Highlights

What are the main findings?

- The proposed LLM-LCSA architecture improves threat detection accuracy by an average of 7.92% and reduces total system response time by 44.52% compared to traditional methods.

- A Mixture of Experts (MoEs) mechanism incorporating a dynamic threat–expert association matrix enables adaptive and real-time identification of complex threats.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- The cloud–edge–end hierarchical framework provides a scalable and efficient architecture for secure, intelligent collaboration in large-scale UAV swarms.

- The resource-aware multi-objective decision model ensures reliable performance under stringent resource constraints, enhancing practicality for real-world deployments.

Abstract

With the development of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) technology, multimachine collaborative operations have become the core model for increasing mission effectiveness. However, large-scale UAV clusters face challenges such as dynamic security threats, heterogeneous data fusion difficulties, and resource-constrained decision-making delays. Traditional single-machine intelligent architectures have limitations when addressing new threats, such as insufficient real-time response capabilities. To address these issues, this paper presnts an LLM-layered collaborative security architecture (LLM-LCSA) for multimachine collaborative security. This architecture optimizes the spatiotemporal fusion efficiency of multisource asynchronous data through cloud–edge–end collaborative deployment, combining an end lightweight LLM, an edge medium LLM, and a cloud-based foundation LLM. Additionally, a Mixture of Experts (MoEs) intelligent algorithm that dynamically activates the most relevant expert models by leveraging a threat–expert association matrix is introduced, thereby increasing the accuracy of complex threat identification and dynamic adaptability. Moreover, a resource-aware multi-objective optimization model is constructed to generate optimal decisions under resource constraints. Simulation results indicate that compared with traditional methods, LLM-LCSA achieves an average 7.92% improvement in the threat detection accuracy, reduces the system’s total response time by 44.52%, and enables resource scheduling during off-peak periods. This architecture provides an efficient, intelligent, and scalable solution for secure collaboration among UAV swarms. Future research should further explore its application potential in 6G network integration and large-scale swarm environments.

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

With the large-scale application of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) technology in critical areas such as disaster response [1], agricultural plant protection [2], power inspection [3], and logistics and distribution [4], multi-UAV coordination has become a core approach for increasing mission effectiveness. With the gradual improvement in network communication technology, the number of UAVs that can be covered by a UAV cluster is also gradually increasing. Compared with UAV clusters with a small number of UAVs, large-scale UAV clusters can carry more payloads, significantly increasing the applicability of UAV clusters.

However, while clustering increases scalability, it also introduces systemic challenges such as dynamic security threat generalization, low cross-platform collaboration efficiency, and delayed decision-making because of resource constraints [5]. Traditional single-machine intelligent architectures face limitations when encountering new threats, such as GPS spoofing [6], collaborative network attacks [7], and sensor interference combinations, as well as difficulties in multisource data fusion, insufficient real-time response capabilities [8], and slow dynamic threat defense, all of which severely restrict the safety and reliability of UAV clusters in complex scenarios. When a UAV cluster experiences a cyberattack, the coordinated flight of the entire system is disrupted, which severely affects safety. Recently, numerous scholars have begun investigating how to ensure the safe and coordinated flight of swarmed aircraft under cyberattack conditions.

1.2. State of the Art

The cooperative control of UAV clusters can be divided into centralized control, decentralized control, and distributed control strategies [9]. Centralized control strategies can achieve global optimal control, but problems such as high communication load and poor formation robustness limit the scalability of drone swarms. Distributed control strategies require only local information exchange to coordinate swarms, reducing communication bandwidth requirements while maintaining high fault tolerance and swarm scalability. Decentralized control strategies do not require central controllers and can achieve only local optimization; however, such strategies have advantages such as modularity and swarm scalability. In addition to the general architecture, scholars have explored cluster security.

Raja et al. proposed a novel multilayer blockchain-assisted 6G Internet of Drones (MLB-IoD) ecosystem that enhances system resilience against attacks while providing efficient path planning through security controls and compliance mechanisms [10]. Karmakar et al. designed a blockchain-based distributed authentication mechanism for drone clusters [11]. Blockchain facilitates the storage of drone authentication information in immutable storage, while associated smart contracts provide a convenient access control model. Jangsher et al. proposed an efficient group secret key (GSK) protocol for secure communication in distributed drone clusters [12]. The proposed protocol uses network coding to generate cooperative information transmitted over the channel, which is independent of the generated keys. This provided a solution to ensure secure authentication for drone clusters. Viana et al. proposed a deep learning architecture for identifying attack behaviors in UAV communications in a 5G environment. This architecture can accurately identify attack behaviors under line-of-sight (LoS) and non-line-of-sight (NLoS) conditions, as well as random combinations of the two conditions, thereby increasing the security and reliability of UAV clusters in interference and complex communication scenarios [13]. Lopez et al. proposed a wireless mesh network security architecture for UAV cluster communications, comprehensively analyzed security vulnerabilities and threats from the physical layer to the application layer, and proposed corresponding defense strategies [14].

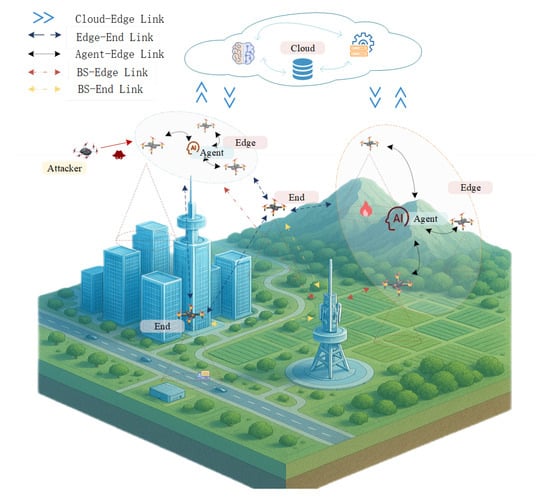

Because traditional UAV safety control systems typically rely on preset rules and algorithms, these methods face challenges in dynamic environments and have poor safety decision-making adaptability and coordination efficiency because of the difficulty of identifying complex and changing threats [15,16]. The introduction of large language models (LLMs) into UAV cluster safety compensates for the shortcomings of traditional methods in terms of adaptability to dynamic environments [17], coordinated and intelligent decision-making [18], resource utilization and allocation resources [19], and system robustness. Figure 1 shows a UAV cluster in an intelligent control collaboration scenario. Layered assistance from end-, edge-, and cloud-based LLMs increases the autonomous perception, understanding, and decision-making capabilities of the swarm, enabling it to better adapt to diverse application scenarios.

Figure 1.

Intelligent collaboration of UAV clusters.

1.3. Comparison of Related Work

Existing studies have proven the feasibility of practical application. Aikins et al. presented a case study demonstrating LLM support for up to 1000 drones operating in coordination, showcasing the potential capabilities of LLMs in handling large-scale cluster tasks [20]. Li et al. proposed optimizing UAV deployment and power control through LLMs to improve the anti-jamming capabilities of clusters in emergency communication scenarios and ensure the stability and security of communication links [21]. Han et al. proposed CoLLM, a distributed LLM collaborative reasoning framework designed for ground-centerless scenarios, to avoid the leakage of intelligent decisions when a single machine is compromised [22]. Zhu et al. proposed a Transformer-based UAV trajectory planning algorithm to quickly generate optimal trajectories, reduce data transmission and processing delays, and decrease the risk of data tampering or obsolescence, providing an efficient solution for secure data collection by UAV clusters in complex environments [23]. Yang et al. comprehensively analyzed the application of LLMs in UAV security and reported that LLMs can effectively improve the threat detection and response capabilities of UAV clusters in complex environments through multimodal data fusion and real-time decision-making capabilities, significantly increasing the security of clusters [17]. Emami et al. proposed an In-Context Learning (ICL) data collection scheduling system based on LLMs, which demonstrates outstanding performance in testing against jailbreak attacks, thereby ensuring communication security [24].

In addition, some scholars have combined LLMs with other technologies to achieve more efficient and secure UAV cluster collaboration control. Golan et al. embedded LLMs into a blockchain to enable online identification of new and complex threats in UAV communications without retraining [25]. On the basis of the contextual understanding capabilities of LLMs, they performed semantic-level anomaly detection on tamper-proof UAV traffic data stored on the blockchain, significantly reducing the number of false positives and false negatives. Piggott et al. proposed an adversarial chatbot based on LLMs that understands network protocols and launches man-in-the-middle attacks against communications between UAVs and ground control stations (GCSs), automatically generating simulated network packets [26]. This approach can be further explored to enhance the resilience of UAV clusters against attacks. Sezgin et al. also significantly improved the security decision-making capabilities of UAV clusters in complex environments by combining LLMs with RAG technology [27]. Javaid et al. analyzed the security application scenarios of LLMs in UAV clusters; clarified their core role in threat detection, command verification, and emergency response; and proposed an LLM-driven spectrum sensing and sharing mechanism that can identify interference sources in real time and dynamically switch channels to prevent cluster communications from being suppressed or deceived [18]. Zhou et al. combined large language models with Q-learning to effectively address safety issues in UAV cluster decision-making, scheduling, and optimization within unknown environments [28].

Table 1 summarizes research methodologies for UAV swarm security. However, current LLM architectures for UAV swarm security still face numerous challenges in multi-aircraft cooperative safety scenarios, as summarized in Table 2. Therefore, there remains a lack of an adaptive, resource-aware collaborative security framework capable of handling multisource data, dynamic threat situations, and resource-constrained environments within large-scale UAV swarms. Existing solutions often focus on isolated aspects such as authentication, intrusion detection, or trajectory planning, failing to integrate them into a unified, layered decision-making system spanning cloud, edge, and terminal devices.

Table 1.

Categorized summary of research methods in UAV cluster security.

Table 2.

Summary of existing challenges in UAV cluster security.

To address these challenges, an LLM architecture that is more suitable for UAV cluster scenarios is needed to identify threats and make decisions during multimachine collaborative operations. Considering edge collaboration applications is an important development trend in future 6G communications. This trend has been implemented in many scenarios, such as vehicle-to-everything (V2X), industrial control, and command cities, but practical applications with UAVs are lacking.

Therefore, this paper presents a security-oriented multimachine collaborative LLM-layered collaborative security architecture (LCSA). This architecture leverages a distributed data storage framework and resource-aware intelligent decision-making algorithms. In the LLM-LCSA framework, the MoEs mechanism is embedded within edge servers, a threat–expert dynamic correlation matrix is used, and an optimization model that considers expert recommendation costs and multidimensional resource consumption is constructed. Additionally, we incorporate slack variables to manage resource conflicts, design a multidimensional confidence evaluation mechanism, and implement a feedback adjustment module to achieve resource-aware intelligent decision-making.

- 1.

- We propose LLM-LCSA for secure multi-UAV collaboration. Through a cloud–edge–terminal collaborative computing architecture, LLM-LCSA integrates distributed data storage, sliding window aggregation, and data validity scoring mechanisms to achieve multilevel model collaborative inference. In comprehensive performance evaluations, all the components achieved excellent ratings.

- 2.

- An intelligent agent algorithm based on the MoEs was designed, implemented, and embedded within edge servers. Through the designed threat–expert dynamic correlation matrix and expert weight dynamic adjustment mechanism, the accuracy of the system in identifying complex dynamic threats and its dynamic adaptability significantly increased. Simulation experiments demonstrate that compared with traditional methods, the average recognition accuracy for multiple threat types increased by 7.92%.

- 3.

- A multi-objective optimization model under resource constraints was constructed to achieve resource-aware intelligent decision-making. This model comprehensively considers expert recommendation costs and multidimensional resource consumption constraints and develops an optimization solution strategy that incorporates slack variables. The simulation results demonstrate that compared with traditional methods, the system reduces the total response time by 44.52%, significantly improving resource utilization.

We compared LLM-LCSA with relevant research, as shown in Table 3. This paper features three key innovations and addresses the current challenges mentioned.

Table 3.

Comparison of different methods and their features.

- We propose a hierarchical collaborative security architecture that addresses the inefficiency of traditional simple-layered deployment models in processing multisource asynchronous spatiotemporal data fusion. This significantly enhances data processing efficiency, with simulation results validating the architecture’s effectiveness.

- We resolve the accuracy and adaptability limitations of traditional hybrid expert models when handling novel complex threats by introducing an online adaptive matrix. This enables real-time expert activation and continuous self-evolution.

- We design a resource-aware multi-objective optimization model to resolve the challenge of balancing decision quality with multidimensional resource consumption in resource-constrained edge environments. By incorporating slack variables and a multidimensional confidence mechanism, we ensure the system’s reliable performance and deployment capability under resource-limited conditions.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: In Section 2, the overall design of LLM-LCSA, a hierarchical collaborative security architecture, is introduced. In Section 3, the theoretical foundation, system modeling, and a hierarchical collaborative threat detection algorithm are designed. With the proposed system, a resource-aware intelligent decision optimization algorithm is proposed in Section 4. In Section 5, the simulation results are discussed, revealing the effectiveness of the proposed architecture and algorithms. The conclusions of the paper and directions for future research are presented in Section 6.

2. System Architecture Design

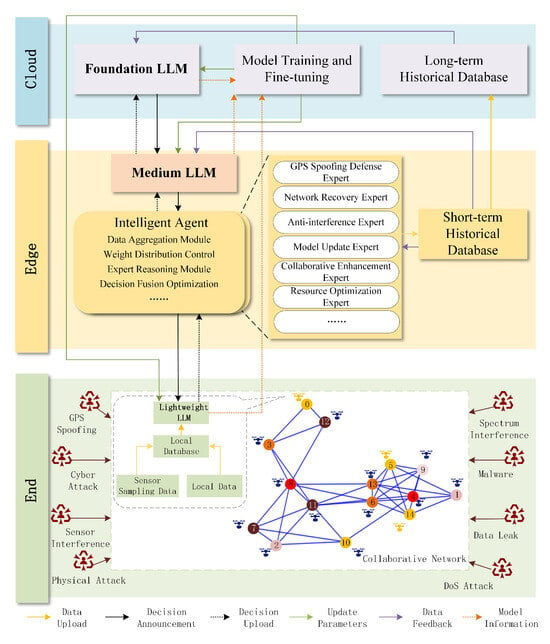

To mitigate the latency bottlenecks and static threat response deficiencies of centralized LLM deployment, this paper presents a hierarchical collaborative architecture, LLM-LCSA. Through the collaboration of a cloud–edge–end hierarchical model and an embedded intelligent agent decision-making mechanism, this architecture achieves efficient multimachine collaboration in security-critical scenarios. As shown in Figure 2, lightweight models are deployed on end devices, medium models are deployed on the edge server, and large models are deployed in the cloud. This architecture enables data acquisition, real-time processing, long-term forecasting, and safety mode analysis.

Figure 2.

Architecture of LLM-LCSA.

2.1. Cooperative Deployment of Layered Models

The basis of LLM-LCSA lies in the collaborative deployment of hierarchical models to fully exploit the advantages of different computing resources, enabling efficient data processing and decision support. The small-scale model deployed on the end device is responsible for real-time data collection and preliminary anomaly detection and is capable of quickly responding to changes in local sensor data, generating anomaly detection scores , and sending them to the edge device. The medium model deployed on the edge devices combines anomaly detection scores from multiple UAVs and short-term historical data features S to perform more accurate binary anomaly detection and calculate performance indicator vectors M. The large model deployed in the cloud focuses on long-term sequence prediction and large-scale security pattern analysis, generating long-term sequence prediction results T and large-scale security analysis results K. LLM-LCSA is also responsible for offline training and fine-tuning of the model, and it sends the updated model parameters to the edge and end devices.

Through this hierarchical model collaboration deployment, LLM-LCSA can fully exploit the real-time capabilities of the end, the computing power of the edge, and the global analysis capabilities of the cloud to optimize the entire process from data collection to decision support. The lightweight model on the end side can quickly respond to local data changes, the medium model on the edge side can process local data and make preliminary decisions, and the large model in the cloud can provide a global perspective and in-depth analysis. The three models collaborate to ensure the efficient coordination and intelligent decision-making of UAV clusters in complex environments.

2.2. Distributed Data Storage Architecture

To effectively process the massive, high-speed, heterogeneous data streams generated by UAV clusters, LLM-LCSA was designed with an innovative, distributed data storage architecture. Short-term and long-term history databases are used to store recent data fragments and global trend and pattern data, respectively.

The short-term history database is deployed on edge servers and stores data from the past few minutes to several tens of minutes, including statistical features such as anomaly frequency, mean, and variance. These data provide real-time contextual information for medium models at the edge, enabling rapid anomaly detection and decision support. The long-term history database is deployed in the cloud, storing data spanning hours, days, or even longer periods, including periodic trends and statistical analyses of historical anomaly patterns. These data provide a global perspective for large-scale models in the cloud, enabling long-term sequence prediction and large-scale security pattern analysis.

To better handle multisource asynchronous data, LLM-LCSA uses time window sliding aggregation and data validity scoring mechanisms at the edge layer. Time window sliding aggregation uses an exponentially weighted moving average method to assign higher weights to recent data, ensuring data timeliness. Data validity scoring is used to evaluate the recency of the data from each data source via a timeliness function. When a data source is temporarily unavailable, historical data prediction is performed in the edge layer to fill in the gaps, or a downgrade strategy is employed to ensure the completeness and reliability of the data. In addition, data fusion quality metrics are defined for the system. When the data fusion quality metrics fall below predefined thresholds, additional data requests are performed or the decision confidence threshold is increased to further optimize the data processing workflow.

This distributed data storage architecture not only addresses the problem of synchronizing and integrating multisource asynchronous data but also exploits the real-time data advantages of the end and edge, alleviating the bottlenecks of traditional centralized data processing models in UAV cluster scenarios and providing a solid data foundation for the safe coordination of UAV clusters.

2.3. Embedded Intelligent Agent Algorithm

Another core component of LLM-LCSA is the intelligent decision-making algorithm embedded within the edge server. This agent algorithm is based on the MoEs mechanism; integrates task decomposition, distribution, and decision fusion functions; and introduces domain expert knowledge. This algorithm can intelligently invoke the most relevant expert knowledge for decision-making on the basis of real-time threat situations.

The main modules of the agent algorithm include data aggregation, weight allocation and control, expert reasoning, decision fusion, feedback and iterative adjustment, and collaborative enhancement modules. The data aggregation module fuses data from different levels through mechanisms such as time stamp alignment and time window sliding aggregation to generate a unified feature vector. The weight allocation and control module dynamically adjusts the weights of each expert on the basis of the input features to ensure that the most relevant expert opinions are emphasized in different threat scenarios. The expert reasoning module allows each expert to output a recommended decision vector on the basis of their domain expertise, supporting the dynamic expansion and updating of the expert system. The decision fusion module optimizes decision vectors by defining cost functions and resource consumption models to ensure that task requirements are met while optimizing resource utilization efficiency. The feedback and iterative adjustment module uses a multidimensional confidence assessment mechanism to evaluate decision quality in real time and makes adaptive adjustments on the basis of feedback to ensure system robustness and adaptability. The collaborative enhancement module further supports hierarchical management and conflict negotiation for large-scale clusters, increasing the overall collaborative efficiency of the system.

Through embedded intelligent agent algorithms, LLM-LCSA not only achieves efficient multimachine coordination and intelligent decision-making but also dynamically adjusts decision-making strategies on the basis of real-time threat situations, significantly improving the ability of the system to respond to complex and new threats and providing powerful intelligent support for the safe coordination of UAV clusters.

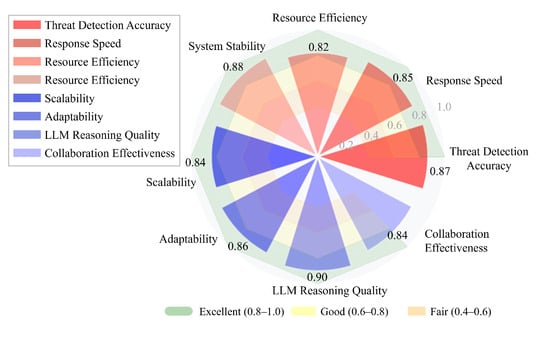

2.4. Performance Evaluation

We evaluated the overall performance of LLM-LCSA through a comprehensive set of metrics covering the threat detection accuracy, response latency, resource utilization, and system scalability. It establishes differentiated evaluation metrics tailored to the core functions of each component. All heterogeneous metrics undergo standardization and are weighted and aggregated based on their relative importance to the system’s overall performance. The results are normalized into a composite score ranging from 0 to 1, enabling consistent cross-component comparisons. The detailed experimental setup, evaluation criteria, and comparative results are presented in Section 5. As shown in Figure 3, all the metrics exceed 0.82, indicating excellent performance. LLM inference quality is its strongest aspect, with no obvious performance shortcomings, although resource efficiency could still be improved.

Figure 3.

Comprehensive performance dashboard of LLM-LCSA.

LLM-LCSA effectively addresses the shortcomings of existing UAV systems in areas such as multi-aircraft collaboration mechanisms, data processing and storage, dynamic threat response, resource-constrained decision optimization, and system scalability and adaptability. LLM-LCSA provides an efficient, intelligent, and scalable system solution for the safe and coordinated operation of UAV swarms.

3. System Model and Analysis

The LLM-LCSA approach studied in this paper is aimed at a cluster system composed of N UAVs that perform cooperative tasks in complex environments with potential dynamic security threats. The primary elements of the system model are defined in Appendix A Table A1:

3.1. System Models

3.1.1. Network Topography

The cluster uses a distributed communication topology. Local information is exchanged between UAV nodes via wireless links. Let be the communication graph, where is the node set and E is the edge set, indicating that direct communication is possible between nodes. The normalized communication distance parameter is represented as , and there is an edge between nodes only when their Euclidean distance is . Edge servers are deployed at specific locations or by some UAVs and are responsible for data aggregation and processing in local areas. The cloud provides global computing and storage support.

3.1.2. Threat Model

The system faces M possible threat types . Threats may occur independently or in combination and are dynamic and covert in nature. The scope of threat impact can be a single machine, a local cluster, or global.

3.1.3. Data Processing Flow

End: Each UAV is equipped with a lightweight LLM, which is responsible for real-time collection, preprocessing, and preliminary anomaly detection of local sensor data, generating preliminary anomaly scores .

Edge: Medium LLMs and intelligent agents are implemented on edge servers. Edge servers receive and local data sent by UAVs within their jurisdiction, combine them with recent statistical features stored in a short-term historical database, perform threat classification and local situational awareness, and generate performance metric vectors and preliminary decision recommendations.

Cloud: A large-scale LLM is implemented in the cloud. Aggregated information is received from all edge nodes and global trend and pattern data stored in the long-term historical database . Long-term prediction and large-scale security pattern analysis are performed to obtain security labels . Offline model training, fine-tuning, and parameter deployment are all performed in the cloud.

3.1.4. Resource Constraints

The system involves eight types of key resources, and the system-available resource vector is represented as . to represent the computing resources, communication bandwidth, data storage, model storage, power consumption limits, RAM capacity, connection quality requirements, and sensor resources, respectively.

Under the constraints of resource availability, the system needs to generate the optimal collaborative decision vector corresponding to different control parameters. The implementation of each decision component generates resource consumption , which represents the demand for the k-th resource when decision is implemented as follows:

This balances safety, task performance, resource efficiency, real-time performance, robustness, and adaptability.

End constraints: The end available resource vector is represented as

Edge-side constraints: The edge server needs to serve UAVs, with the following constraints:

Expert system MoEs constraint:

where represents the proportion of computing resources that can be used by the expert system.

Global resource balancing constraint:

Load balancing constraint:

Time coupling constraint: The time-related nature of resource consumption is considered as follows:

where represents the upper limit of resource utilization.

3.2. Feature Vectors and Data Freshness

To ensure data timeliness, an agent uses the most recent data within a specific time window when aggregating data from various sources. Let be the aggregated feature vector at time t, which consists of the following components:

where represents the end anomaly detection score, represents the edge model performance vector, represents short-term historical features, represents long-term historical features, represents cloud-based time series prediction, and represents safety analysis labels.

The validity score of data u at time t is calculated as follows:

where represents the control decay rate and denotes the half-life of the data.

For short-term time series data , the exponential weighted moving average method is used as follows:

where W represents the sliding window size, which is adjusted adaptively by the data sampling rate, and denotes the data retention ratio:

3.3. Threat–Expert Association Matrix

The threat type space , the set of experts , and the association matrix satisfy the following:

where M represents the number of possible threat types, denotes the number of experts, and represents the degree of association between threat type i and expert j.

Extracting the threat features yields the following:

where represents the ReLU activation function, denotes the weight matrix, and represents the bias vector used for decision boundary adjustment.

The importance weights of each expert are calculated through the control module as follows:

where represents the basic relevance score of expert i, indicating the degree of matching between input feature v and expert i.

On the basis of the threat-based expert weight adjustment, the threat probability is multiplied by the correlation matrix to correct the control module output:

where represents the probability of each threat type, denotes the threat space transformation matrix, and represents the parameter regulating the intensity of threat perception. When , only basic gate control is used; when , the system relies entirely on threat perception. denotes the correlation matrix, which represents the correlation between threat type j and expert i.

The final expert weight is calculated as follows:

On the basis of decision effect feedback, the association matrix is regularly updated as follows:

where represents the learning rate and denotes the quantitative score of decision effectiveness.

3.4. Expert Reasoning Module

The decision variable is a decision vector , where each component corresponds to a different control parameter (such as the evacuation intensity , link switching , or anti-interference ). Each expert outputs their recommended decision vector on the basis of the input v. Experts can provide nonzero recommendation values for one or more decision components on the basis of their domain expertise.

The capability assessment function for newly added experts is defined as follows:

where represents the test scenario set, denotes the reference decision vector, which represents the ideal decision recognized by the system in a given input feature scenario, and represents the similarity score between the expert recommendation and the reference decision. When a new expert registers, the system uses a conservative strategy to gradually increase the expert’s influence as follows:

where represents the growth factor and denotes the upper limit of the expert weight, which gradually increases with the ability assessment score.

Among experts with similar functions, the resource allocation is dynamically adjusted on the basis of historical performance as follows:

where represents the proportion of computing resources obtained by expert i, denotes their historical performance metric, and controls the intensity of competition.

Algorithm 1 demonstrates a hierarchical collaborative threat detection algorithm that achieves three-tiered collaborative detection at the end (real-time), edge (aggregation), and cloud (global) levels. At the end layer, a lightweight LLM generates anomaly scores in real time. At the edge layer, a medium LLM aggregates short-term historical data and performs anomaly classification. At the cloud layer, a large-scale temporal LLM analyzes long-term patterns and generates security labels. Time window sliding aggregation and data freshness decay functions ensure the real-time validity of the data.

| Algorithm 1: Layered collaborative threat detection algorithm. |

|

3.5. Complexity Analysis

N represents the number of UAVs in the UAV cluster, and the complexity of end processing is expressed as follows: ; data reception ; time window sliding aggregation ; data freshness calculation ; feature vector construction ; edge-side medium model inference O(); and cloud-side large-scale model processing (time-series prediction: , large-scale model security analysis: , and database update: .

When and no cloud processing is triggered, ; when and cloud processing is triggered, T.

4. Intelligent Decision Optimization

The threat detection algorithm described in Section 3 provides essential input for subsequent decision-making phases. However, generating optimal response strategies requires consideration of the stringent resource constraints inherent to both the end and edge computing environments of the UAV. We model the decision optimization problem as a constrained cost minimization problem and establish a closed-loop optimization cycle. Specifically, the situational awareness feature vectors generated by each layer of the LLM serve as the unified input for subsequent optimization. Not only do they dynamically adjust the expert weights through the threat–expert matrix, but they also serve as key parameters injected into the resource-aware multi-objective optimization model to generate the optimal decision . The execution effectiveness of the decision is monitored in real time and quantified as a feedback signal. These signals are used to update the expert system and for targeted fine-tuning of the LLM, thereby forming a complete closed loop of “perception–decision–feedback–learning” that drives the system’s continuous evolution.

4.1. Resource-Constrained Decision Optimization

The cost function of expert i is defined as follows:

where represents the decision vector, denotes the weighted deviation from its recommendation, is the recommendation value of expert i for decision component j, and represents the sensitivity weight of expert i to decision component j (unrelated components ).

The system-available resource vector is defined as , where represents the available amount of the k-th resource, and the resource constraint function is constructed as follows:

The overall cost function is constructed as follows:

where represents the weighting factor for resource efficiency, which can be dynamically adjusted according to the current load of the system.

The resource efficiency targets are incorporated into optimization problems and converted to a multi-objective optimization function as follows:

When resource constraints conflict, the slack variables are introduced as follows:

The KKT conditions yield a closed-form solution:

where represents the Lagrange multiplier. The computational complexity depends primarily on n and K, neither of which increase significantly with the expansion of the UAV cluster scale within the system, ensuring the algorithm’s real-time capability under large-scale constraints.

4.2. Expert Consensus Rating

The consensus on the evaluation of expert opinions is as follows:

where is the weight of the i-th expert. The higher the consistency is, the closer the score is to 1.

The decision-making effects of similar historical scenarios are compared as follows:

where H represents the historical decision record, which contains feature vectors , decisions , and effects ; calculates the similarity between the current feature vector and the historical record; and assesses the success of historical decisions.

The decision effectiveness in a lightweight simulation environment is quickly confirmed as follows:

where represents the ith KPI value resulting from decision in the simulation environment and and denote the predefined best and worst values, respectively.

The uncertainty of the current input data is assessed as follows:

where represents the estimated variance of the ith input vector v and denotes the scaling factor.

Multidimensional weighted integration is performed as follows:

where weights can be dynamically adjusted through reinforcement learning and other methods to optimize long-term decision quality.

Thresholds are dynamically adjusted on the basis of the urgency of the situation as follows:

where represents the base threshold, controls the degree to which the threshold is lowered in an emergency, and denotes the current assessment of the urgency of the situation.

When the system involves many UAVs, a collaborative enhancement module is used to achieve more efficient decision-making and execution. UAVs are grouped into multiple clusters , with edge servers and agents set up in each cluster . The clusters share summary information through a high-level coordination mechanism:

where represents a summary of information shared by cluster i, including key status, decision intent, and uncertainty assessment. When there is a conflict between the decisions of adjacent clusters, a negotiation mechanism is triggered as follows:

The agent sends the final optimal decision vector to each relevant UAV, which then performs the corresponding operation (evacuation, communication switching, anti-interference, etc.) on the basis of and feeds back the execution results to the system.

4.3. Multi-Expert Collaborative Safety Decision-Making Algorithm

Algorithm 2 shows the multi-expert collaborative adaptive security decision-making framework. This framework extracts threat features, calculates threat probability distributions, and then dynamically adjusts expert weights on the basis of threat probabilities and resource matrices. Next, this framework optimizes and generates the optimal decision vector under resource constraints and integrates four dimensions—the consensus degree, historical matching, simulation verification, and uncertainty—for comprehensive confidence assessment. This framework dynamically adjusts the execution threshold according to resource scarcity to achieve adaptive decision execution.

| Algorithm 2: Dynamic expert decision algorithm. |

|

4.4. Complexity and Deployment Analysis

K represents the number of resource types, H denotes the number of historical decision records, n indicates the dimension of the decision vector, and d represents the dimension of the input feature vector. The complexity of the threat feature extraction matrix multiplication is ; the complexity of the threat perception weight correction is ; the complexity of the expert decision generation is ; the complexity of the resource-constrained decision optimization is ; and the complexity of the multidimensional confidence assessment is Thus, the overall complexity is . Considering that the number of experts and the number of decision dimensions are both much smaller than those of the historical data, this can be simplified to . Therefore, the complexity of this algorithm is related primarily to the number of historical data records, which can be adjusted according to actual conditions.

Further consideration must be given to the challenges encountered in actual deployment, including the system’s inherent robustness and communication latency, the physical limitations of the UAV platform, and data privacy. These factors may impact the system’s real-time performance and reliability. To address these challenges and ensure system security in real-world environments, LLM-LCSA processes terminal data through sliding window aggregation and data validity scoring. Feature vectors contain only statistical characteristics rather than raw data, thereby reducing privacy leakage risks. The resource-aware decision model supports anti-interference strategies such as dynamic channel switching and spread spectrum techniques. Through real-time threat identification enabled by end–edge–cloud collaboration and the dynamic activation of expert models via the MoEs, optimal response decisions are rapidly generated and executed. Furthermore, slack variables introduced in the multi-objective optimization model effectively mitigate security vulnerabilities potentially caused by resource conflicts. The feedback module, based on multidimensional confidence assessment, continuously optimizes decision strategies, collectively ensuring the system’s security and privacy protection capabilities in complex real-world environments.

To assess practical deployment feasibility, we evaluated computational resource requirements for agents at each level: lightweight LLMs can be deployed on embedded platforms like NVIDIA Jetson Orin, and medium LLMs and hybrid expert systems at the edge can leverage edge computing nodes such as NVIDIA A100, while foundational cloud-based LLMs can be supported by mainstream AI servers. Analysis indicates that with current 5G/6G networks and commercial hardware, the LLM-LCSA architecture demonstrates high engineering feasibility, laying the groundwork for subsequent deployment and application within actual UAV clusters.

5. Simulation and Results

The simulation experiment was conducted using Pycharm 2022.1, and the algorithms were implemented in Python 3.8.5. The programs were run on a server with a Windows 11 operating system equipped with 8.00 GB of RAM and a 13th Gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i9-13900H 2.60 GHz processor(Intel Corporation; Santa Clara, California, USA). The system supports the detection of eight threat types (GPS spoofing, network attack, sensor jamming, physical attack, spectrum jamming, malware, data leakage, and DoS attack) and the normal state. Table 4 shows the LLM-LCSA parameter configuration. Table 5 shows the experimental parameter configuration.

Table 4.

LLM-LCSA parameter configuration.

Table 5.

Simulation parameter configuration.

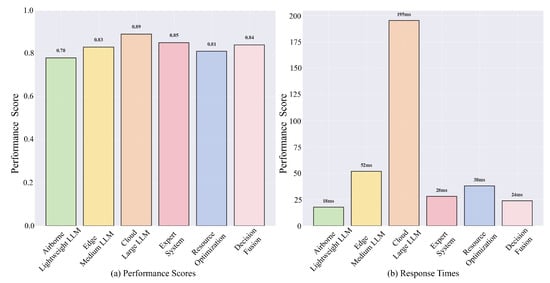

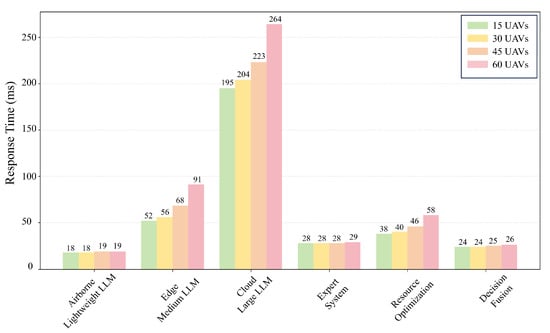

A performance analysis of the LLM-LCSA components, including the end-based LLM, edge-based LLM, cloud-based LLM, expert system, resource optimization process, and decision fusion process, is shown in Figure 4. The performance scores of each LLM component are shown in Figure 4a, and the response times of each component are shown in Figure 4b. The cloud-based large LLM has the best performance, with its value reaching 0.89; however, this component has the highest latency of 195 measurements. The end lightweight LLM has the lowest latency, reducing the dependence on the cloud and ensuring real-time system performance. The three-layer architecture achieves a balance between optimal performance and real-time efficiency.

Figure 4.

Component performance analysis of LLM-LCSA.

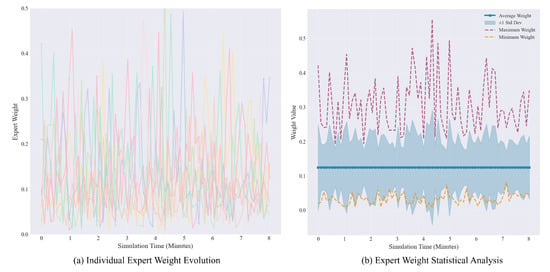

The changes in expert weights enhanced by the LLM are shown in Figure 5. The dynamic evolution process, where expert weights are dynamically adjusted on the basis of threat types, is shown in Figure 5a. All expert weights fluctuate between 0 and 0.5, indicating that the system uses a balanced design to prevent any single expert from dominating the decision-making process. During the initial learning phase, the weight distribution is relatively even. In the middle phase, specialization begins, with the weight of the GPS defense expert significantly increasing during GPS attacks and the weight of the comprehensive coordination expert increasing during composite threats. This intelligent collaboration mechanism enables real-time adjustment of weights on the basis of threat types, as well as knowledge sharing and updating among experts. A statistical analysis of the weights is shown in Figure 5b, which fluctuates by approximately 0.125 overall, consistent with the expected equal distribution among the eight experts. The slight fluctuations indicate that the system can make fine-tuning adjustments based on threat conditions; the standard deviation bandwidth of approximately ±0.05∼0.08 indicates that the dispersion of expert weights is moderate, allowing for differentiation (to respond to different threats) without excessive dispersion; the maximum weight peak reaches approximately 0.45∼0.5, occurring at T = 4∼5 min, corresponding to major threat events, indicating that the system can concentrate decision-making weights at critical moments; and the minimum weight remains in the range of 0.02∼0.05, ensuring that even experts with the lowest priority maintain basic influence, reflecting a fault-tolerant design philosophy.

Figure 5.

Changes in expert weights.

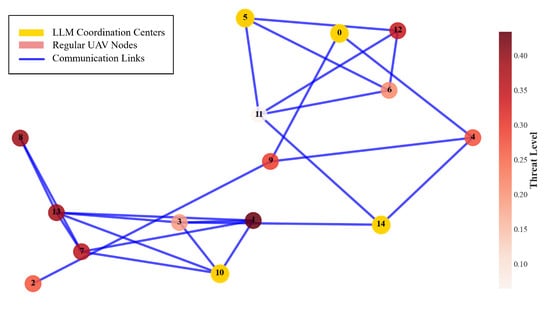

The propagation of threats in a UAV network and the response of the LLMs are shown in Figure 6. A distance-based geometric model was constructed on the basis of 15 UAVs. For key propagation paths, only 1∼2 hops are needed from the high-altitude node to the neighboring cluster, 3∼4 hops are needed for cross-cluster connections, and 4∼5 hops are needed for the network edge node. The LLM acts as a coordination hub at nodes 0, 5, 10, and 14 and is responsible for threat information aggregation and response coordination, implementing a defense strategy that includes early response during low-threat conditions, communication isolation of high-threat nodes, and collaborative protection of adjacent nodes.

Figure 6.

UAV network threat propagation and LLM-coordinated response.

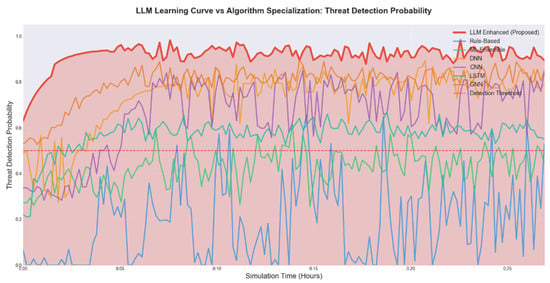

Figure 7 shows a comparison of the learning efficiency and performance of various algorithms. The LLM-LCSA curve has the steepest slope, indicating that it adapts quickly to new threat patterns. Traditional methods learn more slowly and encounter learning bottlenecks in the later stages. Owing to the diverse nature of threats, a single algorithm cannot accurately identify them. LLM-LCSA introduces a hybrid expert model, where multiple LLM components work together to improve decision-making and recognition capabilities for different threats.

Figure 7.

Learning curve and performance comparison.

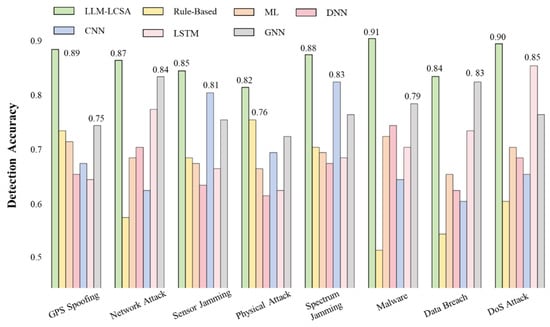

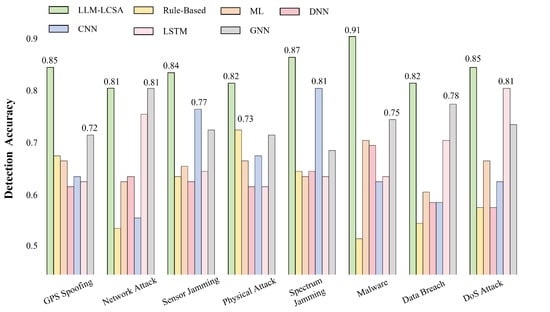

As shown in Figure 8, LLM-LCSA consistently outperforms all the baseline methods, indicating its robustness and generalizability. The architecture has significant advantages in the detection of complex threats, achieving a 15.2% improvement over the GNN baselines in malware detection and an 18.7% improvement against GPT spoofing. This is attributed to its effective fusion of multisource data and expert knowledge. Furthermore, LLM-LCSA maintains an average lead of 5.4% in identifying simpler threats, such as sensor jamming and spectrum jamming, which are typically dominated by CNN-based approaches. Across various attack scenarios, LLM-LCSA outperforms the best algorithm in the comparison set by an average of 7.92%, confirming the effectiveness of our hierarchical collaborative design.

Figure 8.

Threat type detection accuracy.

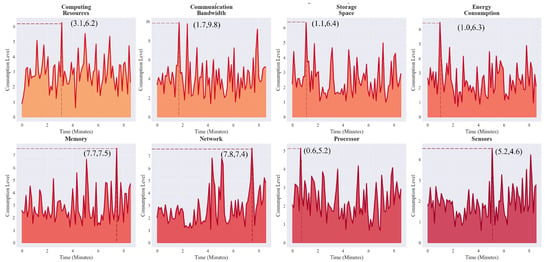

The usage of eight key resources (computing resources, communication bandwidth, data and model storage, power consumption, RAM usage, connection quality and latency, dedicated processing units, and sensor resources) is shown in Figure 9. Because the model requires information updates and exchanges with external systems, its demand for communication resources is greater than that for other critical resources. However, this process occurs only around the 1.7 min mark, allowing for staggered scheduling with other critical resources. At this time, no other resources experience peak usage, thereby achieving load balancing and avoiding single-point resource bottlenecks.

Figure 9.

Resource consumption analysis.

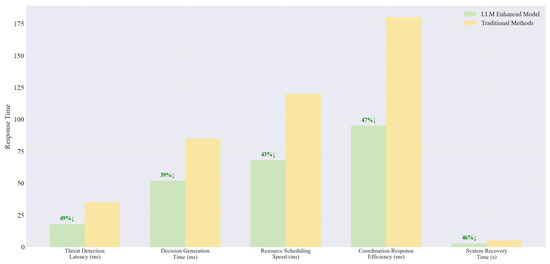

To highlight the superiority of this architecture in terms of collaborative response at the system level, we also performed weighted collaboration on other methods, selecting enterprise usage rule systems, commonly used academic ML systems, and distributed systems, and assigning them weights of 0.4, 0.35, and 0.25, respectively, to obtain a collaborative architecture representing traditional methods.

The response latency comparison is shown in Figure 10. The five key response stages are as follows: from threat emergence to detection confirmation, from detection to decision output, resource allocation execution time, multinode collaborative response time, and from attack to system recovery. Compared with traditional methods, LLM-LCSA achieves a threat detection delay of 18 ms vs. 35 ms (a 49% reduction), a decision generation time of 52 ms vs. 85 ms, a resource scheduling speed of 68 ms vs. 120 ms, a collaborative response time of 95 ms vs. 180 ms, a 47% increase in efficiency, a 46% reduction in system recovery time, and a 44.52% reduction in total time. Therefore, LLM-LCSA achieves multilayer parallel computing, enables trend-based proactive preparation, and reduces the response time.

Figure 10.

Response latency comparison.

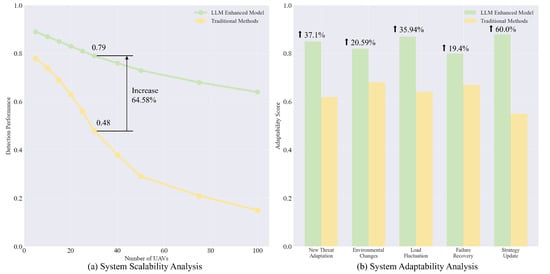

The results of the scalability and adaptability analysis are shown in Figure 11. The performance of traditional methods is compared with that of our architecture as the number of UAVs increases. The performance curve of LLM-LCSA declines slowly, whereas that of the traditional methods decreases sharply. When the number of UAVs reaches 30, the gap in performance increases significantly. For different adaptation scenarios, LLM-LCSA achieves higher scores. Owing to its ability to continuously learn new threat patterns, it achieves superior performance in strategy updates.

Figure 11.

Scalability and adaptability analysis.

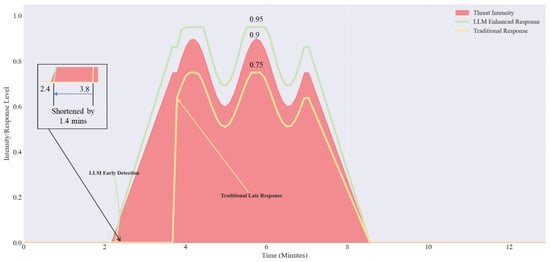

The results of the threat response timing analysis are shown in Figure 12. The experiment included 120 time steps, covering a time window of approximately 13 min, with each time step representing approximately 6.5 s. The analysis shows that the threat appeared at 130 s, and at 143 s, LLM-LCSA began its improved response, with the peak response intensity reaching 105.5% of the threat’s peak intensity. The response covered the entire period from the appearance of the threat to its disappearance, closely matching the evolution curve of the threat. Traditional methods did not begin responding until 97.5 time steps after the threat appeared (approximately 1.4 min later than LLM-LCSA), resulting in delays and insufficient response intensity. Therefore, LLM-LCSA has threat warning capabilities, achieves more precise response intensity, and can fully meet the requirements of threat management across the entire lifecycle.

Figure 12.

Threat response time series analysis.

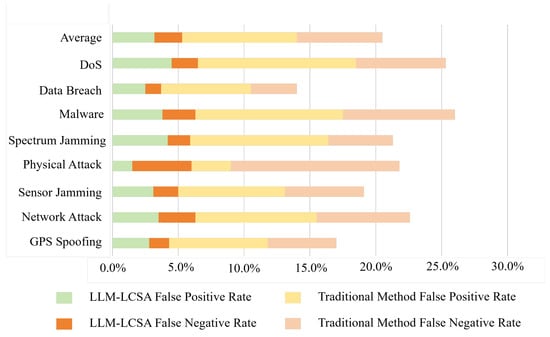

To comprehensively evaluate the reliability of the LLM-LCSA, we further analyzed its false positive rate and false negative rate. The false positive rate reflects how frequently the system misclassifies normal behavior as a threat, while the false negative rate reflects the proportion of genuine threats that the system fails to identify. As shown in Figure 13, the LLM-LCSA architecture achieved significantly lower false positive and false negative rates than traditional methods across all eight threat types. Specifically, the LLM-LCSA achieves an average false positive rate of 3.2% and an average false negative rate of 2.1%. Compared with traditional methods (false positive rate: 8.7%, false negative rate: 6.5%), these results represent relative reductions of 63.2% and 67.7%, respectively. Thus, this outcome fully demonstrates the LLM-LCSA’s balanced approach between precision and completeness in terms of threat detection.

Figure 13.

False positive rate and false negative rate analysis.

To validate the scalability of the LLM-LCSA, we incrementally increased the number of UAVs to 30, 45, and 60. Figure 14 shows the response times of each component. As the scale of UAV increases, the response time of cloud-based models grows the fastest, yet it remains within a satisfactory performance range. The lightweight LLM module, expert system module, and decision fusion module remained virtually unaffected, with response time increases under 2 ms. This confirms that even as the UAV fleet expands, the system maintains real-time responsiveness by generating minimal latency.

Figure 14.

System response times at different UAV scales.

Figure 15 shows the accuracy of different algorithms for various threats when the number of UAVs reaches 60. It can be observed that as the scale of UAV increases, the threat detection accuracy of LLM-LCSA does not exhibit significant changes. In contrast, the baseline method shows a noticeable decline in performance.

Figure 15.

Threat type detection accuracy (UAV = 16).

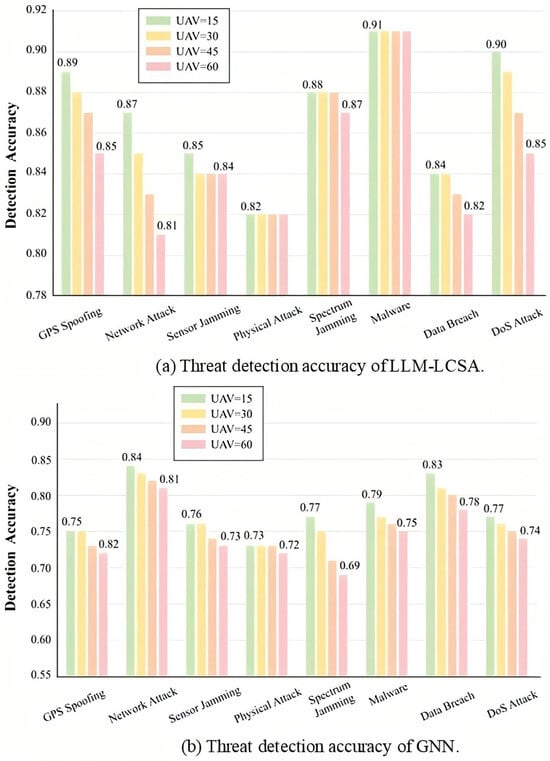

We selected GNN, which demonstrated superior performance among the comparison algorithms, for contrast analysis. We examined its accuracy trends alongside LLM-LCSA across varying numbers of UAVs, as shown in the Figure 16. Physical attacks typically result in severe consequences, are relatively simple to detect, and their accuracy remains largely unaffected by variations in UAV size. For network attacks, attack sources can propagate through multiple paths. Even a single attack easily identifiable in small networks may evolve into a difficult-to-track “multi-point coordinated attack” in large networks. Consequently, as the number of UAV nodes increases, the accuracy of network attack detection algorithms generally declines. However, LLM-LCSA maintains an accuracy rate above 80%, demonstrating strong robustness. Although GNN methods are theoretically applicable to networked systems, their performance also degrades when handling large-scale, high-density graph structures due to computational complexity issues. Notably, despite this performance decline, LLM-LCSA maintains the highest absolute accuracy among all methods across different scales. Its performance degradation is relatively mild, far less severe than that observed in baseline methods.

Figure 16.

Threat detection accuracy of LLM-LCSA and GNN.

To situate this research within the broader context of large-scale parallel and clustered systems, we compare it with advanced work in the field of cluster robotics to establish its position within large-scale parallel systems. Yasser et al. maximized task allocation efficiency by optimizing the communication topology within the cluster (CDTA-CL/DL), focusing on optimizing information flow paths [40]. This study addresses the unique security challenges of UAV clusters by proposing the LLM-LCSA architecture, shifting its focus to optimizing cognitive and decision-making processes. We deploy LLMs and MoEs mechanisms through a cloud–edge–end layered architecture, dynamically scheduling expert knowledge to counter complex threats while explicitly modeling resource constraints in decision-making. Thus, for well-defined tasks, communication optimization is the preferred approach; whereas for high-uncertainty problems like security, enhancing the system’s cognitive intelligence is essential. Despite divergent approaches, both validate a core principle: efficient parallel systems hinge on explicit trade-offs between performance and resources within decentralized coordination mechanisms. Our work demonstrates that this principle extends from communication layers to AI decision-making layers, further validating LLM-LCSA’s value in generalized parallel intelligent systems.

6. Conclusions

In response to the challenges faced by traditional methods in multimachine coordination safety for UAV clusters, including dynamic threat generalization, heterogeneous data fusion difficulties, and resource-constrained decision-making latency, this paper presents LLM-LCSA for multimachine coordination safety. Through cloud–edge–end coordinated deployment and intelligent agent decision-making mechanisms, the proposed framework achieves an efficient threat response. The main contributions of this study are as follows.

We propose the LLM-LCSA model, which integrates short-term and long-term historical databases through a sliding window aggregation mechanism to optimize the efficiency of multisource asynchronous data fusion. All the components achieve excellent performance scores. Additionally, we introduce hybrid expert-based intelligent agents and design a hierarchical collaborative threat detection algorithm, achieving an average 7.92% improvement in threat identification accuracy over traditional methods. With respect to resource-constrained environments, we design a multi-objective optimization model balancing resource consumption and performance, effectively reducing the communication load and decision latency. The simulation results demonstrate a 44.52% reduction in total decision time compared with traditional methods. The load balancing strategy successfully avoids single resource bottlenecks, significantly improving resource utilization.

This paper provides a new solution for the collaborative security of UAV clusters. Future research will build upon this foundation to enhance the practicality and scalability of the LLM-LCSA. Key directions include investigating lightweight models for physical-layer attack detection, developing a cross-cluster federated learning framework for privacy-preserving collaborative training, and validating the system real-time performance in integrated 6G network scenarios, such as high-security smart factories, low-latency smart cities, and data-sharing smart logistics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Z. and X.H.; methodology, J.Z. and X.H.; software, H.S. and Z.Y.; formal analysis, H.S. and H.D.; investigation, H.S., Z.Y., H.D. and Y.Z.; data curation, H.S., Z.Y. and H.D.; writing—original draft preparation, H.S. and Z.Y.; writing—review and editing, H.S. and H.D.; visualization, Z.Y. and Y.Z.; supervision, J.Z. and X.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China under Grant 2024YFE0200300, the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 92367201 and No. 62371039), and BIT Research and Innovation Promoting Project (Grant No. 2024YCXY027).

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in GitHub at https://github.com/cakesheep/LLM-LCSA-LLM-for-Collaborative-Control-and-Decision-Optimization-in-UAV-Cluster-Security (accessed on 1 November 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BS | Base station |

| CPU | Central processing unit |

| DoS | Denial of service |

| GCS | Ground control station |

| GPS | Global positioning system |

| GSK | Group secret key |

| IAB | Integrated access and backhaul |

| KKT | Karush–Kuhn–Tucker |

| LLM | Large language model |

| LoS | Line-of-sight |

| MoEs | Mixture of experts |

| NLoS | Non-line-of-sight |

| RAG | Retrieval-augmented generation |

| RAM | Random access memory |

| SDN | Software-defined networking |

| UAV | Unmanned aerial vehicle |

| V2X | Vehicle-to-everything |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Notation.

Table A1.

Notation.

| Symbol | Description |

|---|---|

| E | Set of communication links. |

| G | Communication graph. |

| Security pattern analysis label. | |

| Long-term historical features. | |

| M | Number of threat types. |

| N | Number of UAVs. |

| R | System available resource vector. |

| Short-term historical features. | |

| Cloud-based time series prediction. | |

| Set of threat types. | |

| V | Set of UAV nodes. |

| Set of experts. | |

| Resource consumption for resource k. | |

| Decision vector from expert i. | |

| Normalized communication distance. | |

| Overall optimization objective function. | |

| Base relevance score of expert i. | |

| Cost function for expert i. | |

| Probability of threat type j. | |

| Aggregated feature vector. | |

| Dynamic weight of expert i. | |

| x | Decision vector to be optimized. |

| Optimized decision vector. | |

| Slack variable for resource k. |

References

- Boroujeni, S.P.H.; Razi, A.; Khoshdel, S.; Afghah, F.; Coen, J.L.; O’Neill, L.; Fule, P.; Watts, A.; Kokolakis, N.M.T.; Vamvoudakis, K.G. A comprehensive survey of research towards AI-enabled unmanned aerial systems in pre-, active-, and post-wildfire management. Inf. Fusion 2024, 108, 102369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahiyoon, S.A.; Ren, Z.; Wei, P.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Xu, J.; Yan, X.; Yuan, H. Recent Development Trends in Plant Protection UAVs: A Journey from Conventional Practices to Cutting-Edge Technologies—A Comprehensive Review. Drones 2024, 8, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendu, B.; Mbuli, N. State-of-the-Art Review on the Application of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) in Power Line Inspections: Current Innovations, Trends, and Future Prospects. Drones 2025, 9, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betti Sorbelli, F. UAV-Based Delivery Systems: A Systematic Review, Current Trends, and Research Challenges. ACM J. Auton. Transport. Syst. 2024, 1, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Yi, L.; Ning, Z.; Guo, L.; Yu, F.R.; Guo, S. A Survey on Security of UAV Swarm Networks: Attacks and Countermeasures. ACM Comput. Surv. 2025, 57, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerns, A.J.; Shepard, D.P.; Bhatti, J.A.; Humphreys, T.E. Unmanned Aircraft Capture and Control Via GPS Spoofing. J. Field Robot. 2014, 31, 617–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y.; Kim, J.; Duguma, D.G.; Astillo, P.V.; You, I.; Pau, G. Drone Secure Communication Protocol for Future Sensitive Applications in Military Zone. Sensors 2021, 21, 2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, S.N.; Manickam, S.; Zia, S.S.; Abro, A.A.; Obaidat, M.; Uddin, M.; Abdelhaq, M.; Alsaqour, R. IoT empowered smart cybersecurity framework for intrusion detection in internet of drones. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 18422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.H.; Lai, S.; Wang, K.; Chen, B.M. Cooperative control of multiple unmanned aerial systems for heavy duty carrying. Annu. Rev. Control 2018, 46, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, G.; Senthivel, S.G.; Balaganesh, S.; Rajakumar, B.R.; Ravichandran, V.; Guizani, M. MLB-IoD: Multi Layered Blockchain Assisted 6G Internet of Drones Ecosystem. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 2511–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, R.; Kaddoum, G.; Akhrif, O. A Blockchain-Based Distributed and Intelligent Clustering-Enabled Authentication Protocol for UAV Swarms. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2024, 23, 6178–6195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangsher, S.; Al-Dweik, A.; Iraqi, Y.; Pandey, A.; Giacalone, J.P. Group Secret Key Generation Using Physical Layer Security for UAV Swarm Communications. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2023, 59, 8550–8564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, J.; Farkhari, H.; Sebastião, P.; Campos, L.M.; Koutlia, K.; Bojovic, B.; Lagén, S.; Dinis, R. Deep Attention Recognition for Attack Identification in 5G UAV Scenarios: Novel Architecture and End-to-End Evaluation. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 73, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, M.A.; Baddeley, M.; Lunardi, W.T.; Pandey, A.; Giacalone, J.P. Towards Secure Wireless Mesh Networks for UAV Swarm Connectivity: Current Threats, Research, and Opportunities. In Proceedings of the 2021 17th International Conference on Distributed Computing in Sensor Systems (DCOSS), Pafos, Cyprus, 14–16 July 2021; pp. 319–326. [Google Scholar]

- Jalil Hadi, H.; Cao, Y.; Li, S.; Hu, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, S. Real-Time Collaborative Intrusion Detection System in UAV Networks Using Deep Learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 33371–33391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, H.J.; Cao, Y.; Khan, M.K.; Ahmad, N.; Hu, Y.; Fu, C. UAV-NIDD: A Dynamic Dataset for Cybersecurity and Intrusion Detection in UAV Networks. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2025, 12, 2739–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, J.; Yang, Y.; Jia, Y.; Song, H.; Lv, T.; Sun, Q.; An, J. AI-Driven Safety and Security for UAVs: From Machine Learning to Large Language Models. Drones 2025, 9, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, S.; Fahim, H.; He, B.; Saeed, N. Large Language Models for UAVs: Current State and Pathways to the Future. IEEE Open J. Veh. Technol. 2024, 5, 1166–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, W.; Zhou, F. Enhancing 6G IoT Communications: UAV Relayed Satellite D2D with Large Language Model Optimization. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2025, 63, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aikins, G.; Dao, M.P.; Moukpe, K.J.; Eskridge, T.C.; Nguyen, K.D. LEVIOSA: Natural Language-Based Uncrewed Aerial Vehicle Trajectory Generation. Electronics 2024, 13, 4508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xiao, M.; Wang, K.; Kim, D.I.; Debbah, M. Large Language Model Based Multi-Objective Optimization for Integrated Sensing and Communications in UAV Networks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.05062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Su, J. SwarmChain: Collaborative LLM Inference for UAV Swarm Control. IEEE Internet Things Mag. 2025, 8, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Bedeer, E.; Nguyen, H.H.; Barton, R.; Gao, Z. UAV Trajectory Planning for AoI-Minimal Data Collection in UAV-Aided IoT Networks by Transformer. IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun. 2023, 22, 1343–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami, Y.; Zhou, H.; Nabavirazani, S.; Almeida, L. LLM-Enabled In-Context Learning for Data Collection Scheduling in UAV-Assisted Sensor Networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golam, M.; Alam, M.M.; Kim, D.S.; Lee, J.M. BLM-Chain: AI-Driven Blockchain for UAV Threat Resistance in IoBT. In Proceedings of the 2024 15th International Conference on Information and Communication Technology Convergence (ICTC), Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 16–18 October 2024; pp. 1609–1613. [Google Scholar]

- Piggott, B.; Patil, S.; Feng, G.; Odat, I.; Mukherjee, R.; Dharmalingam, B.; Liu, A. Net-GPT: A LLM-Empowered Man-in-the-Middle Chatbot for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. In Proceedings of the Eighth ACM/IEEE Symposium on Edge Computing, Wilmington, DE, USA, 6–9 December 2023; pp. 287–293. [Google Scholar]

- Sezgin, A. Scenario-Driven Evaluation of Autonomous Agents: Integrating Large Language Model for UAV Mission Reliability. Drones 2025, 9, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Wu, J.; Zhu, M.; Zhou, Y.; Xiao, F.; Zhang, Y. LLM-QL: A LLM-Enhanced Q-Learning Approach for Scheduling Multiple Parallel Drones. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2025, 37, 5393–5406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Amin, R.; Aldabbas, H.; Alouffi, B. Lightweight Challenge-Response Authentication in SDN-Based UAVs Using Elliptic Curve Cryptography. Electronics 2022, 11, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mughal, U.A.; Hassler, S.C.; Ismail, M. Machine Learning-Based Intrusion Detection for Swarm of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Conference on Communications and Network Security (CNS), Orlando, FL, USA, 2–5 October 2023; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, H.; Lu, Y.; Yang, T.; Liu, Z.; Chen, J. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles anomaly detection model based on sensor information fusion and hybrid multimodal neural network. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 132, 107961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masadeh, A.; Alhafnawi, M.; Salameh, H.A.B.; Musa, A.; Jararweh, Y. Reinforcement Learning-Based Security/Safety UAV System for Intrusion Detection Under Dynamic and Uncertain Target Movement. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 12498–12508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sun, G.; Duan, L.; Wu, Q. Multi-Objective Optimization for UAV Swarm-Assisted IoT With Virtual Antenna Arrays. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2024, 23, 4890–4907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, W.; Liu, L.; Ding, Y.; Sun, S.; Gu, Y. ETD: An Efficient Time Delay Attack Detection Framework for UAV Networks. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2023, 18, 2913–2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tlili, F.; Ayed, S.; Fourati, L.C. A New Hybrid Adaptive Deep Learning-Based Framework for UAVs Faults and Attacks Detection. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2023, 16, 4128–4139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Lu, W.; Zhao, N.; Nallanathan, A.; Wang, X.; Yang, X. Collaborative Communication and Computation for Secure UAV-Enabled MEC Against Active Aerial Eavesdropping. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2024, 23, 15915–15929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.X.; Chen, L.; Meng, L. Advancing Large Language Models with Enhanced Retrieval-Augmented Generation: Evidence from Biological UAV Swarm Control. Drones 2025, 9, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Alami, H.; Rawat, D.B. Lightweight Language Models in Autonomous Systems: In-Context Learning with Bidirectional Alignment for Fault Detection. In Proceedings of the ICC 2025—IEEE International Conference on Communications, Montreal, QC, Canada, 8–14 June 2025; pp. 4395–4400. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, W.; Sun, H.; Zhang, X.; Liang, X.; Zhu, S.; Jiang, Z. Boosting resilience design of cargo UAVs: A fault diagnosis method utilizing MRKG and LLM-FCT reasoning. J. Eng. Des. 2025, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasser, M.; Shalash, O.; Ismail, O. Optimized Decentralized Swarm Communication Algorithms for Efficient Task Allocation and Power Consumption in Swarm Robotics. Robotics 2024, 13, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).