Abstract

This study investigates how centralized governance structures undermine the achievement of sustainable development by systematically eliminating local grassroot territorial development vectors and initiatives. It examines how centralization reduces the representation of diverse sustainability strategies as systems transition from local to regional/national level. Using Belarus as a case study, this research discovers the effects of this transition. The study thoroughly explored 47 sustainable development planning documents from Belarus, spanning from 2005 to 2020, and encompassing diverse levels of governance, including Local Agenda 21 plans, municipal strategies, and regional planning documents. The SWOT indicators extracted during the analysis were systematically categorized within the advanced sustainability framework into the following four categories: social, environmental, economic, and institutional/participatory. A quantitative analysis of local development vectors loss was conducted using a novel evaluation tool designed to measure indicator diversity across various planning scales. The findings show that approximately 85% of the diversity of local sustainability vectors is lost due to aggregation/in hierarchical planning processes. This phenomenon can be explained by reference to three mechanisms: administrative inertia (institutional resistance to novel approaches), funding constraints (central budgets default to standardized territorial development vectors), and structural barriers (limited local autonomy despite formal decentralization policies). Social and environmental development vectors demonstrate greater losses than economic ones, indicating that context-specific local solutions are systematically ignored at higher scales. The results indicate that the formal decentralization approach is ineffective in preserving local sustainability without complementary institutional reforms. The study enhances existing knowledge of sustainability science by demonstrating how central governance restricts the implementation of localized solutions to environmental and social challenges. This demonstrates that formal decentralization policies, without institutional reforms, do not lead to sustainable development. The methodology developed here can also be applied to other highly centralized systems.

1. Introduction

The effectiveness of territorial development policies is contingent upon the incorporation of grassroots initiatives into central governments policy frameworks [1,2]. The adoption of decentralization policies within highly centralized administrative systems—particularly in post-Soviet states—frequently fails to lead to meaningful local participation in governance. Significant problems in territorial governance arise from the gap between political aspirations and their implementation. Territorial development vectors (TDVs) (The term ‘territorial development vectors’ refers to areas of activity, methods of using resources, necessary actions for the benefit of the territory, steps to improve the situation and specific wishes and recommendations expressed by representatives of the relevant territorial level (local, regional or national). Variants of this term, such as ‘local development vectors’ (or ‘grassroots development vectors’), ‘regional development vectors’ and ‘national vectors of regional development’, can be used in the appropriate context and situation.), that are proposed at the local level and are often better suited to local needs lose their vitality when they pass through the hierarchical governance, planning and financing structures at different administrative levels, from district to regional and national.

In the contemporary context, achieving spatial sustainability requires integration of environmental, economic, and social factors across multiple governance levels [3,4,5]. Successful sustainable development is contingent upon policy mechanisms that exhibit adaptive responsiveness to evolving social and political contexts [6,7,8] while fostering active citizen participation [9,10]. This suggests that “transformative social innovation requires bottom-up governance” [2], thereby indicating that territorial development vectors are more effective when they emerge from and remain connected to local communities. The implementation of sustainable practices, whether environmental or socio-economic, relies on the integration of local resources and the incorporation of local knowledge [11,12]. However, this integration faces challenges in post-Soviet and Eastern Partnership countries, where centralized administrative structures limit local autonomy despite the presence of formal decentralization policies.

Decentralization has emerged as a prevailing governance principle within the broader development literature. Evidence from highly developed countries demonstrates the effectiveness and necessity of decentralizing public administration and strengthening local self-government systems [13,14]. Experts in public administration report that decentralization increases the efficiency of public services, ensures citizen participation in politics, and enhances transparency and reduces corruption [15,16,17]. In practice, decentralization has been implemented in approximately 80% of developing and transition economies, reflecting a broad consensus on its benefits [18,19,20]. Despite this, most research in this area focuses on contexts where decentralization is institutionally embedded and enjoys political support. The fundamental challenge in post-Soviet contexts, such as Belarus, differs in nature. In these countries, formal decentralization policies coexist alongside centralized implementation structures [21], creating a unique governance configuration that has received limited scholarly attention.

The existence of diverse territorial development strategies and local initiatives reflects communities’ capacity to devise solutions that correspond to their socio-economic and environmental contexts [22,23,24]. The term “local development” underscores the notion that sustainable outcomes are contingent on decisions and actions at local scales, acknowledging the distinct characteristics of different regions [25,26]. Local development approaches yield more effective and contextually appropriate solutions than standardized national policies [27]. The 2002 UNESCO World Summit on Sustainable Development acknowledged that respecting and integrating natural and cultural diversity is a prerequisite for sustainable development [5,28]. However, a critical gap exists in the field: while the importance of local diversity is widely acknowledged in policy documents [29], systematic analysis of how this diversity is preserved through multi-level governance processes remains limited.

Recent research on rural development and local governance has revealed a consistent pattern: when moving from local strategic sessions and plans to regional (within countries) and national ones, the diversity of territorial development vectors is significantly lost. Although qualitative case studies have documented this phenomenon [30], systematic quantitative assessments of the scale of reduction (or loss) of diversity (i.e., the number of different territorial vectors of development) during the transition from local-level to regional- and national-level planning, financing and task implementation are rarely considered. This gap highlights the need for robust, multidimensional measurement frameworks capable of capturing development dynamics across territorial levels and moving beyond aggregate macro-level indicators, which often obscure locally articulated development patterns and priorities [31]. The macro-level analysis that predominates in spatial development research frequently fails to incorporate “the complicated and specific insights arising at the grassroots level” [32]. This oversight is particularly significant given the substantial variability in local knowledge and the unique socio-economic contexts of communities at different scales [33,34]. Furthermore, the persistent challenge of balancing local and central governance in territorial planning persists as a “pivotal concern” [35]. However, the specific mechanisms through which centralization constrains local initiatives remain underdeveloped.

Participation research has been demonstrated to reveal significant patterns relevant to understanding initiative loss. The degree of trust in government varies significantly across administrative levels, with trust declining from local to national levels [36,37]. Public participation is frequently characterized as “a means of expressing opinion during formal proceedings rather than an opportunity to acquire the knowledge needed for planning purposes” [38]. Empirical research on policy feedback further shows that citizens’ real-life interactions with public institutions—such as experiences of being granted or denied social benefits—significantly shape their propensity for political engagement and protest, indicating that formal participation mechanisms alone are insufficient to ensure meaningful influence on policy outcomes [39]. In centralized systems of country administration, local authorities are often stuck between community needs and pressures from above, giving higher-level directives priority over local preferences. This dynamic creates perverse incentives in which unique grassroots solutions are “risked being lost or ignored” but not being integrated into larger-scale policies, strategies, plans and projects [40].

Recent advances in multi-level governance research emphasize the complexity of interactions between nested decision-making arenas and the selective retention of locally articulated priorities, pointing to structural inconsistencies in aligning lower- and higher-tier sustainability strategies. Recent multi-level governance scholarship highlights how governance structures and institutional processes shape the translation of place-based strategies across scales, with implications for the retention or loss of locally defined development concerns [41,42]. Moreover, frameworks for a territorial approach to the Sustainable Development Goals underscore the role of contextualized data and place-based indicators in capturing diverse sustainability vectors, and the challenges of maintaining such diversity through multi-level policy processes [43]. Empirical analyses of multi-level policy implementation in specific domains such as biodiversity governance further attest that policy outcomes vary significantly depending on subnational governance arrangements, confirming that selective filtering of priorities at higher levels may systematically marginalize certain development concerns [44].

The post-Soviet context presents a particular governance configuration relevant to understanding initiative loss. Despite adopting formal decentralization policies, many post-Soviet and Eastern Partnership countries retain highly centralized governance structures with limited local autonomy [45,46]. Contrary to the Western European critique of decentralization, which emphasizes the neoliberal consequences and market-driven governance, the governance challenge in post-Soviet contexts is distinct in its fundamental nature. The creation of meaningful mechanisms for local ownership of governance structures and the assurance that local participation translates into actual policy influence are paramount [47,48]. This distinction indicates that understanding initiative loss in post-Soviet contexts necessitates specific analysis rather than the application of Western European frameworks. While some comparative research has examined decentralization in EaP countries [49], Belarus presents a particularly instructive case. Although the country has implemented formal decentralization policies, including three successive national sustainable development strategies [50,51], these policies have been implemented centrally, revealing a contradiction between policy and practice.

Although extant research demonstrates the benefits of decentralization and local participation in sustainable development, few studies provide systematic quantitative evidence of how many grassroots development vectors and initiatives are lost as they move through hierarchical governance structures. Furthermore, extant studies do not explain the specific mechanisms through which this loss occurs in centralized post-Soviet systems.

This study addresses this gap by investigating the mechanisms through which centralization limits the diversity and impact of grassroots sustainable development vectors and initiatives in Belarus, a post-Soviet state with formal decentralization objectives but limited implementation. By examining how and why local development vectors are systematically excluded from higher-level policy processes, this research contributes to understanding governance effectiveness in territorial development planning.

This study addresses two interconnected research questions: (i) How do grassroots sustainable development vectors decline as they move from local to national governance levels? Specifically, what proportion of local-level development vectors successfully influence higher-level planning? (ii) What mechanisms account for this decline? Through what processes do centralized governance structures systematically eliminate local initiative diversity? To address these questions, the study: (a) quantifies initiative attrition across governance levels using a novel mathematical model based on SWOT indicator analysis, measuring how initiative diversity of local development vectors declines as planning aggregates from local to regional levels; (b) identifies mechanisms of vectors loss through document analysis and theoretical framework development, explaining why and how initiative diversity is systematically reduced; (c) proposes a replicable methodology applicable to other post-Soviet and Eastern Partnership countries for assessing governance effectiveness and identifying intervention points for strengthening subsidiarity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Framework: Loss of Territorial Development Vectors in Centralized Systems

Institutional theory posits that governance structures exert a profound influence on behavioral patterns and outcomes [52]. In centralized systems, hierarchical institutions establish formal rules and informal norms that systematically favor higher-level decisions over local innovations. Within the framework of institutional theory, path dependency suggests that organizational entities tend to perpetuate established structures, even in scenarios when alternative approaches may yield superior outcomes. The consolidation of authority in centralized bureaucracies fosters a top-down decision-making paradigm, thereby impeding the adoption of diverse local development vectors and initiatives that have the potential to disrupt established hierarchies.

Principal-agent theory postulates that information asymmetries between central and local authorities compromise the survival of development vectors and initiatives [53]. Central governments often lack sufficient understanding of local contexts, compelling them to implement standardized policies that are applicable across various jurisdictions. Conversely, grassroots development vectors and initiatives are typically context-specific and exhibit substantial heterogeneity. When local agents attempt to advance their proposals to higher governance levels, information asymmetries generate misalignment: central governments (the principals) are unable to readily evaluate whether diverse grassroot development vectors (developed by local agents) merit support. As a result, centralized systems tend to prioritize predictable, standardized solutions, potentially at the expense of local diversity.

Subsidiarity, defined as the principle that decisions should be made at the lowest appropriate governance level, provides a normative framework for assessing governance effectiveness [13]. Within subsidiarity frameworks, the question is not whether local-level information should be incorporated into higher-level planning—it should be—but rather: (1) are local inputs systematically collected and evaluated before being excluded? (2) are filtering decisions guided by transparent criteria? and (3) do filtering mechanisms preserve concerns that are relevant at multiple scales (e.g., environmental degradation affecting both local and regional sustainability). However, subsidiarity requires both decision-making authority and autonomy at the local level. In systems that combine subsidiarity with central budget authority, local governments may lack resources necessary to implement locally determined priorities. This creates perverse incentives in which local officials prioritize alignment with higher authorities over local needs.

The present study conceptualizes the loss of local development vectors and initiatives as a process of aggregation occurring at each transition between governance levels. At each point in the decision-making process, certain local concerns are incorporated into higher-level documents, while others are excluded. This phenomenon, while not inherently problematic or undesirable, underscores the significance of aggregation in hierarchical governance structures. However, the legitimacy of aggregation can be ascertained through the evaluation of three criteria. Firstly, the procedures through which filtering occurs must be assessed. Secondly, it is essential to determine whether decisions are informed by systematic evaluation of local input rather than arbitrary decisions. Thirdly, decisions must be examined to ascertain whether they reflect scale-appropriate distinctions (i.e., are local concerns excluded because they are genuinely irrelevant at higher scales, or because of biases, budget constraints, or information problems?).

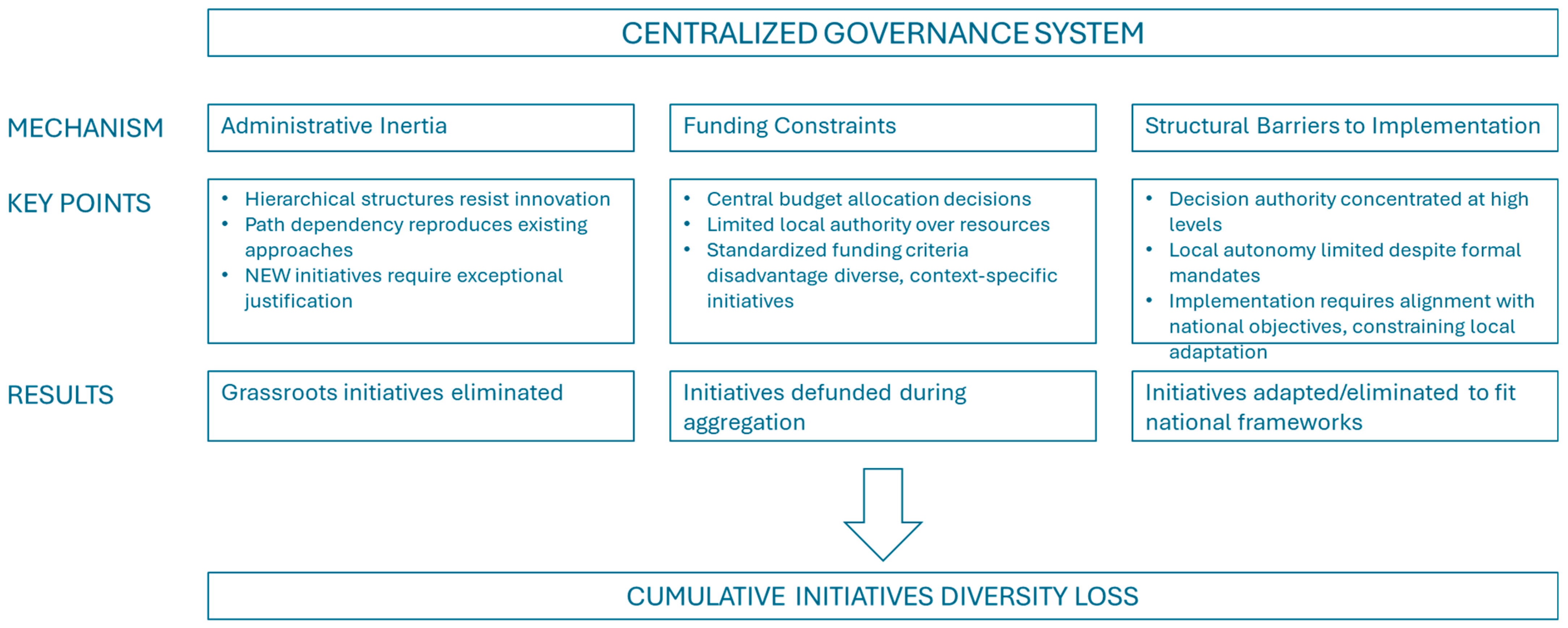

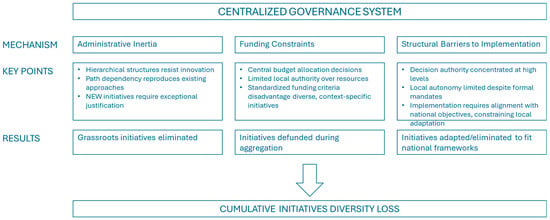

The present study hypothesizes three interconnected mechanisms through which centralization may cause loss of local development vectors, drawing on institutional theory, principal-agent analysis, and subsidiarity concepts (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Three mechanisms of loss of local development vectors and initiatives. Source: Own Study.

Mechanism 1—Administrative inertia. Bureaucracies develop procedures and invest in legitimacy within hierarchies. Grassroots initiatives disrupt routines and threaten authority. Administrative inertia causes systems to resist new approaches, creating veto points at each governance level where proponents must justify innovations against established procedures. Consequently, most local development vectors and initiatives fail.

Mechanism 2—Funding constraints and information problems. Centralized budgeting creates information asymmetries and makes it difficult to assess the value and costs of diverse, context-specific local development vectors and initiatives. This results in standardized funding criteria favoring replicable solutions. Grassroots development vectors often do not meet these criteria and lose funding during aggregation.

Mechanism 3—Structural barriers to implementation. Local development vectors and initiatives that make it to higher governance levels face implementation barriers. Local autonomy is limited despite formal authority, so implementations must align with national objectives. This constraint forces adaptation or elimination of features that made grassroot development vectors locally effective, rendering them unrecognizable or ineffective on a scale. As a result, communities lose incentives to support development vectors and initiatives that have been transformed into standardized national programs.

2.2. Research Approach and Data Sources

General approach. This study employs a mixed-methods approach that combines quantitative analysis of strategic planning documents with qualitative assessment of governance structures in Belarus. The research design responds to the need for systematic quantification of initiative loss across governance levels, moving beyond traditional qualitative case studies to provide reproducible, evidence-based measurement of how grassroots initiatives decline through aggregation processes. The study is structured around two complementary research components: (1) quantitative measurement of initiative loss using a novel mathematical model based on SWOT indicator analysis, and (2) qualitative analysis of governance mechanisms explaining why this loss occurs.

Indicator categorization. Diversity of local development vectors is operationalized as the variety of distinct SWOT indicators appearing in strategic planning documents. SWOT analysis captures how communities and planners conceptualize local development challenges and opportunities. The utilization of SWOT indicators counts as a proxy measure facilitates the assessment of the diversity of concerns and priorities that communities and local planners are addressing. The diversity of SWOT items at each governance level reflects the diversity of local development vectors, initiatives and approaches being considered. While SWOT indicators do not represent completed initiatives or programs, they document the range of development concerns and priorities that communities have identified as important. This observation serves as a valid proxy for initiative diversity, as the range of documented concerns generally correlates with the range of actual initiatives being implemented. Each SWOT statement is extracted from documents and coded for content. The SWOT items were then assigned to four analytical categories. Within each category, items were counted as separate indicators reflecting separate development vectors. Social (Soc) category includes indicators addressing social cohesion, quality of life, community engagement, education, and health. Environmental (Env) category considers indicators addressing environmental conditions, natural resource management, and sustainability. Economic (Econ) category comprises indicators addressing economic development, employment, business environment, and infrastructure. Institutional/Participatory (IP) category covers indicators addressing governance, participation mechanisms, and institutional capacity.

This operationalization measures the diversity of documented concerns at each governance level, not the number of actual development vectors completed. We interpret variations in SWOT diversity across levels as indicative of disparities in the incorporation of distinct local-level concerns into planning at higher scales. The following arguments support this assumption: Firstly, the diversity of documented concerns corresponds to the diversity of actual development vectors. Secondly, planning documents that narrow the range of addressed concerns tend to pursue fewer, more standardized development vectors. Thirdly, this approach enables the quantification of a phenomenon that would otherwise be difficult to measure systematically.

Data sources. This study analyzes 47 sustainable development strategy documents and related planning instruments covering the period 2005–2020. The dataset includes: 20 comprehensive Local Agenda 21 (LA21) plans at various governance levels; 15 municipal and local development strategies; 10 district-level strategic documents; and 2 regional sustainable development strategies. Primary data sources were identified through systematic review of official Belarusian government archives and environmental policy repositories; contact with district and municipal administrations across six oblasts (regions); archival records maintained by Information Centers on Sustainable Development.

2.3. Case Study

Belarus, as a post-Soviet state, has formally adopted decentralization policies that call for subsidiarity and local autonomy.

The initial Belarusian Strategy of Sustainable Development (2000–2015) expressly stipulated that “the capabilities and initiatives of local public administration and self-government bodies, as well as citizens and residents of the pertinent regions, should serve as the foundation for the national strategy for the sustainable development of Belarus” [54]. The National Strategy for Sustainable Development up to 2020 (NSSD-2020) placed particular emphasis on the expansion of local self-government powers, financial capacities, and responsibilities [55]. The most recent National Strategy for Sustainable Socio-Economic Development until 2030 (NSSD-2030) aims to transfer functions and responsibilities from higher to local authorities by 2030 [56]. These three successive strategies demonstrate a formal policy shift toward decentralization and subsidiarity. This configuration—formal (but not real, i.e., essentially decorative) decentralization policies combined with continued centralized control over budgets and strategic priorities—makes Belarus an exemplary case for examining the factors that contribute to the dissolution of initiatives despite the presence of favorable policy rhetoric.

Despite the implementation of formal decentralization policies, Belarus continues to exhibit a pronounced degree of centralization in its administrative structure, which is referred to as the “presidential vertical”. This refers to the concentration of decision-making authority and budget allocation at the national and regional levels. Local units exercise limited autonomy in practice. This discrepancy between formal authority and actual decision-making power engenders conditions conducive to the observation of initiative loss, which would be obscured in either purely centralized or genuinely decentralized systems. Belarus presents a unique governance configuration: formal decentralization policies coexist with centralized implementation through presidential vertical structures. This paradox is not accidental but reflects competing pressures: (1) international commitments to subsidiarity and local participation (required for EU integration, international environmental agreements, SDG implementation), versus (2) domestic political interests in centralized control. This has resulted in the promotion of decentralization without the subsequent realization of local autonomy. This specific configuration offers a unique opportunity to examine the phenomenon of initiative loss, even in contexts where formal policies are in place to support local engagement.

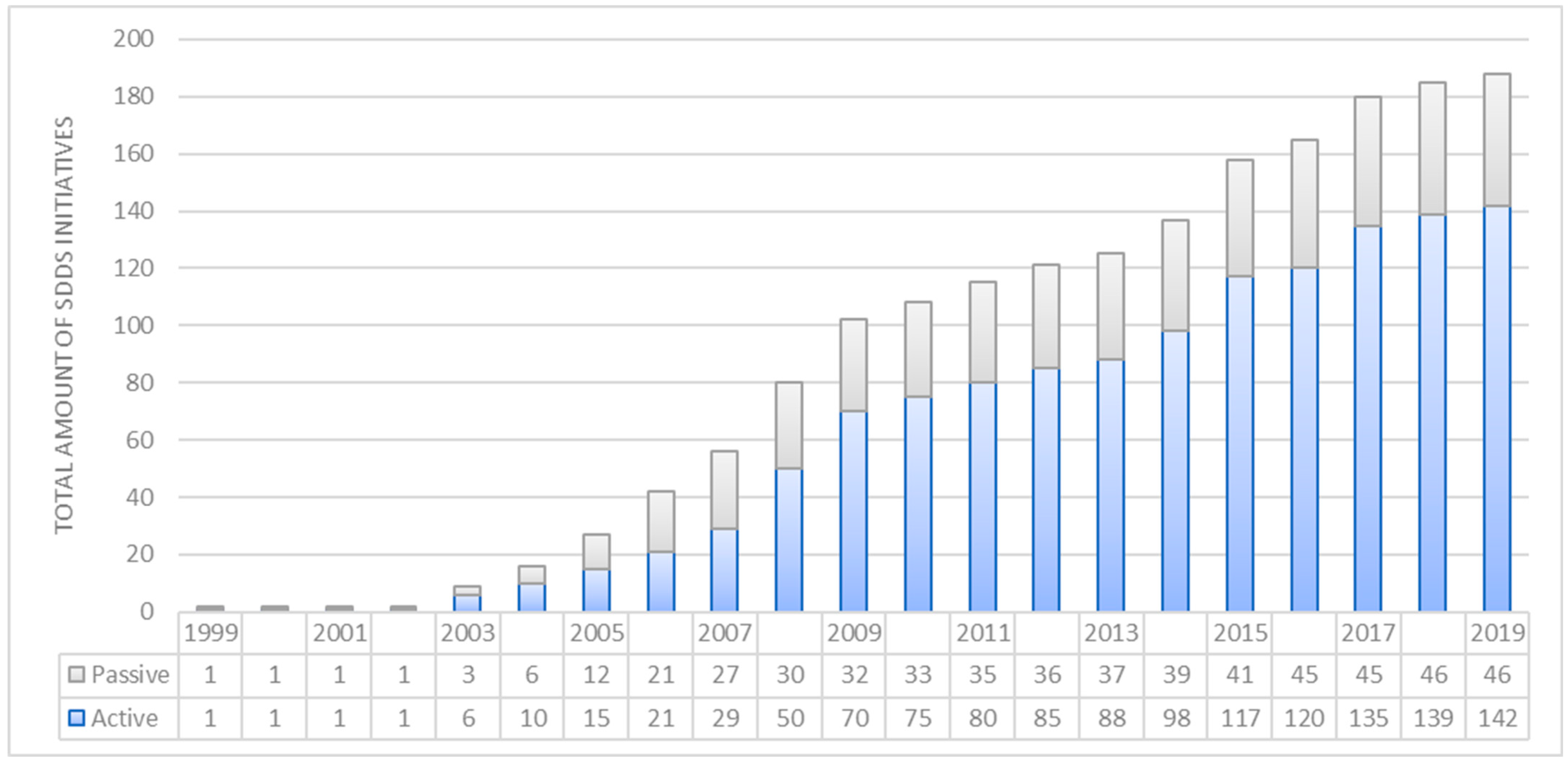

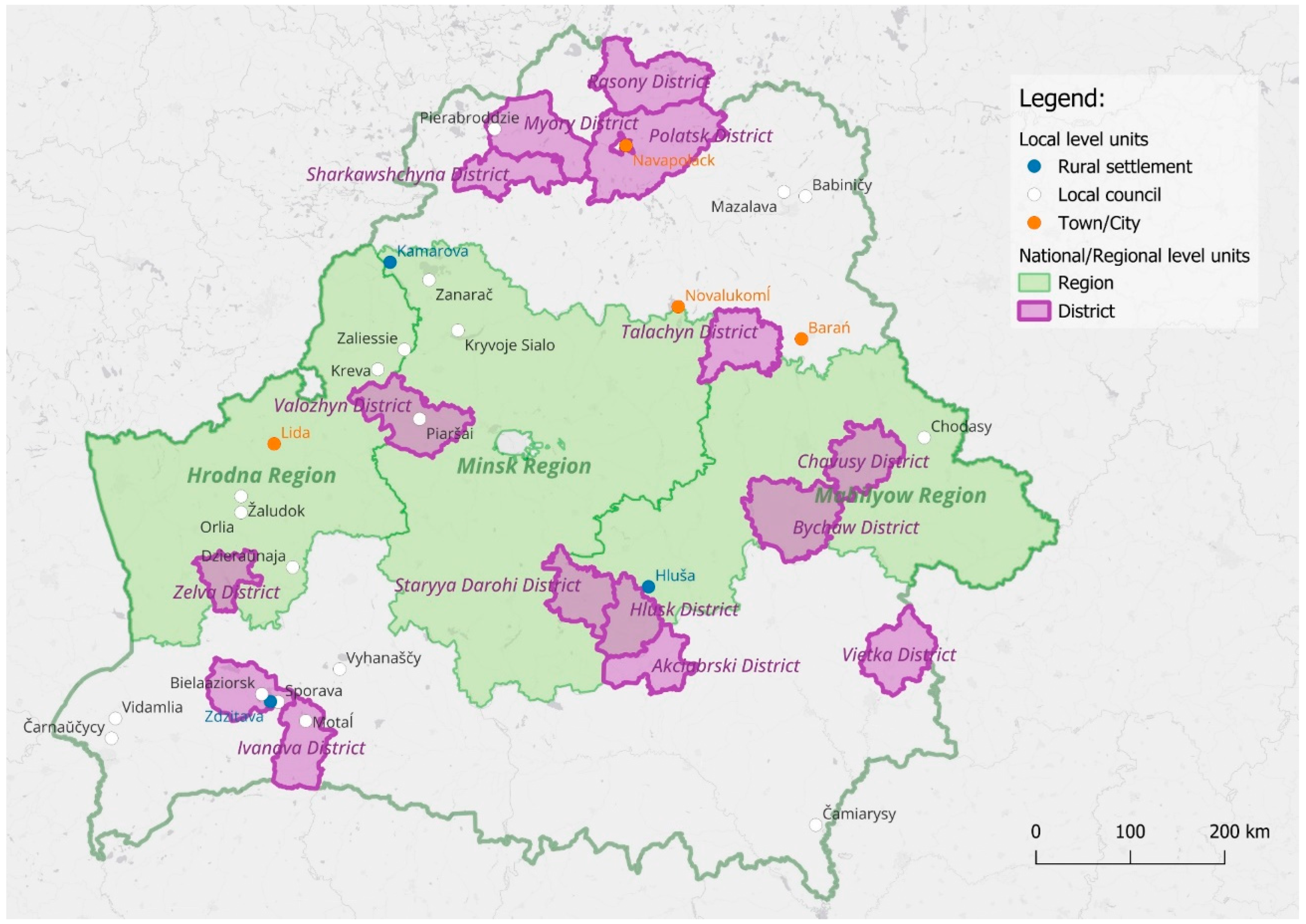

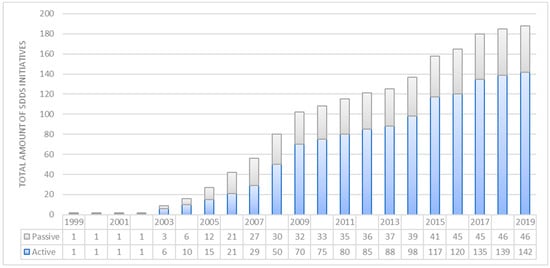

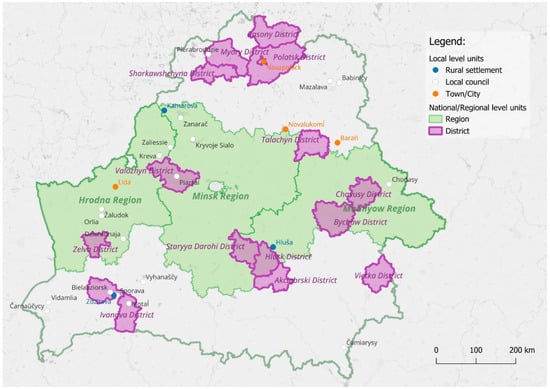

From 1999 to 2020, approximately 200 sustainable development initiatives and programs were established at various governance levels in Belarus. Documentation pertaining to these initiatives is available through Local Agenda 21 processes and strategic development planning documents, where the development concerns and priorities underlying these development vectors are captured in SWOT analyses. As of 2020, approximately 140 of these initiatives remained active, distributed across six oblasts (regions), 20 districts, 50 municipalities, 5 institutions, and approximately 60 educational establishments (Figure 2 and Figure 3). This dataset provides rare systematic documentation of development vectors and initiatives at multiple governance levels over an extended period, enabling quantitative analysis of how initiatives and the concerns they address are represented across governance levels.

Figure 2.

Changes in the total number of initiatives to develop the SSTD in Belarus. Source: Own Study.

Figure 3.

Map of the Republic of Belarus indicating the territorial units selected for the analyses within the current study. Source: Own study using names of entities in the Belarusian Latin alphabet from [57].

The period between 2005 and 2020 encompasses both governance stability and reform efforts, as evidenced by the adoption of successive national strategies. The first systematic Local Agenda 21 process began in 2005, establishing baseline documentation of local concerns. From 2010 to 2015, NSSD-2020 was implemented, and administrative reforms modified governance structures. From 2017 to 2020, the NSSD-2030 was adopted and implemented alongside new strategic initiatives. A notable strength of the study is the comprehensive documentation of SWOT analyses at all governance levels—village, local council, district, and regional—which facilitates both longitudinal observation and systematic cross-level comparison. The quantitative foundation necessary for this analysis is provided by the 47 strategic planning documents with SWOT indicators that are currently available.

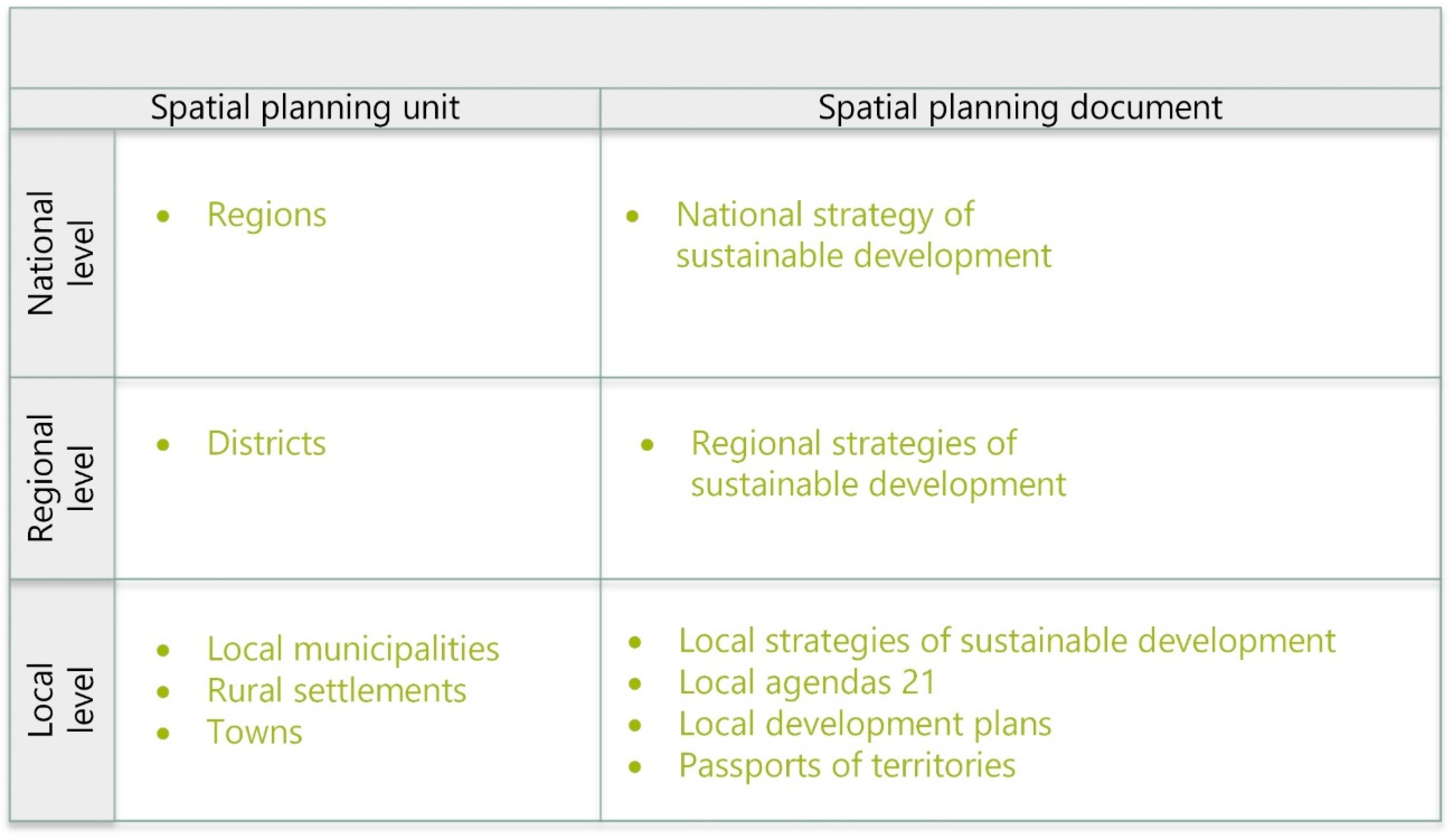

Governance structure and hierarchical levels. The Belarusian residential and administrative system comprises a three-level hierarchical structure that reflects centralized governance organization. This structure is characterized by: (i) hierarchical decision-making authority flowing from higher to lower levels; (ii) resource allocation controlled at regional and national levels; and (iii) limited local autonomy in budgeting and policy implementation despite formal mandates.

Figure 4 illustrates the three-level hierarchical structure with corresponding strategic planning instruments at each level. This hierarchical organization creates multiple aggregation points where initiative diversity is systematically reduced as planning processes move upward through administrative levels.

Figure 4.

Three-level structure of the Belarusian spatial planning system. Source: Own Study.

Level 3 (Regional). Six oblasts (regions) plus Minsk city serve as the primary administrative divisions. These regions coordinate development vectors and initiatives, allocate resources, and implement national policies. Key regional-level planning instruments include Regional Strategies of Sustainable Development.

Level 2 (District). Within each region, districts represent smaller administrative units typically comprising several municipalities, towns, and rural areas. Districts implement regional policies, provide public services, and manage intermediate-level resources. District-level instruments include District Development Strategies and District-level SWOT analyses.

Level 1 (Local). The local administrative level includes cities, towns, villages, rural settlements, and local councils (municipalities). These units constitute the centers of community life and local administration. Local-level instruments include Local Agendas 21 (LA21); Local Strategies of Sustainable Development (LSSD); Local Development Plans; and Territory Passports (Community profiles).

Level 0 (Village/Settlement or their parts). Grassroot level. While not formally recognized as a separate administrative tier in organizational terms, individual villages and settlements generate their own SWOT analyses and development priorities that feed into local council-level planning.

2.4. Mathematical Model for Measuring Initiative Loss

Conventional qualitative approaches document the success or failure of initiatives; however, they are unable to systematically quantify how the diversity of changes as aggregation processes move planning from local to higher levels. The present study develops a novel ratio-based loss-measuring method, with SWOT indicator counts serving as a measure of the range of distinct being documented and considered at each level. The underlying assumption is that the diversity of developmental concerns reflected in SWOT analyses corresponds with the diversity of distinct grassroots development vectors and priorities being considered in planning at that governance level. Governance levels that incorporate a more varied array of SWOT indicators demonstrate an increased capacity to address a more diverse set of local development concerns [58]. As the diversity of SWOT indicators exhibits a downward trend across various governance levels, it can be interpreted that certain local concerns are not being adequately incorporated into higher-level planning processes. While not all documented SWOT concerns correspond to specific programs and initiatives, the range of documented concerns generally correlates with the range of distinct development vectors being pursued, thereby validating SWOT heterogeneity as a proxy for diversity of local development vectors.

Initiative capacity loss Lij for i-unit at j-level is calculated by Equation (1). This ratio is indicative of the variation in the median indicator counts for each unit type changes across governance levels. A ratio > 1 indicates aggregation/loss; a ratio < 1 indicates diversification.

where

aij is the median value of the i-unit quantity (number of distinct SWOT indicators) at the j-level;

kij is the etalon (reference) value of the SWOT indicators for the i-unit at the j-level, defined as the median count of SWOT items documented at that governance level.

The ratio Lij therefore indicates the median count of distinct concerns’ change as planning progresses from one level to the next. The etalon value serves as a standardized reference point for comparison. In this study, the median count of SWOT indicators at each governance level is utilized as the standard value. The underlying rationale supporting this choice is as follows: (i) it represents a typical governance unit at that level, avoiding bias from unusual cases; (ii) it is empirically derived from actual data, not theoretical assumptions; and (iii) it allows comparison of how typical units change as planning aggregates. The basic and robust scenarios differ in the etalon references they use: the basic scenario uses median values (typical cases), while the robust scenario uses minimum and maximum values (extreme cases) to demonstrate the potential range of loss across all variations.

To assess robustness, the study considers two scenarios: basic and robust. The basic (conservative) scenario uses median values to estimate typical losses. Robust (comprehensive) scenario identifies losses accounting for all unit sizes and variations from minimum to maximum values at each level. Both scenarios are valuable: the basic scenario shows typical patterns; the robust scenario shows the range of variation and potential extremes. Both indicators suggest the presence of substantial concern filtering, although the basic scenario offers a more conservative estimate.

The basic scenario is a mild assumption of potential losses measured by the index , expressed as the ratio of the minimum value of the lowest-level indicator () to the maximum value of the highest-level indicator (), Equation (2).

The robust scenario is an assumption of eventual losses measured by the index , specified as the ratio of the maximum value of the lowest-level indicator () to the minimum value of the highest-level indicator (), which is defined by Equation (3)

The rationale underlying selecting the ratio-based approach centers on several assumptions. Firstly, the scale-independence of the measure is notable, as it compares proportional rather than absolute losses. Moreover, it accommodates units of varying sizes across different governance levels. Furthermore, it enables comparison across various indicator types. The median-based etalon method is preferred over the mean method because the median is robust to extreme outliers and represents the typical unit.

Calculating the ratio of local development vectors at different levels of government using Equation (1) allows us to quantify the level of initiative loss. This approach allows a more accurate assessment of the impact of centralization on grassroots efforts and provides a reproducible methodology for benchmarking studies in different European contexts.

However, this mathematical model is subject to several limitations, necessitating further consideration. (1) SWOT indicators are documented concerns, not verified initiatives. Some items may represent aspirations rather than actual programs. (2) The presence of a concern in a SWOT analysis does not guarantee it was systematically considered at the next governance level before being excluded. (3) Not all local initiatives are documented in SWOT analyses. Thus, measures are based on documented concerns only. (4) SWOT analyses may reflect planning assumptions rather than actual community priorities. The depth and quality of SWOT processes vary across documents. (5) Different governance levels may use SWOT analyses differently, affecting comparability. These limitations are addressed through a dual scenario approach (basic and robust) and through qualitative analysis of the mechanisms explaining filtering patterns; nevertheless, they require consideration during the interpretation of results.

3. Results and Discussion

The analysis reveals a systematic pattern of initiative attrition across governance levels in Belarus. As planning moves from the local to the regional level, the representation of diverse local development concerns decreases substantially. This section presents three lines of evidence: (1) quantification of aggregate indicator loss across all levels of governance, (2) variation in loss patterns by the vector type, and (3) temporal patterns indicating whether losses increased or decreased between 2005 and 2020.

This research includes an analysis of strategic planning documents at all levels of land-use planning. A total of 47 SWOT cases were analyzed for different types of documents, including sustainability schemes (Local Agendas 21), visions for sustainable development strategies, area-based development datasets, local economic development plans, and sustainable development strategies. The total number of cases analyzed exceeded 40, and the summary information about the entities involved in the study is presented in Table 1. Documents were selected if they contained SWOT analysis components and covered the period 2005–2020. This approach identified approximately 60 potential documents: 47 met inclusion criteria (complete SWOT analysis, readable quality, spanning diverse governance levels). It provides references to the 47 primary documents and 3 national-level policy documents that were utilized in the analysis.

Table 1.

Description and specificities of the entities involved in the study. Source: Own Study.

The transparency of this listing facilitates: (1) verification of the representativeness of our sample, (2) replication of our analysis using original documents, (3) comparative application of the methodology to other post-Soviet contexts, and (4) temporal tracking of the evolution of planning document content and structure over the 2005–2020 period.

The validity of the research results is based on the scientific rigor of the methodology and on comparable values of actual and empirical spatial density at all levels of spatial planning, as illustrated in Table 2. The data presented in Table 3 is a summary of the SWOT data organized by unit type and level. The losses of initiatives were calculated according to Equation (1), and the results for both basic and robust scenarios are presented in Table 4. To facilitate a more profound comprehension of the development vectors, they have been categorized into four groups corresponding to the key issues in sustainable local community development, namely Social (Soc), Environmental (Env), Economic (Econ), and Institutional and Participatory (IP), as shown in Table 2. Table 5 presents the median values of SWOT indicator sets within four analytical categories.

Table 2.

Number of entities contained in the upper spatial planning levels: empirical () and actual (). Source: Own study.

Table 3.

Summary of SWOT data by unit type and level. Source: Own Study.

Table 4.

Loss of initiative at various levels. Source: Own Study.

Table 5.

Median values of SWOT indicator sets within four analytical categories. Source: Own Study.

Table 4 provides the core finding, which is supported by the data. At the local council level (initial aggregation from villages/settlements), the basic scenario indicates a loss of index Ib = 6.7, meaning local councils represent approximately one-seventh of the diversity of indicators presents at the village/settlement level. In the robust scenario, this increases to 53, suggesting potential losses as high as 98% of local diversity when accounting for all variations. At the district level, losses increase further (basic scenario Ib = 3.0, robust scenario Ir = 60.1), indicating that aggregating from local councils to districts reduces represented diversity by another 60–98%. At the regional level, additional aggregation yields moderate losses (basic scenario Ib = 1.8, robust scenario Ir = 18.7), suggesting that by the time development vectors reach regional planning, only 5–6% of original local-level indicator diversity remains represented. Across all governance levels, the cumulative loss ratio exceeds 20:1 in basic scenarios and 1000:1 in robust scenarios.

The robust scenario loss indices signify theoretical maximums that would occur if, at each aggregation point, all variation within the lowest-level unit were compressed into the highest-level unit. While this scenario is improbable in terms of its uniformity across all governance levels, an examination of specific cases reveals that some districts and regions do approach these extremes. The cumulative loss indices in robust scenarios (reaching 1000:1) appear extreme and warrant explicit discussion of whether such values reflect actual governance conditions or indicate methodological artifacts. The subsequent discussion will address the interpretation of 1000:1 loss ratio. The robust scenario calculation uses: (i) maximum indicators count from village/settlement level (67 from Zdzitava); (ii) minimum indicators count from regional level (102 from Hrodna); (iii) across all aggregation stages: 67/24 × 117/21 × (maximum regional)/(minimum regional). The resulting 1000:1 ratio does not mean that literally 999 out of 1000 local concerns are ignored. Rather, it represents a mathematical extreme: the scenario in which the most comprehensive local SWOT analysis aggregates through the least effective district-level filtering into the least diverse regional strategy. The marked disparity between the basic (20:1) and robust (1000:1) scenarios underscores the sensitivity of loss measurement to underlying assumptions concerning indicator distribution and aggregation mechanism efficiency.

The above indicates systematic, substantial erosion of local diversity representation as planning aggregates upward. The aggregation and simplification of data at higher governance levels is not inherently problematic. The synthesis of diverse information is an inherent aspect of higher-level strategies, facilitating the development of coherent territorial planning and resource allocation frameworks. The extant literature on cybernetic spatial planning demonstrates that structured variety reduction can improve planning effectiveness [59,60]. Nevertheless, a fundamental distinction must be posited between:

- Transparent, deliberate aggregation: Systematic procedures entail the evaluation of diverse local development vectors and the aggregation of decisions through transparent criteria, with stakeholder input. Initiatives that have been eliminated are systematically documented, and the rationale behind each decision is meticulously articulated.

- Opaque, ad hoc elimination: Initiative diversity can be lost through administrative procedures, budget constraints, or deliberate filtering without evaluation or stakeholder awareness.

The present study details the second form. The issue is not aggregation itself, but whether its processes are transparent and accountable, and whether they preserve local diversity to achieve territorial sustainability goals.

Table 5 reveals significant variation in the types of initiatives that survive aggregation. Social category: On average, local councils identify 13–20 social strengths and 12–16 social weaknesses. At the regional level, this number remains relatively stable at 28–39 indicators. Because social concerns are broadly shared across communities, they maintain some representation through aggregation. Economic category: A striking contrast appears with economic indicators. At the local level, the average number of economic indicators is three to six per local council and 20 to 25 per region. Regions disproportionately emphasize economic factors, suggesting that local social and environmental concerns are systematically replaced by economic priorities in higher-level planning. Environmental category: Environmental concerns are modestly represented across levels (0–5 per unit) with minimal variation. Few environmental issues receive explicit attention at any level, indicating local gaps in environmental planning and limited scaling of environmental initiatives. Institutional/Participatory category: There is a decline from the local level (3–5 per council) to the regional level (4–7 per region), indicating that questions of participation and institutional capacity receive minimal attention throughout the hierarchy.

The aggregation of data can result in the disproportionate loss of environmental and institutional indicators due to the tendency of such processes to favor quantifiable metrics that are easily comparable. Economic indicators, such as employment and business registrations, can be measured with ease across all jurisdictions by utilizing standardized national statistics. The assessment of environmental indicators necessitates specialized measurement techniques, including parameters such as water quality and soil health, which exhibit variations in response to local contexts [61]. The inherent challenges in quantifying and standardizing institutional indicators, such as participation quality and local autonomy, underscore the complexity of this endeavor. Moreover, as development vectors focused on capacity-building within environmental and institutional contexts often possess longer implementation horizons when compared with economic programs, this factor should be duly considered. Economic initiatives may demonstrate results in 2–3 years, while environmental restoration or institutional strengthening may require 5–10 years. Environmental/IP indicators may be deprioritized due to shorter planning and electoral cycles.

The observed shift toward economic indicators in higher-level planning raises a fundamental governance question: whether the filtering process reflects legitimate territorial-scale prioritization or represents a democratic deficit. In systems that are genuinely decentralized and democratic (e.g., federal Germany), local priorities have the capacity to influence higher-level plans to a substantial degree. This influence is not achieved through mechanical aggregation, but rather through electoral and institutional mechanisms. Local stakeholders, recognizing the pivotal role of social concerns in shaping electoral outcomes, play a crucial part in influencing politicians who subsequently advocate for these issues at the regional and national levels. These politicians, in turn, are obligated to consider geographic voting patterns that reflect the priorities of the local communities. Consequently, regional and national strategies in democratic systems reflect the diversity of local concerns to a certain extent, with filtering and modification, because ignoring entire categories of local priorities creates electoral costs.

The governance configuration of Belarus is characterized by an absence of democratic feedback mechanisms. Local communities engage in participatory planning processes (Local Agenda 21) to identify concerns; however, elected bodies within these communities possess limited authority to ensure that higher-level strategies align with these concerns. The appointment of regional administrators, as opposed to their election, signifies a transfer of legitimacy from local constituencies to the national government. Therefore, the systematic exclusion of social and environmental indicators from regional strategies does not result in any electoral consequences. Conversely, the maintenance of standardized economic metrics does not incur any costs for regional administrators seeking to demonstrate alignment with national priorities.

The paper does not posit that higher-level plans must be mechanical aggregations of lower-level plans. However, the argument is made that the inevitable filtration process ought to uphold procedural legitimacy by means of transparent criteria and representation mechanisms. The case of Belarus demonstrates that in the absence of such mechanisms, filtering becomes systematically biased toward indicators that are easier for central bureaucracies to standardize and evaluate, regardless of their territorial-scale relevance.

4. Conclusions

This study presents quantitative evidence of a critical governance challenge, namely the systematic elimination of grassroots development vectors and initiatives diversity in centralized administrative systems. In this study, we used Belarus as a case study to illustrate the phenomenon of cumulative attrition experienced by grassroots development vectors of sustainable development as they transition from local to district to regional governance levels [62]. The analysis reveals that approximately 85% of local SWOT indicator diversity does not reach regional planning levels. This loss is not inherently problematic if aggregation decisions are made through transparent procedures with stakeholder input and if development vectors addressing critical sustainability challenges are preserved at higher levels. However, the research suggests that loss is driven by administrative inertia, opaque filtering processes, and funding constraints—mechanisms that lack deliberate evaluation of which local diversity is most important to preserve.

The most consequential discovery of the study is not the prioritization of economic factors, which may be indicative of valid national-level development priorities. Instead, this study focuses on the underlying mechanisms that give rise to economic emphasis. If aggregation decisions are made transparently with deliberate consideration of trade-offs (e.g., “we are prioritizing economic development, which requires reducing focus on social cohesion initiatives”), this is democratically defensible. Nevertheless, in the scenario where economic emphasis manifests through opaque administrative filtration and funding limitations, this constitutes a democratic deficit, resulting in the systematic exclusion of societal values (e.g., environmental stewardship, social cohesion) without deliberate consideration.

The findings indicate that a mere 5–10 percent of grassroot initiative diversity manages to exert influence at the national policy level. Local councils represent about one-seventh of the diversity of indicators at the village/settlement level, and in the robust scenario, this increases to 53. At the district level, losses increase further, indicating that aggregating from the local council level to the district level reduces represented diversity by 60–98%. At the regional level, additional aggregation causes moderate losses, suggesting that by the time development vectors reach regional planning, only about 5–6% of local-level indicator diversity remains. Across all governance levels, the cumulative loss ratio exceeds 20:1 in basic scenarios and 1000:1 in robust scenarios. This finding directly challenges the prevailing policy assumptions concerning decentralization in post-Soviet countries. It also underscores specific mechanisms through which formal decentralization policies fail to translate into meaningful local participation.

The present study examined the influence of centralized governance structures in Belarus on the survival and diversity of grassroots sustainable development vectors as they transition from local to national levels. A substantial body of quantitative evidence, derived from 47 strategic planning documents, has been demonstrated to illustrate that a significant proportion—approximately 85%—of local development vectors diversity is lost through aggregation within hierarchical planning processes. This phenomenon results in the representation of only a limited segment of these proposals in regional and national policy. This systematic attrition is explained by three interlocking mechanisms: administrative inertia, which engenders structural resistance to local innovation; funding and evaluation constraints that privilege standardized, centrally approved proposals; and structural barriers that limit meaningful local autonomy despite formal decentralization reforms.

The findings indicate that, despite the existence of formal decentralization policies, the distribution of decision-making power over resources and policy priorities remains predominantly centralized. Consequently, local development vectors that reflect unique social, environmental, or participatory needs are seldom incorporated into higher-level policies [63,64]. Conversely, economic initiatives that are more readily standardizable tend to persist. This discrepancy undermines the intended social, environmental, and institutional diversity of territorial development and limits the responsiveness and sustainability of public policy at all levels.

For policymakers and reformers in post-Soviet and similar governance contexts, these results underscore the necessity of complementing formal decentralization with specific institutional reforms. It is imperative to enable local ownership of sustainability implementation, to ensure that all local sustainability vectors and initiatives are evaluated before being excluded from higher-level policies and to enable effective implementation and advocacy for community-led sustainability solutions [65]. In the absence of such measures, the potential for local empowerment and effective decentralized development remains largely aspirational.

The following limitations of the study should be noted. This study analyzes strategic planning documents spanning the period from 2005 to 2020. The resolution to terminate the empirical period in 2020 is indicative of constraints in data availability. Specifically, detailed SWOT analyses and district-level strategic documents are more readily accessible for this period. Nevertheless, this temporal boundary imposes a significant restriction on the study’s scope. It does not encompass governance dynamics that occurred after 2020, a period characterized by substantial political and administrative transformations in Belarus.

Future research may encompass the following inquiries. To maintain its relevance, this study requires updating with data from 2020 to 2025. It is recommended that researchers conduct a comparative analysis of post-2020 strategic planning documents to ascertain whether: (1) TDVs loss patterns persist in the current governance context, (2) recent administrative reforms have affected aggregation mechanisms, and (3) Belarus’s evolving international position (EU partnership, Ukraine conflict) has influenced the decentralization trajectory. Conducting such research would result in the transformation of the current baseline study into a longitudinal analysis of governance evolution. Although this study focuses on the context of Belarus, its methodological framework has the potential to be applied more broadly in assessing the effectiveness of a broader scope of decentralization directions. Further comparative studies across other post-Soviet and EaP countries [66] can provide valuable insights to refine the generalizability of these findings and inform future reforms in multilevel governance and sustainable development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.H. and A.S.; methodology, A.H. and A.S.; software, A.H.; validation, A.H., A.S., A.R. and S.K.; formal analysis, A.H.; investigation, A.H. and A.S.; resources, A.H. and A.S.; data curation, A.H. and A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.H. and A.S.; writing—review and editing, A.H., A.S., A.R. and S.K.; visualization, A.H.; supervision, A.R. and S.K.; project administration, A.R.; funding acquisition, A.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the European Union through fundings ENI/2021/423-841-0033 and NDICI-GEO-NEAR/2022/434-092-0050.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their profound respect and gratitude to the reviewers and editors, whose invaluable comments and suggestions have greatly enhanced the quality of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Isola, F.; Leccis, F.; Leone, F. The Integration of Sustainable Development Principles Within Spatial Planning Practices; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Arce, K.; Vanclay, F. Transformative social innovation for sustainable rural development: An analytical framework to assist community-based initiatives. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 74, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbiankova, A.; Shcherbina, E. Evaluation model for sustainable development of settlement system. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mróz, A.; Komorowski, Ł.; Wolański, M.; Stawicki, M.; Kozłowska, P.; Stanny, M. The impact of territorial capital on Cohesion Policy in rural Polish areas. Reg. Stud. 2023, 57, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krantz, V.; Gustafsson, S. Localizing the sustainable development goals through an integrated approach in municipalities: Early experiences from a Swedish forerunner. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2021, 64, 2641–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadin, V.; Stead, D.; Dąbrowski, M.; Fernandez-Maldonado, A.M. Integrated, adaptive and participatory spatial planning: Trends across Europe. Reg. Stud. 2021, 55, 791–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinowski, S.; Szczygieł, O. Concerns About Covid-19 in the Eyes of Respondents: Example from Poland. In World Politics in the Age of Uncertainty; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Altrock, U.; Liang, X. Towards collaborative planning: Deliberative knowledge utilisation and conflict resolution in urban regeneration in South China. disP-Plan. Rev. 2023, 59, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizenberg, E.; Werner, H.; van Geldere, S. Helping citizens to lobby themselves. Experimental evidence on the effects of citizen lobby engagement on internal efficacy and political support. J. Eur. Public Policy 2023, 31, 3561–3590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nederhand, J.; Edelenbos, J. Legitimate public participation: A Q methodology on the views of politicians. Public Adm. Rev. 2023, 83, 522–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komorowski, Ł.; Rosa, A.; Kalinowski, S. Koncepcja smart villages—czy to kolejny etap odnowy wsi? Wieś Rol. 2023, 3, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanou, M.P.; Ros-Tonen, M.A.F.; Reed, J.; Moombe, K.; Sunderland, T. Integrating local and scientific knowledge: The need for decolonising knowledge for conservation and natural resource management. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladner, A.; Keuffer, N.; Baldersheim, H.; Hlepas, N.; Swianiewicz, P.; Steyvers, K.; Navarro, C. Patterns of Local Autonomy in Europe; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick-Sagoe, C. Decentralization for improving the provision of public services in developing countries: A critical review. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2020, 8, 1804036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeemering, E.S. Sustainability management, strategy and reform in local government. Public Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 136–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomianek, I. Preparation of Local Governments to Implement the Concept of Sustainable Development Against Demographic Changes in Selected Rural and Urban-Rural Communes of the Warmińsko-Mazurskie Voivodship. Probl. Zarz. 2018, 16, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, K.; Martinez-Vazquez, J.; Hankla, C. Political decentralization and corruption: Exploring the conditional role of parties. Econ. Politics 2023, 35, 411–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivagrakau, A.; Lyampert, A. Guide for Developing Strategies for Sustainable Development of Rural Areas, 1st ed.; Kolorgrad: Minsk, Belarus, 2022; p. 49. [Google Scholar]

- Sivagrakau, A. Development and implementation of sustainable development strategies of territories in the context of self-government and decentralization. Environ. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 3–4, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Vazquez, J.; Lago-Peñas, S.; Sacchi, A. The impact of fiscal decentralization: A survey. J. Econ. Surv. 2017, 31, 1095–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, K.; Kaiser, K.A.; Smoke, P.J. The Political Economy of Decentralization Reforms; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogués, S.; González-González, E.; Cordera, R. Planning regional sustainability: An index-based framework to assess spatial plans. Application to the region of Cantabria (Spain). J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 225, 510–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkova, M.; Goncharova, N.; Ladik, E.; Monastyrskaya, M.; Onishchuk, V. The Inter-municipal Ecological Park Arrangement. In Architectural, Construction, Environmental and Digital Technologies for Future Cities; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goryńska-Goldmann, E. Genesis and the term of local food in relation to the idea of sustainable consumption / Geneza i pojęcie żywności lokalnej w powiązaniu z ideą zrównoważonej konsumpcji. J. Tour. Reg. Dev. 2019, 11, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Högström, J.; Brokking, P.; Balfors, B.; Hammer, M. Approaching Sustainability in Local Spatial Planning Processes: A Case Study in the Stockholm Region, Sweden. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barca, F.; McCann, P.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. The case for regional development intervention: Place-based versus place-neutral approaches. J. Reg. Sci. 2012, 52, 134–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantanen, M.; Czarnecki, A. Second-home owners as local developers: Roles and influencing factors. J. Rural Stud. 2023, 97, 560–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbiankova, A.; Scherbina, E.; Budzevich, M. Exploring the Significance of Heritage Preservation in Enhancing the Settlement System Resilience. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaranta, G.; Salvia, R. An Index to Measure Rural Diversity in the Light of Rural Resilience and Rural Development Debate. Eur. Countrys. 2014, 6, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deslatte, A.; Szmigiel-Rawska, K.; Tavares, A.F.; Ślawska, J.; Karsznia, I.; Łukomska, J. Land use institutions and social-ecological systems: A spatial analysis of local landscape changes in Poland. Land Use Policy 2022, 114, 105937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczak, A.; Cermakova, K.; Kalinowski, S.; Hromada, E.; Mec, M. Measurement of Sustainable Development and Standard of Living in Territorial Units: Methodological Concept and Application. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 4604–4630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żuber, P.; Szmigiel-Rawska, K.; Krukowska, J. Boosting national urban policies by European integration. The case of Poland1. In A Modern Guide to National Urban Policies in Europe; Edward Elgar Publishing: Camberley, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, D. Grassroots urbanism in contemporary São Paulo. URBAN Des. Int. 2020, 25, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halamska, M.; Stanny, M. Temporal and spatial diversification of rural social structure: The case of Poland. Sociol Rural. 2021, 61, 578–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedek, J.; Ivan, K.; Török, I.; Temerdek, A.; Holobâcă, I. Indicator-based assessment of local and regional progress toward the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): An integrated approach from Romania. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 860–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, L.; Jennings, W.; Stoker, G. Understanding the geography of discontent: Perceptions of government’s biases against left-behind places. J. Eur. Public Policy 2024, 31, 1719–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arends, H.; Brik, T.; Herrmann, B.; Roesel, F. Decentralization and trust in government: Quasi-experimental evidence from Ukraine. J. Comp. Econ. 2023, 51, 1356–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyttä, M.; Randrup, T.; Sunding, A.; Rossi, S.; Harsia, E.; Palomäki, J.; Kajosaari, A. Prioritizing participatory planning solutions: Developing place-based priority categories based on public participation GIS data. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 239, 104868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theiss, M.; Kurowska, A. Being denied and granted social welfare and the propensity to protest. Acta Politica 2019, 54, 458–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladner, A.; Keuffer, N.; Bastianen, A. Local autonomy around the world: The updated and extended Local Autonomy Index (LAI 2.0). Reg. Fed. Stud. 2023, 17, 163–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, S.; Richiedei, A. Territorial Governance for Sustainable Development: A Multi-Level Governance Analysis in the Italian Context. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajida. Three decades of multilevel governance research: A scientometric and conceptual mapping in the social sciences. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2025, 12, 101745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. A Territorial Approach to the Sustainable Development Goals: Synthesis report; OECD Urban Policy Reviews; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, G.; Failler, P. Biodiversity, multi-level governance, and policy implementation in Europe: A comparative analysis at the subnational level. J. Public Policy 2024, 44, 546–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherghina, S.; Ekman, J.; Podolian, O. When promises reach boundaries: Political participation in post-communist countries. Eur. Soc. 2023, 25, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, D. Decentralization, legitimacy, and democracy in post-Soviet Central Asia. J. Eurasian Stud. 2022, 13, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, K.; Wicki, M.; Kaufmann, D. Public support for participation in local development. World Dev. 2024, 178, 106569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetrulo, N.M.; Cetrulo, T.B.; Ramos, T.B.; Lopes Gonçalves-Dias, S.F. Exploring Critical Issues for Local Sustainability Assessment Through Community Participation. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2025, 27, 100718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmäing, S. Urban democracy in post-Maidan Ukraine: Conflict and cooperation between citizens and local governments in participatory budgeting. Eur. Soc. 2024, 26, 230–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manteuffel-Szoege, H. Comparing development sustainability in Belarus, Poland and Ukraine with special respect to rural areas. Zesz. Nauk. Szkoły Głównej Gospod. Wiej. Warszawie. Probl. Rol. Swiat. 2007, 1, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.; Pantyley, V.; Blaszke, M.; Fakeyeva, L.; Lozynskyy, R.; Petrisor, A.I. Spatial Planning at the National Level: Comparison of Legal and Strategic Instruments in a Case Study of Belarus, Ukraine, and Poland. Land 2023, 12, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faundez, J. Douglass North’s Theory of Institutions: Lessons for Law and Development. Hague J. Rule Law 2016, 8, 373–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhold, T.; Wiesweg, N. Principal-agent theory. In A Handbook of Management Theories and Models for Office Environments and Services; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2021; pp. 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Strategy for Sustainable Development of the Republic of Belarus./National Committee for Sustainable Development of the Republic of Belarus; LLC ‘Belsens’: Minsk, Belarus, 1997; p. 216.

- National Strategy for Sustainable Social and Economic Development of the Republic of Belarus for the Period up to 2020. Available online: https://www.oneplanetnetwork.org/sites/default/files/from-crm/national_strategy_for_sustainable_development_of_belarus.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2023).

- National Strategy for Sustainable Social and Economic Development of the Republic of Belarus for the Period up to 2030. Available online: https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/blr189942.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2023).

- Map of Belarus. Available online: https://data.nextgis.com/ru/region/BY/base (accessed on 5 November 2023).

- Lysek, J.; Krukowska, J.; Navarro, C.; Jones, A.; Copus, C. Alike in Diversity? Local Action Groups in Nine European Countries; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadimitriou, N. Cybernetic spatial planning: Steering, managing or just letting go? In The Ashgate Research Companion to Planning Theory; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2016; pp. 443–464. [Google Scholar]

- Karadimitriou, N.; Magnani, G.; Timmerman, R.; Marshall, S.; Hudson-Smith, A. Designing an incubator of public spaces platform: Applying cybernetic principles to the co-creation of spaces. Land Use Policy 2022, 119, 106187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetrova, N.; Shtofer, G.; Gaysarova, A.; Ryvkina, O. Regional ecological security assessment in the environmental management. E3S Web Conf. 2020, 164, 07004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasyanenko, A. Participation of Civil Society Organizations in Sustainable Regional Development. 2021. Available online: http://edoc.bseu.by:8080/bitstream/edoc/89194/1/Kasyanenko_A._P..pdf (accessed on 5 November 2023).

- Gendźwiłł, A.; Krukowska, J.; Swianiewicz, P. Local State–Society Relations in Poland; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegewald, S. Locality as a safe haven: Place-based resentment and political trust in local and national institutions. J. Eur. Public Policy 2024, 31, 1749–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, N.; Stasiak, D.; von Schneidemesser, D. Community resilience through bottom–up participation: When civil society drives urban transformation processes. Community Dev. J. 2024, 60, 528–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decentralisation and Local Self-Government in Eastern Partnership Countries. Available online: https://euneighbourseast.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/decentralisation-and-local-self-government-in-eastern-partnership-countries.pdf??%3Cfont%20color= (accessed on 16 September 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.