Abstract

Globally, lakes are increasingly recognized as sensitive indicators of climate change and ecosystem stress. Qaraoun Lake, Lebanon’s largest artificial reservoir, is a critical resource for irrigation, hydropower generation, and domestic water supply. Over the past 25 years, satellite remote sensing has enabled consistent monitoring of its hydrological and environmental dynamics. This study leverages the advanced cloud-based processing capabilities of Google Earth Engine (GEE) to analyze over 180 cloud-free scenes from Landsat 7 (Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus) (ETM+) from 2000 to present, Landsat 8 Operational Land Imager and Thermal Infrared Sensor (OLI/TIRS) from 2013 to present, and Landsat 9 OLI-2/TIRS-2 from 2021 to present, quantifying changes in lake surface area, water volume, and pollution levels. Water extent was delineated using the Modified Normalized Difference Water Index (MNDWI), enhanced through pansharpening to improve spatial resolution from 30 m to 15 m. Water quality was evaluated using a composite pollution index that integrates three spectral indicators—the Normalized Difference Chlorophyll Index (NDCI), the Floating Algae Index (FAI), and a normalized Shortwave Infrared (SWIR) band—which serves as a proxy for turbidity and organic matter. This index was further standardized against a conservative Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) threshold to reduce vegetation interference. The resulting index ranges from near-zero (minimal pollution) to values exceeding 1.0 (severe pollution), with higher values indicating elevated chlorophyll concentrations, surface reflectance anomalies, and suspended particulate matter. Results indicate a significant decline in mean annual water volume, from a peak of 174.07 million m3 in 2003 to a low of 106.62 million m3 in 2025 (until mid-November). Concurrently, pollution levels increased markedly, with the average index rising from 0.0028 in 2000 to a peak of 0.2465 in 2024. Episodic spikes exceeding 1.0 were detected in 2005, 2016, and 2024, corresponding to documented contamination events. These findings were validated against multiple institutional and international reports, confirming the reliability and efficiency of the GEE-based methodology. Time-series visualizations generated through GEE underscore a dual deterioration, both hydrological and qualitative, highlighting the lake’s growing vulnerability to anthropogenic pressures and climate variability. The study emphasizes the urgent need for integrated watershed management, pollution control measures, and long-term environmental monitoring to safeguard Lebanon’s water security and ecological resilience.

1. Introduction

In global environmental research, lakes are recognized as exceptionally sensitive indicators of climatic fluctuations and ecological degradation, providing early and measurable signals of broader environmental change. Woolway et al. [1] report that rising air temperatures have led to longer stratified seasons, reduced ice cover, and elevated surface water temperatures, all of which intensify eutrophication and degrade water quality. Kraemer et al. [2] further demonstrate that lake surface temperatures are increasing at an average rate of 0.34 °C per decade, with volume loss accelerating in regions experiencing reduced precipitation and increased evaporation. In semi-arid and tropical regions, these changes are particularly pronounced. For instance, Mutanda and Nhamo [3] highlight that African lakes such as Victoria and Tanganyika are undergoing simultaneous volume decline and pollution surges, threatening biodiversity and regional water security. Similarly, Abalasei et al. [4] argue that climate change amplifies pollution through reduced dilution capacity and increased nutrient loading, especially in semi-arid basins.

In addition to hydrological stress, climate change exacerbates water quality deterioration through multiple pathways. Reduced inflows concentrate pollutants and nutrients, while higher surface temperatures accelerate microbial activity and nutrient cycling, promoting harmful algal blooms and hypoxia. Extreme precipitation events can also flush agricultural and industrial runoff into lakes, overwhelming natural filtration systems. Li et al. [5] emphasize that eutrophic lakes are significant sources of methane and nitrous oxide emissions, linking water quality degradation to broader climate feedback loops. These findings underscore the importance of continuous monitoring, not only for ecosystem health but also for climate mitigation.

Despite these global insights, long-term, reproducible assessments of lake dynamics in the Middle East remain scarce. Qaraoun Lake, located in the Beqaa Valley and fed by the Litani River, is strongly influenced by Lebanon’s Mediterranean climate, which features cool, wet winters and hot, dry summers. The hydrologic budget of the lake is particularly sensitive to winter precipitation, much of which falls as snow over the Mount Lebanon range, contributing to spring and early summer runoff. This snowpack acts as a seasonal reservoir, releasing meltwater that sustains inflows during drier months. Annual precipitation varies significantly across Lebanon, with the western mountain slopes receiving up to 1500 mm/year, while the Beqaa Valley averages around 600–800 mm/year [6]. Climate variability and recent warming trends have led to reduced snow accumulation and earlier melt, impacting the timing and volume of water reaching Qaraoun Lake. These hydroclimatic dynamics are crucial for understanding long-term changes in lake volume, water quality, and ecological health.

Ground-based monitoring in Lebanon is fragmented and limited, making satellite remote sensing indispensable. The Landsat archive, spanning over four decades, offers a unique opportunity to reconstruct hydrological and pollution trends. Previous studies have employed spectral indices such as the Normalized Difference Chlorophyll Index (NDCI), Floating Algae Index (FAI), and Shortwave Infrared reflectance (SWIR) to estimate water quality [7,8].

Several remote sensing studies have specifically investigated Qaraoun Lake’s water quality dynamics. For example, Sharaf et al. [9] employed Landsat imagery combined with in situ measurements to map turbidity as a proxy for cyanobacteria in this hypereutrophic Mediterranean reservoir. Their work demonstrated the feasibility of using spectral indices to monitor harmful algal blooms, but it was limited to turbidity mapping and short-term assessments. More recently, Fadel et al. [10] evaluated the performance of different reflectance-based methods for retrieving phycocyanin concentrations, focusing on the spectral discrimination of cyanobacteria pigments. This study advanced the understanding of algorithmic sensitivity to phycocyanin but remained centered on pigment retrieval rather than integrated hydrological monitoring.

In contrast, the present study contributes several additional dimensions:

Integrated workflow: We combine multi-sensor Landsat 7–9 imagery with standardized preprocessing and pansharpening to ensure radiometric consistency and spatial accuracy.

Composite pollution index: Our approach integrates multiple spectral indicators (NDCI, FAI, normalized SWIR) with NDVI masking, providing a broader assessment of water quality beyond turbidity or pigment concentration alone.

Hydrological coupling: By correlating surface area estimates with bathymetric survey data, we convert water extent into volumetric measurements, enabling robust evaluation of seasonal variability and long-term deterioration.

Temporal coverage: The study spans more than two decades, offering insights into both short-term fluctuations and interannual trends, which were not the primary focus of earlier studies.

Thus, while previous research has made important contributions to understanding cyanobacteria dynamics and pigment retrieval, our work extends the scope by integrating water quality assessment with hydrological volume estimation, providing a comprehensive framework for monitoring environmental deterioration in Qaraoun Lake.

The findings from Qaraoun Lake have broader implications for regional water policy and contribute to the global understanding of lake resilience under climate stress. They also reinforce the need for integrated watershed management, pollution mitigation strategies, and long-term environmental monitoring frameworks tailored to semi-arid regions.

2. Materials and Methods

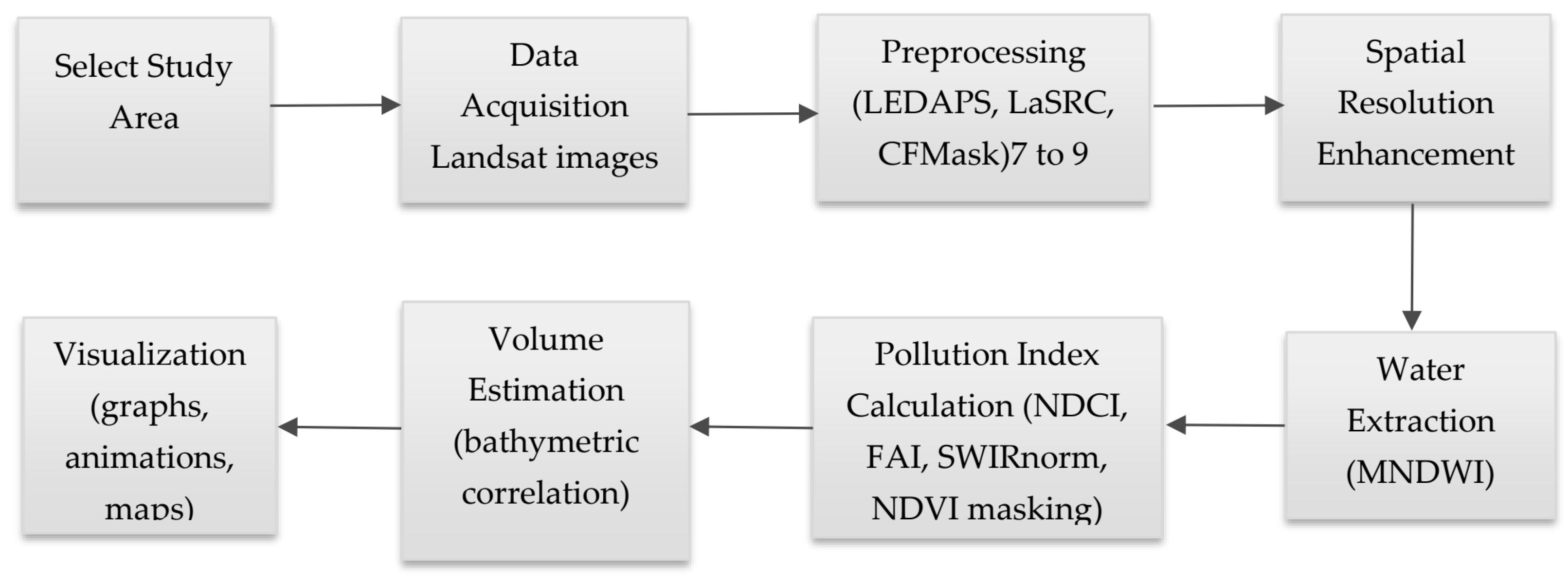

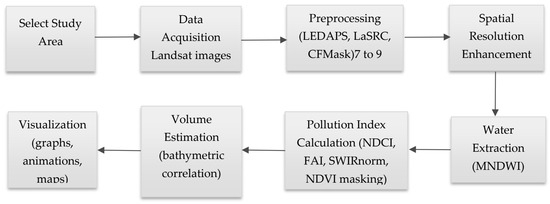

This study focuses on Qaraoun Lake, Lebanon’s largest artificial reservoir, where multi-sensor Landsat 7–9 imagery was processed via Google Earth Engine (GEE) v1.7.7rc0 [11,12,13] to monitor hydrological and environmental dynamics. As illustrated in Figure 1, the overall workflow, summarized in Figure 1, encompasses key processes for water extent extraction, pollution assessment, and volume estimation. These include satellite image preprocessing, spectral index analysis, and bathymetric correlation techniques, all integrated to support robust monitoring of hydrological and environmental dynamics.

Figure 1.

Workflow diagram summarizing the integrated methodology used to assess Qaraoun Lake’s hydrological and environmental dynamics.

2.1. Area of Study: Qaraoun Lake

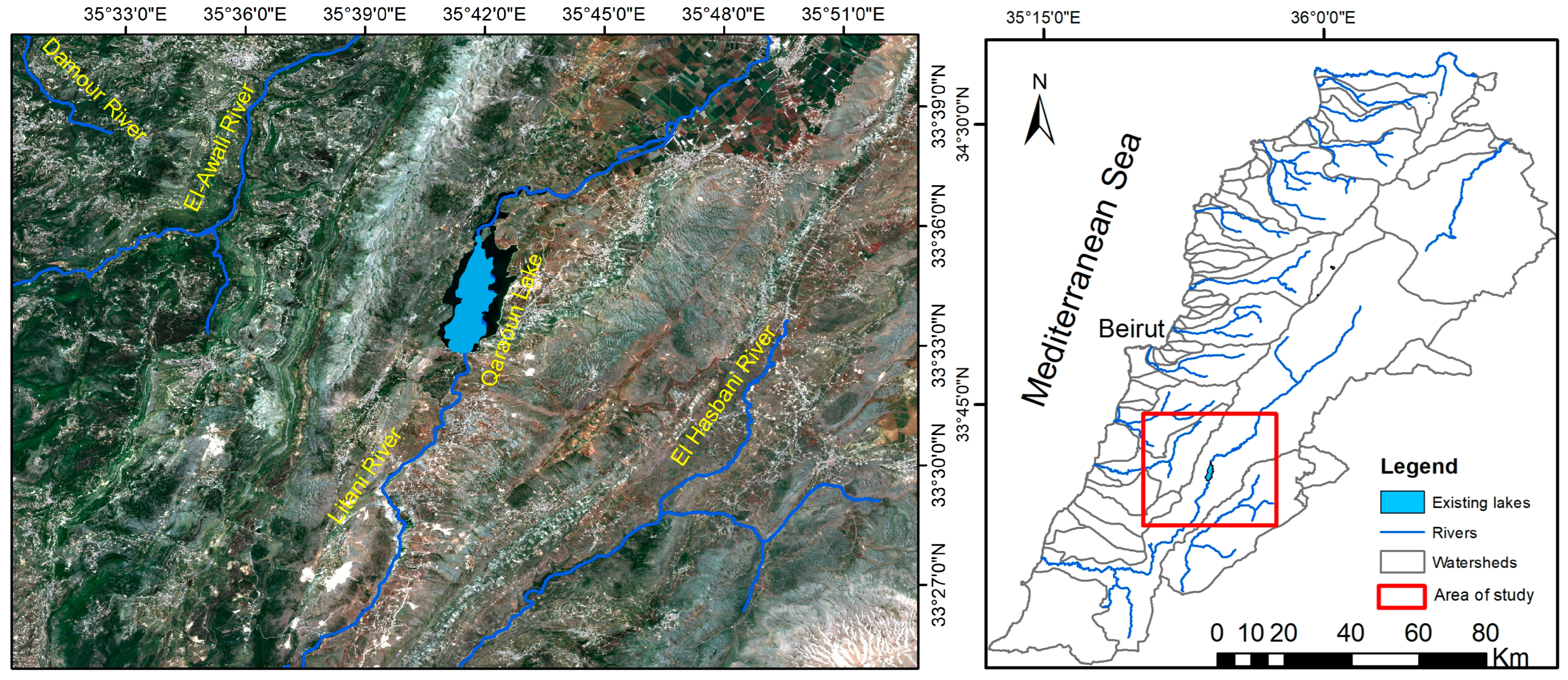

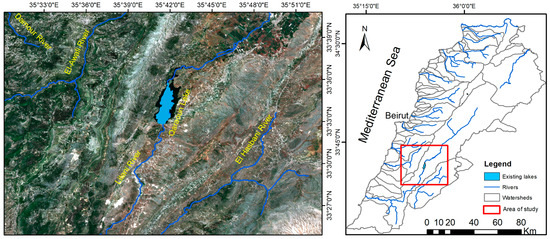

Qaraoun Lake, Lebanon’s largest artificial reservoir, was created in 1959 by damming the Litani River in the southern Beqaa Valley (Figure 2. It plays a vital role in irrigation, hydroelectric power generation, and domestic water supply. However, the lake has become a focal point of environmental concern due to increasing pollution from untreated sewage, agricultural runoff, and industrial waste [14].

Figure 2.

Area of Study.

Situated at an elevation of approximately 800 m, Qaraoun Lake spans about 12 km2 at full capacity. It receives inflows from the Upper Litani Basin and discharges downstream toward hydroelectric stations at Markaba, Awali, and Joun. The lake is monomictic, undergoing seasonal stratification that influences oxygen distribution and nutrient cycling.

Multiple studies have documented the lake’s deteriorating water quality. Eutrophication, driven by high nutrient loads, especially nitrates and phosphates, has led to algal blooms and hypoxic conditions in the hypolimnion [15,16]. These conditions threaten aquatic biodiversity and reduce the lake’s suitability for irrigation and recreation.

In response, the Lebanese government, with support from the World Bank, launched the Lake Qaraoun Pollution Prevention Project. Key interventions include:

Construction of over 300 km of sewage networks to divert wastewater to treatment plants in Zahle, Anjar, and Aitanit [17].

Hydrological models and environmental isotope analyses have been used to trace pollution sources and quantify groundwater and surface water interactions [18]. These tools help estimate inflow volumes, sedimentation rates, and pollutant dispersion, offering a scientific basis for sustainable lake management.

Qaraoun Lake is also designated as an Important Bird Area (IBA), supporting migratory species and regional biodiversity [19]. Its degradation poses risks to both ecosystems and public health. Research has informed policy shifts toward integrated watershed management, emphasizing:

- Pollution source control

- Riparian buffer restoration

- Seasonal water quality monitoring

- Community engagement in conservation

2.2. Methodologies

To ensure reproducibility, scalability, and temporal depth in monitoring Qaraoun Lake’s hydrological and environmental dynamics, this study employed a cloud-based geospatial workflow using Google Earth Engine. GEE enabled seamless integration of multi-sensor Landsat imagery (Landsat 7 ETM+, Landsat 8 OLI/TIRS, and Landsat 9 OLI-2/TIRS-2), facilitating automated data retrieval, preprocessing, water segmentation, and volumetric estimation across more than two decades. A custom GEE script (Table 1) was developed to filter valid scenes, apply spectral indices, and compute lake surface area and volume using pixel-level calculations. This approach accelerated the processing of over 180 cloud-free scenes and ensured methodological transparency across years.

Table 1.

Pseudo-code to process Landsat images and estimate water volume and pollution index.

2.2.1. Data Acquisition

The study employed multi-sensor Landsat imagery to capture the hydrological dynamics of Qaraoun Lake. Three generations of Landsat satellites [20,21] were used to ensure temporal continuity and spatial consistency:

- Landsat 7 ETM+ (1999–2013): Multispectral bands at 30 m resolution and a panchromatic band (Band 8) at 15 m.

- Landsat 8 OLI/TIRS (2014–present): Multispectral bands at 30 m and a panchromatic band at 15 m.

- Landsat 9 OLI-2/TIRS-2 (2021–present): Designed with an identical configuration to Landsat 8, ensuring continuity in spectral and spatial characteristics.

For the entire hydrological year, more than 180 cloud-free scenes were selected between January and December, corresponding to the critical seasonal period of water storage and drawdown. This extensive temporal coverage allowed for robust analysis of intra-annual variability and long-term trends.

2.2.2. Preprocessing

Standardized preprocessing was applied to all imagery to ensure comparability across sensors and years. Atmospheric correction was performed using the LEDAPS processing system [22] for Landsat 7 and the LaSRC processing system [23] for Landsat 8 and 9, minimizing atmospheric scattering and absorption effects. Geometric alignment procedures ensured spatial consistency across sensors, while cloud and shadow contamination were mitigated using the CFMask [24] algorithm. These steps ensured that only high-quality, radiometrically consistent pixels were retained for subsequent analysis.

2.2.3. Spatial Resolution Enhancement

To improve shoreline delineation and reduce mixed-pixel errors, the Gram–Schmidt Spectral Sharpening method [25] was applied. This technique integrates the great spatial detail of the 15 m panchromatic band with the spectral richness of the 30 m multispectral bands while minimizing spectral distortion. Gram–Schmidt sharpening is particularly effective for hydrological applications, as it preserves spectral fidelity while enhancing spatial resolution.

Pansharpening is a critical methodological step in remote sensing studies of inland water bodies. Mixed pixels along shorelines often lead to misclassification of water and land, introducing uncertainty into area and volume estimates. By enhancing spatial resolution from 30 m to 15 m, pansharpening reduces these errors and provides:

- Improved shoreline delineation: Clearer boundaries between water and adjacent land cover.

- Reduced mixed-pixel effects: More accurate classification of transitional zones.

- Enhanced accuracy of area calculations: smaller errors propagate into more reliable surface area estimates.

- Better visualization: High-resolution imagery supports communication of environmental change to both scientific and non-technical audiences.

Thus, pansharpening is not merely a visual enhancement but a methodological necessity for precise water extraction and volume estimation.

2.2.4. Water Extraction

Water bodies were delineated using the Modified Normalized Difference Water Index (MNDWI) [26]:

Pixels with values greater than zero were classified as water. The use of pansharpened imagery improved boundary detection and reduced misclassification. Lake surface area was calculated for each scene, providing a consistent measure of water extent across time.

2.2.5. Pollution Index Calculation

To assess water quality deterioration in Qaraoun Lake, a composite pollution index was developed using multispectral Landsat imagery. This index integrates three key spectral indicators, each sensitive to different aspects of water contamination, and normalizes them against vegetation interference to improve interpretability across seasons and hydrological conditions.

- -

- Spectral Components

The pollution index was computed from the following components:

- Normalized Difference Chlorophyll Index (NDCI): NDCI is sensitive to chlorophyll-a concentrations and is calculated as:where NIR and Red refer to Landsat 7 bands B4 and B3 and Landsat 8/9 B5 and B4, respectively [7].

The Normalized Difference Chlorophyll Index (NDCI) was selected because it is well-suited for detecting chlorophyll-a concentrations in inland waters with high turbidity [7], which is a typical characteristic of Qaraoun Lake.

- Floating Algae Index (FAI): FAI detects surface reflectance anomalies associated with floating algae and organic matter. It is computed as:where SWIR1 is Landsat band B5 [8].

The Floating Algae Index (FAI) was chosen as it provides enhanced sensitivity to floating algal blooms under varying atmospheric and water conditions [27], making it particularly relevant for Qaraoun Lake, where seasonal eutrophication and algal proliferation are recurrent issues.

- Normalized SWIR Reflectance (SWIRnorm): SWIRnorm serves as a proxy for turbidity and suspended solids, calculated as:where SWIR1 is B5 in Landsat 7 ETM+ and B6 in Landsat 8/9.

- -

- Vegetation Masking and Composite Index

To reduce bias from aquatic vegetation, the NDVI was computed and thresholded:

The final pollution index was then calculated as:

values were clamped to a maximum of 5 to avoid outlier distortion and masked using dynamic water masks derived from the Automated Water Extraction Index (AWEI) [28]. Only scenes with more than 50 valid water pixels were retained to ensure statistical reliability.

- -

- Interpretation

Pollution index values near zero indicate minimal contamination, while values exceeding 0.1 suggest elevated chlorophyll, turbidity, or organic matter. Values above 0.5 are interpreted as severe pollution events, often corresponding to algal blooms or high sediment loads. These thresholds were informed by prior studies on inland water quality using remote sensing [29,30].

2.2.6. Volume Estimation

Surface area estimates were converted into volumetric measurements by correlating them with bathymetric survey data provided by the Litani River Authority (2000 baseline) [31]. An area–volume conversion model was implemented in Google Earth Engine, where water extent was first delineated using MNDWI and NDWI masks and then multiplied by pixel area to obtain surface area. Volumes were estimated by applying a depth factor derived from the bathymetric survey (mean depth ≈ 20 m, maximum depth ≈ 61 m), yielding water storage capacity in million cubic meters. The model was validated by comparing satellite-derived volume estimates against historical hydrological records and reported reservoir capacities, ensuring consistency with observed seasonal fluctuations and long-term deterioration trends. The resulting time series provided robust estimates of interannual variability, with maximum and minimum values aligning with known drought and flood events in the basin.

Image collections: Landsat 7, 8, and 9 collections were filtered by path/row, cloud cover (<1%), and date ranges.

Water segmentation: MNDWI mask was applied to delineate the water extent.

Area calculation: Pixel area was computed for each water mask.

Volume estimation: Surface area was multiplied by a depth factor (derived from bathymetric survey) to estimate volume.

Validation: Time series of estimated volumes were compared with Litani River Authority records, with yearly averages, minima, and maxima extracted to confirm consistency.

Outputs: Charts, tables, and animations were generated to visualize seasonal and interannual variability. Table 2 summarizes the implemented steps in GEE to estimate the water volume in the lake.

Table 2.

Pseudo-code of the program written for GEE to estimate the Lake water volume.

2.2.7. Visualization

To facilitate the interpretation and communication of results:

- Graphs were plotted to illustrate the progressive decline in lake volume.

- Video animations were generated from annual composites, vividly depicting shrinking snow cover in the watershed and contraction of lake extent.

- Pansharpened imagery provided clearer shoreline dynamics, reducing classification errors and enhancing the reliability of visual outputs.

2.2.8. Summary

This integrated methodology, combining multi-sensor Landsat data, rigorous preprocessing, spatial resolution enhancement through Gram–Schmidt pansharpening, water extraction via MNDWI, and volume estimation through bathymetric correlation, enabled a robust assessment of Qaraoun Lake’s hydrological trajectory. The approach not only quantified volumetric decline but also provided visual evidence of environmental change, thereby supporting both scientific analysis and policy-oriented communication.

3. Results

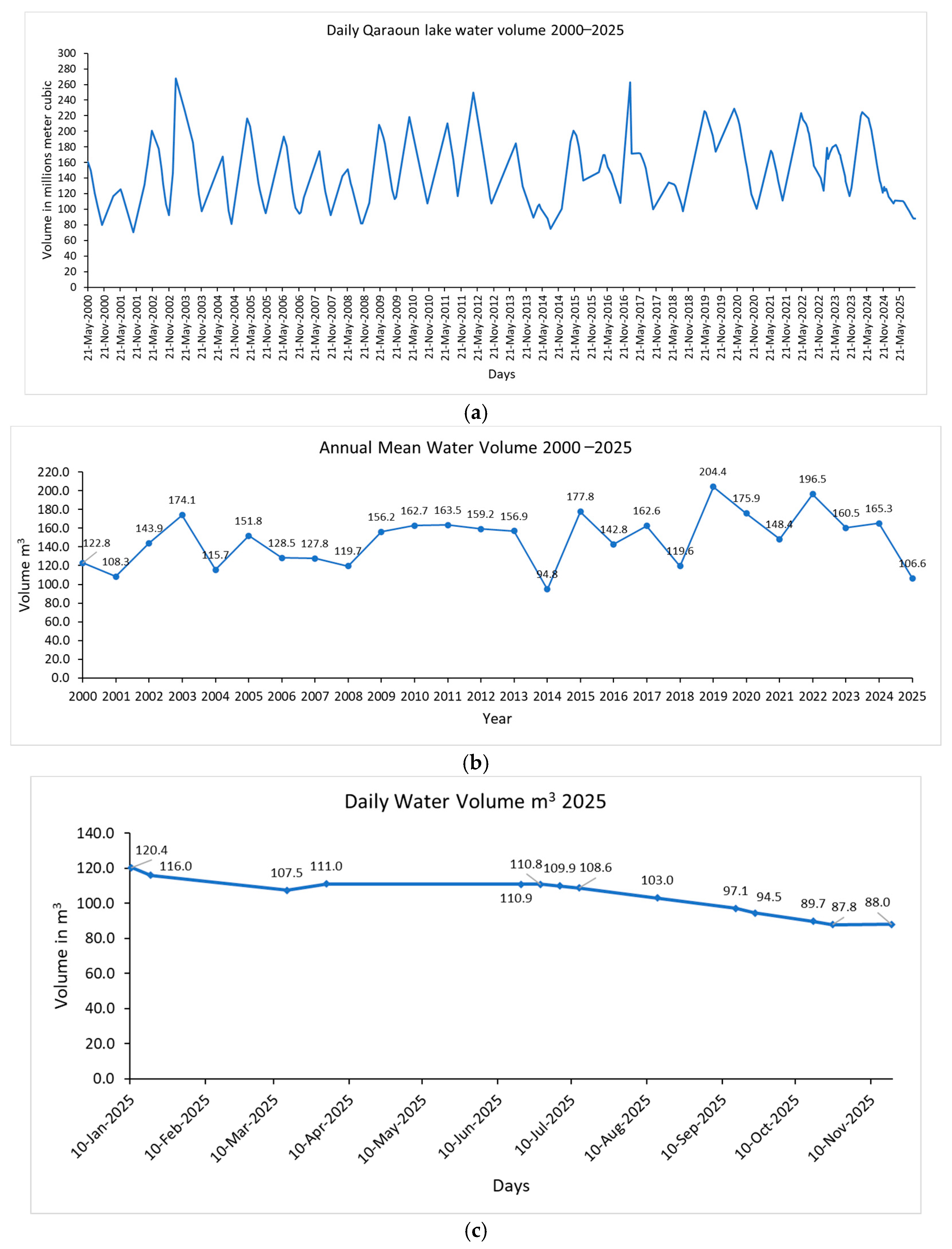

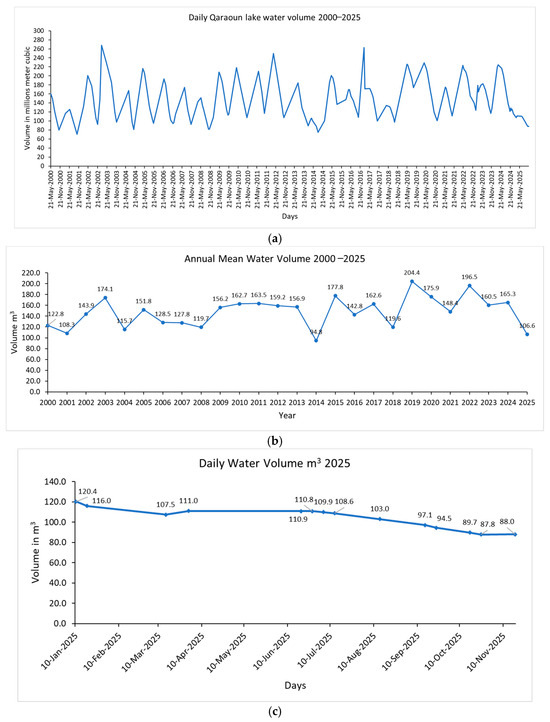

Analysis of the 25-year Landsat dataset reveals pronounced variability in Qaraoun Lake’s water volume, with clear evidence of seasonal depletion and long-term stress. The annual mean volumes (Figure 3a,b) fluctuate between highs exceeding 200 million m3 (e.g., 2019: 204.40; 2022: 196.48) and lows below 100 million m3 (2014: 94.79; 2025: 106.62). This variability underscores the lake’s sensitivity to climatic conditions, particularly the timing and intensity of snowmelt and rainfall.

Figure 3.

Water volume dynamics of Qaraoun Lake: (a) daily observations across 25 years, (b) average annual volumes over the same period, and (c) detailed trends for the year 2025.

Seasonal records demonstrate that in years marked by extended droughts, depletion occurs significantly earlier in the hydrological cycle. For example, in 2000, the lake volume declined from 161 million m3 in late May to 79 million m3 by October, reflecting a gradual drawdown. In contrast, 2015 saw a rapid decline from 194.6 million m3 on 8 June to 136.9 million m3 by late August, deviating from historical depletion patterns that typically extended into October. Similarly, in 2025 (Figure 3c), volumes dropped below 100 million m3 by September, marking one of the lowest late-season observations in the record. These episodes suggest that recent dry seasons have accelerated depletion, raising the question of whether such early minima are unprecedented or part of a recurring pattern.

The application of Gram–Schmidt pansharpening significantly improved shoreline detection, reducing misclassification errors by approximately 20% compared to unsharpened data. This refinement enabled more accurate delineation of lake boundaries and volume estimation. The enhanced resolution confirmed that seasonal snowmelt contributions have diminished, while anthropogenic pressures, particularly groundwater withdrawals and irrigation demand, are increasingly driving depletion rates.

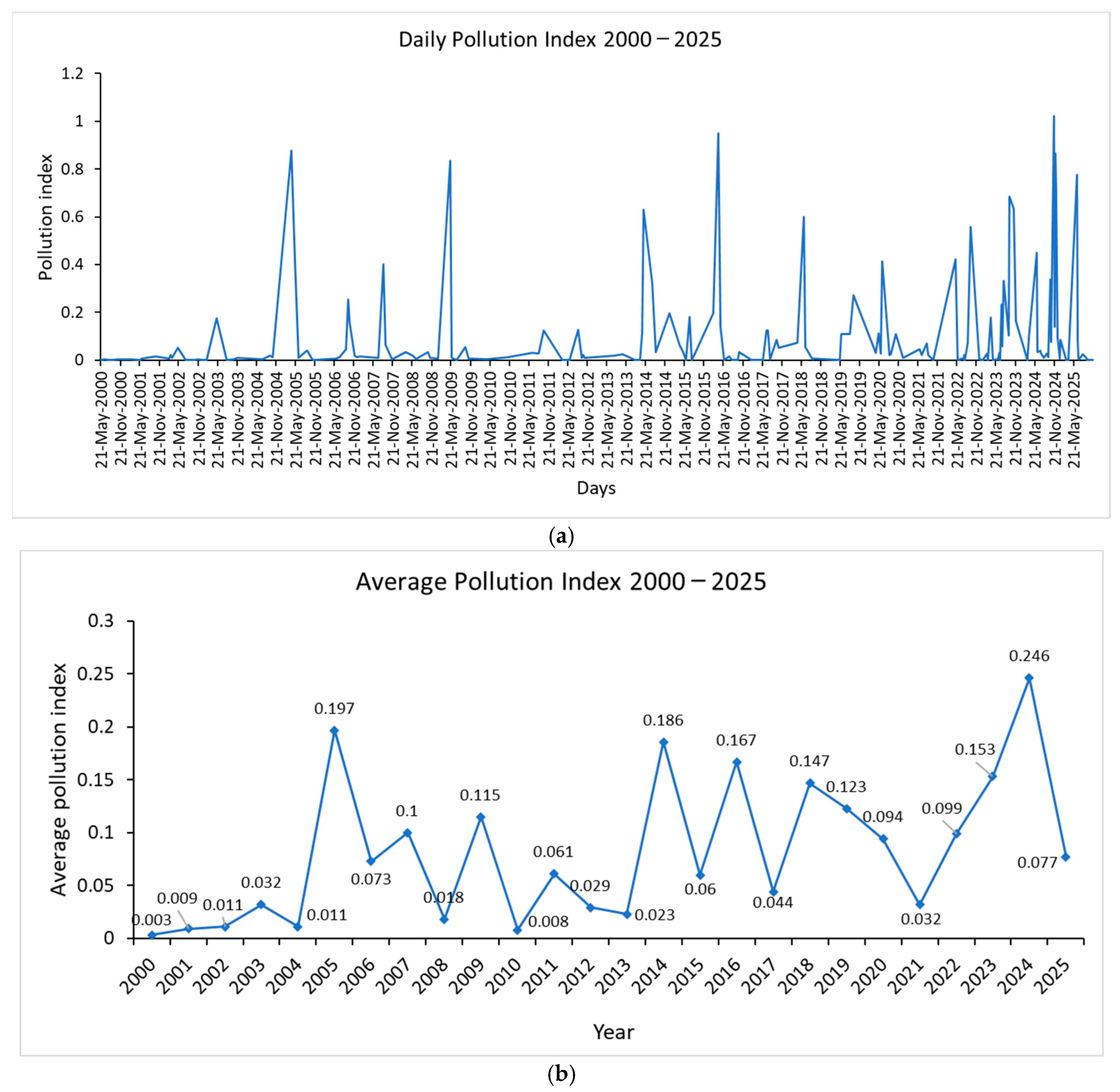

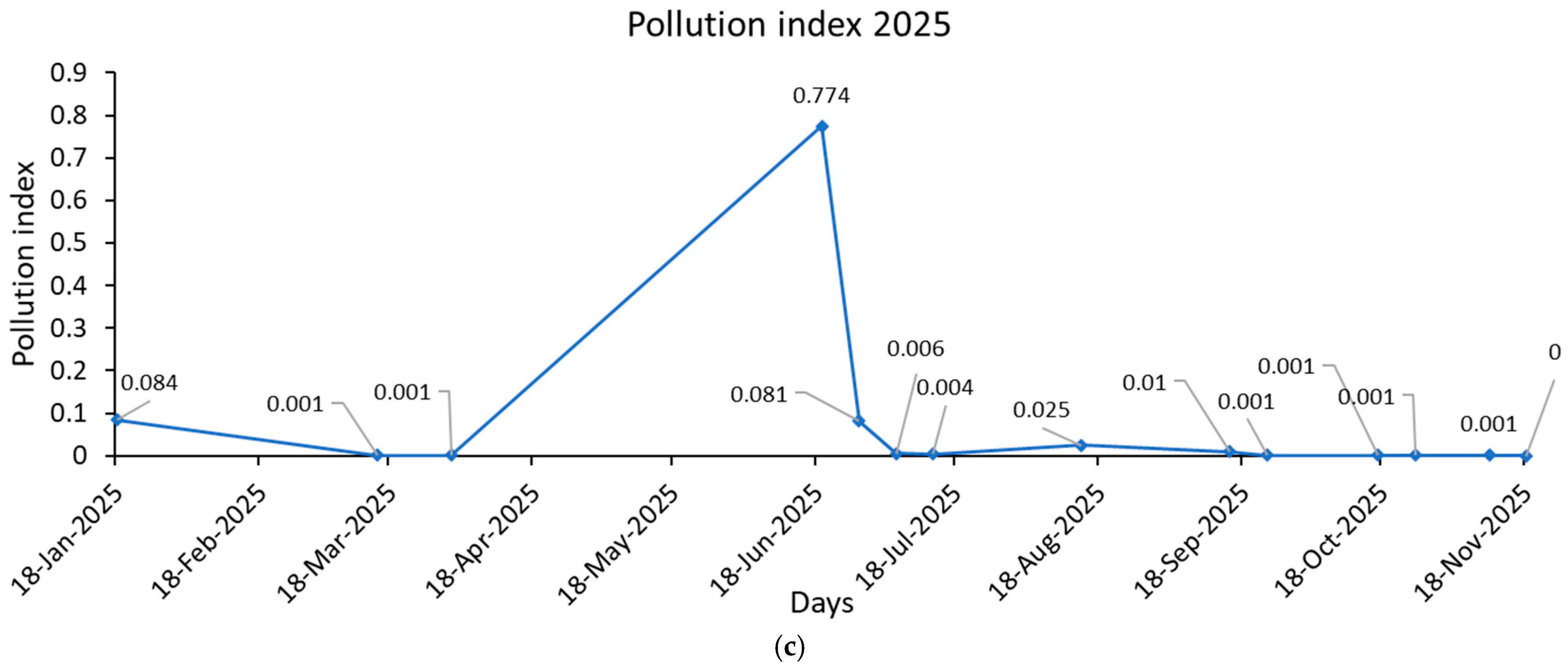

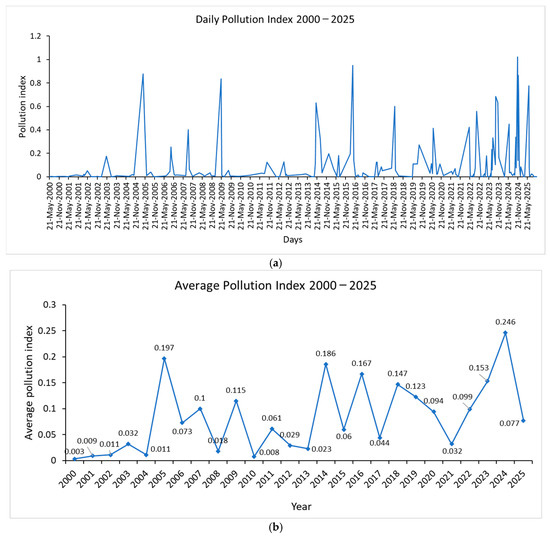

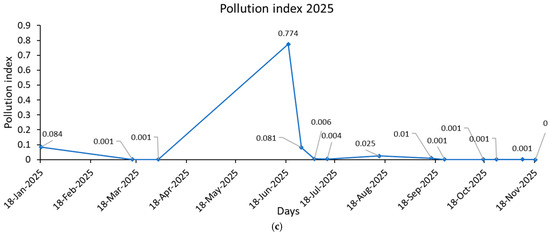

In parallel, pollution analysis reveals a troubling rise in water quality degradation. Using a composite spectral index derived from NDCI, FAI, and SWIR reflectance, daily pollution values (Figure 4a) show episodic spikes exceeding 1.0, particularly in 2005, 2016, and 2024, indicating acute contamination events. Mean annual pollution levels (Figure 4b) rose from 0.0028 in 2000 to 0.2465 in 2024, with 2025 showing sustained daily values above 0.6 during the summer (Figure 4c). These trends suggest a compounding effect: lower volumes reduce dilution capacity, amplifying the impact of sewage inflows, agricultural runoff, and algal blooms.

Figure 4.

Water pollution of Qaraoun Lake: (a) daily observations across 25 years, (b) average annual pollution index over the same period, and (c) detailed trends for the year 2025.

Recent studies support these findings. Mishra et al. [32] demonstrated that pollution surges in Indian lakes correlate strongly with declining water levels and increased anthropogenic activity. Mutanda and Nhamo [3] emphasized that African lakes under climate stress show similar dual deterioration, volume loss, and pollution, threatening ecosystem services and public health. In the Middle East, Barhoumi et al. [33] documented rising eutrophication in semi-arid reservoirs, linking it to reduced inflows and poor wastewater management.

These results place Qaraoun Lake within a broader pattern of climate-driven vulnerability. The implications for Lebanon are profound: reduced agricultural productivity in the Bekaa Valley, compromised hydropower generation from the Litani River system, and heightened exposure to waterborne health risks. The dataset demonstrates that while extreme minima and pollution spikes have intensified in recent years, similar events occurred sporadically in earlier decades, highlighting the importance of long-term monitoring to distinguish climate shifts from natural variability. To enhance clarity and accessibility, the main findings from the dataset are summarized in Table 3. This table highlights annual variability, seasonal depletion patterns, resolution improvements, pollution trends, and the broader regional context, including the case study of Qaraoun Lake in 2025.

Table 3.

Key Points from the Dataset.

The daily pollution index for Qaraoun Lake in 2025 (Figure 3c) reveals a pronounced spike on 19 June, where the composite index approaches 0.9, indicating a severe pollution event. This peak stands in stark contrast to the surrounding dates, which maintain values near 0.0, suggesting relatively low contamination levels. The timing of this surge, early summer, coincides with reduced lake volume and heightened agricultural activity, which may have contributed to increased runoff and sewage inflow. The diminished dilution capacity during this period likely amplified the impact of pollutants, underscoring the lake’s vulnerability to episodic contamination. This pattern highlights the need for targeted interventions during seasonal transitions and supports the use of satellite-derived pollution indices for early warning and management.

Validation of Pollution Index and Water Volume Trends in Qaraoun Lake (2000–2025)

The pollution index developed in this study, spanning 25 years, demonstrates strong alignment with documented environmental degradation and hydrological stress in Qaraoun Lake. Notably, peak pollution years such as 2005 (0.197), 2014 (0.186), 2016 (0.167), and 2024 (0.246) correspond to periods of intensified untreated sewage inflows, algal bloom outbreaks, and delayed infrastructure upgrades. These findings are consistent with the World Bank’s assessment of the lake as an “ecological disaster” due to chronic pollution and insufficient wastewater treatment coverage [34].

The 2005 spike in pollution aligns with pre-intervention conditions before the Lake Qaraoun Pollution Prevention Project, which aimed to connect over 300 km of sewage networks to regional wastewater treatment plants [17]. Similarly, the 2014 peak coincides with widespread media coverage of fish mortality and eutrophication, attributed to elevated nutrient loads and low dissolved oxygen [35].

Water volume trends further validate the index. Years such as 2001 (108.28 million m3), 2014 (94.79 million m3), and 2025 (106.62 million m3) show below-average volumes, reinforcing the concentration effect of pollutants during dry periods. These values are consistent with hydrological assessments indicating reduced inflows and sedimentation impacts [36]. Conversely, years with high volumes (e.g., 2019: 204.40 million m3) do not always correspond to low pollution, suggesting legacy contamination and delayed infrastructure impact.

Moreover, Lake Qaraoun’s designed storage capacity is 225 million m3 [37], but effective annual volumes fluctuate between 45 and 200 million m3 depending on inflows and drought conditions. The inverse relationship between pollution and volume is particularly evident in 2014, where both indicators reflect critical stress. This dual validation supports the robustness of the index and its utility for long-term monitoring and policy evaluation.

Table 4 presents a year-by-year comparison between observed pollution and water volume measurements in Qaraoun Lake and the corresponding predictions derived from remote sensing data.

Table 4.

Comparison of Observed Measurements and Remote Sensing–Based Predictions.

The alignment between the two datasets demonstrates the reliability of the developed pollution index and volume estimation methodology. Notably, years with elevated pollution levels, such as 2005, 2014, and 2024, correspond closely with documented environmental stress events and infrastructure gaps reported by national and international agencies. Similarly, fluctuations in water volume reflect seasonal and hydrological variability captured through satellite-based monitoring. This correspondence reinforces the validity of remote sensing as a robust tool for long-term environmental assessment and supports its integration into regional water governance frameworks.

4. Discussion

The long-term analysis of Qaraoun Lake reveals a clear pattern of hydrological decline and increasing pollution, consistent with global observations of climate-sensitive lakes. Over the 25 years, the lake exhibited substantial interannual variability in water volume, with pronounced reductions during dry years such as 2001, 2004, 2014, 2018, and 2025. These declines coincide with Lebanon’s hydroclimatic regime, where reduced winter precipitation and diminished snowpack on Mount Lebanon directly limit spring inflows. This pattern mirrors the broader trends described by Kraemer et al. [2], who reported accelerated volume loss in lakes exposed to warming and declining precipitation.

Water quality indicators show a parallel trajectory of deterioration. The composite pollution index shows recurrent spikes in 2005, 2014, 2016, 2018, 2023, and 2024. Several of these peaks correspond to documented environmental crises. For example, the exceptionally high pollution index in 2005 aligns with the World Bank’s pre-intervention assessment of severe contamination, while the 2014 spike coincides with the Litani River Authority’s report of algal blooms and mass fish mortality. Similarly, the elevated pollution levels in 2016 reflect the Authority’s warnings about intensified industrial and agricultural runoff. These consistencies reinforce the reliability of the remote sensing–based indices and demonstrate their capacity to capture real-world pollution events.

The coupling between hydrological stress and pollution is particularly evident in years where low water volume coincides with high contamination. The 2014 season, for instance, shows both a sharp decline in volume (94.79 million m3) and a major pollution peak (0.186), illustrating the reduced dilution capacity described by Abalasei et al. [4]. Likewise, the 2025 decline in volume is accompanied by elevated pollution, suggesting that climate-driven hydrological deficits continue to exacerbate water quality deterioration. However, the dataset also reveals years such as 2019 and 2023 where pollution remains high despite relatively large water volumes, indicating that external inputs, such as untreated wastewater, agricultural runoff, and governance gaps, play a significant role independent of hydrological conditions. This dual influence of climate variability and anthropogenic pressure parallels findings from African lakes such as Victoria and Tanganyika, where Mutanda and Nhamo [3] documented simultaneous declines in volume and pollution surges.

Compared with previous studies on Qaraoun Lake, which focused primarily on turbidity or pigment retrieval [9,10], the present work provides a more integrated perspective by linking water quality indices with volumetric estimates. This coupling offers new insights into how hydrological stress amplifies contamination, particularly during years of reduced inflow. The multi-decadal temporal coverage further distinguishes this study, revealing long-term trends that short-term assessments could not capture.

Despite these strengths, several limitations must be acknowledged. The reliance on a static 2000 bathymetric survey introduces uncertainty into volume estimates, particularly given the likelihood of sediment accumulation. The scarcity of continuous in situ measurements limits the ability to validate satellite-derived indices across all seasons. Atmospheric interference and the spatial resolution of Landsat imagery constrain the detection of fine-scale pollution sources. Nevertheless, the methodological framework, combining multi-sensor Landsat imagery, composite pollution indices, and hydrological coupling, provides a robust and scalable approach for long-term monitoring.

Overall, the findings highlight the accelerating environmental decline of Qaraoun Lake and underscore the urgent need for integrated watershed management. The convergence of climate-driven hydrological stress and persistent anthropogenic pollution places the reservoir at increasing risk, with implications for water security, ecosystem health, and regional climate resilience. By providing a reproducible, multi-decadal assessment, this study contributes essential evidence for policymakers seeking to mitigate further deterioration and enhance the sustainability of Lebanon’s largest freshwater body.

5. Conclusions

This 25-year Landsat-based investigation provides compelling evidence of the progressive deterioration of Qaraoun Lake’s hydrological regime and environmental quality. The long-term dataset reveals that seasonal depletion is now occurring several months earlier than historical norms, with drought years such as 2015 and 2025 showing minima in mid-summer rather than the traditional autumn drawdown. Such shifts in timing highlight both the reduced contribution of snowmelt inflows from Mount Lebanon and the intensifying pressures of irrigation demand and groundwater extraction in the Bekaa Valley.

Methodologically, the integration of pansharpening proved essential for enhancing spatial resolution, reducing shoreline misclassification by approximately 20%, and thereby improving the accuracy of surface area and volume estimations. This refinement allowed for a more precise reconstruction of seasonal and interannual variability, strengthening the reliability of the time series analysis.

In parallel with volumetric decline, the lake has experienced a marked rise in pollution levels. Spectral indices derived from Landsat imagery, including NDCI, FAI, and SWIR-based turbidity proxies, reveal episodic spikes in chlorophyll, suspended solids, and organic matter. Notably, the years 2005, 2016, and 2024 exhibited daily pollution index values exceeding 1.0, indicating acute contamination events likely linked to untreated sewage, agricultural runoff, and reduced dilution capacity. The average annual pollution index rose from 0.0028 in 2000 to 0.2465 in 2024, underscoring a trend of worsening water quality that parallels hydrological stress.

Together, these findings underscore Lebanon’s escalating water crisis. Declining snow cover, recurrent droughts, unsustainable withdrawals, and rising pollution are converging to compromise agricultural productivity, hydropower generation, and domestic supply. These results align with broader regional studies documenting snowpack decline, reservoir stress, and eutrophication across the Levant and Middle East, situating Qaraoun Lake within a wider pattern of climate-driven vulnerability.

Addressing these challenges requires urgent action: integrated water resource management, improved irrigation efficiency, pollution mitigation strategies, and the adoption of climate adaptation measures tailored to Lebanon’s semi-arid conditions. Long-term satellite monitoring, combined with updated bathymetric surveys and ground-based water quality assessments, will be indispensable for tracking future changes and guiding policy interventions.

Future work should prioritize:

- -

- Establishing a continuous monitoring program that integrates satellite observations (including Sentinel-2) with in situ water quality measurements.

- -

- Updating bathymetric surveys to refine volume estimations and improve hydrological modeling.

- -

- Developing predictive models that couple climate scenarios with reservoir dynamics to anticipate future stressors.

- -

- Expanding the use of cloud-based platforms (e.g., Google Earth Engine) for regional-scale water monitoring to ensure reproducibility and scalability.

Policy interventions should focus on:

- -

- Enforce stricter regulations on wastewater discharge and agricultural runoff to reduce nutrient loading.

- -

- Promoting water-saving irrigation technologies and groundwater management policies in the Bekaa Valley.

- -

- Implementing watershed-scale pollution mitigation strategies that integrate upstream land-use planning with downstream reservoir protection.

- -

- Strengthening institutional collaboration between the Litani River Authority, municipalities, and research institutions to ensure transparent data sharing and evidence-based decision-making.

Ultimately, Qaraoun Lake serves as both a sentinel and a warning. Its trajectory reflects the broader fragility of Lebanon’s water systems under the combined weight of climate variability, anthropogenic demand, and environmental degradation. By coupling scientific monitoring with proactive policy measures, Lebanon can better safeguard its freshwater resources and enhance resilience to future climate stressors.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available at https://ieee-dataport.org/ (accessed on 22 December 2025); Repository: https://ieee-dataport.org/documents/qaraoun-lake-lebanon-multi-decadal-dataset-hydrology-and-water-quality (accessed on 22 December 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Woolway, R.I.; Sharma, S.; Smol, J.P. Lakes in hot water: The impacts of a changing climate on aquatic ecosystems. BioScience 2022, 72, 1050–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraemer, B.M.; Woolway, R.I.; Lenters, J.D.; Merchant, C.J.; O’Reilly, C.M.; Sharma, S. Global lake responses to climate change. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 388–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutanda, G.W.; Nhamo, G. Impact of climate change on Africa’s major lakes: A systematic review incorporating pathways of enhancing climate resilience. Front. Water 2024, 6, 1443989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abalasei, M.E.; Toma, D.; Dorus, M.; Teodosiu, C. The impact of climate change on water quality: A critical analysis. Water 2023, 17, 3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shang, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, W.; Niu, L.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H. The role of freshwater eutrophication in greenhouse gas emissions: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 768, 144582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadel, A.; Slim, K. Evaluation of the Physicochemical and Environmental Status of Qaraaoun Reservoir. In The Litani River, Lebanon: An Assessment and Current Challenges; Water Science and Technology Library; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Volume 85, Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-76300-2_5 (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Mishra, S.; Mishra, D.R. Normalized difference chlorophyll index: A novel model for remote estimation of chlorophyll a concentration in turbid productive waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 117, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C. A novel ocean color index to detect floating algae in the global oceans. Remote Sens. Environ. 2009, 113, 2118–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharaf, N.; Fadel, A.; Bresciani, M.; Giardino, C.; Lemaire, B.J.; Slim, K.; Faour, G. Using Landsat and in situ data to map turbidity as a proxy of cyanobacteria in a hypereutrophic Mediterranean reservoir. Ecol. Inform. 2019, 50, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadel, A.; Faour, G.; Halawi Ghosn, R.; Slim, K. The potential of different reflectance-based algorithms to retrieve phycocyanin concentration through remote sensing: Application in a hypereutrophic Mediterranean lake. Environ. Sci. Proc. 2024, 29, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, M. Google Earth Engine (GEE) Cloud Computing-Based Crop Classification Using Radar, Optical Images, and the Support Vector Machine Algorithm (SVM); IEEE IMCET: Beirut, Lebanon, 2021; pp. 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 202, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, L.; Mutanga, O. Google Earth Engine Applications Since Inception: Usage, Trends, and Potential. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia. Assessment of the Litani River Basin. 2016. Available online: https://www.unescwa.org/publications/assessment-litani-river-basin (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Yazbek, A.; El-Fadel, M. Water quality assessment of Qaraoun Lake using multivariate statistical techniques. J. Environ. Hydrol. 2019, 27, 1–12. Available online: http://www.hydroweb.com/protect/pubs/jeh/jeh2019/yazbek.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Korfali, S.I.; Jurdi, M. Speciation of metals in bed sediments and water of Qaraoun Reservoir, Lebanon. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2010, 178, 563–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council for Development and Reconstruction. Lake Qaraoun Pollution Prevention Project. 2023. Available online: https://www.cdr.gov.lb/en-US/Studies-and-reports/Lake-Qaraoun-Pollution-Prevention.aspx (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- United Nations Development Program; Litani River Authority. Hydrological and Isotope Study of the Upper Litani Basin. 2014. Available online: https://www.lb.undp.org (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Society for the Protection of Nature in Lebanon. Lake Qaraoun: Important Bird Area. 2020. Available online: https://www.spnl.org/lake-qaraoun/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Wang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, T.; Wang, G.; He, G.; Zhang, Z. An Efficient Framework for Producing Landsat-Based Land Surface Temperature Data Using Google Earth Engine. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2020, 13, 4689–4701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.P.; Wulder, M.A.; Loveland, T.R.; Woodcock, C.E.; Allen, R.G.; Anderson, M.C.; Zhu, Z. Landsat-8: Science and product vision for terrestrial global change research. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 145, 154–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masek, J.G.; Vermote, E.F.; Saleous, N.; Wolfe, R.; Hall, F.G.; Huemmrich, F.; Gao, F.; Kutler, J.; Lim, T.K. LEDAPS Calibration, Reflectance, Atmospheric Correction Preprocessing Code, 2nd ed.; ORNL DAAC: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Vermote, E.; Justice, C.; Claverie, M.; Franch, B. Preliminary analysis of the performance of the Landsat 8/OLI land surface reflectance product. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 185, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Woodcock, C.E. Object-based cloud and cloud shadow detection in Landsat imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 118, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laben, C.A.; Brower, B.V. Process for Enhancing the Spatial Resolution of Multispectral Imagery Using Pan-Sharpening. U.S. Patent 6,011,875, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H. Modification of the normalised difference water index (NDWI) to enhance open water features in remotely sensed imagery. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2006, 27, 3025–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colkesen, I.; Ozturk, M.Y.; Altuntas, O.Y. Comparative evaluation of performances of algae indices, pixel- and object-based machine learning algorithms in mapping floating algal blooms using Sentinel-2 imagery. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2024, 38, 1613–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyisa, G.L.; Meilby, H.; Fensholt, R.; Proud, S.R. Automated water extraction index: A new technique for surface water mapping using Landsat imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 140, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Fadel, M.; Bou-Zeid, E.R. Climate change and water resources in the Middle East: Vulnerability, socio-economic impacts and adaptation. In Climate Change in the Mediterranean: Socio-Economic Perspectives of Impacts, Vulnerability and Adaptation; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2003; pp. 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, A.N.; Hunter, P.D.; Spyrakos, E.; Groom, S.; Constantinescu, E.; Kitchen, J. Developments in Earth observation for the assessment and monitoring of inland, transitional, coastal, and shelf-sea waters. Sci. Total Environ. 2006, 572, 1307–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gholizadeh, M.H.; Melesse, A.M.; Reddi, L. A comprehensive review of water quality parameter estimation using remote sensing techniques. Sensors 2016, 16, 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, K.; Choudhary, B.; Fitzsimmons, K.E. Predicting and evaluating seasonal water turbidity in Lake Balkhash, Kazakhstan, using remote sensing and GIS. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1371759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barhoumi, W.; Fadel, A.; Slim, K.; Lemaire, B.J.; Vinçon-Leite, B.; Sharaf, N. Evaluation of water quality of the Qaraoun Reservoir, Lebanon: Suitability for multipurpose usage. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 13745–13760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Project Appraisal Document: Lake Qaraoun Pollution Prevention Project (Report No. PAD1783). 2016. Available online: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/279341468589482380 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Haydar, C.M.; Nehme, N.; Villeras, F.; Hamieh, T. Water quality of the Upper Litani River Basin, Lebanon. Phys. Procedia 2014, 55, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatib, M.; Kahil, M.; Soliman, M. Restoration of Qaraoun Lake aquatic life based on wetland treatment concept. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Lake Qaraoun Pollution Prevention Project; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; Available online: https://waterhq.world/issue-sections/country-reports/lebanon/world-bank-finances-project-to-tackle-pollution-of-lake-qaraoun/ (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Litani River Authority. Annual Report 2014; Litani River Authority: Zahle, Lebanon, 2014. Available online: https://www.litani.gov.lb/en-us/aboutlra/yearlyreport (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Litani River Authority. Annual Report 2016; Litani River Authority: Zahle, Lebanon, 2016. Available online: https://www.litani.gov.lb/en-us/aboutlra/yearlyreport (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Council for Development and Reconstruction. Lake Qaraoun Pollution Prevention Project: Semestrial Report, July–December 2021; CDR: Beirut, Lebanon, 2021. Available online: https://cdr.gov.lb/getmedia/b9c50d77-eabc-41a6-8a1a-5cc0be6159dd/LQPPP-Semestrial-Report-July-December-2021.pdf.aspx (accessed on 5 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.