Abstract

Background/Objectives: Along the Tyrrhenian coast of central Italy, multilayered caves have yielded significant Neanderthal-era human remains. Recent excavations at Guattari Cave uncovered hominin fossils dated to approximately 66–65 ka, revealing a population with notable morpho-anatomical variability exhibiting both plesiomorphic (primitive) and autapomorphic (derived) traits. Methods: Here we present detailed morphometric and comparative analyses of cranial, dental, and postcranial remains, demonstrating affinities with Homo erectus (sensu stricto [s.s.] and lato [s.l.]), Proto-Neanderthals, classical Neanderthals, and Homo sapiens. Results: These findings indicate notable morpho-anatomical variability among the Guattari Cave hominin remains, with affinities to multiple hominin lineages during the Middle and Late Pleistocene. Pleistocene. Conclusions: The Guattari Cave assemblage thus contributes to our understanding of Eurasian hominin diversity and evolutionary dynamics, highlighting the Mediterranean as a region of interest for studying the phyletic continuity and diversity preceding modern humans.

1. Introduction

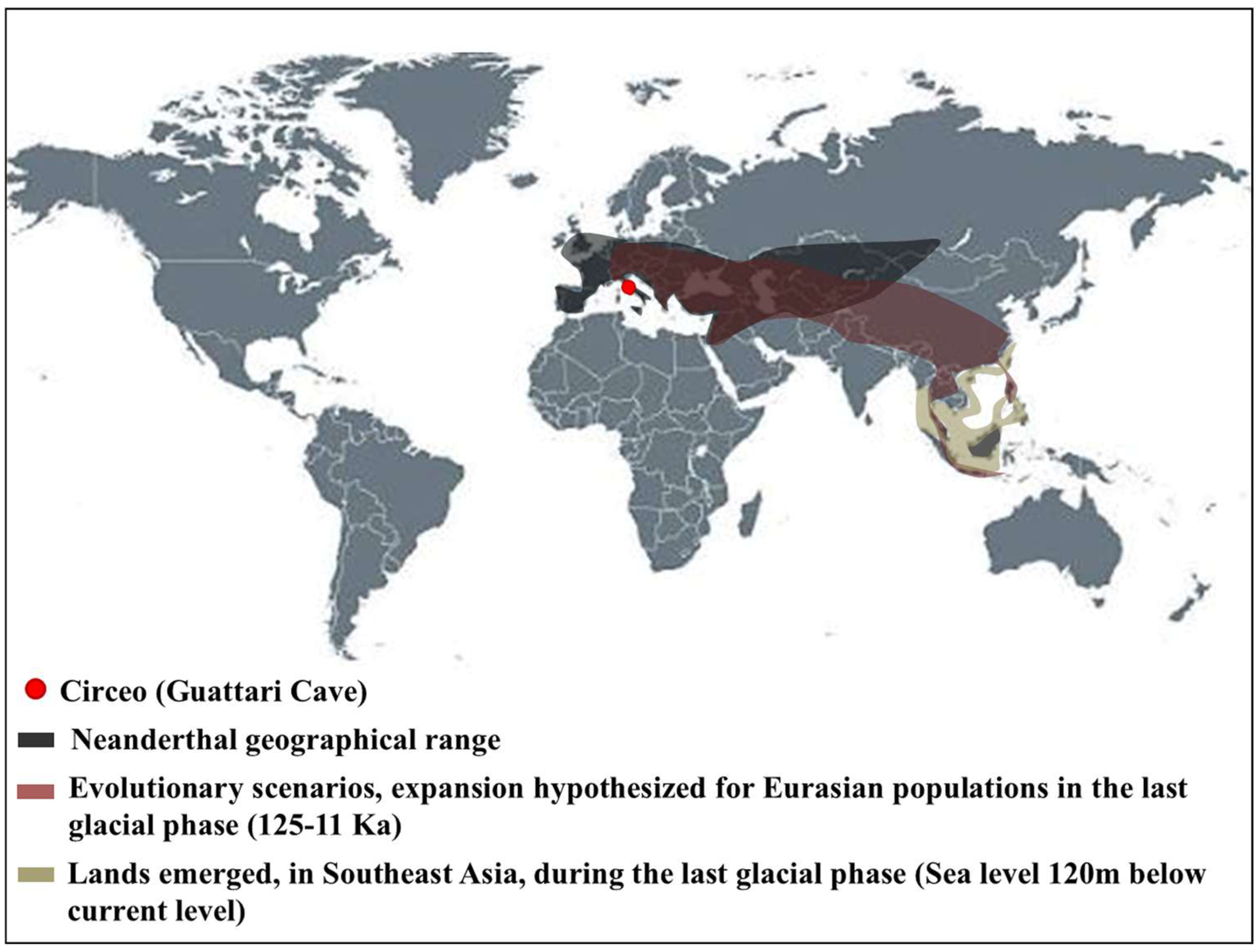

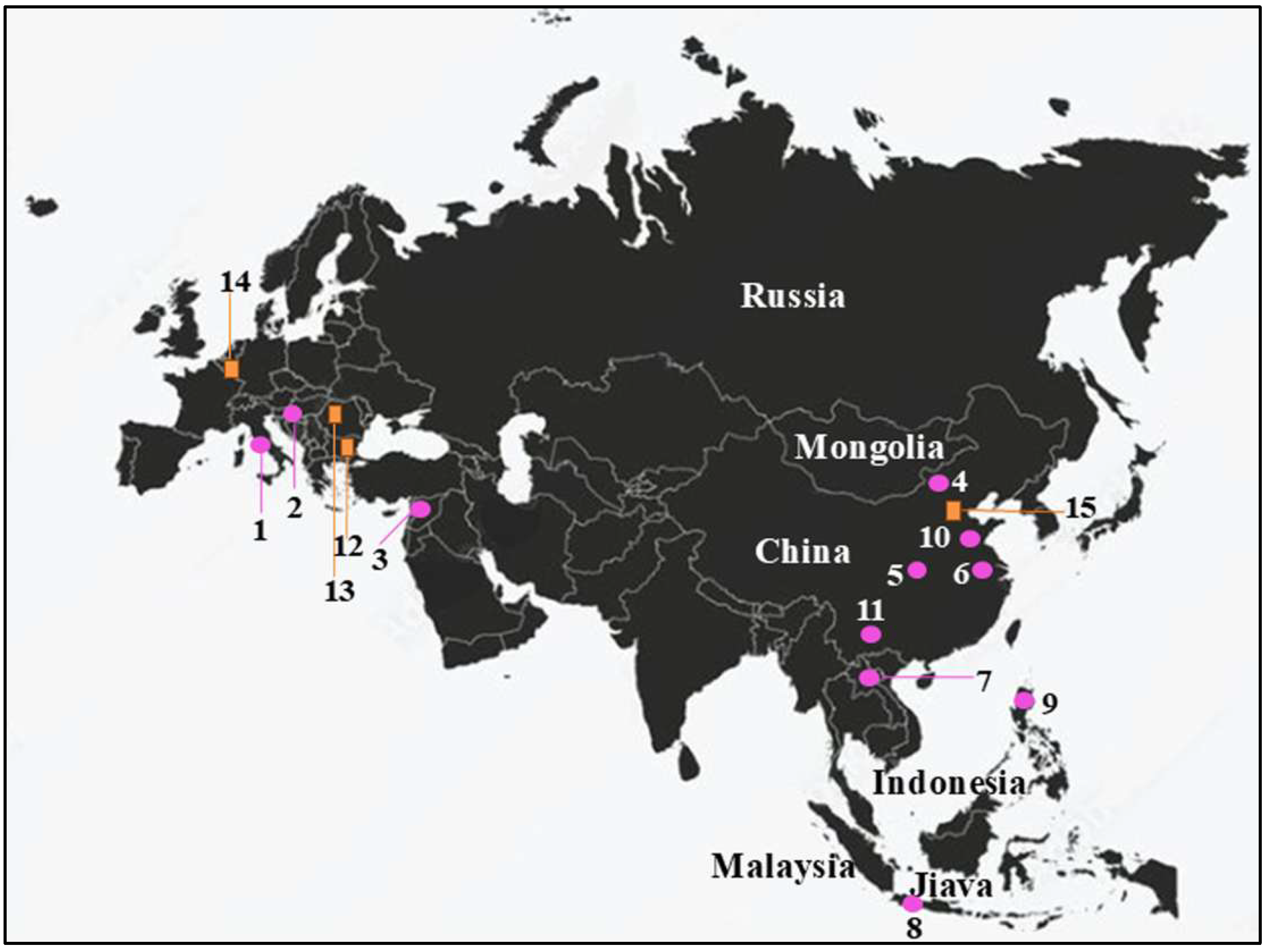

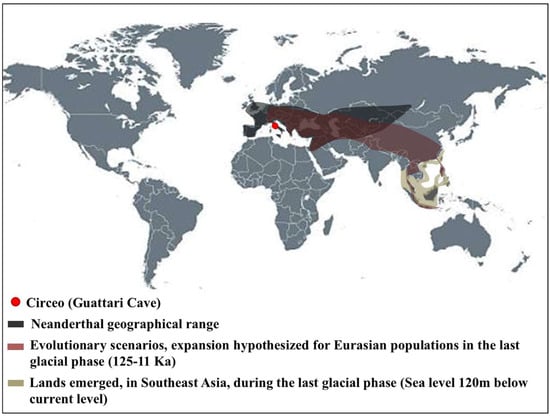

In recent years, significant progress has been made in understanding human populations during the Middle and Late Pleistocene. Advances in dating techniques, as well as paleoenvironmental, paleoecological, and genetic reconstructions, have enabled a more detailed reconstruction of population movements and interactions during this period, shedding new light on key aspects of human evolution. During the Pleistocene, Neanderthals coexisted in Eurasia with other hominin species, including “H. erectus”, “Homo heidelbergensis”, Denisovans (from the Altai and southern Siberia) [1], and “H. sapiens”, as well as more recently discovered or debated species such as “Homo luzonensis”, “Homo floresiensis”, and the controversial “Homo longi”. Throughout their long history, Neanderthals, like other contemporary human groups, faced abrupt climatic and environmental changes [2,3,4] and adapted to these challenges by seeking regions with favorable climates and abundant resources. As a result, they dispersed widely across Eurasia, from Gibraltar to the Altai Mountains, and from the Middle East to Britain and the Mediterranean. The Tyrrhenian coast of Lazio (central Italy) features numerous caves between the Circeo and Gaeta promontories, many of which show evidence of human activity; however, only three—Fossellone Cave, Breuil Cave, and Guattari Cave—have yielded human remains. Guattari Cave is located approximately one hundred meters from the Tyrrhenian Sea, on the eastern side of the Circeo promontory (Figure 1). In the first half of the twentieth century, a complete Neanderthal skull (Circeo 1) and two mandibles (Circeo 2 and Circeo 3) were discovered there by chance [5,6]. More recently, archeological excavations conducted between 2019 and 2022 uncovered an additional 15 human remains, representing a remarkable addition to the Italian Middle Pleistocene record and making a significant contribution to European paleoanthropological research.

The Role of Morphology in the Absence of Genomic Data

In contexts lacking ancient DNA (aDNA), such as the specimens examined in this study, morphological analysis represents the primary tool for phylogenetic reconstruction and taxonomic delimitation.

In this study, a comparative morphometric analysis was conducted to identify morphological divergences and affinities along the entire evolutionary lineage of hominins, starting from a phylogenetic hypothesis that reconciles some genetic results reported in the recent literature.

Morphology provides observable and quantifiable characteristics (traits) that, when properly coded, can be used in cladistic analyses to infer evolutionary relationships. In the absence of molecular data, this approach becomes essential for systematics and evolutionary reconstruction.

Application scenarios include the following:

- Fossil species and extinct taxa: In paleontological specimens, DNA is generally degraded or absent, as often occurs in fossil remains found along the Italian coastal area. Morphology therefore becomes the only source of information for placing fossils within phylogenetic trees.

- Functional and ecological analysis: Morphological structures reflect functional adaptations and selective pressures, providing clues about ecology and behavior.

The main advantages of morphometric analysis are universality, applicability to both living and fossil taxa, and operational immediacy. Conversely, the limitations include evolutionary convergence, phenotypic plasticity, and intraspecific variability, which can reduce phylogenetic resolution.

In the absence of molecular data, morphology is not merely an alternative but an indispensable component for systematics and evolutionary reconstruction. Integrating morphological characteristics with ecological and stratigraphic data helps mitigate intrinsic limitations and achieve more robust inferences.

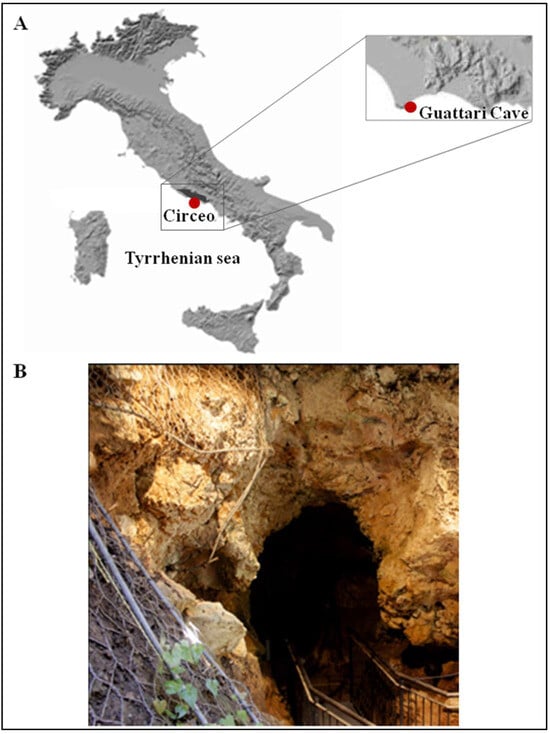

Figure 1.

(A) Location of Guattari Cave (map of digital elevation). (B) The cave entrance.

Figure 1.

(A) Location of Guattari Cave (map of digital elevation). (B) The cave entrance.

2. Archeological Background

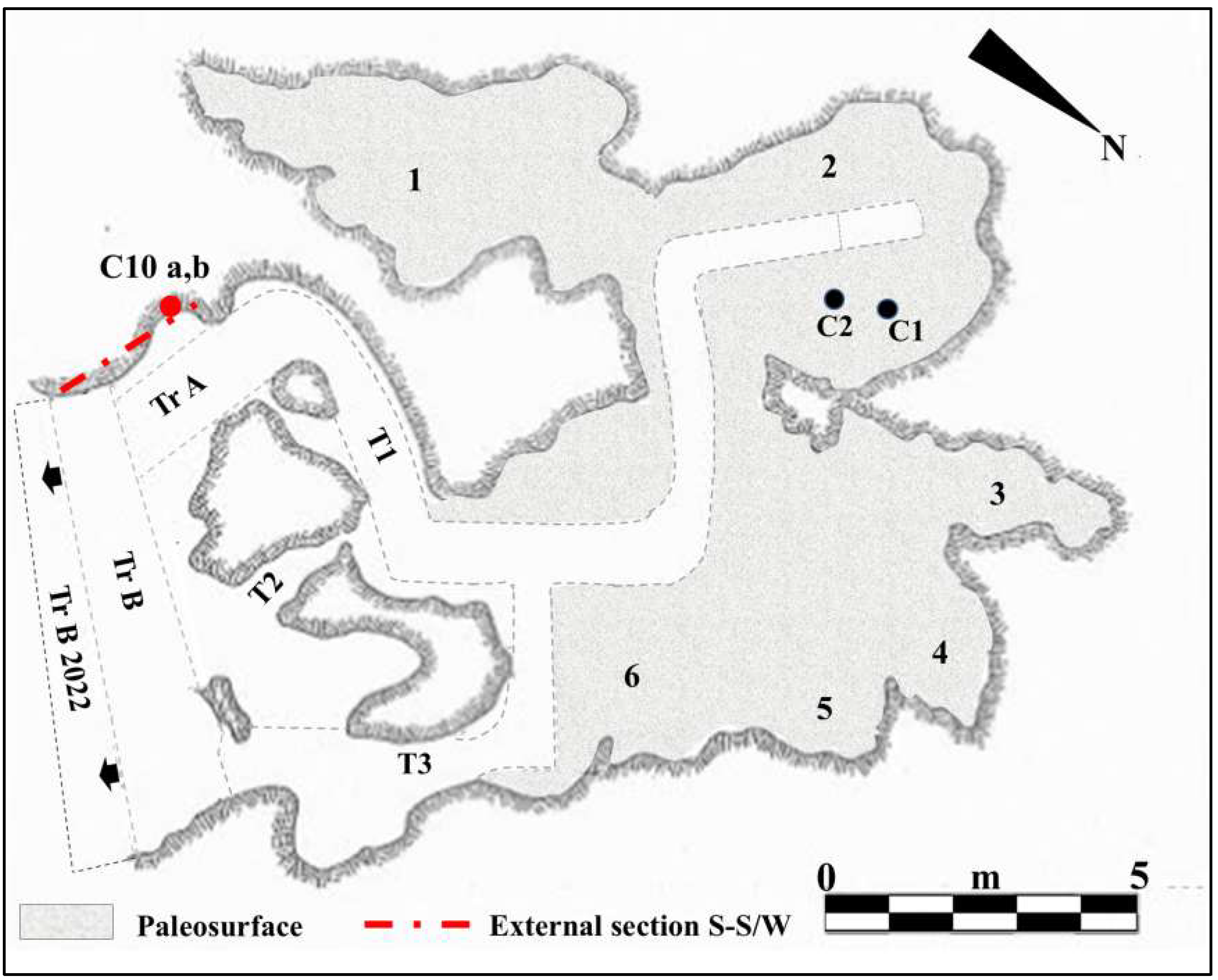

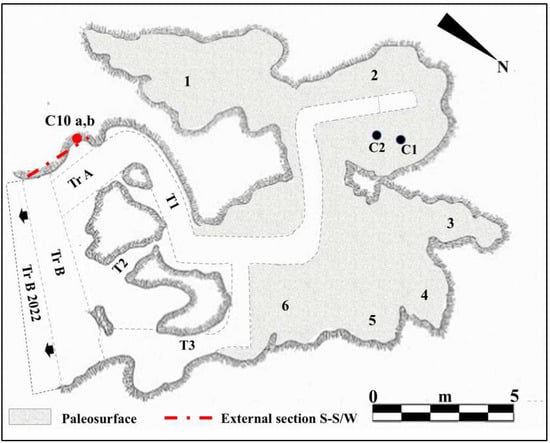

The entrance to Guattari Cave is located approximately 7 m above sea level on the eastern slopes of Monte Morrone, a low hill on the Circeo promontory (Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure S1). The cave was discovered by chance on 24 February 1939, during construction work. In an internal chamber later named “Antro dell’Uomo”, a Neanderthal skull and mandible (Circeo 1, C1 and Circeo 2, C2) were found resting on an ancient ground surface (paleosurface). A second Neanderthal mandible, Circeo 3 (C3) [7,8], was discovered outside the cave in 1950. Segre [9] reported that the human remains were located near a deposit of bone-rich breccia (ossiferous breccia) still attached to the rock face above the entrance to tunnel 1 (Figure 2). Excavations began immediately after the initial discovery and continued, with varying intensity, until the 1950s, involving both the external and internal areas of the cave (Supplementary Figure S2) through the creation of several trenches (Figure 2). Throughout this area, excavations appear to have reached the Tyrrhenian fossil beach at the base of the Pleistocene sequence, extending more than a meter below the original surface.

Figure 2.

Planimetry of Guattari Cave. Internal area of the cave showing the paleosurface of level 2. 1. “Antro del Laghetto”; 2. “Antro dell’Uomo” with the localization of the human specimens: Circeo 1 (C1) skull and Circeo 2 (C2) mandible, found in 1939 (black circles); 3. “Antro del Bue”; 4. “Antro della Iena”; 5. “Antro del Rinoceronte”; 6. “Antro del Cervo”. External area of the cave: recently investigated sector (black arrows), trench B (Tr B 2022). Trenches A and B (Tr A and Tr B) and tunnels 1, 2, and 3 (T1-3), historical excavation Blanc, Cardini, and Segre of the 1930s and 1940s. Section S-S/W highlighted by Blanc in 1939 [5] and recently investigated (mixed line with two dots and long red line) with localization of the human specimen, Circeo 10 (C10, red circle), found during the cleaning investigations. Modified after Segre [9] and Rolfo et al. [10].

2.1. The Excavation of the Internal Deposit “Antro Del Laghetto”

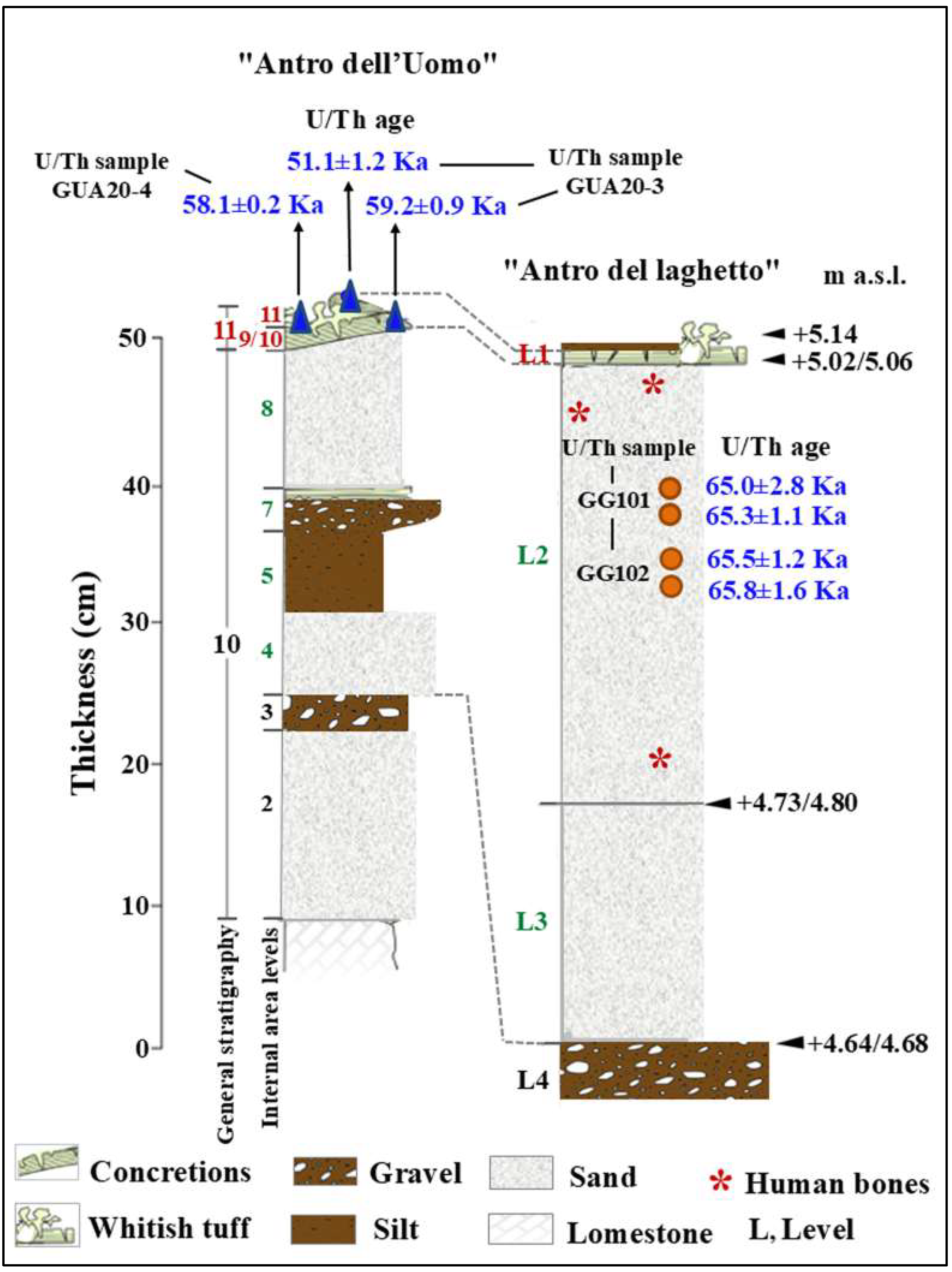

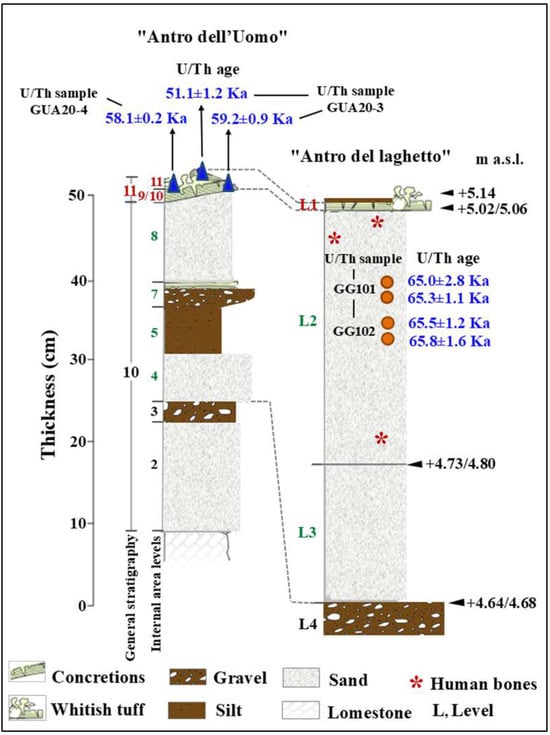

On 11 October 2019, under the direction of the Superintendence of Archaeology, Fine Arts and Landscape for the provinces of Frosinone and Latina, new systematic research began in the Guattari Cave, which focused mainly on the area called “Antro del Laghetto” (due to the presence of a small accumulation of water, especially in the winter season). The excavation encompassed the entire stratigraphic deposit, which consists of a complex succession of overlapping layers with a thickness ranging from 47 to 102 cm. A total of 25 Stratigraphic Units (SUs) were identified, allowing the distinction of four different levels, each with distinct geological and archeological characteristics (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Stratigraphy of the “Antro dell’Uomo” and “Antro del laghetto”. Modified after Segre [9] and Rolfo et al. [10]. L1/11. Tuffaceous coralloid concretion and whitish tuff and bone partially covered by the flowstone; 8 and 4. Mammal bone and coprolites; L2. Stalagmite concretions, pebbles of limestone, mammal bones, coprolites, lithic artifacts, and human bones (red asterisk); L3. Tuffaceous flowstone, mammal bones, coprolites, and lithic artifacts.

Level 1. The surface layer corresponds to the stalagmitic crust, of modest thickness, that covers the entire surface of the “Laghetto”, formed over time by the precipitation of calcium carbonate from the groundwater that seasonally floods the area.

Level 2. Layer characterized by a paleosurface, with an average thickness of 40 cm, with skeletal remains distributed randomly over the entire investigated area.

Level 3. This level is strongly altered by phosphatization, resulting in faunal remains that are badly damaged by the chemical alteration of the sediment. Lithic artifacts were also recovered from this level; the lithic industry present, known as the Pontinian, represents a regional variant of the Mousterian stone tool tradition [11,12].

Level 4. Although this was the last level to be excavated, it is not the final layer in the stratigraphic sequence. It consists of a series of stalagmitic crusts of varying development, some of which have been altered by chemical processes affecting the calcium carbonate. From an archeological perspective, this level is sterile, meaning it contains no evidence of human activity.

According to Rolfo et al. [10], the low overall number of lithic artifacts in the “Antro del Laghetto” succession (28 in level 3 and 7 in level 2) suggests a limited human presence inside the cave. In contrast, evidence of human activity is well documented in the more external and older deposits [9,10].

The paleosurface of level 2 of the “Laghetto” area, unlike the other areas of the cave, was not visible because it was covered and incorporated, in its superficial portion, by the level 1 stalagmitic concretion.

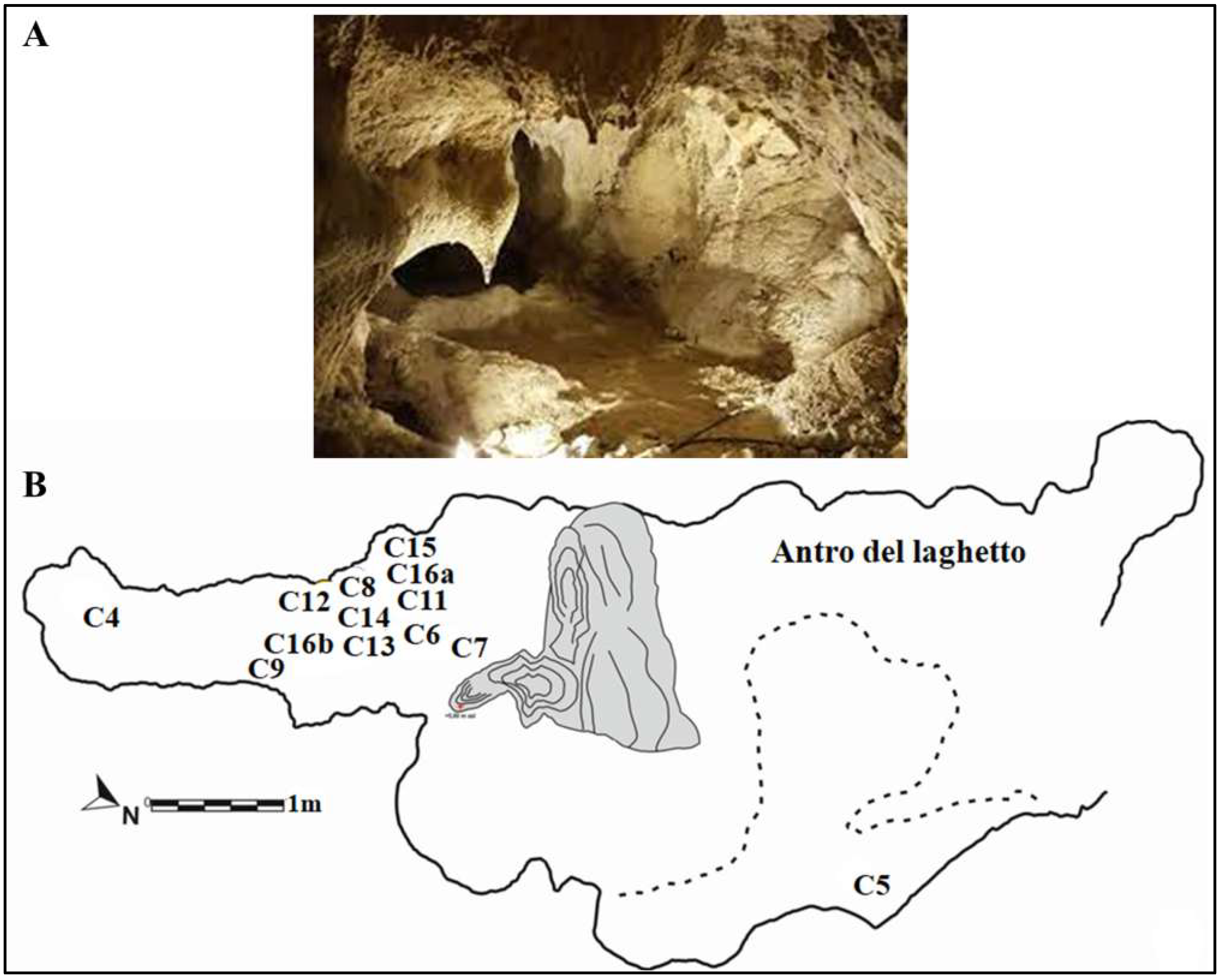

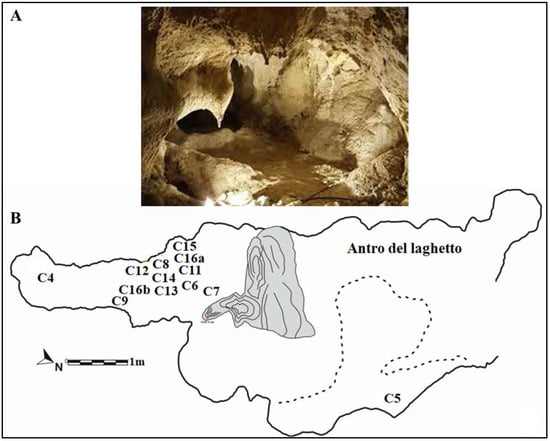

During the excavation of level 2, several human remains (Figure 4B) were found scattered among the faunal remains in various areas of the “Laghetto,” all located on the paleosurface (Figure 5). A significant number of human skeletal fragments were recovered, and images documenting the discovery of some of these are presented in Figure 6.

Figure 4.

(A) “Antro del Laghetto”. (B) Planimetry showing the paleosurface of “Antro del Laghetto” level 2. Localization of the human specimens (Cn) discovered during recent excavations. They are all stratigraphically placed within level 2. Modified after Rolfo et al. [10].

Figure 5.

Level 2: (A) paleosurface of the “Laghetto” area; (B) paleosurface of the cave.

Figure 6.

Level 2 human remains under excavation. 1, One of the two hemifrontals of Circeo 4; 2, Mandible, Circeo 6 (A), and femur, Circeo 11 (B); 3, Calvarium Circeo 5; 4, Occipital bone, Circeo 8 (black circle).

It is still unclear whether the abundance of bone remains, which in some areas form accumulations over 60 cm thick, is the result of direct predatory activity by animals or the natural movement of cave deposits, causing material to slide from northeast to southwest.

The faunal remains, found together with the human remains, which characterize the entire paleosurface of level 2 of the cave (Figure 5), include red deer (Cervus elaphus), which is the dominant species, followed by the spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta) and the aurochs (Bos primigenius). Other identified species include wild horse (Equus ferus) and wild boar (Sus scrofa), rare fallow deer (Dama dama), two bear species (Ursus spelaeus and Ursus arctos), a few remains of a rhinoceros species (probably Stephanorhinus hemitoechus), abundant giant deer (the Irish elk, Megaloceros giganteus), rare elephant (Palaeoloxodon antiquus) and hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius), roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), leopard (Panthera pardus), ibex (Capra ibex), chamois (Rupicapra sp.), cave lion (Panthera spelaea), wild cat (Felis silvestris), European hemione (Equus hydruntinus), hare (Lepus sp.), fox (Vulpes vulpes) and wolf (Canis lupus), and at least one mustelid in addition to sparse birds and micromammals [13].

2.2. The Excavation of the External Deposit

Archeological investigations were also carried out outside the cave, focusing on the residual portions of the sections left by the Blanc excavation of 1939–1950 and on the limited areas spared by past excavations. The new interventions began with the cleaning and documentation of the sections highlighted by Blanc in 1939, both the one identified as section S-S/W, and the east and west sections of trench B (Figure 2).

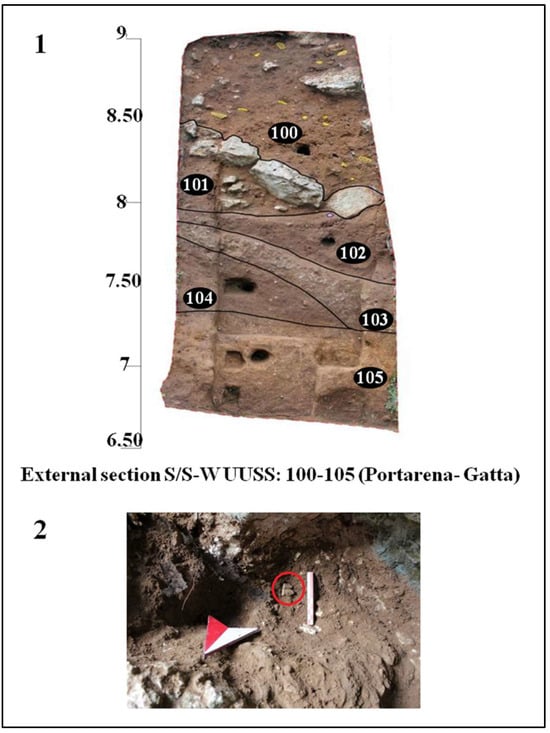

The aim of the investigations was to highlight and analyze the stratigraphic sequence of the external deposit (Figure 7):

- (a)

- (b)

- A very compact underlying level concretioned with rare lithic industry.

- (c)

- A compact sandy level with rare lithic industry.

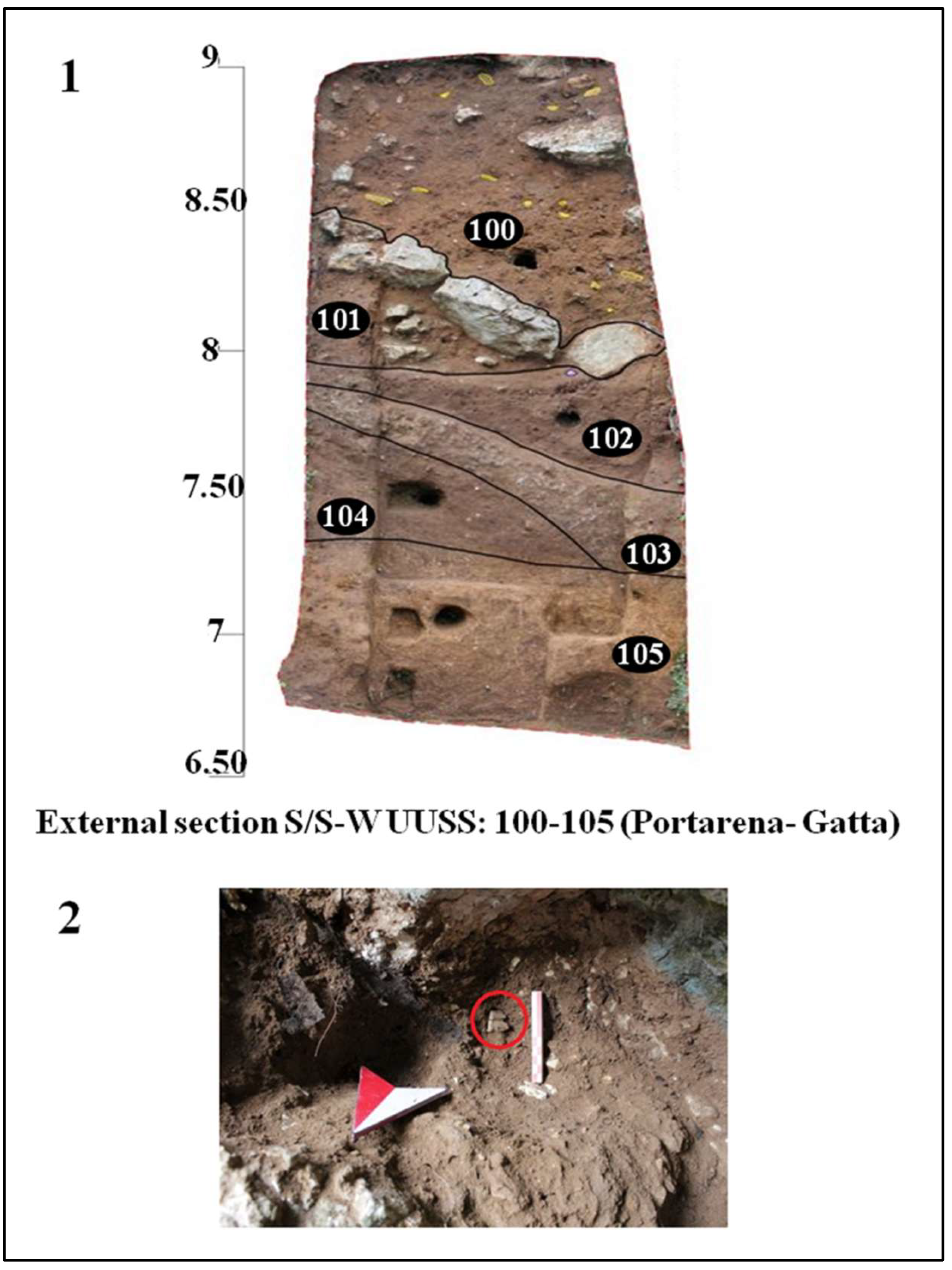

Figure 7.

External area. 1, Section S/S/W; 2, detail of the excavation of the two human teeth (red circle, Circeo 10) in the south section.

Figure 7.

External area. 1, Section S/S/W; 2, detail of the excavation of the two human teeth (red circle, Circeo 10) in the south section.

Excavation of the remaining portions of the deposit in front of the cave, which were spared by previous investigations, has confirmed the findings of earlier excavations: a series of levels with a high concentration of charcoal, faunal remains, and lithic artifacts. The entire stratigraphic complex, which is over 50 cm deep, is characterized by abundant faunal remains (many of which are burnt) and a high concentration of charcoal and lithic industry [9,10], with geochronological data placing these deposits between approximately 121 ka and 105 ka [14].

The discovery of charcoal and burnt animal bones suggests the presence of a structured hearth, with burnt soil fragments, in the immediate vicinity. These findings indicate an initial and oldest phase of structured human activity in the atrial portion and the external area in front of the cave, particularly in the sector in front of trench B (Figure 2). In contrast, a second and much later phase of hominin presence is documented mainly by the occurrence of human skeletal remains, found among numerous faunal remains, in the internal area of the cave.

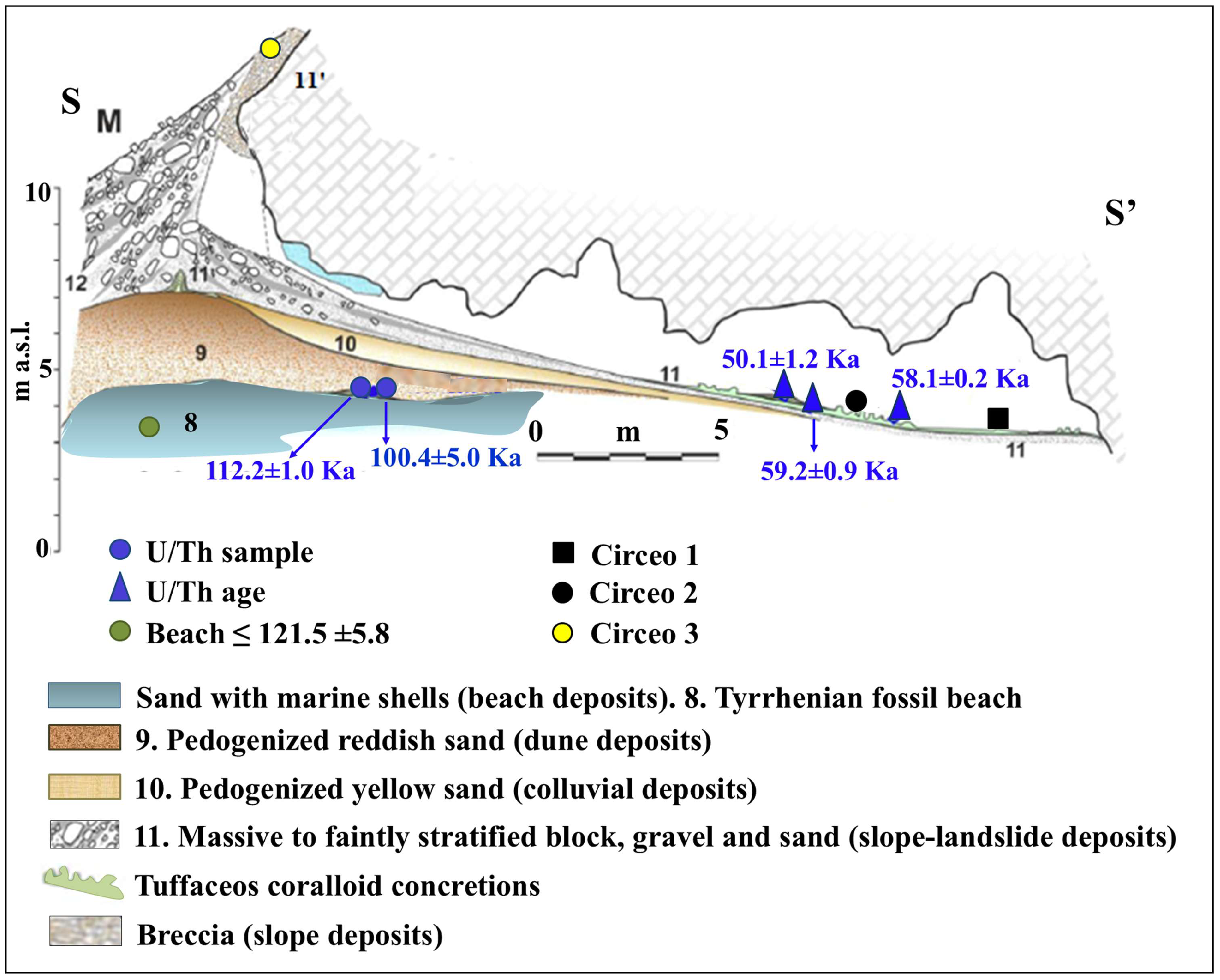

2.3. Chronology

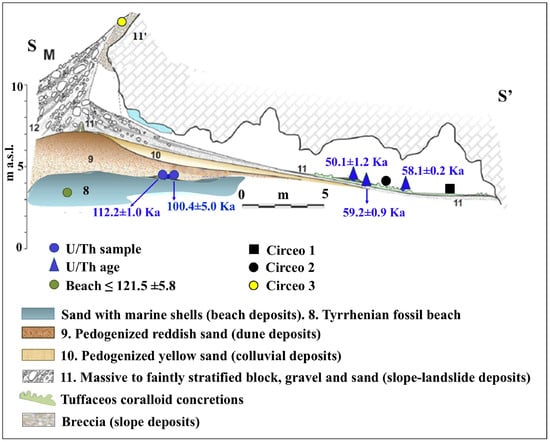

The general stratigraphy of the cave, as summarized by Segre [9], divides the internal and external deposits into several units, with the lowest unit consisting of fossil beach deposits (Figure 8 and Figure 9). The attribution of this deposit to Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) 5.5 was recently confirmed by 40Ar/39Ar dating of detrital sanidine extracted (Figure 8) from the biodetritic deposit at the base of the cave fill, which yielded an age of 121.5 ± 5.8 ka [10,11]. The basal age of the internal continental fill, determined from a sample of the layer covering the basal marine deposit (Figure 8 and Figure 9), provided two dates: 112.6 ± 0.9 ka and 100.4 ± 5.9 ka [10]. Therefore, the entire internal continental clastic succession of the cave fill developed between the age of the flow overlying the beach deposits (112.2 ± 1.0 ka to 100.4 ± 5.0 ka) and before 59.9 ± 0.8 ka, the age of the oldest coralloid concretions [10,15].

Figure 8.

Simplified geological section of Guattari Cave, with the localization of the historical remains and of the U/Th samples described in the text. Green circle (level 8), 40Ar/39Ar dating of detrital sanidine, extracted from the biodetritic deposit occurring at the base of the cave fill (Stratigraphic Unit 10 [SU10]), in Marra et al. [11], yielded ages of 121 ± 5 ka. Modified after Segre [9] and Rolfo et al. [10].

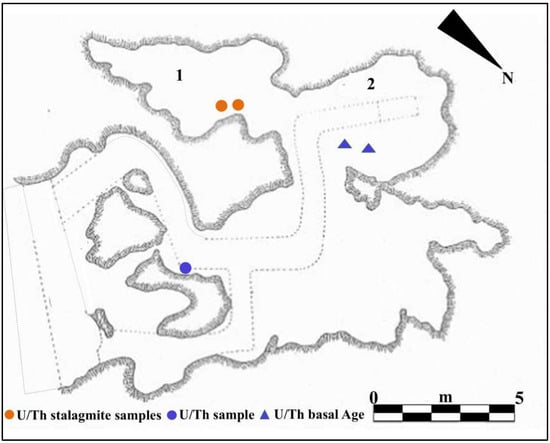

Figure 9.

U/Th geochronology (method applied to corals or speleothems): from the “Antro del Laghetto”, (1) two stalagmite samples (orange circles); from the “Antro dell’Uomo”, (2) two samples of the surface coralloid concretion (blue triangles); basal age of the internal continental infilling of the cave, U/Th samples of the basal marine deposit (blue circle). Modified after Segre [9] and Rolfo et al. [10].

For the geochronology of the “Antro del Laghetto”, two stalagmites were selected within level 2, with accumulation of human and animal bones, and two samples were taken of coralloid calcitic concretion which covers the upper surface of the “Antro dell’Uomo” [10] (Figure 3 and Figure 9). The coralloid concretion taken from the skull of C1 (“Antro dell’Uomo”) was previously dated, with the isochronous U/Th method, by Schwarcz et al. [15].

The results indicate that the middle-upper succession of the “Antro del Laghetto” (level 2) dates to approximately 66–65 ka (MIS 4), while the upper portion of the “Antro dell’Uomo” has a basal age of 59.17 ± 0.85 ka and a maximum age of 51.1 ± 1.2 ka [10] (Figure 3). Overall, the new chronological data for the surface coralloid concretion are consistent with the earlier dating of approximately 57–50 ka by Schwarcz et al. [15]. The middle-upper part of the “Antro del Laghetto” is precisely dated by four concordant U/Th measurements to a narrow interval of ~66–65 ka, corresponding to the Greenland Stadial (GS) 19.1 [10,16], one of the most severe periods of the MIS 4 glacial stage. In regions such as Apulia, Abruzzo, and southern Italy, this interval coincides with drier, more open, and arid conditions [10]. In summary, the stratigraphic sequence of Guattari Cave was formed between MIS 5.5 and MIS 3, that is, between the high Tyrrhenian marine stand (~125 ka) and the landslide that closed the cave after 50 ka [17]. Thus, like other coastal caves affected by sea-level fluctuations, Guattari Cave may have become accessible to humans from the end of MIS 5.5, around 120 ka [18].

3. Materials and Methods

Guattari Cave has yielded numerous human remains alongside a large assemblage of fauna through both historical and recent excavations. The bones, found in a randomly mixed context, were initially treated as a single assemblage. Specimens were separated into faunal and human remains, with all human skeletal elements identified, cataloged by element type, and accompanied by all available contextual information. Unidentified specimens were excluded from analysis. To preserve the integrity of the remains, restoration and removal of concretions were not performed.

The overall number of human fossil remains, first and second discoveries, consist of 18 cranial and postcranial remains. The laboratory code adopted was C (Circeo) and the numbering, progressive, starts taking into account the findings of 1939–1950 (C1, C2, C3). Analysis of the minimum number of individuals (NMI) was carried out on the most represented bone segment (skull). The result identifies the presence of at least four individuals (C1, C4, C5, and C8). The skeletal remains from the recent discovery (2019–2022) include a fronto-parietal portion, “Circeo 4” (C4); a calvarium, “Circeo 5” (C5); a mandible incomplete, “Circeo 6” (C6); a femoral diaphysis, “Circeo 7” (C7); an occipital bone, “Circeo 8” (C8); an incomplete upper maxillary, “Circeo 9” (C9); and finally a right coxal bone, “Circeo 16 b” (C16b), and a left, “Circeo 16 a” (C16a), incomplete and probably belonging to two different individuals female. Presence/absence of pathological conditions, trauma, or taphonomic changes were observed. The mixed nature of the discovery led to a comparative analysis of the remains, among themselves, visually assessing characteristics such as shape, size, tissue proportions, developmental stage, and presence of anatomical features and pathological conditions. This assessment revealed no obvious links. The new human remains are described and compared with the human remains from 1939–1950 and with a large sample of diachronic and synchronic Homo fossils from the Pleistocene (Supplementary Table S1) distributed over different geographical areas (Europe, Africa, and Asia) to evaluate phenetic affinities and evolutionary relationships. The presence/absence of non-metric morphological traits presented in Supplementary Table S2 and described in the text was detected.

The skeletal measurements of the hominins (Supplementary Tables S3–S10) were taken with composite digital calipers following the suggestions of Martin [19]. Sex of Circeo 16 (a, b) was determined according to the standards of Buikstra and Ubelaker [20].

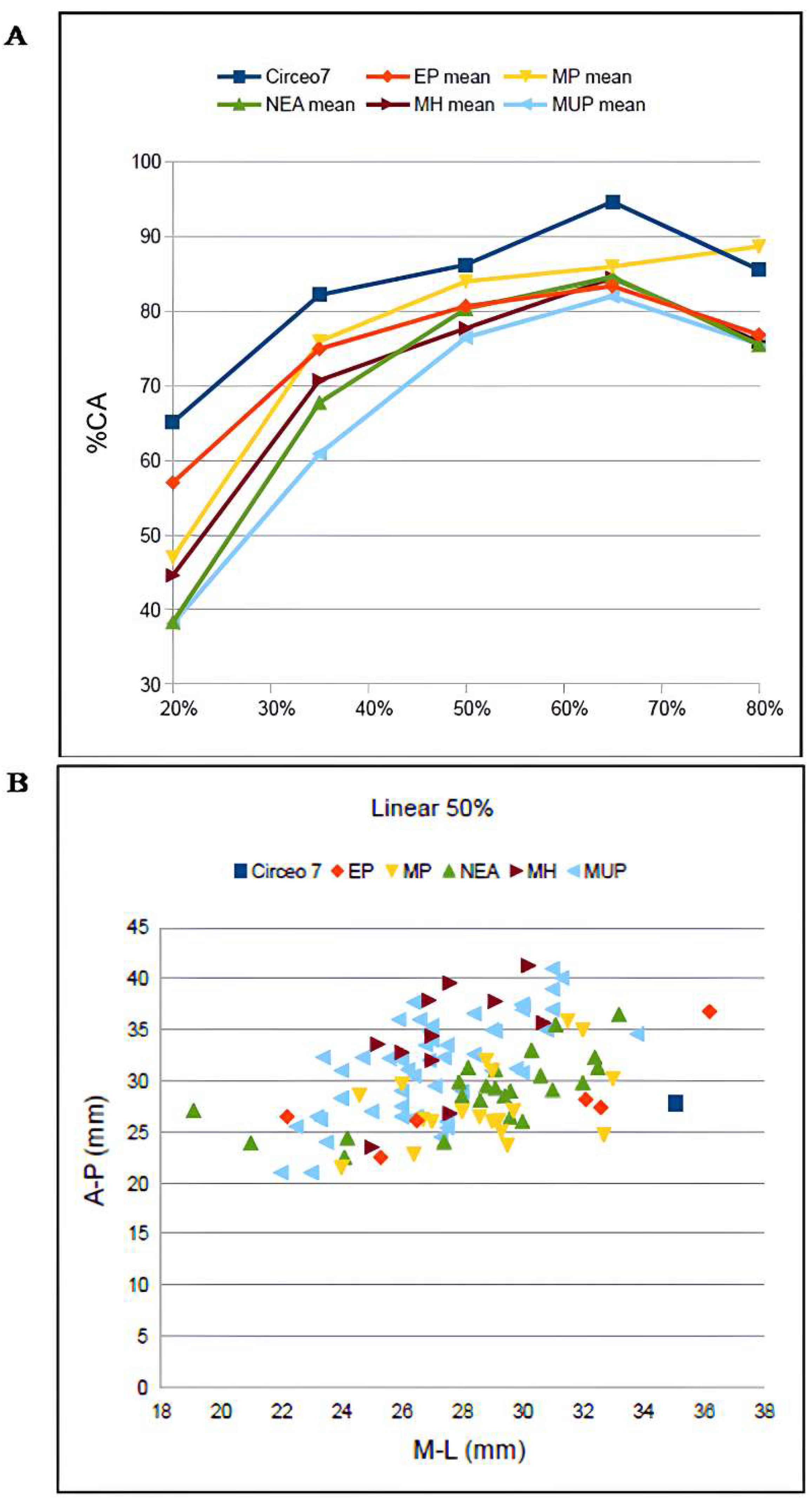

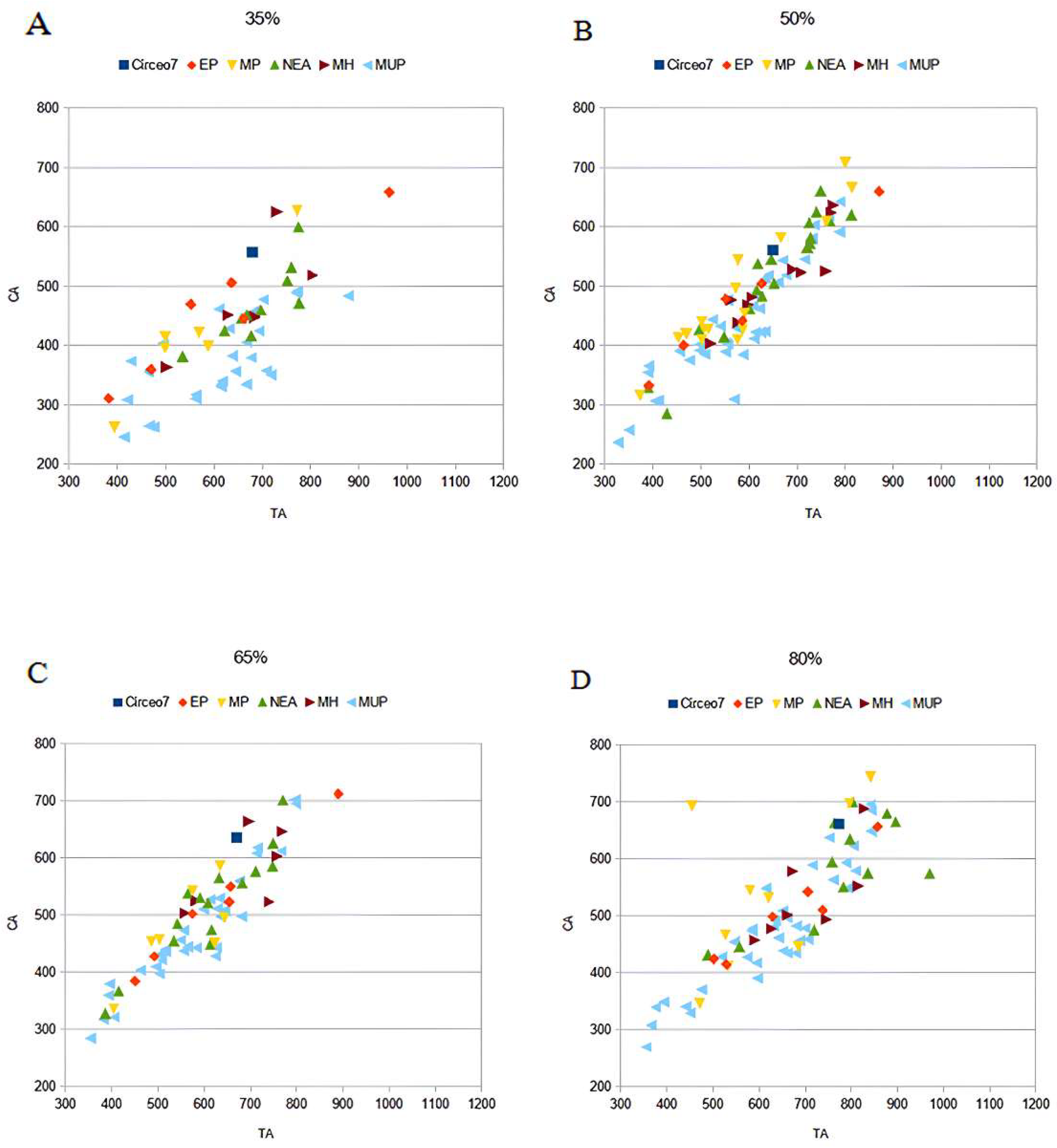

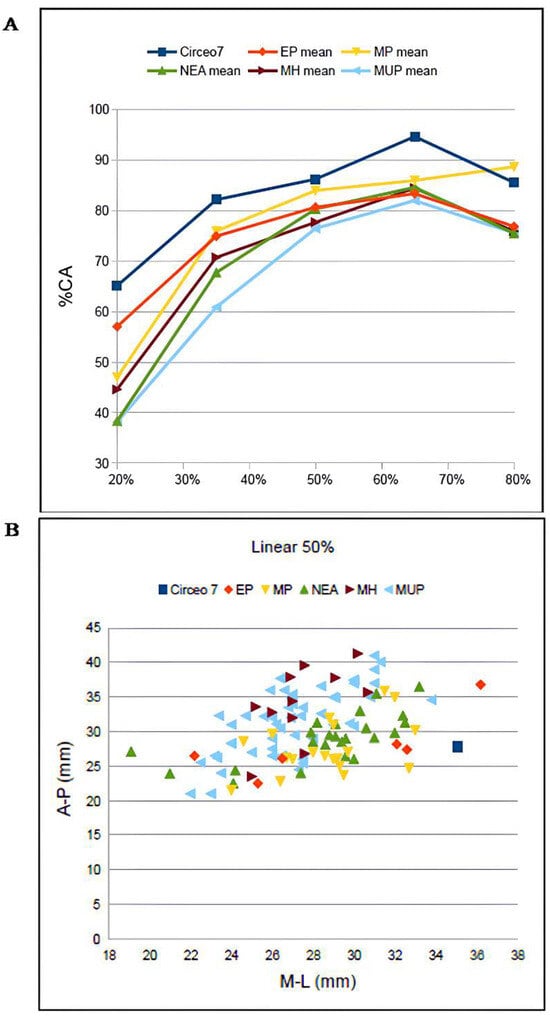

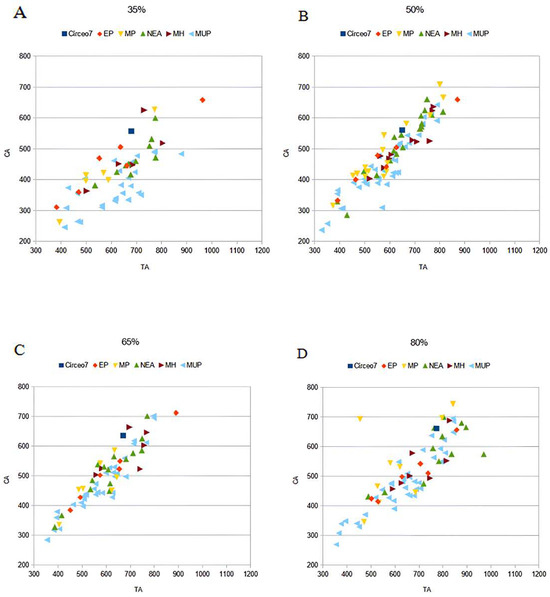

CT analysis of the Circeo 7 femur was performed at Policlinico Umberto I, University of Rome “La Sapienza,” using a 64-slice CT scanner. Acquisition parameters included 20 × 0.625 detectors, a rotation time of 0.75 s, and pitch of 0.3, 760 mAs, and 140 kV. Reconstruction parameters were a thickness of 0.67 mm, increment of 0.335 mm, and kernel Y-Detail/Smooth. The CT data were analyzed by evaluating both individual cross-sections and the entire diaphysis to quantify structural and biomechanical properties. Diaphyseal plasticity in long bones reflects remodeling throughout life in response to mechanical loading [21], and cross-sectional geometry (CSG) provides insight into biomechanical performance. Key CSG parameters used in femoral biomechanical analysis include the polar moment of area (J), which indicates mean torsional and bending stiffness, and the second moments of area (Ix and Iy), which specify bending stiffness along particular axes. Relative cortical area (%CA) measures differential developmental and aging processes. The second moments of area (I) assess bending rigidity in a given plane, while the polar second moment of area (J) reflects resistance to torsion and overall rigidity. Measurements and CSG parameters in this study include anteroposterior (AP) and mediolateral (ML) widths (Supplementary Table S14), total subperiosteal cross-sectional area (TA, mm2), cortical area (CA, mm2), percent cortical area [%CA = (CA/TA) × 100], second moments of area [Ix (ML axis) and Iy (AP axis), mm4], minimum and maximum second moments of area (Imin and Imax, mm4), and the polar moment of area (J = Ix + Iy; see Supplementary Tables S15–S19). Although the femur is incomplete and does not allow for the direct estimation of torsion, torsional stiffness was assessed by analyzing Ix and Iy (Imax and Imin), as the torsional stiffness of a tubular bone depends on its polar moment of inertia. %CA was also evaluated, reflecting the size of the medullary cavity and responses to mechanical loading, such as the history of endosteal versus periosteal deposition and resorption, and age-related changes [22]. To analyze patterns of change in femoral diaphyseal transverse properties among Pleistocene “Homo”, the cross-sectional parameters TA, CA, Ix, Iy, Imax, Imin, and J, as well as the ratios %CA and Imax/Imin, were compared to other samples. These parameters were collected using MomentMacroJ v1.4B (available as freeware at https://fae.johnshopkins.edu/chris-ruff/; accessed on 11 February 2025) for ImageJ, on selected cross-sections at 20, 35, 50, 65, and 80% of the total femur length (Supplementary Tables S15–S19). Because the C7 femur has incomplete epiphyses, total length was approximated by comparison with scaled reference samples (Supplementary Figure S3). The 2D images were derived from the 3D model using Amira 6.

The metric data of the teeth, specifically the bucco-lingual (BL) and mesio-distal (MD) crown dimensions (Supplementary Table S10), were recorded following the protocol of Hillson et al. [23]. The morphological features of the teeth were assessed using the ASUDAS method of the Arizona State University Dental Anthropology System [24]. Micro-Computed Tomography images of the two lower molars (C11, LRM3 and C12, LLM3) were acquired using a ZEISS Xradia Versa 610 X-ray microscopy system (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) at the Research Center on Nanotechnologies Applied to Engineering (CNIS), Sapienza University of Rome (Italy). This instrument provides sub-micron-scale resolution images with enhanced contrast by combining geometric magnification and optical magnification with a high-flux X-ray source, thus overcoming the limitations of traditional X-ray Computed Tomography (CT). The Guattari Cave mandibles (C2 and C3) were scanned in November 2017 at the Core Facility for µCT Micro-Computed Tomography at the University of Vienna using a custom-built VISCOM X8060 (Germany) µCT scanner. Scan parameters were slightly adjusted for each specimen: 140 kV, 160–180 µA, 2200–2500 msec, diamond high-performance transmission target, 0.75 mm copper filter, and isometric voxel sizes between 10.6 and 12.7 µm. The µCT images were acquired from 1440 different angles. Using filtered back-projection in VISCOM XVR-CT 1.07 software, these data were reconstructed as 3D volumes with a color depth of 16,384 gray values and a resolution of 20 µm. The resulting slices display differences in X-ray attenuation, which are primarily due to differences in the density of the object studied [25]. Three-dimensional reconstruction and segmentation analysis were carried out using Visage Amira 6.3 software (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and using the latest available versione ov Bone J (1.4.3.0.) plugin for ImageJ 1.54 (NIH) [26]. The segmentation procedure was based on a semi-automatic threshold approach using the half-maximum height method (HMH) [27]. The 3D structures of the enamel, dentine, and coronal pulp cavity were obtained using the region of thresholding protocol (ROI-Tb) [28], which involves repeated measurements across different slices [29]. Virtual sections of each tooth were then extracted. The cementum–enamel junction (CEJ) was defined as the cervical line and determined manually, while the base of the pulp cavity chamber was established at the point where the interradicular canals begin. Variation in internal morphology and relative proportions of dental tissues were determined through digital analysis of linear, volumetric, and surface variables. We used the following abbreviations to identify the dental tissue volumes (mm3) [Supplementary Table S11]: Ve (enamel); Vcdp (coronal dentine and pulp chamber); Vpc, coronal pulp chamber volume; Vc (total crown = enamel, dentine, and pulp); Vcervix root cervix (pulp chamber ¼ situated inside the crown and root cervix); Vbranch root branch and Vt (total tooth = enamel, cementum, dentine, and pulp). In addition to the volumetric measurements, the linear and surface variables were identified SEDJ (EDJ surface, mm2).

Volumetric proportions of dental tissues are defined as:

- Vcdp/Vc% of coronal volume that is dentine and pulp (=100*Vcdp/Vc).

- Three-dimensional AET [3D average in mm of enamel thickness (=Ve/SEDJ)].

- Three-dimensional RET [scale-free, relative 3D thickness of enamel (=100*3D AET/Vcdp1/3) [30].

- VBI volumetric bifurcation (Supplementary Figure S4) index in % (=Vcervix/[Vcervix + Vbranch] × 100) [31]. Corresponding with the classification scheme of Keene [32] a value of 0–24.9% denotes a cynotaurodont molar, a value of 25–49.9% a hypotaurodont molar, a value 50–74.9% a mesotaurodont molar, and a value of 75–100% a hypertaurodont molar (Supplementary Table S12).To obtain the greatest amount of information on the sample, we evaluated the thickness of the lateral enamel excluding the occlusal one. In Amira (6.3.0, FEI Inc., Agawam MA, USA), we defined the plane of the occlusal basin, a plane parallel to the cervical plane and tangent to the lowest point of the occlusal basin enamel. Subsequently, all the material above the plane of the occlusal basin was removed and only the enamel, dentin, and pulp between these two planes were measured [33]. In the text and figures, we use the following abbreviations to identify the dental tissue volumes (mm3):

- ○

- LVe (lateral enamel volume).

- ○

- LVcdp (lateral volume of coronal dentin including pulp enclosed in the crown).

- ○

- LVpc (lateral coronal pulp chamber volume).

- ○

- LVc (total lateral volume of the crown, including lateral enamel, dentin, and pulp).

- ○

- LSEDJ, in mm2 (lateral surface of the EDJ).

- ○

- (LVcdp/LVc = 100*LVcdp/LVc in%). Percentage of dentin and pulp in the volume of the lateral crown

- ○

- Three-dimensional average enamel thickness (3D LAET = LVe/LSEDJ in mm).

- ○

- Three-dimensional relative lateral enamel thickness [3D LRET = 100*3D LAET/(LVcdp1/3)], a measurement without scale.

The accuracy of the microtomographic-based measurements was tested for intra- and inter-observer error using three different individuals; differences were <3%.

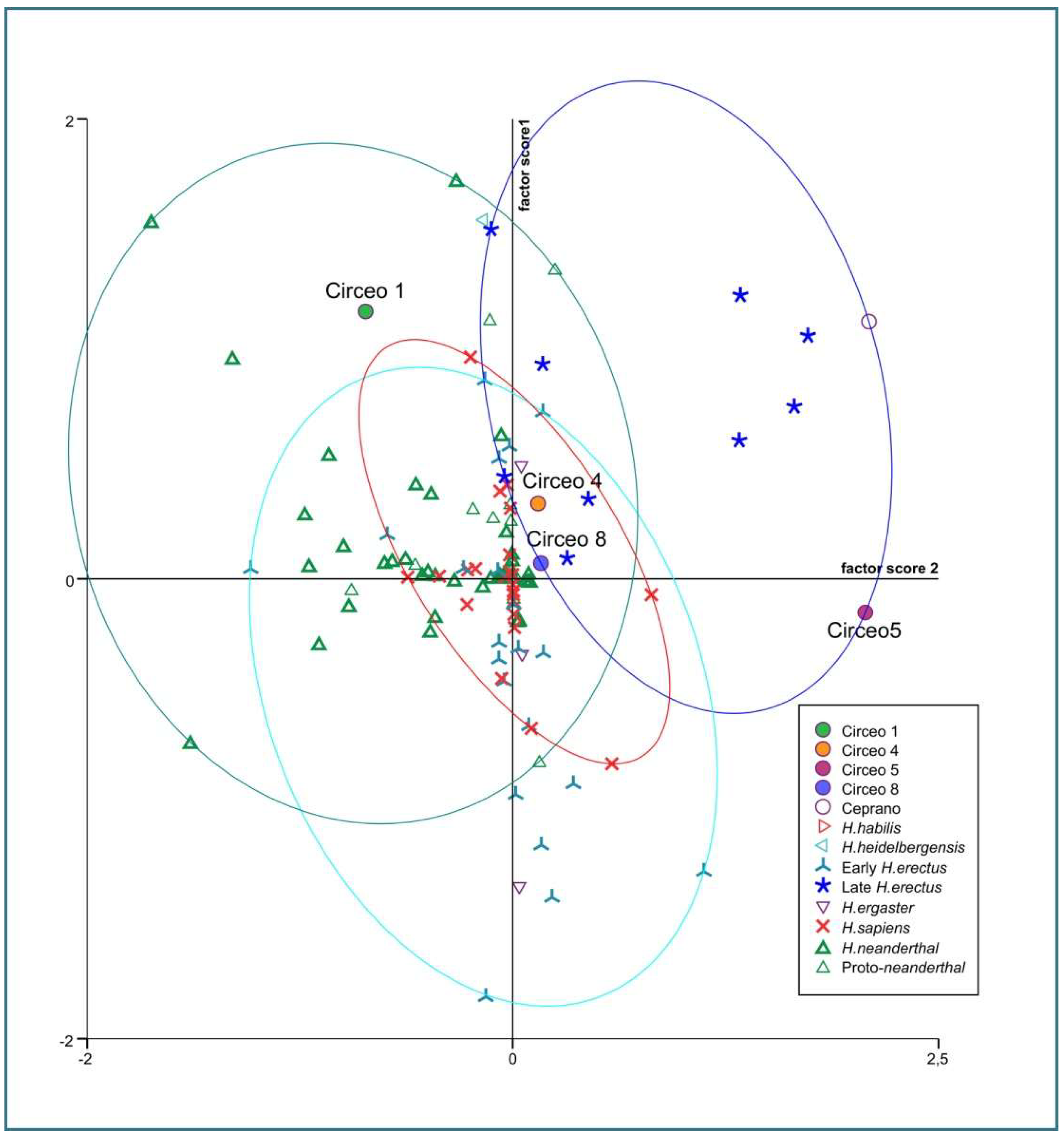

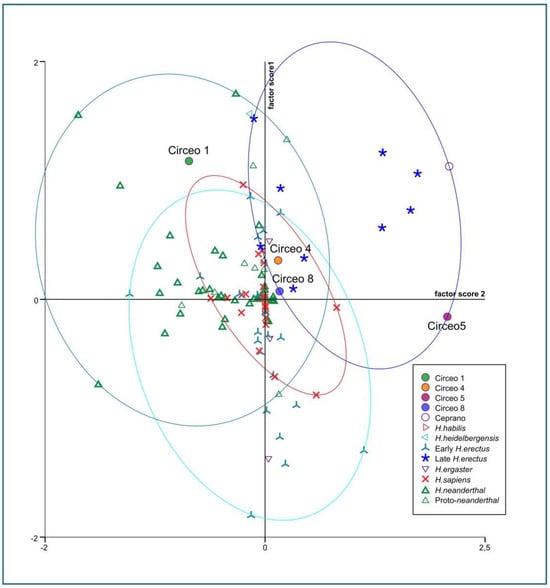

Internal anatomy was analyzed using bucco-lingual (b/L) sections across the two dentine and pulpal horn tips of the mesial cusps of the crown, as well as along the enamel junction. This approach allowed us to obtain both perpendicular and horizontal views of each root canal. To visualize the topographical distribution of enamel thickness, particularly in the C2 and C3 samples where wear was present, we imported the meshes obtained from CT scan segmentations into MeshLab. In MeshLab, we applied the Shape Diameter Function (SDF) filter, which estimates the local diameter of the object at each point on the mesh surface by sending several rays inside a cone centered around the point’s inward-normal. This process provides a measure of the neighborhood diameter at each point [34]. We then used the Colorize by Vertex Quality filter to generate a topographic map of thickness, with increasing thickness represented by a chromatic scale from dark blue to red. To establish the phyletic relationships within this sample, we conducted both qualitative analyses, exploring morphological variations and affinities, and quantitative multivariate analyses. The latter involved comparing our data with synchronic and diachronic datasets available for African, European, and Asian Homo (with particular attention to the south-eastern area), as well as modern humans. For the complete sample, we performed a multivariate non-parametric analysis using principal components analysis (PCA) on 23 raw variables. PCA was calculated on the correlation matrix to standardize variation, and all statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0. In order to maximize the number of samples for inclusion in PCA, we used the following variables: maximum cranial length (g-op, M1), maximum cranial breadth (eu-eu, M8), minimum frontal breadth (ft-ft, M9), maximum frontal breadth (co-co, M10), supraorbital torus breadth, height (Po-Br, M20), bi-frontomalare temporale breadth (fmt-fmt, M43), postorbital breadth, biasterion breadth (ast-ast, M12), lambda-inion (M31), lambda-asterion (M30,3), inion-asterion and thickness at lambda, inion, internal occipital protuberance, asterion, bregma, supraorbital torus thickness at midorbit (SOTTM), torus highest point, parietal to bregma, parietal to lambda, parietal eminence, and parietal to the asterion. Finally, we carried out an overall analysis using both coefficients of variation and description of non-metric traits in a data-combined approach within Middle and Late Pleistocene Eurasian groups.

Dummy variables, defined as traits that are always present or always absent among all cases, were excluded from the analysis [35]. The distance between two samples (dij) was calculated by dividing the number of variables present in one individual and absent in the other (scored as 10 or 01) by the total number of variables, including those present or absent in both individuals (scored as 11 or 00) [36]. The binary scores and formulas were compiled in a spreadsheet to generate a matrix, which was then used for Cluster Analysis employing the WPGMA method and squared Euclidean interval. Paleogenomic analyses of the entire dental sample and petrous bone were conducted in Leipzig and Vienna. However, due to strong diagenesis resulting in a scarcity of collagen, it was not possible to extract aDNA. In the absence of paleogenomic results, phenotypic variation was assessed by combining mixed, metric, and non-metric traits, together with an analysis of available genetic data in the literature. For the interpretation of possible gene flows and migratory scenarios, we relied on published data, particularly the results of Posth et al. [37] and Hajdinjak et al. [38]. Where available, genetic information on the percentage of Neanderthal ancestry has been discussed in the following Section 5.2. The morphological traits analyzed in this study are considered derived features of Neanderthals or H. erectus and were used for taxonomic identification.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Morphology

Cranium

Circeo 4 (C4)

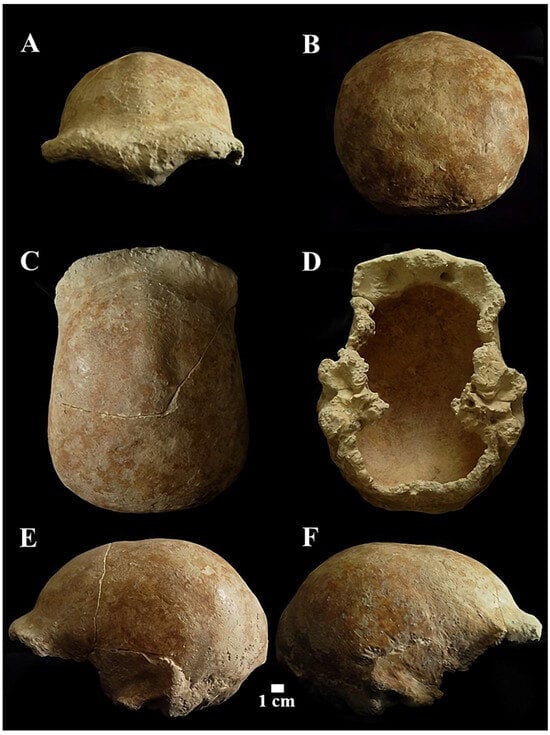

Cranial remains found inside the cave, “Antro del Laghetto” area (Figure 4, localization) [Figure 10 and Supplementary Figure S5A].

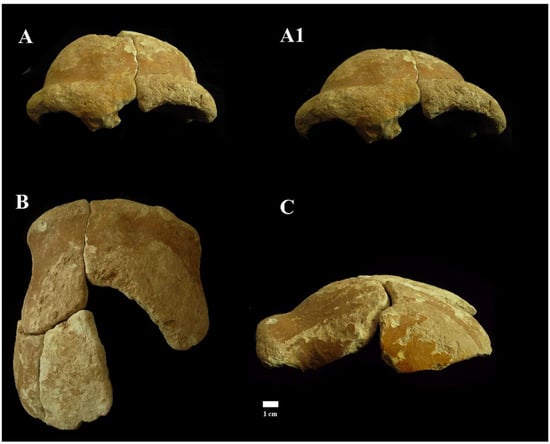

Figure 10.

Circeo 4, frontal bone. View: Frontal, anterior–superior (A) and anterior (A1); superior (B); and left lateral (C).

A portion of calvarium is composed of four elements constituting a large part of the frontal bone and a small part of the left parietal bone. The frontal bone consists of a right and a left squama frontalis. There is mild asymmetric retro-orbital narrowing. The supraorbital torus is thick, and the prominent glabella is in line with the nasion. The orbits are rounded (Supplementary Catalog of Specimens).

Despite the strong extracranial cortical erosion, a short section of coronal suture on the left frontal squama remains preserved (Supplementary Figure S6), a relevant data not only from a metric point of view but also from a diagnostic point of view as it allows us to formulate an approximate age diagnosis. The individual, therefore, according to modern parameters [20], could be an adult, but not too young, considering the persistence of sutural denticles.

Circeo 5 (C5)

Calvarium found inside the cave, “Antro del Laghetto” (Figure 4, localization) [Figure 11 and Supplementary Figure S5B,B1].

Figure 11.

Circeo 5 calvarium. View: A, frontal anterior; B, posterior (occipital); C, superior; D, inferior (basicranium); E, right lateral; F, Left lateral.

The neurocranium (Calvarium) is moderately elongated in the anteroposterior direction and semi-rounded in the occipital region. In posterior view, the parietals are quite vertical with a curvature starting in the upper third (Figure 11B). The lateral cranial walls are, therefore, parallel to the superior parietal bones which are short, flat, and slightly convergent. The lateral cranial walls are, therefore, parallel to the superior parietal bones which are short, flat and slightly convergent. The orbits are rounded (Supplementary Catalog of Specimens). The morphological traits and the synostosis of the cranial sutures are consistent with those of an adult female individual.

The squama frontalis has a distinct post-toral plane and a high, rounded frontal. The supratoral sulcus is continuous and the supraorbital torus is thick. The glabella is in line with the nasion. There is a slight supraorbital narrowing and residual traces of the lower part of the metopic suture. It has a frontal keel that extends along much of the sagittal line. It is defined by a pair of long, mediolaterally wide anteroposterior depressions in the frontal “squama” [39,40] (Figure 12). It presents a well-developed bregmatic eminence, associated with two pre-bregmatic parasagittal depressions that do not involve the parietal bone (Figure 12). The bregmatic eminence is not separated from the frontal keel. The small temporal bone (squama temporalis) shows a linear upper profile (Supplementary Catalog of Specimens). The juxtamastoid eminence is incomplete and eroded, and both the juxtamastoid and occipitomastoid crests appear to be absent. The mastoid processes are small with underdeveloped apophysis and incomplete apex.

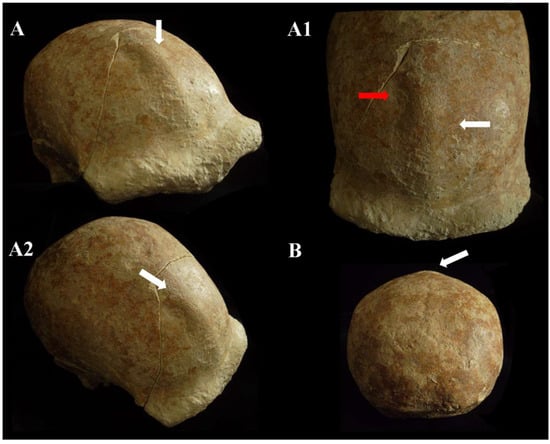

Figure 12.

Circeo 5, frontal keel. View: superior–anterior (A,A1), superior–lateral (A2), and posterior (B). The white arrows indicate the frontal keel. The frontal keel is defined by a pair of anteroposteriorly long and mediolaterally wide depressions in the frontal squama (the red arrow in A1 indicates an accentuation of depression). Not to scale.

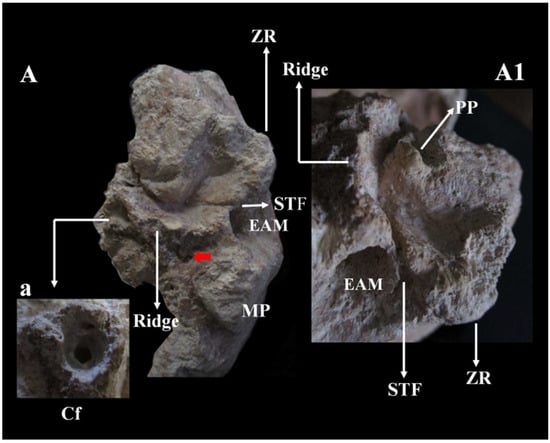

Basicranium (Comprehensive Supplementary Catalog of Specimens).

In the basicranium (Figure 13 and Supplementary Figure S7), the mandibular fossa, bilaterally, is preserved and deep. It has a squamotympanic fissure (STF) that runs into the roof of the fossa itself and a coronally oriented tympanic plate [41]. The styloid process is not fused to the skull base, and the vaginal process is absent. The carotid foramen, visible only on the right, is posterior to the STF and shows a thickening of the opening margin and a narrowing of the channel (Figure 13a). The styloid process is not fused to the skull base, and the vaginal process is absent. The postglenoid process is absent. The sigmoid sinuses are vertical, and near the left sigmoid sinus, there is a distinct sulcus (Supplementary Figure S8).

Figure 13.

Circeo 5, basicranium. Temporal bone left mandibular fossa (TMJ) viewed in norma basalis. A, styloid foramen (red arrow). Ridge (process supratubalis?), wrinkled crest that extends to the External Acoustic Meatus (EAM). Absence of the vaginal process and the styloid process. Squamotympanic fissure (STF). a, Detail of the Carotid foramen (Cf) with bony thickening of the marginal rim of the foramen and narrowing of the carotid canal. A1 detail of A. Note the absence of the postglenoid process, the position of the squamotympanic fissure (STF) that runs into the roof of the fossa itself, and the coronally oriented tympanic plate. MP, Mastoid Process; ZR, Zygomatic Root; PP, Preglenoid (entoglenoid) Process (?). Not to scale.

The occipital bone shows ectocranial thickening on the superior nuchal line (underdeveloped nuchal torus). The transverse torus occipitalis expands laterally in the direction of the asterion, most noticeably on the right side. Between the superior and supreme nuchal line, there is a small and smooth suprainiac fossa, circular in shape. The inion is located well above the endinion. The posterior projection of the squama occipitalis (chignon) is slight. Sutural synostosis is characterized by interdigitations on the outer table and incomplete obliteration on the inner table.

Overall, individual C5 is a young adult female [20] who presents with mild internal frontal hyperostosis.

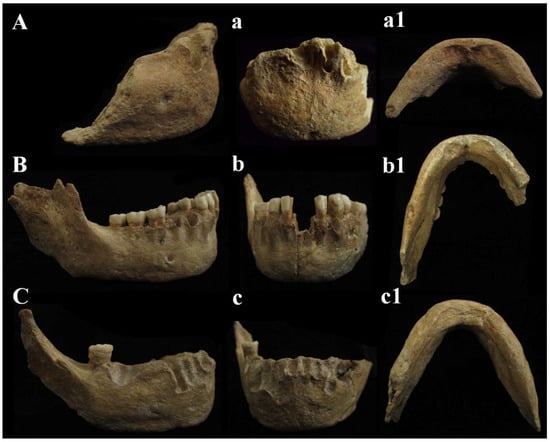

Circeo 6 (C6)

Mandible found inside the cave, “Antro del Laghetto” area (Figure 4 and Figure 6, localization) [Figure 14A,a,a1].

Figure 14.

Circeo mandibles, comparison. Circeo 6 (A), mandibular symphysis recent discovery, Circeo 2 (C) and Circeo 3 (B), original specimens, respectively, from 1939 and 1950. Circeo 6, view: (A) lateral (right); (a) anterior; (a1) inferior. Circeo 3, view: (B) lateral (right); (b) anterior; (b1) inferior. Circeo 2, view: (C) lateral (right); (c) anterior; (c1) inferior. Not to scale.

C6 is an anterior interforaminal portion (synphysis). The mandibular symphysis is characterized by the absence of mental trigone. It shows a slight hint of the chin eminence (mentum) with incurvatio mandibulae in lateral view, which may be accentuated by the presence of bone atrophy due to intra-vitam tooth loss. The digastric fossa is directed downwards and posteriorly. C6 has on the right side (the left side is incomplete) a single oval mandibular foramen, horizontal and parallel to the masticatory plane and located under M1 (P4) [Supplementary Catalog of Specimens].

In C6, severely atrophied alveolar areas show residual alveolar ridge morphology consistent with tooth loss before death (Supplementary Table S13). The alveolar ridge of the central incisors does not present horizontal atrophy [42,43], and the bone level is normal [44]. The presence of a thin fracture line involving only the external alveolar bone is noted in correspondence with the right central and lateral incisors [Supplementary Catalog of Specimens].

Circeo 8 (C8)

Occipital bone (squama occipitalis) found inside the cave, “Antro del Laghetto” area, composed of a portion plus one fragment (Figure 4, localization) [Supplementary Figure S9; Supplementary Catalog of Specimens].

The occipital plane is convex. The nuchal plane is incomplete. An occipital bun is absent. The “nuchal torus”, heavily eroded, shows ectocranial thickening located above the superior nuchal line. The suprainic fossa is elliptical and is located on the upper margin of this thickening. Its surface is pocked [45]. The inion is located immediately above the endinion. The torus has no margins but upper and lower thinning. The transverse torus is thickened medially and lacks significant lateral development. External occipital protuberance is absent. The interdigitations of the lambdoid suture, without traces of synostosis [20], and the pocked surface of the suprainiac fossa indicate that this occipital bone could belong to a young individual and is therefore not compatible with C4.

Circeo 9 (C9)

Palatine process of maxilla found inside the cave, “Antro del Laghetto” area (Figure 4, localization) [Supplementary Figure S10].

Although the finding shows severe erosive aggression, the presence of a progressive alveolar ridge atrophy due to tooth absence is evident. The sinuses sit above the upper teeth. The maxilla in the palatal view (palatine) presents slight traces of palatine torus along the margins of the medial palatine suture. There is asymmetrical thickness between the right and left sides of the palate. Residual dental alveoli are present on the right while the left anterior alveolar ridge shows bone remodeling. The nasal view shows a large piriform opening. Based on the features of the internal nasal region presented by Schwartz et al. [46], we provide a description, in Supplementary Catalog of Specimens, of the topographic relief of the nasal cavity wall of C9, which preserves part of the nasal fossae with the spinal crests and nasal ridges (Supplementary Figure S10).

Dental sample

Circeo 10a and b (C10a-C10b) found in the area outside the cave (Figure 2, localization).

Permanent maxillary molars and alveolar part (Supplementary Figure S11).

Second and third right upper molars (M2 and M3), contiguous and compatible. Both are probably from the same adult individual. A small portion of alveolar bone is present (M2 in alveolar bone). The estimated age for tooth wear is adult. Dental traits: M2 right: presence of grade 3.5 metaconus and hypocone, absence of 5th cusp, Carabelli tubercle and parastyle, and presence of grade 2 enamel extension and three roots; M3 right: absence of 5th cusp.

Circeo 11 (C11) found inside the cave, “Antro del Laghetto” area (Figure 4, localization).

Permanent lower molar (Supplementary Figure S12).

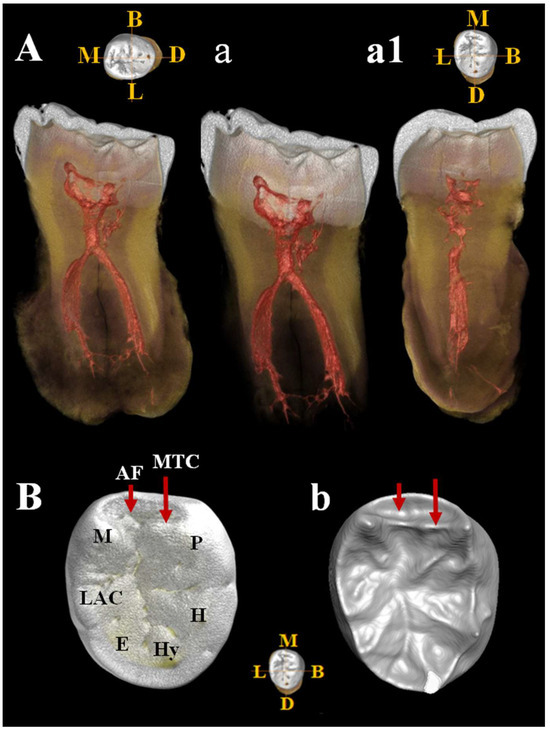

C11 is a probable lower right third molar (M3) because the contact facet on the distal side is missing. Estimated age for tooth wear: young adult. Dental traits: presence of mid-trigonid ridge (grade 1A) and fovea anterior, sulci pattern = +, presence of 5 cusps, absence of 6th cusp and presence of a probable lingual accessory cusp (Figure 15B,b). C11 shows a club-shaped diffuse apposition of cementum that cover a large part of the tooth root, giving it a “bulbous” appearance (hypercementosis). It involves the apical and middle root third and root furcation areas. The roots are fused but retain a thin line of demarcation. µCT images (Figure 15) show a thickened root highlighted by a radiopaque area consistent with the presence of hypercementosis (Figure 15A–a1). A thin and partial separation between the roots is visible, associated with the presence of numerous lateral and accessory canals, as well as apical deltas (Figure 15A–a1). There is a connection between the two main canals in the apical third (Figure 15a) and the respective apical foramina with regular direction are present, documenting a probable tooth vitality. A loss of contour of the tooth roots is visible due to fusion with the calcified mass, a morphology that could mimic a cementoblastoma. Moderate taurodontism is present with an index corresponding to mesotaurodontism (Supplementary Table S12).

Figure 15.

µCT images of Circeo 11 lower right third molar (LRM3) with club-shaped hypercementosis. Dentinal structures of the root: A, view of the mesio-distal section with hypercementosis; a, view of the mesio-distal section without hypercementosis, digitally removed; a1, view of the bucco-lingual section. Note the presence of a connection between the two main canals in the apical third and the presence numerous lateral accessory canals and apical deltas. The apical foramina have a regular direction. b, Occlusal view of the crown surface (enamel) illustrating the main cusps and one probable accessory cusp; B, occlusal view of the enamel–dentin junction (EDJ) [enamel digitally removed], showing the presence of the mid-trigonid crest (MTC) and the anterior fovea (AF). Abbreviations: B, Buccal; L, Lingual; M, Mesial; D, Distal; P, Protoconid; H, Hypoconid; Hy, Hypoconulid; E, Entoconid; LAC, Lingual Accessory Cusp; M, Metaconid.

Circeo 12 (C12) found inside the cave, “Antro del Laghetto” area (Figure 4, localization).

Permanent lower molar (Supplementary Figure S12).

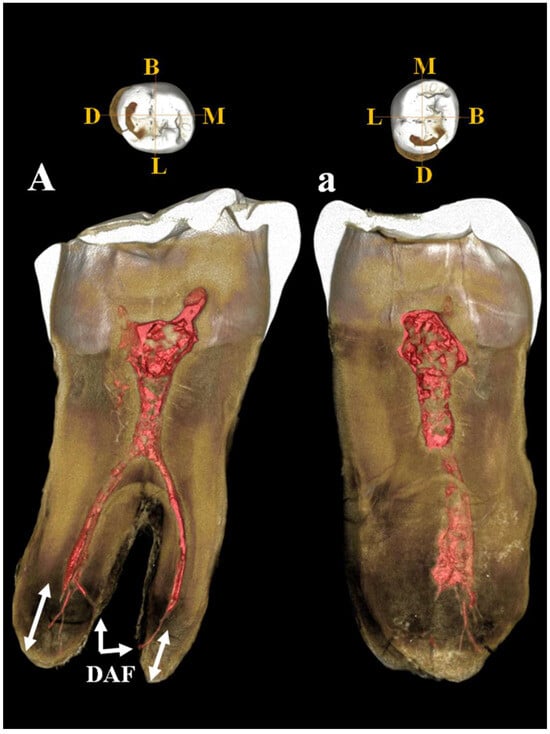

Left lower third molar (3M). Estimated age for tooth wear: adult. Dental traits: sulci model = (+), presence of n. 4 cusps, presence of mid-trigonid ridge (grade 1A) and fovea anterior, absence of protostilis, 5th, 6th, 7th cusps and extension of enamel, presence of two roots. The µCT image (Figure 16) shows the periapical apices of both roots with a slight apposition of cementum that has caused a deviation of the canal and apical foramen in the mesial root and an apical rounding with the formation of an accessory lateral canal in the distal root (Figure 16A,a). The presence of residual apical deltas is noted in both roots. As in C11, moderate taurodontism is present with an index corresponding to mesotaurodontism (Supplementary Table S12).

Figure 16.

µCT images of Circeo 12 lower left third molar (LLM3). Dentinal structures of the root: A, view of the mesio-distal section; a, view of the bucco-lingual section. Mesio-distal section shows the periapical apices of both roots with cementum apposition (double white arrows), deviation of the canal and of apical foramen in the mesial root, and presence of an accessory lateral canal in the distal root. Note the presence of residual apical deltas in both roots. Abbreviations: DAF, deviated apical foramen; B, Buccal (vestibular); L, Lingual; M, Mesial; D, Distal.

Circeo 13 (C13) found inside the cave, “Antro del Laghetto” area (Figure 4, localization). Permanent upper canine (Supplementary Figure S11).

Right upper canine (C1). Estimated age for tooth wear: young adult. Dental traits: probable absence of shovel absence of tubercle in the cingle, extension of enamel, presence of root. Slight apical hypercementosis.

Circeo 14 (C14) found inside the cave, “Antro del Laghetto” area (Figure 4, localization) [Supplementary Figure S11].

Permanent upper second premolar tooth (Supplementary Figure S11).

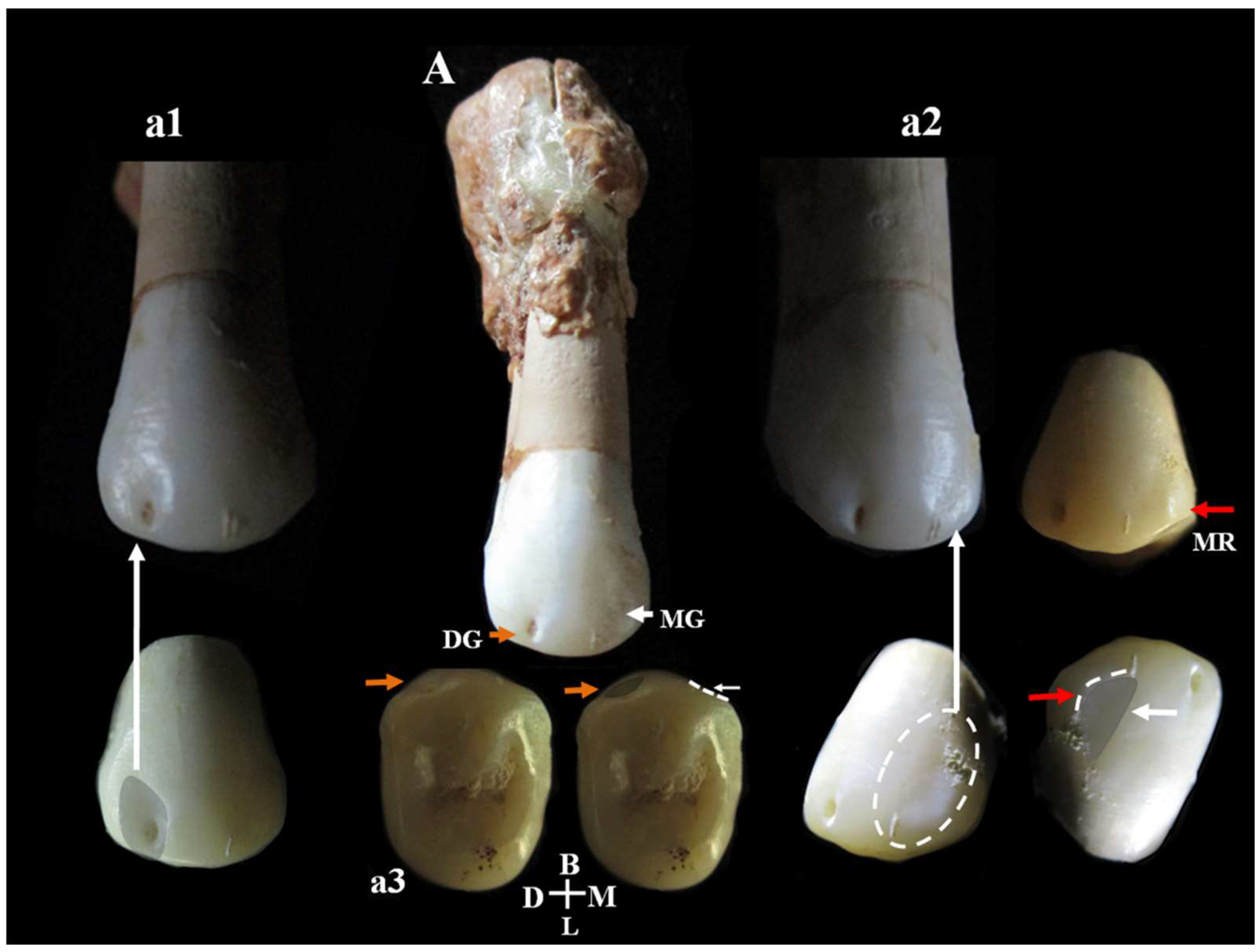

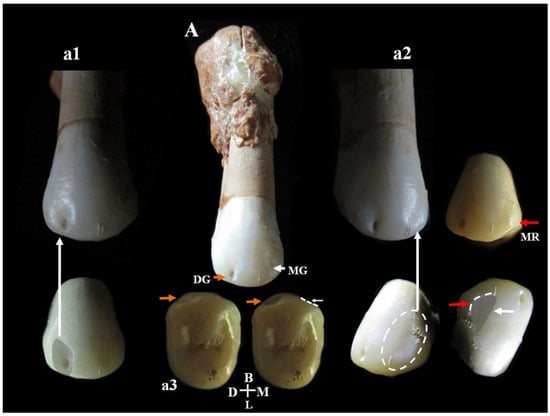

C14 is a right upper second premolar (P4) showing a club-shaped diffuse apposition of cementum that covers a large part of the tooth root (hypercementosis). Estimated age for tooth wear: young adult. Dental traits: presence of two lingual cusps, enamel extension. On the buccal surface of the crown, there is a plesiomorphic character from the Middle and Upper Pleistocene consisting of a buccal vertical groove. The vertical groove is present on the distal aspect of the vestibular surface and is associated with a clear concavity. A weak and indistinct concavity is also present on the mesial aspect associated with a small vertical ridge (Figure 17). The buccal vertical groove is visible on 3D reconstruction of the outer-enamel surface (vestibular) and on the enamel–dentine junction (Supplementary Figure S13).

Figure 17.

Mesio-distal buccal vertical groove of the second upper premolar, Circeo 14. A, Complete vestibular side of Circeo 14. The orange arrow highlights the distal buccal vertical groove on the crown surface (detail in a1), and the white arrow the mesial groove (detail in a2). a3 is the occlusal view of both grooves. Note the severe hypercementosis involving the apical third of the root. The buccal groove, an archaic character from the Middle and Upper Pleistocene, is a shallow vertical groove accompanying a ridge on the mesial and distal margins of the vestibular surface. In our sample, a distal groove associated with a clear concavity was observed while on the mesial side, there is a weak and indistinct concavity associated with a small vertical ridge (MR, red arrow). DG, Distal Groove; MG, Mesial Groove; MR, Mesial Ridge; D, Distal; M, Mesial; B, Buccal (vestibular); L, Lingual. Not to scale.

Circeo 15 (C15) found inside the cave, “Antro del Laghetto” area (Figure 4, localization) [Supplementary Figure S14].

Crown and root part of a permanent tooth (Supplementary Figure S14).

Part of the crown and root of a small permanent upper right first molar (M1). The crown, although incomplete, shows a mesiodistally compressed morphology and the roots, which are also incomplete, are small and strongly splayed. Distal contact facet is present. Severe wear. Dental traits: grade (1) enamel extension.

Postcranial skeleton

Circeo 7 (C7)

Right femur (diaphysis) found inside the cave, “Antro del Laghetto area” (Figure 4, localization) [Supplementary Figure S15].

C7 is without both epiphyses. Femoral shaft is curved, platymeric in the subtrochanteric part and with weak midshaft pilastric index. The linea aspera is continuous, modest, and with a pilaster consisting of a light underlying bony crest (Supplementary Figure S16). The cortical distribution pattern of C7 for the 80%, 65%, and 50% cross-sections shows a constant maximum cortical thickness on the medial side and is variable from lateral to lateroposterior on the lateral side (Supplementary Figure S3). Supplementary Tables S4 to S8 show the diaphyseal cross-sectional properties of the proximal, distal, and mid-diaphyseal sections of C7 and the comparative specimens.

Circeo 16 a (C16a)

Incomplete left coxal bone found inside the cave, “Antro del Laghetto” area (Figure 4, localization) [Supplementary Figure S17].

The partial iliac bone preserves the incomplete iliac wing, a small portion of the auricular surface, a remnant of the tubercle of the iliac crest, a small, preserved margin of the anterior superior iliac spine and the anterior inferior iliac spine. Finally, a portion of the acetabulum is preserved (fossa), with exposure of the spongy bone on the acetabular rim, and a portion of the greater sciatic notch. The ischium and pubis are completely missing. In the lateral view, the presence of a single ventral iliac buttress acetabulocrystal (vertical) is noted. The thickness of the buttress is variable. In medial view, there is a well-defined arcuate line and a thick iliosciatic buttress (Comprehensive Supplementary Catalog of Specimens). The composite morphology of the arch, formed by the sciatic notch and the auricular surface, is consistent with the female morphology.

Circeo 16 b (C16b)

Incomplete right coxal bone found inside the cave, “Antro del Laghetto” area (Figure 4, localization) [Supplementary Figure S18].

The partial iliac bone preserves the incomplete iliac wing, a portion of the auricular surface, a small remnant of the iliac crest (tubercle iliac crest?), a small preserved margin of the anterior inferior iliac spine, the latter accentuated by an evident supra-acetabular sulcus which extends between the acetabulospinal buttress and the acetabular rim, a portion of the acetabular fossa with exposure of the spongy bone on the acetabular rim, and finally a portion of the greater sciatic notch. The ischium and pubis are completely missing. In the lateral view, a single ventral iliac acetabulospinal buttress is present (concretions are present). The thickness of the buttress is variable. There is a thick iliosciatic buttress (Comprehensive Supplementary Catalog of Specimens). The composite morphology of the arch, formed by the sciatic notch and the auricular surface, is consistent with the female morphology.

4.2. Comparative Morphology and Discussion of Morphometric Data

The first variant emerges from the direct comparison between the remains of 1939–1950 (C1, C2, and C3), classic Neanderthals, and the recent remains (C4, C5, C8, and C6), which are characterized by a mixture of autapomorphic and plesiomorphic traits shared with the monophyletic group (Proto-Neanderthal and classical European Neanderthal, Erectus s.s. and s.l., and Sapiens). A similar pattern of variability is observed in the dental sample.

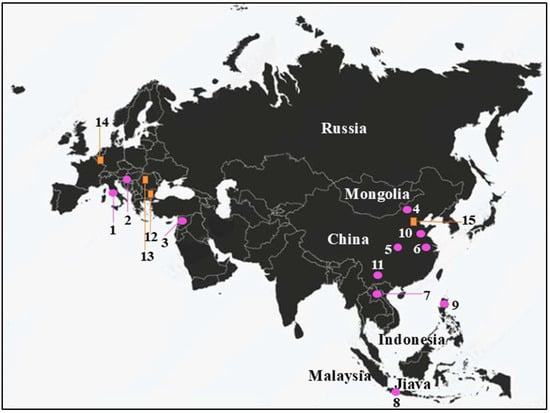

Frontal bone C4 and C5. Both present a similar morphology and a notable thickness (Supplementary Figure S19). The morphology and total frontal bone thickness (measured as the combined thickness of the diploe and the inner and outer tables) differ from those observed in C1. This difference may reflect variability within the species rather than differences at the genus level. In anterior view, the supraorbital torus of C4 and C5 exhibits a morphology similar to that seen in Asian H. erectus (e.g., Zhoukoudian 12 and 5), Late European Erectus such as Lazaret 24 (170 ka), and European Proto-Neanderthals like Biache-Saint-Vaast 2 (BSV2) and Petralona. The supraorbital torus is wide and continuous, and when viewed from above (norma verticalis), there is no glabellar depression present. The supratoral sulcus is defined and continuous in C5 but discontinuous in C4, where it is interrupted by a convexity in correspondence with the glabella as in the Late Indonesian Erectus Ngadong 5 [47]. In C4, this convexity may be caused or accentuated by the morphology of the frontal sinus. The frontal sinuses of C4 are asymmetric, well developed, and contain multiple chambers (Comprehensive Supplementary Catalog of Specimens). The minimum frontal diameter of C4 and C5 is greater than that of BSV2 and Neanderthals, but is very similar to C1, slightly lower than Amud 1, and comparable to Ngadong 11 and WLH 50 (Australian “H. sapiens”) [Supplementary Table S3]. C4 and C5 show a postorbital narrowing and a widening towards the parietal walls, but this widening is less pronounced than in classical Neanderthals. The sagittal profile of the frontal bone in C4 and C5 differs from that of classic Neanderthals such as C1, La Chapelle-aux-Saints, and La Ferrassie 1, which display a more anteriorly positioned glabella relative to the nasion. In lateral view (norma lateralis), the upper profile of C5 is high and rounded, similar to the Indonesian fossils (Sangiran [S], Sambungmacan [SM], and Ngandong). It displays a convex frontal contour, which is absent in C4, and this convexity becomes more pronounced at the bregmatic eminence. The distance from the glabella to the bregma along the mid-sagittal plane is greater in C4 than in C5, but both measurements fall within the range observed in Javanese specimens (Supplementary Table S3).

C5 calvarium. It displays a combination of Proto-Neanderthal plesiomorphic traits (such as the absence of the anterior mastoid tubercle) and Neanderthal autapomorphic traits (such as the digastric sulcus closed anteriorly) [Supplementary Table S2]. Some of these characteristics are also known in H. erectus s.s. Additionally, the morphology of the parietals—vertical with a curvature beginning in the upper third—is very similar to that of the archaic Middle Eastern H. sapiens specimen Manot 1 (Israel). Unlike the C1 skull, and presumably also C4, the frontal bone of C5 exhibits a frontal “keel” (Figure 12), a feature described by Schwartz et al. [40] as unique to Trinil 2 (an autapomorphy) and also present in Sangiran specimens. The frontal keel of C5, like that of Trinil 2, is characterized by a pair of anteroposteriorly long and mediolaterally wide depressions in the frontal squama [39,40] (Figure 12). C5, like the Indonesian specimens, also has a bregmatic eminence that does not extend bilaterally into the coronal keels or posteriorly into a sagittal keel, but it does possess a pair of small depressions located posterior to the bregma [39,40]. Contrary to the Ngandong specimens [48], the bregmatic eminence of C5 is not separated from the frontal keel. In all Proto-Neanderthal samples from Atapuerca Sima de los Huesos (SH), a mid-sagittal keel on the squama frontalis has been described [49]. However, the authors note that this feature does not exactly match the morphology and autapomorphic characteristics of the Asian H. erectus holotype Trinil 2, and they suggest that this trait is absent in Neanderthals [49]. The supraorbital torus of C5 appears more similar to that of Lazaret 24 [50] and BSV2 [48,51]. The latter has been classified as type III in the Cunningham classification system [51] and is considered similar to those of Sima de los Huesos 5, Bilzingsleben, and the Neanderthals [51]. The sagittal profile of the C5 calvarium also shows a similar contour to S2, SM1, and Ngandong.

In posterior view, the parieto-temporal curve in the coronal plane closely resembles the “tent” morphology of the Indonesian sample SM 4, a result of the presence of the bregmatic eminence (Figure 11B). However, the vertical lateral profile is very similar to that of the Western Asian (Israel) H. sapiens Manot1 (55 ka [52]) and differs from the rounded profile characteristic of classic Neanderthals such as C1, La Chapelle-aux-Saints, and Ferrassie1. In C5, as in Manot1 and modern humans, the maximum cranial width is positioned high, and the lateral walls are vertical and almost parallel [52]. The biasterionic breadth of C5 is larger than that of Manot 1, which is extremely small, but is similar to that of Shanidar 1, Sale (Erectus, Morocco), and Xuchang (XUC2) and falls within the range observed in the Java specimens (Supplementary Table S4). The convexity (bunning) of the occipital bone of C5 and C8 is less pronounced than in C1 (although it is more defined in C8 than in C5), Manot 1, Chapelle-aux-Saints, and Middle Pleistocene fossils from northern Africa (Jebel Irhoud, Morocco) and Europe (Neanderthals). According to Hershkovitz et al. [52], the presence of bunning is not necessarily related to interbreeding between Neanderthals and modern humans, as it is not present in Middle Eastern Neanderthals (e.g., Amud 1). Therefore, the authors suggest that this morphological trait originated in modern Near Eastern humans, or possibly even earlier in some African populations such as Aduma (~79–105 ka), who later migrated to the Levant. Furthermore, in C5, we observed a slight parietal flattening that extends into the lambdoid region. In Manot 1, as in BSV1, some features typically associated with classical Neanderthals, but occasionally present in other fossils, have been described. These include lambdoid flattening of the parietal bones associated with the occipital conformation, resulting in a double arched-shape profile with parietal and occipital concavities. This medial change in the posterior parietal curve, identified as a prelambdic depression, indicates the presence of an occipital bun, a trait described for C1, La Chapelle-aux-Saints, Spy 2, and La Ferrassie 1. In the post-obelic region of C5, there is a slight inflection followed by an occipital protuberance, which does not correspond to the classic bun. Therefore, we believe that in C5, the slight parieto-lambdoid flattening, in the absence of a classic Neanderthal occipital chignon, does not produce the double arch parietal and occipital profile described for Manot 1 and BSV1, but rather resembles a characteristic of the Ngadong specimens, as described by Zhang (Doctoral dissertation) [53], corresponding to a depression in the posterior parietal region that ends at the lambda. The occipital profile described by Schwartz [40] for S2 and SM1 as “rounded between the anteriorly inclined occipital and nuchal planes which gives the short occipital supero-inferiorly a blunt V-shaped profile”, shows similarities with C5, particularly when compared with SM1. In C5, Ngawi 1 and S3, the morphology of the occipital torus is similar to that of the Ngandong specimens, but less prominent [40].

Temporal bone C5. Moreover, regarding the temporal bone, the presence/absence of a mosaic of very specific traits (autapomorphic and plesiomorphic) relating to H. erectus s.s., H. erectus s.l. (Late Indonesian), and Neanderthal have been detected. H. erectus is usually described as having “well-developed or marked” mastoid and supramastoid crests, which are separated by a supramastoid groove or, in some cases, fused [53]. In C5, these crests appear to be present, separated by a slight supramastoid sulcus, and show a generalized hypertrophy of the temporal bone, but without the presence of an angular torus. The tympanomastoid fissure, which separates the tympanic plate from the mastoid process, is absent on the right but may be present on the left. On the left side, a slight line of separation between the tympanic plate and the mastoid process is visible, though it is interrupted by a small area of post-mortem damage. This trait is considered an autapomorphy of Asian H. erectus [54]. The mandibular fossa of C5 (Figure 13), which is bilaterally preserved (Supplementary Figure S7), exhibits a morphology very similar to that of the Ngandong specimens [41,55]. It features a coronally oriented tympanic plate (a plesiomorphic trait) [41] and the STF runs in the roof of the fossa, with the posterior wall of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) formed exclusively by the tympanic plate. In C1, the tympanic plate is oriented coronally, but the STF is located posterior to the apex of the fossa. The tympanic plate is generally considered to be oriented coronally in H. erectus and sagittally in modern humans. The orientation in Neanderthals is debated: Weidenreich [56] and Stringer [54,57] argue for sagittal orientation, while other authors [58,59] suggest it is coronally orientated. In C5, the styloid process is absent (that is, it is not fused to the skull base) and the postglenoid process is also absent, as observed in the Ngandong specimen (Supplementary Table S2). The styloid process is fused to the petrous bone in all SH specimens and in Neanderthals as C1 (except some specimens from Krapina and Shanidar1; Supplementary Table S2) [41]. In Asian H. erectus, the postglenoid process is significantly reduced (apomorphy) [41] and the styloid process is absent (apomorphy) [41]. A well-developed postglenoid process is a feature of the Proto-Neanderthal SH sample, abd is present in BSV2 [51] and in classical Neanderthals (including C1 skull). The European Middle Pleistocene fossils, Castel di Guido and Ceprano, also show a well-developed postglenoid process [41]. In Middle Pleistocene Asian fossils, both conditions are present (Narmada, Dali, and Xujiyao show the styloid process although Hexian and Yunxian 2 lack it [41]). In C5, the digastric sulcus and the stylomastoid foramen are not aligned. Similarly in BSV2 and in classical Neanderthals, the digastric sulcus, the base of the styloid process and the styloid foramen are not aligned, as the styloid process is positioned more medially relative to the digastric sulcus [51].

In C5, the vaginal process of the petrous bone is absent (an autapomorphy of H. erectus [47]). However, there is a thickened and wrinkled crest (possibly the supratubalis process; see Figure 13) that extends, only on the left, up to the meatus, similar to what is observed in Sts19 [60], as well as in S2, S4, S17, Ngandong, and SM4 [61]. As in S4, S17, and Ngandong (6, 7, 10, 11, and 12), the carotid foramen in C5 is located posterior to the STF.

Similarly to the Ngandong and SM3 specimens, as described by Zhang (Doctoral dissertation, [53]), the mandibular fossa of C5 is deep. A short lateral part of the posterior margin of the mandibular fossa is open, due to the absence of the postglenoid process. The tympanic plate, mediolaterally short and coronally oriented, is higher than the articular eminence; its anterior surface is convex. The auditory meatus is oval, oriented almost vertically, and it is separated from the mastoid process.

In C5, the mastoid process is small, reflecting the retention of the plesiomorphic condition seen in H. erectus [47,56,57]. The anterior mastoid tubercle is absent, and the digastric sulcus is closed anteriorly (plesiomorphy) [Supplementary Table S2]. The anterior mastoid tubercle is also absent in early Proto-Neanderthals, such as the Atapuerca-SH [62] and BSV2 samples [51]. While the presence of an anterior mastoid tubercle is generally considered an autapomorphic trait of Neanderthals [48,54,59,63,64,65,66], Frayer [67] has reported several Neanderthal specimens lacking this feature including Gibraltar 1, La Quina 27, and Saccopastore 1 and 11 adult specimens of Krapina. The anteriorly closed digatric sulcus is a distinctive morphology consistently found in Neanderthals, although it may be present in several specimens from the Lower Zhoukoudian Cave [49]. This future is described as an elevation of the floor of the digastric sulcus in the anterior part, forming a saddle-like rise that nearly obliterates the sulcus [41,49]. A similar feature was also described by Guipert et al. [51] in the Proto-Neanderthal BSV2 specimen.

C5 calvarium, unlike C1 and similar to the Ngandong specimen, has a squama temporalis with a flat upper edge. In contrast, the apomorphic condition of a convex upper border of the squama temporalis is observed in Middle Pleistocene samples from Africa (Bodo, Salé), Europe (SH sample, Petralona and Steinheim), and Asia (Dali), as well as in Neanderthals and modern humans [41,49]. Furthermore, in C5, there may be traces of an atypical intracranial sinus drainage pattern (specifically, an arborizing sigmoid sinus), as described by Schwartz [40] in S2 and S4. This pattern consists of a distinct groove diverging from the sigmoid sinus. In C5, a distinct but small sulcus is visible near the left sigmoid sinus (Supplementary Figure S8), which could represent a remnant of the same system or a variant. In any case, this drainage model of the sinus is considered by the author to be potentially apomorphic for H. erectus, as seen in Trinil 2 [40].

Occipital bone C5 and C8. In C5, the inion is located well above the endinion, whereas in Manot 1, the inion is located below the endinion. Although the endinion region of C8 is heavily concretioned, it can still be determined that the inion is situated immediately above the endinion. The separation between inion and endinion is taxonomically important, as the endinion being located well below the inion is considered a classic anatomical characteristic of H. erectus [68]. However, this condition has also occasionally been observed in Neanderthals, where it is regarded as a plesiomorphic character. The external squama occipitalis of C5 has a small, shallow, rounded suprainiac fossa centrally located between the supreme and superior nuchal lines. This positioning creates a depression in the external occipital protuberance, interrupting the slight and straight occipital torus and resulting in a double arch morphology reminiscent of some Indonesian specimens (Ngandong7 and 12). Schwartz and Tattersall [69] describe the occipital torus of all Ngandong specimens as having variable prominence, lateral extension to the asterion, and two curved nuchal lines that join at the midline to produce a strong external occipital protuberance. Thus, on each side, the lower edge of the “torus” appears bow-shaped, which, according to the authors [69], accounts for the double-arched description of the occipital torus in the Ngandong specimens. In C5, Ngawi1 and S3, the morphology of the occipital torus is similar to the Ngandong specimens, but less prominent [69]. In contrast, C8 exhibits a convex and low occipital plane that flattens into the suprainiac fossa, with no occipital bun present. The heavily eroded nuchal torus has ectocranial thickening located above the upper nuchal line, and the suprainiac fossa at its upper edge helps define the “bilateral arch” morphology. This morphology, which is bilaterally curved and poorly defined laterally, is typical of Neanderthals [45]. The “torus” lacks distinct margins, tapering above and below, and the transverse torus is thickened medially but not defined laterally. External occipital protuberance is absent. These features together define the “classical” morphology of the Neanderthal posterior neurocranium [52].

Skull thickness. The results of non-linear metric values constituted by the cranial thickness (Supplementary Tables S5–S8) indicate that C4 and C5 have cranial bone thicknesses that are significantly greater compared to that of classical Neanderthals such as C1. Following in-depth investigations, we found no evidence of a pathological component for this variant in the absence of evident pathognomic osteolithic alterations. Significant cranial thickness has been documented in numerous diachronic and geographically distant human fossil specimens, including the Ceprano calvarium, which may have important phylogenetic implications. The cranial thickness of C4 and C5 (Supplementary Tables S5–S7) closely resembles that of Proto-Neanderthals, H. erectus, early archaic humans, and Middle Eastern H. sapiens. This significant cranial thickness, which is slightly greater in C4, results from an expanded diploic bone and thin inner and outer tables. In both samples, the thickness of the supraorbital torus decreases laterally, while the frontal bone is thicker than the parietal bone. The high parietal eminence values of C5 are lower than those of the Australian sample (WLH 50), similar to those of Asian and Indonesian samples, and generally differ from the Middle to Upper Pleistocene and Neanderthals values. Similarly, the elevated bregma thickness values of C4 and C5 are lower than those of the Australian sample (WLH 50), close to those of Asian and Indonesian H. erectus (Zhoukoudian, Sangiran, Ngandong) and early archaic humans. These values are similar to those of the Proto-Neanderthal sample Petralona 1, but higher than those of the Neanderthal sample. The thicknesses of C8 are higher than the Neanderthal average (except for Spy 1) and are similar to those Proto-Neanderthals, Indonesian Asian samples, and Arcaic H. sapiens (Supplementary Table S8).

C2, C3, and C6 mandibles. The fossil specimen C6, represented by a mandibular symphysis, exhibits distinctive morphological features. These include the absence of a mental trigone, a slight indication of a chin eminence (mentum), and a curvature of the mandible (incurvatio mandibulae) visible in lateral view. Additionally, the mandibular foramen is positioned horizontally, parallel to the masticatory plane. A comparison between C6 and the C2 and C3 mandibles, discovered between 1939 and 1950, reveals notable morphological variability (Figure 14). In C2, the outlines of the symphysis are difficult to discern, since there is no curvature of the mandible (incurvatio mandibulae) and no evidence of a mental trigone. The lateral marginal tubercles, which are barely perceptible, are located at the level of the canine to third premolar (C-P3), similar to the plesiomorphic condition observed in specimens such as those from Dmanisi. The mental pits and central keel are only faintly indicated. C3 and C6 share most features with C2, except for a slight indication of incurvatio mandibulae; in C6, this may result from bone atrophy due to tooth loss during life (intra-vitam). C6 also has a smaller bicanine width than C3 and closely resembles C2 in this respect. As reported by Vialet et al. [70], the absence of a bony chin is characteristic of the Middle Pleistocene, while the mental trigone—a triangular projection at the front of the mandible—appeared early in the evolution of the genus

Homo. According to these authors, the mandibles of OH 7 and OH 3 from the Lower Pleistocene possess both the bony chin (mentum osseum) and the mental trigone. The mental trigone is also present in KNM-ER 730, S9, and S22, whereas only a small mental protrusion is observed in the Dmanisi mandibles and in specimen ATE9-1 from the Sima del Elefante site (Sierra de Atapuerca). In the Middle Pleistocene, this feature is described in Tighenif 1 and 2 and in the Zhoukoudian mandible. Notably, the symphysis of the Circeo mandibles closely resembles that of the Montmaurin-LN mandibles, displaying a “primitive” configuration that lacks the defining characteristics of the bony chin seen in H. sapiens. This condition is typical of most Middle European Pleistocene mandibles, with the exception of two specimens from the Atapuerca-SH site [70]. In mandible C6, the fossa digastrica is directed downward and posteriorly, as observed in C2 and C3. This orientation is a pattern documented in Neanderthals, which appears to diverge from the downward-facing plesiomorphic model and the generally posterior-facing modern human model [70]. The C6 mandible has a single horizontal oval mandibular foramen (Neanderthal-like) on the right side, located below the M1 (P4) position; the left side is incomplete (Supplementary Table S9). In contrast, the C2 mandible, similar to the Montmaurin-LN mandible, possesses two foramina on both the right and left sides of the body, with the main foramina situated below the M1 position and smaller foramina located just beneath them. These paired foramina appear to be connected, separated only by a bony bridge that features a longitudinal groove on the left side. The C3 mandible also exhibits two foramina on each side, although the second foramen on the left is not clearly visible. The larger foramina are positioned below the M1-P4 region, while the smaller ones, as in C2, are located beneath the main foramina and are similarly connected by a bony bridge (Supplementary Table S9). The presence of multiple foramina is not uncommon in Early and Middle Pleistocene mandibles and is most frequently observed in Pleistocene Asian specimens [70]. In terms of their position, the plesiomorphic condition is characterized by foramina located more anteriorly (at the P3-P4 level), whereas a foramen situated below the M1-P4 or M1 is typical of Neanderthals and most Central European Pleistocene hominins [70]. The mandibles confirm what was underlined for the cranial findings. The three mandibles C2, C3, and C6 show apomorphic characteristics, such as the presence of a slight incurvatio mandibulae in lateral view (C3 and C6) and the localization of the mental foramen, which is in the direction of the symphysis between M1 and P4.

Superior maxillary C9. Circeo 9 (C9) [Supplementary Figure S10] consists of the palatine process of the maxilla. Its poor state of preservation—being heavily eroded and incomplete—precluded an in-depth comparative morphometric analysis. Osteolytic alterations associated with tooth loss (showing varying degrees of atrophy) and a thickness asymmetry between the two portions of the palatine bone were observed. These findings indicate the need for targeted tomographic analysis, which is beyond the scope of the present study. From an exclusively morphological point of view, we cannot completely exclude a hypothetical relationship with C6, as well as with C2 or C3, a hypothesis that will require future investigations and insights. The only comparative feature that emerges relates to the nasal cavity, specifically the presence of a single, superiorly elevated, midline-grooved spinal ridge. This feature is considered a possible Sima-hominin autapomorphy, with some variants (such as lacking a midline groove) described in Petralona. It is absent in the H. sapiens specimens described by Schwartz et al. [46], as well as in Homo neanderthalensis (Gibraltar 1; La Chapelle-aux-Saints), Homo antecessor (Gran Dolina ATD6-69), the Steinheim cranium, and specimens often attributed to H. heidelbergensis (Kabwe, Arago, Bodo, Dali, and Jinniushan). This feature is considered as a possible Sima-hominin autapomorphy [46]. Neanderthals, and likely Circeo 1, develop a posterior nasal crest that extends superiorly toward the nasal bones, thereby creating an anterior vestibule distinct from the rest of the nasal cavity [46]. In C9, although much of this region is missing, both sides of the nasal cavity preserve a low nasal crest. Based on its location and orientation, we identify this as a posterior nasal crest, but it does not appear to exhibit Neanderthal characteristics. This aspect warrants further investigation from a phyletic point of view.