Abstract

In the current work, we examine whether height perception is determined by head orientation. Our previous work has found that upward head orientation is overestimated by the same factor as downward head orientation, and this is consistent with the distance by which targets you must look up at are overestimated. In Experiment 1, participants looked at two targets from two different distances. Height estimates were significantly correlated to head orientation. Head orientation also significantly changed height estimates, with the closer distance (i.e., higher head orientation) yielding greater distance estimates, even when controlling for target height. In Experiment 2, we controlled for distance by having participants estimate the height of two targets while sitting down or standing. Height estimates were again significantly correlated with head orientation. Sitting or standing (i.e., manipulating head orientation) changed height estimates, with sitting yielding greater distance estimates, again, even when controlling for target height. Our work shows that head orientation is strongly positively correlated to the perception of height and that changing head orientation leads to concomitant changes in perception of height. The common scale expansion for upward and downward head orientation leads to corresponding distance estimates that reliably predict how we spatially map the environment.

1. Introduction

It has been well established that observers overestimate visually, haptically, pedally, and proprioceptively perceived geographical, virtual, and man-made hills by between 5° and 25° (Bridgeman & Cooke, 2015; Durgin & Li, 2011; Hajnal et al., 2011; Li & Durgin, 2009, 2010; Proffitt et al., 1995; Shaffer & Flint, 2011; Shaffer et al., 2019; Shaffer et al., 2016a). The relationship between actual slant and perceived slant in all of these scenarios is best described by the angular expansion hypothesis (Li et al., 2011), which predicts overestimates of upward orientation that form a linear function with a fairly constant gain of approximately 1.5 (Durgin & Li, 2011; Durgin et al., 2010; Li & Durgin, 2010; Proffitt et al., 1995; Shaffer et al., 2019). Thus, a 10° slope appears like it is 15°, and a 30° slope looks as if it is 45°.

These perceptual overestimates of slant orientation are best explained by a proportional misperception of head orientation (Durgin & Li, 2011; Klein et al., 2016; Li & Durgin, 2009; Keezing & Durgin, 2018). In this work, participants made implicit and explicit estimates of objects at different downward orientations. Estimates fit a linear function with a gain of ~1.5 indicating that observers were overestimating their head orientation. So, when orienting their head at 30°, they perceived they were orienting their head at 45° (or perceived it to be 1.5 times more tilted than actual). Durgin and Li (2011) proposed that overestimating downward head orientation has interesting implications for perception of slanted surfaces and ground extents in the depth direction. For instance, if one overestimates their downward gaze orientation by a factor of 1.5, then a flat ground surface should look as if it is tilted downward by the same factor unless we correct for it by misperceiving (overestimating) optical (or geographical) slant of surfaces by the same factor (1.5), which previous work shows that we do (especially for angles we encounter more often (less than 50°–60°)) (Durgin & Li, 2011; Durgin et al., 2010; Li & Durgin, 2010; Sinnot et al., 2023). These two biases leave the ground surface appearing flat (Li & Durgin, 2010).

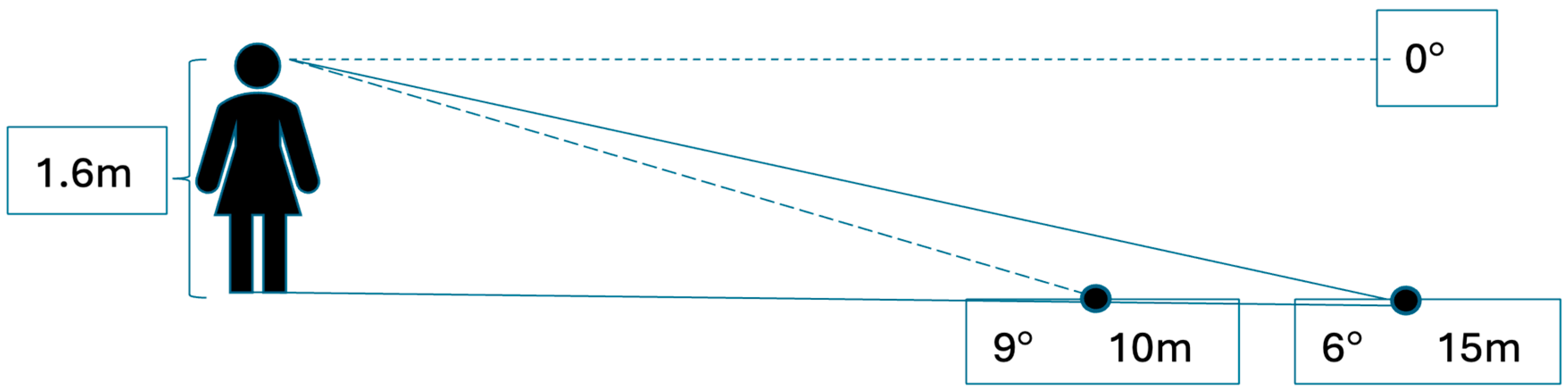

This combined bias of misperceived gaze declination accompanied by misperceived optical slant also explains the underestimation of distance in the depth direction compared to that in the sagittal direction (Durgin & Li, 2011). This is shown in Figure 1. Durgin and Li (2011) and Keezing and Durgin (2018) showed that this combined bias leaves people looking at a given distance as closer to their feet due to overestimation of gaze declination. The overestimation of gaze declination by a factor of 1.5, in fact, predicts an underestimation of ground distance by about 0.67. That is, if someone is looking at a 30° downward orientation and looking at a ball that s 15 m away, they will perceive their downward orientation at 45° (overestimating head declination by a factor of 1.5). This will leave their apparent line of sight along the 9° line in the picture, estimating their distance closer to their feet at 10 m away (or 10 m/15 m or ~0.67 or 1/1.5). This underestimation of ground distance extents fits extant data very well (see Durgin & Li, 2011 for their comparison of their angular declination work to the measured distance aspect ratios between depth and sagittal extents of Loomis et al., 1992 and Loomis & Philbeck, 1999, which fit rather closely to a perceived angular declination gaze of 1.5 (1.6 and 1.56, respectively)). Consistent with this, Li et al. (2011, Experiment 1) showed that when asked to place themselves at a distance in depth away from a frontal distance between two experimenters, participants placed themselves too far away, consistent with a perceived egocentric distance compression in the depth direction. The gain that they found (ratio of depth distance to frontal distance) was 1.43, consistent with this perceived scale expansion of space due to perceived gaze declination.

Figure 1.

We overestimate downward gaze by a factor of ~1.5, so distances in depth appear closer by an approximately proportional amount. If one is looking down at 30° and that equates to looking at a ball 15 m away, but they believe they are looking downward at 45°, then their apparent line of sight will be along the 9° line, making the ball appear closer to their feet than actual (by the inverse of 1.5 = 1/1.5 ~0.67—or 10 m/15 m in the picture).

The connection between overestimation of downward gaze orientation and underestimation of distance in the depth direction compared to frontal directions has perceptual implications for the misperception of upward gaze orientation (or gaze inclination) that could explain overestimates of vertical extents that have been found in natural and VR viewing (Klein et al., 2016; Li et al., 2011; Tardeh et al., 2024). For instance, Durgin and Li (2011) found (in their Experiment 4) that when they elevated and lowered gaze directions, gaze declination estimates were 1.46, similar to the gain of the verbal estimates across the eight sloped surfaces they examined (gain = 1.42, excluding the 22.5° condition). While the authors interpreted these results in terms of slope estimates across a range of optical slants, their Figure 7b (p. 1865) suggests that head orientation in the upward direction may be overestimated by a similar factor as is gaze declination, though this was never directly tested. However, there is indirect evidence of gaze inclination being overestimated by an equivalent magnitude by which gaze declination is overestimated. For instance, Li et al. (2011, Experiment 2) had participants perform a pole matching task to four poles that varied in height from 3.75 to 22.5 m. Participants then adjusted their forward/backward distance to the pole until it matched the height of the target. The matching estimates fit well to a linear model with a gain of 1.5 (depth distance: vertical distance). Klein et al. (2016) performed a similar task to a 10 m lamp post (Experiment 1) and found that a model with a gain of 1.47 fit estimates of overestimation in the vertical direction well. Klein et al. (2016, also Experiment 1) also performed an angular direction task asking their participants to adjust their position until they felt like they were looking (their gaze was oriented) at 45° when looking at a 35 m tall column holding a water tank. Participants stopped when their gaze was oriented at 30.7°, suggesting a gaze inclination expansion by a factor of ~1.5. Similar work has found similar depth distance on the ground: height gains of 1.67 (Higashiyama & Ueyama, 1988) and 1.47 and 1.78 (Kammann, 1967, Experiment 1A and Experiment 1B, respectively). Yet other work using matching tasks has found overestimates of heights by up to 30% depending on the distance of the observer to the target (Stefanucci & Proffitt, 2009). Finally, Shaffer et al. (2025) examined upward head orientation and found that the factor by which observers overestimated upward head orientation was 1.56–1.7, depending on the range of angles, similar to how observers overestimated downward gaze orientation. The upward head orientation overestimates predicted well observer’s overestimates of heights of familiar suspended objects from memory.

The current work had two objectives. First, we wanted to directly test whether height estimates are related to upward head orientation in a direct perception, nonmemory task. Second, we wanted to test whether systematic manipulation of head orientation is associated with concomitant changes in height estimates.

2. Experiment 1

2.1. Methods

2.1.1. Power and Sensitivity Analyses

Power Analyses

Thirty-four participants were used in Experiment 1 and twenty-five participants in Experiment 2. Consistent with the recommendations of Lakens (2022), the primary factor that informed our decision as to the number of participants to use in Experiments 1 and 2 was based on previous studies performed that most closely resemble the approach and methods of these studies—having participants estimate their gaze/head orientations. Participants used in each of these studies were 35 (Li & Durgin, 2016, Experiment 1) 19, (Li & Durgin, 2016, Experiment 2), 13 (Li & Durgin, 2009, Experiment 2B), and 8 (Li & Durgin, 2009, Experiment 3B). In all these experiments, statistically significant effects were found.

2.1.2. Sensitivity Power Analyses

Consistent with the recommendations of Giner-Sorolla et al. (2024) and Lakens (2022), once we decided on a sample size of 34 for Experiment 1 due to previous studies, we performed four effect size sensitivity analyses in order to determine the minimal effect it would take to detect the following: (1) a significant correlation between gaze and height estimates, (2) significant overestimates compared to no overestimates using a Bayesian one-sample t-test, (3) a significant difference between distance conditions using a Bayesian independent-samples t-test, and (4) a significant difference between distance conditions for each window using a Bayesian independent-samples t-test. For all sensitivity analyses, we used G*Power 3.1.9.6 (Faul et al., 2007) and the “Sensitivity: Compute required effect size—given a, power, and sample size” type of power analysis. For the correlational analysis, using a one-tailed test (head orientation and height would be positively correlated), α = 0.05, Power = 0.95, Total sample size = 68 (34 participants × two windows), the minimal correlation our study would detect is 0.384 (correlations of 0.297 and 0.345 can be detected for Power = 80% and 90%, respectively (Lakens, 2022)). For the design, we used the “Exact: Correlation: Bivariate normal model” procedure. For the one-sample t-test analysis, again using a one-tailed test (participants would overestimate height), α = 0.05, Power = 0.95, Total sample size = 68, the minimal effect our study would detect is d = 0.403 (effect sizes of d = 0.305 and 0.359 can be detected for Power = 80% and 90%, respectively (Lakens, 2022)). For the design we used the “t tests: Means: Difference from constant (one sample case)” procedure. For the independent-sample t-test analysis across window heights, again using a one-tailed test (greater head orientation would lead to greater height overestimates), α = 0.05, Power = 0.95, Sample size group 1 = 34, Sample size group 2 = 34, the minimal effect our study would detect is d = 0.806 (effect sizes of d = 0.609 and 0.717 can be detected for Power = 80% and 90%, respectively (Lakens, 2022)). For the design we used the “t tests: Means: Difference between two independent means (two groups)” procedure. Finally, for the independent-sample t-test analyses for each window height separately, again using a one-tailed test (greater head orientation would lead to greater height overestimates), α = 0.05, Power = 0.95, Sample size group 1 = 17, Sample size group 2 = 17, the minimal effect our study would detect is d = 1.15 (effect sizes of d = 0.87 and 1.03 can be detected for Power = 80% and 90%, respectively (Lakens, 2022)). For the design we used the “t tests: Means: Difference between two independent means (two groups)” procedure.

2.2. Materials

A Correlata™ (Seattle, WA, USA) digital magnetic angle finder with a two-sided laser was secured on a Schwinn™ (Madison, WI, USA) bicycle helmet that participants wore to measure upward and azimuth head orientation. The device was calibrated according to the instruction manual prior to its use. The digital magnetic angle finder has a resolution of 0.05° and an accuracy of ±0.2°.

2.3. Participants and Experimental Procedure

2.3.1. Participants

Thirty-four healthy participants (24 female) whose mean age was 21.35 years (SD = 5.83) with normal or corrected-to-normal vision from the Ohio State University at Mansfield participated in fulfillment of an Introductory Psychology requirement. Informed consent was obtained for all participants. Each participant was required to sign a consent form for the study. This study was initially approved by The Ohio State University Behavioral and Social Sciences Institutional Review Board on 25 September 2023. This approval was last updated on 26 September 2025 (Study Number: 2023B0282).

2.3.2. Experimental Procedure

Participants stood at one of two randomly assigned distances (6.797 m or 11.098 m) from the wall on which the windows were located. They were first told to look straight ahead. Here, we are referring to the subjective visual straight ahead. We checked that their head was level and then reset the angle inclinometer to zero. They were then told to look directly to the top of the second and fourth floor windows on the outside wall of a building on campus (the windows were located directly below/above one another). This was performed for two reasons. First, two different heights were used to assess the range of regularly encountered head orientations that generally match the range of gaze orientations also studied for downward gaze perception. Second, even though we measured head orientation and not “gaze” orientation (e.g., orientation of the eyes, the eyes in the head, or eyes plus head), we wanted them to look directly at a specific target to minimize the difference between head and gaze orientation. The top of the second floor window was 8.737 m from the ground, and the top of the fourth floor window was 22.592 m from the ground. Figure 2 shows views of the windows from each of the two distances. The order in which participants were asked to estimate the two windows was counterbalanced. Participants made their estimates in one of two randomly assigned ways: (1) orienting their head the same distance horizontally that the top of the window was high (n = 18) or (2) directing a researcher to walk horizontally the same distance the top of the window was high (n = 16). We measured head orientation to each window for each participant and recorded their estimates. Participants were encouraged to make as many adjustments as they wanted prior to settling on a distance. Each participant gave one estimate for each window height. No participants reported any restrictions in head movement in elevation or azimuth directions.

Figure 2.

Views of the two windows participants estimated from the “close” (panel to the left) and “far” (panel to the right) distances.

2.4. Results

2.4.1. Overview of Analyses for Experiments 1 and 2

We performed Bayesian analyses for all analyses throughout the Results section and for both experiments consistent with the recommendations of both Dienes (2024) and Kruschke (2021). We used JASP (Version 0.19.2) for all analyses. For both experiments, our first analysis was a Bayesian correlational analysis to test whether head orientation (in degrees) was positively correlated with height estimates (in meters). Next, we converted a participant’s estimates (either head orientation or researcher-directed distance) to gains (estimated height from the ground to the top of the window/actual height from the ground to the top of the window) for both the top of the second and fourth floor windows. Therefore, if a participant’s estimates were veridical, their gains would be one; if they underestimated the heights by 50%, their gains would be 0.5; and if they overestimated by 50%, their gains would be 1.5. For the remaining analyses in both Experiments 1 and 2, we used these gains as the dependent variable.

2.4.2. General Terms Used

Throughout the results and discussion of Experiment 1, we use the terms “close” and “far” to distinguish the two distances (e.g., in the subscripts, Table 1, and Figure 1).

Table 1.

Shown are means and standard deviations (in degrees) for close and far conditions for the top of the 2nd and 4th floor windows.

2.4.3. Head Orientation Versus Researcher-Directed Walking

We first performed a Bayesian independent-samples t-test comparing height estimate gains to test whether the head orientation method was different than the researcher-directed distance method. There was anecdotal-moderate evidence of no difference in perceptual height estimate gains between methods, BF01 = 2.714, t(32) = 0.54, p = 0.596, MHeadOreint = 1.5, SDHeadOrient = 0.44, MWalk = 1.58, SDWalk = 0.43. Further interpretation of the Bayes factor indicates that it is almost three times as likely there was no difference between the methods as there was a difference.1 Therefore, we combined gains for the remaining analyses.

2.4.4. Individual Differences in Eye Height

An observer’s perception of height of objects and others have been shown to be biased toward or calibrated by the perceiver’s height and eye height (Twedt et al., 2015; Wraga, 1999). We first wanted to make sure that individual differences in eye height were not associated with a participant’s height estimates. We found substantial evidence that individual differences in eye height were not statistically correlated with height estimates, BF01 = 6.58, r(67) = −0.011, p = 0.929. Further interpretation of the Bayes factor indicates that it is almost seven times as likely there was no correlation between individual differences in eye height and height estimates as there was a difference.

2.4.5. Primary Analyses

A Bayesian correlation analyzing whether an observer’s height estimates were significantly positively correlated with head orientation showed that they were, BF10 = 10.98, r(67) = 0.443, p < 0.001. This indicates that there is strong evidence in favor of them being significantly correlated. Further interpretation of the Bayes factor indicates that it is over 10 times more likely that height estimates are correlated with head orientation than they are not.

Table 1 shows means and standard deviations for close and far conditions and for both windows. Participants in the close condition oriented their head more than participants in the far condition for both the top of the second floor window and the top of the fourth floor window.

We next found that a participant’s perception of height was not veridical. Overall mean gains were statistically greater than 1, indicating decisive evidence that participants overestimated height, BF10 = 1.2 × 109, t(67) = 8.29, p < 0.001, M = 1.651, SD = 0.65. We also found anecdotal evidence that overestimates were not statistically different from 1.5, the factor by which people generally overestimate upward and downward head orientation, BF01 = 1.32.

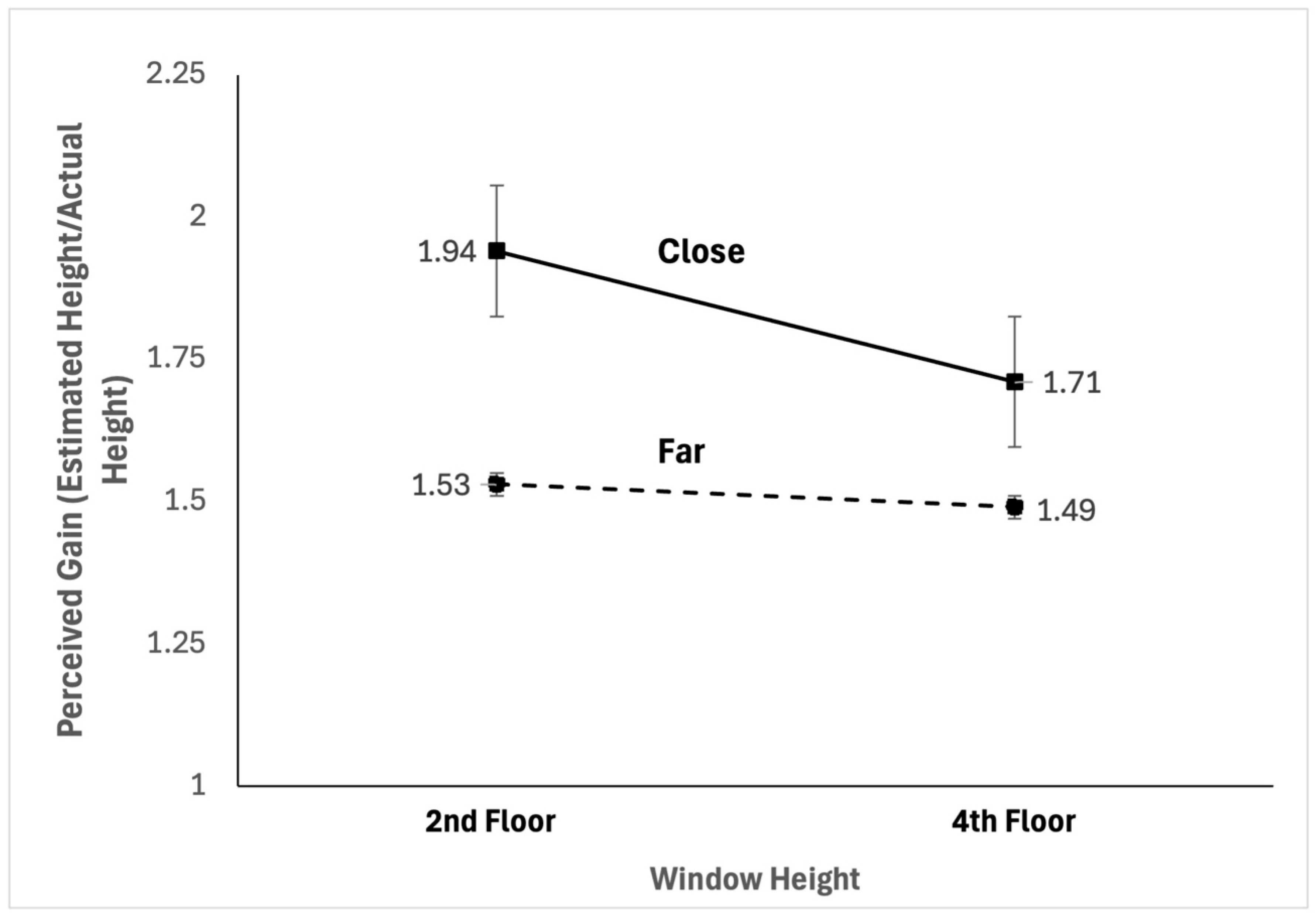

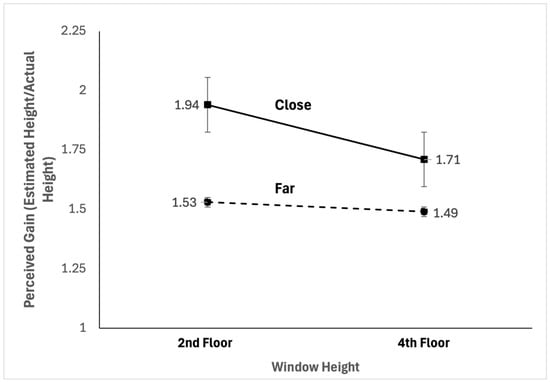

Distance from the window (i.e., head orientation) significantly changed height estimates, with closer distance (i.e., greater head orientation) yielding higher gains, BF10 = 5.43, t(66) = 2.395, p = 0.010, MClose = 1.82, SDClose = 0.77, MFar = 1.46, SDFar = 0.41. This indicates that there is substantial evidence in favor of concomitant changes in head orientation and distance estimates. Further interpretation of the Bayes factor indicates that it is over 5 times more likely that head orientation is responsible in determining height estimates than it is not. Figure 3 shows window height plotted against gain (perceived distance/actual distance) for second and fourth floor windows and for both close and far conditions. Furthermore, we tested whether head orientation is key in determining height estimates when controlling for target height. We performed two Bayesian independent-samples t-tests comparing the close and far conditions for each window. The results showed that for a window at the exact same height, people’s estimates of its height were different depending on how much they had to orient their head to see it: second floor window difference: BF10 = 1.754, MClose = 1.94, SDClose = 0.97, MFar = 1.49, SDFar = 0.51, and fourth floor window difference: BF10 = 2.57, MClose = 1.71, SDClose = 0.5, MFar = 1.49, SDFar = 0.3.

Figure 3.

Perceptual gains for close and far conditions and 2nd and 4th floor windows are shown.

2.5. Discussion

In Experiment 1, people overestimated height by a factor of ~1.5, the same factor by which people overestimate downward head orientation and the slopes of a variety of surfaces (Durgin & Li, 2011; Hajnal et al., 2011; Li & Durgin, 2009, 2010; Proffitt et al., 1995; Shaffer et al., 2019; Shaffer et al., 2016a). Their overestimates of height were also consistent with the factor by which people overestimate their own head orientation and upward distance to familiar suspended objects (Shaffer et al., 2025).

Experiment 1 further showed that an observer’s height estimates are strongly positively correlated with head orientation. The greater the head orientation, the greater the perception of height. Additionally, manipulating head orientation resulted in concomitant changes in the perception of height between head orientation conditions, with greater head orientation (the closer distance in Experiment 1) yielding greater estimates of height.

Perhaps the most compelling finding of Experiment 1 was that when we controlled for target height by comparing estimates for each window separately, height estimates are greater when head orientation is greater. That is, when comparing estimates of the second floor window between the close and far distances, estimates were greater when the head was oriented higher. Therefore, when looking at the same target at the same height (i.e., the top of the same window), people overestimate the target’s height even more when their head is oriented upward by a larger amount when the target’s actual height is the same in both instances. This suggests that objects that are at the same height may yield very different overestimations of people depending on their head orientation. One possibility that has been posited for determining the height of objects and others is eye height (Twedt et al., 2015; Wraga, 1999). The findings of Experiment 1 cannot be explained by this, as participant eye height had a near-zero correlation with height estimates.

Previous work on spatial memory shows that finger pointing to corners of a familiar multilevel building are distorted compared to actual locations in the same direction with the classic horizontal–vertical illusion (HVI) in large outdoor settings (Brandt et al., 2015; Higashiyama, 1992; Higashiyama & Ueyama, 1988; Klein et al., 2016). However, finger pointing behavior and picture drawing of remembered locations of a building exaggerated the effect far more than what is typically seen (~15–25%) in visual perception studies in large outdoor settings. Additionally, the distortions from spatial memory when finger pointing of height (~215%) are far greater than the distortion in height seen here, though that from using spatial memory to draw remembered locations of heights (~61%) fits nicely with what is shown here (between ~49 and 94% depending on the distance and condition).

While our work is strong evidence for the idea that head orientation strongly influences height perception, the way we manipulated head orientation was by simultaneously manipulating a participant’s distance away from the building’s wall on which the windows were located. We do not think that distance, per se, influenced the results for at least two reasons. First, if a mechanism equivalent to size constancy, like height constancy or overconstancy were in play (cf. Higashiyama, 1992; Higashiyama & Kitano, 1991), then one would predict the opposite effect—that observers in the far condition would estimate the height to be the same or greater than observers in the close condition in spite of the orientation of their head, as constancy would take this distance into account. Second, as shown in Figure 3, distance clearly did not affect the typical factor by which upward gaze orientation is overestimated (Klein et al., 2016).

However, increased distance does create an issue that may have affected the findings from Experiment 1. This is because if you stand far enough away, the difference between how one orients their head to two different heights will become smaller the farther away they are. This is shown in Figure 3 where the gains for the far condition are not very different between the second and fourth floor windows. Therefore, Experiment 2 was designed for two reasons. First, we wanted to control for distance while manipulating head orientation. While we do not believe that distance influenced the findings of Experiment 1, it is difficult to dismiss any potential effect of how much participants may have considered their distance away from the building when making the perceptual estimates of height, how much texture gradient differences of the building may have influenced height estimates, and how much some estimation errors (e.g., slope perception) change outside personal space (Hecht et al., 2014; Tozawa, 2012). Therefore, in Experiment 2, we sought to test whether manipulating positions of the observers between sitting and standing from the same distance close to the building would still result in height perception being governed by head orientation independent of perceptual and perhaps more cognitive effects of standing farther away.

3. Experiment 2

3.1. Methods

Sensitivity Power Analyses

Consistent with the recommendations of Giner-Sorolla et al. (2024) and Lakens (2022), once we decided on a sample size of 25 for Experiment 2 due to previous studies (and Experiment 1 of the current work), we performed four effect size sensitivity analyses in order to determine the minimal effect it would take to detect the following: (1) a significant correlation between head orientation and height estimates, (2) significant overestimates compared to no overestimates using a Bayesian one-sample t-test, (3) a significant difference between sitting/standing conditions across windows using a Bayesian independent-samples t-test, and (4) a significant difference between sitting/standing conditions for each window using a Bayesian independent-samples t-test. For all sensitivity analyses, we used G*Power 3.1.9.6 (Faul et al., 2007) and the “Sensitivity: Compute required effect size—given a, power, and sample size” type of power analysis. For the correlational analysis, using a one-tailed test (head orientation and height would be positively correlated), a = 0.05, Power = 0.95, Total sample size = 50 (25 participants × two windows), the minimal correlation our study would detect is 0.442 (correlations of 0.344 and 0.399 can be detected for Power = 80% and 90%, respectively (Lakens, 2022)). For the design, we used the “Exact: Correlation: Bivariate normal model” procedure. For the one-sample t-test analysis, again using a one-tailed test (participants would overestimate height), α = 0.05, Power = 0.95, Total sample size = 50, the minimal effect our study would detect is d = 0.472 (effect sizes of d = 0.357 and 0.42 can be detected for Power = 80% and 90%, respectively (Lakens, 2022)). For the design, we used the “t tests: Means: Difference from constant (one sample case)” procedure. For the independent-sample t-test analysis, again using a one-tailed test (greater head orientation would lead to greater height overestimates), α = 0.05, Power = 0.95, Sample size group 1 = 26, Sample size group 2 = 24, the minimal effect our study would detect is d = 0.945 (effect sizes of d = 0.714 and 0.84 can be detected for Power = 80% and 90%, respectively (Lakens, 2022)). For the design, we used the “t tests: Means: Difference between two independent means (two groups)” procedure. Finally, for the independent-sample t-test analyses for each window height separately, again using a one-tailed test (greater head orientation would lead to greater height overestimates), α = 0.05, Power = 0.95, Sample size group 1 = 12, Sample size group 2 = 13, the minimal effect our study would detect is d = 1.36 (effect sizes of d = 1.03 and 1.21 can be detected for Power = 80% and 90%, respectively (Lakens, 2022)). For the design, we used the “t tests: Means: Difference between two independent means (two groups)” procedure.

3.2. Materials

A Correlata™ digital magnetic angle finder with two-sided laser was secured on a Schwinn™ bicycle helmet that participants wore to measure upward head orientation. The device was calibrated according to the instruction manual prior to its use. The digital magnetic angle finder has a resolution of 0.05° and an accuracy of ±0.2°.

3.3. Participants and Experimental Procedure

3.3.1. Participants

Twenty-five healthy volunteer participants (18 female), mean age 18.6 years (SD = 1.32), with normal or corrected-to-normal vision from the Ohio State University at Mansfield participated in fulfillment of an Introductory Psychology requirement. All participants in Experiment 2 were different from those used in Experiment 1. Informed consent was obtained for all participants. Each participant was required to sign a consent form for the study. This study was initially approved by The Ohio State University Behavioral and Social Sciences Institutional Review Board on 25 September 2023. This approval was last updated on 26 September 2025 (Study Number: 2023B0282).

3.3.2. Experimental Procedure

Participants were randomly assigned to a sitting or standing condition. Participants in the sitting condition sat on a yoga mat. All participants were positioned 6.858 m away from the wall of the building on which the windows were located. They were told to look straight ahead. We checked that their head was level and then reset the angle inclinometer to zero. They were then told to look directly at the top of the second and fourth floor windows on the outside wall of a building on campus (the windows were located directly below/above one another). This was performed for two reasons. First, two different heights were used to assess the range of regularly encountered head orientations that generally match the range of gaze orientations in studies for downward gaze perception (Durgin & Li, 2011; Li & Durgin, 2010). Second, even though we measured head orientation and not “gaze” orientation (e.g., orientation of the eyes, the eyes in the head, or eyes plus head), we wanted them to look directly at a specific target to minimize the difference between head and gaze orientation. The order in which participants were asked to estimate the two windows was counterbalanced.

Participants made magnitude estimates of the distances to the tops of the second and fourth floor windows, based on a value we assigned to one of two experimenters. A magnitude estimation task was used to reduce possible estimation biases and remove the possibility that observers were unable to accurately transform information about height into an absolute size measurement. This technique eliminates possible distance errors and large individual differences that might arise due to these. The experimenter stood 2 m from the participant in line with the two windows. The height of the experimenter was assigned a value of 10. Participants were told that this value had no units associated with it. It was simply an arbitrary value. Participants were instructed to assign a value to the distance from the ground to the tops of the second and fourth floor windows, based on the height of the experimenter having a value on 10. They were told that if they thought the height to the top of the window was twice as high as the experimenter, they would give the distance to the top of the window a value of 20; if they thought the height to the top of the window was 10 times as high as the experimenter, they would give the distance to the top of the window a value of 100. Prior to making their magnitude estimates, participants were given practice trials until they clearly understood how to articulate their estimations. All participants fully understood how to make magnitude estimations with no more than two practice trials. We then measured their head orientation and recorded their estimates. Participants also gave a verbal estimate of their actual head orientation when it was oriented at the tops of each of the windows. Each participant gave one estimate of the height of each window and of their own head orientation.

3.4. Results

3.4.1. Individual Differences in Eye Height

We found substantial evidence that individual differences in eye height were not statistically correlated with height estimates, BF01 = 4.23, r(50) = 0.11, p = 0.445. Further interpretation of the Bayes factor indicates that it is over four times as likely there was no correlation between individual differences in eye height and height estimates as there was a difference.

3.4.2. Primary Analyses

A Bayesian correlation analyzing whether an observer’s height estimates were significantly positively correlated with head orientation showed that they were, BF10 = 85,285.87, r(48) = 0.658, p < 0.001. This indicates that there is decisive evidence in favor of them being significantly positively correlated. Further interpretation of the Bayes factor indicates that it is over 85,000 times more likely that height estimates are positively correlated with head orientation than they are not. Table 2 shows means and standard deviations for sitting and standing conditions and for both windows. Participants in the sitting condition oriented their head more than those in the standing condition for both the top of the second floor window and the top of the fourth floor window.

Table 2.

Shown are means and standard deviations (in degrees) for sitting and standing conditions for the top of the 2nd and 4th floor windows.

Another Bayesian correlation analyzing whether an observer’s height estimates were significantly positively correlated with estimates of head orientation showed that, as with the correlation between magnitude estimates and actual head orientation, they also were, BF10 = 3.251, r(48) = 0.304, p < 0.016. This indicates that there is substantial evidence in favor of height estimates also being positively correlated with estimated head orientation.

We next found that a participant’s perception of height was not veridical. Overall mean gains were statistically greater than 1, indicating decisive evidence that participants overestimated height, BF10 = 38, t(49) = 3.35, p < 0.001, M = 1.31, SD = 0.65. We also found no evidence that overestimates were or were not statistically different from 1.5, the factor by which people generally overestimate upward and downward head orientation, BF01 = 0.89.

Participants also overestimated the angle at which their head was tilted upward, BF10 = 1675.11, M = 1.9, SD = 1.31, consistent with our previous work (cf., Shaffer et al., 2025). There is anecdotal evidence that their estimates were slightly above 1.5, BF10 = 1.33, the same factor by which people overestimate upward and downward head orientation and the slopes of a variety of surfaces (Durgin & Li, 2011; Hajnal et al., 2011; Li & Durgin, 2009, 2010; Proffitt et al., 1995; Shaffer & Flint, 2011).

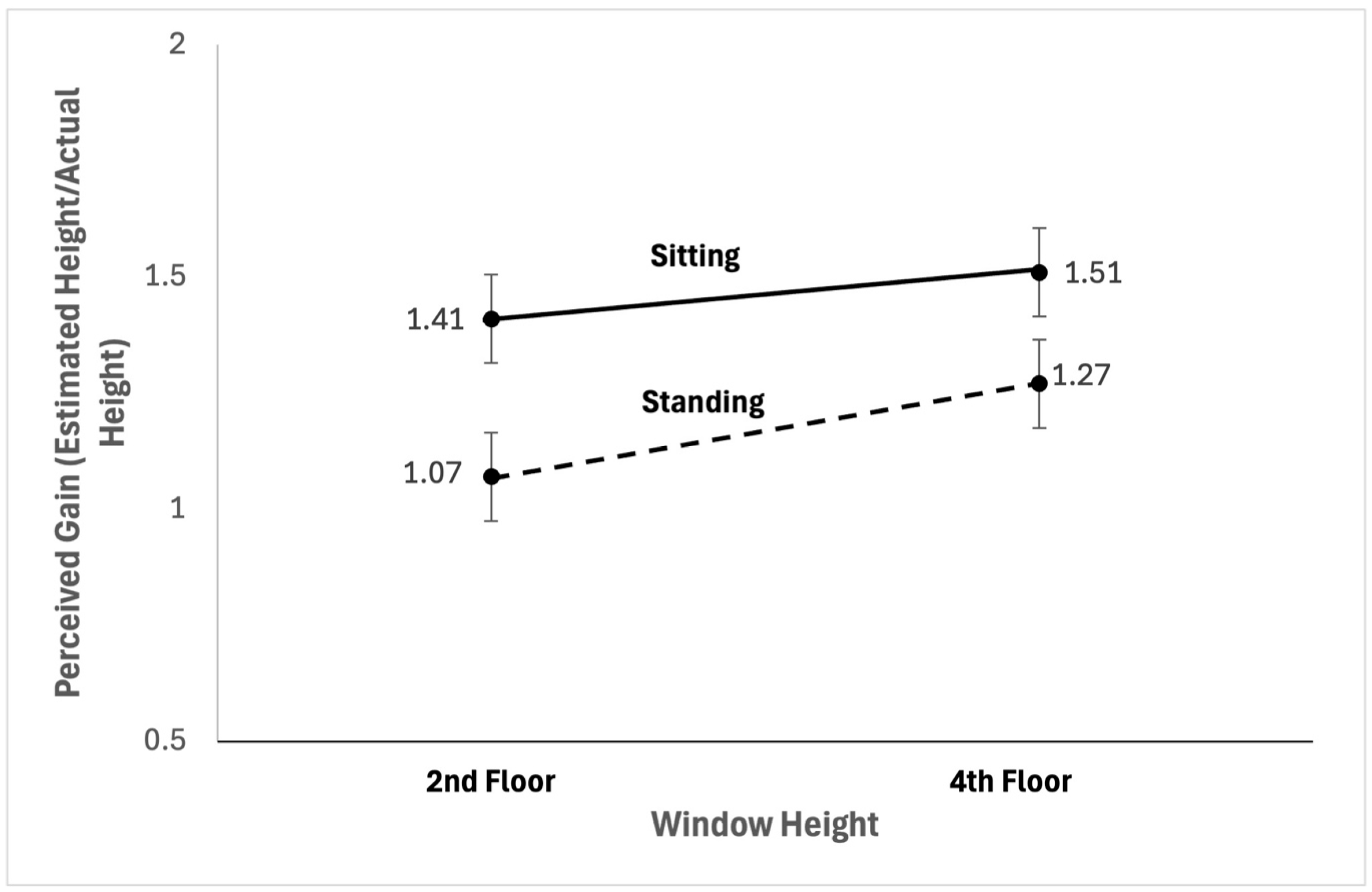

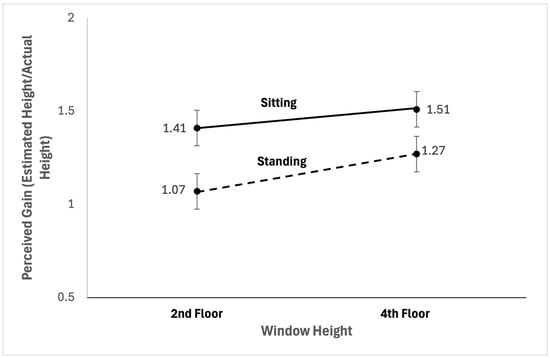

Sitting or standing (i.e., manipulating head orientation) significantly changed height estimates, with sitting yielding higher gains, BF10 = 1.531, t(48) = 1.632, p = 0.055, MSitting = 1.46, SDSitting = 0.73, MStanding = 1.17, SDStanding = 0.54. This indicates that there is anecdotal evidence in favor of concomitant changes in head orientation and distance estimates when controlling for distance to the targets. Further interpretation of the Bayes factor indicates that it is almost twice as likely that head orientation is responsible in determining height estimates than they are not. Figure 4 shows window height plotted against gain (perceived distance/actual distance) for second and fourth for both sitting and standing conditions.

Figure 4.

Perceptual gains for sitting and standing conditions and 2nd and 4th floor windows are shown.

Finally, we tested whether head orientation is key in determining height estimates when controlling for target height. We performed two Bayesian independent-samples t-tests comparing the close and far conditions for each window. The results showed that for a window at the exact same height, people’s estimates of its height were different depending on how much they had to orient their head to see it: second floor window difference: BF10 = 2.079, MSitting = 1.41, SDSitting = 0.53, MStanding = 1.07, SDStanding = 0.44, and fourth floor window difference: BF10 = 0.69, MSitting = 1.53, SDSitting = 0.92, MStanding = 1.27, SDStanding = 0.63. Though there was neither evidence for or against a difference for the fourth floor window, the mean gain was predictably higher for the sitting than the standing condition.

3.5. Discussion

Experiment 2 showed that people overestimate height by a factor a little less than, but not statistically different from, 1.5, the same factor by which people overestimate upward and downward head orientation and the slopes of a variety of surfaces (Durgin et al., 2010; Durgin & Li, 2011; Hajnal et al., 2011; Li & Durgin, 2009, 2010; Proffitt et al., 1995).

Experiment 2 confirmed the findings of Experiment 1 showing that height perception is strongly correlated with head orientation. As in Experiment 1, the higher participants looked, the greater their perception of height, even when controlling for distance from the wall on which the windows were located. Experiment 2 also showed that manipulating head orientation by having observers sit versus stand resulted in predictable and corresponding changes in the perception of height, with greater head orientation yielding greater estimates of height. Participant overestimates of height across conditions were far greater than actual and consistent with the factor by which observers have overestimated upward head orientation and the distance to familiar suspended objects (~1.5, Shaffer et al., 2025). This result was not due to participant eye height, as eye height had a near-zero correlation with height estimates.

Perhaps the most compelling finding of Experiment 2 was that when controlling for target height, height estimates are greater when head orientation is greater. Therefore, when looking at the same target at the same height, people overestimate the target’s height even more when their head is oriented upward by a larger amount when the target’s actual height is the same in both instances. While there was evidence in favor of this in terms of the difference in means and the difference in estimates for the top of the second floor window, that difference did not create a statistical difference for height estimates for the top of the fourth floor window. This is probably because observers were very close to the building and looking higher up than in any other condition in either of the experiments at head orientations approaching ~50° and by ~10° more than fourth floor window estimates from either position in Experiment 1. An issue with this is that at angles approaching 50°, head and gaze orientations are reaching maximums (Durgin & Li, 2011; Durgin et al., 2010). Additionally, many tasks studied by visual scientists subtend visual angles less than about 30°, and these can be simply modeled using projection plane geometry. In such cases, height from straight ahead can be simply represented as the vertical distance across the projection plane and approximations such as α ≈ tan α can be used (i.e., the law of small angles), even with visual angles roughly as large as 30°. At head orientations less than 30° from straight ahead, a constant change in height produces a change in perceived height that is approximately proportional. However, at head orientations approaching 50°, a constant change in height produces a change in perceived height that is about 1⁄10 of the initial actual height (tan α is constant in both cases, but α is changing) (Schneider et al., 1978; Shaffer et al., 2008).

4. General Discussion

In the current work, we have shown that head orientation is strongly positively correlated to the perception of height. On its face, this seems like a straightforward perceptual regularity, where tilting the head up more tells one that something is taller or higher up. However, we also found that changing head orientation, even when controlling for distance, leads to concomitant changes in the perception of the height of those objects. Furthermore, we found that changing head orientation alone led to predictable changes for objects at the same height. For instance, in Experiment 1, the same window was perceived to be higher up when participants were closer to it than when they were farther away. In Experiment 2, when we controlled for distance from the building on which the windows were located, objects at the same height were judged to be higher up when tilting the head more (i.e., in the sitting position). None of these effects were correlated with eye height.

This work nicely extends the bounds of the scale expansion hypothesis (or angular expansion hypothesis (AEH)) as proposed by Durgin and Li (2011). The way it does this is by connecting the work of overestimation of downward head orientation and the perceptual implications it has for the compression of depth distances with overestimation of upward head orientation and the perceptual implications it has for the expansion of elevation (height) distances (Durgin et al., 2010; Durgin & Li, 2011; Li & Durgin, 2010, 2016; Klein et al., 2016; Tardeh et al., 2024). For instance, downward head orientation is overestimated by a factor of ~1.5 (Durgin et al., 2010; Li & Durgin, 2010). Overestimating downward head orientation can explain compression of depth distances by a proportional amount. Thus, overestimating downward gaze by a factor of 1.5 leads to a perceptual compression of ~0.67 (or 1/1.5—please see Figure 1) and also explains the exaggerations of verbal and haptic estimates of sloped orientations and the anisotropy of exocentric distances (Loomis et al., 1992).

Similarly, the work of Durgin and Li (2011) suggested that head orientation in the elevation coordinate (specifically upward from straight ahead) may be overestimated by a similar factor as is gaze declination, though this was never directly tested. In many matching tasks to objects oriented vertically, it has been shown that people overestimate heights by a factor of ~1.5 (Higashiyama & Ueyama, 1988; Kammann, 1967; Klein et al., 2016; Li et al., 2011). Finally, Shaffer et al. (2025) examined upward head orientation and found that the factor by which observers overestimated upward head orientation was 1.56–1.7, depending on the range of angles, similar to how observers overestimated downward gaze orientation. The upward head orientation overestimates predicted well observer’s overestimates of heights of familiar suspended objects from memory. The current work helps connect the upward gaze/head orientation work by showing that perceived upward head orientation plays a large role in governing expansion of height estimates, as previous work has shown perceived downward gaze declination plays a large role in governing compression of depth distances. The overestimation of head orientation in the elevation coordinate or scale expansion of angles—above and below straight ahead (gaze parallel to the line of sight)—seems to be a perceptual regularity that also has predictable implications for the compression and expansion of visual space depending on the upward or downward orientation of the observer.

What mechanisms might explain this perceptual anisotropy of spatial distances where distances in the upward direction of the elevation coordinate are expanded (Klein et al., 2016; Tardeh et al., 2024)? Since we did not measure these directly, we are merely speculating on the mechanisms that might be at work here either physiologically or otherwise egocentrically based on previous work—for instance, the otolithic organs of the inner ear, specifically saccule, and the hair cells within it, which respond to bending due to movement of the body and head. The hair cells in the saccule specifically are oriented primarily in the vertical plane and are important for sensing upward and downward motion (Curthoys, 2020; Karaman et al., 2025). Previous work showing mechanical stimulation of the saccule by manipulating viewing conditions from the fifth floor of a building looking down or on the ground floor looking up to the fifth floor in actual and virtual reality (VR) viewing conditions found no differences in height estimates between actual (mechanical stimulation of saccule) and VR conditions, suggesting little or no involvement of mechanical stimulation of the saccule in height perception (Karaman et al., 2025). Other work has found no differences in spatial processing effects of vestibular input in general but did find that specific vestibular input did change spatial processing when examining leftward–rightward movement (Ferrè et al., 2013).

Other egocentric mechanisms that might specifically explain height estimates due to orientation of the head could be head-centric, body axis, or retinotopic (Higashiyama, 1992; Higashiyama & Ueyama, 1988; Klein et al., 2016; Tardeh et al., 2024). Klein et al. (2016—Experiment 1) had participants look at a light pole (10 m high) or water tower (35 m high) while either sitting upright, standing upright, tilted at 45°, or lying sideways (at 90°). Participants in all conditions were then asked to have the cart moved as far away from the light pole and water tower as they were high, or to move the cart so that the angle from where they were looking to the top of each was at a 45° angle. In both tasks and across all conditions, participants estimated they were positioned at an angle that measured 30° away from the top of both objects. Klein et al. (2016—Experiment 2) had participants either lying sideways or standing upright estimate heights of several differently-sized upright poles by positioning a research assistant holding another pole the same distance horizontally as the pole was high. They then computed the geometric mean for the height/width ratio values as the allocentric component and the square root of the ratio between them as the egocentric component. Based on prior studies, the expected egocentric component accounted for 5% of the overestimation of height compared to width (consistent with the large-scale horizontal–vertical illusion (HVI)), while the expected allocentric component accounted for 20%. In their Experiment 3, they tilted the ground at 90° in a VR version of the HVI illusion of their Experiment 2 and found a similar large-scale ground-based allocentric HVI component (Klein et al., 2016). Higashiyama took participants outdoors and had them match horizontal distances with vertical distances and found no differences in look-up and look-down conditions, suggesting that head and eye position do not contribute to judgments of vertical and horizontal distances. Tardeh et al. (2024) performed five different experiments using different VR views in each one. They found that supine observers maintained the same overestimation by a factor of ~1.5 for elevated targets (relative to other targets in the VR scene) even in the absence of a ground plane. This overestimation by a factor of ~1.5 also occurred when making azimuthal judgments that are typically overestimated by a factor of ~1.2. In a gravitational sense when looking upward from a supine position, all directions are in elevation. They concluded that it is not a ground plane that matters for these estimates but a gravitational plane that serves as the default reference frame for angular expansion.

Thus, it seems that the allocentric rather than egocentric components contribute far more to overestimations in the elevation coordinate and that the gravitational reference frame is the default reference frame. However, these studies do not dismiss the possibility of egocentric components contributing to the results in the current work. This is because in none of that work (mentioned in the preceding paragraph) were participants asked to move their heads to different locations in the upward direction of the elevation coordinate while performing any of these tasks. Given that the otolith organs are, at least in part, gravity receptors (Curthoys, 2020), it seems like there may be more of a more specific egocentric (head-centric) component to the tasks we asked participants to perform. Only future work, perhaps where people are randomly assigned to either a standing upright condition looking at two different heights (similar to the current Experiment 1) or an inversion table condition where they are tilted back to be looking directly at the same heights depending on their tilt (cf., Shaffer et al., 2016b), will be able to disentangle this.

This work also has interesting implications for the perception of physical height of other people. It is well known that taller people are paid more in their jobs, are promoted more often, are more often in leadership positions, and are more likely to be CEOs of Fortune 500 companies (Bittmann, 2020; Gladwell, 2005; Judge & Cable, 2004). Judge and Cable (2004) performed a meta-analysis across 45 studies including 8500 participants and found that a person earns USD ~790/year more for every inch of height above average, even when controlling for gender, age, and weight. Additionally, over 50% of Fortune 500 CEOs are 6’ tall or taller, which is taller than the average American male and is far greater than the percentage of people that tall in the general male population (~14.5%) (Gladwell, 2005). Our work suggests that due to the overestimation of both upward and downward head orientation, perhaps “taller” and “shorter” may be better descriptors of what governs people’s view of others. Since head/gaze orientation are determined relative to oneself or egocentrically while the terms “tall” and “short” suggest an allocentric or world-based reference system, it seems that more appropriate terms for these traits might be “taller” and “shorter” or “perceptual height.” Some evidence supports this idea of relative height effects for people in leadership positions (Bittmann, 2020). These, along with other attributes, may be more determined egocentrically and not by physical height alone.

5. Conclusions

Upward head orientation is overestimated by the same factor as is downward head orientation, and this is consistent with the distance by which targets you must look up at are overestimated. Our work shows that height estimates are significantly correlated to head orientation and that head orientation significantly changes height estimates, with higher head orientation yielding greater distance estimates. Perhaps most compelling is that when looking at the same target at the same height, people overestimate the target’s height more when their head is oriented upward by a larger amount while positioned the same distance away from the target. This common scale expansion for upward and downward head/gaze orientation leads to predictable corresponding distance estimates that reliably predict how we spatially map the environment and how we perceive the world.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M.S.; methodology, B.H. and C.B.; formal analysis, D.M.S.; investigation, D.M.S., B.H., and C.B.; writing—original draft preparation, D.M.S. and B.H.; writing—review and editing, D.M.S., B.H., and C.B.; supervision, D.M.S.; project administration, D.M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by The Ohio State University Behavioral and Social Sciences Institutional Review Board (Study Number: 2023B0282, 26 September 2025) and adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines. Prior to the experiment, all participants were briefed about the procedure and potential risks and provided written informed consent.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Note

| 1 | Bayes factors were calculated as evidence for both the null (BF01 = P(H0)/P(HA)) and alternative (BF10 = P(HA)/P(H0) hypotheses. According to Wetzels et al. (2011), a Bayes factor of 0–1 is no evidence for either the null (H0) or alternative hypothesis (HA), 1–3 is anecdotal evidence for the tested hypothesis (probability of the hypothesis in the numerator of the equations above), 3–10 is substantial evidence for the tested hypothesis, 10–30 is strong evidence for the tested hypothesis, 30–100 is very strong evidence for the tested hypothesis, and 100 is decisive evidence for the tested hypothesis. |

References

- Bittmann, F. (2020). The relationship between height and leadership: Evidence from across Europe. Economics & Human Biology, 36, 100829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, T., Huber, M., Schramm, H., Kugler, G., Dieterich, M., & Glasauer, S. (2015). “Taller and shorter”: 3-D spatial memory distorts familiar multilevel buildings. PLoS ONE, 10, e0141257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgeman, B., & Cooke, I. (2015). Effect of eye height on estimated slopes of hills. Perception, 44, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curthoys, I. S. (2020). The anatomical and physiological basis of clinical tests of otolith function. A tribute to Yoshio Uchino. Frontiers in Neurology, 11, 566895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dienes, Z. (2024). Use one system for all results to avoid contradiction: Advice for using significance tests, equivalence tests, and Bayes factors. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 50, 531–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durgin, F. H., & Li, Z. (2011). Perceptual scale expansion: An efficient angular coding strategy for locomotor space. Attention, Perception & Psychophysics, 73, 1856–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durgin, F. H., Li, Z., & Hajnal, A. (2010). Slant perception in near space is categorically biased: Evidence for a vertical tendency. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 72, 1875–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrè, E. R., Longo, M. R., Fiori, F., & Haggard, P. (2013). Vestibular modulation of spatial perception. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giner-Sorolla, R., Montoya, A. K., Riefman, A., Carpenter, T., Lewis, N. A., Jr., Aberson, C. L., Bostyn, D. H., Conrique, B. G., Ng, B. W., Schoemann, A. M., & Soderberg, C. (2024). Power to detect what? Considerations for planning and evaluating sample size. Personality & Social Psychological Review, 28, 276–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladwell, M. (2005). Blink: The power of thinking without thinking. Little, Brown and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Hajnal, A., Abdul-Malak, D. T., & Durgin, F. H. (2011). The perceptual experience of slope by foot and by finger. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 37, 709–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, H., Shaffer, D., Keshavarz, B., & Flint, M. (2014). Slope estimation and viewing distance of the observer. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 76, 1729–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashiyama, A. (1992). Anisotropic perception of visual angle: Implications for the horizontal -vertical illusion, overconstancy of size, and the moon illusion. Perception & Psychophysics, 51, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Higashiyama, A., & Kitano, S. (1991). Perceived size and distance of persons in natural outdoor settings: The effects of familiar size. Psychologia, 34, 188–199. [Google Scholar]

- Higashiyama, A., & Ueyama, E. (1988). The perception of vertical and horizontal distances in outdoor settings. Perception & Psychophysics, 44, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Judge, T. A., & Cable, D. M. (2004). The effect of physical height on workplace success and income: Preliminary test of a theoretical model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 428–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammann, N. (1967). The overestimation of vertical distance and slope and its role in the moon illusion. Perception & Psychophysics, 2, 585–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, E., Yilmaz, O., & Eti, S. (2025). Comparison of virtual reality and real environment effects on perception of height in healthy individuals. PLoS ONE, 20(8), e0330443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keezing, U., & Durgin, F. H. (2018). Do explicit estimates of angular declination become ungrounded in the presence of a ground plane? i-Perception, 9, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, B. J., Li, Z., & Durgin, F. H. (2016). Large perceptual distortions of locomotor action space occur in ground-based coordinates: Angular expansion and the large-scale horizontal-vertical illusion. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 42, 581–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruschke, J. K. (2021). Bayesian analysis reporting guidelines. Nature Human Behaviour, 5, 1282–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakens, D. (2022). Sample size justification. Collabra: Psychology, 8, 33267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., & Durgin, F. H. (2009). Downhill slopes look shallower from the edge. Journal of Vision, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., & Durgin, F. H. (2010). Perceived slant of binocularly viewed large-scale surfaces: A common model from explicit and implicit measures. Journal of Vision, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z., & Durgin, F. H. (2016). Perceived azimuth direction is exaggerated: Converging evidence from explicit and implicit measures. Journal of Vision, 16, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., Phillips, J., & Durgin, F. H. (2011). The underestimation of egocentric distance: Evidence from frontal matching tasks. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 73, 2205–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomis, J. M., da Silva, J. A., Fujita, N., & Fukusima, S. S. (1992). Visual space perception and visually guided action. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 18, 906–921. [Google Scholar]

- Loomis, J. M., & Philbeck, J. W. (1999). Is the anisotropy of perceived 3-D shape invariant across scale? Perception, & Psychophysics, 61, 397–402. [Google Scholar]

- Proffitt, D. R., Bhalla, M., Gossweiler, R., & Midgett, J. (1995). Perceiving geographical slant. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 2, 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B., Ehrlich, D. J., Stein, R., Flaum, M., & Mangel, S. (1978). Changes in the apparent lengths of lines as a function of degree of retinal eccentricity. Perception, 7, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaffer, D. M., & Flint, M. (2011). Escalating slant: Increasing physiological potential does not reduce slant overestimates. Psychological Science, 22, 209–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaffer, D. M., Greer, K. M., Schaffer, J. T., Burkhardt, M., Mattingly, K., Short, B., & Cramer, C. (2019). Pedal and haptic estimates of slant suggest a common underlying representation. Acta Psychologica, 192, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, D. M., Hill, B., Brown, C., Juarez, M., & Shaver, A. (2025). Things are looking (farther) up: Upward gaze orientation is overestimated [Manuscript in preparation]. Department of Psychology, The Ohio State University.

- Shaffer, D. M., McBeath, M. K., Krauchunas, S. M., & Sugar, T. G. (2008). Evidence for a generic Interceptive strategy. Perception & Psychophysics, 70, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shaffer, D. M., Taylor, A., McManama, E., Thomas, A., Smith, E., & Graves, P. (2016a). Palm board and verbal estimates of slant reflect the same perceptual representation. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 78, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shaffer, D. M., Taylor, A., Thomas, A., Graves, P., Smith, E., & McManama, E. (2016b). Pitching people with an inversion table: Estimates of body orientation are tipped as much as those of visual surfaces. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 78, 700–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sinnot, C. B., Hausamann, P. A., & MacNeilage, P. R. (2023). Natural statistics of human head orientation constrain models of vestibular processing. Scientific Reports, 13, 5882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanucci, J. K., & Proffitt, D. R. (2009). The roles of altitude and fear in the perception of height. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 35, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardeh, P. U. D., Xu, C., & Durgin, F. H. (2024). Default reference frames for angular expansion in the perception of visual direction. Vision, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tozawa, J. (2012). Height perception influenced by texture gradient. Perception, 41, 774–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twedt, E., Crawford, E., & Proffitt, D. R. (2015). Judgments of others’ heights are biased toward the height of the perceiver. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 22, 566–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzels, R., Matzke, D., Lee, M. D., Rouder, J. N., Iverson, G. J., & Wagenmakers, E. J. (2011). Statistical evidence in experimental psychology: An empirical Comparison using 855 t tests. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wraga, M. (1999). The role of eye height in perceiving affordances and object dimensions. Perception & Psychophysics, 61, 490–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.