critical insight into the relationship between individualism, future orientation, identity status, and prosocial engagement in the late-modern society that emphasises collectivistic value. This study is the first to confirm the moderating role of identity status on the relationship between future orientation, vertical individualism, and prosocial engagement. This study contributes to the recent literature by filling the gap in understanding the influence of individualism in collectivist societies. The results imply that horizontal individualism is only marginally associated with prosocial engagement, while vertical individualism is unrelated to these behaviours. The results indicate that a service aimed at enhancing the identity development of youth is recommended. Time perspective intervention can be delivered to youths with Searching Moratorium and Carefree Diffusion identity, while identity intervention can be offered to youths with Diffused Diffusion identity to facilitate their prosocial engagement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.C.-f.C. and R.W.-l.C.; Formal analysis, S.-f.C. and N.X.; Data curation, S.-f.C. and N.X.; Writing—original draft, R.C.-f.C.; Writing – review & editing, H.L., C.-k.C., N.Y.-f.S., R.W.-l.C., W.-o.L. and K.Z.-m.P.; Supervision, Y.-W.C.; Project administration, H.L., Y.-W.C., S.-f.C. and N.X.; Funding acquisition, Y.-W.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China grant number [UGC/IDS(C)15/H01/19].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Hong Kong Shue Yan University (Reference No: HREC 19-05 (I01).

Informed Consent Statement

Online informed consent was obtained from the participants. Participants were required to indicate their acceptance to join this study before starting to fill in the online questionnaire. Parents of participants under 18 years old from secondary schools were also informed via email or letter. Consents from the parents of participants were obtained via the secondary schools.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise.

References

- Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolo, M. G., Palermiti, A. L., Servidio, R., & Costabile, A. (2023). “I feel good, I am a part of the community”: Social responsibility values and prosocial behaviors during adolescence, and their effects on well-being. Sustainability, 15(23), 16207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, S. L., Kennerley, R. J., & Kennerley, M. A. (2008). Promoting adult identity development: A feasibility study of a university-based identity intervention program. Identity (Mahwah, N.J.), 8(2), 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, M. W., Boardley, I. D., Benson, A. J., Wilson, K. S., Root, Z., Turnnidge, J., Sutcliffe, J., & Côté, J. (2018). Disentangling the relations between social identity and prosocial and antisocial behavior in competitive youth sport. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(5), 1113–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderón-Tena, C. O., Knight, G. P., & Carlo, G. (2011). The socialization of prosocial behavioral tendencies among Mexican American adolescents: The role of familism values. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 17(1), 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G. V., Steca, P., Zelli, A., & Capanna, C. (2005). A new scale for measuring adults’ prosocialness. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 21(2), 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona-Isaza, A. d. J., González Barrón, R., & Montoya-Castilla, I. (2023). Empathy and prosocial behavior in adolescent offenders: The mediating role of rational decisions. Sage Open, 13(4), 21582440231202844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacón, F., Vecina, M. L., & Dávila, M. C. (2007). The three-stage model of volunteers’ duration of service. Social Behavior & Personality: An International Journal, 35(5), 627–642. Available online: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=25948995&site=ehost-live (accessed on 15 August 2024).

- Chen, R. (2015). Weaving individualism into collectivism: Chinese adults’ evolving relationship and family values. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 46(2), 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.-y., & Fu, H.-Y. (2001). Between two worlds: Dynamics and integration of Western and Chinese values in Hong Kong. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras-Huerta, L. S. (2023). A cost-benefit framework for prosocial motivation—Advantages and challenges. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1170150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozma, I. (2011). How are individualism and collectivism measured? Romanian Journal of Applied Psychology, 13(1), 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Crocetti, E., Erentaitė, R., & Žukauskienė, R. (2014). Identity styles, positive youth development, and civic engagement in adolescence. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 43(11), 1818–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocetti, E., Jahromi, P., & Meeus, W. (2012). Identity and civic engagement in adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Boer, L., Klimstra, T. A., & Denissen, J. J. A. (2021). Associations between the identity domains of future plans and education, and the role of a major curricular internship on identity formation processes. Journal of Adolescence, 88, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, W., Shao, Y., Sun, B., Xie, R., Li, W., & Wang, X. (2018). How can prosocial behavior be motivated? The different roles of moral judgment, moral elevation, and moral identity among the young Chinese. Frontiers in Psychology, 9(MAY), 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, N. (1986). Altruistic emotion, cognition, and behavior. Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, N., Eggum, N. D., & Di Giunta, L. (2010). Empathy-related responding: Associations with prosocial behavior, aggression, and intergroup relations. Social Issues and Policy Review, 4(1), 143–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, L., Nota, L., & Soresi, S. (2012). Evaluation of an intervention to foster time perspective and career decidedness in a group of Italian adolescents. The Career Development Quarterly, 60(1), 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, M. A. (2008). Predictors of volunteeer time: The changing contributions of motive fulfillment and role identity. Social Behavior & Personality: An International Journal, 36(10), 1353–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, M. A. (2010). Individualism/collectivism: Implications for the volunteer process. Social Behavior & Personality: An International Journal, 38(4), 445–452. Available online: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=50332408&site=ehost-live (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Finkelstein, M. A., & Brannick, M. T. (2007). Applying theories of institutional helping to informal volunteering: Motives, role identity, and prosocial personality. Social Behavior & Personality: An International Journal, 35(1), 101–114. Available online: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=23965193&site=ehost-live (accessed on 18 May 2024).

- Flynn, E., Ehrenreich, S. E., Beron, K. J., & Underwood, M. K. (2015). Prosocial behavior: Long-term trajectories and psychosocial outcomes. Social Development, 24(3), 462–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuligni, A. J., Tseng, V., & Lam, M. (1999). Attitudes toward family obligations among American adolescents with Asian, Latin American, and European Backgrounds. Child Development, 70(4), 1030–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Moreno, A., & Molero Jurado, M. d. M. (2024). Prosocial behaviours and emotional intelligence as factors associated with healthy lifestyles and violence in adolescents. BMC Psychology, 12(1), 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, P. A. (2000). Cluster analysis. In Handbook of applied multivariate statistics and mathematical modeling (pp. 297–321). Academic Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P. A., & Fong, G. T. (2003). The effects of a brief time perspective intervention for increasing physical activity among young adults. Psychology & Health, 18(6), 685–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, S. A., Pratt, M., Pancer, S. M., Olsen, J. A., & Lawford, H. L. (2010). Community and religious involvement as contexts of identity change across late adolescence and emerging adulthood. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 35(2), 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, C. H. (1988). Measurement of individualism-collectivism. Journal of Research in Personality, 22, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, F. H. Y., Siu, A. M. H., & Shek, D. T. L. (2015). Individual and social predictors of prosocial behavior among Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 3, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laible, D., Carlo, G., Murphy, T., Augustine, M., & Roesch, S. (2014). Predicting children’s prosocial and co-operative behavior from their temperamental profiles: A person-centered approach. Social Development, 23(4), 734–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampridis, E., & Papastylianou, D. (2017). Prosocial behavioural tendencies and orientation towards individualism–collectivism of Greek young adults. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 22(3), 268–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q., & Hu, G. (2023). Positive impacts of perceived social support on prosocial behavior: The chain mediating role of moral identity and moral sensitivity. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1234977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luyckx, K., Duriez, B., Klimstra, T. A., & De Witte, H. (2010). Identity statuses in young adult employees: Prospective relations with work engagement and burnout. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77(3), 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyckx, K., Schwartz, S. J., Berzonsky, M. D., Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Smits, I., & Goossens, L. (2008). Capturing ruminative exploration: Extending the four-dimensional model of identity formation in late adolescence. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(1), 58–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyckx, K., Schwartz, S. J., Goossens, L., Beyers, W., & Missotten, L. (2011). Processes of personal identity formation and evaluation. In S. J. Schwartz, K. Luyckx, & V. L. Vignoles (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 76–98). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Main, A., Zhou, Q., Liew, J., & Lee, C. (2017). Prosocial tendencies among Chinese American children in immigrant families: Links to cultural and socio-demographic factors and psychological adjustment. Social Development, 26(1), 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maki, A., Dwyer, P. C., & Snyder, M. (2016). Time perspective and volunteerism: The importance of focusing on the future. Journal of Social Psychology, 156(3), 334–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcia, J. E. (1993). The ego identity status approach to ego identity. In J. E. Marcia, A. S. Waterman, D. R. Matteson, S. L. Archer, & J. L. Orlofsky (Eds.), Ego identity: A handbook for psychosocial research (pp. 1–21). Springer-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Marta, E., & Pozzi, M. (2008). Young people and volunteerism: A model of sustained volunteerism during the transition to adulthood. Journal of Adult Development, 15(1), 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougle, L. M., & Li, H. (2023). Service-learning in higher education and prosocial identity formation. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 52(3), 611–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meca, A., Eichas, K., Quintana, S., Maximin, B. M., Ritchie, R. A., Madrazo, V. L., Harari, G. M., & Kurtines, W. M. (2014). Reducing identity distress: Results of an identity intervention for emerging adults. Identity (Mahwah, N.J.), 14(4), 312–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeus, W., van de Schoot, R., Keijsers, L., & Branje, S. (2012). Identity statuses as developmental trajectories: A five-wave longitudinal study in early-to-middle and middle-to-late adolescents. Journal of Youth And Adolescence, 41(8), 1008–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, A., Tsotsoros, C. E., Earl, J. K., Hershey, D. A., & Mooney, C. H. (2021). Enhancing planning behavior during retirement: Effects of a time perspective based training intervention. Social Sciences, 10(8), 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancer, S. M., Pratt, M., Hunsberger, B., & Alisat, S. (2007). Community and political involvement in adolescence: What distinguishes the activists from the uninvolved? Journal of Community Psychology, 35(6), 741–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, I.-J., Rie, J., Kim, H. S., & Park, J. (2020). Effects of a future time perspective–based career intervention on career decisions. Journal of Career Development, 47(1), 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penner, L. A., Dovidio, J. F., Piliavin, J. A., & Schroeder, D. A. (2005). Prosocial behavior: Multilevel perspectives. Annual Review of Psychology, 56(1), 365–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowski, K., Brzezińska, A. I., & Luyckx, K. (2020). Adult roles as predictors of adult identity and identity commitment in Polish emerging adults: Psychosocial maturity as an intervening variable. Current Psychology, 39(6), 2149–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydell, A. M., & Brocki, K. C. (2024). Behavior problems, social relationships, and adolescents’ future orientation. Links from middle to late adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 96, 1198–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, C. E., Keyl, P. M., Marcum, J. P., & Bode, R. (2009). Helping others shows differential benefits on health and well-being for male and female teens. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10(4), 431–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S. J., Donnellan, M. B., Ravert, R. D., Luyckx, K., & Zamboanga, B. L. (2012). Identity development, personality, and well-being in adolescence and emerging adulthood: Theory, research, and recent advances. In I. B. Weiner (Ed.), Handbook of psychology. Vol. 6: Developmental psychology (Vol. 6, pp. 339–364). John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Septianto, F., & Soegianto, B. (2017). Being moral and doing good to others: Re-examining the role of emotion, judgment, and identity on prosocial behavior. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 35(2), 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singelis, T. M., Triandis, H. C., Bhawuk, D. P. S., & Gelfand, M. J. (1995). Horizontal and vertical dimensions of individualism and collectivism: A theoretical and measurement refinement. Cross-Cultural Research, 29(3), 240–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, A. M. H., Shek, D. T. L., & Lai, F. H. Y. (2012). Predictors of prosocial behavior among Chinese high school students in Hong Kong. The Scientific World Journal, 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soh, S., Cruz, B., Meca, A., & M. Harari, G. (2024). A digital identity intervention incorporating social media activities promotes identity exploration and commitment among emerging adults. Identity (Mahwah, N.J.), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strathman, A., & Joireman, J. (2005). Understanding behavior in the context of time: Theory, research, and application. Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Strathman, A., Gleicher, F., Boninger, D. S., & Edwards, C. S. (1994). The consideration of future consequences: Weighing immediate and distant outcomes of behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66(4), 742–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thielmann, I., Spadaro, G., & Balliet, D. (2020). Personality and prosocial behavior: A theoretical framework and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 146, 30–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triandis, H. C. (2001). Individualism-collectivism and personality. Journal of Personality, 69(6), 907–924. Available online: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=5487072&site=ehost-live (accessed on 12 April 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triandis, H. C., & Gelfand, M. J. (1998). Converging measurement of horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(1), 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trommsdorff, G. (1986). Future time orientation and Its relevance for development as action. In R. K. Silbereisen, K. Eyferth, & G. Rudinger (Eds.), Development as action in context: Problem behavior and normal youth development (pp. 121–136). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bos, W., Crone, E. A., Meuwese, R., & Güroğlu, B. (2018). Social network cohesion in school classes promotes prosocial behavior. PLoS ONE, 13(4), e0194656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y., Yang, C., Zhang, Y., & Hu, X. (2021). Socioeconomic status and prosocial behavior: The mediating roles of community identity and perceived control. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), 10308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterman, A. S. (1981). Individualism and interdependence. American Personality, 69, 907–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N., & Ryan, R. (2010). When helping helps: Autonomous motivation for prosocial behavior and its influence on well-being for the helper and recipient. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(2), 222–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, L., Zhang, Y. B., Kulich, S. J., & Zuo, C. (2021). Cultural values in Chinese proverbs reported by Chinese college students. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 24(2), 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentzel, K. R., & McNamara, C. C. (1999). Interpersonal relationships, emotional distress, and prosocial behavior in middle school. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 19(1), 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, M., Xiao, L., & Ye, Y. (2021). Relative deprivation and prosocial tendencies in Chinese migrant children: Testing an integrated model of perceived social support and group identity. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 658007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H., & Zhao, H. (2021). Influence of urban residents’ life satisfaction on prosocial behavioral intentions in the community: A multiple mediation model. Journal of Community Psychology, 49(2), 406–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. (2022). The role of emotions in the relationship between prosocial values and behaviors. Social Behavior and Personality, 50(9), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C., White, R. M. B., & Roche, K. M. (2022). Familism values, family assistance, and prosocial behaviors among U.S. Latinx adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 42(7), 914–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimbardo, P. G., & Boyd, J. N. (1999). Putting time in perspective: A valid reliable individual-differences metric. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 1271–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimbardo, P. G., & Sword, R. K. M. (2017). Living and loving better with time perspective therapy: Healing from the past, embracing the present, creating an ideal future. Exposit. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).