Abstract

Disasters are uncertain occasions that can impose a drastic impact on human life and building infrastructures. Information and Communication Technology (ICT) plays a vital role in coping with such situations by enabling and integrating multiple technological resources to develop Disaster Management Systems (DMSs). In this context, a majority of the existing DMSs use networking architectures based upon the Internet Protocol (IP) focusing on location-dependent communications. However, IP-based communications face the limitations of inefficient bandwidth utilization, high processing, data security, and excessive memory intake. To address these issues, Named Data Networking (NDN) has emerged as a promising communication paradigm, which is based on the Information-Centric Networking (ICN) architecture. An NDN is among the self-organizing communication networks that reduces the complexity of networking systems in addition to provide content security. Given this, many NDN-based DMSs have been proposed. The problem with the existing NDN-based DMS is that they use a PULL-based mechanism that ultimately results in higher delay and more energy consumption. In order to cater for time-critical scenarios, emergence-driven network engineering communication and computation models are required. In this paper, a novel DMS is proposed, i.e., Named Data Networking Disaster Management (NDN-DM), where a producer forwards a fire alert message to neighbouring consumers. This makes the nodes converge according to the disaster situation in a more efficient and secure way. Furthermore, we consider a fire scenario in a university campus and mobile nodes in the campus collaborate with each other to manage the fire situation. The proposed framework has been mathematically modeled and formally proved using timed automata-based transition systems and a real-time model checker, respectively. Additionally, the evaluation of the proposed NDM-DM has been performed using NS2. The results prove that the proposed scheme has reduced the end-to-end delay up from to and minimized up to energy consumption, as energy improved from to compared with a state-of-the-art NDN-based DMS.

1. Introduction

Communications in the current Internet Protocol (IP) architecture focus on end-to-end connectivity. Internet of Things (IoT) devices use IP addresses to interact with each other, i.e., the client sends requests toward a specific server and the request is satisfied by the server. We emphasize IoT devices that have limited resources in terms of power and energy [1]. With the progress in the domains of ICT emerging technologies such as wireless sensor networks and fifth generation wireless communication capabilities, it has become more difficult to connect and monitor millions of devices, where the most important feature is the content security [2,3,4,5]. An IoT network consists of many such wireless devices that interact with the physical environment for collecting surrounding information and providing several services with the help of Internet [6,7]. The motivation toward IoT is the utilization of smart and intelligent devices for enabling and automating various services [8,9]. By using IoT, smart applications can be built, such as smart homes, smart cities, smart buildings, and smart campuses (SCs) [10,11]. Given this, IoT-based applications can be used to develop a Disaster Management System (DMS) [12] to cater to disasters such as storms, floods, fires, and earthquakes. Consequently, many companies are building IoT-based DMSs, such as the ZIZMOS and RIO projects funded by SBIR and IBM, respectively [13].

A disaster, e.g., a fire, can turn into a more hazardous situation in crowded places such as airports, shopping malls, play areas, and educational venues, such as campuses. A number of students in an SC are gathered on a daily basis. Due to the substantial amount of students, it is a hectic task to secure each and every student during disaster situations. There are many incidents that have happened in the past; for instance, at the University of Lahore in Islamabad campus, Pakistan, a fire disaster accident held due to short circuits and another incident held at ST Andrew University, United Kingdom in the Department of Chemistry. In both cases, the departments were on fire within a few seconds, and a great loss of important records and building infrastructure resulted [13]. An affordable solution to escape these kinds of disasters is to adopt an IoT-based DMS in crowded places to save lives. This enables us to ensure a reliable and efficient communication mechanism between IoT devices to implement an effective IoT-based DMS for an SC.

Due to numerous reasons, the available IP architecture is inappropriate for an IoT-based DMS [14], which include the inconsistency in privacy measures, power, and memory intake on small IoT devices due to heavy Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol (TCP/IP), excessive utilization of bandwidth resources, an unavailability of proper addressing for IoT devices, content security, and lack of support for network fragments [15,16,17,18,19]. In the last two decades, a prominent advancement has been remarked in the field of networking to cope with the limitations of existing IP architecture and to meet the requirements of emerging technologies. In this context, a new architecture is proposed, named Information-Centric Networking (ICN). Progressively, eight ICN-based architectures have been proposed for both static and mobile networks, which include NDN, CCN, CONVERGENCE, NetInf, DONA, MobilityFirst, COMET, and PURSUIT [20,21].

In ICN-based architectures, the communication among devices is performed by name-based content rather than IP-based addresses [22,23]. Due to the emergence of ICN, IoT applications can use naming for smart devices. The ICN architecture plays an important role in both IoT sensors and actuators as named content rather than assigning IP addresses [24]. In fact, the IoT infrastructure is ambiguous if managed through a TCP/IP architecture rather than a content-centric mechanism [15,25]. Since, ICN provides security to content, it is the best choice for IoT environments.

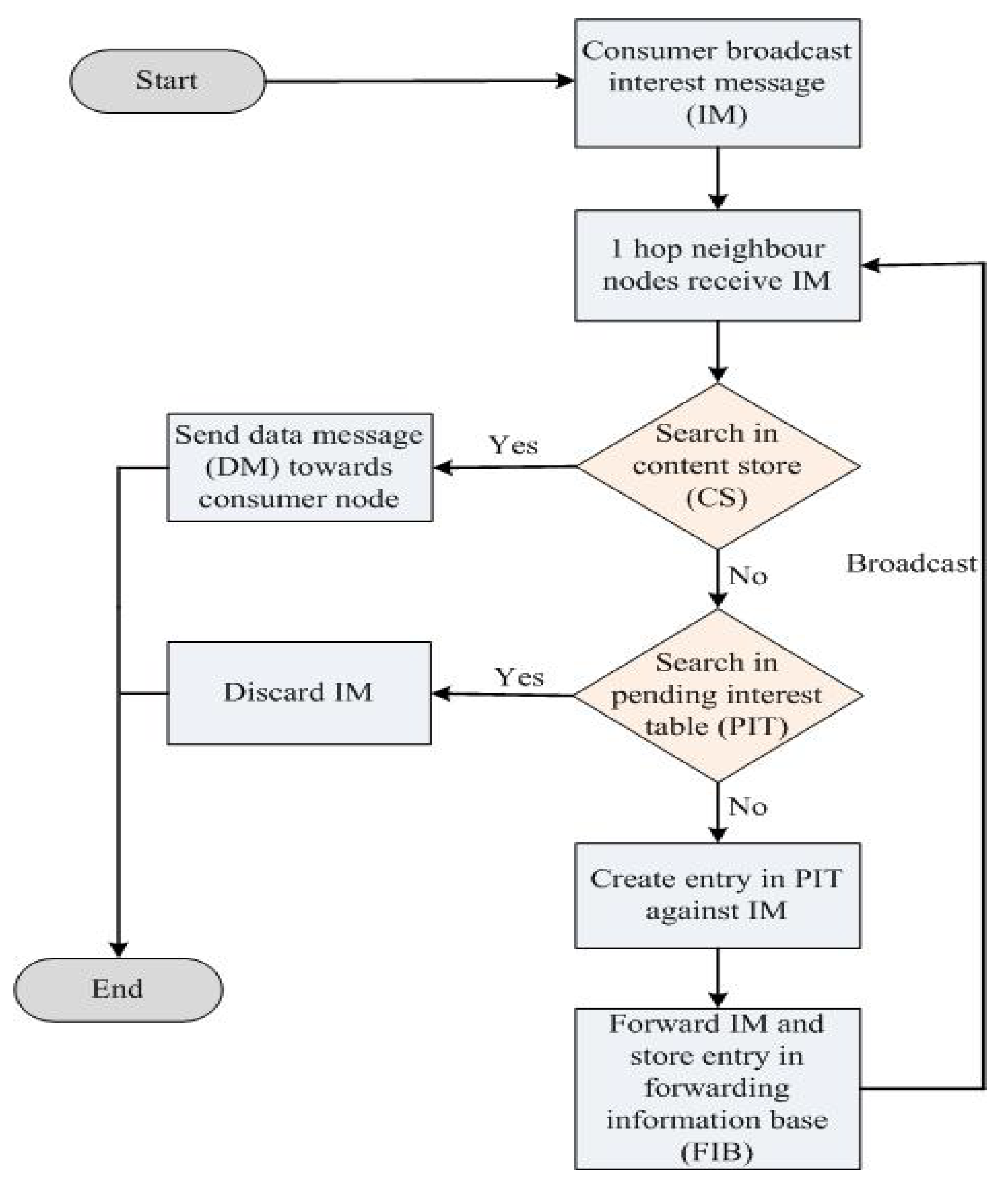

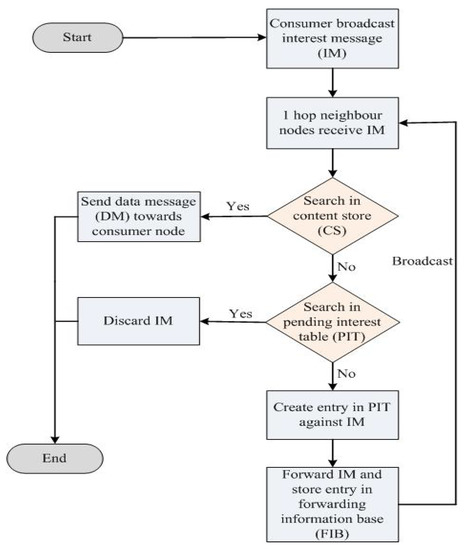

The ICN architecture (specifically Named Data Network (NDN) as shown in Figure 1) has two types of messages (i.e., interest and data messages), which are used by smart devices to make a request and to receive a response for that particular request in the IoT environment [20]. This architecture also maintains its security of system and devices from unauthorized access. For this purpose, both messages are signed by a consumer (who requests the content) and the information provider. The information is only provided when the consumer requests specific content, and this concept makes it more secure. Moreover, the ICN architecture provides a cost-effective solution due to name-based networking [20].

Figure 1.

Basic NDN architecture flow diagram.

Based on the previously defined benefits of ICN for IoT devices, NDN is considered the most appropriate approach to build DMS architectures based on IoT. The current NDN architecture helps consumers and producers to interact with each other by using name-based content [26]. This approach enables a consumer node to send an Interest Message (IM) toward the producer, and the producer node sends back the Data Message (DM) against the requested data [20]. In the emergency conditions of earthquakes, floods, and fires, the PULL scheme is not suitable and fruitful since a fast and efficient communication with minimum delay is required to handle them. In such situations, one cannot wait for the issuance of interest from the consumer and a response back from the producer because this leads to a delay, which is not tolerable in hazards. For such situations, the PUSH approach for communications between consumers and producer can be used in alarming and disaster situations. The PUSH approach reduces delay because the producer node sends an IM toward the consumer node without any involvement of the consumer node, and interest is sent based on the disaster monitoring sensors [27].

Based on the usage of the PUSH scheme with NDN, various IoT-based applications are developed for Disaster Management (DM). The NDN-based DMS approach is specifically related to disaster incidents. In a disaster situation, the concept of long-lived interest is not appropriate because this leads to extra overhead, and interest is sent back again when its timer expires. In [14], unsolicited data is handled with the help of pre-caching content by producing dummy interest; however, this scheme is only suitable for multimedia data and not focused on the disaster situation. The major disadvantage of the long-lived interest PUSH approach is such that the data may be re-sent at different time intervals, and this happens because of the Request Time Out (RTO) factor, which also increases the overhead in interest packets [27]. In a DMS, the overhead leads to delay in sending data from one node to another, and overall the throughput in an SC also decreases, which is not acceptable in real scenarios. IoT devices such as sensors, smartwatches, and smart mobile phones have limited resources in terms of memory and power [28]. Hence, there is a need to improve the existing NDN architecture in a resource-constrained IoT environment.

Because of limited resources in IoT devices, we require an effective and efficient NDN-based DMS that consumes fewer resources. In this approach, we do not need to re-transmit data as done in other methodologies due to the time out factor [27]. For disaster situations, we only send a fixed number, which is called a sequence number, for specific DMSs.

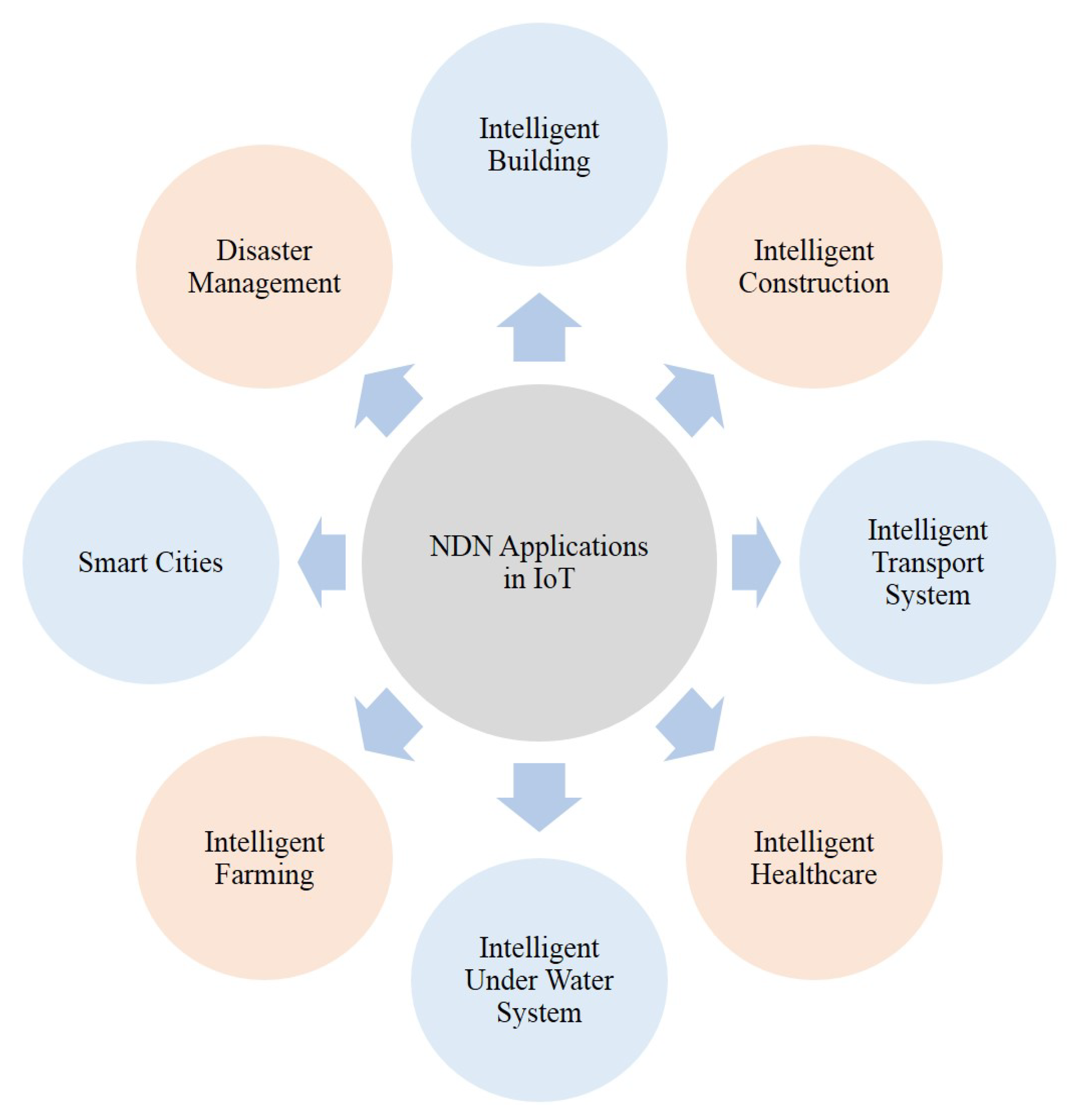

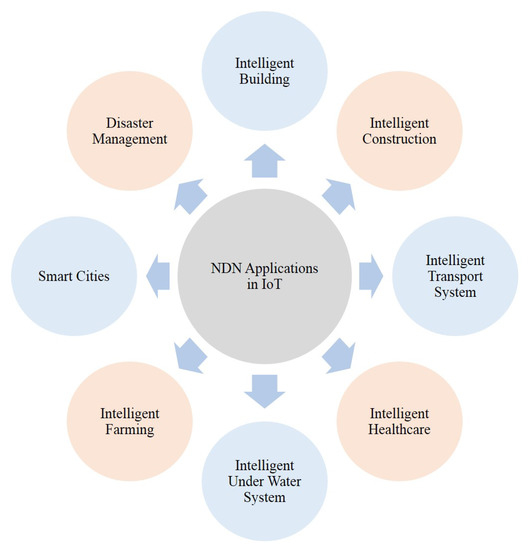

An NDN-DISCA architecture has been proposed in [13], which contains different interconnected devices. These devices are divided into five different partitions, such as Smart Faculty Room (SFR), Smart Labs (SL-1, SL-2), Smart Lawn (SLN), and Smart Class Room (SCR). In the NDN-DISCA architecture, fire sensors start sending information toward interconnected devices when the threshold value reaches a specific value and after receiving the specific value, these devices move toward a safe location. Different IoT applications based on NDN architecture are listed in Figure 2, which shows the importance of name-based content in today’s IoT environment.

Figure 2.

NDN applications in IoT.

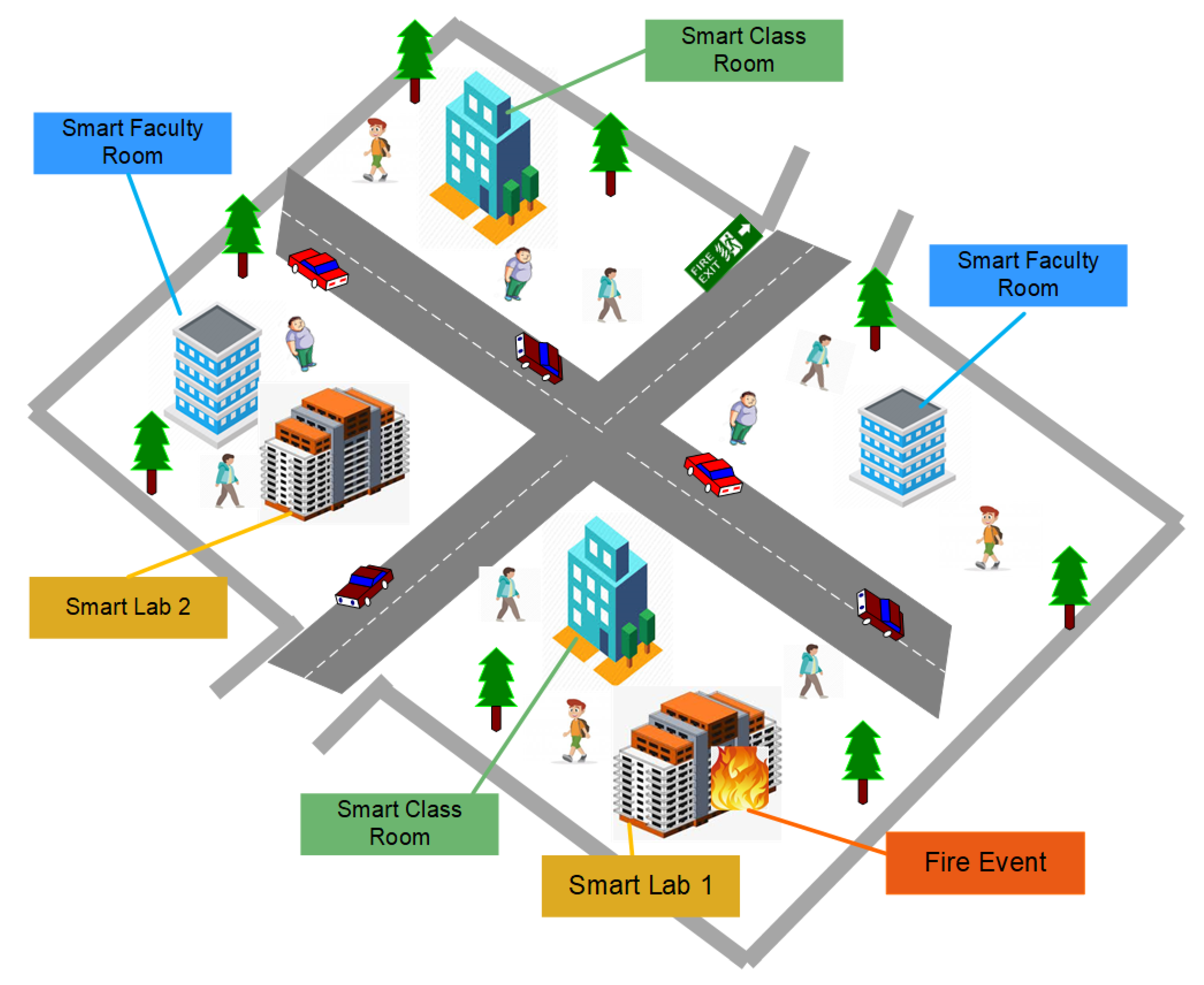

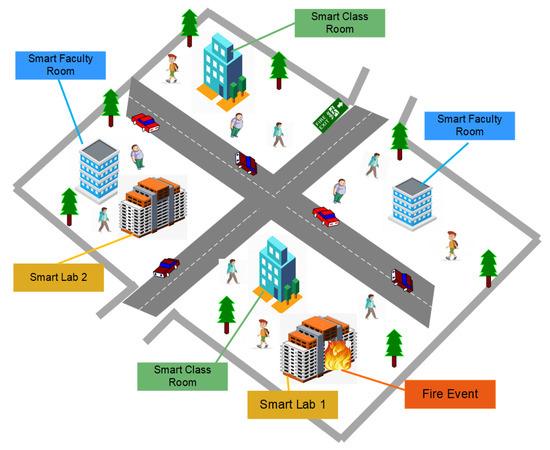

In this paper, we propose an NDN-based architecture specifically used in IoT-based DMS for SC scenario. The SC scenario is based on SL, SCR, and SFR, as shown in Figure 3. In this study, we use the PUSH scheme instead of the PULL scheme because this scheme avoids delays in packet transmission. Specific seq. no. ‘0’ is used to handle any abnormal situation. We named the proposed architecture as Named Data Networking Disaster Management (NDN-DM). In NDN-DM, we suspend the pending interest table (PIT) structure to observe its behavior specific to disaster situations. In the proposed scheme, critical data move from the producer nodes toward the interconnecting mobile nodes. The main contributions of this paper are listed below:

Figure 3.

A fire scenario in a smart campus (SC).

- a thorough investigation and comparison of existing ICN-based DMS;

- the proposition, design, and development of an efficient DMS (i.e., NDN-DM), specifically related to disaster scenarios in an SC;

- mathematical modeling and formal verification of the proposed approach using timed automata-based transition systems and a real-time model checker, respectively;

- simulation of an IoT-based SC disaster scenario in NS2;

- evaluation and comparative analysis of the proposed scheme with a state-of-the-art NDN-based disaster management scheme shows promising results in terms of delay and energy consumption.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: In Section 2, the related work about the DMS based on an ICN architecture is discussed. Section 3 presents the working, methodology, mathematical modeling, and formal analysis of the proposed scheme. In Section 4, the experimental setup used in this study is explained, whereas the implementation and final results are discussed in Section 5. Finally, a conclusion is summarized in Section 6.

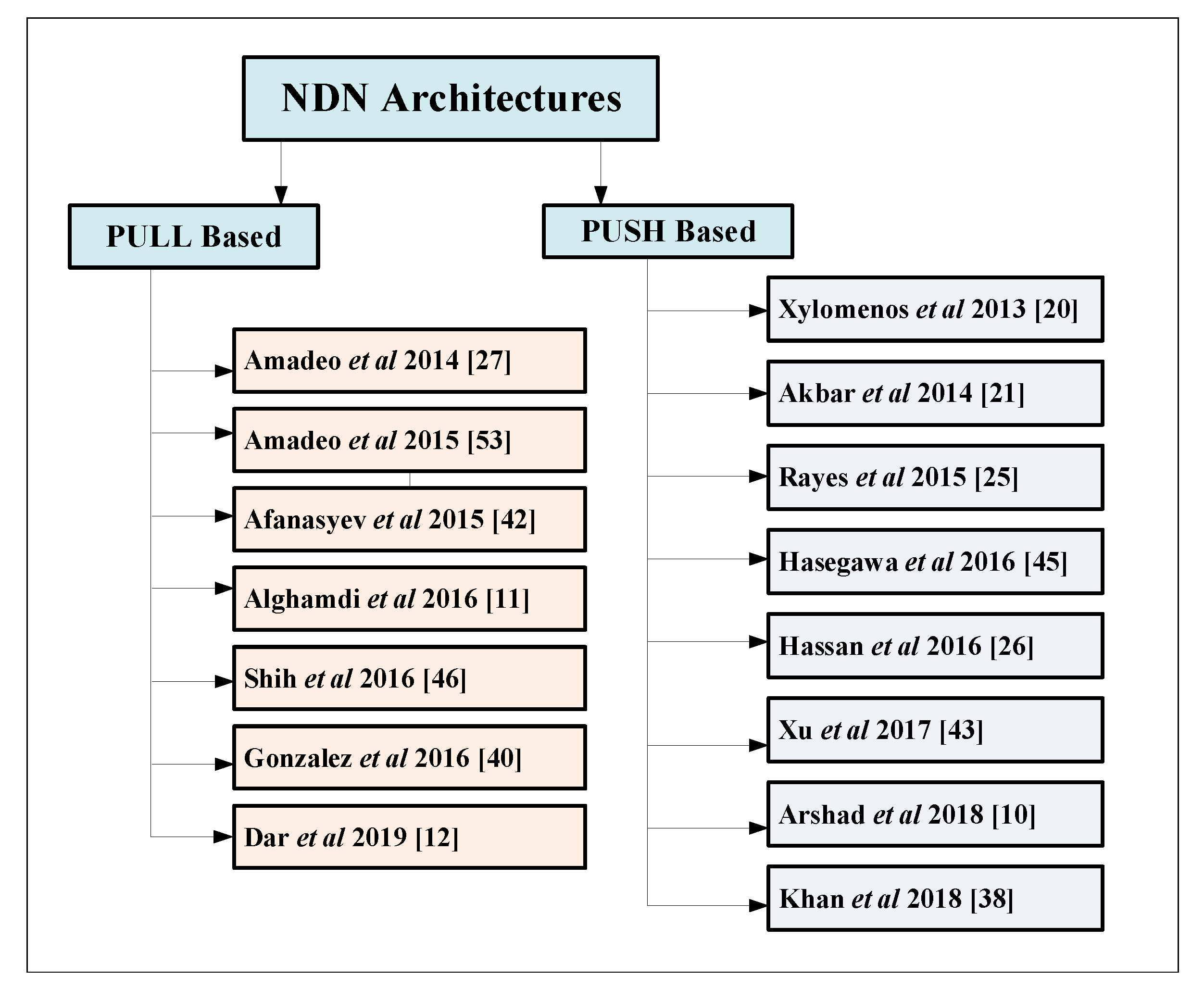

2. Related Work

In the last few decades, various disaster management strategies have been proposed by the research community using different techniques, such as PUSH and PULL schemes, cloud infrastructure, and the Satisfied Interest Table (SIT). The focus is to minimize the communication time between mobile nodes, reduce memory consumption, improve the packet delivery ratio, and consume less energy. In this section, we present studies related to disaster scenarios. By identifying drawbacks from the major existing work as mentioned in Table 1, we introduce new IoT-based DMS architecture with the help of NDN architecture for a Smart Campus as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Taxonomy of literature review.

The NDN architecture is one of the most important and efficient ICN architectures, and its major applications are related to IoT-based smart cities [29,30]. In this architecture, communications between consumer and producer nodes are based on content rather than the IP-based model [20]. Two types of messages are used in NDN for communications, which are Interest Message (IM) and Data Message (DM) [31], and three different types of structures are used, i.e., Content Store (CS), Forwarding Information Base (FIB), and Pending Interest Table (PIT). These structures are used for data caching and interest message forwarding toward other nodes. When a consumer wants specific data, the IM is broadcasted in the network for the retrieval of that data and the producer receives this message and sends the required data back to the consumer using a reverse path. The required content name is added with the IM, and in response the DM contains both the content name and the content data that is requested, and the DM is sent back to the consumer. In this communication, intermediate nodes receive this IM and broadcast it until it reaches the data producer.

The PIT lists all pending IMs, which are waiting for the response (DM) from the producer. When more than one IMs are received for the same content from the consumer, only the first one is broadcasted toward the data source. In the PIT, IMs are stored and are based on the content name and interest interfaces. When multiple requests for the same content are received, interest interfaces maintain the information about content receivers. When nodes receive the required data, first it is matched with the PIT entry, and the data is forwarded toward all corresponding interfaces stored in the PIT. After this, the entry in the PIT is removed and the corresponding data is stored in the CS for future uses.

The available NDN architecture only supports a PULL-based approach for communications between the consumer and producer by using IM and DM [29,31]. The PULL scheme takes massive delay; hence, it is not suitable in critical scenarios such as fires and earthquakes. In such scenarios, the PUSH-based approach is more feasible than the PULL approach; however, it is less protected than the PULL scheme. In the PUSH approach, there is no need for consumer-based IM and the producer itself broadcasts the message considering the severity of the situation [32]. Hence, the PUSH scheme is suitable in those situations where it is necessary to send the time-critical information with minimum delay and higher throughput.

2.1. Naming and Forwarding Approaches Used with the Named Data Network

Smart cities [33,34] consist of heterogeneous devices connected to each other to handle any situation. These devices are used to support different situations, e.g., disaster management, parking management, accident management, and security services that improve citizens’ living standard. Different applications based on NDN are developed [35] such as smart parking, smart homes, healthcare systems, surveillance systems, and weather related systems.

Piro et al. [36] proposed a framework for smart cities based on NDN to take advantage of name-based communications. A secure content transmission mechanism that has two major parts is proposed. In the first part, it is the responsibility of the consumer to identify the content provider from the network and establish a secure connection by sending the consumer and provider names in the interest message. Different scenarios have been discussed and have used hierarchical naming. In smart cities, hierarchical naming schemes are used because of its effectiveness in various services. The only drawback of including both consumer and producer in the content name is that it takes one back to the IP-based solutions.

Ahmed et al. [37] discussed the importance of an NDN network in maintaining smart cities. In his research, different scenarios related to smart cities have been presented, such as vehicular networks, healthcare systems, and wireless sensor networks, where NDN can play an important role. The authors also provided some future directions related to the NDN concept, i.e., forwarding strategies, content naming, and data recovery.

The communication between different heterogeneous devices in fragmented networks is the most common research problem, especially in a disaster situation. Ahmad et al. [38] proposed an IoT-based hybrid NDN model for disaster management scenarios. In this method, a special PUSH-based interest message and a Satisfied Interest Table (SIT) are used for efficient communications between wireless devices. A disaster detection mechanism is proposed that improves the processing time. This technique is simulated, and the evaluation results show improvement in latency and throughput.

Mochida et al. [39] proposed a method to monitor the weather conditions in smart cities using NDN. In this mechanism, the cameras and weather sensors monitor weather conditions and generate content in the smart city environment. Although this scheme is more effective in producing weather-related content, it generates lengthy names as content. These lengthy names may lead to overhead in IoT devices because of limited resources.

In [40], the authors discuss the disaster management scenario using the NDN architecture. The authors analyze three factors using least recently used (LRU) caching policy, i.e., end-to-end delay, traffic load, and hit rate. Different caching techniques are applied to show the performance in diverse networks. The produced results show that the NDN architecture performs better than the IP architecture in disaster management situations [40].

The NDN plays an important role in the IoT environment due to named content. The authors in [41] introduced a baseline NDN framework that helps in efficient data retrieval based on the same interest packet from several wireless producers located in the smart city. The Vanilla NDN scheme is used for forwarding so that the data available can be retrieved on multiple IoT devices, i.e., wireless producers. This scheme is evaluated by performing simulations in the ns3, and the results prove that this method reduces the overhead in the network and data collection time.

In another study [14], the authors proposed a Hierarchical Naming scheme based on the NDN architecture in an IoT-based SC context. Three different components are used for assigning names to content, i.e., application prefix, attribute-based, and hierarchical. The use of symbol “:” indicates the starting and ending parts of a specific content name, while the symbol “./” shows multiple attributes of the same content. Their proposed hierarchical scheme has been evaluated using ns3 and an ndnSIM-based module [42], where the results show that their scheme is scalable and secure.

Xu et al. [43] introduced a new model for forwarding interest packets. Sending data through multiple relay nodes is one of the most important aspects to be considered while designing routing schemes. Similarly, the selection of a suitable relay node (that can send data to a producer, and from a‘producer to a consumer) is equally significant. In this method [43], three different tables are used, i.e., a waiting table, a record table, and a forward table. Where interests on the waiting state are stored in the waiting table, the record table stores the requested interest, and the forwarding table stores interests that are not satisfied. The node with more memory space has a higher priority to be selected as an agent node. The nodes that have high communication frequency are selected as relay nodes.

The authors in [44] introduced a novel protocol for MANETs, named Efficient Multicasting and Collision Avoidance (EMCA). This protocol solves the flooding problem for interest and data packets by applying different measures of the PIT and CS. A new table, named a Routing Table (RT), is introduced at each node, which helps to identify different paths during data transmission if the path of some nodes breaks due to underlying networking issues. Simulations are performed and the technique is compared with Airdrop to show the performance of this technique in terms of throughput and energy consumption.

In [45], the authors have proposed the emergency delivery of messages in the NDN-based PULL mechanism, which is based on the COPSS algorithm [46], which utilizes an encryption technique to secure data. This technique is not appropriate for an IoT environment because it does not support traffic management in real IoT scenarios. In the IoT environment, it is necessary that each device must communicate and collaborate with other devices for achieving a specific task especially in a disaster situation. In disaster scenarios, the transfer of a large amount of data between heterogeneous devices in a real environment with minimum delay is required.

In another study [29], the authors introduce a new approach and develop a prototype for four consumer nodes in the network. In their scheme, consumers forward interest packets toward the intermediate router that maintains interest queues. The interests are handled by each router in the same form as they are generated, and there is a priority checker on each queue that handles interests according to the assigned priority. When a consumer transfers an interest along with the content of highest priority, this interest is also maintained in the PIT and FIB according to the assign priority. The interest with high priority is satisfied first.

The authors in [47] proposed an NDN-based architecture for IoT-based smart home scenarios where smart devices communicate with each other based on content names. In this method, a cloud infrastructure has also been utilized to collect the information from a home server and to store this data in the cloud database for future uses. This architecture provides the facility to users to extract information from the private cloud even if they are not in the range of smart homes.

The authors in [27] presented PUSH-based data communication in a basic NDN architecture. This scheme is evaluated in a personal network environment using simulations, and they identified less traffic load using their proposed scheme.

Due to limitations in the current IP-based layered architecture [48], NDN gains greater importance and researchers start studying this architecture for Mobile Adhoc Networks (MANETs). Sending the same content repeatedly using the same network path causes energy drainage, and a large amount of devices will not work properly in MANETs due to energy wastage [49,50,51]. The authors in [52] introduced a new routing protocol using the NDN architecture for MANETs. In this technique, every node maintains information about the consumed energy. They consider the residual energy as a key parameter for the selection of forwarding nodes. This protocol shows promising results with respect to energy efficiency.

2.2. PULL and PUSH Schemes

Three different PUSH-based techniques are proposed in [27], i.e., long-lived interest, notification through interest, and unsolicited interest data. The long-lived interest is not useful in disaster management scenarios because time is a critical issue and the existence of interest results in extra overhead. In this study, managing unsolicited data is done for handling multimedia data but without considering the disaster management scenario. Thus, this kind of interest cannot be feasible for disaster scenarios.

The availability of various topologies in MANETs leads to communication complexities between mobile nodes. The authors in [31] proposed a novel PUSH-based approach related to NDN scenarios. The proposed technique shows better results with regard to less memory consumption as compared to the PULL technique. However, this scheme consumes more resources, such as memory and energy, when used in the IoT environment. Hence, the application of this technique is not suitable in disaster scenarios where multiple IoT devices are deployed.

Table 1.

Previous research contributions.

Table 1.

Previous research contributions.

| Ref. | Problem Addressed Or Contribution | Parameters Evaluated | Tools Used | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [40] | Manage disaster scenarios | End-to-end delay. | NS3. | Effect on energy |

| using the ICN concept. | Traffic load. | DVB-S2. | consumption | |

| In disaster situations, various | Hit rate. | DVB-RCS2. | not defined. | |

| caching techniques applied. | ||||

| [41] | Baseline NDN framework | Save bandwidth. | ndnSIM | Consumer and |

| that helps in efficient | Efficient data | module. | producer are | |

| data retrieval based on the | retrieval time. | NS3. | both static nodes. | |

| same interest packet. | ||||

| [32] | Location-based NDN | High memory | MATLAB. | Applicable for |

| framework is proposed. | consumption. | small-sized data. | ||

| [53] | Hierarchical Naming | Scalability. | NS3. | Encryption applied, |

| scheme based on NDN | Security. | ndnSIM | which can be | |

| architecture is proposed. | module. | time-consuming. | ||

| [14] | Multiple PUSH-based | Reliable communication | MATLAB. | High resource |

| techniques are proposed. | between nodes. | consumption. | ||

| [43] | Model for forwarding | Delay to transfer | NS2. | Inefficient for |

| interest packets. | information. | disaster situations. | ||

| [31] | PUSH technique is | Decreased data transfer | ndnSIM. | Memory and energy |

| proposed for | time. | consumption in | ||

| VNDN. | IoT-based NDN. | |||

| [54] | DTN proposed with the | Memory consumption. | MATLAB. | Not suitable in IoT |

| help of ICN. | Accuracy measure in | because of resource | ||

| decentralized scenarios. | consumption. | |||

| [29] | Modified the existing | Increased throughput. | NS3. | Only suitable for |

| NDN by introducing SIT | post-disaster | |||

| (Satisfied Interest Table). | scenarios. | |||

| [45] | Emergency delivery of | Security improved by | MATLAB. | Unsupportive |

| message in the NDN-based | by using encryption. | in an IoT real | ||

| PULL technique. | Decreased delay in | environment. | ||

| message delivery. | ||||

| [46] | Routing protocol proposed | Energy efficiency. | NS3. | Incompatible in |

| for MANET using CCN. | disaster situations. | |||

| [13] | Architecture based on NDN | Interest satisfaction rate. | NS2. | Cloud infrastructure |

| for an IoT smart home | Data retrieval delay. | proposed but not | ||

| environment is proposed. | suitable for real time | |||

| disaster management. | ||||

| [47] | PUSH-based data delivery | Less power consumption. | MATLAB. | Not discussed in |

| using basic NDN | Effective in terms of | disaster management | ||

| architecture. | resource usage. | scenarios. | ||

| [27] | New protocol is proposed | Throughput increased. | NS2. | Packet collision |

| based on a VCCN (vehicular | Less interest packet delay. | SUMO. | not avoided. | |

| content centric network). | Less network load. | |||

| [55] | Efficient multicasting and | Gain high throughput. | NS2. | Extra overhead on |

| collision avoidance protocol | Less battery | the network due | ||

| is proposed for MANETs. | consumption. | to the routing table. | ||

| [44] | Hybrid NDN method is | Measured network | NS2. | Inefficient for |

| proposed for fragmented | efficiency through | complex networks. | ||

| networks. | latency and throughput. | Memory parameter | ||

| needs improvement. | ||||

| [38] | Framework is proposed | In disasters, efficient | Discrete | Evaluated only in |

| based on NDN/CCN | recovery of cached data. | event simulator. | the case of a fragmented | |

| architecture in case of link failure. | network. | |||

| [56] | Priority-based interest | Less queuing delay. | NS2. | Complex when |

| packet forwarding | Efficiently achieving | the number of nodes | ||

| mechanism in CCN. | content based on priority. | increased. |

Jan et al. [54] propose the concept of a Delay Tolerant Network (DTN) with the help of ICN and are concerned more about handling disaster scenarios using the PULL scheme. In disaster situations, the movement of nodes is impulsive [13]. Due to the complexity and the random movement, this technique can be unreliable in an IoT-based system. Various devices having limited resources with different capabilities are deployed in IoT environments, so complex algorithms are not appropriate in such dynamic environments. Consequently, this approach is not suitable for IoT-based DMSs.

In [29], a PULL technique based on the NDN router architecture and design is proposed. The authors convert the existing NDN architecture by including a SIT. This approach is only useful when the network is fragmented and consumers can cache data at the SIT according to their desires. The forwarding table structure has also been modified for a fragmented network. By using the SIT table, the throughput has also been increased in a post-disaster scenario. This study considers static nodes and cannot be very useful in a highly dynamic IoT environment.

3. Methodology

In this section, we provide details of the proposed NDN architecture. We discuss the processing of producer and consumer nodes in a disaster situation. In the NDN-DM system, to handle the fire situation, a specific threshold value is used in the case of disaster modes. We improved the NDN-DISCA architecture because it produces extra overhead on the network due to the existence of a PIT structure. In the NDN-DM system, due to the suspension of the PIT structure, the effectiveness of this scheme, specifically in disaster situations, is revealed. The NDN-DM method is evaluated based on time and energy consumption metrics, and is compared with the NDN-DISCA system [13]. The details of a fire scenario in an SC are also provided.

3.1. Design Details of NDN-DM

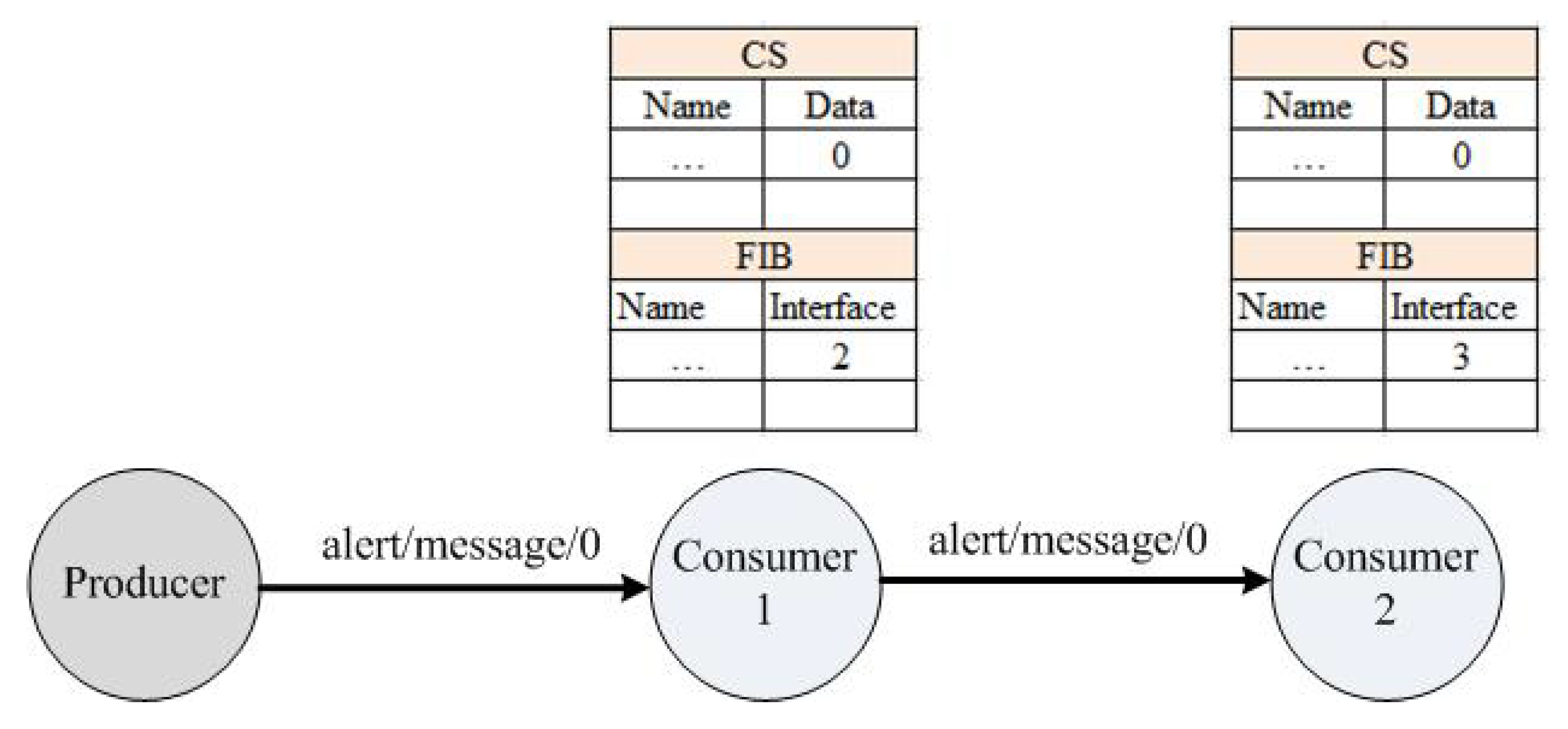

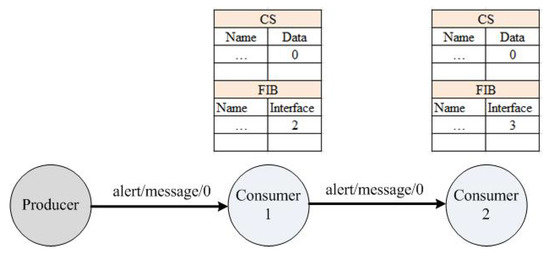

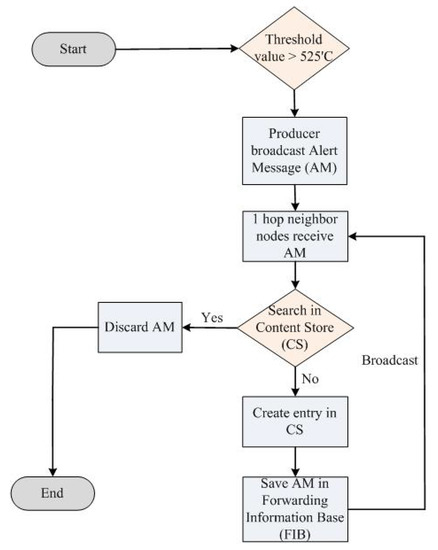

In the proposed architecture, we are limiting the dissemination of the PIT in a disaster scenario by temporarily suspending the function of the PIT operation, as shown in Figure 5. The only purpose of the PIT is to maintain the identity of incoming interfaces requested for particular data from neighbouring nodes, and when the data are achieved, then they are sent toward each node according to the incoming interfaces. In the NDN-DM system during a disaster, there is no need to maintain entries in the PIT because it does not require any data from intermediate nodes The focus is more on sending the alert message toward neighbouring nodes with minimum delay. The motivation behind suspending the PIT structure is to improve the delay and energy specifically in disaster incidents. In a disaster scenario (fire), the alert message uses fixed seq. no. “0”, which shows the occurrence of disaster in the SC premises.

Figure 5.

Alert indication mechanism.

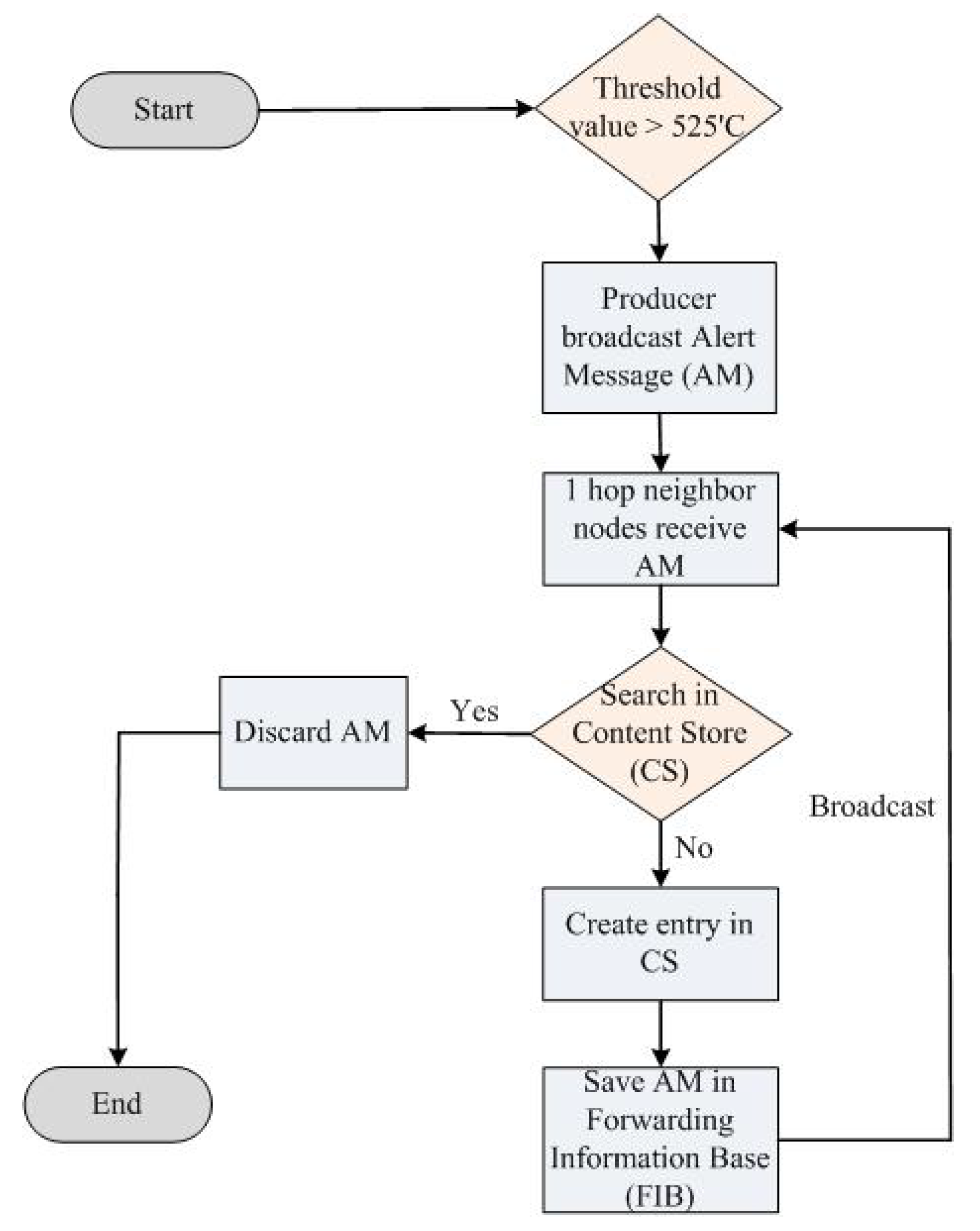

NDN-DM related to fire disaster scenarios in IoT, as depicted in Figure 6, is based on the basic NDN architecture. In disaster situations, a specific alert message is broadcasted when the fire sensors’ value exceeds the predefined limit. In the NDN-DM system, we used the PUSH-based technique for fire management in the IoT environment [13].

Figure 6.

NDN-DM flow diagram.

3.2. Smart Campus Use Case Scenario Used in NDN-DM

In the NDN-DM system, we discuss the processing of a producer and consumer in a disaster situation. To handle the fire situation, a specific threshold value is used in the disaster mode. This method is evaluated based on the time and energy consumption metrics, and is compared with the existing scheme, namely the NDN-DISCA system [13].

In this study, we consider an SC scenario [13] divided into different groups: SL-1, SCL, SFR, SL-2, FE-1, and FE-2, which has been shown previously in Figure 3. In an SC, sensors sense their surrounding environment. When the sensor’s value is less than the threshold value, this indicates that the SC is disaster-free. Symmetrically, when the sensor’s value is greater than the specified limit, this indicates the occurrence of a fire disaster somewhere in the SC. In a disaster mode, each mobile node sends critical data from hop to hop until all nodes are notified. Using this method, we are able to inform all students and teachers about the fire incident before it becomes uncontrollable and draws terrible results in terms of lost human life.

3.3. Disaster Event Handling in NDN-DM

In the proposed NDN-DM approach, due to the increase in fire, the sensor’s value is ≥ 525’C, which indicates the occurrence of disaster on the SC premises. The producer broadcasts an alert message (AM) toward one hop neighbor nodes. In the AM, seq. no. ‘0’ is used, and this is specifically utilized in disaster situations [13]. The consumer or neighbor nodes receive the AM and match the AM data with the CS entries. If the data already exists in the CS, then this AM is discarded to avoid flooding. Likewise, if the data do not exist, then the data stored in the CS and AM are sent to the FIB table to further broadcast it toward neighbor nodes. In the NDN-DM system, we improved the NDN-DISCA system because in disaster situations, there is no need for the PIT to maintain the AM entries in the PIT structure because we can achieve the same functionality without it, as shown in Figure 6. The PIT creates extra overhead in the network, which is not acceptable in critical situations, especially in disaster scenarios.

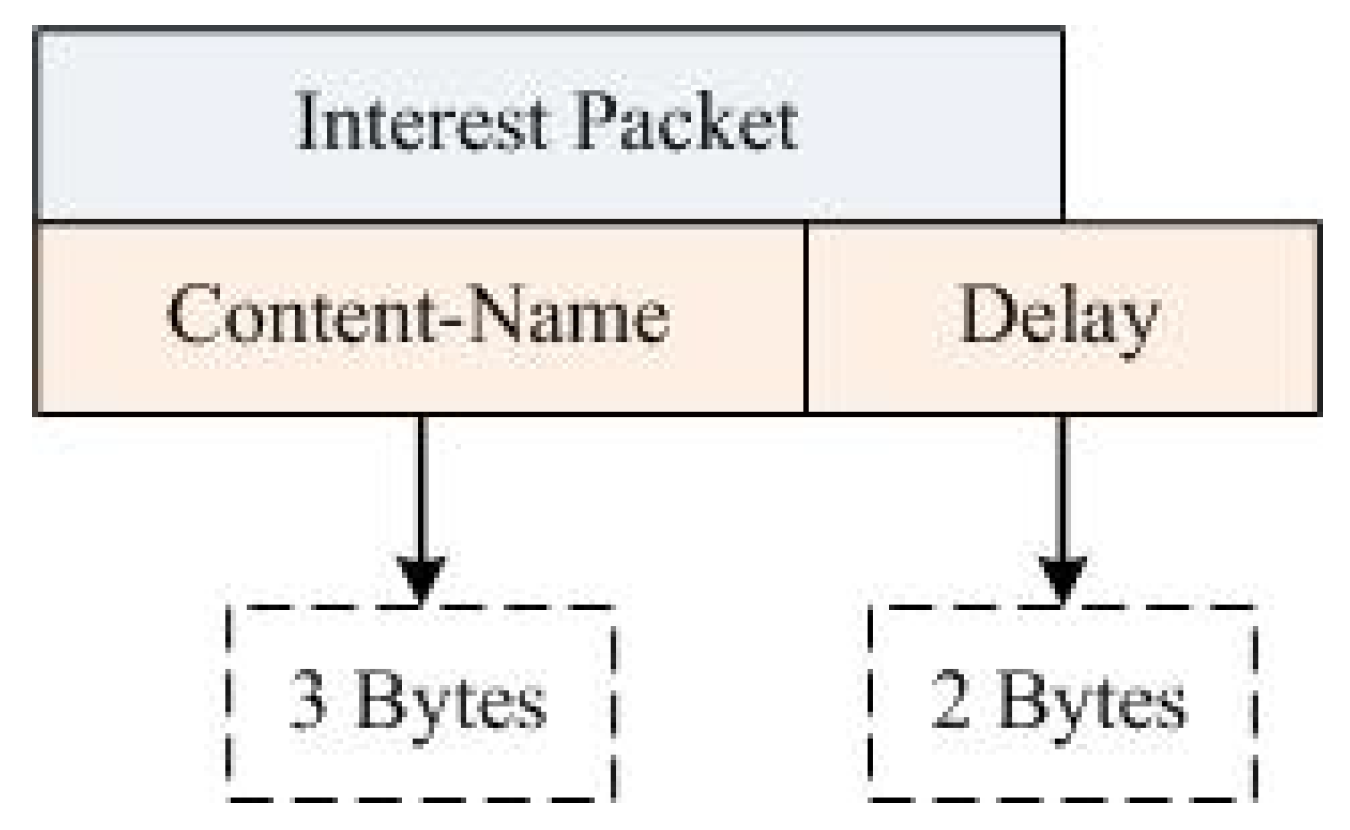

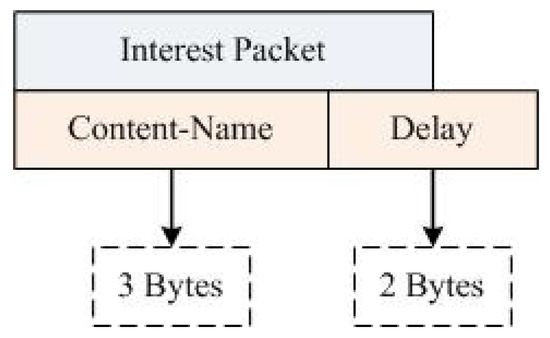

3.4. Customization of Packet and Table Headers

The NDN-DM system uses a packet header for communications, as shown in Figure 7. The packet header represents information that is sent in a disaster scenario. When the actual value exceeds the threshold limit, then the customized interest packet (alert message) is handed over to the network. The packet includes Content-Name (its size is 3 bytes), which contains the specific seq. no. ‘0’ used in disaster situations. The delay field (2 bytes in size) stores the time required for the packet to reach neighbor nodes. A total of 5 bytes are taken by the interest packet.

Figure 7.

NDN-DM packet header.

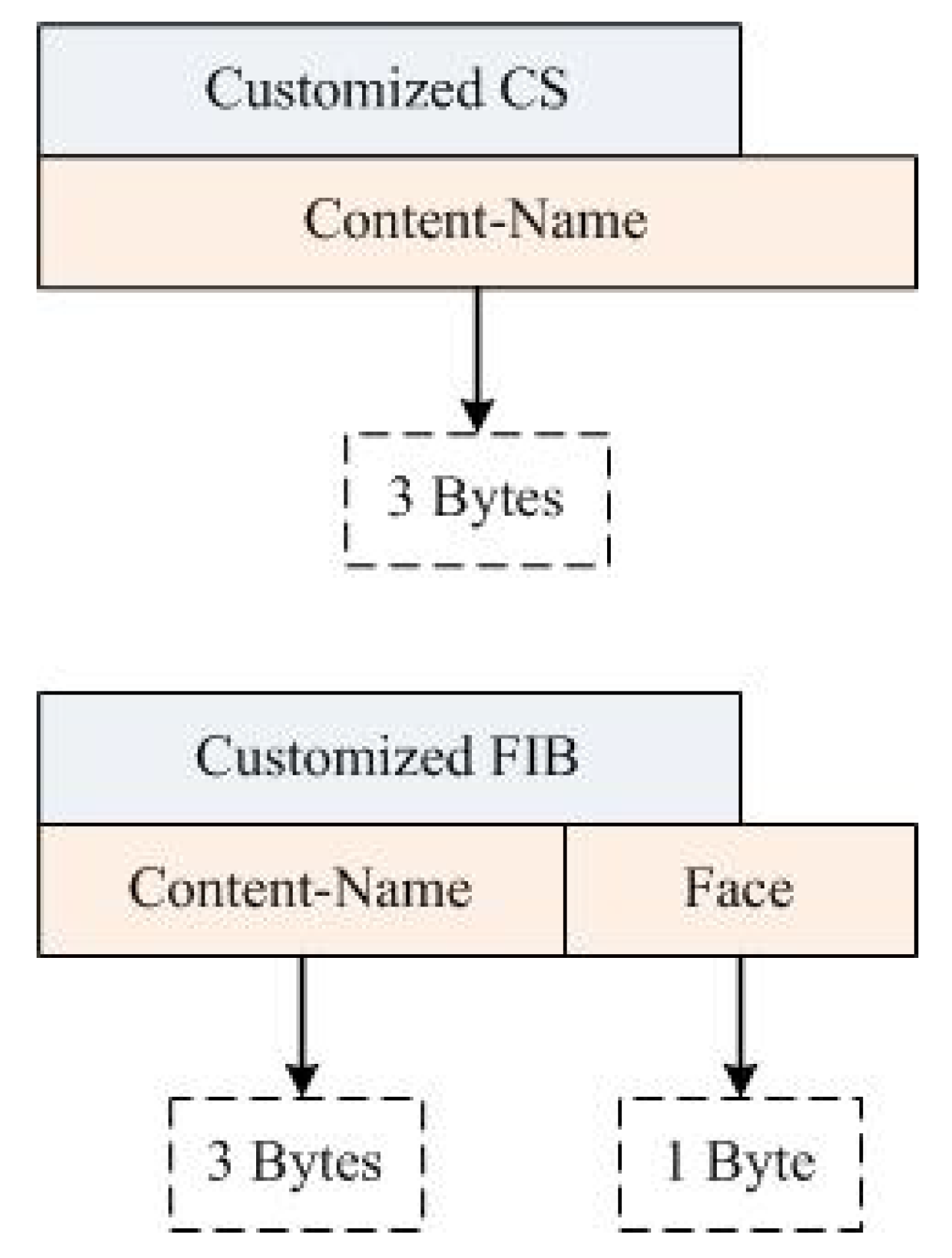

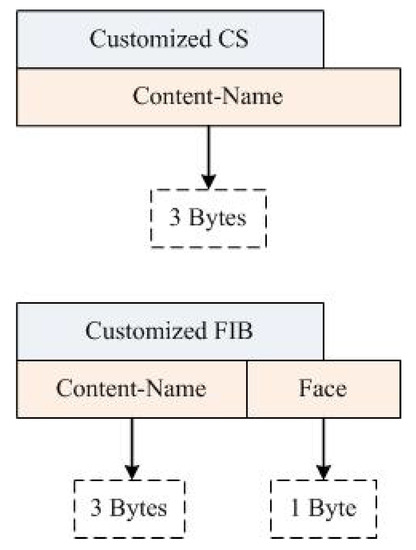

The proposed NDN-DM uses CS and FIB as table headers (see Figure 8). The table header represents information that is maintained on each node during disaster situations. The CS header includes Content-Name, which is the disaster message, the FIB header includes Content-Name, and the Face field (1 byte in size) stores the id of nodes.

Figure 8.

NDN-DM table headers.

3.5. Alert Packet Forwarding Algorithm

Fire sensors are used to detect the surrounding environment and fire sensor nodes, which are also called producer nodes. Every sensor maintains a threshold limit value and continuously monitors those limits. If a threshold value is greater than the prescribed value, this means a disaster scenario occurs somewhere in the SC. In the disaster case, the producer broadcasts an alert message toward neighboring nodes. In the alert message, the producer sends the Cid (data), which contains the specific seq. no. ‘0’, particularly used in disaster situations. Each relay node represents with nr, and each intermediate node has its CSr, which maintains information about the alert message. Each neighboring node receives the Cid and searches its CSr entries. If the Cid is not available in the CSr entries, then the Cid is stored in the CSr and sent to the FIBr, which actually further broadcasts the Cid toward other nodes. When nodes receive an alert message, then they start moving toward a safe place. If the Cid is already available in the CSr, then the interest message is discarded, which means that it is already received from other nodes. When relay nodes receive the same alert message multiple times, only the first received message is stored in the CS because the same alert message travels in the network. This way, we can also avoid flooding in the network.

3.6. Mathematical Modeling and Analysis

To examine the maximum delay that the proposed algorithm can experience and provide evidence about the efficiency under disaster mode, we have mathematically modeled the framework. In addition, we have formally proved that the maximum delay that the system can experience to inform all nodes is always smaller than the threshold T. In fact, T is relative to the size of the network considered and the dynamics of the system. The model has been built using timed automata-based transition systems, whereas the formal analysis is achieved using the real-time model checker.

We first define the behavior of the network as a transition system where states correspond to configurations and transitions correspond to the actions’ execution. We use a variable clock c to track time, variable mode to store the operation mode (disaster or normal) of the network, and is the set of nodes existing in the network. Let us use

as the set of all potential valuations of the variables used by the algorithm to track the network dynamics. is the domain of all variable valuations. We use A for the set of all potential actions to be performed in the NDN such as forward request and create entry in PIT.

We specify accordingly a state to be a valuation v of the system variables together with an enabled action a to update the state, which thus moves the system to another state. indicates the actual time at state s, states the operation mode at state s, and returns whether a node is informed at state s or not.

We define a run of the NDN-DM system to be a finite sequence of the states visited by the system behavior following the execution of the associated actions as follows:

The delay of each transition corresponds to the execution duration of action a at state . Such a delay is in fact relative to each action. We shortly write for a run from state s to .

Given that we are interested in the disaster mode, we only consider the sub-traces starting with a state such that . To provide evidence about the maximum delay of our algorithm to inform all nodes once a disaster is noticed, we accumulate the time duration from the very first state corresponding to a disaster occurrence, i.e., having a disaster mode variable updated to true, until we reach a state where all nodes are informed. Such a property can be formally expressed as follows:

refers to the cardinality of the trace leading from to , i.e., the number of steps. The model checker has been used to check that the total delay of any sub-trace leading from a disaster occurrence to a state where all nodes are informed satisfies the aforementioned property.

4. Experimental Setup

In this study, the NS-2 simulator was used to show the performance of the proposed methodology on the Linux Operating System (Ubuntu 18.04 64 bit). We used the specification of a machine having 1.90 GHz processor core i3 and 6 GB of RAM to evaluate the performance of the proposed NDN-DM approach. In the NDN-DM system, we used a total of 50 nodes, which were placed randomly in different blocks in an area of 50 by 100 m. The number of nodes can be increased according to the scenario. Some previous studies used 50 and some 100 nodes for their simulations. Some nodes were static, and some were mobile. Mobile nodes move according to the random direction 2D model [13]. Figure 3 presents the proposed SC use case scenario, which is based on SL-1, SL-2, SFR, SCR-1, and SCR-2. There is one producer node, and all others are consumer nodes. The proposed approach is specifically designed for a disaster scenario. The producer node forwards the alert message using a multi-hop wireless communication mechanism. The proposed simulation scenario of the SC is run 10 times to take average values. It depends on your choice, and how many times you want to run the simulation for calculating average values in NS2. The simulation parameters are listed down in Table 2.

Table 2.

Simulation parameters.

5. Results Analysis and Discussion

In the proposed scheme, the simulation scenario is limited to an SC because we have compared this scheme with NDN-DISCA [13], and NDN-DISCA has only been applied to an SC scenario. In future, we will extend this work to different scenarios, e.g., smart cities and smart homes, in order to evaluate the scheme in different scenarios. We used the PUSH scheme with the proposed architecture to show the effectiveness in a disaster scenario. In an SC, mobile nodes are moving randomly and participate in communications. In NDN-DISCA, a disaster situation can also be handled correctly without the PIT structure. In NDN-DISCA, the PIT structure produces extra overhead on the network. Therefore, in NDN-DM, the PIT structure was suspended. Two metrics were considered for the evaluation of the proposed scheme, i.e., delay and energy consumption. The total delay (TD) was calculated using Equation (1), and the value of the total delay was calculated using Equation (2) to find the average delay (AD) [57]. The average energy consumed (AEC) by the nodes was computed using Equation (3) [58].

where ‘n’ represents the total number of generated packets in the network.

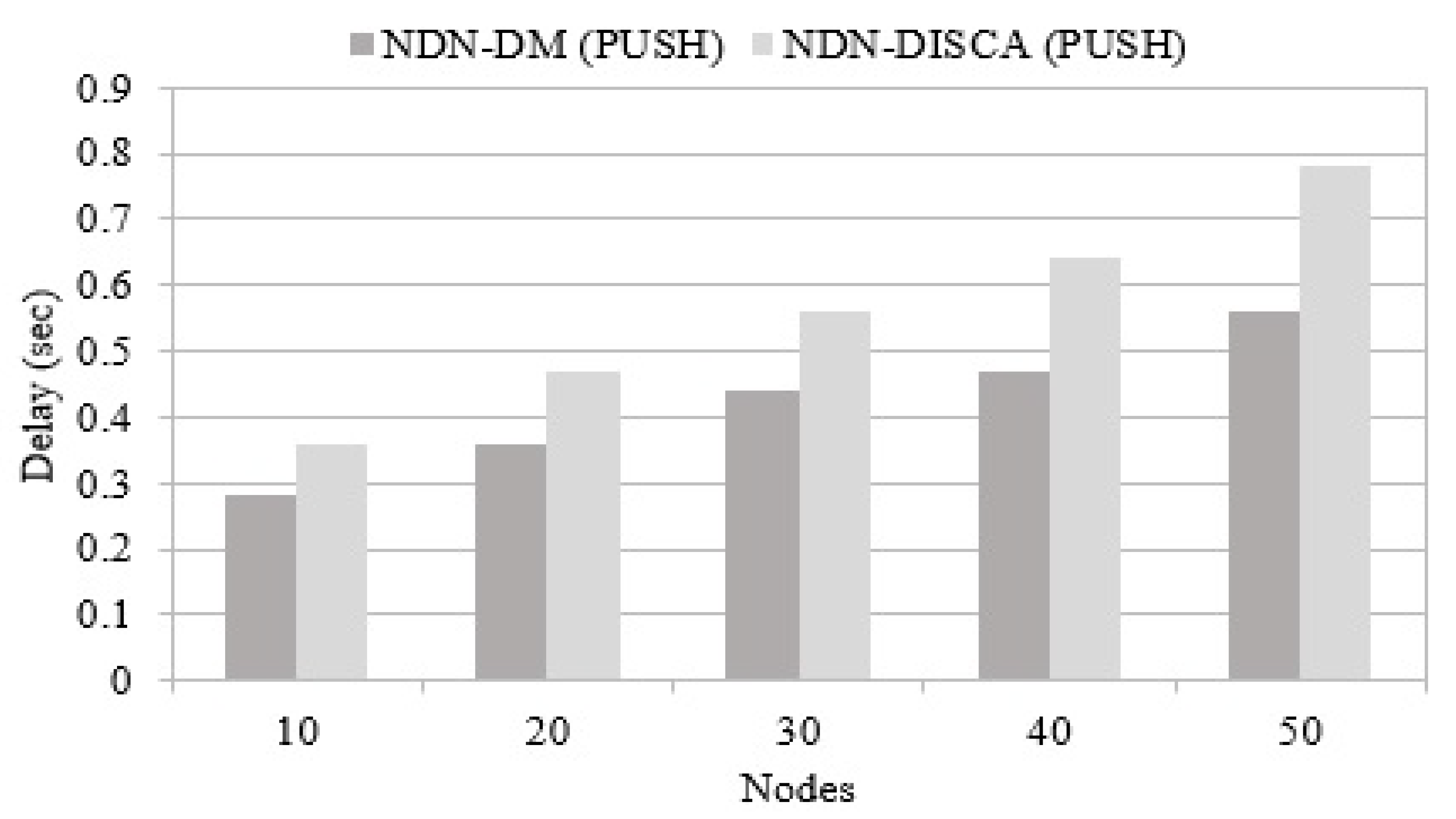

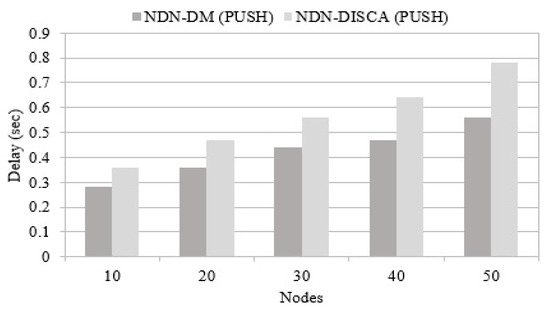

5.1. Delay

This performance parameter focuses on time taken by the alert message to reach toward all nodes in the network. In the first case, it shows the communication time of each node taken to broadcast the message, and neighboring nodes receive this message until it reaches each and every node available in the network. It can be seen in Figure 9 that the NDN-DM method exhibits a lower delay, as compared to NDN-DISCA. When the number of nodes increases in the network, the delay also increases, but the proposed NDN-DM shows better results in comparison to NDN-DISCA due to the complete suspension of the PIT structure, which causes extra overhead and augments the delay in disaster management situations. Suspending the PIT from the proposed scheme improves the time in NDN-DM.

Figure 9.

Delay in connected nodes.

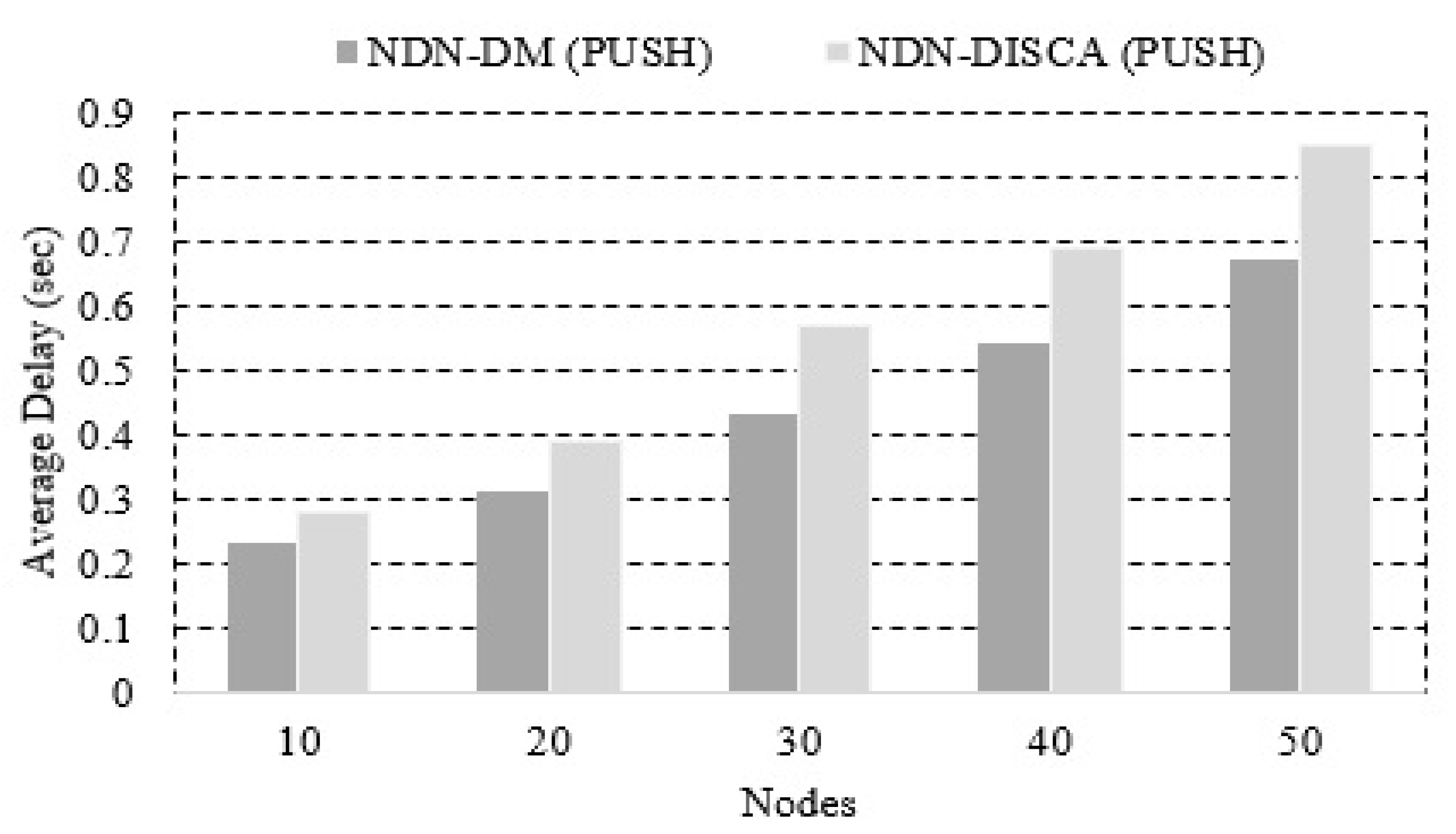

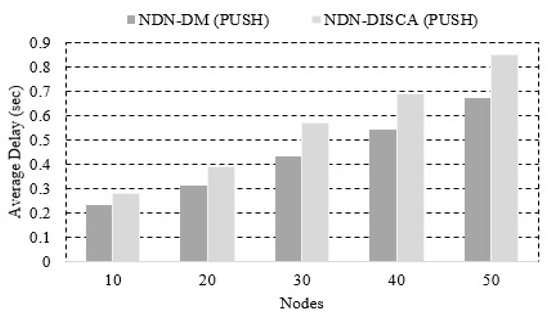

In the second case, we ran the simulations 10 times and calculated the average of these values, which can be seen in Figure 10. The results show that the average delay of NDN-DM increases when the number of nodes increases, but the NDN-DM system shows better results as compared to NDN-DISCA. In Table 3, the percentage of improved delay is presented.

Figure 10.

Average delay in connected nodes.

Table 3.

Improvement (%) in delay and energy in comparison to the NDN-DISCA scheme.

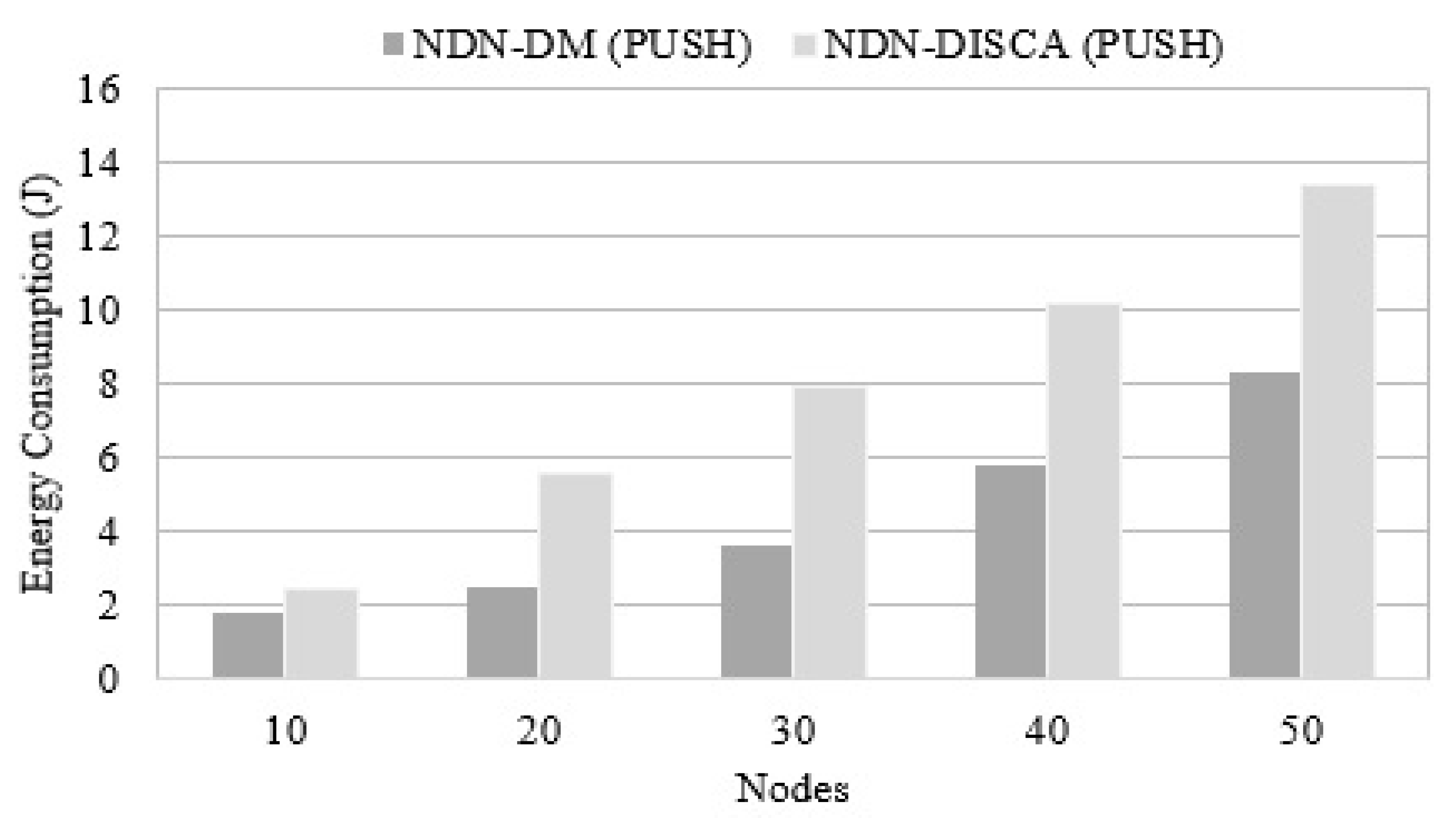

5.2. Energy Consumption

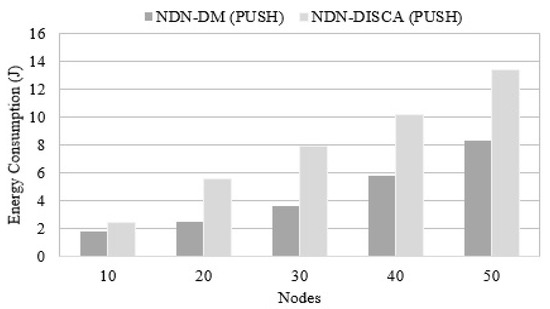

The second goal of the proposed NDN-DM architecture is to attain energy efficiency as compared to NDN-DISCA. For this purpose, the total energy consumed by nodes is regularly calculated while communicating in the SC. Due to the removal of the PIT factor from the network, nodes consume less energy during communications in disaster management scenarios. In the NDN-DM system, it is proved that without a PIT structure, disaster situations can also be handled and managed without effecting the generality. In Figure 11, it can be noticed that NDN-DM consumes less energy as compared to NDN-DISCA while evaluated using a different number of nodes. Due to the increment in the number of nodes, the NDN-DM takes less energy and produces better results than the NDN-DISCA.

Figure 11.

Energy Consumed by Connected Nodes.

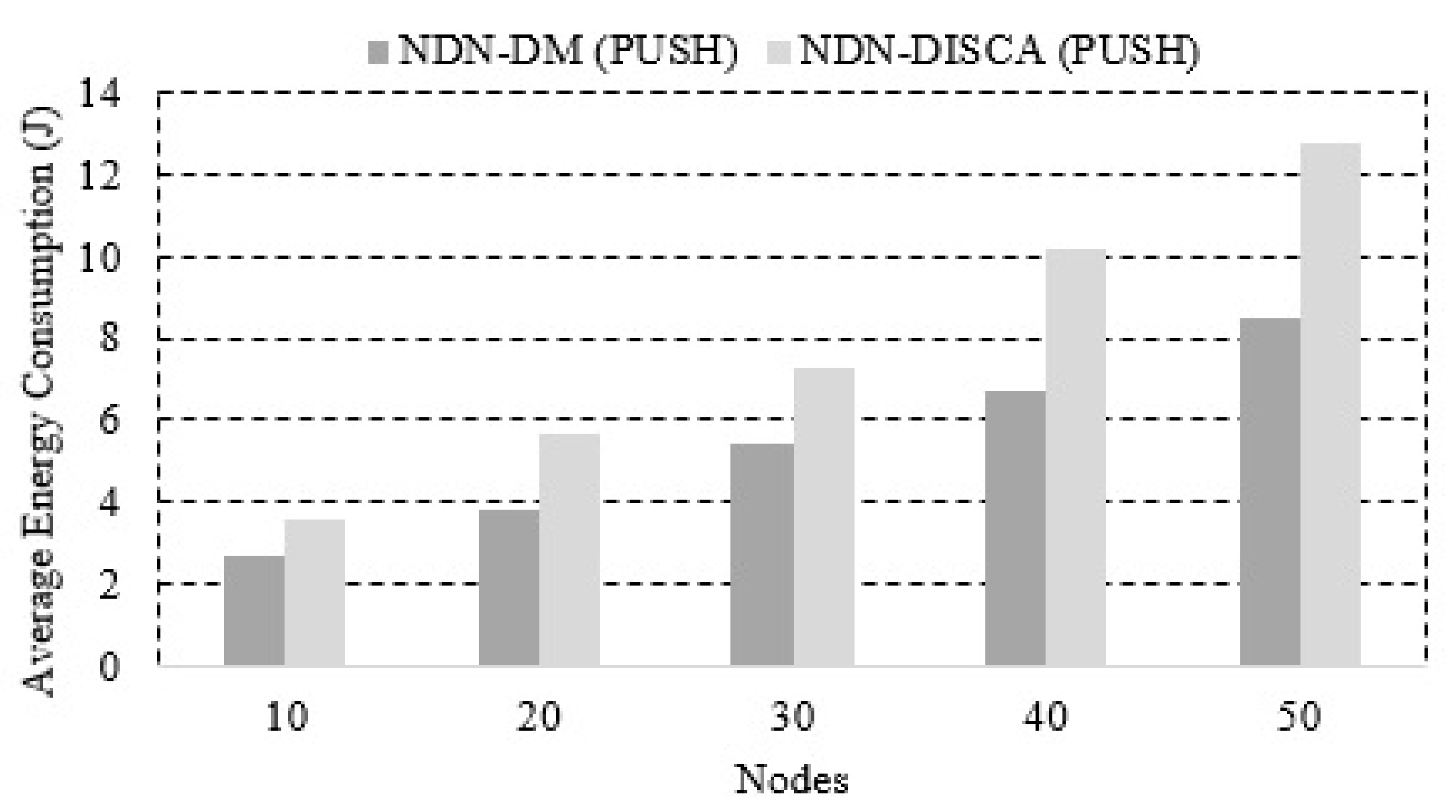

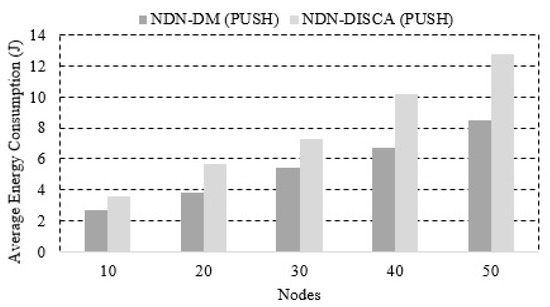

The higher energy efficiency prolongs the network lifetime, which is a highly critical factor in DMSs. In the second case, we also executed the simulations 10 times to take the average and obtained more confident results from the simulations. The results after calculating the average are shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Average energy consumed by connected nodes.

The results show that NDN-DM consumes less energy as compared to NDN-DISCA, and when the number of nodes increases, then more energy is consumed, but NDN-DM produces better results than NDN-DISCA. In Table 3, we show the percentages of improved energy using the NDN-DM architecture. It can be seen that the proposed scheme improves energy from to as compared to NDN-DISCA.

6. Conclusions

The delay and energy consumption are considered among the most important metrics in critical IoT applications such as IoT-based DMS. The IP-based communication architecture pertains to various limitations regarding the excessive use of computing and networking resources along with content security; hence, it is not an ideal choice for time- and energy-sensitive applications. On the contrary, NDN (an ICN-based architecture) provides an opportunity as a lighter and secure communication architecture to manage resource-constrained environments efficiently. In this paper, an IoT-based DMS, named NDN-DM, has been proposed that follows a PUSH scheme to manage communications and collaborate among IoT devices. The proposed scheme aims to reduce the overhead in communications without compromising on the core functionality. The motivation behind suspending the PIT structure in the NDN-DM system is to improve the delay and energy, specifically in disaster incidents. Consequently, the proposed approach performs better than NDN-DISCA and improves performance in terms of delay and energy consumption up to 10% and 20%, respectively. Although this study focuses on SC, it can also be extended to different disaster scenarios, such as smart hospitals, smart homes, smart malls, and smart cities. Hence, in the future, it is aimed to implement and evaluate the proposed scheme in varied disaster scenarios. This research has the following limitations: (i) This scheme can be more efficient in memory utilization, as we know that smart devices have limited memory; thus, there is a need to improve memory consumption. (ii) When the number of nodes is increased, the network complexity is also increased.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.A.S.; formal analysis: I.U.D. and H.A.K.; funding acquisition: A.A.; investigation: Z.A.; methodology: C.M.; resources: A.A.; validation: C.M.; writing—original draft: H.A.K.; writing—review & editing: I.U.D., A.A., and H.A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

The authors are grateful to the Deanship of Scientific Research, King Saud University, for funding through the Vice Deanship of Scientific Research Chairs.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Deanship of Scientific Research, King Saud University, for funding through the Vice Deanship of Scientific Research Chairs.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CS | Content Store | IM | Interest Message |

| DM | Data Message | IFA | Interest Flooding Attack |

| DoS | Denial of Service | ICN | Information Centric Networking |

| DMS | Disaster Management System | NDN | Named Data Networking |

| FS | Fire Sensor | SL-1 | Smart Lab 1 |

| FE | Fire Exit | SL-2 | Smart Lab 2 |

| FIB | Forwarding Information Base | SC | Smart Campus |

| HC | Hop Count | TL | Threshold Limit |

References

- Din, I.U.; Almogren, A.; Guizani, M.; Zuair, M. A decade of Internet of Things: Analysis in the light of healthcare applications. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 89967–89979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, W.U.; Salam, T.; Almogren, A.; Haseeb, K.; Din, I.U.; Bouk, S.H. Improved Resource Allocation in 5G MTC Networks. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 49187–49197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.H.; Hameed, A.R.; ul Islam, S.; Khattak, H.A.; Din, I.U.; Rodrigues, J.J. Energy and delay efficient fog computing using caching mechanism. Comput. Commun. 2020, 154, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayyaba, S.K.; Khattak, H.A.; Almogren, A.; Shah, M.A.; Din, I.U.; Alkhalifa, I.; Guizani, M. 5G Vehicular Network Resource Management for Improving Radio Access Through Machine Learning. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 6792–6800. [Google Scholar]

- Awan, K.A.; Din, I.U.; Almogren, A.; Guizani, M.; Altameem, A.; Jadoon, S.U. Robusttrust—A pro-privacy robust distributed trust management mechanism for internet of things. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 62095–62106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, K.A.; Din, I.U.; Almogren, A.; Guizani, M.; Khan, S. StabTrust—A Stable and Centralized Trust-Based Clustering Mechanism for IoT Enabled Vehicular Ad-Hoc Networks. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 21159–21177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wazir, W.; Khattak, H.A.; Almogren, A.; Khan, M.A.; Din, I.U. Doodle-Based Authentication Technique Using Augmented Reality. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 4022–4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubbi, J.; Buyya, R.; Marusic, S.; Palaniswami, M. Internet of Things (IoT): A vision, architectural elements, and future directions. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2013, 29, 1645–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, T.; Almogren, A.; Akbar, M.; Zuair, M.; Ullah, I.; Javaid, N. Data Sharing System Integrating Access Control Mechanism using Blockchain-Based Smart Contracts for IoT Devices. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, S.; Shahzaad, B.; Azam, M.A.; Loo, J.; Ahmed, S.H.; Aslam, S. Hierarchical and flat-based hybrid naming scheme in content-centric networks of things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018, 5, 1070–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, A.; Shetty, S. Survey toward a smart campus using the internet of things. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 4th International Conference on Future Internet of Things and Cloud (FiCloud), Vienna, Austria, 22–24 August 2016; pp. 235–239. [Google Scholar]

- Dar, B.K.; Shah, M.A.; Islam, S.U.; Maple, C.; Mussadiq, S.; Khan, S. Delay-Aware Accident Detection and Response System Using Fog Computing. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 70975–70985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, A.; Arshad, S.; Azam, M.; Loo, J.; Ahmed, S.; Majeed, M.; Shah, S. Disaster management system aided by named data network of things: Architecture, design, and analysis. Sensors 2018, 18, 2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majeed, M.F.; Ahmed, S.H.; Muhammad, S.; Song, H.; Rawat, D.B. Multimedia streaming in information-centric networking: A survey and future perspectives. Comput. Netw. 2017, 125, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadeo, M.; Campolo, C.; Quevedo, J.; Corujo, D.; Molinaro, A.; Iera, A.; Aguiar, R.L.; Vasilakos, A.V. Information-centric networking for the internet of things: challenges and opportunities. IEEE Netw. 2016, 30, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haseeb, K.; Islam, N.; Almogren, A.; Din, I.U. Intrusion Prevention Framework for Secure Routing in WSN-Based Mobile Internet of Things. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 185496–185505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haseeb, K.; Din, I.U.; Almogren, A.; Islam, N.; Altameem, A. RTS: A Robust and Trusted Scheme for IoT-based Mobile Wireless Mesh Networks. IEEE Access 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccelli, E.; Mehlis, C.; Hahm, O.; Schmidt, T.C.; Wählisch, M. Information centric networking in the IoT: Experiments with NDN in the wild. In Proceedings of the 1st ACM Conference on Information-Centric Networking, Paris, France, 24–26 September 2014; pp. 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Masood, F.; Almogren, A.; Abbas, A.; Khattak, H.A.; Din, I.U.; Guizani, M.; Zuair, M. Spammer detection and fake user identification on social networks. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 68140–68152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xylomenos, G.; Ververidis, C.N.; Siris, V.A.; Fotiou, N.; Tsilopoulos, C.; Vasilakos, X.; Katsaros, K.V.; Polyzos, G.C. A survey of information-centric networking research. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2013, 16, 1024–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, M.S.; Khaliq, K.A.; Rais, R.N.B.; Qayyum, A. Information-centric networks: Categorizations, challenges, and classifications. In Proceedings of the 2014 23rd Wireless and Optical Communication Conference (WOCC), Newark, NJ, USA, 9–10 May 2014; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Din, I.U.; Hassan, S.; Khan, M.K.; Guizani, M.; Ghazali, O.; Habbal, A. Caching in information-centric networking: Strategies, challenges, and future research directions. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2017, 20, 1443–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Din, I.U.; Hassan, S.; Almogren, A.; Ayub, F.; Guizani, M. PUC: Packet Update Caching for energy efficient IoT-based Information-Centric Networking. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Din, I.U.; Kim, B.S.; Hassan, S.; Guizani, M.; Atiquzzaman, M.; Rodrigues, J.J. Information-centric network-based vehicular communications: Overview and research opportunities. Sensors 2018, 18, 3957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayes, A.; Morrow, M.; Lake, D. Internet of things implications on icn. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Conference on Collaboration Technologies and Systems (CTS), Denver, CO, USA, 21–25 May 2012; pp. 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, S.; Din, I.U.; Habbal, A.; Zakaria, N.H. A popularity based caching strategy for the future Internet. In Proceedings of the 2016 ITU Kaleidoscope: ICTs for a Sustainable World (ITU WT), Bangkok, Thailand, 14–16 November 2016; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Amadeo, M.; Campolo, C.; Molinaro, A. Internet of things via named data networking: The support of push traffic. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference and Workshop on the Network of the Future (NOF), Paris, France, 3–5 December 2014; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Alkhalifa, I.S.; Almogren, A.S. NSSC: Novel Segment Based Safety Message Broadcasting in Cluster-Based Vehicular Sensor Network. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 34299–34312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sourlas, V.; Tassiulas, L.; Psaras, I.; Pavlou, G. Information resilience through user-assisted caching in disruptive content-centric networks. In Proceedings of the 2015 IFIP Networking Conference (IFIP Networking), Toulouse, France, 20–22 May 2015; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, N.; Haseeb, K.; Almogren, A.; Din, I.U.; Guizani, M.; Altameem, A. A framework for topological based map building: A solution to autonomous robot navigation in smart cities. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, M.F.; Ahmed, S.H.; Dailey, M.N. Enabling push-based critical data forwarding in vehicular named data networks. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2016, 21, 873–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Zeadally, S.; Park, Y.J. A novel vehicular information network architecture based on named data networking (NDN). IEEE Internet Things J. 2014, 1, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanella, A.; Bui, N.; Castellani, A.; Vangelista, L.; Zorzi, M. Internet of things for smart cities. IEEE Internet Things J. 2014, 1, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqua, A.; Shah, M.A.; Khattak, H.A.; Din, I.U.; Guizani, M. iCAFE: Intelligent Congestion Avoidance and Fast Emergency services. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 99, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nour, B.; Sharif, K.; Li, F.; Biswas, S.; Moungla, H.; Guizani, M.; Wang, Y. A survey of Internet of Things communication using ICN: A use case perspective. Comput. Commun. 2019, 142–143, 95–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piro, G.; Cianci, I.; Grieco, L.A.; Boggia, G.; Camarda, P. Information centric services in smart cities. J. Syst. Softw. 2014, 88, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.H.; Bouk, S.H.; Kim, D.; Sarkar, M. Bringing Named Data Networks into Smart Cities. In Smart Cities: Foundations, Principles, and Applications; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 275–309. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, O.A.; Shah, M.A.; Din, I.U.; Kim, B.S.; Khattak, H.A.; Rodrigues, J.J.; Farman, H.; Jan, B. Leveraging named data networking for fragmented networks in smart metropolitan cities. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 75899–75911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochida, T.; Nozaki, D.; Okamoto, K.; Qi, X.; Wen, Z.; Sato, T.; Yu, K. Naming scheme using NLP machine learning method for network weather monitoring system based on ICN. In Proceedings of the 2017 20th International Symposium on Wireless Personal Multimedia Communications (WPMC), Bali, Indonesia, 17–20 December 2017; pp. 428–434. [Google Scholar]

- De Cola, T.; Gonzalez, G.; Mujica, V.E. Applicability of ICN-based network architectures to satellite-assisted emergency communications. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM), Washington, DC, USA, 4–8 December 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Amadeo, M.; Campolo, C.; Molinaro, A. Multi-source data retrieval in IoT via named data networking. In Proceedings of the 1st ACM Conference on Information-Centric Networking, Paris, France, 24–26 September 2014; pp. 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Afanasyev, A.; Moiseenko, I.; Zhang, L. ndnSIM: NDN Simulator for NS-3; Tech. Rep; University of California: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Su, Z.; Xu, Q.; Qi, Q.; Yang, T.; Li, J.; Fang, D.; Han, B. Delivering mobile social content with selective agent and relay nodes in content centric networks. Peer-to-Peer Netw. Appl. 2017, 10, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqa, A.; Shah, M.A.; Maryam, H.; Arshad, S.; Wahid, A. EMCA: Efficient multicasting and collision avoidance in CC-MANETs. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 13th International Conference on Emerging Technologies (ICET), Islamabad, Pakistan, 27–28 December 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa, T.; Tara, Y.; Ryu, K.; Koizumi, Y. Emergency message delivery mechanism in NDN networks. In Proceedings of the 3rd ACM Conference on Information-Centric Networking, Kyoto, Japan, 26–28 September 2016; pp. 199–200. [Google Scholar]

- Shih, C.S.; Hsiu, P.C.; Chang, Y.H.; Kuo, T.W. Framework designs to enhance reliable and timely services of disaster management systems. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Computer-Aided Design, Austin, TX, USA, 7–10 November 2016; p. 107. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.H.; Kim, D. Named data networking-based smart home. Ict Express 2016, 2, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattak, H.A.; Ameer, Z.; Din, U.I.; Khan, M.K. Cross-layer design and optimization techniques in wireless multimedia sensor networks for smart cities. Comput. Sci. Inf. Syst. 2019, 16, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toor, A.; ul Islam, S.; Sohail, N.; Akhunzada, A.; Boudjadar, J.; Khattak, H.A.; Din, I.U.; Rodrigues, J.J. Energy and performance aware fog computing: A case of DVFS and green renewable energy. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 101, 1112–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Khan, A.; Javaid, N.; Hussain, H.M.; Abdul, W.; Almogren, A.; Alamri, A.; Azim Niaz, I. An optimized home energy management system with integrated renewable energy and storage resources. Energies 2017, 10, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almogren, A.S. Intrusion detection in Edge-of-Things computing. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 2020, 137, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Han, L.; Park, Y.; Lee, J.B.; Kim, J.; In, H.P. An energy-efficient routing protocol for CCN-based MANETs. Int. J. Smart Home 2013, 7, 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Amadeo, M.; Campolo, C.; Iera, A.; Molinaro, A. Information Centric Networking in IoT scenarios: The case of a smart home. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE international conference on communications (ICC), London, UK, 8–12 June 2015; pp. 648–653. [Google Scholar]

- Seedorf, J.; Kutscher, D.; Gill, B.S. Decentralised interest counter aggregation for ICN in disaster scenarios. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Globecom Workshops (GC Wkshps), Washington, DC, USA, 4–8 December 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Maryam, H.; Shah, M.A.; Arshad, S.; Siddiqa, A.; Wahid, A. TFS: A reliable routing protocol for Vehicular Content Centric Networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 13th International Conference on Emerging Technologies (ICET), Islamabad, Pakistan, 27–28 December 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Aamir, M. Content-priority based interest forwarding in content centric networks. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1410.4987. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, R.; Rehman, M.A.U.; Kim, B.S. Hierarchical Name-Based Mechanism for Push-Data Broadcast Control in Information-Centric Multihop Wireless Networks. Sensors 2019, 19, 3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razouqi, Q.; Boushehri, A.; Gaballah, M.; Alsaleh, L. Extensive simulation performance analysis for DSDV, DSR and AODV MANET routing protocols. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE 27th International Conference on Advanced Information Networking and Applications Workshops, Barcelona, Spain, 25–28 March 2013; pp. 335–342. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).