Abstract

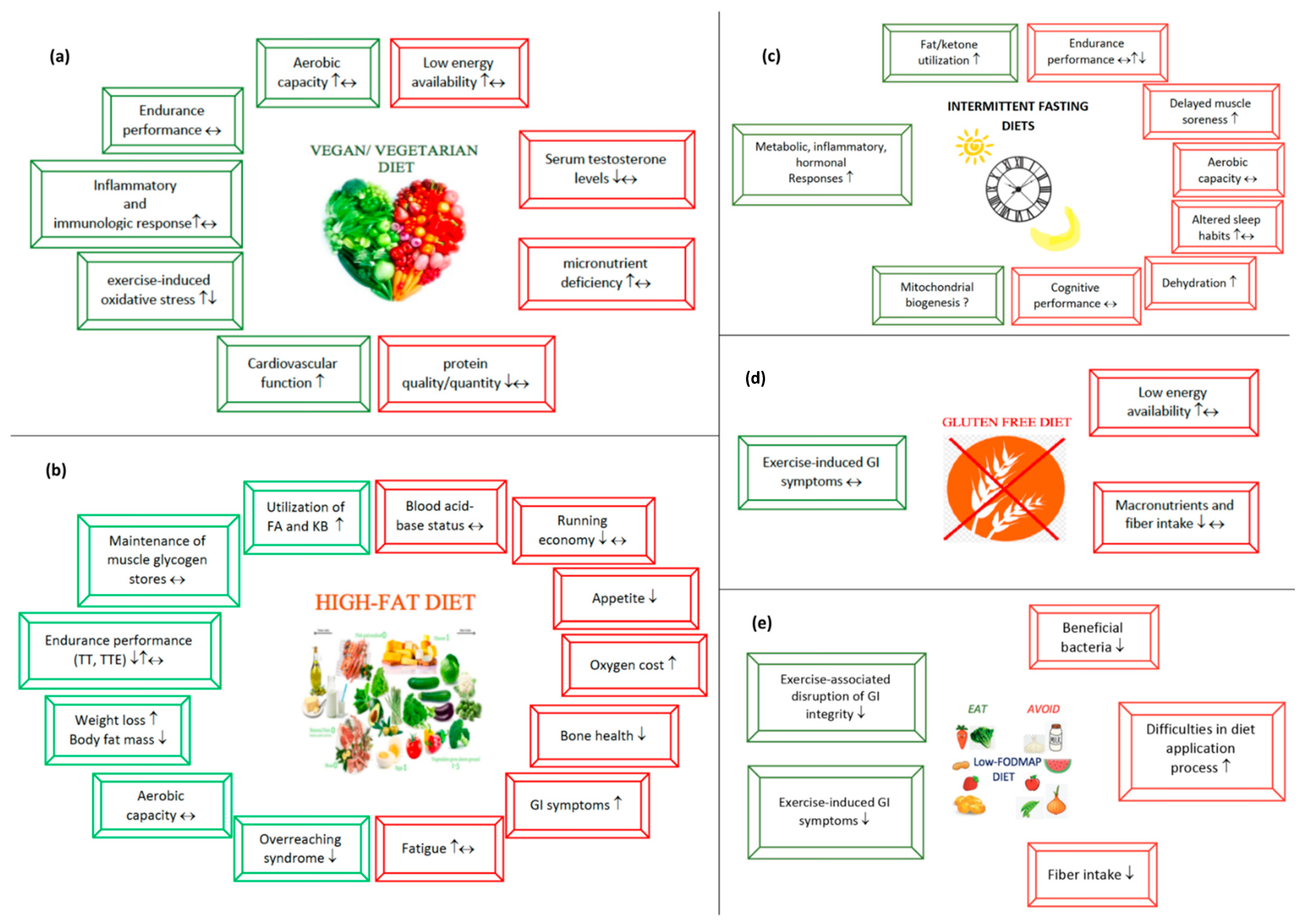

Endurance athletes need a regular and well-detailed nutrition program in order to fill their energy stores before training/racing, to provide nutritional support that will allow them to endure the harsh conditions during training/race, and to provide effective recovery after training/racing. Since exercise-related gastrointestinal symptoms can significantly affect performance, they also need to develop strategies to address these issues. All these factors force endurance athletes to constantly seek a better nutritional strategy. Therefore, several new dietary approaches have gained interest among endurance athletes in recent decades. This review provides a current perspective to five popular diet approaches: (a) vegetarian diets, (b) high-fat diets, (c) intermittent fasting diets, (d) gluten-free diet, and (e) low fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAP) diets. We reviewed scientific studies published from 1983 to January 2021 investigating the impact of these popular diets on the endurance performance and health aspects of endurance athletes. We also discuss all the beneficial and harmful aspects of these diets, and offer key suggestions for endurance athletes to consider when following these diets.

1. Introduction

Endurance performance, especially prolonged training, requires greater metabolic and nutritional demands from athletes [1]. As endurance athletes face harsh conditions during training periods, they seek alternative dietary strategies to improve endurance performance and metabolic health [2]. It is of paramount importance that a popular diet should be scientifically proven before being adopted in the athletic population [3]. Vegetarian diets [4], high-fat diets (HFD) [5], intermittent fasting (IF) diets [6], gluten-free diet (GFD) [7] and low fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAP) diets [8] are very popular among endurance athletes. In this review, we will discuss both the beneficial and harmful aspects of these diets on metabolic health and endurance performance.

2. Methods

We searched both the PubMed and Cochrane databases for the terms “diet*”, “track-and-field”, “runner*”, “marathoner*”, “cyclist”, “cycling”, “triathlete”, “endurance”, and “endurance athletes” in the title, abstract, and keywords to detect the most applied diets between 2015 and 2021 in endurance athletes. We obtained 217 results in PubMed and 80 trials in the Cochrane database. We defined the most recurrent diets in endurance athletes, including “High CHO availability”, “High-carbohydrate diet”, “Ketogenic diet”, “Low-CHO diet”, “Low-CHO, high-fat diet”, “Ketogenic low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet”, “Low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet”, “Low-carbohydrate, high fat, ketogenic diet”, “High-fat, low carbohydrate diet”, “Ketone ester supplementation”, “time-restrictive eating”, “Ketone supplementation”, “Intermittent fasting”, “fasting during Ramadan”, “Vegan diet”, “Lacto-Ovo vegetarian diet”, “Vegetarian diet”, “Low fermentable oligo-, di-, monosaccharide, and polyol diet”, and “Gluten-free diet”. Since we all know that high-carbohydrate diet is already well proven to enhance endurance performance [2], we targeted other diets for in-depth investigation by categorizing them as “vegan/vegetarian diets”, “high-fat diets”, “intermittent fasting”, “low-FODMAP diet, and “gluten-free diet”. We included studies on endurance athletes and popular diets, including vegetarian diets, high-fat diets, intermittent fasting, gluten-free diet, and low-FODMAP diet. Using PubMed, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science databases, we aimed to identify studies on races and endurance training. Two researchers (A.D.L and L.H.) independently reviewed the literature. In cases of conflict, a third investigator (B.K.) resolved the disagreement. We identified the studies published from 1983 to 2021. To define the studies on endurance athletes and diets to be included in the current narrative review, we searched MeSH terms ((“Diet, Ketogenic” (Majr); “Diet, High-Fat” (Majr); “Diet, Carbohydrate-Restricted” (Majr); “Ketone Bodies” (Majr); “Diet, Vegetarian” (Majr); “Diet, Vegan” (Majr); “Fasting” (Majr); “Diet, Gluten-Free” (Majr); “athletes” (Majr); “physical endurance” (Majr); “Diet Therapy” (Majr); “ Oligosaccharides” (Majr), “Disaccharides” (Majr)) and MeSH terms found below this term in the MeSH hierarchy recommended by PubMed and Cochrane Library. We also searched by adding the terms “FODMAP diet”, “low-FODMAP diet”, “FODMAP*”, “Fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides and polyols”, “Fermentable, poorly absorbed, short chain carbohydrates”, “Inulin”, “Xylitol”, “Mannitol”, “Maltitol”, “Isomalt”, “Fructose”, “Fructans”, “Galactooligosaccharides”, “fructooligosaccharides”, and “Polyols” to all databases, as no MeSH terms for the low-FODMAP diet were defined. We discussed the findings after determining the clinical and practical relevance of the studies by considering only human studies. We included studies available in English clearly describing the applied diet and investigating the effect of diet on endurance athletes as the primary goal. In addition, we included studies where diets were applied according to the dietary description. We excluded studies not explicitly addressing the impact of the diet on endurance performance or health-related parameters, that were not written in English, and were conducted on animals or in vitro. Based on our inclusion and exclusion criteria, we identified 57 research articles (Table 1). We organized the narrative review by considering both the beneficial and detrimental aspects of all five diets for endurance athletes.

Table 1.

Studies investigating the potential effects of vegetarian, fasting, high-fat, gluten-free, and low-FODMAP diets on athletes’ endurance performance.

3. Popular Diets Applied to Improve Sports Performance in Endurance Athletes

3.1. Vegetarian Diets

Worldwide, it is estimated that around four billion people follow vegetarian diets [9]. In addition to many books and documentaries on vegetarian diets along with various types of practice (Table 1) and many well-known athletes who have adopted vegan diets and improved their performance [10], vegan diets have become more acceptable and feasible in the athletic population [11]. Looking at the athletic population, using a survey-based study conducted with 422 marathon runners, approximately 10% (n = 39) of the athletes consumed vegetarian/vegan/pescatarian diets [12]. However, in the NURMI study, the authors used the prevalence of vegetarian diets in ultra-endurance runners, primarily living in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland [13]. The findings revealed that the ratio of vegetarian and vegan athletes was 18.4% and 37.1%, respectively.

The Impact of Vegetarian Diets on Sports Performance

Benefits of Vegetarian Diets

With the growing popularity of vegetarian diets in the athletic population, researchers have begun to investigate the role of these diets in sports performance and metabolic profile [71].

Studies on vegetarian diets have suggested that these diets may improve endurance performance by increasing exercise capacity and performance, modulating exercise-induced oxidative stress [72], inflammatory processes including anti-inflammatory and immunologic responses [4], and upper-respiratory tract infections (URTI) [73], and providing better cardiovascular function [59].

Studies measuring the aerobic capacity of vegetarian and omnivorous athletes reported controversial results [54,56,58,59]. Two studies showed that VO2max values were higher in vegetarian athletes compared to omnivore athletes [56,59], while a crossover study showed no difference between the groups [54]. Studies supported higher VO2max values in vegetarians designed as a case study and two cross-sectional studies [56,58,59], which are considered as the lowest level of the etiology hierarchy. A cross-sectional study in amateur runners reported that vegetarian female athletes had higher VO2max values than omnivorous female athletes; however, no difference was observed in VO2max values between vegetarian and omnivorous male athletes [58]. We need more high-level studies on the interaction between VO2max and vegetarian diet patterns in endurance athletes.

The availability of studies on vegetarian endurance athletes supports neither a positive nor a negative impact on exercise capacity [52,56]. Comparing the exercise capacity of lacto-ovo-vegetarian, vegan and omnivorous athletes, Nebl et al. [52] measured maximum power output (Pmax) during incremental exercise as the primary outcome of the study in determining exercise capacity, while maximum power output per lean body weight (PmaxLBW), blood lactate and glucose concentration during incremental exercise were evaluated as secondary outcomes. No differences were detected in Pmax, PmaxLBW, blood lactate and glucose concentrations between groups during increased exercise, suggesting that there was no difference in exercise capacity compared to the lacto-ovo-vegetarian (LOV), vegan or omnivorous diet pattern in endurance athletes [52]. In addition, a case study by Leischik and Spelsberg [56] assessed the exercise performance, cardiac status, and nutritional biomarkers of a male vegan ultra-triathlete and a control group of 10 Ironman triathletes during a Triple Iron ultra-triathlon (11.4 km swimming, 540 km cycling, and 126 km running). Apart from a mild thrombopenia with no pathological consequences in laboratory parameters, the vegan athlete did not have weakened nutritional biomarkers or impaired health symptoms. Additionally, the VO2max value of the vegan athlete was greater compared to the omnivorous athletes. Systolic and diastolic functions also did not differ between vegan and omnivorous athletes. The findings indicate that a well-planned vegan diet can provide adequate nutritional support for an ultra-triathlete [56].

In addition to these aforementioned benefits, vegetarian diets may also provide advantages for exercise capacity by increasing muscle glycogen levels [71], and delaying fatigue [74]. As for increasing glycogen stores, carbohydrate intake is considered the cornerstone of a better endurance performance by enhancing muscle glycogen stores, delaying fatigue, and providing athletes to compete at better and higher levels during prolonged periods [75]. Given the fact that the vegetarian diets are rich in carbohydrates (CHO) [71], such diets may offer more opportunities when considering races or training that can last at least six hours [2]. However, these data bring us to the point where foods high in CHO rather than diet types may be responsible for better performance. Taken together, both studies have shown that vegetarian diets neither benefit nor harm exercise capacity and endurance performance compared to omnivorous athletes. However, more studies are needed due to the small number of studies on the topic.

Studies have shown that the beneficial effects of vegetarian diets in alleviating oxidative stress and regulating the anti-inflammatory response are based on their enormous non-nutrient content called phytochemicals [4,76]. Polyphenols containing flavonoids, phenolic acids, lignans, and stilbenes are the most diverse non-nutrient group of phytochemicals that are produced as secondary metabolites throughout plants and have a broad spectrum of effects on metabolic health [77]. Polyphenol research of the athletic population has often been conducted using various fruits and vegetables, mainly berries [78], including blueberries [79,80,81,82], black currant [83], Montgomery cherry [84,85], and pomegranate [86]. Acute polyphenol intake or supplementation of ~300 mg 1–2 h before training or >1000 mg of polyphenol supplementation (equivalent to 450 g blueberries, 120 g blackcurrants or 300 g Montmorency cherries) 3 to more days (1–6 weeks) before and immediately after training is recommended as a countermeasure to improve antioxidant and anti-inflammatory response mechanisms [87]. However, only two studies examined the effect of vegetarian diets on exercise-induced oxidative stress in endurance athletes by comparing them with omnivorous diets, revealing contradictory results [53,55]. An incremental exercise test was applied in both studies. Nebl et al. [53] showed that nitric oxide levels, also known as an important biomarker for inflammation, endothelial and vascular function, did not alter between groups. In addition, exercise-induced malondialdehyde (MDA) concentration, an end product of lipid-peroxidation that is commonly measured to detect oxidative stress, significantly increased in vegan athletes in both studies, and in LOV athletes compared to omnivorous athletes [53]. Further, Potthast et al. [55] found a negative interaction between MDA, and sirtuin activities and antioxidant intakes such as ascorbate and tocopherol. These studies showed opposite results, against expectations, i.e., vegetarian diets increased the antioxidant response while suppressing the oxidant response. One explanation might be that the MDA test may not provide accurate measurement in biological samples due to its high reactivity and cross-reactions with other biochemicals available in the body despite its widely usage as an oxidative stress biomarker [88]. Therefore, studies with a greater sample size and including other oxidant parameters are needed to clarify these findings.

In addition to polyphenols, Interleukin 6 (IL-6) has often been identified as an inflammatory biomarker associated with fatigue, skeletal muscle inflammation, and differentiation of immune response, as well as an inducer of the metabolic acute phase response to infection [4,89,90,91]. It has been suggested that endurance athletes consuming vegetarian diets may have lower IL-6 concentrations and a lower IL-6 increase in response to endurance performance [4]. These data are explained by the positive interaction between muscle glycogen and IL-6 concentration, based on the information that higher muscle glycogen stores cause lower IL-6 elevations [92]. The higher CHO content of vegetarian diets may increase muscle glycogen stores, resulting in a down-regulated IL-6 response to endurance performance [4]. However, there are no data comparing the vegetarian and omnivorous diets for IL-6 concentration in endurance athletes.

One further point is the possible roles of vegetarian diets in URTI [73]. It is well known that endurance athletes are at greater risk for URTI due to prolonged and excessive training or races that cause immunosuppression and immune deficiency [93]. The possible link between URTI and a vegetarian diet may be explained with an emphasis on its polyphenolic content [94]. Polyphenol supplementation is also preferred in endurance athletes because of its debilitating role in URTI, one of the risk factors that often arise after immunosuppressive endurance exercise. A meta-analysis by Somerville et al. [73] reported that flavonoid supplementation reduced the incidence of URTI by 33% compared to a control group. Researchers also examined all factors that may cause a bias between studies, indicating that the risks for sequence generation, allocation concealment, and reporting bias are unclear in the included studies in the systematic review [73]. On the other hand, in a crossover design, Richter et al. [54] compared the influence of a 6 week LOV diet versus a meat-rich Western diet on in vitro measurements of immunologic parameters in male endurance athletes. The findings reported that no change was detected in CD3+ (pan T-cells), CD8+ (mainly T suppressor cells), CD4+ (mainly T helper cells), CD16+ (natural killer cells), CD14+ (monocytes) after the two diet trials and none of the immunological parameters differed from each other after the two diets. Studies have commonly focused more on diet content rather than diet pattern whether vegetarian or omnivorous. Therefore, the potential immunological benefits of vegetarian diets need to be investigated further.

A review investigating the effect of vegetarian diets on cardiovascular health in endurance athletes highlighted that vegetarian diets can provide better cardiovascular protection by reducing plasma lipid levels, exercise-induced oxidative stress, inflammation and blood pressure, and improving endothelial function and arterial flexibility [71]. One cross-sectional study confirmed the information by investigating the difference in heart morphology and function according to the vegan and omnivorous diets in amateur runners [59]. The results showed that vegans had better systolic function, determined by longitudinal strain (vegan:−20.5% vs. omnivore:−19.6%), and diastolic function in vegans, determined by higher E-wave velocities (87 cm/s vs. 78 cm/s), compared to omnivorous athletes [59]. Therefore, we can confirm that vegetarian diets may have a beneficial impact on cardiovascular function; however, we still need further investigation on endurance athletes.

Potential Risks of Vegetarian/Vegan Diets

Vegetarian and vegan diets offer several beneficial privileges for athletic populations [9,71]. However, the underlying mechanisms linking vegetarian diets to metabolic processes that may lead to undesirable effects on sports performance and, more importantly, metabolic health, should be considered beyond their beneficial functions [95]. In cases where athletes follow a vegetarian diet, issues related to the micronutrient deficiency, diet’s energy availability [96], relative energy deficiency syndrome (RED-S) [11], serum hormones [97,98], and protein quality/quantity [99,100] are topics that need to be addressed first.

Athletes who adhere to vegetarian diets are considered at high risk for deficiency of certain nutrients, especially when their dietary composition is not well-structured [10]. These risks are mainly due to the restriction of some food groups with a high nutrient density such as milk, meat, and eggs, the inability to access vegetarian foods when needed, or the development of early satiety and loss of appetite due to the high fiber content of vegetarian foods [95,101]. Furthermore, due to these dietary restrictions, athletes are at a higher risk for several micronutrient deficiencies including omega-3, iron, zinc, iodine, calcium, vitamin D, and vitamin B12 [101].

Nebl et al. [102] investigated the food consumption of vegan, lacto-ovo-vegetarian (LOV) and omnivorous (OMN) athletes according to the intake recommendations of the German, Austrian, and Swiss Nutrition Societies for the general population. Most athletes did not reach the recommended energy intake. Although omnivorous athletes consumed lower CHO compared to the recommended intake, vegetarian athletes consumed adequate amounts. For micronutrient intake, vegans achieved adequate iron levels by consuming only foods high in iron, while female LOV and OMN athletes achieved the recommended amount after supplementation. The results showed that all groups consumed enough of most nutrients. However, an analysis of the circulating state of nutrients is also needed to better interpret the effectiveness of dietary intake, particularly for vegetarian athletes [102]. A cross-sectional study by the same researchers [103] then compared the micronutrient consumption of LOV, vegan, and omnivorous recreational runners and found that 80% of each group had adequate vitamin B12 and vitamin D levels, and these parameters were higher in supplement users. Red blood cell folate exceeded the reference range; however, there was no difference in red blood cell folate among all groups [103]. No iron deficiency anemia was detected in any group, and less than 30% of each group were found to have depleted iron stores. The results suggest that a well-planned vegetarian diet can meet the athlete’s iron, vitamin D, and vitamin B12 needs [103]. These findings have been confirmed in case reports on vegan mountain bikers and ultra-triathletes [56,57]. Additionally, vegetarian diets are often inferior in quality compared to omnivores; this is due to anti-nutritional factors such as trypsin inhibitors, phytate, and tannins in those rich in vegetarian diets [104]. However, these challenges can be overcome by applying pre-cooking techniques described in detail in another review [105]. Therefore, it is obvious that vegetarian diets require careful monitoring in endurance athletes whose energy, macro and micronutrient needs are higher than their omnivore counterparts. However, with a well-planned diet and close monitoring, the nutritional needs of athletes can be successfully met, even ultra-endurance athletes.

Various metabolic risks such as iron deficiency anemia, menstrual disorders, musculoskeletal injuries, immunity, and hormonal irregularities occur in endurance athletes as a result of insufficient energy and nutrient intake following high-intensity endurance performance [106,107]. Relative energy deficiency syndrome has been found more often in vegetarian athletes, which causes endocrine and eating disorders that cause harmful diseases to metabolic health, reduces bone mineral density, and causes menstrual dysfunction [108,109]. Relative energy deficiency syndrome was developed to replace the Female Athlete Triad by broadening the definition to include male athletes and impaired physiological function caused by relative energy deficiency [109]. The key etiological factor of RED-S is a low energy availability which results in, but is not limited to, impairments of metabolic rate, menstrual function, bone health, immunity, protein synthesis and cardiovascular health [109]. In a study, researchers attribute this to either vegetarians’ food choices for low-energy-dense, high-fiber foods, even in high-energy situations, or restricted food intake behaviors by indicating dietary rules to mask vegetarians’ eating disorders [110]. Since low energy availability has already presented a challenging problem for endurance athletes independent of the diet pattern [111] and even healthy endurance athletes often cannot fully meet their body energy and vitamin requirements [112], nutritional adequacy and the quality of vegetarian diets are often questioned. However, studies examining the nutritional efficiency of vegetarian diets claimed the opposite results. Examining the diet adequacy and performance parameters of a vegan ultra-triathlete with 10 Ironman counterparts, a case report has revealed that a vegan athlete has no nutritional deficiencies or health disorders [56]. Researchers examined the spiroergometric, echocardiographic, or hematological parameters of a vegan ultra-endurance triathlete that has been vegetarian for 22 years and vegan for the past nine years. It has been found that a long-term vegetarian diet is not detrimental to metabolic health for a long-distance triathlete, even at micronutrient parameters associated with anemia. Although being a vegan athlete who consumes a well-planned diet does not have a detrimental impact in terms of cardiometabolic health and sports performance [56], findings need to be explored with a larger athletic cohort. These findings are similar to those of Wirnitzer et al. [57], who evaluated the food intake of a vegan mountain biker in the Transalp Challenge race (42 h). The researchers have highlighted that a carefully planned vegan diet strategy ensures that the race goals are achieved, and thus the race is completed in a healthy state [57]. Therefore, a well-planned vegan diet can be a great alternative for ultra-endurance athletes who endure extreme conditions such as psychological, physiological, endocrinological, and immunological stress-related metabolic challenges during prolonged training periods. In the last statement by the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics on vegetarian diets, it was stated that vegetarian diets seemed more sustainable for all stages of life [113]. Researchers have suggested that well-planned vegetarian and vegan diets containing certain micronutrients such as high-quality plant protein, iron, n-3 fatty acids, Zn, Ca, iodine, vitamin B12, and vitamin D provide various health benefits regarding diseases such as hypertension, ischemic heart disease, diabetes and obesity [113]. In addition, given the content of vegetarian diets that can contain milk, eggs, or fish, vegetarian diets may be a better option for providing better nutritional density and quality than a vegan diet [99]. It is recommended that vegans carefully monitor blood vitamin B12 concentrations and supplement their diets, if necessary, with supplements or fortified foods [113]. Vegetarian and vegan nutrition programs should be planned by considering the above-mentioned data.

For many years, there have been claims that vegetarian diets negatively affect serum sex hormones [97,98], but data on the interaction between serum sex hormones and vegetarian diets remain controversial. In a crossover study conducted in 1992, Raben et al. [114] studied the effects of a 6 week lacto-ovo-vegetarian and omnivorous diet on serum sex hormones and endurance performance in eight endurance athletes. Although endurance performance did not differ according to the diet model, serum testosterone levels slightly decreased after six weeks of consuming a lacto-ovo- vegetarian diet. The researchers stated that these results may be related to dietary fiber binding to sex hormones and higher fiber intake in the lacto-ovo-vegetarian diet [114]. Considering the evidence in the literature that testosterone triggers muscle protein anabolism and lean body mass [115], a decrease in testosterone levels would cause an undesirable situation. However, a recent study in men from the national health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES) database, but not on athletes, found that a vegetarian diet did not link to serum testosterone levels [116]. Along with all data, the interpretation of the vegetarian diet as an attenuating factor to sex hormones by disregarding other confounding factors such as age, gender, training intensity, and emotional stress would be inappropriate [116] and needs further investigation.

The issue of the protein quality and quantity of vegetarian diets has long been controversial [99,117]. While some researchers note that vegetarian proteins have some missing specific amino acids [118], others state that including high-quality protein-rich foods such as legumes, seeds, nuts, and grains in a vegetarian diet is sufficient to meet the body’s amino acid requirement [119]. A vegan diet structure should be created by examining the protein content of the food consumed, especially in terms of quality and quantity. Determining the dietary protein quality using the Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS) method in omnivore and vegetarian athletes, Ciuris et al. [100] analyzed the diet content of 38 omnivore- and 22 vegetarian athletes. Vegetarian athletes had significantly lower lean body mass (LBM) compared to omnivores (−14%). Available protein was significantly correlated with strength (r = 0.314) and LBM (r = 0.541). The main findings revealed that vegetarian athletes needed to consume an additional 10 g of protein per day to achieve the recommended protein intake of 1.2 g·kg−1 body weight (BW) and an additional 22 g of protein to reach 1.4 g·kg−1·kg−1 BW [100]. Data on vegetarian proteins such as hemp, soy, potato, and rice proteins highlight that these vegetarian proteins contain sufficient high-quality protein content to increase muscle protein synthesis and post-workout recovery [119]. Rogerson [10] suggested that vegan athletes could improve their protein intake towards the higher limit of the International Society Of Sports Nutrition’s (ISSN) protein recommendation for athletes up to 2.0 g·kg−1 body mass per day. However, given that there is little evidence in the literature that vegetarian proteins are inadequate to provide an athlete’s needs or that vegetarian athletes need a higher protein intake [11,117], this recommendation needs further clarification with clinical research.

Additionally, the potential benefits of vegetarian diets are often attributed to their polyphenolic contents [4]. The intake of polyphenols with food may be the best choice for regulating body hormesis in the case of antioxidants due to the fact that polyphenol supplements may compromise the body’s antioxidant defense metabolism [87,120]. However, at this point, the bioavailability of polyphenols taken with food comes into question [121]. While some researchers have suggested that the recommended polyphenol intake can be achieved by consuming polyphenol-rich foods or as a polyphenol supplement [122], others claimed that some polyphenols, such as quercetin, cannot be taken naturally with food [123]. Keeping all this in mind, it is necessary to further clarify the possible mechanisms for how the bioavailability of polyphenols in the body and their effects on sports performance change with their consumption naturally.

With all the data obtained from studies, there is currently no certain evidence that omnivorous or vegetarian diets provide better metabolic health and performance benefits [52,53,55,56,57,59]. Therefore, more research is needed to clarify the optimal dietary recommendations for macro and micronutrients, as well as polyphenols, to maintain health and improve performance in endurance athletes following vegetarian diets.

3.2. High-Fat Diets

High-fat diets (HFD) have been widely applied for decades as a treatment option for certain diseases such as epilepsy or as an effective dietary strategy for weight loss [124]. In recent years, these diets have also become widespread in endurance athletes [14,15,16,17,18,19,21,22,23,24,38]. High-fat diets applied in the athletic population are grouped under two main categories: (1) a ketogenic low-CHO high-fat (K-LCHF) diet, and (2) non-ketogenic high-fat (NK-LCHF) diet (described in Table 2). While a ketogenic diet aims to increase blood ketone levels from 0.5 to 3.0 mmol/L, non-ketogenic diets aim to provide potential benefits without reaching higher blood ketone concentrations. Ketosis is considered as a survival mechanism for the body to equilibrate blood glucose during a metabolic crisis, such as a lack of calories or glucose, in fasting conditions, or prolonged exercise and to provide energy to the brain, whose survival depends on ketone body (KB) utilization in case of glucose deprivation [125].

Table 2.

Types and application processes of new diets applied by endurance athletes.

In HFD studies on endurance athletes, K-LCHF diets have been commonly applied for diet periods ranging from three to 12 weeks [16,17,18,19,21,22,23,38]. Two studies, a case report (a 10 week K-LCHF diet) [21] and a cross-sectional study (a 20-month K-LCHF diet) [24], examined the effects of longer-term ketogenic diets on performance. For NK-LCHF diets, three studies, two crossover (a 2 week NK-LCHF diet) [26,28] and a cross-sectional (6-mth NK-LCHF diet) study [27], also investigated the impact of NK-LCHF diets on performance and lipoprotein profiles in endurance athletes (Detailed in Table 1). Besides these ketogenic diet applications, acute [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39] or long-term [130] administration of KBs (in a ketone ester (KE) or ketone salt (KS) form) and CHO restoration following keto-adaptation [26,40,41,42,43,45,46,47] have also been evaluated in endurance athletes. Additionally, studies have been conducted to investigate the effects of an acute pre-exercise high-fat meal [51], and a short-term (1.5 days) fat supplementation during high-CHO diet administration [49,50]. In this section, we will discuss these high-fat studies in detail, with all their beneficial and harmful consequences for endurance athletes.

3.2.1. Potential Beneficial Aspects of High-Fat Diets

High-fat diet administration has taken place in endurance athletes with the aim of improving the utilization of fatty acids and KB [14,19,20,24,25,26,28,32,33,34,35,36,41,42,43,45,46,47,49,50,51], sparing muscle glycogen stores [24,37,42,44,46,47], increasing weight loss, especially body fat mass [14,19,21,28], improving aerobic capacity [28], improving time to exhaustion [26,51] and time-trial performance [33,46,131], regulating performance-related parameters [34,36,39], increasing cognitive performance [38], regulating exercise-associated immunologic and hormonal response [15,22,30], increasing cellular gene expression [132], and attenuating overreaching syndrome [130].

One of the main goals of applying a high-fat diet to improve performance is to increase the body’s ability to use KB and fatty acids as an energy source [14,19,20,24,25,26,28,32,33,34,35,36,41,42,43,45,46,47,49,50,51]. The enhancement of the body’s ability to use KB as an energy source generally occurs in two type manipulations: (1) By restricting dietary CHO intake for a prolonged time, the body adapts metabolically to using KB instead of glucose; this process is called keto-adaptation [24]. (2) Acute KB supplementation instantly changes fuel usage from CHO to KB [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,130].

Improvement of fat utilization to fuel, especially during prolonged exercise, may provide advantages for endurance athletes, including the glucose-sparing effect that, in particular, has vital importance for the brain during times of glucose depletion [133]. While the intramuscular triglyceride stores are predominantly preferred to provide energy during low- to moderate-intensity exercise (50–75% VO2max), in moderate to vigorous-intensity exercises (>75% VO2max), muscle glycogen is used as the primary substrate to obtain energy provisions [134]. However, since the substrate utilization highly depends on the diet pattern, keto-adaptation results in a shift from glycogen to FFA or KBs, even during high-intensity exercises [21]. A number of studies such as K-LCHF [14,15,19,20,21,24,25] and NK-LCHF trials [26,28], acute KB administration [32,33,34,35,36,39], keto-adaptation followed by CHO loading [41,42,43,46], and pre-workout HF meal administration [51] proved that fat oxidation significantly increased at rest and during exercise after HFD applications. Only studies practicing the short-term fat administration during high-CHO diet administration in trained male cyclists revealed that overall fat oxidation did not alter during prolonged exercise and during submaximal or one hour time-trial (TT) exercise training [49,50]. However, one of the studies noted that fat oxidation significantly increased regardless of diet [50], while another highlighted that intramyocellular lipid utilization increased 3-fold in the fat supplemented group [49]. Taking all studies together, it seems that all applications aiming to increase fat ingestion provide better fat and KB utilization in the body, especially during exercise. This metabolic advantage appears to be unique for enhancing endurance performance.

However, along with the changes in substrate utilization towards fatty acids and KBs, KD might not be advantageous for exercise that highly relies on anaerobic metabolism and requires glucose flux such as short-duration exercise or long-duration exercise with interval sprints. In a randomized, crossover study in trained endurance athletes, it was stated that a 5 day fat adaptation followed by 1 day CHO restoration caused a decrease in glycogenolysis and PDH activation [47]. The findings suggested that this dietary manipulation could result in an increase in the NADH/NAD+ ratio or the Acetyl-CoA/CoA ratio, which could result in sustained attenuation of PDH activity and impaired glycolysis metabolism. Further research should be elucidated on the possible interaction between impaired glycolysis metabolism and ketogenic diets on prolonged exercise with anaerobic metabolism or high-intensity intermittent exercise.

As it is well known that depleting glycogen stores is one of the major causes of fatigue during endurance exercise [2], HFD also aims to reduce muscle glycogen utilization to ensure CHO availability for longer periods of time during endurance training. Although one study on endurance-trained male cyclists showed that muscle glycogen utilization significantly decreased after a 10 day fat adaptation followed by 3 day CHO restoration trial compared to a high-CHO trial [46], others investigating muscle glycogen utilization claimed that no difference was observed between the intervention and the control trial [24,37,42,47]. In addition, a cross-sectional study on male endurance runners stated that muscle glycogen utilization did not alter after an average of a 20-month K-LCHF or high-carbohydrate (high-CHO) diet. Therefore, studies on HFD and its “muscle glycogen sparing effect” remain controversial. We cannot conclude that HFD provides an advantage to spare muscle glycogen during endurance training. Further work is needed to assess muscle glycogen utilization.

K-LCHF diets might be an effective option for athletes who aim to lose body weight (BW) and body fat while sparing muscle mass [14,19,21,28]. A crossover study assessing the effects of a long-term (4 week) K-LCHF diet rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids on aerobic performance and exercise metabolism in trained off-road cyclists revealed that BW and body fat percentage decreased after long-term KD [28]. It was also stated that the long-term K-LCHF diet improved maximum oxygen consumption and decreased post-exercise muscle damage. The findings suggest that a long-term K-LCHF diet may provide advantages to both body composition and endurance performance. However, another study claimed that long-term KD (for 12 weeks) caused a decrease in both body fat percentage (5.2%) and body mass (5.9 kg) in endurance-trained athletes [14]. However, results also showed that although long-term KD resulted in improved body composition, it had no impact on 100 km TT performance. Consistent with this study, Heatherly et al. [19] investigated the impact of a 3 week ad libitum ketogenic diet on markers of endurance performance in recreationally competitive male runners. Results showed that the body composition of subjects positively changed with a decrease of ~2.5 kg BW and skinfold thickness occurring at multiple sites in the trunk region. However, KD did not affect exercise-induced cardiorespiratory, thermoregulatory, and perceptional responses and 5 km TT performance, and perceived exertion [19]. Findings indicate that KD may be an alternative strategy for reducing fat mass regardless of endurance performance.

On the other hand, Zinn et al. [21] investigated the 10 week ketogenic diet experiences of five endurance athletes and the effects of this diet on body composition and exercise performance. Although body mass and the sum of skinfolds were reduced by an average of 4 kg and 25.9 mm, respectively, endurance athletes experienced an inability to maintain high-intensity exercises during this period [21]. These findings raised doubts about the use of KD for weight loss in endurance athletes. In addition to that, a recent study compared the efficiency of two energy-reduced (−500 kcal·day−1) diets, including a cyclical ketogenic reduction diet (CKD), defined as a high-fat low-CHO (>30 g·day−1) diet for five days, followed by a high carb diet (8–10 g/body FFM) for two days, and a nutritionally balanced reduction diet (RD), a typical diet containing 55% CHO, 15% protein, and 30% fat, on body composition and endurance performance in healthy young males [135]. Results revealed that both diets reduced body weight and body fat mass. However, while CKD-related weight loss is due to decreased body fat, body water, and lean body mass, RD leads to a reduction in body weight mainly by reducing body fat mass [135]. Among all of these findings, one should note that adherence to a weight loss diet is major factor in achieving a target that does not significantly require KD consumption.

Several studies determined the potential impact of HFD on aerobic capacity [16,17,20,23,25,28,39]. It is well known that VO2max is referred to as a gold standard method to measure aerobic fitness [136]. Therefore, studies on KD, N-KD, and acute KE ingestion in endurance athletes stated that these diet manipulations had no effect on VO2max performance [16,17,20,23,25,39], except for a 4 week KD study on off-road cyclists by Zajac et al. [28]. Studies arguing that HFD was ineffective on aerobic capacity also showed that this HFD caused a decrease [16,23] or no change [25,39] in TT performance, and no alteration in time-to-exhaustion (TTE) performance [20]. Therefore, HFD seemed to fail to increase aerobic capacity and endurance in endurance athletes.

Researchers evaluated multiple performance-related factors such as TT performance [14,19,23,25,29,33,34,35,36,38,39,41,42,43,45,46,48,49,50], TTE performance [18,20,21,26,31,37,51], lactate concentration during exercise [33,34,36,39], and post-exercise muscle damage [28] to determine the effects of HFD on sports performance. While research on TT and TTE performance in endurance athletes revealed controversial results, the majority of the studies declared that no alterations were observed in TT [14,19,25,29,34,36,38,39,41,42,43,45,49,50] and TTE [18,20,26,31,37] performance after the HF-associated applications. Additionally, two well-controlled studies of Burke et al. [16,23] underlined that a 3.5 week K-LCHF diet not only decreased 10 km race walk performance, but also increased oxygen cost and perceived exertion throughout exercise. These findings suggest that HFD has no advantage or may even negatively affect exercise performance. However, some points should be taken into account when interpreting these findings. Five of eight studies on perceived fatigue during endurance performance revealed that no differences were detected between HFD and control trials [18,19,38,39,49]. Similar results were also observed in studies on lactate concentration during exercise [34,36,39]. It seems that HFD altered neither perceived exertion nor plasma lactate concentrations. Another important point for endurance performance is the maintenance of blood glucose concentration during exercise [38]. Changes in blood glucose levels during exercise were investigated in acute KB ingestion trials [34,36,38,39]. Three of four studies indicated that blood glucose concentrations were maintained during endurance exercise and were found to be similar between control groups [34,38,39].

Although these results are promising, blood glucose changes should also be examined in studies involving HFD manipulations. Additionally, a crossover study evaluating the efficiency of a 4 week NK-LCHF diet application on off-road cyclists stated that blood CK and LDH concentration, known as muscle damage biomarkers, significantly decreased at rest and during the 105 min exercise protocol in the NK-LCHF diet trial [28]. These findings also appear promising. It should be noted that studies reporting that TT or TTE performance did not change after HFD interpreted the study results based on statistical significance. It should also be noted that, although considered as statistically insignificant, a few minutes can be crucial in winning a race. Therefore, this point should be considered when interpreting the study results. Lastly, for post-exercise recovery, Volek et al. [24] indicated that long-term (at least 6 months) LCHF diets resulted in an increased fat oxidation rate and a higher peak exercise intensity in endurance athletes compared to counterparts consuming high-CHO low-fat diets. Moreover, although the LCHF diet group consumed 10% CHO, whereas the habitual high-CHO group consumed 59% CHO, there was no difference between the LCHF and high-CHO low-fat diets for 2 h post-exercise recovery [24]. These results suggest that long-term LCHF diets can improve post-exercise recovery, especially in ultra-endurance events where the glycogen-sparing effect and adequate post-exercise recovery are crucial for a better performance. Keeping all these findings in mind, although studies on TT and TTE performance mostly found no advantages of HFD or revealed controversial results, performance-related parameters may be positively affecting the HFD. More work is required to clarify this information.

Ketone body consumption in endurance athletes may increase endurance performance by up-regulating physiological parameters and increasing metabolic efficiency [126]. For instance, Cox et al. [33] conducted comprehensive research including five separate studies on the effect of ketone esters (KE) on the performance of 39 endurance athletes. Twenty minutes after consumption of the ketone ester-based drink, blood ketone concentrations rapidly increased to 2 mmol/L and remained high with a slight drop, reaching a new steady state approximately 30 min following subsequent exercise at 75% Wmax exercise intensity. Findings from the study showed that acute nutritional ketosis caused by the consumption of KE resulted in metabolic improvements in endurance performance by enhancing metabolic flexibility and energy efficiency, rapidly altering substrate utilization towards ketone bodies for oxidative respiration, sparing intramuscular BCAA concentration by reducing BCAA deamination, increasing muscle fat oxidation even though in the presence of glycogen, and decreasing blood lactate levels during exercise [33]. On the other hand, most of the studies (6 of 10) applying acute KB intake showed that this practice did not improve TT [34,36,38,39] and TTE performance [31,37]. Study findings remain unclear, and the impact of KB on exercise performance needs further clarification.

The efficacy of HFD on cognitive performance has been investigated in studies on acute KE [39] and KS [38] administration and fat-enriched feeding during high-CHO diet administration [50]. Prins et al. [38] administered one (22.1 g) or two (44.2 g) servings of KS or placebo to recreational male distance runners 60 min before a 5 km TT performance, and noted a possible dose–response interaction between KS supplementation and cognitive performance. On the other hand, studies including acute KE administration [39] and fat-enriched feeding during high-CHO diet administration [50] showed no alteration in cognitive performance. A study applying the high-CHO diet supplemented with fat on trained male cyclists highlighted that a possible explanation for this result is that the study protocol, including 1 h of fixed-task simulated TT performance, may not be sufficient to create mental fatigue [50]. However, the study on acute KE intake found similar results despite applying an exercise protocol (1 h submaximal exercise at 65% VO2max followed by a 10 km TT) that caused more fatigue [39]. Taken together, studies did not confirm the exact efficiency of HFD on cognitive performance and the interaction needs further investigation.

Few studies investigated the potential influence of HFD on immunologic and hormonal response in endurance athletes [15,22,30]. Assessing the impact of acute (2 day) and prolonged (2 week) adherence to an K-LCHF diet on exercise-induced cortisol, serum immunoglobulin A (s-IgA) responses in a randomized, crossover manner, researchers indicated that a lower cortisol response at week 2 was observed compared to day 2 in the K-LCHF trial (669 ± 243 nmol/L vs. 822 ± 215 nmol/L, respectively) [15]. However, a better exercise-induced cortisol response was found in the HCF trial at both day 2 and week 2 (609 ± 208 nmol/L and 555 ± 173 nmol/L, respectively). Additionally, no differences in s-IgA concentrations were observed at week 2 between the K-LCHF diet and high-CHO diet [15]. Another study by Shaw et al. [30] determined the impact of acute KE supplementation (R,S-1,3-butanediol (BD); 2×0.35 mg·kg−1 BW; 30 min before and 60 min after exercise) on the T-cell-associated cytokine gene expression within stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) following prolonged, strenuous exercise in trained male cyclists. No alteration was detected in serum cortisol, total leukocyte and lymphocyte, and T-cell subset levels, IL-4 and IL-10 mRNA expression, and the IFN-γ/IL-4 mRNA expression ratio between the KE and placebo trials during exercise and recovery. However, a transient increase was observed in T-cell-related IFN-γ mRNA expression throughout exercise and recovery in the KE trial. Results indicated that acute KE supplementation may provide enhanced type-I T-cell immunity at the gene level [30]. The same researchers investigated the potential effect of a 4.5 week K-LCHF diet on resting and post-exercise immune biomarkers in endurance-trained male athletes in a randomized, repeated-measures, crossover manner [22]. T-cell-related IFN-γ mRNA expression and the IFN-γ/IL-4 mRNA expression ratio within multiantigen-stimulated PBMCs were greater in the K-LCHF trial compared to the high-CHO trial. Furthermore, a significant rise was observed in the multiantigen-stimulated whole-blood IL-10 production, an anti-inflammatory cytokine, post-exercise in the K-LCHF trial. The results indicated that a 4.5 week K-LCHF diet caused an increase in both pro- and anti-inflammatory T-cell-related cytokine response to a multiantigen in vitro [22]. Keeping the studies on immunologic and hormonal response to HFD in mind, although post-exercise pro- and anti-inflammatory T-cell-related cytokine response alters after a K-LCHF diet or acute KE supplementation, it remains uncertain how these alterations influence the immunoregulatory response. Therefore, more work is required to elucidate the interaction by adding clinical illness follow-up and tracking immunomodulatory metabolites using metabolomic approaches.

Antioxidant specialties of HFD may be discussed on the basis of KB [124]. Antioxidant activity of KBs is one of the multidimensional properties that determine their metabolic activity in the body. The main potential antioxidant properties of KB are mainly explained by its effects on neuroprotection, inhibiting lipid peroxidation and protein oxidation, and improving mitochondrial respiration [137]. However, as there is no study investigating the impact of KB on exercise-induced oxidative stress in endurance athletes and the evidence on the impact of KB on exercise-induced oxidative stress is limited, future studies in this field are needed.

Another therapeutic benefit of KD may be linked to increased Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 (FGF21) [132]. Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 acts as the primary regulator of skeletal muscle keto-adaptation by increasing activation of the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)—sirtuins 1 (SIRT1)—peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor coactivator 1 (PGC-1) pathway, resulting in increased mitochondrial biogenesis, development of IMTGs, and ketolytic gene expression [138]. However, in a study on 5-d fat adaptation followed by 1-d CHO restoration, a significant decrease was observed in the exercise-induced AMPK-1 and AMPK-2 activity in the fat-adapted trial despite the higher AMPK-1 and AMPK-2 activity before exercise. Therefore, more work is required to interpret the possible interaction accurately.

Ketone bodies may have a particular metabolic advantage, not only providing a source of oxidizable carbon to maintain energy needs but also acting as a potential regulator of overtraining by directly regulating autonomic neural output and inflammation [139,140]. One study applying three weeks of KE intake during prolonged extreme endurance training investigated the effects of KE on overreaching symptoms [130]. Ketone ester ingestion significantly increased sustainable training load (15% higher than the control group), and prevented the increase in nocturnal adrenaline and noradrenaline excretion induced by strenuous training [130]. These findings suggest that KE supplementation during exercise substantially reduces the development of overreaching, which is a detrimental factor for endurance performance. In addition, growth differentiation factor (GDF-15), an established biomarker for nutritional and cellular stress, increased 2-fold less in the KE group than the control group. However, this study was conducted on healthy, physically active males, and it is not exactly known whether the same effects can be achieved in endurance athletes [130]. For this reason, it is necessary to examine the same mechanism, especially on endurance athletes with intense and frequent training periods.

3.2.2. Potential Risks Regarding High-Fat Diets

Some researchers have also investigated HFD’s potential risks on endurance, including an increased oxygen cost and an impaired running economy [16,23], an altered blood acid-base status [17,31], compromised gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms [32,34,35,37,48], reduced bone formation markers [40], increased cholesterol and lipoprotein levels [27], a decreased appetite [37], and thereby worsened performance.

The deterioration of the running economy and increased oxygen cost during endurance exercise are considered to be major potential disadvantages of HFD. Burke et al. [16,23] demonstrated with two separate studies in elite race-walkers that a 3 week K-LCHF diet during intensity training impaired endurance performance by decreasing exercise economy, which has vital importance in endurance performance, despite enhancing peak aerobic capacity (VO2peak). Another study by Burke et al. claimed that although KD elevated glycogen availability, it still impaired endurance performance mainly by blunting the CHO oxidation rate [141]. In addition, LCHF diets can also impair endurance performance by increasing perceived fatigue [15,16,23]. The reason why K- LCHF diets cause increased fatigue is thought to be a gradual increase in non-esterified fatty acids (NEFAs) with the LCHF diet [142]. Non-esterified fatty acids compete with the tryptophan, a neurotransmitter highly associated with the central fatigue, for binding to albumin, thus resulting in an increase in free tryptophan transfer from the blood–brain barrier towards the brain. However, as we discussed above, the majority of studies found no alteration in perceived exertion during endurance performance [18,19,38,39,49].

Studies on well-trained endurance athletes revealed that neither keto-adaptation nor CHO restoration followed by keto-adaptation improves endurance performance, especially at multistage ultra-endurance events with intermittent sprints [42,45]. For instance, investigating the impact of a 6 days high-fat (68% fat) diet followed by 1 day CHO loading or high-CHO diet (68% CHO) for seven days on performance parameters during the 100 km time trial, Havemann et al. [45] found that 100 km time trial performance assessed by heart rate, perceived exertion, and muscle recruitment did not differ between groups; however, the 1-km sprint power output decreased more in the high-fat diet group than in high-CHO counterparts. Although an improvement was expected in high-intensity sprint bouts after an NK-LCHF diet due to its sparing effect on muscle glycogen, the findings revealed the opposite, decreasing the high-intensity sprint performance, a crucial parameter for endurance performance [45]. On the contrary, McSwiney et al. [14] also evaluated the impact of K-LCHF diets on 100 km TT performance and 6 s sprint peak power, indicating that although TT performance did not differ between the K-LCHF diet and high-CHO diet groups, 6 s sprint peak power significantly increased (+0.8 W·kg−1 rise) compared to the high-CHO group (−0.7 W·kg−1 decrease). More research is required to clarify these contradictory results.

Maintaining the acid-base balance in the body during exercise, especially during strenuous exercise, is important to delay acidosis and fatigue and thus to maintain endurance performance [143]. Exercise is a well-known factor that alters the acid-base state [143]. In addition to exercise, the macronutrient composition of dietary patterns can also affect acid-base balance and systemic pH and HCO3 levels [31]. Some researchers claimed that HFD can alter circulating acidity by increasing acidic KB circulation in the body [144], while others state that acid-base balance can be well regulated by improving the adaptive mechanisms, regardless of diet [17]. The potential effect of HFD on blood acid-base status, blood pH, and HCO3 concentrations was evaluated in only two studies of endurance athletes. The potential effect of HFD on blood acid-base status, blood pH, and HCO3 concentrations was evaluated in two studies, one evaluating a 3 week ketogenic diet [17] and the other an acute KE intake in endurance athletes [31]. The study findings showed that neither K-LCHF diet nor acute KE intake affected blood pH and HCO3 status and acid-base status [17,31]. One explanation is that both studies included well-trained endurance athletes. It is suggested that well-trained athletes can regulate the body acid-base balance well regardless of the diet by developing a metabolic adaptation to strenuous exercise. Therefore, the potential effect of HFD on acid-base status can be interpreted as negligible when applied to well-trained endurance athletes.

Gastrointestinal symptoms triggered by an HFD have commonly been seen during KB consumption [32,34,35,37]. A study investigating the kinetics, safety and tolerability of KB revealed that ketone esters may only cause GI symptoms when high doses (2.1 g·kg−1) are consumed [145]. However, although studies administered a low-dose KE in endurance athletes, the findings stated that acute KE ingestion caused an increase in low to severe GI symptoms, including nausea, reflux, dizziness, euphoria, and upper-abdominal discomfort [32,34,35,37]. One study by Dearlove et al. [32] compared the dose–response interaction between acute low- or high-dose KE ingestion (0.252 g·kg−1 vs. 0.75 g·kg−1, respectively) and GI symptoms. Findings showed that no GI discomfort was observed in the low-dose KE ingestion, while nausea symptoms were elevated in the high-dose KE trial. Although the high dose administered in this study (0.75 g·kg−1) remained much lower than the high dose (2.1 g·kg−1) that was claimed to cause GI symptoms, it still caused exercise-induced nausea in endurance athletes. In addition, Mujika [48] investigated the race performance and GI symptoms of a LOV male endurance athlete who adhered to an LCHF diet for 32 weeks. The athlete participated in three professional races while on the LCHF diet in weeks 21, 24, and 32. Although he suffered worse race experiences on the LCHF diet, no alteration was observed in GI symptoms. This result may be due to the athlete’s adaptation to the ketogenic diet [48]. Taken together, while long-term keto-adaptation may inhibit the increase in GI symptoms, it should be taken into account when applying to endurance athletes that acute KE intake may be disadvantageous on exercise-induced GI symptoms. Interestingly, Zinn et al. [21] showed that endurance athletes suffered from constipation during the diet application after a 10 week K-LCHF diet, which might be important for the gut microbiome and well-being. This possibility may also be kept in mind while applying a ketogenic diet. In case of a similar situation, fiber and water intake should be calculated and closely monitored to eliminate constipation-associated problems.

Another less-studied potential disadvantage of HFD is its potential impact on decreasing appetite [37], bone formation markers [40], and increasing cholesterol and lipoprotein profile [27]. A randomized, crossover study evaluating the effects of acute KE ingestion early in a cycling race on glycogen degradation in highly trained cyclists showed a significant attenuation in the perception of hunger, determined using a validated 10-point visual analog scale [37]. This potential effect of HFD on appetite should be taken into account, especially during HFD administration planned for long-term application.

Heikura et al. [40] investigated the effects of a 3.5 week K-LCHF diet followed by CHO restoration on bone biomarkers in male and female race walkers. Their findings showed a meaningful increase in bone resorption markers at rest and post-exercise while a significant attenuation in bone formation markers at rest and throughout exercise in K-LCHF diet trial occurred. However, these alterations partially recovered after CHO restoration [40]. As only one study investigated the interaction between bone markers and ketogenic diets in endurance athletes, and a recent narrative review on ketogenic diets and bone health noted that we do not have enough high-quality experimental research to adequately clarify the potential disadvantages of ketogenic diets on bone health, we need more high-quality research on this topic.

Only one cross-sectional study of 20 competitive ultra-endurance athletes investigated the interaction between a long-term low-CHO diet and the circulating lipoprotein and cholesterol profiles [27]. Although a higher level of exercise tended to lower total and LDL-C concentrations, a hypercholesterolemic profile was observed in ultra-endurance athletes who adhered to a low-CHO diet, suggesting that a possible explanation may involve an expansion of the endogenous cholesterol pool during keto-adaptation and may remain higher on a low-CHO diet. Further, a higher consumption of saturated fat (86 vs. 21 g·day−1) and cholesterol (844 vs. 251 mg·day−1), and lower fiber intake (23 vs. 57 g·day−1) may be another cause of these hypercholesterolemic profiles of ultra-endurance athletes [27]. However, due to the small sample size (n = 20) and the lack of checking for familial hypercholesterolemia or specific polymorphisms [27], future work is needed to evaluate this interaction in depth.

Another possible pathway is that KD high in protein causes an increase in ammonia, thereby altering both brain energy metabolism and neuronal pathways, thus triggering central fatigue [146]. Both NEFA and ammonia may lead to increased central fatigue during exercise in endurance athletes adopting KD [142]. The interaction between the gut–brain axis can have critical importance to reveal performance- and, especially, fatigue-related metabolism during endurance events [147]. However, none of the HFD studies on endurance athletes studied the gut–brain axis, increased ammonia concentration, or endurance performance. Another point regarding a high protein intake during KD is that a high protein consumption can disrupt ketosis by providing gluconeogenic precursors, thus inducing gluconeogenesis [148]. Therefore, moderate protein consumption is generally recommended during KDs. As we know that endurance athletes tend to consume more protein intake (1.2–2.0 g·kg−1 BW·day−1) [149], this important effect of protein on ketosis should be kept in mind during the KD administration periods.

There are some important points that need to be considered before applying an HFD in endurance athletes. During NK-LCHF diet applications, the metabolic adaptation of muscle may evolve towards oxidation of fat as the primary energy source (maximum fat oxidation rate (fat max) from 0.4–0.6 g·min−1 to 1.2–1.3 g·min−1) [139]. However, glycogen stores may not provide enough glucose to power the brain, thus increasing fatigue [150] and decreasing endurance performance. For this reason, the adaptation period should be chosen carefully in order to alleviate the side effects of transition periods. Phinney et al. [20] noted that ketogenic high-fat diets may impair performance at first (a reduction of approximately 20%), but improvements in performance (up to a 155% increase) can be observed after metabolic adaptation to the ketogenic state.

Another important point that needs to be considered while planning further studies on HFD is to evaluate blood ketone concentration at frequent intervals during the study application period [151]. A review investigating the role of ketone bodies on physical performance found that 7 out of 10 studies included in the review failed to reach BOHB concentrations at the 2 mmol/L threshold, but only caused an acute ketosis state (B-OHB > 0.5 mmol/L) [151]. Another significant point is which KB type should be used [152]. The impact of ketone bodies on metabolism differs according to the type (ester-based form or salt-based form), and optical isoform (e.g., L or D isoforms of BOHB) consumed [137]. For example, D-βOHB is produced from acetoacetate (AcAc), released by the liver, and is actively used in metabolic pathways [153], while L-OHB is an intracellular metabolite known for having less activity in oxidative metabolism [150]. Therefore, L-βOHB supplementation may not provide the performance-related benefits of ketone bodies. These results explain that the specific effect of KD or KB on physical performance awaits further investigation, as most studies of KB failed to achieve the required ketone concentrations or applied ineffective KB to enhance endurance performance [152].

To conclude, there are several HFD strategies, as discussed in detail above, practiced by endurance athletes. However, while these diets may provide performance and health benefits, they are sometimes not effective at all or create many problems for endurance athletes. In addition, the physiological response to acute (exogenous) or endogenous nutritional ketosis may vary between highly trained endurance athletes and untrained individuals [140]. Therefore, it should be noted that these strategies may not be suitable for all endurance athletes. At first glance, while high-fat diets may seem like a promising approach to endurance performance, more research is needed to keep in mind all study results.

3.3. Intermittent Fasting

Intermittent fasting (IF) is defined as a period of voluntary withdrawal from food and beverages. It is an ancient approach that is implemented in different formats by different populations around the world [154]. Intermittent fasting diets have become more prevalent in recent years, including the scientific literature investigating the metabolic interaction between IF and health, as well as in the media and among the public [127]. Intermittent fasting diets are divided into four groups: (1) complete alternate-day fasting, (2) modified fasting, (3) time-restrictive eating and (4) religious fasting such as Ramadan IF (R-IF) (explained in detail in Table 2) [127].

Intermittent Fasting and Sports Performance

Possible Benefits of Intermittent Fasting in Endurance Athletes

Studies on IF in endurance athletes have often been conducted during the religious fasting period (R-IF) [60,61,63,64], with few studies investigating the effects of time-restrictive eating (16:8) on endurance performance and health-related effects [62,65]. Fasting diets may alter metabolic pathways in the body by acting as a potential physiological stimulus for ketogenesis [155], regulating metabolic, hormonal and inflammatory responses [61], and stimulating mitochondrial biogenesis and suppressing mTOR activity [155], and regulating body composition [62,65].

Energy restriction/fasting for more than 12 to 16 h leads to a metabolic switch in basic energy fuels from carbohydrates to fats, resulting in metabolic ketosis, the same as the ketogenic diets [155]. These KD-like alterations in substrate uses are believed to serve as an inductor for fat oxidation, and a preservative for muscle mass and function [156].

The effect of fasting diets on muscle cells is generally known to be similar to aerobic exercise, including stimulation of mitochondrial biogenesis and suppression of mTOR activity [157]. However, the main mechanism on fasting diets is driven by fatty acid metabolism and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta (PPAR-d), instead of Ca2+, which is known to be effective in aerobic exercise [155]. Although the main mechanism on muscle cells differs between exercise and fasting diets, research findings suggest that application of a fasting diet along with exercise could switch cellular metabolism from glucose to ketone bodies [156], thereby inducing ketone utilization, which might, in turn, trigger mitochondrial biogenesis and preserve muscle mass [158]. Although the potential benefits of IF on mitochondrial biogenesis and mTOR activity appear promising, no study has investigated these metabolic interactions in endurance athletes adhering to IF.

The impact of R-IF on hormonal, metabolic and inflammatory responses is a less-studied point in terms of IF diets. In a study on middle-distance runners, Chennaoui et al. [61] examined the effects on R-IF on the hormonal, metabolic and inflammatory responses in a pre–post-test study design. Researchers applied a maximal aerobic velocity test 5 days before, 7 and 21 days after Ramadan. No change was observed in the testosterone/cortisol ratio during the RIF trial. A significant rise was reported in IL-6, adrenaline, and noradrenaline concentrations after the RIF; however, all parameters returned to baseline levels 7 days after exercise [61]. More work is needed to interpret these results effectively.

Another aspect of IF is its impact on the body composition of endurance athletes. Studies on endurance athletes and TRE (16:8) revealed that TRE caused a meaningful decrease in BW and body fat percentage in endurance athletes [62,65]. Moro et al. [62] claimed that although VO2max and endurance performance did not change after a 4 week TRE, a meaningful rise in the peak power output/BW ratio was due to the BW loss. However, another study showed a decrease in TT performance (−25%) and no improvement in running efficiency after R-IF in well-trained middle-distance runners [65]. Taking these studies into account, although IF may provide some benefits by decreasing BW and body fat percentage, we cannot assume that it positively affects endurance performance.

Risks to Be Considered When Applying Fasting Diets

Potential risks of IF diets are reduced endurance capacity [60], increased fatigue [61,63], altered sleep habits (i.e., delayed bedtime, decreased sleep time) [61,63,64], and dehydration [159] in endurance athletes.

Studies on IF diets and endurance capacity and performance-related parameters have produced conflicting results in endurance athletes [60,62,64]. Both R-IF and TRE studies on endurance athletes stated that IF diets had no influence on the aerobic capacity, determined by VO2max [60,62,64]. Additionally, one study on TT performance and R-IF in well-trained middle-distance runners showed that R-IF caused a decrease in TT performance [60]. However, another study determining the impact of the CHO mouth rising technique on 10 km TT performance declared that the CHO mouth rising technique provided benefits by increasing 10 km TT performance [64]. For TRE and endurance performance, Moro et al. [62] revealed that a 4 week TRE had no impact on endurance performance. As for evaluating performance-related parameters, several researchers investigated the exercise-induced fatigue, blood lactate, glucose, and insulin concentrations in endurance athletes [61,63,64,65]. Exercise-induced fatigue, as determined by the Fatigue score [61] and the Rated Perceived Exertion (RPE) Scale [63], increased after a maximum aerobic speed test and an intensive endurance training, while it decreased significantly in an R-IF trial applying mouth rising during a 10 km TT performance [64]. One TRE study also showed that blood lactate, glucose and insulin concentrations did not alter during an incremental test [65]. We know that endurance exercise lasts more than an incremental test duration. Therefore, although blood parameters were well-maintained during an incremental test, we cannot interpret the study as the parameters will be preserved during prolonged strenuous exercise. Since there are few studies on endurance performance and IF, further studies should be conducted with an exercise protocol similar to races and competitions, including all performance-related parameters.

One study assessed the effect of R-IF on cognitive function in a non-randomized, repeated-measures, experimental design manner [63]. No difference was observed in cognitive performance, measured using reaction time and mean latency times on simple and complex tasks during Ramadan in trained male cyclists. Therefore, the implementation of IF diets to increase endurance capacity, improve performance-related parameters or cognitive performance does not appear to be a well-approved strategy. On the other hand, it would be wrong to refer the IF diet as a detrimental strategy due to the controversial findings of studies. Further, a review of the role of R-IF in sports performance, which included well-controlled studies, reported that although R-IF generally affected athletic performance with a few declines in physical fitness at a modest level, including perceived exertion, feelings of fatigue, and mood fluctuations, these negative effects may not cause a decrease in sports performance [160]. Furthermore, while prolonged fasting has detrimental effects on endurance performance by decreasing endurance time and causing carbohydrate depletion, hyperthermia, and severe dehydration [161,162,163,164], IF causes preventable adverse effects on performance [160].

An important factor among the difficulties that IF can cause is the alterations in sleeping habits of endurance athletes who practice R-IF [61,63,64]. During R-IF, in contrary to other IF diets, sleeping periods alter due to the difference of fasting/feeding cycle, thereby disturbing the circadian sleep/waking rhythm [160]. These changes may trigger general fatigue, mood, and mental and physical performance in endurance athletes. A study on 8 middle-distance athletes who maintained training during Ramadan revealed that R-IF affected physical performance by disturbing sleeping habits, creating energy deficiency, and fatigue [61]. Another study on cyclists showed a significant reduction in the duration of deep and REM sleep two weeks after starting R-IF, although total sleep time was unchanged [63]. On the other hand, a study on adolescent cyclists also reported no change in total sleep time following R-IF [64]. As sleep is one of the major components for maintaining metabolic health and performance [165], during Ramadan IF, the sleep cycle of endurance athletes should be carefully monitored and effective sleep strategies should be developed for this period. Further, in order to determine the effects of Ramadan IF on sleep patterns more accurately, more objective sleep measurements should be applied.

Another adverse effect of R-IF on endurance athletes is the deterioration of hydration conditions before, during and after exercise [159]. Starting competition in euhydrated state is one of the key factors for greater performance [166]. Further, providing adequate fluid ingestion during exercise, especially prolonged strenuous training, has a major impact on body fluid homeostasis. Although glycogen breakdown provides an average of 1.2 L water [155], it is still not enough to meet the body fluid need during the marathon, especially in hot weather conditions [156]. Therefore, fasting due to lack of water/fluid consumption can create adverse health problems beyond performance detriments [146]. Although TRE diets allow the consumption of water and unsweetened coffee and tea, R-IF has restrictive rules that forbid the consumption of anything during the fasting state [127]. Therefore, the water balance and fluid strategy of endurance athletes should be carefully planned, especially for endurance athletes applying R-IF diets.

The adverse effects of the IF diets also vary according to the weather conditions during fasting, training severity, training load, and training level of athletes [159]. These factors and, more importantly, endurance athletes’ ability to cope with these metabolic changes determines how their sports performance will be during Ramadan. Evidence suggests that the performance success of athletes following an IF diet depends on their energy availability and macro and micronutrient intake, as well as training load and sleep length and quality [167]. Chennaoui et al. [61] suggested that athletes struggling with R-IF can reduce the negative effects of IF by reducing their training load and taking daytime naps.

Taking all studies into account, the efficiency of IF to improve exercise capacity and performance-related parameters still remains uncertain. Therefore, as we consistently repeat in the review, more work is needed before recommending these diets, especially in hot environments or during intense training periods. Since many Muslim athletes follow a month-long R-IF diet for religious reasons, even if there is a major competition or tournament [160], we need to develop effective strategies to maintain endurance performance and inhibit any decrease in endurance capacity during Ramadan.

3.4. Gluten-Free Diet

Exercise-induced GI symptoms in endurance athletes share common characteristics with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), including altered bowel functions (e.g., diarrhea, constipation), bloating, intestinal cramps, urge to defecate, and flatulence without any known organic disease [168]. These symptoms strongly affect the quality of life, psychological well-being, and also have quite a detrimental influence on exercise performance [1,168]. Therefore, several therapies have been developed for manipulating and attenuating these GI symptoms [169]. While drug-based treatments can be of benefit, certain foods are thought to trigger GI symptoms. In a research study, 63% of patients with IBS reported that some foods trigger their IBS symptoms [170]. Therefore, diet therapies gain more interest than other therapy options in patients with IBS and endurance athletes with GI symptoms. For example, a gluten-free diet (GFD) [128] and a low Fermentable Oligo-, Di-, Mono-saccharides, and Polyols (FODMAP) diet [171] are classified as elimination diets that both exclude or limit certain foods or nutrients that may cause undesirable GI problems such as abdominal bloating, cramps, flatulence or urge to defecate.

3.4.1. Why Do Endurance Athletes Consider a Gluten-Free Diet to Be Beneficial?

A gluten-free diet is a strict elimination diet that requires the complete exclusion of gluten, a storage protein found in wheat, rye, barley seeds, and includes gluten-free foods and food products that do not contain gluten or have a gluten content of less than 20 ppm, as per European legislation [172]. It has been used for decades as a treatment for celiac disease (CD) or to treat other gluten-related disorders that require strict gluten elimination from the diet [173]. However, recently, gluten has been considered to be an inducer that triggers the pathophysiology of various conditions. Based on this theory, endurance athletes have widely practiced GFD even if CD or non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) has not been diagnosed [7]. Although they applied GFD as a possible dietary therapy because of their belief in a diet that could improve metabolic health and performance or alleviate exercise-induced GI symptoms, the results show no significant improvement in performance with GFD in non-celiac athletes [129].