Resilience Indicators for a Road Transport Network to Access Emergency Health Services

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Centrality measures, to identify the most critical nodes and arcs in the network;

- Metrics on network efficiency, to identify how the removal of nodes/arcs affects the efficiency.

- the application of graph theory-based measures, adapted to directed graphs;

- to provide a practical methodology based on data easily accessible;

- to propose an approach designed to be easily transferable and exportable.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Topological-Based Indicators

2.2. Time-Based Indicators

2.3. Demand-Based Indicators

3. Materials and Methods

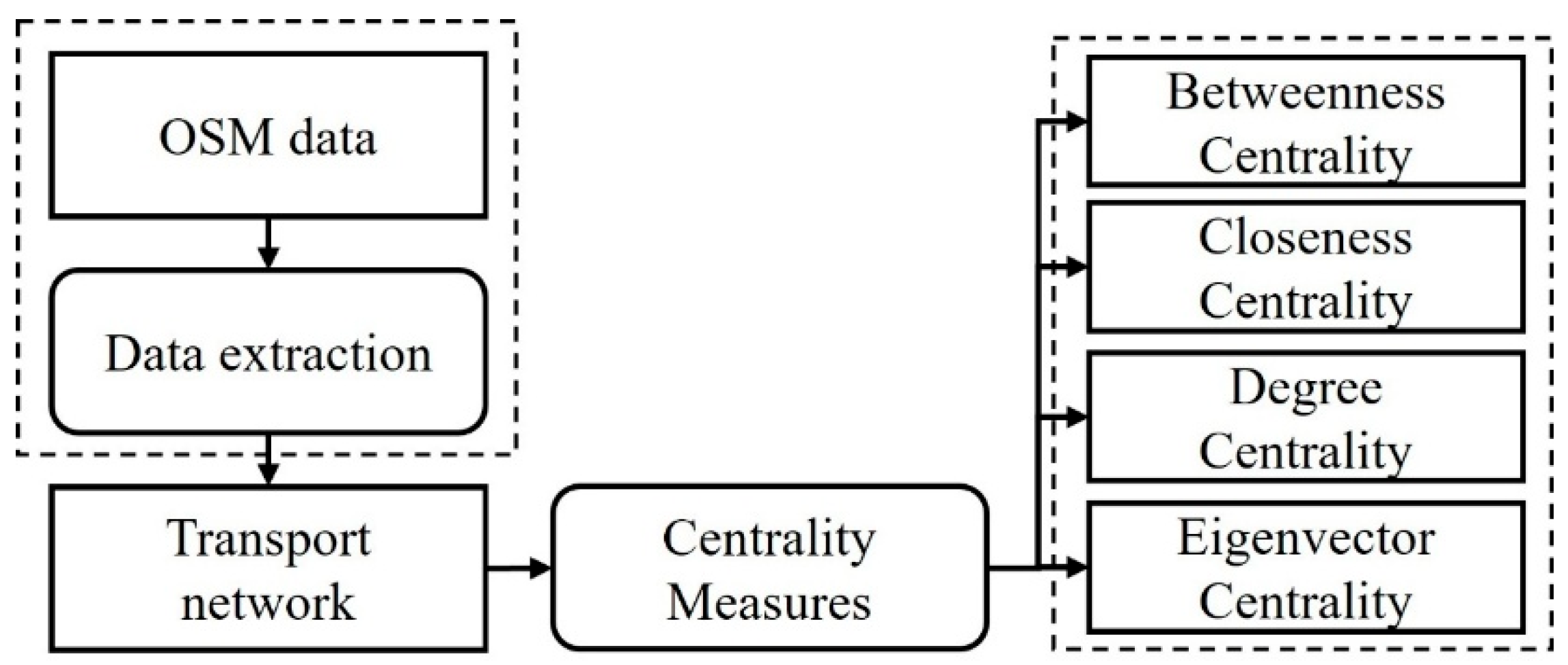

3.1. Centrality Measures

3.1.1. Betweenness Centrality

3.1.2. Closeness Centrality

3.1.3. Degree Centrality

3.1.4. Eigenvector Centrality

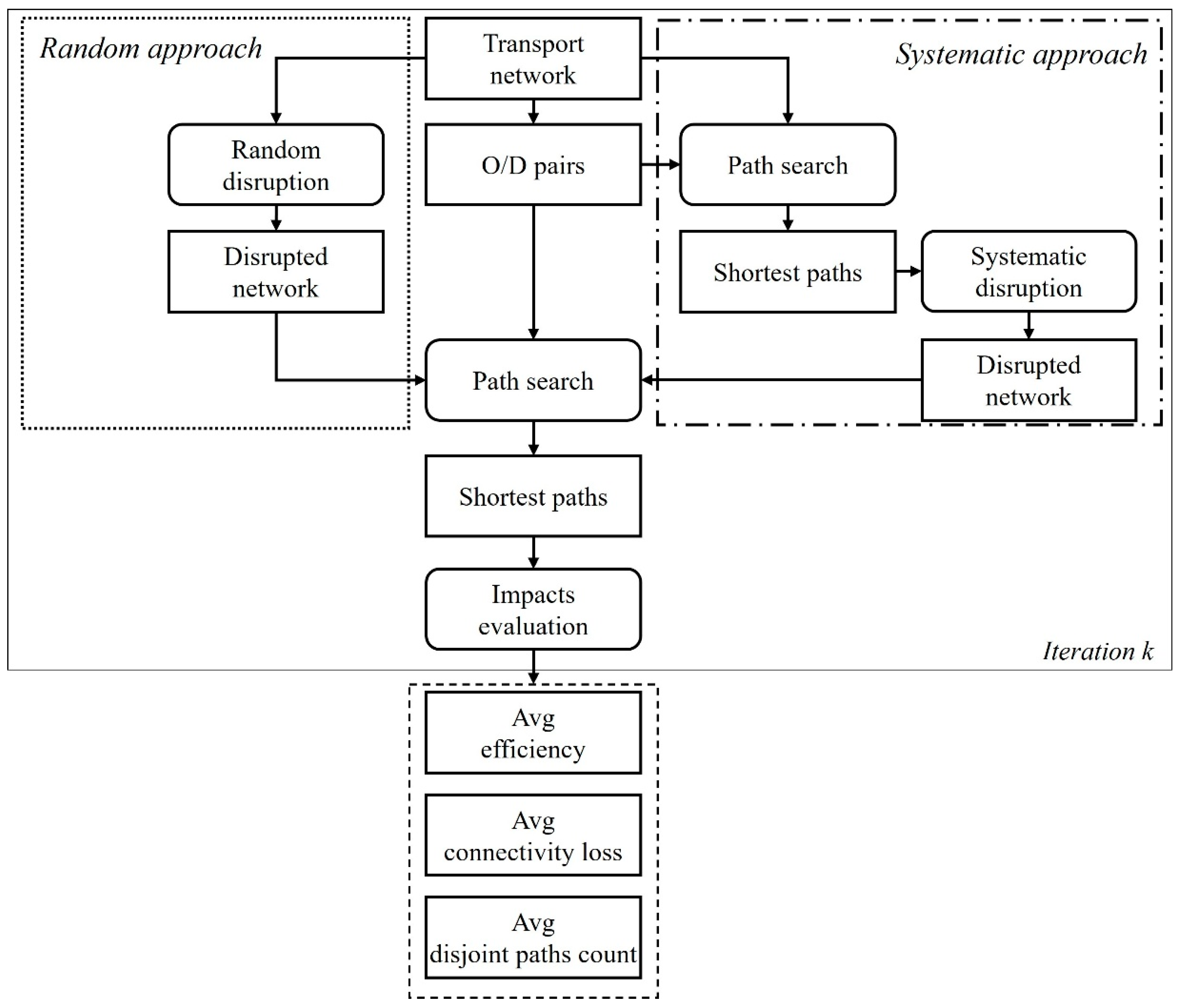

3.2. Impacts Evaluation

3.3. Measures Comparison

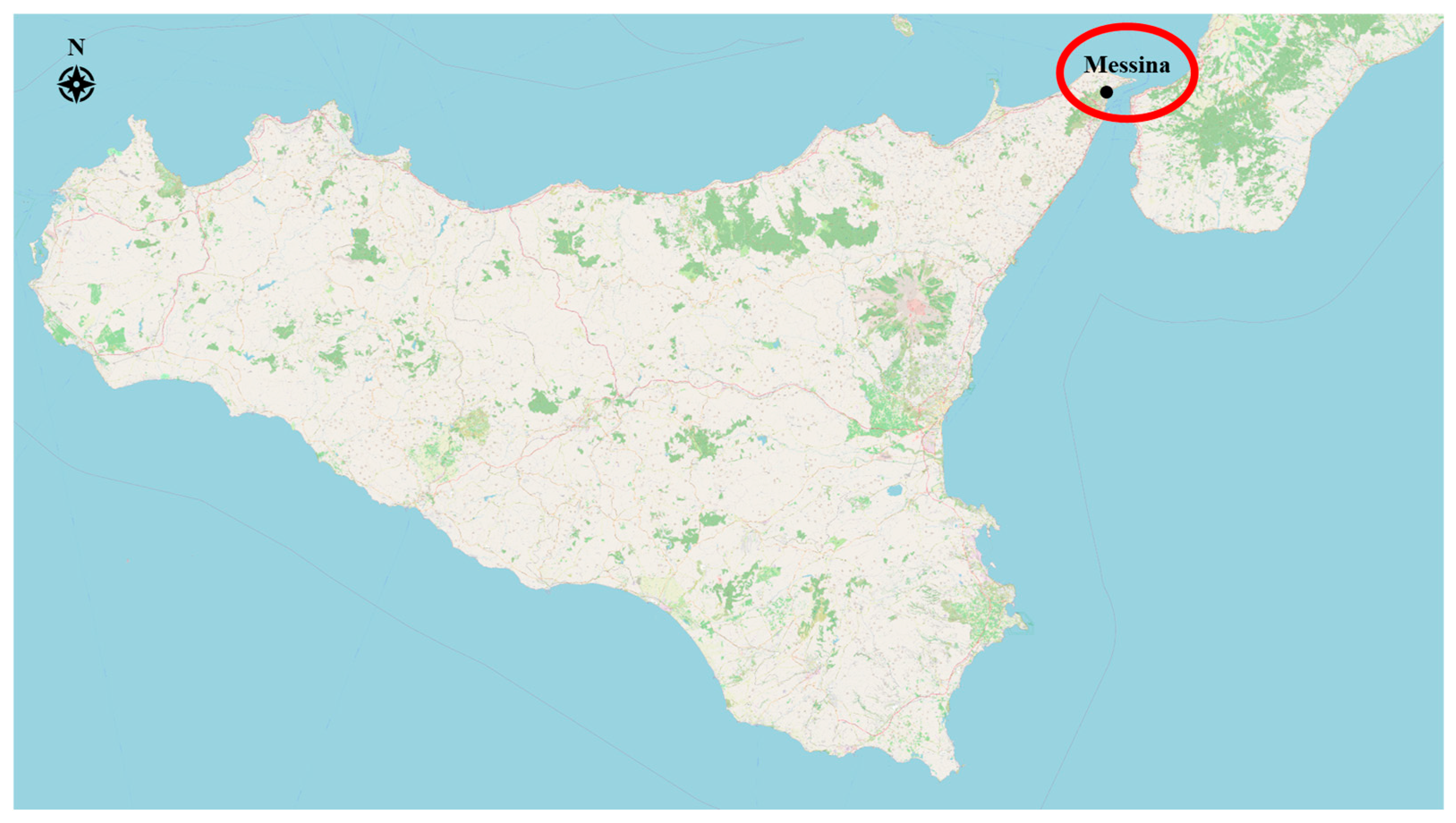

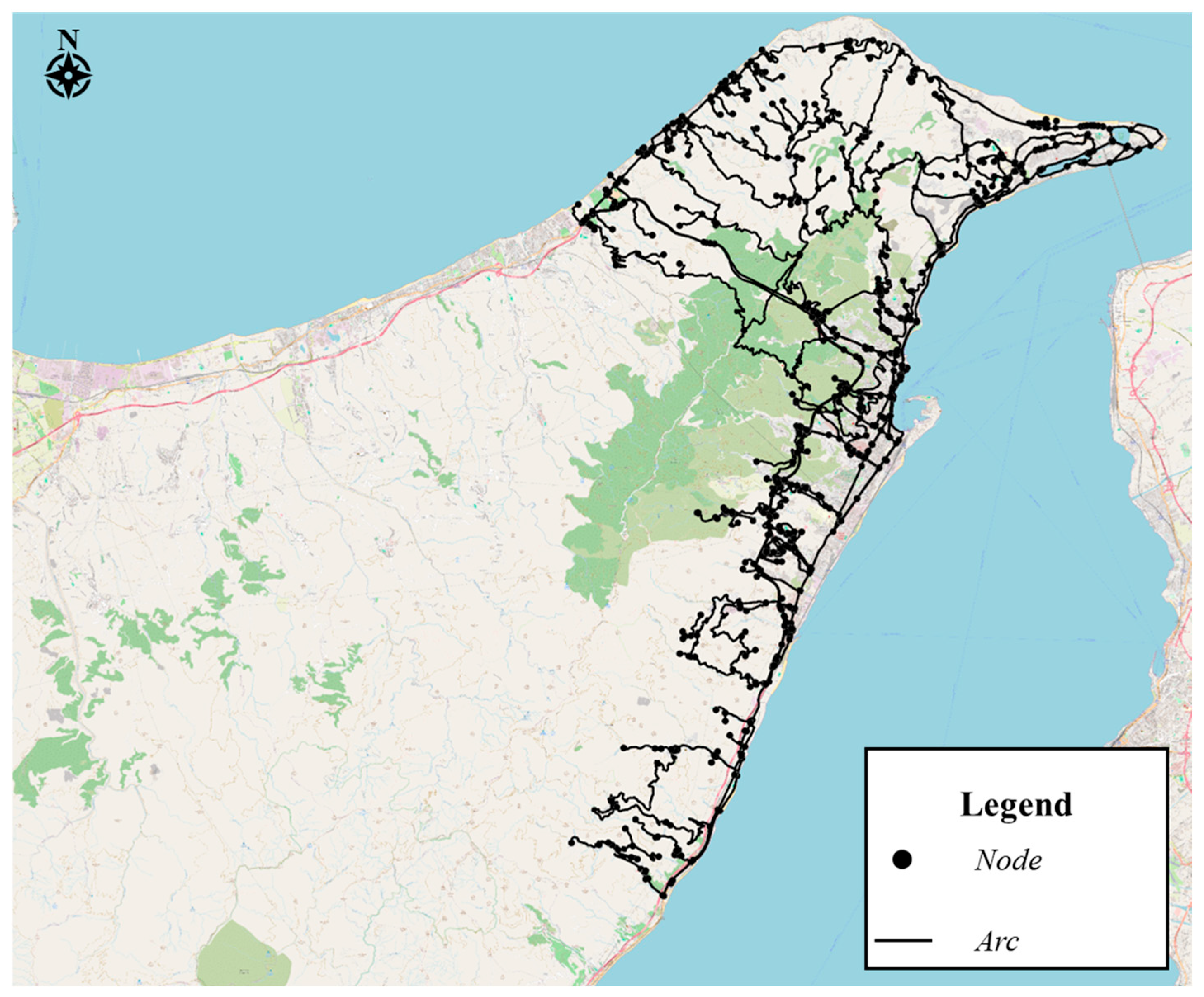

4. Case Study

5. Discussion

5.1. Centrality Measures

5.2. Impacts Evaluation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Adlakha, D.; Parra, D.C. Mind the Gap: Gender Differences in Walkability, Transportation and Physical Activity in Urban India. J. Transp. Health 2020, 18, 100875. [Google Scholar]

- Aghababaei, M.T.S.; Costello, S.B.; Ranjitkar, P. Measures to Evaluate Post-Disaster Trip Resilience on Road Networks. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021, 95, 103154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, J.; Aultman-Hall, L.; Novak, D. A Review of Current Practice in Network Disruption Analysis and an Assessment of the Ability to Account for Isolating Links in Transportation Networks. Transp. Lett. 2009, 1, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, F.; Vitetta, A. Risk Evaluation in a Transportation System. Int. J. SDP 2006, 1, 170–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1973, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, M.; Peck, H. Building the Resilient Supply Chain. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2004, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freckleton, D.; Heaslip, K.; Louisell, W.; Collura, J. Evaluation of Resiliency of Transportation Networks after Disasters. Transp. Res. Rec. 2012, 2284, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneau, M.; Chang, S.E.; Eguchi, R.T.; Lee, G.C.; O’Rourke, T.D.; Reinhorn, A.M.; Shinozuka, M.; Tierney, K.; Wallace, W.A.; von Winterfeldt, D. A Framework to Quantitatively Assess and Enhance the Seismic Resilience of Communities. Earthq. Spectra 2003, 19, 733–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Yang, B. Towards Resilient and Smart Urban Road Networks: Connectivity Restoration via Community Structure. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 75, 103344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Xu, J. Assessing Road Network Resilience in Disaster Areas from a Complex Network Perspective: A Real-Life Case Study from China. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 100, 104167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, B.; Ortega, E.; Cuevas-Wizner, R.; Ledda, A.; De Montis, A. Assessing Road Network Resilience: An Accessibility Comparative Analysis. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 95, 102851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Xiao, J.; Tang, J. Research on Urban Agglomeration Spatial Network Structure in the Middle Reaches of the Yangtze River Based on Real-Time Traffic Accessibility Scenario Analysis. Transp. Lett. 2025, 17, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Chen, A.; Xu, G.; Yang, C.; Lam, W.H.K. Enhancing Network Resilience by Adding Redundancy to Road Networks. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2021, 154, 102448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, E.; Costello, S.B.; Henning, T.F. Contribution of Network Redundancy to Reducing Criticality of Road Links. Transp. Res. Rec. 2024, 2678, 1574–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohouenou, P.Y.R.; Neves, L.A.C.; Christodoulou, A.; Christidis, P.; Lo Presti, D. Using a Hazard-Independent Approach to Understand Road-Network Robustness to Multiple Disruption Scenarios. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 93, 102672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, N.; Han, Y.; Fan, H.; Tian, P.; Wang, Y.; Guo, D. Robustness Assessment of a Multilayer Composite Network with a Two-Stage Fusion Community Detection Algorithm. Transp. Lett. 2025, 17, 1819–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivek, S.; Conner, H. Urban Road Network Vulnerability and Resilience to Large-Scale Attacks. Saf. Sci. 2022, 147, 105575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haritha, P.C.; Anjaneyulu, M.V.L.R. Comparison of Topological Functionality-Based Resilience Metrics Using Link Criticality. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 243, 109881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Huang, H.; Li, G.; Han, B.; Yuan, Z.; Ma, H. A Systematic Review of Resilience Assessment and Enhancement of Urban Integrated Transportation Networks. J. Transp. Geogr. 2025, 129, 104420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Miller-Hooks, E.; Denny, K. Assessing the Role of Network Topology in Transportation Network Resilience. J. Transp. Geogr. 2015, 46, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagloee, S.A.; Sarvi, M.; Wolshon, B.; Dixit, V. Identifying Critical Disruption Scenarios and a Global Robustness Index Tailored to Real Life Road Networks. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2017, 98, 60–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Chopra, S.S. Interconnectedness Enhances Network Resilience of Multimodal Public Transportation Systems for Safe-to-Fail Urban Mobility. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, N.Y.; Duzgun, H.S.; Heinimann, H.R.; Wenzel, F.; Gnyawali, K.R. Framework for Improving the Resilience and Recovery of Transportation Networks under Geohazard Risks. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 31, 832–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ip, W.H.; Wang, D. Resilience and Friability of Transportation Networks: Evaluation, Analysis and Optimization. IEEE Syst. J. 2011, 5, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarzadeh, M.; Memarmontazerin, S.; Derrible, S.; Salehi Reihani, S.F. The Role of Travel Demand and Network Centrality on the Connectivity and Resilience of an Urban Street System. Transportation 2019, 46, 1127–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edrissi, A.; Nourinejad, M.; Roorda, M.J. Transportation Network Reliability in Emergency Response. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2015, 80, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhavathrathan, B.K.; Patil, G.R. Algorithm to Compute Urban Road Network Resilience. Transp. Res. Rec. 2018, 2672, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, M.; Mostashari, A.; Nilchiani, R. Measuring the Resiliency of the Manhattan Points of Entry in the Face of Severe Disruption. AJEAS 2011, 4, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganin, A.A.; Kitsak, M.; Marchese, D.; Keisler, J.M.; Seager, T.; Linkov, I. Resilience and Efficiency in Transportation Networks. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1701079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faturechi, R.; Miller-Hooks, E. Travel Time Resilience of Roadway Networks under Disaster. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2014, 70, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godazgar, B.; Balomenos, G.P.; Tighe, S.L. Resilience Surface for Quantifying Hazard Resiliency of Transportation Infrastructure. Resilient Cities Struct. 2023, 2, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Lin, S.; Ci, Y.; Li, R. Resilience Evaluation and Improvement of Post-Disaster Multimodal Transportation Networks. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2024, 189, 104243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wu, M.; Yuen, K.F. A Novel Method to Assess Urban Multimodal Transportation System Resilience Considering Passenger Demand and Infrastructure Supply. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 238, 109478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, Y.; Karami Mohammadi, R.; Yang, T.Y. Resource-Based Seismic Resilience Optimization of the Blocked Urban Road Network in Emergency Response Phase Considering Uncertainties. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 85, 103496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, Y.; Mohammadi, R.K.; Yang, T.Y. A Comprehensive Approach in Post-Earthquake Blockage Prediction of Urban Road Network and Emergency Resilience Optimization. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 244, 109887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Hu, X.; Wang, N. Resilience Analysis in Road Traffic Systems to Rainfall Events: Road Environment Perspective. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2024, 126, 104000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabi, M.; Kyung Hyun, K.; Mattingly, S. Adaptable Resilience Assessment Framework to Evaluate an Impact of a Disruptive Event on Freight Operations. Transp. Res. Rec. 2021, 2675, 1327–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, P.; Furno, A.; El Faouzi, N.-E. Road Network Resilience: How to Identify Critical Links Subject to Day-to-Day Disruptions. Transp. Res. Rec. 2018, 2672, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Lima, M.; Medda, F. A New Measure of Resilience: An Application to the London Underground. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2015, 81, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Yang, X.; Chen, A.; Zhu, T.; Wu, J. Assessing the Resilience of Multi-Modal Transportation Networks with the Integration of Urban Air Mobility. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2025, 195, 104465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A.; Prager, F.; Rose, A. Transportation Security and the Role of Resilience: A Foundation for Operational Metrics. Transp. Policy 2011, 18, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Miller-Hooks, E. Resilience: An Indicator of Recovery Capability in Intermodal Freight Transport. Transp. Sci. 2012, 46, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller-Hooks, E.; Zhang, X.; Faturechi, R. Measuring and Maximizing Resilience of Freight Transportation Networks. Comput. Oper. Res. 2012, 39, 1633–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeing, G. OSMnx: A Python Package to Work with Graph-Theoretic OpenStreetMap Street Networks. J. Open Source Softw. 2017, 2, 215. [Google Scholar]

- Boeing, G. Modeling and Analyzing Urban Networks and Amenities with OSMnx. Geogr. Anal. 2025, 57, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagberg, A.A.; Schult, D.A.; Swart, P.J. Exploring Network Structure, Dynamics, and Function Using NetworkX. In Proceedings of the 7th Python in Science Conference, Pasadena, CA, USA, 19–24 August 2008; pp. 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Jayaweera, I.M.L.N.; Perera, K.K.K.R.; Munasinghe, J. Centrality Measures to Identify Traffic Congestion on Road Networks: A Case Study of Sri Lanka. IOSR J. Math. 2017, 13, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, L.C. A Set of Measures of Centrality Based on Betweenness. Sociometry 1977, 40, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkley, A.; Barbosa, H.; Barthelemy, M.; Ghoshal, G. From the Betweenness Centrality in Street Networks to Structural Invariants in Random Planar Graphs. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandes, U. On Variants of Shortest-Path Betweenness Centrality and Their Generic Computation. Soc. Netw. 2008, 30, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, M.A. An Improved Index of Centrality. Behav. Sci. 1965, 10, 161–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, L.C. Centrality in Social Networks Conceptual Clarification. Soc. Netw. 1978, 1, 215–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamakan, S.M.H.; Nurgaliev, I.; Qu, Q. Opinion Leader Detection: A Methodological Review. Expert Syst. Appl. 2019, 115, 200–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonacich, P. Technique for Analyzing Overlapping Memberships. Sociol. Methodol. 1972, 4, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latora, V.; Marchiori, M. Efficient Behavior of Small-World Networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 87, 198701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thulasiraman, K.; Swamy, M.N.S. Graphs: Theory and Algorithms; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-118-03025-7. [Google Scholar]

- Cascetta, E. Transportation Systems Analysis: Models and Applications, 2nd ed.; Springer Optimization and Its Applications; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-387-75856-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ashja-Ardalan, S.; Alesheikh, A.A.; Sharif, M.; Wittowsky, D. Resilience of Urban Road Networks to Climate Change: A Spatial-Topological Approach. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2025, 148, 104948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Li, J.; Yuen, K.F.; Mao, X. Towards Vulnerability Urban Road Networks: Adaptive Topological Optimization and Network Performance Analysis. J. Transp. Geogr. 2025, 126, 104237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Yan, S.; Yan, W.; Li, Z.; Yang, H.; Huang, X. The Denser the Road Network, the More Resilient It Is?—A Multi-Scale Analytical Framework for Measuring Road Network Resilience. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, D.; Dodge, S. Disaster Vulnerability in Road Networks: A Data-Driven Approach through Analyzing Network Topology and Movement Activity. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2025, 39, 1035–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haklay, M.; Weber, P. OpenStreetMap: User-Generated Street Maps. IEEE Pervasive Comput. 2008, 7, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göring, F. Short Proof of Menger’s Theorem. Discret. Math. 2000, 219, 295–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmonds, J.; Karp, R.M. Theoretical Improvements in Algorithmic Efficiency for Network Flow Problems. J. ACM 1972, 19, 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measure | Definition | Interpretation in Network |

|---|---|---|

| Degree Centrality | Number of direct connections a node has. | Identifies local hubs with high connectivity. |

| Betweenness Centrality | Frequency with which a node lies on shortest paths between other nodes. | Detects critical connectors and potential bottlenecks. |

| Closeness Centrality | Reciprocal of the average shortest-path distance from a node to all others. | Measures overall proximity and efficiency of access. |

| Eigenvalue Centrality | Assigns a score to each node based on the principle that connections to high-scoring nodes contribute more than connections to low-scoring nodes. | Measures a node’s importance based on connections to other important nodes. |

| Paper | Betweenness Centrality | Closeness Centrality | Degree Centrality | Eigenvector Centrality | Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashja-Ardalan et al. [59] | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Nie et al. [60] | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Wei and Xu [11] | √ | √ | |||

| Lu et al. [61] | √ | √ | |||

| Alizadeh and Dodge [62] | √ | ||||

| This work | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Characteristic | Number |

|---|---|

| Characteristics of the graph | |

| Number of nodes | 1033 |

| Number of arcs | 2018 |

| Arcs classification | |

| Motorway | 58 |

| Primary | 765 |

| Secondary | 659 |

| Tertiary | 536 |

| Residential * | 8058 |

| Unclassified * | 1318 |

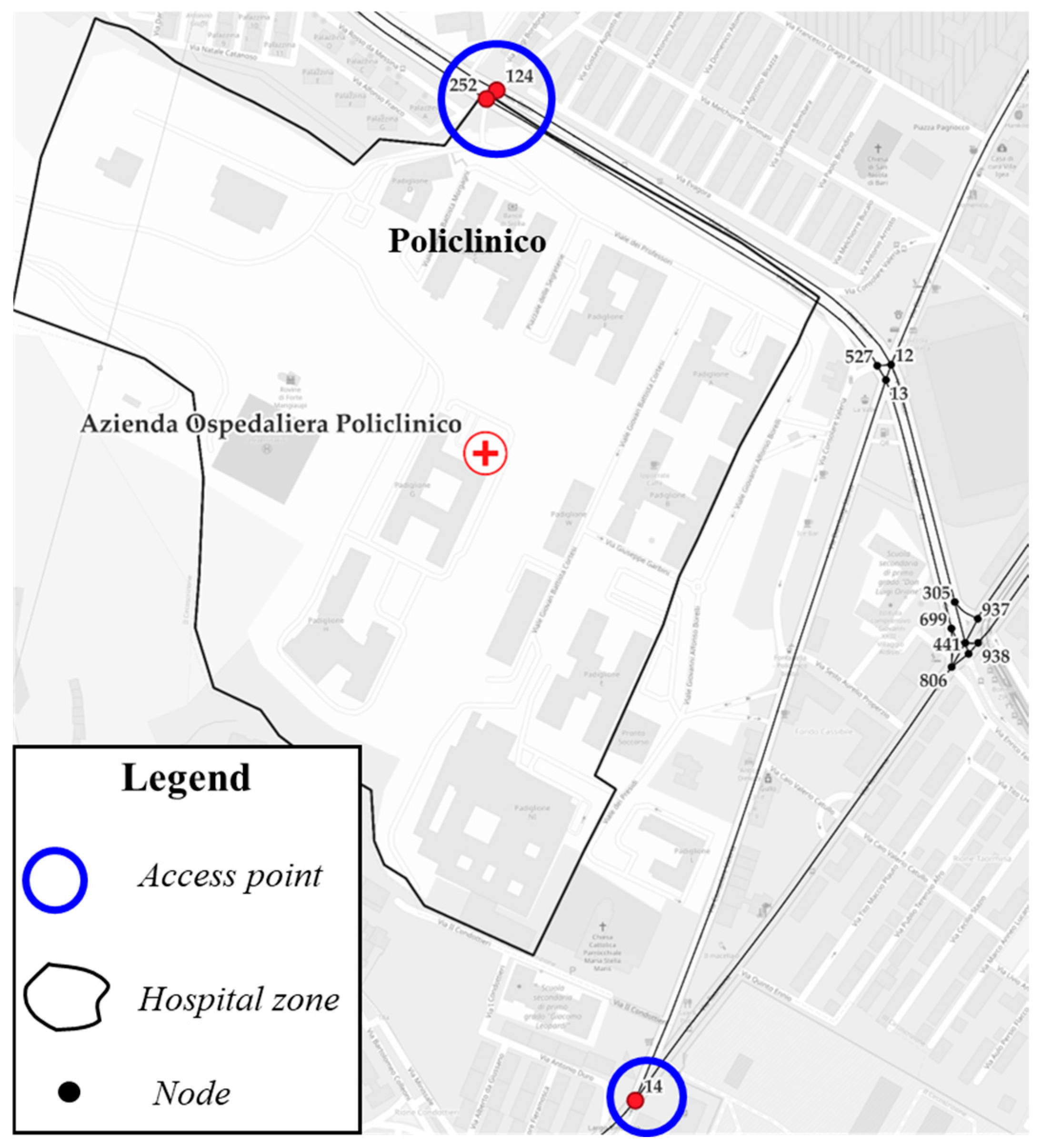

| Hospital Facility | Nodes ID |

|---|---|

| Policlinico | 14, 124, 252 |

| Piemonte | 10, 193, 254, 256 |

| Papardo | 248, 250, 946 |

| Statistics | Values |

|---|---|

| N. of O/D pairs | 10,230 |

| Minimum | 1 |

| Maximum | 83 |

| Mean | 35.60 |

| Variance | 282.72 |

| Mode | 50 |

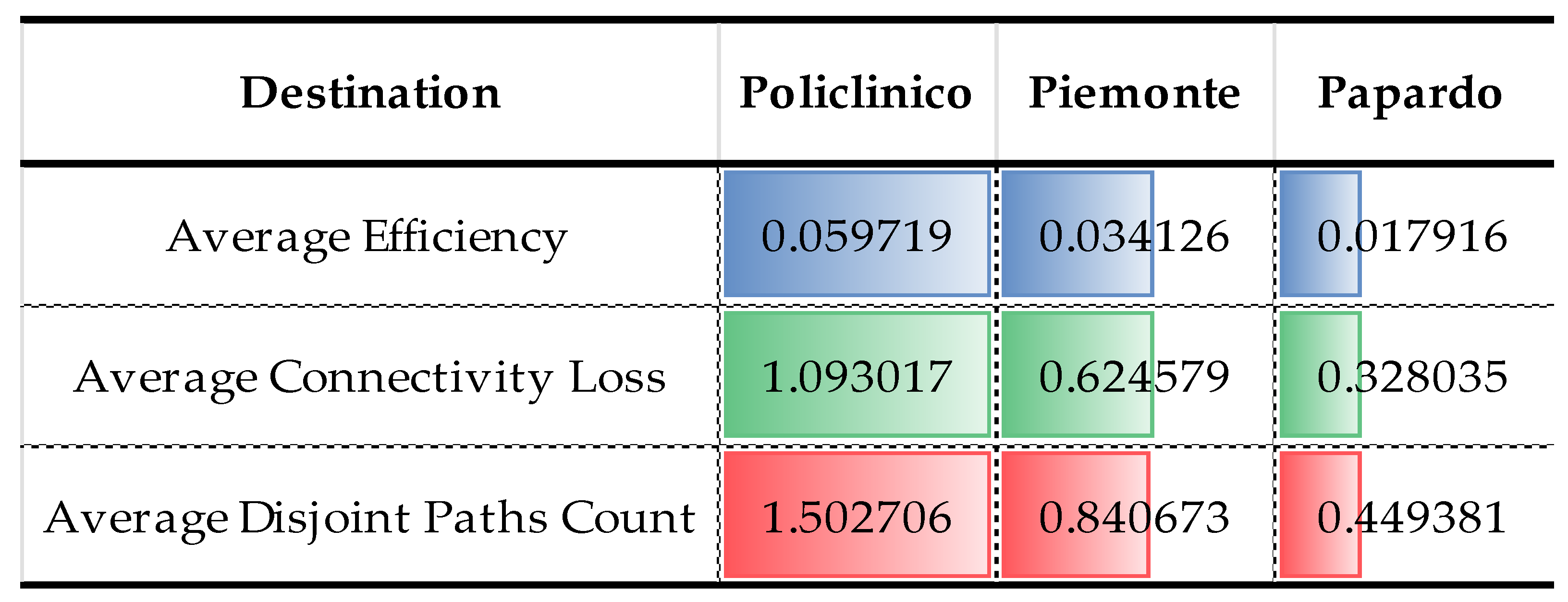

| Destination | Policlinico | Piemonte | Papardo |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disconnected O/D | 534 | 672 | 501 |

| Number of removed arcs | 1528 | 1677 | 1496 |

| Policlinico | Piemonte | Papardo | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arc | Freq | Arc | Freq | Arc | Freq |

| 388-18 | 32 | 18-933 | 34 | 18-933 | 36 |

| 386-388 | 21 | 388-18 | 32 | 386-388 | 30 |

| 18-933 | 21 | 386-388 | 30 | 388-18 | 21 |

| 412-469 | 19 | 412-469 | 22 | 412-469 | 13 |

| 817-494 | 14 | 469-471 | 19 | 370-363 | 13 |

| 469-471 | 14 | 370-363 | 15 | 619-221 | 11 |

| 558-556 | 12 | 619-221 | 14 | 516-518 | 11 |

| 619-221 | 11 | 885-884 | 11 | 469-471 | 11 |

| 848-790 | 10 | 372-379 | 10 | 374-373 | 9 |

| 633-619 | 10 | 182-32 | 10 | 377-372 | 8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Di Gangi, M.; Belcore, O.M.; Polimeni, A. Resilience Indicators for a Road Transport Network to Access Emergency Health Services. Sustainability 2026, 18, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010027

Di Gangi M, Belcore OM, Polimeni A. Resilience Indicators for a Road Transport Network to Access Emergency Health Services. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010027

Chicago/Turabian StyleDi Gangi, Massimo, Orlando Marco Belcore, and Antonio Polimeni. 2026. "Resilience Indicators for a Road Transport Network to Access Emergency Health Services" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010027

APA StyleDi Gangi, M., Belcore, O. M., & Polimeni, A. (2026). Resilience Indicators for a Road Transport Network to Access Emergency Health Services. Sustainability, 18(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010027