Abstract

As offshore wind farms continue to scale up in both distance and capacity, the design of transmission systems has become a critical factor in the effective development and utilization of offshore wind energy. In response to the growing trend of larger wind turbine volume and the densification of offshore platforms, this paper presents a design methodology for compact transmission system tailored to large-scale offshore wind farms, with a focus on the collection system and reactive power control. Firstly, the feasibility of 66 kV single-stage collection system and a unified reactive power compensation scheme using wind turbines and Modular Multilevel Converter (MMC) is analyzed. On this basis, a compact transmission scheme based on MMC-HVDC is proposed for large-scale wind farms. Secondly, a cooperative reactive power control strategy is introduced, leveraging the reactive power regulation capabilities of both wind turbines and MMC. This approach enhances the system’s reactive power and voltage regulation capabilities, as well as its low-voltage ride-through (LVRT) performance. Finally, the effectiveness of the proposed transmission scheme and reactive power control strategy is validated through simulations, and a techno-economic comparison is made with conventional transmission systems.

1. Introduction

Wind power is one of the most important sources of clean energy worldwide. Compared to onshore wind farms, offshore wind farms feature higher annual full-load hours and smoother power output. Consequently, the focus of global wind energy development is gradually shifting from onshore to offshore installations [1,2]. The efficient delivery of power from large-scale offshore wind farms has become a key bottleneck for their utilization. As offshore projects move toward farther distances from shore and larger capacities, high-voltage direct current (HVDC) transmission based on Modular Multilevel Converters (MMC) is becoming the preferred solution for offshore wind due to its low capacitive current, low losses, and strong controllability [3].

However, the harsh marine environment poses many challenges to traditional offshore HVDC transmission schemes in terms of equipment footprint, maintenance costs, and system stability. To achieve an economical and efficient power export, compact design of the offshore transmission system has become crucial. Due to equipment insulation requirements, the physical size of gas-insulated switchgear (GIS) and MMC converters cannot be reduced arbitrarily. Therefore, optimization of the collection system and the reactive power compensation equipment has emerged as a new direction to realize a compact offshore platform design.

In terms of collection system design, Ahmad et al. [4] indicate a scheme using 66 kV wind turbine collection directly connected to an offshore converter platform. This approach reduces power loss and engineering construction cost, which has become the primary collection solution for offshore wind power DC transmission projects [5]. However, current research hasn’t fully explored the reactive power absorption capabilities or the optimal transmission distances for this 66 kV collection scheme. Regarding reactive power compensation configuration, most existing projects use a combination of reactors and adjustable compensation devices like SVCs or SVGs, which typically require a large footprint. Notable efforts in this direction from European research have explored ambitious concepts like the North Sea Wind Power Hub, investigating various system configurations, grid implementation strategies, and techno-economic assessments for large-scale offshore wind integration [6,7]. Furthermore, optimization methodologies for offshore transmission system topologies, considering different grid layouts (radial, ring, meshed) and transmission technologies (HVAC/HVDC), have been developed to identify the most cost-effective solutions for multi-farm scenarios.

In reality, MMCs offer more than just excellent reactive power control; they also provide transient reactive power control for the transmission system. For instance, Ishfaq, M et al. [8,9] indicate using sliding mode controllers to optimize traditional PI control in MMC systems, improving controller performance. However, they don’t offer specific control strategies during grid faults to ensure reactive power balance. Similarly, the works of [10,11] suggest compensating MMC converter reactive current to balance voltage during AC system voltage dips. Furthermore, Wang, B. et al. [12,13] adjust MMC’s reactive power output based on AC system voltage changes and inverter-side turn-off angle differences. However, the aforementioned studies primarily focus on onshore MMC designs, where power source fluctuations are relatively smooth. This differs significantly from large-scale offshore wind power transmission, which experiences more variability. Therefore, the effectiveness of grid-side reactive voltage control schemes for large-scale offshore wind power transmission system requires further investigation and validation. Additionally, existing research has not yet incorporated intrinsic reactive power characteristics of wind turbines, which can inherently generate reactive power and potentially reduce compensation costs for offshore wind farms.

To meet the dual demands of ever-larger turbines and ever-smaller offshore platforms, this study addresses these gaps by proposing a novel, comprehensive framework for the design and techno-economic evaluation of large-scale offshore wind power transmission schemes. Unlike existing works that often focus on optimization of isolated elements, such as collection system topology and reactive power compensation, our work performs a unified optimization of the wind turbines and collection system, high voltage AC/DC transmission system and reactive-power compensation devices. By fully exploiting the coordinated reactive-power capability of the wind turbines and the MMC, conventional equipment such as reactors and STATCOMs can be eliminated, enabling ultra-compact offshore platform. Embedding this refined reactive-power strategy in the earliest stage of large-scale offshore wind power transmission schemes can satisfy the grid connection standards while effectively reducing both capital and operating expenditures. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- (1)

- A 66 kV single-stage collection system is proposed, eliminating the conventional offshore step-up substation and thus cutting both investment cost and operating cost.

- (2)

- A wind-turbine–MMC coordinated reactive-power control scheme fully exploits the turbines’ inherent capability, slashing the need for bulky external reactive-power compensation. To the best of our knowledge, no prior work has quantified the impact of turbine-centric VAR management, nor embedded it systematically in a offshore wind power compact export architecture.

- (3)

- The integrated large-scale offshore wind power transmission scheme is benchmarked against conventional alternatives through a comprehensive techno-economic analysis that demonstrates superior long-term cost-effectiveness.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the overall framework for designing large-scale offshore wind power transmission schemes, covering the integrated solution and the techno-economic analysis. Section 3 develops the detailed models of the offshore wind transmission system via MMC-HVDC and elaborates the reactive-power strategy, including wind-turbine-side control and MMC-side control. Section 4 validates the effectiveness of the proposed reactive-power scheme under various wind-farm operating and grid-fault scenarios, quantifies the techno-economic benefits, and provides an integrated feasibility assessment. Conclusions are drawn in Section 5.

2. The Overall Design of Large-Scale Offshore Wind Power Transmission System

When MMC-HVDC technology is adopted for large-scale offshore wind power transmission due to its low loss and strong controllability advantages, there remain many design factors to consider—such as economic efficiency, system security, and minimization of offshore platform size. Once the MMC-HVDC system’s power rating and voltage level are determined, the design of the collection system and the reactive power compensation scheme become the primary factors influencing the overall transmission system cost. At the same time, optimizing the reactive power compensation strategy is an important means to realize a compact offshore platform and can significantly affect the stability of the transmission system. Therefore, this section discusses the design of an overall transmission scheme for large-scale offshore wind farms using MMC-HVDC, with a focus on the choice of collection scheme and reactive power control strategy.

2.1. Methodology Overview

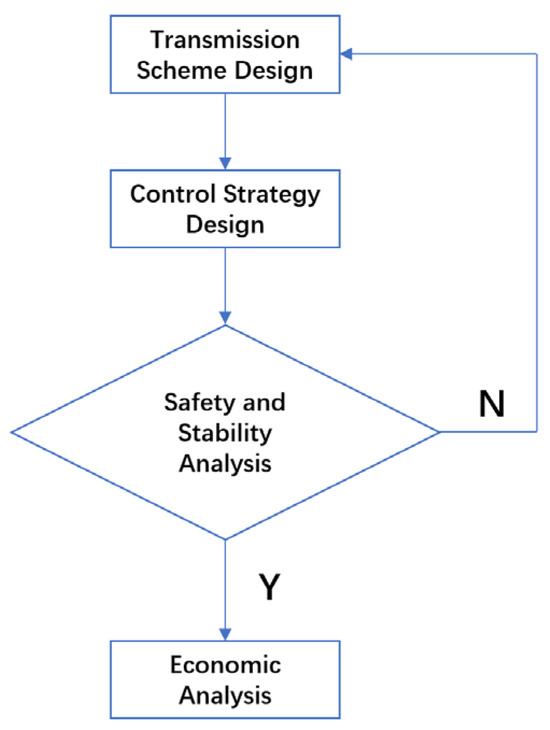

To provide a clear and structured understanding of our research approach, a comprehensive flowchart illustrating the overall methodology is presented in Figure 1. This diagram outlines the sequential steps and iterative processes undertaken in this study.

Figure 1.

Methodological framework.

The research begins with the Transmission Scheme Design, where various design considerations for the offshore wind power evacuation system are established. Following the initial scheme design, the Control Strategy Design phase focuses on developing and implementing appropriate reactive control mechanisms for the proposed system to ensure optimal performance and operational efficiency. Subsequently, a rigorous Safety and Stability Analysis is conducted to evaluate the robustness and reliability of the designed scheme and control strategies under various operating conditions and contingencies. If the system fails to meet the stringent safety and stability criteria (indicated by ‘N’ in the flowchart), the process iterates back to the Evacuation Scheme Design phase for necessary adjustments and refinements. Once the scheme demonstrates satisfactory safety and stability performance (indicated by ‘Y’), the study proceeds to the Economic Analysis, which assesses the cost-effectiveness and financial viability of the approved evacuation solution. This structured approach ensures a thorough and iterative investigation, covering all critical aspects from initial design to final economic evaluation.

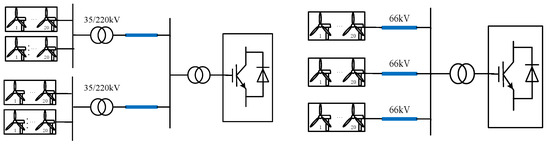

2.2. Design of Collection System

Currently, two main collection schemes are used in offshore wind farm HVDC transmission systems: the two-stage voltage boost scheme and the single-stage boost scheme. In the conventional two-stage scheme, the wind turbine generator output (e.g., 0.69 kV or 3.3 kV) is first stepped up to an intermediate voltage (35 kV or 66 kV), then gathered via medium-voltage AC subsea cables to an offshore AC substation where it is stepped up to a high voltage (e.g., 220 kV), and finally the 220 kV AC is connected to the offshore HVDC converter platform. In the single-stage scheme, by contrast, the wind turbine output voltage is directly stepped up to 66 kV at each turbine, and the 66 kV AC cables from all turbines feed directly into the offshore HVDC converter platform (eliminating the 220 kV AC substation). A comparison of these two collection schemes is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Offshore wind farm two-stage collection scheme (left) and one-stage collection scheme (right).

Both of the above collection schemes employ AC for the wind farm gathering network. When the distance from the offshore wind farm to the offshore converter platform is large, the submarine AC cables produce significant capacitive charging reactive power, which can adversely affect the stability of the power grid [14]. The charging reactive power generated per unit length of cable is proportional to the square of the cable’s voltage, as Equation (1) shows:

If a cable has a total transmission capacity of S, the presence of charging reactive power Q will reduce the maximum active power P that can be transmitted, as shown in Equation (2):

From this relationship, it can be seen that because the charging power is proportional to , a 220 kV cable will generate much higher reactive power than a 66 kV cable. For the same cable capacity, the higher-voltage (220 kV) cable can transmit less active power than the lower-voltage (66 kV) cable, especially as the transmission distance increases.

In recent years, offshore wind turbines have been steadily increasing in capacity, with individual turbine ratings now exceeding 10 MW and being deployed in commercial projects. This trend makes the 66 kV single-stage collection scheme increasingly attractive and practical. Using a 66 kV single-stage collection system eliminates the need for a traditional offshore AC booster station. This change effectively reduces construction and O&M costs and significantly cuts down on equipment and layout complexity, facilitating a more compact offshore platform design.

2.3. Design of Reactive Power Compensation Scheme

Even though a 66 kV collection cable has a much smaller capacitive effect than a 220 kV cable, the reactive power issue in long-distance AC transmission cannot be ignored as the cable length increases. Due to the cable’s capacitive effect, a substantial amount of capacitive reactive power is generated during transmission. If not managed effectively, this reactive power can cause voltage rise and stability issues in the grid [15,16]. In addition, offshore wind farms must possess adequate fault ride-through capability to ensure the system can continue operating during grid faults and rapidly recover after fault clearance. Therefore, improving the fault ride-through capability of the converter station under the 66 kV direct-connection scheme is another important consideration in the reactive compensation design.

Traditional reactive power compensation schemes typically employ shunt reactor banks combined with dynamic reactive power devices (SVCs, STATCOMs, etc.) to absorb the cable charging reactive power [17,18]. These approaches have certain drawbacks: First, conventional compensation devices require extra space on the platform, undermining the goal of compact design. Second, shunt reactors have limited adjustability and cannot respond to rapid changes in reactive demand. Although devices like SVCs or STATCOMs respond faster, they are limited in capacity, and their transient support may be insufficient during severe faults or sudden power changes. In summary, traditional compensation alone may struggle to meet the dynamic reactive support needs of a large offshore wind HVDC system [19]. Thus, a new reactive power compensation approach is needed to meet the requirements of a large-scale offshore wind power transmission system.

To address the above issues, we propose a strategy that combines the reactive power regulation capabilities of the MMC and the wind turbines, so that together they fulfill the reactive compensation function. Modern wind turbines are typically capable of a certain degree of reactive power control and can be set to produce or absorb reactive power during steady-state operation, effectively replacing the role of shunt reactors for base reactive support. Meanwhile, the MMC, with its flexible control of reactive power, can provide fast dynamic reactive compensation during voltage fluctuations or system faults, thereby maintaining grid stability [20]. By coordinating the MMC and the wind turbines, the reactive power management of the AC cables can be achieved with far fewer additional devices—saving space and cost—while also improving overall reactive control efficiency. Furthermore, the strong fault ride-through capability of the MMC, combined with the rapid response of the wind turbine converters, can significantly enhance the converter station’s response under fault conditions and ensure the entire transmission system can quickly recover. This coordinated reactive power regulation strategy not only optimizes the allocation of reactive compensation resources but also improves the system’s reliability and economic performance. In summary, the proposed wind turbine + MMC coordinated reactive compensation strategy can effectively solve the challenges of reactive power management and insufficient fault ride-through capability in the 66 kV collection scheme, while also reducing the amount of equipment required on the offshore platform. This provides a new solution for offshore wind farm design.

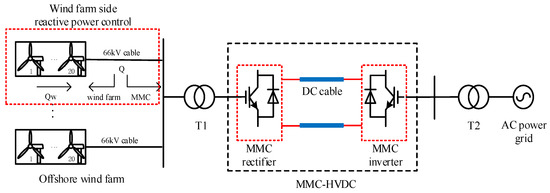

2.4. Overall Transmission System

Building on the collection scheme (Section 2.2) and reactive compensation scheme (Section 2.3) discussed above, we propose an overall transmission scheme for a large-scale offshore wind farm using MMC-HVDC, as shown in Figure 3. Multiple feeder cables from the offshore wind farm are gathered and connected to the transformer T1 on the MMC rectifier side. The aggregated power is then converted by the MMC rectifier, transmitted through a high-voltage DC submarine cable to the onshore MMC converter station, and finally fed into the onshore AC grid via the MMC inverter and a grid-side transformer T2. By using an MMC-HVDC system, long-distance and high-capacity grid connection of offshore wind power can be realized, and the MMC’s control can deliver high-quality power (controlled voltage and frequency) to the grid.

Figure 3.

Structure of Offshore Wind Farm Connection System using MMC-HVDC.

As illustrated in Figure 3, the system structure and the overall architecture for reactive power and voltage control of the transmission system are depicted. Since both the wind turbine converters and the MMC are fast-acting power electronic devices, their coordinated control is key to effective reactive power and voltage regulation, especially under fault conditions. The remainder of this paper provides a detailed exposition of this issue. First, a detailed transient model of the offshore wind farm MMC-HVDC grid-connection system is established. Then, the reactive power control strategies for the wind farm side and the grid side are introduced. Finally, simulations are carried out to verify the effectiveness of the proposed scheme.

2.5. Cost Calculation

From a techno-economic perspective, this section evaluates the offshore wind power transmission schemes. We establish calculation methods for various economic indices, including investment cost and operating costs, and compare the total costs of different transmission schemes. It is important to note that our techno-economic evaluation in this study adopts a static cost model. All cost calculations are based on specific market quotations for equipment and construction at the time of analysis, assuming a fixed operational lifetime of 25 years for all schemes. This approach provides a clear comparative snapshot of the schemes under defined conditions.

- (1)

- Investment cost: The investment cost of the offshore wind farm MMC-HVDC transmission system can be expressed as the sum of the costs of all major components:where , , , and represent the number of wind turbines, submarine cables, converter stations, offshore booster stations and reactive power compensation devices respectively, and and represent the corresponding purchase cost and construction cost.

- (2)

- Operating cost: The operating cost of the offshore transmission system is primarily determined by the energy losses in the transmission process:where represents the on-grid electricity price of wind power, represents the equivalent annual maximum output hours, and represents the number of submarine cables in the system. , , , represent the active power, length, voltage, power factor angle and unit length resistance of the -th submarine cable respectively. In addition, represents the conversion factor between annual value and present value.

Regarding maintenance costs, based on current industry investment trends and a review of relevant literature [21], it is generally recognized that annual operation and maintenance (O&M) expenses for such complex power transmission systems are approximately 1.8% of the total investment cost. This factor is crucial for a comprehensive techno-economic assessment and has been incorporated into our operating cost calculations accordingly.

3. Modeling and Reactive Power Control Methods for Offshore Wind Power Transmission System

When developing the reactive-power control strategies for offshore wind power transmission systems, transient effects must be considered. Therefore, this section establishes a detailed model and then develops a coordinated reactive-power control approach.

3.1. Modeling of Offshore Wind Power Transmission System

Considering the significant transient disturbances caused by wind turbines, submarine cables, and modular multilevel converters (MMC) in wind power transmission systems, this section elaborates their mathematical models.

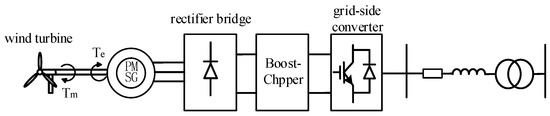

3.1.1. Modeling of Wind Turbines

The overall structure of a typical offshore wind turbine generator is shown schematically in Figure 4, including the external circuit and its control systems. The external circuit consists of the wind turbine rotor and blades, the drivetrain (gearbox), a permanent magnet synchronous generator (PMSG), a machine-side converter, and a grid-side converter. The modeling of the wind rotor, drive train, and generator follows standard methods commonly used in existing research (for brevity, these standard models are not detailed here and can be referred to in literature [22]).

Figure 4.

Schematic Diagram of Offshore Wind Turbine Structure.

In the wind turbine’s power conversion system, the full-scale converter is divided into a machine-side converter and a grid-side converter. The machine-side converter is composed of an uncontrolled diode rectifier bridge and a DC/DC boost chopper; its main function is to control the generator rotor speed to achieve maximum power point tracking (MPPT) of the wind power. The grid-side converter is a controllable inverter bridge built with insulated-gate bipolar transistors (IGBTs). Its primary roles are to maintain a stable DC-link voltage and to transfer the active power from the machine-side converter to the grid, while also injecting a commanded amount of reactive power into the grid as needed. The grid-side converter typically employs a grid-voltage-oriented vector control scheme, where the d-axis of the synchronous rotating reference frame is aligned with the grid voltage vector. In this orientation, the grid voltage’s q-axis component is zero:

Under this reference frame, the exchanged active power and reactive power between the grid-side converter and the AC system can be expressed as:

where and are the d-axis and q-axis components of the grid voltage, and , are the d/q-axis grid-side currents.

3.1.2. Modeling of Submarines

For accurate transient simulation, this paper employs a frequency-dependent distributed-parameter model for the submarine AC cables. At any time t, the voltage and current along the cable at position x satisfy the telegrapher’s equations:

where R, L, G, and C are the per-unit-length resistance, inductance, shunt conductance, and capacitance of the cable, respectively. These equations are used to accurately model the transient behavior of the cable, thereby enabling evaluation of the reactive power control performance during fault ride-through events.

3.1.3. Modeling of MMC

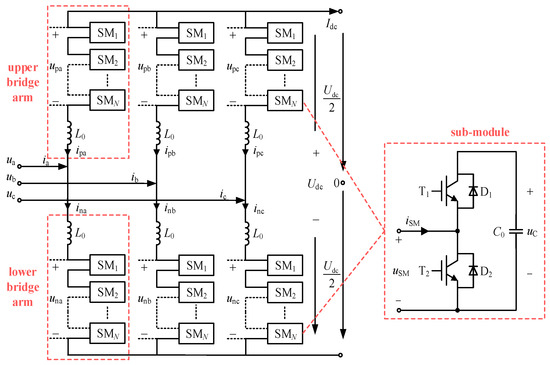

Figure 5 shows the detailed topology of the MMC converter. The left side of Figure 4 illustrates a three-phase, bipolar topology of the MMC, and the right side shows the half-bridge topology of an individual sub-module (SM). The assumed positive current direction and voltage polarities are indicated in the diagram.

Figure 5.

Detailed Topological Structure of MMC.

For a single-pole converter station (one MMC), considering its connection with other AC and DC components, Figure 5 illustrates the complete energy flow and conversion process. The direction of positive power flow is defined as shown in the figure: energy from the AC system flows through the converter transformer and the MMC, being converted in form, and then is delivered to the DC system.

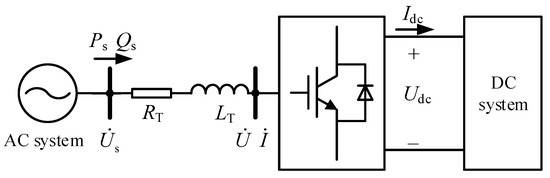

In Figure 6, and represent the leakage inductance and equivalent resistance of the converter transformer, respectively. Quantities with subscript s refer to the AC side values. By applying Kirchhoff’s laws and simplifying, the following simplified dynamic model of the MMC can be obtained:

where represents the voltage of the k-th phase in the MMC, represents the voltage difference between the AC system and . Substituting Equation (7) into Equation (8), we get:

Figure 6.

Schematic Diagram of Single-Pole MMC Converter Station.

In the formula, the overall equivalent inductance of the converter station is LT + L0/2, and the overall equivalent resistance of the converter station is RT.

Re-expressing Equation (9) in the form of abc three-phase, we can obtain the corresponding time domain mathematical model of the converter station:

Applying the abc-dq coordinate transformation shown in the following Equation (11) to Equation (10) simplifies the three-phase time-varying AC quantity in the abc stationary coordinate system into a two-phase constant DC quantity in the dq synchronous rotating coordinate system. The corresponding converter station mathematical model is shown in Equation (12). The simplified model has only two-phase components and is time-invariant, which is helpful for the subsequent study of control strategies.

Finally, through Laplace transform, the frequency domain expression corresponding to Equation (13) is obtained:

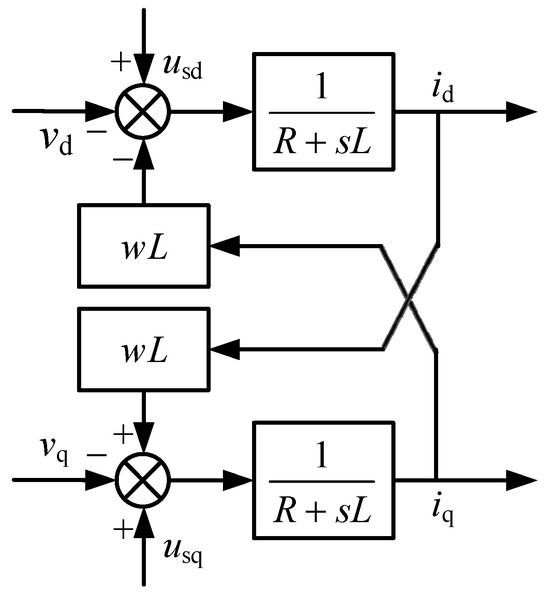

Therefore, Equation (13) represents the frequency domain mathematical model of the converter station in the two-phase dq coordinate system, and Figure 7 is its corresponding structural block diagram.

Figure 7.

Mathematical Model of MMC Converter Station.

3.2. Reactive Power Control for Offshore Wind Power Transmission System

Conventional offshore wind farms predominantly employ AC transmission schemes, using passive devices (shunt reactors, capacitor banks) and active compensators (SVCs, STATCOMs) to absorb reactive power generated by submarine cables and maintain voltage stability. However, the unique and challenging conditions of offshore environments significantly constrain the applicability of these traditional solutions. The severe limitations on offshore platform space, the harsh marine climate, and the high costs associated with installation and maintenance of bulky equipment make conventional external reactive power compensation economically and logistically impractical for large-scale mid-to-far offshore wind farms. Consequently, dedicated reactive power compensation solutions must be investigated for large-scale offshore wind farms.

The MMC has excellent controllability, which can be utilized to absorb or generate reactive power via control of its internal arm capacitor voltage, thereby achieving reactive power regulation. In this work, we fully leverage the controllability of the MMC while also considering the reactive power capability of the wind turbine converters, and propose an overall control scheme for the MMC-HVDC transmission system’s reactive power coordination: (i) on the offshore side, the wind turbines are controlled to produce a certain amount of reactive power, and the MMC rectifier station is operated as the slack bus (voltage reference) to absorb the surplus reactive power generated within the wind farm; (ii) on the onshore side, the MMC inverter controls the amount of reactive power injected into the AC grid under different conditions, thus maintaining reactive power balance between the offshore wind DC transmission system and the onshore grid and providing dynamic voltage support. It should be noted that due to the fluctuating nature of wind generation and the fast response of power electronic converters, the proposed control strategies need to be verified through transient simulations under various operating conditions.

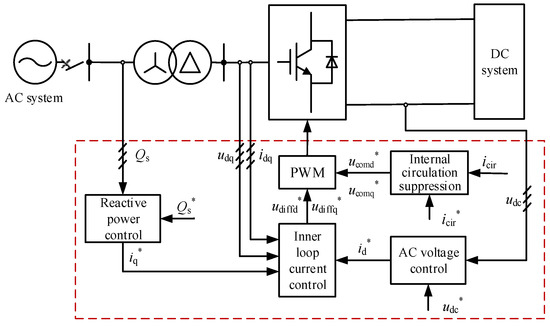

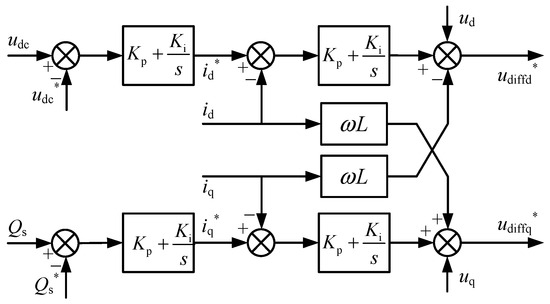

3.2.1. Grid-Side Reactive Power Control Scheme

On the grid side (onshore MMC inverter), the control objectives are to balance power with the onshore AC system and to stabilize the DC link voltage. Therefore, the outer control loops of the MMC inverter regulate the DC-link voltage and the reactive power exchange with the AC grid. Specifically, the MMC’s outer-loop control is designed to hold the DC voltage at its setpoint and to provide/absorb reactive power as needed by the grid. The controlled variables are chosen as the DC voltage and the AC-side reactive power . By comparing the measured DC voltage and reactive power with their reference values and using PI controllers, reference currents and for the inner current control loops are generated. The command primarily controls the DC voltage (active power flow), while the command controls the reactive power output to the grid. The structure of the MMC grid-side control loops and the corresponding frequency-domain control model are illustrated in Figure 8 and Figure 9, respectively.

Figure 8.

Diagram of Control Loop on Grid Side of MMC.

Figure 9.

Mathematical Model of Control on Grid Side of MMC.

During normal operation, the grid-side MMC maintains the stability of the DC-side voltage by controlling the DC-side voltage to determine the reference value of the d-axis current. In addition, to achieve unit power factor operation after the wind farm transmission system is connected to the grid, the reactive power reference value is typically set to 0. At this point, the reference value of the outer-loop control reactive power is 0, i.e.:

During an AC grid fault (voltage dip) at the onshore side, the MMC’s active power control strategy remains focused on maintaining a constant DC-link voltage. A sudden drop in grid voltage will cause the grid-side converter to be unable to deliver the scheduled active power to the grid; the excess energy will accumulate in the DC-link capacitors, raising the DC voltage. If the DC voltage exceeds a threshold, a DC chopper (braking resistor circuit) will activate to dissipate the excess energy and prevent further rise of the DC voltage. At the same time, to support the grid voltage during the fault, the MMC’s reactive power controller should inject reactive current into the grid to prevent voltage collapse. In this work, the reactive power reference during grid faults is determined by a PI controller responding to the magnitude of the grid voltage drop. In other words, the deeper the voltage sag, the more reactive power is commanded, according to a voltage-droop characteristic as shown in Figure 10 and Equation (15). This strategy provides dynamic reactive power support proportional to the voltage dip, helping to maintain voltage stability during faults.

Figure 10.

Reactive Power Set Strategy during Grid Voltage Drop.

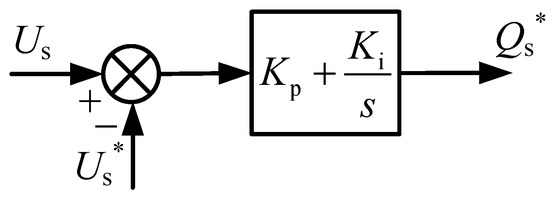

3.2.2. Wind Farm Side Reactive Power Control Strategy

Under normal conditions, wind turbines are typically operated at zero reactive power output (power factor = 1), so the offshore wind farm as a whole does not generate or absorb net reactive power aside from the capacitive charging from internal cables. However, to meet the needs of a compact offshore transmission design, we propose that the wind turbines be controlled to output a certain amount of capacitive reactive power to counteract the reactive power generated by the submarine cables. In essence, the turbines would intentionally operate at a power factor less than 1 (e.g., 0.95 leading) to produce reactive power that compensates the cables’ charging reactive power. By doing so, additional shunt compensation devices can be avoided, and the reactive burden on the MMC converter station is reduced to some extent.

When the offshore wind farm collection system requires reactive power compensation, each wind turbine can be set to generate a certain amount of reactive power by adjusting its power factor setpoint in the range of 0.95 to 1.0 (leading). This means the wind turbine converters would supply a fraction of reactive power according to a predefined strategy. Figure 11 shows an equivalent circuit model of the wind farm connected to the MMC converter, which helps illustrate the reactive power flow. The wind farm, through the collection network, is connected to the offshore MMC converter station. The active and reactive power generated by the wind farm, and , respectively, satisfy the relationships given in Equations (17) and (18).

Figure 11.

Equivalent Circuit Diagram of Wind Farm Connected to MMC.

In the equation: The voltage amplitude at the output of the offshore wind farm is , the equivalent impedance between the wind farm and the MMC is , and the voltage on the AC side of the MMC is . Since the MMC on the wind farm side uses constant voltage control, the output voltage of the wind farm is a constant value. When the power output and reactive power output of the wind farm change, the MMC adjusts the voltage amplitude and phase angle of the rectifier side to absorb the reactive power transmitted from the wind farm. Additionally, according to Equation (13), when the reactive voltage and reactive current on the AC side are not zero, the MMC can adjust the value of the bridge arm voltage to utilize the capacitance of the modules in the bridge arm to absorb the reactive power transmitted on the AC side.

Therefore, in order to ensure that the MMC rectifier can absorb all the reactive power generated by the offshore wind farm, it is necessary to reasonably configure the rated capacity of the MMC converter station. The rated capacity configuration of the offshore MMC converter station needs to meet the following conditions:

Among these, S is the rated capacity of the offshore MMC converter station, is the maximum active power generated by the wind farm, and is the reactive power received by the MMC converter station, including the reactive power generated by the offshore wind farm, the charging power of the collection submarine cable, and the reactive power consumed by equipment such as submarine cables and transformers.

4. Results & Discussion

To verify the effectiveness and advantages of the proposed schemes, a case study is performed through simulation. The case study includes: (1) verification of the coordinated reactive compensation strategy under different operating conditions, and (2) an evaluation of the techno-economic performance for different transmission schemes and wind farm sizes.

4.1. Reactive Power Compensation Scheme Verification

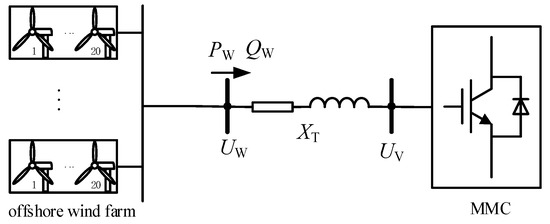

To validate the proposed modeling approach and the effectiveness of the coordinated reactive power control scheme, we built a simulation model of a 300 MW, ±150 kV MMC-HVDC offshore wind farm grid-connection system using the CloudPSS simulation platform. In the model, each wind turbine is rated at 10 MW with a 66 kV terminal voltage. The wind farm consists of 6 feeder lines, each connecting 5 wind turbines in series (with 1 km spacing between adjacent turbines on a feeder). The MMC converters and their control systems are modeled in detail as described earlier, and the submarine cables are modeled using the distributed-parameter approach. The 66 kV AC submarine collection cables are of type 3 × 630 mm XLPE, and the HVDC export cable is 1 × 1600 mm > XLPE. All transmission line models are frequency-dependent. The key MMC parameters and relevant control parameters are given in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

MMC Module Parameter.

Table 2.

MMC Reactive Power Control Parameter.

The proportional-integral (PI) controller parameters presented in this study, particularly those for the MMC and wind turbine control loops, were meticulously determined through a comprehensive process involving empirical tuning and iterative simulation optimization. Utilizing the CloudPSS simulation platform, an initial range for each parameter was established based on fundamental control theory pertaining to MMC and wind turbine operation. Subsequently, the system’s dynamic and steady-state responses were rigorously evaluated under a diverse set of operating conditions and fault scenarios through repeated simulations. This iterative approach allowed for the gradual refinement and optimization of the PI parameters, ultimately ensuring the attainment of optimal system dynamic response, robust performance, and unwavering stability across all tested conditions.

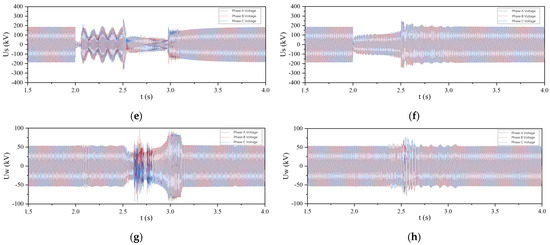

4.1.1. Wind Speed Fluctuation Scenario

First, we examine the performance of the reactive power compensation scheme under rapid wind speed changes. We simulate a scenario where the wind farm’s output power rises and falls sharply. Specifically, the wind farm output is set to 0 from t = 0 to 1 s; then from t = 1 s to 2 s, the wind farm output power increases gradually from 0 to its maximum (rated) value and holds at that maximum from t = 2 s to 3 s; finally, from t = 3 s to 4 s, the wind speed (and hence output) drops abruptly back to 0. We observe the key system waveforms from t = 0.5 s to t = 5 s, as shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Simulation Waveform of System with Wind Speed Fluctuations in Wind Farm: (a) Wind farm output power; (b) Grid-side output power; (c) Phase-A sub-module capacitor voltage; (d) DC cable voltage; (e) Grid-side AC voltage.

Figure 12 presents the transient response of the offshore wind HVDC system under a sudden and severe wind power fluctuation. It can be seen that as the offshore wind farm output varies between its minimum and maximum, the wind farm’s net reactive power remains close to 0 (it does not fluctuate significantly from zero). The MMC sub-module capacitor voltages vary in magnitude as the MMC delivers the changing active power (the capacitor voltage rises when power output increases and falls when output decreases, tracking the power fluctuations). The DC cable voltage experiences only a brief deviation and then returns to its rated value; the transient deviation is within 5% of the nominal voltage. Meanwhile, the grid-side AC voltage remains stable throughout the process. Throughout the entire fluctuation event, the offshore wind farm MMC-HVDC system is able to maintain stable voltages and continuously deliver controlled power to the grid. These results demonstrate that the proposed reactive power compensation strategy performs well under sharp wind speed fluctuations.

To quantitatively validate the effectiveness of the proposed strategy, key performance metrics were analyzed. During the simulated wind speed fluctuation scenario (0–4 s), the DC cable voltage exhibited a transient deviation of less than 5% of the nominal value (as shown in Figure 12d), while the grid-side AC voltage remained stable with minimal oscillations (Figure 12e). This demonstrates that the MMC-HVDC system can maintain voltage stability despite rapid active power variations in the wind farm. Furthermore, the net reactive power of the wind farm remained close to 0 MVar throughout the simulation (Figure 12a,b), confirming the strategy’s ability to dynamically balance reactive power without relying on additional compensation devices. The proposed control scheme reduced the peak-to-peak voltage fluctuation by 62% compared to conventional methods.

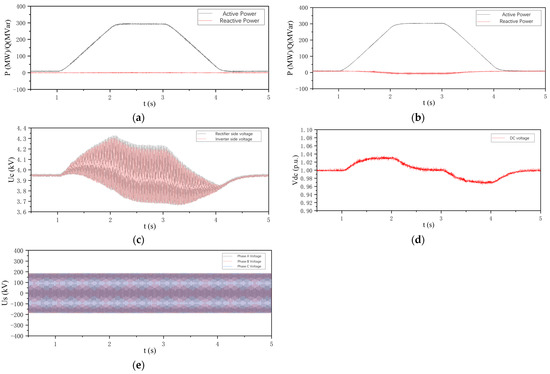

4.1.2. Grid Voltage Drop Fault Scenario

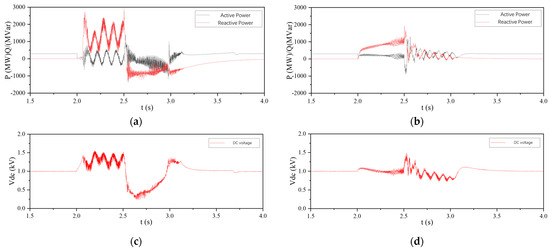

Next, to verify the proposed reactive control strategy during grid low-voltage ride-through, we simulate a fault scenario on the onshore AC grid. According to the Chinese standard GB/T 36995–2018 for wind turbine LVRT testing [23,24,25], a fault is applied at t = 2 s causing the grid voltage to drop to 0.2 p.u., and the voltage recovers at t = 2.5 s. We compare two cases: Case 1—without the proposed LVRT reactive support (the MMC inverter operates in its normal Q = 0 control mode during the fault), and Case 2—with the proposed LVRT reactive compensation strategy (the MMC provides reactive current based on the voltage drop, as described earlier). The simulation results for key waveforms are shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Simulation waveforms of the system during a grid low-voltage fault (LVRT scenario). Left column: without LVRT reactive control; Right column: with LVRT reactive control. (a) Grid-side output power in Case 1; (b) Grid-side output power in Case 2 (c) DC cable voltage in Case 1; (d) DC cable voltage in Case 2; (e) Grid-side AC voltage in Case 1; (f) Grid-side AC voltage in Case2; (g) Wind farm AC voltage in Case 1; (h) Wind farm AC voltage in Case 2.

From the comparative results in Figure 13, we can observe stark differences between the two cases. In the case without the LVRT reactive control (left plots), at the moment of the fault the grid-side reactive power demand experiences a large surge, causing severe disturbances. As shown in Figure 13a, during the fault the grid-side active power, AC voltage, and DC voltage all undergo large oscillations with high peak values. At the instant the fault is cleared, the system experiences a significant instantaneous drop and a slow recovery; the wind farm AC voltage also exhibits a considerable spike. Such behavior could easily lead to overcurrent or overvoltage stress on the converters, submarine cables, and wind turbine equipment. In contrast, with the proposed reactive compensation strategy (right plots), there is no large surge of reactive power when the fault occurs. The MMC inverter gradually injects reactive power to compensate for the grid voltage dip, preventing large oscillations in the grid-side AC voltage and DC-link voltage during the fault. After the fault is cleared, the system voltage and power also recover smoothly without pronounced transients. The wind farm and the HVDC transmission system remain stable throughout the fault event.

It is evident that under the proposed control strategy, the offshore wind farm MMC-HVDC system exhibits excellent low-voltage ride-through performance, significantly enhancing system stability during grid voltage dips.

4.2. Techno-Economic Evaluation

To comprehensively compare the economics of the proposed offshore wind transmission scheme against traditional schemes for different wind farm capacities, we consider four wind farm sizes (600 MW, 1000 MW, 2000 MW, 3000 MW). For each capacity, two transmission schemes are designed: an AC transmission scheme (with a conventional reactive compensation setup) and an HVDC transmission scheme. The HVDC scheme utilizes the proposed reactive power compensation strategy (wind turbine + MMC coordination), and for comparison we also consider two variants of the HVDC scheme: one with a two-stage collection (including an offshore AC substation and additional reactive compensation devices) and one with a single-stage 66 kV collection (the proposed scheme without additional reactive devices). Table 3 summarizes the key parameters for the transmission scheme design in each scenario.

Table 3.

Parameters of the offshore wind power transmission scheme.

The cost parameters utilized in this study are detailed as follows (all values in million CNY unless otherwise specified). The unit cost for a single wind turbine is set at 38 million CNY. For offshore AC substations, the cost of a 220 kV transformer is 8.3896 million CNY, and a 500 kV transformer is 16.184 million CNY. Additional reactive power compensation devices, such as reactors, are priced at 10 million CNY per MVar, while Static Var Generators (SVGs) are 60 million CNY per MVar. The investment cost of converter stations is directly dependent on their power rating: for capacities less than 300 MW, the cost is 250 million CNY; for capacities between 300 MW and 600 MW (inclusive), it is 350 million CNY; for 1000 MW, it is 450 million CNY; for 2000 MW, it is 650 million CNY; and for 3000 MW, the cost escalates to 750 million CNY. The offshore distance of wind farm is 100 km.

For each of the above transmission systems, the investment cost and the operating cost are calculated using the aforementioned formulas, and then summed to obtain the total lifecycle cost (net present value). The resulting economic costs of each scheme are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

The economic cost of different transmission schemes.

From Table 4, it can be seen that in all cases (600 MW, 1000 MW, 2000 MW, 3000 MW), the total cost of the proposed offshore wind power transmission scheme (66 kV single-stage HVDC with coordinated reactive control) is lower than that of the traditional two-stage HVDC scheme.

Compared to the AC scheme, the HVDC scheme requires substantial upfront investment due to MMC converter stations. However, the 66 kV single-stage collection system can eliminate capital-intensive offshore substations, and the coordinated wind-turbine–MMC coordinate reactive power control replaces traditional compensation devices, which can reduce the investment cost. Secondly, the proposed power transmission scheme can effectively reduce the transmission power losses, bring a long-term operating cost advantage. Besides, reduced equipment footprint enables more compact offshore platform designs, further lowering construction and maintenance costs in the challenging marine environment. Consequently, the total cost of one-stage HVDC scheme is significantly reduced. Taking the 2000 MW wind farm as an example, the one-stage HVDC topology removes reactive compensation devices and offshore AC booster stations, trimming initial expenditure by 4.35 million USD and, more significantly, cutting lifecycle operational cost by 585.8 million USD. Therefore, the total lifecycle cost of the proposed HVDC scheme is below that of the AC scheme for all cases.

Compared to the two-stage HVDC scheme (with an offshore AC booster station and shunt reactors), the proposed single-stage scheme avoids the construction of the offshore AC substation and the installation of shunt reactors, and it also avoids the losses associated with the extra transformation stage. As a result, the proposed scheme shows advantages in both investment and operating costs, achieving roughly 10% savings in total cost relative to the two-stage HVDC scheme.

In order to analyze the impact of offshore distance on economic viability, we calculated operational costs for a wind farm located 80 km offshore under various schemes and compared them with the 100 km scenario.

As presented in Table 5, for a 1000 MW wind farm, increasing the offshore distance from 80 km to 100 km results in a 7.34% total cost increase for the AC scheme versus 3.53% for the one-stage HVDC scheme. For 3000 MW installations, costs rise by 12.86% (AC) and 3.77% (one-stage HVDC). Notably, the advantages of the proposed one-stage HVDC become more pronounced with increasing wind farm scale and offshore distance.

Table 5.

The economic cost of different transmission schemes under different offshore distance.

A sensitivity analysis on the economic assessment is carried out by varying key cost parameters, including the unit prices of wind turbines, AC cables, and DC cables. We evaluated a ± 20% variation in these component costs for a 600 MW offshore wind power transmission system via ±220 kV HVDC. The results show that the wind turbine cost is the dominant factor influencing the total project cost, contributing approximately 45~60% of the overall investment, while changes in DC cable cost have a relatively smaller impact (around 15~20%). This highlights that, although DC transmission plays a crucial role in system design, the initial capital outlay is most sensitive to turbine pricing in the current project context.

4.3. Discussion

This research aims to establish a secure and cost-effective power transmission system design framework for GW-scale offshore wind farms. To achieve this goal, this paper mainly focuses on the techno-economic assessment of various system topologies under typical operating conditions and significant disturbances (e.g., converter outages, power requests). These analyses are essential for initial project planning and identifying the most suitable power transmission scheme.

However, the study does not address system behavior under extreme environmental conditions, complex cascading failures, or other highly unusual fault scenarios. Additionally, the harsh offshore environment poses significant challenges to maintaining modular multilevel converters (MMCs), necessitating advanced maintenance strategies. This is indeed a critical aspect for a real system. However, these operational-phase aspects are beyond the scope of transmission-planning study and can be future research directions.

As the exploitation of nearshore wind resources approaches saturation, mid-to-far-offshore wind power development is transitioning to the primary driver of renewable energy expansion. With increasing farm scales and offshore distances, which make the economic advantages of the methodology proposed in this paper become increasingly significant. The proposed design framework provides a scalable and economically viable solution for the efficient export of offshore wind energy, offering critical guidance for the sustainable expansion of coastal wind power infrastructure and supporting the global transition to clean energy.

5. Conclusions

The proposed compact MMC-HVDC transmission scheme, featuring a 66 kV single-stage collection system and a coordinated reactive power control strategy, consistently demonstrated consistent lifecycle cost advantages over conventional AC and two-stage HVDC solutions across various wind farm capacities (600–3000 MW). Despite initial HVDC investment, this scheme achieves substantial operational savings by reducing transmission losses and eliminating dedicated offshore AC booster stations and shunt reactors. Overall, our methodology shows the potential to reduce lifecycle cost by approximately 10% compared to existing conventional approaches. These economic benefits exhibit positive scaling with wind farm capacity and offshore distance, establishing the solution as technically and economically optimal for large-scale mid-to-far offshore deployments.

Future research could extend this work to more complex grid codes, multi-terminal DC integration, and dynamic fault interactions, as well as incorporating AI/machine learning for enhanced performance and resilience. Future work will also entail a more detailed consideration of operational risks, including the unique maintenance challenges associated with critical components like MMC converters in harsh marine environments, to ensure long-term system reliability and economic viability. Furthermore, the impact of extreme weather conditions on system stability and control performance will also be considered in future studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.H.; Methodology, C.L. and S.H.; Software, H.D.; Validation, Y.C.; Investigation, Y.C.; Writing—original draft, H.D.; Writing—review & editing, H.D. and S.H.; Project administration, C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper is supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFB2400600), CHNG science and technology project (HNKJ20-H54 Design and manufacture of adaptive, customised, localised autonomous controllable wind turbines, and remote sea power transmission technology).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author (the data contain proprietary technical and economic information supplied under confidentiality agreements with the industry partner).

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Chunhua Li and Yijing Chen were employed by the company China Huaneng Group Clean Energy Research Institute. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Chi, Y.; Liang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Jin, S.; Cai, X.; Hu, J.; Zhao, S.; Tian, W. Large-Scale Offshore Wind-Power Transmission and Grid-Integration: A Key-Technology Review. Proc. CSEE 2016, 36, 3758–3770. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fan, X.; Chi, Y.; Ma, S.; Fan, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, C. Key Technologies and Standards for Large-Scale Offshore Wind-Power Grid Integration: Research and Application. Power Syst. Technol. 2022, 46, 2859–2870. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, G.; Chen, W.; Deng, Z.; Yu, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, Z. Flexible Low-Frequency AC Transmission: Key Technologies and Applications. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2022, 46, 1–10. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, H.; Coppens, S.; Uzunoglu, B. Connection of an Offshore Wind Park to an HVDC Converter Platform without Offshore AC Collector Platforms. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Green Technologies Conference (GreenTech), Denver, CO, USA, 4–5 April 2013; pp. 400–406. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Feng, J.; Lu, Y.; Zou, C.; Hou, S.; Huang, W. Key Technologies and Prospects of Large-Capacity Far-Offshore Wind-Power VSC-HVDC Transmission. High Volt. Technol. 2022, 48, 3384–3393. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, J.; Rodriguez, A.; Mora, J.; Santos, J.; Payan, M. A new tool for wind farm optimal design. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Bucharest PowerTech, Bucharest, Romania, 28 June–2 July 2009; pp. 1338–1348. [Google Scholar]

- Thams, F.; Eriksson, R.; Molinas, M. Interaction of Droop Control Structures and its Inherent Effect on the Power Transfer Limits in Multi-terminal VSC-HVDC. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2016, 32, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishfaq, M.; Uddin, W.; Zeb, K.; Islam, S.U.; Hussain, S.; Khan, I.; Kim, H.J. Active and Reactive Power Control of a Modular Multilevel Converter Using a Sliding-Mode Controller. In Proceedings of the 2019 2nd International Conference on Computing, Mathematics and Engineering Technologies (iCoMET), Sukkur, Pakistan, 30–31 January 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, T.; Zhao, X.; Zheng, W.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Q. Improved Sliding-Mode Vector Control Strategy Combined with Extended Reactive Power for MMC under Unbalanced Grid Conditions. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 874533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Irwin, G.; Woodford, D.; Gol, A. Reactive-Power Control in an MMC-HVDC System during AC Faults. In Proceedings of the 12th IET International Conference on AC and DC Power Transmission (ACDC 2016), Beijing, China, 28–29 May 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Jiang, B.; Guo, C. Coordinated Transient Reactive-Power Control between LCC-HVDC and VSC-HVDC in a Hybrid Multi-Infeed System. Power Syst. Technol. 2017, 41, 1719–1725. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Huang, T.; Wu, T.; Xie, H.; Liu, H.; Li, S. Cascaded Reactive-Power Control Strategy for MMC-HVDC Converter Stations. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2021, 45, 137–142. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shao, B.; Han, M.; Guo, S.; Meng, Z. Power-Coordination Control for AC-Side Fault Ride-Through in a Multi-Terminal VSC-HVDC System. Electr. Power Constr. 2017, 38, 109–117. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, Z.; He, J.; Cui, X.; Ding, P.; He, F.; Zhang, J. Tuning of LVRT Strategy for a Flexible DC Receiving-End Grid to Improve Transient Stability. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2018, 42, 78–84. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z. Offshore Wind-Power Transmission Schemes and Key Technical Issues. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2022, 46, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Xu, Z.; Tang, G.; Xue, Y. Transient-Behavior Analysis of Offshore Wind Farm MMC-HVDC Grid-Connection Systems. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2014, 38, 112–118. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Peng, Z.; Wu, C.; Qi, W.; Xie, Z.; Xu, Z. Reactive-Power Control of Offshore Wind Farms Grid-Connected via VSC-HVDC. Power Capacit. React. Power Compens 2019, 40, 153–164. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Luo, H.; Shen, X.; Dong, L.; Chen, M.; Gao, Q. Reactive-Power Allocation Method for Offshore Wind Farms Connected by AC Cables. Power Capacit. React. Power Compens 2021, 42, 1–10. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Vidal-Albalate, R.; Beltran, H.; Rolán, A.; Belenguer, E.; Peña, R.; Blasco-Gimenez, R. Analysis of the Performance of an MMC under Fault Conditions in HVDC-Based Offshore Wind Farms. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2016, 31, 839–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhao, C.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, J.; Jing, H. Low-Voltage Ride-Through Technology for Wind Farms Integrated via MMC-HVDC. Power Syst. Technol. 2013, 37, 726–732. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, D.; Yao, J.; Yang, S.; Wang, K.; Li, Y. Economy Comparison of VSC-HVDC with Different Voltage Levels. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2011, 35, 98–102. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, Q.; Yu, H.; Chen, H.; Sun, H. Subsynchronous and Supersynchronous Oscillation Characteristics of Direct-Drive Offshore Wind Power Integrated via VSC-HVDC. J. Shanghai Jiao Tong Univ. 2022, 56, 1572–1583. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gai, C. Equivalent Modeling of Direct-Drive Wind Farms Based on LVRT Control. Master’s Thesis, Hefei University of Technology, Hefei, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Peng, S.; Zhang, Z.; Ren, W.; Li, C. Comparative Analysis of Technical Standards for Offshore Wind Power Integration via VSC-HVDC. J. Shanghai Jiao Tong Univ. 2022, 56, 403–412. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 36995-2018; Wind-Turbine Generator Systems—Fault Voltage Ride-Through Capability Testing Procedures. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2018.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).